Abstract

Fusarium species are commonly found in soil, water, plants, and animals. A variety of secondary metabolites with multiple biological activities have been recently isolated from Fusarium species, making Fusarium fungi a treasure trove of bioactive compounds. This mini-review comprehensively highlights the newly isolated secondary metabolites produced by Fusarium species and their various biological activities reported from 2019 to October 2024. About 276 novel metabolites were revealed from at least 21 Fusarium species in this period. The main metabolites were nitrogen-containing compounds, polyketides, terpenoids, steroids, and phenolics. The Fusarium species mostly belonged to plant endophytic, plant pathogenic, soil-derived, and marine-derived fungi. The metabolites mainly displayed antibacterial, antifungal, phytotoxic, antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activities, suggesting their medicinal and agricultural applications. This mini-review aims to increase the diversity of Fusarium metabolites and their biological activities in order to accelerate their development and applications.

Keywords: secondary metabolites, nitrogen-containing metabolites, polyketides, terpenoids, Fusarium fungi, biological activities, plant pathogenic fungi, plant endophytic fungi, marine-derived fungi, soil-derived fungi

1. Introduction

Fusarium is a widely distributed group of filamentous ascomycetes belonging to Sordariomycetes, Hypocreales, and Nectriaceae [1]. Some Fusarium species are among the most important toxigenic plant pathogenic fungi to infect crops such as wheat, barley, oats, rice, maize, potato, asparagus, mango, banana, grasses, and other food and feed grains. The toxic metabolites (or called mycotoxins) produced by pathogenic Fusarium fungi have been considered the main pathogenic factors. The consumption of these mycotoxin-contaminated foods may induce acute and long-term chronic diseases in humans and animals [2,3,4].

In addition to phytopathogenic Fusarium fungi that produce mycotoxins, it has been revealed that Fusarium fungi can grow on a wide range of substrates and are commonly found in soil, water, plants, and animals either on the continent or in the ocean. They have a variety of secondary metabolites with multiple biological activities that make Fusarium fungi a treasure trove of bioactive compounds [5,6]. Therefore, studies on the secondary metabolites of Fusarium fungi and their biological activities have always received much attention [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Over the past decades, many significant advances, such as the identification of bioactive metabolites [14,15,16], mycotoxins and their detoxification [2,17,18], biosynthesis and regulation [19,20], and development and applications [21,22] of Fusarium secondary metabolites, have been achieved. Fusarium metabolites and their biological activities have been well-reviewed up to 2019 [11,14,15,16,23]. Since then, many newly isolated metabolites have been identified in Fusarium fungi. In this mini-review, we focus on the recently identified novel secondary metabolites, along with their biological activities reported from 2019 to October 2024, to increase the diversity of Fusarium metabolites and their biological activities as well as to speed up their development and applications.

2. Nitrogen-Containing Metabolites and Their Biological Activities

The nitrogen-containing metabolites from Fusarium fungi mainly include amines, amides, cyclic peptides, pyridines, pyridones, and indole and imidazole analogs. The nitrogen-containing metabolites and their biological activities along with Fusarium species and their origins are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

New nitrogen-containing metabolites (1–97) isolated from Fusarium fungi and their biological activities.

| Metabolite Class |

Metabolite Name | Biological Activity |

Fusarium Species |

Fungal Origin |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amines | |||||

| 2-Amino-14,16-dimethyloctadecan-3-ol (1) | Cytotoxic activity | F. avenaceum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [24] | |

| Deacetyl fusarochromene (2); 4′-O-acetyl fusarochromanone (3) | Antimalarial activity | Fusarium sp. | Entomogenous fungus | [25] | |

| Deacetamidofusarochrom-2′,3′-diene (4) | Cytotoxic and antibacterial activities | F. equiseti | Marine-derived fungus | [26] | |

| Amides | |||||

| Decalintertracids A (5/6) and B (7/8) | Phytotoxic activity | F. equiseti | Plant endophytic fungus | [27] | |

| (3E,7E)-11,12-Dihydroxy-4,8,12-trimethyltrideca-3,7-dienamide (9) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [28] | |

| (S,E)-Methyl-2-(2,4-dimethylhex-2-enamido)acetate (10) | - | F. oxysporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [29] | |

| DihydroNG393 (11); dihydrolucilactaene (12); 13α-hydroxylucilactaene (13) | Antimalarial activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [30] | |

| Fusaindoterpene A (14) | - | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [31] | |

| Fusaramin (15) | Antibacterial and antimitochondrial activities | Fusarium sp. | Soil-derived fungus | [32] | |

| Fusarin L (16) | Anti-inflammatory activity | F. solani | Marine-derived fungus | [33] | |

| Furarin X1 (17) | Cytotoxic activity | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [34] | |

| Fusarisetin B (18) | Cytotoxic activity | F. equiseti | Entomogenous fungus | [35] | |

| Fusarisetins C (19) and D (20) | - | F. equiseti | Marine-derived fungus | [36] | |

| Fusaribenzamide A (21) | Antifungal activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [37] | |

| Fusarochromene (22) | - | F. sacchari | Plant pathogenic fungus | [38] | |

| Kaneoheoic acid G (23) | Antibacterial activity | F. graminearum | Marine-derived fungus | [39] | |

| 8(Z)-Lucilactaene (24); 4(Z)-lucilactaene (25) | Anti-inflammatory activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [40] | |

| N-({4-[(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)oxy]phenyl}acetyl)glycine (26); methyl N-({4-[(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)oxy]phenyl}acetyl)glycinate (27) | - | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [41] | |

| Prelucilactaenes G (28) and H (29) | Antimalarial activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [42] | |

| Proliferatins A–C (30–32) | Anti-inflammatory activity | F. proliferatum | Fungal stroma-derived fungus | [43] | |

| Pyrrolidinone analogs 33, 34, and 35 | - | F. decemcellulare | Plant endophytic fungus | [44] | |

| Cyclic peptides | |||||

| Acuminatums E (36) and F (37) | Antifungal activity | F. lateritium | Plant endophytic fungus | [45] | |

| Amoenamide C (38); sclerotiamide B (39) | Antimicrobial and larvicidal activities | F. sambucinum | Plant endophytic fungus | [46] | |

| Apicidin L (40) | Cytotoxic and antimalarial activities | F. fujikuroi | Plant pathogenic fungus | [47] | |

| Beauvervin H (41) | Cytotoxic activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [48] | |

| Beauvericins M (42) and N (43) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [49] | |

| Cyclo-(L-Trp-L-Phe-L-Phe) (44) | Cytotoxic and antibacterial activities | F. proliferatum | Plant endophytic fungus | [50] | |

| Enniatin W (45) | Cytotoxic activity | F. oxysporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [51] | |

| Fusahexin (46) | - | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [52] | |

| Fusaristatins D–F (47–49) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [53] | |

| Gramipiperazines A (50) and B (51) | Antibacterial activity | F. graminearum | Marine-derived fungus | [39] | |

| Pyridines | |||||

| Climacomontaninate D (52) | - | Fusarium sp. | Entomogenous fungus | [54] | |

| Fusaricates H–K (53–56) | - | F. solani | Mangrove-derived fungus | [55] | |

| Fasaripyridines A (57) and B (58) | Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [56] | |

| Pyridones | |||||

| Fusapyridons C (59) and D (60) | Cytotoxic activity | F. avenaceum | Entomopathogenic fungus | [57] | |

| Fusarone A (61) | Cytotoxic and antibacterial activities | F. proliferatum | Plant endophytic fungus | [50] | |

| 1′-Methoxy-6′-epi-oxysporidinone (62) | - | F. concentricum | Plant endophytic fungus | [58] | |

| Indole analogs | |||||

| Chlamydosporin (63) | Phytotoxic activity | F. chlamydosporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [59] | |

| Ethyl 3-indoleacetate (64) | Cytotoxic and antibacterial activities | F. proliferatum | Plant endophytic fungus | [50] | |

| Fusaconate A (65) | - | F. concentricum | Plant endophytic fungus | [58] | |

| Fusarindoles A–E (66–70) | - | F. equiseti | Marine-derived fungus | [60] | |

| (+)-Fusaspoid A (71); (−)-fusaspoid A (72) | - | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [61] | |

| Fusaindoterpene B (73); fusarindoles A–C (74–76); isoalternatine A (77) | Inhibitory activity against Zika virus | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [31] | |

| Imidazole analogs | |||||

| Fusaritricines A–I (78–86) | Antibacterial activity | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [62] | |

| (+)-Fusaritricine J (87), (−)-fusaritricine J (88), and fusaritricines K–P (89–94) | Antibacterial activity | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [63] | |

| Others | |||||

| Fusaravenin (95) | - | F. avenaceum | Soil-derived fungus | [64] | |

| Fusaroxazin (96) | Cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities | F. oxysporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [65] | |

| Secobeauvericin A (97) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [49] | |

2.1. Amines

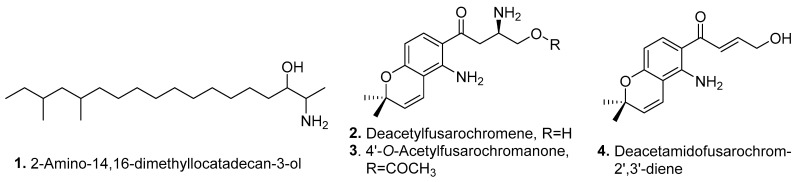

Four new amines (1–4) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of the amines (1–4) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

2-Amino-14,16-dimethyloctadecan-3-ol (2-AOD-3-ol, 1) was characterized as a new sphingolipid analog isolated from the plant pathogen F. avenaceum. 2-AOD-3-ol (1) showed moderate cytotoxic activity against HepG2 cells [24].

Two fusarochromenes, namely, deacetylfusarochromene (2) and 4′-O-acetylfusarochromanone (3), were isolated from the entomogenous fungus Fusarium sp. FKI-9521 derived from the feces of a stick insect Ramulus mikado. Both compounds showed moderate antimalarial activity against chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains, with the median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values ranging from 0.08 to 6.35 µM [25]. Deacetyl fusarochromene (2) was also isolated from the marine fungus F. equiseti UBOCC-A-117302 and showed obviously cytotoxic activities on RPE-1, HCT-116, and U2OS cells, with IC50 values of 0.176, 0.087, and 0.896 μM, respectively [26].

Another fusarochromanone, namely, deacetamidofusarochrom-2′,3′-diene (4), was isolated from the marine fungus F. equiseti UBOCC-A-117302, which was derived from a seawater sample collected in the coastal region of Chile. Deacetamidofusarochrom-2′,3-diene (4) showed antibacterial activity against Listeria monocytogenes, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 125 μM, and also exhibited cytotoxic activities on RPE-1, HCT-116, and U2OS cells with IC50 values of 10.03, 13.73, and 13.18 μM, respectively [26].

2.2. Amides

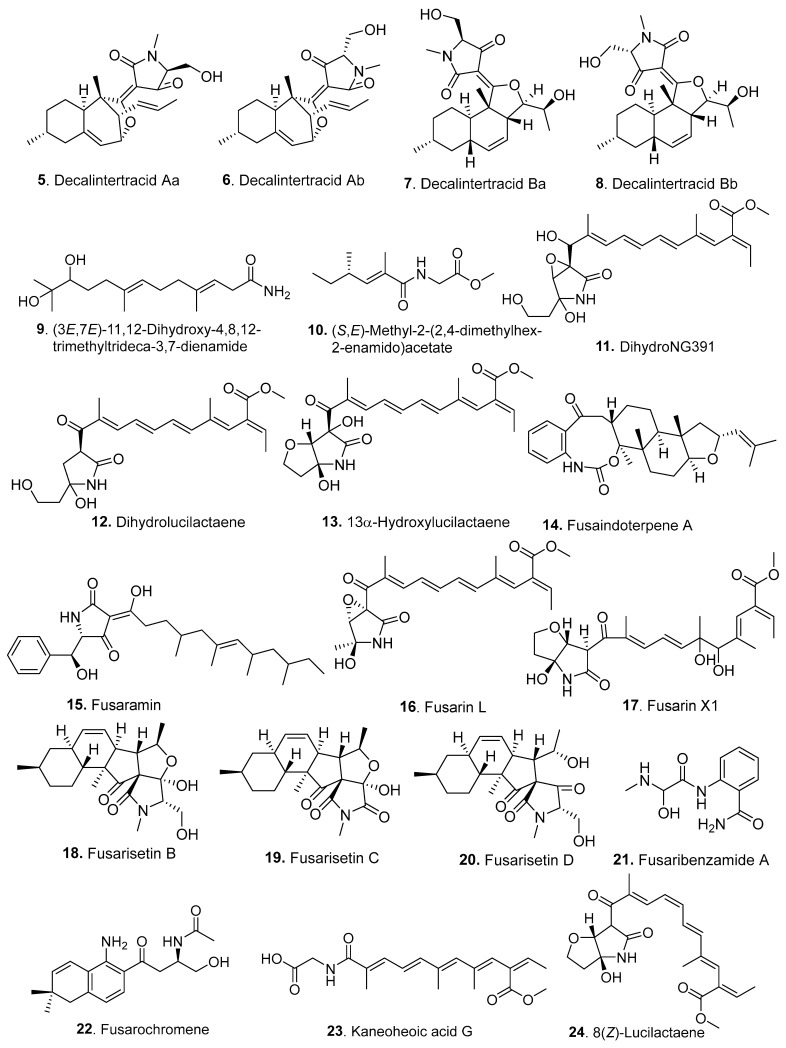

Thirty-one new amides (5–35) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, with their structures shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structures of the amides (5–35) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Decalintertracids A (5/6) and B (7/8) were two pairs of 3-decalinoyltetramic acid E/Z diastereomers (3DTAs), namely, decalintertracids Aa (5), Ab (6), Ba (7), and Bb (8). They were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. equiseti D39 derived from Suaeda salsa (Chenopodiaceae) collected in Qingdao, China. Decalintetracid A (5/6) was isolated as an inseparable mixture of two isomers with a ratio of 5:3. Although HPLC analysis of decalintetracid A (5/6) through both ODS and chiral column showed that it afforded a baseline separation of the two isomers, the attempts to separate them failed due to spontaneous isomerization between the two compounds. The two isomers have the same molecular formula of C22H29NO4. Similarly, decalintetracid B (7/8) was also obtained as a pair of inseparable isomers with a ratio of 5:3 and was determined to have the same molecular formula C22H32NO5 based on the HRESIMS data. Both compounds exhibited phytotoxic activity toward Amaranthus retroflexus and A. hybrid, indicating their potential as natural herbicides [27].

One sesquiterpene-derived amide, namely, (3E,7E)-11,12-dihydroxy-4,8,12-trimethyltrideca-3,7-dienamide (9), was isolated from plant endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. HJT-P-2, which was isolated from Rhodiola angusta (Crassulaceae) on Changbai Mountain, Jilin Province, China [28].

(S,E)-Methyl-2-(2,4-dimethylhex-2-enamido)acetate (10) is an amide isolated from the co-culture of two endophytic fungal species, F. oxysporum R1 and Aspergillus fumigatus D, derived from two traditional medicinal plants, Edgeworthia chrysantha Lindl. (Thymelaeaceae) and Rumex madaio Makino (Polygonaceae), respectively [29].

Three amides (11–13) were isolated from the cultures of Fusarium sp. RK97-94 treated with the metabolism regulator NPD938. The endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. RK97-94 was previously isolated from the leaves of an unidentified plant collected at Mt. Inasa, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. Three amides were identified as dihydroNG391 (11), dihydrolucilactaene (12), and 13α-hydroxylucilactaene (13) and showed antimalarial activities against Plasmodium falciparum, with IC50 values of 62 μM, 0.0015 μM, and 0.68 μM, respectively. The structure–activity relationship (SAR) showed that the epoxide was highly detrimental to antimalarial activity [30].

Fusaindoterpene A (14) was isolated from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. L1, which was isolated from the inner tissue of the sea star Acanthaster planci collected from the Xisha Islands in China [31].

Fusaramin (15) was isolated from the soil-derived fungus Fusarium sp. FKI-7550. Fusaramin (15) showed antibacterial activity against some Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and decreased the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae through the inhibition of ATP synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria [32].

Fusarin L (16) was isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. solani 7227, which was isolated from a seawater sample collected in the South China Sea [33].

Fusarin X1 (17) was a hybrid of polyketide with non-ribosomal peptide, which was isolated from the Fusarium head blight pathogen F. graminearum. Fusarin X1 (17) showed moderate cytotoxic activity against three tumor cell lines [34].

Fusarisetin B (18) was isolated from the entomogenous fungus F. equiseti LGWB-9, isolated from Harmonia axyridis (Coccinellidae). Fusarisetin B (18) showed cytotoxicity against MCF-7, MGC-803, HeLa, and Huh-7 cell lines, with the IC50 values ranging from 2.4 to 69.7 μg/mL. Cell invasion, migration, DAPI staining, and flow cytometry experiments were carried out to examine the effects of fusarisetin B (18) on MGC-803 cells. Western blot results showed that fusarisetin B (18) could induce MGC-803 apoptosis through the up-regulation of Bax and down-regulation of Bcl-2 [35].

Fusarisetins C (19) and D (20) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. equiseti D39, which was from a piece of fresh tissue obtained from the inner part of an unidentified plant collected from the intertidal zone of the Yellow Sea, Qingdao, China. Fusarisein D (20) was identified as the first fusarisetin to possess an unprecedented carbon skeleton with a tetracyclic ring system comprising a decalin moiety (6/6) and a tetramic acid moiety [36].

An aminobenzamide derivative, namely, fusaribenzamide A (21), was isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. isolated from the roots of Mentha longifolia (Labiatae). Fusaribenzamide A (21) possessed significant antifungal activity toward Candida albicans, with a higher minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 11.9 μg/disc compared to the positive control nystatin (MIC, 4.9 μg/disc) [37].

Fusarochromene (22) was isolated from plant pathogenic fungus F. sacchari. It was considered a tryptophan-derived metabolite [38].

Kaneoheoic acid G (23) was isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. graminearum FM1010, which was isolated from shallow-water volcanic rock known as “live rock” at Richardson’s Beach, Hilo, Hawaii. Biogenetically, kaneoheoic acid G (23) could be catalyzed by NRPS-PKS. Kaneoheoic acid G (23) showed strong antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus [39].

Two photosensitive geometrical isomers 8(Z)-lucilactaene (24) and 4(Z)-lucilactaene (25) of lucilactaene were isolated from Fusarium sp. QF001, a plant endophytic fungus from the roots of Scutellariae baicalensis (Labiatae). Both compounds showed anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting NO production and suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells [40].

Two prenylated glycine derivatives, namely, N-({4-[(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)oxy]phenyl}acetyl)glycine (26) and methyl N-({4-[(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)oxy]phenyl}acetyl)glycinate (27), were isolated from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. TW56-10, which was derived from hydrothermal vent sediment collected in Kueishantao, Taiwan [41].

Prelucilactaenes G (28) and H (29) were isolated from Fusarium sp. RK97-94 and showed antimalarial activity [42].

Froliferatins A (30), B (31), and C (32) were isolated from the stroma-derived fungus F. proliferatum isolated from Cordycep sinensis. The three metabolites (30–32) all showed anti-inflammatory activity by suppressing lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation via inhibition of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [43].

Three unnamed pyrrolidinone analogs 33–35 were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. decemcellualre F25, which was derived from the stems of the medicinal plant Mahonia fortunei (Berberidaceae) collected in Qindao, China [44].

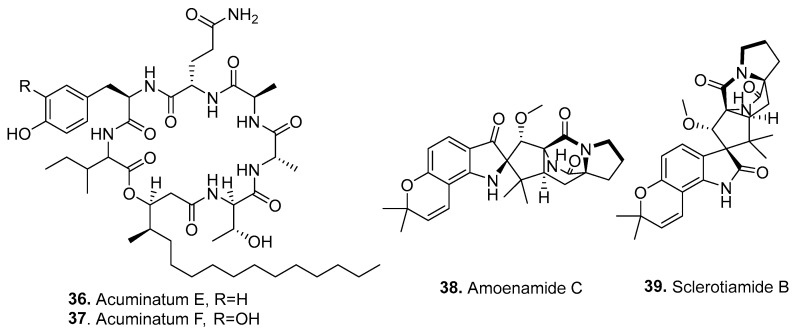

2.3. Cyclic Peptides

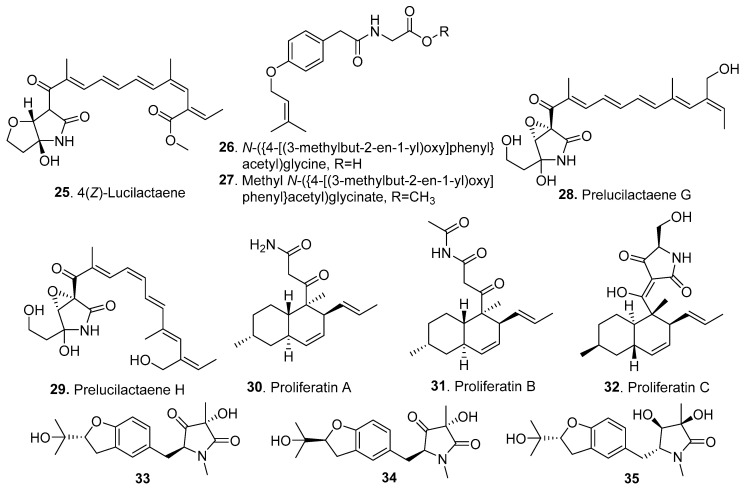

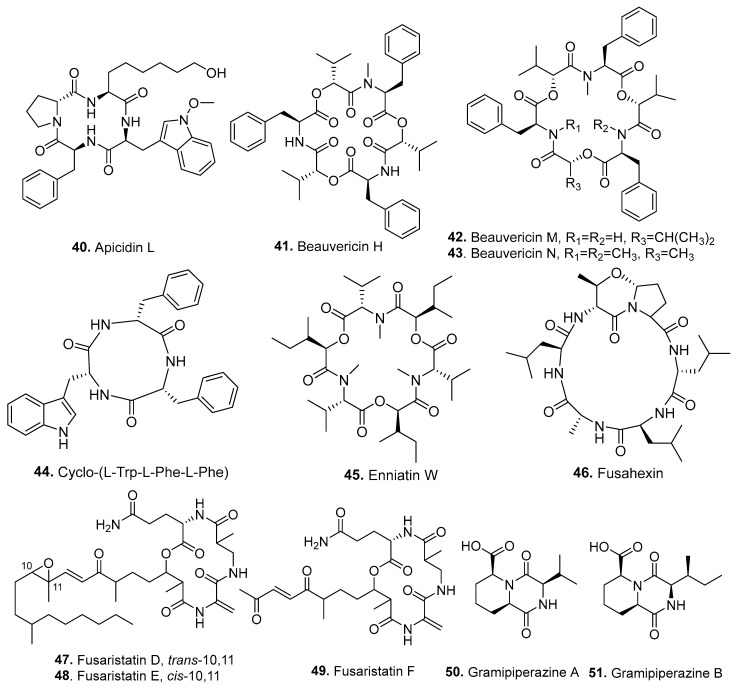

Cyclic peptides are cyclic compounds formed mainly by the amide bonds between either proteinogenic or non-proteinogenic amino acids. Some fungal cyclic peptides are called cyclic depsipeptides, in which the corresponding lactone bonds replace amide groups due to the presence of a hydroxylated carboxylic acid in the peptide structure. Fifteen new amines (36–51) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, with their structures shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structures of the cyclic peptides (36–51) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Two cyclic lipopeptides acuminatums, E (36) and F (37), were isolated from a corn culture of endophytic F. lateritium HU0053 derived from Adenanthera pavonlna (Leguminosae). Their structures were elucidated by spectroscopy and advanced Marfey’s amino acid analysis. All compounds exhibited antifungal activities against Penicillium digitatum. Acuminatum F (37), containing an unusual 3, 4-dihydroxy-phenylalanine unit, displayed the strongest antifungal activities, with an inhibition zone of 6.5 mm at a dose of 6.25 μg. Acuminatum F (37) may be a potential environmentally friendly preservative for citrus fruits [45].

Two cyclodipeptides containing an angularly prenylated indole moiety, namely, amoenamide C (38) and sclerotiamide B (39), were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. sambucinum TE-6L residing in Nicotiana tabacum (Solanaceae). Both compounds showed potent inhibitory effects on pathogenic bacteria and fungi. In addition, sclerotiamide B (39) exhibited remarkable larvicidal activity against first-instar larvae of the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera), with a mortality rate of 70.2% [46].

Apicidin L (40) was a cyclic tetrapeptide isolated from the rice pathogen F. fujikuroi IMI58289. The cytotoxic effects of apicidin L (40) were tested on three different cell lines. Cytotoxic effects were exhibited only at high concentrations in rat myoblast cells, with an IC50 value of 20 μM. In addition, apicidin L (40) exhibited in vitro antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum, with an IC50 value of 2.1 μM [47].

Beauvericin H (41) is a cyclic hexadepsipeptide isolated from the ethanol extract of a solid culture of the plant endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. DCJ-A. Beauvericin H (41) and known isolated cyclic hexadepsipeptides exhibited cytotoxic activities against five human cancer cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 1.379 to 13.12 μM [48].

Two cyclic hexadepsipeptides, namely, beauvericins M (42) and N (43), were isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp., which was derived from the stem of a tea plant (Camelia sinensis) [49].

One cyclo-tripeptide, namely, cyclo-(L-Trp-L-Phe-L-Phe) (44), was isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. proliferatum T2-10 and showed cytotoxic and antibacterial activities [50].

One cyclic hexadepsipeptide, namely, enniatin W (45), was isolated from the endophytic fungus F. oxysporum LHS-P1-3 from the roots of Arachis hypogaea (Leguminosae). Enniatin W (45) exhibited cytotoxic activity against tumor cells of HepG2 and HeLa lines [51].

The overexpression of the NRPS4 gene in the plant pathogenic fungus F. graminearum led to the discovery of a new cyclic hexapeptide, fusahexin (46), with the amino acid sequence cyclo-(D-Ala-L-Leu-D-allo-Thr-L-Pro-D-Leu-L-Leu) [52].

Three lipodepsipeptides, fusaristatins D (47), E (48), and F (49), were obtained from the solid rice cultures of Fusarium sp. BZCB-CA, an endophytic fungus derived from the Chinese medicinal plant Bothriospermum chinense (Boraginaceae) [53].

Two diketopiperazines, namely, gramipiperazines A (50) and B (51), were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. graminearum FM1010, which was isolated from shallow-water volcanic rock known as “live rock” at Richardson’s Beach, Hilo, Hawaii. Biogenetically, gramipiperazine A (50) should be derived from 2-amino-5-hydroxyadipic acid and valine, and gramipiperazine B (51) should be derived from 2-amino-5-hydroxyadipic acid and isoleucine. Gramipiperazine B (51) showed weak antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus [39].

2.4. Pyridines

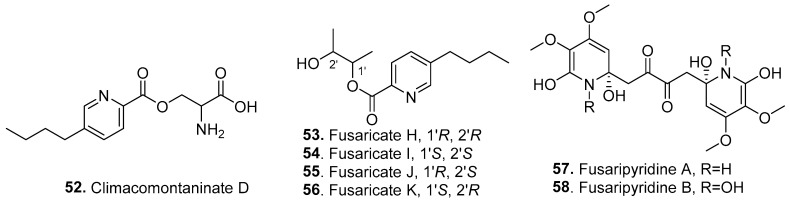

Seven new pyridine analogs (52–58) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, with their structures shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Structures of the pyridines (52–58) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Climacomontaninate D (52) was isolated from the entomogenous fungus Fusarium sp. LGWB-7 from Harmonia axyridis [54].

Four fusaric acid derivatives, fusaricates H (53), I (54), J (55), and K (56), were isolated from the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus F. solani HDN15-410, which was isolated from the roots of Rhizophora apiculata Blume (Rhizophoraceae) [55].

Two dimeric pyridine derivatives, fasaripyridines A (57) and B (58), were identified from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. LY019, which was obtained from the sponge Suberea mollis in the Red Sea. Both compounds possessed a previously unreported moiety, 1,4-bis(2-hydroxy-1,2-dihydropyridin-2-yl)butane-2,3-dione. They selectively inhibited the growth of Candida albicans with MIC values of 8.0 μM, while they were moderately active against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and HeLa cells [56].

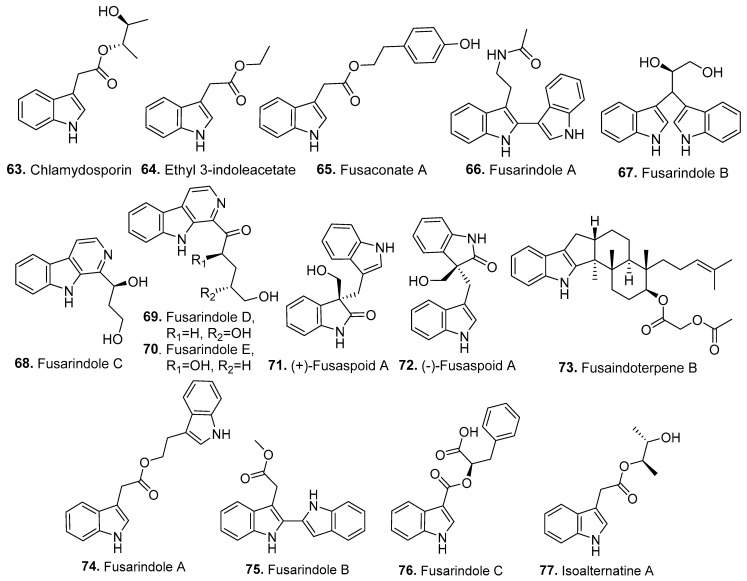

2.5. Pyridones

Four new pyridones (59–62) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Structures of the pyridines (59–62) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Two tricyclic pyridone analogs, fusapyridons C (59) and D (60), were isolated from the entomopathogenic fungus F. avenaceum SYKC02-P-1. Both compounds showed inhibitory activity against human prostate cancer cells (PC-3 cell line) [57].

Fusarone A (61) was a 2-pyridone derivative isolated from the endophytic fungus F. proliferatum T2-10. Fusarone A (61) showed cytotoxic and antibacterial activities [50].

One pyridine derivative, 1′-methoxy-6′-epi-oxysporidinone (62), was isolated from the endophytic fungus F. concentricum, which was derived from the medicinal plant Anoectochilus roxburghii (Orchidaceae) [58].

2.6. Indole Analogs

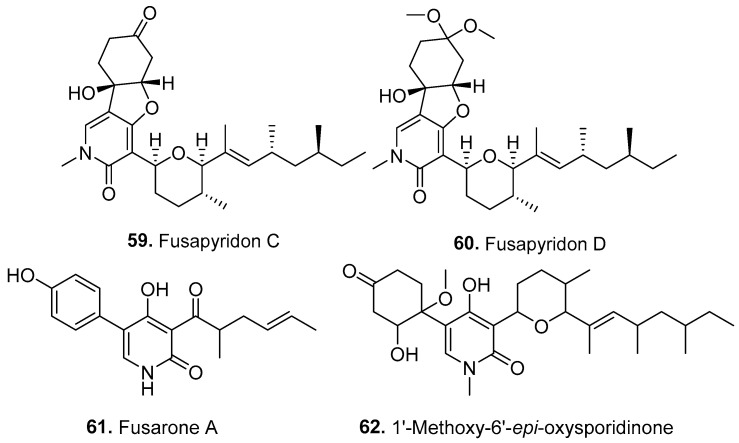

Fifteen new indole analogs (63–77) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Structures of the indole analogs (63–77) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Chlamydosporin (63) was isolated from F. chlamydosporum derived from the roots of Suaeda glauca (Chenopodiaceae). Chlamydosporin (63) showed significant phytotoxic activity against the radicle growth of Echinochloa crusgalli (Gramineae) seedlings [59].

Ethyl 3-indoleacetate (64) is an indole derivative isolated from the endophytic fungus F. proliferatum T2-10. It showed cytotoxic and antibacterial activities [50].

Fusaconate A (65) is a tryptophan derivative isolated from the endophytic fungus F. concentricum, which was derived from the medicinal plant Anoectochilus roxburghii (Orchidaceae) [58].

Five indole analogs, namely, fusarindoles A (66), B (67), C (68), D (69), and E (70), were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. equiseti LJ-1, which was derived from the soft coral Sarcophyton tortuosum collected in the South China Sea [60].

A pair of novel bisindole alkaloid enantiomers, namely, (+)-fusaspoid A (71) and (−)-fusaspoid A (72), was isolated from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. XBB-9, which was isolated from Hainan Sanya National Coral Reef Reserve in China [61].

Fusaindoterpene B (73), fusariumindoles A–C (74–76), and isoalternatine A (77) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. L1, which was isolated from the inner tissue of a sea star Acanthaster planci collected from the Xisha Islands in China. Among the compounds, fusaindoterpene B (73) displayed the strongest inhibitory activity against the Zika virus (ZIKV) in a standard plaque assay, with an IC50 value of 7.5 μM [31].

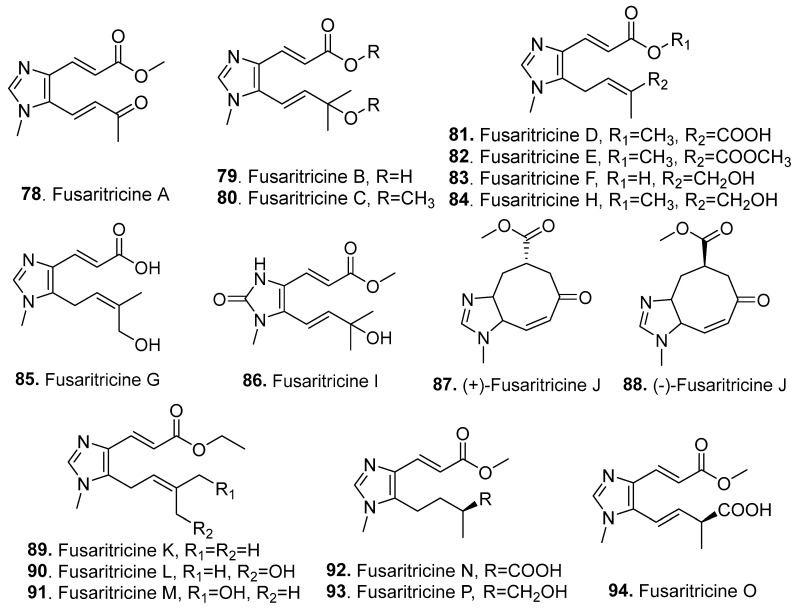

2.7. Imidazole Analogs

Seventeen new imidazole analogs (78–94) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Structures of the imidazole analogs (78–94) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Nine imidazole derivatives, namely, fusaritricines A–I (78–86), were isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. tricinctum, which was derived from kiwi (Actinidia chinensis) plants (Actinidiaceae). Among these imidazole analogs, fusaritricines B (79), C (80), and I (86) showed strong antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), with MIC values ranging from 25 to 50 μg/mL [62]. Another eight imidazole derivatives, namely, (+)-fusaritricine J (87), (−)-fusaritricine J (88), and fusaritricines K–P (89–94) were further isolated from F. tricinctum. Among these compounds, (+)-fusaritricine J (87), (−)-fusaritricine J (88), fusaritricines M (91) and N (92) showed comparably strong antibacterial activities against Psa, with MIC values of 25–50 μg/mL. Further cell membrane permeability results suggested that the most active fusaritricine M (91) could destroy the bacterial cell wall structure [63]. These imidazole derivatives were only found in the genus Fusarium and showed strong antibacterial activity, which indicated that the imidazole derivatives may have applications as potential antibacterial agents. The endophytic fungus F. tricinctum could also be considered a biocontrol agent for managing the kiwi fruit canker disease. In addition, the physiological, ecological, and chemotaxonomic significance of imidazole derivatives, as well as their biosynthesis, should be studied in detail.

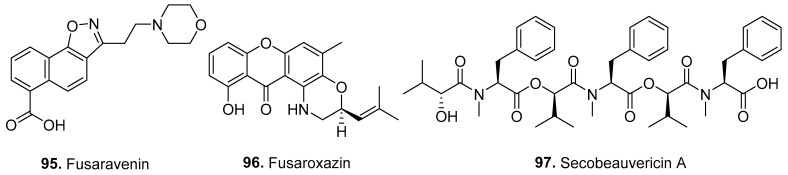

2.8. Other Nitrogen-Containing Metabolites

The structures of other new nitrogen-containing metabolites isolated from Fusarium fungi are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Structures of the other nitrogen-containing metabolites (95–97) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Fusaravenin (95) is a naphthoisoxazole formic acid connected to a morpholino carbon skeleton isolated from the soil-derived fungus F. avenaceum SF-1502 [64].

Fusarioxazin (96) is a 1,4-oxazine-xanthone derivative isolated from F. oxysporum, which is associated with the roots of Vicia faba (Leguminosae). Fusarioxazin (96) possessed significant antibacterial activity toward Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus, with MIC values of 5.3 mg/mL and 3.7 mg/mL, respectively. Furthermore, fusarioxazin (96) displayed a promising cytotoxic effect on HCT-116, MCF-7, and A549 cells, with IC50 values of 2.1 mM, 1.8 mM, and 3.2 mM, respectively [65].

Secobeauvericin A (97) is a linear hexadepsipeptide isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp., which was derived from the stem of a tea plant [49].

3. Polyketides and Their Biological Activities

The polyketides from Fusarium fungi mainly include pyrones, furanones, and quinones. The metabolites and their biological activities, along with Fusarium species and their origins, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

New polyketides (98–207) isolated from Fusarium fungi and their biological activities.

| Metabolite Class |

Metabolite Name | Biological Activity |

Fusarium Species |

Fungal Origin |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrones: α-pyrones | |||||

| (7S,8R)-Chlamydospordiol (98) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [53] | |

| 6-((2S,3S)-2,3-Dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (99); 6-((2R,3R)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (100); 6-((2S,3R)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (101); 6-((2R,3S)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (102) | Cytotoxic activity | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [66] | |

| Dihydrolateropyrone (103) | - | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [67] | |

| Fupyrones A (104) and B (105) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [68] | |

| Fusaisocoumarin A (106) | Antifungal activity | F. verticillioides | Plant endophytic fungus | [69] | |

| Fusaripyrones C (107) and D (108) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [70] | |

| Fusaritricins A (109/110) and B–D (111–113) | Antibacterial activity | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [71] | |

| Fusintespyrone A (114) | Antifungal activity | Fusarium sp. | Intestinal fungus | [72] | |

| Fusopoltides B (115) and C (116) | - | F. solani | Plant endophytic fungus | [73] | |

| 7-Hydroxy-3-(2-hydroxy-propyl)-5-methyl-epi-isochromen-1-one (117) | - | F. graminearum | Marine-derived fungus | [39] | |

| Isocoumarin analogs 118, 119, and 120 | - | F. decemcellulare | Plant endophytic fungus | [44] | |

| Karimunone A (121) | Antibacterial activity | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [74] | |

| Proliferapyrone A (122) | - | F. proliferatum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [75] | |

| Pyrones: γ-pyrones | |||||

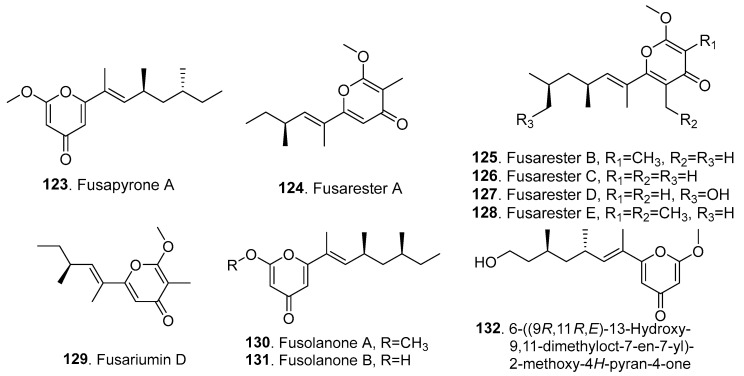

| Fusapyrone A (123) | Cytotoxic activity | Fusarium sp. | Desert-derived fungus | [76] | |

| Fusaresters A–E (124–128) | Inhibitory activity against protein tyrosine phosphatase | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [77] | |

| Fusariumin D (129) | Antibacterial activity | F. oxysporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [77,78] | |

| Fusolanonones A (130) and B (131) | Antibacterial activity | F. solani | Mangrove-derived fungus | [55] | |

| 6-((9R,11R,E)-13-Hydroxy-9,11-dimethyloct-7-en-7-yl)-2-methoxy-4H-pyran-4-one (132) | Neuroprotective activity | F. solani | Plant endophytic fungus | [79] | |

| Furanones | |||||

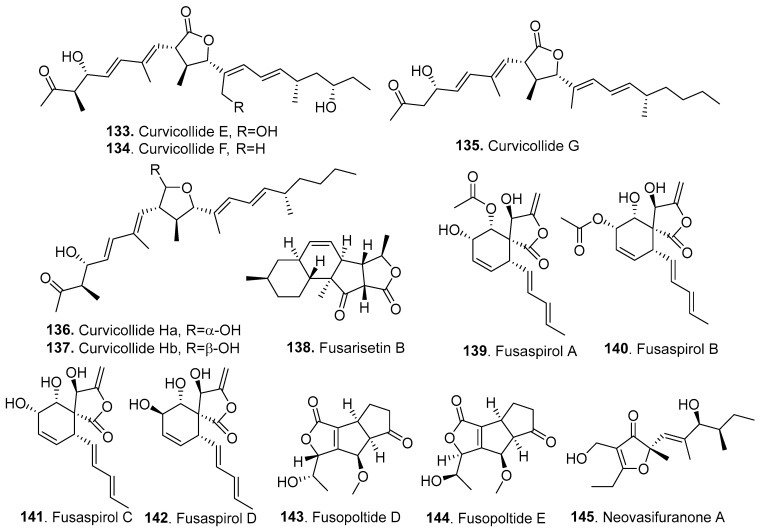

| Curvicollides E–G (133–135), Ha (136), and Hb (137) | Cytotoxic activity | F. armeniacum | Plant endophytic fungus | [80] | |

| Fusarisetin B (138) | Cytotoxic activity | F. equiseti | Entomogenous fungus | [35] | |

| Fusaspirols A–D (139–142) | Osteoclastic differentiation activity | F. solani | Plant endophytic fungus | [73] | |

| Fusopoltides D (143) and E (144) | - | F. solani | Plant endophytic fungus | [81] | |

| Neovasifuranones A (145) and B (146) | Antibacterial activity | F. oxysporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [82] | |

| Spiroleptosphols T1 (147), T2 (148), and U–Z (149–154) | - | F. avenaceum | Plant endophytic fungus | [83] | |

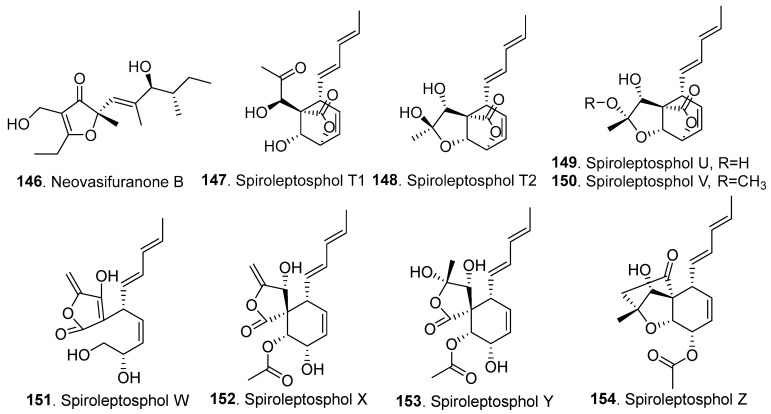

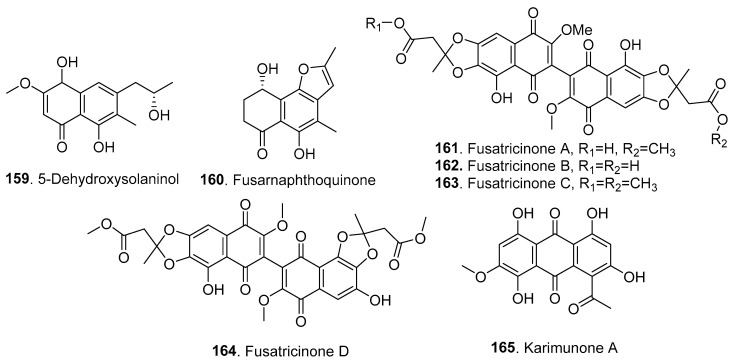

| Quinones | |||||

| 6-Hydroxiy-astropaquinone B (155); astropaquinone D (156) | Antibacterial and phytotoxic activities | F. napiforme | Mangrove-derived fungus | [84] | |

| 1-Methoxylfusarnaphthoquinone A (157); 1-dehydroxysolaninol (158); 5-dehydroxysolaninol (159); fusarnaphthoquinone D (160) | Cytotoxic activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [85] | |

| Fusatricinones A–D (161–164) | - | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [67] | |

| Karimunone A (165) | - | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [74] | |

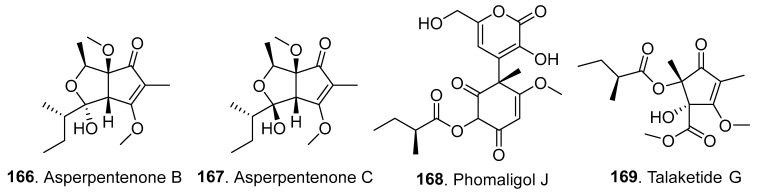

| Others | |||||

| Asperpentenones B (166) and C (167); phomaligol J (168); talaketides G (169) and H (170) | Cytotoxic activity | F. proliferatum | Mangrove-derived fungus | [86] | |

| Furarin Y (171) | Cytotoxic activity | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [34] | |

| Fusaranes A (172) and C (173) | Antibacterial activity | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [87,88] | |

| Fusaridioic acid E (174) | Anti-inflammatory activity | F. solani | Plant endophytic fungus | [89] | |

| Fusarielins M (175) and N (176) | Inhibitory activity against protein tyrosine phosphatase B | F. graminearum | Marine-derived fungus | [90] | |

| Fusarins G–K (177–181) | Anti-inflammatory activity | F. solani | Marine-derived fungus | [33] | |

| Fusarisolins A–E (182–186) | Inhibition of HMG-CoA synthase gene expression | F. solani | Marine-derived fungus | [91] | |

| Fusaritide A (187) | Reduced cholesterol uptake | F. verticillioide | Marine fish-derived fungus | [92] | |

| Fusariumnols A (188) and B (189) | Antibacterial activity | F. proliferatum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [93] | |

| Fusariumtrin A (190) | - | Fusarium sp. | Entomogenous fungus | [54] | |

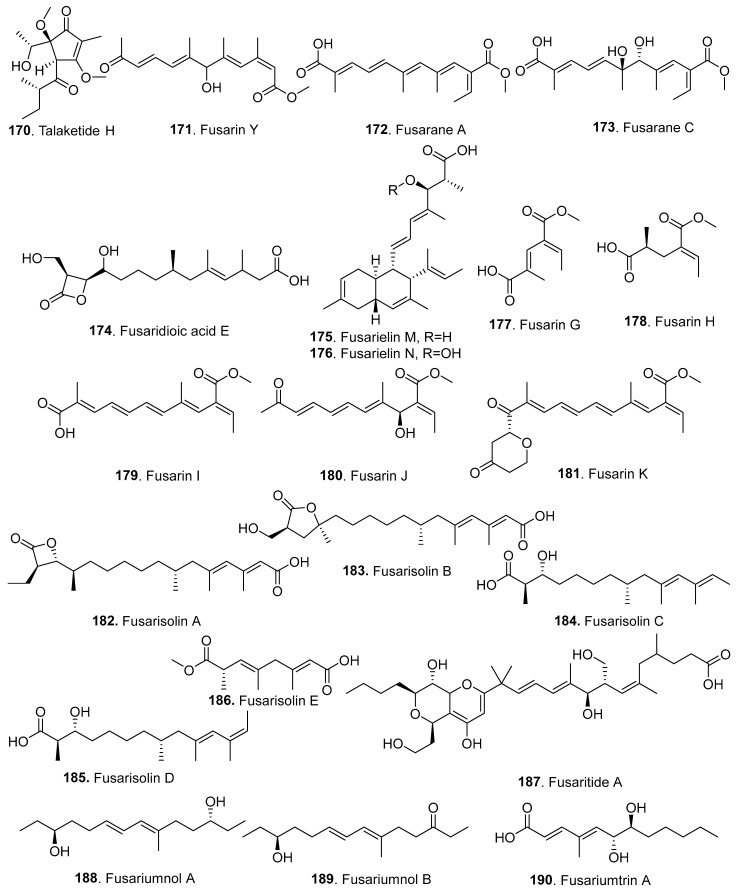

| Gramiketides A (191) and B (192) | - | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [94] | |

| Kaneoheoic acids A–F (193–198) | - | Fusarium sp. | Marine-derived fungus | [95] | |

| Kaneoheoic acids H (199) and I (200) | Antibacterial and cytotoxic activities | F. graminearum | Marine-derived fungus | [39] | |

| Pentaene diacid analog 201 | - | F. decemcellulare | Plant endophytic fungus | [44] | |

| Proliferic acids A–E (202–206) | Phytotoxic activity | F. proliferatum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [75] | |

| Protofusarin (207) | - | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [96] | |

3.1. Pyrones

Pyrones are also called pyranones. Two types of pyrones named α- and γ-pyrones were derived from Fusarium fungi.

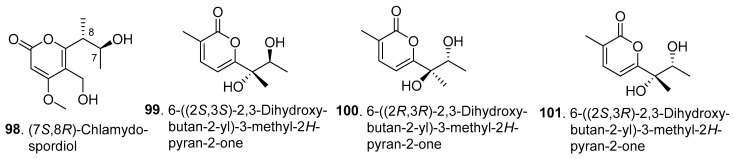

3.1.1. α-Pyrones

Twenty-five new α-pyrones (98–122) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, with their structures shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Structures of the α-pyrones (98–122) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

One new α-pyrone derivative, (7S,8R)-chlamydospordiol (98), was obtained from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. BZCB-CA, which was isolated from the Chinese medicinal plant Bothriospermum chinense (Boraginaceae) [53].

Four previously undescribed 2-pyrones sharing the same planar structure of 6-(2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one were isolated as two pairs of racemes by preparative HPLC and further as four epimers by subsequent chiral separation from the brown rice solid medium of F. tricinctum, an endophytic fungus of Ligusticum chuanxiong. They were identified as 6-((2S,3S)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (99), 6-((2R,3R)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (100), 6-((2S,3R)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (101), and 6-((2R,3S)-2,3-dihydroxybutan-2-yl)-3-methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (102). The four 2-pyrones showed the same growth inhibition against HTC116, A549, and MV 4-11 cell lines, with IC50 values of 0.013, 0.014, and 0.039 μM, respectively [66].

Dihydrolateropyrone (103) is a lateropyrone derivative isolated from F. tricinctum; the endophytic fungus was derived from healthy, fresh rhizomes of Aristolochia paucinervis (Aristolochiaceae) [67].

Fupyrones A (104) and B (105) were isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. F20, which was isolated from the stems of the medicinal plant Mahonia fortunei (Berberidaceae) [68].

Fusaisocoumarin A (106) was isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. verticillioides, which was derived from the leaves of Mentha piperita (Labiatae). Fusaisocoumarin A (106) showed antifungal activity against Aspergillus austroafricanus, A. versicolor, A. tubingensis, Phoma fungicola, and Candida albicans, with MIC values ranging from 0.3 to 1.3 mg/mL [69].

Two α-pyrones, namely, fusaripyrones C (107) and D (108), were isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. L33 derived from the leaves of Dioscorea opposite (Dioscoreaceae). Fusaripyrones C (107) and D (108) showed no obvious cytotoxic activity against five human tumor cell lines, including HL-60, A549, SMMC-7721, MDA-MB-231, and SW-480, at 40 μM, with an inhibition rate of less than 50% [70].

(+)-Fusaritricin A (109), (−)-fusaritricin A (110), and fusaritricins B (111), C (112), and D (113) were isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. tricinctum, which was derived from kiwi (Actinidia chinensis) plants (Actinidiaceae). Fusaritricins A (109/110), B (111), and C (112) exhibited antibacterial activity against the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), with MIC values of 128, 128, and 64 μg/mL, respectively [71].

Fusintespyrone A (114) was isolated from the intestinal fungus Fusarium sp. LE06 of the murine cecum. Fusintespyrone A (114) showed significant growth inhibition against Aspergillus fumigatus, F. oxysporum, and Verticillium dahlia, with MIC values in the range of 1.56–6.25 μg/mL [72].

Two α-pyrone analogs, fusopoltides B (115) and C (116), were isolated from F. solani B-18, which was isolated from the inner tissue of unidentified forest litter collected in the Mount Merapi Area, Indonesia [73].

7-Hydroxy-3-(2-hydroxy-propyl)-5-methyl-epiisochromen-1-one (117) was isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. graminearum FM1010, which was isolated from shallow-water volcanic rock known as “live rock” at Richardson’s Beach, Hilo, Hawaii [39].

Three unnamed isocoumarin analogs, 118–120, were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. decemcellualre F25, which was derived from the stems of the medicinal plant Mahonia fortune (Berberidaceae) collected in Qindao, China [44].

One benzopyranone, namely, karimunone B (121), was isolated from the sponge-associated fungus Fusarium sp. KJMT.FP.4.3. Karimunone B (121) showed antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica ser. Typhi with an MIC value of 125 μg/mL [74].

Proliferapyrone A (122) is an α-pyrone-polyketide glycoside isolated from the fermentation cultures of the plant pathogenic fungus F. proliferatum. Proliferapyrone A (122) did not exhibit phytotoxic activity and was considered the precursor of phytotoxins [75].

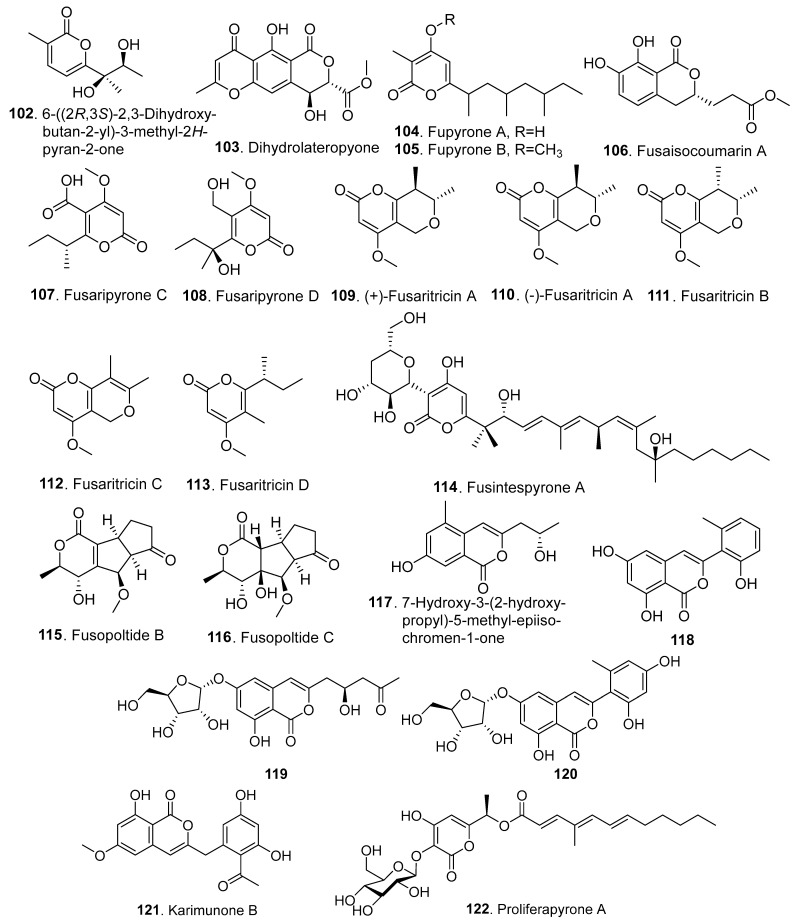

3.1.2. γ-Pyrones

Ten new γ-pyrones (123–133) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Structures of the γ-pyrones (123–132) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

One γ-pyrone derivative, namely, fusapyrone A (123), was isolated from the rice fermentation cultures of Fusarium sp. CPCC 401218, a fungus collected from the desert. Fusapyone A (123) showed weak antiproliferative activity against HeLa cells with an IC50 value of 50.6 μM [76].

Five γ-pyrone-containing polyketides, namely, fusaresters A (124), B (125), C (126), D (127), and E (128), were isolated from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. Hungcl, which was isolated from soil collected from the Futian Mangrove Reserve in Shenzhen, China. Among them, fusarester B (125) showed a weak inhibition rate of 56% against protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) at 40 μM [77].

Fusariumin D (129) is a γ-pyrone-containing derivative isolated from F. oxysporum ZZP-R1, which was derived from the coastal plant Rumex madio Makino (Polygonaceae). Fusariumin D (129) was previously identified as a sesquiterpene ester [78], and later, the structure was revised as a γ-pyrone derivative [77]. This metabolite had moderate antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, with an MIC value of 25.0 μM [78].

Two γ-pyrone derivatives, fusolanones A (130) and B (131), were isolated from the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus F. solani HDN15-410, which was isolated from the roots of Rhizophora apiculata Blume (Rhizophoraceae). Fusolanone A (130) showed antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with MIC value of 26.4 μg/mL. Fusolanone B (131) showed strong antibacterial activity against Monilia albican, Pesudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus, with MIC values of 12.5 μg/mL, 12.5 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 6.25 μg/mL, respectively [55].

One γ–pyrone, namely, 6-((9R,11R,E)-13-Hydroxy-9,11-dimethyloct-7-en-7-yl)-2-methoxy-4H-pyran-4-one (132), was isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. solani JS-0169, which was obtained from the leaves of Morus alba (Moraceae). This γ–pyrone showed moderate neuroprotective activity [79].

3.2. Furanones

Twenty-two new furanones (133–154) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Structures of the furanones (133–154) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Curvicollides E (133), F (134), G (135), Ha (136), and Hb (137) were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. armeniacum, which was derived from Digitaia ciliaris (Gramineae). Among the compounds, curvicollide E (133) showed the strongest cytotoxic activity against HeLa cells, with an IC50 value of 1.86 μg/mL [80].

Fusarisetin B (138) was isolated from the entomogenous fungus F. equiseti LGWB-9 from Harmonia axyridis and showed cytotoxicity against MCF-7, MGC-803, HeLa, and Huh-7 cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 2.4 to 69.7 μg/mL [35].

Five polyketides with a γ-methylidene-spirobutanolide core, fusaspirols A (139), B (140), C (141), and D (142), were isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. solani B-18, which was isolated from the inner tissue of unidentified forest litter collected in the area of Mount Merapi in Indonesia. Fusaspirol A (139) activated a signaling pathway in the osteoclastic differentiation of murine macrophage-derived RAW264.7 cells [81].

Two furanone analogs, fusopoltides D (143) and E (144), were isolated from F. solani B-18, which was isolated from the inner tissue of unidentified forest litter collected in the area of Mount Merapi in Indonesia [81].

Two diastereomeric polyketides, neovasifuranones A (145) and B (146), were obtained from solid rice cultures of the endophytic fungus F. oxysporum R1 associated with the Chinese medicinal plant Rumex madaio (Polygonaceae). Their absolute configurations were determined by combining modified Mosher’s reactions and chiroptical methods using time-dependent density functional theory electronic circular dichroism (TDDFT-ECD) and optical rotatory dispersion (ORD). Both compounds exhibited weak inhibitory antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori [82].

Eight furanones were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. avenaceum 05,001, which was isolated from Finnish grains. They were identified as spiroleptosphols T1 (147), T2 (148), U (149), V (150), W (151), X (152), Y (153), and Z (154) [83].

3.3. Quinones

Eleven new quinones (155–165) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Structures of the quinones (155–165) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Two naphthoquinone derivatives, 6-hydroxy-astropaquinone B (155) and astropaquinone D (156), were isolated from F. napiforme, an endophytic fungus isolated from the mangrove plant Rhizophora mucronata (Rhizophoraceae). Both 6-hydroxy-astropaquinone B (155) and astropaquinone D (156) exhibited moderate antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and phytotoxic activity against lettuce seedlings at a concentration of 30 μg/mL [84].

Four quinones, namely, 1-methoxylfusarnaphthoquinone A (157), 1-dehydroxysolaninol (158), 5-dehydroxysolaninol (159), and fusarnaphthoquinone D (160), were isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. HJT-P-5 derived from Rhodiola angusta Nakai (Crassulaceae), which was obtained from Changbai Mountain in Jilin, China. Among them, 1-dehydroxysolaninol (158) showed the strongest cytotoxic activity against human colorectal cancer HCT116 cells, with an inhibitory rate of 64.39% at 100 μM [85].

F. tricinctum, an endophytic fungus that lives inside healthy, fresh rhizomes of Aristolochia paucinervis (Aristolochiaceae), created four new compounds called naphthoquinone dimers, namely, fusatricinones A–D (161–164). The antibacterial activity of these compounds was evaluated against the human pathogenic bacterial strains Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but no activities were observed [67].

One new naphthoquinone, karimunone A (165), was isolated from the sponge-associated fungus Fusarium sp. KJMT.FP.4.3 [74].

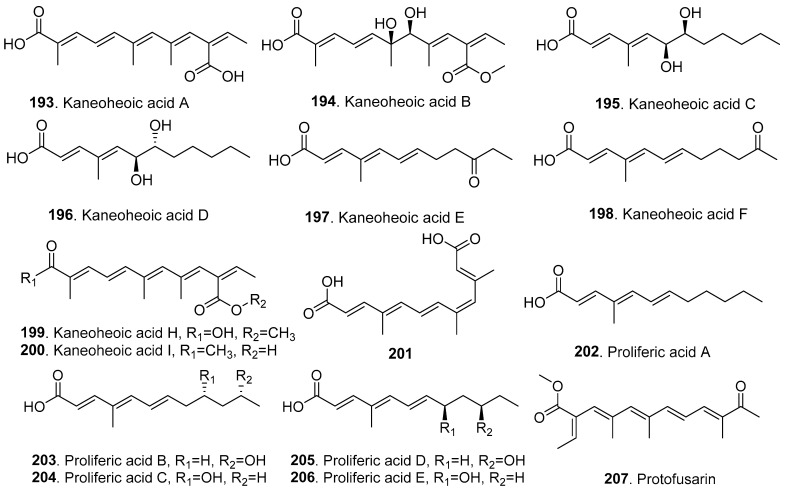

3.4. Other Polyketides

Thirty-five other new polyketides (166–207) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, with their structures shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Structures of the other polyketides (166–190 and 193–207) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Five new polyketides, including asperpentenones B (166) and C (167), phomaligol J (168), and talaketides G (169) and H (170), were isolated from the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus F. proliferatum NSD-1 from Kandelia candel (Rhizophoraceae). Phomaligol J (168) and talaketides G (169) and H (170) showed cytotoxic activities, with IC50 values of 24.9 μM for A549 cells, 37.5 μM for SW480 cells, and 43.2 μM for A549 cells, respectively [86].

Fusarin Y (171) was a polyketide isolated from the Fusarium head blight pathogen F. graminearum. Fusarin Y (171) showed weak cytotoxic activity against three tumor cell lines [34].

Fusaranes A (172) and C (173) were isolated from cultures of F. graminearum [87,88]. Fusarane A (172) showed potent antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, with an MIC value of 32 μg/mL [87].

Fusaridioic acid E (174) is an alkenoic acid analog isolated from the endophytic fungus F. solani MBM-5 of Datura arborea (Solanaceae). Fusaridioic acid E (174) exhibited significantly anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting NO release from LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells, with an IC50 value of 77. 00 μM [89].

The secreted Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase B (MptpB) is an essential virulence factor required for the intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis within host macrophages. MptpB has become a promising target for developing novel anti-tuberculosis (TB) drugs. Two new fusarielins with a decalin core, namely, fusarielins M (175) and N (176), were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. graminearum SYSU-MS5127, which was isolated from an anemone collected from Laishizhou Island in Shenzhen, China. Fusarielin M (175) was proved to be highly efficient in blocking MptpB-mediated Erk1/2 and p38 inactivation in macrophages and inhibiting mycobacterial growth within macrophages. In addition, fusarielin M (175) showed increased specificity for MptpB compared to MptpA and human PTP1B [90].

Fusarins G (177), H (178), I (179), J (180), and K (181) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. solani 7227, which was isolated from a seawater sample collected in the South China Sea. Among them, fusarins H (178), I (179), J (180), and K (181) showed anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NO production in a murine macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7 cells) [33].

Five polyketides, fusarisolins A–E (182–186), were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. solani H918, which was isolated from mangrove sediments. Fusarisolins A (182) and B (183) were the first two naturally occurring 21-carbon polyketides featuring a rare β- and γ-lactone unit, respectively. Fusarisolin A (182) significantly inhibited 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) synthase gene expression [91].

Fusaritide A (187) was isolated from the marine fish-derived halotolerant fungus F. verticillioide G102. It reduced cholesterol uptake by inhibiting Niemann–Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) [92].

Two novel aliphatic unsaturated alcohols, namely, fusariumnols A (188) and B (189), were isolated from the plant pathogenic fungus F. proliferatum, associated with diverse crops, including rice, wheat, maize, and garlic. Both compounds exhibited weak antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis, with an MIC value of 100 μM [93].

Fusariumtrin A (190) was isolated from the entomogenous fungus Fusarium sp. LGWB-7 from Harmonia axyridis [54].

Gramiketides A (191) and B (192) were produced during the infection of wheat by F. graminearum. The molecular formulae of gramiketides A (191) and B (192) were C29H44O8 and C29H42O7, respectively, as estimated by LC-HRMS analysis. Unfortunately, their final structures were not determined [94].

Kaneoheoic acids A–F (193–198) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium sp. FM701, which was isolated from a muddy sample from a Hawaiian beach [95].

Kaneoheoic acids H (199) and I (200) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus F. graminearum FM1010, which was isolated from shallow-water volcanic rock known as “live rock” at Richardson’s Beach, Hilo, Hawaii. Kaneoheoic acids H (199) and I (200) showed strong antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus. In addition, kaneoheoic acid I (200) exhibited both anti-proliferative activity against ovarian cancer cell line A2780 and TNF-α-induced NF-κB inhibitory activity, with IC50 values of 18.52 and 15.86 μM, respectively [39].

One unnamed pentaene diacid analog, 201, was isolated from the endophytic fungus F. decemcellualre F25, which was derived from the stems of the medicinal plant Mahonia fortunei (Berberidaceae) collected in Qindao, China [44].

Proliferic acids A (202), B (203), C (204), D (205), and E (206) were isolated from the fermentation cultures of the plant pathogenic fungus F. proliferatum. Among them, proliferic acid A (202) showed significant inhibitory activity against the growth of Arabidopisis thaliana roots. Proliferic acid A (202) was generated from proliferapyrone A (122) via the β-glucosidase-mediated hydrolysis of ester bonds and was inactivated by the intracellular oxidase-catalyzed oxidation of the terminal inert carbon atoms to form proliferic acids B (203), C (204), D (205), and E (206) [75].

Deleting a repressive histone methylation modification usually results in the derepression of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in fungi. By using a mutant (ΔKmt6) of F. graminearum lacking the H3K27 methyltransferase Kmt6, protofusarin (207) derived from the fusarin biosynthetic pathway was identified [96].

4. Terpenoids and Their Biological Activities

The terpenoids from Fusarium fungi mainly include sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoids, and triterpenoids. The terpenoids, their biological activities, Fusarium species, and their origins are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

New terpenoids (208–265) isolated from Fusarium fungi and their biological activities.

| Metabolite Class |

Metabolite Name | Biological Activity |

Fusarium Species |

Fungal Origin |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesquiterpenoids | |||||

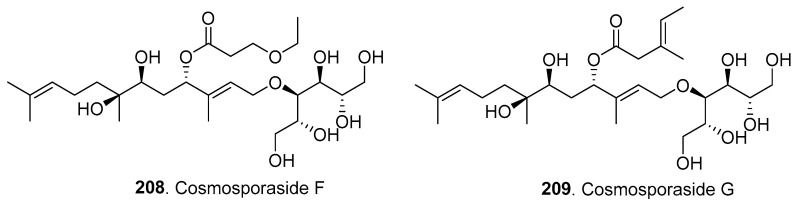

| Cosmosporasides F–H (208–210) | Antibacterial, cytotoxic, and anti-inflammatory activities | F. oxysporum | Soil-derived fungus | [97] | |

| Cyclonerotriol B (211) | - | F. avenaceum | Soil-derived fungus | [64] | |

| (R,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-Ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (212); (S,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (213) | Cytotoxic activity | F. tricinctum | Plant endophytic fungus | [98] | |

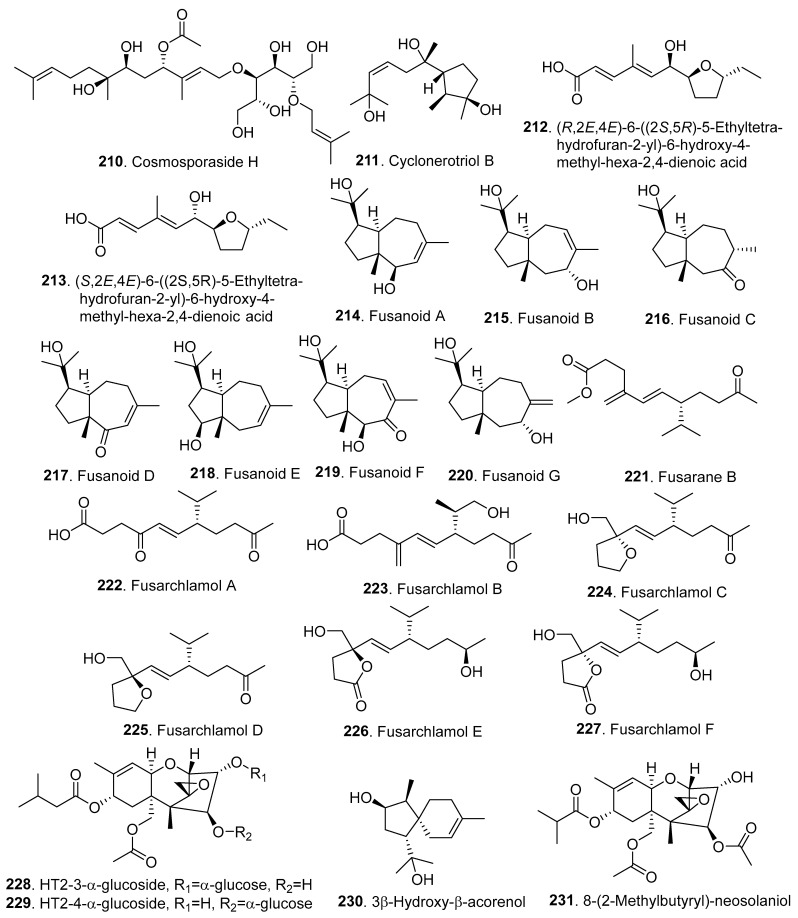

| Fusanoids A–G (214–220) | Cytotoxic activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [99] | |

| Fusarane B (221) | Cytotoxic activity | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [88] | |

| Fusarchlamols A–F (222–227) | Antifungal activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [100] | |

| HT2-3-O-α-glucoside (228); HT2-4-O-α-glucoside (229) | - | F. sporotrichioides | Plant pathogenic fungus | [101] | |

| 3β-Hydroxy-β-acorenol (230) | - | F. proliferatum | Plant endophytic fungus | [64] | |

| 8-(2-Methylbutyryl)-neosolaniol (231) | - | F. sporotrichioides | Plant endophytic fungus | [102] | |

| Microsphaeropsisins D (232) and E (233) | Antifungal activity | F. lateritium | Insect-derived fungus | [103] | |

| Proliferacorins A–M (234–246) | - | F. proliferatum | Soil-derived fungus | [104] | |

| Tricinolone (247); tricinolonoic acid (248) | - | F. graminearum | Plant pathogenic fungus | [96] | |

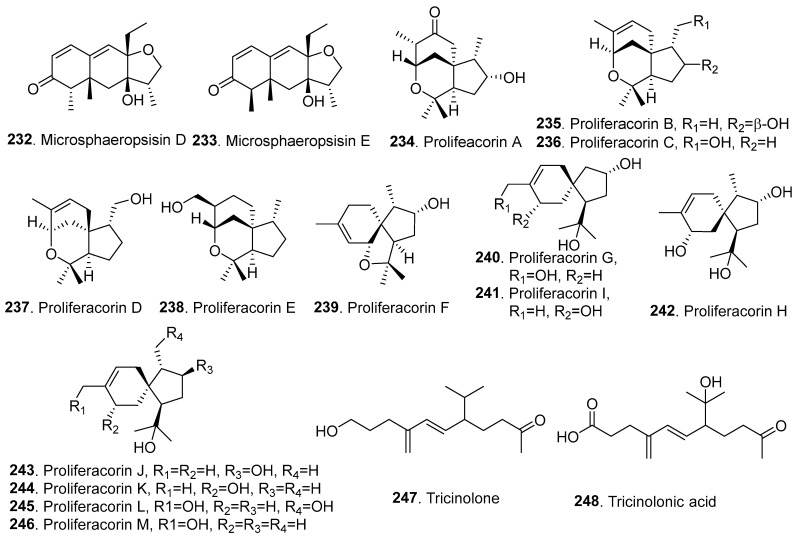

| Diterpenoids | |||||

| 3β,16α-Dihydroxy-9,15-cyclo-gibberellin A9 (249); 7α-methoxy-6,7-lactone-gibberellin A12 (250); 7β-methoxy-6,7-lactone-gibberellin A12 (251); 16α-hydroxy-9-ene-gibberellin A14 (252) | Promoting effect on seedling growth | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [105] | |

| Fusarium acids A–H (253–260) | Inhibition of hypocotyl and root elongation in tomato seedlings | F. oxysporum f.sp. radicis-lycopersici | Plant pathogenic fungus | [106] | |

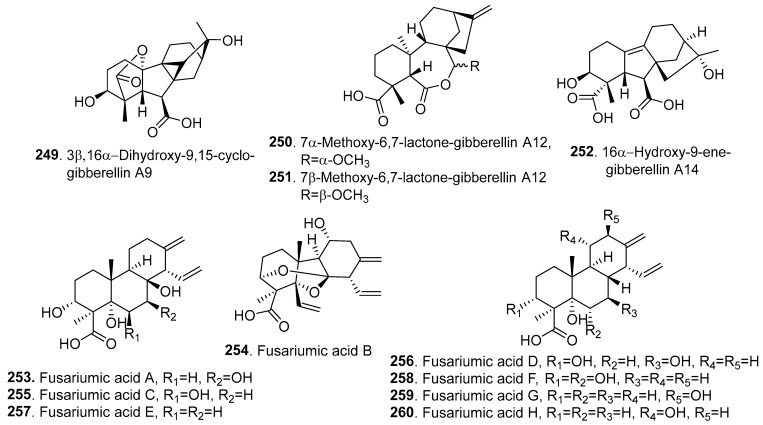

| Triterpenoids | |||||

| Integracide K (261) | Cytotoxic activity | F. armeniacum | Plant endophytic fungus | [107] | |

| Integracide L (262) | Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [108] | |

| Others | |||||

| (E)-9,10-Dihydroxy-2,6,10-trimethylundec-5-enoic acid (263); (E)-8,9-dihydroxy-1-methoxy-5,9-dimethyldec-4-en-2-one (264) | - | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [28] | |

| Fusariumin C (265) | Antibacterial activity | F. oxysporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [78] | |

4.1. Sesquiterpenoids

Forty-one new sesquiterpenoids (208–248) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Structures of the sesquiterpenoids (208–248) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Three sugar-alcohol-conjugated acyclic sesquiterpenoids, namely, cosmosporasides F (208), G (209), and H (210), were isolated from the soil-derived fungus F. oxysporum SC0002, which was isolated from a soil sample collected in the Dinghu Mountain Biosphere Reserve located in Guangdong, China. Cosmosporasides F–H (208–210) showed weak antibacterial, cytotoxic, and anti-inflammatory activities at concentrations of 100 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, and 50 μg/mL, respectively [97].

Cyclonerotriol B (211) is a cyclonerane sesquiterpenoid isolated from the soil-derived fungus F. avenaceum SF-1502 [64].

Two nor-sesquiterpenoids, namely, (R,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (212) and (S,2E,4E)-6-((2S,5R)-5-ethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-6-hydroxy-4-methylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (213), were isolated from the endophytic fungus F. tricinctum, which was isolated from the roots of Ligusticum chuanxiong (Umbelliferae) collected in Sichuan, China. Of the two sesquiterpenoids, compound 212 exhibited moderate cytotoxic activity against MV4-11, with an IC50 value of 22.29 μM [98].

Seven carotane sesquiterpenoids named fusanoids A–G (214–220) were isolated from the fermentation broth of the desert plant endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. HM166, which was isolated from Chenopodium quinoa (Chenopodiaceae) collected from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of West China. Among the compounds, fusanoid B (215) showed cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 cells of the human breast cancer cell line, while fusanoid D (217) showed potent inhibitory activity against IDH1R132h mutant [99].

One sesquiterpenoid, namely, fusarane B (221), was isolated from cultures of the plant pathogenic fungus F. graminearum. Fusarane B (221) showed 61% and 75% inhibitory rates against HeLa cells and Mia PaCa2 cells, respectively, at 20 μM [88].

Six new sesquiterpenoids, fusarchlamols A–F (222–227), were isolated from an endophytic fungus, which was derived from sweet corn Zea mays (Gramnineae). Fusarchlamols A (222), B (223), E (226), and F (227) showed significant antifungal activity against the phytopathogen Alternaria alternata isolated from Coffea arabica (Rubiaceae), with an MIC value of 1 μg/mL [100].

Two HT2-glucosides, namely, HT2-3-O-α-glucoside (228) and HT2-4-O-α-glucoside (229), were isolated from rice cultures of F. sporotrichioides, the fungal pathogen of maize. The authors proposed that glucosyltransferase did not form both HT2-glucosides as they were in plants but by a trans-glycosylating α-glucosidase expressed by the fungus on the starch-containing rice medium [101].

3β-Hydroxy-β-acorenol (230) with an acorane framework was isolated from the endophytic fungus F. proliferatum AF-04, which was separated from the green Chinese onion (Allium fistulosum) [64].

8-(2-Methylbutyryl)-neosolaniol (231) was isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. sporotrichioides, which was derived from the fruits of the medicinal plant Rauvolfia yunnanensis (Apocynaceae) collected in Yunnan, China [102].

Two new sesquiterpenoids, microsphaeropsisins D (232) and E (233), were isolated from the insect-derived fungus F. lateritium ZMT01. Microsphaeropsisin D (232) showed antifungal activities against F. oxysporum, Penicillium italicum, and Colletotrichum musae, with MIC values of 50, 25, and 25 mg/L, respectively. Microsphaeropsisin E (233) showed antifungal activities against F. oxysporum, P. italicum, C. musae, and F. graminearum with MICs of 25, 12.5, 12.5, and 100 mg/L, respectively. The in vivo bioassay showed that microsphaeropsisin E (233) displayed a control effect on banana anthracnose [103].

Thirteen new acorane sesquiterpenoids, namely, proliferacorins A–M (234–246), were isolated from the solid fermentation of the soil-derived F. proliferatum. Proliferacorins A–M (234–246) were tested for their cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive activities. Nevertheless, none showed distinct inhibitory activity [104].

New molecules could be discovered by a combination of chemical and genetic dereplication. By using a double mutant (ΔKmt6Δfus1) of F. graminearum, two new sesquiterpenoids, tricinolone (247) and tricinolonoic acid (248), belonging to the tricindiol class were isolated [96].

4.2. Diterpenoids

Twelve new diterpenoids (249–260) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Structures of the diterpenoids (249–260) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Gibberellins (GAs) are well-known tetracyclic diterpenoid phytohormones. Four new GAs, namely, 3β,16α-dihydroxy-9,15-cyclo-gibberellin A9 (249), 7α-methoxy-6,7-lactone-gibberellin A12 (250), 7β-methoxy-6,7-lactone-gibberellin A12 (251), and 16α-hydroxy-9-ene-gibberellin A14 (252), were isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. NJ-F5 from the roots of Mahonia fortune (Berberidaceae) collected in Nanjing, China. Among the isolated GAs, 3β,16α-dihydroxy-9,15-cyclo-gibberellin A9 (249) showed an obvious promoting effect on the seedling growth of Arabidopsis thaliana [105].

Eight isocassadiene-type diterpenoids, namely, fusariumic acids A–H (253–260), were isolated from the tomato Fusarium crown and root rot (FCRR) pathogen F. oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici (Forl). Among them, fusariumic acid B (254) contained a cage-like structure with an unusual 7,8-seco-isocassadiene skeleton. They all showed inhibitory activity against tomato seedlings at 200 μg/mL. Among them, fusariumic acid F (258) exhibited the strongest inhibition against hypocotyl and root elongation in tomato seedlings, with inhibitory rates of 61.3% and 45.3%, respectively [106].

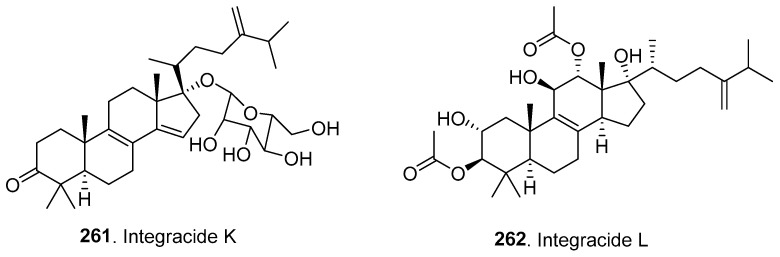

4.3. Triterpenoids

Two new triterpenoids (261, 262) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Structures of the triterpenoids (261 and 262) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Integracide K (261) was isolated from rice cultures of F. armeniacum M-3, an endophytic fungus from Digitaria ciliaris (Gramineae). Integracide K (261) exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against HeLa cells [107].

Integracide L (262) is a new tetracyclic triterpenoid isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp., which was separated from Mentha longifolia (Labiatae). Integracide L (262) showed strong 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity [108].

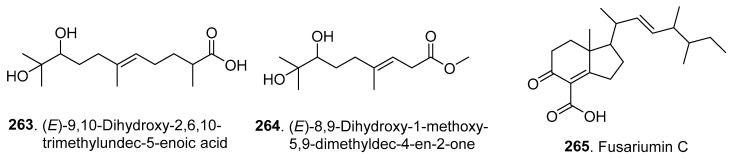

4.4. Other Terpenoids

Three other new terpenoids (263–265) were isolated from Fusarium fungi, and their structures are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Structures of the other terpenoids (263–265) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Two chain terpenoids, namely, (E)-9,10-dihydroxy-2,6,10-trimethylundec-5-enoic acid (263) and (E)-8,9-dihydroxy-1-methoxy-5,9-dimethyldec-4-en-2-one (264), were isolated from the plant endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. HJT-P-2, which was isolated from Rhodiola angusta (Crassulaceae) from Changbai Mountain, Jilin Province, China [28].

Fusariumin C (265) is a meroterpene containing a cyclohexanone moiety isolated from F. oxysporum ZZP-R1, which was derived from the coastal plant Rumex madio Makino (Polygonaceae). Fusariumin C (265) displayed potent activity against Staphyloccocus aureus, with an MIC value of 6.25 μM [78].

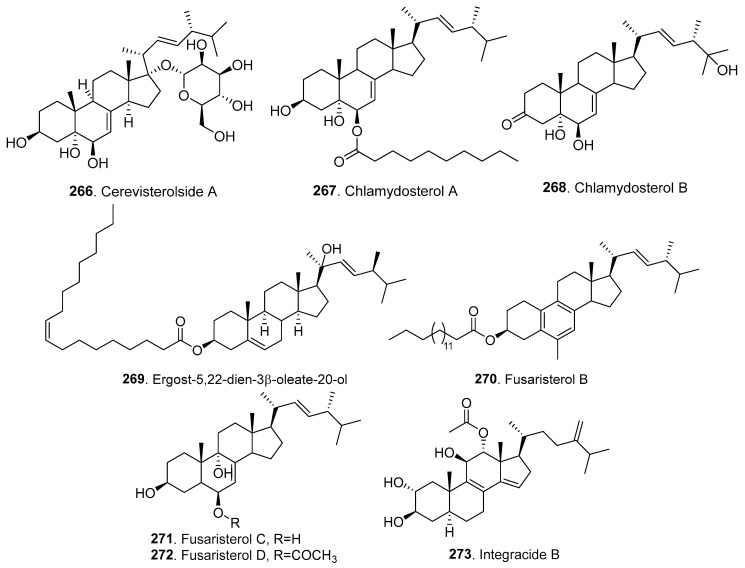

5. Steroids and Their Biological Activities

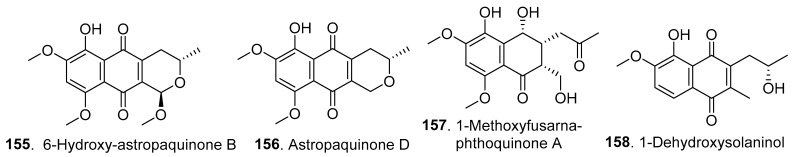

The new steroids, their biological activities, Fusarium species, and their origins are shown in Table 4. The structures of 18 new steroids are shown in Figure 18.

Table 4.

New steroids (266–273) isolated from Fusarium fungi and their biological activities.

| Metabolite Name | Biological Activity |

Fusarium Species |

Fungal Origin |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerevisterolside A (266) | Antifungal activity | Fusarium sp. | Mouse intestinal fungus | [72] |

| Chlamydosterols A (267) and B (268) | Anti-inflammatory activity | F. chlamydosporum | Plant endophytic fungus | [109] |

| Ergost-5,22E-dien-3β-oleate-20-ol (269) | - | F. phaeoli | Plant endophytic fungus | [110] |

| Fusaristerols B–D (270–272) | Anti-inflammatory activity | Fusarium sp. | Plant endophytic fungus | [111] |

| Integracide B (273) | - | F. armeniacum | Plant endophytic fungus | [107] |

Figure 18.

Structures of the steroids (266–273) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Cerevisterolside A (266) was isolated from the mouse intestinal fungus Fusarium sp. LE06 of the murine cecum. Cerevisterolside A (266) showed significant growth inhibition against Aspergillus fumigatus, F. oxysporum, and Verticillium dahlia, with MIC values in the range of 1.56–6.25 μg/mL [72].

Two new ergosterol derivatives, namely, chlamydosterols A (267) and B (268), were obtained from the endophytic fungus F. chlamydosporum, which was isolated from the leaves of Anvillea garcinii (Asteraceae) growing in Saudi Arabia. Chlamydosterol A (267) displayed anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting 5-lipooxygenase (5-LOX) activity with an IC50 value of 3.06 μM [109].

One new ergostane-type sterol, namely, ergost-5,22E-dien-3β-oleate-20-ol (269), was isolated from the endophytic fungus F. phaeoli, which was isolated from the roots of Chisocheton macrophyllus (Meliaceae) [110].

Three ergosterol derivatives, namely, fusaristerols B (270), C (271), and D (272), were isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. isolated from Mentha longifolia (Labiatae) roots growing in Saudi Arabia. Fusaristerols B (270) and C (271) showed anti-inflammatory activity by exhibiting 5-LOX inhibitory capacity, with IC50 values of 3.61 and 2.45 μM, respectively. The structure–activity relationship indicated that the absence of the chain fatty acyl moiety and peroxy group dramatically decreased anti-inflammatory activity [111].

Integracide B (273) was isolated from the rice cultures of F. armeniacum M-3, an endophytic fungus from Digitaria ciliaris (Gramineae) [107].

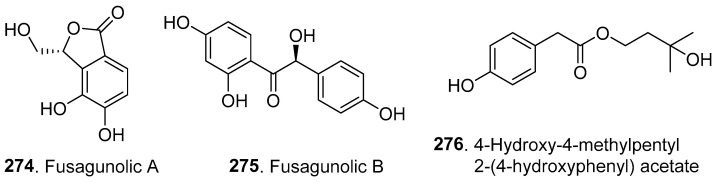

6. Phenolics and Their Biological Activities

The phenolics, their biological activities, Fusarium species, and their origins are shown in Table 5. The structures of three new phenolics are shown in Figure 19.

Table 5.

New phenolic metabolites (274–276) isolated from Fusarium fungi and their biological activities.

Figure 19.

Structures of the phenolic metabolites (274–276) isolated from Fusarium fungi.

Two new phenolic compounds, fusagunolics A (274) and B (275), were isolated from the plant endophytic fungus F. guttiforme. Fusagunolic B (275) showed moderate anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting nitric oxide (NO) production with an IC50 value of 28.6 μM [112].

4-Hydroxy-4-methylpentyl 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) acetate (276) is a phenolic compound isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. HJT-P-2 of Rhodiola serrata (Crassulaceae). The compound showed weak inhibitory effects on the root growth of Arabidopsis thaliana [113].

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

In this mini-review, we summarized the chemical structures, biological activities, occurrence, and fungal origin of 276 newly isolated secondary metabolites from at least 21 Fusarium species reported from 2019 to October 2024 (Table S1). The main secondary metabolites belong to nitrogen-containing metabolites, polyketides, terpenoids, steroids, and phenolics. Some metabolites exhibited obvious biological activities.

Some Fusarium secondary metabolites, such as imidazole alkaloids, including fusaritricines A–I (78–86), (+)-fusaritricine J (87), (−)-fusaritricine J (88), and fusaritricines K–P (89–94), were isolated from F. tricinctum [62,63]. These imidazole alkaloids were also only isolated from the genus Fusarium. These metabolites may display chemotaxonomic significance, which should be further studied.

Some Fusarium metabolites, such as apicidin L (40), as an antimalarial [47]; beauvericin H (41), as an anti-tumor agent [48]; and chlamydosterol A (267), as an anti-inflammatory agent [109], have shown their potential medicinal and agricultural applications [114,115]. Some Fusarium-derived phytotoxins could be used as fungal herbicide candidates [21,27]. The endophytic F. oxysprum strains could be used as biocontrol agents against other pathogenic fungi such as Verticillium dahlia, Pythium ultimum, and Botrytis cinerea with their complex biocontrol mechanisms [115].

Many biosynthetic pathways that link secondary metabolites with their corresponding BGCs have been identified in Fusarium fungi. Therefore, most of these metabolites linked to their BGCs must be investigated [20]. In order to search for new bioactive metabolites from Fusarium fungi, some strategies, such as the one strain many compounds (OSMAC) approach [116], environmental factor regulation [117], transcriptional regulation [19], epigenetic regulation [118], gene deletion and overexpression [52,96], co-cultivation [119], and heterologous expression [120], have been proven to be effective to activate the silent gene clusters and produce more secondary metabolites in Fusasrium fungi.

In the past, Fusarium secondary metabolites were mainly obtained from plant pathogenic Fusarium species. The secondary metabolites usually belonged to mycotoxins or phytotoxins such as beauvericin, enniatins, fumonisins, fusaproliferin, fusaric acid, moniliformin, trichothecenes, and zearalenone [2,17,121]. However, in recent years, more and more secondary metabolites were isolated from plant endophytic [5], soil-derived [64,97], and marine-derived Fusarium species [122]. In addition to phytotoxic and animal toxic activities, the biological activities of Fusarum metabolites are also manifested in many other aspects such as anti-virus, antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective activities, as well as the inhibitory activities toward enzymes (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5).

Though major Fusarium species have been studied for their metabolites [5], the remaining fungal species in the Fusarium genus need to be revealed in detail. Moreover, the biological activities, structure–activity relationships, mechanisms of action, biosynthesis, and biosynthesis regulation of the metabolites of Fusarium fungi need to be further investigated. The clarification of the metabolites of Fusarium fungi may not only promote the discovery of more compounds with novel structures and excellent biological activities but also provide a better understanding the physiological, ecological, and chemotaxonomic significance of Fusarium fungi.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof10110778/s1, Table S1: List of Fusarium species used for the isolation of new secondary metabolites reported from 2019 to October 2024. All the references cited in Supplementary Table S1 are listed in the References section of the text.

Author Contributions

L.Z. conceptualized and supervised this study. P.A. and L.Z. prepared and wrote this manuscript. X.P. and X.H. collected the references. X.P., X.H. and J.S. drew structures. M.A.J. and E.O. revised the figures and tables. D.X. and D.L. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1700700 and 2022YFD1700200) and the Postgraduate Self-dependent Innovation Foundation of China Agricultural University.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Summerell B.A. Resolving Fusarium: Current status of the genus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019;57:323–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLean M. The phytotoxicity of Fusarium metabolites: An update since 1989. Mycopathologia. 1996;133:163–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02373024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinedine A., Soriano J.M., Molto J.C., Manes J. Review on the toxicity, occurrence, metabolism, detoxification, regulations and intake of zearalenone: An oestrogenic mycotoxin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007;45:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierzgalski A., Bryla M., Kanabus J., Modrzewska M., Podolska G. Updated review of the toxicity of selected Fusarium toxins and their modified forms. Toxins. 2021;13:768. doi: 10.3390/toxins13110768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed A.M., Mahmoud B.K., Millan-Aguinaga N., Abdelmohsen U.R., Fouad M.A. The endophytic Fusarium strains: A treasure trove of natural products. RSC Adv. 2023;13:1339–1369. doi: 10.1039/D2RA04126J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu M., Huang Z., Zhu W., Liu Y., Bai X., Zhang H. Fusarium-derived secondary metabolites with antimicrobial effects. Molecules. 2023;28:3424. doi: 10.3390/molecules28083424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutleb A.C., Morrison E., Murk A.J. Cytotoxicity assays for mycotoxins produced by Fusarium strains: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2002;11:309–320. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(02)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berthiller F., Lemmens M., Werner U., Krska R., Hauser M.-T., Adam G., Schuhamacher R. Short review: Metabolism of the Fusarium mycotoxins deoxynivalenol and zearalenone in plants. Mycotoxin Res. 2007;23:68–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02946028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y., Wang Z., Beier R.C., Shen J., De Smet D., De Saeger S., Zhang S. T-2 toxin, a trichothecene mycotoxin: Review of toxicity, metabolism, and analytical methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:3441–3453. doi: 10.1021/jf200767q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong Z., Zhu W., Su H., Zhao Y., Zhang K.-Q., Yang J. Recent advances in genes involved in secondary metabolite synthesis, hyphal development, energy metabolism and pathogenicity in Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph Gibberella zeae) Biotechnol. Adv. 2014;32:390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei J., Wu B. Chemistry and bioactivities of secondary metabolites from the genus Fusarium. Fitoterapia. 2020;146:104638. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qu Z., Ren X., Du Z., Hou J., Li Y., Yao Y., An Y. Fusarium mycotoxins: The major food contaminants. mLife. 2024;3:176–206. doi: 10.1002/mlf2.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perochon A., Doohan F.M. Trichothecenes and fumonisins: Key players in Fusarium–cereal ecosystem interactions. Toxins. 2024;16:90. doi: 10.3390/toxins16020090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M., Yu R., Bai X., Wang H., Zhang H. Fusarium: A treasure trove of bioactive secondary metabolites. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020;37:1568–1588. doi: 10.1039/D0NP00038H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toghueo R.M.K. Bioprospecting endophytic fungi from Fusarium genus as sources of bioactive metabolites. Mycology. 2020;11:1–21. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2019.1645053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urbaniak M., Waskiewicz A., Stepien L. Fusarium cyclodepsipeptide mycotoxins: Chemistry, biosynthesis, and occurrence. Toxins. 2020;12:765. doi: 10.3390/toxins12120765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu D., Xue M., Shen Z., Jia X., Hou X., Lai D., Zhou L. Phytotoxic secondary metabolites from fungi. Toxins. 2021;13:261. doi: 10.3390/toxins13040261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li P., Su R., Yin R., Lai D., Wang M., Liu Y., Zhou L. Detoxification of mycotoxins through biotransformation. Toxins. 2020;12:121. doi: 10.3390/toxins12020121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou X., Liu L., Xu D., Lai D., Zhou L. Involvement of LaeA and velvet proteins in regulating the production of mycotoxins and other fungal secondary metabolites. J. Fungi. 2024;10:561. doi: 10.3390/jof10080561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z., Zhu W., Bai Y., Bai X., Zhang H. Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-encoding products and their biosynthetic logics in Fusarium. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024;23:93. doi: 10.1186/s12934-024-02378-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bendejacq-Seychelles A., Gibot-Leclerc S., Guillemin J.-P., Mouille G., Steinberg C. Phytotoxic fungal secondary metabolites as herbicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024;80:92–102. doi: 10.1002/ps.7813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez A.H., Pacheco A.D., Tolibia S.E.M., Xicohtencatl Y.M., Balbuena S.Y.G., Lopez V.E.L. Bioprocess of gibberellic acid by Fusarium fujikuroi: The challenge of regulation, raw materials, and product yields. J. Fungi. 2024;10:418. doi: 10.3390/jof10060418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perincherry L., Lalak-Kanczugowska J., Stepien L. Fusrium-produced mycotoxins in plant-pathogen interactions. Toxins. 2019;11:664. doi: 10.3390/toxins11110664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Z., Chen Y., Wang X., Deng Y., Wang X., Li S., Ding X., Duan J. Accumulation of fatty acylated Fusarium toxin 2-amino-14, 16-dimethyloctadecan-3-ol, a class of novel 1-deoxysphingolipid analogues, during food storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022;70:5151–5158. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c08065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe Y., Arakawa E., Kondo N., Nonaka K., Ikeda A., Hirose T., Sunazuka T., Hokari R., Ishiyama A., Iwatsuki M. New antimalarial fusarochromanone analogs produced by the fungal strain Fusarium sp. FKI-9521. J. Antibiot. 2023;76:384–391. doi: 10.1038/s41429-023-00617-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham G.N., Josselin B., Cousseau A., Baratte B., Dayras M., Meur C.L., Debaets S., Burgaud G., Probert I., Abdoul-Latif F.M., et al. New fusarochromanone derivatives from the marine fungus Fusarium equiseti UBOCC-A-117302. Mar. Drugs. 2024;22:444. doi: 10.3390/md22100444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao D.-L., Liu J., Han X.-B., Wang M., Peng Y.-L., Ma S.-Q., Cao F., Li Y.-Q., Zhang C.-S. Decalintetracids A and B, two pairs of unusual 3-decalinoyltetramic acid derivatives with phytotoxicity from Fusarium equiseti D39. Phytochemistry. 2022;197:113125. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2022.113125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu X., Sun Y., Li Y., Zhang X., Zhao Y., Feng B. Terpenoid derivatives from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. HJT-P-2 of Rhodiola angusta Nakai. Phytochem. Lett. 2021;45:48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2021.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu R., Li M., Wang Y., Bai X., Chen J., Li X., Wang H., Zhang H. Chemical investigation of a co-culture of Aspergillus fumigatus D and Fusarium oxysporum R1. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2020;15:130–135. doi: 10.25135/rnp.199.20.07.1728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdelhakim I.A., Mahmud F.B., Motoyama T., Futamura Y., Takahashi S., Osada H. Dihydrolucilactaene, a potent antimalarial compound from Fusarium sp. RK97-94. J. Nat. Prod. 2022;85:63–69. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Y.-W., Liu X.-J., Yuan J., Li H.-J., Mahmud T., Hong M.-J., Yu J.-C., Lan W.-J. L-Tryptophan induces a marine-derived Fusarium sp. to produce indole alkaloids with activity against the Zika virus. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:3372–3380. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakai K., Unten Y., Iwatsuki M., Matsuo H., Fukasawa W., Hirose T., Chinen T., Nonaka K., Nakashima T., Sunazuka T. Fusaramin, an antimitochondrial compound produced by Fusarium sp., discovered using multidrug-sensitive Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Antibiot. 2019;72:645–652. doi: 10.1038/s41429-019-0197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo G., Zheng L., Wu Q., Chen S., Li J., Liu L. Fusarins G–L with inhibition of NO in RAW264.7 from marine-derived fungus Fusarium solani 7227. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:305. doi: 10.3390/md19060305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]