Abstract

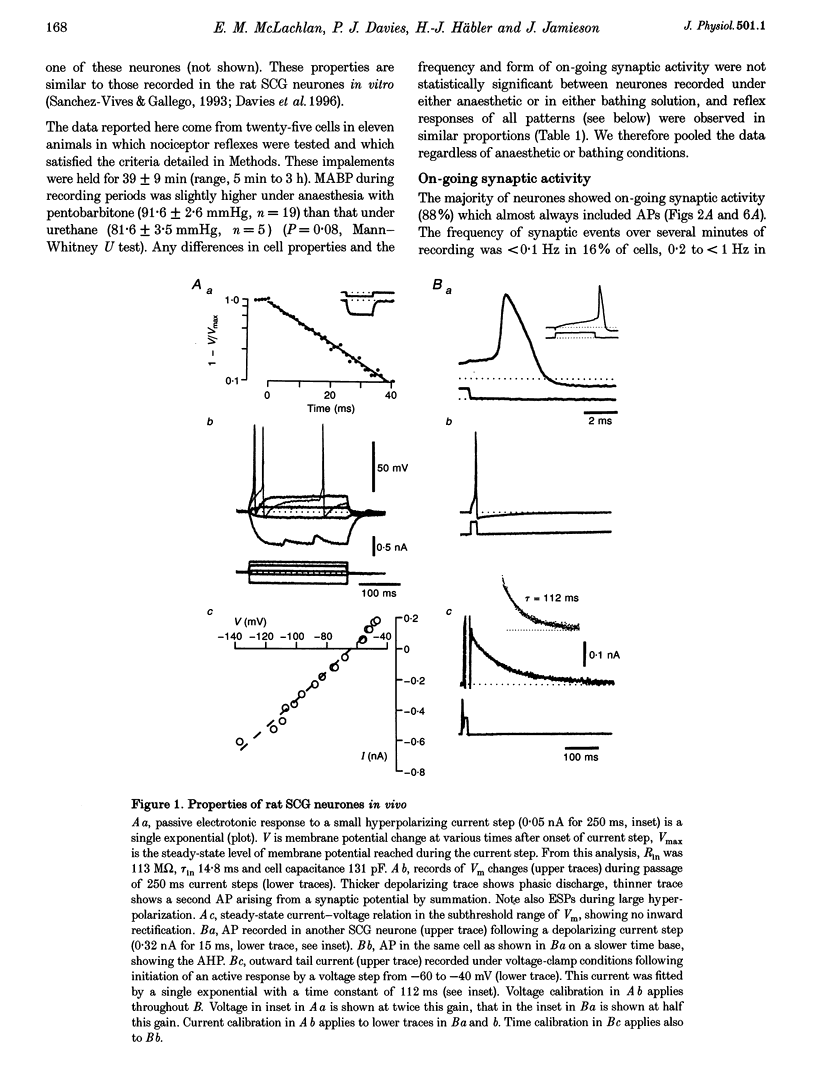

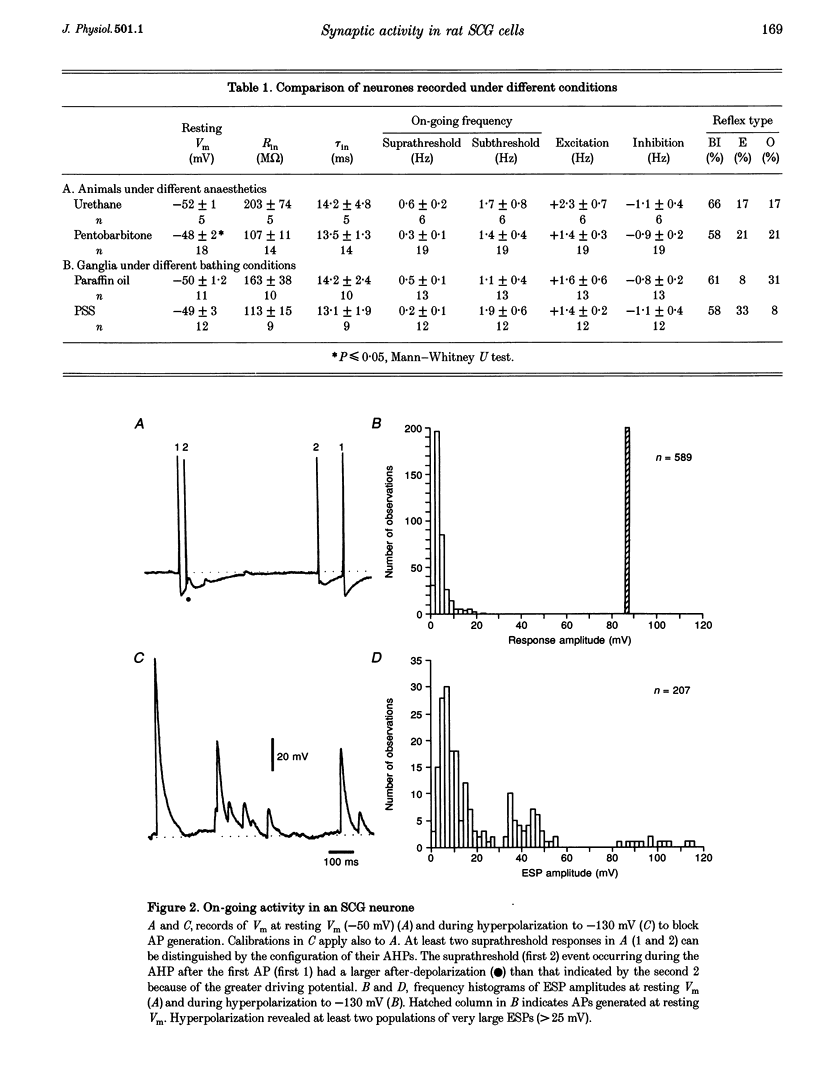

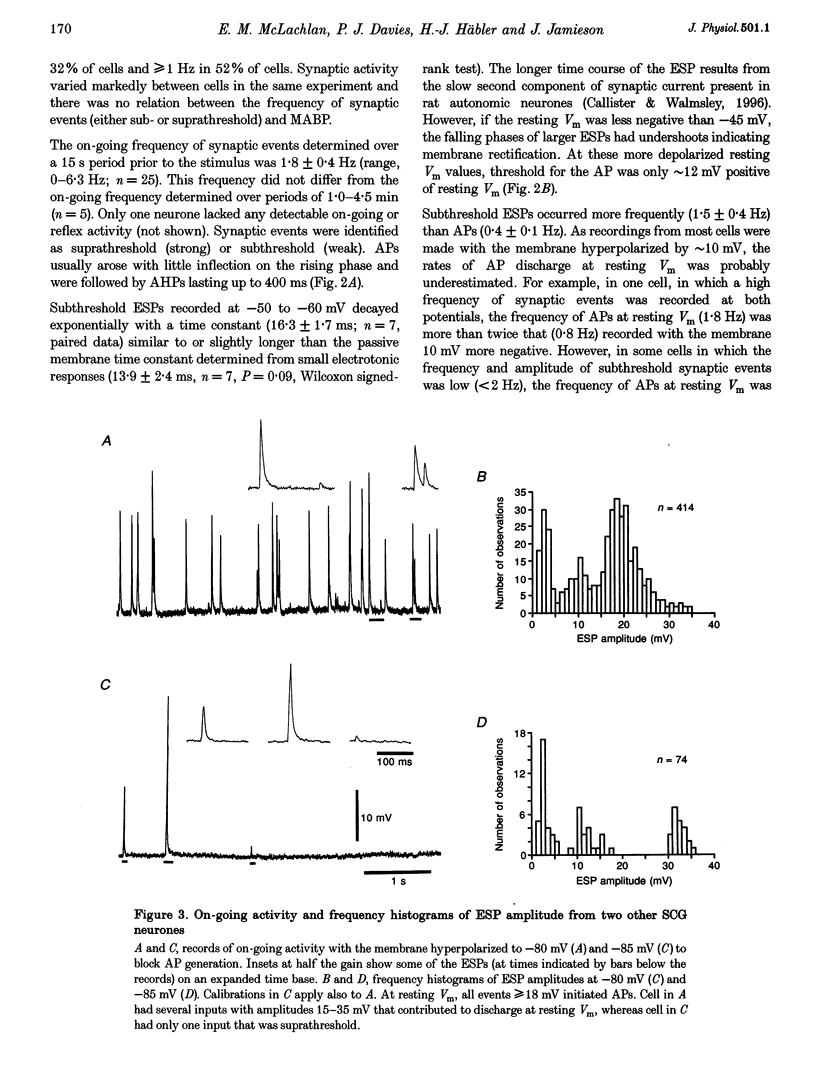

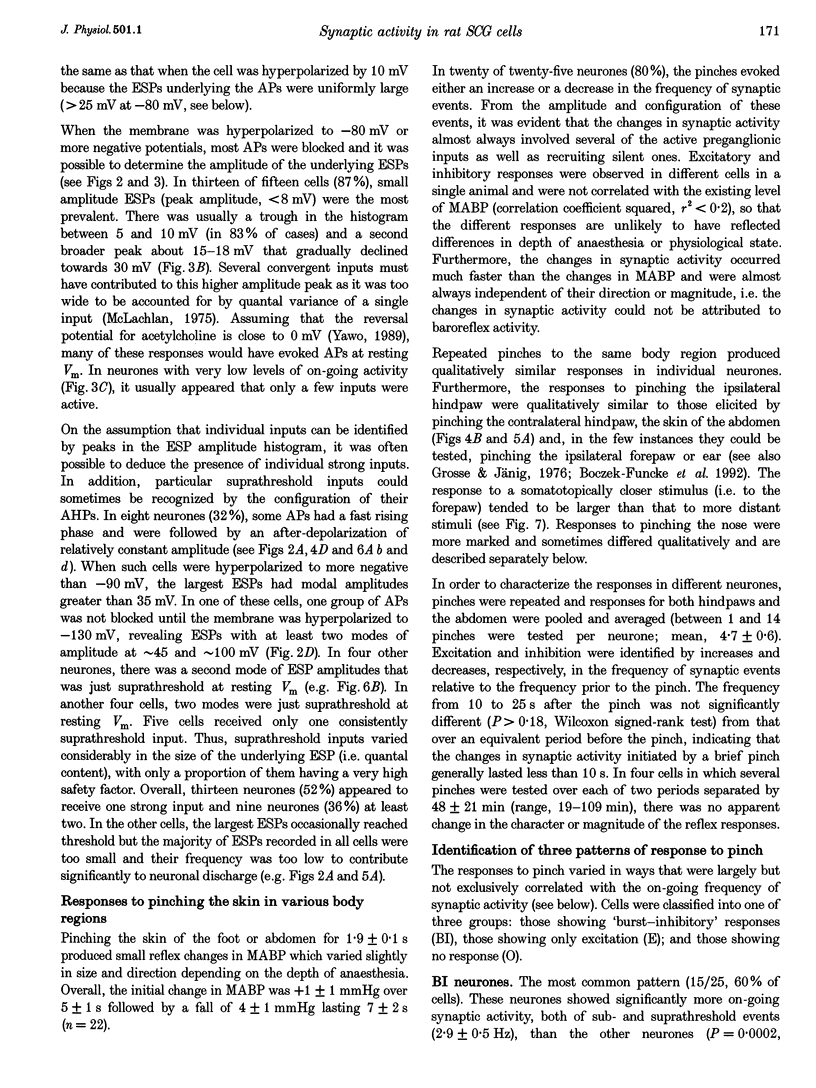

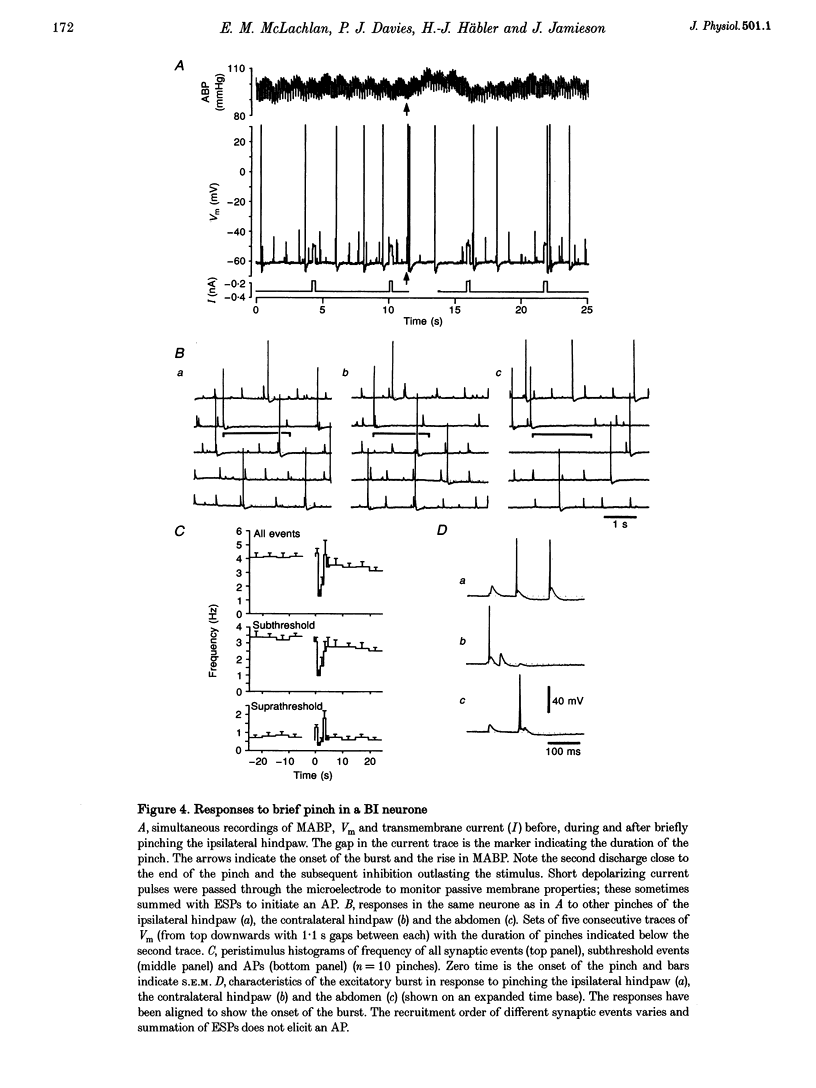

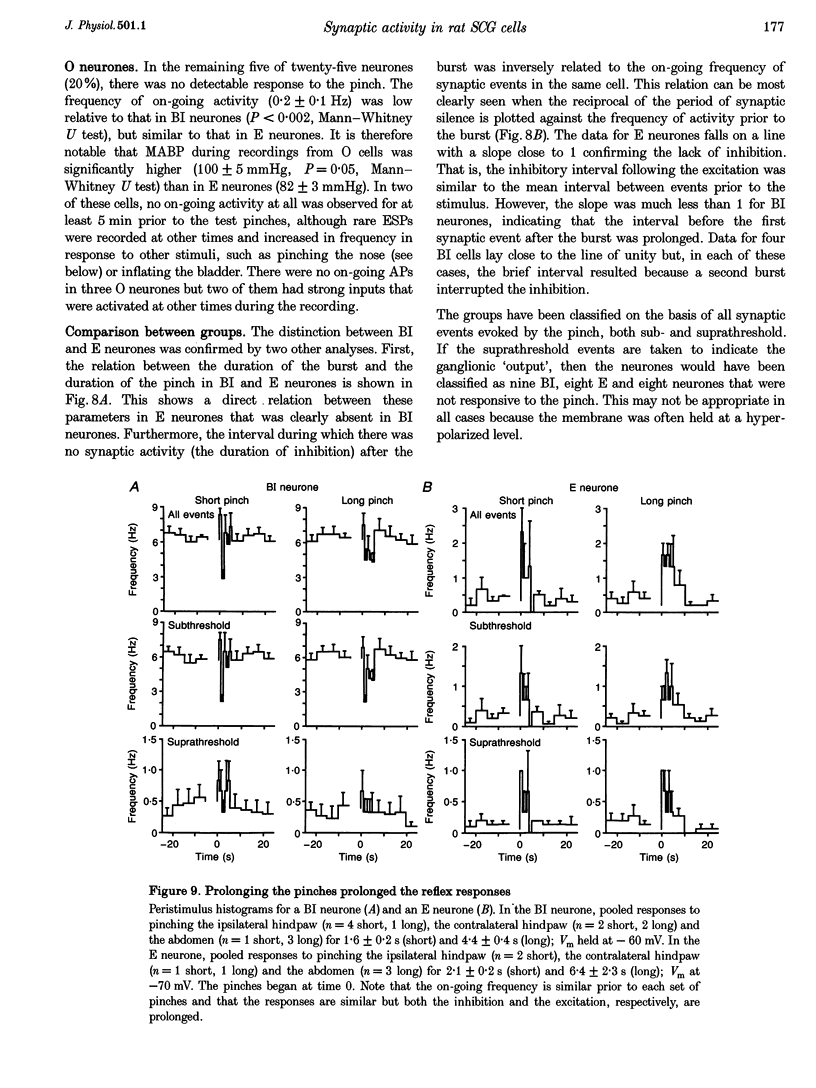

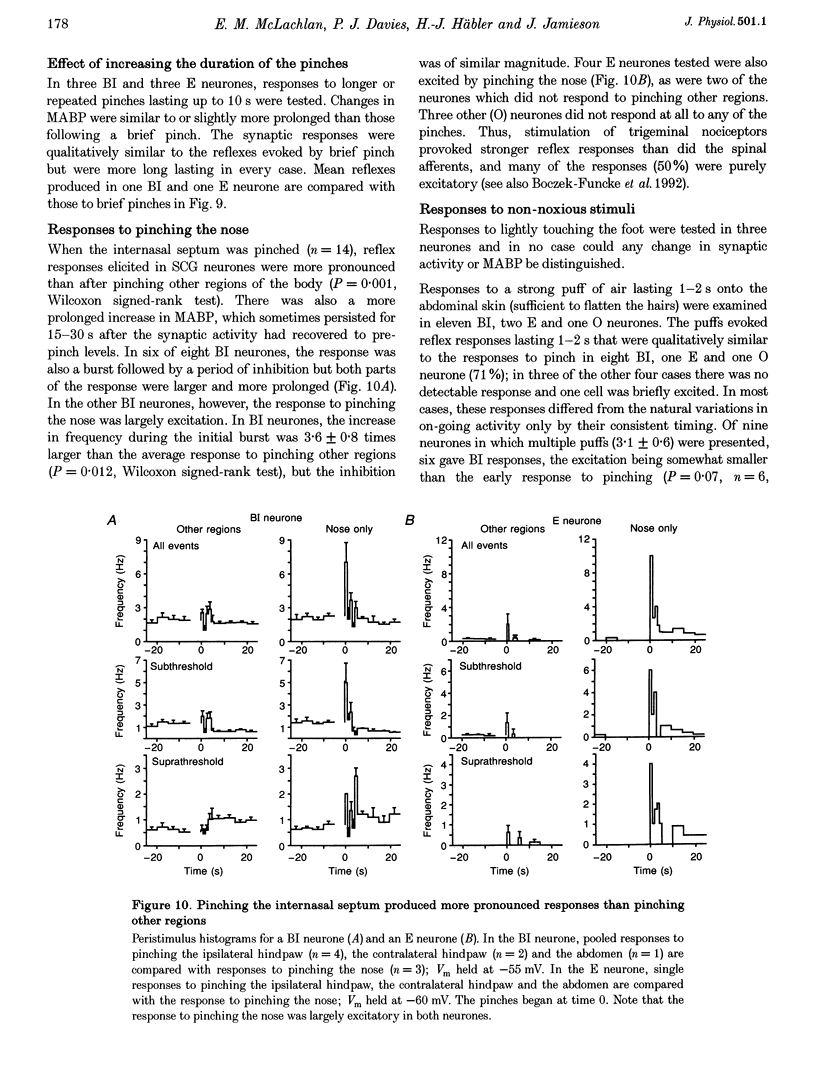

1. Synaptic events evoked by brief noxious cutaneous stimuli were recorded in sympathetic neurones in the superior cervical ganglion of anaesthetized rats. 2. On-going excitatory synaptic potentials (ESPs) and/or action potentials (APs) were recorded in 69% of neurones at mean frequencies that varied from 0.01 to 6.3 Hz in different cells. From histograms of ESP amplitude during membrane hyperpolarization, it appears that most cells received one (52%), or two or more (36%), suprathreshold inputs and several subthreshold inputs with overlapping amplitudes. 3. Pinching the skin for 1-3 s evoked either a brief burst of synaptic events (lasting about 300 ms) preceding a few seconds of inhibition (burst-inhibitory (BI) neurones), or simply an excitation (excitatory (E) neurones), or no response (O neurones). In 60% of BI neurones, a second burst occurred after the end of the pinch. 4. BI neurones had a higher frequency of on-going synaptic activity (2.9 +/- 0.5 Hz, n = 15) than E neurones (0.2 +/- 0.1 Hz, n = 5) or O (0.2 +/- 0.1 Hz, n = 5) neurones. Most neurones with two or more suprathreshold inputs were BI neurones. In 20% of neurones (all BI with high rates of synaptic activity), several other inputs had ESPs with amplitudes close to threshold. 5. Subthreshold and suprathreshold inputs responded in the same way in only 45% of neurones, but suprathreshold inputs were excited in 73% of BI and all E neurones. The order of recruitment of different inputs varied from trial to trial. If classification was based only on suprathreshold responses, there were 36% BI, 32% E and 32% O neurones. 6. In the majority of neurones, postganglionic discharge was initiated exclusively by suprathreshold inputs, even during reflex excitation. 7. Qualitatively similar, but smaller, responses were evoked by a puff of air on the abdomen in 71% of cells tested. 8. The data suggest that the natural discharge of SCG neurones is largely determined by the activity of one or two preganglionic inputs with high quantal contents. BI neurones may include vasoconstrictor neurones, whereas the other types include secretomotor, pilomotor and other neurones projecting to targets in the head.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bartsch T., Häbler H. J., Jänig W. Functional properties of postganglionic sympathetic neurones supplying the submandibular gland in the anaesthetized rat. Neurosci Lett. 1996 Aug 23;214(2-3):143–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12910-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boczek-Funcke A., Dembowsky K., Häbler H. J., Jänig W., McAllen R. M., Michaelis M. Classification of preganglionic neurones projecting into the cat cervical sympathetic trunk. J Physiol. 1992;453:319–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callister R. J., Walmsley B. Amplitude and time course of evoked and spontaneous synaptic currents in rat submandibular ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1996 Jan 1;490(Pt 1):149–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell J. F., Clark A. L., McLachlan E. M. Characteristics of phasic and tonic sympathetic ganglion cells of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1986 Mar;372:457–483. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell J. F., McLachlan E. M. Two calcium-activated potassium conductances in a subpopulation of coeliac neurones of guinea-pig and rabbit. J Physiol. 1987 Dec;394:331–349. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney R. A. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 1994 Apr;74(2):323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. J., Ireland D. R., McLachlan E. M. Sources of Ca2+ for different Ca(2+)-activated K+ conductances in neurones of the rat superior cervical ganglion. J Physiol. 1996 Sep 1;495(Pt 2):353–366. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delius W., Hagbarth K. E., Hongell A., Wallin B. G. General characteristics of sympathetic activity in human muscle nerves. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972 Jan;84(1):65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins I. L. Vasomotor, pilomotor and secretomotor neurons distinguished by size and neuropeptide content in superior cervical ganglia of mice. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1991 Jun 15;34(2-3):171–183. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(91)90083-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbey M. P., Numao Y., Spyer K. M. Discharge patterns of cervical sympathetic preganglionic neurones related to central respiratory drive in the rat. J Physiol. 1986 Sep;378:253–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse M., Jänig W. Vasoconstrictor and pilomotor fibres in skin nerves to the cat's tail. Pflugers Arch. 1976 Feb 24;361(3):221–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00587286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst G. D., McLachlan E. M. Post-natal development of ganglia in the lower lumbar sympathetic chain of the rat. J Physiol. 1984 Apr;349:119–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horeyseck G., Jänig W. Reflexes in postganglionic fibres within skin and muscle nerves after mechanical non-noxious stimulation of skin. Exp Brain Res. 1974;20(2):115–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00234006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häbler H. J., Jänig W., Krummel M., Peters O. A. Reflex patterns in postganglionic neurons supplying skin and skeletal muscle of the rat hindlimb. J Neurophysiol. 1994 Nov;72(5):2222–2236. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AYa Pattern of ongoing activity in rat superior cervical ganglion neurons projecting to a specific target. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1991 Jan;32(1):77–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(91)90238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov A., Purves D. Ongoing electrical activity of superior cervical ganglion cells in mammals of different size. J Comp Neurol. 1989 Jun 15;284(3):398–404. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. A., Purves D. Tonic and reflex synaptic activity recorded in ciliary ganglion cells of anaesthetized rabbits. J Physiol. 1983 Jun;339:599–613. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W., McLachlan E. M. Specialized functional pathways are the building blocks of the autonomic nervous system. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1992 Nov;41(1-2):3–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90121-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W., Sato A., Schmidt R. F. Reflexes in postganglionic cutaneous fibres by stimulation of group I to group IV somatic afferents. Pflugers Arch. 1972;331(3):244–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00589131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. I., Coote J. H. Chemical mediators of spinal inhibition of rat sympathetic neurones on stimulation in the nucleus tractus solitarii. J Physiol. 1995 Jul 15;486(Pt 2):483–494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan S. D., Pickering A. E., Gibson I. C., Nolan M. F., Spanswick D. Electrotonic coupling between rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1996 Sep 1;495(Pt 2):491–502. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan E. M. An analysis of the release of acetylcholine from preganglionic nerve terminals. J Physiol. 1975 Feb;245(2):447–466. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolsky E. E., Oranska T. I., Vyskocil F. Non-quantal acetylcholine release in the mouse diaphragm after phrenic nerve crush and during recovery. Exp Physiol. 1996 May;81(3):341–348. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D. Functional and structural changes in mammalian sympathetic neurones following interruption of their axons. J Physiol. 1975 Nov;252(2):429–463. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D., Lichtman J. W. Geometrical differences among homologous neurons in mammals. Science. 1985 Apr 19;228(4697):298–302. doi: 10.1126/science.3983631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D., Rubin E., Snider W. D., Lichtman J. Relation of animal size to convergence, divergence, and neuronal number in peripheral sympathetic pathways. J Neurosci. 1986 Jan;6(1):158–163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-01-00158.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skok V. I., Ivanov A. Y. What is the ongoing activity of sympathetic neurons? J Auton Nerv Syst. 1983 Mar-Apr;7(3-4):263–270. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(83)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M. K., Spyer K. M. Nociceptive inputs into rostral ventrolateral medulla-spinal vasomotor neurones in rats. J Physiol. 1991 May;436:685–700. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vives M. V., Gallego R. Effects of axotomy or target atrophy on membrane properties of rat sympathetic ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1993 Nov;471:801–815. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarchenko L. A., Ivanov AYa, Skok V. I. Organization of the tonically active pathways through the superior cervical ganglion of the rabbit. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1990 Jul;30 (Suppl):S163–S168. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyvodic J. T. Peripheral target regulation of dendritic geometry in the rat superior cervical ganglion. J Neurosci. 1989 Jun;9(6):1997–2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-01997.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin B. G., Fagius J. Peripheral sympathetic neural activity in conscious humans. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:565–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. S., McKinnon D. Modulation of inwardly rectifying currents in rat sympathetic neurones by muscarinic receptors. J Physiol. 1996 Apr 15;492(Pt 2):467–478. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H. Rectification of synaptic and acetylcholine currents in the mouse submandibular ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1989 Oct;417:307–322. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]