Abstract

We have previously mapped the single-stranded DNA binding domain of large T antigen to amino acid residues 259 to 627. By using internal deletion mutants, we show that this domain most likely begins after residue 301 and that the region between residues 501 and 550 is not required. To study the function of this binding activity, a series of single-point substitutions were introduced in this domain, and the mutants were tested for their ability to support simian virus 40 (SV40) replication and to bind to single-stranded DNA. Two replication-defective mutants (429DA and 460EA) were grossly impaired in single-stranded DNA binding. These two mutants were further tested for other biochemical activities needed for viral DNA replication. They bound to origin DNA and formed double hexamers in the presence of ATP. Their ability to unwind origin DNA and a helicase substrate was severely reduced, although they still had ATPase activity. These results suggest that the single-stranded DNA binding activity is involved in DNA unwinding. The two mutants were also very defective in structural distortion of origin DNA, making it likely that single-stranded DNA binding is also required for this process. These data show that single-stranded DNA binding is needed for at least two steps during SV40 DNA replication.

Simian virus 40 (SV40) has been used extensively as a model to study eukaryotic DNA replication. The virus encodes a multifunctional protein, T antigen, which is the only viral protein required for DNA replication. All other factors are provided by the host cell (63). To initiate DNA replication, T antigen binds to the viral origin, which has two pairs of GAGGC pentanucleotides arranged in a head-to-head orientation (15, 65, 66). In the presence of ATP, T antigen assembles into a double hexamer by binding to the pentanucleotides (13, 25, 33) and causes structural changes in the flanking DNA sequences. The DNA at the early palindrome (EP) is melted and the AT-rich region is untwisted (4, 5, 12, 41, 45). Then T antigen functions as a helicase to bidirectionally unwind the DNA in the presence of replication protein A (RPA) and topoisomerase I (14, 16, 21, 76). Other cellular factors, including DNA polymerase α-primase, RFC, PCNA, and DNA polymerase δ, are also recruited to form the replication fork (36, 39, 40, 44, 67, 70, 71).

Many of the functional domains of T antigen have been well characterized. The origin DNA binding domain is located near the N-terminal end from residues 147 to 247 (1, 35, 53, 54) and by itself has the ability to interact with origin DNA (1, 26, 35). As a helicase, T antigen unwinds DNA in a 3′ to 5′ direction coupled with ATP hydrolysis (21, 60, 75). The region required for this activity maps from residues 131 to 616 (78). The ATP binding domain is located between residues 418 and 528 (7), and the ATPase domain extends from residues 418 to 616 (9, 10).

We have recently started to study T antigen's single-stranded DNA binding activity (77). The exact function of this activity is not known, but there are a number of reasons for believing that it is required for DNA unwinding. When T antigen is incubated with a synthetic DNA fork in the presence of ATP, it assembles on the fork as a hexamer and unwinds it (50, 58, 74). During this process, T antigen interacts primarily with the 3′ single strand with slight protection of the duplex DNA close to the branch point (50). On a replication bubble, T antigen binds as a double hexamer with twofold symmetry and strongly protects the same (3′) strand at each junction (58). It is proposed that during unwinding T antigen forms a double hexamer with each strand of DNA being pulled through the central channel of different hexamers (58). These observations point to an active role of single-stranded DNA binding during the unwinding process.

T antigen belongs to helicase superfamily 3, which includes helicases from small DNA and RNA viruses (22). Based on sequence alignments and secondary structure predictions, Masterson et al. (32) suggested that the C-terminal region of the helicases in this family serves as the helicase domain. This helicase domain on T antigen also shows homology and antibody cross-reaction with Escherichia coli RecA (49). In recent years, the crystal structures of several helicases from superfamilies 1, 2, and 4 have been resolved. Monomeric or dimeric helicases, such as Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA (62, 69), E. coli Rep (29), hepatitis C virus NS3 (28, 80), and UvrB (64) all contain two RecA-like domains that join to form a nucleotide binding site at their interface. Similarly, each subunit of hexameric bacteriophage T7 gene 4 helicase contains a RecA-like domain (46, 57). Domains on adjacent subunits combine to form a nucleotide binding site. These similarities suggest that the ATP binding domain of RecA is the unifying structure of all helicases (2, 81). However, it does not appear that helicases use a common mechanism of action. PcrA binds and destabilizes double-stranded DNA ahead of the fork by using its 1B and 2B domains (59, 69), whereas NS3 passively unwinds the DNA by binding to single-stranded DNA generated from thermal fluctuations at the fork (28, 43). During translocation, PcrA binds to single-stranded DNA as a monomer through the two RecA-like domains (69). For hexameric T7 gene 4 helicase, it is proposed that each subunit sequentially binds to single-stranded DNA in the central channel, as suggested by the asymmetric arrangement of the six subunits in the hexamer (57).

To probe the possible role of the single-stranded DNA binding domain of T antigen in DNA unwinding and to determine if it has other functions, we generated a series of internal deletion and single-point substitution mutants in this domain. The mutants' abilities to bind single-stranded DNA and to perform other biochemical reactions related to DNA replication were tested. The results demonstrate a strong correlation between single-stranded DNA binding and unwinding the origin and a helicase substrate. We also show a correlation with the mutants' abilities to structurally distort the origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis.

Mutations were generated as described by Loeber et al. (31). Oligonucleotides containing desired point mutations were phosphorylated and annealed to uridine-containing single-stranded pBS-SV40 (31) or pSK(−)SVTC (30). The complementary strand was synthesized by T4 polymerase and sealed by T4 ligase. The DNA was used to transform E. coli JM109 cells. The colonies were screened for correct mutations by standard dideoxy DNA sequencing.

Construction of recombinant baculoviruses.

For making internal deletion mutants, T antigen cDNAs with different internal deletions (27) (obtained from Judy Tevethia) were used as templates for PCR. DNA constructs were missing between 14 and 82 codons and contained, in their place, 3 extra non-T-antigen codons (27). An oligonucleotide with a start site at amino acid residue 246 was used as the up primer; the down primer had a stop codon after residue 708. The PCR DNAs were cut with appropriate restriction enzymes and inserted into pVL1393 baculovirus transfer vector (BD PharMingen). All clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

For making single-point-substitution-mutant T antigens, mutant pSK(−)SVTC DNA was cut with BamHI and ligated with BamHI-cleaved pVL941 DNA (BD PharMingen). The pVL1393 or pVL941 DNA with T-antigen inserts was cotransfected with BaculoGold DNA (BD PharMingen) in Sf9 insect cells according to the manufacturer's protocol. T-antigen-expressing recombinants were detected by immunofluorescence analysis and purified by plaque assays.

T-antigen purification.

Wild-type and mutant T antigens were expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells and purified by immunoaffinity chromatography with monoclonal antibody PAb101 as previously described (19). The internal deletion mutants were eluted with buffer E (20 mM triethylamine [pH 10.8], 10% glycerol) (52), and the point substitution mutants were eluted with ethylene glycol elution buffer (50% ethylene glycol, 20 mM Tris [pH 8.5], 500 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) (33). The T antigens were dialyzed against dialysis storage buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50% glycerol) and stored at −20°C.

Viral replication assay.

pBS-SV40 DNA containing a point mutation was cut with BamHI to release the SV40 genomic DNA. The DNA was then ligated at low concentrations to get circular SV40 DNA. The DNA was transfected into BSC-1 monkey kidney cells by using DEAE-dextran (34). On day 10, the cells were stained with neutral red and the sizes of the plaques were compared to those formed by the wild type.

Gel shift assays.

For single-stranded DNA binding, a 32P-end-labeled 55-mer single-stranded DNA corresponding to the bottom strand of the fork substrate (50) was used. A 112-bp origin-containing HindIII-NcoI SV40 DNA fragment from pSKori (56) was end-labeled with 32P and used in origin DNA binding reactions. The reactions were performed in replication buffer (30 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 7 mM MgCl2, 40 mM creatine phosphate, 4 mM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml). After incubation of T antigen with DNA for 30 min at 37°C, glutaraldehyde was added to a final concentration of 0.1% and the reaction mixtures were incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C. The samples were loaded on composite gels (2.5% acrylamide and 0.6% agarose) and subjected to electrophoresis at 25 mA for 3 h in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 4°C. The gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Origin DNA unwinding.

The substrate for origin DNA unwinding was a 32P-end-labeled 112-bp HindIII-to-NcoI origin-containing fragment. T antigen was incubated with the substrate in replication buffer supplemented with 50 μg of creatine phosphokinase per ml and 2.8 μg of E. coli single-stranded DNA binding protein (Pharmacia) per ml. After 1 h at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by adding EDTA to 20 mM, sodium dodecyl sulfate to 0.5%, and proteinase K to 0.2 mg/ml and the mixtures were incubated for an additional 30 min. After the samples were heated for 5 min at 65°C, they were loaded on 7% acrylamide gels and subjected to electrophoresis for 600 V · h at 4°C.

ATPase assays.

Six hundred nanograms of T antigen was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in ATPase buffer (8). After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, the mixture was spotted on polyethyleneimine-cellulose thin-layer chromatography plates and subjected to ascending chromatography in 0.75 M KH2PO4 (6). The released inorganic phosphate and ATP were quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Helicase assays.

The helicase assay was based on the method of Stahl (60). The helicase substrate was made by annealing a 32-mer primer (5′ CCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAAC 3′) to M13mp19 single-stranded DNA. The primer was extended by Klenow DNA polymerase in the presence of dCTP and [α-32P]dATP at room temperature for 20 min, followed by an additional 20-min incubation at room temperature with unlabeled dATP. The substrate was purified on a Sephadex G-50 column (Pharmacia). T antigen was incubated with the substrate in helicase buffer (60) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding sodium dodecyl sulfate to a final concentration of 0.2% and EDTA to 50 mM. The displaced primer was resolved by electrophoresis on 10% acrylamide gels for 360 V · h at 4°C. The gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography.

KMnO4 assays.

KMnO4 oxidation was used to detect the melting and untwisting of origin DNA as described by Borowiec and Hurwitz (4) and Parsons et al. (41). Four hundred to 2,000 ng of T antigen was incubated with 600 ng of origin-containing plasmid pSVOΔ1 (61) in replication buffer. After 30 min at 37°C, KMnO4 was added to a final concentration of 6 mM, followed by an additional 4-min incubation. The reaction was stopped by adding 2-mercaptoethanol to a final concentration of 1 M. The DNA was purified through a Sephadex G-50 column and subjected to primer extension assays using a 32P-end-labeled pBR322 EcoRI primer (New England Biolabs). The samples were loaded on a 7% sequencing gel, and the gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film. The melting and untwisting signals were quantitated with a PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

Single-stranded DNA binding activity of deletion mutants.

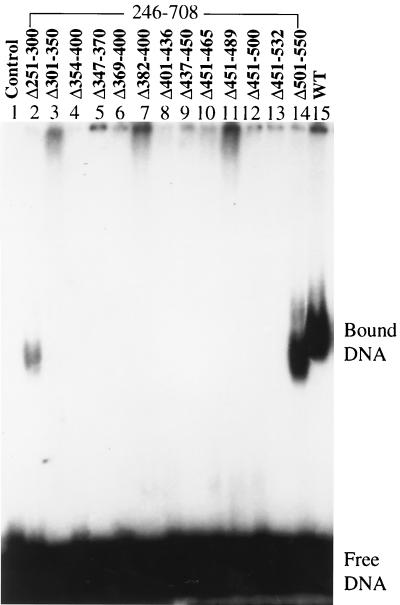

The single-stranded DNA binding domain of T antigen has been mapped to amino acid residues 259 through 627 (77). In order to more precisely map this activity, we made a series of mutants with internal deletions (between 14 and 82 amino acids) within the single-stranded DNA binding domain. All of these mutant proteins began at amino acid residue 246 and ended at residue 708, with additional deletions spanning between residues 251 and 550. Similar internal deletion mutants of T antigen were made by Kierstead and Tevethia (27) to map the p53 binding region. The mutants were expressed in recombinant baculoviruses and purified by immunoaffinity chromatography. The single-stranded DNA binding activity of these 13 mutants was tested by gel shift experiments (Fig. 1). A mutant with a deletion of residues 251 to 300 could form hexamers on single-stranded DNA (Fig. 1, lane 2), although the binding was weaker than that with wild-type T antigen. Another mutant missing amino acids 501 to 550 also formed hexamers on single-stranded DNA at a level close to that of the wild type (Fig. 1, lane 14). This indicates that regions 251 to 300 and 501 to 550 are not required for single-stranded DNA binding. Mutants with deletions of residues 301 to 350, 354 to 400, 347 to 370, 369 to 400, 382 to 400, 401 to 436, 437 to 450, 451 to 465, 451 to 489, 451 to 500, and 451 to 532 failed to form hexamers on single-stranded DNA (Fig. 1, lanes 3 to 13). This result suggests that the region between residues 301 and 500 is important for single-stranded DNA binding.

FIG. 1.

Single-stranded DNA binding assay of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens. Ten picomoles (corresponding to 800 ng of wild-type T antigen) wild-type or N-terminal deletion mutant T antigens (246 to 708) with an extra internal deletion was incubated with end-labeled single-stranded DNA for 30 min at 37°C, cross-linked with glutaraldehyde, and applied to a composite gel (0.6% agarose and 2.5% acrylamide) in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The positions of free DNA and bound DNA are shown.

Viral replication of single-point mutants.

To better characterize the function of the single-stranded DNA binding activity of T antigen, we generated mutants with single-point substitutions within the region identified above. The residues that were changed were selected on the basis of a weak sequence similarity with RPA, a single-stranded DNA binding protein. Since the residues in RPA that contact single-stranded DNA are known (3, 42), we chose nine corresponding amino acids in T antigen and mutagenized them to alanines. Mutations were first introduced into the entire virus genome (in pBS-SV40) to assess their effect on viral replication. The viral DNA was excised from the plasmid, religated into circular DNA, and transfected into BSC-1 monkey kidney cells. The ability of these mutants to form plaques was evaluated after 10 days (Table 1). Mutants 347KA and 387WA formed large plaques, just like the wild type. Mutants 349RA, 364RA, 371RA, and 377GA formed small plaques, and mutants 308KA, 429DA, and 460EA did not form any plaques under our experimental conditions. This showed that mutations of residues 308, 349, 364, 371, 377, 429, and 460 caused a defect in viral replication.

TABLE 1.

Properties of single-point mutants

| Point mutants | Plaque formation | % Wild-type activity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin DNA binding | Single-stranded DNA binding | Origin DNA unwindinga | ATPase | ||

| 308 Lys→Ala | None | 116 | 93 | 90 | 50 |

| 347 Lys→Ala | Big | NDb | ND | ND | ND |

| 349 Arg→Ala | Small | 105 | 38 | 61 | 80 |

| 364 Arg→Ala | Small | 91 | 36 | 46 | 35 |

| 371 Arg→Ala | Small | 121 | 122 | 111 | 95 |

| 377 Gly→Ala | Small | 111 | 92 | 105 | 90 |

| 387 Trp→Ala | Big | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 429 Asp→Ala | None | 88 | 11 | 9 | 75 |

| 460 Glu→Ala | None | 83 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

The reactions were performed by incubating 400 ng of T antigen with an end-labeled 112-bp origin containing DNA fragment in the presence of E. coli single-stranded DNA binding protein.

ND, not done.

Single-stranded DNA and origin DNA binding by single-point mutants.

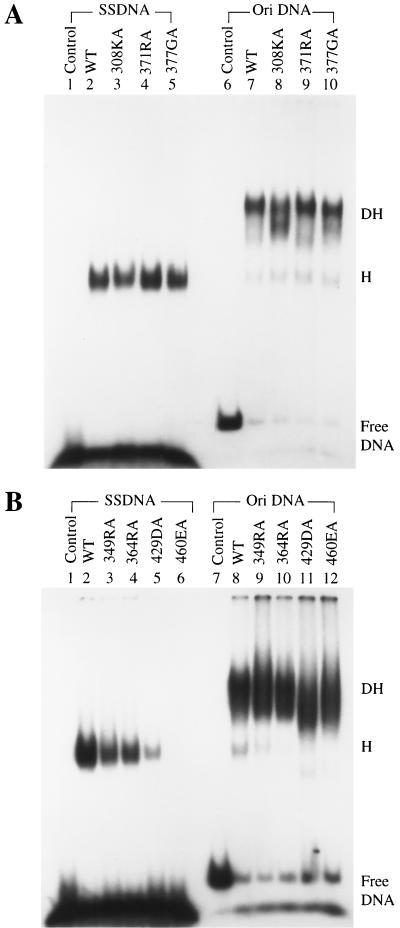

To determine whether the virus replication-defective T-antigen mutants were also defective in binding to single-stranded DNA, seven equivalent mutations were introduced in the T-antigen cDNA to generate alanine substitution mutants at residues 308, 349, 364, 371, 377, 429, and 460. T antigens were expressed from recombinant baculoviruses and purified by immunoaffinity chromatography. Their binding to single-stranded DNA and origin DNA was tested in gel shift assays (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Mutants 308KA, 371RA, and 377GA had normal single-stranded DNA binding activity (Fig. 2A, lanes 3, 4, and 5), whereas that of mutants 349RA, 364RA, and 429DA was weaker than that of the wild type (Fig. 2B, lanes 3, 4, and 5), and mutant 460EA failed to bind to any single-stranded DNA (Fig. 2B, lane 6). Although mutants 349RA, 364RA, and 429DA bound single-stranded DNA poorly, they were still able to form hexamers on the DNA, just like the wild type (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 to 5). All of these mutants had the ability to bind to origin DNA as double hexamers (Fig. 2A, lanes 8 to 10, and B, lanes 9 to 12), although 308KA and 429DA might have formed slightly smaller complexes. These results are consistent with the previous observation (77) that the single-stranded DNA and origin DNA binding domains are distinct.

FIG. 2.

Single-stranded and origin DNA binding assays of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens. Four hundred nanograms of purified wild-type and single-point-substitution mutant T antigens were tested for binding to end-labeled single-stranded DNA (SSDNA) or 112-bp origin-containing DNA (Ori DNA). (A) Binding by wild-type, 308KA, 371RA, and 377GA T antigens. (B) Binding by wild-type, 349RA, 364RA, 429DA, and 460EA T antigens. The positions of free DNA and DNA bound with T antigen in hexamers (H) and double hexamers (DH) are indicated.

Unwinding of origin DNA by point mutants.

The current helicase model shows that T-antigen hexamers encircle only one strand of DNA during unwinding (18, 58). This suggests that single-stranded DNA binding activity is needed for DNA unwinding. To investigate this possibility, mutant T antigens were examined for their ability to unwind an origin DNA fragment in the presence of E. coli single-stranded DNA binding protein as previously described (55). The results are shown in Table 1. Mutants 308KA, 371RA, and 377GA were able to unwind double-stranded DNA into single-stranded DNA. Mutants 349RA and 364RA had significantly less unwinding activity, and mutant 429DA had very little activity. Unwinding activity by mutant 460EA was undetectable. By comparing these results with those measuring single-stranded DNA binding (Fig. 2 and Table 1), it is apparent that mutants with impaired abilities to bind single-stranded DNA were also defective in origin DNA unwinding.

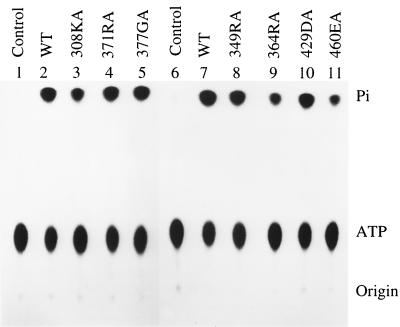

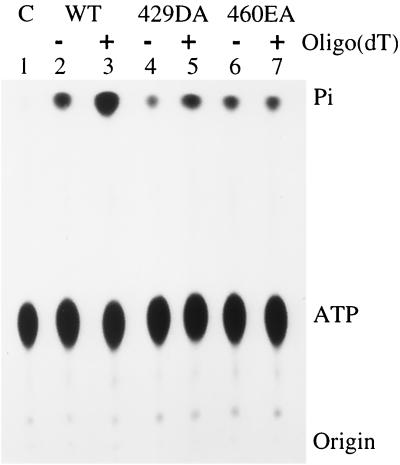

ATPase activity of point mutants.

For T antigen to unwind double-stranded DNA, it needs to hydrolyze ATP in order to provide the energy needed to separate the two strands. There are two possible reasons why mutants 349RA, 364RA, 429DA, and 460EA are defective in DNA unwinding. One is due to their impairment in single-stranded DNA binding; the other is as a result of an inability to hydrolyze ATP. To distinguish between them, the mutants were tested for their ATPase activity. It is clear that all mutants were able to hydrolyze ATP and release inorganic phosphate (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Since the level of ATPase activity did not correlate with unwinding, it is unlikely that the mutants' defects in unwinding were due to altered ATPase activity.

FIG. 3.

ATPase assay of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens. Six hundred nanograms of wild-type or mutant T antigens was incubated with 0.3 nmol of [γ-32P]ATP for 1 h at room temperature. The released free inorganic phosphate (Pi) was separated from the ATP substrate by ascending thin-layer chromatography.

Single-stranded DNA binding activity of 429DA and 460EA.

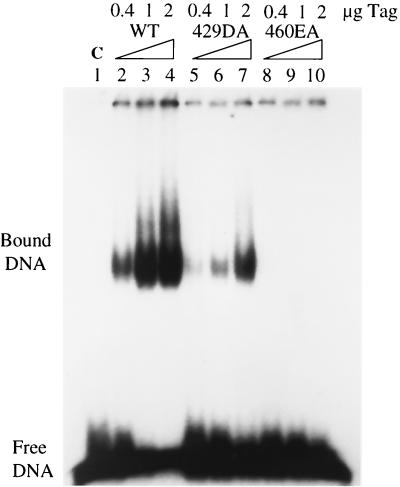

Since mutants 429DA and 460EA were very defective in single-stranded DNA binding and origin unwinding and still had ATPase activity, we decided to use these two mutants to study the function of single-stranded DNA binding. The mutant proteins appeared to be stable on the basis of our ability to purify normal amounts from infected insect cells. We first studied their binding to single-stranded DNA in more detail. The single-stranded DNA binding assays described earlier were performed at low T-antigen concentrations, and we first asked if this defect could be compensated by high protein concentrations. Higher amounts of mutant 429DA T antigen did partially restore binding to single-stranded DNA (Fig. 4, lanes 5, 6, and 7), but binding was still weaker than that of the wild type (Fig. 4, lanes 2, 3, and 4). However, mutant 460EA showed no binding to single-stranded DNA at all T-antigen concentrations tested (Fig. 4, lanes 8, 9, and 10), demonstrating that this mutant had an intrinsic defect in its interaction with single-stranded DNA.

FIG. 4.

Single-stranded DNA binding assay of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens (Tag). Increasing amounts of wild-type, 429DA, and 460EA T antigens were tested for their ability to bind to single-stranded DNA. The positions of free DNA and bound DNA are shown. C, control.

ATPase activity of 429DA and 460EA in the presence of single-stranded DNA.

The ATPase activity of T antigen can be stimulated by single-stranded DNA (20, 47). If a mutant cannot bind to single-stranded DNA, one might predict that the addition of single-stranded DNA should have no effect on its ATPase activity. This was exactly what we observed with mutant 460EA. The addition of oligo(dT) did not cause an increase in ATPase activity (Fig. 5, lanes 6 and 7). In comparison, the ATPase activity of wild-type T antigen was stimulated 3.5-fold with oligo(dT), and that of mutant 429DA, which had weak binding to single-stranded DNA, was stimulated by twofold (Fig. 5, lanes 2 to 5). This confirms that mutant 429DA effectively binds some single-stranded DNA, whereas mutant 460EA is completely defective.

FIG. 5.

Effect of oligo(dT) on the ATPase activity of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens. Six hundred nanograms of T antigen was incubated with 15 nmol of [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of 40 ng of oligo(dT)32. C, control.

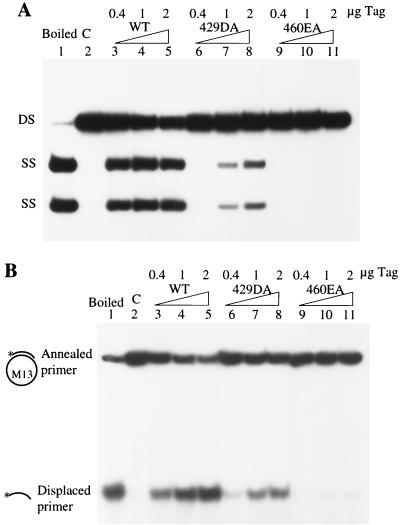

Unwinding activity of mutants 429DA and 460EA.

We next studied the effects of higher T-antigen concentrations on DNA unwinding. Mutant 429DA showed very little origin unwinding at low T-antigen concentrations, but as its concentration was increased, unwinding activity also increased (Fig. 6A, lanes 6, 7, and 8). However, mutant 460EA failed to unwind origin DNA even at high T-antigen concentrations (Fig. 6A, lanes 9, 10, and 11). Similar results were obtained with a standard helicase reaction measuring the ability to displace a primer from M13 single-stranded DNA. The helicase activity of mutant 429DA increased with increasing amounts of T antigen (Fig. 6B, lanes 6, 7, and 8), while mutant 460EA showed essentially no activity (Fig. 6B, lanes 9, 10, and 11). These results reveal a strong correlation between single-stranded DNA binding and the ability to unwind DNA.

FIG. 6.

Unwinding assays of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens (Tag). (A) Increasing amounts of wild-type, 429DA, and 460EA T antigens were tested for their ability to unwind a doubly end-labeled origin-containing DNA fragment in the presence of E. coli single-stranded DNA binding protein. The positions of the single-stranded DNAs (SS) and double-stranded DNA (DS) are indicated. (B) Increasing amounts of wild-type, 429DA, and 460EA T antigens were incubated with a helicase substrate. The positions of the annealed and displaced primers are indicated. C, control.

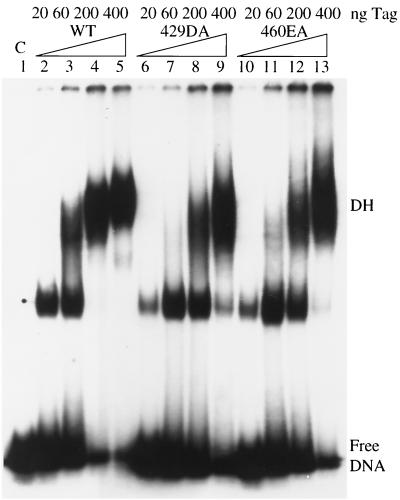

Origin DNA binding by mutants 429DA and 460EA.

We then asked if mutants 429DA and 460EA interact with origin DNA normally. At low T-antigen concentrations, wild-type T antigen bound to origin DNA as low-molecular-weight oligomers (Fig. 7, lane 2). As the concentration of T antigen increased, oligomers with higher molecular weights formed, eventually leading to double hexamers (Fig. 7, lanes 3, 4, and 5). First, we demonstrated that mutants 429DA and 460EA displayed similar patterns of origin binding with increasing amounts of T antigen (Fig. 7, lanes 6 to 13). At low T-antigen concentrations, binding was slightly weaker than that with the wild type, suggesting that there is a partial defect in cooperative binding between individual monomers. Second, we showed that the abilities of mutants 429DA and 460EA to form double hexamers on origin DNA were stimulated with ATP just like the wild type (data not shown). These two experiments demonstrate that the origin binding and ATP binding domains of the mutants are functional and imply that the overall structure of each mutant is not dramatically altered.

FIG. 7.

Origin DNA binding assays of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens (Tag). Increasing amounts of wild-type, 429DA, and 460EA T antigens were incubated with an end-labeled DNA fragment containing the origin region. The positions of free DNA and DNA bound with T antigen in double hexamers (DH) are shown. C, control.

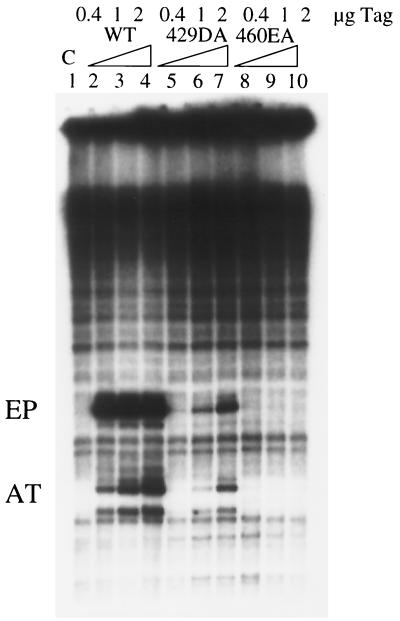

Structural distortion activity of mutants 429DA and 460EA.

When T antigen binds to the replication core origin, it melts the DNA at the EP on the early side of the central pentanucleotides and untwists the AT track on the late side. These structural alterations require ATP binding but not ATP hydrolysis (4). Since these changes may be accompanied by interactions with individual strands (51), we tested the possibility that single-stranded DNA binding is needed for structural distortion. Mutants 429DA and 460EA were therefore tested in a KMnO4 oxidation assay to detect DNA structure changes. Mutant 429DA caused very little EP or AT modification at low T-antigen concentrations (Fig. 8, lane 5), but at higher T concentrations both EP and AT signals increased severalfold (Fig. 8, lanes 6 and 7). For comparison, the EP signal induced by wild-type T antigen remained about the same with increasing amounts of T antigen, while the AT signal increased severalfold (Fig. 8, lanes 2, 3, and 4). For mutant 460EA, there was no EP or AT signal (Fig. 8, lanes 8, 9, and 10) at all T-antigen concentrations. This shows a good correlation between single-stranded DNA binding and structure distortion.

FIG. 8.

KMnO4 oxidation assay of wild-type (WT) and mutant T antigens (Tag). Increasing amounts of wild-type, 429DA, and 460EA T antigens were incubated with an origin-containing plasmid at 37°C for 30 min. The improperly paired thymine bases were modified by KMnO4 and detected by primer extension using a 32P-labeled primer. The melting signal at the EP and untwisting signal at the AT track are indicated. C, control.

DISCUSSION

The single-stranded DNA binding domain has been mapped previously to amino acid residues 259 to 627 (77). In this report we further mapped this domain by using internal deletion mutants. Our results showed that mutants with deletion of residues 251 to 300 or 501 to 550 still bound to single-stranded DNA; however, other mutants with deletions between residues 301 and 500 failed to bind to single-stranded DNA. This signifies that the single-stranded DNA binding domain probably begins after residue 301 and that the region between 501 and 550 is dispensable. Our working model is that this domain lies between residues 301 and 500.

A number of single-point substitutions were introduced within this region, and several mutants were shown to be impaired in single-stranded DNA binding. Two mutants, 429DA and 460EA, were the most defective. The mutant proteins appeared to assemble into double hexamers with origin DNA and displayed ATPase activity, suggesting that the origin binding domain (residues 147 to 247) and ATP binding domain (residues 418 to 528) were not seriously affected by the mutations. It was intriguing that 460EA was totally inactive in single-stranded DNA binding as well as in its ability to unwind DNA and to structurally distort the origin. Our interpretation is that this site is critical for an interaction with single-stranded DNA, perhaps because it is required for a structural change in T antigen during binding.

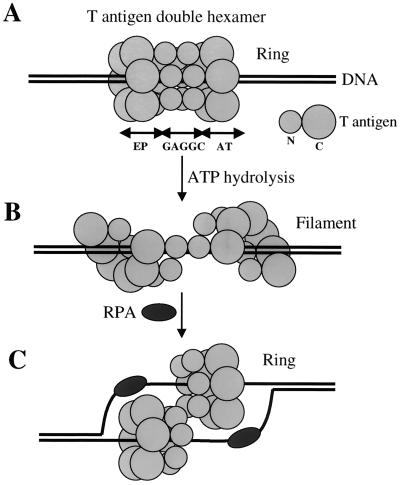

T antigen functions as a helicase during viral DNA replication (60, 75). Based primarily on footprinting data, a model had been proposed describing how T antigen associates with DNA during unwinding. T antigen forms a double hexamer, with each strand of DNA passing through the central channel of one hexamer and wrapping around the other hexamer (see Fig. 9C) (18, 50, 51, 58). Thus, interactions with single-stranded DNA may be critical for DNA unwinding. Our observation that there is a strong correlation between single-stranded DNA binding by 429DA and 460EA and origin unwinding as well as with helicase activity supports this hypothesis. Other hexameric helicases, like bacteriophage T7 helicase, also form a ring structure with one strand of DNA threaded through the hexameric ring and the other lying outside the ring (17, 23). Papilloma virus E1 probably forms a similarly shaped hexamer with single-stranded DNA (48). The crystal structures of helicases PcrA (69), hepatitis C virus NS3 (28), and Rep (29) bound to single-stranded DNA also demonstrate the importance of single-stranded DNA binding in helicase activity.

FIG. 9.

A model showing possible conformation changes to T-antigen double hexamers bound to origin DNA. (A) T antigen forms a double hexamer on origin DNA, with the DNA lying in the central channel of the closed hexameric ring on each hexamer. The N-terminal region of T antigen binds to one pair of GAGGC pentanucleotides, and the C-terminal region covers the EP or AT DNA element. The smaller and bigger circles represent the N-terminal (N) and C-terminal (C) regions of T antigen, respectively. (B) With ATP hydrolysis, the closed-ring structure of the double hexamer changes to an open filament. (C) After one strand of DNA is displaced and bound by RPA, T antigen switches back to a closed ring to function as a helicase, with each hexamer encircling one strand of DNA.

Based on these results, there are now at least five separate specific defects in T antigen that lead to an inability to unwind origin DNA. These include defects in origin binding (54, 55), in hexamer-hexamer interaction (37, 72), in oligomerization (73, 79), in ATPase activity (11, 38, 75), and now, in single-stranded DNA binding (this report).

Mutants 429DA and 460EA also showed correlation between single-stranded DNA binding and the ability to cause structure distortion of origin DNA, suggesting that single-stranded DNA binding is also needed for structural distortion. There are several pieces of evidence that suggest that structural distortion is a separate reaction from origin binding involving different regions of the protein. First, the DNA structure of an origin fragment without the two pairs of GAGGC pentanucleotide binding sites can be altered by T antigen (41), indicating that origin binding by the origin binding domain is not required for structure changes. Second, T-antigen mutants that fail to bind to origin DNA can still cause structure distortion (55). Third, the interactions between T antigen and the EP and AT regions are mostly through the sugar-phosphate backbone (51), as they are between T antigen and single-stranded DNA (50), whereas interactions with the central pentanucleotides involve direct binding to the bases (15, 24, 51, 65). Other single-stranded DNA binding proteins and helicases, such as RPA, PcrA, Rep, and NS3, also interact with the sugar-phosphate backbone when they bind to single-stranded DNA (3, 28, 29, 69). Finally, the electron microscopy image of a T-antigen double hexamer bound to origin DNA (68) suggests that the two hexamers are arranged in a head-to-head orientation, with DNA in the central channel. Each hexamer has a bilobed structure, with the N-terminal DNA binding domain forming a small lobe that is bound to a pair of pentanucleotides and the remaining C-terminal region forming a larger lobe that covers the EP or AT region (see Fig. 9A). The single-stranded DNA binding domain is located in this second region. Our finding that single-stranded binding is involved in structure distortion is consistent with this model.

When T antigen initially binds to origin DNA, the central channel of each hexamer is thought to contain double-stranded DNA. However, various models propose that there is only one strand of DNA in the central channel during unwinding. How one strand of DNA is displaced from the channel is not clear, but it probably involves a conformation change of the T-antigen hexamers. The recently resolved crystal structure of bacteriophage T7 gene 4 helicase domain may provide an answer. T7 gene 4 helicase forms an asymmetric hexamer, where two subunits are rotated by 15° and two other subunits by 30° relative to the plane of the hexamer ring (57). A slightly smaller fragment of T7 gene 4 helicase domain forms a filament instead of a closed ring (46). E. coli RecA, which has a similar nucleotide binding domain, can also form both rings and filaments (81), suggesting that rings and filaments are alternate structures that form during binding to DNA. Since the C-terminal region of T antigen also has homology with RecA (49), it is possible that the same changes occur in T antigen. In this model, a ring-to-filament conformation change would take place after the double hexamer forms on origin DNA (Fig. 9). This would permit one strand to be displaced and to associate with the single-stranded DNA binding protein RPA. Since there is evidence that T antigen interacts with only a single strand at the EP and AT regions (51), the DNA strand at each region might still be associated with T antigen through its single-stranded DNA binding activity after the transfer reaction. Afterwards, T antigen would reassemble into a hexameric closed ring to function as a helicase during DNA unwinding at replication forks.

In summary, there appear to be at least two steps during DNA replication where single-stranded DNA binding activity is required. One, this activity is needed shortly after DNA binding when the origin undergoes structure distortion (step A in Fig. 9). Two, it is needed during DNA unwinding in order to properly interact with the displaced strands (step C in Fig. 9).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants CA36118 from the National Cancer Institute and RR11820 from the National Center for Research Resources.

We are indebted to Judy Tevethia and Tim Kierstead for T-antigen internal deletion mutants. We thank Pamela Trowbridge for critical reading of the manuscript, and we are grateful to the University of Delaware cell biology facility for excellent cell culture and DNA sequencing services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur A K, Höss A, Fanning E. Expression of simian virus 40 T antigen in Escherichia coli: localization of T-antigen origin DNA-binding domain to within 129 amino acids. J Virol. 1988;62:1999–2006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.1999-2006.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird L E, Subramanya H S, Wigley D B. Helicases: a unifying structural theme? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:14–18. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochkarev A, Pfuetzner R A, Edwards A M, Frappier L. Structure of the single-stranded-DNA-binding domain of replication protein A bound to DNA. Nature. 1997;385:176–181. doi: 10.1038/385176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowiec J A, Hurwitz J. Localized melting and structural changes in the SV40 origin of replication induced by T-antigen. EMBO J. 1988;7:3149–3158. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowiec J A, Dean F B, Hurwitz J. Differential induction of structural changes in the simian virus 40 origin of replication by T antigen. J Virol. 1991;65:1228–1235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1228-1235.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley M K, Griffin J, Livingston D M. Relationship of oligomerization to enzymatic and DNA binding properties of the SV40 large T antigen. Cell. 1982;28:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley M K, Smith T F, Lathrop R H, Livingston D M, Webster T A. Consensus topography in the ATP binding site of the simian virus 40 and polyomavirus large tumor antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4026–4030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark R, Lane D P, Tjian R. Use of monoclonal antibodies as probes of simian virus 40 T antigen ATPase activity. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11854–11858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark R, Peden K, Pipas J M, Nathans D, Tjian R. Biochemical activities of T-antigen proteins encoded by simian virus 40 A gene deletion mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:220–228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole C N, Tornow J, Clark R, Tjian R. Properties of the simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigens encoded by SV40 mutants with deletions in gene A. J Virol. 1986;57:539–546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.539-546.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins B S, Pipas J M. T antigens encoded by replication-defective simian virus 40 mutants dl1135 and 5080. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15377–15384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean F B, Hurwitz J. Simian virus 40 large T antigen untwists DNA at the origin of DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5062–5071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean F B, Borowiec J A, Eki T, Hurwitz J. The simian virus 40 T antigen double hexamer assembles around the DNA at the replication origin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14129–14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean F B, Bullock P, Murakami Y, Wobbe C R, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. Simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA replication: SV40 large T antigen unwinds DNA containing the SV40 origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:16–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLucia A L, Lewton B A, Tjian R, Tegtmeyer P. Topography of simian virus 40 A protein-DNA complexes: arrangement of pentanucleotide interaction sites at the origin of replication. J Virol. 1983;46:143–150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.1.143-150.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodson M, Dean F B, Bullock P, Echols H, Hurwitz J. Unwinding of duplex DNA from the SV40 origin of replication by T antigen. Science. 1987;238:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.2823389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egelman H H, Yu X, Wild R, Hingorani M M, Patel S S. Bacteriophage T7 helicase/primase proteins form rings around single-stranded DNA that suggest a general structure for hexameric helicases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3869–3873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falaschi A. Eukaryotic DNA replication: a model for a fixed double replisome. Trends Genet. 2000;16:88–92. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01917-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gai D, Roy R, Wu C, Simmons D T. Topoisomerase I associates specifically with simian virus 40 large-T-antigen double hexamer-origin complexes. J Virol. 2000;74:5224–5232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5224-5232.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giacherio D, Hager L P. A poly(dT)-stimulated ATPase activity associated with simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8113–8116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetz G S, Dean F B, Hurwitz J, Matson S W. The unwinding of duplex regions in DNA by the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen-associated DNA helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V, Wolf Y I. A new superfamily of putative NTP-binding domains encoded by genomes of small DNA and RNA viruses. FEBS Lett. 1990;262:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80175-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacker K J, Johnson K A. A hexameric helicase encircles one DNA strand and excludes the other during DNA unwinding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14080–14087. doi: 10.1021/bi971644v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones K A, Tjian R. Essential contact residues within SV40 large T antigen binding sites I and II identified by alkylation-interference. Cell. 1984;36:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joo W S, Kim H Y, Purviance J D, Sreekumar K R, Bullock P A. Assembly of T-antigen double hexamers on the simian virus 40 core origin requires only a subset of the available binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2677–2687. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joo W S, Luo X, Denis D, Kim H Y, Rainey G J, Jones C, Sreekumar K R, Bullock P A. Purification of the simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen DNA-binding domain and characterization of its interactions with the SV40 origin. J Virol. 1997;71:3972–3985. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3972-3985.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kierstead T D, Tevethia M J. Association of p53 binding and immortalization of primary C57BL/6 mouse embryo fibroblasts by using simian virus 40 T-antigen mutants bearing internal overlapping deletion mutations. J Virol. 1993;67:1817–1829. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1817-1829.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J L, Morgenstern K A, Griffith J P, Dwyer M D, Thomson J A, Murcko M A, Lin C, Caron P R. Hepatitis C virus NS3 RNA helicase domain with a bound oligonucleotide: the crystal structure provides insights into the mode of unwinding. Structure. 1998;6:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korolev S, Hsieh J, Gauss G H, Lohman T M, Waksman G. Major domain swiveling revealed by the crystal structures of complexes of E. coli Rep helicase bound to single-stranded DNA and ADP. Cell. 1997;90:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin H-J L, Upson R, Simmons D T. Nonspecific DNA binding activity of simian virus 40 large T antigen: evidence for the cooperation of two regions for full activity. J Virol. 1992;66:5443–5452. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5443-5452.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loeber G, Parsons R, Tegtmeyer P. The zinc finger region of simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Virol. 1989;63:94–100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.94-100.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masterson P J, Stanley M A, Lewis A P, Romanos M A. A C-terminal helicase domain of the human papillomavirus E1 protein binds E2 and the DNA polymerase alpha-primase p68 subunit. J Virol. 1998;72:7407–7419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7407-7419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mastrangelo I A, Hough P V C, Wall J S, Dodson M, Dean F B, Hurwitz J. ATP-dependent assembly of double hexamers of SV40 T antigen at the viral origin of DNA replication. Nature. 1989;338:658–662. doi: 10.1038/338658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCutchan J H, Pagano J S. Enhancement of the infectivity of simian vius 40 deoxyribonucleic acid with diethylaminoethyldextran. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968;41:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McVey D, Strauss M, Gluzman Y. Properties of the DNA-binding domain of the simian virus 40 large T antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5525–5536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melendy T, Stillman B. An interaction between replication protein A and SV40 T antigen appears essential for primosome assembly during SV40 DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3389–3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moarefi I F, Small D, Gilbert I, Hopfner M, Randall S K, Schneider C, Russo A A, Ramsperger U, Arthur A K, Stahl H, Kelly T J, Fanning E. Mutation of the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation site in simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen specifically blocks SV40 origin DNA unwinding. J Virol. 1993;67:4992–5002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4992-5002.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohr I J, Fairman M P, Stillman B, Gluzman Y. Large T-antigen mutants define multiple steps in the initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication. J Virol. 1989;63:4181–4188. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4181-4188.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami Y, Hurwitz J. Functional interactions between SV40 T antigen and other replication proteins at the replication fork. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11008–11017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murakami Y, Wobbe C R, Weissbach L, Dean F B, Hurwitz J. Role of DNA polymerase alpha and DNA primase in simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2869–2873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parsons R, Anderson M E, Tegtmeyer P. Three domains in the simian virus 40 core origin orchestrate the binding, melting, and DNA helicase activities of T antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:509–518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.509-518.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfuetzner R A, Bochkarev A, Frappier L, Edwards A M. Replication protein A. Characterization and crystallization of the DNA binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:430–434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porter D J. A kinetic analysis of the oligonucleotide-modulated ATPase activity of the helicase domain of the NS3 protein from hepatitis C virus. The first cycle of interaction of ATP with the enzyme is unique. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14247–14253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prelich G, Tan C K, Kostura M, Mathews M B, So A G, Downey K M, Stillman B. Functional identity of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and a DNA polymerase-delta auxiliary protein. Nature. 1987;326:517–520. doi: 10.1038/326517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts J M, D'Urso G. Cellular and viral control of the initiation of DNA replication. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1989;12:171–182. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1989.supplement_12.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawaya M R, Guo S, Tabor S, Richardson C C, Ellenberger T. Crystal structure of the helicase domain from the replicative helicase-primase of bacteriophage T7. Cell. 1999;99:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheffner M, Knippers R, Stahl H. RNA unwinding activity of SV40 large T antigen. Cell. 1989;57:955–963. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sedman J, Stenlund A. The papillomavirus E1 protein forms a DNA-dependent hexameric complex with ATPase and DNA helicase activities. J Virol. 1998;72:6893–6897. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6893-6897.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seif R. New properties of simian virus 40 large T antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1463–1471. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.12.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.SenGupta D J, Borowiec J A. Strand-specific recognition of a synthetic DNA replication fork by the SV40 large tumor antigen. Science. 1992;256:1656–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5064.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.SenGupta D J, Borowiec J A. Strand and face: the topography of interactions between the SV40 origin of replication and T-antigen during the initiation of replication. EMBO J. 1994;13:982–992. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simanis V, Lane D P. An immunoaffinity purification procedure for SV40 large T antigen. Virology. 1985;144:88–100. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simmons D T, Wun-Kim K, Young W. Identification of simian virus 40 T antigen residues important for specific and nonspecific binding to DNA and for helicase activity. J Virol. 1990;64:4858–4865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4858-4865.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simmons D T, Loeber G, Tegtmeyer P. Four major sequence elements of simian virus 40 large T antigen coordinate its specific and nonspecific DNA binding. J Virol. 1990;64:1973–1983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1973-1983.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simmons D T, Upson R, Wun-Kim K, Young W. Biochemical analysis of mutants with changes in the origin-binding domain of simian virus 40 tumor antigen. J Virol. 1993;67:4227–4236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4227-4236.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simmons D T, Roy R, Chen L, Gai D, Trowbridge P W. The activity of topoisomerase I is modulated by large T antigen during unwinding of the SV40 origin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20390–20396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singleton M R, Sawaya M R, Ellenberger T, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of T7 gene 4 ring helicase indicates a mechanism for sequential hydrolysis of nucleotides. Cell. 2000;101:589–600. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smelkova N V, Borowiec J A. Synthetic DNA replication bubbles bound and unwound with twofold symmetry by a simian virus 40 T-antigen double hexamer. J Virol. 1998;72:8676–8681. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8676-8681.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soultanas P, Dillingham M S, Wiley P, Webb M R, Wigley D B. Uncoupling DNA translocation and helicase activity in PcrA: direct evidence for an active mechanism. EMBO J. 2000;19:3799–3810. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stahl H, Droge P, Knippers R. DNA helicase activity of SV40 large tumor antigen. EMBO J. 1986;5:1939–1944. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stillman B, Gerard R D, Guggenheimer R A, Gluzman Y. T antigen and template requirements for SV40 DNA replication in vitro. EMBO J. 1985;4:2933–2939. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Subramanya H S, Bird L E, Brannigan J A, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of a DExx box DNA helicase. Nature. 1996;384:379–383. doi: 10.1038/384379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tegtmeyer P. Simian virus 40 deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis: the viral replicon. J Virol. 1972;10:591–598. doi: 10.1128/jvi.10.4.591-598.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Theis K, Chen P J, Skorvaga M, Van Houten B, Kisker C. Crystal structure of UvrB, a DNA helicase adapted for nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J. 1999;18:6899–6907. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tjian R. Protein-DNA interactions at the origin of simian virus 40 DNA replication. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1978;43:655–662. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1979.043.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tjian R. The binding site of SV40 DNA for a T antigen-related protein. Cell. 1978;13:165–179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsurimoto T, Stillman B. Purification of a cellular replication factor, RF-C, that is required for coordinated synthesis of leading and lagging strands during simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:609–619. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Valle M, Gruss C, Halmer L, Carazo J M, Donate L E. Large T-antigen double hexamers imaged at the simian virus 40 origin of replication. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:34–41. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.34-41.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Velankar S S, Soultanas P, Dillingham M S, Subramanya H S, Wigley D B. Crystal structures of complexes of PcrA DNA helicase with a DNA substrate indicate an inchworm mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Waga S, Stillman B. Anatomy of a DNA replication fork revealed by reconstitution of SV40 DNA replication in vitro. Nature (London) 1994;369:207–212. doi: 10.1038/369207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weinberg D H, Collins K L, Simancek P, Russo A, Wold M S, Virshup D M, Kelly T J. Reconstitution of simian virus 40 DNA replication with purified proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8692–8696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weisshart K, Taneja P, Jenne A, Herbig U, Simmons D T, Fanning E. Two regions of simian virus 40 T antigen determine cooperativity of double-hexamer assembly on the viral origin of DNA replication and promote hexamer interactions during bidirectional origin DNA unwinding. J Virol. 1999;73:2201–2211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2201-2211.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weisshart K, Bradley M K, Weiner B M, Schneider C, Moarefi I, Fanning E, Arthur A K. An N-terminal deletion mutant of simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen oligomerizes incorrectly on SV40 DNA but retains the ability to bind to DNA polymerase alpha and replicate SV40 DNA in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:3509–3516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3509-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wessel R, Schweizer J, Stahl H. Simian virus 40 T-antigen DNA helicase is a hexamer which forms a binary complex during bidirectional unwinding from the viral origin of DNA replication. J Virol. 1992;66:804–815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.804-815.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiekowski M, Schwarz M W, Stahl H. Simian virus 40 large T antigen DNA helicase. Characterization of the ATPase-dependent DNA unwinding activity and its substrate requirements. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:436–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wold M S, Li J J, Kelly T J. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro: large-tumor-antigen- and origin-dependent unwinding of the template. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3643–3647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu C, Edgil D, Simmons D T. The origin DNA-binding and single-stranded DNA-binding domains of simian virus 40 large T antigen are distinct. J Virol. 1998;72:10256–10259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10256-10259.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wun-Kim K, Simmons D T. Mapping of helicase and helicase substrate binding domains on simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:2014–2020. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2014-2020.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wun-Kim K, Upson R, Young W, Melendy T, Stillman B, Simmons D T. The DNA-binding domain of simian virus 40 tumor antigen has multiple functions. J Virol. 1993;67:7608–7611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7608-7611.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yao N, Hesson T, Cable M, Hong Z, Kwong A D, Le H V, Weber P C. Structure of the hepatitis C virus RNA helicase domain. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nsb0697-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu X, Egelman E H. The RecA hexamer is a structural homologue of ring helicases. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nsb0297-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]