Abstract

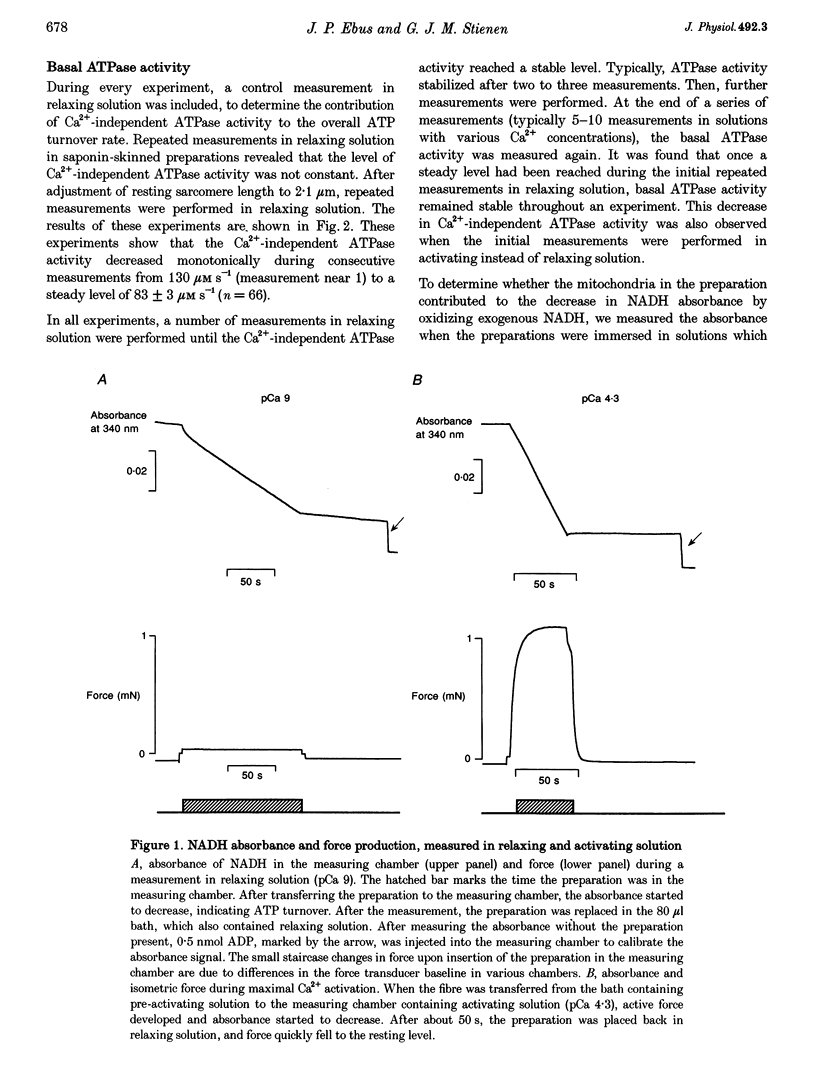

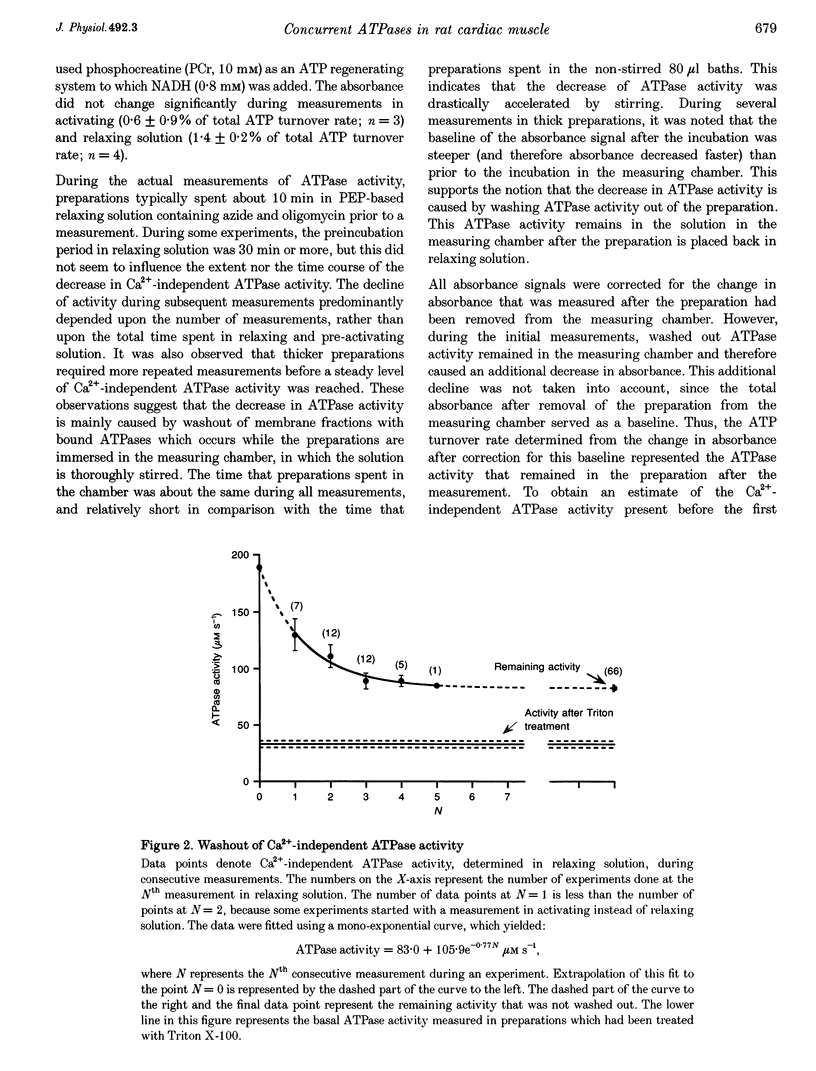

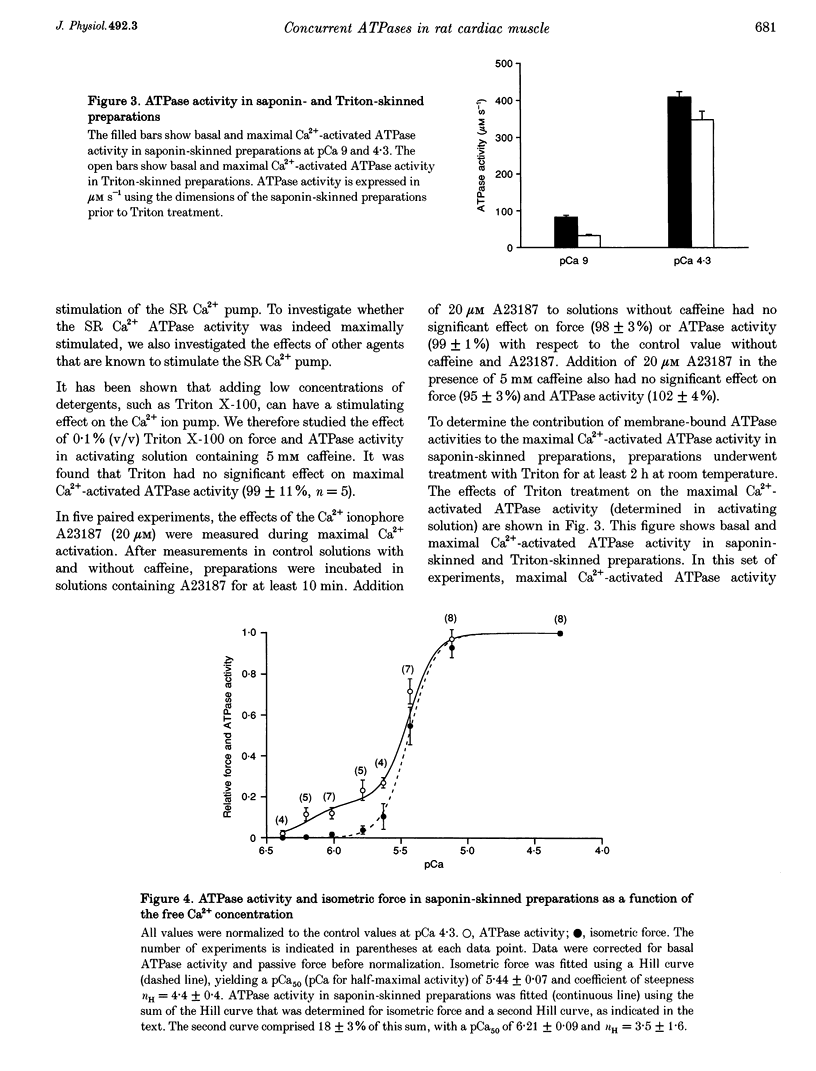

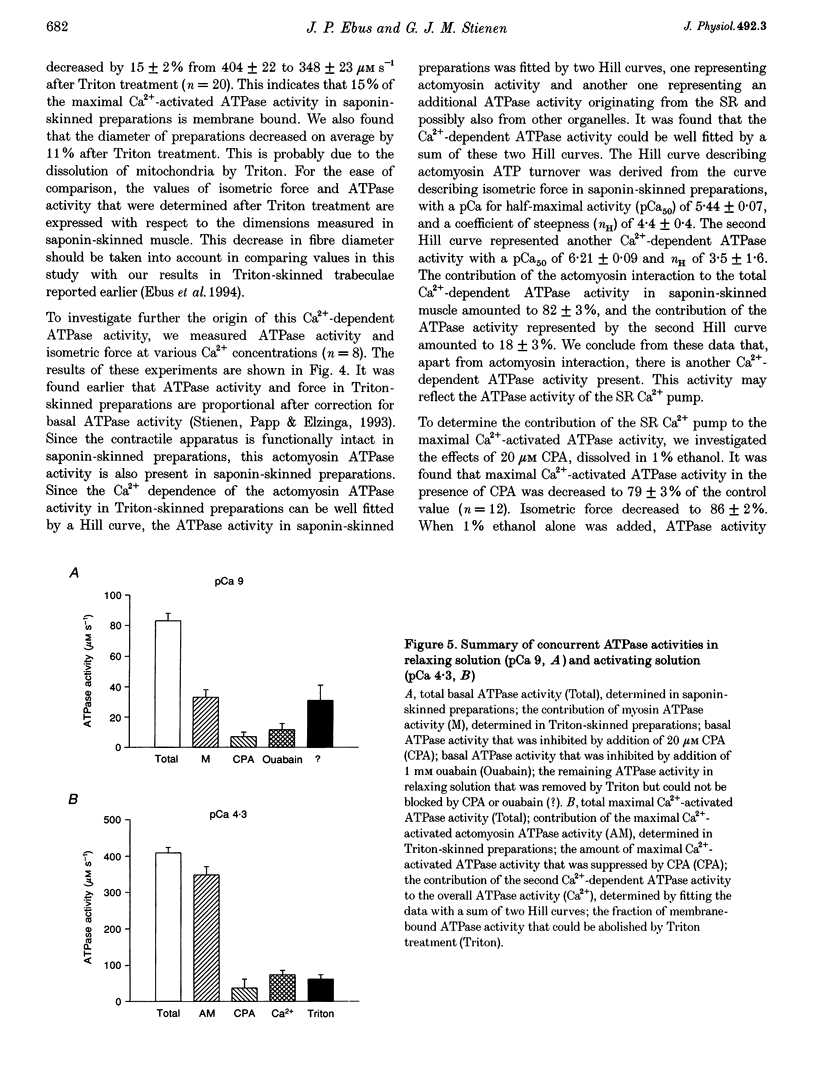

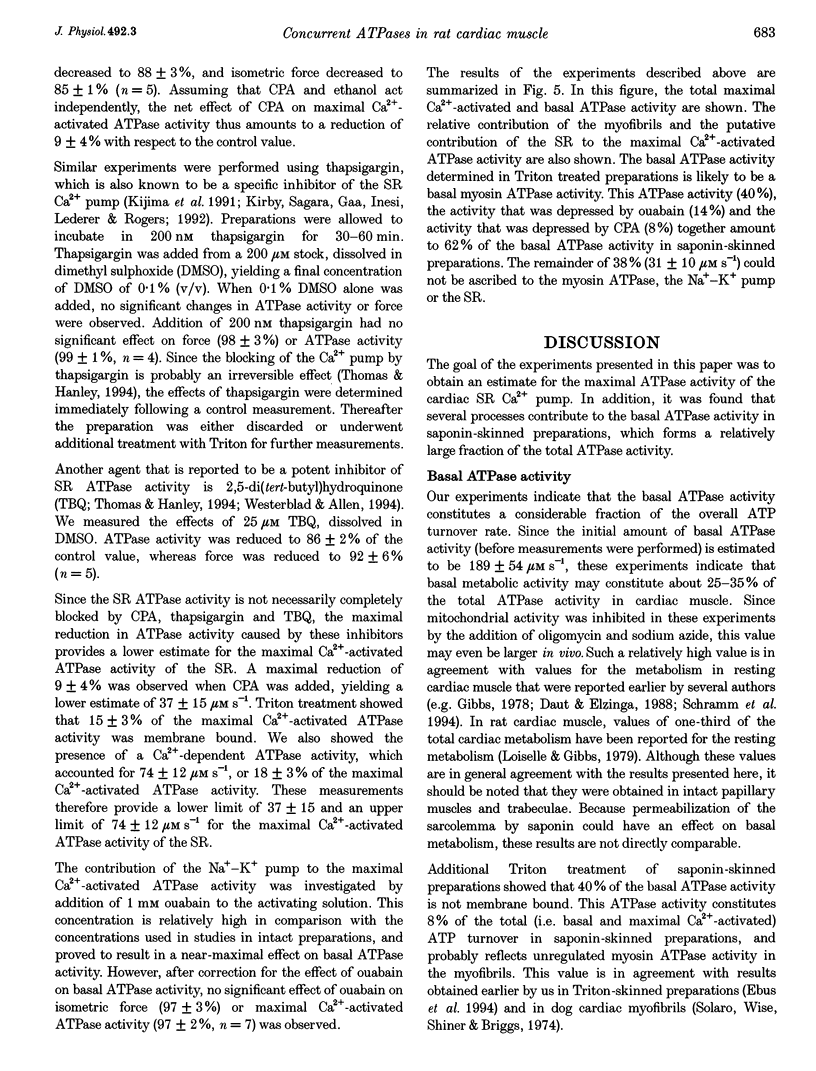

1. To determine the rate of ATP turnover by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ pump in cardiac muscle, and to assess the contributions of other ATPase activities to the overall ATP turnover rate, ATPase activity and isometric force production were studied in saponin-skinned trabeculae from rat. ATP hydrolysis was enzymatically coupled to the oxidation of NADH; the concentration of NADH was monitored photometrically. All measurements were performed at 20 +/- 1 degrees C and pH 7.0. Resting sarcomere length was adjusted to 2.1 microns. All solutions contained 5 mM caffeine to ensure continuous release of Ca2+ from the SR. 2. The Ca(2+)-independent ATPase activity, determined in relaxing solution (pCa 9), amounted to 130 +/- 13 microM s-1 (mean +/- S.E.M., n = 7) at the beginning of an experiment. During subsequent measurements in relaxing solution, a decrease in ATPase activity was observed, indicative of loss of membrane-bound ATPase activity. The steady-state Ca(2+)-independent (basal) ATPase activity was 83 +/- 5 microM s-1 (n = 66). 3. Treatment of saponin-skinned preparations with Triton X-100 abolished 50 microM s-1 (60%) of the basal ATPase activity. Addition of ouabain (1 mM) suppressed 14 +/- 5% of the basal activity, whereas 8 +/- 3% was suppressed by 20 microM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA). It is argued that 31 microM s-1 of the basal ATPase activity may be associated with MgATPase from the transverse tubular system. 4. The maximal Ca(2+)-activated ATPase activity, i.e. the total ATPase activity (determined in activating solution, pCa 4.3) corrected for basal ATPase activity, was found to be 409 +/- 15 microM s-1 (n = 66). Experiments with CPA indicated that at least 9 +/- 6% of the maximal Ca(2+)-activated ATPase activity originates from the sarcoplasmic Ca2+ pump. These experiments indicate that the rate of ATP consumption by the SR Ca2+ transporting ATPase amounts to at least 37 microM s-1. 5. Treatment of preparations with Triton X-100 abolished 15 +/- 3% of the maximal Ca(2+)-activated ATPase activity, indicating that 15 +/- 3% of the maximal Ca(2+)-activated ATPase activity is membrane bound. 6. Variation of free [Ca2+] indicated that apart from the actomyosin ATPase activity a second Ca(2+)-dependent ATPase activity contributed to the overall ATP turnover rate. This activity was half-maximal at pCa 6.21, and probably reflects the SR Ca2+ transporting ATPase. It constituted 18 +/- 3% of the Ca(2+)-dependent ATPase activity, yielding an upper limit for the SR Ca2+ transporting ATPase activity of 74 microM s-1.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Westerblad H. The effects of caffeine on intracellular calcium, force and the rate of relaxation of mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1995 Sep 1;487(Pt 2):331–342. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balke C. W., Egan T. M., Wier W. G. Processes that remove calcium from the cytoplasm during excitation-contraction coupling in intact rat heart cells. J Physiol. 1994 Feb 1;474(3):447–462. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry W. H., Bridge J. H. Intracellular calcium homeostasis in cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 1993 Jun;87(6):1806–1815. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudet S., Shaoulian R., Bers D. M. Effects of thapsigargin and cyclopiazonic acid on twitch force and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content of rabbit ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 1993 Nov;73(5):813–819. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler T. J., Gable K. S., Keffer J. M. Characterization of the membrane bound Mg2+-ATPase of rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983 Oct 12;734(2):221–234. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(83)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler T. J., Wang T., Gable K., Lee S. Comparison of the rat microsomal Mg-ATPase of various tissues. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985 Dec;243(2):644–654. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J., Elzinga G. Heat production of quiescent ventricular trabeculae isolated from guinea-pig heart. J Physiol. 1988 Apr;398:259–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebus J. P., Stienen G. J., Elzinga G. Influence of phosphate and pH on myofibrillar ATPase activity and force in skinned cardiac trabeculae from rat. J Physiol. 1994 May 1;476(3):501–516. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M., Iino M. Specific perforation of muscle cell membranes with preserved SR functions by saponin treatment. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1980 Mar;1(1):89–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00711927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Calculator programs for computing the composition of the solutions containing multiple metals and ligands used for experiments in skinned muscle cells. J Physiol (Paris) 1979;75(5):463–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Contractions induced by a calcium-triggered release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of single skinned cardiac cells. J Physiol. 1975 Aug;249(3):469–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Myoplasmic free calcium concentration reached during the twitch of an intact isolated cardiac cell and during calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned cardiac cell from the adult rat or rabbit ventricle. J Gen Physiol. 1981 Nov;78(5):457–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glyn H., Sleep J. Dependence of adenosine triphosphatase activity of rabbit psoas muscle fibres and myofibrils on substrate concentration. J Physiol. 1985 Aug;365:259–276. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove-Madsen L., Bers D. M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake and thapsigargin sensitivity in permeabilized rabbit and rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1993 Nov;73(5):820–828. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inesi G. Mechanism of calcium transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 1985;47:573–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.47.030185.003041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inesi G., de Meis L. Regulation of steady state filling in sarcoplasmic reticulum. Roles of back-inhibition, leakage, and slippage of the calcium pump. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 5;264(10):5929–5936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijima Y., Ogunbunmi E., Fleischer S. Drug action of thapsigargin on the Ca2+ pump protein of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1991 Dec 5;266(34):22912–22918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korge P., Campbell K. B. Local ATP regeneration is important for sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump function. Am J Physiol. 1994 Aug;267(2 Pt 1):C357–C366. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.2.C357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurebayashi N., Ogawa Y. Discrimination of Ca(2+)-ATPase activity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum from actomyosin-type ATPase activity of myofibrils in skinned mammalian skeletal muscle fibres: distinct effects of cyclopiazonic acid on the two ATPase activities. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1991 Aug;12(4):355–365. doi: 10.1007/BF01738590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. J., Elder H. Y., Smith G. L. Ultrastructural and X-ray microanalytical studies of EGTA- and detergent-treated heart muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1985 Oct;6(5):525–540. doi: 10.1007/BF00711913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton M. P., Sabbadini R. A., Norton K. C., Dahms A. S. Studies on the transverse tubule membrane Mg-ATPase. Lectin-induced alterations of kinetic behavior. J Biol Chem. 1986 Sep 15;261(26):12244–12251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri L. A., Hasenfuss G., Ittleman F., Blanchard E. M., Alpert N. R. Protection of human left ventricular myocardium from cutting injury with 2,3-butanedione monoxime. Circ Res. 1989 Nov;65(5):1441–1449. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mészáros L. G., Ikemoto N. Ruthenium red and caffeine affect the Ca2+-ATPase of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985 Mar 29;127(3):836–842. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(85)80019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm M., Klieber H. G., Daut J. The energy expenditure of actomyosin-ATPase, Ca(2+)-ATPase and Na+,K(+)-ATPase in guinea-pig cardiac ventricular muscle. J Physiol. 1994 Dec 15;481(Pt 3):647–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigekawa M., Finegan J. A., Katz A. M. Calcium transport ATPase of canine cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. A comparison with that of rabbit fast skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1976 Nov 25;251(22):6894–6900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro R. J., Wise R. M., Shiner J. S., Briggs F. N. Calcium requirements for cardiac myofibrillar activation. Circ Res. 1974 Apr;34(4):525–530. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen G. J., Papp Z., Elzinga G. Calcium modulates the influence of length changes on the myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase activity in rat skinned cardiac trabeculae. Pflugers Arch. 1993 Nov;425(3-4):199–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00374167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen G. J., Roosemalen M. C., Wilson M. G., Elzinga G. Depression of force by phosphate in skinned skeletal muscle fibers of the frog. Am J Physiol. 1990 Aug;259(2 Pt 1):C349–C357. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.2.C349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen G. J., Zaremba R., Elzinga G. ATP utilization for calcium uptake and force production in skinned muscle fibres of Xenopus laevis. J Physiol. 1995 Jan 1;482(Pt 1):109–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Hanley M. R. Pharmacological tools for perturbing intracellular calcium storage. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;40:65–89. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H., Allen D. G. The role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in relaxation of mouse muscle; effects of 2,5-di(tert-butyl)-1,4-benzohydroquinone. J Physiol. 1994 Jan 15;474(2):291–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]