Significance

Water has unique properties compared to other liquids. Understanding its behavior has significant implications in fields ranging from life science to meteorology. The hypothesis of a phase transition between two liquid states with different densities in the liquid metastable supercooled regime can explain some of water’s equilibrium anomalies. Analyzing molecular dynamics simulations, we show that dipolar degrees of freedom are involved in water’s liquid–liquid phase transition, providing a better overall understanding of its behavior. By developing a density functional theory in the mean field approximation holding for polar liquids, we further show that the liquid–liquid and the ferroelectric phase transitions are two sides of the same coin. This study significantly advances our understanding of water’s thermodynamic properties.

Keywords: supercooled water, liquid–liquid phase transition, ferroelectric phase transition, tricritical point

Abstract

The distinctive characteristics of water, evident in its thermodynamic anomalies, have implications across disciplines from biology to geophysics. Considered a valid hypothesis to rationalize its unique properties, a liquid–liquid phase transition in water below the freezing point, in the so-called supercooled regime, has nowadays been observed in several molecular dynamics simulations and is being actively researched experimentally. The hypothesis of ferroelectric phase transition in supercooled water can be traced back to 1977, due to Stillinger. In this work, we highlight intriguing and far-reaching implications of water: The ferroelectric and liquid–liquid phase transitions can be designed as two facets of the same underlying phenomenon. Our results are based on the analysis of extensive molecular dynamics simulations and are explained in the context of a classical density functional theory in mean-field approximation valid for a polar liquid, where dipolar interaction is treated perturbatively. The theory underpins the potential role of ferroelectricity in promoting the liquid–liquid phase transition, being the density-polarization coupling inherent in the dipolar interaction potential. The existence of ferroelectric order in supercooled low-density liquid water is confirmed by the observation in molecular dynamics simulations of collective modes in space-time polarization correlation functions, traceable to spontaneous breaking of continuous rotational symmetry. Our work sheds light on water’s supercooled behavior and opens the door to experimental investigations of the static and dynamic behavior of water’s polarization.

The identification of equilibrium water’s thermodynamic anomalies, notably density () maximum at 277 K, compressibility, and specific heat minima around 310 K and 280 K, respectively (1), has immediately sparked broad scientific interest. A first-order liquid–liquid phase transition (LLPT) between a high-density liquid (HDL) and a low-density liquid (LDL) in the supercooled regime was proposed (2) to explain equilibrium water’s anomalies and polyamorphism (3). The first observation of HDL and LDL water in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is reported in ref. 2. Recently, extensive MD simulations in realistic (4), as well as ab initio neural network (5), models of water have clearly supported the first-order LLPT existence. The first-order LLPT line ends at a second-order critical point (CP). Despite experimental hints (6), direct evidence is challenging due to water’s crystallization tendency near the MD simulations-predicted CP. The Widom line (WL) (7), located in the pressure–temperature thermodynamic plane (, ) region above CP but yet in the supercooled state, has been observed via both MD simulations (7) and experiments (8). Crossing the WL from high , water transforms smoothly from HDL-like to LDL-like configurations (7, 8), while the isothermal compressibility () reaches a local maximum (9). Beyond , different order parameters have been proposed to characterize the LLPT and elucidate its physical origin, mostly based on local structure geometry (10–12). Recent insights, furthermore, indicate that varying degrees of topological order of hydrogen-bond network can distinguish HDL from LDL (13).

The hypothesis of a ferroelectric phase transition in supercooled water stems from a 1977 proposal by Stillinger (14), following the observation of proton ordering in certain ice polymorphs (15). During the same years, measurements of the dielectric constant of supercooled water emulsions at ambient down to T 238 K (16, 17) revealed an increase in dielectric constant as decreases. Ref. 17 emphasized that this trend aligns with divergence at 228 K, close to the WL (8, 9), albeit with a rather small critical exponent. Although the idea persisted over the years—refs. 18 and 19 explore the potential ferroelectricity of equilibrium water—the connection between ferroelectricity and LLPT in supercooled water was not examined. A series of papers (20–22) deal with modeling the free energy of supercooled water in light of a possible ferroelectric phase transition near the WL. The ferroelectric and the liquid–liquid phase transitions were, however, always considered as two distinct and concomitant phenomena. By comparing the expression of the free energy presented in ref. 20 with the one provided in Eq. 3, it becomes clear that the former lacks the density-polarization coupling term, thus undermining the foundational premise to relate ferroelectric and LLPT. In ref. 22, for example, supercooled water was assumed to be a mixture of HDL and LDL, with only LDL presumed to undergo a ferroelectric phase transition. As further support of this, the hypothesis that a ferroelectric phase transition could also occur at the first-order LLPT line has never been considered. Beyond ice polymorphs (15), incipient ferroelectricity has been observed in confined water (23). Interestingly, electrofreezing of water at ambient conditions was observed recently by ab initio MD simulations, highlighting the existence of an amorphous ferroelectric ice (24). On the other hand, dielectric measurements reveal distinct differences in the dielectric properties of high- and low-density amorphous ices (HDA/LDA) (25). Extrapolated from ref. 25, LDA and HDA dielectric constant is, respectively, 10 at 130 K and 4,000 bars, and 130 at same and 6,000 bars.

Reanalyzing the water MD simulations of ref. 4, a distinct correlation between and total polarization magnitude () emerges: While HDL retains paraelectric characteristics, the trend of LDL polarization suggests a ferroelectric character, as shown in Fig. 1. A qualitatively similar result was obtained recently in ref. 26, where simulations based on ab initio deep neural-network force field are presented. Thereby this result is resilient to changes in the MD simulation’s potential and water model. The persistence of the result when moving from an ab initio deep neural-network force field, which includes molecular polarizability, to empirical potentials with rigid nonpolarizable molecules, indicates that the primary effect is due to the orientation of molecular dipoles rather than molecular polarizability. This provides a more solid foundation for our subsequent developments. Though it clearly shows the existence of a correlation between and , this result does not demonstrate what is the role of in the LLPT. Since the dipolar degrees of freedom drawing P, though coupled to positional degrees of freedom, are governed by a different interaction potential, occurrence that distinguishes from other proposed order parameters (10–12), the hypothesis can be advanced that plays an active role, different from that of , in the LLPT. An analogy akin to that of ferroeleastic phase transition in crystals (27, 28) or liquid crystals (29) can be envisioned. On this trail, we first obtain from MD simulations the - phase diagram in the (, ) plane, second, starting from the microscopic interaction potential and treating the dipole interaction perturbatively, we develop a classical density functional theory (DFT) in a mean-field approximation. Unlike previous treatments, such as the notable examples in the Stockmayer fluid (30), our theory uniquely features the emergence of coupling between , the order parameter, and , in the free energy, stemming directly from the dependence of the dipolar interaction potential from the positional degrees of freedom. Interestingly, ref. 31 proposes that the coupling between P and fluctuations can explain some of the nonlocal dielectric properties of water. However, it should be kept in mind that we are dealing with their macroscopic counterparts here, and this coupling cannot explain the emergence of a connection between ferroelectricity and LLPT. Our developments aim rationalizing the LLPT in water, modeled as a polar liquid. It does not exclude that different systems or different water models with different microscopic interactions (32) could lead to the same phenomenology. A similar DFT approach could, in these cases, be applied.

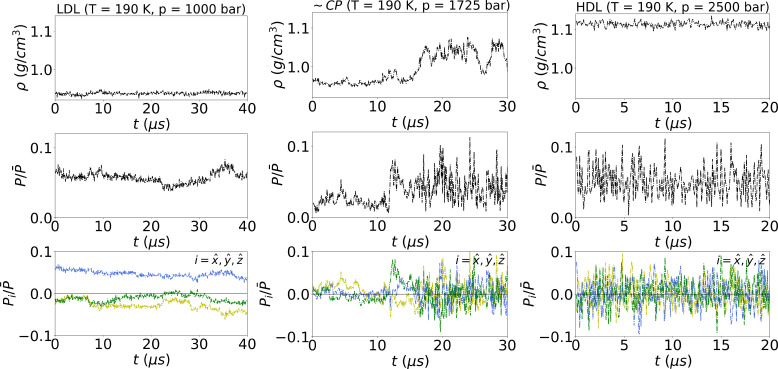

Fig. 1.

Temporal evolution of (Top) (Middle), and (Bottom) across supercooled water in LDL (Left), near CP (center), and in HDL (Right) as obtained from MD simulations, suggesting paraelectric and ferroelectric character for HDL and LDL, respectively. It is . The CP for TIP4P/Ice model has been evaluated (4) to be .

1. Results

1.1. Ferroelectric Character of the LLPT in Supercooled Water.

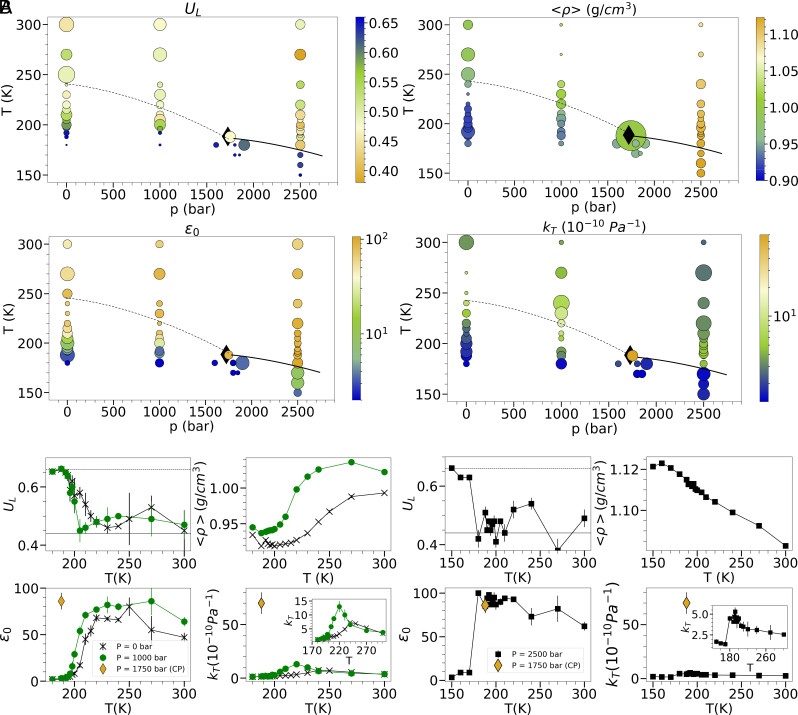

Fig. 1 shows the temporal evolution of , polarization components along the three spatial directions () and obtained by reanalyzing extensive MD simulations of TIP4P/Ice water lasting up to 40 s of ref. 4. A clear correlation emerges between , , and trends. MD simulations employed isothermal–isobaric (NpT) ensemble with molecules. For additional details on MD simulations and analysis, refer to Sections 3.1 and 3.2 and ref. 4. In the LDL phase, all ’s maintain a nonzero value, while in the HDL phase, they show large fluctuations around a zero mean value. At CP = , where the temporal series shows the characteristic bimodal behavior, the fluctuation between LDL and HDL coincides with a transition in and ’s trend. Analyses covering several (, ) points are in SI Appendix, section I. While there is never spontaneous magnetization in a finite system, the ferroelectric phase exhibits a nonzero , as in Fig. 1, as long as the box size of MD simulations exceeds the correlation length of the order parameter. The brackets denote ensemble average. Nevertheless, obtaining a full characterization of the polarization probability distribution is challenging because of spatial domains with varying polarization and orientation transitions. The fourth order cumulant of the polarization probability distribution, so-called Binder cumulant , has emerged as a powerful tool for discerning between paraelectric and ferroelectric phases (33–35). We derived , , the dielectric constant (), and from MD simulations, as detailed in Section 3.2. It is , where is the electric susceptibility. These quantities are shown in Fig. 2, supporting that the LLPT and the behavior at WL in supercooled water involves the dipolar degrees of freedom, as discussed below. i) passes from about , indicative of a paraelectric phase (34), to about , indicative of a ferroelectric phase (33, 34), crossing from high- both the WL (smooth transition) and the first-order LLPT line (sharp transition). ii) gradually decreases as it crosses the WL from high-, transitioning from typical values of HDL to LDL. The transitions of and co-occur. The -transition expected when crossing the first-order LLPT line is obscured by the -variation with at this p. iii) Crossing the WL or the LLPT line from low-, increases to reach its maximum along the WL and the first-order LLPT line. iv) exhibits a maximum along the WL and the first-order LLPT line. v) Along the WL, the maximum value of increases as it approaches , where it reaches a large value consistent with a divergence. Notably, unlike , the peak value of , still reaching large values, remains almost unchanged along the WL and at CP. Considering that and are related to the second derivative of the free energy with respect to and , respectively, this result suggests that the features of the free energy as a function of or differ. Fig. 1 shows the existence of a correlation between and . However, the results in points i)–v) provide additional insights. If were simply coupled to by a linear relationship, and could be used interchangeably as the order parameter of the LLPT. However, this is not the case here because if it were, and would exhibit the same trend.

Fig. 2.

(A) The figure depicts , , , and at different points in the (T, p) plane obtained from MD simulations. Color scale represents the quantities value, symbol size is proportional to the associated error, obtained through block averaging. Full and dashed black lines serve as visual guidance, marking the first-order LLPT and WL, respectively. The diamond symbol marks CP. (B) , , , and as functions of along constant- lines intersecting the WL ( 0 bar, 1,000 bar, Left) and the first-order LLPT line ( 2,500 bar, Right). The values of each quantity at CP are marked by a diamond symbol. A gradual change is observed in and when crossing the WL, while a sudden shift in occurs at the first-order LLPT line.

In SI Appendix, section II, the local spatial distribution of dipoles in LDL and HDL is presented. A complete characterization is beyond the scope of this manuscript, which focuses on the emergence of spontaneous macroscopic polarization in LDL. However, the potential appearance in LDL of a local dipolar order resembling a chiral pattern, in line with the molecular chiral order observed in ref. 36, warrants further investigation. To gain further and complementary insights into microscopic spatial distribution of masses and dipoles, SI Appendix, section III shows the wavevector ()-dependent transverse and longitudinal to static dielectric functions, respectively and , and the static structure factor, , in the HDL, LDL, and close to CP. is the Fourier conjugate variable of the space variable . In this text, bold quantities are vectors, the corresponding nonbold symbols are their magnitudes, and those with a circumflex accent are unit vectors. Averages have been taken over , as for all the quantities introduced in the following. Details are in Section 3.2. The figure in SI Appendix, section III reveals divergences followed by negative values, akin to overscreening phenomena (37, 38). Interestingly, in ref. 31, water’s overscreening was attributed to - fluctuations coupling.

1.2. A Classical DFT for the Ferroelectric LLPT.

In one-component polar liquid, composed of nonpolarizable molecules, the number density of particles at the point having the unit vector as dipole orientation is

| [1] |

where and are, respectively, the center of mass position vector and dipole orientation of the -th particle. and are, respectively, the particle number density without specified dipole orientation and the probability distribution of dipole orientation at point . is the solid angle element. As detailed in SI Appendix, section IV, introducing molecular polarizability does not qualitatively affect the DFT obtained for nonpolarizable molecules. To parameterize the Helmholtz free energy in terms of , we decompose it into two parts: , the free energy of a reference system devoid of dipole interaction, and the perturbative term , which incorporates dipole interaction. The structure of most liquids, especially at high density, is indeed primarily influenced by short-range hard-core pair interaction (39). The perturbative effect will be treated via mean-field approximation, excluding from contributions of correlations (39). Assumption of spatial homogeneity fixes . We furthermore use for the simple ansatz

| [2] |

which can identify paraelectric () and ferroelectric (, with total polarization vector ) states, as detailed in Section 3.3. To facilitate comparison with MD simulations, the NpT ensemble (39) is used. The Gibbs free energy derived from the DFT, with detailed derivation in Section 3.3, is

| [3] |

where , , , , and are positive constants, is the equilibrium volume of the reference system, is its Gibbs free energy, and is the difference between the system’s volume () and . is the external electric field. The potential in Eq. 3 belongs to the class of potentials leading to tricritical points (28, 40), mirroring those of ferroelastic or magnetoelastic crystals (27, 28), where the deformation tensor replaces . Notably, the free energy expression in Eq. 3 and the signs of its coefficients are derived from DFT rather than being arbitrarily chosen to align with the MD simulation results. The key points in the DFT developments, detailed in Section 3.3 are i) the positional disorder of the liquid which, combined with the microscopic expression of the dipolar potential interaction, leads to the potential cancellation of the coefficient of the term in Eq. 3; and ii) the -Taylor expansion of around the density of the reference system , which, given the characteristics of the dipolar interaction potential, yields the coupling term. The dipolar interaction potential in Eq. 26 depends indeed on the vector distance between two dipoles in the liquid. This introduces a dependence of on and, through the -Taylor expansion, leads to the (or in the NpT ensemble) coupling term. Note that the sign of the coefficient in front of the coupling term is also determined, beyond the features of the dipolar potential interaction, by positional disorder. The equilibrium values of and , and , are determined through a variational principle,

| [4] |

| [5] |

It follows

| [6] |

The first term in Eq. 6 represents the liquid’s response to applied , leading to compression, indicated by a negative contribution to . The second term shows that at a given , the system’s equilibrium volume is larger when than when . Consequently, a ferroelectric phase exhibits lower density than a paraelectric phase. Eq. 6 formalizes the presence of a ferroelectric LDL phase and a paraelectric HDL. The sign of the coefficient of the coupling term in Eq. 3, which is ultimately determined by positional disorder as discussed in Section 3.3, is essential. It establishes that the HDL is paraelectric and the LDL is ferroelectric, rather than the reverse. It is also noteworthy that the relationship between and established by Eq. 6 is not linear but quadratic. Beyond the detailed calculations presented in Section 3.4, this fact ultimately explains the different behaviors of and along the WL. It demonstrates that, according to DFT and consistently with MD simulations discussed in Section 1.1, and (or in the NpT ensemble) are not interchangeable order parameters. We are interested in the possible appearance of spontaneous polarization for . The basic mechanisms underlying the phase transitions associated with the free energy in Eq. 3 are briefly discussed below. The vanishing of the coefficient in front of the term induces a ferroelectric transition. The emergence of spontaneous polarization then leads, via Eq. 6, to a LLPT. By inserting Eq. 6, which directly results from the coupling, into Eq. 3, it becomes evident that the coefficient in front of the term can also vanish, as explicitly shown in Section 3.4. The simultaneous cancellation of the coefficients of the and terms gives rise to the existence of the tricritical point, whose occurrence remains thus linked to the existence of the coupling. The - phase diagram in the (, ) plane associated with Eq. 3 is obtained by analyzing the stability of solutions, Eqs. 4 and 5, set by the conditions . See Section 3.4 and SI Appendix, section V for detailed discussions. A schematic representation is shown in Fig. 3, with comments below.

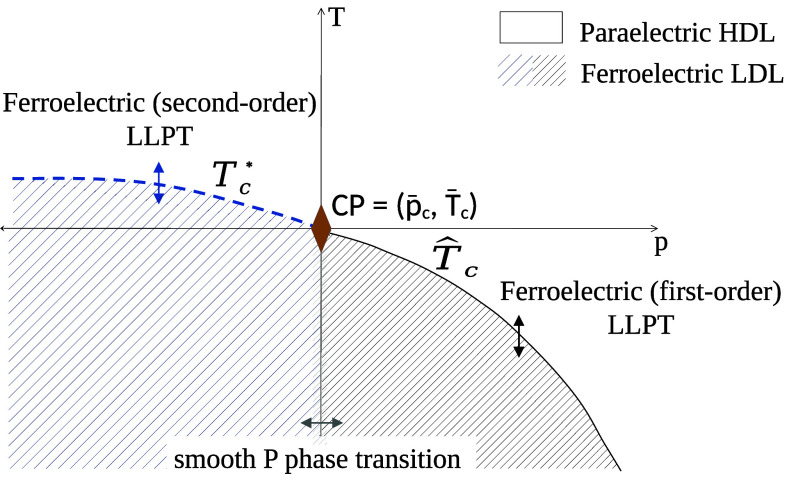

Fig. 3.

Pictorial representation of the phase diagram of the polar liquid in the pT plane obtained from mean-field DFT. is marked by a diamond symbol. For a first-order LLPT is predicted at , represented by a full black line. For a second-order ferroelectric LLPT is predicted at , marked by a dashed blue line. For the theory predict a ferroelectric phase. A smooth transition in the value is predicted upon crossing the line . The two ferroelectric phases with different values are distinguished in the figure by varying degrees of texture’s line density.

Ferroelectric (first-order) LLPT. For constant at , a first-order ferroelectric LLPT is predicted. The following points support evidence for the first-order nature. i) By lowering until , switches abruptly from to (see Table 1 in Section 3.4), and consequently shifts to . ii) There exists a -range above and below , where the ferroelectric LDL and the paraelectric HDL, respectively, are metastable (see Table 1 in Section 3.4). iii) Along the curve , the two phases are both stable and coexist. iv) At , neither the nor diverges, but both reach a local maximum. v) At , the end point of the first-order phase transition, the - and -difference between the two phases goes to zero, while and diverge. Comparing with MD simulations in Section 1.1 identifies as the first-order LLPT line.

Ferroelectric (second-order) continuous LLPT. At constant , the theory predicts a second-order ferroelectric phase transition at . The order parameter increases continuously from zero for (see Table 2 in Section 3.4). decreases continuously according to Eq. 6, indicating a simultaneous continuous -transition. At , diverges. Relevantly, however, the theory predicts reaches a maximum rather than diverging at . Along the curve , increases with increasing until it diverges at . Details are in Section 3.4. Though a finite scaling analysis is required to confirm divergence in MD simulations, the theory accurately predicts the , , and trend at the WL. This consistency supports identifying the WL with the curve .

Smooth polarization magnitude phase transition. For , the system exhibits a ferroelectric phase. However, crossing the line at a given with increasing , gradually increases and V decreases (refer to Tables 1 and 2 in Section 3.4). No singular behavior occurs in or . Observing this transition in MD simulations is challenging due to the overlapping changes in and when increases at fixed . Also, measuring in MD simulations is demanding, as a nonzero average value is strictly only apparent in the macroscopic limit. Thus, we have not pursued this.

Table 1.

Equilibrium values of for the thermodynamic potential given by Eq. 3 for , i.e.,

| stable | – | |

| stable | metastable | |

| metastable | stable | |

| – | stable |

A dash indicates that the solution is not stable.

Table 2.

Equilibrium values of for the thermodynamic potential given by Eq. 3 for , i.e.,

| – | stable | |

| stable | – |

A dash indicates that the solution is not stable.

In the proposed theoretical framework, the CP in supercooled water is identified as a tricritical point, leading to critical behavior distinct from that of an ordinary second-order phase transition in the three-dimensional Ising model. According to mean-field theory, a second-order phase transition occurs at the tricritical point, but with distinctive critical exponents and , which describe the behavior of the order parameter as T approaches the critical T from below and for infinitesimal changes in the conjugate field. For a tricritical point, and , while for an ordinary second-order phase transition, and (28). Experimental or numerical determination of these critical exponents at CP could validate the tricritical phase diagram scenario. Note that the order parameter referred to here is , for which the coefficients of the second- and fourth-order terms in the expansion vanish at the triciritcal point. Since from Eq. 6, is proportional to , the behavior of near CP as , in the tricritical phase diagram scenario would result in , matching that of the three-dimensional Ising model. Interestingly, monitoring the dependence of on a weak electric field at CP to determine could help validate the tricritical phase diagram scenario.

Our elementary theory is not conceived to realistically determine the critical ’s and ’s as these may depend on microscopic details, as well as molecular polarizability, that it overlooks. Instead, it demonstrates that the -based tricritical point scenario is qualitatively supported by a polar liquid, aiming to identify the key mechanisms underlying the LLPT in water. A similar rationale supports using the classical TIP4P/ice potential in MD simulations.

1.3. Ferroelectric Order in LDL.

A ferroelectric phase is characterized by the spontaneous breaking of the continuous rotational symmetry group , leading to distinctive behaviors in both the static and dynamic correlation functions of -fluctuations in the direction transverse and parallel to , and , respectively. A detailed discussion is presented in SI Appendix, section VI. If the identification of LDL as a ferroelectric phase is correct, the correlation functions obtained by MD simulations in LDL will thus uncover such features. The following analysis aims to verify this. In Section 3.2, it is described how the correlation functions are obtained from MD simulations. One of the main signs of spontaneous rotational symmetry breaking is the divergence of the -dependent static susceptibility of the so-called symmetry-restoring variable (41), that is in the case of ferroelectricity, as in the macroscopic limit . The static susceptibility of the transverse to polarization fluctuations, , which represents the space correlation function of at time , is thus expected to have this trend. Furthermore, so-called Goldstone modes (41) emerge in , the wavevector and time-dependent correlation function of , representing its space and time correlations. Goldstone modes are propagating, leading to oscillations in time in , with a characteristic frequency that depends on , meaning the dispersion relation is not constant. Detailed analysis is presented in SI Appendix, section VI in the framework of the Mori–Zwanzig memory function formalism (41).

Fluctuations in -longitudinal polarization, , can arise from -fluctuations, , whose dynamics is empirically described by the Landau–Khalatnikov–Tani equation (42, 43). This equation predicts collective modes, also known as Higgs-like modes (44), in the correlation function of , exhibiting propagating behavior with a linear dispersion relation at moderately small values (42), changing to constant as . Goldstone-like and Higgs-like modes can coexists (44).

Unlike what might be expected, a coupling between and is possible. It can arise from the constant-modulus principle (40), which establish that lowest-order fluctuations satisfy the condition (40). The onset of a polarization fluctuation in the direction transverse to will induce a fluctuation in the direction longitudinal to to preserve constant, and vice versa. It has relevant implications on the static susceptibilities, leading to a divergence also on the static -longitudinal polarization susceptibility, , for but as (40). Concerning dynamical correlation functions, propagating Goldstone modes are still present in but they are not induced in by the coupling between and established by the constant-modulus principle. Instead, holding the constant-modulus principle, spontaneous fluctuations in generate a collective mode both in and , with the same dispersion relation. Further details are provided in SI Appendix, section VI. Finally, if a collective mode emerges in , it corresponds to a mode in the density correlation function due to the coupling between and , see Eq. 3.

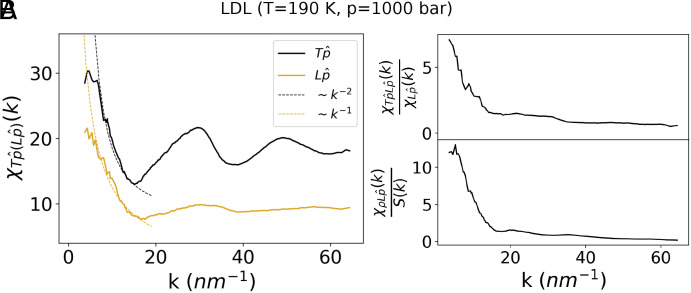

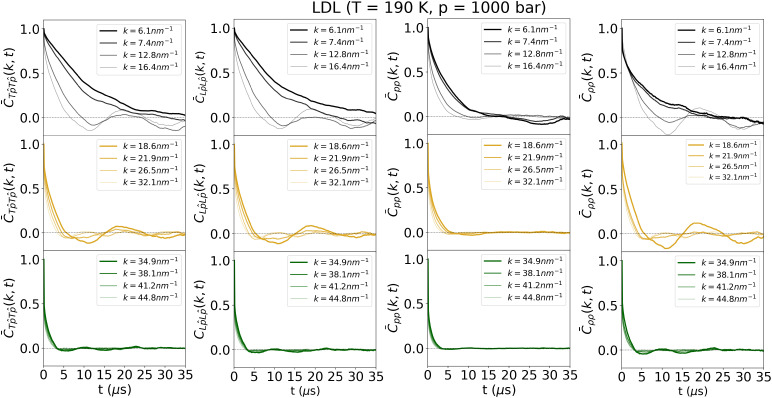

The predictions above find qualitative confirmation in the analysis of MD simulations. Specifically, i) both and in Panel A of Fig. 4 show a significant enhancement for , approximately following and law, respectively. ii) , and correlate, as emphasized in Panel B of Fig. 4. iii) Fig. 5 shows that propagating modes in , and , reflecting in a their oscillatory behavior, are present. Oscillations are significantly reduced in , showing that the constant-modulus principle is approximately satisfied. The presence of a propagating mode in both and , from a preliminary assessment, having in both correlation functions the same dispersion relation, linear in , suggests that the observed propagating mode may originate from fluctuations in . Since polarization is conserved, the dispersion relation of Goldstone modes is indeed expected to follow the law, at least in the limit, as in SI Appendix, section VI. However, our qualitative analysis and the -range accessible with current MD simulations do not allow us to exclude the possibility of coexistence between Higgs-like and Goldstone-like modes. As shown in SI Appendix, section VII, where different points of the (, ) plane are analyzed, in HDL propagating modes vanish, and correlation functions decay to zero on a timescale much shorter than .

Fig. 4.

(A) Static susceptibilities , in LDL as a function of k. Both and show significant enhancement as k → 0, following trends approximately proportional to k−2 and k−1, respectively, as indicated by the dashed lines. This behavior is consistent with predictions for a ferroelectric phase characterized by the spontaneous breaking of the O(3) symmetry group. (B) The Upper graph shows the static correlation between and , represented by , over in the LDL phase. The Lower graph depicts the static correlation between δρ and over S(k) in LDL. A correlation between and δρ emerges, in particular, at moderately small ks.

Fig. 5.

From Left to Right: , , , at different values. All quantities are normalized to their value at , being . The oscillatory behavior in and , with characteristic frequency varying with k, indicates the presence of a collective propagating mode, consistent with the existence of a ferroelectric phase leading to the spontaneous breaking of the symmetry group. Oscillations are significantly reduced in , suggesting that the constant modulus principle is approximately satisfied. The appearance of a propagating collective mode in highlights an existing correlation between and , as also emphasized in Panel B of Fig. 4.

2. Conclusions

The analysis of MD simulations from ref. 4 alongside the construction of a classical DFT for polar liquids under mean-field approximation highlighted the role of dipolar degrees of freedom in the first-order LLPT and in the behavior around the WL. Consistently with a second-order ferroelectric phase transition, the theory predicts a divergence at the WL. A finite-size scaling analysis is needed to confirm the divergence of in MD simulations. The mean-field treatment proposed here is not expected, however, to describe the real critical exponents (17) properly. Remarkably, it was recently shown that anharmonicity in the Gibbs free energy, akin to Eq. 3, in the ferroelectric phase can lead to fluctuations with a nonzero ensemble average. These fluctuations could reduce and, consequently, suppress the divergence of . Another hypothesis, which might explain the possible lack of divergence, is the occurrence of an improper ferroelectric phase transition (27), where the order parameter has multiple components, and the low- phase exhibits pyroelectric properties. An interesting choice for the order parameter components could be classifiers of topological order degree, introduced in ref. 13. The lower entanglement of the hydrogen-bond network in LDL compared to HDL (13) could favor dipole alignment. Ref. 45 suggested a two-order-parameter description for supercooled liquids.

This study disregards the potential impact of nuclear quantum effects on the LLPT in supercooled water. As discussed in refs. 46 and 47, nuclear quantum effects can manifest in the reorentational dynamics of water and in the strength of hydrogen bond network, possibly being relevant for realistically locating the critical lines and CP in the plane, providing more reliable guidance for laboratory experiments. Since, furthermore, nuclear quantum effects have been observed in proton dynamics of water under electric field (48), an interesting question arising is whether quantum fluctuations might reduce the ferroelectric order in the LDL and smooth the classically predicted divergence of at the WL, giving rise to phenomena of incipient ferroelectricity. A comparative finite-size scaling analysis between quantum and classical MD simulations of at the WL, in particular at high ’s near CP, where quantum fluctuations are expected to impact the critical behavior (49, 50), could shed light on this point. Nuclear quantum effects can impact also the critical exponents (49).

Our analysis suggests that experimental validation of the LLPT in water can involve analyzing dielectric properties. It can be, furthermore, investigated whether an electric field can induce LLPT in water (51), and its relationship with the and -induced LLPT analyzed here.

Since Pauling in 1935, attributing residual entropy in hexagonal ice to configurational proton disorder (52), the concept of frustration and disorder in dipole-lattice models of ice (53) was introduced. It would be intriguing to explore whether positional and dipolar orders compete. A phase featuring dipolar order and structural disorder in LDL might correspond to one with structural order and dipolar disorder in hexagonal ice. This presumption is supported by the observation that the vanishing of the term in the free energy, as derived from our DFT developments, results from positional disorder. Finally, an alternative perspective worth considering is a glass transition in the dipolar degrees of freedom, leading to the LDL phase. This aligns with observations that in systems with quenched spin disorder is comparable to that with ordered spins (54). Nevertheless, possible existence of residual order must be considered, given the nonzero value of observed in MD simulations. If a maximum rather than a divergence were confirmed in , it would further bolster this idea. The observed propagating collective modes in the polarization correlation functions may be linked to the breakdown of replica symmetry, possibly accompanying the dipole glass transition (55).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. MD Simulations of TIP4P/Ice Water.

The MD simulations analyzed here are the same of ref. 4, where further details can be found. The MD simulations, performed with GROMACS, employed the classical TIP4P/Ice water model (56) with molecules in NpT ensemble, using a time-step of . This model features rigid molecule geometry with a dipole moment of . Nosé–Hoover thermostat and the isotropic Parrinello–Rahman barostat were used with characteristic time scale around, respectively, 10 ps and 20 ps. Electrostatic interactions were calculated by the particle mesh Ewald method with a cutoff distance of nm. Van der Waals interactions has the same cutoff.

3.2. Analysis of MD Simulations.

The vector at each configuration, identified by a given t, is obtained from MD simulations as follows:

| [7] |

where identifies the atoms of the -th molecule, i.e., the two hydrogen (H), one oxygen (O) atom, and the M-site particle (56). The charge of the particles is with and . is the unwrapped coordinate of the -th particle of the -th molecule. It has been verified that , at each configuration. and are, respectively, obtained as

| [8] |

| [9] |

is the Boltzmann constant and the vacuum permittivity. The ensemble average is obtained from MD simulations by making use of the ergodicity hypothesis, thus, , where is a generic observable, with , is the time step and is the time-length of MD simulations. In the present case, for all the probed points in the (, ) plane. The value of in a paraelectric and ferroelectric phase are established following the observations below, in analogy with the corresponding magnetic cases. In the paraelectric phase, stochastic Gaussian fluctuations centered around a zero value result in as for model (34). In the present case with , . In the ferroelectric phase, where a nonzero set in, , (33, 34).

The static structure factor is obtained from MD simulations as

| [10] |

where the -fluctuations . The vector is the vector position of the center of mass of the -th particle. The symbol ∗ states for complex conjugate. The components of k are derived from the expression , with and . is the time-averaged simulation box size at a given thermodynamic point. Using instantaneous values of does not induce any substantial change. It is nm, thus, nm−1. To obtain in SI Appendix, section III and Fig. S6, averages have been taken over different . Further averaging within a , with , k-interval centered around a specific has been done to enhance the visual examination without altering the overall trends of the quantities represented. The same averaging procedure is applied to all the static and dynamic correlation functions.

The nonlocal static susceptibilities, transverse and longitudinal to , are obtained from MD simulations as

| [11] |

where the symbol “” represents scalar product. It is

| [12] |

| [13] |

| [14] |

where . The definition of above is preferred to , because the latter yields less accurate results at finite due to the approximation of extended molecular dipoles as point dipoles (38). As for the definitions given above, are related to the space-dependent fluctuations. are obtained from as follows: and (38, 57).

The nonlocal static susceptibilities are obtained from MD simulations as

| [15] |

It is

| [16] |

| [17] |

| [18] |

Strictly, it holds that and . In finite-size systems we approximate as . It follows that the value of cannot be obtained from MD simulations. Instead, we have defined above. Consequently, . The electric susceptibility remains finite in the ferroelectric phase.

The static correlations , , computed to unveil static correlation between , , are obtained from MD simulations as

| [19] |

| [20] |

The dynamic correlation functions are obtained from the expressions:

| [21] |

| [22] |

| [23] |

They are computed with a time interval .

3.3. Setting the DFT of Ferroelectric LLPT.

The free energy of a reference system without dipole interaction, , and the extra free energy term, , accounting for dipole interaction in mean-field approximation, i.e., neglecting contribution of correlations (39) are, respectively,

| [24] |

| [25] |

where is the infinitesimal element of solid angle. The integral is extended to the whole solid angle. To streamline the notation, we assume here . arises from the internal energy of the reference system along with the entropy term of the positional degrees of freedom. The second term on the right-hand side of Eq. 24 represents the dipole orientational entropy (30). Though noninteracting, dipoles are still present in the reference system. The dipole interaction in Eq. 25 is

| [26] |

where , is a unit vector at the point . Because of spatial homogeneity assumption, . To solve the mean-field DFT model, specifically, to find the equilibrium value of through a variational principle, we use the ansatz in Eq. 2 for the dipole orientation distribution,

satisfies . If , the polar liquid show a nonzero total polarization , otherwise the system is isotropic and is the uniform distribution. is assumed to be small, i.e., small deviations from system’s isotropy are considered. The -Taylor expansion around zero of in Eq. 24 and the computation of in Eq. 25 yield, respectively:

| [27] |

| [28] |

, which are independent of both and as is assumed to be so, are positive constants. We expanded up to sixth order in since lower-order coefficients can be zero. To obtain Eq. 28, due to positional disorder, a uniform distribution of the angle between and is assumed. This leads to a negative integral in Eq. 25, thus setting . There is no Taylor series truncation because, given the functional form of the dipolar interaction, higher-order terms in -powers are zero. Implicitly, due to the repulsive short-range term in the reference system’s interaction potential, ensuring the integral over to be finite. Note that it is the dependence of on to generate the density dependence of . Otherwise the double space integration in Eq. 25 would simply have resulted in an coefficient in Eq. 28. slightly deviates from the reference system’s density, , due to the slight influence of dipole interactions on it. Consequently, and in Eqs. 27 and 28, respectively, can be given by a Taylor series in . The -Taylor expansion around of and , truncated to lowest order, leads to

| [29] |

| [30] |

It is . Since is the equilibrium density of the reference system, , and . The single and double prime notation denotes, respectively, the first and second derivatives of in . It is . because an increase in , resulting in a decrease, leads to an increment of the integral in Eq. 25, given Eqs. 2 and 26, and the assumption of a uniform angle distribution between and endorsed above. Finally, considering that ,

| [31] |

The constants in Eq. 31 have been redefined, retaining, however, the same names as before. The thermodynamic potential in the NpT ensemble (39), we want to use here, is the Gibbs free energy . changes are induced by variations, yielding and . Featuring an external electric field conjugate to , we obtain Eq. 3. The term in Eq. 3 includes the additive term . Furthermore, it has been assumed that for a given , there exists a value of , see Eq. 31. We neglect the dependence of for sake of simplicity. Since at , the coefficient in front of becomes zero, for near , we neglect the dependence of all the other coefficients. The dependence of is also irrelevant to our aim. Consequently, , , , and are positive constants. in Eq. 31 still depends on . For sake of simplicity, we assume with . In Eq. 3, the factors like in front of have been introduced for convenience.

3.4. The Variational Principle Solution for the DFT Mean Field Model.

With the thermodynamic potential provided in Eq. 3, the equilibrium values of and , and respectively, are determined through the variational principle, establishing that at equilibrium the thermodynamic potential must be minimized, leading to Eqs. 4 and 5. Eq. 6 further outlines the link between and . By inserting the value of , Eq. 6, into Eq. 4 it is obtained

| [32] |

It is convenient to define

| [33] |

| [34] |

is the temperature at which the term proportional to in Eq. 32 disappears. There exists a at which , causing, instead, the term proportional to to become zero in Eq. 32. We further define

| [35] |

| [36] |

The solutions of Eqs. 4 and 5 are stable if for and , and are positive, i.e.,

| [37] |

We are interested to the possible appearance of spontaneous polarization when . From Eqs. 4, 5, and 37, it is found

| [38] |

| [39] |

and are implicitly defined in Eq. 39. It is because is by definition the equilibrium volume of the reference system. The values of , satisfying the stability conditions Eq. 37, are reported in Tables 1 and 2 for , respectively, larger and smaller than . The corresponding value of can be obtained from Eq. 6. For , two stable solutions are found in the ranges specified in Table 1, one of which is metastable as deduced by calculating for each solution. For only one stable solution exists for both and . At a given , the difference unless , where . The values of and in Table 1 are

| [40] |

| [41] |

Further details are reported in SI Appendix, section V. In defining a state as stable, we overlook the fact that the liquid state itself is metastable for ’s below the melting point. The behavior of at and along the WL is obtained in the following. For , . From Eq. 39, it is

| [42] |

As , from Eq. 39, we find , indicating an increase in due to the reduction caused by the temperature decrease. As , according to Eq. 42, also increases. Furthermore, Eq. 42 demonstrates that remains finite at , where it reaches a maximum, as inferred from the observations above. Along the curve , where is maximum, . Considering the definition of in Eq. 34 and of in Eq. 35, it emerges that increases by moving along the curve by increasing until it diverges at . We can assume to be constant in a sufficiently small neighborhood of .

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Francesco Sciortino for providing the molecular dynamics simulations data and engaging in insightful discussions. We thank Enzo Marinari, Paolo Pegolo, Alessandro Laio, and Achille Giacometti for thoughtful discussions. M.G.I. acknowledges the support from Ministero Istruzione Universitá Ricerca—Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale “Deeping our understanding of the Liquid–Liquid transition in supercooled water” grant 2022JWAF7Y. A contribution toward the open access publication charge by Digital Library of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice is acknowledged.

Author contributions

M.G.I. conceived the idea that ferroelectricity can play a role in the liquid–liquid phase transition; M.G.I., J.R., and G.P. discussed, designed, and projected research; M.G.I. performed molecular dynamics simulations data analysis, interpretation and theoretical developments; M.G.I., J.R., and G.P. discussed the results; M.G.I., J.R., and G.P. revised the paper; and M.G.I. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations data utilized in this study are the same of ref. 4. The codes used for the analysis of MD simulation data will be deposited on GitHub repository upon acceptance.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Angell C. A., Water: A Comprehensive Treatise, Franks F. Ed. (Plenum, New York, 1982), p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poole P. H., Sciortino F., Essmann U., Stanley H. E., Phase behaviour of metastable water. Nature 360, 324–328 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellisent-Funel M. C., Teixeira J., Bosio L., Structure of high-density amorphous water. II. Neutron scattering study. J. Chem. Phys. 87, 2231–2235 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debenedetti P. G., Sciortino F., Zerze G. H., Second critical point in two realistic models of water. Science 369, 289–292 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gartner T. E., et al. , Liquid-liquid transition in water from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 255702 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim K. H., et al. , Experimental observation of the liquid-liquid transition in bulk supercooled water under pressure. Science 370, 978–982 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu L., et al. , Relation between the widom line and the dynamic crossover in systems with a liquid-liquid phase transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16558–16562 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim K. H., et al. , Maxima in the thermodynamic response and correlation functions of deeply supercooled water. Science 358, 1589–1593 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sciortino F., Poole P. H., Essmann U., Stanley H. E., Line of compressibility maxima in the phase diagram of supercooled water. Phys. Rev. E 55, 727 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montes de Oca J. M., Sciortino F., Appignanesi G. A., A structural indicator for water built upon potential energy considerations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 244503 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka H., Tong H., Shi R., Russo J., Revealing key structural features hidden in liquids and glasses. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 333–348 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foffi R., Sciortino F., Correlated fluctuations of structural indicators close to the liquid-liquid transition in supercooled water. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 378–386 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neophytou A., Chakrabarti D., Sciortino F., Topological nature of the liquid-liquid phase transition in tetrahedral liquids. Nat. Phys. 18, 1248–1253 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stillinger F. H., Theoretical approaches to the intermolecular nature of water. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 278, 97–112 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg D., Kauzmann W., The Structure and Properties of Water (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1969). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasted J. B., Shahidi M., The low frequency dielectric constant of supercooled water. Nature 262, 777–778 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodge I. M., Angell C. A., The relative permittivity of supercooled water. J. Chem. Phys. 68, 1363–1368 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelton D. P., Are dipolar liquids ferroelectric? J. Chem. Phys. 123, 084502 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pounds M. A., Madden P. A., Are dipolar liquids ferroelectric? Simulation studies J. Chem. Phys. 126, 104506 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menśhikov L. I., Fedichev P. O., The possible existence of the ferroelectric state of supercooled water. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 85, 906–908 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedichev P. O., Menśhikov L. I., Bordonskiy G. S., Orlov A. O., Experimental evidence of the ferroelectric nature of the lambda point transition in liquid water. JETP Lett. 94, 401–405 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedichev P. O., Menśhikov, Liquid-liquid phase transition model incorporating evidence for ferroelectric state near the lambda-point anomaly in supercooled water. arXiv [Preprint] (2012). 10.48550/arXiv.1201.6193 (Accessed 30 January 2012). [DOI]

- 23.Gorshunov B., et al. , Incipient ferroelectricity of water molecules confined to nano-channels of beryl. Nat. Commun. 7, 12842 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassone G., Martelli F., Electrofreezing of liquid water at ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 15, 1856 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson O., Dielectric relaxation of the amorphous ices. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 244115 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malosso C., Manko N., Izzo M. G., Baroni S., Hassanali A., Evidence of ferroelectric features in low-density supercooled water from ab initio deep neural-network simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2407295121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landau L. D., Pitaevskii L. P., Lifshitz E., Course of Theoretical Physics Vol. 8: Electrodynamics of Continuous Media (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, ed. 2, 1960). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaikin P., Lubensky T. C., Principles of Condensed Matter Physics (Cambridge University Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sebastián N., et al. , Ferroelectric-ferroelastic phase transition in a nematic liquid crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 037801 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groh B., Dietrich S., Ferroelectric phase in stockmayer fluids. Phys. Rev. E 50, 3814 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kornyshev A. A., Leikin S., Sutmann G., “overscreening’’ in a polar liquid as a result of coupling between polarization and density fluctuations. Electrochim. Acta 5, 849–865 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan H., et al. , Ferroelectric phase in stockmayer fluids. Nat. Commun. 10, 379 (2019).30670699 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binder K., Finite size scaling analysis of ising model block distribution functions. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter 43, 119–140 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holm C., Janke W., Critical exponents of the classical three-dimensional heisenberg model: A single-cluster monte carlo study. Phys. Rev. B 48, 936 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weis J. J., The ferroelectric transition of dipolar hard spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 044503 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumoto M., Yagasaki T., Tanaka H., Chiral ordering in supercooled liquid water and amorphous ice. Phys. Rev. Lett 115, 197801 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fasolino A., Parrinello M., Tosi M. P., Static dielectric behavior of charged fluids near freezing. Phys. Lett. A 66, 119–121 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bopp P. A., Kornyshev A. A., Sutmann G., Frequency and wave-vector dependent dielectric function of water: Collective modes and relaxation spectra. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 1939–1958 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen J. P., McDonald I., Theory of Simple Liquids (Academic Press, London, ed. 4, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patashinskii A. Z., Pokrovskii V. L., Fluctuation Theory of Phase Transitions (Pergamon Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forster D., Hydrodynamic Fluctuations, Broken Symmatry, and Correlation Functions (The Benjamin/Cumings publishing company, 1975). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang P., Iguchi R., Uchida K., Bauer G. E. W., Thermoelectric polarization transport in ferroelectric ballistic point contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 047601 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Widom A., Sivasubramanian S., Vittoria C., Yoon S., Srivastava Y. N., Resonance damping in ferromagnets and ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 81, 212402 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prosandeev S., et al. , Evidence for goldstone-like and higgs-like structural modes in the model pbmg1/3nb2/3o3 relaxor ferroelectric. Phys. Rev. B 102, 104110 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka H., Two-order-parameter description of liquids: Critical phenomena and phase separation of supercooled liquids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 11, L159 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ceriotti M., et al. , Nuclear quantum effects in water and aqueous systems: Experiment, theory, and current challenges. Chem. Rev. 116, 7529–7550 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkins D. M., Manolopoulos D. E., Pipolo S., Laage D., Hynes J. T., Nuclear quantum effects in water reorientation and hydrogen-bond dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 2602–2607 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassone G., Nuclear quantum effects largely influence molecular dissociation and proton transfer in liquid water under an electric field. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 8983–8998 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vojta M., Quantum phase transitions. Rep. Prog. Phys. 66, 2069–2110 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eltareb A., Lopez G. E., Giovambattista N., Nuclear quantum effects on the thermodynamic, structural, and dynamical properties of water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 6914–6928 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wexler A. D., Fuchs E. C., Woisetschläger J., Vitiello G., Electrically induced liquid-liquid phase transition in water at room temperature. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 18541–18550 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pauling L., The structure and entropy of ice and of other crystals with some randomness of atomic arrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 57, 2680–2684 (1935). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lasave J., Koval S., Laio A., Tosatti E., Proton strings and rings in atypical nucleation of ferroelectricity in ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2018837118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iniguez D., Marinari E., Parisi G., Ruiz-Lorenzo J. J., 3d spin glass and 2d ferromagnetic xy model: A comparison. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 30, 7337–7347 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parisi G., Urbani P., Zamponi F., Theory of Simple Glasses (Cambridge University Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abascal J. L. F., Sanz E., García Fernández R., Vega C., A potential model for the study of ices and amorphous water: Tip4p/ice. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 234511 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dolgov O. V., Kirzhnits D. A., Maksimov E. G., On an admissible sign of the static dielectric function of matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 53, 81–94 (1981). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations data utilized in this study are the same of ref. 4. The codes used for the analysis of MD simulation data will be deposited on GitHub repository upon acceptance.