Abstract

Objective

Research has revealed that patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy exhibit significantly elevated nerve stimulation thresholds. However, the minimum stimulation thresholds of peripheral nerves in patients with diabetic foot, along with the recovery of nerve function, remain undetermined. The aim of this study is to investigate the minimum stimulation thresholds of the femoral and sciatic nerves, as well as the duration of nerve block, in patients diagnosed with diabetic foot.

Methods

From July 2020 to March 2022, a prospective study was conducted involving patients aged 50–80 scheduled for distal lower limb surgery. The study included 83 patients with diabetic foot and 48 individuals without diabetes. Prior to surgery, an ultrasound-guided approach combined with nerve stimulation was employed to administer a popliteal sciatic nerve block (20 mL of ropivacaine 5 mg/mL) and a femoral nerve block (20 mL of ropivacaine 5 mg/mL). During the ultrasound-guided femoral and popliteal sciatic nerve blocks, the electric current required to elicit motor activity in both the femoral and popliteal sciatic nerves was assessed.

Results

The study revealed that patients with diabetic foot exhibited significantly higher stimulation thresholds for femoral and sciatic nerve blocks, as well as a substantially longer duration of femoral and sciatic sensory and motor blocks (P < 0.01). Additionally, nerve injury was observed in 4 patients (4.8%) within the diabetes mellitus (DM) group.

Conclusion

Patients with diabetic foot exhibit higher minimum stimulus thresholds for the femoral and sciatic nerves and experience delayed recovery from ropivacaine block.

Keywords: diabetic foot, nerve damage, nerve blocks, minimal stimulation threshold, ultrasound

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most prevalent metabolic disorders globally, affecting both developed and developing countries. Over the past two decades, the global prevalence of diabetes has surged from 150 million in 2000 to 425 million in 2017, with projections estimating it will reach 629 million by 2045.1 According to the International Diabetes Federation, the annual global expenditure on diabetes is approximately US $760 billion, anticipated to rise to US $825 billion by 2030.2 Diabetes and its complications have emerged as a global public health emergency due to the high rates of mortality, morbidity, and disability associated with them. Additionally, the prevalence of neuropathy among individuals with diabetes is approximately 30%.3 Diabetes can harm the peripheral nerves of the lower extremities, causing a distinctive syndrome. Approximately 8% of diabetic patients experience foot ulcers, and around 1.8% require amputation.4 An ultrasound-guided lower extremity nerve block is a highly effective option that ensures optimal anesthesia and effective postoperative pain relief during foot surgery for patients with diabetes. However, it is crucial to consider that certain local anesthetics can cause neurotoxicity at high concentrations or with prolonged exposure, potentially resulting in irreversible neurological damage.5 Peripheral neuropathy often exhibit increased sensitivity to local anesthesia and experience longer-duration nerve blocks in patients with diabetes.6 Some animal studies suggest that longer-duration nerve blocks may not cause neurotoxicity, although there are conflicting reports on whether nerve blocks can cause neurotoxic injury in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.7

This study was designed to compare the effects of sciatic and femoral nerve blocks in patients with and without diabetes. The objectives are to determine how diabetic neuropathy influences the stimulation currents required to elicit a motor response during these nerve blocks, and to assess whether nerve blocks result in any neurotoxicity or nerve injury, such as prolonged nerve conduction block.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This prospective cohort study, complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the First Affiliated Hospital Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University (2020014) and registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000033628), involved the participation of patients who had provided written consent. Conducted at the Department of Orthopedics, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, between June 8, 2020, and May 30, 2022, the study included patients undergoing either general anesthesia combined with nerve block anesthesia or nerve block anesthesia alone for surgeries below the knee joint, such as foot wound debridement, debridement with VSD negative pressure suction, toe amputation, and transverse osteotomy of the tibia. Patient selection criteria included individuals aged 18–80 years, with ASA status ≤ IV and without severe organ damage. Exclusion criteria comprised refusal of a nerve block, known allergy to local anesthetics, infection at the puncture site, sepsis, history of mental illness, inability to complete the questionnaire, and the presence of other neuropathies or preoperative paralysis. The participants were categorized into two groups: patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and diabetic foot, and patients without diabetes.

Sample Size Calculation

This study employs a two-sided test with a significance level of α = 0.05 and a power of 0.9. The primary outcome measures include the duration of sensory blockade in the lower limb nerves, along with other secondary measures. Based on the research by Shuai Tang et al, the duration of sensory nerve blockade following lower limb nerve block anesthesia was 19.76 ± 5.99 hours for patients with diabetes and 15.62 ± 5.1 hours for patients without diabetes.8 Calculations indicated a required sample size of n = 33 for each group, necessitating at least 33 cases for both the diabetic foot group and the non-diabetic group. Accounting for a 10% sample loss rate, potential loss to follow-up, and other factors, the final sample size was determined to be 74 cases (37 cases per group).

Diabetic Neuropathy

The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) has established the following diagnostic criteria for diabetic foot and diabetic peripheral neuropathy:9

Diabetic foot: for patients with a new or existing diagnosis of diabetes, the presence of infection, ulceration, or tissue destruction in the foot is often associated with peripheral neuropathy and/or peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Diabetic neuropathy: Symptoms and/or signs of neurological dysfunction in patients with diabetes, after excluding other causes of peripheral nerve damage. In the study, all patients underwent screening for coexisting peripheral neuropathy and a clinical examination of their lower extremities following the guidelines for diagnosing and managing diabetic peripheral neuropathy in an outpatient setting.9 During the assessment, patients were evaluated for pain, warmth sensations, stress detection, and vibration detection. Patients were instructed to lie down, relax, and close their eyes. Vibration perception was then assessed using a 128 hz tuning fork on the medial malleolus and hallux, graded on a scale of 0 to 8. Light touch perception was tested with a cotton wisp, pressure reception with a 10g monofilament, pain sensation with a pin-prick, and temperature discrimination with a device measuring the ability to differentiate between materials with different thermal conductivities (tip therm©, tip therm GmbH, Brueggen, Germany).10 These assessments were scored as present or absent.

Femoral and sciatic nerve blocks: All patients were closely monitored, with assessments including SpO2, ECG, and non-invasive arterial pressure. Upon entering the operating room, patients were administered dexmedetomidine at a rate of 0.5μg/kg/h, and venous access was established. Nerves were localized using a Sono M-Turbo ultrasonic high-frequency probe and a Braun plexus stimulator. To initiate the procedure, an ultrasound transducer (Sonosite SII Portable Color Ultrasound System, USA) with a frequency range of 8–12 hz was positioned transversely on the skin in the popliteal region to identify the tibial and fibular sciatic nerves and in the inguinal ligament area to locate the femoral nerve. After identifying the sciatic nerve and the tibial and common peroneal areas, the ultrasound probe was moved approximately 10 cm above the popliteal fold to focus on the nerve division. An 80 mm insulated needle (Stimuplex, B Braun, Melsungen, Germany), connected to a neurostimulator (Stimuplex HN, model number 4892098) was introduced into the sciatic nerve branch. For the femoral nerve, the ultrasound probe was positioned parallel to the inguinal ligament and scanned approximately 2 cm above and below this ligament to locate the lateral edge of the femoral nerve, the iliac fascia, and the iliacus muscle. Stimulation was commenced with an initial current of 2.0 mA (frequency: 1 hz; duration: 0.1 ms) to induce a motor response in the sciatic nerve (foot plantar flexion or extension) and in the femoral nerve (quadriceps contraction). The stimulation current was incrementally adjusted until the minimal current intensity needed to produce a motor response in the innervated area was identified; this value was recorded as the minimum stimulation threshold. Subsequently, an extraneural injection of ropivacaine (0.5% ropivacaine, 20 mL) was administered around the femoral and sciatic nerves in both groups. All nerve blocks were conducted or supervised by the authors and evaluated by a blinded investigator.

Efficiency Measurements and Variables

An anesthesiologist assessed the sensory and motor block every minute for a duration of 50 minutes. Following the method prescribed by Baeriswyl et al, the sensory block of the sciatic and femoral nerves was evaluated using the pinprick test.6 The scoring was based on the patient’s response: 1 = normal sensation (no block), 2 = delayed sensation (analgesia), and 3 = no sensation (anesthesia). The patient was asked to perform plantarflexion or dorsiflexion of the foot, as well as hip flexion and knee extension movements to evaluate the motor block of the sciatic and femoral nerves. The results were graded as follows: 1 = normal movement (no blockage); 2 = reduced movement (partial blockage); 3 = no movement (complete blockage). Neurological recovery was defined as the return of sensory and motor function to the preoperative baseline. The resident in charge of the patient conducted hourly tests to monitor the resolution of sensory (using a pinprick test) and motor (using movements) blocks after surgery until complete regression. If sensory or motor blockade persisted beyond 48 hours after local anesthetic injection, acute nerve injury was assessed.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables that approximately follow a normal distribution such as age and nerve block duration were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Group comparisons for these continuous variables were made using an independent sample t-test. Categorical variables, including sex and ASA status, were presented as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons for categorical variables were conducted using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Potential confounders and effect modifiers were assessed through interaction testing before regression analysis. We used a general linear regression model to compare the minimum nerve stimulation threshold and block duration differences between diabetic and non-diabetic groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference. Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.1.2 software.

Results

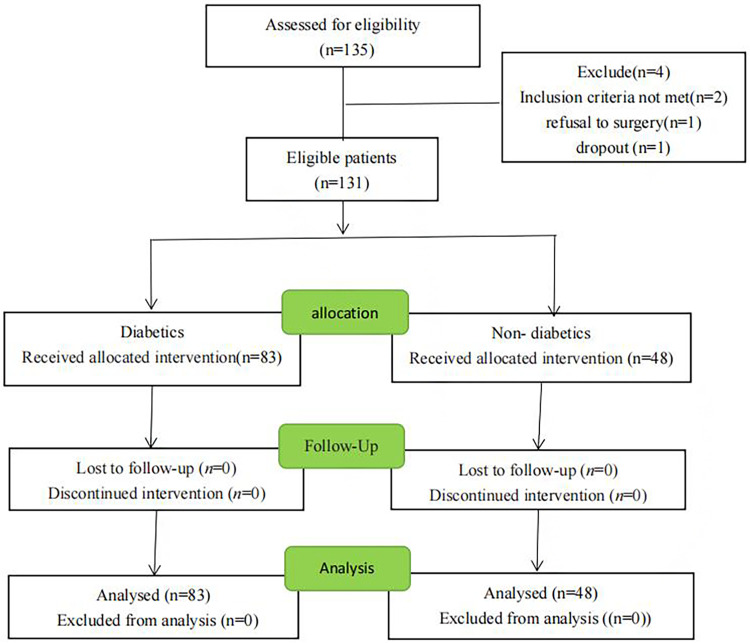

The study flow chart is presented in Figure 1. During the study period, a total of 135 patients were evaluated for eligibility, with 83 being classified into the diabetic group and 48 into the non-diabetic group. Two patients were excluded due to their age (over 80 years), one patient refused surgery, and one was excluded due to postoperative follow-up dropout. The demographic and baseline characteristics of the included patients are detailed in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of mean age, gender, BMI, smoking, drinking, and residence (P > 0.05). However, the disability rate was significantly higher in the diabetic group compared to the non-diabetic group. Additionally, ASA status was significantly different among patients with diabetes. The diabetic group exhibited higher ratios of preoperative comorbidities, such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, pulmonary complications, and cerebral infarction, compared to the non-diabetic group. The diabetic group also had significantly higher MNSI and TCNS scores than the control group (Table 1). Furthermore, the length of hospital stay was longer in the diabetic group (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Notes: Over the study period, 135 patients were screened for eligibility, and 83 were analyzed in the diabetic group and 48 in the non-diabetic group. Two patients were excluded because of age >80 years, one patient was not included because of refusal of surgery, and one was excluded because of dropout from postoperative follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Variables, Data are Mean (SD), Median (25th–75th), or Number (%).*P, 0.05 Vs the N-DM Group

| variables | N-DM (n=48) | DM (n=83) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 60 (45,71) | 65 (55,69) | 0.132 |

| Man/women n,(%) | 32 (66.7%)/16 (33.3%) | 64 (77.1)/19 (22.9) | 0.193 |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 22 (19.5,24.3) | 22.1 (20.55,25.1) | 0.177 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 25 (52.1%) | 48 (57.8%) | 0.523 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 24 (50.0%) | 49 (59.0%) | 0.316 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.611 | ||

| Junior high school | 18 (37.5%) | 30 (36.1%) | |

| Primary school | 7 (14.6%) | 8 (9.6%) | |

| High school or above | 12 (25.0%) | 29 (34.9%) | |

| Illiteracy | 11 (22.9%) | 16 (19.3%) | |

| Residence | 0.138 | ||

| City | 14 (29.2%) | 35 (42.2%) | |

| Rural | 34 (70.8%) | 48 (57.8%) | |

| Disabled | 13 (27.1%) | 61 (73.5%)* | 0.001 |

| ASA states (I/II/III/IV) | 5/19/23/1 | 0/16/63*/4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes duration (yr) | NA | 11.(5.2, 15.7) | |

| Diabetes treatment Insulin/Oral |

NA | 27 (32.5%)/12 (14.4%) | |

| Not controlled | NA | 44 (53%) | |

| Comorbid disease by system | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 12 (25%) | 42 (50.6%)* | 0.04 |

| Coronary disease, n (%) | 6 (12.5%) | 23 (27.7%)* | 0.043 |

| Coronary arteriosclerosis | 17 (35.4%) | 60 (72.3%)* | <0.001 |

| Lung disease, n (%) | 33 (68.8%) | 71 (85.5%)* | 0.022 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 19 (22.9%)* | <0.001 |

| Nephropathy | 0 (0.0%) | 83 (100%)* | <0.001 |

| MNSI score | 2 (1, 3) | 5 (4, 6)* | <0.001 |

| TCSS score | 4 (2, 5) | 14 (11, 15)* | <0.001 |

| Tramadol | 22 (45.8%) | 24 (28.9%) | 0.051 |

| Length of hospital stay(d) | 8.5 (6, 11) | 11 (7, 16)* | 0.33 |

| Hospital costs(US) | 4541 (3697, 8071) | 6166 (4251, 9122) | 0.125 |

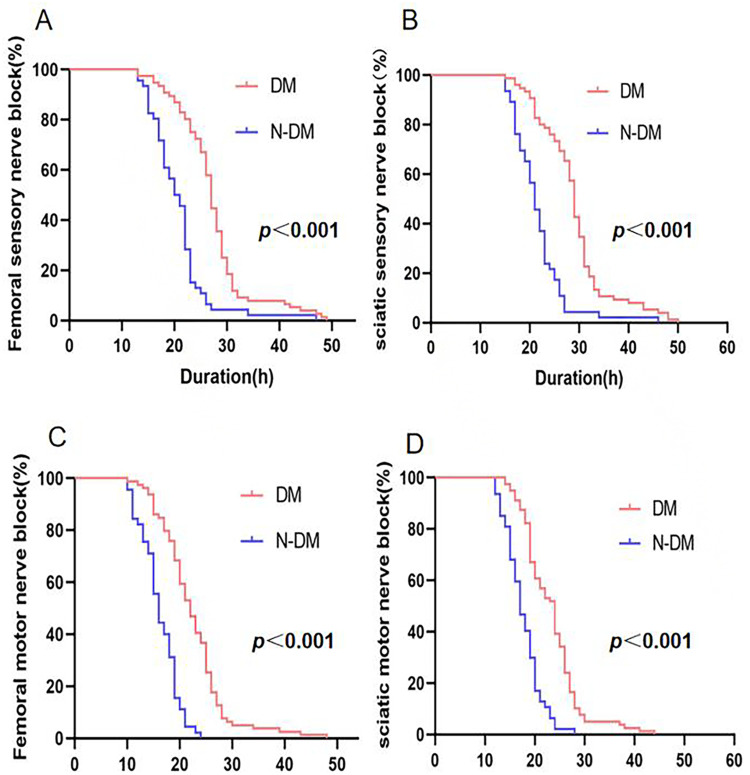

Significant differences were observed in the minimum stimulation intensity required for femoral and sciatic nerve blocks between the diabetic and control groups, with the diabetic group requiring higher stimulation currents (Table 2). Additionally, the duration of sensory and motor blocks for the sciatic and femoral nerves was significantly longer in the diabetic group, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The median sensory block duration for the sciatic nerve (25th - 75th percentile) was 28.6 (25.7, 31.3) hours in the diabetic group, compared to 21.3 (17.5, 25) hours in the control group (P < 0.01). Furthermore, the diabetic group exhibited a longer motor block duration of 23.6 (19.0, 26.2) hours, compared to 17.1 (15.0, 19.7) hours in the control group (P < 0.01). Similarly, the median sensory block duration for the femoral nerve was 27.1 (23.7, 29.8) hours in the diabetic group, significantly longer than the 20.9 (17.1, 23) hours observed in the control group (P < 0.01). The motor block duration for the femoral nerve was also significantly longer in the diabetic group at 22.8 (18.5, 25.1) hours, compared to 16.1 (13.5, 18.9) hours in the control group. The study also identified a significant prolongation of postoperative sensory block, suggesting potential nerve damage, with four such cases observed in the diabetic group and one case in the non-diabetic group.

Table 2.

Femoral and Sciatic Nerve’s Stimulation Threshold, Onset Time, Duration of Femoral and Sciatic Nerve blocks. Data are Median (25–75th Inter-quartiles). Model 1 a Simple Linear regression. Model 2 b Multiple Linear Regression Adjusted for Covariates Such as Age, Sex, BMI, Smoking, Alcohol Consumption, Education, Ethnicity, Place of Residence, and disability. Model 3c Multiple Linear Regression Adjusted forModel2, HB, WBC, Albumin, Serum Creatinine, Filtration Rate, Total Bile, Glycerol, ASA States and Preoperative comorbidities.*P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001

| variables | N-DM (n=48) | DM (n=83) | Differences Between Non-Diabetic and Diabetic Groups (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 3c | |||

| Stimulation threshold(ma) | |||||

| Femoral nerve | 0.28 (0.20, 0.34) | 0.42 (0.30, 0.60) | 0.17 (0.11, 0.24)*** | 0.20 (0.12, 0.27)*** | 0.12 (0.03, 0.21)* |

| Sciatic nerve | 0.32 (0.26, 0.44) | 0.66 (0.47, 0.90) | 0.45 (0.28, 0.61)*** | 0.51 (0.32, 0.69)*** | 0.34 (0.11, 0.57)** |

| Onset time (min) | |||||

| Femoral nerve sensory block | 12 (9, 15) | 5 (4, 6) | −6.8 (−8.2, −5.4)*** | −6.3 (−7.9, −4.8)*** | −6 (−8, −3.9)*** |

| Sciatic nerve sensory block | 16 (12, 19) | 7 (5, 11) | −6.3 (−8.4, −4.3)*** | −5.6 (−7.9, −3.4)*** | −5 (−8.1, −2.)** |

| Femoral nerve motor block | 18 (15, 21) | 9 (6, 11) | −7.9 (−9.7, −6.2)*** | −7 (−8.8, −5.1)*** | −6.5 (−8.9, −4.2)*** |

| Sciatic nerve motor block | 21 (17, 23) | 13 (9, 17) | −5.9 (−8.3, −3.5)*** | −4.8 (−7.5, −2.2)*** | −2.6 (−6.1, 0.8)* |

| Nerve block duaration (h) | |||||

| Femoral nerve (sensory) | 20.9 (17.1, 23.0) | 27.1 (23.7, 29.8) | 6.7 (3.3, 10.1)*** | 7.5 (3.7, 11.4)*** | 7.2 (2, 12.5)** |

| Sciatic nerve (sensory) | 21.3 (17.5, 25) | 28.6 (25.7, 31.3) | 6. (3.5, 8.5) *** | 6.2 (3.5, 9)*** | 5.6 (2.3, 8.8) ** |

| Femoral nerve (motor) | 16.1 (13.5, 18.9) | 22.8 (18.5, 25.1) | 4,8 (2.5, 7.1) *** | 5.8 (3.3, 8.4)*** | 5.3 (2.0, 8.6) ** |

| Sciatic nerve (motor) | 17.1 (15, 19.7) | 23.6 (19, 26.2) | 5.4 (3.6, 7.2) *** | 6.4 (4.4, 8.3) *** | 5.4 (2.9, 7.8) *** |

Figure 2.

Duration of nerve block.

Notes: (A and B) Sciatic(femoral) nerve sensory recovery in the diabetic group (n=83) and the control group (n=49). Sensory evaluation (pin-prick) was performed every hour after surgery until recovery. P-value refers to comparison between groups (logrank test). (C and D) Sciatic(femoral) nerve motor recovery in the diabetic group (n=83) and the control group (n=49). Motor evaluation was performed every hour after surgery until recovery. P-value refers to comparison between groups (logrank test).

Discussion

This prospective cohort study evaluated the minimum stimulation intensity and the sensory and motor nerve block duration in patients who received popliteal sciatic and femoral nerve blocks. The findings indicated that the diabetic group required higher stimulation currents, and the duration of both sensory and motor blocks for the sciatic and femoral nerves was significantly prolonged. Keyl conducted a similar prospective parallel cohort study comparing the electrical sciatic nerve stimulation threshold between patients with diabetic foot gangrene and patients without diabetes, revealing that the minimal sciatic nerve stimulation threshold in patients with diabetic foot gangrene was 7.2 times higher than in patients without diabetes.11 Other studies have also shown a significantly higher minimum current stimulation threshold for the sciatic nerve in patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy compared to patients without diabetes.12,13

Patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy typically exhibit an increased minimum stimulation threshold of peripheral nerves and an extended duration of nerve blocks when receiving anesthesia. Tang et al compared patients with and without diabetes undergoing lower limb surgery with sciatic nerve blocks guided by ultrasound and neurostimulation, finding that patients with diabetes had a longer duration of sensory nerve block.8 Additionally, Salviz et al identified a correlation between diabetes and an extended duration of sensory block after axillary brachial plexus block.14 The results of this study are consistent with the findings of most previous studies, indicating that local anesthetics have a prolonged effect on patients with diabetic foot compared to patients without diabetes.

The underlying mechanism contributing to the prolonged duration of nerve blocks in diabetic patients remains uncertain. Nonetheless, animal models of diabetic neuropathy have demonstrated heightened sensitivity of peripheral nerves to local anesthetics, slower pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, and extended perineural retention, all of which can contribute to longer block durations.15 Several studies suggest that diabetes-induced microvascular dysfunction, such as endothelial alterations, impacts the absorption and metabolism of local anesthetics, which is a primary factor behind the extended block duration. Elevated HbA1c levels, indicative of chronic poor glycemic control, have also been identified as an independent risk factor for prolonged nerve block duration.16 Conversely, Emanuel et al proposed that the prolonged nerve block duration in patients with diabetes is primarily due to the neuropathy associated with diabetes.17 Further research involving larger diabetic populations is required to definitively address this question.

A significant prolongation of postoperative sensory block in both groups, with 4 cases in the diabetic group and 2 cases in the non-diabetic group, reporting symptoms such as numbness and decreased muscle strength were identified in the study. In the diabetic foot group, all patients with suspected nerve injury returned to their preoperative state 72 hours post-surgery. In the non-diabetic group, one patient achieved complete sensory and motor recovery 36 hours after surgery, while the other experienced neurosensory numbness that persisted for a week. Nerve injuries resulting from nerve blocks can generally be classified into three types: mechanical damage and injection injury (traumatic), vascular injury (ischemic), and chemical injury (neurotoxicity). If a local anesthetic is injected into the nerve bundle or the puncture needle damages the nerve during the procedure, it can lead to nerve rupture, disrupting the neuroprotective environment of the bundle and causing myelin sheath and axonal degeneration.18 Additionally, some studies suggest that the neurotoxic effects of local anesthetics can cause damage, particularly in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Furthermore, patients with peripheral nerves in prolonged ischemia are more prone to nerve damage and exhibit increased sensitivity to local anesthetics.19,20 Animal studies have also shown that rats with diabetes receiving regional anesthetic nerve blocks exhibit nerve damage, including nerve edema and abnormal myelinated axons.21

In our study, nerve injury was observed in both patient groups; however, the use of a nerve stimulator and ultrasound visualization during the nerve block procedure minimized the risk of intraneural injection-induced nerve ischemia and vascular injury. Several mechanisms may account for the prolonged postoperative sensory blocks observed in these patients. It is hypothesized that the administration of higher concentrations of local anesthetics is a primary factor contributing to the extended duration of nerve blocks in susceptible patients. Studies have shown that patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) exhibit significantly reduced vibration perception threshold (VPT), cold perception threshold (CPT), and warm perception threshold (WPT) under various current stimuli.22 This reduction explains why the minimum stimulation threshold in diabetic patients is significantly higher than in patients without diabetes. The proposed mechanism for prolonged nerve blockade time in diabetic patients suggests that the pathological and physiological changes associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy may affect the pharmacokinetics of local anesthetics. These changes result in reduced nerve blood flow and prolonged retention time of the local anesthetic, ultimately leading to an increased nerve blockade duration.

Chronic ischemic hypoxia and reduced blood flow to the peripheral nerves in patients with diabetic foot can influence the pharmacodynamics of local anesthesia. This is evidenced by an increased sensitivity of sodium ion channels to local anesthetics, which facilitates nerve conduction blockade and results in a shorter onset time. Additionally, a study by Chang et al highlighted that some patients experience varying degrees of motor and sensory impairments after using a tourniquet, a phenomenon referred to as “tourniquet-related nerve injury”.23,24 This type of injury can occur through mechanical compression and/or ischemic damage when the tourniquet’s occlusive pressure exceeds the capillary closing pressure, potentially leading to nerve ischemia. Tourniquet-related nerve damage typically manifests as a temporary loss of limb motor function, decreased tactile, vibratory, and positional sensations, and retained thermal, cold, and painful sensations. Research has identified the sciatic nerve as the most commonly affected lower limb nerve in tourniquet-related injuries.25 Masri et al found that advanced age, obesity, and peripheral neuropathy are potential risk factors for tourniquet-induced nerve damage.24 Consequently, it is inferred that the “double squeeze” effect of a tourniquet can cause nerve ischemia and reperfusion injury, leading to inflammation and paresthesia. However, the precise impact of nerve blocks on diabetic peripheral nerve injury and the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Further high-quality animal studies involving larger diabetic populations are necessary to investigate this issue comprehensively.

There were several limitations in the present study. Firstly, an electrodiagnostic assessment, which is considered the reference standard for evaluating neuropathy, was not performed. Secondly, we used ropivacaine at a concentration of 5 mg/mL for nerve block and did not study the minimum local anesthetic concentration required to achieve nerve block anesthesia. Lastly, the study included only patients diagnosed with diabetic foot with peripheral neuropathy, and there was a lack of studies of diabetic patients without peripheral neuropathy.

Conclusion

A significant prolongation in sensory and motor block durations was observed among patients with diabetic foot. Additionally, we recorded an increase in the minimum stimulus threshold.

Acknowledgments

This study was coordinated by the Department of Anaesthesiology and Department of Information, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Guangxi, China, and the Department of Information Technology and Department of Medical Statistics.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Guangxi Natural Science Foundation, grant numbers 2020GXNSFDA238025; National Key 230 R&D Program, grant numbers (2018YFC2001905); Guangxi Health Commission (Z20210015); Beijing Medical Award Foundation (YXJL-2021-0307-0467); Guangxi Medical and health appropriate technology development and promotion Foundation (S2020021).

Abbreviations

PAD, peripheral arterial disease; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiolog; DM, diabetes mellitus; N-DM, Non-diabetes mellitus; MNSI, Michigan Neuropa Instrument; TCNS, Toronto Clinical Neuropathy Score; DPN, diabetic peripheral neuropathy; VPT, vibration perception threshold; CPT, cold perception threshold; WPT, warm perception threshold; Las, local anesthetics; IWGDF, International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot; BMI, Body mass index.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9th edition. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 157;2019:107843. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(6):521–534. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70065-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan TW, Armstrong DG, Concha-Moore KC, et al. Association between race/ethnicity and the risk of amputation of lower extremities among medicare beneficiaries with diabetic foot ulcers and diabetic foot infections. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001328. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitagawa N, Oda M, Totoki T. Possible mechanism of irreversible nerve injury caused by local anesthetics: detergent properties of local anesthetics and membrane disruption. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(4):962–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeriswyl M, Taffé P, Kirkham KR, et al. Comparison of peripheral nerve blockade characteristics between non-diabetic patients and patients suffering from diabetic neuropathy: a prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(9):1110–1117. doi: 10.1111/anae.14347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lirk P, Verhamme C, Boeckh R, et al. Effects of early and late diabetic neuropathy on sciatic nerve block duration and neurotoxicity in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(2):319–326. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang S, Wang J, Tian Y, et al. Sex-dependent prolongation of sciatic nerve blockade in diabetes patients: a prospective cohort study. Reg Anesth Pain Med;2019. rapm–2019–100609. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2019-100609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, et al.; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36 Suppl 1:e3268. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanathan V, Snehalatha C, Seena R, Ramachandran A. Early recognition of diabetic neuropathy: evaluation of a simple outpatient procedure using thermal perception. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(923):541–542. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.923.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyl C, Held T, Albiez G, et al. Increased electrical nerve stimulation threshold of the sciatic nerve in patients with diabetic foot gangrene: a prospective parallel cohort study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30(7):435–440. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328360bd85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang GY, Chen YF, Dai WX, et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy increases electrical stimulation threshold of sciatic nerve: a prospective parallel cohort study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:4447–4455. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S277473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heschl S, Hallmann B, Zilke T, et al. Diabetic neuropathy increases stimulation threshold during popliteal sciatic nerve block. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116(4):538–545. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salviz EA, Onbasi S, Ozonur A, et al. Comparison of ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block properties in diabetic and non-diabetic patients: a prospective observational study. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(3):190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ten Hoope W, Hollmann MW, de Bruin K, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of lidocaine in a rodent model of diabetic neuropathy. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(3):609–619. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sertoz N, Deniz MN, Ayanoglu HO. Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin level and sciatic nerve block performance in diabetic patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(1):85–90. doi: 10.1177/1071100712460366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emanuel AL, Nieuwenhoff MD, Klaassen ES, et al. Relationships between type 2 diabetes, neuropathy, and microvascular dysfunction: evidence from patients with cryptogenic axonal polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(4):583–590. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewson DW, Bedforth NM, Hardman JG. Peripheral nerve injury arising in anaesthesia practice. Anaesthesia. 2018;73 Suppl 1:51–60. doi: 10.1111/anae.14140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ten Hoope W, Looije M, Lirk P. Regional anesthesia in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(5):627–631. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho HS, Kim S, Kim CS, et al. Effects of different anesthetic techniques on the incidence of phantom limb pain after limb amputation: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Korean J Pain. 2020;33(3):267–274. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2020.33.3.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lirk P, Flatz M, Haller I, et al. In Zucker diabetic fatty rats, subclinical diabetic neuropathy increases in vivo lidocaine block duration but not in vitro neurotoxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37(6):601–606. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3182664afb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen TS, Karlsson P, Gylfadottir SS, et al. Painful and non-painful diabetic neuropathy, diagnostic challenges and implications for future management. Brain. 2021;144(6):1632–1645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang J, Bhandari L, Messana J, Alkabbaa S, Hamidian Jahromi A, Konofaos P. Management of tourniquet-related nerve injury (TRNI): a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e27685. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masri BA, Eisen A, Duncan CP, McEwen JA. Tourniquet-induced nerve compression injuries are caused by high pressure levels and gradients - a review of the evidence to guide safe surgical, pre-hospital and blood flow restriction usage. BMC Biomed Eng. 2020;2:7. doi: 10.1186/s42490-020-00041-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dayan L, Zinmann C, Stahl S, Norman D. Complications associated with prolonged tourniquet application on the battlefield. Mil Med. 2008;173:63–66. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.1.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.