Abstract

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are obtained intermediate from nonenzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids and it’s associated with diabetic complications. Today, potassium sorbate (PS), sodium citrate (CIT) and sodium benzoate (SB) were widespread used as food preservatives that can easily enter biological matrices. Here, the interaction between glycosylation Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and food preservatives individually and combination of two and three was studied by biochemical and simulation analysis. The results revealed that an increase in absorption and fluorescent intensity in all treated groups. The most carbonyl and glycosylated compounds were observed in the treatment with PS and its combined groups with two preservatives. Treatment with three preservatives alone or combination caused a significant increase in red blood cell hemolysis and MDA level (p < 0.05). The results of the in vitro experiments were in line with the docking studies and the interaction of the compounds with albumin was observed in important subdomain of BSA that show the stability of the BSA-ligand complex. Simultaneous treatment and the combination of two or three food preservatives cause their synergistic effect in possible harm to the body. In addition, the molecular docking experiment suggests that Sodium Benzoate, Potassium Sorbate and Sodium Dihydrogen Citrate can interact with BSA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-80642-5.

Keywords: BSA. Glycation. Sodium benzoate, Potassium sorbate, Citrate, Simulation

Subject terms: Chemical biology, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Structural biology

Introduction

Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs) are formed through the Maillard reaction, which occurs when reducing sugars non-enzymatically interact with the amino groups of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. This process involves a series of reactions that create a Schiff base, followed by an Amadori rearrangement and subsequent oxidative modifications. The glycation process is intricate and gradual, influenced by the availability of substrates, and leads to spontaneous damage to proteins within physiological systems1.

The primary concern regarding the harmful effects of AGEs lies in their capacity to cause irreversible damage to the structural and functional integrity of proteins through both intermolecular and intramolecular crosslinking. This covalent cross-linking results in the deactivation of biologically active proteins and enzymes, rendering them resistant to proteolytic digestion, creating catalytic sites for reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, triggering pro-inflammatory responses, disrupting intracellular signaling, and contributing to various metabolic and biochemical disturbances. Recent research has highlighted the significant roles of AGEs in the mechanisms underlying the progression of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, liver fibrosis, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, chronic inflammation, and other persistent health conditions1,2.

Numerous environmental factors, such as cigarette smoke, diets high in refined and simple carbohydrates, foods cooked at elevated temperatures, promote the production of AGEs, thereby inflicting damage on cellular lipids and proteins3. Given the prevalent use of additives in food, pharmaceuticals, and health products, the potential for their entry into human biological systems raises valid concerns. This study primarily aimed to investigate the interference of food preservatives with the Maillard reaction and its implications for the formation of abnormal structures in albumin protein. Chemical additives such as potassium sorbate (PS), sodium benzoate (SB) and disodium hydrogen citrate (CIT) are widely used in food and cosmetic products due to their bacteriostatic and antifungal effects. PS is the potassium salt of sorbic acid, denoted by its molecular formula C6H7KO2, which is commonly used in the food industry. The production of PS involves the synthetic reaction between sorbic acid and potassium hydroxide, or a two-step process utilizing the condensation of crotonaldehyde and ketene. This particular compound exhibits low solubility in ethanol and acetone, but readily dissolves in water and chloroform while remaining insoluble in benzene. Furthermore, the solubility of PS is influenced by the temperature of the water in which it is dissolved. Potassium sorbate, with a natural pH of 4.5, is used as a bacteriostatic and fungicidal agent in food products such as meat, bread, margarine, beverages, sauces, and sweets, and it prevents the growth of mold, prevents spoilage, and preserves the freshness of products. It becomes food. Who has set the permissible limit of potassium sorbate in food at 0–25 mg/kg per day4,5.

SB (NaC7H5O2) is the sodium derivative of benzoic acid, and its synthesis involves the chemical reaction between sodium hydroxide and benzoic acid. This compound is derived from benzene, wherein one hydrogen atom is replaced by an alkyl group. In terms of solubility, it exhibits solubility in liquid ammonia, pyridine, and ethanol, while its dissolution in water is highly pronounced. [4] Recent studies have shown that sodium benzoate can bind to DNA and play a role in the binding process with hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds. Among the side effects of sodium benzoate are the reduction of carnitine due to the increase in the excretion of benzoylcarnitine, the reduction of leptin secretion and the development He mentioned obesity. Sodium benzoate can cause a significant increase in the activity of gluconeogenesis and, as a result, an increase in blood glucose levels. An increase in glucose also causes glycation and peroxidation reactions of membrane lipids. The ADI limit of daily SB consumption is 0–5 mg/kg/day6.

Citrate is used as a preservative in all kinds of drinks. Although regulatory agencies consider citrate to be a safe food additive, there is ample evidence that the compound may actually interfere with the body’s energy homeostasis and physiology. Previous studies have shown that citrate increases insulin resistance and inflammation of adipose tissue in mice and may play a role as one of the factors of human obesity and related diseases7,8. Citrate-induced nephrotoxic effects have also been reported in mice9.

These compounds are known to be safe in the short term, but their biological effects and possible risks for the human body are not yet known. The binding mechanisms between the molecules of preservative compounds and types of albumins, such as human and bovine albumin, and the risk to human health have recently attracted the attention of researchers. Considering that the reactions between albumin and different chemicals introduced into the body can significantly affect their absorption, distribution, metabolism and toxicity, therefore, it seems necessary to investigate and study these effects10.

In addition, the secondary structure of BSA can be innovate upon interaction with small molecules, so to further understand and explanation of the biological findings, molecular docking and simulation studies was applied. Molecular modeling have significant role in predict the binding properties in the active site of protein and DNA. Molecular dynamic (MD) simulations complement docking by enabling the dynamic assessment of ligand stability within the binding pocket over a certain time. The structural flexibility, conformational changes, and stability of binding interactions were observed through MD simulation. These insights are essential for understanding the potential efficacy and selectivity of the compounds under study.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the effects and interactions of these compounds separately and simultaneously on serum albumin under hyperglycemic conditions in vitro. Also, in this study, the method of binding and the degree of interaction of the investigated additives in the active site of BSA (Bovin Serum Albumin) protein will be done with the help of molecular docking and simulation methods.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All of the chemicals utilized in this study were procured from Sigma-Aldrich and the Merck Company (Darmstadt, Germany).

Bovine serum albumin glycation model

The glycation reaction was done according to previously established, but with minor modifications11,12. The BSA (10 mg/mL) was solubilized in phosphate buffer solution (PBS, 50 mM, pH 7.4) and subjected to incubation alongside glucose (100 mg/mL) within a, supplemented with sodium azide (0.02%). According to the mentioned treated groups, we added 10 mg/ml of preservatives to each tube, a concentration that below the toxic level in plasma13. Based on pilot studies, all tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 3 weeks. BSA, BSA + GLU, BSA + GLU + SB, BSA + GLU + PS, BSA + GLU + CIT, BSA + GLU + PS + SB, BSA + GLU + SB + CIT, BSA + GLU + PS + CIT, BSA + GLU + PS + SB + CIT.

Spectrophotometric evaluation of absorption changes

After the end of the incubation time and normalizing the protein concentration, the absorption spectrum of all groups was measured with a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 200–400 nm and compared. Spectroscopic analysis can be employed to examine the alterations in the structure of albumin and to study the formation of albumin and ligand complexes. The strong absorption peak of serum albumin at approximately 280 nm is indicative of the primary structure of the albumin4.

Fluorescent measurement

The process of glycation results in the creation of fluorescent AGEs. As a result, these substances can be quantified using an excitation wavelength at 360 nm and an emission wavelength at 460 nm. The measurement of fluorescence was conducted using a Synergy H4 microplate reader (Bio Tek, UK). The fluorescent intensity were reported14.

Protein carbonyl contents determination

Narbonyl™ Protein Carbonyl Assay Kit (Navand Salamt, Iran) was used according to manufacture protocol.

Determination of amadori products

Amadori product were determined by reaction between nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT) indicator and ketoamines. For this purpose, 100 µl of the sample with 100 µl of NBT (250 µM/0.1 M carbonate, pH 10.8) were mixed and incubated for 45 min at 37ºc. Then absorption was measured at wavelength of 525 nm.

Total thiol assay

The measurement of thiol concentrations was conducted through the utilization of 5, 5-dithionitrobenzoic acid (DTNB)15. In brief, 200 µl of freshly prepared DTNB in PBS, pH; 8.5 was added to 100 µl of samples. Standard curves were prepared using reduced glutathione. The absorbance was read at wavelength of 420 nm16.

Hemolysis test

Blood samples were obtained from rats in volumes of 3 ml and collected in tubes containing EDTA. Subsequently, 5 ml of phosphate buffer was added. A mixture of 100 µl of diluted blood and 300 µl of samples was incubated at a temperature of 37 °C for a duration of 24 h. The hemoglobin release was assessed by subjecting the sample to centrifugation (3000 g for 10 min) and analyzing the resulting supernatant through photometric analysis at a wavelength of 540 nm. H2O2 used as a positive control17.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) level determination in RBC

The resultant pellets from hemolysis test were subjected to an interaction with thiobarbituric acid and phosphoric acid in a vigorously heated water bath for a period of 45 min. Upon cooling, the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 532 nm18.

Docking study

The molecular docking studies was carried out by AutoDock Tools package (1.5.6) (ADT) (http://mgltools.scripps.edu/) software. The 3-D X-ray crystal structure of BSA (PDB ID: 4F5S) at 2.47Å resolution, were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Databank (http://www.rcsb.org). Before docking, the cognate ligand and water molecules was removed and, missing hydrogen was added to atoms, and finally saved as PDBQT format19,20. The minimization of 3D structures of ligands was done by HyperChem software (Molecular Mechanics MM + and then semiempirical AM1 methods). Finally, PDBQT formats of the ligands were obtained by adding Gasteiger charges and adding the degree of torsions. The docking procedure was performed in a grid box with a size of 75 × 75 × 75 Å with 0.375 grid spacing and a center of x = 3.41, y = 27.983, z = 106.347 using AutoDock (4.2.6) using an in-house batch script (DOCKFACE)21,22. Discovery studio 2017 R2 client (http://accelrys.com) was used to show the interactions of the binding complexes23.

Molecular dynamic simulation

The Gromacs simulation package version 2019.1 was utilized to run molecular dynamic (MD) simulations on the optimal docking configuration of sodium benzoate, potassium sorbate, and disodium hydrogen citrate bound to BSA (PDB code: 4FS5) receptors. Initially, Chimera software was employed to introduce hydrogen atoms and charges into the ligand structure to improve accuracy in calculations and predictions. The ACPYPE program was employed to create topological parameters and determine various atom types, utilizing the Amber99sb Force Field. The dodecahedral box, with a minimum distance of 1.0 nm, was delineated and subsequently filled with TIP3P water molecules. A concentration of 0.15 mol/L sodium chloride (NaCl) was added to the system to achieve neutralization. This addition ensures the balance of charges within the system, maintaining overall electroneutrality. To equilibrate the system, the steepest descent algorithm was run for 100 ps while applying a position constraint to fix the ligand and protein. The NVT equilibration was conducted throughout 500 ps at a temperature of 300 ⁰K. The V-rescale thermostat was employed to regulate the temperature throughout the equilibration process. The NPT equilibration process was conducted at a pressure of 1 atm at 500 ps and MD was run at 100 ns. The long-range electrostatic interaction was computed by the Particle-mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm. After the complication of the run, the RMS, RMSF, Rg, and the total number of hydrogen bonds were analyzed23–25.

Statistical analysis

The data is displayed in the form of mean ± SEM. The calculations were performed using SPSS 16.0 software. An analysis was conducted using a One-way ANOVA and post-test Dunnett’s. The values with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Result

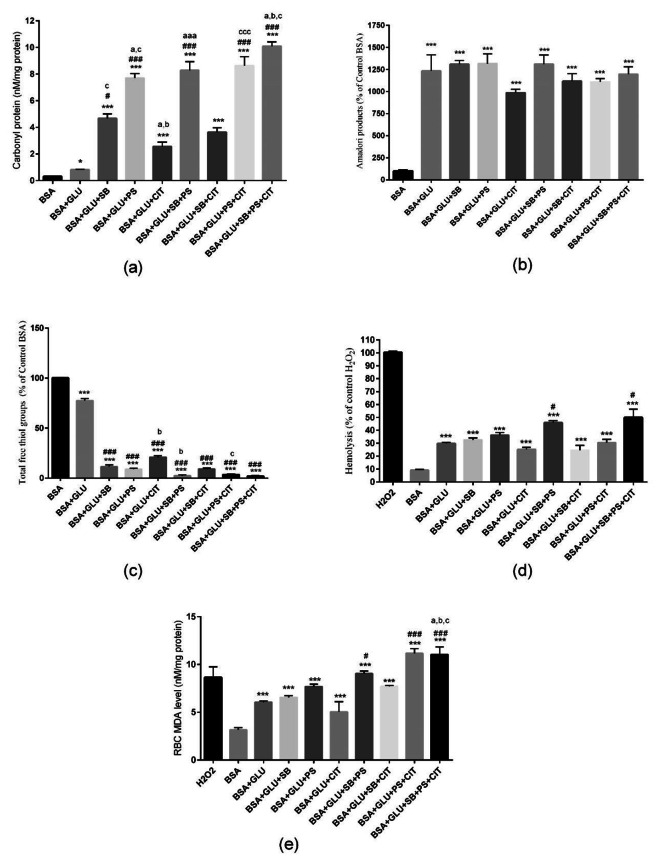

The effect of food preservatives on BSA absorption spectrum

Absorption spectrum scanning was performed in the region of 200–400 nm and the maximum absorption at 280 nm was determined and compared for different groups. As shown in Fig. 1a, with the glycosylation of BSA, the amount of absorption has increased by almost 1.4 times compared to the BSA control group.

Fig. 1.

Effect of food preservatives on glycated BSA, (a) UV-visible spectra, (b) Fluorescence intensity EX: 360 and EM: 460 nm. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). [* Significant difference compared with BSA], # compared with BSA + GLU, a compared with BSA + GLU + SB, b compared with BSA + GLU + PS, c compared with BSA + GLU + CIT. [∗ p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001].

With the presence of SB, the amount of absorption compared to glycosylated BSA did not change. However, the simultaneous treatment of SB and PS significantly increased the absorption rate about 3.3 times compared to glycosylated BSA. But the treatment group BSA + GLU + SB + CIT did not show a significant change to glycosylated albumin (Fig. 1a).

The absorption rate of glycosylated BSA with the presence of PS has been significantly increased by about 5 times. In the simultaneous treatment of BSA + GLU + PS + Cit, the amount of absorption has decreased about 1.2 times compared to PS. Also, about 22 times compared to treatment with CIT alone. Simultaneous treatment with CIT and SB increases the absorption about 7 times compared to CIT alone. In all groups treated with the presence of PS, the highest amount of absorption compared to glycosylated albumin has occurred.

The effect of food preservatives on BSA-derived fluorescence

Figure 1b, showed the treatment of BSA with glucose significantly increased the fluorescent intensity (p < 0.001). In the groups treated with preservatives, the fluorescent intensity increased significantly in the groups treated with PS alone, PS + SB, PS + CIT and PS + SB + CIT in comparison with BSA + GLU group (p < 0.001). In the combined treatment group, the highest amount of fluorescent created belongs to the SB + PS group (p < 0.001). In the triple treatment group, the amount of fluorescent shows a significant increase compared to the SB and CIT groups alone (p < 0.05).

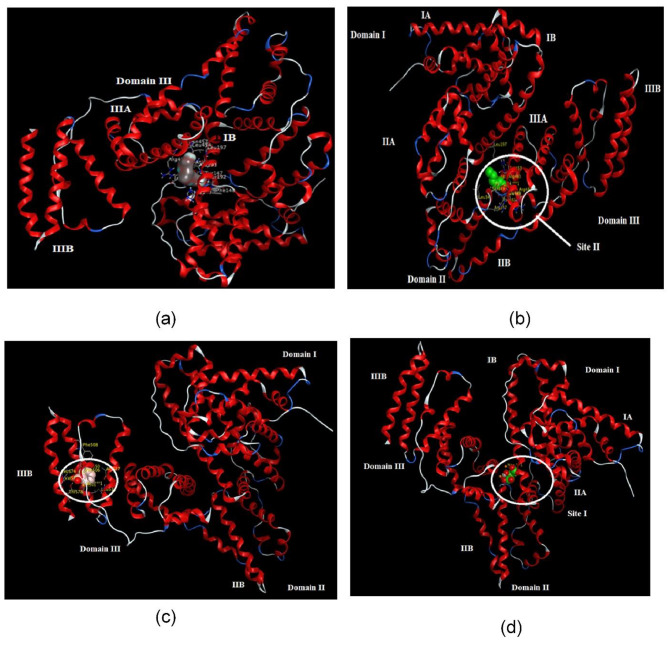

The effect of food preservatives on protein carbonyl contents

It can be seen in Fig. 2, the treatment of BSA with glucose significantly increased the amount of protein carbonylation (p < 0.05). Treatment with each of SB, PS, and CIT alone or in combination increased protein carbonylation compared to BSA + GLU group (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Effect of food preservatives on glycated BSA, (a) carbonyl protein content, (b) Amadori products, (c) Total Thiol groups, (d) Hemolysis, (e) RBC MDA level. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). [* Significant difference compared with BSA], # compared with BSA + GLU, a compared with BSA + GLU + SB, b compared with BSA + GLU + PS, c compared with BSA + GLU + CIT. [∗ p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001].

Treatment with PS significantly increased protein carbonylation rate compared to SB or CIT alone (p < 0.01). The combination of PS + SB and PS + CIT significantly increased protein carbonylation compared to the combination of CIT + SB (p < 0.05).

The effect of food preservatives on production of amadori products

It can be seen in Fig. 2, treating BSA with glucose has significantly increased the production of Amadori products compared to BSA (p < 0.001). But there is no significant difference between the groups treated alone and the double and triple combination of SB, PS and CIT preservatives compared to glycosylated albumin.

The effect of food preservatives on BSA thiol groups

Treatment of BSA with glucose significantly reduces the amount of thiol groups (p < 0.001). Also, treatment with all three preservatives SB, PS and CIT alone or in combination has significantly reduced the amount of thiol groups compared to the glycosylated BSA group (p < 0.001) Fig. 2.

The effect of food preservatives on Hemolysis and lipid peroxidation of red blood cells

Figure 2 demonstrate treating BSA with glucose significantly increased the amount of red blood cell hemolysis ((p < 0.05). The treatment in the combined groups of SB + PS and SB + PS + CIT caused more hemolysis than the control group of glycosylated BSA with a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Treatment with combinations of PS + SB, PS + CIT and PS + CIT + SB significantly increased lipid peroxidation compared to BSA + GLU group (p < 0.001) Fig. 2.

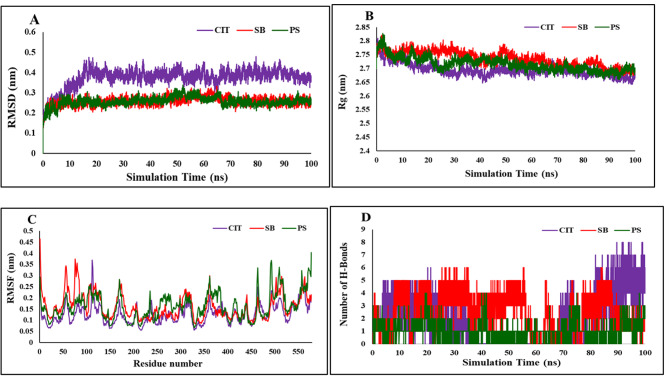

Docking study

In order to complement the observed spectroscopic results and evaluate the binding energies, modes, and sites of the interaction between SB, PS and CIT and BSA (PDB ID: 4FS5), molecular docking technique was used. The binding energy for the BSA – SB, BSA – PS and BSA- CIT complexes was found to be -6.4, -6.5 and − 5.9 kcal mol− 1, respectively which is in accordance with the spectroscopic results.

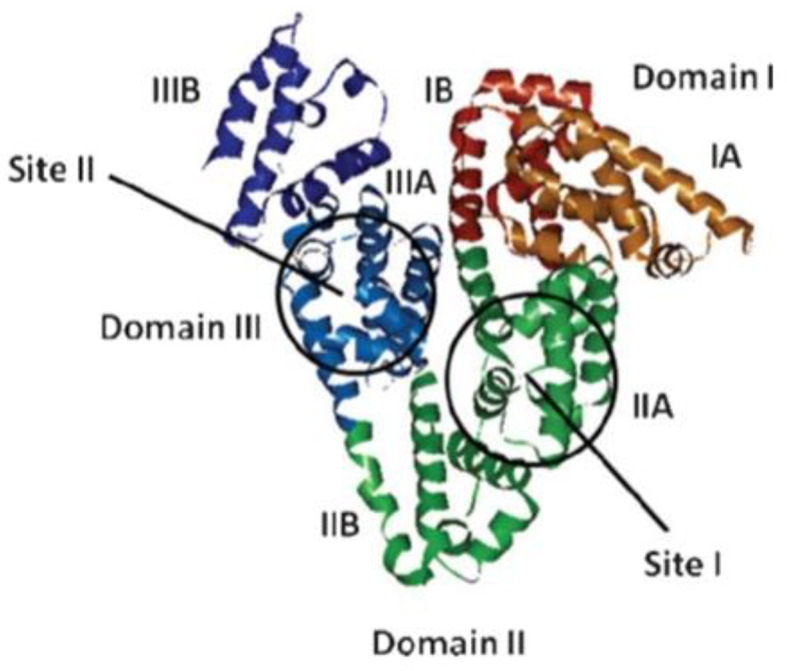

As depicted in Fig. 3, the PS binding in the hydrophobic pockets of the Sudlow site II of BSA proteins contributing stability to the PS -BSA complex. The more binding interaction was found for hydrogen bonding interaction between the amino acid residues like Arg 483, Arg 484 and Ser 343 with carbonyl and oxygen group of PS. On the other hand, negatively charged oxygen formed ionic interaction with Arg 347 which play an important role in stabilizing of the complex, too. The results obtained from molecular docking revealed that hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions as dominant forces involved in the binding between the small molecules and the proteins.

Fig. 3.

(a) The 3D interactions of tri ethylene glycol with BSA active site, (b) The 3D interactions of PS with BSA (PDB: 4FS5), (c) The 3D interactions of SB with BSA (PDB: 4FS5), (d) The 3D interactions of CIT with BSA (PDB: 4FS5). BSA: bovine serum albumin, SB; Sodium benzoate, PS: Potassium sorbate, CIT: Sodium citrate.

The Fig. 3 indicated that SB had close contact interactions with subdomain IIIB. The carbonyl and negatively charged oxygen group bind hydrogen interaction with Val 575 and Thr 578. The docking result reveals the binding of CIT in the hydrophobic region of subdomains IIA (Sudlow site I), and three hydrogen interaction with Ser 453, Arg 194 and Trp 213 was seen (Fig. 3).

Overall, previous research has revealed that BSA has two hydrophobic sites that are responsible for stabilizing the ligands in the active site of the BSA protein. As shown in Fig. 3, the specific binding sites of SB, PS and CIT in the active site of the BSA protein are located in subdomain IIIB, III A, and IIA, respectively. Molecular docking studies have provided valuable information on the interaction between SB, and PS and CIT with the BSA protein, demonstrating the structural stability of their complex4,26.

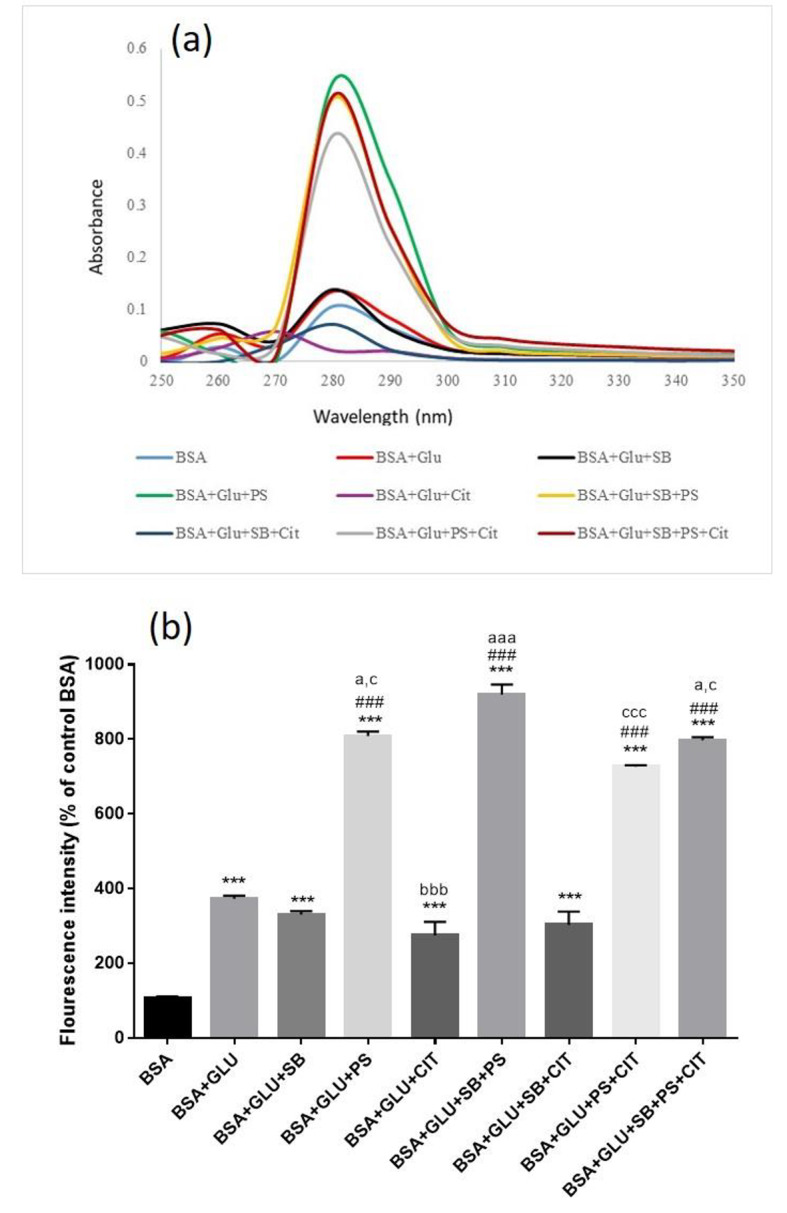

Molecular dynamic simulation analysis

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations need to be performed for a definite period to predict both the structural refinements and stability of ligand-receptor complexes. Graphs concerning Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), the radius of gyration (Rg), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and the total number of hydrogen bonds are analyses commonly employed to predict the affinity between disodium hydrogen citrate (CIT), sodium benzoate (SB), and potassium sorbate (PS) in the active site of (PDB code: 4FS5) receptors (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

a) RMSD of the backbone of protein in complex with CIT, SB, and PS ligands at 100 ns MD simulations, b) The radius of gyration (Rg) over the simulation time for CIT, SB, and PS ligands, c) RMSF values of the backbone of protein over the simulation time d) Total number of H-bond count throughout the simulation time of CIT, SB, and PS ligands with BSA active site.

The RMSD plot of backbone atoms for the protein over the simulation time is illustrated in Fig. 4. The result indicated that CIT, SB, and PS ligands reached the equilibrium phase with minimum fluctuation after 20, 10, and 10 ns with BSA protein from the beginning simulation, respectively. The analysis of RMSD indicated notable stability of the protein in three systems during a 100 nanosecond (ns) simulation. The RMSD evaluation demonstrated that CIT, SB, and PS fitted stable in the active site of BSA protein and three complexes were stable.

Figure 4 illustrates the Rg plots of protein during the whole simulation time. The Rg plots of the protein of each ligand-protein complex show the root mean square distance of every amino acid atom from the protein’s core, the compactness changes, and the flexibility of the protein27. The low average Rg value of CIT, SB, and PS ligands was calculated as 2.69, 2.73, and 2.71 respectively revealing the compactness and flexibility of the protein. The Rg values of CIT, SB, and PS reached a plateau from 30 to 100, 50 to 100, and 30 to 100 ns, indicating greater rigidity, which suggests they are suitable inhibitors for the BSA target.

The RMSF value of the backbone residue of CIT, SB, and PS ligands is depicted in Fig. 4. The RMSF value indicates the degree of compaction of the protein structure and reveals the fluctuations of individual amino acid residues. The RMSF plots displayed a similar distribution and confirmed that there were no changes in the structure of the BSA receptor. The range of RMSF values for the three complexes was calculated to be between 0.07 and 0.37 Å, indicating minimal flexibility among amino acid residues of BSA protein.

The total number of hydrogen bonds between the CIT, SB, PS ligands and BSA receptor was displayed in Fig. 4. Hydrogen bonds are the most important factors in binding affinity between ligands and proteins. The formation of hydrogen bonds exhibited conformational stability, the average number of hydrogen bonds formed by CIT, SB, and PS ligands are 1.83 (range 0–8), 2.55 (range 0–6), and 1.05 (range 0–4).

Discussion

Non-enzymatic glycation is a reaction between carbonyl groups and protein-free amino groups that results in protein carbonylation and formation of oxidation products via the Maillard reaction. The production of important intermediates, including Schiff bases and Amadori products, can lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species. ROS are highly reactive to the destructive structure of biomolecules, cell damage, and cytotoxic agents that play a role in causing oxidative stress in many diseases such as diabetes28.

The presence of some compounds along with sugars can increase the amount of glycosylation of proteins. Food preservatives such as sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate can be mentioned in this category4. The use of food additives, especially preservatives, is inevitable in the food, drug, and cosmetic industry. But due to the expansion of consumption of ready and semi-ready industrial foods and drinks containing additives, there is always concern about their health and safety. Therefore, the simultaneous consumption of food containing any of the preservatives, as well as increasing the consumption of more than the acceptable ADI limit, is not out of mind. In this study, the effect of sodium benzoate, potassium sorbate and citrate alone and their binary and ternary combination on the level of glycosylation of albumin protein in vitro has been investigated.

BSA is a single-chain globular protein composed of 583 amino acid residues that form 17 disulfide bonds. BSA not only has wide biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, but also as a biological ligand model for interaction studies due to its high stability, low cost, binding properties, medical importance, and high structural similarity to human serum albumin approximately 76%29.

In this study, after three weeks of incubation, the absorption spectrum of the tested groups was measured by spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 200–400 nm and it was observed that in the presence of potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate and citrate, the absorption rate increases at 280 nm.

Spectroscopic technique used to investigate the structural changes of BSA and to explore albumin and ligand complex formation. The alteration of absorption peak at around 280 nm reflects the main structure of the albumin was changed. Research has indicated that the absorption peak of albumin is attributed to the π–π* transition of aromatic amino acids such as tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine4. The reducing sugar characteristics of glucose facilitate non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, such as plasma proteins like albumin. The glycation process affects albumin at specific residues like tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine, resulting in conformational changes in the protein structure. The modifications induced by glycation in albumin increase in molecular weight, higher exposure of hydrophobic sites, and a more pronounced chromophore spectrum30. Consequently, this study revealed that the treatment with PS exhibited the greatest level of absorption at 280 nm, indicating potential alterations in protein structure or a significant increase in BSA glycosylation, while the treatment with citrate resulted in the lowest amount of absorption. Supporting these findings, the previous study also stated that the intensity of UV absorption increases with SB, which indicates the formation of a complex between SB and BSA amino acid residues26.

The reason for not observing absorption changes in the treatment with citrate can be due to BSA occupying the same position in the reaction with glucose.

They are the same aromatic amino acids, tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine that contribute to the generation of endogenous fluorescence in proteins. Notably, Tryptophan is pivotal in the intrinsic fluorescence of albumin. Specifically, alterations in the intrinsic fluorescence of albumin occur when small molecules interact with tryptophan residues4. Furthermore, previous studies indicate that the fluorescence intensity of modified human serum albumin in the presence of glucose correlates with AGE production such as Argpyrimidine, Pentosidin, and Vesperlisines10. These compounds, known for their cross-linking, absorption, and fluorescence characteristics, serve as indicators for assessing tissue damage resulting from glycation31.

Our results showed that the highest fluorescent intensity belonged to the BSA treatment with PS. Although SB and CIT also caused an increase in fluorescence, which may indicate changes in protein structure or an increase in glycation of albumin. The Maillard reaction is a chain process that is initiated by strong covalent bonding between compounds containing carbonyl groups, such as glucose, and free amine functional groups like the amino acid lysine. This bonding triggers the formation of other glycation products, which further the process and lead to extensive structural changes in the albumin protein10. The condensation reaction was probably occurred by nucleophilic attack of free amino groups of BSA and the carbonyl group of PS, SB, and CIT similar to glucose. According to the results of the Taghavi et al. study, potassium sorbate can form covalent bonds with Lys residues, thus serving as a catalyst for the Maillard reaction, similar to glucose. The process can be followed by the formation of subsequent products like AGEs10.

In this study, it was observed that treatment with glucose and food preservatives, specifically PS, increases the carbonyl content and decreases thiol groups after three weeks of treatment.

The increase in carbonyl content and decrease in thiol groups is due to changes in the cysteine roots of proteins and as a result of their oxidation. The reactive oxygen species that are created during glycosylation cause the oxidation of amino acids in the chain, leads to the damage of cellular proteins32.

In this research, it was shown that citrate has the lowest production of Amadori products, and sodium benzoate and potassium citrate both create a high level of Amadori products. When Schiff’s bases become more stable, they become Amadori products, which means more damage to cells33.

AGEs possess the ability to cross-react with other proteins, disrupting their structure and functions. The interaction between AGEs and specific receptors (RAGEs), activates the nuclear transcription factor κB, affecting the expression of cytokines inflammatory response genes and causing chronic damage to various tissues in the body31.

Red blood cells are prone to damage caused by oxidative stress because they have a high level of oxygen and hemoglobin and also have a membrane rich in saturated fatty acids. Therefore, carbonyl proteins that induce oxidative stress can damage the membrane of erythrocytes and cause their hemolysis. In this study, it has been shown that PS and SB cause more hemolysis, and increased the level of malodialdehyde, but citrate causes less hemolysis and MDA production than both of them.

Our results showed a significant difference between AGEs formed in glycosylated BSA with potassium sorbate. Not only is PS more potent than SB in producing AGEs, it also produces components of AGEs in different amounts than SB. Therefore, these differences in maximum production of AGEs are induced due to specific chemical structure and different intra- or extra-molecular cross-linking ability.

BSA contains two major specific ligand-binding sites located in the hydrophobic cavities in sub-domains II-A and III-A, which are also known as Sudlow’s site I and Sudlow’s site II, respectively34 (Fig. 5). Meanwhile, previous works have demonstrated that the durability and toxicity of chemicals have huge influence on the structure of BSA because of interaction effect35.

Fig. 5.

The domain and binding site of BSA model structure.

The action mechanism of food preservatives involving BSA is associated with covalent interactions that induce structural alterations in BSA. This process results in the release of various intra or extracellular substances, including AGEs, and oxidative products. The prolonged consumption of food products that contain preservatives, whether taken separately or together, can trigger the AGEs or enhance their production, potentially resulting in chronic health conditions such as diabetes, cancer and obesity.

Conclusion

While the safety of citrate additives in food products is generally accepted, and the daily intake limit has not been determined, this study indicates a potential interaction between citrate and albumin, a protein with a vital role in the body. Considering that the interactions between albumin and various substances introduced into the body can significantly affect their kinetics—such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and toxicity—it is important to take these factors into account. Moreover, the interference of citrate with the Maillard reaction raises alarms about the potential formation of abnormal structures within albumin proteins.

Based on the searches done in the scientific databases, this study for the first time deals with the effect of citrate interaction with albumin macromolecule in vitro and computerized. It was found that sodium citrate, like sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate, can increase the production of glycosylated compounds. On the other hand, this study for the first time examines the effect of simultaneous treatment and the combination of two or three food preservatives and shows the results of their synergistic effect in possible harm to the body. The spectral findings show that the protein structure can changes through the variation in UV absorbance and fluorescence intensity during interaction with three studied food preservative On the other hand, molecular modeling presented that all these compounds forming a stable complex with BSA that can change the BSA protein structure and maybe acts as a primer for the formation of subsequent products in organisms such as AGEs and ROS which confirmed the biological outputs. Due to the increasing and long-term consumption of food preservatives in various products and the possibility of their simultaneous consumption, and occurrence of the mentioned damages, which is the basis of chronic diseases, should be considered. It may be necessary to review the permitted number of additives by regulatory management.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Leila Emami prepare the manuscript, and performed the docking section. Elaheh Khodarahimi contributed to perform biological section. Pegah Mardaneh performed and written the simulation section. Mohammad Javad Khoshnoud edit the manuscript. Marzieh Rashedinia edit the manuscript and supervise the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This investigation was financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: 27083).

Data availability

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. We have presented all data in the form of Figures. The PDB code (4F5S) was retrieved from protein data bank (www. rcsb. org). https:// www. rcsb. org/ structure/ 4F5S.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of live vertebrates were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving live vertebrates were in accordance with ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. Procedures involving live vertebrates and their care were done under the ethical guidelines approved by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. (Ethics code: IR.SUMS.REC.1401.115).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khalid, M., Petroianu, G. & Adem, A. Advanced glycation end products and diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and perspectives. Biomolecules12 (4), 542 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramasamy, R. et al. Advanced glycation end products and RAGE: a common thread in aging, diabetes, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. Glycobiology15 (7), 16R–28R (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perrone, A., Giovino, A., Benny, J. & Martinelli, F. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs): biochemistry, signaling, analytical methods, and epigenetic effects. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev.2020 (1), 3818196 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash, H., Akbari, N., Esazadeh, K. & Dolatabadi, J. E. N. Molecular and technical aspects on the interaction of serum albumin with multifunctional food preservatives. Food Chem.293, 491–498 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dehghan, P., Mohammadi, A., Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash, H. & Dolatabadi, J. E. N. Pharmacokinetic and toxicological aspects of potassium sorbate food additive and its constituents. Trends Food Sci. Technol.80, 123–130 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tawfek, N., Amin, H., Abdalla, A. & Fargali, S. Adverse effects of some food additives in adult male albino rats. Curr. Sci. Int.4 (4), 525–537 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branco, J. R. et al. Dietary citrate acutely induces insulin resistance and markers of liver inflammation in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem.98, 108834 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leandro, J. G. et al. Exogenous citrate impairs glucose tolerance and promotes visceral adipose tissue inflammation in mice. Br. J. Nutr.115 (6), 967–973 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, X., Lv, Q., Liu, Y. & Deng, W. Effects of the food additive, citric acid, on kidney cells of mice. Biotech. Histochem.90 (1), 38–44 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taghavi, F. et al. Potassium sorbate as an AGE activator for human serum albumin in the presence and absence of glucose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.62, 146–154 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, Y., Sun, W. & Zhanga, J. Optimization of preparation and property studies on glycosylated albumin as drug carrier for nanoparticles. Die Pharmazie-An Int. J. Pharm. Sci.66 (7), 484–490 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rashedinia, M. et al. Comparison of Protective Effects of Phenolic Acids on Protein Glycation of BSA Supported by In Vitro and Docking Studies. Biochemistry Research International. ;2023. (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Taghavi, F. et al. Energetic domains and conformational analysis of human serum albumin upon co-incubation with sodium benzoate and glucose. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynamics. 32 (3), 438–447 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sompong, W., Cheng, H. & Adisakwattana, S. Ferulic acid prevents methylglyoxal-induced protein glycation, DNA damage, and apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. Biochem.73, 121–131 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner, L. M. [8] quantitative determination of thiol groups in lowand high molecular weight compounds by electron paramagnetic resonance. Methods Enzymol.251, 87–105 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khodaei, F., Kholghipour, H., Hosseinzadeh, M. & Rashedinia, M. Effect of sodium benzoate on liver and kidney lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in mice. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci.8 (2), 217–223 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer, D., Li, Y., Ahlemeyer, B., Krieglstein, J. & Kissel, T. In vitro cytotoxicity testing of polycations: influence of polymer structure on cell viability and hemolysis. Biomaterials24 (7), 1121–1131 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoshnoud, M. J. et al. The protective effect of nortriptyline against gastric lesions induced by indomethacin and cold-shock stress in rats. Iran. J. Toxicol.14 (3), 155–164 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zare, S. et al. 6-Bromoquinazoline derivatives as potent Anticancer agents: synthesis, cytotoxic evaluation, and computational studies. Chem. Biodivers.20 (7), e202201245 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baziyar, L. et al. Novel uracil derivatives as anti-cancer agents: design, synthesis, biological evaluation and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct.1302, 137435 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emami, L. et al. Design, synthesis, molecular simulation, and biological activities of novel quinazolinone-pyrimidine hybrid derivatives as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and anticancer agents. New J. Chem. (2020).

- 22.Emami, L. et al. Molecular Docking and Antimicrobial evaluation of some Novel pyrano [2, 3-C] pyrazole derivatives. Trends Pharm. Sci.6 (2), 113–120 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emami, L. et al. Synthesis, design, biological evaluation, and computational analysis of some novel uracil-azole derivatives as cytotoxic agents. BMC Chem.18 (1), 3 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ataollahi, E. et al. Novel quinazolinone derivatives as anticancer agents: design, synthesis, biological evaluation and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct.1295, 136622 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehghani, H., Rashedinia, M., Mohebbi, G. & Vazirizadeh, A. Studies on secondary metabolites and in vitro and in silico anticholinesterases activities of the Sea Urchin Echinometra mathaei crude venoms from the Persian Gulf-Bushehr. Nat. Prod. J.14 (2), 14–31 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu, J., Liu, J-Y., Xiong, W-M., Zhang, X-Y. & Zheng, Y. Binding interaction of sodium benzoate food additive with bovine serum albumin: multi-spectroscopy and molecular docking studies. Bmc Chem.13, 1–8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobanov, M. Y., Bogatyreva, N. & Galzitskaya, O. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol. Biol.42, 623–628 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh, R., Barden, A., Mori, T. & Beilin, L. Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia44, 129–146 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mote, U., Bhattar, S., Patil, S. & Kolekar, G. Interaction between felodipine and bovine serum albumin: fluorescence quenching study. Luminescence25 (1), 1–8 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khoirunnisa, W., Nur, M., Widyarti, S., Permana, S. & Sumitro, S. (eds) Physiologic glycated-bovine serum albumin determination using spectrum-uv. Journal of Physics: Conference Series; : IOP Publishing. (2019).

- 31.Szkudlarek, A., Pożycka, J. & Maciążek-Jurczyk, M. Influence of piracetam on gliclazide—glycated human serum albumin interaction. A spectrofluorometric study. Molecules24 (1), 111 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meeprom, A., Sompong, W., Chan, C. B. & Adisakwattana, S. Isoferulic acid, a new anti-glycation agent, inhibits fructose-and glucose-mediated protein glycation in vitro. Molecules18 (6), 6439–6454 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumari, P., Akhila, S., Rao, Y. S. & Devi, B. R. Alternative to artificial preservatives. Syst. Rev. Pharm.10, 99–102 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guan, J., Yan, X., Zhao, Y., Sun, Y. & Peng, X. Binding studies of triclocarban with bovine serum albumin: insights from multi-spectroscopy and molecular modeling methods. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.202, 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi, J-H., Zhou, K-L., Lou, Y-Y. & Pan, D-Q. Multi-spectroscopic and molecular modeling approaches to elucidate the binding interaction between bovine serum albumin and darunavir, a HIV protease inhibitor. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.188, 362–371 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. We have presented all data in the form of Figures. The PDB code (4F5S) was retrieved from protein data bank (www. rcsb. org). https:// www. rcsb. org/ structure/ 4F5S.