ABSTRACT

Bilingual schools have more hours and high levels of academic demands. Aims: To compare the degree of dental wear and frequency of severe wear facets between children from public rural schools (RG) and children from private bilingual schools in Buenos Aires City (PG). To compare the presence of facets to parents’ reports on bruxism and their opinion on the importance to health of bruxism and snoring.

Materials and Method

The sample (n=90) consisted of 5- and 10-year-old children. Their parents/ guardians were asked to complete a structured questionnaire on bruxism and snoring. Children’s degrees of dental wear on primary incisors, canines and molars were identified and recorded. The data were analyzed statistically.

Results

The relative risk of wear between PG and RG was 1.82. Bruxism and snoring were reported by 22.9% of the parents/guardians of 5-year-olds and 8.8% of the parents/ guardians of 10-year-olds. In 10-year-olds, significant differences were found between RG and PG for canine wear degree 3 (p=0.01).

Conclusions

Children from highly demanding schools presented more dental wear. Higher frequency of severe dental wear was observed in primary canines and molars late in the tooth replacement period regardless of whether sleep bruxism was reported. Parents/guardians from different social conditions considered that bruxism and snoring are important to health to similar degrees.

Keywords: bruxism, children, dental wear

RESUMEN

Las escuelas bilingües tienen mayor carga horaria y altos niveles de exigencia académica. Objetivos: Comparar en niños preescolares y escolares de escuela pública rural (GR) y de colegios privados bilingües de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires (GP) el grado de desgaste dentario y la frecuencia de facetas de desgaste severo. Comparar la presencia de facetas con el reporte de los padres sobre el bruxismo y su opinión sobre la importancia de bruxar y roncar.

Materiales y Método

Muestra (n=90) conformada con niños de 5 y 10 años, cuyos responsables completaron un cuestionario estructurado. Fueron registrados y analizados estadísticamente los grados de desgaste dentario en incisivos, caninos y molares primarios.

Resultados

El riesgo relativo de desgaste entre GP y GR fue 1,82. El 22,9% de los responsables de los niños de 5 años y el 8,8% de los de 10 años reportaron que bruxan y roncan. En relación a la muestra de 10 años, se hallaron diferencias significativas para caninos desgaste grado 3 entre GR y GP (p=0.01).

Conclusiones

Los niños de escuelas con alta exigencia presentaron más desgaste. Se observó mayor frecuencia de desgaste dentario severo en caninos y molares primarios al final del recambio dentario independiente al reporte de bruxismo nocturno. Los cuidadores de diferente condición social revelaron valoración semejante sobre la importancia en la salud del bruxismo y el ronquido.

Palabras clave: bruxismo, niños, desgaste dental

INTRODUCTION

At different times over the years, and according to different specialties, bruxism has been considered a habit, a parafunction, and a parasomnia (according to sleep medicine). In 2013, an international group of experts published a consensus with the aim of proposing a definition and diagnostic classification system for bruxism which could be adopted by re-searchers and clinical professionals. They defined bruxism as a repetitive jaw-muscle activity charac-terized by clenching or grinding teeth and/or thrust-ing the mandible. They distinguished two different circadian manifestations: sleep and awake bruxism. With regard to diagnostic criteria, they established the terms “possible” bruxism when it is self-re-ported, “probable” when complemented by clinical findings, and “definitive” when confirmed by stud-ies such as polysomnography and/or electromyog-raphy 1 . However, polysomnography and electromy-ography are expensive and invasive, and Berrozpe et al. consider them excessive for diagnosing para-somnias, which can usually be detected clinically 2 . In the same document, Lobbezoo et al. distinguish primary or idiopathic bruxism as being that which is not associated to medical comorbidities, and sec-ondary bruxism when it is related to psychosocial or medical conditions such as breathing-related sleep disorders, neurological problems, psychiatric condi-tions and drug or medication use 1 .

The multifactorial etiology of bruxism involves fac-tors related to the central nervous system and possible influence of socioenvironmental factors.

Sleep and awake bruxism are currently considered to be different muscular activities. Sleep bruxism may be rhythmic or non-rhythmic. It should be noted that in healthy individuals it should not be considered disorder, although in some situations, bruxism may be a risk behavior, and in other situations a protec-tive factor, mainly against sleep apneas. Individual diagnosis is therefore necessary 3 .

Most studies on children report prevalence of sleep bruxism (SB) as 14 to 36.8%. However, and given the difficulties in diagnosing awake bruxism (AB), its prevalence has been estimated only among adults as 5 to 31% 4 .

In a previous study on children of mean age 11 years, we found reports of 35.3% SB, 35.3% SB + AB, and 29.4% AB. Subjects with both types of bruxism had high emotional instability 5 , which is a personality trait involving anxiety, a high degree of worry, and distorted perception of negative situations, causing changes in neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, which are the main causes of bruxism 6-7 . Esparza and Rodríguez studied a sample of 6- to 11-year-old children by applying the Reynolds & Kamphaus Multidimensional Behavior Assessment Scale, concluding that academic demand is a factor associated to the presence of states of anxiety. Serra Negra et al. found higher prevalence of sleep bruxism in children from better socioeconomic con-ditions 7-8 .

With regard to wear, our findings in a previous study showed that primary tooth wear should be consid-ered according to age and series. The presence of exposed dentin at early ages could be considered as an indicator of parafunction 9 . In a recent study on 48 children, Martins et al. concluded that those with more severe facets have possible sleep and awake bruxism 10 .

The aims of this study were (a) to compare degree and frequency of severe wear facets in preschool-ers and schoolchildren from a half-day public rural school to those in children from a full-day private bilingual school who visit private pediatric dentistry practices in Buenos Aires City, and (b) to compare the presence of facets with parent/guardian-reported bruxism and opinion on the importance to health of bruxism and snoring.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

This was a cross-sectional study. It was approved by the FOUBA Ethics Committee (009/2022-CETICA FOUBA).

A structured questionnaire was answered on a volun-tary basis by parents/guardians of patients from pri-vate bilingual schools seeking care at two practices in Buenos Aires City (PG), and parents/guardians of children enrolled at a public rural school in Buenos Aires Province (RG). The questionnaire consisted of 3 items: reporting on bruxism, reporting on snor-ing, and providing an opinion on whether bruxism and snoring are important to the child’s health. The questionnaire had been used previously Fridman et al. in a study on degree of wear in children's teeth before and after completing the tooth replacement period 11 ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1. Form used for recording.

The sample consisted of 5-year-olds whose first permanent molars had not yet erupted and 10-year-olds with mixed dentition, whose parents/guardians provided consent. Data were collected from May to July 2023.

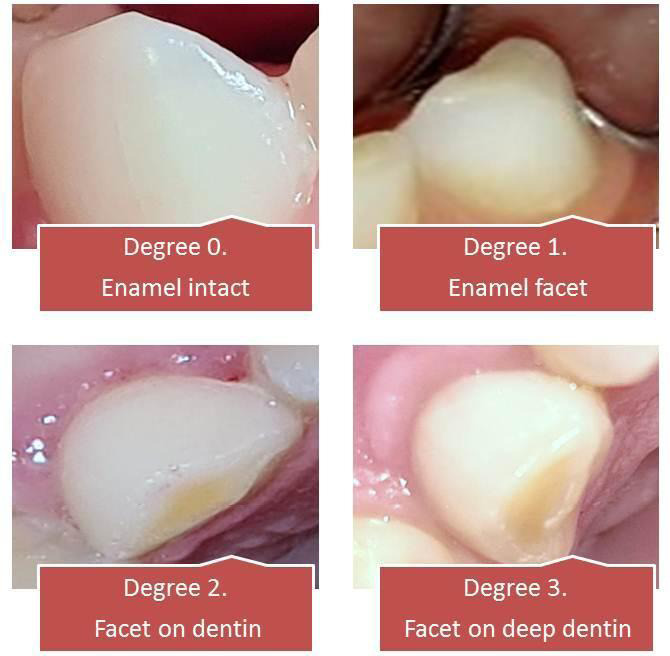

Three pediatric dentists, with Kappa concordance coefficient 0.92 for determining the Smith and Knight index, recorded degrees of wear for incisors, canines and primary molars in both groups for both 5-year-olds (PG-5 and RG-5) and 10-year-olds (PG-10 and RG-10) ( Fig. 2 ). Any children with multiple caries that interfered with the evaluation of wear in any of the tooth groups, children medicated with neuroleptics, or medically compromised children were excluded.

Fig. 2. Degrees of wear according to Smith and Knight’s Index.

Data were analyzed using R software ( https://www.R-project.org/ ) and VGAM package.

Relative risk (RR) was used to compare the presence of wear between PG and RG. The degree of wear for each tooth group (incisors, canines and molars) was compared between PG and RG for each age using ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds. Categorical variables were compared using the chi square test when at least 80% of the cells had an expected value greater than 5 and all of them had an expected value of at least 1.

RESULTS

Samples PG-5 and PG-10 consisted of 26 and 24 children, respectively, while RG-5 and RG-10 com-prised 20 children each.

-

The RR for presence of wear between PG and RG was 1.82.

For incisors, there were significant differ-ences in degree of wear between PG-5 and RG-5 (p = 0.002). In PG-5, all teeth had wear degree 1 or 2, while in RG-5, there was pre-dominance of teeth without wear or teeth with worn enamel only ( Table 1 ).

For molars, no significant difference was found in degree of wear between RG-5 and PG-5 (p = 0.1863). In both groups, there was predominance of unworn teeth, followed by teeth with wear degree 1. At age 10 years, the differences were significant (p = 0.004), with predominance of teeth with wear degree 1 in PG-10, and unworn teeth in RG-10 ( Table 3 ).

Among parents/guardians, 22.9% reported that 5-year-olds presented bruxism and snoring, 8.8% reported that 10-year-olds did so, and 10.4% said they did not know.

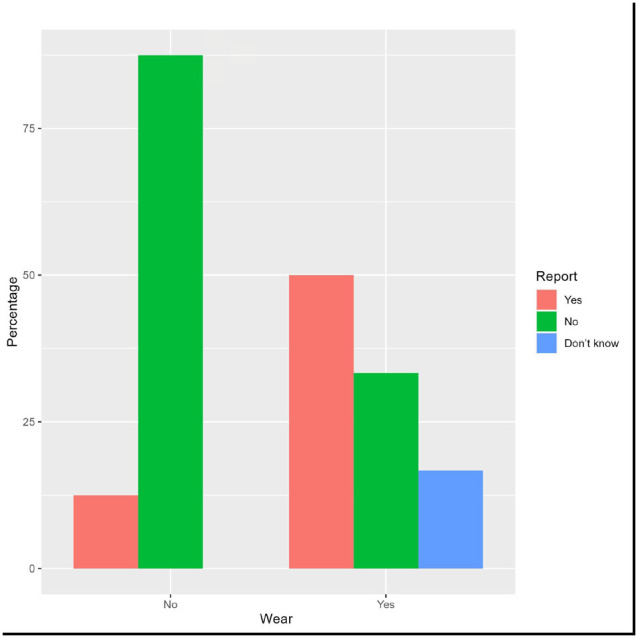

There was no difference in reported grinding between groups with or without tooth wear in RG at both ages (RG-5 p = 0.068, RG-10 p = 0.582). It was not possible to analyze this in PG because all the children presented facets. Fig. 3 , 4, 5 and 6 show the association between wear recorded by dentists and tooth grinding reported by par-ents/guardians in the four subgroups.

There was no difference between PG and RG regarding the importance assigned by parents/ guardians to bruxism (p = 0.58) or snoring (p = 0.68).

-

The frequencies of degree 3 facets were: 30.4%

For canines, there were significant differenc-es at both ages (p < 0.001), with lower degrees of wear in RG ( Table 2 ). for canines and 9.1% for molars in PG-10, and 5% for incisors in RG-5. No severe wear was re-corded in the other groups. Fisher’s test showed significant differences between RG-10 and PG-10 for canines (p=0.01), and non-significant differences between RG-5 and PG-5 for incisors (p=0.43), and between RG-10 and PG-10 for molars (p=0.50).

Table 1. Percentages of different degrees of incisor wear in both groups.

| Incisor wear | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Group | N | G0 % | G1 % | G2 % | G3 % |

| 5 years (p= 0.02) | PG | 26 | 0 | 65.4 | 34.6 | 0 |

| RG | 20 | 45 | 50 | 0 | 5 | |

Table 3. Percentages of different degrees of molar wear in both groups at ages 5 and 10 years.

| Molar wear | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Group | N | G0 % | G1 % | G2 % | G3 % |

| 5 years (p = 0.1863) | PG | 26 | 50 | 42.3 | 7.69 | 0 |

| RG | 20 | 70 | 25 | 5 | 0 | |

| 10 years (p = 0.004) | PG | 24 | 9.09 | 54.5 | 27.3 | 9.09 |

| RG | 20 | 52.9 | 35.3 | 11.8 | 0 | |

Fig. 3. Comparison of tooth grinding reported by parents/ guardians of rural school 5-year-olds with and without wear.

Table 2. Percentages of different degrees of canine wear in both groups at ages 5 and 10 years. Canine wear.

| Canine wear | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Group | N | G0 % | G1 % | G2 % | G3 % |

| 5 years (p < 0.001) | PG | 26 | 7.69 | 34.6 | 57.7 | 0 |

| RG | 20 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 years (p < 0.001) | PG | 24 | 0 | 8.70 | 60.9 | 30.4 |

| RG | 20 | 50 | 10 | 40 | 0 | |

Fig. 4. Tooth grinding reported by parents of bilingual school 5-year-olds with wear. In this group, all the children presented wear.

Fig. 5. Comparison of tooth grinding reported by parents/ guardians of rural school 10-year-olds with and without wear.

Fig. 6. Tooth grinding reported by parents of bilingual school 10-year-olds with wear. In this group, all the children presented wear.

DISCUSSION

The ages included in the sample were selected be-cause preschoolers (5-year-olds) are frequently reported on, and 10-year-olds have mixed dentition, so it is still possible to evaluate present primary teeth. The decision to compare children according to schooling type arose from the marked socioenviron-mental differences observed between sites located less than 100 kilometers away from each other. The rural schoolchildren live in the district Exaltación de la Cruz, Buenos Aires Province, where over 95% of the population consists of rural workers. In con-trast, the children from private bilingual schools have long days at highly academically demanding schools, urban family habits and health insurance. Bulanda et al. emphasize that socioeconomic and cultural features may be associated with the onset of sleep bruxism, which occurs more frequently in children from families with higher socioeconomic level. This might be related to the greater number of duties and demands these children have compared to children from poor environments. It is consis-tent with the findings on dental wear in the current study 12 . Different authors consider that SB is related to stress, anxiety, and behavioral and personality disor-ders, among others, as a result of serotonin and do-pamine release which increases brain activity, heart rate and muscle tone, thereby affecting sleep quali-ty. There is also an association between obstructive sleep apnea and bruxism, and it is currently believed that bruxism may be a protective factor that main-tains airway patency, which is why snoring has been investigated 12 .

Awake bruxism is associated to the inability to express emotions and to states of anxiety 13 . The current

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Gladys Banegas for collecting data from the rural school.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg J, Glaros AG, Kato T, Koyano K, Lavigne GJ, de Leeuw R, Manfredini D, Svensson P, Winocur E. Bruxism defined and graded: an international consensus. Oral Rehabil . 2013 Jan;40(1):2–4. doi: 10.1111/joor.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berrozpe EC, Folgueira A, Gonzalez Cardozo A, Ponce de León M, Valiensi SM. Polisomnografía nocturna y test múltiple de latencias del sueño. Nociones básicas e indicaciones. Guía práctica. Grupo de sueño - Sociedad Neu-rológica Argentina. Neurolarg . 2023;15(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuarg.2012.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Restrepo C, Manfredini D, Castrillon E, Svensson P, Santamaría A, Alvarez C, Manrique R, Lobbezoo F. Diagnostic accuracy of the use of parental-reported sleep bruxism in a poly somnographic study in children. Int J Paediatr Dent . 2017 Sep;27(5):318–32. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wetselaar P, Vermaire EJH, Lobbezoo F, Schuller AA. The prevalence of awake bruxism and sleep bruxism in the Dutch adult population. J Oral Rehabil . 2019;46:617–623. doi: 10.1111/joor.12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortese SG, Guitelman I, Biondi, AM. Cortisol salival en niños con y sin bruxismo. Rev Odontopediatr Lati-noam. [Internet] . 2021;9(1) doi: 10.47990/alop.v9i1.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Rabasca A. Cuestionario “Big Five” de personalidad para niños y adolescentes. Manual . TEA Ediciones; Madrid: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esparza N, Rodríguez MC. Factores contextúales del desarrollo infantil y su relación con los estados de ansiedad y depresión. Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología . 2009;5(1):47–64. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=s-ng=es [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serra-Negra JM, Paiva SM, Seabra AP, et al. Prevalence of sleep bruxism in a group of Brazilian schoolchildren. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent . 2010 Aug;11(4):192–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03262743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortese SG, Biondi AM, Oliver LM. Desgaste Incisal y Oclusal como Indicador de Patología parafuncional en Dentición Primaria. Bol. Asoc. Argent. Odontol. Niños . 2005;34(4):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martins IM, Alonso LS, Vale MP, Abreu LG, Serra-Negra JM. Association between the severity of possible sleep brux-ism and possible awake bruxism and attrition tooth wear facets in children and adolescents. Cranio . 2022 Jul;25:1–7. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2022.2102708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fridman DE, Biondi AM, Cortese SG. Grado de desgaste dentario en piezas primarias antes y al finalizar el recambio ; LV Reunión anual de la Sociedad Argentina de Investigación Odontológica; Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2022; Disponible en: https://saio.org.ar/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/LibroRRAASAIO2022_v3.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulanda S, Ilczuk-Rypula, D, Nitecka-Buchta A, et al. Sleep Bruxism in Children: Etiology, Diagnosis and Treatment—A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health . 2021;18:9544. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poojary B, Kanathila H, Pangi A, Doddamani M. Diagnosis and treatment of bruxism: Concepts from past to present. International Journal of Applied Dental Sciences . 2018;4(1):290–295. https://www.oraljournal.com/pdf/2018/vol4issue1/PartE/4-1-44-680.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares JP, Moro J, Massignan C, Cardoso M, Serra-Ne-gra JM, Maia LC, Bolan M. Prevalence of clinical signs and symptoms of the masticatory system and their associ-ations in children with sleep bruxism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev . 2021 Jun;57:101468. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg J, Raphael KG, Wetselaar P, Glaros AG, Kato T, Santiago V, Winocur E, De Laat A, De Leeuw R, Koyano K, Lavigne GJ, Svensson P, Manfred-ini D. International consensus on the assessment of brux-ism: Report of a work in progress. J Oral Rehabil . 2018 Nov;45(11):837–844. doi: 10.1111/joor.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]