Abstract

Mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID mice) lack functional B and T cells. Egg laying by Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum was delayed in SCID mice, but in a matter of weeks worm fecundity was equivalent to that in intact mice. SCID mice formed smaller hepatic granulomas and showed less fibrosis than did intact mice. The reduction in egg-associated pathology in SCID mice correlated with marked reductions in interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-13, and gamma interferon mRNA expression in the liver. S. mansoni infections were frequently lethal for SCID mice infected for more than 9 weeks, while S. japonicum-infected SCID mice died at the same rate as infected intact mice. We were unable to affect hepatic granuloma formation or egg laying by worms in SCID mice by administration of recombinant murine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). In fact, SCID and BALB/c mice appeared to express nearly equivalent levels of TNF-α mRNA in their granulomatous tissues, suggesting that there is little or no deficit in TNF-α expression in infected SCID mice. The data indicate that TNF-α may be in large part derived from a non-T-cell source. Together, these findings provide little evidence that TNF-α alone can reconstitute early fecundity, granuloma formation, or hepatic fibrosis in schistosome-infected SCID mice.

Most morbidity in schistosome-infected mice is related to the host’s reaction to eggs laid by the worms, which reside in the mesenteric venules. Egg laying begins after 4 to 5 weeks of infection, and many eggs are carried to the liver, where they elicit cell-mediated granulomas (3). These circumoval granulomas in Schistosoma mansoni- or S. japonicum-infected mice are mediated by a complex interaction of cells and cytokines (5, 12, 18). In mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID mice), S. mansoni eggs elicit almost no reaction in the tissues (1, 16) and S. japonicum eggs elicit only a moderate reaction. Surprisingly, egg production during the first weeks of egg laying is also markedly reduced in SCID mice (1), as it is in T-cell-depleted (8) or nude (2) mice. Amiri et al. reported that administration of exogenous tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) to mice partially restored granuloma formation and the number of eggs per worm pair found in the livers of SCID mice (1). These data implied that infected SCID mice were likely deficient in TNF-α and that this deficit was the critical factor leading to the ineffective granulomatous response as well as egg laying.

Nevertheless, similar studies of mice suggested that Th2-associated cytokines are also involved in the host response to infection with schistosomes. T-cell depletion studies performed in intact mice have confirmed an essential role for CD4+ T cells in egg-induced granuloma formation (13). Moreover, cytokine depletion studies confirmed that interleukin-4 (IL-4) plays a major role in the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis and in Th2 response development in schistosomiasis (4, 12). Indeed, recent studies showed that pulmonary granuloma formation could be almost completely ablated in mice deficient in both IL-4 and IL-13 (6). Here, the reduction in granuloma size and tissue eosinophilia was again attributed to a markedly decreased Th2-type response. Finally, the most definitive evidence for a primary role for Th2-associated cytokines in granuloma formation came from recent studies examining schistosome infection in Stat6-deficient mice (10). These mice lacked Th2 cells and consequently developed pulmonary and hepatic granulomas that were much smaller than those in control littermates. A marked decrease in liver hydroxyproline content was also observed. In contrast, Stat4-deficient mice that were defective in gamma interferon (IFN-γ) expression produced Th2-type cytokines in amounts comparable to those produced by control mice and displayed a relatively unimpaired granulomatous response. Together, these studies highlighted the critical role of the type 2 response in both pulmonary and hepatic granuloma formation and more importantly, in the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis in schistosomiasis.

Because of the striking results obtained with recombinant TNF-α in infected SCID mice (1), which indirectly suggested that Th2-type cytokines were, in fact, dispensable elements in the granulomatous response, we investigated whether the findings of Amiri et al. would extend to S. japonicum-infected mice. When we were unable to see an effect of exogenous TNF-α during S. japonicum infections, we used S. mansoni but were also unable to find an effect of TNF-α in the S. mansoni-infected SCID mice. We also demonstrate in the present study that egg laying is delayed in both S. mansoni- and S. japonicum-infected SCID mice but that normal levels of fecundity are reached a few weeks later.

S. japonicum infections were of interest to us for several reasons. Egg laying in intact mice begins 4 weeks after infection with S. japonicum and 5 weeks after infection with S. mansoni, and S. japonicum, in contrast to S. mansoni, produces normal numbers of eggs early in the course of infection of nude mice (2). Second, the reaction to S. japonicum eggs differs morphologically from the reaction to S. mansoni eggs (17). Finally S. mansoni-infected immunodeficient mice suffer severe mortality beyond week 8 of infection so that it is difficult to examine chronic infections (2). In contrast S. japonicum-infected immunodeficient mice survive well (2), perhaps because a hepatotoxic antigen present in S. mansoni eggs (14) is not present in S. japonicum eggs. Finally, we have found that intact BALB/c mice have only a slight reaction to S. japonicum eggs (1a), and so we also infected C57BL/6 mice and C57BL/6 SCID mice with S. japonicum to maximize the possibility of demonstrating a restoration of granuloma formation by exogenously given TNF-α.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

CB17 SCID mice were bred from stock obtained from Taconic Farms, Germantown, N.Y. C57BL/6 SCID mice were bred from stock from the Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine. SCID mice were maintained in sterilized cages and given sterilized mouse chow and acidified water ad libitum, and cages were changed in a laminar flow hood. Intact BALB/c and C57BL/6 (B6) mice from the Division of Cancer Treatment, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md., were used as immunocompetent controls. Mice were infected with 25 to 30 cercariae of a Puerto Rican (NMRI) strain of S. mansoni percutaneously or 15 to 20 cercariae of a Philippine (Lowell) strain of S. japonicum by subcutaneous injection of cercariae from crushed Oncomelania hupensis snails. The number of mice studied is indicated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of mice examined

| Group | No. of mice examined at wk:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 15 | |

| S. mansoni infected | ||||||||

| CB17 SCID | 8 | 15 | 24 | 16 | 13 | |||

| BALB/c intact | 8 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 14 | |||

| CB17 SCID + TNF | 0 | 0 | 34 | 8 | 0 | |||

| S. japonicum infected | ||||||||

| CB17 SCID | 4 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 12 | |||

| BALB/c intact | 4 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 7 | |||

| CB17 SCID + TNF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C57BL/6 SCID | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C57BL/6 intact | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |||

| B6 SCID + TNF | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |||

Serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on Immulon 2 plates, using goat anti-mouse kappa chain as the coating antibody and goat anti-mouse IgM labeled with horseradish peroxidase (both from Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.). Mouse IgM kappa (Sigma Immunochemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) was used as the standard.

IgM levels averaged 5 and 0.5 μg/ml in uninfected CB17 SCID and C57BL/6 SCID mice at 4 to 5 months of age, 200 to 500 μg/ml in uninfected conventional BALB/c and B6 mice, and 700 to 5,400 μg/ml in infected conventional mice. IgM concentrations were <5 μg/ml in 90% of S. mansoni- or S. japonicum-infected SCID mice and reached maximal levels of 80 μg/ml in the remaining mice, which did not differ from the other SCID mice either in tissue reactions to schistosome eggs or in the number of eggs per worm pair found in the tissues. No other tests for leakiness of SCID mice were performed.

We were unable to ascertain the anatomic cause of death in most schistosome-infected SCID mice that died, although they were generally cachectic. Immunologically intact mice that died from S. mansoni infection generally showed bleeding into the gut lumen. No Pneumocystis carinii or other infectious agent was found by histologic examination of the lungs and liver in any of the dead mice or in those sacrificed.

Adult worms were recovered from the portal system by perfusion (7). We have previously described the techniques used to determine hepatic hydroxyproline, used as a measure of fibrosis, egg numbers in the liver and intestines, and the measurement of granulomas in histologic sections (2, 4) stained with Litt’s modification of the Dominici stain (11). We measured only granulomas surrounding single eggs that contained a mature embryo. Eggs in the feces were counted in 1-ml Sedgwick-Rafter chambers (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, Pa.) after removal of coarse debris on coarse nylon cloth and concentration of eggs on fine nylon cloth (3).

Recombinant murine TNF-α was generously provided by Genentech Inc. at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. In our L929 fibroblast assay, the batch used (4296-17) contained between 1 × 109 and 5 × 109 U/mg. TNF was given by intraperitoneal injection, using a dose and time range more extensive than that reported by Amiri et al. (1).

Cytokine assays.

For in vitro cytokine measurements, single-cell suspensions of spleens were prepared aseptically at various times after infection. Cells were plated in 24-well tissue culture plates at a final concentration of 3 × 106 cells per ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 10% fetal calf serum, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin, and streptomycin. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were stimulated with schistosome egg antigens (SEA; 20 μg/ml), schistosome worm antigen preparation (SWAP; 50 μg/ml) or concanavalin A (ConA; 5 μg/ml). Supernatant fluids were harvested at 72 h and assayed for cytokine activity. IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-5 were measured by specific two-site ELISA as previously described (4). IL-4 levels were determined by proliferation of CT4S cells. TNF-α was measured by using a murine TNF-α ELISA kit from Genzyme (Cambridge, Mass.). Cytokine levels were calculated from standard curves constructed by using recombinant murine cytokines.

Isolation and purification of mRNA.

RNase-free plastic and water were used throughout. Two 50-mg portions of the liver were homogenized in 1 ml of RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, Tex.) in a tissue polytron (Omni International, Waterbury, Conn.), and total RNA was isolated as recommended by the manufacturer. The RNA was resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water and quantitated spectrophotometrically.

RT-PCR detection of cytokine mRNAs.

A reverse transcriptase-mediated PCR (RT-PCR) was performed to determine relative quantities of mRNAs for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT). Reverse transcription of 1 μg of RNA was performed as described previously (19). The final cDNA was diluted 1:8, and 10 μl was used in the PCR. The primers and probes for all genes have been published elsewhere (19). The PCR conditions, also as described elsewhere (20), were strictly defined for each cytokine primer pair such that a linear relationship between input RNA and final PCR product was obtained. Both positive and negative controls were included in each assay to confirm that only cDNA PCR products were detected and that none of the reagents was contaminated with cDNA or previous PCR products. After the appropriate number of PCR cycles, the amplified DNA was analyzed by electrophoresis, Southern blotting, and hybridization with nonradioactive cytokine-specific probes as previously described (19).

Analysis and quantitation of PCR products.

The chemiluminescent signals were quantified with a 600 ZS scanner (Microtek, Torrance, Calif.). The amount of PCR product was determined by plotting the specific cytokine mRNA signal over the signal generated for HPRT (cytokine/HPRT × 100). Arbitrary densitometric units for individual animals were determined, and the averages and standard errors of the means (SEM) for each cytokine were graphed. Statistical comparisons were made by Student’s t test, and P values of <0.05 were taken as significant.

RESULTS

Infection and mortality in SCID mice.

The numbers of worms recovered from SCID and intact mice did not differ significantly (data not shown). No S. japonicum-infected SCID mice died before week 7 of infection, and 4% died between weeks 7 and 10; none of 12 animals followed from weeks 10 to 15 died, although they carried an average of five worm pairs and S. japonicum lays 10 times more eggs per day than S. mansoni. Mortality was similar in intact BALB/c and B6 mice infected with S. japonicum.

SCID mice infected with two to four worm pairs of S. mansoni began to die 9 weeks after infection. Between weeks 9 and 11, 11 of 25 SCID mice but only 2 of 15 S. mansoni-infected BALB/c mice died. The intensity of infection averaged 1.8 worm pairs at that time.

A 5-μg dose of TNF-α induced no mortality in infected SCID mice, while 10 μg killed 7 of 8 S. mansoni-infected SCID mice in one experiment but none of 10 in another. In the second experiment, 20 μg of TNF-α killed three of six S. mansoni-infected treated mice and 40 μg killed all of four injected mice.

Delayed patency and fecundity in SCID mice.

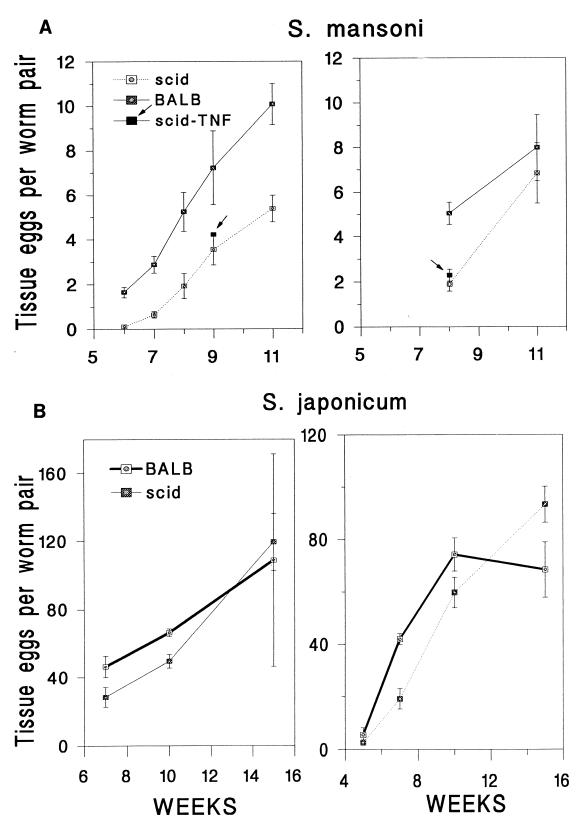

Eggs in the tissues were counted at several time intervals after infection, as the results of Amiri et al. (1) indicated a reduction of fecundity in S. mansoni-infected SCID mice and our own experience in immunodeficient mice indicated a delay rather than a reduction in egg laying (2). Egg laying began later, and for 1 to 2 weeks eggs accumulated more slowly in the tissues of S. mansoni- or S. japonicum-infected SCID mice than in intact mice; after week 6 of S. japonicum infection or week 7 of S. mansoni infection, however, equivalent numbers of eggs per worm pair accumulated in the tissues of SCID and intact mice, as indicated by the nearly parallel lines for deficient and intact mice in the plot of eggs per worm pair versus time; i.e., the number of eggs per worm pair per unit time remained the same once egg laying was established (Fig. 1). Injection of recombinant murine TNF-α did not affect the rate of accumulation of eggs in the tissues of S. mansoni-infected SCID mice (Fig. 1, arrow) or in S. japonicum-infected mice in two experiments (Table 2) in which C57BL6 SCID mice (killed 7 to 8 weeks after infection) were injected with 5 μg TNF-α, once at 6 weeks as performed in the study by Amiri et al. (1) or four times at 4, 5, 6, and 7 weeks.

FIG. 1.

Accumulation of eggs in the tissues, expressed in thousands of eggs per worm pair, in two independent experiments for both S. mansoni-infected (A) and S. japonicum-infected (B) BALB/c and CB17 SCID mice. In panel A, the results for TNF-α-treated (5 μg/mouse 1 week prior to sacrifice [upper left panel] or 5 μg twice in the week before sacrifice [upper right panel]) SCID mice are indicated for single time points (9 weeks [upper left panel] and 8 weeks [upper right panel]) for S. mansoni-infected mice (arrows). Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

TABLE 2.

Lack of effect of recombinant TNF-α on granuloma size, hepatic fibrosis, or worm fecundity in S. japonicum-infected C57BL/6 mice

| Expt | Mouse strain | Mean ± SDa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total tissue eggs (103)/WP (103) (no. of WP) | Fecal eggs/WP/day | Granuloma vol (mm3 [10−3]) | Hydroxyproline (μmol/10,000 eggs) | ||

| 1 | B6 intact | 53 ± 3 (4) | ND | 39 ± 2 | 1.9 ± 0.05 |

| B6 SCID | 37 ± 4 (4) | ND | 21 ± 1 | 0.2 ± 0.09 | |

| B6 SCID + TNFb | 32 ± 6 (5) | ND | 20 ± 7 | 0.5 ± 0.17 | |

| 2 | B6 intact | 35 ± 2 (5) | 316 ± 88 | 58 ± 6 | 1.7 ± 0.42 |

| B6 SCID | 13 ± 2 (4) | 59 ± 9c | QNS | 0.2 ± 0.07 | |

| B6 SCID + TNF | 9 ± 1 (5) | 266 ± 106 | QNS | 0.3 ± 0.13 | |

WP, number of worm pairs; ND, not done; QNS, quantity not sufficient (no granulomas containing mature eggs were seen in sections of B6 SCID livers in these groups).

In experiment 1, 5 μg of recombinant TNF-α was given intraperitoneally at weeks 4, 5, 6, and 7 after infection, and the mice were killed at week 8. In experiment 2, 5 μg of recombinant TNF-α was given intraperitoneally at week 6, and the mice were sacrificed 1 week later.

Significantly different from intact mice by Student’s t test (P < 0.05) but not from TNF-α-treated SCID mice (P = 0.08).

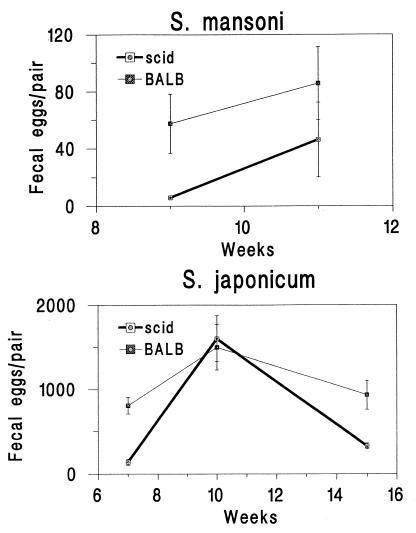

Almost no S. mansoni eggs were passed in the feces until week 11 of infection in SCID mice, but in S. japonicum-infected SCID mice, passage of eggs in the feces paralleled the accumulation of eggs in the tissues (Fig. 2). Recombinant TNF-α had no significant effect on passage of eggs in the feces of SCID mice infected with S. japonicum (Table 2) or S. mansoni (data not shown [no eggs were found in the feces of nine SCID mice examined 9 weeks after infection, 1 week after receiving 5 μg of TNF-α]).

FIG. 2.

Passage of eggs in the feces of S. mansoni- and S. japonicum-infected mice, expressed as eggs per worm pair per day. Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

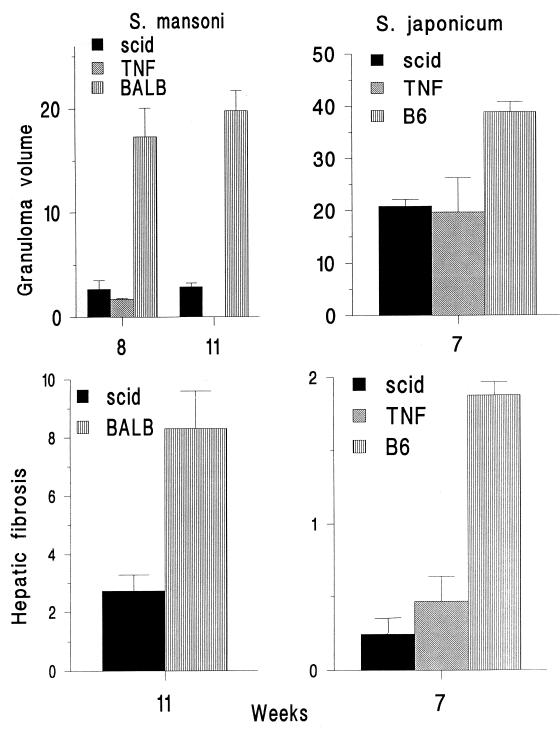

Granuloma size and hepatic fibrosis.

Hepatic granulomas around S. mansoni eggs were minute in SCID mice, only 10 to 15% of the volume of granulomas in intact mice. S. japonicum eggs elicited granulomas more than half the size of those in intact mice (Fig. 3). Granulomas in SCID mice were composed mainly of macrophages and cells resembling lymphocytes in S. mansoni infection and of macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells in S. japonicum infection. In contrast to BALB/c mice, where eosinophils were abundant, no eosinophils were present in the small lesions observed in SCID mice, either with or without TNF-α treatment. Hepatic fibrosis was slight in SCID mice infected with either S. mansoni or S. japonicum (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Injection of exogenous TNF-α did not significantly affect the volume of hepatic granulomas or the degree of hepatic fibrosis in SCID mice (Fig. 1 and 3; Table 2), in contrast to the results of Amiri et al. (1). TNF-α doses of 10 to 20 μg/mouse, lethal for many mice, had no effect on tissue eggs per worm pair or granuloma size in the surviving SCID mice (data not shown). Doses of 1 μg/mouse also had no effect.

FIG. 3.

Granuloma volume, in cubic millimeters (10−3), and hepatic fibrosis, shown as the increase above normal of hepatic hydroxyproline, expressed in micromoles per liver per 10,000 schistosome eggs, for S. mansoni- and S. japonicum-infected intact mice and SCID mice with and without TNF-α treatment. Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

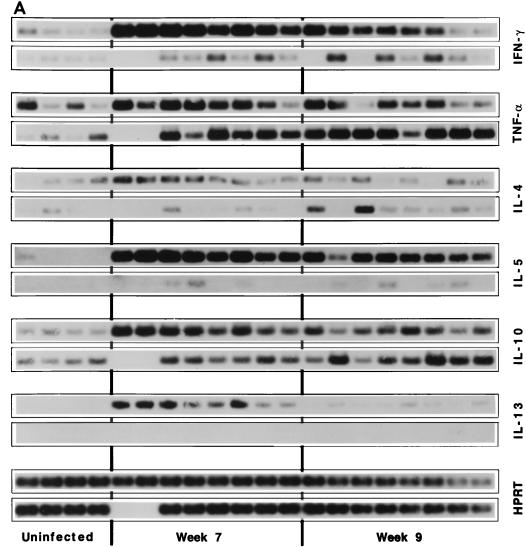

Hepatic and splenic cytokine levels in infected mice.

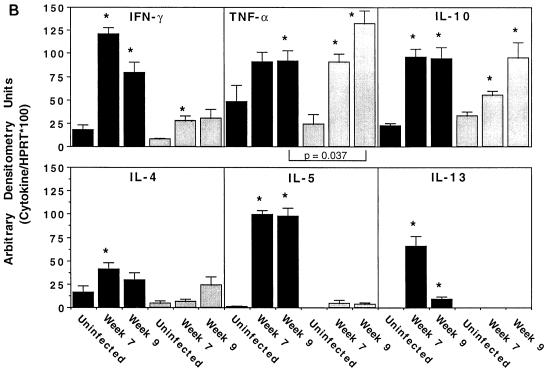

S. mansoni-infected BALB/c and CB17 SCID mice were sacrificed at 7 and 9 weeks postinfection, and the granulomatous livers were processed for cytokine mRNA analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, only BALB/c mice showed a significant increase in the expression of the Th2-associated cytokine mRNAs for IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Although IFN-γ mRNA expression was upregulated in both groups of mice, the BALB/c animals showed a more significant increase at both time points. Interestingly, however, the two groups of mice showed similar increases in TNF-α mRNA at 7 and 9 weeks postinfection, and IL-10 mRNA levels were also similar by week 9. In fact, the increase in TNF-α mRNA expression observed in infected SCID mice exceeded the levels observed in BALB/c mice on week 9.

FIG. 4.

SCID mice show little or no IL-4, IL-5, or IL-13 mRNA response but near-normal levels of TNF-α and IL-10 mRNAs in their granulomatous tissues. (A) BALB/c (top rows) and CB17 SCID (bottom rows) mice were infected with 25 cercariae of S. mansoni and then sacrificed 7 and 9 weeks postinfection to evaluate changes in the expression of several lymphokine mRNAs previously shown to be modulated during infection. mRNA levels were determined in the livers by RT-PCR, and the densitometric images of individual mice are presented. Results for HPRT, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 for four uninfected BALB/c and CB17 SCID mice, eight infected BALB/c mice at 7 and 9 weeks, and six CB17 SCID mice at week 7, and eight animals at week 9 postinfection are shown. (B) Average densitometric units ± SEM for the data presented in panel A. ∗, significantly different from the uninfected control group (P < 0.05); black columns, wild-type mice; gray columns, SCID mice. Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

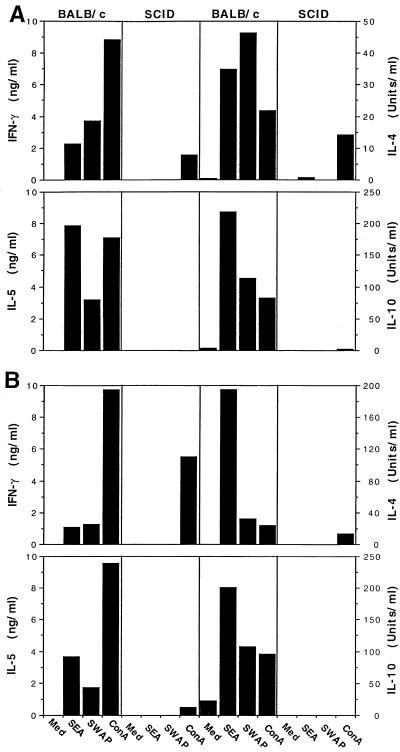

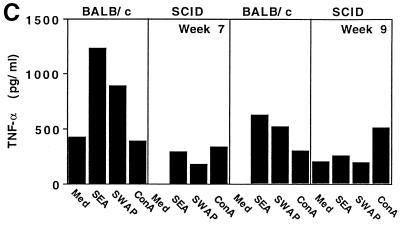

Spleen cell cultures were also processed and analyzed for the production of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and TNF-α protein. Similar to the hepatic cytokine mRNA results, BALB/c mice produced significant amounts IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10, and IFN-γ in response to SEA or SWAP restimulation in vitro on weeks 7 (Fig. 5A) and 9 (Fig. 5B) following infection. SCID mice, by contrast, produced no detectable antigen-specific cytokine response at either time point. There was, however, modest secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 in response to ConA stimulation at both time points in SCID animals. In contrast to the hepatic TNF-α mRNA results, splenocytes from SCID mice produced much less TNF-α than did cells obtained from BALB/c animals (Fig. 5C). The differences in protein versus mRNA expression, particularly for TNF-α and IL-10, likely reflect different cellular sources for these cytokines in both tissues, with CD4+ T cells being the major source in antigen-stimulated spleen cell cultures and macrophages plus T cells in the granulomatous tissues.

FIG. 5.

SCID mice fail to develop an antigen-specific cytokine response after infection with S. mansoni. BALB/c and CB17 SCID mice were infected with 25 cercariae of S. mansoni and then sacrificed at 7 and 9 weeks postinfection to evaluate cytokine secretion in the spleen. Individual (week 7; A) or pooled (week 9; B) single-cell suspensions from four to five animals per group were incubated in 24-well plates (3 × 106/well) and stimulated with medium (Med) alone, SEA at 20 μg/ml, SWAP at 50 μg/ml, or ConA at 5 μg/ml, as indicated. IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 (A and B) and TNF-α (C) levels were measured 72 h later as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars indicate 1 SEM.

DISCUSSION

Few S. mansoni or S. japonicum eggs were present in the tissues of SCID mice during the first weeks that eggs were being laid in intact mice, in agreement with previous reports on SCID (1) and T-cell-depleted (8) mice. However, egg accumulation in the tissues later equaled that in intact mice indicating, as in S. mansoni-infected nude mice (2), a delay in the inception of egg laying rather than a decrease in fecundity (1). We cannot definitively distinguish a delay in egg laying from decreased fecundity during the early period of egg laying, as we did not examine sufficient animals in the early days of patency. Normal fecundity is later established, perhaps as the result of accumulating small inflammatory lesions that provide the necessary stimulus, perhaps TNF-α, which was found to increase egg laying in vitro and in vivo in SCID mice by Amiri et al. (1). This effect was more pronounced in chronic S. japonicum infections, as the granulomas are larger and more numerous, but we were unable to investigate chronic S. mansoni infections in SCID mice.

The number of eggs in the feces of S. japonicum-infected SCID mice also became equivalent to that in intact mice at 10 weeks but was again lower at 15 weeks. In S. mansoni-infected mice, the number of eggs in the feces of SCID mice never equaled that in intact mice. In contrast to tissue eggs, which accumulate, fecal eggs reflect primarily the oviposition 1 week prior to collection of the feces and therefore indicate a probable continued deficit in egg passage in the feces of S. mansoni-infected SCID mice.

Our data on granuloma size and hepatic fibrosis reinforce the existing information indicating the T-cell dependence of these reactions (1, 2, 8). Interestingly, S. japonicum-infected SCID mice produced granulomas that were significantly larger than those observed in S. mansoni-infected animals. S. japonicum eggs contain factors chemotactic for neutrophils (15), and these might contribute to the larger size of granulomas around S. japonicum eggs in SCID and nude mice. More surprisingly, however, we were unable to affect granuloma size or hepatic fibrosis with exogenous recombinant TNF-α. This is in contrast to the findings of Amiri et al. for S. mansoni-infected CB17 SCID mice (1), which are supported by the results of Joseph and Boros (9) for assays using polyclonal anti-TNF-α antibody in intact mice. Amiri et al. showed that injection of purified recombinant TNF-α led to a dose-dependent formation of granulomas around schistosome eggs (1). These TNF-α-induced granulomas were characterized by the recruitment of fibroblasts and deposition of collagen fibers within the granuloma, suggesting that a relatively normal host response was reconstituted by injection of TNF-α alone.

We cannot explain the difference between our data and those of Amiri et al. (1). CB17 SCID mice were used by both laboratories. The recombinant TNF-α was from the same source, and our TNF-α was potent when assayed on L929 fibroblasts in vitro. Indeed, when used at the highest doses, we observed significant mortality, which was attributed to the toxic affects of the injected TNF-α. The S. mansoni strains were different, and Amiri et al. injected 55 to 60 cercariae subcutaneously whereas we applied 25 to 30 cercariae percutaneously. These differences seem unlikely explanations, as the granulomatous responses in immunologically intact mice were similar and adult egg-laying schistosome pairs were established in both laboratories.

Surprisingly, we observed nearly equivalent levels of TNF-α mRNA in the livers of infected BALB/c and CB17 SCID mice, which suggests that there is in fact little or no deficit in TNF-α expression in the infected immunodeficient animals at the time points we examined. There was, however, less TNF-α in antigen-stimulated spleen cell cultures. Nevertheless, the latter in vitro data are likely less reflective of the in vivo situation since TNF-α is predominantly a macrophage-derived cytokine. We did not examine tissue cytokine levels at a time when worms in SCID mice were not producing eggs while those in intact mice were (weeks 5 to 6). Thus, it is possible that the delay in fecundity is due to a delay in tissue produced TNF-α in SCID mice. The deficit in granuloma formation in SCID mice did correlate with a profound decrease in Th2-type cytokine expression, which is consistent with the well-established role of Th2 cytokines in schistosomiasis pathogenesis (6, 10, 18). Interestingly, the cytokines missing from the SCID granulomas were those typically associated with Th2 cells, while TNF-α, IL-10, and to a lesser extent IFN-γ, which can be derived from cells of the innate immune response, were upregulated to highly significant levels in both infected SCID and intact mice. Thus, the presence of Th2-associated cytokines provides the strongest correlation for a maximal granulomatous response. In conclusion, our data provide little evidence that TNF-α alone is necessary or sufficient to restore either the fecundity of S. mansoni or S. japonicum or the egg-induced pathology of schistosomiasis in SCID mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S. japonicum-infected snails were provided by Yung-San Liang through a contract with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and S. mansoni cercariae were provided by Fred Lewis, Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, Md. We thank Jacqueline Little and Richard Asofsky for advice on conditions for the IgM assay, Pat Caspar for performing the IL-4 bioassays, and Genentech Inc. for providing the recombinant murine TNF-α.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiri P, Locksley R M, Parslow T G, Sadick M, Rector E, Ritter D, McKerrow J H. Tumour necrosis factor alpha restores granulomas and induces parasite egg-laying in schistosome-infected SCID mice. Nature. 1992;356:604–607. doi: 10.1038/356604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Cheever, A. W. Unpublished data.

- 2.Cheever A W, Eltoum I A, Andrade Z A, Cox T M. Biology and pathology of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum infections in several strains of nude mice. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:496–503. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheever A W, Macedonia J G, Mosimann J E, Cheever E A. Kinetics of egg production and egg excretion by Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum in mice infected with a single pair of worms. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:281–295. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheever A W, Williams M E, Wynn T A, Finkelman F D, Seder R A, Hieny S, Caspar P, Sher A. Anti-IL-4 treatment of Schistosoma mansoni-infected mice inhibits development of T cells and non-B, non-T cells expressing Th2 cytokines while decreasing egg-induced hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol. 1994;153:753–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chensue S W, Warmington K S, Hershey S D, Terebuh P D, Othman M, Kunkel S L. Evolving T cell responses in murine schistosomiasis. Th2 cells mediate secondary granulomatous hypersensitivity and are regulated by CD8+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 1993;151:1391–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiaramonte M G, Schopf L R, Neben T Y, Cheever A W, Donaldson D D, Wynn T A. IL-13 is a key regulatory cytokine for Th2 cell-mediated pulmonary granuloma formation and IgE responses induced by Schistosoma mansoni eggs. J Immunol. 1999;162:920–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duvall R H, Dewitt W B. An improved perfusion technique for recovering adult schistosomes from laboratory animals. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1967;6:483–488. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1967.16.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison R A, Doenhoff M J. Retarded development of Schistosoma mansoni in immunosuppressed mice. Parasitology. 1983;86:429–438. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000050629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph A L, Boros D L. Tumor necrosis factor plays a role in Schistosoma mansoni egg-induced granulomatous inflammation. J Immunol. 1993;151:5461–5471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan M H, Whitfield J R, Boros D L, Grusby M J. Th2 cells are required for the Schistosoma mansoni egg-induced granulomatous response. J Immunol. 1998;160:1850–1856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litt M. Studies in experimental eosinophilia. V. Eosinophils in lymph nodes of guinea pigs following primary antigenic stimulation. Am J Pathol. 1963;42:529–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lukacs N W, Boros D L. Lymphokine regulation of granuloma formation in murine schistosomiasis masoni. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;68:57–63. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathew R C, Boros D L. Anti-L3T4 antibody treatment suppresses hepatic granuloma formation and abrogates antigen-induced interleukin-2 production in Schistosoma mansoni infection. Infect Immun. 1986;54:820–825. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.820-826.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murare H M, Dunne D W, Bain J, Doenhoff M J. Schistosoma mansoni: control of hepatotoxicity and egg excretion by immune serum in infected immunosuppressed mice is schistosome species-specific, but not S. mansoni strain-specific. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owhashi M, Horii Y, Ishii A. Schistosoma japonicum: identification and characterization of neutrophil chemotactic factors from egg antigen. Exp Parasitol. 1985;60:229–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(85)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips S M, DiConza J J, Gold J A, Reid W A. Schistosomiasis in the congenitally athymic (nude) mouse. I. Thymic dependency of eosinophilia, granuloma formation, and host morbidity. J Immunol. 1977;118:594–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Lichtenberg F, Erickson D G, Sadun E H. Comparative histopathology of schistosome granulomas in the hamster. Am J Pathol. 1973;72:149–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wynn T A, Cheever A W. Cytokine regulation of granuloma formation in schistosomiasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:505–511. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wynn T A, Eltoum I, Cheever A W, Lewis F A, Gause W C, Sher A. Analysis of cytokine mRNA expression during primary granuloma formation induced by eggs of Schistosoma mansoni. J Immunol. 1993;151:1430–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wynn T A, Eltoum I, Oswald I P, Cheever A W, Sher A. Endogenous interleukin 12 (IL-12) regulates granuloma formation induced by eggs of Schistosoma mansoni and exogenous IL-12 both inhibits and prophylactically immunizes against egg pathology. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1551–1561. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]