Abstract

The nucleocapsid (N) protein encapsidates both viral genomic RNA (vRNA) and the antigenomic RNA (cRNA), but not viral mRNA. Previous work has shown that the N protein has preference for vRNA, and this suggested the possibility of a cis-acting signal that could be used to initiate encapsidation for the S segment. To map the cis-acting determinants, several deletion RNA derivatives and synthetic oligoribonucleotides were constructed from the S segment of the Hantaan virus (HTNV) vRNA. N protein-RNA interactions were examined by UV cross-linking studies, filter-binding assays, and gel electrophoresis mobility shift assays to define the ability of each to bind HTNV N protein. The 5′ end of the S-segment vRNA was observed to be necessary and sufficient for the binding reaction. Modeling of the 5′ end of the vRNA revealed a possible stem-loop structure (SL) with a large single-stranded loop. We suggest that a specific interaction occurs between the N protein and sequences within this region to initiate encapsidation of the vRNAs.

Hantaviruses are tripartite, negative-stranded viruses harbored by a variety of rodents in the Muridae family, which are distributed throughout the world. Transmission of these viruses to humans occurs through inhalation of rodent excreta and can result in one of two illnesses depending on the virus, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) or hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) (10). Because of the geographical distribution of the rodent reservoirs of these viruses, HPS has emerged as a significant illness throughout the Americas, while HFRS is limited to the Old World. One of the more severe HFRS illnesses is caused by Hantaan virus (HTNV), which causes death in 5 to 15% of the cases (5, 6).

The hantavirus genome encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (L segment), a nucleocapsid (N) protein (S segment), and two glycoproteins, G1 and G2 (M segment) (11, 12). Minimally, the components of replication include the RdRp, the N protein, and the virus genomic and antigenomic RNA templates. Following entry of the virion into the cytoplasm, the RdRp initiates viral cRNA synthesis from the L, M, and S viral genomic RNAs (vRNAs). Additional vRNA is synthesized from the cRNA. Both vRNA and cRNA are complexed with the N protein throughout transcription and replication, but mRNA is not (3). The cis-acting viral sequences which promote the specific interaction of N with vRNA and cRNA during viral replication are unknown. It is likely that sequences or structures present in the 5′ ends of the RNA molecules would provide a point of nucleation for subsequent encapsidation of the entire genomic or antigenomic segment (8).

Interaction of the HTNV N protein with its vRNA shows little ionic strength dependence (13). However, increase in the ionic strength of the binding reaction greatly reduced the HTNV N protein's affinity for nonviral RNA. In the same study, filter-binding assays demonstrated a moderate binding preference of the HTNV N for the S-segment vRNA compared to an RNA comprising only the open reading frame (ORF) of the S segment and a strong preference for vRNA compared to nonspecific RNA. These studies suggested that the HTNV N protein may specifically recognize its vRNA at a unique structure and/or sequence. Herein, we explore the hypothesis that the HTNV N protein recognizes this signal for encapsidation and assembly of the nucleocapsid. To map the cis-acting RNA sequences required for HTNV N protein interactions, in vitro-transcribed RNA derivatives of the HTNV S segment and synthetic oligoribonucleotides based on the 3′ vRNA end and the 5′ vRNA end were explored. Our results suggest a model for encapsidation of the vRNA that entails both specific and nonspecific interactions with the N protein. We propose that a specific interaction occurs between the N protein and sequences in the 5′ end of the nascent vRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of hantavirus RNA substrates.

HTNV vRNA was transcribed from the vector pGEM1-HTNVS (Connie Schmaljohn, Virology Division, USAMRIID) as described previously (13). A construct containing the 5′- and 3′-terminal untranslated sequences of the S segment, or minipan (pGEM1-MP), was made by partial restriction digestion of pGEM1-HTNVS with BamHI. After digestion, the linearized fragment was gel purified and ligated, resulting in a plasmid that contains 37 bp of the 5′ end and 454 bp of the 3′ end of the gene. A 1,684-bp DNA fragment lacking 12 bp of the 5′ sequences of the S-segment vRNA (pTAR-12) was constructed by PCR amplification of the plasmid pGEM1-HTNVS and cloned into the pTARGET cloning vector (Promega) to produce a deletion construct referred to as Δ12. An ORF RNA was generated by transcription from the HTNV N cDNA (pHTNV-N) cloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites of pET23b. A nonspecific 67-nucleotide (nt) control RNA was transcribed from pGEM7Zf+ as described previously (13). Plasmid DNAs were prepared for the in vitro transcription reactions by digesting pGEM1-HTNV S with XbaI, pHTNV-N with XhoI, pGEM1-MP with XbaI, pTAR-12 with SmaI, and pGEM7Zf+ with SmaI. [32P]UMP-radiolabeled transcripts were produced and purified from linearized plasmids using the MaxiScript SP6/T7 RNA transcription kit (Ambion) as described previously (13).

Oligoribonucleotides.

Oligoribonucleotides were synthesized and high-pressure liquid chromatography purified by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa). Synthesis was performed on a 1 μM scale. The oligoribonucleotides used in the present study are described in Table 1. The synthetic RNAs were labeled at the 5′ terminus with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and purified on quick-spin columns (Roche).

TABLE 1.

Synthetic oligoribonucleotides

| RNA | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| HTNV vRNA(1–39) | 5′-UAgUAgUAUgCUCCCUAAAAAgACAAUCAAggAgCAAUC-3′ |

| HTNV vRNA(1661–1696) | 5′-CgUUgUUCUAgUAgCUCUUUAgggAgUCUACUACUA-3′ |

| HTNV vRNA(1–22) | 5′-UAgUAgUAUgCUCCCUAAAAAg-3′ |

| HTNV vRNA(1675–1696) | 5′-CUCUUUAgggAgUCUACUACUA-3′ |

| HTNV cRNA(1–36) | 5′-UAgUAgUAgACUCCCUAAAgAgCUACUAgAACAACg-3′ |

| HTNV cRNA(1658–1696) | 5′-gAUUgCUCCUUgAUUgUCUUUUUAgggAgCAUACUACUA-3′ |

| Random RNA | 5′-ACCAACAAAgAUgAgUgUUACAgCUCUUgC-3′ |

Lowercase letters were used solely for ease of reading.

UV cross-linking assay.

UV cross-linking assays were performed as previously described (13). Briefly, in standard reactions, 175 ng of HTNV N protein/μl was added to reaction buffer, and reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 37°C. RNA-protein complexes were covalently cross-linked by exposing to 1.8 kJ of UV light in a UV cross-linker (UVC500; Hoefer). Unbound RNA was digested by adding 1 U of RNase V1 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) or 50 U of RNase T1 (Ambion) and incubating for 30 min at 37°C. Reaction products were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Signals were quantified using ImageQuaNT version 4.2 software (Molecular Dynamics).

Filter-binding assay.

The filter-binding assays were done as described previously (13). RNAs were prepared by in vitro transcription in the presence of [α-32P]UTP or synthesized as described above. HTNV N protein was purified as described previously (13). Briefly, HTNV N protein was serially diluted in binding buffer (40 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 40 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 1.5 mM dithiothreitol) to give a final concentration range of 3.5 × 10−9 to 3.5 × 10−6 M. Apparent dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated by fitting a nonlinear binding curve to the empirical data using the Origin program (MicroCal). The apparent Kd corresponds to the concentration of N protein required to obtain half-saturation, assuming that the complex obeys a simple binding bimolecular equilibrium. We assumed that the plateau in the percent binding of the RNA represents complete binding of the RNA, to allow the calculation at half-saturation.

Competition experiments.

Competition experiments were performed by filter-binding assays. A constant concentration of the HTNV N protein (3.5 × 10− 7 M) was incubated with 1 ng of [α-32P]UTP-labeled RNA (0.05 nM) for 10 min at 37°C. Various concentrations (0.5 to 500 nM) of unlabeled RNA were added to the binding interactions, and a further 10-min incubation followed. The reaction mixtures were slot blotted onto nitrocellulose filters as described previously (13). Analyses of competition assays were performed by a nonlinear fit of the data using the Origin program (MicroCal).

Gel electrophoresis mobility shift assay (GEMSA).

One nanogram of 32P-radiolabeled vRNA S segment, prepared as described above, was incubated with a 22.7 μM concentration of purified protein in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 5% glycerol, and 20 U of RNase inhibitor [Ambion]) in a final reaction volume of 20 μl and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Two microliters of sample buffer (80% glycerol and 0.2% bromophenol blue) was added to each reaction mixture, and the reaction products were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel, separated by electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA at 120 V (constant voltage) for 1.5 h, and visualized by autoradiography.

Computer-predicted secondary structures of HTNV S-segment RNAs.

The optimal and suboptimal secondary structures of the HTNV S-segment RNAs were predicted with the RNA secondary structure prediction program mfold, version 3.0 (14).

RESULTS

Determination of the region(s) within the S-segment vRNA that interacts with the HTNV N protein specifically.

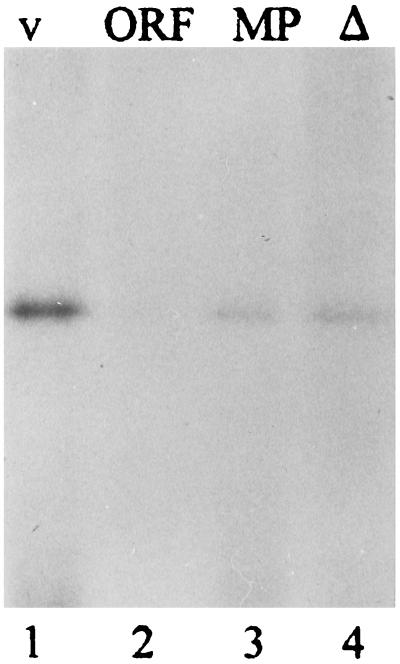

An encapsidation signal had not been previously defined for any of the hantaviral RNAs. Therefore, we were interested in first determining whether any such signal was present in the full-length S-segment RNA. Three deletion mutants were constructed from the HTNV S-segment vRNA: an ORF RNA, which contains no 5′ or 3′ flanking untranslated sequences; a minipan RNA, which represents the region flanking the ORF RNA; and a Δ12 vRNA, which contains a deletion of the terminal 12 nt from the 5′ end of the noncoding region. Each of the RNAs was examined for RNA binding affinity to the HTNV N protein with a UV cross-linking assay (Fig. 1). The binding of the HTNV N protein to its vRNA was greater than that demonstrated with the ORF RNA, which showed a 4.5-fold reduction in band intensity compared to the wild-type vRNA (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 2). The minipan RNA had a 3.0-fold reduction in binding in comparison to the vRNA (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 3). The Δ12 RNA showed a similar decrease in signal intensity compared to the full-length vRNA (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 4).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of the complex formed between HTNV N protein and deletion RNAs by UV cross-linking analysis. The concentration of N protein used in each binding reaction was 3.5 × 10−6 M. Reaction mixtures were assembled in 100 mM NaCl with 5 mM MgCl2 in addition to standard reaction components as described in Material and Methods. Binding reactions were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and unbound RNA was digested by adding 1 U of RNase V1. Signals were imaged with the Molecular Dynamics Storm PhosphorImager and quantified using ImageQuaNT version 4.2 software (Molecular Dynamics). The RNAs used to form the complexes are HTNV S-segment vRNA (lane 1), ORF RNA (lane 2), minipan RNA (lane 3), and Δ12 RNA (lane 4).

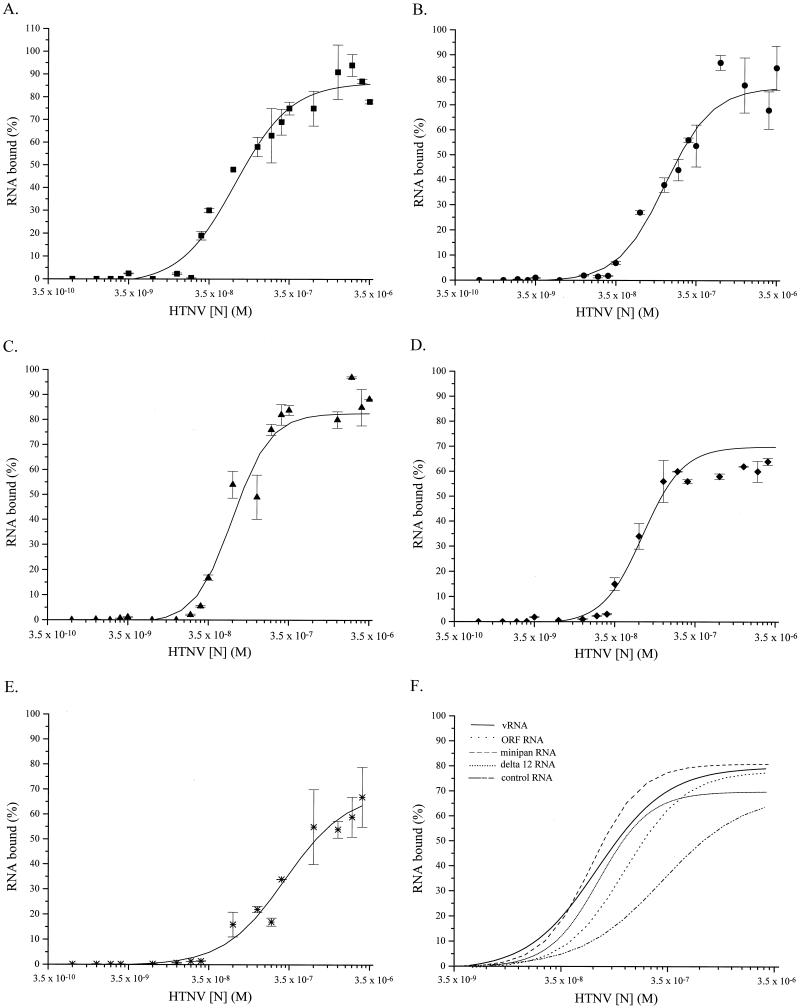

To corroborate the UV cross-linking results, filter-binding experiments were performed with increasing amounts of HTNV N protein and a constant amount of the various deletion RNAs. Data was analyzed using the Klotz plot, and an apparent Kd for each complex was calculated from each binding curve (Fig. 2A to E). The HTNV vRNA showed the greatest affinity for the HTNV N protein with a Kd of 53 nM (Fig. 2A). The Kd of the ORF RNA-HTNV N complex was 270 nM, indicating that this interaction was 5-fold weaker than the vRNA-HTNV N protein interaction (Fig. 2B). The minipan RNA-HTNV N complex and the Δ12 RNA-HTNV N complexes had apparent Kds of 72 and 94 nM, respectively (Fig. 2C and D). Compared to the HTNV N protein-vRNA complexes, the minipan RNA showed a 1.4-fold reduction in binding, while the Δ12 RNA showed a 1.8-fold reduction. The control RNA showed very little affinity for the HTNV N protein (Fig. 2E). A summary of the binding isotherms for each data set (Fig. 2A to E) is shown in Fig. 2F. According to these results, the vRNA was the preferred substrate, followed by the Δ12 RNA, the minipan RNA, and ORF RNA. The UV cross-linking and filter-binding experiments suggested that there are regions in the vRNA that are preferred by the HTNV N protein and that these regions may lie in the noncoding region.

FIG. 2.

Saturation binding curves of various RNA substrates and the HTNV N protein. Binding isotherms were constructed following measurement of the binding of HTNV N protein with full-length S-segment vRNA (A), ORF vRNA (B), minipan RNA (C), Δ12 vRNA (D), and control RNA (E); panel F shows a compilation of data for all RNAs. Binding reaction mixtures were assembled in 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2 in addition to standard reaction components as described in Materials and Methods. 32P-labeled RNA was incubated with the indicated molar concentrations of N protein. The amount of radioactively labeled N protein retained on the filter was calculated relative to maximum radioactivity retained in each experiment. Apparent dissociation constants were calculated by nonlinear curve fitting and correspond to the amount of protein necessary to obtain 50% saturation, assuming that the concentration of free protein is equivalent to the concentration of total protein.

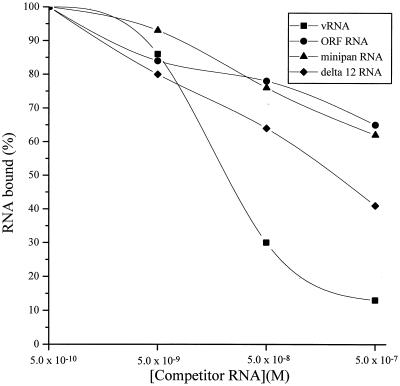

Competition of the HTNV N protein-vRNA complex with viral RNAs.

To further examine the relative contribution of these flanking sequences, we investigated the ability of unlabeled in vitro-transcribed Δ12 RNA, minipan RNA, and ORF RNA to compete with 32P-labeled HTNV vRNA in a filter-binding assay (Fig. 3). A constant concentration of the HTNV N protein (3.5 × 10− 7 M) was incubated with [α-32P]UTP-labeled vRNA (0.05 nM) and increasing concentrations (0.5 to 500 nM) of unlabeled competitor RNA (Fig. 3 and Table 2). As expected, the ORF RNA was not an effective competitor of the HTNV N-vRNA complex. The minipan RNA was not an effective competitor of the HTNV N protein-vRNA complex. However, the Δ12 RNA at 500 nM concentration reduced binding by approximately 60%, which suggested that the removal of nucleotides that have been reported to form a panhandle structure in the 5′ noncoding region are not important determinants in the HTNV N protein-vRNA interaction. This also suggests that the cis-acting determinants are single stranded, since the Δ12 RNA was predicted by mfold to not form a panhandle or double-stranded structure like that observed with the minipan RNA (data not shown). In the UV cross-linking and filter-binding studies, the N protein showed similar affinities for the Δ12 RNA and the minipan RNA. The competition experiments suggest a fundamental difference, however, in how the N protein recognizes each of these RNAs. We suggest that the competition experiments revealed the added affinity of single-stranded versus double-stranded structures in competing for N protein binding, which was not discernible in the UV and filter-binding studies.

FIG. 3.

Competition experiments. Competition experiments were carried out as described in Materials and Methods by filter-binding assays. HTNV N protein was bound to 1 ng of [α-32P]UTP-labeled RNA (0.05 nM) in the presence of variable concentrations (0.5 to 500 nM) of vRNA, ORF RNA, Δ12 RNA, and minipan RNA. Analyses of competition assays were performed by fitting a binding curve to the empirical data using the Origin program (MicroCal).

TABLE 2.

Competition analysis of HTNV vRNA-N protein interactions

| Competitor RNA | % Binding in presence of molar excess (fold) of competitor RNAa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 10 | 100 | 1,000 | |

| vRNA | 100 | 86 | 30 | 13 |

| ORF RNA | 100 | 84 | 78 | 65 |

| Minipan RNA | 100 | 93 | 76 | 62 |

| Δ12 RNA | 100 | 80 | 64 | 41 |

Values were calculated from the percentage of the labeled vRNA bound in the presence of the unlabeled competitor RNA.

Binding isotherms of HTNV N protein with synthetic HTNV vRNA and cRNA oligoribonucleotides.

The experiments performed indicated that sequences in the untranslated regions were preferred sites of interaction for the HTNV N protein. To determine if a specific binding affinity could be mapped to these sequences, binding isotherms for six distinct hantaviral single-stranded RNA substrates and a random RNA substrate were analyzed (Table 1). Three duplex RNAs that were examined were vRNA(1–39)/vRNA(1661–1696), vRNA(1–22)/vRNA(1675–1696), and cRNA(1–36)/cRNA(1658–1696). The dissociation constants for each binding isotherm are summarized in Table 3. The apparent Kds for full-length and the other RNAs tested earlier are also summarized. The HTNV vRNA(1–39) showed the greatest preference for the N protein, with an apparent Kd of 132 nM. cRNA(1–39)/cRNA(1658–1696), vRNA(1–39)/vRNA(1661–1696), cRNA(1–39), cRNA(1658–1696), vRNA(1–22), random RNA, and vRNA(1675–1696) showed an approximate 2- to 3-fold reduction in binding compared to HTNV vRNA(1–39). The Kd of vRNA(1661–1696) was 624 nM, or 4.7-fold greater than the constant for the vRNA(1–39)-HTNV N protein interaction (Table 3). The vRNA(1–22)/vRNA(1675–1696)-HTNV N complexes had an apparent Kd of 1,138 nM. Compared to the HTNV N protein-vRNA(1–39) complexes, vRNA(1–22)/vRNA(1675–1696) showed an 8.6-fold reduction in the apparent dissociation constant.

TABLE 3.

Apparent dissociation constants for HTNV N protein with various RNAs

| RNA | Dissociation constant (nM) |

|---|---|

| vRNA | 53 ± 8 |

| ORF RNA | 270 ± 32 |

| Minipan RNA | 72 ± 5 |

| Δ12 RNA | 94 ± 16 |

| Control RNA | 260 ± 15 |

| vRNA(1–39) | 132 ± 9 |

| vRNA(1–22) | 350 ± 0 |

| vRNA(1675–1696) | 417 ± 9 |

| cRNA(1–36) | 298 ± 53 |

| vRNA(1661–1696) | 624 ± 76 |

| cRNA(1658–1696) | 332 ± 34 |

| Random RNA | 367 ± 87 |

| vRNA(1–39)/vRNA(1661–1696) | 266 ± 143 |

| vRNA(1–22)/vRNA(1675–1696) | 1,138 ± 88 |

| cRNA(1–39)/cRNA(1658–1696) | 245 ± 35 |

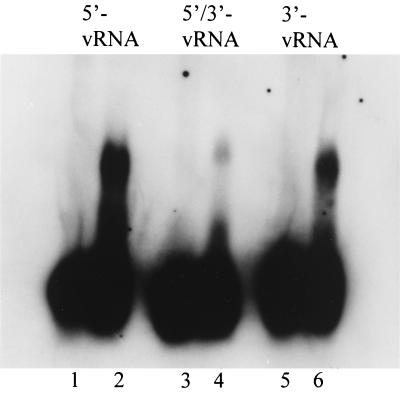

Gel electrophoretic mobility analysis of synthetic vRNA oligoribonucleotide mimics and HTNV N protein.

The interaction between the HTNV N protein and the vRNA was also investigated with a GEMSA. Protein-RNA complex formation with the HTNV N protein was examined for three oligoribonucleotide substrates: the 5′ vRNA, a duplex of the 5′ and 3′ ends, and the 3′ vRNA (Table 1). The weakest protein-RNA complex was that comprising the N protein and the duplex substrate (Fig. 4, lane 3). The strongest interaction was noted with the 5′ vRNA substrate (Fig. 4, lane 2). The interaction of the 3′ vRNA was weaker than that of the 5′ vRNA substrate. These results are in agreement with those observed in the filter-binding assay and suggest that the major determinant of binding of the S-segment vRNA by the N protein lies in the 5′ end and is not a predominantly double-stranded RNA.

FIG. 4.

GEMSA of the HTNV N protein with 5′- and 3′-end vRNAs. HTNV N protein was incubated with 5′-, 32P-labeled S-segment vRNA oligoribonucleotide derivatives: 5′-end vRNA 1–39 (lane 2), a duplex RNA composed of 5′-end vRNA(1–39) and 3′-end vRNA(1661–1696) (lane 4), and 3′-end vRNA(1661–1696) (lane 6). The reaction products were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel after an incubation period of 20 min, and the protein-RNA complexes were separated from free RNA by gel electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Odd-numbered lanes show results of reactions run without N protein.

DISCUSSION

The biological role of the hantavirus N protein in the virus life cycle requires differential interactions with the three types of viral RNAs, the vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA. During the assembly of the virion, the vRNA is packaged preferentially, which suggests an operational mechanism for selection of the vRNA that may require the N protein. The N protein will encapsidate vRNA and cRNA, but not mRNA, in a virus-infected cell. In vitro, the HTNV N protein shows a preference for vRNA compared to ORF vRNA. These observations argue strongly for the presence of a unique signal for encapsidation and assembly. To determine whether the vRNA contained a signal for encapsidation within the vRNA, we used UV cross-linking, filter binding, and GEMSA to probe the interaction of the HTNV N protein with a panel of vRNA and cRNA substrates. The binding data generated herein suggest that a specific binding interaction takes place in the 5′ end of the S-segment vRNA.

Several deletions were constructed in the HTNV S segment to determine whether an encapsidation signal was present in the vRNA. Filter-binding and UV cross-linking experiments suggested a signal in the untranslated regions of the vRNA. To further confirm the relative contribution of sequences or the effect of the absence of sequences of the minipan, Δ12, and ORF vRNAs in binding the N protein, we investigated the ability of unlabeled in vitro transcribed Δ12 RNA, minipan RNA, and ORF RNA to compete with 32P-labeled HTNV vRNA in a filter-binding assay. Neither minipan RNA nor ORF RNA was an effective competitor of the HTNV N protein-vRNA interaction (Table 2). However, Δ12 RNA moderately reduced binding by 60%, suggesting that the nucleic acid binding site was located in the 5′-terminal sequences of the vRNA. To determine whether the 5′ end of the vRNA was sufficient for the interaction, a panel of oligoribonucleotides that represent viral terminal sequences were synthesized and tested for their ability to bind the N protein by filter binding and GEMSA. The greatest binding was observed with the 5′-end vRNA(1–39), with an apparent Kd of 132 nM, while the other viral RNAs showed a twofold or greater reduction in binding affinity. As far as we are aware, the dissociation constants have not been reported for many other virus encapsidation complexes. Recently, a Kd of 110 (SEM, ±50) was reported for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid (NC)-SL2 complex (1). The NC-SL2 interaction was proposed to play a direct role in specific recognition and packaging of the full-length retroviral RNA genome. We suggest that the region spanning nucleotides 1 to 39 in the 5′ end of the vRNA contains the major cis-acting element for specific recognition and encapsidation. Additional sequences downstream of this region may increase binding activity, but only slightly, i.e., twofold. Only one other study (2) has attempted to examine the substrate preference of a hantavirus N protein. In contrast to our findings for the HTNV N, Gott et al. (2) reported that the Puumala virus N protein had a twofold-higher affinity for double-stranded viral RNA over single-stranded viral RNA. Unfortunately, it is difficult to directly compare the substrates used in our studies with those reported for Puumala virus N protein.

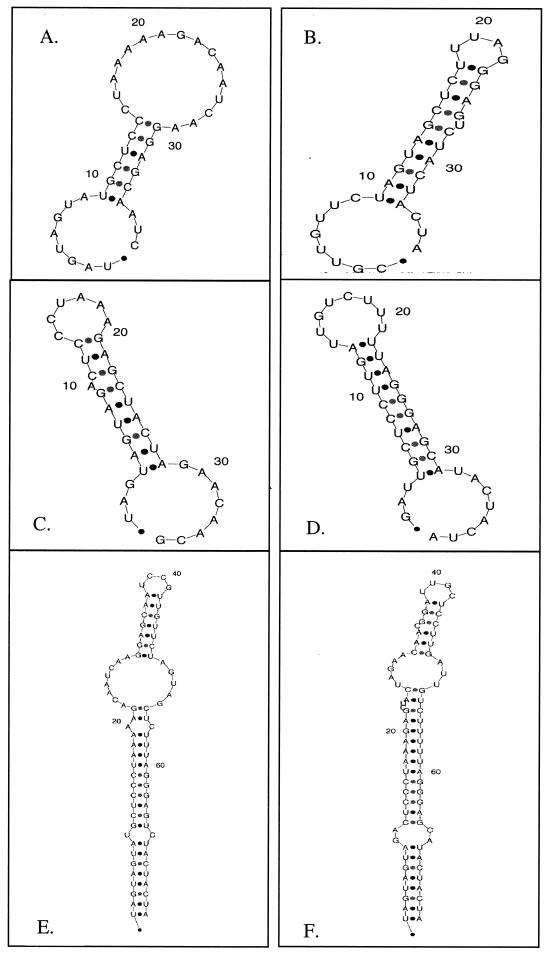

RNA sequences can form complex secondary and tertiary structures, and we were interested in the possible secondary structures in the putative encapsidation signal. For these reasons, we used mfold-generated algorithms to predict secondary structures of the HTNV viral RNA sequences (14). The sequence of the vRNA modeled by mfold was from position +1 to 39 of the HTNV S segment (Fig. 5A). The vRNA structure folded into stem loop structure. Inspection of this structure shows one double-helical tract (stem) that gives rise to a large loop of unpaired nucleotides (Fig. 5A). Additional secondary structure modeling of the untranslated regions of this segment (1 to 60, 1 to 130, and 1 to 370 nt) preserves the presence of the large single-stranded loop (C. B. Jonsson, data not shown). Models were also generated for the 3′ end of the vRNA(1661–1696) (Fig. 5B) and the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cRNA (Fig. 5C and D). In contrast to the large single-stranded region predicted for the 5′-end vRNA stem-loop (SL) structure, these RNAs showed large, stable SLs with a greater amount of double-stranded RNA and greater values of ΔG (data not shown). Modeling of the duplex hybrids of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the vRNA (Fig. 5E) examined by GEMSA as well as the cRNA end (Fig. 5F) also revealed a very stable SL, which was mainly double stranded. Previous work in our laboratory has demonstrated that the HTNV N protein when complexed with vRNA is readily digested with RNase V1, a double-stranded nuclease, but not RNase T1, a single-stranded nuclease (13). Further, the Δ12 vRNA, which is predicted by mfold to be unable to form a panhandle or the SL structure in the 5′ end (data not shown), competed effectively with vRNA. This suggests that the N protein may interact with single-stranded regions in the SL or, alternatively, a more complex structure which also has single-stranded regions. We propose a two-step model for encapsidation of the viral genome (vRNA) and antigenome (cRNA) that entails both specific and nonspecific interactions with the N protein. We hypothesize that initially, a specific interaction occurs between the N protein and the sequences in the single-stranded region of the predicted SL structure (Fig. 5A) in the 5′ end of the nascent vRNA. This is similar to what has been observed and proposed for vesicular stomatitis virus (7) and rabies virus (4). For the second part of the model, we suggest that the initial binding may be followed by N protein-N protein interactions, which could drive the nonspecific binding of the remaining vRNA template.

FIG. 5.

Secondary structures of HTNV RNAs predicted using the mfold program. The parameters for running the mfold program (version 3.0) were as follows: linear structure of the sequence, 37°C folding temperature, no limit for the maximum distance between nucleotide pairs, and a batch processing option. (A) vRNA(1–39); (B) vRNA(1661–1669); (C) cRNA(1–36); (D) cRNA(1658–1669); (E) vRNA(1–39) complexed with vRNA(1661–1669); (F) cRNA(1–36) complexed with cRNA(1658–1696).

In viruses, secondary structures such as consecutive hairpins and internal loops serve as assembly sites for numerous biological activities associated with the life cycles (9). We have shown that the 5′ end of the S-segment vRNA can fold into a unique secondary structure by modeling. Modeling of the HTNV M segment showed smaller SLs in the same region, although modeling of the HTNV L-segment 5′ end predicted the region to be single stranded (data not shown). At a minimum, this secondary structure prediction, along with deletion mapping of the RNA, suggests sequence and/or structural motifs in the vRNA that allow specific interaction with the N protein. Future experiments will focus on how the HTNV S-segment RNA folds and on the nucleotide contacts that are critical for protein-RNA interactions. In addition, it will be important to define the location of encapsidation signals for the other two genomic segments, M and L.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Connie Schmaljohn for plasmids and RNAs used in these studies.

This research was supported by NIH grant 1RO3AI41114 to C.B.J.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amarasinghe G K, De-Guzman R N, Tuner R B, Chancellor K J, Wu Z R, Summers M F. NMR structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to step-loop SL2 of the psi-RNA packaging signal. Implications for genome recognition. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:491–511. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gott P, Stohwasser R, Schnitzler P, Darai G, Bautz E K F. RNA binding of recombinant nucleocapsid proteins of hantaviruses. Virology. 1993;194:332–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacker D, Raju R, Kolakofsky D. La Crosse nucleocapsid protein controls its own synthesis in mosquito cells by encapsidating its mRNA. J Virol. 1989;63:5166–5174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5166-5174.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kouznetzoff A, Buckle M, Tordo N. Identification of a region of the rabies virus N protein involved in direct binding to the viral RNA. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1005–1013. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H W. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. In: Elliot R M, editor. The Bunyaviridae. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J S. Clinical feature of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Korea. Kidney Int. 1991;40:S88–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyer S A, Smallwood-Kentro S, Haddad A, Prevec L. Assembly and transcription of synthetic vesicular stomatitis virus nucleocapsids. J Virol. 1991;65:2170–2178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2170-2178.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raju R, Kolakofsky D. The ends of La Crosse virus genome and antigenome RNAs with nucleocapsids are base paired. J Virol. 1989;63:122–128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.122-128.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlesinger S, Makino S, Linial M L. cis-acting genomic elements and trans-acting proteins involved in the assembly of RNA viruses. Semin Virol. 1994;5:39–49. doi: 10.1006/smvy.1994.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmaljohn C, Hjelle B. Hantaviruses: a global disease problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:95–104. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmaljohn C S. Bunyaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1447–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmaljohn C S. Molecular biology of hantaviruses. In: Elliot R M, editor. The Bunyaviridae. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1996. p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Severson W, Partin L, Schmaljohn C S, Jonsson C B. Characterization of the Hantaan N protein-ribonucleic acid interaction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33732–33739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zucker M, Mathews D H, Turner D H. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: a practical guide. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]