Abstract

Extreme heat events have become more common and more severe during summer than ever before as a result of the warming climate in Australia. The impact of urban morphology and green coverage on outdoor thermal comfort has been the subject of extensive research, however, their link to suburban developments of different historic periods is still underexplored. This paper investigates and compares the outdoor thermal performance of ten suburban areas constructed since the late nineteenth century in Greater Adelaide, which were built to different planning ideals and concepts of their time. Microclimate models of two precedents for five development eras were constructed in ENVI-met, validated with site data related to a recent heatwave event in 2023, and then used to facilitate further investigation of the impact of development patterns on outdoor thermal comfort. This study examines how these urban patterns perform in scenarios of varying development intensity and greenery ratio. In these case studies, the distance between buildings, streets’ spatial ratio and green coverage has a significant impact on the thermal environment. The results underline the impact of solar exposure on outdoor thermal performance even in lower-density suburban areas. Some of the outcomes of the study are counter-intuitive to conventional assumptions about urban design typologies. In this comparison, for example, one of the “green” model garden city developments did not perform as well as denser 19th-century suburbs. The results can support better decision-making for future urban planning in Australia and other regions with similar climate conditions. The study shows that real performance does not always align with stated green ambitions and, urban design should consider and evaluate heat mitigation through evidence-based testing to achieve real green development.

Keywords: Outdoor microclimate, Historical housing, Urban development, ENVI-met, Planning theory

Subject terms: Environmental social sciences, Climate-change adaptation, Energy and society, Environmental impact, Sustainability

Introduction

Australia has long taken pride in its “home owning democracy”1, where 66% of households own their homes2. Despite the advocacy for compact cities as a means of achieving sustainable urban development, the predominant urbanization pattern in Australia’s history remains suburban3. Low-density dispersed housing, epitomized by the ‘quarter acre block,’ has been favored as a manifestation of the Australian Dream4. Australia’s urban development rapidly expanded in the late nineteenth century5,6, adhering to the prevalent planning perspective of creating a suburban nation7. Australia still comprises suburban residential areas planned from different historical periods since the nineteenth century, reflecting local historical and cultural features.

Over the past century, various urban development paradigms have promised to enhance residents’ lives in terms of convenience and environmental friendliness8. Yet, the practical outcomes of popular urban design ideals may not always align with expectations. For instance, the term “Garden City” is significantly more popular than “Compact City” in online searches, with an average Google Trends search index of 47.44 and 0.44, respectively9. Low-density new town developments like the “Garden City” model have been favored for their high accessibility to green spaces10,11 and romanticized in books criticizing overcrowded urban environments12,13. However, actual environmental impact may not be as “green” as designers wished in practice. Urban sprawl, characterized by a low-density pattern, has been criticized for resulting in environmental problems14, including car-dependent neighborhoods15, loss of ecologically sensitive habitats16, and high average carbon emissions among residents17.

Urban morphology serves as a tangible built expression of these urban planning and design concepts18,19. Over time, even as aspects of urban management and systems change, the physical entities of these concepts often endure into subsequent eras20. Urban morphology encompasses the fundamental physical elements and characteristics that constitute and define the city, including urban patterns (building layout and street network), development density (building mass and spaces), vegetation, surface materials and etc.21,22. Among these elements, urban patterns and surface materials tend to undergo minimal alterations during urban block renewal, while density and vegetation can gradually evolve with the replacement of individual buildings and the growth of plant life. Therefore, this study will conduct a series of simulations based on current conditions and extreme scenarios of building density and plants to explore how the relatively immutable elements of the original urban planning (specifically, urban patterns and surface materials) affect the outdoor thermal environment of urban blocks.

With a warming climate, the outdoor comfort levels of different types of urban development have become increasingly important and relevant to academic research23. Individuals in over-heated urban areas face a 6% higher risk of mortality or illness compared to those in cooler regions24. Given the unstoppable trend of global warming25 and Australia’s ongoing experiences with heatwaves23, extreme heat events in Australia are expected to become more frequent, with the length of heatwaves potentially extending up to a month26. Australia’s vulnerability to heatwaves is linked to geographical and climatic factors, as well as space and time dimensions etc.27. Between 2000 and 2018, at least 354 deaths in Australia were attributed to heatwaves, as recorded by coroners28. During heatwaves, there has been a significant and sustained increase in overall mortality in Australia’s three largest cities, with vulnerable populations, such as elderly women, being particularly affected29. Nowadays, South Australia is experiencing an average of 1 °C warmer climates than in the 1960s, with nine of the ten hottest years on record in South Australia documented since 200530. Research by Nishant et al.31 also identified Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, as one of the major Australian cities most susceptible to future heatwaves, with projections indicating a 56-fold increase in heatwave exposure by the end of the twenty-first century. Therefore, using Adelaide as a case study to examine the thermal comfort performance of residential neighborhoods under extreme heatwave conditions is fundamentally about understanding how Australians can adapt to heat when and where it is most needed—during heatwaves and in the vicinity of their homes32. This research is highly valuable for developing suburban urban planning strategies that are better prepared to address future heatwave impacts in Australia.

Any popular idea for ideal urban development must be tested over time and through practical application, and historical neighborhoods provide excellent material for such evaluation33. While research on indoor thermal comfort in historical housing zones by multiple case studies is relatively abundant34,35,36, studies on outdoor thermal comfort in historical neighborhoods still exhibit significant limitations. First, in many existing studies, historical neighborhoods serve merely as a contextual background rather than being the focus of comparative analysis based on their design and construction periods. For example, Rosso et al.37, Huang et al.38, and Hoffman, Shandas, and Pendleton39 all focus on specific neighborhoods from a single historical period or a particular group of periods, while Qian et al.40, Sözen and Koçlar Oral41, and Yıldırım42 provide only vague descriptions regarding time. Second, studies comparing typical housing zones built during different historical periods are usually limited to only a few time points, generally 2–343,44,45,46, resulting in low granularity along the longitudinal time dimension. Furthermore, research focused on the meso-level scale of urban neighborhoods often includes only a small number of case study areas (usually 1–2, at most 3)43,44,45,38. There is a lack of systematic, high-temporal-resolution, multi-case research comparing the outdoor thermal performance of residential areas developed across various historical periods. Moreover, existing discussions are typically limited to evaluating thermal performance and optimizing specific building and urban design parameters. There is a lack of a broader perspective that integrates different historical periods’ urban planning theories and strategies to explore the outdoor thermal comfort of neighborhoods developed under those particular development models.

To address these gaps, this study focuses on ten typical cases from five historical periods in Adelaide since the nineteenth century. Using outdoor thermal environment simulations across five sets of scenarios by ENVI-met, the study aims to evaluate and discuss the advantages and potential long-term effects of planning methods from different historical periods in terms of thermal comfort performance. By exploring and comparing the outdoor thermal performance of these different urban development approaches, the outcomes may be counter-intuitive to conventional assumptions about ideal urban design typologies. Based on these comparative studies, planners can gain insights and draw practical lessons for future suburban housing developments. The study begins with simulations and validations of the outdoor thermal environment based on the current conditions of the neighborhoods. Previous research has identified urban patterns and building density at the neighborhood scale as crucial factors influencing overall thermal performance47. Additionally, green planning, involving vegetation coverage, has been recognized as a potent physical strategy for enhancing microclimates48,49,50. Therefore, four sets of additional extreme scenarios with different adjusted building densities and vegetations were designed, to find out the impact of different typologies of historical urban layout (patterns and surfaces) on the outdoor thermal environment.

The objectives of this study corresponding to the above-raised issues are:

First, the study explores the thermal performance of ten historical neighborhoods under current conditions using Air Temperature (Air T), Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT), and Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) as indicators.

Second, the study examines how relatively immutable elements of original urban planning (such as urban patterns and surface materials from different historical periods) affect outdoor thermal performance when the influences of building density and vegetation are minimized.

Third, the study assesses the impact of more easily modifiable elements (density and vegetation) on outdoor thermal performance, noting their varying effects.

Furthermore, the study discusses how these factors relate to the planning approaches prevalent during various historical periods and their impact on the thermal environment, as well as provides advice for future developments.

Overall, this study is innovative in its approach of comparing and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of five suburban residential development models influenced by various planning concepts through their performance in outdoor thermal environments for 10 Adelaide housing case study areas. By examining existing scenarios and four extreme scenarios with varying development intensities and levels of greenery, the study explores the limits of the possible impacts caused by these historically popular planning concepts. It enhances our understanding of the outdoor thermal performance of typical low-density suburban neighborhood developments in Australia since the late nineteenth century and analyzes the relative importance of different urban morphology elements within various urban planning theoretical frameworks.

Research methods

The comparison of thermal performance of urban development patterns is facilitated by analyzing field data, modelling, and simulation of 10 case study sites developed in Greater Adelaide since the 1900s.

Case study site

Greater Adelaide is chosen as a suitable location for these case studies not only because it and the rest of South Australia face representative significant future challenges related to thermal environments30,31, but also due to its continual development since the late nineteenth century and the existence of areas developed across various historical periods51,52. The city of Adelaide and today’s North Adelaide was planned in the 1830s by Colonel William Light, the inaugural surveyor general of the British Province of South Australia53. Today’s Greater Adelaide has grown far beyond that initial masterplan and comprises numerous suburbs, some of which were previously separate country towns or villages52,54, . During the early stages of Adelaide’s development, city planning was influenced by classical Victorian planning ideas of a regular grid pattern as well as the garden city theory55,56, resulting in a structured checkerboard layout surrounded by a green belt52. In the 1920s, a housing zone model was introduced in Colonel Light Garden based on the garden city theory, which was further imitated and replicated across other parts of South Australia57, (Mcgreevy, 2017). After World War II, with rapid population growth, numerous residential areas were planned through state initiatives near workplaces, often factories, that were influenced by the Neighborhood Unit theory58,51,52. By the 1960s, professional property developers gradually took over real estate development in Adelaide, influenced by new ideologies such as New Urbanism58,52.

For this study, ten suburban housing developments in Greater Adelaide were selected (Fig. 1), representing distinct historical periods (Fig. 2). These developments are situated in Prospect, Norwood, Colonel Light Gardens, Toorak Gardens, Elizabeth, Tonsley, West Lakes, Semaphore Park, Lightsview, and Mawson Lakes. They were chosen to represent suburban residential areas from different historical periods within Greater Adelaide, reflecting the specific urban planning concepts of their times. The selection is based on a local history book published by the Adelaide City Council51, a book on urban planning history written by a local Adelaide urban planner and later city council CEO52, a paper on the evolution of suburban design in Adelaide by Alan Hutchings and Christine Garnaut, the founding Director of the SA Architecture Museum (2007), as well as various local sources about the selected case study neighborhoods59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67.

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of 10 case study sites in Greater Adelaide. (Base map exported by Google Maps, further edited by Yue Liu. Map data: Imagery ©2024 Landsat / Copernicus, Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Imagery ©2024 Terrameric, Map data ©2024 Google.)

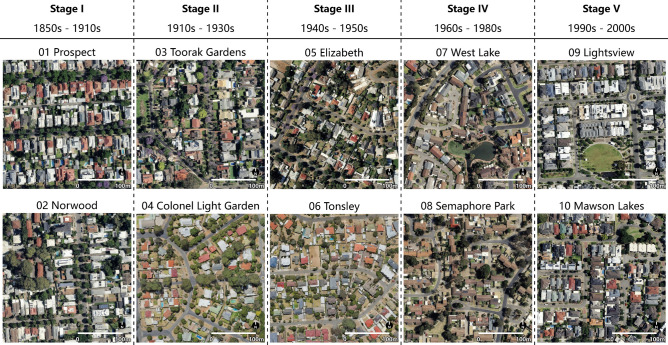

Fig. 2.

Case study sites development pattern and their historical origins. (Base maps exported by Google Maps, further edited by Yue Liu. Map data: Imagery ©2024 Vexcel Imaging Us, Inc., Imagery ©2024 Airbus, CNES / Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Map data ©2024 Google.)

The first and second case study areas, located in Prospect61 and Norwood65, were planned in the nineteenth century with a classical rectilinear repetitive layout. Colonel Light Gardens63,57 and Toorak Gardens62 represent Garden City developments from the 1920s with radial streets. Elizabeth reflects a housing development from the early post-war period52, and the area in Tonsley was developed from the 1950s64,67, which have more curvilinear street patterns and which are residential areas originally planned for manufacturing workers. The case study areas in West Lakes60 and Semaphore Park59 emerged in the 1970s and 1980s and have even more organic, curvilinear street layouts. Lightsview66 and Mawson Lakes58 are more recent developments from the 2000s onwards, which represent a return to the more regular, rectilinear layout patterns of the classical Victorian layouts of Prospect and Norwood, but with increased building heights. Despite all being suburban developments, these areas showcase diverse approaches of planning in terms of layout, building density and greening strategy.

Research framework

Figure 3 illustrates the simulation validation process of this study, starting with the verification and calibration of the simulation model based on field-measured data. Five groups of scenarios were subsequently simulated in ENVI-met: The “existing buildings/existing trees” scenario represents the current condition, while the other four scenarios test different tree coverage and building densities. The scenarios that maintain “existing buildings” with “no trees” and “maximum trees” conditions enable comparisons with current conditions to determine the maximum potential impact of tree growth and planting when other construction parameters remain unchanged. Two additional “added density” scenarios involve increasing the height of existing buildings to raise the building density to 0.55 (the current maximum development intensity), allowing for paired comparisons with the existing buildings scenarios to explore the patterns and limits of the effects of building density. Air Temperature (Air T), Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT), and Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) were used as indicators for evaluating thermal environment. These indicators were then analyzed based on their absolute values and relative rankings to compare the outdoor thermal performance of the case study areas.

Fig. 3.

Research flow chart.

Experimental design

To explore the impact of planning approaches from different historical periods on outdoor thermal comfort, the urban pattern left by each historical period is considered a fixed parameter. Two factors of tree coverage and building density are subject to a series of adjustments. Five sets of experimental scenarios were designed, each comprising 10 cases, resulting in a total of 50 simulated scenarios.

A set of scenarios are employed to achieve uniform density involves increasing the number of floors in some existing buildings to achieve a Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of 0.55 (the highest existing FAR among the case studies). The building heights are distributed as evenly as possible, with the majority at 1 to 3 floors and only a few of up to 4 floors (the current maximum). The objective of these two groups with density adjustment is to simulate the most intensive scenarios of potential urban renewal without altering the urban pattern, thus observing the changes brought about by variations in building density.

The simulation and analysis of existing tree conditions are important as well as potential further greening strategies for each site. Three sets of scenarios are developed to address existing trees, no trees, and maximum possible tree coverage. The tree coverage explored in this study does not include variabilities in tree species which can be a subject for future research on an adjusted scale. An extreme scenario of “no trees” was established to explore which historical residential areas are impacted by their spatial layout and configurations independent of greenery and also to investigate which urban patterns are more dependent on trees to mitigate high temperatures. Maximum tree scenarios are estimated by the available open space for greening in each development pattern. Such spatial availability for greening is one of the most significant differences between these development patterns in Adelaide and is explored further in the discussion.

Cross-comparisons among the five scenarios help to isolate the effects of tree growth and building height changes, providing insights into how urban layouts affect the outdoor thermal environment at the neighborhood scale. This approach also identifies neighborhood forms that are particularly sensitive to changes in tree coverage, as well as planning typologies that perform well under various conditions.

Data collection and processing

ENVI-met model construction

This study used the ENVI-met simulation software (V5.6) for the simulation of urban thermal environments. As a high-resolution Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model based on three-dimensional meshes, ENVI-met provides the capability for scenario development, simulation and comparison between scenarios68,69. Due to its high applicability in microclimate research across diverse urban regions, Envi-met has been widely utilized for to outdoor thermal comfort research70,71,72,68,73,74.

Data collection for validation

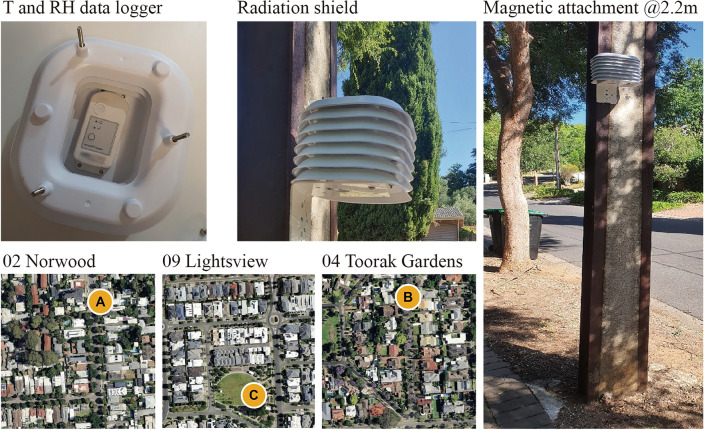

To validate the accuracy of the ENVI-met modelling and gather meteorological data required for model configuration, on-site measurements were taken in Norwood, Lightsview, and Toorak Garden on January 22nd and 23rd, 2023 under clear sky and calm weather conditions with wind speeds below 3 m/s. This represents a recent heatwave in Adelaide and, therefore, is chosen to validate the model targeting heat stress and summer thermal comfort31. The HOBO data loggers were calibrated by a recently certified KESTREL 5400 unit by placing them in a controlled environment—inside an insulated container—for a full day while logging data every 30 min (HOBO MX2301A response time is 17 min). The data recorded by all units are used to make a statistical model for converting all recorded values into a uniform set with the certified KESTREL unit as the reference.

The collected metric data encompassed air temperature and relative humidity every 30 min from 0:00 on January 22nd to 23:30 on January 23rd. Meteorological data, including air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed, were collected throughout the days, covering the entire 48-h period from January 22nd 0:00 to January 23rd 23:59. The equipment employed for on-site measurements consisted of HOBO MX2301A with water proof air temperature and relative humidity sensors and data resolution of 0.01 C° and 0.1%, and data accuracy of + /- 0.2C° and + /- 2.5% (Fig. 4). The sensors were affixed at a height of 2.2 m and capable of recording temperature and humidity data every half hour throughout the day. Before conducting the on-site measurements, the instruments were calibrated overnight in an air-tight container. Data variations are recorded and used to adjust on-site data.

Fig. 4.

Assembly of HOBO MX2301A sensors used for model validations in Norwood (A), Lightsview (B), and Toorak Garden (C) January 22–23, 2024.

Simulation setting

This study adopted the method of case study simulation analysis and conducts quantitative research on 10 representative housing zone cases built in five periods in Adelaide through the urban microclimate simulation software ENVI-met. Adelaide’s climate is Mediterranean with warm to hot dry summers and mild winters75,76. The study focuses on the summertime extreme heat (during heat waves) which can impact human comfort and well-being. The simulation time was therefore selected from 8 am to 8 pm on the date with the hottest average temperature records (13 Jan) in the EPW file provided by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology BoM77.

The accuracy of the models has been verified through empirical testing. The simulations utilize meteorological data sourced uniformly from the nearest official BoM weather station located at West Terrace (ngayirdapira)78. The data of typical EPW files are replaced by the collected weather data of 22–23 January 2024 to validate the models. To ensure controlled variables, the foundational information and simulation settings of the models were consistently configured for the Adelaide location (-34.93, 138.60), adhering to Australian Central Daylight Time (+ 9:30) and utilizing a simple force model. Specific simulation parameter settings are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial condition parameters for simulation of 10 case study areas.

| Condition | Data |

|---|---|

| Model area | |

| Main Model Area | 300 m × 300 m × 60 m |

| Grid Size in meter | X = 2 Y = 2 Z = 2 |

| Position | |

| Longitude (°) | 138.60 |

| Latitude (°) | − 34.93 |

| Start and duration of the model | |

| Date of simulation | 23/01 |

| Start time | 00:00 |

| Total simulation time (h) | 20 (include 7 h “Spin up” duration) |

| Initial meteorological conditions | |

| Initial temperature of atmosphere (℃) | 31.80℃ |

| Initial Relative humidity of atmosphere (%) | 34.00% |

| Wind speed measured at 10 m height (m/s) | 2 |

| Wind direction (deg)(0° = from North,180° = from South) | 90 |

The existing neighborhood model was built based on a Google Earth model. The trees were abstracted from the model, differing only in size and generic types. For the maximum density scenarios, the original urban pattern was maintained and the development intensity was increased to FAR = 0.55. The height of the buildings was modelled based on the Google Earth 3d data (most are 1–3 floors, only a few are 4 floors, reflecting the suburban setting). The comparative simulation without trees only deleted the existing trees from the models. For the maximum tree models, trees of the same size and type were added in the entire available areas (non-roads and buildings) in the model to make the tree cover rate as high as possible. In order to reduce the error in the boundary area in simulation, each direction around the model was finally expanded by 10 empty grids (20 m). The potential air temperature, mean radiant temperature and SVF were extracted from the ENVI-core simulation results, and PET (default average person, 1.75 m male average wear) were calculated by Bio-met.

Other design approach related parameters

Greening rate and road area ratio were calculated using the online program i-tree canopy79,80 and the building development density (building floor area / site area), building height as well as width between buildings was calculated by the 3D model captured from Google Earth. The results (shown in Table 2) were used for reference comparison analysis to discuss these planning and development models.

Table 2.

Indicators of planning approach of case study sites of historical origins.

| Project Names | SVF | Density (FAR) | Tree Cover Rate | Grass Cover Rate | Building Cover Rate | Water Rate | Road Density | Average Width between Buildings (m) | Average Building Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospect | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.00% | 3% | 30.87 | 3.28 |

| Norwood | 0.83 | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.28% | 8% | 27.55 | 3.89 |

| Toorak Gardens | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.84% | 4% | 36.61 | 4.20 |

| Colonel L Gardens | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.23% | 23% | 38.12 | 3.16 |

| Elizabeth | 0.82 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.00% | 7% | 37.90 | 3.00 |

| Tonsley | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.05% | 11% | 36.89 | 3.51 |

| West Lakes | 0.81 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 4.51% | 13% | 26.64 | 3.25 |

| Semaphore Park | 0.72 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.00% | 9% | 27.60 | 3.53 |

| Lightsview | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.00% | 19% | 25.20 | 4.74 |

| Mawson Lakes | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.00% | 11% | 24.28 | 3.96 |

Model validation

In this study, we conducted a thorough analysis comparing observed and ENVI-met-simulated air temperature and relative humidity data across three distinct sites in Lightsview, Norwood, and Toorak Gardens. The evaluation was grounded on five key metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Pearson correlation coefficient (r), Coefficient of Determination (R2), and p-value, to quantify and interpret the congruence and correlation between the observed and simulated meteorological data.

These indices are used to quantify the discrepancies between the experimental and simulated data. Considering the measured (m) and simulated (s) variables for each time step i for a total of n data samples, the quantitative indicators adopted in this study are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Statistical indices used for model validation.

| Index | Name | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| r | Pearson correlation coefficient | |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination | |

| d | Index of agreement | |

| RMSE | Root mean square error | |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) represents the average difference between actual and predicted values, providing an overall measure of discrepancy81. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) quantifies the spread of errors, with larger errors having a more pronounced impact on the RMSE value81,82,83. The index of agreement (d) evaluates the consistency between predicted and observed values relative to the mean observed value, with a value of 1 indicating a perfect match81,84. Pearson”s coefficient (r) assesses the strength of correlation between two variables, while the coefficient of determination (R2) indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable83.

Results

Validation results of ENVI-met model using field data

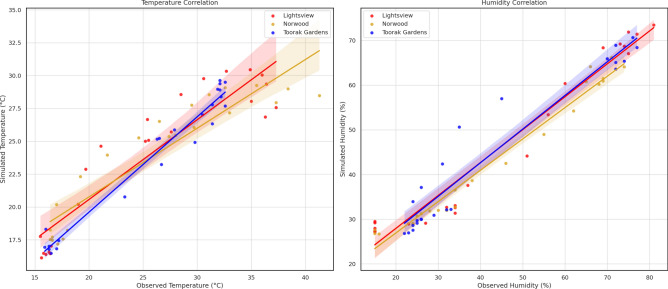

The comparison between measures site data and simulation data (Table 4) indicates a variation of less than 10% at RMSE and MAE compared to maximum recorded air temperature and relative humidity values, R2 > 0.85 and p < 0.001 for all the three sites. The highest model accuracy is at Toorak Gardens with RMSE < 5%, R2 = 0.98 for air temperature and p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Model validation statistics for Lightsview, Norwood and Toorak Gardens.

| Site | Metric | MAE | RMSE | Pearson r | R2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightsview | Temperature | 2.750 | 4.061 | 0.922 | 0.850 | < 0.001 |

| Humidity | 5.936 | 7.639 | 0.978 | 0.956 | < 0.001 | |

| Norwood | Temperature | 3.228 | 4.621 | 0.927 | 0.860 | < 0.001 |

| Humidity | 5.555 | 6.537 | 0.986 | 0.973 | < 0.001 | |

| Toorak Gardens | Temperature | 2.417 | 2.857 | 0.982 | 0.965 | < 0.001 |

| Humidity | 6.159 | 7.252 | 0.963 | 0.928 | < 0.001 |

The analysis of temperature data revealed that all sites exhibit Pearson correlation coefficients greater than 0.9 and Coefficients of Determination above 0.85, indicating a strong positive correlation between observed and simulated temperature values. Specifically, Toorak Gardens demonstrated the highest correlation in temperature (r = 0.982, R2 = 0.965), followed by Norwood (r = 0.927, R2 = 0.860), and Lightsview, though slightly lower (r = 0.922, R2 = 0.850), still indicated a close match between the simulated and observed temperatures. This suggests that the ENVI-met model is capable of simulating temperature variations in these areas with a high degree of accuracy.

The MAE and RMSE metrics offer another perspective on model precision, providing quantitative measures of the average and spread of errors, respectively. Toorak Gardens had the lowest MAE and RMSE values (2.417 and 2.857, respectively), indicating the smallest average difference and most tightly clustered errors between the simulated and observed temperatures. In contrast, Norwood’s error metrics were slightly higher, still reflecting favourable model performance with less than 10% error. Variations in these error metrics could be attributed to specific microclimatic conditions, topography, or other environmental factors unique to each site. Figure 5 shows the correlation between observed and simulated data across the three sites: Lightsview (red), Norwood (dark yellow), and Toorak Gardens (blue). The linear regression lines with confidence intervals support the performance of the ENVI-met model in simulating air temperature and relative humidity in diverse urban environments.

Fig. 5.

Air temperature and relative humidity validation for Lightsview, Norwood and Toorak Gardens.

For relative humidity, Norwood exhibited the highest correlation (r = 0.986, R2 = 0.973), followed closely by Lightsview (r = 0.978, R2 = 0.956), with Toorak Gardens displaying slightly lower yet still strong positive correlation (r = 0.963, R2 = 0.928). These high correlation metrics underscore the accuracy and reliability of the ENVI-met model in simulating relative humidity. The MAE and RMSE values for relative humidity reflect the absolute magnitude and distribution of prediction errors. Although Toorak Gardens showed the best performance in temperature simulation, its error metrics were higher for relative humidity (MAE = 6.159, RMSE = 7.252), possibly indicating that the model performance may vary across different meteorological parameters.

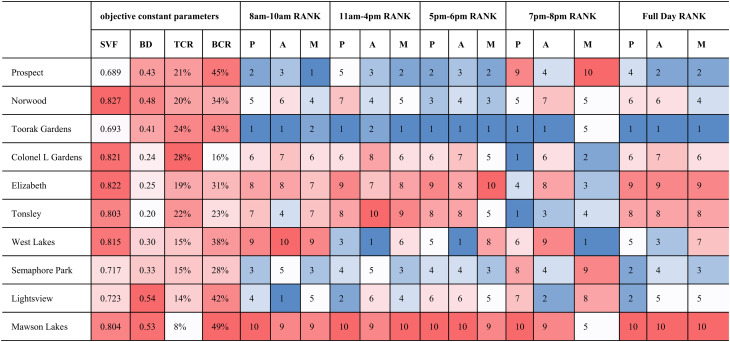

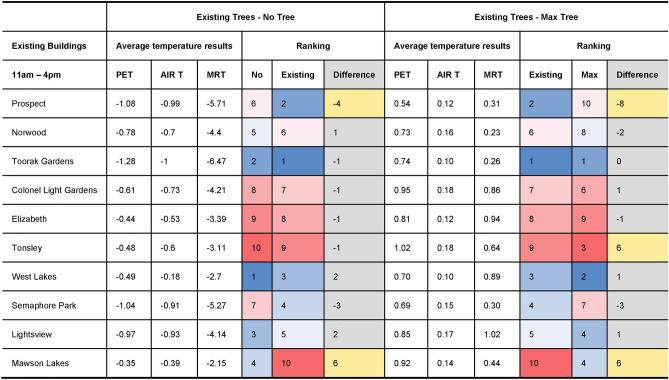

Thermal performance of case study sites with existing situation

The simulation outputs of Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET), air temperature (AIR T), and Mean Radiation Temperature (MRT) are used to rank the thermal performance of the 10 case study sites in existing, and adjusted density and tree canopy scenarios. During daytime, in the rankings, the three oldest neighborhoods Prospect, Norwood and Toorak Gardens fared the best (Table 5). Toorak Gardens performs the best throughout the day in the overall ranking. At the hottest time of the day (14:00), the potential air temperature (air T) reaches 45.39℃, the Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) stands at 54.67℃, and the mean radiation temperature (MRT) is 70.88℃. These values are 0.24℃, 0.29℃, and 2.09℃ lower, respectively, compared to the average of the 10 cases.

Table 5.

Ranking Performance by period of existing buildings & existing trees (BD = building density, TCR = tree cover rate, BCR = building cover rate, P = PET, A = AIR T, M = MRT) from 8am to 8 pm.

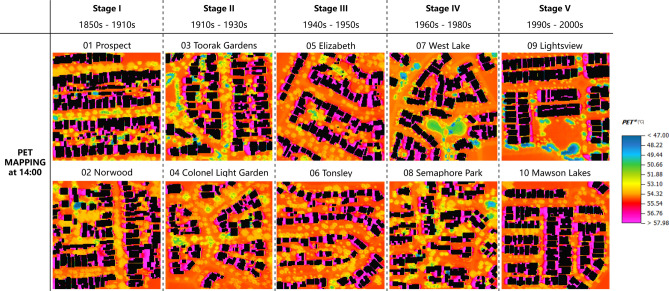

Figure 6 presents the PET mapping results for the 10 cases based on simulations at 2 pm, the hottest time of the day. In these maps, higher temperatures are indicated by pink hues, while lower temperatures are shown in blue. The Mawson Lakes project is noticeably hotter than the other cases, with colors predominantly orange, red and pink in Fig. 6. In fact, the Mawson Lakes project demonstrates the poorest thermal performance throughout the day (Appendix Table 1). At the hottest time, 2 pm, the air temperature (AIR T), Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET), and Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT) are respectively 0.34 °C, 0.35 °C, and 1.65 °C higher than the average values. Apart from Mawson Lakes, which ranks the lowest due to its extremely low tree coverage of just 8% (only a quarter to half of the coverage in other projects), the two neighborhoods of Elizabeth and Tonsley, both established in the 1940s and 1950s, consistently rank among the lowest for daytime thermal performance (Table 5). In the 2 pm simulation scenario, temperatures remain relatively high even under the trees in these two projects (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) mapping for 10 cases under the scenarios of existing buildings and existing trees (current conditions) at 2 pm.

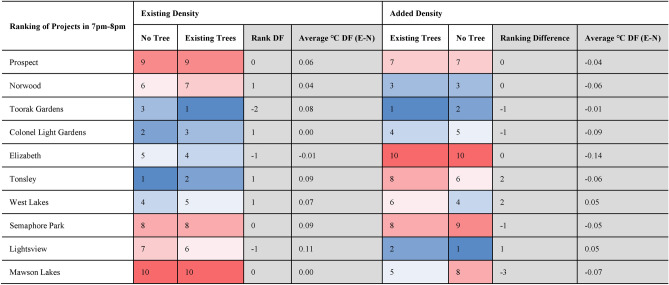

Thermal performance of case study sites with existing trees, existing density vs. added density

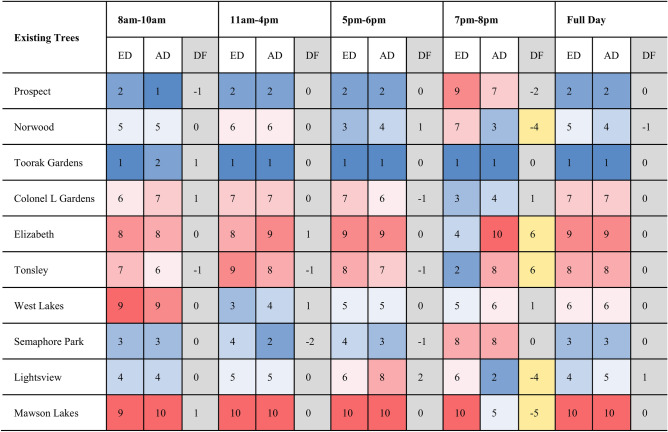

During daylight hours, without altering the existing trees, an augmentation in building density was attained by raising the height of several buildings. This resulted in a minimal enhancement in the temperatures of the three indicators (Table 6). Nevertheless, the ranking of the ten cases remained largely unaffected. This implies that the impact of density on the performance of the case studies is marginal.

Table 6.

Increase floors of part of existing buildings to achieve FAR = 0.55 (highest density among these 10 cases). (ED = existing building density, AD = added building density, DF = ranking difference).

Additionally, linear regression analysis revealed a moderate correlation (R2 = 0.66 or 0.65 > 0.6, and p = 0.0038 or 0.0044 < 0.05) between the increase in density and the average improvement in the three parameters across the ten cases during the midday to afternoon period (from 11 am to 6 pm).

Thermal performance of case study sites with existing density, max trees vs. existing trees vs. no trees

Based on the current building conditions of the site, during the hottest period of the day (11am-4 pm), trees can play a cooling role (Table 8, Fig. 7). When all trees are removed from the simulation model, the ranking of the Prospect site drops by 4 positions. Conversely, when all neighborhoods are maximally planted with trees, Prospect’s ranking drops by 8 positions, while Tonsley”s ranking increases by 6 positions (Table 8). This indicates that the outdoor thermal performance of these blocks is highly sensitive to the presence of trees.

Table 8.

Performance Ranking of 10 Cases in existing tree / no tree Situations and existing tree / max tree Situations with existing buildings during 11am to 4 pm. For ranking of each case between situations by time, those with big differences are marked yellow.

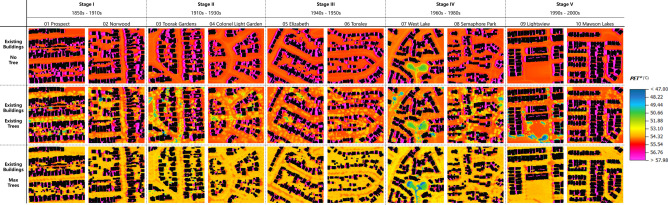

Fig. 7.

Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) mapping for 10 cases under the scenarios of existing buildings situation, but max trees vs. existing trees vs. no trees at 2 pm.

However, Mawson Lakes, which has the lowest existing tree canopy coverage (8%) and the poorest thermal performance among the case study sites, shows an increase in ranking by 6 positions under both the “no trees” and “maximum trees” scenarios (Table 8, Fig. 7). The relative ranking of Mawson Lakes under these two extreme tree planting scenarios is similar to that of Lightsview (Table 8), which was built in the same period (2000s). The relative performance of other case study areas show only minimal changes in ranking under the different tree scenarios (Table 8).

Thermal performance of case study sites at night

At night, between 7–8 pm, whether it’s existing buildings or buildings of similar density, with or without trees, the rankings hardly change. The absolute differences in the average temperature values are also generally minimal, with the largest being only 0.11℃, and others even less, much smaller than the daytime data from 11 am to 4 pm. This indicates that the thermal performance of case study sites during the nighttime is more impacted by the nighttime cooling than the presence of trees.

Discussion

Evaluation of the thermal performance of historical case study areas

All the neighborhoods exhibit significant thermal stress under heatwave conditions. Their thermal performance shows a correlation with the characteristics of their original built periods. For the results of the current simulation scenario (existing buildings and existing trees), excluding Mawson Lakes (lowest existing tree canopy coverage of just 8%, which is only 1/3 to 1/2 of the other projects (Table 2)), the thermal performance during the hottest daytime period (11 am–4 pm) follows a clear chronological pattern (Table 5). The older case study areas, Prospect and Norwood (both Victorian), as well as Toorak Gardens (1910s-1930s) outperformed the other areas. Toorak Gardens consistently performs the best under both the original scenario and all modified scenarios. The performance then drops with Colonel Light Gardens (1920s-1930s), while Elizabeth and Tonsley also display a worse performance (1940s-1950s). Mawson Lakes exhibits the poorest thermal performance under current conditions (Table 5; Fig. 6). However, in both the ‘no trees’ and ‘maximum trees’ planting scenarios, its performance becomes more aligned with that of Lightsview, a neighborhood constructed in the same period (2000s), reaching a moderately higher level (Table 8; Fig. 7). Therefore, it can be concluded that the significantly poor thermal performance of Mawson Lakes under current conditions is due to its minimal tree canopy coverage (8%). Excluding the specific case of Mawson Lakes, the workers’ housing districts of Tonsley and Elizabeth, built in the 1940s–1950s, consistently rank at the bottom across all scenarios (Tables 6, 7, 9). The performance again improves for the more recent case study areas of West Lakes, Semaphore Park and Lightsview, which are closer but still not as good as the oldest of Prospect, Norwood and Toorak Gardens.

Table 7.

Under existing tree / no tree situation, Linear regression analysis of building density increase, and temperature decrease at daytime (11am-4 pm).

| Regression statistics between difference of building area density increase & average temperature decrease (°C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple R | R Square | P-value | |

| Under Existing Trees Situation | 0.817196 | 0.667810 | 0.003893 |

| Under No Tree | 0.810282 | 0.656557 | 0.004477 |

Table 9.

Performance of 10 Cases in existing tree / no tree Situations at night (7-8 pm). DF(E-N) = existing trees situation temperature – no tree situation temperature.

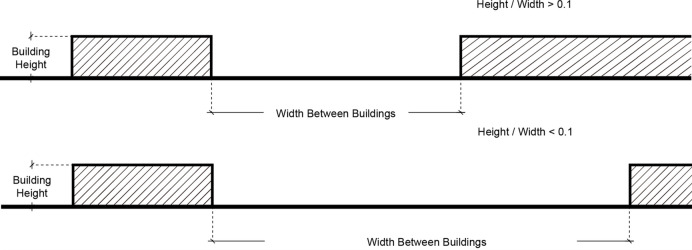

Effect of urban layout on outdoor thermal performance

The following patterns emerge based on the daytime performance rankings of the urban development patterns (Table 5). Surprisingly, the case studies with more organic and natural urban patterns, with curved roads and loosely arranged houses, such as Colonel Light Gardens (7), Tonsley (8) and Elizabeth (9), did not perform as well. The regular layout patterns with more densely spaced houses such as Toorak Gardens (1), Prospect (2), and Norwood (3) performed best. Toorak Gardens, the best performer, features concentrated, compact and regular building layout, generous green spaces (24%) and radial roads. The next best performers are Semaphore Park (4), Lightsview (5), and West Lake (6), which were all built after the 1960s. The common feature among the six best-performing case study areas is that the buildings are situated closer to each other in a more compact pattern than the three worst performers. Mawson Lakes performs the worst because its tree coverage rate too low (8%).

A comparative analysis of the simulation results (Table 5; Fig. 6) reveals that, surprisingly, the performance of Colonel Light Gardens, South Australia”s model garden city community85, was not as good as expected based on its “green” image. Its buildings are arranged according to an organic, curvilinear layout and the houses are not as close to each other. The post-war neighborhoods with more irregular patterns and dispersed house patterns also performed poorly, such as Elizabeth and Tonsley. These areas were established after World War II and were influenced by the “neighborhood” theory58, featuring winding streets and loosely arranged buildings. Previous studies have also shown that open public spaces in mid-density residential areas that are overly scattered tend to perform poorly, whereas those with a higher concentration of buildings and a more compact distribution are more conducive to achieving thermal comfort86. These results mean that dispersion of urban pattern can impact outdoor thermal comfort in suburban housing neighborhoods, while a more compact distribution and orderly arrangement can contribute to better thermal stress resilience.

The compactness of building distribution on either side of an urban canyon can be reflected by the ratio of building height (H) to the distance between buildings (W), denoted as H/W. A larger H/W ratio indicates a more compact layout. In the six best-performing case studies, the H/W ratio is greater than 0.1, compared to the other three cases where H/W < 0.1 (Fig. 8). The only outlier is Mawson Lakes with a H/W 0.16 because of its very low tree canopy cover (less than half of other areas). Previous studies have found that the height-to-width ratio (H/W) of buildings on both sides of the street has a great effect on outdoor thermal performance87,88,89,90.

Fig. 8.

Diagram showing height-to-width ratio (H/W) of buildings.

Additionally, the distance between buildings on the same side of the street can also reflect the dispersion of the urban pattern of houses. In the six best-performing case study areas, the buildings on the same side of the street are positioned closer together, leading to a better cooling effect. For instance, there are more row houses and semi-detached houses with shared walls, and the gaps between detached houses are narrower, often reduced to just a narrow alley (Fig. 9). The walls of buildings on both sides of these narrow alleys can absorb and reflect a significant portion of solar radiation91, as well as close proximity of the buildings also creates an adjacent shading effect, which contributes to cooling the structures92.

Fig. 9.

Street views of houses of the same side in Norwood (left) with less space in between versus in Tonsley (right). (Street views exported by Google Street View, further edited by Yue Liu. Images data: Nov 2023, Jan 2023, ©2024 Google.)

These observed patterns reflect that, in the older suburban residential areas of Adelaide, the relatively immutable elements of original urban planning (dispersion of urban pattern layout and buildings) tend to be more orderly and compact (H/W > 0.1), leading to better daytime outdoor thermal performance. This finding for these Adelaide case studies, situated in a Temperate Mediterranean climate, aligns with previous research conducted in Guangzhou (Tropical Monsoon Climate)87,88,89, Ghardaïa (Hot Desert Climate)71, and Santiago (Mediterranean Climate)93. Broad streets receive higher levels of solar radiation, resulting in higher temperatures71,93,87,88,89. The value of this study lies in evaluating these patterns in other development contexts. Previous research on aspect ratios has primarily focused on higher-density urban areas, with H/W values typically ranging from 0.5 to 6, whereas the suburban residential areas studied here have H/W values ranging from 0.08 to 0.1871,93,87,88,89,94. This underscores the significance of building distance and layout forms on spatially averaged outdoor thermal performance even in lower-density suburban areas.

Effects of density and trees on outdoor thermal performance

Development density

In this study, density demonstrates a minor positive impact on the thermal environment. Under the condition of maintaining existing urban layouts and suburban-style blocks (with FAR not exceeding 0.55), increasing building density has a minimal effect on thermal comfort in the area. Specifically, during the midday to afternoon period (from 11 am to 6 pm), the absolute values of temperatures stable generally decrease with increased density (Table 7). This finding is consistent with previous research conducted under conditions of moderate density and lower building heights, cooling by influencing (increasing) site wind speed87,89,95.

However, increasing building density resulted in a maximum of 0.49℃ improvement in temperature during 11am–4 pm (Appendix 1). Even with variations in densities, blocks with good performance maintain their ranking position, while those with poor performance still lag behind (Table 6). Compared to past study95, Adelaide buildings heights are too low, which limits their impact on enhancing wind speeds. It reveals that in the suburban areas of Adelaide, the potential for enhancing the thermal environment through increased density leads to only marginal improvements.

Tree coverage

As evident from the simulation results, street greening and the presence of concentrated green spaces overall have a positive impact on outdoor thermal performance across all case study areas (Table 8). During the hottest period of the day, the suburban areas in average show the best thermal comfort performance in scenarios with maximum planting potential, followed by existing trees, and then no trees, while maintaining the same urban pattern and building density. Prior research has emphasized the substantial impact of tree cover rates on the daytime outdoor thermal environment in Australian cities96,91,97,98,99.

Regarding relative rankings, different urban layout patterns formed under various building distribution strategies exhibit varying sensitivities to vegetation planting conditions (Tables 9 and 10). In most cases, the rankings under extreme planting scenarios, with consistent building conditions, show only minor differences when sunlight is abundant (11 am–4 pm). When the existing urban layout is maintained, trees appear to play a crucial role in mitigating high temperatures in areas like Prospect and Tonsley, indicating these blocks are more sensitive to tree conditions. Under the same building density (FAR = 0.55), the impact of existing trees and the absence of trees on rankings is more pronounced (see Tables 9 and 10). When trees were removed or maximum planting potential was applied to all study areas, Mawson Lakes, which originally had significantly lower green coverage, moved up from the last position to fourth in the ranking (Table 8).

Table 10.

Ranking of projects under existing situation in 11 am–4 pm and 7 pm–8 pm.

| Ranking of Projects Existing situation | 11am–4 pm | 7 pm–8 pm |

|---|---|---|

| Prospect | 2 | 9 |

| Norwood | 6 | 7 |

| Toorak Gardens | 1 | 1 |

| Colonel Light Gardens | 7 | 3 |

| Elizabeth | 8 | 4 |

| Tonsley | 9 | 2 |

| West Lakes | 3 | 5 |

| Semaphore Park | 4 | 8 |

| Lightsview | 5 | 6 |

| Mawson Lakes | 10 | 10 |

However, the distribution of thermal comfort levels within the neighborhoods is uneven (Fig. 6). Excluding areas inaccessible to pedestrians, such as the water surface of the West Lake, Fig. 6 shows that areas near densely planted large trees tend to have lower temperatures, whereas the highest temperature zones are concentrated near buildings. Large trees may be a lifeline for people staying outdoors during the daytime in a heatwave. Previous studies have also indicated that the thermal outdoor performance benefits from large trees are more pronounced100,101, particularly on wide streets102. In this study, it was observed that the case studies with smaller tree canopy sizes, constructed from the 1990s to the 2000s, still experienced warmer temperatures during the daytime, despite relatively orderly urban layouts and compact buildings. The tree canopy sizes of blocks from the 1850s to the 1930s were notably wider compared to those from the 1990s to the 2000s (refer to Fig. 2 maps), indicating significant growth of trees in older areas. Therefore, in newer neighborhood developments, prioritizing the planting of appropriately sized and fast-growing species of trees is advisable to mitigate the heat from excessive exposure of street surfaces to solar radiation.

The outdoor thermal performance at night (7 pm-8 pm) does not follow the daytime patterns. Under existing tree and building conditions, the order is reversed, except for Toorak Gardens still performing the best and Mawson Lakes still the worst (see Table 10). Previous research suggests that urban patterns with rapid daytime warming, due to a higher H/W ratio, also exhibit faster night-time cooling87,88,89. Additionally, this study found that the night-time ranking is hardly affected by removing trees (Table 9). The maximum observed night-time temperature change was 0.11℃ indicating a less pronounced impact of trees on night-time temperatures (Table 9).

Impact of planning approaches of the different historical periods on the thermal environment

Over the past 150 years, design theories have undergone a rapid evolution, transitioning from classical through to modern, postmodern and contemporary approaches. The evolution of urban areas during this period has been faster than at any other time in human history. In urban planning, practical applications have also been influenced by various prevailing ideologies, resulting in a wide range of suburban residential typologies across Australia during this period. However, unlike other design products, the influence of urban planning and design is long-lasting. In Adelaide, while new neighborhoods continue to be developed, older ones are still in use. The initial urban patterns and layouts have left a significant and enduring impact. For projects like Elizabeth and Tonsley, changes to vegetation and building height struggle to compensate for inherent design shortcomings in their urban layouts concerning heatwave resilience.

The trends identified in this study suggest that approaches and ideas, such as the loose planning of a garden city development or the neighborhood unit idea, while they may seem appealing aesthetically and intellectually, still need to be tested and simulated to determine their actual merits in practice. The classical suburban planning methods of the nineteenth century were largely developed pragmatic rectilinear patterns, guided by traditional knowledge and in many cases laid out by surveyors rather than professional urban designers103. As designers, planners and policymakers race to keep up with rapidly evolving technologies and ideas, they should also reflect on the experiences and lessons of these past practices. This reflection will help with designing more livable neighborhoods, preventing the creation of areas with heat risks that are difficult to mitigate once built.

Limitations and further research

Several limitations should be considered for this study. One of these is that wind simulation in the ENVI-met model is simplified. Full forcing of the wind data may cause simulation error or crash when values and directions are rapidly changing. To address these errors the authors have used a recent calm weather in Adelaide for validation and further simulation of the models while collecting site data simultaneously. Furthermore, the authors took into account that the ENVI-met simulation requires at least 2 h to build up the model data. Therefore, the initial 2 h of summation were not considered reliable. Our pilot studies indicate this condition may persist up to 7 h after initiating the simulation. Therefore, the authors have started the simulation at 12am and disregard the first 7 h of outputs until 7am. The next 13 h of simulation data was then used to explore microclimate, landscape and spatial patterns in a typical heatwave day in Adelaide. Finally, the tree coverage explored in this study included the density and coverage of greenery but does not include variabilities in tree species, nor their layouts. Further research can explore thee variables in an adjusted scale.

A key limitation is that this research is focused on selected case studies in Greater Adelaide. Further studies in other locations about the performance of different areas are important to develop more robust urban design theories. This research hopes to stimulate further case studies that can provide more detail about the elements that lead to better urban design. The findings of this research based on a limited selection of case studies should be compared in further research to test and verify its conclusions and add further detail.

Conclusion

The findings of this study can be summarized in these eight points:

Regarding the outdoor thermal comfort performance of the ten historical neighborhoods, the three oldest neighborhoods rank highest overall, while Mawson Lakes ranks the lowest due to its extremely low greenery coverage. The post-war“neighborhood unit”areas of Elizabeth and Tonsley also rank near the bottom.

The resilience of Adelaide’s typical suburban residential neighborhoods to heatwaves is closely related to their urban form, which has evolved over time. In general, the more regular neighborhoods from the classical period (1850s–1910s) and the early garden city of Toorak Gardens perform best. Performance then declines with the introduction of curvilinear street patterns and the dispersed layouts characteristics of“neighborhood units” developed after World War II. It improves slightly with the resort-style residential planning concept (from the 1970s onwards) and the more compact “New Urbanism” developments (from the 2000s onwards).

In this study, the urban typologies with compact and regular building patterns and surface layouts demonstrate better outdoor thermal comfort performance during the day than those with dispersed and curvilinear ones.

For the case study areas, a simulated increase in density consistently improves the thermal environment, although the cooling effect is relatively minor, with maximum temperature reductions not exceeding 0.5 degrees Celsius.

Trees, a more easily modifiable element, generally has a positive effect on the outdoor thermal performance of neighborhoods during the day. However, the sensitivity of different urban patterns to tree planting varies, and excessive planting could potentially block ventilation, preventing temperatures from dropping.

Large tree canopies were particularly effective at creating shade, but the areas around buildings tended to be the hottest due to reflected heat. For new neighborhoods, careful consideration should be given to selecting tree species with fast-growing canopies to achieve rapid greening and reduce heat exposure risks.

The impact of the initial planning vision, which determines the urban pattern and layout, is long-lasting and decisive for the outdoor thermal environment. The effectiveness of improving a neighborhood’s thermal environment by increasing building density or planting trees has its limits. If the foundational urban pattern and layout set by the initial planning are poor, it becomes challenging to mitigate the negative effects. Planners and decision-makers should avoid a blind pursuit of trendy formal green concepts or aesthetic master plan designs, and instead first test such new approaches, and learn from successful built examples.

Further suburban housing developments in Adelaide and similar climates should prioritize a compact, centralized, and regular in urban pattern and surface layout design.

In some cases, the outcomes of this study were counter-intuitive to the original urban planning ambitions of the tested case studies. Those developments, that promise better quality suburban life, do not necessarily provide cooler outdoor environments. For example, Colonel Lights Garden did not perform as well as Prospect, which was not planned as a Garden City but as a more typical, denser Victorian housing development. Many of the compact and regularly planned residential areas, which may not necessarily represent quality suburban living, outperformed those characterized by free-form, low-density dispersed developments. Residential areas can be meticulously planned with straight, regular streets and compact buildings and yet, perform thermally the best.

The suburban layout in more dispersed urban developments provided more space to plant trees, but at the same time, where buildings are spaced further apart, the ground surfaces exposed to solar radiation counteracted the cooling impact of trees. In those suburban developments, there were more open, exposed surfaces that absorbed solar radiation than tree canopies, which resulted in warmer outdoor environments. In contrast, in the development with more tree coverage than exposed open surfaces, heat mitigation was more pronounced. In these suburban developments, the cooling impact of tree canopies added to less exposed urban surfaces to the sun and a higher overall sky view factor (although the SVF is still much lower than in high-density urban environments).

Existing suburbs are under pressure to increase in density to address housing shortages. The tested scenarios indicate that for these case study areas with low-rise houses, existing building heights could potentially be increased to 3–4 stories without a negative impact on urban microclimates and the outdoor thermal comfort of residents. Furthermore, retaining existing trees and planting new large trees along bare streets would increase tree canopy coverage and reduce the sky view factor in suburban streets, thereby enhancing the thermal performance of the neighborhood during the day. In new construction projects, prioritizing compact building designs in streets with higher H/W ratios and planting large trees can help mitigate extreme weather conditions by reducing direct solar radiation absorbed by buildings and ground surfaces.

This study explores the impact of development layout, density and tree coverage on the thermal performance of 10 case study suburban sites since the late nineteenth century in Greater Adelaide. Overall, the findings from this study question popular planning assumptions such as garden city planning and support better micro-climate testing to achieve the intended green ambitions for future urban planning. Building patterns and surface layouts are critical determinants of thermal performance; therefore, future urban planning and design strategies in Adelaide and similar climates should prioritize a compact, centralized, and regular typology in this regard. It is crucial to note that the case studies in this paper are limited to specific low-density suburban areas in Greater Adelaide located in a warm temperate climate, and therefore, the results may not apply to high-density urban areas.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Y.L. conducted data collection, material preparation, and model setup. E.S. performed on-site meteorological data collection. Y.L., Y.Z., and Y.Q. L. conducted simulation runs. Y.L., Y.Z., and E.S. carried out data analysis. Y.L. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 5 and Y.Z. prepared Fig. 4. Y.L. wrote the main manuscript text, with revisions by D.K., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-77433-3.

References

- 1.Berry, M. Unravelling the “Australian Housing Solution”: The Post-War Years. Housing, Theory Soc.16(3), 106–123. 10.1080/14036099950149974 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Housing Occupancy and Costs. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/housing-occupancy-and-costs/latest-release. (2007).

- 3.Walters, P. The Vanishing Suburban Dream in Australia. Plan. Rev.57(3), 4–21. 10.1080/02513625.2021.2026646 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellett, J. The Australian quarter acre block: the death of a dream?. Town Plann. Rev.82(3), 263–284. 10.3828/tpr.2011.17 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loyn, R. H. & Menkhorst, P. W. The bird fauna of Melbourne: Changes over a century of urban growth and climate change, using a benchmark from Keartland (1900). Victorian Naturalist128(5), 210–232 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher, C. The changing character of Australian urban growth. Built Environ.11(2), 69–82 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison, G. Australian urban history: A progress report. Urban History6, 100–109 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mumford, E. Designing the Modern City: Urbanism Since 1850 (Yale University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Google Trends. Search interest for “Garden City” & “Compact City” [2023.07]. Retrieved from https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2012-01-01%202022-07-04&q=garden%20city,compact%20city. (2023).

- 10.Monteiro, J., Sousa, N., Natividade-Jesus, E. & Coutinho-Rodrigues, J. Benchmarking City Layouts—A Methodological Approach and an Accessibility Comparison between a Real City and theGarden City. Sustainability 14, 5029 (2022).

- 11.Afsharzadeh, M., Khorasanizadeh, M., Norouzian-Maleki, S. & Karimi, A. Identifying and Prioritizing the Design Attributes to Improve the Use of Besat Park of Tehran, Iran. Int. J. Archit. Eng.Urban Plan 31 (2021).

- 12.Unwin, R. Nothing Gained by Overcrowding!: How the Garden City Type of Development May Benefit Both Owner and Occupier. vol. Vol. 104 (Garden Cities and Town Planning Association,LONDON, 1918).

- 13.Comer, J. M. Garden City: Work, Rest, and the Art of Being Human. (Thomas Nelson, 2015).

- 14.Mohammadzadeh, N., Karimi, A. & Brown, R. D. The influence of outdoor thermal comfort on acoustic comfort of urban parks based on plant communities. Build. Environ.228, 109884. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109884 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jane, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. (1961).

- 16.Falah, N., Karimi, A. & Harandi, A. T. Urban growth modeling using cellular automata model and AHP (case study: Qazvin city). Model. Earth Syst. Environ.6(1), 235–248. 10.1007/s40808-019-00674-z (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang, L. et al. The Relationship between Spatial Characteristics of Urban-Rural Settlements and Carbon Emissions in Guangdong Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health20(3), 2659. 10.3390/ijerph20032659 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristjánsdóttir, S. Roots of Urban Morphology. Iconarp International J. of Architecture and Planning, 7(Special Issue ”Urban Morphology”), 15–36. 10.15320/ICONARP.2019.79. (2019).

- 19.Scheer, B. C. The epistemology of urban morphology. Urban Morphol.20(1), 5–17. 10.51347/jum.v20i1.4052 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders, P. & Baker, D. Applying urban morphology theory to design practice. J. Urban Design21(2), 213–233. 10.1080/13574809.2015.1133228 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira, V. Urban Morphology, in Oliveira, V., Urban Studies. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/obo/9780190922481-0004. (2020).

- 22.Sabrin, S. et al. Effects of different urban-vegetation morphology on the canopy-level thermal comfort and the cooling benefits of shade trees: Case-study in Philadelphia. Sustain. Cities Soc.66, 102684. 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102684 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shooshtarian, S., Lam, C. K. C. & Kenawy, I. Outdoor thermal comfort assessment: A review on thermal comfort research in Australia. Build. Environ.177, 106917. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106917 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schinasi, L. H., Benmarhnia, T. & De Roos, A. J. Modification of the association between high ambient temperature and health by urban microclimate indicators: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res.161, 168–180. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.004 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke, A. et al. Reified scarcity & the problem space of “need”: unpacking Australian social housing policy. Housing Stud.39(2), 565–583. 10.1080/02673037.2022.2057933 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trancoso, R. et al. Heatwaves intensification in Australia: A consistent trajectory across past, present and future. Sci. Total Environ.742, 140521. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140521 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adnan, M. S. G. et al. Vulnerability of Australia to heatwaves: A systematic review on influencing factors, impacts, and mitigation options. Environ. Res.213, 113703. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113703 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coates, L. et al. Heatwave fatalities in Australia, 2001–2018: An analysis of coronial records. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.67, 102671. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102671 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong, S. et al. The impact of heatwaves on mortality in Australia: a multicity study. BMJ Open4(2), e003579. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003579 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Primary Industries and Regions. Climate trends and projections for SA, Government of South Australia. https://pir.sa.gov.au/primary_industry/climate_change_adaptation/climate_trends_and_projections#:~:text=Average%20temperatures%20in%20South%20Australia,Australia%20have%20occurred%20since%202005. (2024).

- 31.Nishant, N. et al. Future population exposure to Australian heatwaves. Environ. Res. Lett.17(6), 064030. 10.1088/1748-9326/ac6dfa (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ossola, A. et al. Small vegetated patches greatly reduce urban surface temperature during a summer heatwave in Adelaide, Australia. Landsc. Urban Plann.209, 104046. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104046 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freestone, R. Progress in Australian planning history: Traditions, themes and transformations. Progr. Plann.91, 1–29. 10.1016/j.progress.2013.03.005 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantin, R. et al. Field assessment of thermal behaviour of historical dwellings in France. Build. Environ.45(2), 473–484. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2009.07.010 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caro, R. & Sendra, J. J. Are the dwellings of historic Mediterranean cities cold in winter? A field assessment on their indoor environment and energy performance. Energy Build.230, 110567. 10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110567 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh, M. K. et al. Assessment of thermal comfort in existing pre-1945 residential building stock. Energy98, 122–134. 10.1016/j.energy.2016.01.030 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosso, F. et al. On the impact of innovative materials on outdoor thermal comfort of pedestrians in historical urban canyons. Renew. Energy118, 825–839. 10.1016/j.renene.2017.11.074 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang, K.-T. et al. Identifying outdoor thermal risk areas and evaluation of future thermal comfort concerning shading orientation in a traditional settlement. Sci. Total Environ.626, 567–580. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.031 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman, J. S., Shandas, V. & Pendleton, N. The effects of historical housing policies on resident exposure to intra-urban heat: A study of 108 US Urban Areas. Climate8(1), 12. 10.3390/cli8010012 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qian, Y. et al. A year-long field investigation on the spatio-temporal variations of occupant”s thermal comfort in Chinese traditional courtyard dwellings. Build. Environ.228, 109836. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109836 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sözen, İ & Koçlar Oral, G. Outdoor thermal comfort in urban canyon and courtyard in hot arid climate: A parametric study based on the vernacular settlement of Mardin. Sustain. Cities Soc.48, 101398. 10.1016/j.scs.2018.12.026 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yıldırım, M. Shading in the outdoor environments of climate-friendly hot and dry historical streets: The passageways of Sanliurfa, Turkey. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev.80, 106318. 10.1016/j.eiar.2019.106318 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biqaraz, B., Fayaz, R. & Haghighaat Naeeni, G. A comparison of outdoor thermal comfort in historical and contemporary urban fabrics of Lar City. Urban Clim.27, 212–226. 10.1016/j.uclim.2018.11.007 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darbani, E. S. et al. Urban design strategies for summer and winter outdoor thermal comfort in arid regions: The case of historical, contemporary and modern urban areas in Mashhad, Iran. Sustain Cities Soc.89, 104339. 10.1016/j.scs.2022.104339 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng, X. et al. Influence of built environment on outdoor thermal comfort: A comparative study of new and old urban blocks in Guangzhou. Build. Environ.234, 110133. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110133 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tablada, A. et al. On natural ventilation and thermal comfort in compact urban environments – the Old Havana case. Build. Environ.44(9), 1943–1958. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2009.01.008 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan, W. & Du, J. Towards sustainable urban redevelopment: urban design informed by morphological patterns and ecologies of informal settlements. in Urban Ecology. Elsevier, pp. 377–411. 10.1016/B978-0-12-820730-7.00020-3. (2020).

- 48.Aghamolaei, R. et al. A comprehensive review of outdoor thermal comfort in urban areas: Effective parameters and approaches. Energy Environ.34(6), 2204–2227. 10.1177/0958305X221116176 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karimi, A. et al. Evaluation of the thermal indices and thermal comfort improvement by different vegetation species and materials in a medium-sized urban park. Energy Reports6, 1670–1684. 10.1016/j.egyr.2020.06.015 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu, D. et al. Field measurement study on the impacts of urban spatial indicators on urban climate in a Chinese basin and static-wind city. Build. Environ.147, 482–494. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.10.042 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linn, R. Those Turbulent Years: A History of the City of Adelaide: 1929–1979. Adelaide City Council. (2006).

- 52.Michael, L.-S. Behind the scenes: The politics of planning Adelaide 1st edn. (University of Adelaide Press, 2012). 10.1017/9781922064417. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandercock, L. Property, politics and power: a history of city planning in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney since 1900”, Thesis (Ph.D)--Australian National University, 1974. (1974).

- 54.Mcgreevy, M. Suburban growth in Adelaide, South Australia, 1850–1930: speculation and economic opportunity. Urban Hist 44, 208–230 (2017).

- 55.Hoskins, I. Anticipating municipal parks: London to Adelaide to garden city. J. Australian Stud.38(4), 507–508. 10.1080/14443058.2014.957749 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson, D. L. Anticipating municipal parks: London to Adelaide to garden city (Wakefield Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harper, B. Y. COLONEL LIGHT GARDENS—SEVENTY YEARS OF A GARDEN SUBURB: The plan, the place and the people. Australian Planner29(2), 62–69. 10.1080/07293682.1991.9657506 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alan, H. & Christine, G. The Evolution of Suburban Design in Metropolitan Adelaide. Adelaide, S. Aust.: SOAC : Causal Productions. (2007).

- 59.Casey, T.M. GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES ACT. The South Australian Government Gazette. Government of South Australia. p. 1035. Retrieved 15 July 2019. (1976).

- 60.COCS. The History of West Lakes, City of Charles Sturt. https://www.charlessturt.sa.gov.au/community/arts-culture-and-history/local-history/our-stories/the-history-of-west-lakes. (2024).

- 61.COP. Our History The rich history of Prospect, City of Prospect. https://www.prospect.sa.gov.au/council/about-city-of-prospect/our-history (Accessed: 5 September 2024). (2024).

- 62.Dallwitz, J. & Marsden, A. HERITAGE INVESTIGATIONS BURNSIDE HERITAGE SURVEY (SOUTH AUSTRALIA) PART ONE GENERAL REPORT (amended July 1987). DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND PLANNING. https://data.environment.sa.gov.au/Content/heritage-surveys/3-Burnside-Heritage-Survey-Part-1-General-Report-1987.pdf. (1987).

- 63.Garnaut, C. & Hutchings, A. The Colonel Light Gardens Garden Suburb Commission: building a planned community. Plann. Perspect.18(3), 277–293. 10.1080/02665430307972 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grainger, G. Richards & Chrysler Australia (Keswick & Mile End South). West Torrens Historical Society Inc. (2023).

- 65.MARK BUTCHER ARCHITECTS. KENSINGTON & NORWOOD HERITAGE REVIEW. MARK BUTCHER ARCHITECTS. https://data.environment.sa.gov.au/Content/heritage-surveys/2-Kensington-and-Norwood-Heritage-Review-Vol-1-1995.pdf. (1995).

- 66.RSA. Lightsview resident profile: Todd Zadow, Renewal SA. https://renewalsa.sa.gov.au/news/lightsview-resident-profile-todd-zadow. (2022).

- 67.The Advertiser. Adelaide”s newest suburb Tonsley is born on old Mitsubishi site ADELAIDE”S newest suburb has officially been created — but you probably already called it by its new name anyway. The Advertiser, 6 February. https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/messenger/south/adelaides-newst-suburb-tonsley-is-born-on-old-mitsubishi-site/news-story/a101c69459baa0c300951cd5507aa5ca. (2017).

- 68.Lam, C. K. C. et al. A review on the significance and perspective of the numerical simulations of outdoor thermal environment. Sustain. Cities Soc.71, 102971. 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102971 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu, Z. et al. Heat mitigation benefits of urban green and blue infrastructures: A systematic review of modeling techniques, validation and scenario simulation in ENVI-met V4. Build. Environ.200, 107939. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107939 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aleksandrowicz, O., Saroglou, T. & Pearlmutter, D. Evaluation of summer mean radiant temperature simulation in ENVI-met in a hot Mediterranean climate. Build. Environ.245, 110881. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110881 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ali-Toudert, F. & Mayer, H. Numerical study on the effects of aspect ratio and orientation of an urban street canyon on outdoor thermal comfort in hot and dry climate. Build. Environ.41(2), 94–108. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.01.013 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fahmy, M. & Sharples, S. On the development of an urban passive thermal comfort system in Cairo, Egypt. Build. Environ.44(9), 1907–1916. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2009.01.010 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu, Z. et al. Modeling microclimatic effects of trees and green roofs/façades in ENVI-met: Sensitivity tests and proposed model library. Build. Environ.244, 110759. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110759 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salata, F. et al. Urban microclimate and outdoor thermal comfort. A proper procedure to fit ENVI-met simulation outputs to experimental data. Sustain. Cities Soc.26, 318–343. 10.1016/j.scs.2016.07.005 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Borg, M. A. et al. Current and projected heatwave-attributable occupational injuries, illnesses, and associated economic burden in Australia. Environ. Res.236, 116852. 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116852 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wondmagegn, B. Y. et al. Understanding current and projected emergency department presentations and associated healthcare costs in a changing thermal climate in Adelaide, South Australia. Occup. Environ. Med.79(6), 421–426. 10.1136/oemed-2021-107888 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ladybug Tools. Ladybug Tools EPW Map. Retrieved from https://www.ladybug.tools/epwmap/. (2023).

- 78.Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Latest weather observations for the Adelaide area. Retrieved January 22–23, 2024, from http://www.bom.gov.au/sa/observations/adelaide.shtml?ref=hdr. (2024).

- 79.Ghorbankhani, Z., Zarrabi, M. M. & Ghorbankhani, M. The significance and benefits of green infrastructures using I-Tree canopy software with a sustainable approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain.10.1007/s10668-023-03226-9 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parmehr, E. G. et al. Estimation of urban tree canopy cover using random point sampling and remote sensing methods. Urban Forest. Urban Green.20, 160–171. 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.08.011 (2016). [Google Scholar]