Abstract

Background

While high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) and their stereotyped clusters (sHFOs) have emerged as potential neuro-biomarkers for the rapid localization of the seizure onset zone (SOZ) in epilepsy, their clinical application is hindered by the challenge of automated elimination of pseudo-HFOs originating from artifacts in heavily corrupted intraoperative neural recordings. This limitation has led to a reliance on semi-automated detectors, coupled with manual visual artifact rejection, impeding the translation of findings into clinical practice.

Methods

In response, we have developed a computational framework that integrates sparse signal processing and ensemble learning to automatically detect genuine HFOs of intracranial EEG data. This framework is utilized during intraoperative monitoring (IOM) while implanting electrodes and postoperatively in the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) before the respective surgery.

Results

Our framework demonstrates a remarkable ability to eliminate pseudo-HFOs in heavily corrupted neural data, achieving accuracy levels comparable to those obtained through expert visual inspection. It not only enhances SOZ localization accuracy of IOM to a level comparable to EMU but also successfully captures sHFO clusters within IOM recordings, exhibiting high specificity to the primary SOZ.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that intraoperative HFOs, when processed with computational intelligence, can be used as early feedback for SOZ tailoring surgery to guide electrode repositioning, enhancing the efficacy of the overall invasive therapy.

Subject terms: Diagnostic markers, Epilepsy, Neural decoding

Plain language summary

Medication-resistant epilepsy is a form of epilepsy that cannot be controlled with drugs. In such cases, surgery is often required to remove the brain regions where seizures start. To identify these areas, electrodes are typically implanted in the brain, and the patient’s brain activity is monitored for several days or weeks in the hospital, a process that can be lengthy and risky. We investigated whether seizure-causing brain regions could be identified earlier by applying a computational intelligence method to brain signals recorded during electrode implantation surgery. Our algorithm automatically detected abnormal high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) associated with epileptic brain tissue, improving the accuracy of identifying the areas that need to be removed. This approach could help clinicians make quicker, more precise decisions, reducing the need for prolonged monitoring and minimizing risks.

Fazli Besheli et al. identify intraoperative high frequency oscillations (HFOs) using noise-resilient computational intelligence to effectively localize seizure-generating brain regions. Epileptogenic zones are identified from brief intraoperative neural recordings.

Introduction

In medically refractory epilepsy cases, removing the seizure onset zone (SOZ), where the seizure originates, is the most promising treatment1–3. Intracranial electroencephalogram (iEEG) is a diagnostic modality that is frequently used to identify the SOZ through prolonged monitoring. It entails the implantation of intracerebral (depth) and/or subdural macro electrodes directly placed in candidate sites of the brain and monitoring brain activities over days to weeks3. Studies have provided compelling evidence that prolonged iEEG recording is a proficient method for locating SOZ4,5.

The high-frequency oscillations (HFO) in iEEG are characterized by their rapid changes in electrical activity with a frequency range of 80–600 Hz and short durations lasting tens of milliseconds6. Based on their spectral range, HFOs are divided into ripple (R: 80–250 Hz) and fast ripple (FR: 250–600 Hz)6–10 and those with activities in both bands11. These oscillations, especially the less frequent FRs, are considered a promising biomarker for the SOZ7,12,13. Several studies evaluated and confirmed the efficacy of interictal HFOs in localizing the SOZ and predicting the surgical outcome8,13–17. Nevertheless, the brief duration and low amplitude of HFOs, combined with the extensive volume of iEEG recordings, pose a substantial time requirement for their manual visual identification. To address this challenge, there is a growing interest within the research community to develop automated detectors, with a particular focus on the translation of HFO analysis into the clinical workflow8,18–25.

Recent studies have shown that aside from HFOs detected in the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU), those captured during intraoperative monitoring (IOM) are also associated with ictogenesis22,26–31. Since the intraoperative recording is performed immediately after the implantation of the electrodes, the spatial distribution of HFOs can serve as a valuable resource for providing prompt feedback to clinicians following the electrode implantation procedure. Furthermore, it may reduce the demand for prolonged iEEG evaluation.

However, the noisy intraoperative environment corrupts the iEEG recordings and makes the data analysis of HFOs difficult to interpret. Numerous studies have indicated that the iEEG can be contaminated with artifacts that mimic real-HFOs32–34. This problem is even more challenging when the neural data is assessed intraoperatively22,28–30. The substantial background interferences in the operating room (OR) caused by electrical devices and the movements of the surgical team can lead to the amplification of artifacts. These high-frequency artifacts, so-called pseudo-HFOs24, heavily contaminate the iEEG, lead to a high rate of false positives, and mask the distribution of real-HFOs. These challenges make the automatic HFO analysis difficult and limit its clinical translation. Therefore, a two-level approach based on a semi-automatic HFO detection involving a low computational automatic detector and visual assessment is commonly used in the intraoperative iEEG data to eliminate these pseudo-HFOs before any subsequent analysis27–31,35–38.

This study aims to establish an HFO detection pipeline to effectively overcome the challenge posed by substantial artifacts in intraoperative recordings. In this scheme, we developed and tested computational tools based on sparse signal processing that learn waveform morphology with neural origin to represent real-HFOs and discard the pseudo-ones effectively. We evaluated the rate, and spatial distribution of HFO and its subtypes, i.e., R, FR, in both IOM and EMU theaters for SOZ localization. In addition, the presence of stereotypical HFOs39 and their specificity to SOZ is further elucidated in both IOM and EMU scenarios. The findings of this study provide preliminary evidence towards the early identification of SOZ from brief intraoperative recordings and future potential for “HFO tailored surgery”.

Methods

Study design

The primary objective of this study is to assess the feasibility of predicting the SOZ from brief intraoperative monitoring as an early feedback tool for surgical planning in patients with epilepsy. The secondary objective is to compare the performance of IOM recordings with their corresponding EMU sessions. The iEEG was recorded at the University of Minnesota Medical Center (MN, USA) and Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) affiliated hospitals, including St. Luke’s Hospital and Texas Children’s Hospitals (TX, USA). The iEEG recordings were conducted at a sampling frequency of either 2 or 2.4 kHz. Those recorded at 2.4 kHz underwent downsampling to 2 kHz prior to HFO analysis as part of the data preprocessing. Additional information regarding the recording hardware can be found in Supplementary Data 1. All participants provided informed consent, and the institutional review boards (IRBs) approved the study protocol at each data collection site (University of Minnesota Medical Center IRB, ID: 1106M01362 and Baylor College of Medicine IRB, ID: H-37057), as well as at the institutions where the anonymized retrospective data analysis was conducted (Mayo Clinic IRB, ID: 23-009480 and University of Houston IRB, ID: 00000345). The clinical epilepsy surgery program selected focal epilepsy patients with focal impaired (complex partial) seizures and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures that were refractory to four anti-seizure medications. The surgical experts reviewed comprehensive clinical data to hypothesize possible sites of SOZ for determining the locations of intracranial electrodes, using clinical criteria described elsewhere40,41. For the retrospective analysis, we included those subjects with intraoperative neural recordings and their corresponding EMU data sampled with at least a 2 kHz sampling rate and clear SOZ delineation. By including temporal and extratemporal cases, the study aimed to avoid selection bias and provide a comprehensive analysis of intraoperative HFOs in a real-world clinical setting. This dataset is heterogeneous, encompassing data from different hospitals, including both pediatric (n = 14) and adult (n = 15) cases. The researchers who designed and implemented the analysis pipeline for HFO detection and classification were blinded to clinical information, including the SOZ, surgical procedure details, and surgical outcomes. While all participants had complete demographic and baseline clinical data, follow-up data for surgical outcomes was unavailable for participant P7. The SOZ was carefully defined by epileptologists following a visual inspection of the onsets of multiple clinical seizures in the continuous iEEG. Here it should be noted that clinically defined SOZ is just an estimate for the epileptogenic zone (EZ). They looked for specific patterns, such as abrupt voltage shifts, rhythmic discharges, or focal spikes, to identify the areas where seizures originate. This process involves examining the iEEG recordings with synchronized video for consistent seizure patterns across multiple events. Epileptologists look for the earliest ictal changes, which may include low-voltage fast activity, spike-and-wave complexes, or other characteristic electrophysiological markers. They also consider the spatial distribution and propagation of these patterns to pinpoint the precise location of the SOZ. All iEEG data underwent the same offline analysis using fully automated techniques without any channel selection or pre-processing. The proposed method was evaluated using a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation (LOSOCV) approach to assess its generalizability to new data beyond the current samples. We should also mention that in our analysis, the electrode labels are used as a general categorization for channels presumed to be located in or around specific brain regions. We acknowledge that this categorization may include some contacts that pass through other regions, such as the white matter. This poses a limitation when comparing the spatial distribution of HFO in the IOM and EMU analyses, as it is conducted on a lead rather than on specific brain regions, which would require MRI and CT imaging and co-registration of these images.

Amplitude threshold detector and annotation of events

We used a previously established detector24,42 to form the initial pool of events. This detector utilized amplitude-threshold-based detection and was applied to the iEEG data in R and FR bands separately. The threshold is computed based on the level of background activities using an adaptive method. A pool of events is formed with a duration of 256 ms and a minimum of six threshold crossings with a frequency larger than 80 and 250 Hz for R and FR bands, respectively. Events that exceed the detection threshold in the R band but not in the FR band are classified as ripples. All events that exceed the detection threshold in the FR band, even if they have an R component, are classified as fast ripples. Thus, HFOs encompass all detected events, with Rs and FRs being the two subcategories based on their frequency components. Thus, the total number of HFOs is the sum of the number of Rs and the number of FRs. Corresponding raw events are further processed to locate their high-frequency components at the center of each event and merge similar segments containing R and FR components with an interval <30 ms into a single event.

Using the amplitude threshold detector, an HFO event pool was formed for each subject. With a graphical user interface (GUI) designed in MATLAB24, three experts (B.F., S.K., and Z.S.) meticulously annotated at least 200 real and pseudo-HFOs in both IOM and EMU event pools for each subject, provided there were sufficient events available. For visual inspection, the experts were provided with the raw signal, its filtered version in the HFO bands, and the time–frequency plane representation of the raw event. Due to the lack of well-established criteria or definitions for HFOs of neural origin, we employed a heuristic approach for their identification. This method relies on the consensus of visual inspection of multiple human experts. Specifically, the so-called “real” HFOs, as determined through majority voting during visual inspection, are those deemed not to be artifacts of non-neural origin.

Local cascaded residual-based dictionary learning

After forming the pool of events, we represent each candidate event using a data-driven dictionary shaped for representation and classification. We train a local dictionary that constructs a group of samples rather than reconstructing the whole event globally. This allows for capturing local variations within the candidate events more accurately and having a more compact representation than the global dictionary.

To capture HFO patterns, we introduced a local cascaded residual-based dictionary learning (LCRDL) framework that uses the residual of the data as input to the next stage, allowing finer details to be captured (Supplementary Fig. S1a) compared with a single-level joint dictionary (see Supplementary Figs. S2, 3) approach43. Breaking the dictionary learning down into different layers reduces the complexity of the dictionary and makes it more interpretable in terms of frequency ranges. Integrating a cascaded learning-based framework with local dictionaries offers the advantage of learning iEEG non-stationary components in the HFO events. The LCRDL approach employed in this study involves four layers of learning, contributing to the refinement of event reconstruction and progressively learning the higher frequency components. The first layer is learned through annotated raw HFO segments, while the second, third, and fourth layers focus on learning local atoms from the residual of previous layers. The residual at each layer is computed by taking the difference between the previous original event and the reconstructed event using the learned dictionary and adaptive sparse local representation (ASLR) method (Supplementary Fig. S1b).

The proposed framework (Supplementary Fig. S1) uses a 256 ms HFO candidate (R0) as input, which is buffered along with computed segments () for kSVD dictionary learning44. The learned dictionary at the coarsest level (D1) reconstructs the candidate events using the ASLR method, and the residual at this layer (R1) serves as input to the next layer. In subsequent layers (), an HFO attention-based amplitude threshold detector is utilized to discard segments without high-frequency components distinguishable from background activity. We conducted extensive experiments and analyses to determine the optimal values for these parameters to ensure each parameter was fine-tuned to represent raw HFO events effectively (see Supplementary Fig. S4). Finally, the annotated real-HFOs from both recording scenarios are used to learn two distinct dictionaries, and both real and pseudo-HFOs are used to train the classification model.

Adaptive sparse local representation

After learning the dictionary, we represent the events (n is the length of events) using atoms learned locally in each layer45. To achieve this, we start to represent the buffered segment, denoted as (m is the length of dictionary atoms and m < n), using the learned dictionary that contains k atoms with the same length as the segments. The representation of the segment using a limited number of components in the dictionary, D can be formulated as

| 1 |

Here, represents the sparse coding coefficient vector calculated using a greedy search algorithm called orthogonal matching pursuit (OMP). In this study, we represented these overlapped segments using the learned dictionary in each layer. Finally, we could represent the entire event by integrating the reconstructed segments of each layer.

Since these segments overlap, we take the average of the local representations smoothed at the edges using a Tukey window. These averaged segments then serve as the comprehensive representation of at each layer l. Based on the frequency content, we grouped the and as one group of dictionaries. Consequently, in the initial layer of ASLR, the overall signal is represented using a 64 ms moving window and 8 ms overlap. In the second layer, using , the overall signal is represented using a 64 ms window and 4 ms overlap. Finally, for the third level, using and with a 32 ms window and 4 ms overlap (Supplementary Fig. S1b). For a short video demonstrating the ASLR process, please refer to Supplementary Movie 1.

Feature extraction and classification accuracy

The event representation quality is crucial in distinguishing between real and pseudo-HFOs. We extracted features (see Supplementary Fig. S5a–d) to measure representation quality from various perspectives:

Global approximation error

The overall representation quality of the event in each layer is computed as follows, which shows the approximation error of an event:

| 2 |

Variability factor of residuals

To determine the quality of high-frequency oscillatory event representation, a metric called V-Factor is computed as the ratio of the range to the standard deviation of residual signal in deep layers:

| 3 |

Maximum coefficient of representation

After the reconstruction of all segments , we calculated the coefficient matrix for the reconstruction phase, where a is the sparsity level, and k is the number of segments. The maximum coefficient within this matrix indicates the degree of similarity between the event at each layer and the learned dictionary.

Maximum improvement in approximation error

Once all segments are represented, we evaluate the local approximation error within each segment denoted as . To investigate the impact of increasing the sparsity level or the number of atoms used to represent each segment, we computed the local approximation error matrix for varying sparsity levels denoted as . Additionally, we analyze the degree of improvement obtained by increasing the number of atoms employed for segment representation. The amount of improvement within each segment is computed and stored in a matrix denoted as . The maximum improvement that can be achieved by increasing the sparsity level is defined as . In other words, the represents the highest difference in approximation error achieved by increasing the sparsity level from one to the maximum number of atoms for representation.

Overall approximation error at the center of event

With the first layer having a frequency below 80 Hz and deeper layers having frequencies from 80 Hz to over 600 Hz, we expect to represent all oscillatory high-frequency components sitting at the center of the event after the representation of an event in all layers. Therefore, the maximum of (residual signal after 3rd level of representation) around the center serves as another feature indicating the quality of representation:

| 4 |

where the central range is defined as 32 ms duration.

First temporal eigenvalue in the coefficient matrix of representation

Power line interference in iEEG recordings can create fake oscillations resembling HFOs. To address this issue, we used a feature derived from the absolute value of the coefficient matrix. The maximum eigenvalue of this coefficient matrix in the first layer of representation () helps identify abnormal repetitive non-neural patterns. We computed the correlation matrix as

| 5 |

In the next step, we employed the eigenvalue decomposition to find the largest eigenvalue of the absolute value of matrix M:

| 6 |

A high maximum eigenvalue suggests the presence of a repetitive selection of the same atoms, which is characteristic of artifactual signals with non-neural origins (see Supplementary Fig. S6).

Range of raw event

To generalize these features based on the amplitude of the original event, we used the range of raw events as the final feature.

Random forest classifier

A random forest (RF) classifier was used to classify real and pseudo-HFOs annotated by experts. Due to the inherent challenges in defining HFOs with a universally accepted standard and in assessing the success of pseudo-HFO cancellation, we relied on annotations provided by three independent experts. They individually identified HFO and pseudo-HFO events from a pool of initial candidates. The inter-rater agreement among the experts was between 90% and 96% across subjects. To establish ground truth labels for real and pseudo-HFOs, we adopted a majority voting scheme. We then applied a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation approach, using one subject as the test set while training the model on the remaining subjects. This method evaluates how accurately the classification framework replicates the decisions made by experts. Since the goal of supervised learning is to replicate human decision-making, the performance of our method was measured by its alignment with the majority votes of the three experts. Despite human errors, a high level of agreement between the classifier and the expert consensus indicates the effectiveness of the model in replicating human decision-making. The classification performance was evaluated in both recording scenarios, and a confusion matrix was obtained for each recording scenario.

HFO analysis and the characteristics of learned atoms and classifier

We identified the real-HFOs in both IOM and EMU scenarios by applying the proposed method, and the results were formed in two distinct ways: firstly, we demonstrated the effectiveness of this method in eliminating pseudo-HFOs in both IOM and EMU. Secondly, the cross-analysis between IOM and EMU data was performed by applying their dictionary and RF model to each other (Supplementary Fig. S5e). Finally, we assessed the viability of utilizing the RF model to remove pseudo-HFOs from the pool of initially detected IOM and EMU events. Moreover, we further compared the HFO, R, and FR populations that were detected in both scenarios, their spatial distribution, and their relation to SOZ and surgical outcome. We identified clusters of homogeneous HFOs with repetitive waveforms, which have been reported highly specific to the SOZ39. This identification was achieved using the density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) algorithm on the pool of detected events, following the elimination of pseudo-HFOs. The DBSCAN algorithm requires two parameters: the minimum number of data points () and the radius of the neighborhood (ε) to form a cluster within that Euclidean distance between at least a minPts number of events. We employed a fixed minPts set to 3. We iteratively increased the ε value from 0.01 to 0.25 as mentioned in ref. 39 until the first dense cluster emerged, including at least three HFO events. This initial cluster of events was designated as stereotyped HFOs (sHFO), reflecting the HFOs with the highest level of similarity.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means ± standard deviation. We performed all the statistical analyses in MATLAB 2019b (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). To compare the means between groups without assuming a specific distribution of the analysis results, we used non-parametric tests. For data with a non-parametric distribution, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann–Whitney U test). The significance level (alpha) was set to 0.05. To assess the performance of the proposed method at the subject level, the negative and positive predictive values were computed46 between the HFO region and clinically defined SOZ.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

An overview of the analysis framework

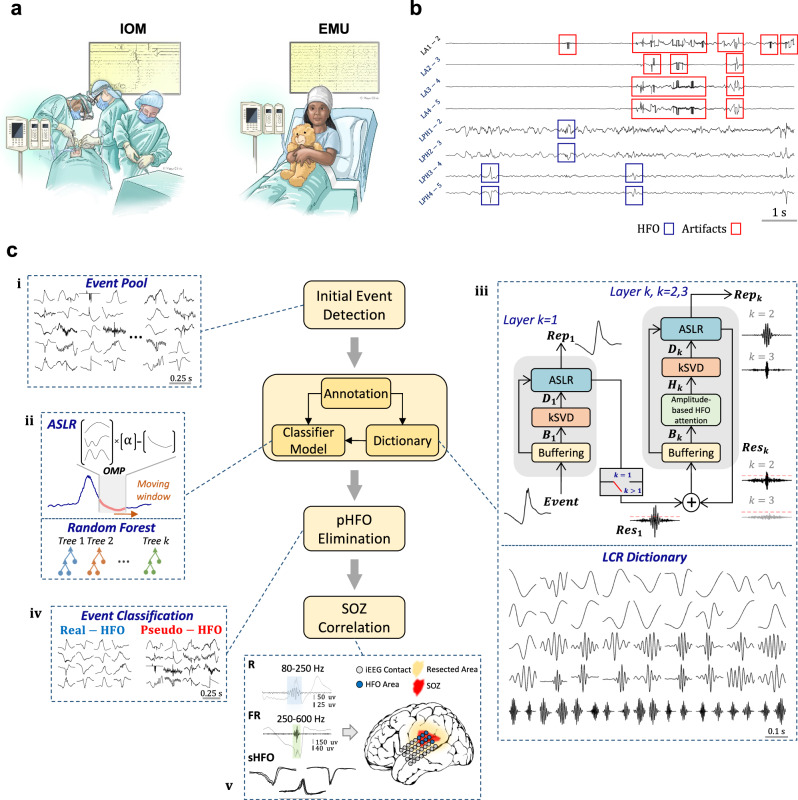

As shown in Fig. 1a, the neural recordings were initially obtained during the IOM and later in the EMU. A typical segment of the IOM neural data that was heavily corrupted by artifacts is visualized in Fig. 1b. The overall data processing pipeline, including the initial HFO detection, waveform dictionary learning, and classification, is provided in Fig. 1c. A previously published amplitude threshold-based detector24 with high sensitivity but low specificity was employed to form an initial pool of events (section (i) Fig. 1c), including real and pseudo-HFOs. Using a GUI, three experts meticulously annotated at least 200 real and pseudo-HFOs in IOM and EMU recordings for each subject, provided there were enough events available. Subsequently, these annotated datasets were utilized to learn a dictionary of waveforms and to train a classifier capable of distinguishing between real and pseudo-HFO events, as illustrated in Fig. 1c, section (ii). Specifically, the annotated real-HFO events were used in a cascaded stage-wise dictionary learning framework to capture a redundant set of multiscale waveform patterns that characterize the visually annotated real-HFO events (Fig. 1c section (iii), and Supplementary Fig. S1a). Next, only a small subset of these waveforms was used to locally represent45 the annotated HFO events. The averaged ASLR approach, as illustrated in Fig. 1c section (ii) and Supplementary Fig. S1b, is an efficient method for reconstructing real-HFO waveforms. However, it has been observed that ASLR is not effective in reconstructing pseudo-HFO events due to the biased structure of the dictionary towards the representation of real-HFO morphology. Using ASLR, each candidate event was reconstructed, and various features (Supplementary Fig. S5), including approximation error, were extracted, and fed to a RF classifier. This classifier aims to achieve a level of accuracy comparable to that of visual assessment by experts in distinguishing between real and pseudo-HFO events. Finally, the learned model was applied to the entire HFO pool to eliminate the pseudo HFOs (section (iv) Fig. 1c) and characterize the spatial distribution of real-HFO, and its overlap with the SOZ, as shown in Fig. 1c section (v).

Fig. 1. Schematic of data analysis workflow.

a Recording scenario: This panel showcases various scenarios in which iEEG data is acquired, i.e., IOM and EMU. (Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved.) b A 10-s segment of iEEG recording with HFOs and high-frequency artifacts. c iEEG recordings from both scenarios go through the initial stage, where an amplitude-threshold detector (i) is applied, forming a pool of initial HFO events, including both real and pseudo-HFOs. All events are then represented with an averaged adaptive sparse local representation (ii) using a multi-resolution dictionary learned from the annotated subset of real-HFOs through a cascaded residual-based learning framework (iii). In residual-based learning, the residual of the previous layer is input into the next layer to create different layers of dictionaries. Subsequently, informative features are extracted for classification. Finally, a random forest model classifies the events into two categories: real-HFOs and pseudo-HFOs (iv). The results are validated with clinical information (v) in terms of accuracy to detect SOZ, resected area, and surgical outcome. IOM intraoperative monitoring, EMU epilepsy monitoring unit, ASLR adaptive sparse local representation, OMP orthogonal matching pursuit, kSVD k-singular value decomposition, R ripple (80–250 Hz), FR fast ripple (250–600 Hz), sHFO stereotyped high-frequency oscillation, SOZ seizure onset zone, LCR local cascaded residual, pHFO pseudo-high-frequency oscillation, iEEG intracranial electroencephalography.

Overall iEEG data and annotated events

We studied a total of 13 h of iEEG recordings from 29 participants (14 pediatric and 15 adults, see Supplementary Data 1 for demographics). A total of 331 leads were implanted, and 2768 bipolar contacts were meticulously examined. Notably, 66/331 (20%) of the electrodes were situated within the clinically defined SOZ. The length of IOM recordings varied between 1.5 and 19.5 min, with an average of 9.2 min. The interictal iEEG segments of the EMU were 20 min long to be comparable with the brief IOM data. We initially captured a total of 57,325 events in IOM and 140,594 events in EMU using an established amplitude threshold-based detector24. Across all subjects, 4929 real-events and 5054 pseudo-events were annotated in the IOM, while the EMU scenario had 5628 real events and 4928 pseudo-events.

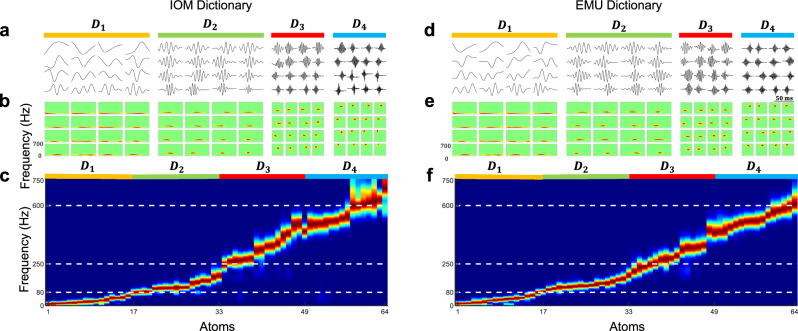

The learned multi-scale dictionary atoms

We used annotated real-HFO events to learn four different cascaded dictionaries , , , and . To gain a better understanding of the learned waveforms in each layer, in Fig. 2, we visualized the raw waveforms and their power spectrum. Specifically, we presented a 4 × 4 patch of learned dictionary atoms at each layer (i.e., , …, ) of IOM and EMU recordings learned from the annotated real-HFO events. The dictionary is learned from the residual of waveforms that were represented with Dictionary . Our observations revealed that not only do these atoms exhibit distinct characteristics, but their frequency content also exhibits a gradual increase from low to high band at each level from to . Specifically, the first layer captured atoms with energies below 80 Hz, representing the slowly changing low-band components of the HFO events. As we progress to the second layer, , an oscillatory structure can be observed in the learned atoms. Their frequency spectrum spanned a range roughly between 80 and 250 Hz, corresponding to the R band. The dictionary atoms in subsequent layers extended into the FR band above 250 Hz, and Supplementary Fig. S3 provides further details on the frequency of all learned atoms. These findings suggest that while the shallow layer has the potential to capture the morphology of raw events, deeper layers are more suitable to capture the finer details and high-frequency oscillatory components. (More information on the learning parameters can be found in Supplementary Fig. S4.) Furthermore, the comparison between cascaded residual-based dictionary learning and standard dictionary learning can be found in Supplementary Figs. S2, 3).

Fig. 2. The learned dictionaries in IOM and EMU recordings.

The figure illustrates four layers of learned dictionaries (D1–D4) and their respective properties across IOM (a–c) and EMU (d–f). a (IOM) and d (EMU) show a patch of 4 ⨯ 4 examples of learned dictionary atoms for each layer, with color shading indicating the depth of the layers: D1 (orange) represents the shallowest layer, D2 (green) the second layer, D3 (red) the third layer, and D4 (blue) the deepest layer. b (IOM) and e (EMU) present the corresponding time–frequency maps for each learned atom, visualized using the Wigner–Ville distribution, enabling time–frequency analysis of the components. c (IOM) and f (EMU) display the power PSD maps for all selected learned atoms, grouped by their respective layers. The PSD plots are color-coded according to the shading of each layer (orange for D1, green for D2, red for D3, and blue for D4). The x-axis represents the individual dictionary atoms, while the y-axis shows their power spectral densities. The combined plots of all atoms reveal how frequency components vary across layers, forming a comprehensive PSD image. In both recording scenarios (IOM and EMU), the learned atoms in D1 primarily captured low-frequency components, below 80 Hz. As the layers deepen (D2–D4), the PSD peaks shift progressively toward higher frequencies, with D4 capturing the highest frequencies, including fast ripples (FR) around 600 Hz. PSD power spectral density, IOM intraoperative monitoring, EMU epilepsy monitoring unit.

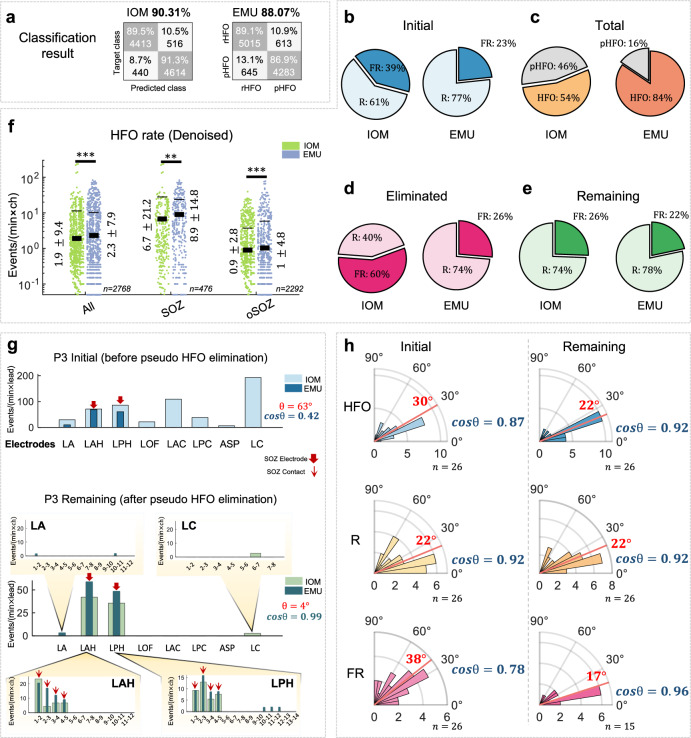

Real and pseudo-HFO rates in IOM and EMU scenarios

The discrimination between annotated real and pseudo-HFOs was performed utilizing the learned waveform dictionaries. Our framework achieved an average accuracy of 90.3% for IOM and 88.1% for EMU in distinguishing between annotated real and pseudo-HFOs via LOSOCV, as displayed in Fig. 3a.

Fig. 3. The statistical comparison between IOM and EMU.

a The confusion matrix of classification of real and pseudo-HFO events in IOM (90.31%) and EMU (88.07%). No statistically significant differences were found between the accuracy of IOM and EMU classification (p = 0.15). b The number of initially detected R and FR events. c The total number of detected real and pseudo-HFOs in IOM and EMU. d The number of eliminated R and FR events after applying the proposed method. e The number of R and FR events that passed the proposed method. f Normalized HFO rate from all, SOZ, and out of SOZ channels in IOM and EMU (event per minute per contact) after pseudo-HFO elimination. The thick lines in the plot represent the mean values, while the thin error bars indicate the mean ± standard deviation (std). Values in this section are presented as mean ± std. g The correlation between the spatial distribution of events detected before and after pseudo-HFO elimination in a representative subject (P3). LA left amygdala, LAH left anterior hippocampus, LPH left posterior hippocampus, LOF left orbital frontal, LAC left anterior cingulate, LPC left posterior cingulate, ASP left anterior-superior precuneus, LC left anterior cuneus. h The median angle (red line) and the cosine similarity between the spatial distribution of HFO, R, and FR over electrodes of all subjects between IOM and EMU scenarios before (initial) and after (remaining) pseudo-HFO elimination. (N.S. indicates that the p-value is above 0.05.) IOM intraoperative monitoring, EMU epilepsy monitoring unit, HFO high- frequency oscillation, R ripple, FR fast ripple, rHFO real-HFO, pHFO pseudo-HFO, SOZ seizure onset zone, oSOZ out of seizure onset zone.

We employed the trained classification model on the entire pool of events using LOSOCV and quantified the distribution of the events before and after the elimination of pseudo-HFOs. We noticed that within the initial pool of events, the percentage of FRs in the IOM was noticeably larger than in the EMU (Fig. 3b, 39% vs. 23%). After applying the classification framework, which was trained using the annotated events, 46% of the IOM events and 16% of the EMU events were eliminated (Fig. 3c). Notably, among the eliminated pseudo-HFOs, 60% of them were classified as FRs in IOM. In comparison, only 26% of the events were classified as FR in the EMU (Fig. 3d). These results suggest that the initial pool included many pseudo-HFOs that mimicked FRs. Following the elimination of pseudo-HFOs, the percentage of FR events in the EMU and IOM were comparable (26% and 22% in the IOM and EMU, respectively Fig. 3e). By looking at the normalized HFO rate in SOZ and oSOZ contacts, independent of the subjects, the average of HFOs per contact per minute after pseudo-HFO elimination is provided in Fig. 3f. Regardless of the clinically defined SOZ, the overall HFO rate across all contacts was 1.9 ± 9.4 in IOM recordings and 2.3 ± 7.9 in EMU recordings (p = 1.2e−5). Considering the SOZ, the average normalized HFO rate for SOZ contacts was 6.7 ± 21.2 in IOM recordings and 8.9 ± 14.8 in EMU recordings (p = 5e−3). For oSOZ contacts, the average normalized HFO rate was 0.9 ± 2.8 in IOM recordings and 1 ± 4.8 in EMU recordings (p = 7e−9). The normalized rate of events across subjects is also summarized in Supplementary Fig. S7a–c.

Spatial distribution of HFO in the IOM and EMU

Although the rate of HFOs differs at the contact level between IOM and EMU, their spatial distribution is consistent across both recording scenarios. The cosine similarity (similarity = cosϴ) as a measurement between HFO spatial distribution vectors was evaluated to quantify the agreement HFOs between EMU and IOM recordings. This involves assessing whether the spatial distribution vector of the HFO rate across channels between IOM and EMU scenarios is consistently aligned. For a single representative subject (P3), the disagreement between the spatial distribution of initially captured events in the IOM and EMU is shown (Fig. 3g). Nevertheless, when pseudo-HFOs were eliminated, both distributions became more aligned (ϴ = 4°, similarity = 0.99) compared to the initial values (ϴ = 63°, similarity = 0.42). This alignment was particularly evident within SOZ contacts. Specifically, the spatial distribution of HFOs in the first few contacts of the LAH and LPH electrodes, both likely to reside within the target structures (left anterior and posterior hippocampus), demonstrated high consistency between IOM and EMU recordings. Furthermore, a visual representation of raw iEEG data within the LAH electrode and the heat map of detected events across all contacts is summarized in Supplementary Fig. S8. In group analysis, as depicted in Fig. 3h, the median angle between initially captured events across all subjects was 30° (similiarity = 0.87). However, after the removal of pseudo-HFOs, the angle between distributions decreased to 22° (p = 0.03), indicating a higher level of agreement between the spatial distribution of the recording scenarios (mean similarity = 0.93).

As shown in Fig. 3h, a large misalignment between the FR distribution in the IOM and EMU was initially observed (median: 38°, similarity: 0.79), which was reduced after removing the pseudo-HFOs (median: 17°, similarity: 0.96, p = 0.02). However, we noticed that the distribution of Rs was not affected by pseudo-HFO elimination (p = 0.51). This relates to the fact that pseudo-HFOs with sharp artifacts are more likely categorized as FRs than Rs.

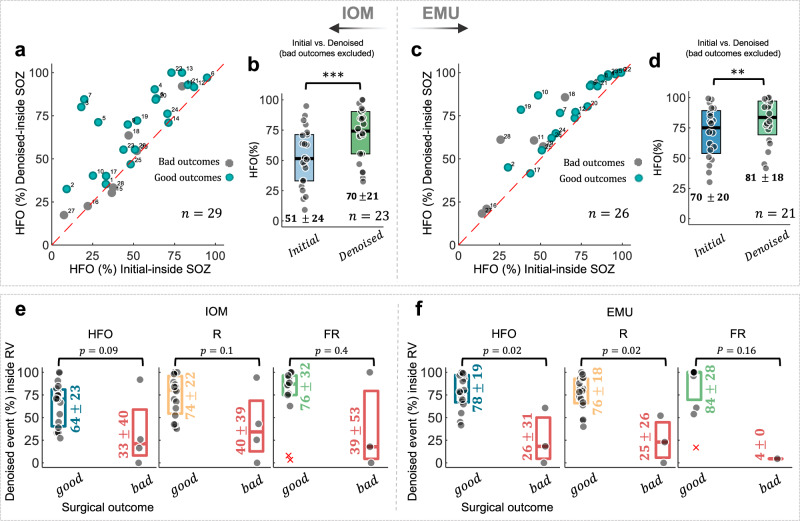

SOZ localization accuracy of initially detected and post-processed HFOs

The SOZ localization accuracy is quantified based on the HFO spatial distribution. This is achieved by calculating the ratio of HFOs within SOZ channels before and after pseudo-HFO elimination (see Fig. 4). When the initially detected HFO events were used for prediction, the SOZ localization accuracy was 51% for IOM and 70% for the EMU (51%, vs. 70%, p = 8.3e−5, Fig. 4a, b). After the elimination of the pseudo HFOs, the SOZ localization accuracy was improved in both IOM and EMU (70% vs. 81%, p = 0.001, Fig. 4d) theaters among subjects with a favorable outcome.

Fig. 4. The relationship between HFO and clinical SOZ and outcome.

a, c The agreement plot of the amount of HFO (%) coming from SOZ before and after pseudo-HFO elimination. The subjects with good outcomes (Engel class I, II) were color-coded with green, while those subjects with poor outcomes (Engel class III and IV) were color-coded with gray. b, d The box plot of SOZ localization accuracy using the HFO distribution in both IOM and EMU scenarios for subjects with good surgical outcomes. e, f The relationship of HFO distribution and the surgical target region: The percentage of HFOs, Rs, and FRs coming from the target region of surgical therapy (resection volume: RV) is calculated for both IOM and EMU data. All HFOs, Rs, and FRs are predicting the outcome of surgeries in both IOM (good outcome: HFO: 64%, R: 74% FR: 76% and bad outcome: HFO: 33%, R: 40%, FR: 39%) and EMU (good outcome: HFO: 78%, R: 76%, FR: 84% and bad outcome: HFO: 26%, R: 25%, FR: 4%) scenarios. Sample sizes (n): IOM HFO (good outcome: n = 19, bad outcome: n = 4), IOM R (good outcome: n = 19, bad outcome: n = 4), IOM FR (good outcome: n = 14, bad outcome: n = 3), EMU HFO (good outcome: n = 17, bad outcome: n = 3), EMU R (good outcome: n = 17, bad outcome: n = 3), EMU FR (good outcome: n = 11, bad outcome: n = 1). The error bars represent the median with 25th and 75th percentiles. All values in this figure are presented as mean ± standard deviation (std). * Suggests significance at 0.05 level, ** suggests significance at 0.01 level, and *** suggests significance at 0.001 level. IOM intraoperative monitoring, EMU epilepsy monitoring unit, HFO high-frequency oscillation, R ripple, FR fast ripple, SOZ seizure onset zone, RV resected volume.

The agreement plot (Fig. 4a, c) shows that most subjects with good outcomes were placed in the off-diagonal upper-west quadrant in both recording scenarios. Additionally, those subjects with poor outcomes were predominantly located in the lower-east quadrant of the agreement plot, suggesting that in such cases, the clinically defined SOZ, which is often utilized as an estimate of the EZ, may have been inaccurate since the outcome of these cases was Engel Classes III and IV. The SOZ localization accuracy before and after pseudo-HFO elimination and the SOZ localization improvement per subject are shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. This improvement was not statistically significant among different anatomical regions, including temporal and extratemporal cases (Supplementary Fig. S10). Moreover, we found that the agreement in SOZ accuracy between IOM and EMU recordings improved differently for the R and FR groups. The agreement was especially noteworthy within the FR group when removing the pseudo-events (Supplementary Fig. S7d, e).

HFO distribution, resection volume, and surgical outcome

We also contrasted the HFO distribution within the resection volume between two groups of patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes, as mentioned in ref. 13. In particular, we evaluated the relationship between HFOs and the surgical outcome of those cases who received resective and ablative surgeries. We focused on those subjects where resection and ablation of lesions had good outcomes (Group-1, Engel class I, II: 19 cases) and poor outcomes (Group-2, Engel class III, IV: 4 cases). Those cases who received responsive neurostimulation (RNS) and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) treatments were excluded from this analysis. In IOM theater (Fig. 4e), there was a noticeable but not significant difference in HFOs coming from operated sites in cases with good and bad outcomes (Group-1: 64%, Group-2: 33%, p = 0.09). In EMU recordings (Fig. 4f), the HFOs originating from the operated sites were significantly different between surgical outcomes (Group-1: 78%, Group-2: 26%, p = 0.02). Additionally, the validation of the surgical outcome and HFO area before and after pseudo-HFO elimination at the patient level is mentioned in Supplementary Table 1. The method used for this validation is detailed in the Supplementary Method.

Analysis of stereotyped HFOs in IOM and EMU

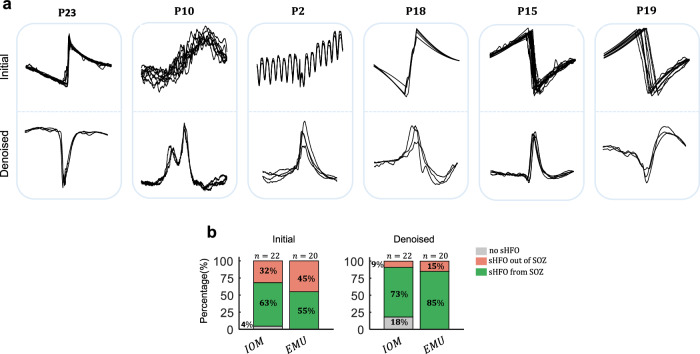

Pathological HFOs in IOM and EMU were assessed by capturing the sHFO characterized by repetitive waveform patterns39. Our initial results suggest that pseudo-HFO elimination is crucial in accurately identifying repetitive sHFO patterns, especially when dealing with heavily noisy and artifact-laden recordings. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 5a, when pseudo HFOs are not eliminated from the initial pool of IOM events, the algorithm detects clusters of stereotyped artifacts rather than real events with neural origin. Consequently, such noise and artifacts reduce the probability of detecting repetitive HFOs, as the noise may also exhibit repetitive patterns. After eliminating the pseudo-HFO events, we identified sHFO clusters with stereotyped waveform morphology consistently in both IOM and EMU datasets.

Fig. 5. sHFO analysis.

a Analysis of capturing repetitive events before (Initial) and after (Denoised) pseudo-HFO elimination. b Specificity of sHFO to find SOZ before (Initial) and after (Denoised) pseudo-HFO elimination. IOM intraoperative monitoring, EMU epilepsy monitoring unit, sHFO stereotyped high-frequency oscillation, SOZ seizure onset zone.

We conducted further analysis of the specificity of repetitive waveforms to the SOZ in both recording scenarios, both before and after pseudo-HFO elimination. We noticed that the SOZ prediction using sHFO was initially poor due to the presence of artifacts with repetitive waveshapes. However, after the elimination of pseudo-HFOs, remaining repetitive waveforms became highly specific to SOZ (Fig. 5b). In IOM, we found that 14/22 (63%) and 16/18 (88%) of subjects had their first cluster of stereotyped events from SOZ before and after pseudo-HFO elimination, respectively. Similarly, in EMU, we observed an increase in stereotyped events coming from SOZ, from 11/20 (55%) to 17/20 (85%), after eliminating the pseudo-HFOs (subjects with poor outcomes and no sHFO are excluded).

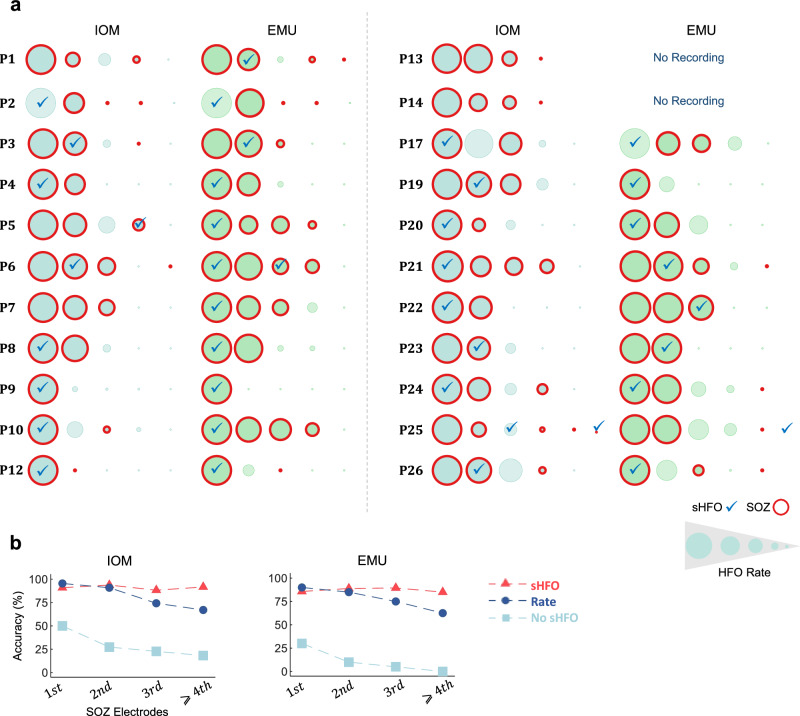

The relationship between sHFO and HFO channel density in IOM and EMU

Separately, we investigated how well the first cluster of sHFO and the rate of HFOs can help to find SOZ leads. First, we identified electrodes with the highest HFO rate and marked those where the primary cluster of sHFO first appeared (Fig. 6a). Then, we analyzed whether the first kth electrode with the highest rate of HFO and those with sHFO provided complementary information to locate the SOZ (Fig. 6b). Additional data is provided in Supplementary Fig. S11. We noticed that sHFO was not necessarily confined to the electrodes with the highest HFO rate. Additionally, when assessing the accuracy of identifying the SOZ using the first kth electrode with the highest HFO rate, we found an apparent decline in accuracy when relying solely on the HFO density. However, the detection of SOZ using sHFO reached a plateau when considering ≥2 electrodes. This observation is particularly valuable in those cases where no information from the SOZ is available, as there is typically no definitive guideline on how many electrodes with the highest rate should be considered as the SOZ. Nevertheless, since sHFO tends to pinpoint the primary SOZ site, it can serve as supplementary information in identifying the SOZ (more information on the comparison of sHFO and electrode density can be found in Supplementary Fig. S12).

Fig. 6. The comparison of the HFO electrode density and sHFO.

a Electrodes are sorted based on the min–max normalization rate of detected HFOs across subjects; sHFOs were marked with “✓” across all subjects in both IOM and EMU. b The accuracy of identifying the SOZ by looking at the first kth electrodes using rate (blue trace) and sHFO (red trace) in IOM and EMU. Additionally, subjects without sHFO at the first k electrodes are visualized with light blue traces. IOM intraoperative monitoring, EMU epilepsy monitoring unit, HFO high-frequency oscillation, sHFO stereotyped high-frequency oscillation, SOZ seizure onset zone.

Discussion

In the field of clinical neurology, HFOs of iEEG are considered to be a valuable biomarker for identifying the SOZ in patients with epilepsy47–49. During the electrode implantation procedure, which occurs prior to the EMU phase, the distribution of HFOs, if captured reliably, can provide prompt feedback to physicians regarding the locations of the SOZ. This feedback is crucial as it guides the subsequent phase of treatment—surgical resection which the previously identified epileptogenic tissue is surgically removed. However, noisy intraoperative environments and artifacts that mimic real-HFOs present challenges in utilizing intraoperative HFOs effectively22,28–30. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, an automatized intraoperative HFO detector that can reliably eliminate pseudo-HFOs has not yet been established. Most of the previously proposed approaches involve a two-step procedure in which the first step detects the initial pool of events. In the second step, experts visually inspect the candidate events to eliminate pseudo-HFOs solely relying on their expertise27,28,30,31,36,38. This painstaking and time-consuming visual artifact rejection process limits the clinical translation of intraoperative HFOs50.

To tackle this problem and evaluate the feasibility of early prediction of SOZ, we employed sparse coding fused with ensemble learning to automatically distinguish between real and pseudo-HFOs in heavily corrupted brief iEEG recordings. Using HFO events annotated by three experts, we learned dictionaries of waveform patches that can locally and effectively represent the real-HFO candidates but not the pseudo-ones. Earlier efforts employing sparse signal processing for classification found that such a biased dictionary design was also effective in the classification of acoustic signals and outperformed traditional balanced dictionaries51. We employed a cascaded residual-based learning architecture similar to ref. 43 that extracts distinct waveform patterns at each layer based on the energy content of the real-HFO events. We noticed that the first layer prioritizes atoms, to reconstruct the morphology of events typically occurring below 80 Hz with higher energy. As we progress to the subsequent layers, the framework predominantly focuses on learning atoms that can represent the residual of the previous layer. Consequently, the attention of the dictionary learning algorithm is directed to the higher frequencies with low energy due to the nature of iEEG and HFO events. This enabled capturing atoms that can represent R and FR events reaching up to 600 Hz.

We speculate that the attainment of a redundant set of learned atoms inheriting the HFO morphology and their sparse use in classification could potentially be linked to the cognitive mechanisms underlying human visual inspection, specifically in the context of discriminating real-HFOs from pseudo-ones. The sparse representation of visual stimuli and images with an overcomplete dictionary received much attention in computational neuroscience52,53 and machine learning54,55. Learned bases from the data have been shown to overlap with the receptive fields found in V1 of the visual cortex and mimic certain properties of visual area V252,53. Given that human experts can recognize the real and pseudo-HFO events visually by inspecting their raw waveform characteristics, we aimed to mimic this process by capturing the morphology of raw events at various scales and representing the candidate events with only a subset of them. These results by no means indicate that the system that we have developed replicates or fully explains visual judgment executed by the experts but aims to extract information from the raw data by focusing on morphology in various spectral scales.

It is well-established that anesthetics alter electrophysiological brain activities56–58. The use of anesthetics in IOM recordings is particularly relevant as the characteristics of HFOs might change when patients are on anesthetics during the surgery. More specifically, previous work has shown that agents like Propofol10,29,37,38, Sevoflurane31,35,59, and Ketamine60 can alter high-frequency activity. Therefore, the validity of detecting SOZ should take into consideration the anesthetics and its potential effects on HFO characteristics. While patients were sedated during IOM and awake during EMU monitoring, a degree of similarity (cosθ = 0.92) in HFO spatial distribution was observed. Notably, after pseudo-HFO elimination, HFO rates within and outside the SOZ exhibited a similar trend, with lower rates observed in IOM than in EMU. This suggests a potential impact of sedation on HFO generation, independent of the SOZ. Given the variability in anesthetic agents used across patients (Supplementary Data 1), a definitive assessment of the influence of specific drugs on HFO characteristics remains challenging. Further controlled studies are necessary to elucidate the precise effects of sedation on HFO generation and distribution.

Earlier work suggested that there is an overlap between the spectral frequency of physiological and pathological HFOs61,62 and both R and FR can also be observed from normal brain tissue63,64. Despite these similarities, these events carry different levels of information. Rs are generally considered less pathological, whereas FRs are believed to be more linked to ictogenesis in prolonged EMU recordings8. Our observations in IOM recordings confirmed this hypothesis, as FRs displayed a higher specificity to the SOZ. Our findings indicate that the alignment of FR spatial distribution across channels between IOM and EMU exhibits more consistency (0.96) compared to R (0.92). Additionally, the accuracy of SOZ localization using FRs is more consistent between IOM and EMU () compared to Rs (, see Supplementary Fig. S7d, e). Considering the inherently pathological nature of FRs in contrast to Rs8 and the administration of anesthetic drugs during IOM, it seems that the spatial distribution of pathological events represented by FRs is less susceptible to the influence of anesthetic drugs than that of the Rs.

Apart from the artifacts, the clinical utilization of HFOs is often confounded by the presence of physiological HFOs recorded from non-epileptic regions such as motor, visual, and language regions65,66. To address this issue, in our earlier work39 we examined the homogeneous clusters of repetitive patterns, sHFOs, which are regarded as pathological due to their specificity to the SOZ. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that identified the existence of sHFOs in IOM recordings. While the likelihood of capturing sHFOs in IOM is lower than in EMU (four cases without sHFOs in IOM) recordings due to the short duration of IOM and higher background noise, our study found evidence of sHFOs in IOM, which were highly specific to the SOZ similar to the EMU. However, it is worth noting that the morphology of the initial repetitive clusters was different between the IOM and EMU recordings. Additionally, in some cases, the sHFOs in IOM originated from different contacts than EMU (four cases). One possible explanation for the different active sources of sHFOs in IOM and EMU is the effect of anesthetic drugs used during IOM procedures. Another potential factor may be the fluctuation of sHFOs over time, which could contribute to the observed differences between the two types of recordings.

It is also worth noting that, as most of the repetitive patterns emerge from the FR band, the initial dense cluster of repetitive patterns could be artifacts in the absence of pseudo-HFO elimination in IOM. Therefore, it is critical to consider pseudo-HFO elimination in the context of FR-tailored surgical intervention for patients with epilepsy.

We showed that (Fig. 6), the density of HFOs over electrodes and the most compact cluster of sHFO patterns can provide complementary information to identify the SOZ. Both in IOM and EMU, the contact with the highest rate of HFO was in the SOZ in 95.4% and 90% of the cases, respectively. However, when we evaluated the top four ranked contacts based on their rate, we observed a decrease in accuracy in both IOM and EMU (67.05% vs. 62.5%, respectively). In contrast, looking at the first kth electrode does not affect the accuracy of detecting SOZ through sHFO in both IOM and EMU. The accuracy of detecting SOZ through sHFO improved when taking into account the first two electrodes and eventually stabilized with the top-ranked four contacts in both IOM and EMU (93.7% and 89%, respectively). More importantly, while all subjects had sHFO in the EMU top-ranked four contacts, we noticed that 18% of the patients did not have any sHFO in IOM. Previous work has shown that the HFO rate might vary depending on the anatomical location of SOZ67 and fluctuate over time68. Moreover, the duration of intraoperative recordings is typically short, resulting in limited electrophysiological data available for analysis. Consequently, longer IOM recordings are needed to capture a large amount of HFOs to improve the detection of sHFOs.

The early identification of the SOZ is crucial for reducing the risks associated with prolonged epilepsy monitoring unit stays, which are five times higher in children than in adults69,70. Consequently, the development and deployment of computational intelligence tools, which are resilient against artifacts, are critical for the identification of pathological HFOs in heavily corrupted iEEG recordings assessed in the IOM and the translation of HFO spatio-spectral distribution into clinical decision-making. In this study, we present preliminary evidence for the development of an automated tool utilizing sparse signal processing, characterized by low computational complexity. As detailed in Supplementary Table 2, this method enables the processing of individual events within 120 ms using standard computer architecture. In the future, a real-time implementation of our framework could serve as a promising opportunity to leverage intraoperative HFOs as an early feedback modality for tailoring surgery and guiding electrode repositioning. This approach has the potential to significantly reduce the duration of prolonged EMU stays while mitigating the associated complications.

One potential future direction for this work is to address labeling errors of electroencephalographers. In this study, to minimize labeling errors of real and pseudo-HFOs, three independent experts engaged in the annotation process. They worked independently and without knowledge of each other’s decisions, reducing potential bias. Despite this rigorous process, we acknowledge that some labeling errors are inevitable due to the lack of clear definitions of HFOs and the training of experts in different environments. The binary classification method aims to replicate the majority vote of expert labels, indirectly managing labeling errors. Future studies may further reduce errors by involving more experts71 and examining intra-decision variability, assigning a probability to each event based on expert votes, and using a probabilistic classifier to explore events. This type of analysis in the future could help the classifier address labeling errors across experts.

Finally, in this early feasibility study, while our study group included an imbalanced distribution of patients with good () and poor () outcomes from resective/ablative surgeries for the training of the computational methods to remove pseudo-HFOs, there is evidence suggesting that the resection of HFO-generating areas correlates with favorable surgical outcomes (see Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 4e, f). Future studies involving a larger cohort of patients with both favorable and poor outcomes are needed to more comprehensively assess the clinical utility and translational potential of HFOs and associated denoising techniques in predicting the efficacy of surgical therapy.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We cordially give our thanks to all patients, the neurological teams at the University of Minnesota, Texas Children’s Hospital, and Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center, who made this research possible. We are also grateful for all the resources provided by TIMES at the University of Houston and Mayo Clinic Department of Neurosurgery. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s BRAIN Initiative under award number UH3NS117944 and grant R01NS112497 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. B.F.B. was supported by the Sundt fellowship of the Mayo Clinic Neurosurgery Department.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Maeike Zijlmans, Saeid Sanei and Johannes Sarnthein for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

Supplementary Data 2 enables the full replication of Figs. 2–5. This includes the PSD of the 64 learned atoms from IOM and EMU (Fig. 2), the confusion matrix for each subject (Fig. 3a), and the number of HFO, pHFO, R, and FR events across patients (Fig. 3b–e). It also provides the rate of HFOs across channels in IOM and EMU (Fig. 3f) and the cosine similarity between HFOs and their subgroups within subjects in both IOM and EMU (Fig. 3g, h). Additionally, it includes the SOZ accuracy from IOM and EMU data (Fig. 4a–d), the accuracy of HFO detection and clinical outcome prediction (Fig. 4e, f), and the number of sHFOs in each recording scenario used to replicate Fig. 5b. Further details can be found in each section of Supplementary Data 2. All electrophysiological data, including raw iEEG from both IOM and EMU scenarios used in this study, are available for download at the Data Archive for the BRAIN Initiative (DABI). If you have any questions, please contact the corresponding author (ince.nuri@mayo.edu).

Code availability

All codes used to generate the analysis results in this article, including the cascaded dictionary learning framework, ASLR code, feature extraction scripts, and classifier implementation, are deposited at both GitHub and Zenodo72.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-024-00654-0.

References

- 1.Wiebe, S., Blume, W. T., Girvin, J. P. & Eliasziw, M. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. New Engl. J. Med.345, 311–318 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wellmer, J. et al. Risks and benefits of invasive epilepsy surgery workup with implanted subdural and depth electrodes. Epilepsia53, 1322–1332 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenow, F. Presurgical evaluation of epilepsy. Brain124, 1683–1700 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cossu, M. et al. Stereoelectroencephalography in the presurgical evaluation of focal epilepsy: a retrospective analysis of 215 procedures. Neurosurgery57, 706–718 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zumsteg, D. & Wieser, H. G. Presurgical evaluation: current role of invasive EEG. Epilepsia41, S55–S60 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Urrestarazu, E., Chander, R., Dubeau, F. & Gotman, J. Interictal high-frequency oscillations (100–500 Hz) in the intracerebral EEG of epileptic patients. Brain130, 2354–2366 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel, J. Jr, Bragin, A., Staba, R. & Mody, I. High‐frequency oscillations: what is normal and what is not? Epilepsia50, 598–604 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staba, R. J., Wilson, C. L., Bragin, A., Fried, I. & Engel, J. Quantitative analysis of high-frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz) recorded in human epileptic hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. J. Neurophysiol.88, 1743–1752 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco, J. A. et al. Unsupervised classification of high-frequency oscillations in human neocortical epilepsy and control patients. J. Neurophysiol.104, 2900–2912 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zijlmans, M. et al. How to record high‐frequency oscillations in epilepsy: a practical guideline. Epilepsia58, 1305–1315 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boran, E., Stieglitz, L. & Sarnthein, J. Epileptic high-frequency oscillations in intracranial EEG are not confounded by cognitive tasks. Front. Hum. Neurosci.15, 613125 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buzsáki, G., Horváth, Z., Urioste, R., Hetke, J. & Wise, K. High-frequency network oscillation in the hippocampus. Science (1979)256, 1025–1027 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs, J. et al. High‐frequency electroencephalographic oscillations correlate with outcome of epilepsy surgery. Ann. Neurol.67, 209–220 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiyama, T. et al. Focal resection of fast ripples on extraoperative intracranial EEG improves seizure outcome in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia52, 1802–1811 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedele, T. et al. Resection of high frequency oscillations predicts seizure outcome in the individual patient. Sci. Rep.7, 13836 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haegelen, C. et al. High‐frequency oscillations, extent of surgical resection, and surgical outcome in drug‐resistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsia54, 848–857 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho, J. R. et al. Resection of individually identified high‐rate high‐frequency oscillations region is associated with favorable outcome in neocortical epilepsy. Epilepsia55, 1872–1883 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crépon, B. et al. Mapping interictal oscillations greater than 200 Hz recorded with intracranial macroelectrodes in human epilepsy. Brain133, 33–45 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner, A. B., Worrell, G. A., Marsh, E., Dlugos, D. & Litt, B. Human and automated detection of high-frequency oscillations in clinical intracranial EEG recordings. Clin. Neurophysiol.118, 1134–1143 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birot, G., Kachenoura, A., Albera, L., Bénar, C. & Wendling, F. Automatic detection of fast ripples. J. Neurosci. Methods213, 236–249 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amiri, M., Lina, J.-M., Pizzo, F. & Gotman, J. High frequency oscillations and spikes: separating real HFOs from false oscillations. Clin. Neurophysiol.127, 187–196 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedele, T. et al. Automatic detection of high frequency oscillations during epilepsy surgery predicts seizure outcome. Clin. Neurophysiol.127, 3066–3074 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, S. et al. Exploring the time–frequency content of high frequency oscillations for automated identification of seizure onset zone in epilepsy. J. Neural Eng.13, 026026 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besheli, B. F. et al. A sparse representation strategy to eliminate pseudo-HFO events from intracranial EEG for seizure onset zone localization. J. Neural Eng.19, 046046 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dümpelmann, M., Jacobs, J., Kerber, K. & Schulze-Bonhage, A. Automatic 80–250 Hz “ripple” high frequency oscillation detection in invasive subdural grid and strip recordings in epilepsy by a radial basis function neural network. Clin. Neurophysiol.123, 1721–1731 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fedele, T. et al. Prediction of seizure outcome improved by fast ripples detected in low-noise intraoperative corticogram. Clin. Neurophysiol.128, 1220–1226 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van’t Klooster, M. A. et al. Tailoring epilepsy surgery with fast ripples in the intraoperative electrocorticogram. Ann. Neurol.81, 664–676 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss, S. A. et al. Visually validated semi-automatic high-frequency oscillation detection aides the delineation of epileptogenic regions during intra-operative electrocorticography. Clin. Neurophysiol.129, 2089–2098 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss, S. A. et al. Accuracy of high-frequency oscillations recorded intraoperatively for classification of epileptogenic regions. Sci. Rep.11, 21388 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Klink, N. E. C. et al. High frequency oscillations in intra-operative electrocorticography before and after epilepsy surgery. Clin. Neurophysiol.125, 2212–2219 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orihara, A. et al. Validity of intraoperative ECoG in the parahippocampal gyrus as an indicator of hippocampal epileptogenicity. Epilepsy Res.184, 106950 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomschewski, A., Hincapié, A.-S. & Frauscher, B. Localization of the epileptogenic zone using high frequency oscillations. Front. Neurol.10, 94 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bénar, C. G., Chauvière, L., Bartolomei, F. & Wendling, F. Pitfalls of high-pass filtering for detecting epileptic oscillations: a technical note on “false” ripples. Clin. Neurophysiol.121, 301–310 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, S. et al. DC shifts, high frequency oscillations, ripples and fast ripples in relation to the seizure onset zone. Seizure77, 52–58 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orihara, A. et al. Effects of sevoflurane anesthesia on intraoperative high-frequency oscillations in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure82, 44–49 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Klink, N. E. C. et al. Can we use intraoperative high‐frequency oscillations to guide tumor‐related epilepsy surgery? Epilepsia62, 997–1004 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inada, T. et al. Effects of a stable concentration of propofol on interictal high‐frequency oscillations in drug‐resistant epilepsy. Epileptic Disord.23, 299–312 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zijlmans, M. et al. Epileptic high‐frequency oscillations in intraoperative electrocorticography: the effect of propofol. Epilepsia53, 1799–1809 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu, S. et al. Stereotyped high-frequency oscillations discriminate seizure onset zones and critical functional cortex in focal epilepsy. Brain141, 713–730 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engel, J. et al. Presurgical evaluation for partial epilepsy. Neurology40, 1670–1670 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henry, T. R., Ross, D. A., Schuh, L. A. & Drury, I. Indications and outcome of ictal recording with intracerebral and subdural electrodes in refractory complex partial seizures. J. Clin. Neurophysiol.16, 426 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Besheli, B. F. et al. Elimination of pseudo-HFOs in iEEG using sparse representation and Random Forest classifier. In 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 4888–4891 (IEEE, 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Zhang, T. & Porikli, F. Cascade residuals guided nonlinear dictionary learning. Comput. Vis. Image Underst.173, 86–97 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aharon, M., Elad, M. & Bruckstein, A. K-SVD: an algorithm for designing overcomplete dictionaries for sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process.54, 4311–4322 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Besheli, B. F. et al. Averaged sparse local representation for the elimination of pseudo-HFOs from intracranial EEG recording in epilepsy. In 2023 11th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

- 46.Dimakopoulos, V. et al. Blinded study: prospectively defined high-frequency oscillations predict seizure outcome in individual patients. Brain Commun.3, fcab209 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dümpelmann, M., Jacobs, J. & Schulze‐Bonhage, A. Temporal and spatial characteristics of high frequency oscillations as a new biomarker in epilepsy. Epilepsia56, 197–206 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobs, J. & Zijlmans, M. HFO to measure seizure propensity and improve prognostication in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr.20, 338–347 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cimbalnik, J., Kucewicz, M. T. & Worrell, G. Interictal high-frequency oscillations in focal human epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol.29, 175–181 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zweiphenning, W. et al. Intraoperative electrocorticography using high-frequency oscillations or spikes to tailor epilepsy surgery in the Netherlands (the HFO trial): a randomised, single-blind, adaptive non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol.21, 982–993 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ince, N. F., Goksu, F. & Tewfik, A. H. Subset selection from biased dictionaries for impact acoustic classification. In 2008 16th European Signal Processing Conference 25–29 (IEEE, Lausanne, 2008).

- 52.Olshausen, B. A. & Field, D. J. Emergence of simple-cell receptive field properties by learning a sparse code for natural images. Nature381, 607–609 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olshausen, B. A. & Field, D. J. Sparse coding with an overcomplete basis set: a strategy employed by V1? Vision Res.37, 3311–3325 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ng, A. Sparse Autoencoder (2011).

- 55.Wright, J., Yang, A. Y., Ganesh, A., Sastry, S. S. & Ma, Y. Robust face recognition via sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.31, 210–227 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Purdon, P. L. et al. Electroencephalogram signatures of loss and recovery of consciousness from propofol. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA110, E1142–E1151 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mukamel, E. A. et al. A transition in brain state during propofol-induced unconsciousness. J. Neurosci.34, 839–845 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian, F. et al. Characterizing brain dynamics during ketamine-induced dissociation and subsequent interactions with propofol using human intracranial neurophysiology. Nat. Commun.14, 1748 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burelo, K. et al. A spiking neural network (SNN) for detecting high frequency oscillations (HFOs) in the intraoperative ECoG. Sci. Rep.11, 6719 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nottage, J. F. et al. The effect of ketamine and d-cycloserine on the high frequency resting EEG spectrum in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berlin)240, 59–75 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alkawadri, R. et al. The spatial and signal characteristics of physiologic high frequency oscillations. Epilepsia55, 1986–1995 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frauscher, B. et al. High‐frequency oscillations in the normal human brain. Ann. Neurol.84, 374–385 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagasawa, T. et al. Spontaneous and visually driven high‐frequency oscillations in the occipital cortex: intracranial recording in epileptic patients. Hum. Brain Mapp.33, 569–583 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cimbalnik, J. et al. Physiological and pathological high frequency oscillations in focal epilepsy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol.5, 1062–1076 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sinai, A. et al. Electrocorticographic high gamma activity versus electrical cortical stimulation mapping of naming. Brain128, 1556–1570 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsumoto, A. et al. Pathological and physiological high-frequency oscillations in focal human epilepsy. J. Neurophysiol.110, 1958–1964 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Struck, A. F., Cole, A. J., Cash, S. S. & Westover, M. B. The number of seizures needed in the <scp>EMU</scp>. Epilepsia56, 1753–1759 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gliske, S. V. et al. Variability in the location of high frequency oscillations during prolonged intracranial EEG recordings. Nat. Commun.9, 2155 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jobst, B. C. & Cascino, G. D. Resective epilepsy surgery for drug-resistant focal epilepsy. JAMA313, 285 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryvlin, P., Cross, J. H. & Rheims, S. Epilepsy surgery in children and adults. Lancet Neurol.13, 1114–1126 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spring, A. M. et al. Generalizability of high frequency oscillation evaluations in the ripple band. Front. Neurol.9, 510 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fazli Besheli, B. InceLab/IOM-HFO: Version 1.0—Initial Release of Cascaded Residual-Based Dictionary Learning Framework. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.13820227 (2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary Data 2 enables the full replication of Figs. 2–5. This includes the PSD of the 64 learned atoms from IOM and EMU (Fig. 2), the confusion matrix for each subject (Fig. 3a), and the number of HFO, pHFO, R, and FR events across patients (Fig. 3b–e). It also provides the rate of HFOs across channels in IOM and EMU (Fig. 3f) and the cosine similarity between HFOs and their subgroups within subjects in both IOM and EMU (Fig. 3g, h). Additionally, it includes the SOZ accuracy from IOM and EMU data (Fig. 4a–d), the accuracy of HFO detection and clinical outcome prediction (Fig. 4e, f), and the number of sHFOs in each recording scenario used to replicate Fig. 5b. Further details can be found in each section of Supplementary Data 2. All electrophysiological data, including raw iEEG from both IOM and EMU scenarios used in this study, are available for download at the Data Archive for the BRAIN Initiative (DABI). If you have any questions, please contact the corresponding author (ince.nuri@mayo.edu).

All codes used to generate the analysis results in this article, including the cascaded dictionary learning framework, ASLR code, feature extraction scripts, and classifier implementation, are deposited at both GitHub and Zenodo72.