Abstract

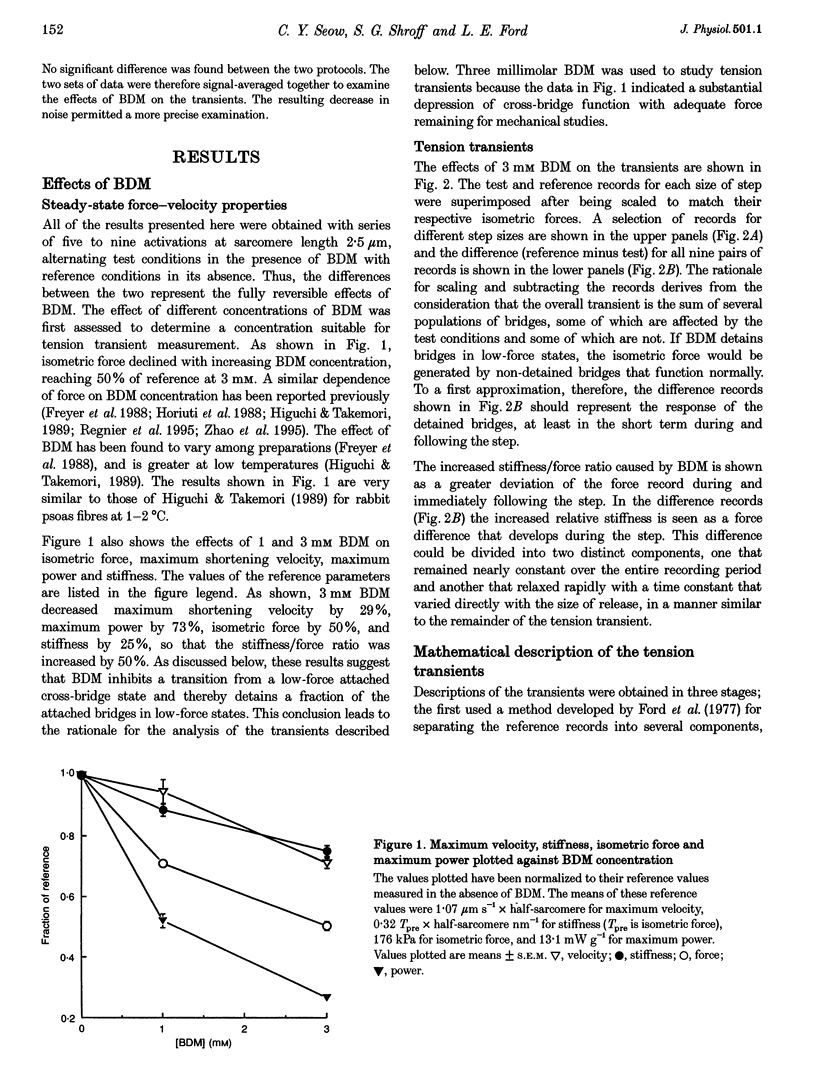

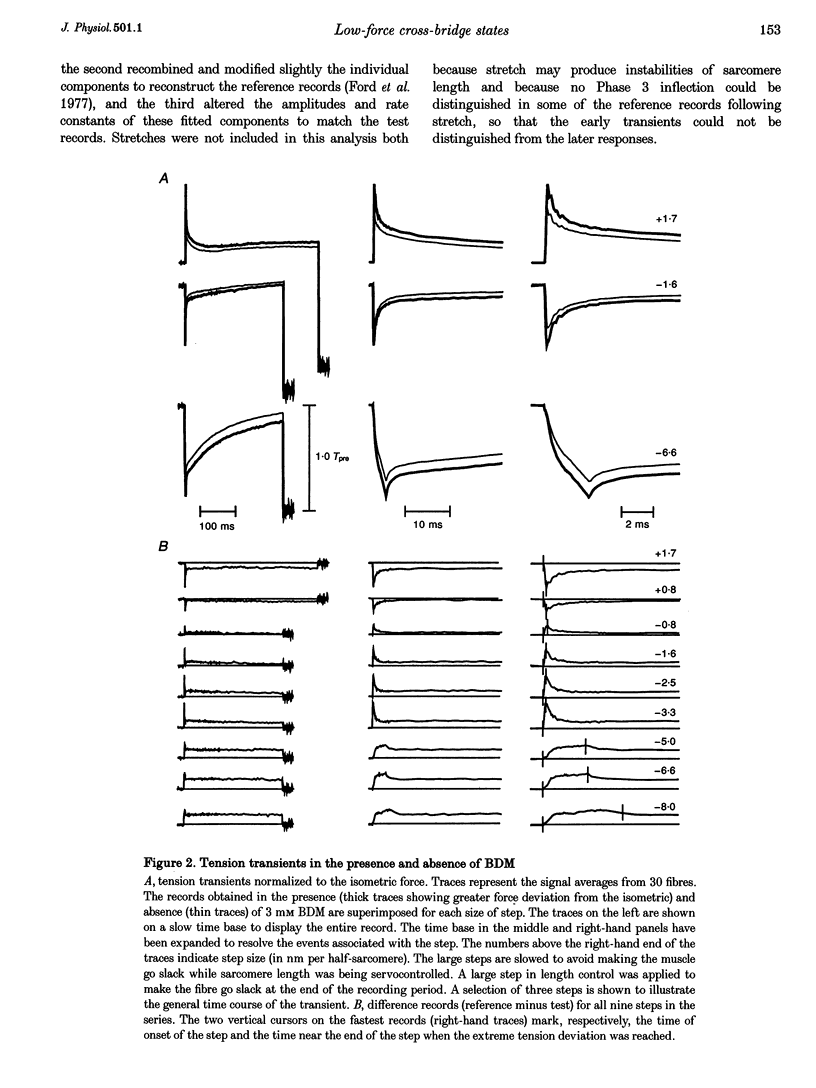

1. To probe the cross-bridge cycle and to learn more about the cardioplegic agent BDM (2,3-butanedione monoxime), its effects on the force-velocity properties and tension transients of skinned rabbit muscle fibres were studied at 1-2 degrees C and pH 7.0. 2. Three millimolar BDM decreased isometric force by 50%, velocity by 29%, maximum power by 73%, and stiffness by 25%, so that the relative stiffness (stiffness/force ratio) increased by 50% compared with reference conditions in the absence of BDM. 3. Tension transients obtained under the reference condition (0 BDM) could be represented by three components whose instantaneous stiffness accounted for the initial (Phase 1) force deviation and whose exponential recoveries caused the rapid, partial (Phase 2) force recovery following the step. The fastest component had non-linear extension-force properties that accounted for about half the isometric stiffness and it recovered fully. The two slower components had linear extension-force properties that together accounted for the other half of the sarcomere stiffness. These components recovered only partially following the step, producing the intermediate (T2) level which the force approached during Phase 2. 4. Matching the force transients obtained under test conditions (3 mM BDM) required three alterations: (1) reducing the amplitude of the two slower components by 50%, in proportion to isometric force, (2) adding a non-relaxing component and (3) decreasing the amplitude of the rapidly recovering component by 12.5% so that its relative amplitude (amplitude/isometric force) was increased by 75%. The non-recovering component and the increase in relative amplitude of the rapid component were responsible for the increase in relative stiffness of the fibres produced by BDM. The rapidly recovering component had the same time constant and step-size-dependent recovery rates as the fastest of the three mono-exponential components isolated from the tension transient response under the reference condition. BDM therefore appeared to augment the fastest component of the tension transient under the reference condition. 5. The results suggest that BDM detains cross-bridges in low-force, attached states. Since these bridges are attached, they contribute to sarcomere stiffness. Since they are detained, relaxation or reversal of their immediate responses is probably due to bridge detachment rather than to their undergoing the power stroke. The observation that a portion of the test response matched the fastest component of the reference response when the amplitude of the fastest component was increased suggests that a part of the normal rapid, transient tension recovery following a release step is due to detachment of low-force bridges moved to negative-force positions by the step.

Full text

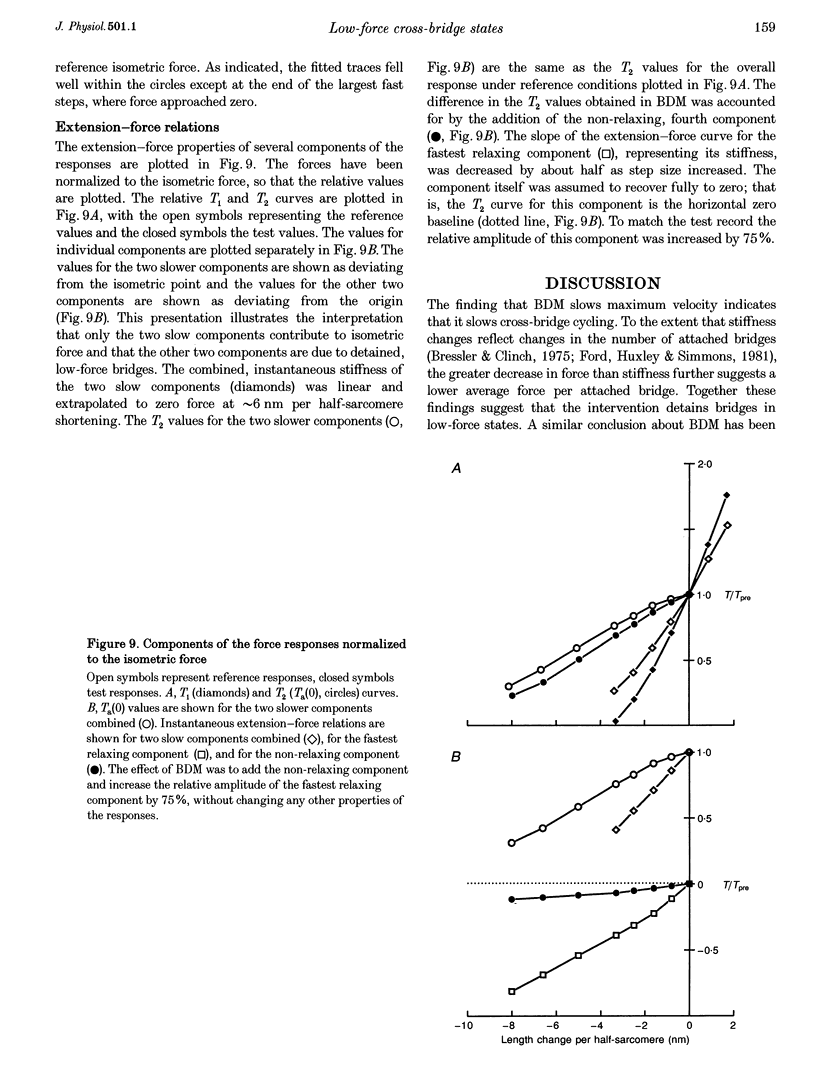

PDF

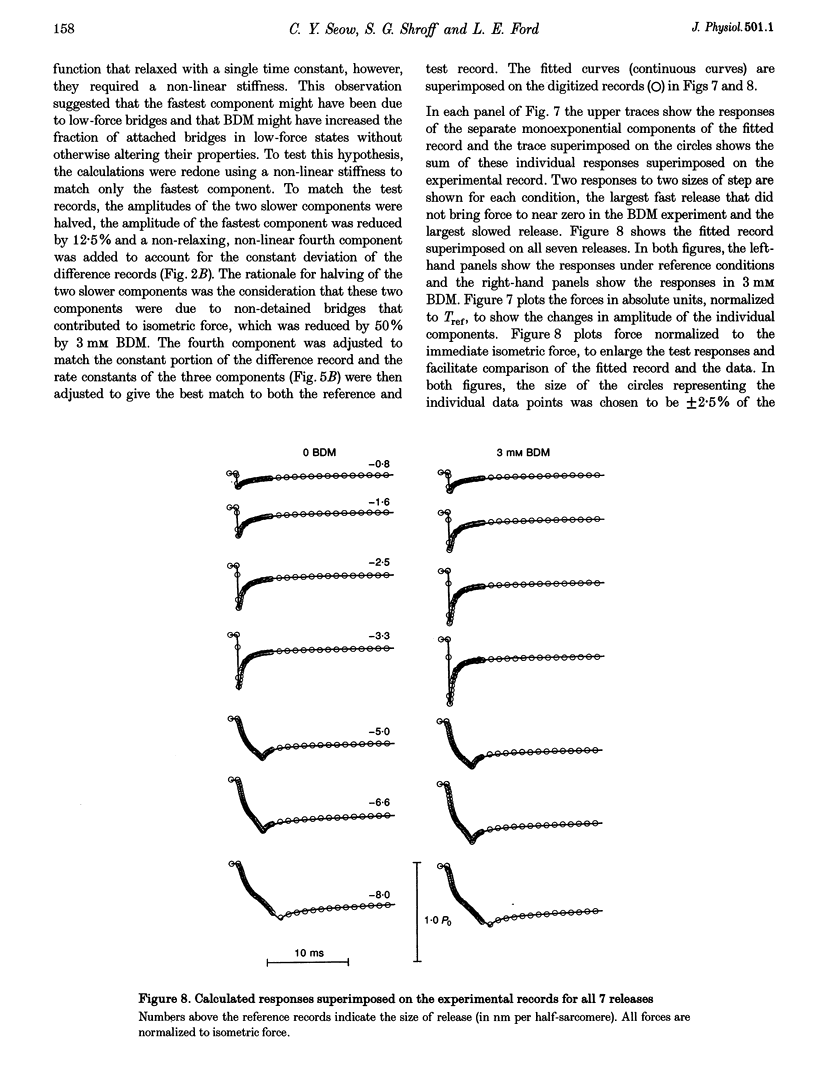

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andrews M. A., Maughan D. W., Nosek T. M., Godt R. E. Ion-specific and general ionic effects on contraction of skinned fast-twitch skeletal muscle from the rabbit. J Gen Physiol. 1991 Dec;98(6):1105–1125. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.6.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni M. A., Cecchi G., Colomo F., Garzella P. Effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on the crossbridge kinetics in frog single muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1992 Oct;13(5):516–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01737994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E. M., Smith G. L., Allen D. G., Alpert N. R. The effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on initial heat, tension, and aequorin light output of ferret papillary muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1990 Apr;416(1-2):219–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00370248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B., Schoenberg M., Chalovich J. M., Greene L. E., Eisenberg E. Evidence for cross-bridge attachment in relaxed muscle at low ionic strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Dec;79(23):7288–7291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Technique for stabilizing the striation pattern in maximally calcium-activated skinned rabbit psoas fibers. Biophys J. 1983 Jan;41(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler B. H., Clinch N. F. Cross bridges as the major source of compliance in contracting skeletal muscle. Nature. 1975 Jul 17;256(5514):221–222. doi: 10.1038/256221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase P. B., Kushmerick M. J. Effects of pH on contraction of rabbit fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1988 Jun;53(6):935–946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y. L., Asayama J., Ford L. E. A sensitive photoelectric force transducer with a resonant frequency of 6 kHz. Am J Physiol. 1982 Nov;243(5):C299–C302. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.243.5.C299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzig J. A., Walker J. W., Trentham D. R., Goldman Y. E. Relaxation of muscle fibers with adenosine 5'-[gamma-thio]triphosphate (ATP[gamma S]) and by laser photolysis of caged ATP[gamma S]: evidence for Ca2+-dependent affinity of rapidly detaching zero-force cross-bridges. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Sep;85(18):6716–6720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDERY H. Effects of diacetyl monoxime on neuromuscular transmission. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1959 Sep;14:317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford L. E., Huxley A. F., Simmons R. M. Tension responses to sudden length change in stimulated frog muscle fibres near slack length. J Physiol. 1977 Jul;269(2):441–515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford L. E., Huxley A. F., Simmons R. M. The relation between stiffness and filament overlap in stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1981 Feb;311:219–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford L. E., Nakagawa K., Desper J., Seow C. Y. Effect of osmotic compression on the force-velocity properties of glycerinated rabbit skeletal muscle cells. J Gen Physiol. 1991 Jan;97(1):73–88. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer M. W., Gage P. W., Neering I. R., Dulhunty A. F., Lamb G. D. Paralysis of skeletal muscle by butanedione monoxime, a chemical phosphatase. Pflugers Arch. 1988 Jan;411(1):76–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00581649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer M. W., Neering I. R., Stephenson D. G. Effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on the contractile activation properties of fast- and slow-twitch rat muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1988 Dec;407:53–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt R. E. Calcium-activated tension of skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Dependence on magnesium adenosine triphosphate concentration. J Gen Physiol. 1974 Jun;63(6):722–739. doi: 10.1085/jgp.63.6.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt R. E., Lindley B. D. Influence of temperature upon contractile activation and isometric force production in mechanically skinned muscle fibers of the frog. J Gen Physiol. 1982 Aug;80(2):279–297. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt R. E., Maughan D. W. On the composition of the cytosol of relaxed skeletal muscle of the frog. Am J Physiol. 1988 May;254(5 Pt 1):C591–C604. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.5.C591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt R. E., Nosek T. M. Changes of intracellular milieu with fatigue or hypoxia depress contraction of skinned rabbit skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1989 May;412:155–180. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Y. E. Measurement of sarcomere shortening in skinned fibers from frog muscle by white light diffraction. Biophys J. 1987 Jul;52(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Y. E., Simmons R. M. The stiffness of frog skinned muscle fibres at altered lateral filament spacing. J Physiol. 1986 Sep;378:175–194. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey J. K., Hajjar R. J., Solaro R. J. Contractile deactivation and uncoupling of crossbridges. Effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on mammalian myocardium. Circ Res. 1991 Nov;69(5):1280–1292. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL A. V. THE EFFECT OF LOAD ON THE HEAT OF SHORTENING OF MUSCLE. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1964 Jan 14;159:297–318. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1964.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUXLEY A. F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann C., Wray J., Travers F., Barman T. Effect of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on myosin and myofibrillar ATPases. An example of an uncompetitive inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1992 Dec 8;31(48):12227–12232. doi: 10.1021/bi00163a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi H., Takemori S. Butanedione monoxime suppresses contraction and ATPase activity of rabbit skeletal muscle. J Biochem. 1989 Apr;105(4):638–643. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuti K., Higuchi H., Umazume Y., Konishi M., Okazaki O., Kurihara S. Mechanism of action of 2, 3-butanedione 2-monoxime on contraction of frog skeletal muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1988 Apr;9(2):156–164. doi: 10.1007/BF01773737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C. S., Maylie J. Multiple actions of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on contractile activation in frog twitch fibres. J Physiol. 1991 Oct;442:527–549. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley A. F. A note suggesting that the cross-bridge attachment during muscle contraction may take place in two stages. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1973 Feb 27;183(1070):83–86. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1973.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley A. F., Simmons R. M. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature. 1971 Oct 22;233(5321):533–538. doi: 10.1038/233533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi V., Piazzesi G. The contractile response during steady lengthening of stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1990 Dec;431:141–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri L. A., Hasenfuss G., Ittleman F., Blanchard E. M., Alpert N. R. Protection of human left ventricular myocardium from cutting injury with 2,3-butanedione monoxime. Circ Res. 1989 Nov;65(5):1441–1449. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayment I., Holden H. M., Whittaker M., Yohn C. B., Lorenz M., Holmes K. C., Milligan R. A. Structure of the actin-myosin complex and its implications for muscle contraction. Science. 1993 Jul 2;261(5117):58–65. doi: 10.1126/science.8316858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnier M., Morris C., Homsher E. Regulation of the cross-bridge transition from a weakly to strongly bound state in skinned rabbit muscle fibers. Am J Physiol. 1995 Dec;269(6 Pt 1):C1532–C1539. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.6.C1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow C. Y., Ford L. E. Contribution of damped passive recoil to the measured shortening velocity of skinned rabbit and sheep muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1992 Jun;13(3):295–307. doi: 10.1007/BF01766457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow C. Y., Ford L. E. High ionic strength and low pH detain activated skinned rabbit skeletal muscle crossbridges in a low force state. J Gen Physiol. 1993 Apr;101(4):487–511. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele D. S., Smith G. L. Effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on sarcoplasmic reticulum of saponin-treated rat cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):H1493–H1500. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.5.H1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins J. R., Reiser J., Fitzpatrick D. F., Bergey J. L. Inotropic actions of diacetyl monoxime in cat ventricular muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980 Feb;212(2):217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Naber N., Cooke R. Muscle cross-bridges bound to actin are disordered in the presence of 2,3-butanedione monoxime. Biophys J. 1995 May;68(5):1980–1990. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80375-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Kawai M. BDM affects nucleotide binding and force generation steps of the cross-bridge cycle in rabbit psoas muscle fibers. Am J Physiol. 1994 Feb;266(2 Pt 1):C437–C447. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.2.C437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]