Abstract

Purpose

To highlight the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab (TCZ) in Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) combined with ocular myasthenia gravis (OMG) patients refractory to steroids and cholinesterase inhibitor (CEI).

Methods

This was retrospective case series. We reviewed the health records of patients with GO combined with OMG, ten of whom were refractory to corticosteroids and CEI treatment and received intravenous injection of TCZ. Ten patients were treated with four injections of TCZ (intravenously, 8 mg per kilogram of body weight, once a month). We analyzed the efficacy and safety of TCZ treatment for this subset of patients with GO and OMG.

Results

The main outcomes including quality of life questionnaire in Graves’ orbitopathy (GO-QoL) score, Clinical Activity Score (CAS), Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living profile (MG-ADL) score, proptosis, diplopia and ptosis were assessed at 3 time points: “Baseline” (before the TCZ injection), “4th month” (after fourth time TCZ injection), “Follow up” (Last follow-up). Comparing parameters at 4th month vs. at baseline, all indicators improved at 4th month including GO-QoL score of visual functioning subscale (82.29 ± 13.71 vs. 35.98 ± 20.66, P < 0.001), GO-QoL score of the appearance subscale (80 ± 8.75 vs. 40.63 ± 17.95, P < 0.001), CAS (1.3 ± 0.46 vs. 4.5 ± 0.81, P < 0.001), MG-ADL (2.5 ± 1.56 vs. 5.11 ± 1.14, P < 0.001). Furthermore, proptosis decreased from 19.73 ± 2.84 to 17.93 ± 2.26 mm at 4th month (P < 0.0001). Diplopia and ptosis were also resolved at 4th month. After following up for a minimum of 11 months, the patients had no signs of relapse. In addition, we observed that all analyzed patients exhibited no significant drug reactions following the administration of TCZ.

Conclusion

Tocilizumab maybe a useful therapeutic option in refractory GO coexisting with OMG. However, considering the limitation of a retrospective study, short follow up period and small sample size of this study, randomized controlled studies are needed to validate our results.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12886-024-03779-x.

Keywords: Graves’ ophthalmopathy, Ocular myasthenia gravis, Tocilizumab, GO-QoL, MG-ADL, CAS

Introduction

Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) is a complex autoimmune inflammatory disorder [1] often accompanied by clinical features such as periorbital edema, eyelid retraction, proptosis, diplopia, vision loss [2, 3]. The pathophysiology of GO is an autoimmune process involving inflammation, fibrosis, increase in fatty and enlargement of extraocular muscles which leads to symptomatic diplopia [4–6]. GO is often associated with autoimmune diseases, including ocular myasthenia gravis (OMG), type 1 diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, and autoimmune adrenal insufficiency [7]. OMG is an autoimmune neuromuscular junction inflammatory disease caused by autoantibodies [8, 9], with major clinical symptoms of ptosis and diplopia due to extraocular muscles weakness.

Previous studies have shown that about 5% of MG patients are co-morbid with GO [10]. Many clinical features are mixed within the coexistence of GO and OMG, that make the ocular manifestations atypical. The diagnosis of this hybrid disease becomes difficult [11, 12]. Meanwhile, the treatment of patients with GO combined with OMG are more complicated than separate disease [6, 7, 11–13]. At present, the first-line treatment for GO is steroid pulse therapy (SPT), and the second-line treatment includes other immunosuppressive agents such as mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclosporine, azathioprine, teprotumumab, rituximab (RTX), tocilizumab (TCZ), and others [14]. The treatment of MG is based on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, glucocorticoids, RTX, immunosuppressants, plasma exchange therapy, and thymectomy [9, 15]. However, some patients show sub-optimal response or show high incidence of relapse under above standard therapy, especially those with coexistence of GO and OMG. For patients with GO and OMG who are resistant to standard treatment including glucocorticoid and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, remarkable and effective treatment options are lacking.

Since the publication of a consensus statement from the European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) [14], TCZ was given consideration as a second-line treatment for moderate-to-severe and active glucocorticoid-resistant GO [16, 17]. Meanwhile, recent research indicates that TCZ appears to be a safe and cost effective therapeutic option for patients with active, corticosteroid-resistant, moderate to severe Graves’ orbitopathy [18]. Furthermore, it has been reported that TCZ may have good therapeutic effects on very-late-onset myasthenia gravis [19]. Tocilizumab has the potential to be a valuable therapeutic option for such patients with acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive (AChR-Ab+) generalized myasthenia gravis [20]. However, there is limited evidence on the therapeutic effect of TCZ on patients with GO combined with OMG. Hence, this study aimed to describe the efficacy and safety of TCZ in treating patients with GO and OMG resistant to glucocorticoid.

Methods

Patients

We reviewed the electronic health records of all patients with GO seen at Department of Ophthalmology, Second Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University over the 2-year period from August 2020 to August 2022. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Second Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University (No. K202102-10) and carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For the purpose of this study, we retrospectively collected data from patients diagnosed with GO and OMG who had completed a full course of TCZ therapy (Fig. 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

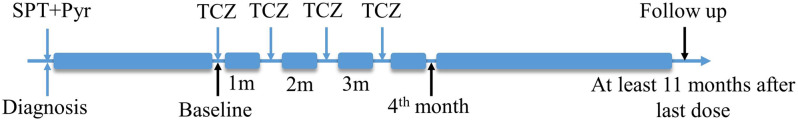

Fig. 1.

Treatment course for patients with GO combined with OMG. TCZ: Tocilizumab, SPT: Steroid Pulse therapy, Pyr: Pyridostigmine bromide

Patients’ documents recruitment criteria were as follows: (1) Being diagnosed with GO: the Clinical Activity Score (CAS, 7 points score) could be ≥ 3/7 or < 3/7, but in the latter case with extraocular muscle enlargement should have been identified using orbital computed tomography; (2) Being diagnosed with OMG: typical clinical symptoms (diplopia and ptosis), positive anti-AChR or muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase antibodies, and positive neostigmine test or ice-pack test; (3) Incomplete response (defined as a CAS improvement < 2) to at least 3 doses of 500 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone and at least 3 month treatment of pyridostigmine bromide; or recurrence of GO (defined as an increase in CAS > 1) and OMG after treatment with corticosteroids pulses and pyridostigmine bromide; (4) Having completed a full course of TCZ therapy.

Patients with any of the following conditions were excluded from the study: (1) A history of surgery; (2) A history of uremia, coronary heart disease, and other serious systemic diseases; (3) With serious infections (particularly HIV, Tuberculosis and hepatitis viruses); (4) Having received other biological agents during TCZ treatment; (4) Having suffered ocular trauma.

The TCZ intravenous infusion treatment protocol

The treatment regimen of TCZ was as follows: 8 mg of TCZ per kilogram of body weight was dissolved in 100 ml of normal saline and intravenously infused for 1.5 h using a filtered intravenous tubing system. A total of four infusions were administered during the entire treatment course, with an interval of one month (Fig. 1). During TCZ treatment, no other immunosuppressive agents were used, and methimazole was taken to regulate thyroid function according to the condition. Upon initiation of TCZ treatment, all patients strictly quit smoking. We followed up with the patients for at least 1 year from the last TCZ infusion time.

Safety regimen: We implemented a comprehensive safety protocol to monitor and manage potential adverse reactions post-infusion (Supplementary 1). TCZ infusion was carried out when cardiac function, pulmonary function, blood composition, liver and kidney function indicators, coagulation tests were identified to be normal. If any serious complications occurred, medical attention would be sought in time, and TCZ would be stopped.

Outcome measures

The same ophthalmologist followed each patient throughout the study. The changes in MG-ADL score were used to evaluate the improvement in OMG symptoms. The MG-ADL score was evaluated at the baseline, the1st month (i.e., the time point of one month after the first infusion of TCZ), the 2nd month (i.e., the time point of one month after the second infusion of TCZ), the 4th month (i.e., the time point of one month after the fourth infusion of TCZ), and the Follow up (time point of final follow up) (Fig. 1). The CAS score and GO-QoL score were evaluated at the baseline, the 4th month, and the follow-up. The Gorman score was used to measure the improvement of diplopia. The degree of exophthalmos, blepharoptosis, and eyelid retraction was measured before and after TCZ treatment and at the follow-up. The therapeutic effect was quantitatively evaluated using the scales and was directly observed with the improvement of patient’s ocular symptoms.

The safety assessment of TCZ is conducted through comprehensive biochemical tests, cardiac-pulmonary function evaluations performed during the treatment period and follow-up stages. Additionally, the presence or absence of clinical symptoms in patients is monitored to determine the overall safety profile of the drug.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 software. Paired t-test was performed to compare two non-independent sample outcomes and the Friedman test was performed to compare the results of multiple non-independent samples. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics of patients with GO concurrent with OMG

Demographic and clinical data of patients are shown in Table 1. 10 patients (5 males and 5 females) were recruited in this study. The median age was 34.5 years (range 15–67). The median GO duration was 9 months (within the range of 4 months–8 years). The median MG duration was 4.5 months (range 4 months–40 years). The median hyperthyroidism duration was 10.5 months (range 4 months–8 years). Nine patients took methimazole to maintain normal thyroid function, of which only one patient received I131 treatment. The abnormal baseline value of thyroid function is shown in Table 1. All patients had positive AChR antibody test results. 10/10 patients (100%) were tested positive in the neostigmine test, but only 3/10 patients (33.3%) were tested positive for the ice-pack test. None of the patients had a history of surgery. 9/10 patients had ptosis (at least one eyelid). 10/10 patients had diplopia due to eye movement disorder or with enlarged extraocular muscles through imaging examination. All patients received steroid pulse therapy (SPT) and pyridostigmine bromide before TCZ treatment, and two patients were given Rituximab intravenously in combination with SPT and pyridostigmine bromide. There was no obvious therapeutic effect of the therapies in these patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at baseline

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 | Patient 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | M | F | M | F | F | F | M | M | M |

| Age(years) | 15 | 19 | 20 | 34 | 27 | 35 | 48 | 67 | 55 | 40 |

| Duration of MG | 13y | 8y | 4 m | 4 m | 4 m | 9 m | 4 m | 40y | 4 m | 5 m |

| Duration of GO | 3y | 8y | 4 m | 5 m | 4 m | 9 m | 1y | 4 m | 9 m | 1y |

| Duration of Hyperthyroidism (years) | 3y | 8y | 4 m | 1y | 4 m | 9 m | 5y | 4 m | 9 m | 1y |

| Antibody status | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ | Anti-AchR+ |

| Thymoma | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| History of surgery | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Comorbidities | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Hypertension 30y | N | N |

| Neostigmine test | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Ice pack test | (-) | (-) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (+) |

| Abnormal value of thyroid function test | Anti-TPO↑ | (-) | (-) | TSH↓TRAb↑ | TSH↓T3↑T4↑Anti-TPO↑ | (-) | Anti-TPO↑ | (-) | TSH↓TRAb↑ | Anti-TPO↑ |

| Hyperthyroidism treatment | Methimazole | Methimazole | Methimazole | I131 | Methimazole | Methimazole | Methimazole | Methimazole | Methimazole | Methimazole |

| Previous treatment | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr | SPT + Pyr |

| Smoking status | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Quit smoking for 20 years | N | N |

SPT: Steroid Pulse therapy; Pyr: Pyridostigmine bromide; N = none

Efficacy of TCZ in the treatment of patients diagnosed with GO concurrent with OMG

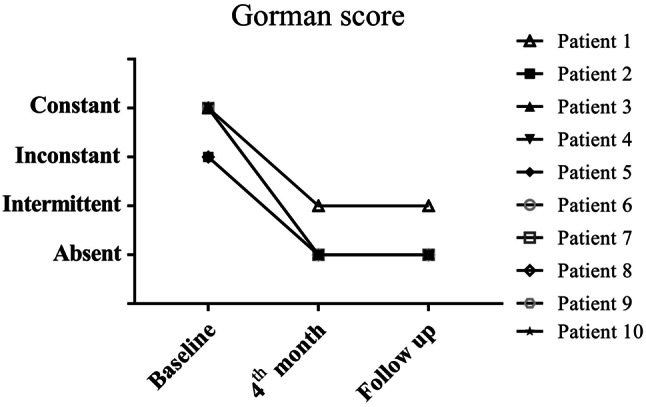

Gorman score for diplopia

We observed that 10/10 patients (100%) had diplopia at baseline. Patients with constant diplopia accounted for 8/10 (80%), and the other 2/10 patients exhibited inconstant diplopia. Imaging examination (CT) showed that 5 patients had different degrees of extraocular muscle enlargement. By 4 times TCZ treatment, diplopia and eye movement were significantly improved in all patients. The number of diplopia-absent patients increased to 9/10 (90%) at the 4th month (i.e., after the 4th TCZ treatment) and at the follow-up visits. The number of patients with intermittent diplopia remained at 1/10 after the full TCZ treatment. The number of patients with inconstant diplopia dropped from2/10 (20%) to 0 after the four TCZ treatments (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Assessment of diplopia according to Gorman score. The diplopia status of the patients were evaluated by Gorman score at the baseline, at the 4th month and at the follow-up

CAS score for GO

We evaluated the patients’ CAS scores in detail at baseline and after the full TCZ treatment. Comparing the number of patients with different symptoms at baseline, the 4th month, and the follow-up, the number of patients with relevant symptoms, including spontaneous retrobulbar pain, pain on attempted upward or downward gaze, redness of conjunctiva and eyelids, and swelling of caruncle or plica, eyelids, and conjunctiva (Table 2) decreased after full TCZ treatment. The CAS score after four TCZ treatments was decreased from 4.5 ± 0.81 to 1.3 ± 0.46 (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in CAS scores at the 4th month and at the final follow-up.

Table 2.

Detailed CAS score at different time points

| CAS | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 4th month | Follow-up | |

| Spontaneous retrobulbar pain, n (%) | 8(80%) | 1(10%) | 1(10%) |

| Pain on attempted upward or downward gaze, n (%) | 6(60%) | 1(10%) | 1(10%) |

| Redness of conjunctiva, n (%) | 8(80%) | 2(20%) | 2(20%) |

| Redness of eyelids, n (%) | 4(40%) | 1(10%) | 1(10%) |

| Swelling of caruncle or plica, n (%) | 4(40%) | 3(30%) | 2(20%) |

| Swelling of eyelids, n (%) | 6(60%) | 1(10%) | 1(10%) |

| Swelling of conjunctiva, n (%) | 9(90%) | 4(40%) | 4(40%) |

| CAS score (mean ± SD) | 4.5 ± 0.81 | 1.3 ± 0.46a | 1.2 ± 0.40a |

a Compared to baseline; Paired t-test P < 0.001

n = the number of patients

GO-QoL for GO

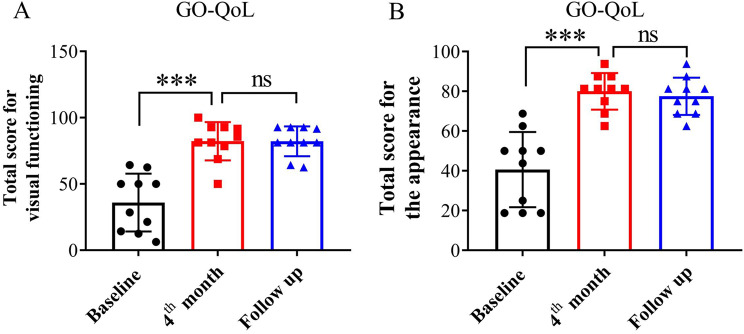

The GO-QoL score reflects the quality of life of patients before and after TCZ treatment [21]. At the baseline, the patients’ total score of visual functioning subscale was 35.98 ± 20.66. After TCZ treatment, the total score increased to 82.29 ± 13.71. The patients’ total score for the appearance subscale was 40.63 ± 17.95 at baseline. After the full course of TCZ treatment, the total score was 80 ± 8.75. Meanwhile, both patients’ scores at the 4th month and the follow-up showed no significant differences (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The subscales of GO-QoL evaluation for patients. The visual function score of GO-QoL were calculated at baseline, at the 4th month and at the follow-up (A). The appearance score of GO-QoL were calculated at baseline, at the 4th month and at the follow-up (B). ns (not significant) = P ≥ 0.05. *** Paired t-test P < 0.001

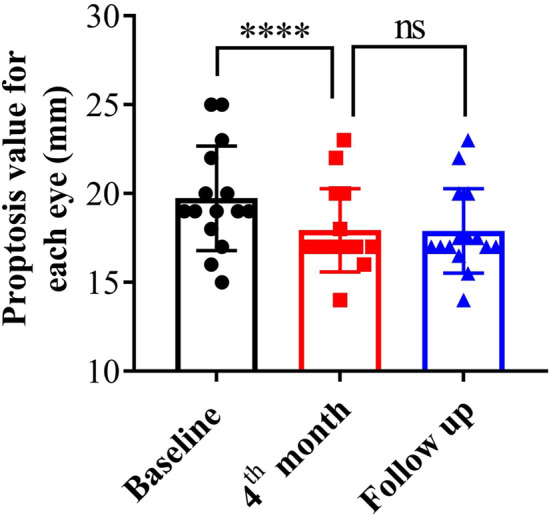

Degree of proptosis for GO

Comparing the protrusion degree of each eyeball before and after TCZ treatment, we found that the value of the protrusion degree was decreased from 19.73 ± 2.84 to 17.93 ± 2.26 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The eyeball protrusion did not change significantly at the final follow-up compared to that at the 4th month.

Fig. 4.

The degree of proptosis in patients at different time points. The proptosis values were measured by Hertel exophthalmometer at baseline, at the 4th month and at the follow-up. ns (not significant) = P ≥ 0.05. **** Paired t-test P < 0.0001

Degree of blepharoptosis and eyelid retraction

We measured palpebral fissure height before and after TCZ treatment and at follow-up. As shown in Table 3, some patients exhibited different degrees of ptosis and some patients had eyelid retraction before treatment. After four TCZ treatments, the height of the palpebral fissure returned to normal in all patients, including recovery of eyelid retraction and healing of ptosis. The palpebral fissures were highly stable at the follow-up, which is consistent with that at the fourth treatment of TCZ.

Table 3.

Height of palpebral fissure in patients with GO combined with OMG before and after TCZ treatment

| Baseline | 4th month | Final Follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of eyelid retraction (mm) | Height of palpebral fissure (mm) | Height of palpebral fissure (mm) | Height of palpebral fissure (mm) | |||||

| OD | OS | OD | OS | OD | OS | OD | OS | |

| Patient 1 | / | / | 5 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Patient 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Patient 3 | 2 | / | 12 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Patient 4 | / | / | 10 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Patient 5 | / | / | 8 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Patient 6 | / | / | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Patient 7 | / | / | 7 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Patient 8 | 1 | / | 10 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Patient 9 | / | / | 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Patient 10 | / | / | 5 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

MG-ADL score for OMG

We evaluated the MG-ADL score at the baseline, at the first, the second, the fourth TCZ treatment, and at the final follow-up. In the present study, none of the patients had systemic MG symptoms, and the symptoms were only manifested in diplopia and ptosis. The results showed that the total MG-ADL score gradually decreased from 5.11 ± 1.14 to 2.5 ± 1.56 gradually through the full course of TCZ treatment. (P < 0.001). The subscale MG-ADL (ptosis) and MG-ADL (diplopia) scores also decreased during the course of therapy (Table 4). At follow-up, the value of the MG-ADL score did not change significantly compared to that at the 4th month.

Table 4.

MG-ADL score of patients who received TCZ treatment

| Baseline | During treatment | Final Follow-up | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st month | 2nd month | 4th month | ||||

| MG-ADL score a | 5.11 ± 1.14 | 4.2 ± 1.33 | 3.1 ± 1.22 | 2.5 ± 1.56 | 2.3 ± 1.55 | 0.000 |

| MG-ADL score(diplopia) a | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 1.04 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.83 | 1 ± 0.77 | 0.002 |

| MG-ADL score(ptosis) a | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.46 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.75 | 1.1 ± 0.83 | 0.000 |

a Friedman test

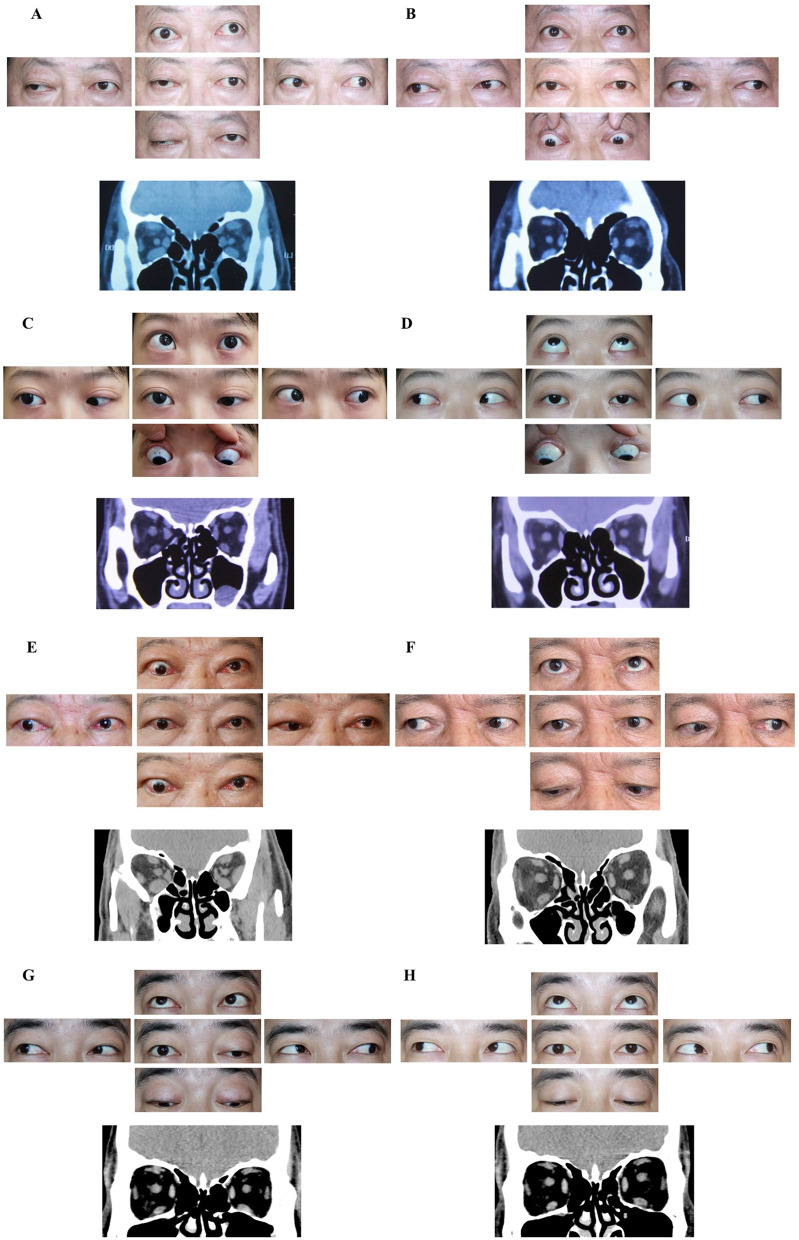

Appearance of patients

As shown in Fig. 5, GO symptoms of the patients’ eyes improved after the TCZ treatment, which was accompanied by an improvement in the OMG symptoms. The symptoms that improved included eye movement, ptosis, exophthalmos, conjunctival congestion, and edema.

Fig. 5.

Appearance of patients before and after receiving TCZ treatment. Ocular local photographs of patients staring in different directions at baseline. Orbital and extraocular muscles images were captured by orbital computed tomography at baseline (A, C, E, G). Ocular local photographs of patients staring in different directions at the follow-up, and images of orbital and extraocular muscles at the follow-up (B, D, F, H)

Safety of TCZ in the treatment of patients diagnosed with GO concurrent with OMG

In this study, we included 10 patients who underwent treatment with TCZ. Throughout the treatment and follow-up phases, none of the patients exhibited any abnormal clinical symptoms. Additionally, the biochemical parameters of these patients showed minimal fluctuations, with no significant changes observed that would indicate clinical relevance.

Discussion

The coexistence of GO and OMG results in obscurity in some of the clinical manifestations or even their omission. GO causes inflammation and fibrosis of orbital connective tissues and extraocular muscles, leading to the upper eyelid retraction, exophthalmos and eye movement disorder. Neuromuscular junction autoimmune reactions cause muscle weakness and fatigue, leading to ptosis and eye movement disorder in OMG patients [12, 22]. When GO and OMG coexist, the typical symptoms become difficult to identify due to overlap of clinical manifestations, such as diplopia. It has been reported that the pathology of muscle tissue in patients with GO combined with OMG may be the result of the interaction between GO-related hypertrophy and MG-related atrophy [5]. These factors cause the delayed diagnosis of GO combined OMG disease. According to the 2020 MG guidelines, in the presence of clinical features, only one positive test, such as AChR antibody or neostigmine test, is required to diagnose MG [9]. In previous studies, diagnosis of GO combined with OMG was made based on thyroid function tests, CT, laboratory tests, and ocular symptoms [5, 6, 12, 23]. Similarly, we collected information on patients diagnosed with GO combined with OMG on the basis of clinical symptoms, laboratory results, and comprehensive imaging analysis (described in methods).

At present, there is no standard method for the treatment of GO combined with OMG. In some case reports, patients with MG combined with GO were treated with radioactive iodine therapy and pyridostigmine [23]. Independent treatments of GO and OMG conform to most strategies [6, 11]. Intravenous methylprednisolone in combination with oral mycophenolate sodium (or mofetil) represents the first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe and active GO [14]. Immunosuppressants and inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase are the preferred treatments for OMG patients [9]. Although it does not affect the natural process of the disease, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as pyridostigmine remain as the first-line treatment for symptomatic relief [9]. In this study, the neostigmine test of the patients was positive, but the treatment with pyridostigmine was not satisfactory. Lack of obvious clinical improvement may be due to the influence of GO [11], or it may be due to the low sensitivity to medicine. According to reports, only about 50% of patients with OMG show an adequate response to pyridostigmine [24]. Glucocorticoid is a routine treatment for patients with GO and OMG, however, some patients were ineffective or easy to relapse. Less studies have addressed how to treat GO combined with OMG in the setting of glucocorticoids intolerance or where glucocorticoids therapy and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors fail.

TCZ is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting IL-6 receptors, and was given consideration as a second-line treatment for moderate-to-severe and active glucocorticoid-resistant GO. Meanwhile, TCZ has strong therapeutic potential for MG [19, 20]. In animal experiments, intraperitoneal injection of anti-IL-6 antibodies administered in MG rats remarkably ameliorated their clinical symptoms [25]. Meanwhile, it has been reported that in two patients with MG that was refractory to RTX, subsequent TCZ therapy ameliorated myasthenic symptoms without obvious adverse events [26].

In this study, we conducted a treatment efficacy analysis by reviewing cases of TCZ treatment for patients with poor or relapsed glucocorticoids treatment outcomes. Follow-up was performed at least 11 months after four TCZ treatments. The results showed that TCZ had good therapeutic effects on these patients and there was no recurrence at follow-up. Our results suggest that TCZ has a curative effect on the symptoms of GO and OMG in patients with the combined disease. TCZ treatment can significantly help patients with ocular symptoms recover and improve the quality of life in patients with GO, and it could greatly restore diplopia and reduce MG-ADL scores. The treatment regimen in the present study was four intravenous infusions of TCZ at a dose of 8 mg per kilogram of body weight each time, which is consistent with the basic strategy of TCZ treatment of GO [16]. No severe complications occurred in the patients in the present study.

IL-6 signaling is believed to be involved in the pathological process of anti-AchR antibody positive MG. It was reported that patients with anti-AchR antibody-positive MG exhibited elevated serum IL-6 levels, which decreased following immunosuppressant therapy [27, 28]. Previous studies indicated that the IL-6 serum concentration is related to the degree of activity of OMG [27, 29, 30]. Moreover, many studies have shown that IL-6 is produced and released by skeletal muscles in response to pressure signals [31, 32]. Overexpression of IL-6 increases the level of proteases in the muscles and induces the breakdown of muscle proteins [33]. Studies have shown that the autoantibody AChR Ab can act on muscle cells to increase IL-6 levels [34]. However, it is unclear whether muscle atrophy in OMG patients is related to the increase in IL-6 levels. IL-6 is also an important mediator of the inflammatory process in GO. Increased serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentrations have been reported in patients with thyroid destructive processes [35]. Furthermore, IL-6 is implicated to activate B and T cells and induce naïve T cells to differentiate into Th17 and Tfh cells [36, 37]. Th17, Tfh, and B cells play significant roles in the production of pathogenic autoantibodies, as well as inflammation in GO [38] and OMG [28]. TCZ could be regarded as an immunomodulator and anti-inflammatory agent that could modify the clinical course of GO combined with OMG by inhibiting IL-6 signaling.

The main limitations of our study are that it was a retrospective analysis, and the patient pool was small. Therefore, prospective studies in larger cohorts are necessary to validate our observations. In addition, none of the MG patients had any systemic symptoms in this study. Thus, the efficacy of TCZ for patients with GO combined with generalized MG should also be further studied. The autoimmune antibodies of patients in this study were all AChR antibody, and further study is needed for MG patients with other types of antibodies. Despite the absence of significant complications associated with tocilizumab (TCZ) in our study, previous research has indicated that TCZ can lead to hypofibrinogenemia [39]. This highlights the need for further investigation into the safety profile of TCZ, particularly through studies involving larger sample sizes to better understand its potential risks and ensure patient safety. In the present study, there was insufficient follow-up time for patients after four treatments, and further follow-up was needed to observe any recurrence of the disease. After the full course of TCZ treatment, we did not test the AChR antibody titer, so we cannot clarify the effect of TCZ treatment on the generation of these autoantibodies.

Conclusions

When GO is combined with OMG, the ocular symptoms are atypical, and attention should be paid to the thyroid function, imaging characteristics of extraocular muscles, laboratory-specific antibody levels, a neostigmine test, and an ice pack test to confirm the diagnosis. TCZ has a potential on the treatment of patients with GO coexisting OMG refractory to standard treatment. However, further randomized controlled studies and analysis of large samples are still needed to confirm our findings.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor. Yue Wang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiao Tong University) for the critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- MG-ADL

Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living profile

- MG

Myasthenia gravis

- GO

Graves’ ophthalmopathy

- TCZ

Tocilizumab

- CAS

Clinical Activity Score

- GO-QoL

quality of life questionnaire in Graves’ orbitopathy

Author contributions

Li YJ conceived and designed the study. Guo CJ contributed to primary manuscript writing and data analysis. Wang P and Ma N edited and revised the manuscript. Zhang SB, Cheng QL and Zhang Q collected the patients’ information and clinical data. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the [National Natural Science Foundation of China] under Grant [82301189]; [Second Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University] under Grant [2019JSY009]; [Department of Science and Technology of Shaanxi Province] under Grant [2023-YBSF-510].

Data availability

All data supporting the findings are contained within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Second Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University and carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Consent for publication

The written consents for publication have been obtained from all patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chenjun Guo and Ping Wang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Taylor PN, Zhang L, Lee RWJ, Muller I, Ezra DG, Dayan CM, Kahaly GJ, Ludgate M. New insights into the pathogenesis and nonsurgical management of Graves orbitopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(2):104–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonçalves AC, Silva LN, Gebrim EM, Monteiro ML. Quantification of orbital apex crowding for screening of dysthyroid optic neuropathy using multidetector CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(8):1602–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun R, Zhou HF, Fan XQ. Ocular surface changes in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Int J Ophthalmol. 2021;14(4):616–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim M, Chang JH, Lee NK. Quantitative analysis of extraocular muscle volume and exophthalmos reduction after radiation therapy to treat Graves’ ophthalmopathy: a pilot study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31(2):340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma R, Cheng Y, Gan L, Zhou X, Qian J. Histopathologic study of extraocular muscles in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy coexisting with ocular myasthenia gravis: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zouvelou V, Potagas C, Karandreas N, Rentzos M, Papadopoulou M, Zis VP, Vassilopoulos D. Concurrent presentation of ocular myasthenia and euthyroid Graves ophthalmopathy: a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(6):719–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bojikian KD, Francis CE. Thyroid Eye Disease and Myasthenia Gravis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2019;59(3):113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilhus NE. Myasthenia Gravis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2570–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayanaswami P, Sanders DB, Wolfe G, Benatar M, Cea G, Evoli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I, Kuntz NL, Massey J, et al. International Consensus Guidance for Management of Myasthenia gravis: 2020 update. Neurology. 2021;96(3):114–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartley GB. The epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of ophthalmopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;92:477–588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An R, Li Y, Yang B, Wang H, Xu Y. Rare co-occurrence of ocular myasthenia gravis and thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy (Ophthalmopathy) in an individual with hypothyroidism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claytor B, Li Y. Challenges in diagnosing coexisting ocular myasthenia gravis and thyroid eye disease. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(5):631–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang J, Qin C. Rare concurrent ocular myasthenia gravis and Graves’ ophthalmopathy in a man with Poland syndrome: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartalena L, Kahaly GJ, Baldeschi L, Dayan CM, Eckstein A, Marcocci C, Marinò M, Vaidya B, Wiersinga WM. The 2021 European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of Graves’ orbitopathy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021;185(4):G43–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(10):1023–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Moreiras JV, Gomez-Reino JJ, Maneiro JR, Perez-Pampin E, Romo Lopez A, Rodríguez Alvarez FM, Castillo Laguarta JM, Del Estad Cabello A, Gessa Sorroche M, España Gregori E, et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe corticosteroid-resistant Graves Orbitopathy: a Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;195:181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maldiney T, Deschasse C, Bielefeld P. Tocilizumab for the management of corticosteroid-resistant mild to severe Graves’ Ophthalmopathy, a report of three cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(2):281–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boutzios G, Chatzi S, Goules AV, Mina A, Charonis GC, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Tzioufas AG. Tocilizumab improves clinical outcome in patients with active corticosteroid-resistant moderate-to-severe Graves’ orbitopathy: an observational study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1186105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang TT, Wang ZY, Fan ZX, Yuan BY, Ma L, Lu JF, Liu PJ, He Y, Liu GZ. A pilot study on Tocilizumab in Very-Late-Onset Myasthenia Gravis. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:5835–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruan Z, Tang Y, Gao T, Li C, Guo R, Sun C, Huang X, Li Z, Chang T. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with refractory generalized myasthenia gravis. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30(6):e14793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawicka-Gutaj N, Bednarczuk T, Daroszewski J, Waligórska-Stachura J, Miśkiewicz P, Sowiński J, Bolanowski M, Ruchała M. GO-QOL–disease-specific quality of life questionnaire in Graves’ orbitopathy. Endokrynol Pol. 2015;66(4):362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grob D, Brunner N, Namba T, Pagala M. Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37(2):141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arcellana AES, Adiao KJB, Buenaluz-Sedurante M. Dual attack: targeting the rare co-occurrence of myasthenia gravis and Graves’ disease with radioactive iodine therapy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2021; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kupersmith MJ, Latkany R, Homel P. Development of generalized disease at 2 years in patients with ocular myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(2):243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aricha R, Mizrachi K, Fuchs S, Souroujon MC. Blocking of IL-6 suppresses experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun. 2011;36(2):135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson DI, Pirskanen R, Piehl F. Beneficial effect of tocilizumab in myasthenia gravis refractory to Rituximab. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(6):565–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uzawa A, Akamine H, Kojima Y, Ozawa Y, Yasuda M, Onishi Y, Sawai S, Kawasaki K, Asano H, Ohyama S, et al. High levels of serum interleukin-6 are associated with disease activity in myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol. 2021;358:577634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uzawa A, Kuwabara S, Suzuki S, Imai T, Murai H, Ozawa Y, Yasuda M, Nagane Y, Utsugisawa K. Roles of cytokines and T cells in the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;203(3):366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uzawa A, Kawaguchi N, Himuro K, Kanai T, Kuwabara S. Serum cytokine and chemokine profiles in patients with myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176(2):232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li H, Jia X, Zhang X, Xia Y, Wang Y, Fu L, Xiao C, Geng D. Increased expression of P2X7 receptor in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlates with clinical severity and serum levels of Th17-related cytokines in patients with myasthenia gravis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;157:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steensberg A. The role of IL-6 in exercise-induced immune changes and metabolism. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2003;9:40–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welc SS, Clanton TL. The regulation of interleukin-6 implicates skeletal muscle as an integrative stress sensor and endocrine organ. Exp Physiol. 2013;98(2):359–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsujinaka T, Fujita J, Ebisui C, Yano M, Kominami E, Suzuki K, Tanaka K, Katsume A, Ohsugi Y, Shiozaki H, et al. Interleukin 6 receptor antibody inhibits muscle atrophy and modulates proteolytic systems in interleukin 6 transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(1):244–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurer M, Bougoin S, Feferman T, Frenkian M, Bismuth J, Mouly V, Clairac G, Tzartos S, Fadel E, Eymard B, et al. IL-6 and akt are involved in muscular pathogenesis in myasthenia gravis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salvi M, Girasole G, Pedrazzoni M, Passeri M, Giuliani N, Minelli R, Braverman LE, Roti E. Increased serum concentrations of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor in patients with Graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(8):2976–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito R, Onodera H, Tago H, Suzuki Y, Shimizu M, Matsumura Y, Kondo T, Itoyama Y. Altered expression of chemokine receptor CXCR5 on T cells of myasthenia gravis patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;170(1–2):172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Wang W, Chen Y, Wei D. T helper type 17 cells expand in patients with myasthenia-associated thymoma. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang S, Zhang S, Huang Y, Wu Y, Lu Y, Zhong S, Liu X, Wang Y, Li Y, Sun J et al. Evidence for associations between Th1/Th17 hybrid phenotype and altered lipometabolism in very severe Graves Orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020; 105(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Martis N, Chirio D, Queyrel-Moranne V, Zenut MC, Rocher F, Fuzibet JG. Tocilizumab-induced hypofibrinogenemia: a report of 7 cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84(3):369–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings are contained within the manuscript.