ABSTRACT

Background: Trauma exposure in Indonesia is high despite the fact that there is limited accessibility to mental healthcare. Pulihkan Luka (PL) is a web-based trauma psychoeducation intervention that aims to provide a practical solution to overcome barriers to accessing mental healthcare.

Objectives: This article aimed to (1) describe the cultural adaptation process of PL for Indonesian students and (2) describe the design of the pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) that examines the feasibility and acceptability of PL.

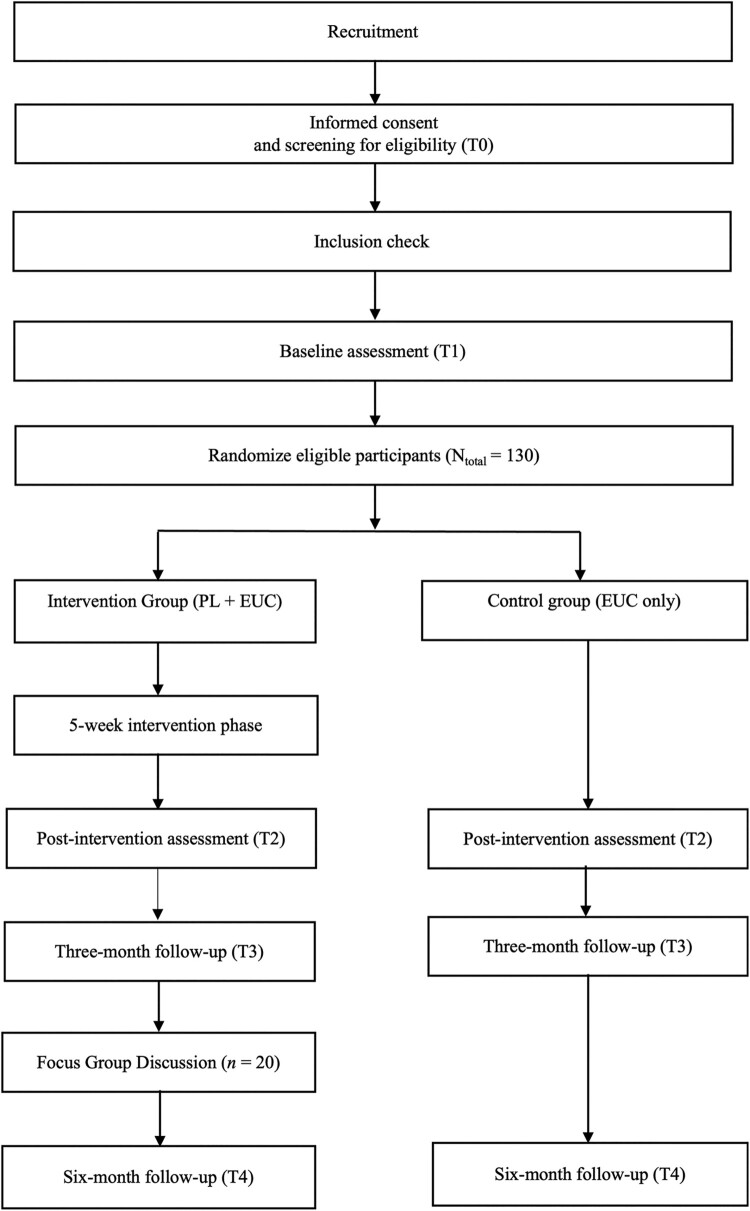

Methods: First, we describe the cultural adaptation process of PL following the 5-phase Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP) approach: (1) knowledge generation, (2) information integration, (3) review and revision, (4) mini-testing, and (5) finalisation. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) was conducted to gather the views of 15 stakeholders on psychoeducation material and trauma-related mental health problems. Based on the outcomes, we decided to utilise the informal Indonesian language, incorporate practical worksheets and infographics, which include illustrations that reflect Indonesia’s cultural diversity, and provide guidance on seeking help that aligns with the mental health system in Indonesia. Second, we describe the design of a pilot RCT. Undergraduate students (N = 130) will be randomised to (1) four to seven sessions of PL + Enhanced Usual Care (PL + EUC; n = 65) or (2) Enhanced Usual Care only (EUC only; n = 65). Assessments will be conducted at baseline, post-intervention, and three and six-month follow-up. Additionally, 20 participants will be invited for an FGD to explore their experiences with the intervention. Quantitative data will be analysed using linear mixed-effect models, and qualitative data will be analysed using thematic analysis.

Discussion: Cultural adaptation is crucial for optimally developing and assessing the feasibility and acceptability of a web-based trauma psychoeducation intervention in Indonesia. The outcomes of the RCT will inform the feasibility and acceptability of web-based trauma psychoeducation in the Indonesian undergraduate student population.

KEYWORDS: Trauma-related disorders, web-based psychoeducation, randomised controlled trial, internet-based self-help, cultural adaptation

HIGHLIGHTS

Studies examining trauma-based psychoeducation in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are scarce.

Web-based psychoeducation may be a promising intervention for trauma-affected people in a country like Indonesia, with high exposure and limited healthcare.

Cultural adaptation might improve intervention’s feasibility and effectiveness.

Abstract

Antecedentes: La exposición al trauma en Indonesia es alta a pesar de que la accesibilidad a la atención sanitaria mental es limitada. Pulihkan Luka (PL) es una intervención de psicoeducación sobre el trauma en plataforma web que tiene como objetivo proporcionar una solución práctica para superar las barreras de acceso a la atención de salud mental.

Objetivos: Este artículo tiene como objetivo (1) describir el proceso de adaptación cultural de PL para los estudiantes indonesios y (2) describir el diseño del ensayo controlado aleatorizado piloto (ECA) que examina la viabilidad y aceptabilidad de PL.

Método: En primer lugar, describimos el proceso de adaptación cultural de la PL siguiendo el enfoque del Método Formativo para la Adaptación de la Psicoterapia (FMAP por sus siglas en ingles) de 5 fases: (1) generación de conocimiento, (2) integración de la información, (3) revisión y corrección, (4) miniprueba y (5) finalización. Se llevó a cabo un debate en grupo focal (DGF) para recabar las opiniones de 15 partes interesadas sobre el material de psicoeducación y los problemas de salud mental relacionados con el trauma. Basándonos en los resultados, decidimos utilizar el lenguaje informal indonesio, incorporar hojas de trabajo prácticas e infografías, que incluyan ilustraciones que reflejen la diversidad cultural de Indonesia, y proporcionar orientación sobre la búsqueda de ayuda que se ajuste al sistema de salud mental de Indonesia. En segundo lugar, describimos el diseño de un ECA piloto. Los estudiantes universitarios (N = 130) serán asignados aleatoriamente a (1) cuatro a siete sesiones de PL + atención habitual mejorada (PL + EUC; n = 65) o (2) atención habitual mejorada solamente (EUC solamente; n = 65). Las evaluaciones se realizarán al inicio, después de la intervención y a los tres y seis meses de seguimiento. Además, se invitará a 20 participantes a un DGF para explorar sus experiencias con la intervención. Los datos cuantitativos se analizarán mediante modelos lineales de efectos mixtos, y los datos cualitativos se analizarán mediante análisis temático.

Discusión: La adaptación cultural es crucial para desarrollar y evaluar de forma óptima la viabilidad y aceptabilidad de una intervención de psicoeducación sobre el trauma en plataforma web en Indonesia. Los resultados del ECA informarán sobre la viabilidad y aceptabilidad de la psicoeducación sobre el trauma basada en la web en la población de estudiantes universitarios de Indonesia.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Trastornos relacionados con trauma, psicoeducación a través de internet, ensayo controlado aleatorizado, autoayuda a través de internet, adaptación cultural

1. Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Survey reported that the majority of the population in countries across the globe has been exposed to one or more Potentially Traumatic Events (PTEs) during their lifetime (Kessler et al., 2017). The chance of being exposed to PTEs is much higher in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to high-income countries (HICs) (Atwoli et al., 2015) due to ongoing conflict, mass displacement, socio-economic inequality (Robson et al., 2019), violence (Wolf et al., 2014), and natural disasters (Lee et al., 2014). Despite the higher likelihood of experiencing PTEs in LMICs, LMICs have been underrepresented in traumatic stress research (Robson et al., 2019).

Indonesia has been struggling with enduring challenges posed by PTEs. With 97% of the total population residing in disaster-prone regions (Suprapto et al., 2015), a lengthy record of sociocultural conflicts (Setiawan & Ali, 2021) and terrorist activities (Solahudin, 2013), the Indonesian population is susceptible to trauma exposure. Moreover, gender-based violence is pervasive in Indonesia, with two out of five Indonesian women reporting sexual, physical, emotional, and/or economic violence (Hulupi, 2017). Furthermore, among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, Indonesia ranks the highest in the number of traffic accidents (ASEANStats, 2022) accidents.

During and in the aftermath of trauma, people typically experience symptoms such as intrusions, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, alterations in emotional states and cognitive function, and hyperarousal (Hamam et al., 2021), which are considered normal traumatic stress reactions. As time passes, the majority of trauma-exposed people do not develop trauma-related disorders (Bonanno et al., 2023). However, some people have prolonged stress reactions that lead to chronic trauma-related disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) (Langtry et al., 2021; Scheepstra et al., 2020) which require clinical attention. Moreover, the repercussions of traumatic events extend beyond the individuals directly affected, encompassing both the social environment and society as a whole (Kleber, 2019). Therefore, from a public mental health perspective, treating trauma-related mental health problems is crucial (Brooks & Greenberg, 2022).

Although there is currently no nationwide epidemiological data available on trauma and trauma-related disorders in Indonesia, several studies reported that more than 90% of the population in disaster-prone and conflict areas has been exposed to PTEs (Downs et al., 2017; Marthoenis, Meutia, Sofyan, et al., 2018), and prevalence estimates of several trauma-related disorders were high: 21–60% met criteria for point prevalence PTSD (Aurizki et al., 2019; Downs et al., 2017; Marthoenis et al., 2019), 17–19% met criteria for point prevalence for depression (Marthoenis et al., 2019; Marthoenis, Meutia, Fathiariani, et al., 2018), and 27–32% met criteria for point prevalence anxiety disorders (Marthoenis et al., 2019; Marthoenis, Meutia, Fathiariani, et al., 2018).

Despite the Indonesian Government’s efforts to improve the mental health system (Bikker et al., 2021; Hidayat et al., 2023), the general provisions of mental health services in Indonesia remain underdeveloped compared to neighbouring countries (Bikker et al., 2021; Praharso et al., 2020). A significant scarcity of mental health professionals, as the lack of service availability and care facilities, inadequate government mental health expenditure (World Health Organization, 2022), stigma (Hartini et al., 2018), personal financial constraints, and limited mental health literacy are substantial barriers to mental healthcare in Indonesia (Munira et al., 2023; Prawira et al., 2021; Putri et al., 2022, 2021). Consequently, the majority of the population experiences a significant treatment gap (Idaiani & Riyadi, 2018; Praharso et al., 2020).

Many evidence-based interventions addressing psychological symptoms related to trauma are available at present times (Bisson & Olff, 2021; Lewis et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2019; Watkins et al., 2018), and the evidence for these interventions in LMICs is mounting (Barbui et al., 2020; Fu et al., 2020). However, in many LMICs, including Indonesia, there is limited access to mental health care due to multiple barriers, such as geographical challenges, stigma, and costs (Munira et al., 2023). Therefore, there is a necessity for easy-to-administer, scalable interventions that may address the adverse mental health consequences of trauma exposure to larger populations. One intervention commonly used following trauma in LMIC settings is psychoeducation (Bolton et al., 2023; Wessely et al., 2008). In principle, psychoeducation includes information on the nature of trauma, the impact of trauma exposure, effective coping strategies, building resilience, and help-seeking resources (Phoenix, 2007; Wessely et al., 2008; Whitworth, 2016). This intervention could be delivered in an individual or group environment using multiple modes, including a leaflet/booklet (Ehlers et al., 2003; Scholes et al., 2007; Turpin et al., 2005), video (Wong et al., 2013), or online platform (Benight et al., 2018; Carrasco et al., 2020; Mouthaan et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013).

Although psychoeducation is recognised as an important intervention strategy and is frequently employed by clinicians and mental-health workers in the psychotrauma field, evidence about its clinical efficacy is mixed (Wessely et al., 2008; Whitworth, 2016). The latest systematic review on the effectiveness and acceptability of psychoeducation interventions (Brooks, Weston et al., 2021) reported that psychoeducation was generally considered acceptable and useful. Some evidence from this study also indicated that psychoeducation improved mental health literacy, attitudes toward mental health intervention, and help-seeking intentions. However, psychoeducation was not effective in improving mental health outcomes (Brooks, Weston et al., 2021). It is vital to note that the majority of studies related to psychoeducation intervention were conducted in HIC settings. For instance, in the latest systematic review on the effectiveness and acceptability of psychoeducation interventions (Brooks, Weston et al., 2021), only one study was conducted in LMIC settings compared to the nine studies conducted in HIC settings. In Indonesia, no previous studies have investigated the feasibility, acceptability, and clinical efficacy of psychoeducation for PTSD.

While there is limited evidence of the clinical efficacy of psychoeducation (Brooks, Weston, et al., 2021), this intervention, particularly in the web-based version, could be useful to implement in LMIC settings, particularly in Indonesia, as a first step in stepped care strategy. First, web-based psychoeducation intervention has the potential to address low mental health literacy, reduce high stigma as well as increase intention to seek (professional) help. Mental health literacy among the majority of the Indonesian population is considered low (Novianty, 2018), leading to higher stigmatisation, delays in accessing treatment, and the development of mental health problems (Hartini et al., 2018; Soebiantoro, 2017). In addition, there is currently a shortage of culturally sensitive interventions aimed at improving mental health literacy in Indonesia (Brooks, Syarif et al., 2021). Second, web-based psychoeducation is generally more cost-effective, feasible, and scalable to implement in resource and budget-limited settings like Indonesia. As opposed to developed countries where evidence-based treatments of PTSD are accessible and become a standard, the majority of the Indonesian population is unlikely to benefit from them. The scarcity of mental health professionals and limited access (World Health Organization, 2022) to specialised trauma treatments make scalable and low-cost interventions essential to reach underserved populations in Indonesia without being restricted by geographical and financial constraints. Third, web-based psychoeducation intervention offers a safe and less stigmatising environment (Naslund & Deng, 2021) to implement in Indonesia, where mental health-related stigma and mental health shame are pervasive (Kotera et al., 2024; Subu et al., 2022). This is particularly relevant when addressing shame and guilt-prone trauma experiences, such as sexual and domestic violence-related trauma. These types of trauma experiences pose significant challenges in Indonesian culture, where shame and guilt are deeply rooted in the society.

Furthermore, given the increased prevalence of mental health disorders among young Indonesians (Cipta & Saputra, 2022), there is a need to focus on young adults such as undergraduate students. A previous cross-sectional study reported that 25% and 51% of Indonesian university students suffer from symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively (Astutik et al., 2020). Notably, 93% and 95% of students reported disengagement and exhaustion as symptoms of psychological burnout (Lili et al., 2022), and 50% reported self-harm and suicidal thoughts (Kaligis et al., 2021). Fortunately, there has been growing awareness among Indonesians, predominantly the young generation, about the importance of mental health in recent years (Cipta & Saputra, 2022; Putri et al., 2023). This might render them more accepting and responsive to mental health interventions, such as web-based psychoeducation. Recent studies examining the effect of psychoeducation on students’ mental health revealed promising outcomes, including improvements in self-esteem, mental well-being, attitudes towards help-seeking, and reductions in academic distress (Hood et al., 2021; Kirschner et al., 2022; Savell et al., 2023). However, previous research also indicated that psychoeducation does not significantly alleviate depressive symptoms and difficulties with coping with stress (Savell et al., 2023). Moreover, online psychoeducation was not superior in reducing depressive symptoms compared to internet and app-based stress interventions (Harrer et al., 2021).

This mixed evidence about the efficacy of psychoeducation interventions, as well as the lack of available interventions and research, specifically in LMICs, warrants further exploration. If proven effective, psychoeducation might be practical in LMICs since it does not require trained personal facilities, high cost, and complex infrastructure. However, interventions developed in HIC settings ought to be culturally adapted to the LMIC context first to ensure the intervention is relevant and acceptable to the cultural background of the study population. This adaptation process plays a critical role in enhancing both the feasibility and effectiveness of the intervention (Shehadeh et al., 2016).

Therefore, this study sets out to (1) outline the cultural adaptation process involved in the development of the web-based PL psychoeducation intervention for Indonesian students and (2) describe the study design of the pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) that investigates the feasibility and acceptability of the web-based trauma intervention for Indonesian undergraduate students.

2. Methods

2.1. The phase of the systemic cultural adaptation process

2.1.1. Phase 0: preparation

Prior to the adaptation phase, we had discussions with two clinical psychologists and programme managers of mental health services for undergraduate students. We aimed to capture trauma-related mental health problems experienced by Indonesian university students, the type of adverse experiences that trouble them most, psychosocial factors that contribute to mental health problems, and expectations about the psychoeducation programme. In accordance with Whitworth’s recommendation for trauma recovery psychoeducation (Whitworth, 2016), the research team intensively discussed the content of the PL programme with the clinical psychologists. After we reached a consensus about the content, we requested formal permission from Mind, the developer of the Mind psychoeducation website, to adapt their content to Indonesian and were granted permission.

We followed the Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP) guidelines (Hwang, 2009) to adapt the psychoeducation intervention from the original English version to the Indonesian version. This 5-phase bottom-up approach was selected due to its benefit in involving community-based stakeholders, which is suitable for customising interventions to meet the needs of target users. During the adaptation process, we also considered eight culturally sensitive elements recommended by Bernal et al. (1995): language, persons, metaphor, content, concept, goals, methods, and context. We involved 10 professionals with an Indonesian background, including psychologists, website developers, a translator, a language editor, illustrators, and research assistants, to carry out the cultural adaptation process in collaboration with 15 stakeholders (clinical psychologists, mental health community members, and university students). The research team was led by the first author, an Indonesian clinical psychologist and lecturer who has experience in developing and implementing mental health prevention and intervention strategies across diverse socio-economic settings.

2.1.2. Phase I: generating knowledge and collaborating with stakeholders

According to the FMAP guidelines (Hwang, 2009), six recommended stakeholders for the adaptation process can be identified, namely: (1) conventional health and mental health care agencies, (2) conventional health and mental health care providers, (3) community-based organisations and agencies, (4) traditional and indigenous healers, (5) spiritual and religious organisation, and (6) clients. For this study, we decided to collaborate with five licensed clinical psychologists who work at a hospital, primary care, private mental health clinic, and university-based mental health centre as representatives of conventional health and mental health care providers and agencies. We also involved five advocates and students of mental health community members representing the community-based organisations and agencies. We also included five university students as target users. With the aim of ensuring the representativeness of the cultural and religious background of the Indonesian population, we selected the stakeholders from diverse institutions, cities, islands, and religions. These stakeholders were chosen due to their extensive knowledge and first-hand experience related to trauma and mental health problems in Indonesia, particularly within the higher-education context. Stakeholders were identified and contacted through our professional network, including associations, universities, and mental-health communities. We established a line of communication and actively involved the stakeholders in the adaptation process, encouraging stakeholders to voice their opinions and suggestions throughout the projects.

Subsequently, we hired one professional English-Indonesian translator with a clinical psychology background to translate the selected psychoeducation material from English into Indonesian. The first author, who has a background in clinical psychology and Indonesian culture, then reviewed and prepared the translated material for the selected stakeholders. The soft copy of the psychoeducation material was then sent to the stakeholders, along with the review form and guidelines, reference to the original psychoeducation website, and academic articles related to the cultural adaptation process. We asked all stakeholders to review and provide suggestions on the translated material and the website development. We specifically asked the stakeholders to focus on cultural elements of the intervention consisting of language, persons, metaphor, content, concept, goals, methods, and context (Bernal et al., 1995). After the stakeholders returned their review, we conducted Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) with each group of stakeholders, led by the first author. The FGD aimed to clarify and explore stakeholder opinions concerning the psychoeducation material as well as trauma-related mental health problems in Indonesian undergraduate students (common problems, common potentially traumatic events (PTEs), coping strategy, barriers, and support for help-seeking). The detailed results of FGDs are presented in Supplementary Appendix 1.

2.1.3. Phase II: integrating generated information with theory and empirical and clinical knowledge

We utilised all information provided by stakeholders as a reference for conducting phase II. During this phase, we combined the information gathered from the stakeholders with the theory, literature, and clinical insights from previous experience in conducting psychological interventions within an Indonesian setting. We discussed all the adaptation aspects with the research team along with the clinical psychologists and revised the material. Afterward, a professional proofreader reviewed the adapted psychoeducation material. Thereafter, we developed the website-based intervention following the stakeholder’s suggestions and research protocol. We adapted the appearance and design from the original website by Mind to be more appropriate for the Indonesian socio-cultural context. Some adjustments to the content and website design were made to make the intervention more accessible, readable, and appealing to target users. We attached practical worksheets alongside the original material to aid users in applying coping strategies in their daily lives. To accommodate the low-speed internet connection in many regions in Indonesia, we replaced the educational videos that were used in the original English version with colourful infographics and motivational illustrations. To be more acceptable in the Indonesian socio-cultural context, we adapted the website's appearance by including pictures and illustrations that represent the socio-cultural diversity in Indonesia, such as female students wearing hijabs, as the representation of the majority religious beliefs in Indonesia (Islam) and people from various cultural ethnicities. The PL programme is also equipped with a login page with a personalised and secure username and password for each participant, a user activity monitoring report to track users’ activity data on the website, and a zoom-in and zoom-out button to maintain inclusivity for visually impaired users.

2.1.4. Phase III: review of culturally adapted clinical intervention by stakeholders and further revision

After adapting the psychoeducation material and developing the website infrastructure, we presented the culturally adapted trauma-related psychoeducation programme (www.pulihkanluka.com) to the stakeholders for further improvement suggestions. During this phase, we received positive feedback from the stakeholders, and they suggested including more infographics on the website in order to increase user engagement. We collaborated with two professional illustrators with formal degrees in psychology to design infographics based on the psychoeducation material and revised the website.

2.1.5. Phase IV: testing the culturally adapted intervention

After the finalisation of the psychoeducation programme revision, we piloted the intervention in nine undergraduate students with trauma-related mental health problems. To ensure the inclusion criteria, we performed a screening check using the Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS) (Frewen et al., 2021; Grace et al., 2023; Oe et al., 2020; Olff et al., 2020; Primasari et al., 2024; Rossi et al., 2021) prior to the pilot. During this step, we focused on evaluating the website's design and functionality along with gathering real-world user feedback on accessing the PL programme. We provided users with one week of access and requested their feedback during a subsequent interview. In general, we received positive feedback regarding the psychoeducation website’s material, design, and functionality. The stakeholders further suggested some improvements concerning the font and colour of the sub-module thumbnails (website design), the additional motivational quotes, and quiz instruction (psychoeducation material). In terms of functionality, no technical error was reported during the piloting. All user and administrator interfaces worked smoothly. The detailed results of the testing are presented in Supplementary Appendix 2. Key findings of the cultural adaptation process can further be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key findings from cultural adaptation of web-based trauma psychoeducation intervention in Indonesia.

| Cultural Elements | Indonesian cultural elements | Justification for Cultural Adaptations according to Stakeholders’ suggestions | Cultural Adaptation Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian) is the official and national language of Indonesia and has been used as the lingua franca among multi-ethnic-lingual groups in Indonesia. | The utilisation of informal Bahasa Indonesia is deemed the optimal approach for the intervention, compared to the formal style, given its widespread usage and its acceptability to the target users. Positive phrasing tends to resonate well and feels more encouraging for Indonesian readers. The gap in mental health literacy among the Indonesian population should be taken into consideration. |

The intervention is delivered in informal (colloquial) Bahasa Indonesia. Negative and command sentences are rephrased into more positive sentences. Clinical and technical terminology is accompanied by explanations in plain language and concrete examples. |

| Persons | Participants are Indonesian undergraduate students with trauma experience and mental health problems | Utilising illustrations that depict the socio-cultural diversity and mental health problems in Indonesia would be more widely embraced by the intended participants and increase participant’s engagement. | The intervention incorporates images, illustrations, stories, and examples that represent the young generation, the sociocultural diversity, and mental health problems in Indonesia. |

| Metaphors | Among Indonesians, there is a notable tendency to express mental health issues through somatic symptoms. Indonesian young generation also own their unique cultural metaphors, which are shared among their population to reflect their experience with mental health issues. | It is important to include somatic symptoms as cultural metaphors and other population-based-metaphors in the intervention to foster participants’ familiarity, self-understanding, and motivation. | Psychoeducation material includes examples and explanations related to somatic symptoms and other population-based metaphors. Worksheets are provided to facilitate the tracking of sleep disturbances and somatic complaints as well as to facilitate the recognition of the interrelation between emotions, thoughts, behaviours, and physical sensations. |

| Content | Indonesian cultural beliefs and traditions (e.g. collectivist culture, family & community-oriented, religious celebrations). | Indonesian cultural beliefs and traditions could serve as risk and protective factors for mental health issues, help-seeking behaviour, and trauma recovery. Introducing and incorporating these cultural elements are essential as they facilitate participants in recognising the source of risks and protective factors, learning the coping strategy, and optimising their potential. | Integrated cultural elements into the psychoeducation material, such as the examples and explanations related to identifying trauma triggers and coping strategies and seeking help. |

| There is a strong belief among Indonesians that mental health issues are associated with and caused by supernatural phenomena. | This perception could potentially result in delayed and improper treatment and other more serious (mental) health consequences. Therefore, it is imperative to encourage the participants to seek help from (mental) health professionals and emphasize the material on the scientific fact behind trauma-mental health issues. | Adding information to the material related to the importance and strategies to seek help from (mental) health professionals, and elaborate material with the scientific facts related to mental health issues. | |

| Concept | Simple, affordable, and non-intimidating mental health intervention is preferable for Indonesians. Young Indonesian generations, including undergraduate students, are more interested in internet/technological-based intervention. | Web-based psychoeducation interventions provide a secure and less stigmatising environment for target users and have benefits in the economic aspect. Straightforward, pragmatic, and concise mental health interventions are likely to enhance participants’ adherence. The intervention’s accessibility and flexibility enhance its scalability for potential implementation across population contexts. | The concept of the intervention has been justified by stakeholders. |

| Goals | Mental health issues remain overlooked and are considered taboo subjects in Indonesia, thus increasing the stigmatisation and preventing help-seeking behaviour. On the other hand, there is a growing mental health awareness among the young Indonesian generation, including undergraduate students. It is a valuable and gratifying moment for the young generation to be mentally healthy, have higher mental health literacy, and be a valid resource for peers and society. | Enhancing mental health literacy has the potential to foster help-seeking behaviour and promote psychological well-being among undergraduate students. As they become advocates for their peers and society at large, they also experience a greater sense of integration of society. | The goal of the intervention is to increase mental health literacy, help-seeking intention, and psychological well-being, helping the participants to feel more empowered and be more integrated into society. |

| Method | Because of the social stigma targeting individuals with disability in Indonesia, they have often been overlooked in mental health services despite their heightening risk of suffering mental health issues. Within the context of undergraduate students, motivation to participate in the intervention might be hindered because of personal circumstances and academic as well as non-academic loads. |

Individuals with a disability should be facilitated to ensure equality in accessing mental health care. Ensuring intervention adherence is crucial to achieving intervention outcomes. |

Zoom-in and zoom-out buttons are integrated into the website to facilitate visually impaired users. The intervention incorporates weekly reminders to help maintain participant adherence. |

| Context | The majority of Indonesians, including undergraduate students, have limited access to mental health interventions and are not familiar with internet-based interventions as well as mental health systems in Indonesia. Along with the increasing rate of inaccurate and misleading mental health information on the internet, the young population of Indonesia often shows a tendency to formulate inaccurate self-diagnoses without the guidance of professionals. |

The availability of web-based psychoeducation, which is affordable, practical, and understandable, would increase access to care and participant adherence. Self-diagnosis could be dangerous, leading to false diagnoses, delayed and improper treatment, and other more serious (mental) health consequences. Therefore, it is crucial to encourage undergraduate students to avoid self-diagnosis, access credible mental health information, and seek help from (mental) health professionals. |

Psychoeducation material is enriched with practical examples, infographics, supportive quotes, and stories with interesting illustrations that resonate with participants’ cultural backgrounds to make it easy to follow and more appealing. The material also incorporates information related to seeking help that is in accordance with the mental health system in Indonesia and accessible to students. A clear and detailed user manual (in written form and video clip) is provided for the participants, allowing them to access the intervention independently. It is accompanied by Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) embedded on the website. Material related to the negative impact of self-diagnosis and the importance and strategies to find credible mental health information and seek help from (mental) health professionals is added to the website. |

2.1.6. Phase V: synthesising stakeholder feedback and finalising the culturally adapted intervention

Phase five will be conducted after completing the feasibility and acceptability study. We will use the results of the feasibility and acceptability study, both quantitative and qualitative, to revise the psychoeducation intervention.

2.2. Feasibility and acceptability study

2.2.1. Study design

This study is a pilot two-armed Randomised Controlled Trial comparing Pulihkan Luka (PL) programme with Enhanced Usual Care (EUC) with EUC only. We will randomise eligible participants to one of the conditions. Participants in the intervention condition will receive the PL programme with EUC. Meanwhile, the control condition will only receive the EUC. Both conditions will receive access to the PL programme during the follow-up phase. This study is a single-blinded trial. The study protocol has been registered at https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/show/TCTR20230721001 and accepted as a registered report in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology (EJPT)

2.2.2. Participants and sample size

The recommendation is to include a minimum amount of 50 participants for feasibility and pilot studies (Sim & Lewis, 2012). We considered 23% dropouts and loss to follow-up in our sample size calculation (Imel et al., 2013; Listiyandini et al., 2024) and therefore aim to recruit 130 participants in total. We will include participants if they meet the following criteria: (1) age ≥ 18; (2) registered as an undergraduate student who is residing in Indonesia; (3) exposed to at least one potentially traumatic event (PTE) as assessed by the Life Event Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) (Weathers et al., 2013); (4) meet the criteria for experiencing at least one of these mental disorders (PTSD, complex PTSD, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and self-harm) as established with the Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS, see the measurements section); (5) capable of communicating in Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian); (6) able to access the internet. Potential participants will be excluded from participation in this study if they are currently receiving medical or psychological treatment for mental health issues, including psychotherapy, counselling, and psychotropic medications.

2.2.3. Recruitment

We will recruit participants from universities through collaborative efforts with diverse stakeholders in students’ mental health, such as the university Office of Student Affairs, university lecturers, university health centres, mental health communities, and online mental health services. The participants’ recruitment will be promoted through a variety of marketing channels, including social media platforms and student union gatherings. Potential participants can show their interest and register using a secured link (survey.ui.ac.id) mentioned in the advertisement. To guarantee participants’ understanding of the study procedures, we will send a study information letter and provide comprehensive explanations about the study. Prior to all assessments, participants will be required to fill out and sign (digitally) the informed consent form. After the informed consent is secured, we will invite participants to complete an online screening assessment via a secured link managed by Castor (https://www.castoredc.com). Participants will be qualified to join the study if they meet all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. According to our previous studies related to trauma in the Indonesian undergraduate student population, the majority of the participants were women (Primasari et al., 2022, 2024). This aligns with the generally higher proportion of female students in Indonesian universities (Rouf et al., 2022). Therefore, we expect a higher participation rate of female students in our study compared to male students.

2.2.4. Intervention and control condition

2.2.4.1. Intervention: Pulihkan Luka (English: Healing the Wound/PL programme)

In this study, the intervention includes a Pulihkan Luka (PL programme), which is a personalised web-based psychoeducation programme consisting of four to seven independent modules. These modules incorporate informational content and practical coping strategies for trauma survivors with trauma-related symptoms. The content of the PL programme is based on Mind’s web-based mental health psychoeducation programme, which is tailored for the general population of the United Kingdom (UK) and aligns with Whitworth’s recommendations for trauma recovery psychoeducation (Whitworth, 2016). It aims to assist participants in understanding the physical and psychological impact of trauma exposure, help participants acquire effective coping strategies, including seeking (professional) help after exposure to traumatic events, and foster psychological well-being.

The PL programme consists of four standard modules without personalisation (introduction to trauma, PTSD, sleep problems, and self-harm) and three personalised modules (CPTSD, anxiety, depression). The module ‘Introduction to Trauma’ covers an introduction focusing on the concept of trauma, the impact of trauma, resilience promotion, and enhancing the intention to seek (mental) health care. The module ‘PTSD’ focuses on providing information on PTSD, including PTSD symptoms, effects and causes of PTSD, as well as self-care strategies to manage PTSD symptoms. The ‘Sleep Problems’ module emphasises sleep issues and strategies to enhance sleep quality. Subsequently, the ‘Self-harm’ module presents information about self-harm, the causes and effects of self-harm, and self-care strategies to mitigate self-harm. In addition, each personalised module on CPTSD, anxiety, and depression focuses on one trauma-related problem, including symptoms, causes, effects, and self-strategies to alleviate the symptoms. The personalised modules will be assigned to the participants according to their GPS endorsement during the screening process. This approach aims to ensure that the psychoeducation material remains pertinent to the participant’s specific mental health issues. Each module is accompanied by a short mental health literacy quiz, which should be completed after reading the psychoeducation material. While participants can complete each module presented in the PL programme in approximately 30 minutes, it is flexible, and they may take more or less time to finish, depending on individual pace and engagement. Participants are instructed to complete all the assigned modules within five weeks. Each participant will receive a weekly reminder to help them proceed with the reading. The web-based psychoeducation is accompanied with a website engagement’s tracking system to monitor the number of modules completed, time spent per module, and number of logins in each module. Participants in the intervention condition will also be allowed to access Enhanced Usual Care (EUC).

2.2.4.2. Control condition: enhanced usual care (EUC)

We provide a digital leaflet, namely ‘Directory of Mental Health Services for Indonesia Undergraduate Students,’ which contains a list of available referral options for students in Indonesia, including primary, secondary, and tertiary mental health services, private mental health practices, university-based mental health centres, as well as online-based mental health centres. We developed the leaflet based on formal mental health resources available in Indonesia, such as universities, mental health communities and organisations, notable mental health professional associations, and government entities. To ensure the accuracy of the information, an independent Indonesian-based mental health professional has reviewed and curated the leaflet.

2.2.5. Procedure

Prior to randomisation, participants undergo a baseline assessment. An independent researcher based at Amsterdam UMC performs the randomisation using a computerised variable block sequence (2, 4, 6) stratified by gender. Assessments will be carried out at baseline, post-intervention, and 3 – and 6-month follow-ups. All quantitative assessments will be collected using a secure online survey platform, Castor Electronic Data Capture (Castor EDC). Qualitative evaluation using Focused Group Discussion (FGD) will be carried out after a three-month follow-up assessment with 20 randomly selected participants. A monetary incentive is provided for the participants who finish each study phase. The flowchart of the study procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

2.2.6. FGD

The primary objective of the FGD is to delve into participants’ experiences in accessing the intervention and gain a deeper understanding of the acceptability and feasibility of the PL programme. The FGD will cover four main segments: (1) general experience in using the PL programme; (2) challenges, constraints, and potential advantages of utilising the PL programme; (3) recommendations for improvement and exploration of future implementations and prospects for the PL programme; (4) experience in facing mental health stigma and accessing mental health services. Previous studies indicated that female Indonesian students showed more positive attitudes toward professional psychological help compared to male students (Putri & Wilani, 2023). Therefore, we will include both female and male participants during the FGD, exploring factors that help/hinder uptake and participation by males and females. We will also explore the drop-out rate by gender. We will conduct the FGD through online meetings after the three-month follow-up assessment led by a clinical psychologist in the Indonesian language (Bahasa Indonesia). For FGD purposes, we will select 20 participants from the intervention group based on their completion of the assigned modules. We will randomly choose five participants from those who have completed less than 50% of the assigned modules and 15 participants from those who have completed 50% or more of the modules. Twenty selected participants will be divided into rounds, with approximately 10 participants included per round. We plan to include approximately 10 participants per group as this falls within the optimal range of 6–12 individuals for effective discussion (Guest et al., 2017). The discussion for each round will last approximately 90 minutes. The FGD will commence with a brief introduction from the facilitator, ensued by a discussion covering the main topics as mentioned in the guidelines (please see Supplementary Appendix 3), and finalised with a summary of important points, a conclusion, and a closing statement.

2.2.7. Outcome measurements

We present an overview of the study measurements, including the time point of measurements in Table 2. All the questionnaires used in this study were culturally adapted to the Indonesian language (Bahasa Indonesia) and were administered to undergraduate students and trauma survivors.

Table 2.

Study measures and assessment time.

| Topic | Questionnaire | Time of Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | ||

| Demographics | Demographics | X | ||||

| Internet-based mental health service usage history | Internet-based mental health service usage history | X | ||||

| Psychological complaints & treatment history | Psychological complaints & treatment history | X | X | X | X | |

| Traumatic stress symptoms | GPS | X | X | X | X | |

| Life Events | LEC-5 | X | ||||

| Feasibility | MT4C-In Care Feasibility survey | X | ||||

| Acceptability | IIAQ-ID | X | ||||

| User satisfaction | SIN-E-Stress User Satisfaction survey | X | ||||

| Help-seeking | GHSQ | X | X | X | X | |

| PTSD symptoms | PCL-5 | X | X | X | X | |

| Depression symptoms | PHQ-9 | X | X | X | X | |

| Anxiety symptoms | GAD-7 | X | X | X | X | |

| Mental health literacy | Mental Health Literacy | X | X | X | X | |

| Psychological well-being | WHO-5 | X | X | X | X | |

| Insomnia | ISI | X | X | X | X | |

| Global functioning | GPS item 23 | X | X | X | X | X |

Note: GPS: Global Psychotrauma Screen; LEC-5: Life Events Checklist for DSM-5; MT4C-In Care: My Tools 4 Care-In Care; IIAQ-ID: Internet-based Interventions Acceptability Questionnaire-Indonesia; GHSQ: General Help-Seeking Questionnaire; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9: The Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: The General Anxiety Disorder; WHO-5: World Health Organization-Five Well Being Index; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; T0: screening; T1: baseline; T2: post-intervention; T3: three-month post-intervention; T4: six-month post-intervention.

2.2.7.1. Screening measurements

In order to assess any experience of traumatic events, we employ the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5; Weathers et al., 2013). We add a follow-up open-ended question for item 17 (another very stressful event or experience) to validate the participant’s response. The internal consistency of the Indonesian version of LEC-5 was good in previous studies (Marthoenis, Meutia, Sofyan, et al., 2018). We use The Global Psychotrauma Screen (Frewen et al., 2021; Oe et al., 2020; Olff et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020, 2021; Schnyder et al., 2017) to measure the trauma-related symptoms. The GPS includes the domains PTSD (5 items; range 0–5), Complex PTSD (7 items; range 0–7), anxiety (2 items; range 0–2), depression (2 items; range 0–2), insomnia (1item; range 0–1), and self-harm (1 item; range 0–1). A cut-off point of ≥ 3 on the PTSD domain for identifying PTSD, ≥ 5 on the CPTSD domain for identifying CPTSD, ≥ 1 on the anxiety domain for identifying GAD, and ≥ 2 on the depression domain for identifying depression based on the previous validation studies in the Indonesian undergraduate population (Primasari et al., 2024) will be utilised to determine participants’ eligibility. To evaluate the participants’ level of global functioning, we also include item 23 from the GPS. The Indonesian version of GPS has been proven to have good internal consistency in prior studies (α = 0.85; Primasari et al., 2024).

2.2.7.2. Primary outcome measurements

To measure the feasibility of the PL programme, participants will be asked to answer an adapted version of the MT4C-in-Care feasibility survey (Duggleby et al., 2018). This questionnaire inquiries about participants’ experience in accessing the PL programme. We will also measure intervention adherence and uptake based on the number of completed modules and compare it with the established criteria as described in Table 3. Furthermore, for the purpose of monitoring participants’ activity on the psychoeducation website, we track the website log data, including the frequency of log-ins and access duration for each module. We will assess the acceptability of the PL programme through two parameters: (1) the intention to utilise the psychoeducation website and (2) user satisfaction with the programme. We use nine core items from the Interventions Acceptability Questionnaire-Indonesia (IIAQ-ID) (Arjadi et al., 2018), which are slightly modified to align with the psychoeducation context. The internal consistency of the IIAQ-ID was excellent (α = 0.89, 0.95, 0.96), as demonstrated in the previous study (Arjadi et al., 2018). In addition, to assess participants’ satisfaction with accessing the PL programme, four statements from the adapted SIN-E-Stress user satisfaction survey (Carrasco et al., 2020) are administered. The criteria outlined in Table 3 will be used to evaluate the participants’ acceptability to the PL programme.

Table 3.

Feasibility and acceptability criteria.

| Outcome measure | Explanation | Timepoint | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention uptake | Attendance of study participants in one module | Post-intervention | At least 70% of the participants complete the first module |

| Intervention adherence | Attendance of study participants in each module throughout the intervention phase | Post-intervention | At least 50% of the participants complete all modules |

| Feasibility | Experience in accessing the PL programme | Post-intervention | At least 70% of the participants’ scores ≥ 16 on MT4C-in-Care feasibility survey |

| Intention to use the PL Programme | Participant’s intention to use PL programme | Post-intervention | At least 70% of the participants’ scores ≥ 13 on IIAQ-ID |

| User satisfaction | Satisfaction rate and benefits experienced by participants in using PL programme | Post-intervention | At least 70% of the participants’ scores ≥ 16 on SIN-E-Stress user satisfaction survey |

2.2.7.3. Secondary outcome measurements

To measure mental health literacy, we employ the mental health questionnaire that was developed based on PL psychoeducation material and the mental health literacy concept as outlined by Wei et al. (2015). We use the World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5; World Health Organisation. Regional Office For Europe, 1998) to evaluate the well-being status of participants. The Indonesian version of WHO-5 has a high internal consistency (α = 0.83; Sasmito & Lopez, 2020). To evaluate the participants’ help-seeking intention and help resources, we employ The General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ, Wilson et al., 2005). According to the previous study targeting Indonesian undergraduate students, The GHSQ possessed good internal consistency both for the overall scale and domains (non-formal help sources and formal help sources) (α = 0.84, 0.87, 0.75; Prawira & Sukmaningrum, 2020). The presence of PTSD symptoms is measured using The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., 2015). Psychometric testing in the previous study of the Indonesian population indicated excellent internal consistency with a coefficient alpha of 0.93 (Asti, 2015). To assess the severity of the depressive disorder, we utilise The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002), which has good internal consistency in previous studies in Indonesia (α = 0.72; van der Linden, 2019). We use The General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) to assess the symptoms of general anxiety (Spitzer et al., 2006). The Indonesian version of the GAD-7 has excellent internal consistency (α = 0.86; Budikayanti et al., 2019). Additionally, we employ The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Bastien et al., 2001), which has excellent internal consistency (α = 0.92–0.98; Swanenghyun et al., 2015) in order to assess the severity of insomnia symptoms.

2.2.7.4. Other measurements

We incorporate some demographic questions to record information on gender, age, domicile location, ethnicity, and income level. To assess travel distance to (mental) health services and previous utilisation of internet-based mental health services, five questions (numbers 3 and 18–21) from the IAQD-ID questionnaire (Arjadi et al., 2018) are utilised. We also added questions related to the participant's mental health treatment history, including the nature and duration of past treatment, the mental health professionals involved in providing treatment, and the specific mental health concerns that prompted the seeking of treatment in order to investigate the pattern of participant’s help-seeking behaviour, both prior and during the study trajectory.

2.2.8. Analysis

The analysis will adhere to the intention-to-treat principle to mitigate bias, meaning that all the randomised participants will be included during the analysis. We will employ maximum likelihood estimation to address missing data and check all the statistical assumptions.

Primary outcome parameters and FGD data will be analysed using quantitative and qualitative approaches. Quantitative and qualitative data findings will be integrated and presented using a joint display integrated matrix approach. This method proves advantageous for researchers and readers, facilitating comparisons in findings and the generation of meta-inference (McCrudden et al., 2021). Descriptive statistics will be employed to determine the feasibility of the PL programme, including the intervention uptake and adherence, as well as the intervention's acceptability (user’s intention and satisfaction). Participant’s responses to FGD will be analysed with inductive (bottom-up) thematic analysis. This method allows researchers to discover comparable themes and patterns in the study (Clarke & Braun, 2017). Triangulation and inter-rater reliability checks will be carried out to enhance the accuracy of findings by assigning a second independent coder to perform the coding process.

This study's secondary outcome will be evaluated using linear mixed-effect models with a random intercept and slope (effect of time). A piecewise linear growth curve model will be employed to accommodate non-linear changes over time. This model incorporates time, condition, and their interaction as independent variables, with time being modelled by one slope for the treatment phase (T1-T2) and another slope for the treatment follow-up (T2-T4). Three independent linear-mixed effect models with mental health literacy, psychological well-being, and help-seeking intention as the dependent variables will be used to test the second hypothesis. Furthermore, the third hypothesis will be evaluated using four independent linear-mixed effect models, which include PTSD, depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms as dependent variables. In addition to the main hypotheses, we will also present demographic information, history of trauma exposure, internet-based mental health services utilisation, and travel distance to (mental) health services. We plan to conduct the analyses using IBM SPSS and R. We will adhere to SPIRIT guidelines and the CONSORT recommendation (Chan et al., 2013; Eysenbach & Consort-EHEALTH Group, 2011) in reporting the study results.

3. Discussion

In this paper, we have presented a systematic cultural adaptation of Pulihkan Luka, a web-based trauma psychoeducation intervention. This will be the first cultural adaptation study of web-based trauma psychoeducation for trauma-related symptoms in Indonesia. The adaptation process was carried out meticulously following the FMAP method (Hwang, 2009), which includes knowledge forming and collaboration with stakeholders, information generation with theory and clinical knowledge, stakeholder review, pilot testing, and finalisation. We also focused on eight cultural elements (language, persons, metaphors, content, concept, goals, method, and context). This iterative endeavour involved a diverse array of stakeholders and professionals, including psychologists, members of the mental health community, university students, translators, illustrators, and website developers. The involvement of diverse local experts and community stakeholders in this study is in line with the recommendation of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS; Kaminer et al., 2023) to ensure cultural compatibility of trauma intervention in LMICs. Incorporating cultural elements into trauma interventions could also increase its appeal and engagement to the target users, thereby contributing to its feasibility and effectiveness (Marsiglia & Booth, 2015; Schnyder et al., 2016).

The cultural adaptation addressed both surface-level and deeper-level cultural structures, a practice that is sometimes overlooked in adaptation studies (Marsiglia & Booth, 2015). Surface structure adaptation involves tailoring materials and media to align with the observable and behavioural characteristics of the target population, such as language preferences and clothing styles (Resnicow et al., 2000). In contrast, deep structure adaptation involves integrating social, environmental, cultural, historical, and psychological elements that shape the health behaviour of the target population, including their perceptions of health behaviour determinants (Resnicow et al., 2000). In this study, surface adaptation resulted in the translation of psychoeducational materials to Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian) and the inclusion of visuals and illustrations depicting the cultural diversity and preferred activities of young Indonesians. Furthermore, deep structure adaptation resulted in examples and explanations addressing somatic symptoms. Additionally, the material detailed scientific information related to mental health issues as a response to common perceptions that mental health problems are linked to supernatural phenomena. By addressing both surface and deep cultural levels, as also recommended by Kaminer et al. (2023), we aim to enhance the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention.

Additionally, we outlined the protocol for a study evaluating the intervention’s feasibility and acceptability among Indonesian undergraduate students. In case the intervention proves feasible and acceptable and shows to be effective in future RCTs, it can be easily implemented as the first evidence-based trauma psychoeducation web-based tool in Indonesia. This may hereby contribute to mental healthcare in Indonesia by providing a low-cost and scalable intervention. This intervention is not intended to replace evidence-based treatments for PTSD. Instead, we consider the intervention as a first step in the stepped-care strategy aimed at increasing participants’ knowledge, reducing stigma, suggesting helpful coping strategies, and encouraging participants to seek further (professional) help if needed. Since this study is a first pilot RCT, it is not powered to detect an effect. The objective of this study is not to evaluate the effectiveness of psychoeducation. Instead, this study aims to examine the feasibility and acceptability of web-based psychoeducation as well as to assess the safety and to test out the study procedures in preparation for a larger Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). Furthermore, if the intervention proves to be acceptable, safe, and feasible, further studies with greater statistical power might primarily focus on testing the intervention’s efficacy. The findings of this study can also be utilised to calculate power and provide an indication of the effect of the intervention.

Consistent with numerous previous studies, we have identified barriers, including mental health-related stigma and shame and low literacy among Indonesian undergraduate students during the FGD with 15 selected stakeholders. These challenges hinder individuals with trauma experiences from disclosing about their issues and seeking professional help. Moreover, a previous qualitative study has identified the concept of shame culture within university setting, where individuals feel embarrassed when their actions did not conform to the norms upheld by society (Achmad et al., 2023). Another study also revealed that Indonesian students showed relatively high levels of mental health-related shame (Kotera et al., 2024), resulting in internalised stigma and feeling powerless (Subu et al., 2021). These problems should be addressed by providing psychoeducation in schools/universities and communities (Munira et al., 2023). Particularly with the web-based approach, the intervention potentially offers a safe and less stigmatising environment for individuals to receive initial support, feel accepted, and be encouraged to seek professional care.

Furthermore, taking into account the growing number of internet users in Indonesia (Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia, 2020), internet-based interventions might provide a pragmatic approach to fill the existing mental health gap (Cipta & Saputra, 2022). This approach also holds relevance for Indonesia's higher education landscape, where stakeholders increasingly prioritise enhancing mental health support within university environments. Considering Indonesia’s total of 4593 higher education institutions (Handini et al., 2020), this strategy offers a promising initial step before broader implementation, potentially benefiting diverse users. The insight gained from this research holds significance for developing trauma-related promotion, prevention, and intervention strategies across public mental health settings. Stakeholders participating in the focus group discussions also acknowledged the potential advantages of these findings. Note that a future RCT should include long-term follow-up assessments to study whether the effect of the intervention is sustained.

We also acknowledge a number of challenges that we have experienced during the intervention adaptation process or may arise during the feasibility study. Firstly, we encountered difficulties adapting the psychoeducation material to the target language, especially when accommodating the target users’ cultural nuance and linguistic preferences. Given the discrepancy in reading literacy among the Indonesian population and the lack of additional face-to-face contact or personal supervision during the data collection, it is imperative to provide material in plain language and a natural reading style to maintain theoretical accuracy. Therefore, we collaborated with a professional translator, editor, and stakeholders during the adaptation process and conducted a mini-pilot with target users. This ensures that the target users can read and comprehend the material independently. Secondly, we also observed a high prevalence of mental health stigma in Indonesian society coupled with high academic and non-academic loads on students. These factors could potentially serve as demotivating factors for participating in this study. Thirdly, we suspected potential disruption in accessing the online questionnaire and web-based psychoeducation because of the low quality of internet connectivity in certain regions in Indonesia.

Finally, a number of limitations need to be considered. First, this study might attract the most motivated students, potentially reducing participant adherence to the intervention in broader implementation. To address this issue, we have designed the website with interesting pictures, motivating quotes, practical self-care tips, and worksheets following stakeholders’ recommendations during the adaptation phase. Second, since we aimed to develop this intervention in a manner that can be easily implemented in other settings and populations, we excluded face-to-face interaction, peer support, and personal supervision by mental health professionals or lay counsellors from the programme. Consequently, this approach may lead to more dropouts or lower intervention uptake during the data collection. Third, this study did not involve certain stakeholders, including traditional and Indigenous healers as well as spiritual and religious organisations, during the adaptation process. This decision is based on consideration of the research’s feasibility and potential difference in perspectives regarding the cause and treatment of mental health problems – which might create barriers to professional help-seeking (Subu et al., 2022). Lastly, the study population is limited to university students. Therefore, this study only represents a subset of the Indonesian population. If the intervention proves feasible, acceptable, and effective, further research could examine whether the observed findings generalise to the broader population.

This study has been designed in our endeavour to address mental health illiteracy and the treatment gap in Indonesia. Research related to trauma psychoeducation intervention in LMICs is much needed particularly. We focused on evaluating and delivering Pulihkan Luka, a web-based psychoeducation intervention about trauma and trauma-related disorders customised for Indonesian undergraduate students with the potential for scalability to a broader population at the national level or other LMICs. Systematic cultural adaptation has been conducted for the intervention, ensuring cultural sensitivity. The investigation of the feasibility and acceptability of PL is currently underway. The quantitative and qualitative study outcomes will be used to improve the intervention further (if necessary), ensuring the intervention effectively reaches the intended target audience and serves as a benchmark for further research initiatives, particularly in LMIC settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Anggita Fathidhia Ivana, Anne Shakka Ariyani, and Nabila Irawan for their valuable assistance in the cultural adaptation process of the intervention and the development of the mental health directory.

Glossary

Abbreviations: GPS: Global Psychotrauma Screen; LEC-5: Life Events Checklist for DSM-5; MT4C-In Care: My Tools 4 Care-In Care; IIAQ-ID: Interventions Acceptability Questionnaire-Indonesia; GHSQ: General Help-Seeking Questionnaire; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9: The Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: The General Anxiety Disorder; WHO-5: World Health Organization-Five Well Being Index; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; T0: screening; T1: baseline; T2: post-intervention; T3: three-month post-intervention; T4: six-month post-intervention.

Funding Statement

This study received funding from the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan/LPDP) Ref: S-395/LPDP.3/2019 and Amsterdam Public Health (APH) Global Health Program 2022.001/MdB/EdB.

Author contribution

This study’s design and funding was a collaborative effort involving IP, CH, MS, and MO. Each author provided input on the statistical analysis plan. IP coordinated the adaptation process and drafted the initial version of the protocol and manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical approval and trial registry

The research protocol has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Atma Jaya Catholic University Indonesia (Approval ID 0006R/III/PPE. PM.10.05/072022) and is pre-registered at https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/show/TCTR20230721001.

Data availability statement

We confirmed that we agree to share anonymous data, any digital study materials, and laboratory results for all published results.

References

- Achmad, N., Susanto, H., Rapita, D. D., Zahro, A., Yulianeta, Y., & Fatmariza, F. (2023). Shame culture and the prevention of sexual harassment in university: A case study in Indonesia. Research Journal in Advanced Humanities, 4(4), 90–98. 10.58256/g7ms0h54 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arjadi, R., Nauta, M. H., & Bockting, C. L. H. (2018). Acceptability of internet-based interventions for depression in Indonesia. Internet Interventions, 13, 8–15. 10.1016/j.invent.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASEANStats . (2022). Number of traffic accident casualties (injuries) by road. https://data.aseanstats.org/indicator/ASE.TRP.ROD.E.031

- Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia. (2020). Laporan survei internet APJII 2019 – 2020. https://apjii.or.id/survei

- Asti, G. D. A. (2015). De Psychometrische Eigenschappen van de Indonesische Versie van de PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5-Ind) in Javaanse Populatie [Unpublished master's thesis]. Radboud Universiteit. [Google Scholar]

- Astutik, E., Sebayang, S. K., Puspikawati, S. I., Tama, T. D., & Dewi, D. M. S. K. (2020). Depression, anxiety, and stress among students in newly established remote university campus in Indonesia. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences, 16(1), 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Atwoli, L., Stein, D. J., Koenen, K. C., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2015). Epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: Prevalence, correlates and consequences. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(4), 307–311. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurizki, G. E., Efendi, F., & Indarwati, R. (2019). Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following natural disaster among Indonesian elderly. Working with Older People, 24(1), 27–38. 10.1108/WWOP-08-2019-0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbui, C., Purgato, M., Abdulmalik, J., Acarturk, C., Eaton, J., Gastaldon, C., Gureje, O., Hanlon, C., Jordans, M., Lund, C., Nosè, M., Ostuzzi, G., Papola, D., Tedeschi, F., Tol, W., Turrini, G., Patel, V., & Thornicroft, G. (2020). Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for mental health outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries: An umbrella review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 162–172. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30511-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C. H., Vallières, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benight, C. C., Shoji, K., Yeager, C. M., Weisman, P., & Boult, T. E. (2018). Predicting change in posttraumatic distress through change in coping self-efficacy after using the my trauma recovery eHealth intervention: Laboratory investigation. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e10309. 10.2196/10309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., & Bellido, C. (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(1), 67–82. 10.1007/BF01447045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikker, A. P., Lesmana, C. B. J., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2021). The Indonesian mental health act: Psychiatrists’ views on the act and its implementation. Health Policy and Planning, 36(2), 196–204. 10.1093/heapol/czaa139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, J. I., & Olff, M. (2021). Prevention and treatment of PTSD: The current evidence base. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1824381. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1824381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, P., West, J., Whitney, C., Jordans, M. J. D., Bass, J., Thornicroft, G., Murray, L., Snider, L., Eaton, J., Collins, P. Y., Ventevogel, P., Smith, S., Stein, D. J., Petersen, I., Silove, D., Ugo, V., Mahoney, J., el Chammay, R., Contreras, C., … Raviola, G. (2023). Expanding mental health services in low- and middle-income countries: A task-shifting framework for delivery of comprehensive, collaborative, and community-based care. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10(e16), 1–14. 10.1017/gmh.2023.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A., Chen, S., & Galatzer-Levy, I. R. (2023). Resilience to potential trauma and adversity through regulatory flexibility. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(11), 663–675. 10.1038/s44159-023-00233-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, H., Syarif, A. K., Pedley, R., Irmansyah, I., Prawira, B., Lovell, K., Opitasari, C., Ardisasmita, A., Tanjung, I. S., Renwick, L., Salim, S., & Bee, P. (2021). Improving mental health literacy among young people aged 11–15 years in Java, Indonesia: The co-development of a culturally-appropriate, user-centred resource (The IMPeTUs intervention). Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 15(56), 1–18. 10.1186/s13034-021-00410-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K., & Greenberg, N. (2022). Preventing and treating trauma-related mental health problems. In Lax P. (Ed.), Textbook of acute trauma care (pp. 829–846). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-83628-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K., Weston, D., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2021). Effectiveness and acceptability of brief psychoeducational interventions after potentially traumatic events: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1923110. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1923110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budikayanti, A., Larasari, A., Malik, K., Syeban, Z., Indrawati, L. A., & Octaviana, F. (2019). Screening of generalized anxiety disorder in patients with epilepsy: Using a valid and reliable Indonesian version of generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7). Neurology Research International, 1–10. 10.1155/2019/5902610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, ÁE, Moessner, M., Carbonell, C. G., Catalina Rodríguez, C., Martini, N., Pérez, J. C., Garrido, P., Özer, F., Krause, M., & Bauer, S. (2020). SIN-E-STRES: An adjunct internet-based intervention for the treatment of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder in Chile. CES Psicología, 13(3), 239–258. 10.21615/cesp.13.3.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.-W., Tetzlaff, J. M., Gøtzsche, P. C., Altman, D. G., Mann, H., Berlin, J. A., Dickersin, K., Hróbjartsson, A., Schulz, K. F., Parulekar, W. R., Krleža-Jeric, K., Laupacis, A., & Moher, D. (2013). SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ, 346(jan08 15), e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipta, D. A., & Saputra, A. (2022). Changing landscape of mental health from early career psychiatrists’ perspective in Indonesia. Journal of Global Health Neurology and Psychiatry, e2022011. 10.52872/001c.37413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downs, L. L., Rahmadian, A. A., Noviawati, E., Vakil, G., Hendriani, S., Masril, M., & Kim, D. (2017). A DSM comparative study of PTSD incidence in Indonesia. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 4(12), 200–212. 10.14738/assrj.412.3414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby, W., Ruiz, K. J., Ploeg, J., McAiney, C., Peacock, S., Nekolaichuk, C., Holroyd-Leduc, J., Ghosh, S., Brazil, K., Swindle, J., Forbes, D., Lyons, S. W., Parmar, J., Kaasalainen, S., Cottrell, L., & Paragg, J. (2018). Mixed-methods single-arm repeated measures study evaluating the feasibility of a web-based intervention to support family carers of persons with dementia in longterm care facilities. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4(165), 1–12. 10.1186/s40814-018-0356-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., Fennell, M., Herbert, C., & Mayou, R. (2003). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, a self-help booklet, and repeated assessments as early interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(10), 1024. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach, G., & Consort-EHEALTH Group . (2011). CONSORT-EHEALTH: Improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(4), e126. 10.2196/JMIR.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen, P., McPhail, I., Schnyder, U., Oe, M., & Olff, M. (2021). Global psychotrauma screen (GPS): Psychometric properties in two internet-based studies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1881725. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1881725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z., Burger, H., Arjadi, R., & Bockting, C. L. H. (2020). Effectiveness of digital psychological interventions for mental health problems in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 851–864. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30256-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace, E., Rogers, R., Usher, R., Rivera, I. M., Elbakry, H., Sotilleo, S., Doe, R., Toribio, M., Coreas, N., & Olff, M. (2023). Psychometric properties of the global psychotrauma screen in the United States. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 11(1), 12266215. 10.1080/21642850.2023.2266215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G., Namey, E., Taylor, J., Eley, N., & Mckenna, K. (2017). Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: findings from a randomized study. International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 20(6), 693–708. 10.1080/13645579.2017.1281601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamam, A. A., Milo, S., Mor, I., Shaked, E., Eliav, A. S., & Lahav, Y. (2021). Peritraumatic reactions during the COVID-19 pandemic – the contribution of posttraumatic growth attributed to prior trauma. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 132, 23–31. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer, M., Apolinário-Hagen, J., Fritsche, L., Salewski, C., Zarski, A. C., Lehr, D., Baumeister, H., Cuijpers, P., & Ebert, D. D. (2021). Effect of an internet- and app-based stress intervention compared to online psychoeducation in university students with depressive symptoms: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 24, 100374. 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]