Abstract

Background

Failure of systemic corticosteroid therapy is common in patients with newly diagnosed acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) above grade II. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been used as a tolerable and potentially effective second-line therapy for steroid-refractory aGVHD (SR-aGVHD); however, well-designed, prospective, controlled studies are lacking.

Methods

This multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, exploratory phase 2 study enrolled patients with SR-aGVHD above grade II from 7 centres. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive umbilical cord-derived MSCs or placebo added to one centre’s choice of second-line agents (except for ruxolitinib). The agents were infused twice weekly. Patients with complete response (CR), no response (NR), or progression of disease (PD) at d28 received 8 infusions, and those with partial response (PR) received the above infusions for another 4 weeks. The per-protocol population consisted of patients who received ≥ 8 infusions. The primary endpoint was the overall response rate (ORR, CR + PR) at d28, analyzed in the per-protocol and intention-to-treat populations.

Results

Seventy-eight patients (median age 38, range 13–62) were enrolled: 40 in the MSC group and 38 in the control. Patients in the MSC group received a median of 8 doses, with a median response time of 14 days. In intention-to-treat analysis, ORR at d28 was 60% for MSC group and 50% for control group (p = 0.375). The 2-year cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD was marginally lower in the MSC group than in the control (13.8% vs. 39.8%, p = 0.067). The 2-year failure-free survival was similar between the MSC and control groups (52.5% vs. 44.4%, p = 0.43). In per-protocol analysis (n = 62), ORR at d28 was significantly greater in the MSC group than in the control group (71.9% vs. 46.7%, p = 0.043). Among patients with gut involvement, ORR at d28 was significantly greater in the MSC group than in the control (66.7% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.031). The adverse events incidences were similar between groups.

Conclusions

In this exploratory study, there was no superior ORR at d28 demonstrated in the MSC group compared with the control. However, MSCs showed a gradual treatment effect at a median of 2 weeks. Patients who completed 8 infusions may benefit from adding MSCs to one conventional second-line agent, especially those with gut involvement. MSCs was well tolerated in patients with SR-aGVHD.

Trial registration

chictr.org.cn ChiCTR2000035740.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-024-03782-5.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Acute graft-versus-host disease, Steroid-refractory

Background

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) is a common complication after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) [1]. Systemic corticosteroids are considered the standard initial treatment for aGVHD [2–5]. However, steroid refractoriness occurs in more than 40% of patients and is associated with a dismal prognosis [6–8].

Ruxolitinib, an oral selective inhibitor of Janus kinase (JAK), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019, and the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) recommended it as a new standard for treating steroid-refractory aGVHD in 2024 [3, 9, 10]. However, it was not approved in China until April 2023, and exploring alternative second-line treatments other than immunosuppressants remains imperative in this field. In vitro, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown efficacy in the treatment of GVHD via their immunomodulatory effects, including the inhibition of effector T-cell activation, promotion of regulatory T-cell (Treg) formation, and induction of nitric oxide (NO) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) production [11]. Furthermore, MSCs facilitate the repair and regeneration of tissue damaged by GVHD [11, 12]. In 2004, Le Blanc et al. first rescued a patient with grade IV refractory aGVHD involving the gut and liver by infusing MSCs derived from the bone marrow [13]. The authors then conducted a phase 2 single-arm prospective study on steroid-refractory grade II-IV aGVHD using MSCs as a second-line treatment, and they yielded an overall response rate (ORR) of 70.9%. Since then, there has been a rapid increase in studies focusing on the use of MSCs for the treatment of steroid-refractory aGVHD. However, evidence from high-quality studies is still lacking. Kebriaei P et al. reported a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study in 2020, which revealed that the durable complete response (DCR) rate was 35% among patients who received bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) and 30% among controls (p = 0.42) [14]. This study exhibited heterogeneity in terms of stem cell source, patient age, GVHD prophylaxis regimen, and baseline second-line treatment, which may have affected the assessment of MSC efficacy. Zhao et al. reported an open-label, phase 3, randomized trial, and the results suggested that the ORR at day 28 was significantly greater in the BM-MSCs group than in the control group (82.8% vs. 70.7%, p = 0.043) [15]. Fu et al. conducted an open-label, phase 3, randomized trial and reported a significantly greater complete response (CR) rate at day 28 in patients who received umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) than in the control group (83.1% vs. 55.4%; p = 0.001) [16]. The shortcomings of the above two studies were the nonblinded and non-placebo-controlled trial design, which could introduce bias into the research findings.

Here, we report the results of a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial to explore the efficacy and safety of the human umbilical cord-derived MSC product (hUC-MSCs PLEB001) when added to one centre’s choice of second-line agent (except for ruxolitinib) for steroid-refractory aGVHD above grade II [17].

Methods

Study design

This exploratory study (Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ChiCTR2000035740) enrolled patients from 7 Chinese centres. In the double-blinded design, eligible patients were randomized at a 1:1 ratio into the MSC group or the control group. One centre’s choice of second-line agent (except for ruxolitinib) was used as baseline therapy for all patients with SR-aGVHD to avoid treatment vacancies in the control group. The study protocol and all amendments were reviewed and approved by an independent ethics committee. This trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration 2013 and Good Clinical Practice in clinical trials.

Patients

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients aged between 13 and 70 years; (2) patients with haematologic malignancies who received their first allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and developed SR-aGVHD above grade II; acute GVHD that occurred after donor lymphocyte infusion was also included; (3) patients able to be treated with the trial agent within 3 days after enrolment; and (4) the subjects or their legal representatives provided written informed consent prior to the trial.

The first-line treatment was the administration of 1–2 mg/kg/day methylprednisolone or an equivalent dose of steroids. The dose of steroids remained consistent within each centre. Steroid-refractory aGVHD was defined as patients who received first-line therapy and presented one of the following characteristics: disease progression after 3 days, failure to improve after 7 days, failure to achieve complete response after 14 days of steroid treatment (steroid resistance), or treatment failure during steroid tapering (i.e., an increase in the methylprednisolone dose to ≥ 2 mg/kg/day or equivalent or an inability to taper the dose to < 0.5 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone or equivalent for a minimum of 7 days), which was also referred to as steroid dependence.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) evidence from the 6 months preceding enrolment suggests that the patient has physiological conditions potentially interfering with trial evaluation or has life-threatening complications, including but not limited to uncontrolled infections, pulmonary arterial hypertension, severe heart failure classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV, acute myocardial infarction, refractory hypertension, creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min, severe hepatic veno-occlusive disease or sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; (2) gut transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy, or gastrointestinal infection; (3) active malignant solid tumours within 5 years prior to the study; (4) history of severe allergy to blood products or allogeneic proteins; or (5) mental or neurological disorders.

Randomization and double-blind design

A random number table was generated via the multicentre subblock randomization method in SAS (version 9.4) software. The patients were randomly allocated to the MSC group or the control group in the Central Randomization System of Clinical Information Management System (CIMS-CRS). A unique tracking number for investigational drug distribution was generated from the Alibaba Health precision traceability system. A light-protected infusion set was used to shield the investigational product. The central system was responsible for maintaining the records related to randomization. In principle, blinding should not be broken until all the subjects have completed the study and the database is locked.

Procedures

This study included a screening period of one week, a treatment period lasting 4 to 8 weeks, and a planned follow-up period of 12 months. Written informed consent was provided by patients or their legal representatives during the screening period. Cyclosporine A, mycophenolate mofetil, and short-term methotrexate were given for GVHD prophylaxis.

Patients in the MSC group received an intravenous infusion of MSCs (hUC-MSCs PLEB001) of 1.0 × 106 cells/kg twice a week for 4 weeks. The same frequency of placebo was administered to the control group. Patients who achieved CR, no response (NR), or progression of disease (PD) at d28 received 8 infusions, and those who achieved partial response (PR) at d28 received the above infusions for another 4 weeks.

One empirical second-line therapy, such as basiliximab or methotrexate (but not ruxotinib), was adapted for aGVHD according to the protocol of each centre. If aGVHD progresses rapidly, one or two additional second-line agents, as salvage treatment, could be given, and such cases were considered to have achieved NR at d28 and d56.

Patients were visited two or three times weekly within day 56, once weekly within day 100 after investigational product infusion, and the last two visits were at day 180 and day 360.

Investigational agents

hUC-MSCs PLEB001 (Platinumlife Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) are composed of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells obtained from human umbilical cord tissue (UCT) from healthy donors. After the arteries and veins were removed from the UCT, the remaining tissue and Wharton’s jelly were cut into small pieces. The minced UCT was subjected to enzymatic digestion to release the primary cells. Primary cells isolated from UCT (designated P0 cells) were cultured in serum-free medium (SFM) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and split when they reached 60 ~ 80% confluence. The passaged cells were plated and expanded in SFM at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and split when they reached 70 ~ 90% confluence. No cell enrichment or purification/selection was performed during the preparation process of this product. hUC-MSCs were frozen in the presence of cryopreservatives and stored in liquid nitrogen at P2, P4 and P5. P5 hUC-MSCs are formulated into final products, which should be stored at 2–8 °C.

hUC-MSCs express the cell surface markers CD73, CD90, CD105, CD29, CD44, CD10, and CD106. The cells are negative for CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD31, and HLA-DR. hUC-MSCs secrete prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), interleukin 6 (IL-6), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α) and can be induced by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) to express IDO. The cells demonstrated inhibitory effects in an in vitro T-cell proliferation assay.

The hUC-MSCs PLEB001 were packaged in a 50-ml light-protected bag containing 2.0 × 107 cells and cell preservation solution. The placebo is packaged in identical bags, each containing 50 ml of saline solution.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the ORR at d28, which was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved CR or PR without additional immunosuppressive agents for steroid-refractory aGVHD at d28 since randomization.

CR was defined as the resolution of all aGVHD-related symptoms. PR was defined as an improvement of at least one stage in all initial organs without any deterioration of other organs. NR was defined as the absence of improvement or deterioration in any organ or death. PD was defined as deterioration or new symptoms in any organ with or without improvement in other organs.

The secondary endpoints included the ORR at d56, DCR rate, CR rate at d28, CR rate at d56, and overall survival (OS). DCR rate was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved complete resolution of aGVHD symptoms for at least 4 weeks within 100 days after the first infusion. The cumulative incidence of relapse, non-relapse mortality (NRM), chronic GVHD (cGVHD), and failure-free survival (FFS) were also evaluated. FFS was defined as the time from randomization to relapse or progression of haematologic disease, non–relapse-related death, or the addition of new systemic therapy for aGVHD. The safety endpoints include adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) within 180 days after randomization and infusion toxicity within 14 days after the last infusion. Additionally, subgroup analyses based on the patients’ aGVHD grading, organ involvement, and steroid response were conducted to further explore the efficacy of MSCs.

The primary and secondary endpoints were analysed in both per-protocol and intention-to-treat (ITT) populations. The ITT population included all patients who were randomly assigned. The per-protocol population was defined as all patients in the ITT set, excluding patients who prematurely discontinued treatment and who received < 8 infusions. The safety endpoints were analysed in the safety set, which consisted of patients receiving ≥ 1 infusion in either group.

Statistical analysis

This was a phase 2 exploratory study aiming to investigate responsive candidates, and the sample size for this study did not consider statistical assumptions related to efficacy.

Statistical analyses were carried out according to a predetermined statistical analysis plan via the R statistical software ‘EZR’ [18], SAS 9.4, and SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A two-tailed test was used for most statistical tests, and a p value < 0.05 was chosen as the threshold for significance. Comparisons between groups for quantitative data were performed via the independent samples t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test. The chi-square test, or two-sided Fisher’s exact test, was selected for categorical data between the two groups, according to the total sample size and minimum theoretical frequency. Comparisons between groups of ranked data were performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test or CMH test.

Univariate analysis for relapse, NRM, FFS, and cGVHD with competing events was performed using Gray’s method [19]. For relapse, NRM was considered a competing event. For NRM, relapse was considered a competing event. For FFS, the competing event was the onset of chronic GVHD. For cGVHD, competing risks included relapse and death without cGVHD. OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test for univariate analysis. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were also calculated.

We did post-hoc analyses of ORR at d28, ORR at d56, DCR, CR rate at d28, CR rate at d56, OS, FFS, and cumulative incidence of cGVHD between the two groups based on groupings of patients’ characteristics. For ORR at d28, ORR at d56, DCR, CR rate at d28, CR rate at d56, and OS, we performed Cox proportional hazard regression. For FFS and cumulative incidence of cGVHD, we performed Fine-Gray proportional hazard regression for competing events. The following variables were included in the post-hoc univariable analysis: patient age, patient gender, diagnosis, conditioning regimen, donor type, CD34 + cell counts, GVHD prophylaxis regimen, steroid response, aGVHD grade, aGVHD organ involvement, number of involved organs, steroid dose at baseline, and second-line agent at baseline. Only variables with p value < 0.1 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis.

Results

Patients

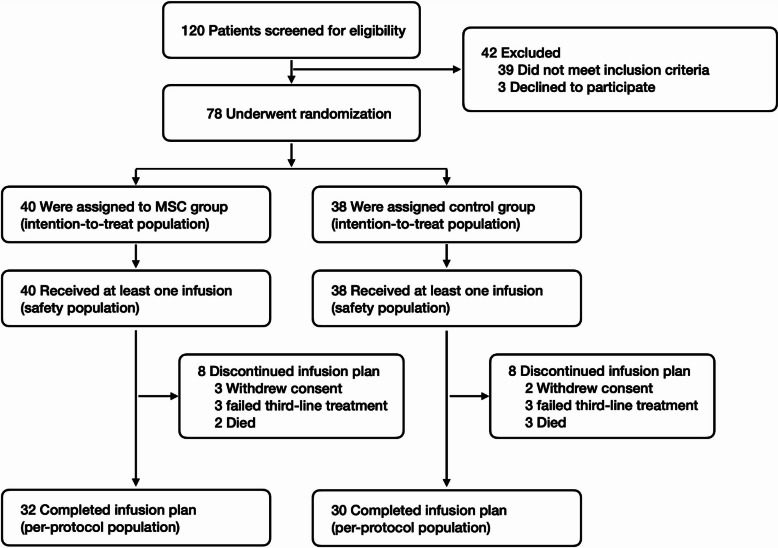

In this exploratory phase II trial, 120 patients from seven hospitals in China were screened between June 2020 and March 2022, and 78 were enrolled, with follow-up continuing until February 2024 (median, 22.3 months; range, 3.3–39.2). The original plan was to enroll 96 patients, but after enrolling 74 patients by March 2022, the sponsor consulted the Chinese National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) on conducting an efficacy analysis. By the time NMPA approved the analysis at the sponsor’s discretion, 78 patients had been enrolled, at which point the trial was stopped early. Subsequently, data from all 78 patients were unblinded and analyzed. Eligible patients were assigned to the MSC group (n = 40) or the control group (n = 38), and these patients composed the ITT set. Seventy-eight (100%) patients received at least one infusion of MSCs or placebo, and these patients composed the safety analysis set. Sixteen patients (8 in the MSC group and 8 in the control group) prematurely discontinued the study before d28 due to salvage therapy failure of aGVHD (n = 6), withdrawal of informed consent (n = 5), and early death (n = 5). The six cases of salvage therapy failure consisted of 3 cases with aGVHD grade III in the MSC group and 3 with grade III in the control group. The five cases of early death included 2 cases of septic shock in the MSC group, 2 cases of septic shock, and 1 case of heart failure in the control group. The remaining 62 patients who received ≥ 8 infusions were included in the per-protocol set, accounting for 79.6% of the ITT set. The flowchart of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study procedure

The baseline demographic and transplantation characteristics of the ITT and per-protocol populations are shown in Table 1. The proportion of patients with aGVHD grade III-IV was 43.6% in the ITT cohort and 40.3% in the per-protocol cohort. In ITT cohort, 52 patients (66.7%) had gut involvement, with 26 patients in the MSC group and 26 in the control group, respectively. In the per-protocol cohort, 42 patients (67.7%) had gut involvement, with 21 patients in the MSC and control group, respectively. At the start and early phase of second-line treatment, steroids are being rapidly tapered but not fully discontinued, with a median dose of 80 (range, 4–170) mg at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline between the MSC group and the control group in the ITT and per-protocol sets

| Variable | Intention-to-treat set | Per-protocol set | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSC | Control | MSC | Control | |

| No. of patients | 40 | 38 | 32 | 30 |

| Age, median (range), years | 37.5 (17–62) | 38.5 (13–60) | 37.5 (17–62) | 40.5 (13–60) |

| Age < 18 years, n (%) | 2 (5.0) | 5 (13.2) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (6.7) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 25 (62.5) | 21 (55.3) | 20 (62.5) | 16 (53.3) |

| Disease, n (%) | ||||

| AML | 14 (35.0) | 14 (36.8) | 12 (37.5) | 12 (40.0) |

| MDS | 10 (25.0) | 9 (23.7) | 6 (18.8) | 8 (26.7) |

| ALL | 10 (25.0) | 13 (34.2) | 9 (28.1) | 8 (26.7) |

| CML | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| NHL | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| MDS/MPN | 2 (5.0) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (6.7) |

| Conditioning, n (%) | ||||

| Bu based | 33 (82.5) | 31 (81.6) | 25 (78.1) | 23 (76.7) |

| TBI based | 6 (15.0) | 7 (18.4) | 6 (18.8) | 7 (23.3) |

| Others | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| Type of donor, n (%) | ||||

| Sibling | 14 (35.0) | 10 (26.3) | 12 (37.5) | 7 (23.3) |

| Unrelated | 4 (10.0) | 2 (5.3) | 3 (9.4) | 2 (6.7) |

| Haplo | 22 (55.0) | 26 (68.4) | 17 (53.1) | 21 (70.0) |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | ||||

| CB | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.3) |

| PBSC | 36 (90.0) | 33 (86.8) | 30 (93.7) | 29 (96.7) |

| PBSC + BM | 4 (10.0) | 4 (10.5) | 2 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| Graft | ||||

| CD34 + , median (range), *10E06/kg | 3.7 (1.5–14.7) | 4.2 (1.8–17.0) | 3.5 (2.0–12.2) | 4.1 (1.8–15.4) |

| CMV serostatus, n (%) | ||||

| D + /R + | 40 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 30 (100.0) |

| D + /R- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| D-/R + | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| D-/R- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| EBV serostatus, n (%) | ||||

| D + /R + | 40 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 30 (100.0) |

| D + /R- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| D-/R + | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| D-/R- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | ||||

| MTX + Calcineurin inhibitor | 37 (92.5) | 34 (89.5) | 31 (96.9) | 28 (93.3) |

| MTX Excluded | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.7) |

| SR aGVHD categories, n (%) | ||||

| Progression after 3 days | 22 (55.0) | 24 (63.2) | 17 (53.1) | 22 (73.3) |

| Failure to improve after 7 days | 8 (20.0) | 7 (18.4) | 6 (18.8) | 3 (10.0) |

| Failure to achieve CR after 14 days | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5.3) | 3 (9.4) | 1 (3.3) |

| Failure during taper | 7 (17.5) | 5 (13.2) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (13.3) |

| aGVHD grade at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| II | 21 (52.5) | 23 (60.5) | 19 (59.3) | 18 (60.0) |

| III | 16 (40.0) | 15 (39.5) | 10 (31.3) | 12 (40.0) |

| IV | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0) |

| aGVHD organ involvement, n (%) | ||||

| Skin | 19 (47.5) | 16 (42.1) | 16 (50.0) | 12 (40.0) |

| Liver | 12 (30.0) | 7 (18.4) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (13.3) |

| Gut | 26 (65.0) | 26 (69.4) | 21 (65.6) | 21 (70.0) |

| No. of involved organs, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 25 (62.5) | 29 (76.3) | 20 (62.5) | 24 (80.0) |

| 2 | 13 (32.5) | 7 (18.4) | 11 (34.4) | 5 (16.7) |

| 3 | 2 (5.0) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.3) |

| aGVHD onset to randomization, median (range), days | 7 (3–51) | 7 (4–62) | 8 (3–51) | 6 (4–34) |

| Steroid dose at baseline, median (range), mg/day | 80 (10–170) | 80 (4–170) | 80 (10–150) | 80 (4–170) |

| Second-line agent at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| Basiliximab | 34 (85.0) | 32 (84.2) | 28 (87.5) | 27 (90.0) |

| MTX | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.9) | 3 (9.4) | 2 (6.7) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) |

| Sirolimus | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.3) |

AML acute myeloid leukaemia, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, CML chronic myeloid leukaemia, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, MDS/MPN myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm, Bu busulfan, TBI total body irradiation, CB cord blood, PBSC peripheral blood stem cell, BM bone marrow, MTX methotrexate, CMV cytomegalovirus, EBV Epstein–Barr virus

Efficacy

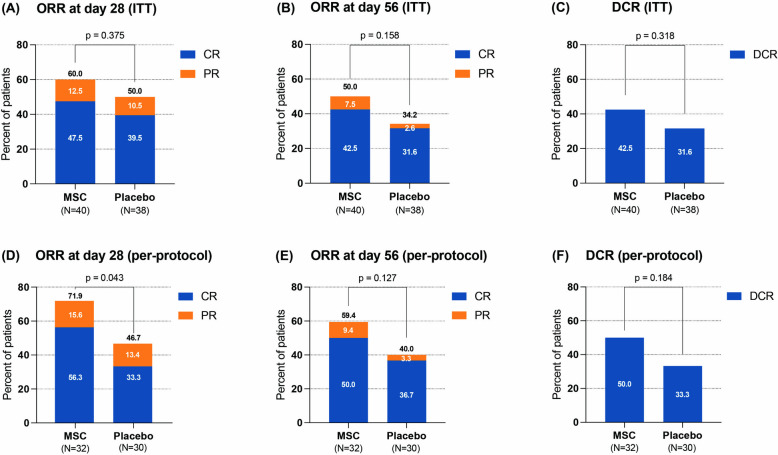

Patients in the MSC group received a median of 8 (range, 2–16) doses and exhibited a median response time of 14 (range, 5–22) days. In the ITT analysis, the ORR at d28 tended to be greater in the MSC group (60%, 24/40) than in the control group (50%, 19/38), but the difference was not significant (odds ratio, 1.50; 95% CI 0.61–3.68; p = 0.375) (Fig. 2A). The ORR at d56 was 50% (20/40) in the MSC group and 34.2% (13/38) in the control group (odds ratio, 1.92; 95% CI 0.77–4.79; p = 0.158). The DCR rate was 42.5% (17/40) in the MSC group and 31.6% (12/38) in the control group (odds ratio, 1.60; 95% CI 0.63–4.05; p = 0.318) (Fig. 2B-C). The responses of patients in the ITT cohort are presented in Table 2 as exploratory analyses. The ORR at d56 was 100% (7/7) among patients with steroid dependence in the MSC group, which was significantly greater than the 40% (2/5) in the control group (p = 0.045). The DCR rate of patients with steroid dependence in the MSC group was also significantly greater than that in the control group (100% vs. 40%, p = 0.045). Multivariable analysis showed that steroid dependence and aGVHD without gut involvement were the protective factors for ORR at d28 (Additional file 1, Table S1). Table S1 also shows protective factors for ORR at d56 and DCR in the ITT set.

Fig. 2.

Efficacy between the MSC group and the control group in all patients. A ORR at d28 in the ITT set; B ORR at d56 in the ITT set; (C) DCR rate in the ITT set; D ORR at d28 in the per-protocol set; E ORR at d56 in the per-protocol set; F DCR rate in the per-protocol set. MSC mesenchymal stem cell, ORR overall response rate, DCR durable complete response, ITT intention-to-treat

Table 2.

Treatment response between the two groups in the ITT set

| Outcomes | MSC | Control | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR at D28 | aGVHD grade | |||

| II-IV | 24/40 (60.0%) | 19/38 (50.0%) | 0.375 | |

| II | 16/21 (76.2%) | 14/23 (60.9%) | 0.276 | |

| III-IV | 8/19 (42.1%) | 5/15 (33.3%) | 0.728 | |

| involved organs | ||||

| Skin | 11/19 (57.9%) | 9/16 (56.3%) | 1 | |

| Gut | 14/26 (53.9%) | 9/26 (34.6%) | 0.163 | |

| Liver | 6/12 (50.0%) | 4/7 (57.1%) | 1 | |

| number of involved organs | ||||

| 1 | 17/25 (68.0%) | 16/29 (55.2%) | 0.335 | |

| ≥ 2 | 7/15 (46.7%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | 0.678 | |

| steroid response | ||||

| steroid dependence | 7/7 (100%) | 4/5 (80.0%) | 0.417 | |

| steroid resistance | 17/33 (51.5%) | 15/33 (45.5%) | 0.622 | |

| ORR at D56 | aGVHD grade | |||

| II-IV | 20/40 (50.0%) | 13/38 (34.2%) | 0.158 | |

| II | 13/21 (61.9%) | 10/23 (43.5%) | 0.222 | |

| III-IV | 7/19 (36.8%) | 3/15 (20.0%) | 0.451 | |

| involved organs | ||||

| Skin | 9/19 (47.4%) | 7/16 (43.8%) | 1 | |

| Gut | 10/26 (38.5%) | 5/26 (19.2%) | 0.126 | |

| Liver | 6/12 (50.0%) | 1/7 (14.3%) | 0.173 | |

| number of involved organs | ||||

| 1 | 15/25 (60.0%) | 13/29 (44.8%) | 0.266 | |

| ≥ 2 | 5/15 (33.3%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0.118 | |

| steroid response | ||||

| steroid dependence | 7/7 (100%) | 2/5 (40.0%) | 0.045 | |

| steroid resistance | 13/33 (39.4%) | 11/33 (33.3%) | 0.609 | |

| DCR | aGVHD grade | |||

| II-IV | 17/40 (42.5%) | 12/38 (31.6%) | 0.318 | |

| II | 12/21 (57.1%) | 10/23 (43.5%) | 0.365 | |

| III-IV | 5/19 (26.3%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | 0.426 | |

| involved organs | ||||

| Skin | 6/19 (31.6%) | 8/16 (50.0%) | 0.317 | |

| Gut | 8/26 (30.8%) | 3/26 (11.5%) | 0.09 | |

| Liver | 6/12 (50.0%) | 1/7 (14.3%) | 0.173 | |

| number of involved organs | ||||

| 1 | 14/25 (56.0%) | 12/29 (41.4%) | 0.284 | |

| ≥ 2 | 3/15 (20.0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0.266 | |

| steroid response | ||||

| steroid dependence | 7/7 (100%) | 2/5 (40.0%) | 0.045 | |

| steroid resistance | 10/33 (30.3%) | 10/33 (30.3) | 1 | |

According to the per-protocol analysis, the ORR at d28 was significantly greater in the MSC group than in the control group (71.9% vs. 46.7%; odds ratio, 2.92; 95% CI 1.02–8.37; p = 0.043). The CR rate at d28 was 56.3% in the MSC group and 33.3% in the control group (odds ratio, 2.57; 95% CI 0.92–7.21; p = 0.07) (Fig. 2D). The ORR at d56 tended to be greater in the MSC group (59.4%, 19/32) than in the control group (40%, 12/30), although the difference was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 2.19; 95% CI 0.79–6.05; p = 0.127) (Fig. 2E). The DCR rate was 50.0% (16/32) in the MSC group and 33.3% (10/30) in the control group (odds ratio, 2.00; 95% CI 0.72–5.59; p = 0.184) (Fig. 2F). Among patients with gut involvement, 66.7% (14/21) in the MSC group achieved an ORR at d28, which was significantly greater than the 33.3% (7/21) reported in the control group (odds ratio 4.00; 95% CI 1.11–14.43; p = 0.031). The ORR at d28, ORR at d56, and DCR rate for subgroups, which were based on the patients’ aGVHD grading, organ involvement, and steroid response are shown in Table S2 as exploratory analyses. Multivariable analysis showed that the administration of MSCs and a relatively lower baseline steroid dose were the protective factors for ORR at d28 (Additional file 1, Table S3). Protective factors for ORR at d56 and DCR in per-protocol set are also shown in Table S3. In addition, responses of patients for CR rate at d28 and d56 are presented for both the ITT and per-protocol cohorts (Additional file 1, Table S4).

Thirty-one patients in the ITT cohort developed grade III aGVHD. The ORR at d28 was 37.5% (6/16) in the MSC group and 33.3% (5/15) in the control group (odds ratio, 1.20; 95% CI 0.27–5.25; p = 0.809). All three patients who developed grade IV aGVHD were in the MSC group, with skin and gut involvement. Among them, one patient with steroid dependence achieved CR at d28. Among the two patients with steroid resistance, one achieved PR at both d28 and d56, whereas the other experienced GVHD progression within 2 days of receiving the MSC infusion and died from pneumonia at d70.

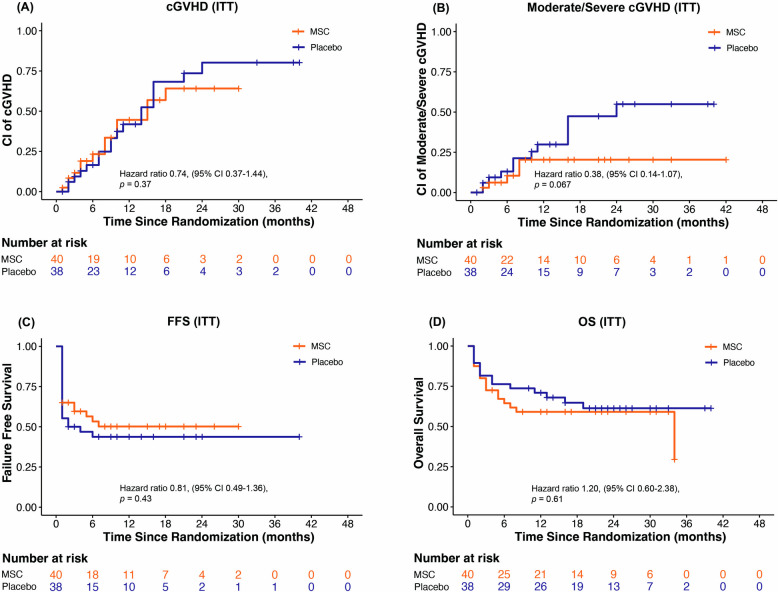

Outcomes

A trend towards a decreased cumulative incidence of cGVHD and moderate to severe cGVHD was observed in the MSC group compared with the control group in the ITT analysis (Fig. 3A-B). There were no significant differences in the 2-year FFS or OS between the two arms in the ITT analysis (Fig. 3C-D). Multivariable analysis showed that aGVHD without gut involvement was the protective factor for OS (Additional file 1, Table S5). The protective factors for FFS, cumulative incidence of cGVHD, and cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD in the ITT set are shown in Table S5.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of outcomes between the MSC group and the control group in the ITT set. A Cumulative incidence of cGVHD between two arms in the ITT set; B cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD between two arms in the ITT set; C FFS between two arms in the ITT set; D OS between two arms in the ITT set. cGVHD chronic graft-versus-host disease, ITT intention-to-treat, FFS failure-free survival, OS overall survival

According to the per-protocol analysis, the 2-year cumulative incidence of cGVHD tended to be lower in the MSC group (48.3%, 95% CI 28.4–65.6%) than in the control group (64.2%, 95% CI 41.5–79.9%), but the difference was not statistically significant (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.38–1.49, p = 0.42; Additional file 1, Figure S1A). The cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD was marginally lower in the MSC group (16.5%, 95% CI 5.9–31.8%) than in the control group (46.7%, 95% CI 25.8–65.1%) (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.13–1.02, p = 0.056; Figure S1B). The 2-year NRM was 28.9% (95% CI 14.2–45.5%) in the MSC group, whereas in the control group, it was 32.4% (95% CI 15.7–50.4%) (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.40–2.38, p = 0.95). The 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 3.6% (95% CI, 0.2–15.9%) in the control group, and no relapse was observed in the MSC group within two years after randomization. The 2-year FFS was nonsignificantly higher in the MSC group (62.5%, 95% CI 46.0–79.0%) than in the control group (46.4%, 95% CI 30.3–66.0%) (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.34–1.21, p = 0.17; Figure S1C). The 2-year OS was similar between the MSC group (71.1%, 95% CI 51.7–83.8%) and the control group (68.2%, 95% CI 47.5–82.2%) (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.41–2.43, p = 0.99; Figure S1D). Multivariable analysis showed that aGVHD without gut involvement was the protective factor for OS (Additional file 1, Table S6). Protective factors for FFS, cumulative incidence of cGVHD, and cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD in the per-protocol set are also shown in Table S6.

Safety

Within 180 days after the first infusion, 98.7% (77/78) of the patients had at least one AE: 100% (40/40) in the MSC group and 97.4% (37/38) in the control group. AEs with an incidence of ≥ 10% for any grade, ≥ 5% for grades 3–4, and all grade 5 events in either group are shown in Table 3. In the MSC group, the most common AEs by preferred term included thrombocytopenia (55%), leukopenia (53%), cytomegalovirus DNAemia (43%), anaemia (38%), and fever (38%). In the control group, the most common AEs were leukopenia (58%), thrombocytopenia (53%), anaemia (53%), cytomegalovirus DNAemia (47%), and hypokalaemia (39%).

Table 3.

Adverse events up to day 180 between the MSC group and the control group in the safety set

| Event, No. of patients (percent) | MSC (N = 40) | Control (N = 38) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Grade | Grade 3–4 | Grade 5 | Any Grade | Grade 3–4 | Grade 5 | |

| Any adverse event | 40 (100) | 34 (85) | 7 (18) | 37 (97) | 31 (82) | 6 (16) |

| Hematologic | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 22 (55) | 19 (48) | 0 (0) | 20 (53) | 20 (53) | 0 (0) |

| Leukopenia | 21 (53) | 16 (40) | 0 (0) | 22 (58) | 18 (47) | 0 (0) |

| Anemia | 15 (38) | 10 (25) | 0 (0) | 20 (53) | 14 (37) | 0 (0) |

| Neutropenia | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Leukocytosis | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Clinical diagnosed infection | ||||||

| Pneumonia | 13 (33) | 9 (23) | 2 (5) | 10 (26) | 8 (21) | 1 (3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 9 (23) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 6 (16) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 6 (15) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 6 (16) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Sepsis | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 4 (11) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) |

| Central nervous system infection | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Microbiologically documented infection | ||||||

| Cytomegalovirus DNAemia | 17 (43) | 12 (30) | 0 (0) | 18 (47) | 16 (42) | 0 (0) |

| Cytomegalovirus disease | 7 (18) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 10 (26) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Fungal infection | 5 (13) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Epstein–Barr virus infection | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Other viral infection | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Bacterial infection | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Fever | 15 (38) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 11 (29) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Hypokalemia | 12 (30) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | 15 (39) | 7 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Hypofibrinogenemia | 12 (30) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 13 (34) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 12 (30) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (26) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Weight loss | 9 (23) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 8 (21) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Hypocalcemia | 8 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (16) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Hemorrhagic cystitis | 7 (18) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 8 (21) | 7 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 7 (18) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 8 (21) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Coagulation abnormality | 5 (13) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 8 (21) | 6 (16) | 0 (0) |

| Peripheral edema | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| TMA | 5 (13) | 5 (13) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Kidney injury | 5 (13) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (13) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Arrhythmia | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Oral mucositis | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Excessive phlegm | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Epilepsy | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Insomnia | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Heart failure | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 5 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Hyponatremia | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hypoglycemia | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pleural effusion | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Drug-related liver injury | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Thyroid disorder | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Muscle weakness | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Anusitis | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| Respiratory alkalosis | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Cholecystitis | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Death not else classified | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Intestinal obstruction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Cerebral infarction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Veno-occlusive liver disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

TMA thrombotic microangiopathy

The term “‘death not otherwise classified” ‘ refers to a patient who unfortunately passed away at home after leaving the hospital and whose family declined to provide further details

No infusion-related toxicity was observed, and no secondary malignant disease occurred during the follow-up period. Investigational drug-related AEs occurred in 25% (10/40) of the patients in the MSC group and 23.7% (9/38) of those in the control group. SAEs occurred in 37.5% of the patients (15/40) in the MSC group and in 39.5% (15/38) of those in the control group. None of the SAEs were considered by investigators to be associated with the study agents.

Discussion

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled exploratory phase 2 trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of umbilical cord-derived MSCs for steroid-refractory aGVHD above grade II. The patients in the MSC group exhibited a median response time of 14 (range, 5–22) days. In the ITT cohort, the primary endpoint was not reached. In the per-protocol cohort, the primary endpoint was met, with further exploration suggesting greater benefits for aGVHD patients with gut involvement. This suggested the gradual treatment effect of MSC, which was also shown in patients with steroid dependence from the ITT cohort in the current study. The safety data were comparable between the two arms. To our knowledge, this is the most rigorously designed study to demonstrate the mode of action and identify suitable candidates for umbilical cord-derived MSCs.

In the realm of MSC therapy for aGVHD, there is significant heterogeneity concerning the cell source, dose, and infusion frequency. The MSCs used in the present study were derived from the umbilical cord. Compared with bone marrow, UC-MSCs seem to be more accessible and nontraumatic. In vitro and in vivo studies have suggested that BM-MSCs and UC-MSCs have different effects on immune cells in GVHD models [20]. To date, there has been a lack of randomized controlled trials comparing the therapeutic characteristics of the above two sources. Placenta-derived decidua stromal cells (DSCs) have shown impressive effects on aGVHD in preliminary in vitro and clinical data [21, 22]. However, further clinical phase 1/2 trials and prospective randomized trials comparing DSCs with MSCs from different sources, or the best available therapies are still needed. The dose and interval of MSC infusion have not yet been determined. The dose of MSCs used in the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of remestemcel-L was 2 × 106 cells/kg, which was infused twice weekly for 4 consecutive weeks [14]. The doses used in two studies by Chinese teams were both 1 × 106 cells/kg once weekly for 4 consecutive weeks [15, 16]. In addition, the median time to response to MSC monotherapy in patients with SR-aGVHD was approximately 28 days, which could be extended to 60 days, suggesting a relatively slower onset than that associated with other second-line therapies, such as ruxolitinib [10, 23–25]. Although direct comparisons are lacking, MSCs combined with another second-line agent seems to have advantages over MSC monotherapy in terms of ORR and even OS [15, 16, 23, 24]. In our current study, umbilical cord-derived MSCs were administered in conjunction with a baseline treatment, following a protocol of 1 × 106 cells/kg, twice weekly for 4 consecutive weeks for patients who achieved CR or 8 consecutive weeks for patients who achieved PR. The reason was based on an investigational study conducted between 2010 and 2018 for the treatment of grade 3–4 intestinal aGVHD (data not shown). With this protocol, it was found that the median time to response was 14 days in the MSC group. Although the primary endpoint was not met in the ITT set—likely because the endpoint is better suited to conventional chemical agents like ruxolitinib and does not fully capture MSCs’ benefits—MSCs demonstrated superior efficacy in patients who received 8 infusions, with further exploration indicating greater benefits for patients with gut involvement. Therefore, by analysing patients who received ≥ 8 infusions in the current study (79.5% of the total participants), the above dosing protocol brought us closer to the true mode of efficacy of MSCs. A gradual treatment effect was also noted for the treatment of steroid-dependent acute GVHD with MSCs, which benefited from the addition of MSCs to second-line treatment.

In this study, the incidence of cGVHD was lower in the MSC group than in the control group. For moderate to severe cGVHD, there was a further decline in the MSC arm compared with the control in both the ITT cohort and the per-protocol cohort. In our current study, the baseline second-line therapy was restricted to not having more than 2 agents within one centre, thus avoiding the heterogeneity of the baseline therapy. The NRM did not differ substantially between the two arms. This could be related to the efficacy of salvage therapy. Ten patients in the control group and 5 patients in the MSC group received ruxolitinib as salvage treatment. However, in total, fewer patients in the MSC group than in the control group received salvage treatments (ITT cohort, 27.5% vs. 39.5%, p = 0.262; per-protocol cohort, 25.0% vs. 43.3%, p = 0.127). This finding suggested a slight advantage in terms of efficacy in the MSC group.

The safety profile of MSC therapy in this trial was consistent with that reported in previous studies [14, 15]. The rate of AEs was similar between the two groups, and no infusion toxicity or secondary malignant disease was reported.

One limitation of the study is that the treatment response of subgroups with gut involvement, was analyzed as an exploratory rather than a pre-specified endpoint. Another limitation is the per-protocol analysis might bring possibility of selection bias, overestimate therapeutic efficacy, and limit the generalizability of the findings to real-world settings. A phase 3 study focusing on patients with gut involvement, which includes a larger cohort, is currently being conducted by our team and may address these limitations.

Conclusion

MSC therapy has been approved for paediatric patients with SR-aGVHD in Canada and New Zealand, whereas in Japan, it is approved for both paediatric and adult patients. In this exploratory study, the results of ITT cohort did not demonstrate superior ORR at d28 for MSC therapy compared with placebo. A gradual treatment effect was observed at a median of 2 weeks, with patients who completed 8 infusions potentially benefiting from MSC therapy, especially those with gut involvement. Data from our current study indicated the efficacy in adults (93.5% of the per-protocol population). In the future, combining MSC treatment with the best available care, such as ruxolitinib, for patients with SR-aGVHD, particularly those with gut involvement, may provide the greatest benefit by swiftly controlling peak inflammatory responses within days and facilitating immune modulation and the repair of immunological damage within weeks.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Comparison of outcomes between the MSC group and the control group in the per-protocol set. Table S1. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of ORR at d28, ORR at d56, and DCR in the ITT cohort. Table S2. Treatment response between the two groups in the per-protocol set. Table S3. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of ORR at d28, ORR at d56, and DCR in the per-protocol cohort. Table S4. CR rate at d28 and d56 between the two groups in the ITT and per-protocol cohort. Table S5. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of OS, FFS, cumulative incidence of cGVHD, and cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD in the ITT cohort. Table S6. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of OS, FFS, cumulative incidence of cGVHD, and cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD in the per-protocol set.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the patients and their families for their valuable participation.

Abbreviations

- AEs

Adverse events

- aGVHD

Acute graft-versus-host disease

- allo-HSCT

Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- BM-MSCs

Bone marrow-derived MSCs

- cGVHD

Chronic graft-versus-host disease

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIMS-CRS

Central Randomization System of Clinical Information Management System

- CR

Complete response

- DCR

Durable complete response

- DSCs

Decidua stromal cells

- EBMT

European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FFS

Failure-free survival

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IDO

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IFN-γ

Interferon gamma

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- ITT

Intention-to-treat

- JAK

Janus kinase

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NR

No response

- NRM

Non-relapse mortality

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- ORR

Overall response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progression of disease

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- PR

Partial response

- SAEs

Serious adverse events

- SFM

Serum-free medium

- SR-aGVHD

Steroid-refractory aGVHD

- TGF-α

Transforming growth factor alpha

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

- UC-MSCs

Umbilical cord-derived MSCs

- UCT

Umbilical cord tissue

Authors’ contributions

D.L. was the primary corresponding author, responsible for all communication about this article. D.L., M.H., and X.H. were the co-corresponding authors, having full access to all the data in the study and taking responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data and its analysis. D.L., M.H., X.H., and K.Q. contributed to drafting the manuscript. K.Q., L.W., C.Y., and Y.S. conducted the statistical analysis. D.L. and M.H. supervised the study. D.Y., L.H., Y.H., and L.W. were involved in enrolling patients and performing medical interventions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Platinumlife Biotechnology (Beijing), which provided the study drug and worked in conjunction with the senior academic authors to design the study. All the data were collected by the investigators and their site personnel and were analysed and interpreted by senior academic authors and representatives of the funder.

Data availability

The authors declared that all and the other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (C2020-016–05). Patient’s written consent to participate in this clinical trial was obtained prior to any study-specific procedures.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

X.H. is an employee of Platinumlife Biotechnology (Beijing). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Erlie Jiang, Kun Qian, Lu Wang, Donglin Yang and Yangliu Shao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mingzhe Han, Email: mzhan@ihcams.ac.cn.

Xiaoqiang Hou, Email: houxiaoqiang@platinumlife.cn.

Daihong Liu, Email: daihongrm@163.com.

References

- 1.Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease - Biologic Process, Prevention, and Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2167–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penack O, Marchetti M, Ruutu T, Aljurf M, Bacigalupo A, Bonifazi F, et al. Prophylaxis and management of graft versus host disease after stem-cell transplantation for haematological malignancies: updated consensus recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(2):e157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penack O, Marchetti M, Aljurf M, Arat M, Bonifazi F, Duarte RF, et al. Prophylaxis and management of graft-versus-host disease after stem-cell transplantation for haematological malignancies: updated consensus recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet Haematol. 2024;11(2):e147–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruutu T, Gratwohl A, de Witte T, Afanasyev B, Apperley J, Bacigalupo A, et al. Prophylaxis and treatment of GVHD: EBMT-ELN working group recommendations for a standardized practice. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(2):168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin PJ, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR, Ballen K, Curtin PT, Cutler C, et al. First- and second-line systemic treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: recommendations of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(8):1150–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westin JR, Saliba RM, De Lima M, Alousi A, Hosing C, Qazilbash MH, et al. Steroid-Refractory Acute GVHD: Predictors and Outcomes. Adv Hematol. 2011;2011:601953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arai S, Margolis J, Zahurak M, Anders V, Vogelsang GB. Poor outcome in steroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease with antithymocyte globulin treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(3):155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoemans HM, Lee SJ, Ferrara JL, Wolff D, Levine JE, Schultz KR, et al. EBMT-NIH-CIBMTR Task Force position statement on standardized terminology & guidance for graft-versus-host disease assessment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(11):1401–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Przepiorka D, Luo L, Subramaniam S, Qiu J, Gudi R, Cunningham LC, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Ruxolitinib for Treatment of Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Oncologist. 2020;25(2):e328–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagasia M, Perales MA, Schroeder MA, Ali H, Shah NN, Chen YB, et al. Ruxolitinib for the treatment of steroid-refractory acute GVHD (REACH1): a multicenter, open-label phase 2 trial. Blood. 2020;135(20):1739–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, Wang Y, Li Q, Liu K, Hou J, Shao C, et al. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem and stromal cells in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(8):493–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao F, Chiu SM, Motan DA, Zhang Z, Chen L, Ji HL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(1): e2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Gotherstrom C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kebriaei P, Hayes J, Daly A, Uberti J, Marks DI, Soiffer R, et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Study of Remestemcel-L versus Placebo Added to Second-Line Therapy in Patients with Steroid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(5):835–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao K, Lin R, Fan Z, Chen X, Wang Y, Huang F, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells plus basiliximab, calcineurin inhibitor as treatment of steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease: a multicenter, randomized, phase 3, open-label trial. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu H, Sun X, Lin R, Wang Y, Xuan L, Yao H, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells plus basiliximab improve the response of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease as a second-line therapy: a multicentre, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang D, Hou X, Qian K, Li Y, Hu L, Li L, et al. Efficacy and safety of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSC PLEB001) for the treatment of grade II-IV steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: a study protocol for a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Trials. 2023;24(1):306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F. Competing risk analysis using R: an easy guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40(4):381–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregoire C, Ritacco C, Hannon M, Seidel L, Delens L, Belle L, et al. Comparison of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells From Different Origins for the Treatment of Graft-vs.-Host-Disease in a Humanized Mouse Model. Front Immunol. 2019;10:619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ringden O, Baygan A, Remberger M, Gustafsson B, Winiarski J, Khoein B, et al. Placenta-Derived Decidua Stromal Cells for Treatment of Severe Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7(4):325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson H, Erkers T, Nava S, Ruhm S, Westgren M, Ringden O. Stromal cells from term fetal membrane are highly suppressive in allogeneic settings in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167(3):543–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N, Butler J, Mohty M, Niederwieser D, Or R, et al. Ruxolitinib for Glucocorticoid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1800–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murata M, Terakura S, Wake A, Miyao K, Ikegame K, Uchida N, et al. Off-the-shelf bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease: real-world evidence. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021;56(10):2355–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloor AJC, Patel A, Griffin JE, Gilleece MH, Radia R, Yeung DT, et al. Production, safety and efficacy of iPSC-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in acute steroid-resistant graft versus host disease: a phase I, multicenter, open-label, dose-escalation study. Nat Med. 2020;26(11):1720–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Comparison of outcomes between the MSC group and the control group in the per-protocol set. Table S1. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of ORR at d28, ORR at d56, and DCR in the ITT cohort. Table S2. Treatment response between the two groups in the per-protocol set. Table S3. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of ORR at d28, ORR at d56, and DCR in the per-protocol cohort. Table S4. CR rate at d28 and d56 between the two groups in the ITT and per-protocol cohort. Table S5. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of OS, FFS, cumulative incidence of cGVHD, and cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD in the ITT cohort. Table S6. Univariable and Multivariable analysis of OS, FFS, cumulative incidence of cGVHD, and cumulative incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD in the per-protocol set.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declared that all and the other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.