Abstract

The 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of bamboo mosaic potexvirus (BaMV) genomic RNA was found to fold into a series of stem-loop structures including a pseudoknot structure. These structures were demonstrated to be important for viral RNA replication and were believed to be recognized by the replicase (C.-P. Cheng and C.-H. Tsai, J. Mol. Biol. 288:555–565, 1999). Electrophoretic mobility shift and competition assays have now been used to demonstrate that the Escherichia coli-expressed RNA-dependent RNA polymerase domain (Δ893) derived from BaMV open reading frame 1 could specifically bind to the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA. No competition was observed when bovine liver tRNAs or poly(I)(C) double-stranded homopolymers were used as competitors, and the cucumber mosaic virus 3′ UTR was a less efficient competitor. Competition analysis with different regions of the BaMV 3′ UTR showed that Δ893 binds to at least two independent RNA binding sites, stem-loop D and the poly(A) tail. Footprinting analysis revealed that Δ893 could protect the sequences at loop D containing the potexviral conserved hexamer motif and part of the stem of domain D from chemical cleavage.

Bamboo mosaic potexvirus (BaMV) has a flexuous rod-shaped morphology (17) and comprises a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome with a 5′ m7GpppG structure and 3′ poly(A) tail. The 6,366-nucleotide (nt) genome [excluding the 3′ poly(A) tail] consists of five open reading frames and 94- and 142-nt untranslated regions (UTR) at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively (19). Open reading frame 1 (ORF1), encoding a 155-kDa polypeptide, can be translated directly from the virion RNA in an in vitro rabbit reticulocyte lysate (18). This polypeptide comprises three domains, a methyltransferase-like domain (24), an RNA helicase-like domain (12, 13), and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase domain (1, 15, 16), from the N to the C terminus. The full-length 155-kDa polypeptide and the C-terminal 80-kDa fragment (Δ893) containing the RdRp domain were overexpressed in Escherichia coli and demonstrated to have RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activities (16).

The 3′ UTR of single-stranded plus-sense viral genomic RNA, whether the end structure is a tRNA-like structure (TLS), a poly(A) tail, or a non-TLS heteropolymeric sequence, has been demonstrated to play variable roles in minus-strand promotion, provision of telomere, regulation of access to the minus-strand origin, and packaging (10). There are several lines of evidence from studying the replication of turnip yellow mosaic virus (9, 25, 26), brome mosaic virus (4, 29), turnip crinkle virus (3, 27), and the picornaviruses (14, 20, 21, 22, 23) showing that the specific sequence or the structure at the 3′ UTR is important for de novo minus-strand RNA synthesis. However, there are only a few cases, including encephalomyocarditis virus (7, 8) and hepatitis C virus (6), demonstrating that the viral RNA polymerase interacts directly with the 3′ UTR of its own genome.

The 3′ UTR of BaMV genomic RNA has been found by enzymatic and chemical structural probing to fold into four independent stem-loops and a tertiary pseudoknot structure (Fig. 1) (5). With a series of mutations introduced into the 3′ UTR of BaMV genomic RNA, it has been shown that both nucleotide sequences and structures are important for viral RNA accumulation in protoplasts (5, 31). The potexviral conserved hexamer motif in the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA and that in a defective RNA of clover yellow mosaic potexvirus were shown to play an important role in viral RNA replication (32). Although two tobacco proteins were identified to interact with the U-rich sequence at the 3′ UTR of potato virus X (28), the interactions between the RdRp and the sequence of the 3′ UTR have not been experimentally mapped.

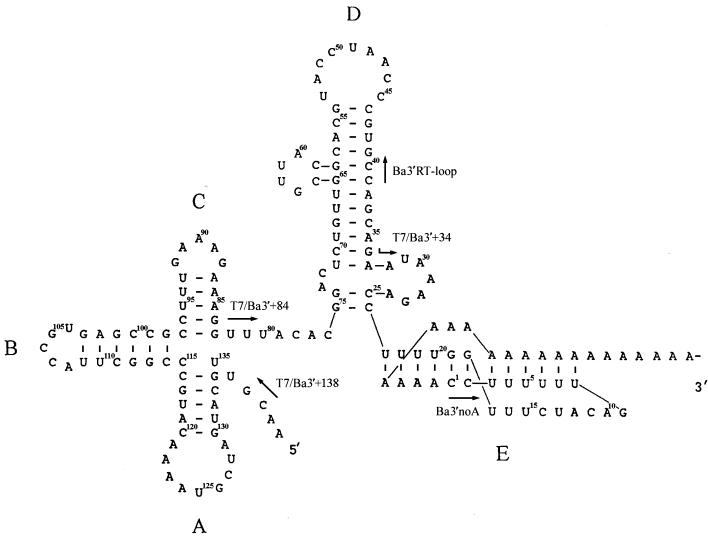

FIG. 1.

Secondary folding of the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA. Nucleotides are numbered from the 3′ end cytosine just upstream of the poly(A) tail. The arrows indicate the locations and the orientations of the primers used for PCR.

Due to the availability of the E. coli-overexpressed BaMV RdRp (16), we had an opportunity to investigate the interactions between RdRp and the 3′ UTR. Here, we present data derived from electrophoretic mobility gel shift assay (EMSA) and footprinting analysis to reveal the interactions of the purified recombinant RdRp Δ893 with the 3′ UTR of BaMV genomic RNA in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of recombinant RdRp.

Purification of the recombinant protein Δ893 RdRp was done as described previously (16), except that two columns were used for further purification before loading into the Talon metal affinity resin column. In brief, once the cells were pelleted and resuspended in 10 ml of sonication buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), sonication and centrifigation were used to clarify the extract. Then the cell extract containing recombinant RdRp was run consecutively through columns containing 20 ml of DEAE-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech) and 20 ml of P11 cellulose phosphate (Whatman). Finally, the BaMV recombinant RdRp in the extract was mixed with 10 ml of Talon metal affinity resin (Clontech), washed, eluted, and dialyzed against storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol).

Preparation of RNA transcripts.

To prepare the 3′ UTR transcripts derived from BaMV RNA for analyses, DNA fragments with different subdomains of the 3′ UTR containing the T7 promoter were amplified from infectious cDNA clone pBaMV/40A (W.-W. Chiu, C.-W. Peng, Y.-H. Hsu, and C.-H. Tsai, unpublished data) by PCR with different sets of primers listed in Table 1. Each set of primers, T7/Ba3′+138 and T40GG, T7/Ba3′+138 and Ba3′noA, T7/Ba3′+84 and Ba3′noA, T7/Ba3′+138 and Ba3′RT-loop, T7/Ba3′+34 and T40GG, and T7/Ba3′+34 and Ba3′noA, were used to synthesize the DNA fragments for direct transcription to produce the RNAs r138/40A, r138/noA, r84/noA, rABC, r34/40A, and r34/noA, respectively. Transcript r34/20A was derived from recombinant plasmid pBa3′+34, which had been constructed by PCR amplification with primers T7/Ba3′+34 and Ba3′(−) d(CGGGATCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT) and cloned into the SmaI site of pUC19. Therefore, r34/20 contained not only 20 adenylate residues but also 5 nonviral nucleotides derived from a BamHI restriction site when pBa3′+34 was linearized with BamHI for in vitro transcription. The 3′ tRNA-like structure (TLS) of cucumber mosaic virus, CMV3′TLS, was transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase from BstNI-linearized pT7CMV/tRNA (30). All transcripts were purified by gel electrophoresis, and the concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry. To prepare the 32P-labeled riboprobe, 5 pmol of r138/40A or r138/noA was 3′ end labeled with [32P]pCp with 20 U of T4 RNA ligase as described by England and Uhlenbeck (11).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used to prepare the 3′-terminal fragments

| Primer | Sequencea | Positionb |

|---|---|---|

| T7/Ba3′+138 | 5′GAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGTTGCATGATCG3′ | 138–126 |

| T7/Ba3′+84 | 5′GAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTTACACGGACT3′ | 84–71 |

| T7/Ba3′+34 | 5′GAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAATAAAGACCTTTT3′ | 34–20 |

| T40GG | 5′T40GG3′ | 2–1 |

| Ba3′noA | 5′GGAAAAAACTGTAGAAA3′ | 1–17 |

| Ba3′RT-loop | 5′GGCACGGGTTAGGTA3′ | 39–53 |

EMSA of the interactions between Δ893 RdRp and the labeled nucleic acids.

Various amounts of purified Δ893 RdRp were incubated with 2 fmol of 32P-labeled riboprobe in 20 μl of binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol) for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, 2 μl of gel loading buffer was added to each sample, loaded onto a 5% native polyacrylamide gel, and run with 0.5× Tris-boric acid-EDTA buffer at room temperature with ice pads. Results were analyzed and quantified with a BAS-1500 bioimaging analyzer (FUJIFILM). For competition assays, purified Δ893 RdRp was first incubated with unlabeled competitor RNAs in binding buffer for 5 min at room temperature, and then 2 fmol of 32P-labeled riboprobe was added and the mixture was incubated for another 10 min and electroporesed through a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. To improve binding efficiency, the amount of RdRp was optimized for use with different probes, with 14 and 30 ng of Δ893 RdRp used for 32P-labeled r138/40A and r138/noA, respectively. All EMSAs were done at least three times.

Quantitation of bands on autoradiographs.

The quantitation of images of labeled RNA bands was performed using a BAS-1500 bioimaging analyzer (FUJIFILM). The RNA competition efficiency, expressed as percent RNA bound, was calculated from the optical density of the bands corresponding to the bound and free RNA. The formula was as follows:

|

where c was no competitor added as a positive control.

DEPC footprinting analysis.

The condition used for modification on the N-7 position of adenine residues by diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) in footprinting analysis was modified from previous studies for structural probing (5, 31). The 20-μl reaction mixture containing the EMSA binding buffer described above and 1 μl of the 5′-end-labeled r84/40A transcripts (10,000 cpm; 3 ng) was incubated at 30°C for 15 min, with the addition of 20 or 100 ng of RdRp and a serial dilution of pure DEPC (ca. 97%; Sigma) from 0.5 to 4 μl to optimize the best condition. After the reaction, the mixtures were ethanol precipitated directly with 3 μg of yeast total RNAs (Boehringer Mannheim). The dried pellets were dissolved in 100 μl of water, phenol-chloroform extracted to remove the RdRp, and then ethanol precipitated. The dried RNAs were then dissolved in 20 μl of 1 M aniline(redistilled)-acetic acid (pH 4.3) solution directly and incubated at 60°C for 20 min in the dark, and then the cleaved RNA fragments were frozen at −80°C and freeze-dried under vacuum. The cleaved RNA fragments were resuspended in urea-containing loading buffer and resolved by electrophoretic separation on 8% denaturing (7 M urea) polyacrylamide gels.

RESULTS

Specific binding of recombinant Δ893 RdRp to the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA.

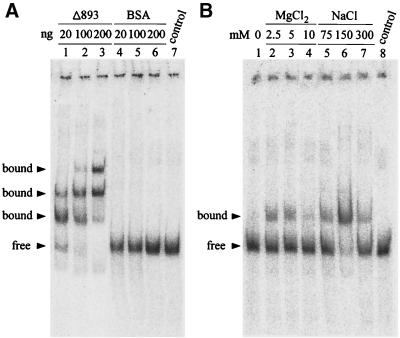

To determine whether purified recombinant BaMV Δ893 RdRp (16) could bind to the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA, the 32P-labeled 181-nt transcript r138/40A (Fig. 1, nucleotides from positions 1 to 138, 40 adenylate residues at the 3′ end, and three nonviral guanylate residues derived from the T7 promoter at the 5′ end) was used as a probe for EMSA. In the presence of 20 ng of Δ893 RdRp in the purification buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM MgCl2, 75 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol) (16), a major and a minor slower-migrating band were observed (Fig. 2A, lane 1) to migrate above the free probe (lane 7). When the concentration of Δ893 RdRp in the reaction was increased, multiple shifted bands were observed (Fig. 2A) that might have resulted from protein-protein interaction, as the protein tends to aggregate during purification. No shifted band could be observed when up to 200 ng of bovine serum albumin was added in the reaction along with the r138/40A probe under the same conditions to test the specificity of these interactions (lanes 4 to 6).

FIG. 2.

EMSA of the RNA-protein interaction for specificity and dependence on salt concentration. Shown are autoradiographs of binding reactions electrophoresed in 5% native polyacrylamide gels. Two femtomoles (126.5 pg) of r138/40A transcript was used in all reactions. (A) The indicated amounts of purified Δ893 RdRp and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were used; the control consisted of buffer only. (B) Effect of salt concentration. Twenty nanograms of Δ893 RdRp was used, and the indicated concentrations of MgCl2 and NaCl were added. A nonsalt addition (lane 1) and a buffer-only control (lane 8) were included.

To prevent the formation of multiple shifted bands that could result from unwanted protein-protein interactions, each component in the reaction buffer was optimized. The pH of Tris buffer ranged from 5.2 to 9.5, the temperature ranged from 0 to 37°C, and the concentration of Triton X-100 ranged from 0 to 0.1%; no obvious effects were observed (data not shown). The concentrations of MgCl2 or NaCl were, however, critical for binding, with 0 or 10 mM MgCl2 interfering most with binding (Fig. 2B). Band retardation was maximal at 150 mM NaCl (Fig. 2B, lane 6) and weaker in the presence of a lower salt concentration (lane 5). The finally optimized binding reaction was set as 20 ng of RdRp with 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 5% glycerol, producing one major shifted band that could be easily observed and quantified.

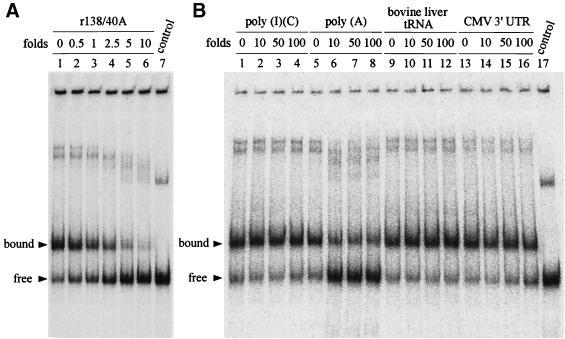

To investigate the binding specificity of Δ893 RdRp with r138/40A RNA, unlabeled RNAs were used as competitors during the binding reaction. Unlabeled r138/40A was shown to be a strong competitor as expected, whereas the double-stranded poly(I)(C), bovine liver tRNAs, and CMV 3′ UTR (30) could not compete with the labeled probe efficiently (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The binding of the radiolabeled r138/40A probe by Δ893 RdRp was inhibited almost completely by a 10-fold molar excess of unlabeled r138/40A (Fig. 3A, lane 6). The competition of bovine liver tRNAs and poly(I)(C) double-stranded RNA was very ineffective even when a 100-fold mass excess of RNAs was added in the reaction (Fig. 3B). The 254 nt of the CMV 3′ UTR was a weak competitor, with 50- and 100-fold mass excesses competing out only 10 and 30%, respectively, of the binding (Fig. 3B and Table 2). By contrast, poly(A) RNA (ca. 1.5 kb; Sigma) competed significantly, with 75% of the shifted band competed out in the presence of a 10-fold mass excess (Table 2). Poly(G) could compete out 30 and 50% of the shifted band with 10- and 100-fold mass excesses, respectively. Poly(C) showed even less competitive activity, with 20% at the 100-fold excess (Table 2). Poly(U) was also tested as a competitor that the runs of uridylate residues could pair with the probe containing 40 adenylate residues, and it aggregated at the well (not shown). To further test the efficiency of the poly(A) sequence as a competitor with the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA, 0.5-, 1-, 2.5-, 5-, and 10-fold mass excesses of poly(A) were used, and they showed 70.7% ± 1.9%, 49.9% ± 3.4%, 37.1% ± 1.7%, 30.9% ± 1.2%, and 25.5% ± 1.8% (means ± standard deviations) of competition values, respectively. These results indicated that poly(A) could compete out 30% of the probe which was bound to Δ893 RdRp with as low as a 0.5-fold mass excess. Overall, these results suggested that Δ893 RdRp binding to the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA was specific and perhaps involved the poly(A) tail.

FIG. 3.

Competition assays of Δ893 RdRp and 3′ UTR interaction with different RNAs. Purified Δ893 (14 ng) was incubated with buffer only (lane 1 in panel A and lanes 1, 5, 9, and 13 in panel B) or with indicated amounts of unlabeled RNAs for 5 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of 2 fmol (126.5 pg) of 32P-labeled r138/40A riboprobe and further incubation for 10 min. The competition activities were analyzed by EMSA. (A) Competition assays with the indicated molar fold excesses of unlabeled r138/40A (lanes 2 to 6). Lane 7, r138/40A riboprobe only. (B) Competition assays with mass fold excesses of unlabeled poly(I)(C) double-stranded homopolymer (lanes 2 to 4), poly(A) homopolymer (lanes 6 to 8), bovine liver tRNA (lanes 10 to 12), and CMV 3′ UTR. Lane 17, r138/40A riboprobe only.

TABLE 2.

Competition analyses of the interaction between Δ893 and the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA with different competitors

| Competitor | % Competition activity at indicated fold excess of competitora

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 50 | 100 | |

| Poly(I)(C) | 99.9 ± 0.4 | 104.1 ± 3.2 | 101.6 ± 1.4 |

| Bovine liver tRNA | 110.8 ± 3.9 | 105.5 ± 3.8 | 103.0 ± 2.8 |

| CMV 3′ UTR | 103.0 ± 3.9 | 90.1 ± 6.4 | 69.6 ± 0.3 |

| Poly(A) | 25.4 ± 2.7 | 20.2 ± 3.8 | 18.8 ± 3.0 |

| Poly(G) | 71.2 ± 7.3 | 59.3 ± 3.8 | 47.5 ± 1.9 |

| Poly(C) | 98.4 ± 0.4 | 93.6 ± 2.1 | 79.9 ± 8.5 |

The competition activities were analyzed by EMSA as described in the legend to Fig. 3. All EMSAs were done at least three times, and the percentages of RNA bound were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± standard deviations.

The poly(A) tail in the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA is involved in Δ893 RdRp binding.

Of all the heterologous competitors tested, the poly(A) RNA was shown to be the most efficient competitor (Table 2), suggesting that BaMV RdRp could bind the poly(A) sequence which is also part of the BaMV genomic RNA. Initiation of minus-strand synthesis within the poly(A) might be expected to involve RdRp binding. In order to test the involvement of the poly(A) sequence of BaMV RNA in RdRp binding, constructs with different numbers of adenylate residues or different parts of the 3′ UTR were created for use as competitor ligands (Fig. 1).

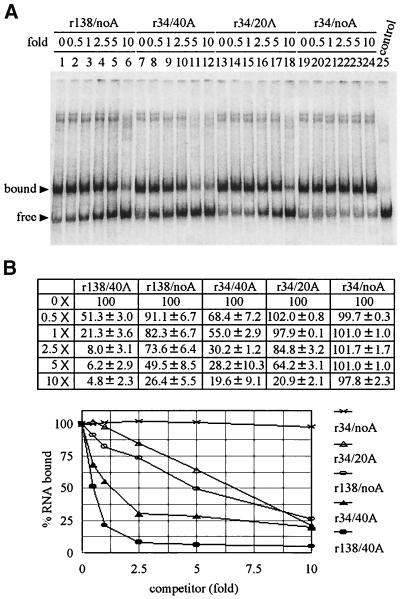

Unlabeled r138/40A with 40 adenylate residues at the 3′ end competed the binding of probe r138/40A up to 50% with a 0.5-fold molar excess relative to the probe. A 5-fold molar excess of r138/noA, containing no adenylate residues at the 3′ end, was required to obtain the same competition efficiency (Fig. 4). These results suggested that the presence of 40 adenylate residues could produce a 10-fold difference in competition efficiency; however, we could not rule out the possibility that this effect may also be contributed by the structural difference of the upstream sequence when 40 adenylate residues were removed from r138/40A. To prevent the possible interference of upstream sequence, transcript r34/40A, containing only the pseudoknot region (Fig. 1), was designed and used as a competitor. Results showed that the contribution of the upstream sequence of the 3′ UTR (domains ABC and D) to competition was around 2.5-fold (compare the amount of competitor needed for 50% competition) between r138/40A and r34/40A (Fig. 4). Based on the competition activity of r34/40A, two constructs, r34/20A and r34/noA, were designed to have 20 and no adenylate residues, and these showed five- to sixfold less competitive activity than that of r34/40A and no competitive activity, respectively (Fig. 4). Overall, these results suggested that the poly(A) sequence of the BaMV 3′ end does play an important role in Δ893 RdRp binding.

FIG. 4.

Binding of Δ893 RdRp to the 3′ UTR, investigated in competitive binding assays using different domains of the 3′ UTR RNAs and different lengths of poly(A) tail. Purified Δ893 RdRp (14 ng) was incubated with buffer only (100% control) or with the indicated molar excesses of unlabeled RNAs for 5 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of 2 fmol (126.5 pg) of 32P-labeled r138/40A riboprobe for further incubation for 10 min. The competition activities were analyzed by EMSA. (A) Representative experiments that have contributed to the quantitative data in panel B. All EMSAs were done at least three times, and the percentages of RNA bound were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Stem-loop D is another region of the binding sites for Δ893 RdRp.

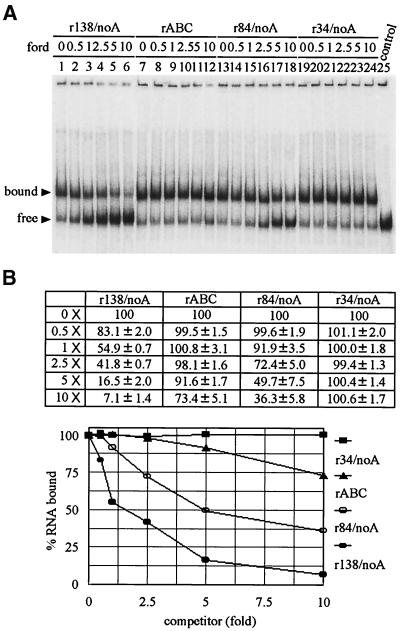

Results from competition analysis of r138/40A and r34/40A revealed that the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA was involved in binding with Δ893 RdRp (Fig. 4). In order to identify any specific region in the 3′ UTR capable of binding RdRp independent of the poly(A) tail, r138/noA was [32P]pCp labeled and used as a probe for gel shift analysis. Transcripts r138/noA, rABC, r84/noA, and r34/noA (Fig. 1, positions 1 to 138, 39 to 138, 1 to 84, and 1 to 34, respectively) were synthesized and used as competitors. Results showed that r34/noA and rABC had no or little competitive activity on the competition analysis and that r84/noA with the complete stem-loop D was an effective competitor (Fig. 5). Although r84/noA was a good competitor, it was still fivefold less efficient than r138/noA comprising the ABC and D domains. This suggested that there might be an interaction between the ABC and D domains that would enhance the competition activity. These results would also imply that stem-loop D could be one of the binding regions for Δ893 RdRp.

FIG. 5.

Mapping of the binding domains of Δ893 RdRp on the BaMV 3′ UTR by competition assays. Purified Δ893 RdRp (40 ng) was incubated with buffer only (100% for the control) or with the indicated molar fold excesses of unlabeled RNAs for 5 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of 2 fmol (95.88 pg) of 32P-labeled r138/noA riboprobe for further incubation for 10 min. The competition activities were analyzed by EMSA. (A) Representative experiments that have contributed to the quantative data in panel B. All EMSAs were done at least three times, and the percentages of RNA bound were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

The potexviral conserved hexamer motif interacts with RdRp.

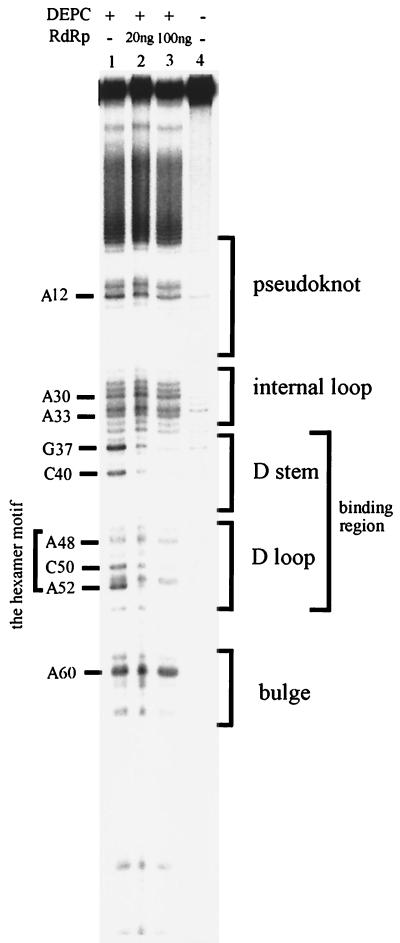

To address which region of domain D could be the possible binding site of BaMV RdRp, we performed a footprinting analysis. The condition used for footprinting was optimized for protein binding and chemical probing with DEPC to modify N7 of adenylate residues. Transcript r84/40A was 5′ end labeled and then treated with DEPC in the absence or presence of 20 or 100 ng of Δ893 RdRp, followed by aniline cleavage (Fig. 6). Nucleotides A60 in the bulge, A33 to A28 (AAUAAA, the putative polyadenylation signal) in the internal loop, and A12 and A10 in the loop of the 3′ pseudoknot showed equal densities of banding with or without the Δ893 RdRp addition, indicating that they were not protected by the RdRp. By contrast, the first adenylate residue, A52, of the hexamer motif in apical loop D showed either less detectable banding signal in the presence of RdRp (Fig. 6, lane 2) than in the absence of RdRp (Fig. 6, lane 1) or no detectable banding signal in the presence of RdRp (Fig. 6, lane 3). The last two adenylate residues of the hexamer motif, A48 and A47, showed lower cleavage efficiency in either the absence or presence of RdRp. In addition, some nonspecific cleavages (the nonadenylate residues, C50 in loop D and C40 and G37 in stem D) were observed in the absence of RdRp but protected in the presence of Δ893 RdRp. Overall, these results suggested that the polymerase domain of ORF1 of BaMV (Δ893 RdRp) could specifically bind to loop D containing the potexviral conserved hexamer motif (AC[C/U]UAA) and part of stem D of the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA. Unfortunately, the poly(A) binding region could not be resolved from this probe. Maybe there is protection on each probe molecule, but the location within the poly(A) tail varies, so that the overall modification cannot be noticeably diminished.

FIG. 6.

DEPC footprint of the Δ893 RdRp binding site on the r84/40 RNA. Show is an autoradiograph of the aniline cleavage products on a polyacrylamide gel containing 8% urea. Lanes: 1, aniline cleavage of DEPC-modified r84/40A RNA without Δ893 RdRp; 2 and 3, aniline cleavage of DEPC-modified r84/40A RNA in the presence of 20 and 100 ng of Δ893 RdRp, respectively; 4, aniline cleavage of r84/40A RNA without DEPC treatment. The positions of selected nucleotides in the r84/40A sequence are indicated on the left for reference.

DISCUSSION

The 3′ UTRs of positive-sense viral genomic RNAs are believed to contain sequences or structures participating in template recognition with viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase to initiate minus-strand RNA synthesis. With results derived from EMSA and competition experiments, we demonstrate that purified recombinant RdRp could bind specifically to the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA without any host factor from plants or other virus-encoded polypeptides. Hepatitis C virus NS5B and encephalomyocarditis virus 3Dpol are two other cases in which overexpressed RdRp was demonstrated to bind the conserved stem-loop structures of the viral 3′ end RNA (6) and both the 3′ UTR and poly(A) tail (7), respectively, without any other factor being involved. This differs from phage Qβ, in which the phage-encoded RNA polymerase subunit must form a complex with at least three host proteins to attain specificity for binding to Qβ RNA and related RNAs (2).

Although encephalomyocarditis virus 3Dpol was shown to have specific binding activity, it was unable to form a complex with the poly(A) alone or with the 3′ UTR RNA without a poly(A) tail (7). A pseudoknot structure derived from the 3′ UTR and poly(A) was proposed to be the signal for 3Dpol binding. Our findings indicate that BaMV Δ893 RdRp could specifically interact with the poly(A) sequence and stem-loop D of the 3′ UTR independently (Fig. 3b and Table 2). These results suggested that RdRp of BaMV ORF1 could contact at least two RNA binding sites, one comprising the hexamer conserved sequence and the other comprising the poly(A) tail. It has been shown that a sufficient length of poly(A) tail is required to maintain the integrity of the 3′ pseudoknot structure, which is important for efficient replication of BaMV RNA in vivo (31). It would be interesting to determine whether a similar poly(A) length is required for maintaining the pseudoknot structure and for RdRp binding. It is possible that the poly(A) sequence could be used as a template for the minus-sense RNA initiation. A mutant with a guanylate residue insertion at the fourth position of the poly(A) tail was inoculated into protoplasts and plants. The progeny recovered from cells was found to retain the guanylate residue at the same position (Chiu et al., unpublished). This result indicated that the initiation site of minus-sense RNA synthesis could use the poly(A) tail as a template and is possibly located downstream of the fourth nucleotide of the poly(A) tail. Therefore, the poly(A) tail of BaMV RNA might play several functional roles, including the formation of the pseudoknot structure for replication (31), acting as template for minus-sense RNA initiation (Chiu et al., unpublished), and simply in RNA stability, as that of mRNA in eukaryotic cells.

The other binding site on the RNA was located at stem-loop D, covering the entire loop and part of the stem. Since the conserved potexviral hexamer motif is housed in this loop, it is possible that this hexamer motif could play the role of a specificity determinant for RdRp recognition. Through this interaction, the RdRp could dock at the right position to bind the poly(A) region to initiate minus-sense RNA synthesis. The major drawback of our results was that the overexpressed RdRp used in experiments was only the C-terminal domain of BaMV ORF1. It is unknown whether the full-length form of this polypeptide, containing the N-terminal and middle portions of the methyltransferase and helicase domains, respectively, would show the same RNA binding. However, since Δ893 RdRp was demonstrated to be competent for polymerization activity (16) and the interaction with the 3′ UTR was specific, the interference of the other two domains would be expected to be low. Besides, the hexamer motif protected by RdRp in the footprinting analysis has been observed to play an important role in the replication of BaMV RNA in protoplasts. The specificity of each nucleotide has shown that the first nucleotide is purine specific, the second is pyrimidine specific, the third can be tolerated with mutations, and the rest of the nucleotides of the hexamer are restricted to UAA (12). The results of the in vivo protoplast assay involving full-length RdRp and the in vitro footprinting and gel shifting analyses with the truncated form of RdRp are correlated.

Functional analysis of the tertiary structure of the 3′ UTR of BaMV RNA revealed that maintaining the integrity of the terminal pseudoknot is important, and the deletion of the ABC domain seriously impaired virus accumulation in protoplasts (6, 32). It is possible that these regions could also interact with either a host- or virus-encoded factor(s). It will be interesting to identify this factor(s) and the relationship with RdRp, especially for the virus-encoded methyltransferase and helicase domains.

Overall, our results suggest that BaMV RdRp could specifically recognize the 3′ UTR, which provides the loop D conserved hexamer sequence (ACCUAA) and the poly(A) tail. This step could be important for the virus to initiate minus-sense RNA synthesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Theo Dreher at Oregon State University for discussion and editorial help.

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council (projects NSC 88–2311-B-005–040 and 88–2311-B-005–002-B11).

REFERENCES

- 1.Argos P. A sequence motif in many polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9909–9916. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal T, Carmichael G G. RNA replication: function and structure of Qβ replicase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:525–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter C D, Simon A E. Analysis of sequences and predicted structures required for viral satellite RNA accumulation by in vivo genetic selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2426–2432. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.10.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman R M, Kao C C. A minimal RNA promoter for minus-strand RNA synthesis by the brome mosaic virus polymerase complex. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:709–720. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng C-P, Tsai C-H. Structural and functional analysis of the 3′ untranslated region of bamboo mosaic potexvirus genomic RNA. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:555–565. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng J-C, Chang M-F, Chang S C. Specific interaction between the hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA polymerase and the 3′ end of the viral RNA. J Virol. 1999;73:7044–7049. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.7044-7049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui T, Sankar S, Porter A G. Binding of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA polymerase to the 3′-noncoding region of the viral RNA is specific and requires the 3′-poly(A) tail. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26093–26098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui T, Porter A G. Localization of binding site for encephalomyocarditis virus RNA polymerase in the 3′-noncoding region of the viral RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:377–382. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.3.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deiman B A L M, Koenen A K, Verlaan P W G, Pleij C W A. Minimal template requirements for initiation of minus-strand synthesis in vitro by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of turnip yellow mosaic virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3965–3972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3965-3972.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreher T W. Functions of the 3′ untranslated regions of positive strand RNA viral genomes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1999;37:151–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.England T E, Uhlenbeck O C. 3′-terminal labelling of RNA with T4 RNA ligase. Nature. 1978;275:560–561. doi: 10.1038/275560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Viral proteins containing the purine NTP-binding sequence pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8413–8440. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.21.8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgman T C. A new superfamily of replicative proteins. Nature. 1988;333:22–23. doi: 10.1038/333022b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson S J, Konings D A M, Sarnow P. Biochemical and genetic evidence for a pseudoknot structure at the 3′ terminus of poliovirus RNA genome and its role in viral RNA amplification. J Virol. 1993;67:2961–2971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.2961-2971.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koonin E V. The phylogeny of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of positive-strand RNA viruses. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2197–2206. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y-I, Cheng Y-M, Huang Y L, Tsai C-H, Hsu Y-H, Meng M. Identification and characterization of the Escherichia coli-expressed RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of bamboo mosaic virus. J Virol. 1998;72:10093–10099. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10093-10099.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin M T, Kitajima E W, Cupertino F P, Costa C L. Partial purification and some properties of bamboo mosaic virus. Phytopathology. 1977;67:1439–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin N-S, Lin F-Z, Huang T-Y, Hsu Y-H. Genome properties of bamboo mosaic virus. Phytopathology. 1992;82:731–734. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin N-S, Lin B-Y, Lo N-W, Hu C-C, Chow T-Y, Hsu Y-H. Nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of bamboo mosaic potexvirus. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2513–2518. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y-J, Liao C-L, Lai M M C. Identification of the cis-acting signal for minus-strand RNA synthesis of a murine coronavirus: implications for the role of minus-strand RNA in RNA replication and transcription. J Virol. 1994;68:8131–8140. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8131-8140.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melchers W J G, Henderop J G J, Slot H J B, Pleij C W A, Pilipenko E V, Agol V L, Galama J M D. Kissing of two predominant hairpin loops in the coxsackie B virus 3′ untranslated region is the essential structural feature of the origin of replication required for negative-strand RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1997;71:686–696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.686-696.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilipenko E V, Maslova S V, Sinyakov A N, Agol V L. Towards identification of cis-acting elements involved in the replication of enterovirus RNAs: a proposal for the existence of tRNA-like terminal structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1739–1745. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohll J B, Moon D H, Evans D J, Almond J W. The 3′ untranslated region of picornavirus RNA: features required for efficient genome replication. J Virol. 1995;69:7835–7844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7835-7844.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozanov N M, Koonin E V, Gorbalenya A E. Conservation of the putative methyltransferase domain: a hallmark of the Sindbis-like α supergroup of positive-strand RNA viruses. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2129–2134. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh R N, Dreher T W. Turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: initiation of minus strand synthesis in vitro. Virology. 1997;233:430–439. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh R N, Dreher T W. Specific site selection in RNA resulting from a combination of nonspecific secondary structure and -CCR- boxes: initiation of minus strand synthesis by turnip yellow mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. RNA. 1998;4:1083–1095. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song C, Simon A E. Requirement of a 3′-terminal stem-loop in in vitro transcription by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:6–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sriskanda V S, Pruss G, Ge X, Vance V B. An eight-nucleotide sequence in the potato virus X 3′ untranslated region is required for both host protein binding and viral multiplication. J Virol. 1996;70:5266–5271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5266-5271.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun J H, Adkins S, Faurote G, Kao C C. Initiation of (−)-strand RNA synthesis catalyzed by the BMV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: synthesis of oligonucleotide. Virology. 1996;226:1–12. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai C-H, Cheng J-H. The preparation of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex from virus infected plants. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China. 1998;22:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai C-H, Cheng C-P, Peng C-W, Lin B-Y, Lin N-S, Hsu T-H. Sufficient length of a poly(A) tail for the formation of a potential pseudoknot is required for efficient replication of bamboo mosaic potexvirus RNA. J Virol. 1999;73:2703–2709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2703-2709.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White K A, Bancroft J B, Mackie G A. Mutagenesis of a hexanucleotide sequence conserved in potexvirus RNAs. Virology. 1992;189:817–820. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90614-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]