Abstract

Background

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent gynecological endocrine condition and a systemic inflammatory disease associated to improper lipid metabolism and increased cardiovascular risk. The Cardiometabolic Index (CMI) is a novel indicator representing visceral adipose tissue distribution and metabolic dysfunction, integrating lipid metabolism indicators and the waist-to-height ratio. While anomalies in lipid metabolism are often associated with (BMI) Body Mass Index, literature consistently shows a negative link between endometriosis and female BMI, and some studies have found that endometriosis is one of the few reproductive diseases not persistently positively correlated with obesity. Given the limitations of BMI, a comprehensive index like CMI is crucial for exploring the incidence of endometriosis. Currently, research on the correlation between CMI and endometriosis is lacking, prompting this study to investigate this association.

Objective

To investigate the association between the CMI and the risk of having endometriosis in a sample representing the entire U.S. population.

Study design

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data from four cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) spanning the years 1999 to 2006. The study included individuals aged 20 to 54 with a documented history of endometriosis and complete CMI data. Logistic regression analysis, subgroup and interaction analyses, smooth curve fitting, and restricted cubic splines (RCS) were utilized to examine the association between CMI and endometriosis.

Results

The study found that individuals with higher CMI had an increased probability of developing endometriosis. This relationship remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders such as age, ethnicity, Poverty Income Ratio (PIR), drinking, smoking, education level, and marital status. The fully adjusted model revealed a positive correlation between CMI and endometriosis (OR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04–1.40, p < 0.05). Subgroup and interaction analyses showed no significant effect modification by age, BMI, PIR, hypertension, drinking, smoking, or menarche age (all p-values for interaction > 0.05).

Conclusion

Our study shows a link between CMI and the chance of getting endometriosis.Due to the common occurrence of endometriosis and the lack of clarity surrounding their cause, more study is needed to confirm our results and find out if CMI could be used as a warning sign for endometriosis.

Keywords: endometriosis, cardiometabolic index, epidemiology, cross-sectional study, NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey)

Introduction

Endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial tissue (including glands and stroma) is found outside the uterus. It typically manifests as dysmenorrhea, menstrual irregularities, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility. Endometriosis exhibits biological characteristics similar to those of malignant tumors, such as invasiveness, implantation, and recurrence. Additionally, endometriosis provide a potential threat of long-term development of cancer (1). Over the past few years, the occurrence of endometriosis has been steadily rising, with a worldwide occurrence rate ranging from 10% to 15% (2). Studies indicate that the average diagnostic delay for endometriosis is 7-11 years (3). Delayed diagnosis, physical discomfort, hormonal therapy, and inconvenience in daily life and work significantly reduce the quality of life for endometriosis patients. Nevertheless, the underlying cause of endometriosis is still not fully understood. Recently, scientists have enhanced their comprehension of endometriosis, acknowledging it as both an estrogen-dependent gynecological endocrine condition and a systemic inflammatory disease associated to irregularities in lipid metabolism and a heightened susceptibility to cardiovascular disorders (3).

Contemporary studies suggest that anomalies in lipid metabolism are frequently associated with BMI (4). However, existing literature consistently demonstrates a negative link between the occurrence of endometriosis and female BMI (5–7). Additionally, some studies, such as a Mendelian randomization study, have found that endometriosis is one of the few reproductive diseases not persistently positively correlated with obesity (8). Therefore, employing a more comprehensive and scientific composite index to explore the incidence of endometriosis is crucial.

The cardiometabolic index (CMI) was initially introduced in 2015 (9). It is regarded as a novel measure that indicates the distribution of visceral fat and metabolic dysfunction.effectively integrating anthropometric and biochemical parameters, including TG, HDL-C, and WHtR, making individual parameters more holistic and comprehensive. Research has demonstrated that CMI can function as an innovative indicator of cardiovascular risk, allowing for the prediction of stroke outcomes in the general population (10). It is also associated with hypertension, diabetes, depression, and other diseases (11–13). Currently, there is a lack of research investigating the correlation between CMI and endometriosis. Hence, this study seeks to conduct an initial investigation into the correlation between CMI and endometriosis.

Methods

Data source and study design

We performed a cross-sectional analysis utilizing data from the NHANES database. NHANES uses a stratified, multistage probability sampling technique to track the health and nutritional well-being of adults and children in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which is under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), administers this program. It involves conducting physical examinations and household interviews (14). We employed data from four survey cycles spanning an eight-year duration (1999-2006). The NHANES study protocol received approval from the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and all participants granted signed informed consent.

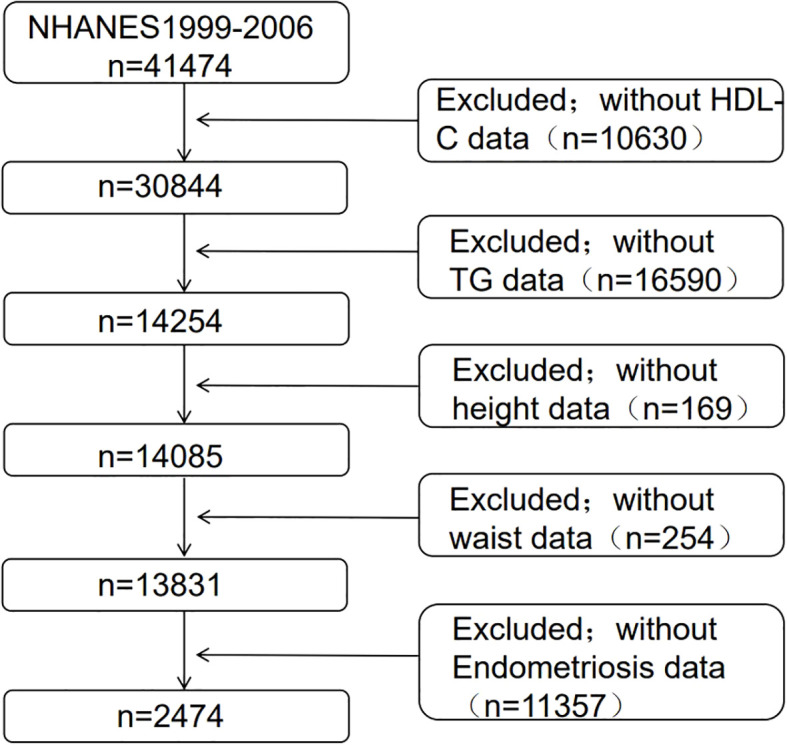

This study included 41,474 participants. We selected female participants aged 20-54 years, adhering strictly to exclusion criteria: (1) lack of interview data regarding endometriosis (n=11,357), and (2) incomplete data on TG (n=16,590), HDL-C (n=10,630), waist circumference (n=254), and height (n=169). In our final analysis, a total of 2,474 eligible participants were included. Among them, 182 persons were diagnosed with endometriosis by a doctor, while 2,292 participants did not have this diagnosis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population grouped by endometriosis.

Cardiometabolic index

The CMI is a novel indicator derived from a combination of lipid and obesity-related parameters. It is calculated based on anthropometric data and laboratory evidence. Blood samples are usually obtained at survey trucks or specific sampling locations, where measures of TG and HDL-C are taken. The measurement of TG is restricted to specimens obtained from people who have undergone a minimum fasting period of 9 hours prior to venipuncture. This requirement guarantees the preservation and stability of the stored samples. The samples undergo laboratory processing and are submitted to thorough testing following a standardized sampling approach to guarantee the quality and comparability of the data. Trained health technicians use mobile screening equipment to measure the height and waist circumference of participants. In our study, CMI is regarded as an independent variable. The formula for calculating CMI is as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Endometriosis

During the reproductive health examination conducted at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC), individuals between the ages of 20 and 54 were privately interviewed to determine if a doctor or other healthcare provider had previously diagnosed them with endometriosis. Endometriosis is a medical disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue, which is identical to the lining of the uterus, growing outside the uterus, specifically on the ovaries or fallopian tubes. Based on this information, we generated a binary variable to indicate if there was a history of endometriosis diagnosis (yes or no). The outcome variable in our study is endometriosis.

Covariates

In our analysis, we additionally included factors that could potentially affect the relationship between CMI and endometriosis. The selection of these covariates was based on pertinent literature about the exposure and outcome variables (15–17). The variables considered in this study are age, ethnicity (specifically Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other Race), education level (categorized as less than high school, high school, and college or higher), and the ratio of family income to poverty (PIR). PIR is determined by dividing the total family income by the official poverty threshold and is further classified into low (<1.3), intermediate (≥1.3 and <3.0), and high (≥3.0) groups. Other variables consist of smoking status (current smoker and non-smoker), alcohol consumption (defined as an average daily intake exceeding healthy limits, specifically more than one drink per day for women) (18), marital status (married/living with partner, separated/divorced/widowed, and never married), and whether participants had undergone a hysterectomy.

Statistical analysis

In order to guarantee that the survey results accurately reflect the entire nation, the analysis took into consideration sampling weights and the intricate sample structure to adjust for the overrepresentation of specific population groupings. Categorical variables were represented as percentages, whereas continuous variables were presented as the mean plus or minus the standard deviation (SD). Multiple imputation techniques were employed to address the absence of covariate data (hysterectomy missing data: 1300, alcohol consumption missing data: 874, smoking missing data: 1519, marital status missing data: 72, education missing data: 2, and PIR missing data: 160). We employed logistic regression analysis models to investigate the correlation between CMI and endometriosis, and evaluated the connection between the four constituents of CMI (TG, HDL-C, waist circumference, and height) and endometriosis. In the models, CMI, TG, HDL-C, waist circumference, and height were treated as continuous variables.Model 1 did not take into account any covariates. Model 2 incorporated age, ethnicity, and PIR as covariates. Model 3 went a step further and included age, ethnicity, PIR, alcohol consumption, smoking, education level, marital status, and hysterectomy as covariates. Furthermore, the researchers did subgroup analyses to examine the relationship between CMI and endometriosis.These analyses involved categorizing the participants based on several characteristics such as age, BMI, PIR, hypertension, alcohol use, smoking, and age at first menstruation (menarche). These stratification criteria were selected as potential effect modifiers. Interaction terms were included in the model to assess the variability of the relationship between CMI and endometriosis across different subgroups.In order to examine the possible linear or nonlinear relationship between CMI and endometriosis, we utilized smooth curve fitting and limited cubic spline (RCS) analysis.The data analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.3 (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) and Empower software (www.empowerstats.com; X&Y solutions, Inc., Boston, MA). The threshold for statistical significance was established at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

An analysis of descriptive statistics was performed on a sample of 2474 participants in order to compare the sociodemographic and laboratory data features of persons with and without endometriosis( Table 1 ). No statistically significant differences were observed in BMI, HDL-C, height, smoking, and drinking habits between participants with endometriosis and those without the condition (p > 0.05). Individuals diagnosed with endometriosis exhibited several distinguishing characteristics compared to those without endometriosis. On average, they were older, experienced menarche at an earlier age, had higher levels of TG, possessed a larger waist circumference, were more likely to be Non-Hispanic White, had attained higher levels of education (high school and beyond), had a relatively higher PIR, were married or cohabiting with a partner, had higher blood pressure, and a greater proportion of them had elevated CMI. Furthermore, the percentage of oophorectomy and hysterectomy was greater in the group with the disease compared to the group without the condition (p < 0.05).Additionally, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the sample, the characteristics of excluded and included female samples were compared ( Supplementary Table S1 ).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of study participants from NHANES 1999–2006.

| characteristics | Total | Endometriosis | P for trand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | |||

| Sample size | 2274 | 182 | 2292 | |

| Age (years) | 37.17 ± 9.95 | 40.37 ± 8.22 | 36.82 ± 10.06 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.03 ± 7.09 | 28.56 ± 6.66 | 27.98 ± 7.14 | 0.2249 |

| Menarche age (years) | 12.65 ± 1.66 | 12.42 ± 1.68 | 12.68 ± 1.66 | 0.0245 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.38 ± 1.19 | 1.84 ± 2.48 | 1.33 ± 0.93 | <0.0001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.47 ± 0.41 | 1.44 ± 0.42 | 1.47 ± 0.40 | 0.2839 |

| waist circumference (cm) | 91.99 ± 16.00 | 94.06 ± 15.36 | 91.76 ± 16.05 | 0.0338 |

| height (cm) | 163.46 ± 6.63 | 163.77 ± 6.07 | 163.43 ± 6.69 | 0.4498 |

| Ethnicity,% | <0.0001 | |||

| Mexican American | 7.69 | 1.48 | 8.37 | |

| Other Hispanic | 5.81 | 1.78 | 6.25 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.83 | 84.70 | 67.12 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.42 | 8.36 | 12.85 | |

| Other Race | 5.25 | 3.67 | 5.42 | |

| Education level,% | 0.0057 | |||

| Less than high school | 15.98 | 10.16 | 16.61 | |

| High school | 23.24 | 29.58 | 22.55 | |

| More than high school | 60.78 | 60.26 | 60.83 | |

| PIR,% | 0.0149 | |||

| Low | 21.58 | 20.57 | 21.68 | |

| Intermediate | 27.12 | 20.08 | 27.89 | |

| High | 51.30 | 59.35 | 50.43 | |

| marital status,% | 0.0002 | |||

| Married/living with partner | 66.60 | 75.19 | 65.67 | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 15.35 | 16.32 | 15.24 | |

| Never married | 18.06 | 8.49 | 19.09 | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| systolic | 113.98 ± 14.34 | 117.34 ± 15.72 | 113.62 ± 14.14 | 0.0001 |

| diastolic | 69.82 ± 10.05 | 72.44 ± 10.40 | 69.54 ± 9.96 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking,% | 0.5840 | |||

| Current-smoker | 52.84 | 54.50 | 52.65 | |

| Non-smoker | 47.16 | 45.50 | 47.35 | |

| Drinking,% | 0.2504 | |||

| Yes | 61.71 | 58.30 | 62.08 | |

| No | 38.29 | 41.70 | 37.92 | |

| Oophorectomy (at least one ovary), % | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 10.00 | 40.28 | 6.68 | |

| No | 90.00 | 59.72 | 93.27 | |

| hysterectomy, % | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 19.7 | 48.38 | 16.57 | |

| No | 80.3 | 51.62 | 83.43 | |

| CMI | 0.65 ± 0.86 | 0.95 ± 1.77 | 0.62 ± 0.69 | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as (%) or Mean ± SD.

BMI, body mass index; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PIR, Poverty income ratio.

Association between CMI and endometriosis

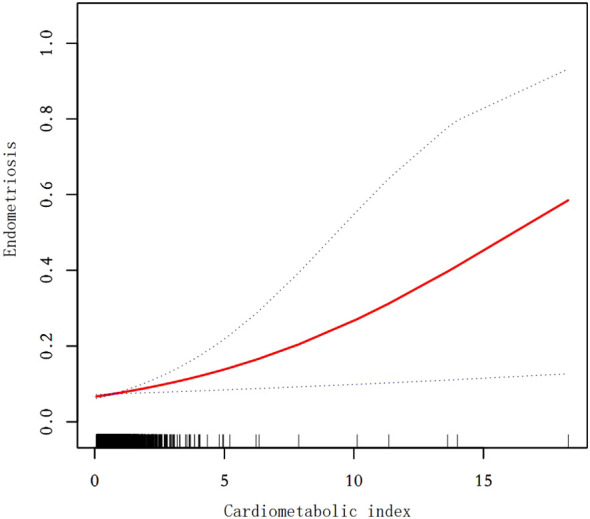

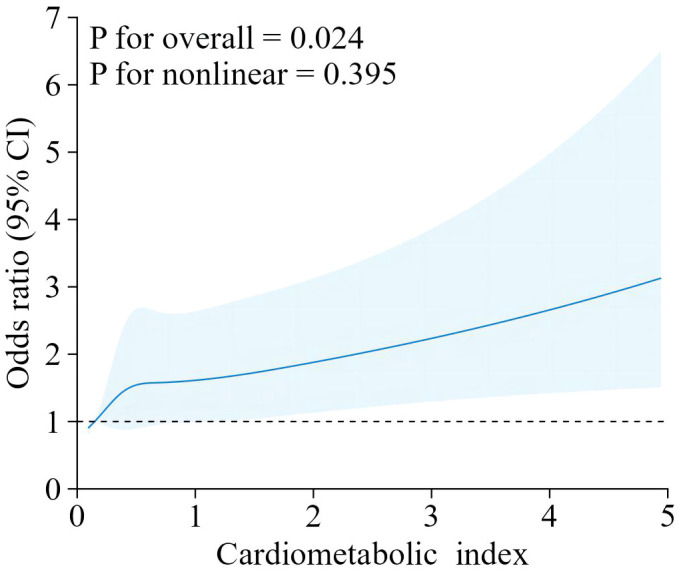

Our findings suggest that there is a positive correlation between CMI and endometriosis ( Table 2 ). In the model that accounted for all relevant factors, the correlation between CMI and endometriosis remained consistent and positive (OR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04–1.40, p < 0.05). This means that for every unit increase in CMI, there was an 21% higher likelihood of experiencing endometriosis. Since CMI is derived from four parameters, we performed a logistic regression analysis to further investigate TG, HDL-C, waist circumference, and height. The findings indicated a positive correlation between TG and the occurrence of endometriosis. In the model that accounted for all relevant factors, the correlation between TG and endometriosis remained consistent and positive (OR = 1.18; 95% CI, 1.05–1.32, p < 0.05). Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant association found between HDL-C, waist circumference, and height (p > 0.05). Furthermore, the findings from the smoothed fitting curve confirmed the positive correlation between CMI and endometriosis ( Figure 2 ). We also employed restricted cubic splines in the regression model to analyze the correlation between CMI and endometriosis. Despite the absence of a nonlinear relationship (nonlinearity P = 0.395), a significant positive association between CMI and endometriosis was observed (overall P < 0.05) ( Figure 3 ).

Table 2.

Associations between cardiometabolic index and endometriosis.

| OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| CMI | 1.14 (1.01,1.29) | 1.17 (1.03,1,32) | 1.21 (1.04,1.40) |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.13 (1.02,1.24) | 1.15 (1.04,1.28) | 1.18 (1.05,1.32) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.95 (0.66,1.37) | 0.87 (0.60,1.27) | 0.91 (0.62,1.35) |

| waist circumference (cm) | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 1.01 (1.00,1.02) | 1.01 (1.00,1.02) |

| height (cm) | 1.02 (1.00,1.04) | 0.99 (0.96,1.01) | 0.98 (0.96,1.01) |

Model 1: no covariates were adjusted.

Model 2: Adjusted for Age, Ethnicity,PIR.

Model3: Adjusted for Age, Ethnicity, PIR, drinking, smoking, Education level, marital status, hysterectomy.

Figure 2.

Smooth curve fit between cardiometabolic index and endometriosis. The solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% confidence interval from the fit. After adjusting for age,ethnicity,PIR,drinking,smoking,education level,marital status,hysterectomy, the relationship between cardiometabolic index and endometriosis was analyzed by smooth curve fitting.

Figure 3.

The RCS curve of the association between cardiometabolic index and endometriosis among all the study participants.RCS regression was Adjusted for age, ethnicity, PIR, drinking, smoking, education level, marital status,hysterectomy.

Subgroup analyses

We conducted subgroup analyses to evaluate the consistency of the relationship between CMI and endometriosis in different demographic groups. To assess any potential variations in this relationship, we included an interaction term to test for heterogeneity of associations across subgroups ( Table 3 ). The results revealed that there were no statistically significant interaction-related p-values, indicating that there was no evidence of effect modification by the examined factors (age, BMI, PIR, hypertension, drinking, smoking, and age of menarche) (all interaction p-values > 0.05). However, this does not imply that the relationship between CMI and endometriosis was unaffected by these factors, as confounding rather than effect modification may explain the consistent associations observed across subgroups. The correlation between CMI and endometriosis remained statistically similar across various subgroups, suggesting its relevance in diverse population settings.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the association between cardiometabolic index and endometriosis.

| Subgroup | OR (95% CI) | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.767 | |

| <35 | 1.29 (0.76,2.17) | |

| ≥35 | 1.18 (1.03,1.34) | |

| BMI | ||

| <25 | 1.79 (1.01,3.16) | 0.1056 |

| 25-29.9 | 1.16 (0.78,1.73) | |

| ≥30 | 1.03 (0.84,1.27) | |

| PIR,% | 0.4944 | |

| Low | 1.26 (1.02,1.56) | |

| Intermediate | 1.01 (0.70,1.47) | |

| High | 1.12 (0.91,1.38) | |

| Hypertension | 0.9395 | |

| Yes | 1.17 (0.74,1.85) | |

| No | 1.19 (1.03,1.37) | |

| Drinking | 0.9510 | |

| Yes | 1.17 (1.02,1.31) | |

| No | 1.16 (0.88,1.53) | |

| Smoking | 0.7106 | |

| Yes | 1.15 (1.00,1.32) | |

| No | 1.23 (0.89,1.69) | |

| Menarche age (years) | 0.4988 | |

| <13 | 1.12 (0.94,1.34) | |

| ≥13 | 1.23 (1.01,1.49) | |

Discussion

In our cross-sectional study comprising 2474 participants, we identified a positive link between CMI and endometriosis. Specifically, individuals with elevated CMI levels had a higher likelihood of being diagnosed with endometriosis. This association remained largely unaffected by potential confounding factors such as age, Ethnicity, PIR, drinking, smoking, Education level, marital status and hysterectomy. Even after accounting for several factors that could influence the results, the fact that these connections remain independent highlights the strength and reliability of the observed link.

Moreover, prior research has shown that lipid profiles associated to atherosclerosis can be detected in both the plasma and peritoneal fluid (PF) of women with endometriosis (19), suggesting plasma component exudation during PF formation (20). This finding provides evidence for the concept that women with endometriosis may also experience a higher occurrence of dyslipidemia. In 2010, Melo et al. conducted a case-control study to assess lipid metabolism-related markers in the blood of patients with endometriosis and normal women who had not undergone hormone therapy for a minimum of three months (21). For the first time, they found elevated TG in the serum of endometriosis patients. For this investigation, we employed CMI as a composite indicator. To ensure its specificity, we conducted a logistic regression analysis on TG, HDL-C, waist circumference, and height. The results indicated a similar association between CMI and endometriosis compared to the correlation between TG and endometriosis. However, the specific mechanism underlying the connection between CMI and endometriosis remains unclear. There are three possible explanations supporting our results. First, it may be related to chronic inflammation. Previous studies have well-documented the correlation mechanisms between obesity and inflammation (22). Additionally, lipid metabolism in adipose tissue remains dysregulated during inflammation, characterized by massive infiltration of pro-inflammatory cells and high cytokine concentrations (23). The NF-κB signaling system is essential in the development of lipid metabolic problems that occur with obesity (24). Recent research indicates that in the inflammatory conditions associated to endometriosis, there are notable alterations in many cytokines at both the serum and local levels. These changes are particularly evident in IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β, along with anomalies in the innate immune system,While numerous signaling pathways are believed to contribute to the inflammatory process associated with endometriosis, only NF-κB has been conclusively demonstrated to be implicated (25). Thus, it is postulated that the correlation between CMI and endometriosis may be associated to the NF-κB signaling pathway. Elevated CMI levels may indicate a persistent inflammatory condition within the body and can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, potentially resulting in the proliferation of endometrial tissue outside the uterus and the development of lesions known as endometriosis. Additionally, it could be associated with atypical hormone levels. Typically, overweight individuals who are capable of having children have a significant amount of fatty tissue, which has a crucial function in the body’s steroid metabolism. Elevated aromatase activity in adipose tissue results in heightened conversion of androgens into estrogens.Therefore, obesity is closely associated with elevated estrogen levels. This elevation in estrogen levels may disrupt the balance of the endocrine system (26). At the same time, the occurrence of endometriosis involves a series of biological processes, one of which is the growth of ectopic endometrial implants (27). This process is estradiol-dependent, an estrogen steroid hormone produced not only in the ovaries but also locally, including in endometrial lesions through steroidogenic enzymes such as aromatase (28, 29). Estradiol stimulation leads to the production of prostaglandins, forming a feed-forward mechanism. Ectopic endometrial tissue overexpresses estrogen receptor β (ER-β), which suppresses estrogen receptor α (ER-α), reducing the induction of ER-α-mediated prostaglandin receptors. Ultimately, the overexpression of ER-β promotes cell survival and maintains the persistence of inflammation (30, 31). Therefore, it is speculated that elevated CMI may affect estrogen secretion, which may in turn influence the growth and migration of endometrial tissue, leading to the occurrence of endometriosis. Third, it could be associated with atypical vascular functionality. The development of adipose tissue involves a diverse range of cell types, such as adipocytes, adipose stromal cells (ASCs), endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells (32). The presence of diverse cell populations with different characteristics influences the production of various growth factors and cytokines, which have the ability to separately or together control the process of angiogenesis (33). Adipocytes in the process of growth create numerous substances that promote the formation of new blood vessels, such as leptin, VEGF, FGF-2, HGF, IGF, TNF-α, TGF-β, placental growth factor (PlGF), VEGF-C, resistin, tissue factor (TF), neuropeptide Y (NPY), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor, and Angs (34). Pre-adipocytes and adipocytes also synthesize lipids, including monobutyrin, which promote angiogenesis in adipose tissue (35, 36). The cause of endometriotic lesions is still debated, but it is clear that the growth and survival of these lesions heavily rely on the development of new blood vessels. These blood vessels provide oxygen and necessary nutrients for the lesions to thrive (37–40). Endometriosis lesions are typically characterized by extensive angiogenesis (41). Thus, there is speculation that a high CMI may indicate the development of compact blood vessels. These irregularities can impact the blood flow and circulation in the endometrium, therefore affecting the development of endometriosis.

The present investigation possesses numerous advantages. The study initially included nationally representative NHANES data, which allowed for the inclusion of a broad sample of American adults from various age groups. However, after applying specific exclusion criteria for this analysis, the resulting study population may no longer fully reflect the national population. Nonetheless, this approach resulted in a substantial sample size and enabled us to account for several potential confounding factors, which greatly improves the reliability of our findings. Our statistical models extensively analyzed the correlation between individual CMI and heightened endometriosis levels. In addition, we created smooth curve fits and RCS to represent the link between the two variables, allowing us to examine the correlation from many angles and enhance the robustness of our findings.

Nevertheless, our study does possess certain constraints. Firstly, due to its cross-sectional nature, establishing a causal relationship between CMI and endometriosis is difficult. Furthermore, even after accounting for potential confounding variables, it is still possible that there are additional unmeasured confounding effects that have not been fully accounted for. Furthermore, many data in our study, such as smoking and drinking habits, are based on self-reporting, which could potentially create bias. Furthermore, our study relies on data collected from American adults, which raises doubts about the applicability of our findings to individuals from different countries and areas. Hence, it is imperative to conduct extensive prospective cohort studies to validate our findings.

The clinical significance of the observed association between CMI and endometriosis is noteworthy, particularly in terms of early identification, diagnosis, and intervention for patients with elevated CMI. This finding suggests that women with higher CMI, who are already at risk for metabolic and cardiovascular issues, may require closer monitoring for endometriosis. Furthermore, it raises the possibility of incorporating CMI as a marker in clinical guidelines for managing endometriosis patients. In particular, for those already diagnosed with endometriosis, heightened attention to cardiovascular health may be warranted, as they could be more susceptible to developing heart disease or other metabolic complications.Additionally, by integrating knowledge of the increased cardiovascular risk associated with higher CMI, clinicians could adopt a more comprehensive approach that includes lifestyle modifications, pharmacological interventions, and early preventive measures aimed at reducing the likelihood of cardiovascular disease. Such personalized treatment strategies could help mitigate long-term health risks, offering targeted care for women who are affected by both conditions.

Conclusion

To summarize, our research shows an association between CMI and the likelihood of getting endometriosis. Given the high incidence of endometriosis and the unclear pathogenesis, further research is necessary to verify our findings and determine whether CMI could serve as a predictive indicator for endometriosis.

Glossary

- CMI

Cardiometabolic Index

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- MEC

Mobile Examination Center

- TG

Triglycerides

- HDL-C

High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

- WHtR

Waist-to-Height Ratio

- PIR

Poverty Income Ratio

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- OR

Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

- SD

Standard Deviation

- RCS

Restricted Cubic Splines

- ER-β

Estrogen Receptor Beta

- ER-α

Estrogen Receptor Alpha

- NF-κB

Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- FGF-2

Fibroblast Growth Factor 2

- HGF

Hepatocyte Growth Factor

- IGF

Insulin-like Growth Factor

- TNF-α

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha

- TGF-β

Transforming Growth Factor Beta

- PlGF

Placental Growth Factor

- TF

Tissue Factor

- NPY

Neuropeptide Y

- EGF

Epidermal Growth Factor

- ASCs

Adipose Stromal Cells

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82004411), National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Wang Xiaoyun National Famous Elderly Traditional Chinese Medicine Experts Inheritance Workshop Construction Project (No. [2016]42), Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program Project (No. 2017B030314166), Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine Sunrise Talent Scientific Research Special Grant (No. ZY2022KY02), Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine Project Lingnan Gynecology School Inheritance Workshop Construction Project (No. [2013]233), and Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine 2022 Traditional Chinese Medicine Classics Inheritance Special Project (No. [2022]173 of the University Office).

Data availability statement

The data were derived from sources in the public domain: NHANES https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx.

Ethics statement

In 2003, the NHANES Institutional Review Board (IRB) changed its name to the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB). In 2018, the name was changed from NCHS Research Ethics Review Board to NCHS Ethics Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. XH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. XW: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2024.1450965/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Holt VL, Weiss NS. Recommendations for the design of epidemiologic studies of endometriosis. Epidemiology. (2000) 11:654–9. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200011000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1244–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. (2021) 397:839–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00389-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cirulli ET, Guo L, Leon Swisher C, Shah N, Huang L, Napier LA, et al. Profound perturbation of the metabolome in obesity is associated with health risk. Cell Metab. (2019) 29(2):488–500.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferrero S, Anserini P, Remorgida V, Ragni N. Body mass index in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2005) 121:94–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hediger ML, Hartnett HJ, Louis GMB. Association of endometriosis with body size and figure. Fertil Steril. (2005) 84:1366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shah DK, Correia KF, Vitonis AF, Missmer SA. Body size and endometriosis: results from 20 years of follow-up within the Nurses' Health Study II prospective cohort. Hum Reprod. (2013) 28:1783–92. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Venkatesh SS, Ferreira T, Benonisdottir S, Rahmioglu N, Becker CM, Granne I, et al. Obesity and risk of female reproductive conditions: A Mendelian randomisation study. PLoS Med. (2022) 19:e1003679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wakabayashi I, Daimon T. The "cardiometabolic index" as a new marker determined by adiposity and blood lipids for discrimination of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chim Acta. (2015) 438:274–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang H, Chen Y, Guo X, Chang Y, Sun Y. Usefulness of cardiometabolic index for the estimation of ischemic stroke risk among general population in rural China. Postgrad Med. (2017) 129:834–41. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1375714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong T, Lin W, Zhou Q, Yang Y, Liu X, Chen J, et al. Association of adiposity indicators with cardiometabolic multimorbidity risk in hypertensive patients: a large cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2024) 15:1302296. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1302296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zha F, Cao C, Hong M, Hou H, Zhang Q, Tang B, et al. The nonlinear correlation between the cardiometabolic index and the risk of diabetes: A retrospective Japanese cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1120277. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1120277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou X, Tao X-L, Zhang L, Yang Q-K, Li Z-J, Dai L, et al. Association between cardiometabolic index and depression: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2014. J Affect Disord. (2024) 351:939–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National health and nutrition examination survey: plan and operations, 1999-2010. Vital Health Stat 1. (2013) (56):1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheng L, Wu Q, Wang S. Cardiometabolic index is associated with increased depression: A population-based study. J Affect Disord. (2024) 348:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.12.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall MS, Talge NM, Upson K. Urinary cadmium and endometriosis prevalence in a US nationally representative sample: results from NHANES 1999-2006. Hum Reprod. (2023) 38:1835–42. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dead117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang S, Farland LV, Gaskins AJ, Mortazavi J, Wang Y-X, Tamimi RM, et al. Association of laparoscopically-confirmed endometriosis with long COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2023) 228(6):714.e1–714.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Y-B, Chen C, Pan X-F, Guo J, Li Y, Franco OH, et al. Associations of healthy lifestyle and socioeconomic status with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease: two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. (2021) 373:n604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson LW, Schisterman EF, Dey-Rao R, Browne R, Armstrong D. Oxidative stress and endometriosis. Hum Reprod. (2005) 20:2014–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrison D, Griendling KK, Landmesser U, Hornig B, Drexler H. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. (2003) 91(3A):7A–11A. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)03144-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melo AS, Rosa-e-Silva JC, Rosa-e-Silva A, Poli-Neto OB, Ferriani RA, Vieira CS. Unfavorable lipid profile in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. (2010) 93:2433–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza'ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. (2017) 13:851–63. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xu S, Lu F, Gao J, Yuan Y. Inflammation-mediated metabolic regulation in adipose tissue. Obes Rev. (2024) 25:e13724. doi: 10.1111/obr.13724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu W, Oteiza PI. Proanthocyanidins at the gastrointestinal tract: mechanisms involved in their capacity to mitigate obesity-associated metabolic disorders. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2024) 64:220–40. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2105802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dymanowska-Dyjak I, Terpiłowska B, Morawska-Michalska I, Michalski A, Polak G, Terpiłowski M, et al. Immune dysregulation in endometriomas: implications for inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25(9):4802. doi: 10.3390/ijms25094802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zheng L, Yang L, Guo Z, Yao N, Zhang S, Pu P. Obesity and its impact on female reproductive health: unraveling the connections. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1326546. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1326546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. (2010) 362:2389–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1000274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amsterdam LL, Gentry W, Jobanputra S, Wolf M, Rubin SD, Bulun SE. Anastrazole and oral contraceptives: a novel treatment for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. (2005) 84:300–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bulun SE, Imir G, Utsunomiya H, Thung S, Gurates B, Tamura M, et al. Aromatase in endometriosis and uterine leiomyomata. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. (2005) 95:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, et al. Endometriosis. Endocr Rev. (2019) 40:1048–79. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Monsivais D, Dyson MT, Yin P, Coon JS, Navarro A, Feng G, et al. ERβ- and prostaglandin E2-regulated pathways integrate cell proliferation via Ras-like and estrogen-regulated growth inhibitor in endometriosis. Mol Endocrinol. (2014) 28:1304–15. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld-Clauss S, Temm-Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, et al. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. (2004) 109:1292–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cao Y. Opinion: emerging mechanisms of tumour lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. (2005) 5:735–43. doi: 10.1038/nrc1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li J, Yu X, Pan W, Unger RH. Gene expression profile of rat adipose tissue at the onset of high-fat-diet obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2002) 282:E1334–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00516.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dobson DE, Kambe A, Block E, Dion T, Lu H, Castellot JJ, et al. 1-Butyryl-glycerol: a novel angiogenesis factor secreted by differentiating adipocytes. Cell. (1990) 61:223–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90803-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilkison WO, Choy L, Spiegelman BM. Biosynthetic regulation of monobutyrin, an adipocyte-secreted lipid with angiogenic activity. J Biol Chem. (1991) 266:16886–91. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)55385-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Groothuis PG, Nap AW, Winterhager E, Grümmer R. Vascular development in endometriosis. Angiogenesis. (2005) 8:147–56. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-9005-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laschke MW, Menger MD. In vitro and in vivo approaches to study angiogenesis in the pathophysiology and therapy of endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. (2007) 13:331–42. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. May K, Becker CM. Endometriosis and angiogenesis. Minerva Ginecol. (2008) 60:245–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taylor RN, Yu J, Torres PB, Schickedanz AC, Park JK, Mueller MD, et al. Mechanistic and therapeutic implications of angiogenesis in endometriosis. Reprod Sci. (2009) 16:140–6. doi: 10.1177/1933719108324893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McLaren J. Vascular endothelial growth factor and endometriotic angiogenesis. Hum Reprod Update. (2000) 6:45–55. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data were derived from sources in the public domain: NHANES https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx.