Abstract

Vibrio cholerae El Tor require special in vitro culture conditions, consisting of an initial static growth period followed by shift to shaking (AKI conditions), for expression of cholera toxin (CT) and toxin coregulated pili (TCP). ToxT, a regulator whose initial transcription depends on the ToxR regulator, positively modulates expression of CT and TCP. To help understand control of CT and TCP in El Tor vibrios, we monitored ctxAB and ToxR-dependent toxT transcription by time course primer extension assays. AKI conditions stimulated CT synthesis with an absence of ctxAB transcription during static growth followed by induction upon shaking. ToxR-dependent toxT transcription was induced at the end of the static growth period but was transient, stopping shortly after shaking was initiated but, interestingly, also if the static phase was prolonged. Immunoblot assays showed that ToxR protein levels were not coincidentally transient, implying a protein on/off switch mechanism for ToxR. Despite the transient activation by ToxR, transcription of ctxAB was maintained during shaking. This finding suggested continued toxT expression, possibly through relay transcription from another promoter. The 12.6-kb distant upstream tcpA promoter responsible for expression of the TCP operon has been proposed to provide an alternate toxT message by readthrough transcription. Activation of the tcpA promoter is supported by increased expression of TcpA protein during the shaking phase of the culture. Readthrough transcription of toxT from tcpA would be compatible with reverse transcription-PCR evidence for a toxT mRNA at times when ToxR-dependent transcription was no longer detectable by primer extension.

Cholera is caused by the human pathogen Vibrio cholerae O1, a gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the small intestine of its host. It is known that environmental stimuli affect the control of virulence gene expression in V. cholerae. It has been theorized that the function of this regulation may be to optimize energy expenditure for vibrios to achieve a successful infection. One of the most important V. cholerae virulence factors is cholera toxin (CT). CT is the main factor responsible for the abundant fluid loss that characterizes the disease. CT is a prototype ADP-ribosylating enterotoxin encoded by the ctxAB operon, which resides in the genome of a filamentous, lysogenic phage called CTXφ (35). In addition to CT, there are other virulence factors associated with the pathogenicity of V. cholerae, whose expression is coordinately regulated by an activator called ToxR (7, 9, 32). Because of this coordinated regulation, genes controlled by ToxR are collectively termed the ToxR regulon (26). It has been proposed that ToxR, which is a membrane-located transcriptional activator, mediates regulation of virulence gene expression in response to external changes in osmolarity, nutrients, and pH (8). Proof of the important role of ToxR is that strains with null mutations in toxR are deficient in virulence factor production and are avirulent (25). Reduction in virulence factor expression has now been shown to be due largely to the inability to produce a second regulator, ToxT, which is considered the direct effector of most of the ToxR-regulated transcription. This has led to the proposal of a cascade model to explain virulence gene regulation in V. cholerae (9). ToxT is an AraC-like protein that activates several virulence genes in the ToxR regulon (9, 29). The carboxyl-terminal domain of ToxT has a helix-turn-helix motif, characteristic of this family of activators, but its amino terminus does not show significant similarity to other AraC-like proteins (14). Although early work (7, 22) suggested that both ToxR and ToxT independently activate transcription of ctxAB, more recent work indicates ctxAB is activated solely by ToxT in V. cholerae, raising a question of the precise role of ToxR in ctxAB control (5, 10). ToxT also controls the expression of the toxin coregulated pilus (TCP) and of the accessory colonization factor (acf) genes (9).

The toxT gene possesses one proximal ToxR-dependent promoter. Sequences within this promoter contain a specific binding site for the ToxR protein, as shown by in vitro gel shift and footprinting experiments (5a, 16). Apart from the proximal toxT promoter, a second message for ToxT can be generated from the distal tcpA promoter that controls expression of the TCP gene cluster, which includes the toxT gene itself (2, 36). The finding of decreased toxT mRNA levels in a tcpA promoter mutant (36) supports toxT transcription from this promoter. Because ToxT induces tcpA expression, transcriptional readthrough from this promoter provides a self-regulatory mechanism for toxT (2, 36).

The two major biotypes of V. cholerae, classical and El Tor, each require ToxR and ToxT for activation of virulence factors, and potential regulatory sequences are largely conserved between the two biotypes. Nevertheless, the mechanism controlling expression of toxT appears to be biotype specific (10), because classical strains express CT and TCP under a wide range of experimental conditions, while El Tor strains require specific growth conditions, termed AKI, for detectable expression of the ToxR regulon (10, 17, 21). Such conditions comprise a biphasic culture where vibrios are first statistically grown for a 4-h period and then shifted to shaking (17). The recent finding that toxT expression from the inducible tacP promoter in El Tor makes CT synthesis essentially independent of AKI culturing immediately suggested a direct involvement of the ToxR/ToxT system (10). In classical strains, which have more permissive growth requirements for expression of the ToxR regulon, the relative contributions of ToxR and ToxT to transcription of toxT have been thoroughly analyzed (36), but analysis of how ToxR and ToxT participate in modulating toxT and ctxAB transcription under AKI culture conditions is not known. To gain insight into the molecular basis for control of CT and TCP production in V. cholerae El Tor, we performed experiments analyzing toxT and ctxAB transcription over time during AKI growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Strains were maintained at −70°C in LB medium containing 20% glycerol. The classical V. cholerae strain O395 was grown at 30°C in LB medium, and the V. cholerae El Tor strain E7946 was grown at 37°C in AKI medium (17) without sodium bicarbonate (18). The classical strain was used to generate a toxT primer extension product used as a reference to estimate the sizes of the toxT and ctxA primer extension products from the El Tor strain.

RNA isolation and primer extensions.

To isolate RNA from the classical strain, bacteria were harvested from cultures prepared by a 1:100 dilution of an overnight culture into 50 ml of fresh LB medium for growth under orbital shaking for 2 to 5 h at 30°C. For RNA isolation from the El Tor bacteria, scaled-up cultures (11) were used so as to obtain sufficient material from the early time points and from low-density cultures. Scaled-up cultures designed to be equivalent to 10-ml cultures in 15- by 150-mm tubes (17) were carried out with 500-ml medium volumes placed in a 500-ml cylinder. Medium was inoculated with a 100-μl volume of a bacterial suspension with an A600 reading of 1.0. The cylinder was statically incubated at 37°C for 4 h, after which the culture was poured into a prewarmed 2-liter flask to continue growth under orbital shaking (200 rpm) for an additional 6 h (AKI conditions). We defined non-AKI conditions as those where cultures were either kept without shaking (prolonged static growth) or shaken without a prior static growth period (continuous shaking). For the prolonged static growth condition, the culture was maintained in the cylinder; for continuous shaking, the 500-ml culture was orbitally shaken from the start in the 2-liter flask. From each of these cultures, 25- to 50-ml aliquots were removed every hour, poured over ice, and centrifuged for cell recovery. Collected bacteria were usually stored overnight at −20°C, and RNA extractions were carried out the following day. RNA was obtained from bacterial pellets by using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO-BRL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At the end of the procedure, RNA concentrations were in all cases adjusted to 5 μg/μl on the basis of A260 measurements. This compensated for differences in bacterial density among time points within a growth curve as well as for differences between cultures. RNA aliquots were additionally run in agarose gels to further check for RNA concentrations; these estimates were always consistent with A260 values. Primer extensions for toxT and ctxA transcripts were performed as described previously (15), using toxT primer 5′-CATTAGTTTGAAAAGATTTTTTTCCCAATCAT-3′, where the underlined triplet is complementary to the ATG codon for the first amino acid in ToxT. The ctxA-specific primer was 5′-GAATCTGCCGATATAACTTATCATCATTTGCAT-3′, where the underlined nucleotides are complementary to the codon for amino acid 8 in the mature CtxA protein sequence. For autoradiographic detection of primer extension products (15), denaturing acrylamide gels were run, loading 5 μl of the primer extension reaction mixture per well in all experiments.

RT-PCR.

Evidence for the presence of a toxT mRNA was obtained by treating aliquots from the RNA samples with murine leukemia virus (MLV) reverse transcriptase (RT) followed by PCR with AmpliTaq polymerase, using a GenAmp RNA PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To control for the absence of contaminating template DNA in RNA samples, a PCR was run for each of the tested samples, using the same kit components but omitting the MLV RT. Lack of amplification in the absence of RT confirmed that the PCR products were generated from cDNAs. The upstream primer used for RT-PCR of toxT mRNA was 5′-CTTTACGTGGATCCCTCTCTGCG-3′, where the underlined G hybridizes at position −31 with respect to the initiation codon ATG. The downstream primer was 5′-CTACCCAACTGCAGTGATACAATC-3′, where the underlined triplet is the complementary sequence to the toxT stop codon (TAG). For the control ctxA RT-PCR, the upstream primer was 5′-CGTTTGGATCCAGGGAGCATTATATGGTAAAG-3′, where the underlined triplet corresponds to the start codon, and the downstream primer was 5′-GCGATAAGCTTCATAATTCATCCTGAATTC-3′, where the underlined nucleotides correspond to the complementary stop codon sequence for ctxA.

Immunoblots.

Detection of the ToxR protein throughout the AKI culture was done with bacterial cell pellets collected at the same time points as for RNA aliquots. Due to low bacterial concentrations at the early time points, the amount of sample needed for protein measurements and immunoblots required the processing of relatively large culture volumes. However, processing of culture volumes with low bacterial density provided insufficient material due to poor pelleting during centrifugation. For maximal sample saving, we opted to normalize aliquots by estimating bacterial concentrations through A600. Volumes of bacterial pellets were adjusted according to A600 values, and aliquots were directly resuspended in electrophoresis sample buffer. Cell contents were released by boiling, and samples were loaded in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoreactive protein bands were developed by standard techniques using anti-ToxR rabbit antiserum (kindly provided by J. Mekalanos, Harvard University), peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Miles Laboratories), and chloronaphthol substrate. A commercial molecular weight marker (High Molecular Range Rainbow Marker; Amersham) was used to confirm the expected position for the ToxR immunoreactive band.

Immunodetection of TcpA.

For TcpA detection, bacterial pellets obtained from 50-ml culture aliquots for h 3 and 4 and from 1.5-ml aliquots for subsequent hours were resuspended in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. Resuspended cells were lysed by repeated freeze-thawing, and total protein contents were adjusted to the same value according to protein determinations using a commercial protein determination kit (Bio-Rad). Samples of 5 μl were directly placed on nitrocellulose paper, and TcpA was assayed by in situ reaction with anti-TcpA monoclonal antibody (MAb) 20:2 (20), anti-mouse immunoglobulin G–peroxidase conjugate, and chloronaphthol substrate by standard techniques. Attempts to detect TcpA with MAb 20:2 by Western blotting were not successful due to poor reactivity with the El Tor TCP in this assay (20).

Detection of CT.

Detection of CT was done on culture supernatants and in bacterial pellets. Bacterial pellets from 1 ml of culture were resuspended in 500 μl of PBS, and cell contents were released by three ultrasonication bursts on ice. Supernatants and sonicates were twofold serially diluted and assayed by GM1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (30), using a MAb LT39 reactive with the B subunit of CT (31), using either CT (Sigma) or the B subunit of CT (27) at 1 μg/ml as the standard.

RESULTS

Growth of V. cholerae El Tor under AKI and non-AKI conditions.

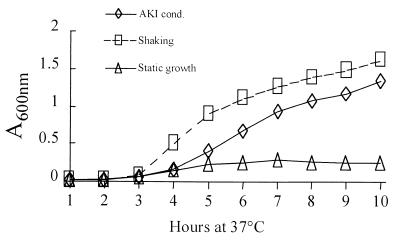

Figure 1 presents the growth curves for strain E7946 under standard AKI conditions, prolonged static growth, and continuous shaking. As seen, the highest growth rate was achieved by continuous shaking. Culturing under AKI conditions also resulted in a high growth rate, but this was dependent on initiation of the shaking phase at h 5. The prolonged static growth culture reached A600s of 0.148 at h 4 and 0.22 at h 5. From this time onward, increases in absorbance were minor, indicating that the early stationary phase had been reached. Based on the latter observation, and to avoid excessive incubation of this culture, a 10-h point to conclude the experiment was chosen. According to previous experiments, this point in time was found to correspond to the early stationary phase for the cultures under the other two growth conditions. The 10-h incubation period seemed also physiologically adequate in terms of CT production because toxin concentrations at this time and after overnight growth were practically the same.

FIG. 1.

Growth curves of V. cholerae El Tor E7946 under AKI and non-AKI conditions. Cultures were grown in AKI medium at 37°C under prolonged static growth (Static growth), continuous shaking (Shaking) or by the AKI method (AKI cond.).

Expression of toxT and ctxAB in V. cholerae El Tor.

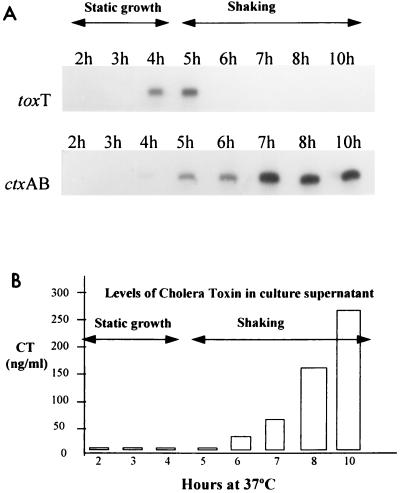

RNA samples prepared from culture aliquots taken every hour were subjected to primer extension using toxT- and ctxA-specific primers. Figure 2 shows ToxR-dependent primer extension products and CT levels for h 2 to 8 and h 10. The toxT primer extension product was abundant at h 4 and 5 but was no longer detectable after this point. We observed induction of ctxAB transcription as soon as the culture was shifted to shaking (Fig. 2). Also, transfer to shaking quickly led to production of CT and its release into the culture supernatant (Fig. 2). CT concentrations paralleled the increase in intensity of the primer extension product from ctxAB. In contrast, and in agreement with experiments that defined AKI conditions (17), growth under continuous shaking resulted in practically undetectable levels of CT. This was reflected in undetectable levels of both toxT and ctxAB primer extension products (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(A) Primer extension products from toxT and ctxAB, and CT levels under AKI conditions. Incubation periods under static growth or shaking phases of an AKI growth are indicated with the double-headed arrows. A composite figure using relevant sections of autoradiographs was constructed to facilitate comparisons. The respective primer extension products are labeled at the left. (B) CT values from GM1 ELISA. Concentrations shown are expressed as equivalents of standard CT per culture supernatant volume unit. Levels of CT in cell pellets were less than 3 ng/ml in all cases.

The results for toxT transcription under prolonged static growth were similar to those for AKI conditions, with the toxT primer extension product appearing at h 4 and disappearing after h 5, except for a comparably lower-intensity primer extension band at this last time (Fig. 3). Under prolonged static growth, there was a virtual absence of the ctxAB primer extension product, except for a very faint band at h 4 (Fig. 3). This faint band was also visible in the AKI culture (Fig. 2), suggesting a low basal activity of ToxT over ctxAB transcription before the start of the shaking culture phase.

FIG. 3.

Primer extension products from toxT and ctxAB under prolonged static growth. Relevant sections of autoradiographs were used to compose the figure and to facilitate comparisons. Samples obtained at different times during culture, as indicated above the lanes, were subjected to primer extension for toxT (upper panel) and ctxAB (lower panel). A barely visible primer extension band was found at h 4 for ctxAB.

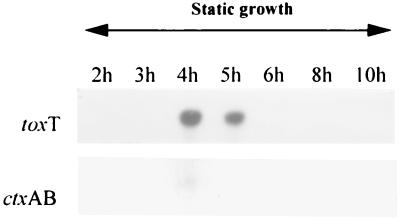

Detection of the ToxR protein under AKI conditions.

To assess ToxR levels through AKI growth, samples of total proteins obtained from time point aliquots throughout the AKI growth curve were analyzed on immunoblots probed with anti-ToxR antiserum (Fig. 4). As seen, the presence of ToxR in cells was detected from h 2 and until h 10. Although some minor variability in the intensity of immunoreactive bands was observed, the experiment demonstrates that ToxR was present during both the static growth and shaking culture phases. Of significance was the fact that ToxR was present during shaking and especially after h 6 (Fig. 4). This is particularly meaningful because in the 6- to 10-h interval the ToxR-dependent toxT primer extension product was undetectable (Fig. 2). This suggests that transient toxT transcription is not due to an effect of AKI conditions on toxR gene expression but rather depends on the ability of ToxR to activate the toxT gene.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot detection of ToxR along the AKI growth curve. To compensate for differences in protein concentration between time points, bacterial cells were lysed by direct boiling in variable volumes of sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Materials and Methods). Times at which aliquots were removed from the AKI culture are indicated above the lanes. Positions for reference protein bands in a commercial molecular weight marker are shown on the left.

RT-PCR detection of toxT transcripts.

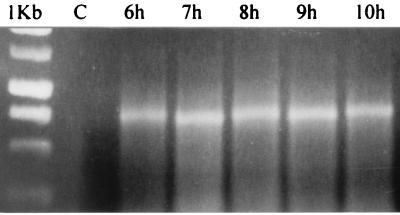

Experiments with classical strains of V. cholerae suggest that after transient ToxR-dependent toxT transcription, toxT transcripts are maintained in the cell, evidently as a result of ToxT-dependent transcription of a large, polycistronic mRNA initiating at the tcpA promoter (36). A similar model could account for the sustained ctxAB transcription during shaking that we observe in the absence of activated ToxR-dependent expression of toxT detectable by primer extension. To determine if this could be so, RNA aliquots from h 6 to 10 were subjected to RT-PCR. Figure 5 shows toxT RT-PCR products whose sizes were compatible with binding of primers at both ends of the toxT structural gene. This experiment demonstrates the presence of a toxT mRNA at times when toxT mRNA arising from de novo activation by ToxR is undetectable. Control reactions in the absence of MLV RT gave no amplification products, confirming the absence of contaminating DNA in samples. An example of a control reaction is shown in Fig. 5. Additional confirmation of successful mRNA detection was obtained by concurrent RT-PCRs with ctxA primers. Similar to results shown, ctxA amplification products were obtained at the same time points (not shown).

FIG. 5.

Detection of a toxT transcript by RT-PCR during h 6 to 10 of an AKI culture. An ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoresis gel is presented. Samples: 1Kb, 1-kb molecular weight marker (Promega); C, example control RT-PCR from an RNA sample (5-h time point) in the absence of RT; 6h to 10h, RT-PCR of RNA samples from h 6 to 10 of an AKI culture (shaking phase). Note that except for the control RNA, all samples corresponded to times at which no ToxR-dependent toxT transcript was detected by primer extension (see Fig. 2).

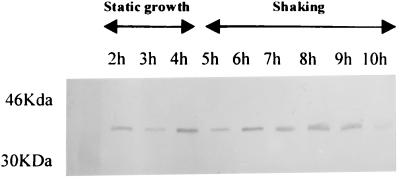

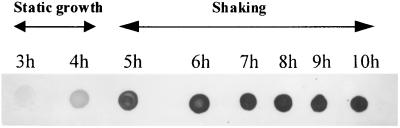

Immunodetection of TcpA.

The tcpA promoter is required for optimal toxT expression and high CT levels in classical V. cholerae. This is because transcription initiating at this promoter results in a large polycistronic message that includes toxT at the 3′ end (2, 36). As a measure of tcpA induction in our El Tor cultures under AKI conditions, and, by extension, a measure of toxT transcription from the tcpA promoter occurring after transient activation by ToxR, we followed expression of the TcpA protein by dot blotting using a MAb against TcpA (20). Hourly aliquots were obtained from h 3 to 10, and TcpA levels were determined by immunoblotting. Results in Fig. 6 show that TcpA was present at all sampled times, although initiation of the shaking culture phase strongly stimulated TcpA production (Fig. 6, 5 h). After this point in time, TcpA levels remained essentially constant (Fig. 6, 5 to 10 h). Since TcpA synthesis is strongly induced by the presence of ToxT in the cell (2), continued expression of TcpA during shaking would suggest sustained expression of toxT. However, toxT transcription from its ToxR-dependent promoter was no longer detectable by primer extension after h 6 (Fig. 2). These results could be reconciled if there were toxT transcription initiating from tcpA during the shaking culture phase in a manner similar to that described for classical strains under non-AKI conditions (36) (see Discussion).

FIG. 6.

Detection by dot blotting of TcpA in bacterial cell lysates from an AKI culture. Times at which aliquots were obtained are indicated above the dots. Incubation periods under static growth or shaking are indicated with the double-headed arrows.

DISCUSSION

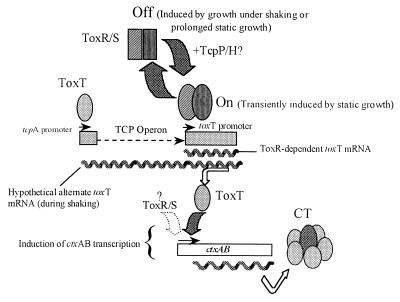

The expression of CT under AKI conditions has been the subject of recent experiments aimed at explaining the role of the positive regulator ToxT in CT production by V. cholerae El Tor (10). Here we provide evidence for a delicately concerted regulation of ToxT by ToxR through a transient transcription of the toxT gene, not previously detected if AKI cultures were sampled at a later time (10). Transient transcription apparently takes place in response to the combination of static growth and culture cell density because induction occurred during the static period and at the early stationary phase. These results are in agreement with the initial physiological studies performed by Iwanaga et al., who showed that a 4-h static growth period followed by strong aeration was optimal to stimulate CT production in V. cholerae El Tor (17, 18). We found that ToxR-driven transcription of toxT was initiated precisely at the h 4 yet expression was transient, continuing for only 1 h during shaking. This result indicated that ToxR was unable to sustain its positive effect over toxT transcription. Irrespective of this, transfer of cultures to shaking stimulated transcription of ctxAB, along with the appearance of CT in the medium. Interestingly, when cultures were not shifted to shaking but instead continued under static growth, the toxT primer extension product also disappeared after h 5 (Fig. 3). This finding indicated that ToxR was unable to maintain positive regulation over toxT also when the static growth phase was prolonged. Thereby, positive regulation of toxT by ToxR seems to occur only within a narrow physiological window sensitive to either strong aeration or prolonged static growth. We propose that the ToxR response involves a change in its ability to activate the toxT promoter, as opposed to modulation of toxR gene expression, because immunoblot experiments showed the ToxR protein was produced throughout the AKI culture (Fig. 4). Especially meaningful was the fact that ToxR was present after h 6, times at which activation of toxT transcription by ToxR was no longer detectable by primer extension (Fig. 2). These results are in agreement with the previous report of ToxR expression in El Tor vibrios regardless of growth conditions (10). An on/off switch for ToxR (ToxR/S) activity would be a simple model to explain transcriptional control of toxT from the promoter directly upstream (Fig. 7). In this switch model, we propose that at h 4 and 5, ToxR is in its on condition and that shaking or prolonged static growth beyond this point induces the ToxR off status (Fig. 7). Switching between on and off stages could be proposed to involve changes between ToxR-ToxR and/or ToxR-ToxS dimeric and monomeric molecular species (8, 24). However, induction or deactivation of ToxR may require the participation of other regulators since simple changes in amounts of dimeric versus monomeric forms do not account for ToxR responses to environmental stimuli in classical vibrios (24). Likely candidates that could affect ToxR control over toxT are TcpP and TcpH. Mutations in tcpH result in undetectable or reduced ToxR-dependent toxT transcription and CT synthesis in the classical V. cholerae strain O395 (3, 36), while TcpP stimulates toxT transcription in 0395 (13). Furthermore, a positive synergistic effect on toxT transcription has been observed when both TcpP and TcpH are present in the cell (13). This has led to the hypothesis that TcpP and TcpH constitute a positive regulatory system functionally similar to the ToxR/S system (13). Analysis of tcpP mutants in O395 showed that ToxR-dependent toxT transcription normally requires the joint action of both TcpP and ToxR (21a, 36). In view of this, it is quite possible that the proposed on/off ToxR switch involves TcpP, perhaps through the formation of a complex consisting of TcpP/H and ToxR/S. Experiments are under way to test this hypothesis.

FIG. 7.

Hypothetical model for the role of ToxR in the V. cholerae El Tor response to AKI conditions. Boxes represent genes, and arrows above them indicate promoters as well as direction of transcription. The discontinuous arrow represents genes located between tcpA and toxT in the TCP operon (2). Wavy lines symbolize mRNAs. Other arrows indicate transition between ToxR states or mRNA translation. The ToxT protein (filled oval) is shown above the tcpA and ctxAB promoters to indicate its role as a transcriptional inducer of both genes (2, 9). A diagrammatic representation of CT is included. The postulated on status of ToxR (ToxR/S), induced by static growth, is represented by dashed ovals; the postulated off status, induced by shift to shaking, or by prolonged static growth, is represented by dashed squares. A potential participation of TcpP/H (+TcpP/H?) in promoting the on status is indicated. Positive modulation by TcpP/H under AKI conditions would not disagree with previous reports on TcpP/H stimulation of ToxR-dependent toxT transcription (3, 13, 23, 33). A potential contribution to ctxAB expression by ToxR/S is indicated with a dashed arrow.

According to early work (7, 22), the sustained ctxAB transcription observed (Fig. 2), in spite of reduction or absence of the ToxR-dependent toxT transcription, could be explained by direct action of ToxR over ctxAB. However, recent studies point to major, and perhaps exclusive, activation of ctxAB by ToxT in V. cholerae (5, 10). Lack of an independent ToxR activity on ctxAB in our studies is supported by the fact that VJ739 (5), a ToxT− ToxR+ mutant of El Tor strain E7946, was unable to produce CT when grown in parallel and under the same AKI conditions (data not shown). This implies the need to account for induction of ctxAB transcription through control of ToxT levels in the cell. Maintained ToxT concentrations could be due to low-level transcription from the same promoter that was undetectable; nonetheless, low-level transcription would seem insufficient to account for the strong ctxAB transcription observed (Fig. 2). The need of de novo synthesis to maintain ToxT levels in the cell appears likely. First, ToxT dilution due to mass increase during growth would imply an inverse relation between ToxT activity and protein concentration. Second, ToxT has proven highly labile in purification schemes applied to classical V. cholerae strains (7a), which may suggest that the protein is inherently unstable. An alternative to ToxR-dependent activation for sustaining ToxT production would be through the presence of toxT message by readthrough transcription from a different promoter.

A candidate promoter located 12.6 kb upstream of the toxT gene and in front of the tcpA gene, the first of 12 contiguous genes in the TCP operon, has been proposed to generate a long mRNA containing a transcript for ToxT in the classical strain O395 (2). Although a 12- to 13-kb-long message has not formally been shown, a tcpA-dependent message, containing both the upstream tcpF and toxT transcripts, has been demonstrated by RNase protection studies (2). Moreover, because toxT activates tcpA, a positive feedback effect has been proposed and theorized to represent a self-regulatory mechanism for ToxT (2). This is in full agreement with the recent observation that the tcpA promoter in O395 is required for maximal toxT transcription and CT production (36). That transcription from tcpA plays a role in AKI cultures is supported by the fact that TCP synthesis in El Tor vibrios is positively stimulated by those culture conditions (10, 21). In this report, we provide evidence in support of toxT transcription from the tcpA promoter. We detected a transcript for the structural toxT gene by RT-PCR (Fig. 5) at times when ToxR-dependent toxT primer extension product was undetectable (h 6 to 10). Attempts to demonstrate that this transcript comes from the hypothetical polycistronic TCP mRNA by RT-PCRs using commercial enzymes specially designed to obtain products longer than 12 kb were not successful. This failure could be due to mRNA processing at internal positions within the TCP operon and/or to an unstable message (2). In view of this difficulty, and considering that in O395 tcpA expression has been found to closely correlate with transcription of the whole operon including tcpJ the gene lying immediately downstream of toxT (2), we assayed for the presence of TcpA by dot blot experiments. We found synchronous induction of TcpA production (Fig. 6) coincident with ctxAB transcription throughout the shaking culture phase. This finding is in complete agreement with primer extension experiments showing that very little tcpA transcript is made before h 4, with an increase in level after this time point; thereafter the level is maintained throughout the rest of the culture (21b).

Because ToxT activates tcpA and we found increases in TcpA, it follows that high TcpA concentrations may be due to the presence of higher than basal ToxT levels in the cell. In the virtual absence of ToxR-dependent transcription (Fig. 2), higher ToxT levels could be explained by the same self-dependent readthrough transcription mechanism operating in classical strains (36).

This hypothesis is summarized in a model presented in Fig. 7. The model includes the above-discussed on/off switch mechanism for ToxR and proposes to account for the role of ToxR (ToxR/S) and ToxT in the response of V. cholerae El Tor to AKI conditions. We have incorporated in the model the above-discussed potential participation of the positive regulators TcpP and TcpH (13), indicating that they could enhance the effect of ToxR (ToxR/S) over the toxT promoter (Fig. 7). Completion of the model will require determining if the differences in activity between TcpP/H from classical and El Tor vibrios (4) is of relevance to this system. It will also be helpful to define if the cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein complex and TcpI, both of which are negative TCP operon regulators in classical strains (28, 29), contribute to the final steady-state levels of ToxT in El Tor vibrios. However, the proposal for TcpI as a negative tcpA regulator has been questioned (33). Finally, the reason for the requirement of a shaking culture phase to induce ctxAB transcription remains to be determined.

In terms of the biomedical relevance of results here presented, it is clear that the V. cholerae El Tor response to external stimuli seems exquisitely sensitive and most appropriately designed to express CT only when certain growth conditions are met. Such conditions appear to include the bacterial population status and suggest that V. cholerae senses its own cell density in the intestine (19), in analogy to quorum sensing by phylogenetically related bacteria (1). If this type of sensitively concerted expression of virulence genes reflects events during infection, El Tor vibrios can be assumed to produce CT not continuously but in bursts. The burst would occur at the point where bacterial multiplication and nutrient consumption inside the gut have led to conditions equivalent to those under an AKI growth. Production of CT with its fluid secretion activity would flush bacteria out of the intestine; remaining vibrios would reinitiate the growth cycle. Newly multiplied bacteria would be flushed again when the same conditions are present. How this would be advantageous for vibrios is not clear, but if initial CT synthesis occurred at relatively low bacterial densities, as seen in vitro, total amounts of CT inside the gut would also be relatively low by the time bacteria were expelled. This may result in a less aggressive infection, which in turn could help explain why El Tor vibrios cause a less severe disease, with a higher proportion of asymptomatic cases, than classical strains (12). A theoretical ecological advantage derived from a less severe disease is that if El Tor-infected individuals are less debilitated, they could more easily disseminate vibrios into the environment (6). A more efficient dissemination could explain why the El Tor biotype has quickly established itself throughout the world in the last decades. In the latter respect, it is noteworthy that the more recent, rapidly spreading V. cholerae O139 shares many characteristics with V. cholerae El Tor, including a requirement for growth under AKI conditions to produce CT (33).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. L. Puente and E. Morett for useful discussions, Rosa Yu for assistance with primer extension experiments and comments on the manuscript, and Patricia Romero for help with immunoblots.

J.S. gratefully acknowledges a stipend by Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (Mexico). A.I.M. was recipient of a scholarship for Ph.D. studies (CONACYT, Mexico). This work was supported by grant SPE-VACC-HN-01 (SAREC-SIDA, Sweden) (to J.S.) and Public Health Service grant AI 31645 (to V.J.D.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler B L, Greenberg E P, Stevens A M. Cross-species induction of luminescence in the quorum-sensing bacterium Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4043–4045. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4043-4045.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown R C, Taylor R K. Organization of tcp, acf, and toxT genes within a ToxT-dependent operon. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:425–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll P A, Tashima K T, Rogers M B, DiRita V J, Calderwood S B. Phase variation in tcpH modulates expression of the ToxR regulon in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1099–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5371901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll P A, Skorupski K, Taylor R K, Calderwood S B. Abstracts of the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1998. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Differences in transcription and activity of the tcpPH gene products explains differential regulations of the ToxR regulon between classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae, abstr. B-185; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champion G A, Neely M N, Brennan M A, DiRita V J. A branch in the ToxR regulatory cascade of Vibrio cholerae revealed by characterization of toxT mutant strains. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:323–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2191585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Crawford, J. A., and V. J. DiRita. Unpublished data.

- 6.Ewald P W. Waterborne transmission and the evolution of virulence among gastrointestinal bacteria. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;106:83–119. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiRita V J. Co-ordinate expression of virulence genes by ToxR in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.DiRita, V. J. Unpublished data.

- 8.DiRita V J, Mekalanos J J. Periplasmic interaction between two membrane regulatory proteins, ToxR and ToxS, results in signal transduction and transcriptional activation. Cell. 1991;64:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90206-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiRita V J, Parsot C, Jander G, Mekalanos J J. Regulatory cascade controls virulence factors in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5403–5407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiRita V J, Neely M, Taylor R K, Bruss P M. Differential expression of the ToxR regulon in classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae is due to biotype-specific control over toxT expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7991–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubey R S, Lindblad M, Holmgren J. Purification of El Tor cholera enterotoxins and comparisons with classical toxin. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1839–1847. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-9-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass R I, Becker S, Huq I M, Stoll B J, Khan M U, Merson M H, Lee J V, Black R E. Endemic cholera in rural Bangladesh, 1966–1980. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116:959–970. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Häse C C, Mekalanos J J. TcpP protein is a positive regulator of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:730–734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins D E, Nazareno E, DiRita V J. The virulence gene activator ToxT from Vibrio cholerae is a member of the AraC family of transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6974–6980. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6974-6980.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins D E, DiRita V J. Transcriptional control of toxT, a regulatory gene in the ToxR regulon of Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:17–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins D E, DiRita V J. Genetic analysis of the interaction between Vibrio cholerae transcription activator ToxR and toxT promoter DNA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1080–1087. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1080-1087.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwanaga M, Yamamoto K, Higa N, Ichinose Y, Nakasone N, Tanabe M. Culture conditions for stimulating cholera toxin production by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30:1075–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwanaga M, Kuyyakanond T. Large production of cholera toxin by Vibrio cholerae O1 in yeast extract peptone water. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2314–2316. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.12.2314-2316.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jobling M G, Holmes R K. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1023–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6402011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonson G, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A M. Epitope differences in toxin-coregulated pili produced by classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonson G, Svennerholm A M, Holmgren J. Expression of virulence factors by classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae in vivo and in vitro. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;74:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 21a.KruKonis, E. S., and V. J. DiRita. Unpublished data.

- 21b.Miller, A., V. J. DiRita, and J. Sanchez. Unpublished data.

- 22.Miller V L, Taylor R K, Mekalanos J J. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell. 1987;48:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogierman M A, Voss E, Meaney C, Faast R, Attridge S R, Manning P A. Comparison of the promoter proximal regions of the toxin-co-regulated tcp gene cluster in classical and El Tor strains of Vibrio cholerae O1. Gene. 1996;170:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otteman K M, Mekalanos J J. The ToxR protein of Vibrio cholerae forms homodimers and heterodimers. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:156–162. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.156-162.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson G D, DiRita V J, Goldberg M B, Boyko S A, Calderwood S B, Mekalanos J J. New attenuated derivatives of Vibrio cholerae. Res Microbiol. 1990;141:893–899. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(90)90127-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson K M, Mekalanos J J. Characterization of the Vibrio cholerae ToxR regulon: identification of novel genes involved in intestinal colonization. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2822-2829.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez J, Holmgren J. Recombinant system for overexpression of cholera toxin B subunit in Vibrio cholerae as a basis for vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:481–485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skorupski K, Taylor R K. Cyclic AMP and its receptor protein negatively regulate the coordinate expression of cholera toxin and toxin co-regulated pilus in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:265–270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skorupski K, Taylor R K. Control of the ToxR virulence regulon in Vibrio cholerae by environmental stimuli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1003–1009. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5481909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svennerholm A M, Holmgren J. Identification of Escherichia coli heat labile enterotoxin by means of a ganglioside immunosorbent assay (GM1-ELISA) procedure. Curr Microbiol. 1978;1:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svennerholm A M, Wikström M, Lindholm L, Holmgren J. Monoclonal antibodies and immunodetection methods for Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. In: Macario A J, et al., editors. Monoclonal antibodies against bacteria. III. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor R K, Miller V L, Furlong D B, Mekalanos J J. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2833–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas S, Williams S G, Manning P A. Regulation of tcp genes in classical and El Tor strains of Vibrio cholerae O1. Gene. 1995;166:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00610-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J. ToxR regulates virulence gene expression in non-O1 strains of Vibrio cholerae that cause epidemic cholera. Infect Immun. 1994;62:72–78. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.72-78.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science. 1996;272:1910–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, R. R., and V. J. DiRita. Analysis of an autoregulatory loop controlling ToxT, cholera toxin, and toxin-coregulated pilus production in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]