Abstract

The role of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF1α) in the regulation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) transcription and replication in vivo was investigated using a HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mouse model. HBV transcription was not measurably affected by the absence of the HNF1α transcription factor. However, intracellular viral replication intermediates were increased two- to fourfold in mice lacking functional HNF1α protein. The increase in encapsidated cytoplasmic replication intermediates in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice was associated with the appearance of nonencapsidated nuclear covalently closed circular (CCC) viral genomic DNA. Viral CCC DNA was not readily detected in HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice. This indicates the synthesis of nuclear HBV CCC DNA, the proposed viral transcriptional template found in natural infection, is regulated either by subtle alterations in the levels of viral transcripts or by changes in the physiological state of the hepatocyte in this in vivo model of HBV replication.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an enveloped virus that infects the livers of humans and other primates (1, 20). In infected hepatocytes, the 3.2-kb DNA genome is transcribed by the cellular RNA polymerase II, generating the 3.5-, 2.4-, 2.1-, and 0.7-kb viral RNAs (7). These transcripts encode the nucleocapsid polypeptides, the large surface antigen polypeptide, the middle and major surface antigen polypeptides, and the X-gene polypeptide, respectively (7). In addition, the 3.5-kb pregenomic RNA encodes the viral polymerase and is reverse transcribed by this polypeptide within the viral nucleocapsid to produce the 3.2-kb viral genomic DNA (16). The mature nucleocapsids containing viral genomic DNA can be secreted from the cell in virus particles only by associating with surface antigen polypeptides within the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (2, 3, 8). Virus buds into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum and is transported out of the cell through the Golgi apparatus (12, 28). The ability of the mature nucleocapsid to form virus particles depends on the correct level of synthesis of the surface antigen polypeptides (2). In the absence of surface antigen polypeptide synthesis, the mature nucleocapsids would be expected to transport the viral genome back into the nucleus, where the partially double-stranded viral genome is converted into covalently closed circular (CCC) DNA that represents the proposed viral transcriptional template. Therefore, the level of transcription of the 2.4- and 2.1-kb viral RNAs, in addition to the 3.5-kb pregenomic RNA, is likely to influence viral replication in general and nuclear HBV CCC DNA accumulation in particular.

As the relative abundance of mature nucleocapsids and surface antigen polypeptides is likely to be influenced by the levels of their corresponding RNAs, the regulation of the level of viral transcription is expected to influence directly viral replication. Using transient transfection analysis in various cell culture systems, it has been demonstrated that the transcription of the HBV genome is regulated by a variety of ubiquitous and liver-enriched transcription factors (22, 29). However, the relationship between viral transcription and replication has not been extensively examined, and so the importance of specific transcription factors in regulating HBV replication is poorly defined. In addition, the in vivo importance of specific transcription factors in regulating viral replication has only recently been initiated using a transgenic mouse model (10).

In this study, the role of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF1α) in regulating viral transcription and replication was examined in an HBV transgenic mouse model system (11). In transient transfection analysis, it has been demonstrated previously that HNF1α regulates the level of transcription from the large surface antigen promoter (18, 19, 31). This observation predicts that the loss of HNF1α might be associated with a reduction in the level of the 2.4-kb HBV RNA and the large surface antigen polypeptide that it encodes. As the large surface antigen polypeptide is essential for viral biosynthesis, the loss of HNF1α might be expected to limit viral biosynthesis and lead to an increased abundance of mature capsids in the cytoplasm of the cell. In turn, these mature capsids may deliver their viral genomes to the nucleus to amplify the pool of CCC DNA, as is observed in duck hepatitis B virus infection (14, 24, 26). To examine whether this occurs in vivo, the viral replication intermediates present in the liver of HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice were examined. The levels of the HBV RNAs, including the 2.4-kb viral transcript, in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice were similar to the levels present in HBV transgenic mice expressing HNF1α. However, nuclear HBV CCC DNA was present in the hepatocytes of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice. This suggests that subtle alterations in the levels of the HBV RNAs resulting from the absence of HNF1α may have resulted in the translocation of HBV genomic DNA into the nucleus of the hepatocytes. Alternatively, the absence of HNF1α may alter the physiological properties of the hepatocytes in a manner that favors the translocation of HBV genomic DNA into the nucleus. In either case, it is apparent that cycling of encapsidated HBV DNA from the cytoplasm into the nucleus can occur in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mouse model and represents a system where the molecular events regulating this aspect of the HBV life cycle can be analyzed in detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic and knockout mice.

The production and characterization of the HBV transgenic mouse lineage 1.3.32 have been described elsewhere (11). These HBV transgenic mice contain a single copy of the terminally redundant, 1.3-genome-length copy of the HBV ayw genome integrated into the mouse chromosomal DNA. High levels of HBV replication occur in the livers of these mice. The mice used in the breeding experiments were homozygous for the HBV transgene and were maintained on the C57BL/6 genetic background.

The production and characterization of the HNF1α-null mice have been described elsewhere (17). These mice do not express HNF1α and display hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, renal Fanconi syndrome, and infertility (13, 17). The mice used in the breeding experiments were heterozygous for HNF1α and maintained on the Sv/129 genetic background.

HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice were generated by mating the HBV transgenic mice with the HNF1α heterozygous mice. The resulting HNF1α heterozygous HBV transgenic F1 mice were subsequently mated with the HNF1α heterozygous mice, and the F2 mice were screened for the HBV transgene and HNF1α null allele by PCR analysis of tail DNA. Tail DNA was prepared by incubating 1 cm of tail in 500 μl of 100 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.0)–200 mM NaCl–5 mM EDTA, 0.2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate containing proteinase K (100 μg/ml) for 16 to 20 h at 55°C. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge for 5 min, and the supernatant was precipitated with 500 μl of isopropanol. DNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge for 5 min and subsequently dissolved in 100 μl of 5 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA. The HBV transgene was identified by PCR analysis using the oligonucleotides XpHNF4-1 (TCGATACCTGAACCTTTACCCCGTTGCCCG; HBV coordinates 1133 to 1159) and CpHNF4-2 (TCGAATTGCTGAGAGTCCAAGAGTCCTCTT; HBV coordinates 1683 to 1658) and 1 μl of tail DNA. The samples were subjected to 30 amplification cycles involving denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension from the primers at 72°C for 2 min. A PCR product of 551 bp indicated the presence of the HBV transgene. The HNF1α wild-type and null alleles were identified by PCR analysis using the oligonucleotides mHNF1α-1 (CAGAGCTTGACTAGTGGGATTTGG; HNF1α promoter plus strand sequence), mHNF1α-2 (ACCCTCTCCAACCATCAGGTAGG; HNF1α exon 1 minus strand sequence), and BGAL (AACTGTTGGGAAGGGCGATCGGTG; β-galactosidase minus-strand sequence) and 1 μl of tail DNA. The samples were subjected to 35 amplification cycles involving denaturation at 96°C for 1 min, annealing at 56°C for 1 min, and extension from the primers at 72°C for 1 min. A PCR product of 276 bp indicated the wild-type HNF1α genotype, whereas a PCR product of 390 bp indicated the mutated HNF1α genotype. The 20-μl reaction conditions used were as described by the manufacturer (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and contained 1 U of cloned Pfu DNA polymerase.

HBV DNA and RNA analysis.

Total DNA and RNA were isolated from livers and brains of HBV transgenic mice as described elsewhere (4, 21). Protein-free DNA was isolated identically to the total DNA except the proteinase K digestion was omitted. DNA (Southern) filter hybridization analyses were performed using 20 μg of restriction enzyme digested DNA or the DNA recovered from the same number of cell equivalents as described elsewhere (21). Filters were probed with 32P-labeled HBV ayw genomic DNA or 750-nucleotide single-stranded HBV riboprobes (HBV coordinates 828 to 1577) (6) to detect HBV sequences. RNA (Northern) filter hybridization analyses were performed using 10 μg of total cellular RNA as described elsewhere (21). Filters were probed with 32P-labeled HBV ayw genomic DNA to detect HBV sequences and the human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA to detect the GAPDH transcript used as an internal control (25).

RNase protection assays were performed using a Pharmingen Riboquant kit, and riboprobes were synthesized using an Ambion Maxiscript kit as described by the manufacturers. Transcription initiation sites for the 3.5-kb HBV transcripts were examined using 20 μg of total cellular RNA and a 333 (HBV coordinates 1990 to 1658)-nucleotide-long 32P-labeled HBV riboprobe. The transcription initiation site for the 2.4-kb HBV transcript was examined using 20 μg of total cellular RNA and a 327 (HBV coordinates 2708 to 3034)- or 347 (HBV coordinates 2708 to 3054)-nucleotide-long 32P-labeled HBV riboprobe. As an internal control for the RNase protection analysis, a 32P-labeled mouse ribosomal protein L32 gene riboprobe spanning 101 nucleotides of exon 3 was used (5). All riboprobes contained additional flanking vector sequences of 80 to 90 nucleotides that are not protected by HBV transgenic mouse RNA.

Total, nuclear, and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared from mouse livers by a modification of a previously described procedure (23). Briefly, liver samples were homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem tissue grinder in 5 ml of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–25 mM KCl–1.0 mM EGTA–1.0 mM EDTA–0.32 M sucrose–1.0 mM dithiothreitol (buffer A). Total HBV DNA, with or without micrococcal nuclease and proteinase K treatment, was prepared from 1 ml of this homogenate. The remaining homogenate was centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm in a Sorvall HB-4 rotor at 4°C. The supernatant represented the cytoplasmic fraction that was analyzed for HBV replication intermediates, with or without micrococcal nuclease and proteinase K treatment. The nuclear pellet was suspended in 5 ml of buffer A, diluted with 10 ml of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–25 mM KCl–1.0 mM EGTA–1.0 mM EDTA–2.0 M sucrose–1.0 mM dithiothreitol (buffer B), and centrifuged over two 3.5-ml sucrose cushions of buffer B for 30 min at 24,000 rpm in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 4°C. The two nuclear pellets were suspended together in 1 ml of buffer A and analyzed further with or without micrococcal nuclease and proteinase K treatment. Total, nuclear, and cytoplasmic fractions were adjusted to 10 mM CaCl2 and 2 U of micrococcal nuclease (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C as required. Micrococcal nuclease digestions were terminated by adjusting the fractions to 20 mM EDTA. Proteinase K was added to 100 μg/ml, and the mixture was incubated for 16 h at 37°C as required. HBV DNA was subsequently isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation prior to filter hybridization analysis.

Nuclear CCC HBV DNA was prepared from mouse livers by a modification of a previously described procedure (30). Approximately 50 mg of mouse liver was homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem tissue grinder in 5 ml of 50 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA–0.2% (vol/vol) NP-40–0.15 M NaCl at 4°C. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm in Sorvall HB-4 rotor at 4°C. The nuclear pellet was suspended in 2 ml of 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA at 4°C. Nuclei were lysed by the addition of 2 ml of 6% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate–0.1 M NaOH. The lysate was vigorously mixed and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The alkaline lysate was neutralized by the addition of 1 ml of 3 M potassium acetate (pH 4.8) and centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm in Sorvall HB-4 rotor at 4°C. The supernatant was extracted with 5 ml of water-saturated phenol and precipitated with ethanol in the presence of 10 μg of tRNA. The precipitate was suspended in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA. Then 25 μl of the isolated HBV DNA was examined by filter hybridization analysis. Filter hybridization and RNase protection analyses were quantitated by phosphorimaging using a Packard Cyclone storage phosphor system.

HBV antigen analysis.

HBeAg analysis was performed using 20 μl of mouse serum and the HBe enzyme immunoassay as described by the manufacturer (Abbott Laboratories). The level of antigen was determined in the linear range of the assay. Immunohistochemical detection of HBcAg in paraffin-embedded mouse liver sections was performed as previously described (11).

RESULTS

HNF1α has been shown to bind to the large surface antigen promoter and regulate the level of transcription from this promoter in transient transfection analysis in cell culture (18, 19, 31). This suggests that the HNF1α transcription factor may regulate the level of synthesis of the large surface antigen polypeptide and consequently viral biosynthesis, as the large surface antigen polypeptide is an essential component of the viral envelope (2). In an attempt to determine the role of HNF1α in modulating viral replication in vivo, we examined the consequences of the absence of HNF1α on HBV transcription and replication in the livers of HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice.

Effect of HNF1α on HBeAg synthesis in HBV transgenic mice.

HBV transgenic mice were bred with HNF1α-null mice, and HBV transgenic mice hemizygous for the HBV transgene and homozygous for the wild-type HNF1α allele and heterozygous or homozygous for the HNF1α null allele were identified in the F2 generation. For these studies, HBV transgenic mice that were homozygous or heterozygous for the HNF1α wild-type allele were used as controls and compared with HBV transgenic mice that were homozygous for the HNF1α null allele. Male and female mice of each genotype were assayed for the level of HBeAg in their sera (Table 1). HBeAg is translated from the 3.5-kb precore RNA, and its abundance in the sera of the HBV transgenic mice indicates the level of viral replication in the liver (10, 11). The levels of HBeAg in the sera of HNF1α-null mice were approximately 50% higher than the HBeAg in the sera of the corresponding HNF1α wild-type and -heterozygous mice of the same sex. This difference can be explained by the relatively larger livers in the HNF1α-null mice (Table 1). As previously described, the hepatomegaly present in the HNF1α-null mice is due to hepatic hyperproliferation that presumably occurs as a compensatory mechanism associated with the liver dysfunction resulting from the absence of the HNF1α transcription factor (17).

TABLE 1.

Effect of HNF1α on HBeAg synthesis in HBV transgenic mice

| Sexa | HNF1α genotypeb | Mean liver size (% of total body wt) | No. of mice | HBeAg A492c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | +/+ | 5.49 | 2 | 0.58 (0.17) |

| M | +/− | 6.51 | 2 | 0.46 (0.10) |

| M | −/− | 9.48 | 8 | 0.74 (0.15)d |

| F | +/+ | 4.89 | 6 | 0.43 (0.04) |

| F | +/− | 4.82 | 4 | 0.42 (0.11) |

| F | −/− | 10.52 | 10 | 0.66 (0.12)d |

M, male mice; F, female mice.

+/+, mice homozygous for wild-type HNF1α gene; +/−, mice heterozygous for wild-type HNF1α gene; −/−, mice homozygous for HNF1α-null gene.

Mean (and standard deviation) absorbance at 492 nm of 10 μl of serum assayed for HBeAg using the Abbott Laboratories HBe enzyme immunoassay.

The difference in the level of serum HBeAg in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice and HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice is statistically significant by an unpaired Student t test (P < 0.05).

Effect of HNF1α on viral transcription and replication in HBV transgenic mice.

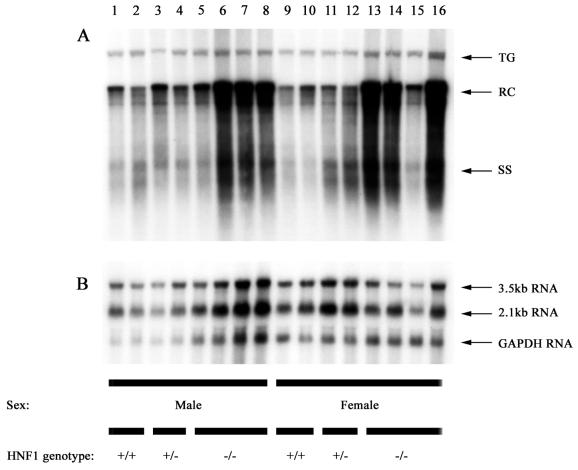

We also examined the steady-state levels of HBV transcripts and replication intermediates in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice by analysis of total liver RNA and DNA (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Analysis of the levels of the HBV 3.5- and 2.1-kb transcripts in the livers of HBV transgenic mice with and without HNF1α indicated the steady-state levels of the HBV transcripts were not influenced by this transcription factor (Fig. 1B). This result is consistent with the observations in cell culture that indicate the major surface antigen and nucleocapsid promoter activities are not regulated by HNF1 (19).

FIG. 1.

DNA (Southern) and RNA (Northern) filter hybridization analysis of HBV DNA replication intermediates (A) and transcripts (B) in livers of HBV transgenic mice. Groups of two or four mice of each sex and genotype were analyzed. The GAPDH transcript was used as an internal control for the quantitation of the HBV 3.5- and 2.1-kb RNAs. The HBV transgene (TG) was used as an internal control for the quantitation of the HBV replication intermediates. The probes used were HBV ayw genomic DNA (A) and HBV ayw genomic DNA plus GAPDH cDNA (B). RC, HBV relaxed circular replication intermediates; SS, HBV single-stranded replication intermediates; HNF1 genotype +/+, HNF1α wild-type mouse; HNF1 genotype +/−, HNF1α heterozygous mouse; HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse.

TABLE 2.

Effect of HNF1α on HBV RNA and DNA synthesis in HBV transgenic mice

| Sex | HNF1α genotype | No. of mice for RNA analysis | Mean relative levela (SD)

|

Ratio

|

No. of mice for DNA analysis | Mean RI-to-TG ratiob (SD) | Relative level of HBV RIc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV 3.5-kb RNA | HBV 2.1-kb RNA | GAPDH RNA | HBV 3.5-kb RNA to GAPDH RNA | HBV 2.1-kb RNA to GAPDH RNA | ||||||

| M | +/+ | 2 | 1.00 (0.31) | 1.71 (0.40) | 0.54 (0.01) | 1.9 | 3.2 | 2 | 37.6 (28.2) | 1.0 |

| M | +/− | 2 | 1.00 (0.37) | 1.41 (0.47) | 0.53 (0.13) | 1.9 | 2.7 | 2 | 36.5 (22.7) | 1.0 |

| M | −/− | 4 | 2.21 (0.88) | 3.57 (1.03) | 1.76 (0.52) | 1.3 | 2.0 | 9 | 89.3 (47.4) | 2.4d |

| F | +/+ | 2 | 1.47 (0.16) | 2.44 (0.44) | 1.31 (0.21) | 1.1 | 1.9 | 5 | 24.2 (13.6) | 1.0 |

| F | +/− | 2 | 2.16 (0.16) | 3.58 (0.46) | 1.42 (0.19) | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3 | 36.6 (11.5) | 1.5 |

| F | −/− | 4 | 1.30 (0.64) | 2.25 (0.67) | 1.67 (0.13) | 0.8 | 1.3 | 11 | 129.2 (98.6) | 5.3d |

Determined from Fig. 1. The level of HBV 3.5-kb RNA in male HBV transgenic mice possessing two wild-type copies of the HNF1α gene was designated 1.00.

Ratios of HBV replication intermediate DNA (RI) to the HBV transgene DNA (TG) were determined from Fig. 1 and additional similar analysis.

Determined from the adjacent column. The level of HBV RI DNA in male HBV transgenic mice possessing two wild-type copies of the HNF1α gene was designated 1.0

The difference in levels of HBV RI DNAs in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice is statistically significantly different from the level of HBV RI DNAs in HNF1-expressing HBV transgenic mice by a Student t test (P < 0.05).

The levels of replication intermediates in the livers of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice were approximately two- and fourfold higher in male and female mice, respectively, than in HBV transgenic mice expressing functional HNF1α (Fig. 1A and Table 2). The reason for this difference in the level of replication intermediates is unclear, considering that the levels of the 3.5- and 2.1-kb HBV transcripts are unaffected by HNF1α (Fig. 1B and Table 2). We examined by RNase protection analysis the possibility that HNF1α might affect the relative ratio of the precore and pregenomic 3.5-kb HBV RNAs but observed no effect of HNF1α (Fig. 2). Therefore, a measurable alteration in the level of the pregenomic RNA, the template for viral replication, cannot explain the increased level of replication intermediates in the livers of the HNF1α-null mice.

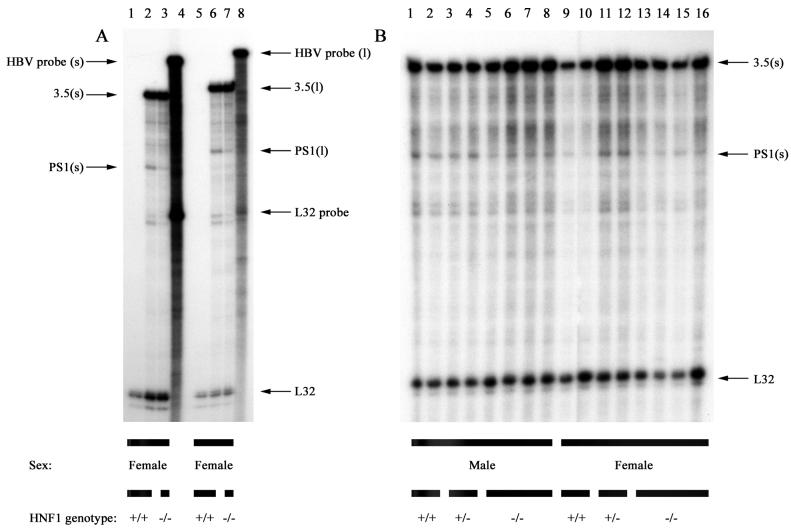

FIG. 2.

RNase protection analysis mapping the transcription initiation sites of the precore (PC) and pregenomic (C) transcripts from livers of HBV transgenic mice. The 3′ ends of all HBV transcripts corresponding to the polyadenylation site (pA) of these RNAs also generated a protected fragment in this analysis. Groups of two or four mice of each sex and genotype were analyzed. The riboprobes used included the HBV ayw sequence spanning nucleotide coordinates 1990 to 1658 and the mouse ribosomal protein L32 gene riboprobe spanning 101 nucleotides of exon 3. The 3.5-kb HBV RNAs protect fragments of 283 (pA), 206 (PC), and 175 (C) nucleotides, respectively. The mouse ribosomal protein L32 RNA protects a fragment of 101 nucleotides, designated L32, when probed with the L32 probe. HNF1 genotype +/+, HNF1α wild-type mouse; HNF1 genotype +/−, HNF1α heterozygous mouse; HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse.

As HNF1α regulates the activity of the large surface antigen promoter in cell culture (19), it might be expected that the absence of this transcription factor in vivo would result in a reduction of the 2.4-kb HBV transcript that encodes the large surface antigen polypeptide. This was investigated by performing RNase protection analysis of the 2.4-kb HBV RNA initiation site (Fig. 3). Initially, two riboprobes were used to map the transcription initiation site of the 2.4-kb HBV RNA (Fig. 3A). The 2.4-kb HBV RNA, initiating at nucleotide coordinate 2809, was predicted to protect 226 and 246 nucleotides of the HBV riboprobes, respectively. Protected RNAs of approximately these sizes were detected with total liver RNA from HBV transgenic mice and HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice but not with total liver RNA from a nontransgenic mouse (Fig. 3A). These observations strongly suggest that the 226- and 246-nucleotide regions of the riboprobes were protected from degradation by hybridizing to the 2.4-kb HBV RNA. The protected RNAs of 327 and 347 nucleotides spanning the complete HBV sequence present in the riboprobes represent hybridization with the 3.5-kb HBV RNAs. Based on this RNase protection assay, we examined the level of the 2.4-kb HBV RNA in HBV transgenic mice expressing or lacking HNF1α (Fig. 3B). From comparison of the 2.4-kb HBV RNA with either the endogenous mouse ribosomal protein L32 RNA or the 3.5-kb HBV RNA, it was apparent that HNF1α altered the level of the 2.4-kb HBV RNA less than twofold in these HBV transgenic mice. Therefore, it appears that HNF1α is not a major regulator of 2.4-kb HBV RNA synthesis in vivo in the HBV transgenic mouse model system. This is in direct contrast to the regulatory effect that this transcription factor has been shown to have on the large surface antigen promoter activity in cell culture analysis (18, 19, 31).

FIG. 3.

RNase protection analysis mapping the transcription initiation sites of the large surface antigen transcript from livers of HBV transgenic mice. Groups of two or four mice of each sex and genotype were analyzed. Non-HBV transgenic mouse liver RNA was analyzed in panel A, lanes 1 and 5. The riboprobes used (A, lanes 4 and 8) included the HBV ayw sequence spanning nucleotide coordinates 3034 to 2708 [A, lanes 1 to 4; B, HBV probe (s)], the HBV ayw sequence spanning nucleotide coordinates 3054 to 2708 [A, lanes 5 to 8, HBV probe (l)] and the mouse ribosomal protein L32 gene riboprobe spanning 101 nucleotides of exon 3 (A and B, L32 probe). The 3.5-kb HBV RNA protects fragments of 327 and 347 nucleotides, designated 3.5(s) and 3.5(l), when probed with the HBV probes (s) and (l), respectively. The 2.4-kb HBV RNA protects fragments of 226 and 246 nucleotides, designated PS1(s) and PS1(l), when probed with the HBV probes (s) and (l), respectively. The mouse ribosomal protein L32 RNA protects a fragment of 101 nucleotides, designated L32, when probed with the L32 probe. HNF1 genotype +/+, HNF1α wild-type mouse; HNF1 genotype +/−, HNF1α heterozygous mouse; HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse.

Effect of HNF1α on viral HBcAg distribution in livers of HBV transgenic mice.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the livers of HBV transgenic mice demonstrated that HNF1α influences the distribution of HBcAg within the liver lobule (Fig. 4). In both male and female HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice, the HBcAg staining is both nuclear and cytoplasmic in the hepatocytes located around the central vein. HBcAg staining is limited to the nuclei of hepatocytes located further from the central vein and is considerably reduced within hepatocytes surrounding the portal vein. In contrast, HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice display nuclear and cytoplasmic HBcAg staining in the majority of stained hepatocytes. The hepatocytes immediately surrounding the portal vein region display very little HBcAg staining in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice. As cytoplasmic HBcAg correlates with viral replication (11), these observations suggest that all of the cells expressing HBcAg in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice are replicating virus. This contrasts with the HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice, where replication is probably quite limited in the hepatocytes that display only nuclear HBcAg staining. These staining patterns correlate with the increase in viral replication observed in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 1). The level of HBsAg in the HNF1α-null and HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice was below the level of detection by immunohistochemical analysis, preventing localization of the HBV envelope polypeptides within the liver (A. K. Raney et al., unpublished data).

FIG. 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of HBcAg in livers of HBV transgenic mice. Nuclear staining of HBcAg is observed throughout the liver, whereas cytoplasmic staining is located primarily in the centrolobular hepatocytes in the livers of male (M) and female (F) heterozygous HNF1α (+/−) HBV transgenic mice (left). HNF1α-null (−/−) HBV transgenic mice display primarily both nuclear and cytoplasmic HBcAg staining that extends toward the periportal hepatocytes (right). The size bar represents 500 μm.

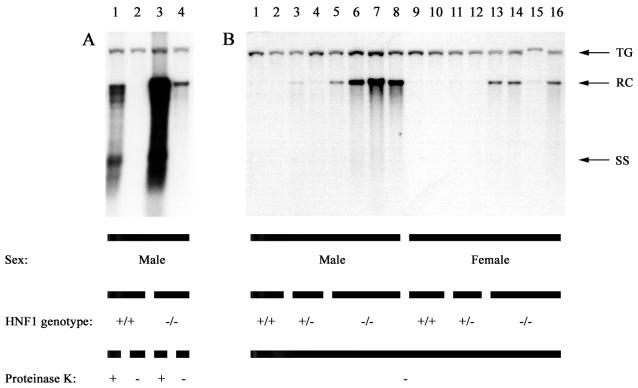

Effect of HNF1α on protein-free viral replication intermediates in HBV transgenic mice.

The HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice did not display any major alterations in levels of viral RNAs but did show higher levels of replication intermediates in the liver compared with HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 1 and Table 2). It was originally assumed that the loss of HNF1α would result in lower levels of the 2.4-kb HBV transcript and the large surface antigen polypeptide that it encodes. This was expected to reduce the rate of viral biosynthesis, permitting the cycling of mature nucleocapsids containing viral genomic DNA into the nucleus. In the nucleus during a natural infection, the partially double stranded genome containing the terminal protein attached to the 5′ end of its minus-strand DNA is converted to CCC DNA that serves as a template for transcription. To examine the possibility that a process similar to this might be occurring in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice, the livers of these mice were examined for the presence of HBV genomic DNA that did not have terminal protein attached to the viral replication intermediates (Fig. 5). In HBV transgenic mice expressing HNF1α, essentially all of the detectable replication intermediates are eliminated by extraction with phenol if they are not first digested with proteinase K (Fig. 5A). This indicates that the replication intermediates in the livers of these mice are covalently attached to protein, presumably the HBV terminal protein essential for priming minus-strand synthesis (9). In contrast, approximately 1 to 3% of the replication intermediates, representing approximately one viral genome per hepatocyte in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice, are not extracted with phenol in the absence of prior proteinase K digestion (Fig. 5A). This result indicates the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice synthesize a protein-free replication intermediate that migrates as a 3.2-kb relaxed circular (RC) form in their livers. These observations were extended to include the mice analyzed for total replication intermediates (Fig. 1); it was apparent that all HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice possess the 3.2-kb protein-free RC HBV DNA replication intermediate, whereas it is not obviously detectable in HBV transgenic mice expressing HNF1α (Fig. 5B). Phosphorimaging analysis suggested that the level of the 3.2-kb protein-free RC HBV DNA replication intermediate is at least 15-fold lower in HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice than in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice.

FIG. 5.

DNA (Southern) filter hybridization analysis of protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates in livers of HBV transgenic mice. Groups of two or four mice of each sex and genotype were analyzed. Total HBV DNA replication intermediates (+ proteinase K) were compared with protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates (− proteinase K) (A). Protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates are present in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (B). The HBV transgene (TG) was used as an internal control for the quantitation of the HBV replication intermediates. The probe used was HBV ayw genomic DNA. RC, HBV relaxed circular replication intermediates; SS, HBV single-stranded replication intermediates; HNF1 genotype +/+, HNF1α wild-type mouse; HNF1 genotype +/−, HNF1α heterozygous mouse; HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse.

Characterization of the protein-free RC DNA viral replication intermediates present in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice.

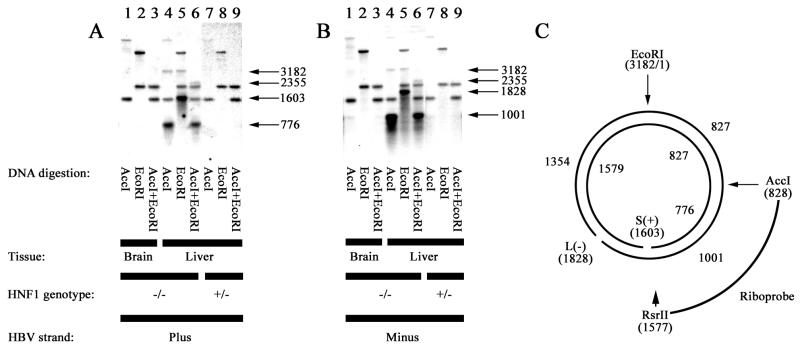

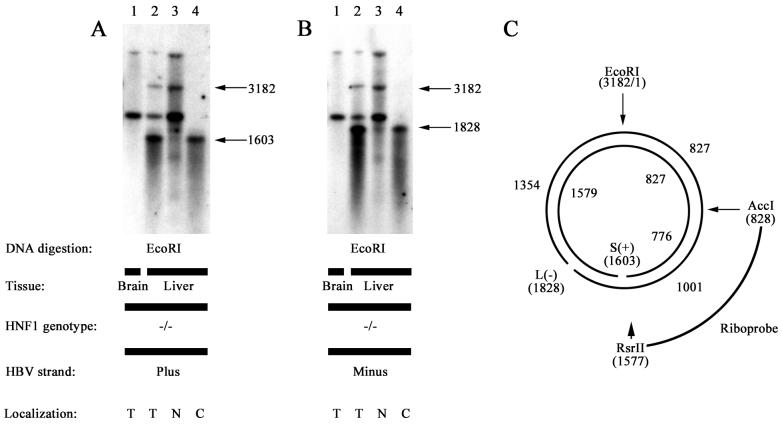

The structure of the protein-free RC DNA present in livers of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice was initially characterized by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA filter hybridization analysis (Fig. 6). Restriction enzyme digestion of the protein-free RC DNA was performed prior to denaturation and separation of the single-stranded DNA fragments by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis. To distinguish the HBV transgene DNA fragments from the protein-free RC DNA, total DNA isolated from the brain of the mouse, where HBV DNA does not replicate, was analyzed as a control (Fig. 6, lanes 1 to 3). Liver DNA isolated from a HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice without proteinase K treatment was also analyzed and yielded the same results as total brain DNA (Figure 6, lanes 7 to 9). The individual strands of the protein-free RC DNA were analyzed by using strand-specific riboprobes spanning HBV nucleotide coordinates 828 to 1577. Restriction enzyme digestions were performed to map any discontinuities within the protein-free RC DNA. Examination of the plus strand of the protein-free RC DNA with AccI revealed that this digestion produced the 3,182-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from a CCC HBV DNA molecule (Fig. 6A, lane 4). In addition, a 776-nucleotide single-stranded fragment derived from the RC HBV DNA possessing a nick at nucleotide coordinate 1603 was observed (Fig. 6A, lane 4). The nick at nucleotide coordinate 1603 corresponds to the position of the plus-strand nick present in mature virion genomic DNA (27). Examination of the plus strand of the protein-free RC DNA with EcoRI revealed that this digestion produced the 3,182-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from a CCC HBV DNA molecule (Fig. 6A, lane 5). In addition, a 1,603-nucleotide single-stranded fragment derived from the RC HBV DNA possessing a nick at nucleotide coordinate 1603 was observed, confirming the location of the nick derived from the AccI digestion (Fig. 6A, lane 5). The AccI-plus-EcoRI double digestion confirmed the structure of the plus strand of the protein-free RC DNA. The 2,355-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from a CCC HBV DNA molecule digested with AccI and EcoRI was observed, along with the 776-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from the RC DNA with a nick at nucleotide coordinate 1603 (Fig. 6A, lane 6). This analysis demonstrated that approximately 20% of the plus strands of the protein-free RC DNA were contiguous from nucleotide coordinates 828 to 3182, and therefore the nick at nucleotide coordinate 1603 had been ligated in these HBV DNA molecules.

FIG. 6.

Southern filter hybridization analysis of single-stranded DNA generated from protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates in livers of HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice. DNA was digested with the indicated restriction enzymes prior to gel electrophoresis. Single-stranded protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates were initially separated by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis. Total DNA isolated from the brain of an HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mouse and the liver of an HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mouse were used as controls to indicate positions of the HBV transgene fragments. Sizes of the protein-free HBV replication intermediate fragments are indicated in nucleotides. The riboprobes used (C) spanned the HBV ayw genomic sequence from nucleotide coordinates 828 to 1577 and hybridized to HBV short (S) (or plus-strand) (A) and long (L) (or minus-strand) (B) DNA. HNF1 genotype +/−, HNF1α heterozygous mouse; HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse. (C) Nucleotide coordinates (in parentheses) of restriction sites used in this analysis and locations of the nicks in the plus and minus strands of the HBV DNA normally associated with the virus particle (27). Sizes of the single-stranded DNA fragments generated by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis of the restriction enzyme digested viral DNA are indicated.

The structure of the minus strand of the protein-free RC DNA was also examined (Fig. 6B). Examination of the minus strand of the protein-free RC DNA with AccI revealed that this digestion produced the 3,182-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from a CCC HBV DNA molecule. In addition, a 1,001-nucleotide single-stranded fragment derived from the RC HBV DNA possessing a nick at nucleotide coordinate 1828 was observed (Fig. 6B, lane 4). The nick at nucleotide coordinate 1828 corresponds to the position of the minus-strand nick present in mature virion genomic DNA (27). Examination of the minus strand of the protein-free RC DNA with EcoRI revealed that this digestion produced the 3,182-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from a CCC HBV DNA molecule (Fig. 6B, lane 5). In addition, a 1,828-nucleotide single-stranded fragment derived from the RC HBV DNA possessing a nick at nucleotide coordinate 1828 was observed, confirming the location of the nick derived from the AccI digestion (Fig. 6B, lane 5). The AccI-plus-EcoRI double digestion confirmed the structure of the minus strands of the protein-free RC DNA. The 2,355-nucleotide single-stranded fragment expected from a CCC HBV DNA molecule was observed, and the 1,001-single-stranded nucleotide fragment expected from the RC DNA with a nick at nucleotide coordinate 1828 was also detected (Fig. 6B, lane 6). This analysis demonstrated that approximately 10% of the minus strands of the protein-free RC DNA were contiguous from nucleotide coordinates 828 to 3182, and therefore the nick at nucleotide coordinate 1828 had been ligated in these HBV DNA molecules. From this analysis, it appears that 80 to 90% of the protein-free RC DNA molecules possess a nick at the same location as found in virion DNA, and 10 to 20% of the 3,182-nucleotide HBV DNA is in the form of CCC molecules.

It was of interest to determine the cellular localization of the nicked protein-free RC DNA molecules and the CCC DNA molecules. Alkaline gel electrophoresis and DNA filter hybridization analysis was performed on total brain DNA and protein-free liver DNA from HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 7). The individual strands of the HBV DNA were analyzed by using strand-specific riboprobes spanning HBV nucleotide coordinates 828 to 1577. As expected, the protein-free RC DNA yielded the 1,603- and 3,182-nucleotide plus-strand HBV DNA fragments when digested with EcoRI (Fig. 7A, lane 2). Remarkably, the 3,182-nucleotide HBV fragment localized to the nuclear fraction and the 1,603-nucleotide fragment localized to the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 and 4). The protein-free RC DNA yielded 1,828- and 3,182-nucleotide minus-strand HBV DNA fragments when digested with EcoRI (Fig. 7B, lane 2). The 3,182-nucleotide minus-strand HBV fragment localized to the nuclear fraction, whereas the 1,828-nucleotide fragment localized to the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 and 4). These results indicate that the protein-free RC HBV DNA possessing nicks at nucleotide coordinate 1603 on the plus strand and 1828 on the minus strand are located in the cytoplasm whereas the CCC HBV DNA is located almost exclusively in the nucleus of the hepatocyte.

FIG. 7.

Southern filter hybridization analysis of single-stranded DNA generated from the protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates in livers of HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice. DNA was digested with EcoRI prior to gel electrophoresis. Single-stranded protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates were initially separated by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis. Total DNA isolated from the brain of an HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mouse was used as a control to indicate positions of the HBV transgene fragments. Sizes of the protein-free HBV replication intermediate fragments are indicated in nucleotides. The riboprobes used (C) spanned the HBV ayw genomic sequence from nucleotide coordinates 828 to 1577 and hybridized to HBV short (S) (or plus-strand) (A) and long (L) (or minus-strand) (B) DNA. HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse; lanes T, total protein-free DNA; lanes N, nuclear protein-free DNA; lanes C, cytoplasmic protein-free DNA. (C) Nucleotide coordinates (in parentheses) of restriction sites used in this analysis and locations of the nicks in the plus and minus strands of the HBV DNA normally associated with the virus particle (27). Sizes of the single-stranded DNA fragments generated by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis of the restriction enzyme digested viral DNA are indicated.

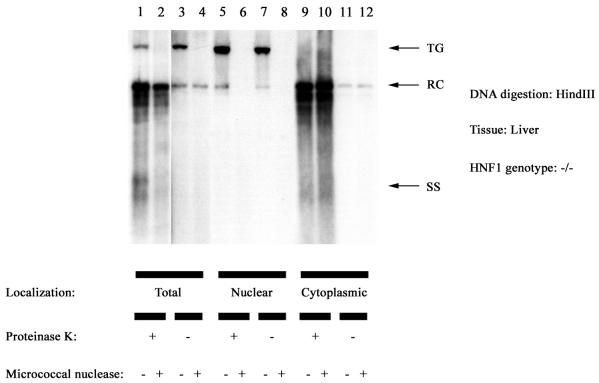

The presence of CCC HBV DNA in the nucleus of the cell is consistent with the cycling of viral genomic DNA from mature cytoplasmic nucleocapsids into the nucleus. In the nucleus, the nicked HBV DNA presumably must be released from the nucleocapsid prior to its conversion into CCC DNA by the viral polymerase and various nuclear enzymatic activities such as DNA ligase. This possibility predicts that the nuclear CCC HBV DNA is accessible to various enzymes. This was examined by digesting nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions prepared from the livers of HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice with micrococcal nuclease (Fig. 8). The mouse chromosomal DNA containing the HBV transgene was degraded by this treatment, indicating the accessibility of this DNA to micrococcal nuclease digestion (Fig. 8, lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8). The viral replication intermediates isolated from total liver were essentially resistant to micrococcal nuclease digestion (Fig. 8, lanes 1 to 4). This indicates that the majority of the viral replication intermediates in the liver of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice are present in a micrococcal nuclease-resistant compartment, presumably the nucleocapsid. In contrast, essentially all of the viral replication intermediates within the nuclei of the hepatocytes were both protein free and susceptible to micrococcal nuclease digestion (Fig. 8, lanes 5 to 8). This suggests that the nuclear protein-free CCC DNA is not located within the viral nucleocapsid and may be organized similarly to chromosomal genomic DNA, based on its susceptibility to degradation by micrococcal nuclease. Interestingly, all of the cytoplasmic viral replication intermediates including the protein-free RC HBV DNA are resistant to micrococcal nuclease digestion (Fig. 8, lane 9 to 12). This indicates that the viral replication intermediates that are covalently attached to the terminal protein are located within nucleocapsids as expected. However, the presence of the protein-free RC HBV DNA in a micrococcal nuclease-resistant compartment within the cytoplasm suggests that this replication intermediate may also be located within viral nucleocapsids. This would be surprising, as it is difficult to understand how the terminal protein can be removed from viral DNA while it is still located within the viral nucleocapsid. However, this possibility is supported by the observation that the cytoplasmic protein-free RC HBV DNA-containing complexes colocalizes in a cesium chloride density gradient with the capsids containing viral DNA that has retained the covalently attached protein (Raney et al., unpublished data).

FIG. 8.

DNA (Southern) filter hybridization analysis of total and protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates in the livers of HNF1α-null (−/−) HBV transgenic mice. Total HBV DNA replication intermediates (+ proteinase K) were compared with the protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates (− proteinase K) present in the whole liver (Total) and the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. DNA was isolated with (+) or without (−) micrococcal nuclease digestion. The HBV transgene (TG) was used as an internal control for quantitation of the HBV replication intermediates. The probe used was HBV ayw genomic DNA. RC, HBV relaxed circular replication intermediates; SS, HBV single-stranded replication intermediates.

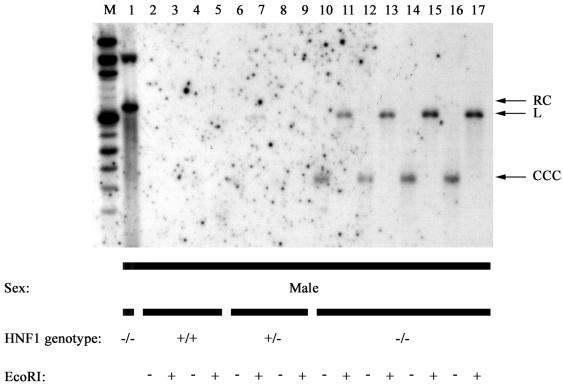

Analysis of the individual single strands of the protein-free HBV DNA replication intermediates demonstrated that CCC plus and minus strands exist in the hepatocyte nuclei of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 7). To determine if nuclear double-stranded CCC HBV DNA is present in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice, viral replication intermediates were isolated from mouse liver nuclei by a procedure designed to recover CCC HBV DNA selectively (Fig. 9). This approach directly demonstrated the presence of double-stranded CCC HBV DNA in the hepatocyte nuclei of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 9, lanes 10 to 17). The supercoiled double-stranded CCC HBV DNA migrates as expected at a position equivalent to linear DNA of approximately 1.8 -kbp (15) (Fig. 9, lanes 10, 12, 14, and 16). Digestion with EcoRI converts the CCC HBV DNA into a linear 3.2-kbp DNA fragment (Fig. 9, lanes 11, 13, 15, and 17) that migrates slightly faster than RC HBV DNA (Fig. 9, lane 1). Double-stranded CCC HBV DNA is marginally detectable in some HNF1α-expressing mice (Fig. 9, lanes 2 to 9), suggesting that very low levels of CCC HBV DNA are probably also present in HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice. However, it is apparent that the relative levels of CCC HBV DNA in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice compared with HNF1α-expressing HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 9) are much greater than the relative levels of total replication intermediates in these mice (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The failure to detect double-stranded CCC HBV DNA in the total protein-free HBV replication intermediates isolated from HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice reflects its limited abundance (Fig. 5). This is due, in part, to the conversion of CCC HBV DNA to RC HBV DNA by the introduction of a single-stranded nick (Fig. 5 and 6) either in vivo or during the isolation procedure. It appears unlikely that the conversion of CCC to RC HBV DNA occurs during the isolation of the total protein-free HBV replication intermediates, as CCC duck hepatitis B virus DNA was readily detectable in infected duck liver using the same method of replication intermediate isolation (Raney et al., unpublished data).

FIG. 9.

DNA (Southern) filter hybridization analysis of nuclear CCC HBV DNA replication intermediates in livers of HBV transgenic mice. Groups of two or four male mice of each genotype were analyzed. Total protein-free (− proteinase K) HBV DNA replication intermediates were digested with HindIII (lane 1) and compared with nuclear CCC HBV DNA replication intermediates isolated by the alkaline lysis method (lanes 2 to 17). Approximately five times more cell equivalents were loaded in lanes 2 to 17 compared with lane 1. Nuclear CCC HBV DNA replication intermediates from each mouse were undigested (−) or digested with EcoRI (+) prior to agarose gel electrophoresis. Replication intermediates are readily detectable in HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (lanes 10 to 17). The probe used was HBV ayw genomic DNA. M, DNA size markers; RC, HBV relaxed circular replication intermediates; L, linear HBV DNA; CCC, covalently closed circular HBV DNA; HNF1 genotype +/+, HNF1α wild-type mouse; HNF1 genotype +/−, HNF1α heterozygous mouse; HNF1 genotype −/−, HNF1α-null mouse.

DISCUSSION

One of the parameters restricting HBV replication to hepatocytes is the requirement for liver-enriched transcription factors to activate transcription of the viral genome (22, 29). HNF1 is a liver-enriched transcription factor that has been shown to regulate the level of transcription from the large surface antigen promoter in cell culture (18, 19, 31). In this study, the effect of HNF1α on viral transcription and replication in vivo was investigated using an HBV transgenic mouse model (11). This was achieved by characterizing the viral transcripts and replication intermediates in the livers of HBV transgenic mice expressing HNF1α- and HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice lacking HNF1α (17).

Comparison of the levels of HBV transcripts in HBV transgenic mice expressing HNF1α and HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 1 to 3) failed to demonstrate that HNF1α had a major effect on the steady-state level of any of the HBV transcripts. This was surprising, as it was anticipated, based on the cell culture analysis, that the level of the 2.4-kb HBV transcript that is transcribed from the large surface antigen promoter would be significantly reduced in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice. This implies that either HNF1α does not greatly modulate HBV transcription in vivo or some mechanism such as the increased level of HNF1β in the HNF1α-null mice compensates for the loss of the HNF1α transcription factor (17).

The absence of any measurable change in the viral transcripts was associated with a modest increase in viral DNA replication intermediates in livers of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice compared with HBV transgenic mice expressing HNF1α. This is a surprising observation and suggests that either a very small change in the levels of HBV RNAs can result in larger alterations in viral replication intermediates or the absence of HNF1α alters the physiological status of the hepatocyte in a manner that favors viral replication. It is possible that the level of the 2.4-kb HBV transcript, and consequently the large surface antigen polypeptide, is subtly reduced in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice. This might lead to an accumulation of intracellular viral replication intermediates and a decrease in circulating virions if the large surface antigen polypeptide is limiting for viral biosynthesis. The failure to detect circulating virions by filter hybridization analysis (Raney et al., unpublished data), presumably due to the spontaneous production of antibodies against the surface antigen polypeptides, and the failure to detect intracellular HBsAg by immunohistochemical analysis in HNF1α-expressing and HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice makes this possibility difficult to examine experimentally. However, the relative levels of the intracellular single-stranded and RC replication intermediates are similar in the HNF1α-expressing and HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Fig. 1). This suggests that mature core particles containing RC DNA are not accumulating in the hepatocytes of the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice due to limiting synthesis of the large surface antigen polypeptide.

The observations with the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice are similar to the results obtained when HBV transgenic mice are treated with peroxisome proliferators (10). In both cases, HBV replication increased whereas the viral transcripts were essentially unaltered. This suggests that a common mechanism may be responsible for both these observations. The pattern of HBcAg immunohistochemical staining observed in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice supports this suggestion. In HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice and in HBV transgenic mice treated with peroxisome proliferators (10), the majority of hepatocytes display both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining. This contrasts with the pattern of HBcAg immunohistochemical staining observed in untreated HBV transgenic mice, where nuclear and cytoplasmic staining is limited to the hepatocytes located in the central vein region and the hepatocytes further from the central vein primarily display nuclear staining. These results suggest that the physiological alteration resulting from the absence of HNF1α and the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) may converge at a common pathway that mediates the observed increase in HBV replication. However, the absence of HNF1α does not directly activate PPARα as induction of the PPARα-responsive cytochrome P450 4A1 transcript is not observed in the HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice (Raney et al., unpublished data).

The increase in viral replication caused by the absence of HNF1α in the HBV transgenic mice is associated with the appearance of protein-free RC HBV DNA (Fig. 5). Protein-free RC HBV DNA is also observed in HBV transgenic mice treated with peroxisome proliferators (Raney et al., unpublished data), which suggests this replication intermediate may be associated with higher levels of viral replication. The detection of protein-free RC HBV DNA is not due simply to increased replication, as a greater than 15-fold increase in protein-free RC HBV DNA is observed for the 2- to 4-fold increase in total viral replication intermediates (Fig. 1 and 5). The protein-free RC HBV DNA present in the cytoplasm of the heptocytes has a structure that is indistinguishable from virion DNA except it lacks the covalently bound terminal protein (Fig. 6 to 8). The cytoplasmic protein-free RC HBV DNA is also resistant to micrococcal nuclease digestion, and this suggests it may be located within the viral nucleocapsid. Cesium chloride density gradient analysis supports this suggestion (Raney et al., unpublished data). If this is the case, it is difficult to understand the mechanism by which the terminal protein is removed from the 5′ end of the HBV minus strand. Alternatively, the cytoplasmic protein-free RC HBV DNA might be in an alternative complex that is resistant to micrococcal nuclease digestion but permits removal of the terminal protein. This complex might be involved in the process of translocating the viral genome from the nucleocapsid in the cytoplasm into the nucleus.

In the nucleus of HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice, the viral genome is present as CCC DNA (Fig. 6, 7, and 9). This leads to the speculation that the protein-free RC HBV DNA present in the cytoplasm might be translocated into the nucleus, where the nicks and gaps in the viral genome are repaired to generate the CCC HBV DNA. Although alkaline gel electrophoresis clearly demonstrates that CCC HBV DNA of both plus and minus strands is present (Fig. 6 and 7), supercoiled HBV genomic DNA was not observed in neutral gel electrophoresis of total mouse liver DNA (Fig. 5). The explanation for this observation is unclear, but it suggests the majority of the double-stranded CCC HBV DNA was converted to double-stranded protein-free RC HBV DNA form possessing a random nick on one strand. The selective isolation of double-stranded CCC HBV DNA (Fig. 9) clearly demonstrates that HNF1α-null HBV transgenic mice have nuclear supercoiled CCC HBV DNA, as predicted from analysis of the structures of the individual plus and minus strands (Fig. 6 and 7). These observations represent the first demonstration that the viral genome can cycle into the nucleus from the cytoplasm in this transgenic mouse model.

This analysis demonstrates that HNF1α is an important in vivo regulator of viral replication but not viral transcription in the HBV transgenic mouse. Consequently, it appears possible that indirect effects on cellular gene expression rather than direct effects on viral gene expression can explain the HNF1α-mediated alterations in HBV replication. Regardless of the mechanism responsible for the increase in replication, it is associated with the identification of two novel replication intermediates that are not readily detectable in the HBV transgenic mouse under normal physiological conditions. The presence of protein-free RC HBV DNA in the cytoplasm and CCC HBV DNA in the nucleus indicates that cycling of viral replication intermediates into the nucleus occurs in this in vivo model system. If the protein-free RC HBV DNA is a precursor of the nuclear CCC HBV DNA, these results suggest that the first event in translocating viral DNA to the nucleus is the removal of the terminal protein from the 5′ end of the minus strand of the HBV DNA in the cytoplasm. This intermediate is then translocated into the nucleus and converted to CCC DNA. The observation that nuclear CCC HBV DNA can be generated in this system suggests that it might be possible to examine the transcriptional properties of this molecule in vivo. This is important as it is generally believed nuclear CCC HBV DNA represents the template for viral transcription in natural infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Frank Chisari for providing the HBV transgenic mice and for support and encouragement throughout this study and Stefan Wieland for many helpful discussions. We are especially grateful to Jesse Summers for assistance and advice regarding isolation and characterization of CCC HBV DNA. We are grateful to Margie Chadwell for preparation and staining of tissue sections.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI30070 and AI40696 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publication no. 13419-CB from The Scripps Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker L F, Maynard J E, Purcell R H, Hoofnagle J H, Berquist K R, London W T. Viral hepatitis, type B, in experimental animals. Am J M Sci. 1975;270:189–194. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197507000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruss V, Ganem D. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1059–1063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruss V, Thomssen R. Mapping a region of the large envelope protein required for hepatitis B virion maturation. J Virol. 1994;68:1643–1650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1643-1650.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudov K P, Perry R P. The gene family encoding the mouse ribosomal protein L32 contains a uniquely expressed intron-containing gene and an unmutated processed gene. Cell. 1984;37:457–468. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galibert F, Mandart E, Fitoussi F, Tiollais P, Charnay P. Nucleotide sequence of the hepatitis B virus genome (subtype ayw) cloned in E. coli. Nature. 1979;281:646–650. doi: 10.1038/281646a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganem D, Varmus H E. The molecular biology of the hepatitis B viruses. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:651–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerelsaikhan T, Tavis J E, Bruss V. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid envelopment does not occur without genomic DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1996;70:4269–4274. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4269-4274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerlich W H, Robinson W S. Hepatitis B virus contains protein attached to the 5′ terminus of its complete DNA strand. Cell. 1980;21:801–809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidotti L G, Eggers C M, Raney A K, Chi S Y, Peters J M, Gonzalez F J, McLachlan A. In vivo regulation of hepatitis B virus replication by peroxisome proliferators. J Virol. 1999;73:10377–10386. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10377-10386.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidotti L G, Matzke B, Schaller H, Chisari F V. High-level hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1995;69:6158–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6158-6169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamimura T, Yoshikawa A, Ichida F, Sasaki H. Electron microscopic studies of Dane particles in hepatocytes with special reference to intracellular development of Dane particles and their relation with HBeAg in serum. Hepatology. 1981;1:392–397. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee Y H, Sauer B, Gonzalez F J. Laron dwarfism and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in the Hnf-1α knockout mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3059–3068. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenhoff R J, Summers J. Coordinate regulation of replication and virus assembly by the large envelope protein of an avian hepadnavirus. J Virol. 1994;68:4565–4571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4565-4571.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller R H, Robinson W S. Hepatitis B virus DNA forms in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of infected human liver. Virology. 1984;137:390–399. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ou J-H, Bao H, Shih C, Tahara S M. Preferred translation of human hepatitis B virus polymerase from core protein- but not from precore protein-specific transcript. J Virol. 1990;64:4578–4581. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4578-4581.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pontoglio M, Barra J, Hadchouel M, Doyen A, Kress C, Bach J P, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell. 1996;84:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raney A K, Easton A J, McLachlan A. Characterization of the minimal elements of the hepatitis B virus large surface antigen promoter. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2671–2679. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raney A K, Easton A J, Milich D R, McLachlan A. Promoter-specific transactivation of hepatitis B virus transcription by a glutamine- and proline-rich domain of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1. J Virol. 1991;65:5774–5781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5774-5781.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raney A K, McLachlan A. The biology of hepatitis B virus. In: McLachlan A, editor. Molecular biology of the hepatitis B virus. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaller H, Fischer M. Transcriptional control of hepadnavirus gene expression. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1991;168:21–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76015-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schibler U, Hagenbüchle O, Wellauer P K, Pittet A C. Two promoters of different strengths control the transcription of the mouse alpha-amylase gene Amy-1a in the parotid gland and the liver. Cell. 1983;33:501–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Summers J, Smith P M, Horwich A L. Hepadnavirus envelope proteins regulate covalently closed circular DNA amplification. J Virol. 1990;64:2819–2824. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2819-2824.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tso J Y, Sun X-H, Kao T, Reece K S, Wu R. Isolation and characterization of rat and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNAs: genomic complexity and molecular evolution of the gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2485–2502. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuttleman J S, Pourcel C, Summers J. Formation of the pool of covalently closed circular viral DNA in hepadnavirus-infected cells. Cell. 1986;47:451–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Will H, Reiser W, Weimer T, Pfaff E, Buscher M, Sprengle R, Cattaneo R, Schaller H. Replication strategy of human hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 1987;61:904–911. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.3.904-911.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada G, Sakamoto Y, Mizuno M, Nishihara T, Kobayashi T, Takahashi T, Nagashima H. Electron and immunoelectron microscopic study of Dane particle formation in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:348–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yen T S B. Regulation of hepatitis B virus gene expression. Semin Virol. 1993;4:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y Y, Summers J. Low dynamic state of viral competition in a chronic avian hepadnavirus infection. J Virol. 2000;74:5257–5265. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5257-5265.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou D-X, Yen T S B. The ubiquitous transcription factor Oct-1 and the liver-specific factor HNF-1 are both required to activate transcription of a hepatitis B virus promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1353–1359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]