Abstract

Abstract

Purpose

This paper aims to describe the study design and baseline characteristics of the Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort (SLCGC), which was established to assess the timing, pattern and determinants of growth faltering in infants and young children in Sri Lanka.

Participants

A retrospective cohort study was conducted among term-born babies (≥37-week gestation), currently aged between 12 and 24 months. A sample of 1875 mother–child pairs were recruited using two-stage stratified cluster sampling method. Data on sociodemographic characteristics, pregnancy care, feeding practices, childhood illnesses and home risk factors were collected through direct interviews with the caregivers. Pregnancy-related data were obtained from the pregnancy record. Birth weight, serial weight and length records and growth pattern were extracted from the Child Health and Development Record. Current weight and length of the children were measured directly.

Findings to date

The SLCGC serves as a comprehensive cohort study with a countrywide distribution in Sri Lanka, covering the three main residential sectors, namely the urban, rural and estate sectors in equal proportions. The majority of mothers were housewives (76.8%) and aged <35 years (77.9%). The proportions achieved secondary education in mothers and fathers were 69.0% and 63.7%, respectively. Approximately 30% of mothers were overweight or obese, while 15% were underweight on entry to antenatal care. Of the children, 49.2% were girls, 42.5% were the first-born children in their family and 34.2% were born by caesarean section. Mean birth weight was 2917 g (SD 0.406), with the proportion of low birth weight (less than 2500 g) being 13%.

Future plans

This data enables investigation of the effects of single exposures on child growth, as well as, more complex epidemiological analyses on multiple simultaneous and time-varying exposures. Data will be available for researchers for further analysis. The next wave of assessment is expected to be done after 12 months.

Keywords: Child, Paediatrics, Follow-Up Studies, Epidemiology

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study harnessed a wealth of longitudinal data recorded during pregnancy and early childhood and also performed direct interviews and anthropometric assessments.

This data enables investigation of more complex epidemiological analyses on multiple simultaneous and time-varying exposures on the growth of the child.

The findings would fill-up evidence gaps that are needed to inform policy and programme decisions to improve child malnutrition in the country.

Measures taken to assure quality of data are a major strength. Careful selection of the study team, adequate training and close monitoring process at different stages enhanced the validity of the study.

The cohort excluded children born before 37-week gestation, limiting the applicability of findings for preterm babies. Some weight and length data were missing in the records at certain time points.

Introduction

The first 1000 days of life has been identified as a crucial window of opportunity for interventions to optimise child growth.1 2 Growth failure in this period could adversely affect the subsequent physical growth and potential loss of human capital with poor cognitive development, low educational attainment and increased healthcare costs.2,4 However, child growth, especially in the first 24 months of life, most often assumes a dynamic pattern due to the influence of multiple factors over time. The maternal parameters, including prepregnancy and pregnancy characteristics, birth indicators, child parameters including the feeding patterns and illness as well as wider family and social environment could affect the growth of children. Providing a suitable environment for growth by optimising such factors is important to prevent growth faltering at this stage.3 5

The term ‘growth faltering’ is widely used to refer to a slower rate of weight gain in childhood than expected for age and sex. Globally, the lack of consensus on definitions of faltering growth has resulted in varying estimates of prevalence.6,8 A review on ‘new and old dimensions of growth faltering’ states that, criteria most frequently used for evaluating growth faltering include weight falling through two major centile lines on standard weight charts, weight falling below the 3rd centile or weight for height less than 2 SD below the mean for age and sex.7 The criteria used by the maternal and child health (MCH) programme in Sri Lanka to identify growth faltering at the population level involve recognition of any deviation, such as inadequate weight gain, no weight gain or drop in weight between two consecutive weight measurements of a child’s growth curve compared with the reference curve based on WHO Child Growth Standards, 2006.9

WHO’s Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition with results from developing countries shows that mean weight starts to falter at about 3 months of age and continues to decline until the catch-up growth is observed after 18 months.5 10 However, the timing of growth faltering could vary in different countries, depending on the mix of risk factors in each setting.10 Hence, identifying the pattern of growth faltering and the risk factors contributing to such faltering at different stages is of paramount importance to carry out tailor-made nutritional interventions.

Malnutrition remains a challenging and unresolved public health problem in Sri Lanka,11 and the importance of early childhood nutrition to development outcomes is well recognised. A single-centre cross-sectional descriptive study conducted in Sri Lanka with a sample of 254 children aged 0–24 months has revealed a high prevalence of growth faltering until 18 months of age.12 In this study, drops in mean weight-for-age and length-for-age Z scores were noted at 4 months. Weight faltering, compared with birth weight, was noted in 50.4% of infants by 4 months of age. Of them, the majority (76.6%) continued to show similar trends at 12 months. However, there was no population-based study to confirm the above findings.

Factors affecting growth

The global literature reveals the potential of interaction of direct and indirect health factors as well as direct and indirect non-health factors leading to growth faltering. The direct factors include breastfeeding status, dietary diversity, supplementation, illness etc, while the indirect factors include household wealth, maternal and paternal education and sanitation standards etc.13,15

A pooled analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data from 35 lower-middle income countries found that maternal nutritional status such as height and body mass index (BMI), and poor household socioeconomic conditions such as household wealth and maternal education, as the leading factors associated with childhood anthropometric failure.15 16 However, the cross-sectional nature of data is recognised as a major limitation in making any causal inferences in this regard.

A recent Sri Lankan study revealed that onset of growth faltering is seen very early in life in the majority of Sri Lankan infants.12 Persistent exclusive breastfeeding without starting complementary feeding was evident, despite detecting growth faltering. This was also confirmed by other Sri Lankan studies.17 Suboptimal complementary feeding practices among infants and young children were elicited through a mixed method study.18 In conforming to Ministry of Health recommendations,19 most caregivers had introduced solid foods to their children around 6 months of age. Further, the contribution of sociodemographic factors could also be relevant, for example, women’s participation in the labour force and their engagement in the agriculture sector is predictive of higher stunting rates, while participation in the service sector is protective against stunting according to the findings of a review by Halimatunnisa et al.20

Purpose of the Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort (SLCGC)

Growth is a dynamic process, and it is important to detect any abnormal growth early and to investigate its onset, causes and consequences to provide required interventions. We hypothesise that there are multiple factors operating at the individual, household and organisational levels, leading to inadequate growth in infants and young children, and these factors may vary according to the timing of growth faltering. Hence, the growth, as well as its determinants, should be explored in relation to age of child.

Purpose of the SLCGC is to describe the timing and pattern of growth faltering in infants and young children and to determine the evolution of maternal, child and social factors affecting their growth over time, in order to assist better planning of interventions. This paper describes the study design and baseline characteristics of the SLCGC.

Cohort description

Cohort design and population

The aim of the cohort was to sample children 12–24 months of age covering all three residential sectors across the country (urban, rural and the estate consisting of plantations), with longitudinal data being collected retrospectively from the prepregnancy stage. The cohort design intended to capture growth parameters and associated factors at defined time points within the first 1000 days of life, from conception up to 2 years.

In the Sri Lankan state preventive health system, pregnant women and children are registered with the Medical Officer of Health (MOH) for the provision of clinic based and domiciliary MCH services. Around 90% of the respective target populations (89.8% of pregnant women, 90.8% of infants) obtain preventive healthcare through this service.21 Public health midwives (PHMs) are the frontline healthcare providers in the MOH areas who provide field level MCH services. The PHM maintains registers and records relevant to MCH care, such as Register of Pregnant Mothers, Birth and Immunization Register and personal health records such as pregnancy record (containing details of the mother before and during pregnancy) and the Child Health and Development Record (CHDR) (containing birth details, immunisation, health and development screening, micronutrient supplementation and growth monitoring data). During the first 2 years of life, weight is measured every month, and length at 4, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months.

Recruitment of participants for the present cohort was carried out during October and November 2023. Mother–child pairs of term babies (born at 37-week gestation or later) currently between 12 and 24 months of age were selected from the Birth and Immunization Registers. Exclusion of preterm babies was due to the fact that their growth pattern is different from that of term babies.22 23 The children with less than 4 wt recordings in their CHDR during the first 12 months and those with chronic medical conditions and structural deformities causing feeding difficulties were excluded.

Cohort sampling

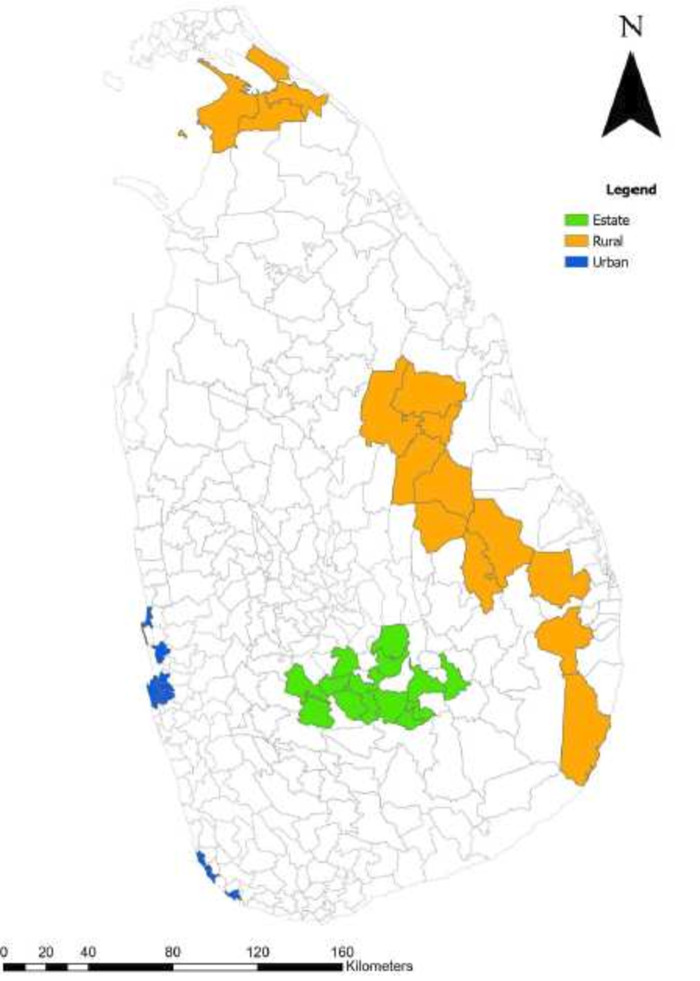

A total of 1875 mother–child pairs were recruited using a two-stage stratified cluster sampling method. Stratification was carried out at the level of residential sector as defined by the Department of Census and Statistics24 with approximately 600 mother–child pairs selected from each sector, namely urban, rural and estates. In the first stage, three districts each from the urban (Colombo, Gampaha and Galle) and rural sectors (Kilinochchi, Polonnaruwa and Ampara) and two districts from the estate sector (Nuwaraeliya and Badulla) were purposely selected as the most appropriate districts to represent the respective sector. An MOH area was considered a cluster. In the second stage, clusters (MOH areas) were sampled from a list comprising all MOH divisions in the selected district. MOH areas with the highest percentage of urban population were selected for the urban stratum. Similarly, the MOH areas with the highest percentage of rural and estate populations were selected for the rural and estate strata, respectively. 45 clusters were selected, and from each cluster 40 mother–child pairs were sampled systematically according to the Birth and Immunization Registers of the PHMs. Figure 1 illustrates the MOH areas selected for the cohort.

Figure 1. Map of Sri Lanka showing the Medical Officer of Health areas selected for the cohort.

Measurements and procedure

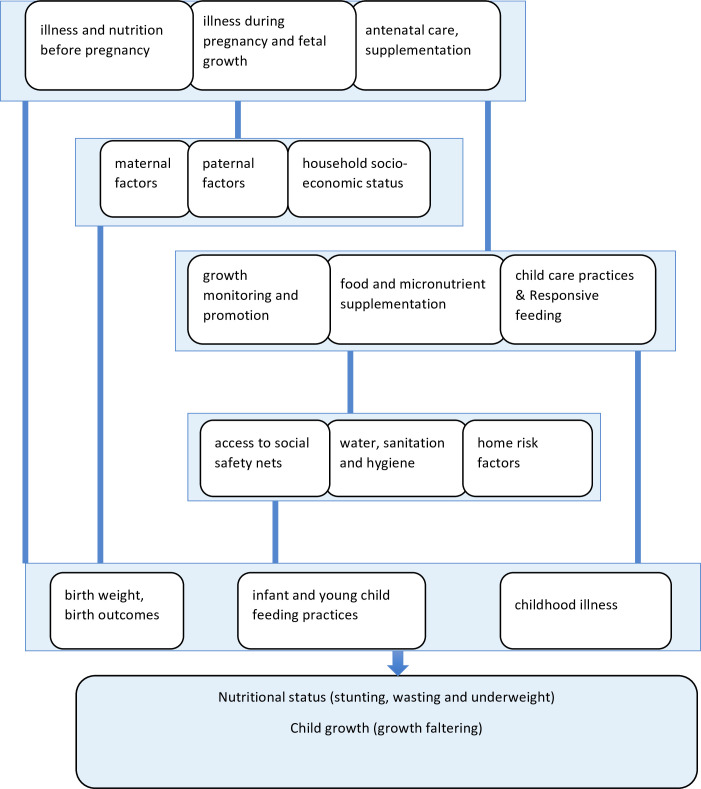

Development of the study tools of the cohort and selecting the appropriate variables and measurements were guided by a conceptual framework, as illustrated in figure 2. A structured data collection tool was developed to gather data from the mothers or caregivers and from relevant health records, including the pregnancy record and the CHDR. This was pretested in a similar setting, after which minor modifications were made.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of the Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort Study.

Measurement taken for outcome assessment

Weights and lengths recorded serially in the CHDR were extracted in a longitudinal manner. Weight at birth and monthly intervals were available with the date of weighing in the B-portion of the CHDR. Length at birth and subsequent time points were also available with measurement date in the same record. On the date of the interview, the weight and the length of the child were measured by the trained enumerators adhering to the standard protocol. Visual inspection of the weight-for-age chart, based on WHO multicountry growth reference curves25 in the local CHDR of the child, was carried out by the enumerators, and any presence of any growth faltering (ie, a downward deviation, flattening or dip in the growth curve) was recorded.

Measurements taken for exposure assessment

Detailed information on exposure status was collected using a life course approach. Pregnancy-related information, including illness before and during pregnancy, use of micronutrients, blood haemoglobin level, prepregnancy/booking visit BMI and weight gain during pregnancy, was gathered from the pregnancy record. Data on haemoglobin and weight were obtained at booking visit (first trimester), second trimester and before the delivery (third trimester). Baseline characteristics of the child, including the date of birth, sex, parity, singleton or multiple pregnancy, gestational age at birth and measurements recorded at birth such as birth weight, length and head circumference, were extracted from the CHDR. The mode of delivery, and the reason for caesarian delivery if performed, was collected through interviews.

In order to generate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) indicators, details on breastfeeding practices, complementary feeding, including the timing, frequency, decision-making on feeding and responsive feeding behaviours, were assessed by questioning the principal caregiver. Feeding of specific food items at each month was collected through a recall, which can also be used to assess dietary diversity at different ages. Longitudinal data on feeding different liquids and solid food items every month from birth up to the current age were inquired from the mother or caregiver. Additionally, micronutrient supplement use and food supplements given to the child were also gathered.

Illnesses of the child were recorded longitudinally at 3 monthly intervals during the first year and 6 monthly intervals during the second year of life. Respiratory illness, fever, diarrhoea, urine infection and other illness requiring hospitalisation were assessed. An episode of respiratory tract infection was defined as an illness with upper respiratory symptoms and signs, which lasted more than 48 hours with or without fever. An episode of diarrhoeal illness was defined as watery loose stools with more than three bouts per day lasting more than 48 hours, with frequent passage of formed or pasty stools seen in breastfed babies being excluded. Urinary tract infection and other illness requiring hospitalisation was considered if it was indicated in medical records of the child. Any change in the diet of the child during illness was gathered during the interview.

Several sociodemographic and family level factors were assessed using the questionnaire. The variables included education level and employment of both mother and father, income of the family, maternity leave, housing conditions, water and sanitation and indicators to assess the Household Wealth Index. Availability of social safety nets for the family and presence of home risk factors as per the guidelines of the Ministry of Health26 was also collected.

Tables1 2 provide a description of the key variables with the time period relevant to the information and the source of information.

Table 1. Key exposure variables assessed at different time points before or during pregnancy and at delivery of the mother.

| Measurement | Period before or during pregnancy | ||||

| Pre conception | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | Delivery | |

| Illness | |||||

| Diabetes | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Hypertension | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Heart disease | ● | ● | |||

| Fever | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Hospitalisation | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| BMI | ● | ||||

| Weight | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Height | ● | ||||

| Haemoglobin | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Food and micronutrient supplementation | |||||

| Iron | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Folate | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Calcium | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Vitamin C | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Thriphosa | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Mode of delivery | ● | ||||

| Gestational age at birth | ● | ||||

● Obtained from pregnancy record.

◆ Inquired from history.

BMIbody mass index

Table 2. Key variables assessed at different time points from birth up to 24 months of age of the child.

| Measurement | Age of child in months | ||||||||||||||

| Birth | 0 to <1 | 1 to <2 | 2 to <3 | 3 to <4 | 4 to <5 | 5 to <6 | 6 to <7 | 7 to <8 | 8 to <9 | 9 to <10 | 10 to <11 | 11 to <12 | 12 to <18 | 18 to 24 | |

| Parental measurements | |||||||||||||||

| Weight of mother | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||

| Height of mother | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||

| Weight of father | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||

| Height of father | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||

| Measurements at birth | |||||||||||||||

| Birth weight | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Length at birth | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Head circumference | ● | ||||||||||||||

| IYCF practices | |||||||||||||||

| Breastfeeding | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||

| Any semisolid solid food | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||

| Water | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||

| Any powdered milk (formula or other) | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||

| Fresh milk | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||

| Specific water-based liquids* | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||

| Specific semisolid/solid food† | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Specific unhealthy food‡ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Responsive feeding§ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||||||

| Childhood illness | |||||||||||||||

| Admitted to special care baby unit | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Fever | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||

| Respiratory illness | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||

| Diarrhoea | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||

| Urinary tract infection | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||

| Feeding during illness¶ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||

| Food/micronutrient supplementation | |||||||||||||||

| Vitamin A | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||||||||||||

| Multiple micronutrient powder | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ||||||||||||

| Food supplementation | ◆ | ◆ | |||||||||||||

| Anthropometry | |||||||||||||||

| Weight of child | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● ■ | ● ■ | |

| Length of child | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● ■ | ● ■ | |

| Growth faltering | |||||||||||||||

| Onset of growth faltering | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Reasons for growth faltering | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Action taken during growth faltering | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

● Obtained from pregnancy record or Child Health and Development Record.

◆ Inquired from history.

■ Measured on-site (measurements were taken during the interview according to the current age of the child).

Inquired about specific water-based liquids separately: fruit juices and rice kanji.

Inquired about specific food items under solid/semisolid food separately: starchy food, yellow-colour vegetables, other vegetables, yellow-colour fruits, others fruits, legumes, flesh food, eggs.

Inquired about specific unhealthy food separately: sweets, biscuits, malted beverages and sodas/colas.

Inquired responsive feeding referring to the current time period.

Inquired about feeding during illness, referring to any episode of illness in the past.

IYCFinfant and young child feeding

Data collection and analysis

Data collection

Enumerators were trained to administer the questionnaire and to conduct anthropometric measurements. National and regional level clearance was obtained to conduct face-to-face interviews and to collect data from the relevant records. The selected participants were requested via telephone to come to a centre within their village or estate for data collection. If they did not respond for three separate attempts of contact, or when a participant did not have a means of communication, a home visit was made for this purpose. If all attempts failed, the next eligible child was sampled. It was explicitly mentioned that participation is voluntary and that all data would be confidential. All study material was in the local language (Sinhala/Tamil). The research team regularly monitored the data collection in the field.

Two enumerators were assigned to collect data from one mother–child pair. Photo images of the relevant sections of the pregnancy record, and CHDR including the growth charts (weight-for-age chart, length-for-age chart, weight-for-length chart) and the table for weight and length records, were obtained. The data was entered into a tailor-made online database in parallel to data collection during the field work. The current database contains password protected, deidentified data along with the images of the documents as a single PDF file under serial numbers.

Statistical analyses

Data processing

Frequency distributions were generated for all variables, and the relevant records (pregnancy record or CHDR) were revisited when there were missing data or extreme values for appropriate corrections.

Repeatability of certain variables for which the same information was gathered from two different approaches was assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for numeric data or by Cohen’s Kappa for categorical data. High and significant ICC were reported for the following variables: age of child according to mother’s history versus calculated age by date of birth (ICC=0.99; 95% CI 0.650 to 0.997); mothers height according to pregnancy record versus height measured on site; the last weight record in the CHDR versus weight measurement on-site during the survey. Percent agreement was tested for some categorical variables, that is, giving breastmilk, feeding powdered milk and introducing solid/semisolid food, and a high percentage agreement with a significant Cohen’s Kappa was found for all these variables.

Basic statistical analysis

Data were summarised into frequency tables illustrating the characteristics of cohort participants. New variables were generated using the recode option in the statistical package in order to transform data into standard or meaningful categories, such as maternal age group, child age group, educational levels, birth interval, birth weight etc.

BMI was calculated and classified according to the WHO definition of BMI for adults.27 Household Wealth Index was calculated by using data on main sources of drinking and cooking water, type of toilet facility, main sources of lighting, cooking fuel, main material used in floor, roof and walls of the house, ownership of the house, household assets and animal husbandry.28 Principal component analysis was performed to create an asset score, which was divided into five quintiles for comparison purposes.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.029 and SPSS 20.0.30 Anthropometric measurements were transformed into weight-for-age Z score, length-for-age Z score and weight-for length Z score as per WHO growth reference standards31 using AnthroPlus Software.32

Quality of data

In order to ensure the reliability and validity of collected information, investigators followed the best practices given below:

High standards were maintained in recruiting suitable persons with experience in field work, and adequate training was provided on interviewing techniques and the subject matter of the survey. All team members were given a 2-day classroom and a field day training programme, including training on anthropometric measurements of a child.

Interviews were conducted in a language conversant to the respondents. Data collection tools were available in all three languages. Interviews were conducted at a time most convenient to the respondents through an appointment system.

Interviewing etiquettes were strictly followed by the enumerators and survey supervisors closely monitored the process.

The interviewer assured the respondents of the confidentiality of information, indicated the time required for completing the interview and sought their approval to continue with the survey.

Best practices followed to ensure quality of data collection:

The survey consultants and data managers undertook random field visits to ensure surveys are conducted appropriately and acceptably.

Completed questionnaires were scrutinised first by the supervisors to ensure completeness and accuracy of the filled responses and incomplete questionnaires were returned to the field enumerator to complete the same. Entered data were randomly checked to ensure accuracy.

The survey teams conducted further quality checking before entering the data into the online database.

Patient and public involvement

At the stage of designing the study, three group discussions were held with the mothers of children under 2 years of age from the three residential sectors, and their views were considered in defining certain variables such as types of food given to children, responsive feeding behaviour and childhood illness according to their sociocultural context. It is expected to inform the relevant findings to participants during the second wave of assessment in this cohort after 1 year.

Baseline findings

Characteristics of the participants

The cohort covered three main residential sectors of the Sri Lankan population namely the urban, rural and estate, in nearly equal proportions (table 3). The majority of mothers of the children were less than 35 years of age (77.9%) and housewives (78.4%). The proportion of mothers who completed General Certificate of Education (ordinary level) was 69% compared to 63.7% of fathers. A great majority of fathers (94.4%) were engaged in some form of economic activity. Approximately 30% of mothers were overweight or obese, while 15.0% were underweight at the time of registering for pregnancy.

Table 3. Characteristics of parents and their children recruited in the cohort.

| Characteristics | N | % |

| Parental characteristics | ||

| Residential sector | ||

| Urban | 646 | 34.5 |

| Rural | 593 | 31.6 |

| Estate | 636 | 33.9 |

| Maternal age category | ||

| <35 years | 1460 | 77.9 |

| 35 years and above | 415 | 22.1 |

| Mother’s education level | ||

| Passed grade 5 or less | 64 | 3.4 |

| Passed grade 6–10 | 518 | 27.60 |

| Passed ordinary level | 797 | 42.50 |

| Passed advanced level | 393 | 21.0 |

| Degree and above | 103 | 5.5 |

| Mother’s occupation | ||

| Employed government sector | 81 | 4.3 |

| Employed private sector | 107 | 5.7 |

| Self-employed/own business | 61 | 3.3 |

| Casual worker | 156 | 8.3 |

| Take care of housework | 1470 | 78.4 |

| Father’s education level | ||

| Passed grade 5 or less | 53 | 2.8 |

| Passed grade 6–9 | 614 | 32.7 |

| Passed ordinary level | 821 | 43.8 |

| Passed advanced level | 300 | 16.0 |

| Degree and above | 74 | 3.9 |

| Data not available | 13 | 0.7 |

| Father’s occupation | ||

| Employed government sector | 233 | 12.4 |

| Employed private sector | 618 | 33.0 |

| Self-employed/own business | 376 | 20.1 |

| Casual worker | 544 | 29.0 |

| Take care of housework | 84 | 4.5 |

| Data not available | 20 | 1.1 |

| Wealth Index Quintile | ||

| Lowest | 375 | 20.0 |

| Second | 375 | 20.0 |

| Middle | 378 | 20.2 |

| Fourth | 372 | 19.8 |

| Highest | 375 | 20.0 |

| Prepregnancy BMI category (kg/m2) | ||

| Less than 18.5 | 280 | 14.9 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 841 | 44.9 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 413 | 22.0 |

| >30 and higher | 142 | 7.6 |

| Data not available | 199 | 10.6 |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Birth interval (years) | ||

| No previous birth | 796 | 42.5 |

| 1–2 years | 180 | 9.6 |

| 3–4 years | 345 | 18.4 |

| 5 years or more | 554 | 29.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 922 | 49.2 |

| Male | 953 | 50.8 |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Caesarian | 642 | 34.2 |

| Vaginal | 1233 | 65.8 |

| Birth order | ||

| First | 796 | 42.5 |

| Second | 640 | 34.1 |

| Third or higher | 439 | 23.4 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | ||

| 37–37+6 | 359 | 19.1 |

| 38–38+6 | 615 | 32.8 |

| 39–39+6 | 475 | 25.3 |

| ≥40 | 426 | 22.7 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | ||

| Birth weight category (g) | ||

| <2000 | 20 | 1.1 |

| 2000–2499 | 224 | 11.9 |

| 2500–2999 | 842 | 44.9 |

| 3000–3499 | 644 | 34.3 |

| >3500 | 145 | 7.7 |

| Current age of child (months) | ||

| 12–14 | 461 | 24.6 |

| 15–17 | 422 | 22.5 |

| 18–20 | 417 | 22.2 |

| 21–24 | 575 | 30.7 |

| Total | 1875 | 100.0 |

BMIbody mass index

Of the children, 49.2% were girls, 42.5% were the first-born children in their family and 34.2% were born by caesarean section. Their ages ranged from 12 months to 24 months, and the number of children in the age 21–24 months and 12–14 months were somewhat higher than other age categories. This cohort includes only term-born children, and the mean birth weight was 2917 g (SD 406), with the proportion of low birth weight (less than 2500 g) being 13.0%.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

The SLCGC serves as a comprehensive cohort study with a countrywide distribution in Sri Lanka, covering the three main residential sectors namely the urban, rural and estate sectors. It captures data on a wide spectrum of individual, household and societal determinants of child growth commencing from the prepregnancy period up to the current time point. This is one of the few studies that harnessed a wealth of longitudinally recorded data during pregnancy and early childhood, supplemented with direct interviews and anthropometric assessments. The findings will fill-up evidence gaps that are needed to inform policy and programme decisions to improve child malnutrition in the country, such as the predictors of low birth weight, and timing and determinants of early growth faltering etc. This data enables investigation of the effects of single exposures on child growth, as well as, more complex epidemiological analyses on multiple simultaneous and time-varying exposures on the growth of the child. Furthermore, potential confounders and effect modifiers are available to model the outcome through advanced statistical modelling.

Measures and precautions to assure quality of data is one major strength of the SLCGC. Careful recruitment of the study team, adequate training and close monitoring process at different stages of the study enhanced the validity data.

All children in the cohort had completed at least 12 months of age at the time of enrolment. This enabled retrospective assessment of exposures during the first 12 months of life of all children.

Limitations

The SLCGC is not fully representative of the Sri Lankan child population with respect to socioeconomic diversity of the country. The study may have not adequately covered the upper socioeconomic strata of the population since those may not register for field-based services provided through the state health sector.

Secondary data were extracted from the pregnancy records and CHDR. Certain weight measurements and higher number of length measurements were not available in the CHDR B-portions. Anthropometric measurements extracted from the records had been taken for the purpose of service delivery, therefore may not be ideally suited for research purposes. Recall bias is a problem when collecting the details regarding breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices.

The cohort did not enrol children born preterm, that is before 37-week gestation, and this limits the interpretation of findings regarding growth of preterm babies. As the cohort did not include preterm births, the proportion of low birth weight children is an under-representation of the overall expected low birth weight prevalence.

It is noteworthy to understand that this cohort was followed-up in the backdrop of an ongoing economic crisis in the country. Children recruited to the cohort were those born between October 2021 and September 2022, thus their conception, gestational period, birth and postnatal period would have been exposed to economic crisis and its consequences. Further, there is no clear starting point or endpoint of the economic crisis and all that can be stated is that the study outcomes could have been influenced to a varying degree by the economic crisis. Thus, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results.

Way forward (future plans)

Further analysis of available data

Data analyses will be continued according to the aims of the cohort. Analysis will be extended to identify the determinants of low birth weight including the effect of weight gain and other parameters during pregnancy, using multivariate regression models. Growth faltering at different time points will be correlated with the concurrent events including IYCF practices, childhood illness, care practices and utilisation of health services. Furthermore, longitudinal data analysis techniques will be applied to explain different growth patterns. Current growth status in terms of stunting, wasting and underweight will be analysed against a range of sociodemographic and other predictors. Correlation of growth faltering with other measures of anthropometric deficits at different points in time would also be investigated using this data.

Continuation of the cohort

The next wave of assessment is expected to be done after 12 months of recruitment. SLCGC team recommends that this cohort be extended with clearly defined waves of assessment through their childhood and adolescence.

Acknowledgements

Permission to conduct this study was granted by the Director General of Health Services of the Ministry of Health. The Family Health Bureau and the Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians facilitated this process. The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to UNICEF Sri Lanka Country Office for financial and technical support. Provincial Directors of Health Services of the selected provinces, Regional Directors of Health Services, Director General and Director Health of the Plantation Human Development Trust and the Chief MOH of the Colombo Municipal Council extended their fullest cooperation to conduct this study. The authors wish to acknowledge the South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network for conducting the field work of this study.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was funded by the UNICEF Sri Lanka Country Office.

Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-088269).

Data availability free text: Deidentified microdata of the cohort will be available for researchers, on reasonable request with clear plan of utilisation of such data conforming to guidelines for data dissemination. Requests for statistical code and anonymised data may be made to the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by ethics review committee of the Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians (ERC Ref No: SLCP/ERC/2023/08). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort (SLCGC) Group: Vithanage Pujitha Wickramasinghe, Guwani Liyanage, Shreenika D S Weliange, Yasaswi N Walpita, Indika Siriwardena, Kunarathinum Partheepan, Suganya Yogeswaran, Dhammica Rowel, Abner Daniel, Hiranya S Jayawickrama, Upul Senarath, Harendra De Silva, Jagath C Ranasinghe, Gitanjali Sathiadas, Ishani Rodrigo, Amali Dalpatadu, Heshan Jayaweera, Wasana Bandara, Deepthi Samarage. SLCGC was established by the Sri Lanka College of Pediatricians in collaboration with the Family Health Bureau of the Ministry of Health Sri Lanka, South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network and UNICEF Sri Lanka. SLCGC seeks further collaboration with researchers who are interested in child nutrition and growth in order to conduct advanced analysis of longitudinal data. Deidentified micro-data of the cohort will be available for researchers, upon reasonable request to the corresponding author with clear plan of utilization of such data. Collaborative work is also required to extend follow-up and widen its scope.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Data collection and analysis section for further details.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Contributor Information

Vithanage Pujitha Wickramasinghe, Email: pujitha@pdt.cmb.ac.lk.

Guwani Liyanage, Email: guwani@sjp.ac.lk.

Shreenika De Silva Weliange, Email: shreenika@commed.cmb.ac.lk.

Yasaswi Niranjala Walpita, Email: yasaswi@commed.cmb.ac.lk.

Indika Siriwardena, Email: indikaips@gmail.com.

Kunarathinam Partheepan, Email: coolparthee@gmail.com.

Suganya Yogeswaran, Email: ysuganya@yahoo.com.

Dhammica Rowel, Email: drowel@unicef.org.

Abner Daniel, Email: adaniel@unicef.org.

Hiranya Senani Jayawickrama, Email: senanij@hotmail.com.

Upul Senarath, Email: upul@commed.cmb.ac.lk.

Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort (SLCGC), Email: paedsslcp@gmail.com.

Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort (SLCGC) Group:

Harendra De Silva, Jagath C Ranasinghe, Gitanjali Sathiadas, Ishani Rodrigo, Amali Dalpatadu, Heshan Jayaweera, Wasana Bandara, Deepthi Samarage, Vithanage Pujitha Wickramasinghe, Guwani Liyanage, Shreenika D S Weliange, Yasaswi N Walpita, Indika Siriwardena, Kunarathinum Partheepan, Suganya Yogeswaran, Dhammica Rowel, Abner Daniel, Hiranya S Jayawickrama, Upul Senarath, Harendra De Silva, Jagath C Ranasinghe, Gitanjali Sathiadas, Ishani Rodrigo, Amali Dalpatadu, Heshan Jayaweera, Wasana Bandara, and Deepthi Samarage

Sri Lanka Child Growth Cohort (SLCGC) Group:

Vithanage Pujitha Wickramasinghe, Guwani Liyanage, Shreenika D S Weliange, Yasaswi N Walpita, Indika Siriwardena, Kunarathinum Partheepan, Suganya Yogeswaran, Dhammica Rowel, Abner Daniel, Hiranya S Jayawickrama, Upul Senarath, Harendra De Silva, Jagath C Ranasinghe, Gitanjali Sathiadas, Ishani Rodrigo, Amali Dalpatadu, Heshan Jayaweera, Wasana Bandara, and Deepthi Samarage

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2013;382:427–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgiadis A, Penny ME. Child undernutrition: opportunities beyond the first 1000 days. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:S2468-2667(17)30154-8. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin-Chung J, Mertens A, Colford JM, Jr, et al. Early-childhood linear growth faltering in low- and middle-income countries. Nature New Biol. 2023;621:550–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shekar M, Kakietek J, Dayton Eberwein J, et al. An Investment Framework for Nutrition Reaching the Global Targets for Stunting, Anemia, Breastfeeding, and Wasting. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alderman H, Headey D. The timing of growth faltering has important implications for observational analyses of the underlying determinants of nutrition outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0195904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Guideline Alliance UK . London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2017. Faltering growth – recognition and management. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlpine J, Nielsen DK, Lee J, et al. Growth faltering: the new and the old. Clin Pediatr. 2019;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aneja S, Kumar P, Choudhary TS, et al. Growth faltering in early infancy: highlights from a two-day scientific consultation. BMC Proc. 2020;14:12. doi: 10.1186/s12919-020-00195-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Onis M, WHO MULTICENTRE GROWTH REFERENCE STUDY GROUP WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victora CG, de Onis M, Hallal PC, et al. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e473–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayatissa R, Perera A, Alwis N. National Nutrition and Micronutrient Survey in Sri Lanka: 2022. Sri Lanka: Department of Nutrition, Medical Research Institute, Minsitry of Health Sri Lanka; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sithamparapillai K, Samaranayake D, Wickramasinghe VP. Timing and pattern of growth faltering in children up-to 18 months of age and the associated feeding practices in an urban setting of Sri Lanka. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:190. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03265-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keats EC, Das JK, Salam RA, et al. Effective interventions to address maternal and child malnutrition: an update of the evidence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:367–84. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prado EL, Yakes Jimenez E, Vosti S, et al. Path analyses of risk factors for linear growth faltering in four prospective cohorts of young children in Ghana, Malawi and Burkina Faso. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001155. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Kim R, Vollmer S, et al. Factors Associated With Child Stunting, Wasting, and Underweight in 35 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203386. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomori C, O’Connor DL, Ververs M, et al. Critical research gaps in treating growth faltering in infants under 6 months: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024;4:e0001860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Silva N, Wijerathna K, Kahatapitiya S, et al. Factors associated with growth faltering in Sri Lankan infants: A case-control study in selected child welfare clinics in Sri Lanka. J Postgrad Inst Med. 2015;2:19. doi: 10.4038/jpgim.8074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwendler T, Jayawickrama H, Rowel D, et al. Maternal Care Practices in Sri Lanka During Infant and Young Child Feeding Episodes – Findings From Ethnographic Fieldwork. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;6:601. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac060.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Family Health Bureau and Health Education Bureau, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. Right food at the right time to make my baby healthy and bright 2022

- 20.Halimatunnisa M, Indarwati R, Ubudiyah M, et al. Family Determinants of Stunting in Indonesia: A Systematic Review. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil [Internet] 2020 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348805833 Available. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. Annual Report 2020 [internet] 2020 https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MMg4GR0A8hh0Y9wxFbVoKm-XvslRTFMy/view Available.

- 22.Villar J, Giuliani F, Bhutta ZA, et al. Postnatal growth standards for preterm infants: the Preterm Postnatal Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH-21(st) Project. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e681–91. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olbertz DM, Mumm R, Wittwer-Backofen U, et al. Identification of growth patterns of preterm and small-for-gestational age children from birth to 4 years - do they catch up? J Perinat Med. 2019;47:448–54. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2018-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka Census of population and housing 2001. 2001

- 25.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Van den Broeck J, et al. Measurement and Standardization Protocols for Anthropometry Used in the Construction of a New International Growth Reference. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25:S27–36. doi: 10.1177/15648265040251S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka. Statistics. https://fhb.health.gov.lk/statistics/ Available.

- 27.World Health Organization A healthy lifestyle - WHO recommendations. 2010. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations Available.

- 28.Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition (MOH) Sri Lanka Demographic and Health Survey 2006-07. Colombo, Sri Lanka: DCS and MOH; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.STATA (Version 12) 2011. [29-Apr-2024]. https://www.stata.com/stata12/ Available. Accessed.

- 30.IBM-SPSS (version 20.0) 2018. [29-Apr-2024]. https://www.ibm.com/us-en Available. Accessed.

- 31.World Health Organization Child growth standards. [29-Apr-2024]. https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards Available. Accessed.

- 32.World Health Organization WHO AnthroPlus software. 2007. https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/application-tools Available.