Abstract

Mother’s curse refers to male-biased deleterious mutations that may accumulate on mitochondria due to its strict maternal inheritance. If these mutations persist, males should ideally compensate through mutations on Y-chromosomes given its strict paternal inheritance. Previous work addressed this hypothesis by comparing coevolved and non-coevolved Y-mitochondria pairs placed alongside completely foreign autosomal backgrounds, expecting males with coevolved pairs to exhibit greater fitness due to Y-compensation. To date, no evidence for Y-compensation has been found. That experimental design assumes Y-chromosomes compensate via direct interaction with mitochondria and/or coevolved autosomes are unimportant in its function or elucidation. If Y-chromosomes instead compensate by modifying autosomal targets (or its elucidation requires coevolved autosomes), then this design could fail to detect Y-compensation. Here we address if Y-chromosomes ameliorate mitochondrial mutations affecting male lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Using three disparate populations we compared lifespan among males with coevolved and non-coevolved Y-mitochondria pairs placed alongside autosomal backgrounds coevolved with mitochondria. We found coevolved pairs exhibited lower mortality risk relative to non-coevolved pairs. In contrast, no such pattern was observed when coevolved and non-coevolved pairs were placed alongside non-coevolved autosomes, as with previous studies. These data are consistent with Y-compensation and highlight the importance of autosomes in this capacity. However, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that Y-autosomal coevolution independent of mitochondrial mutations contributed to our results. Regardless, modern practices in medicine, conservation, and agriculture that introduce foreign Y-chromosomes into non-coevolved backgrounds should be used with caution, as they may disrupt Y-autosome coadaptation and/or inadvertently unbridle mother’s curse.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Evolutionary biology

Mother’s curse refers to the potential accumulation of male-biased deleterious mutations on the mitochondria that cannot be directly purged by natural selection due to the mitochondria’s strict maternal inheritance (Frank and Hurst 1996; Gemmell et al. 2004). Male-specific traits are expected to be the most susceptible to these mutations given that there is no direct counter selection in females, but it may also include traits susceptible to impaired energetic processes. Accordingly, sperm function is highly sensitive to mitochondrial variation in humans (St John et al. 2005; Kao et al. 1995; Ruiz-Pesini et al. 2000a; Ruiz-Pesini et al. 2000b; Cummins 1998; Holyoake et al. 2001), fruit flies (Dowling et al. 2007; Patel et al. 2016; Yee et al. 2013), and roosters (Froman and Kirby 2005). Traits shared by males and females are also susceptible, as implied by the male-biased incidence for Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy; a human mitochondrial dysfunction disease in a trait exhibited by both sexes (Milot et al. 2017). The breadth of mother’s curse effects on male phenotypes is currently unknown, though it may be extensive considering that mitochondrial variation in Drosophila fruit flies were shown to affect 10% of male genome transcripts while only affecting 0.6% of female transcripts (Innocenti et al. 2011).

If mother’s curse mutations are not purged or compensated for by mutations elsewhere in the genome, then their accumulation would eventually erode male fitness. Theory suggests that the purging of mother’s curse mutations can occur indirectly through inbreeding and kin selection (Keaney et al. 2020; Unckless and Herren 2009; Wade and Brandvain 2009), positive assortative mating (Hedrick 2012), and/or the paternal leakage of mitochondria during fertilization (Kuijper et al. 2015). Evidence for direct mitigation through compensation comes from mitochondrial replacement studies in D. melanogaster. Clancy et al. (2008, 2011) showed that the Brownsville mitochondrial haplotype (derived from Brownsville, TX) induced male sterility when placed into a non-coevolved genetic background (strain W1118) but had no effect on female fertility, suggesting that suppression of the male-biased sterility mutation existed within the Brownsville nuclear genome. Further, Yee et al. (2013) showed that mitochondrial haplotypes derived from distinct populations (including the Brownsville haplotype) consistently reduced male fertility when placed in a non-coevolved background, consistent with the original nuclear genome suppressing mitochondrial deleterious effects. Although these studies did not determine the nature and location of the compensatory mutations, a recent simulation study predicted that suppressors of mother’s curse should fix fastest on the Y-chromosome (Ågren et al. 2019). This makes sense, considering that autosomes and X-chromosomes spend half to two thirds of their time in females (respectively), while Y-chromosomes are present only in males and free to evolve without female counterselection.

To date three studies have examined the Y-chromosome’s potential for mother’s curse compensation. All studies used Drosophila melanogaster to introgress Y-chromosomes and mitochondria from disparate populations into a foreign nuclear background and then compared male performance between those who possessed coevolved and non-coevolved Y-chromosomes and mitochondria. The underlying tenet of this design is that Y-linked suppressors of mother’s curse would be specific to their coevolved mitochondria, causing those with non-coevolved genetic elements to suffer the effects of the deleterious mutations. Dean et al. (2015) tested locomotion with four genotypic combinations (2 coevolved, 2 non-coevolved), Yee et al. (2015) tested fertility and mating success with nine genotypic combinations (3 coevolved, 6 non-coevolved), while Ågren et al. (2020) examined male lifespan with 36 genotypic combinations (10 coevolved, 26 non-coevolved). All studies found no evidence for Y-linked compensation.

Although these results may accurately reflect that Y-chromosomes do not compensate, they may also stem from an experimental limitation. All three studies addressed compensation by comparing coevolved and non-coevolved mitochondria / Y-chromosome pairs placed in an autosomal background that was foreign to both Y’s and mitochondria (stock W1118). This experimental design implicitly assumes that Y-compensation operates via direct interaction with mitochondria and/or that Y-compensation is independent of autosome evolutionary history (hence the use of a non-coevolved isogenic background, W1118). These assumptions may be incorrect.

Mother’s curse likely creates non-optimal male phenotypes by modifying autosomal gene regulation (Innocenti et al. 2011), though altered mitochondrial products may also be created (e.g., cytochrome oxidase hypomorph, Patel et al. 2016). Growing evidence further suggests that the nuclear genome compensates for mitochondria mutational load (Burton et al. 2013; Ellison and Burton 2006; Wolff et al. 2014). If Y-chromosomes compensate, they are more likely do so by modifying the same autosomal targets affected by the mitochondria or genes associated with the same disrupted phenotype (Rogell et al. 2014). Furthermore, both autosomes and Y-chromosomes can theoretically compensate for mother’s curse concurrently within a single genome. Assuming these points are true, then the use of non-coevolved autosomes (e.g. W1118) in the search for Y-compensation introduces several potential issues. First, due to their independent evolutionary history the non-coevolved autosomes would lack the capacity to compensate for at least some mother’s curse mutations, maladaptively modifying the target phenotype and reducing fitness. Second, the non-coevolved autosomes would themselves possess compensatory mutations for mother’s curse mutations that do not exist on the experimental mitochondria, again shifting the phenotype and leading to fitness depression. Third, Y-compensatory mutations for mother’s curse would exist without the appropriately coevolved autosomal transcription architecture or autosomal alleles. Fourth, autosome-mitochondrial coadaptation independent of mother’s curse would be disrupted. And fifth, autosome-Y-chromosome coadaptation independent of mother’s curse would be disrupted. All five caveats could lead to unpredictable epistatic modifications to the phenotype and to fitness in both the control and experimental groups of previous works (Fig. 1). Due to this experimentally induced epistasis, the control group (coevolved Y’s and mitochondria) could at times exhibit lower fitness compared with the experimental group (all non-coevolved genetic elements). Furthermore, Y-compensation that acted via the autosomes would become non-functional. In short, the use of non-coevolved autosomes by previous works would likely obscure Y-compensation that acted directly on mitochondria or inhibit Y-compensation that acted directly on autosomes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The importance of autosomal background when assessing the potential for Y-compensation.

A A random mother’s curse mutation (−m) arises that decreases the male phenotype, followed by the evolution of a compensatory Y-chromosome mutation ( + y) that restores the optimal phenotype (black circle). Over time, multiple mutations may evolve to affect the same phenotype (e.g. +m) including compensatory autosomal mutations (−a). Arrows represent the magnitude and direction of mutational effects. Arithmetic operators also indicate mutation direction (i.e. ‘+’ increases and ‘−’ decreases the phenotype). B When coevolved mitochondria and Ys are experimentally joined with non-coevolved autosomes, random phenotypic deviations likely result (dashed line). This is due to disruption of mitochondria-autosome coadaptation (likely a major impact) as well as non-coevolved autosomes containing unique autosomal compensatory mutations where no mitochondrial mutation exists ( + a) or that leave some mitochondrial mutations ( + m) uncompensated. Arrows of the same color represent coevolved genetic elements. C Here, all elements are non-coevolved and experimentally joined, again randomly altering the phenotype. Previous Y-compensation tests compared panels (B) and (C), predicting panel (C) would possess a suboptimal phenotype due to the absence of appropriate Y-compensation. However, this design could result in coevolved mito/Y pairs (panel B) exhibiting suboptimal phenotypes compared to non-coevolved pairs (panel C) and suggest Y-compensation does not exist. D Here, only the Y-chromosome is non-coevolved. When compared with panel (A) (our current design), phenotypic deviations would be due to a lack of Y-compensation or disruption of Y-autosome coevolution (an assumed minor impact compared to disruption of mito-autosome coadaptation). Panels (A–D) represent genotypes YAM, YaM, yam, and yAM, respectively, in our current experimental design.

Determining if Y-compensation occurs will improve our understanding of genome function and evolution. Further, if Y-linked compensation exists, it would have important implications for medicine, conservation, and agriculture. For instance, mitochondrial replacement therapy is a novel procedure in which women suffering mitochondrial disease have their eggs’ nucleus placed inside a donor cell free of disease (Reinhardt et al. 2013). Finding a donor whose mitochondria share coevolutionary history with the father’s Y-chromosome may avoid unforeseen impacts of mother’s curse. Likewise, conservationists and agricultural breeders may consider these results when introducing new males (Y-chromosomes) or females (mitochondria) into a population (Leeflang et al. 2022; Smith et al. 2010), balancing such factors as hybrid vigor against the unbridling of mother’s curse.

Here we addressed if Y-chromosomes could ameliorate mitochondrial mutations affecting male lifespan using three disparate populations of Drosophila melanogaster. To eliminate the caveats listed above, we compared lifespan among males with coevolved autosomes, mitochondria, and Y-chromosome from each population (control group) to those possessing a novel Y-chromosome (experimental group), under the assumption that a novel Y-chromosome cannot appropriately compensate for mother’s curse via direct Y-mitochondrial and/or Y-autosomal interactions. As a comparison, we also recreated the design of previous works by comparing those with coevolved Y-chromosome/mitochondria pairs to those with non-coevolved pairs, all within a completely foreign autosomal background. Our current design improves upon previous works by not suffering any of the aforementioned caveats in either the control or experimental groups. The only exception being the potential disruption of Y-autosome coadaptation independent of mother’s curse in our experimental group (caveat 5 above).

Methods

Experimental design

To examine the potential for Y-compensation of mother’s curse, we obtained three inbred D. melanogaster stocks from the National Drosophila Species Stock Center (NDSSC): Montpellier, France; Cusco, Peru; and Cape Town, South Africa. We hereafter refer to these stocks as F, P, and S, respectively. The F, P, an S parental stocks were received as inbred lines, but likely contained some genetic variation and were not isogenized prior to our use. These stocks were chosen because they are geographically distant from each other and have a high likelihood of genetic divergence between lines. With these stocks, we created five treatments based on the coevolutionary relationships among the Y-chromosomes (Y), autosomes (A), and mitochondria (M) genetic elements: (1) the YAM treatment had all three elements coevolved with each other (i.e. from the same population stock), (2) the yAM treatment had only the autosomes and mitochondria coevolved, with the Y originating from a foreign population (Note: lower case letters represent non-coevolved elements while capital letters represent coevolved elements), (3) the YaM treatment had only the Y-chromosome and mitochondria coevolved with the autosomes from a foreign population, (4) the YAm treatment had only the Y and autosomes coevolved with the mitochondria from a foreign population, and (5) the yam treatment had no elements coevolved. In total we created 27 different genotypes across the five treatments (Table 1). For example, the YAM treatment contained genotypes FFF, PPP, and SSS, while the yAM treatment contained genotypes sFF, pFF, pSS, fSS, fPP, and sPP. Thus, a male with a Y-chromosome and mitochondria from Peru and autosomes from South Africa would have the genotype PsP and be placed in the YaM treatment.

Table 1.

Treatment genotypes and their creation.

| Y-Line X M-Line | Genotype | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| FFF X -FF | FFF | YAM |

| PPP X -PP | PPP | YAM |

| SSS X -SS | SSS | YAM |

| FPP X -PP | fPP | yAM |

| FSS X -SS | fSS | yAM |

| PFF X -FF | pFF | yAM |

| PSS X -SS | pSS | yAM |

| SFF X -FF | sFF | yAM |

| SPP X -PP | sPP | yAM |

| FPP X -PF | FpF | YaM |

| FSS X -SF | FsF | YaM |

| PFF X -FP | PfP | YaM |

| PSS X -SP | PsP | YaM |

| SFF X -FS | SfS | YaM |

| SPP X -PS | SpS | YaM |

| SSS X -SP | SSp | YAm |

| SSS X -SF | SSf | YAm |

| PPP X -PS | PPs | YAm |

| PPP X -PF | PPf | YAm |

| FFF X -FS | FFs | YAm |

| FFF X -FP | FFp | YAm |

| FPP X -PS | fpa | yam |

| FSS X -SP | fsp | yam |

| PFF X -FS | pfs | yam |

| PSS X -SF | psf | yam |

| SFF X -FP | sfp | yam |

| SPP X -PF | spf | yam |

From these treatments, we created two tests of the Y-compensation hypothesis. The first test replicates the experimental design from previous studies (Dean et al. 2015; Yee et al. 2015) and compared coevolved versus non-coevolved mitochondria/Y-chromosome pairs within a non-coevolved autosomal background (i.e. YaM vs yam). The second test compared coevolved and non-coevolved mitochondria/Y-chromosome pairs within an autosomal background that was always coadapted with the mitochondria (i.e. YAM vs yAM). Each genotype was then assessed for differences in lifespan under the assumption that greater lifespan represents the superior trait value.

Genotype creation

To create the 27 experimental genotypes, we first established 9 Y-lines and 9 M-lines (Table 1). Y-lines were created by first taking a single male from each stock (F, P, and S) and separately crossing him with virgin females from each stock (F, P, or S). The resulting F1 male offspring were then backcrossed with virgin females from one of the original stocks for 10 generations. This method established a single Y-chromosome from each stock into the background of each stock. After 10 generations of backcrossing, the genetic background of the newly established Y-lines are over 99.9% similar to the original stock (Supplementary Fig. 1). M-lines were similarly created by taking a single female from each stock and mating her with males from each stock, followed by 10 generations of backcrossing to males of the original stocks. As before, this establishes a single mitochondrion from each stock into the genetic background of each stock. To create the experimental genotypes, Y-lines and M-lines were crossed as shown in Table 1. To be consistent with previous work examining Y-compensation for mother’s curse, tetracycline-laced medium (0.3 mg/mL) was used in each line for several generations prior to the creation of experimental lines to minimize Wolbachia infections. Although the absence of Wolbachia was not experimentally verified in our study, the test of our hypothesis never compared genotypes that could have possessed different Wolbachia strains considering that all statistical comparisons were constrained to the same coevolved autosomal-mitochondrial group (AMgroup). Thus, if the antibiotic treatment was ineffective, all comparisons would possess the same Wolbachia strain.

Given our breeding design and the approximate 13,900/3800 coding/non-coding genes in the D. melanogaster genome (Kaufman 2017), we estimate approximately 14/4 genes in each line may have failed to be replaced by the target genome from backcrossing during line creation. Given (i) this low number of genes, (ii) that multiple mother’s curse and compensatory mutations likely affect lifespan, and (iii) the number of independent genotypes used to test our hypothesis, we contend that those genes that failed to be replaced likely had little impact on our results. We note a low but non-zero probability existed that Y and mito variation existed in each parental stock due to stock drift. Based on our experimental design (i.e. starting with a single male for Y-lines and single female for M-lines), however, Y and M-lines likely contained only a single haplotype each. There was also a non-zero probability that paternal leakage during genotype creation could theoretically contribute variation to these lines, but we also contend that this probability was small.

Trait measurement

Lifespan is an ideal trait to assess mother’s curse compensation as it is central to organismal fitness, exhibits sexual dimorphism, and has been shown to experience mother’s curse in previous studies (Aw et al. 2017; Camus et al. 2012). Roughly 200 male flies from a single cohort were collected over 4 days for each genotype. To ensure virginity, flies were collected on the day of eclosion and placed into male-only vials containing 25 individuals and Nutri-fly medium (Genesee Scientific #66-121). Vials were checked daily for mortality and all flies were followed until death. Flies were transferred to fresh vials once every 7 days using light CO2 anesthesia. Dead flies were not transferred.

Statistical analysis

Prior to any hypothesis tests, we utilized our fully factorial design to assess the impact of the genetic elements (Y, A, and M) and their interactions on lifespan via a Linear Mixed Model (normal distribution, identity link function), with vial included as a model random factor. From this model, least squares means were generated for each genotype, which were used to determine if the genetic element variants were evolutionary diverged from each other based on their phenotypic effect. In other words, did phenotypic differences in lifespan exist among the variants of a particular genetic element (e.g. mitochondria) when other genetic elements were held constant. Differences in least squares means were assessed as independent contrasts using JMP Pro 17.0.0. All other analysis were conducted in R 4.4.1.

The first test of the hypothesis compared males who possessed a coevolved Y-chromosome and mitochondrion in a foreign autosomal background (YaM treatment) with males whose genetic elements were all non-coevolved (yam treatment). This test represents the methods from previous studies where Y and mitochondria were introgressed into a non-coevolved W1118 background (Dean et al. 2015; Yee et al. 2015). To assess the effects of treatment, we used a Cox Proportional Hazard mixed model to estimate treatment hazard ratios, as lifespan represents “time-to-event” data (i.e. day of mortality). Specifically, we tested if the coevolved YaM treatment had a predicted lower hazard ratio than the non-coevolved yam treatment, while including the autosome-mitochondrial group (AMgroup) and vial as random model effects (note that a lower hazard ratio indicates a lower mortality risk). AMgroup was included to minimize autosome-mitochondrial group differences on mortality. Vial was included to minimize common environment effects. This represents the global test of the hypothesis, as it included all 12 genotypes. For exploratory and illustrative purposes, we also tested treatment differences for each AMgroup pair (PfP vs. sfp, SfS vs. pfs, FpF vs. spf, SpS vs. fps, FsF vs. psf, and PsP vs. fsp) while including vial as a random model effect.

The second test of the hypothesis compared males who possessed all coevolved genetic elements (YAM treatment) with males whose Y-chromosome was not coevolved with the remaining elements (yAM treatment) and represents our novel approach. Specifically, we tested if the coevolved YAM treatment had a predicted lower hazard ratio than the non-coevolved yAM treatment, while including the autosome-mitochondrial group (AMgroup) and vial as random model effects. Again, this represents the global test of the hypothesis, as it included all 12 genotypes. For exploratory and illustrative purposes, we also tested treatment differences for each AMgroup pair (PfP vs. sfp, SfS vs. pfs, FpF vs. spf, SpS vs. fps, FsF vs. psf, and PsP vs. fsp) while including vial as a random model effect.

In all genotypes, a small bump in mortality was observed in the first 3 days of life. We attribute this bump to stress incurred from anesthetizing flies just after eclosion to separate them by sex and place them into their initial vials. This initial handling stress well exceeded the stress incurred every 7 days to change vials. Considering that this mortality was likely unassociated with the experimental design, we removed these flies from the analysis ( < 2.5% of data; removal had no effect on the overall result patterns). Unless otherwise noted, all analyses were conducted in R 4.4.1.

Results

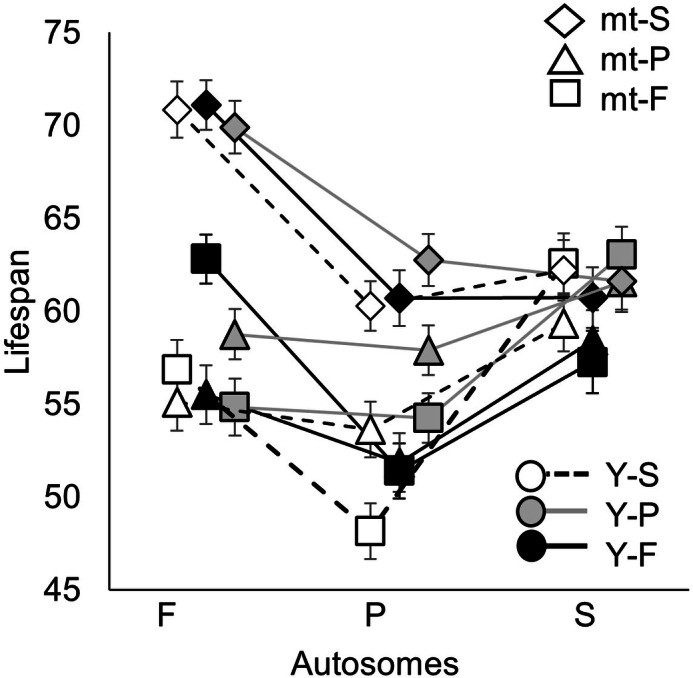

In total, 5271 males were assessed for lifespan across 27 genotypes, with an average of 195 flies per genotype, split among on average 8 vials per genotype. The average lifespan among all flies was 59.6 ± 0.5 days (mean ± 95% CI). All genetic elements and their interactions had a significant impact on lifespan except the Y-by-mitochondria interaction (Table 2). Note that this analysis included all 5 treatments (YAM, yAM, YaM, YAm, and yam). Phenotypic differences among genetic element variants (e.g. mitochondrial variants) are apparent when the other genetic elements are held constant, indicating that the variants within the Y-chromosomes, autosomes, and mitochondria used in our experiments were genetically diverged from each other. For example, FFF, FFp, and FFs (leftmost black genotypes, Fig. 2) only vary in their mitochondria and all induced different lifespan phenotypes (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Impact of the genetic elements on lifespan.

| Source | SS | MS | df | dfDen | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | 2188 | 1093.9 | 2 | 168.4 | 2.94 | 0.0558 |

| A | 20746 | 10373.2 | 2 | 168.4 | 27.84 | <0.0001 |

| M | 52903 | 26451.5 | 2 | 168.5 | 71.00 | <0.0001 |

| Y*A | 7052 | 1763.0 | 4 | 168.3 | 4.73 | 0.0012 |

| Y*M | 2381 | 595.2 | 4 | 168.4 | 1.60 | 0.1772 |

| A*M | 24648 | 6161.9 | 4 | 168.3 | 16.54 | <0.0001 |

| Y*A*M | 8161 | 1020.1 | 8 | 168.2 | 2.74 | 0.0073 |

Note: vial was a random model factor (vial variance component = 1.68%, Wald p-value = 0.0097).

Fig. 2. The impact of Y-chromosome, autosome, and mitochondrial variation on lifespan.

Genotype lifespans represent LS means ± SE.

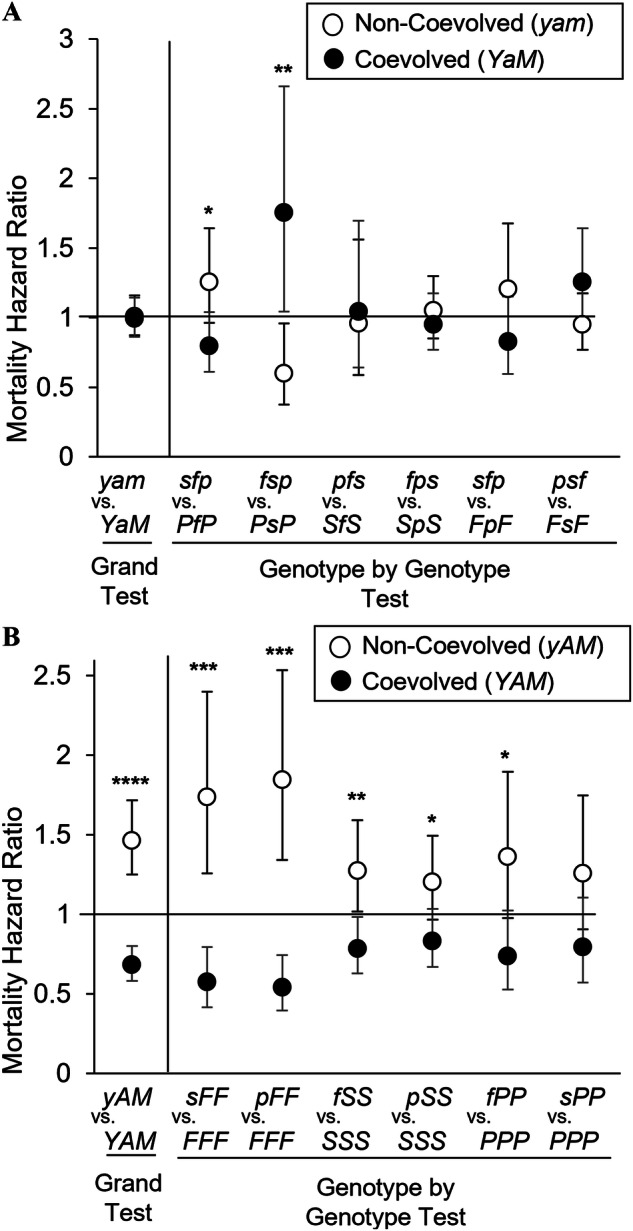

The first test of the Y-compensation hypothesis compared the hazard ratio of the coevolved treatment (YaM), which possessed Y and mitochondrial chromosomes from the same origin population imbedded in a non-coevolved autosomal background, to the non-coevolved treatment (yam), which possessed no coevolved genetic elements. This experimental design represents that of previous works. The grand test of the hypothesis included all YaM and yam genotypes into a single model and showed no difference between the treatments (Table 3A; Fig. 3A). A genotype-by-genotype comparison (within the same autosome-mitochondrial pair) also showed no consistent differences between the treatments (Table 3A; Fig. 3A). Both the grand test and genotype-by-genotype tests are not consistent with Y-compensation, as those with coevolved Y-chromosome and mitochondrial pairs did not exhibit a lower (or different) hazard ratio than those with non-coevolved pairs.

Table 3.

Effect of treatment (coevolved vs non-coevolved) on lifespan.

| A. YaM vs. yam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | df | z | p-value | test |

| Treatment | 1 | −0.1 | 0.92 | YaM ≠ yama |

| Treatment | 1 | −1.11 | 0.27 | PfP ≠ sfp |

| Treatment | 1 | 0.17 | 0.87 | PsP ≠ fsp |

| Treatment | 1 | −1.67 | 0.095 | SfS ≠ pfs |

| Treatment | 1 | −0.46 | 0.65 | SpS ≠ fps |

| Treatment | 1 | 2.35 | 0.019 | FpF ≠ spf |

| Treatment | 1 | −0.5 | 0.62 | FsF ≠ psf |

| B. YAM vs. yAM | ||||

| Source | df | z | p-value | test |

| Treatment | 1 | −4.7 | <0.0001 | YAM ≠ yAMa |

| Treatment | 1 | −3.4 | 0.0008 | FFF ≠ sFF |

| Treatment | 1 | −3.8 | 0.0002 | FFF ≠ pFF |

| Treatment | 1 | −2.1 | 0.035 | SSS ≠ fSS |

| Treatment | 1 | −1.7 | 0.098 | SSS ≠ pSS |

| Treatment | 1 | −1.8 | 0.069 | PPP ≠ fPP |

| Treatment | 1 | −1.4 | 0.17 | PPP ≠ sPP |

A. Results based on the experimental design of previous works. B. Results based on our novel approach. In the grand tests, the autosome-mitochondria group was included as a random factor. Vial was a random factor in all models.

aGrand test of the hypothesis.

Fig. 3. Effect of coevolutionary history among genetic elements on the potential to detect Y-compensation of mother’s curse.

A The grand test of the hypothesis showed no difference in mortality hazard between the coevolved (YaM) and nonevolved (yam) genotypes. When examined at the genotype level, a mixed pattern of risk emerged, which some yam genotypes exhibiting a lower risk than YaM genotypes. B In contrast, the grand test of the hypothesis for the novel approach showed the YAM genotype exhibited a significantly lower mortality risk than the yAM genotype. At the genotype level, a similar pattern was observed among YAM genotypes. For both figures, genotypes appear on the X-axis with the genotype’s hazard ratio and 95% CIs on the Y-axis. A risk ratio of 1 indicates no difference between genotypes in the probability of dying, while a risk ratio greater than 1 indicates a greater risk of dying. “****” = p < 0.0001, “***” = p < 0.001, “**” = p < 0.05, and “*” = p < 0.1.

The second and novel test of the Y-compensation hypothesis compared the coevolved treatment (YAM), which possessed all genetic elements coevolved, to the non-coevolved treatment (yAM), which had autosomal-mitochondrial pairs from the same population but a Y-chromosome from a different population. The novel aspect of this design was that Y-chromosomes in the experimental group were the only non-coevolved element in the test thereby avoiding the aforementioned caveats. The grand test of the hypothesis (all YAM and yAM genotypes included in a single model) showed that the coevolved treatment (YAM) exhibited a significantly lower hazard ratio than the non-coevolved treatment (yAM). Specifically, the non-coevolved treatment exhibited a 50% greater risk of dying early compared with the coevolved treatment. This pattern was also true for the genotype-by-genotype comparisons (Table 3B; Fig. 3B); though some autosomal-mitochondrial pairs exhibited a greater risk than others (e.g. -FF versus -SS). Thus, those individuals that possessed a non-coevolved Y-chromosome had a greater likelihood of dying early compared with those that possessed coevolved elements.

The above patterns are consistent with Y-compensation for mother’s curse, either through direct Y-mitochondria interactions or Y-autosome interactions. These patterns are also consistent with the disruption of Y-autosome coadaptation independent of mother’s curse mutations (a non-mutually exclusive hypothesis; caveat 5 in the introduction). To assess the potential impact of Y-autosome disruption on our results, we examined mortality risk between the YAm and yam genotypes where Y-chromosomes and mitochondria were held constant within comparisons (e.g. FFS versus FPS). If no difference in mortality risk existed, then our results were most likely due to Y-compensation. However, if YAm exhibited a consistently lower risk, then the disruption of Y-autosome coadaptation likely contributed to our results. This post-hoc analysis showed no overall significant difference in mortality risk between the YAm and yam genotypes (hazard ratio = 0.88 + 0.1, z = −1.2, P = 0.23; see Supplementary Table 2), suggesting our results were more likely due to Y-compensation. However, the post-hoc YAm versus yam comparison suffers from the same caveats listed in the introduction (especially caveat 4) and should therefore be regarded with caution.

Discussion

Mitochondria possess a high mutation rate, small effective population size, no recombination, and strict maternal inheritance, allowing deleterious mutations that affect males to accumulate (Dowling et al. 2008; Ballard and Rand 2005; Lynch 1997). Compensatory mutations are expected to evolve in the nuclear genome, and there is growing evidence that the mutational load compensated for by the nuclear genome is significant (Burton et al. 2013; Ellison and Burton 2006; Wolff et al. 2014). Nonetheless, mother’s curse mutations present a unique evolutionary challenge as maternal inheritance of the mitochondria renders direct selection against the mutations powerless. Further, male-biased mutations that have a slight female benefit could not be compensated for by mutations on the autosomes, as they would be selected against when in a female background. Y-chromosomes represent an ideal location to harbor these compensatory mutations because of their strict paternal inheritance. However, recent work has been unable to detect their existence (Aw et al. 2017; Dean et al. 2015; Yee et al. 2015). The data presented here are consistent with Y-compensation for deleterious mitochondrial mutations. Specifically, we show that males with coevolved Y-chromosomes, mitochondria, and autosomes exhibited a lower risk of mortality compared with males possessing a non-coevolved Y. Further, results utilizing non-coevolved autosomes as in previous works provided mixed results, due most likely to unpredictable interactions among the genetic elements (Fig. 3). These data add a new dimension to our understanding of how Y-chromosomes can shape the adaptive evolution of complex traits.

Traditionally, Y-chromosomes were not expected to influence the adaptive evolution of complex traits as they are gene poor masses of heterochromatic DNA that decay over evolutionary time; having been entirely lost in some species (Brown et al. 2020; Burgoyne 1998; Carvalho et al. 2009; Castillo et al. 2010). But a renaissance in how we view the Y-chromosome is underway. Recent evidence indicates that abundant, Y-linked variation can exist within populations (Chippindale and Rice 2001; Kutch and Fedorka 2015) and this variation can impact male genome transcription within populations (Kutch and Fedorka 2015). The Y’s regulatory impact likely stems from its ability to appropriate heterochromatin structural components from elsewhere in the genome, which remodulates euchromatin – heterochromatin boundaries and alters gene transcription (Brown et al. 2020). But to adaptively respond to the selective pressure induced by mother’s curse mutations, Y-linked variation must be additive. Contrary to previous theoretical and empirical work (Chippindale and Rice 2001; Clark 1987; Kutch and Fedorka 2017, 2018), recent data suggests that Y-linked additive variation can and does exist (Kaufmann et al. 2021; Nielsen et al. 2023). This observation, coupled with the support for Y-compensation in this work, indicates that Y-chromosomes may be potent agents of adaptive evolution.

Our results further highlight the importance of using appropriate genetic backgrounds when assessing the fitness effects of various genotypes. This is well exemplified by previous work addressing the effect of mitochondrial-autosomal interactions on lifespan using D. melanogaster (Camus et al. 2020; Loewen and Ganetzky 2018). For instance, Clancy (2008) showed that small mitochondrial mutations can have a large impact on the onset and rate of aging. Further, the direction and magnitude of these effects were significantly modified by the nuclear background in which the mitochondria were placed. This is not surprising, given the prevalence of epistasis in the genome and its potential impact on fitness and evolutionary trajectories (Chippindale and Rice 2001; Wolf et al. 2000; Kutch and Fedorka 2018).

The Y-compensation tests employed here and elsewhere hold three important assumptions. First, laboratory-assessed phenotypes reflect organismal fitness in wild populations. Second, mother’s curse mutations affect male lifespan. Third, Y-compensation is not conflated with Y-autosomal coadaptation. Regarding the first assumption, long lived flies may not necessarily be more fit, especially in populations that experience strong selection for early reproduction resulting in truncated lifespans. Therefore, our conclusions are limited by the degree to which greater lifespan translates into improved organismal fitness. Considering the classic life history trade-off between reproduction and longevity, and the observation that mother’s curse also affects fertility, it would have been of interest to determine if the yAM genotypes who exhibited reduced longevity also exhibited improved reproductive success (compared with YAM males). However, these data were not collected. Regarding the second assumption, previous work in D. melanogaster has provided compelling evidence that male lifespan suffers mother’s curse (Camus et al. 2012; Aw et al. 2017). Our results rely on these previous works as we did not assess female lifespan here. Regarding the last assumption, Y-chromosomes clearly alter autosomal gene regulation (Lemos et al. 2010), some of which may shape male phenotypes independent of mitochondrial mutations (Nielsen et al. 2023). Thus, our results may be due in part (or entirely) to the disruption of Y-autosome coadaptation. Although our post-hoc assessment of YAm versus yam genotypes exhibited no consistent effect on mortality risk in support of the Y-compensation hypothesis, the assessment likely suffers from numerous caveats that limit its reliability. Moving forward, future work should move beyond the holistic phenotype approach (and limiting caveats) and identify specific interacting Y-chromosome and mitochondrial mutations.

In summary, previous work addressing Y-compensation of mother’s curse that used non-coevolved autosomes were likely limited in their ability to detect Y-compensation. Our current experimental design minimizes this limitation and provides results consistent with Y-compensation, revitalizing this hypothesis. It is important to note that our results are also consistent with the disruption of Y-chromosome-autosome coadaptation. Although these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, future work should attempt to disentangle them. Specifically, studies should work to identify specific molecular mechanisms underlying curse and compensation. Understanding the extent of Y-compensation is important, as it improves our understanding of genome function and evolution. Further, numerous medical, agricultural, conservation efforts rely on introducing Y-chromosomes into novel genetic backgrounds. If Y-compensation or Y-autosome coadaptation is extensive, such actions could disrupt male fitness and/or inadvertently unleash mother’s curse.

Data archiving

Data are available at Dryad (10.5061/dryad.59zw3r2ht).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin Cedeno, Saara Rasool, Mariam Sleem, Karishma Santdasani, Connor McDonnald, Naiomy Gonzalez Carrero, Sean Farris, Austin Barger, Katie Fleming, Camille Reynolds-Levy, Natalia Rodriguez, Naomi Baumeler, Shane Rampersaud, and Rachel Inskeep for assistance with sample processing.

Author contributions

The study was conceived and designed by KMF and TMN, data collection was overseen by TMN, JB and MD, data analysis was conducted by KMF, and the manuscript was authored by KMF and TMN.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The work reported in this study was conducted on an invertebrate species that required no research ethics approval or oversight.

Footnotes

Associate editor: Aurora Ruiz-Herrera.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41437-024-00726-w.

References

- Ågren JA, Munasinghe M, Clark AG (2019) Sexual conflict through mother’s curse and father’s curse. Theor Popul Biol 129:9–17. 10.1016/j.tpb.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ågren JA, Munasinghe M, Clark AG (2020) Mitochondrial-Y chromosome epistasis in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Royal Soc B: Biol Sci 287(1937):20200469. 10.1098/rspb.2020.0469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw WC, Garvin MR, Melvin RG, Ballard JWO (2017) Sex-specific influences of mtDNA mitotype and diet on mitochondrial functions and physiological traits in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 12(11):e0187554. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JWO, Rand DM(2005) The population biology of mitochondrial DNA and its phylogenetic implications. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36:621–642 [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Nguyen AH, Bachtrog D (2020) The Drosophila Y chromosome affects heterochromatin integrity genome-wide. Mol Biol Evol 37(10):2808–2824. 10.1093/molbev/msaa082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne PS (1998) The mammalian Y chromosome: a new perspective. Bioassays 20(5):363–366. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199805)20:5<363::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton, RS, Pereira, RJ, & Barreto, FS (2013). Cytonuclear genomic interactions and hybrid breakdown. In DJ Futuyma (Ed.), Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, VOL 44 (Vol. 44, pp. 281–302). Ann Rev. 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135758

- Camus MF, Clancy DJ, Dowling DK (2012) Mitochondria, maternal inheritance, and male aging. Curr Biol 22(18):1717–1721. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus MF, O’Leary M, Reuter M, Lane N (2020) Impact of mitonuclear interactions on life-history responses to diet. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 375(1790):20190416. 10.1098/rstb.2019.0416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AB, Koerich LB, Clark AG (2009) Origin and evolution of Y chromosomes: drosophila tales. Trends Genet 25(6):270–277. 10.1016/j.tig.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo ERD, Bidau CJ, Marti DA (2010) Neo-sex chromosome diversity in Neotropical melanopline grasshoppers (Melanoplinae, Acrididae). Genetica 138(7):775–786. 10.1007/s10709-010-9458-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chippindale AK, Rice WR (2001) Y chromosome polymorphism is a strong determinant of male fitness in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98(10):5677–5682. 10.1073/pnas.101456898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy DJ (2008) Variation in mitochondrial genotype has substantial lifespan effects which may be modulated by nuclear background. Aging Cell 7(6):795–804. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy DJ, Hime GR, Shirras AD (2011) Cytoplasmic male sterility in Drosophila melanogaster associated with a mitochondrial CYTB variant. Heredity 107(4):374–376. 10.1038/hdy.2011.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG (1987) Natural selection and Y-linked polymorphism. Genetics 115(3):569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J (1998) Mitochondrial DNA in mammalian reproduction. Rev Reprod 3(3):172–182. 10.1530/revreprod/3.3.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R, Lemos B, Dowling DK (2015) Context-dependent effects of Y chromosome and mitochondrial haplotype on male locomotive activity in Drosophila melanogaster.J Evol Biol 28(10):1861–1871. 10.1111/jeb.12702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK, Nowostawski AL, Arnqvist G (2007) Effects of cytoplasmic genes on sperm viability and sperm morphology in a seed beetle: implications for sperm competition theory? J Evolut Biol 20(1):358–368. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DK, Friberg U, Lindell J (2008) Evolutionary implications of non-neutral mitochondrial genetic variation. Trends Ecol Evol 23(10):546–554. 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CK, Burton RS (2006) Disruption of mitochondrial function in interpopulation hybrids of Tigriopus californicus. Evolution 60(7):1382–1391. 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01217.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA, Hurst LD (1996) Mitochondria and male disease. Nature 383(6597):224–224. 10.1038/383224a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froman DP, Kirby JD (2005) Sperm mobility: phenotype in roosters (Gallus domesticus) determined by mitochondrial function. Biol Reprod 72(3):562–567. 10.1095/biolreprod.104.035113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell NJ, Metcalf VJ, Allendorf FW (2004) Mother’s curse: the effect of mtDNA on individual fitness and population viability. Trends Ecol Evol 19(5):238–244. 10.1016/j.tree.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick, PW (2012). Reversing mother’s curse revisited. In Evolution (Vol. 66, Issue 2, pp. 612–616). 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01465.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holyoake AJ, McHugh P, Wu M, O’Carroll S, Benny P, Sin IL, Sin FYT (2001) High incidence of single nucleotide substitutions in the mitochondrial genome is associated with poor semen parameters in men. Int J Androl 24(3):175–182. 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2001.00292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti P, Morrow EH, Dowling DK (2011) Experimental evidence supports a sex-specific selective sieve in mitochondrial genome evolution. Science 332(6031):845–848. 10.1126/science.1201157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John JC, Jokhi RP, Barratt CLR (2005) The impact of mitochondrial genetics on male infertility. Int J Androl 28(2):65–73. 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao SH, Chao HT, Wei YH (1995) Mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic-acid 4977-BP deletion is associated with diminished fertility and motility of human sperm. Biol Reprod 52(4):729–736. 10.1095/biolreprod52.4.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman TC (2017) A short history and description of Drosophila melanogaster classical genetics: chromosome aberrations, forward genetic screens, and the nature of mutations. Genetics 206(2):665–689. 10.1534/genetics.117.199950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Wolak ME, Husby A, Immonen E (2021) Rapid evolution of sexual size dimorphism facilitated by Y-linked genetic variance. Nat Ecol Evol 5(10):1394. 10.1038/s41559-021-01530-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaney TA, Wong HWS, Dowling DK, Jones TM, Holman L (2020) Mother’s curse and indirect genetic effects: do males matter to mitochondrial genome evolution? J Evolut Biol 33(2):189–201. 10.1111/jeb.13561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijper B, Lane N, Pomiankowski A (2015) Can paternal leakage maintain sexually antagonistic polymorphism in the cytoplasm? J Evolut Biol 28(2):468–480. 10.1111/jeb.12582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutch IC, Fedorka KM (2017) A test for Y-linked additive and epistatic effects on surviving bacterial infections in Drosophila melanogaster. J Evolut Biol 30(7):1400–1408. 10.1111/jeb.13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutch IC, Fedorka KM (2015) Y-linked variation for autosomal immune gene regulation has the potential to shape sexually dimorphic immunity. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci 282 (1820). 10.1098/rspb.2015.1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kutch IC, Fedorka KM (2018) Y-chromosomes can constrain adaptive evolution via epistatic interactions with other chromosomes. BMC Evolut Biol 18. 10.1186/s12862-018-1327-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leeflang HL, Van Dongen S, Helsen P (2022) Mother’s curse on conservation: assessing the role of mtDNA in sex‐specific survival differences in ex‐situ breeding programs. Anim Conserv 25(3):342–351. 10.1111/acv.12740 [Google Scholar]

- Lemos B, Branco AT, Hartl DL (2010) Epigenetic effects of polymorphic Y chromosomes modulate chromatin components, immune response, and sexual conflict. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107(36):15826–15831. 10.1073/pnas.1010383107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CA, Ganetzky B (2018) Mito-nuclear interactions affecting lifespan and neurodegeneration in a drosophila model of Leigh syndrome. Genetics 208(4):1535–1552. 10.1534/genetics.118.300818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M (1997) Mutation accumulation in nuclear, organelle, and prokaryotic transfer RNA genes. Mol Biol Evolut 14(9):914–925. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milot E, Moreau C, Gagnon A, Cohen AlanA, Brais B, Labuda D (2017) Mother’s curse neutralizes natural selection against a human genetic disease over three centuries. Nat Ecol Evolut 1(9):1400–1406. 10.1038/s41559-017-0276-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen TM, Baldwin J, Fedorka KM (2023) Gene-poor Y-chromosomes substantially impact male trait heritabilities and may help shape sexually dimorphic evolution. Heredity 130(4):236–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Miriyala GK, Littleton AJ, Yang H, Trinh K, Young JM, Kennedy SR, Yamashita YM, Pallanck LJ, Malik HS (2016) A mitochondrial DNA hypomorph of cytochrome oxidase specifically impairs male fertility in Drosophila melanogaster. ELife, 5(AUGUST). 10.7554/eLife.16923.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt K, Dowling DK, Morrow EH (2013) Mitochondrial replacement, evolution, and the clinic. Science 341(6152):1345–1346. 10.1126/science.1237146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogell B, Dean R, Lemos B, Dowling DK (2014) Mito-nuclear interactions as drivers of gene movement on and off the X-chromosomes. BMC Genomics 15:330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Pesini E, Lapena AC, Diez C, Alvarez E, Enriquez J, Lopez-Perez MJ (2000a) Seminal quality correlates with mitochondrial functionality. Clin Chim Acta 300(1–2):97–105. 10.1016/S0009-8981(00)00305-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Pesini E, Lapena AC, Diez-Sanchez C, Perez-Martos A, Montoya J, Alvarez E et al. (2000b) Human mtDNA haplogroups associated with high or reduced spermatozoa motility. Am J Hum Genet 67(3):682–696. 10.1086/303040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Turbill C, Suchentrunk F (2010) Introducing mother’s curse: low male fertility associated with an imported mtDNA haplotype in a captive colony of brown hares. Mol Ecol 19(1):36–43. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04444.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unckless RL, Herren JK (2009) Population genetics of sexually antagonistic mitochondrial mutants under inbreeding. J Theor Biol 260(1):132–136. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ, Brandvain Y (2009) Reversing mother’s curse: selection on male mitochondrial fitness effects. Evolution 63(4):1084–1089. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00614.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf JB, Brodie ED, Wade MJ (2000) Epistasis and the Evolutionary Process. Oxford University Press

- Wolff JN, Ladoukakis ED, Enríquez JA, Dowling DK (2014) Mitonuclear interactions: evolutionary consequences over multiple biological scales. In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (Vol. 369, Issue 1646). Royal Society of London. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yee WK, Rogell B, Lemos B, Dowling DK (2015) Intergenomic interactions between mitochondrial and Y-linked genes shape male mating patterns and fertility in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 69(11):2876–2890. 10.1111/evo.12788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee WKW, Sutton KL, Dowling DK (2013) In vivo male fertility is affected by naturally occurring mitochondrial haplotypes. In Current Biology (Vol. 23, Issue 2). 10.1016/j.cub.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at Dryad (10.5061/dryad.59zw3r2ht).