Abstract

Embedded within the field of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK), biotransformation is a discipline that studies the origins, disposition, and structural identity of metabolites to provide a comprehensive safety assessment, including the assessment of exposure coverage in toxicological species. Spanning discovery and development, metabolite identification (metID) scientists employ various strategies and tools to address stage-specific questions aimed at guiding the maturation of early chemical matter into drug candidates. During this process, the identity of major (and minor) circulating human metabolites is ascertained to comply with the regulatory requirements such as the Metabolites in Safety Testing (MIST) guidance. Through the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (IQ), the “Translatability of MetID In Vitro Systems Working Group” was created within the Translational and ADME Sciences Leadership Group. The remit of this group was to objectively determine how accurate commonly employed in vitro systems have been with respect to prediction of circulating human metabolites, both qualitatively and quantitatively. A survey composed of 34 questions was conducted across 26 pharmaceutical companies to obtain a foundational understanding of current metID practices, preclinically and clinically, as well as to provide perspective on how successful these practices have been at predicting circulating human metabolites. The results of this survey are presented as an initial snapshot of current industry-based metID practices, including our perspective on how a harmonized framework for the conduct of in vitro metID studies could be established. Future perspectives from current practices to emerging advances with greater translational capability are also provided.

Keywords: ADME, biotransformation, IVIVC, MetID

Introduction

Metabolite identification (metID) is a key component of small molecule drug discovery and development. Early in discovery, metID data can assist with compound optimization, including identifying metabolic soft spots [1], understanding enzymatic-mediated clearance routes [2–4], enhancing metabolic stability [5], identification of active metabolites [6], and minimizing metabolic bioactivation [7]. In development, individual metabolites present in circulation equal to or above 10% of total drug-related material (DRM) at steady-state [8–10] must be evaluated for safety by comparing their plasma exposure in humans to exposures in animal toxicity studies [11]. If circulating metabolite levels in preclinical toxicology studies are at or above 50% of the human exposure, then the metabolite is considered covered and no additional work is required. However, if a metabolite is not covered in preclinical toxicity studies (not detected or with an exposure below the stated 50% threshold), then the metabolite is considered unique or disproportionate in human, and additional safety testing is recommended [12–14]. To minimize the risk of this latter scenario, extensive efforts are taken to understand the metabolic fate of lead molecules in vitro and in vivo to anticipate and determine major human metabolic routes.

Numerous in vitro models are available to assess drug metabolism [15]. Liver microsomes supplemented with NADPH offer a facile way to evaluate primarily cytochrome P450 (CYP)-mediated metabolism over short incubation times (≤ 1 h) [15]. Similarly, liver S9 fractions (with appropriate co-factors) and suspension hepatocytes allow evaluation of both oxidative and conjugative metabolism [16, 17]. The metID data obtained from these in vitro systems offer an early assessment of the metabolic stability of a parent compound and can provide useful information regarding metabolically labile sites and routes of metabolism. In some cases, however, the metabolic clearance of the parent compound may be low by design, and the aforementioned in vitro models are not able to generate meaningful information [18]. Additionally, for low turnover compounds, the viability of the in vitro system may preclude the appearance of metabolites. In these examples, the use of plated hepatocytes co-cultured with stromal cells offer a way to extend the incubation time over multiple days [19, 20]. Multiple variations of this approach are commercially available, including HuREL and HepatoPac [21], three-dimensional primary hepatocyte spheroids [22, 23], ‘liver-on-a-chip’ microphysiological systems (MPS) [24, 25], and ex vivo perfused liver models [26, 27].

The utility of an in vitro metID model can be measured in terms of its translatability of results to the in vivo setting [16, 20]. Ideally, for a given species, there is a predictive relationship between the metabolites produced in vitro to those found in vivo, enabling data-driven selection of preclinical species for toxicity studies. In addition, accurate prediction of in vivo metabolites formed enables de-risking of clinical development, e.g., by early assessment of pharmacological/toxicological activity [28], DDI assessment [29], or stable-labelled isotope standard synthesis for absolute quantification in latter clinical studies [30]. However, the presence of metabolites in vivo is a function of both metabolite formation and disposition, the latter of which cannot be addressed in most in vitro models [31]. Yet, in vitro models are often described in the literature in terms of their translatability [31, 32]. Dalvie et al. evaluated the three most common in vitro systems – liver microsomes, liver S9 fraction, and suspension hepatocytes, and assessed their ability to produce metabolites of 48 drugs that had been identified as major in human studies [16]. If the in vitro system produced the major metabolite, it was considered a successful translation. However, metabolite levels in vitro were considered out of scope and metabolites that were formed in vitro but not identified as major metabolites in vivo were not addressed.

Currently, the term ‘translatability’ when applied to metID in vitro systems remains open to interpretation and is debatable. For the purposes of efficient development and MIST guidance compliance, two key aspects of an employed in vitro system are desired: (1) an in vitro model that produces sufficient and relevant metabolic turnover for useful metID, and (2) the ability to determine which metabolites produced in vitro will be major in circulation in the respective species in vivo. While papers have been written to suggest which metabolites may circulate [33, 34], no in vitro system has been shown to accurately fulfill both above requirements.

Through the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (IQ), a working group was formed within the Translational and ADME Sciences Leadership Group (TALG) to evaluate the current state of in vitro metID as it pertains to clinical translatability across the pharmaceutical industry. The mission of this working group, named the “Translatability of MetID In Vitro Systems Working Group,” is to define current practices across industry and to maximize the accuracy of predicting circulating metabolites from in vitro data, both qualitatively and quantitatively. This manuscript addresses the first aim of this working group by summarizing the results of an industry-wide survey to collate modern metID practices and the in vivo predictivity of the in vitro assays utilized. This report is not intended to be a review of the rationale for why certain metID systems and approaches are conducted and does not address strategic concerns regarding optimization of such tools used for drug discovery and development programs. Instead, this report presumes that all working group members have appropriate knowledge of metID in the pharmaceutical sciences and presents current industry practices regarding a wide variety of topics of interest to those working in this field. For reviews on metID in the pharmaceutical sciences, readers are directed to the literature [15, 29, 35, 36].

Materials & Methods

The working group generated a survey consisting of 34 questions to probe the current practices and perceptions of metID in vitro systems and their role in drug discovery and development. Surveys were sent out to 26 companies, all of which completed the survey. The IQ anonymized the results before sharing them with the working group for analysis and interpretation. The working group’s synthesis and perspective on the results is provided here.

Results

Selection of In Vitro Test Systems

What biotransformation assays does your company use, and how often and when do you use them?

| System | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Suspension hepatocytes | 100% | 56% responders chose suspension hepatocytes as their preferred primary system while 6% chose microsomes and 8% S9 fractions. These widely used systems are commercially available, often well-characterized in terms of metabolic activity, and easy to use, all likely factors explaining their frequent adoption |

| Microsomes | 96% | |

| S9 fractions | 88% | |

| Plasma | 77% | A more tailored approach is selected either to address inherent limitations in near universal models (e.g., hepatocyte co-culture models needed to augment metabolite formation for metabolically stable compounds) or to target more select metabolic processes (e.g., plasma or recombinant drug metabolizing enzymes) |

| Recombinant enzyme | 73% | |

| Hepatocyte co-culture | 69% | |

| Non-hepatic system | 58% | It may include plasma or other extrahepatic tissues and 7 respondents (27%) specifically confirmed they utilized gut microbiota to study drug metabolism in vitro |

| Plateable hepatocytes | 31% | |

| Spheroid model | 23% | |

| Hepatocyte relay method | 15% | |

| Microphysiological system | 15% | |

| Liver slices | 0% | Liver slice models are no longer employed across respondents perhaps due to its labor-intensive methodology, limited availability, and limited to only a single donor |

When does your company assess gut microbiome mediated metabolism in vitro?

| Status | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmation of the use | 62% | Generally, microbiota-based metabolism is studied more reactively to an unexpected metabolite observation rather than prospectively for programs. The identification of an unexpected in vivo metabolite either in circulation or in excreta was cited as the major reason for its use (63% of these respondents). Others considered the use based upon the presence of certain structural motifs which may be prone to microbial metabolism or for the study of gut restricted drugs |

| Have not assessed gut microbiome mediated metabolism or not applicable | 38% |

Selection of In Vitro Test Conditions

Does your company adapt the in vitro biotransformation system work-up based on expected metabolite formation, e.g., acidify samples to avoid acyl glucuronide hydrolysis or migration?

| Status | Frequency | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 70% | The most common adaptation was the acidification of samples post-reaction to minimize the hydrolysis and migration of acyl glucuronide metabolites. Other functional groups considered for procedural adjustments included esters and amides prone to hydrolysis and alkenes prone to E/Z conversation from light. Respondents highlighted the importance of structural insight, availability of supplementary data, and method development, often aided by the availability of synthetic standards, to establish appropriate conditions before conducting in vitro studies |

| No | 30% |

Does your company change/modify the in vitro biotransformation system based on metabolic reactions, i.e., hydrolysis, glucuronidation, etc.? What compound concentration and incubation time does your company typically use in in vitro biotransformation assays? Please specify concentration and incubation time per assay if it differs by assay.

| Status | Frequency | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 89% | Most respondents will evaluate the structure of test compound when considering incubations in subcellular fractions and in the selection of appropriate co-factors to enable metabolic activity. Non-metabolic systems (e.g., buffer incubations) were also highlighted by certain respondents to be of use if ester or amide hydrolysis is anticipated to be a significant pathway |

| No | 11% |

Table I.

Summary of Most Common Concentration and Time Conditions Employed for In vitro Biotransformation Test

| Incubation Condition | Suspension Hepatocytes [26, 100%] |

Microsomes [25, 96%] |

S9 Fractions [23, 89%] |

Plasma [18, 69%] |

Recombinant Enzymes [17, 65%] |

Hepatocyte Co-culture [17, 65%] |

Non-Hepatic Systems [14, 54%] |

Plateable Hepatocytes [8, 31%] |

Spheroid Model [6, 23%] |

Hepatocyte Relay [4, 15%] |

MPS [3, 12%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration |

10 µM (0.5 – 30 µM) |

10 µM (0.5 – 20 µM) |

10 µM (0.5 – 20 µM) |

10 µM (0.5 – 20 µM) |

10 µM (0.5 – 20 µM) |

10 µM (1 – 10 µM) |

10 µM (1 – 30 µM) |

10 µM (0.5 – 30 µM) |

5—10 µM (5 – 30 µM) |

10 µM (1 – 30 µM) |

10 µM (0.02 – 50 µM) |

| Time |

2 – 4 h (2 – 6 h) |

30 – 60 min (10 – 120 min) |

60 min (15 – 240 min) |

24 h (0.5 – 24 h) |

60 min (15 – 120 min) |

7 day (1 – 7 day) |

System dependent (0.5 h – 5 day) |

1 – 2 day (2 h – 7 day) |

No consensus (2 h – 7 day) |

20 h (2 – 24 h) |

No consensus (1 – 14 day) |

Brackets: The number and percentage of this survey’s 26 respondents that provided conditions for each biotransformation test system

Parenthesis: Range in values from aggregate of responses

Table II.

Distribution of Respondents using Varying Concentrations (Low vs. High) During In Vitro Incubations

| Assay type (total responses for concentration selection) | Suspension Hepatocytes (26) | Microsomes (25) | S9 Fractions (23) | Plasma (18) | Recombinant Enzymes (17) | Hepatocyte Co-culture (17) | Non-hepatic Systems (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High conc. only or High + Low (≤ 2 µM) | 92% | 76% | 78% | 83% | 59% | 88% | 86% |

| High + Low conc. (≤ 2 µM), or low conc. only | 38% | 52% | 48% | 33% | 65% | 35% | 29% |

| Low conc. only (≤ 2 µM) | 8% | 24% | 22% | 17% | 41% | 12% | 14% |

Does your company use proteins in your in vitro models to consider the unbound fraction (fu) in the metabolism prediction?

| Status | Frequency | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, always | 15% | The inclusion of proteins (e.g., plasma, albumin, BSA) to in vitro incubations has been considered by some to improve the rate of metabolism and their overall predictability [37–39]; however, these benefits have been challenged by others either unconvinced that protein enhances in vitro prediction [40] or who believe alternative factors explain the apparent benefit of addition of protein [41]. This topic is not unique to drug metabolizing enzymes but extends also to hepatic uptake transporters and their in vitro conduct [42–44] |

| Depending on compound properties | 23% | It was most often cited to be used for compounds that are highly protein bound as this was considered beneficial to the metabolic system, while, for one respondent, it was for covalent inhibitors or compounds prone to form reactive metabolites |

| Never | 62% |

If your company does use proteins in vitro , which source do you use?

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was the most common source utilized by half of these respondents followed by plasma (unspecified species) and human serum albumin (HSA), each employed by one respondent. The preference for BSA may be attributable to a few reasons: albumin is the major protein source in plasma and often responsible for drug binding, BSA bears high structural similarity to HSA [45], and BSA is more cost effective than HSA and other protein sources.

Does your company utilize inhibitors in metID assays for enzyme phenotyping?

| Status | Frequency | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 85% | The pan-CYP inhibitor 1-aminobenzotriazole (ABT) was the most commonly employed inhibitor for the purpose of distinguishing P450 vs. non-P450 oxidizing enzymes such as aldehyde oxidase (AO), occasionally paired by some with the CYP2C9 inhibitor tienilic acid to improve ABT’s effectiveness as a pan-CYP inhibitor. Other specified inhibitors mentioned by at least one respondent included the AO inhibitor hydralazine, the phosphatase inhibitor menadione [46], and the CYP3A inhibitors azamulin and cobicistat |

| No | 15% |

Use of In Silico Tools

Which best describes your company’s position on utilizing computational modeling/machine learning to predict drug metabolites?

| Status | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Presently employing | 42% | Metabolite prediction, metabolic soft spot ID, structural alerts for drug induced liver injury assessment (one instance) |

| Considering | 19% | Metabolite prediction |

| Not planning on employing | 39% | Improvement in software prediction accuracy and reliability desired |

Does your company incorporate calculated physicochemical or ADME properties of metabolites identified in vitro to facilitate prediction of circulating metabolites, such as cLogP, volume of distribution, or clearance?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 15% | One company used for design phase & in vivo predictions; one for clearance prediction, permeability & solubility; one for building QSAR models |

| No | 85% | Two companies were interested in its use or planned to incorporate |

Interpretation, Quantification, and Reporting of metID Results

How does your company use in vitro metabolite data?

| Response | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Qualitative only; metabolite present or not present, no reference to abundance relative to drug related material | 22% |

| Quasi-quantitative; metabolite present or not present, with some appreciation of abundance relative to drug related material | 54% |

| Quantitative; metabolites assigned as major/significant or minor/insignificant | 24% |

If, from your in vitro data, your company suggests metabolites are major/significant or assigns them as such, what criteria do you use?

In general, if a metabolite shows an abundance of ≥ 10% of total DRM in either MS, UV and/or radiolabel (if applicable) response in an in vitro assay, it is considered as a major/significant metabolite. One response stated that a threshold of 5% is used, whereas others do not have a particular threshold or simply rank by UV response or decide case-by-case. Another response stated that the term “major” will not be used solely based on in vitro data, as this term can be defined by clinical data (i.e., hADME) only. Instead, the term “predominant”, “main” or “significant” in vitro metabolite is used. The effort to detect and characterize far more than metabolites close to the 10% total DRM threshold is also stated to give a comprehensive picture of the metabolism of the parent compound.

Considering both in vitro and in vivo, how does your company assess metabolite profiles quantitatively, and at what stage do you employ these techniques?

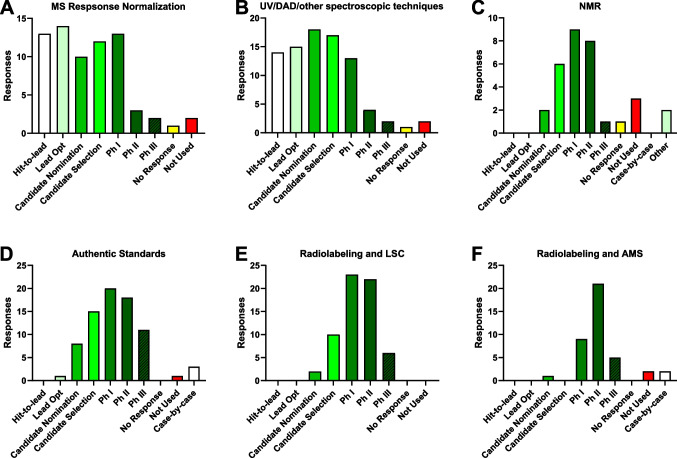

See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Approaches to assessing metabolites quantitatively. Respondents were asked to select those analytical approaches they employ and at what stage of drug discovery/development they employ them. The data are represented as number of responses per stage and are graphed according to quantification approach: (A) MS response normalization; (B) UV/DAD or other spectroscopic techniques; (C) NMR; (D) Authentic standards; (E) Radiolabeling and LSC/radiodetection for analysis; (F) Radiolabeling and AMS for analysis. Y-axis may be unique for a given graph.

Per project stage, what cutoff does your company employ for reporting metabolites?

| Stage | All Metabolites | Cutoff (% of DRM) | Top 3–5 Metabolites | Other Approach | Total # of Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2% | 5% | 10–20% | |||||

| HL | 22% | 6% | 11% | 17% | 33% | 11% | 18 |

| LO | 17% | 13% | 9% | 17% | 30% | 13% | 23 |

| CS | 28% | 39% | 0% | 0% | 17% | 17% | 18 |

| Phase 1 | 43% | 33% | 5% | 14% | 0% | 5% | 21 |

| Phase 1I | 44% | 39% | 6% | 11% | 0% | 0% | 18 |

Data are presented as % of total responses per stage

Tox Species Selection

In your company, how often are in vitro metabolite data used for selecting preclinical tox species?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 0% – 25% of the time | 23% |

• Not key determinant, but rather supports an existing case/preference • Use alongside in vivo profiles • Only in cases of dog/monkey disconnects • Rat/mouse default depending on disease; dog most common non-rodent; metID may not change the species selection • Infrequently • Additionally, tox species is selected based on pharmacological relevance |

| > 25%—50% of the time | 4% | |

| > 50%—75% of the time | 23% | |

| > 75%—100% of the time | 50% |

Rank order the following preclinical species in terms of frequency of selection for tox studies by your company.

| Item | Overall Rank | Score* | # of Rankings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | 1 | 173 | 25 |

| Dog | 2 | 141 | 25 |

| Monkey | 3 | 112 | 25 |

| Mouse | 4 | 106 | 23 |

| Rabbit | 5 | 53 | 19 |

| Minipig | 6 | 46 | 15 |

| Other | 7 | 1 | 1 |

*Score was determined by assigning a numerical value to each rank in descending order, 7 to 1, followed by summation for each species

Action Taken in Response to Unique or Disproportionate Human Metabolites, or Predicted Major Metabolites

For metabolites observed in vivo but not in vitro , how does your company characterize enzyme phenotyping?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Try to find the tissue in vivo where the metabolite(s) form, then use proteomics to find out the protein responsible for its production | 24% | |

| No need to characterize enzyme phenotyping | 16% | |

| Other | 60% | See additional text below |

If an in vitro to in vivo correlation was not observed, then a decision to investigate the enzymes responsible for the formation of the observed in vivo metabolite(s) was made on a case-by-case basis. Additional rationale for proceeding with enzyme phenotyping on a case-by-case basis are as follows: level of the metabolite (if > 10% of drug-related material (DRM) in vivo), if it was not identified in preclinical toxicological species, it possesses pharmacological activity, if the clearance rate and pathway differs from majority of DRM or if further information may be needed for regulatory interactions. If any of these criteria were met and further investigation was warranted then primarily responders use secondary in vitro approaches, for example, to test AO, XO, FMO and a broader panel of CYPs. A minority of responders investigates ex-vivo tissues. It was also highlighted that a discordance of in vitro to in vivo metabolism is rare.

What does your company do if a metabolite is predicted to be major in human circulation but has shown high exposure and good cross-species coverage in tox species in vivo?

| Status | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Frontloading metabolite synthesis & characterization | 58% | Characterization: Establish bioanalytical assays (35%), initiate in vitro safety studies (39%), assess pharmacological activity (15%) |

| Waiting for metabolite confirmation in phase 1 | 38% |

After confirmation: Pharmacological assay before bioanalysis After confirmation: Exposure in GLP tox studies using mixed matrix approach and human MAD samples before synthesis |

| Decide case-by-case | 4% | Considerations: tentative structure assignment, feasibility of synthesis |

In Vivo Predictivity of In Vitro metID Assays

Considering the in vitro biotransformation assays your company employs, how would you describe their accuracy in predicting circulating metabolites in vivo in their respective species?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 75—100% of the time | 38% |

• Difficult to capture secondary or extra-hepatic metabolites in vitro • In vivo prediction linked to metabolite structure |

| 25—< 75% of the time | 38% | |

| 0—< 25% of the time | 8% | |

| Not Applicable | 15% |

Free responses were tallied and binned according to the above categories.

When comparing metabolites in vivo to the respective species in vitro metabolite data, how often do you observe the following?

See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

In vivo predictivity of in vitro metID assays. Respondents were presented with six in vitro-to-in vivo scenarios (A) and asked to estimate the frequency with which they have observed each over recent memory. (B – G) = Scenarios 1 – 6, respectively, and represent the number of responses per frequency of observation. Respondents were asked to make their estimations based on in vitro-to-in vivo data within species. (H) The number of responses ≥ 50% for each scenario were summed and represented as a % of total responses per that same scenario; this represents the number of respondents who reported experiencing each scenario most of the time relative to the total number of respondents who reported for that scenario.

If our industry could accurately predict circulating metabolites in vivo , which type would you be interested in predicting?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| All circulating metabolites | 24% |

• Metabolites of interest include > 10% DRM, active metabolites w/ > 50% total pharmacological activity, potential toxic metabolites, potential reactive metabolites, major in liver/excreted into bile • One response interested in predicting metabolites of > 5% DRM |

| Circulating metabolites of interest | 35% | |

| Only major circulating metabolites | 41% |

What are primary reasons, perceived or confirmed by your company, that may lead to major circulating human metabolites being poorly anticipated despite pre-clinical biotransformation efforts?

See Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Reasons for poor prediction of major human circulating metabolites. Respondents were asked to describe primary reasons for why major circulating human metabolites may be poorly anticipated despite pre-clinical biotransformation efforts; these reasons could be perceived or confirmed. Data represent % of total respondents (N = 26) that selected a given description. Respondents were allowed to select all that apply. Reasons are abbreviated in figure for simplicity, but are listed verbatim here, in order from top to bottom: Insufficient metabolite production for highly stable drugs; Extensive metabolism into multiple primary (or sequential) metabolites; Non-hepatic drug metabolism; Compromised enzymatic activities in conventional in vitro metabolic systems (e.g., AO); Limited ability to predict metabolite’s disposition and elimination; This rarely happens; Poor IVIVC in pre-clinical species; Standard study protocols not tailored to anticipate pharmacological drug concentrations; Other (please describe).

Perspectives on Current Model for metID in Clinical Development

If the current paradigm for assessing human circulating metabolites is metID in FIH to inform developmental work followed by definitive human ADME in Ph2, what is your opinion of this paradigm?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| It is working well and should continue to be the paradigm | 54% | |

| It is working well, but there is room for improvement | 46% | See additional text below |

| It is not working well, change is needed | 0% |

Additional comments: Some respondents suggested that ADME studies in preclinical species could be helpful to determine potential clinically-relevant metabolites. One suggested using AMS or NMR early in phase 1 while another suggested that using HRMS to its fullest potential would ensure that no major metabolites were missed. A significant number of respondents commented that human ADME and microtracer studies should be conducted as early as possible (phase 1 or early phase 2), as it would enable to early quantify metabolites and trigger appropriate DDI, safety or pharmacological assessments if needed.

When considering potential future directions of biotransformation work within drug development, what is your company’s current position on a ‘human first’ approach to metID, where definitive human ADME is conducted in Ph 1 (e.g., 14C microtracer and AMS, quantitative NMR)?

| Response | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Have employed and currently employing wherever possible | 4% |

| Plan to employ in near future | 19% |

| Considering employing, but no imminent plans to do so | 42% |

| Not considering and/or awaiting more examples of success | 35% |

If your company has employed or is currently employing a ‘human first’ metID approach to provide definitive ADME in Ph 1, please describe the key requirements needed from a compound and/or program perspective to successfully implement such an approach.

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| My company has employed or is currently employing a ‘human first’ metID approach | 16% |

• Our current approach is that all ADME studies are ‘human first, human only’ in Ph 2 • Analytical sensitivity, i.e., AMS approaches – especially for chromatogram generation • Timelines of project flags from cold MetID (unique/disproportionate metabolites) • Investment from the project team to pull up the definitive human study. Availability of radiolabeled compound to perform study. Compound contains enough F to perform NMR |

| Not applicable | 84% |

When considering potential future directions of biotransformation work within drug development, and in terms of the current paradigm for human ADME studies, what is your company’s opinion on the selection of subjects?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The subjects selected are fine, the results obtained are fit for the desired purpose | 65% |

• Diseased population have been designated into Ph 1b studies on some occasions • Oncology will recruit from diseased populations |

| There is room for improvement in subject selection (i.e., disease relevant populations) and this should be explored | 35% | |

| There is room for improvement, but the costs to do so outweigh the potential benefits in the context of a clinical development plan | 0% |

When considering potential future directions of biotransformation work within drug development, human ADME studies are currently conducted after a single dose, where steady-state has not likely been achieved. Does this need to be addressed?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, because long-lived metabolites are not adequately represented using single dose | 12% |

• No, single dose ADME studies can inform on the need to follow up with an evaluation of steady-state plasma • We haven’t planned for this but it sounds like a pragmatic and worthwhile approach • Steady state for human ADME not the approach by default but to be considered in case of metabolite accumulation demonstrated with SAD/MAD samples • We hope to use 14C microtracer approach to achieve steady state in future. Waiting for more success stories • We have used 14C microtracer approach a few times, depending on PK linearity • We see great promise for the 14C microtracer approach and, as the AMS technology is improved/miniaturized, believe this will become standard practice • But this would also require a case-by-case determination |

| No, metID from MAD study tells us if there are any long-lived metabolites, which can be factored into the single dose ADME results | 52% | |

| Yes, if we use 14C microtracer approach, we can do a multi-dose study to achieve definitive ADME at steady state, and the benefits of doing so outweigh the costs | 36% |

When conducting human ADME studies with 14C material, dealkylation/hydrolysis risks losing information on part of the molecule. Does your company favor a dual-labeling strategy where the label is added to both sides of the molecule to account for cleavage?

| Response | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 56% | See additional text below |

| No | 44% |

Additional comments: Advocates of a dual-labeling approach argue that it provides the most comprehensive coverage of all generated metabolites, pertinent especially if cleaved metabolites are susceptible to extensive sequential metabolism; allows for a full appreciation of a drug’s pharmacology and toxicology; or satisfies the FDA draft guidance on the conduct of human ADME studies. For those opposed to the approach, some respondents feel they bear sufficient knowledge of the overall metabolic fate in vitro and in preclinical species in vivo to justify the rationale selection of one representative site for labeling. Another respondent associated the high cost to produce two GMP-quality 14C radiolabels and conduct a larger human ADME trial as a drawback. More commonly, others cited the difficulty to analyze time-consuming datasets and provide clear data interpretation with one respondent with an unfavorable past experience that influenced their current practice. The challenge of such studies was also acknowledged by advocates, who cautioned the approach can cause confusion in protocol and data analysis and should be only considered in rare cases where strong scientific justification exists. A few correspondents referenced off-setting measures to reduce the need for a dual radiolabel strategy through synthesis of the non-radiolabeled metabolite allowing for quantification through traditional bioanalysis or application of alternative technologies like F-NMR to cover the non-radiolabeled metabolic fate.

Discussion

The impetus for TALG members to form a working group to investigate this topic was driven by a collectively identified need to benchmark, in a precompetitive manner, currently employed metID tools and methodologies. With this survey data, the working group can now evaluate current practices and perspectives within the small molecule biotransformation community with a goal of identifying common challenges and improving translational outcomes. The survey questions and their respective responses covered current in vitro and in vivo practices and perspectives on in vitro to in vivo correlation (IVIVC) from recent drug candidate programs within each company. The extensive breadth of questions posed does not enable a thorough analysis of each topic within this paper; however, the aspects of highest interest and relevance are presented and discussed.

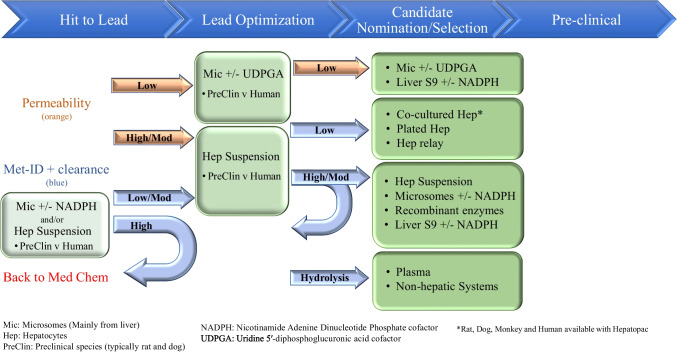

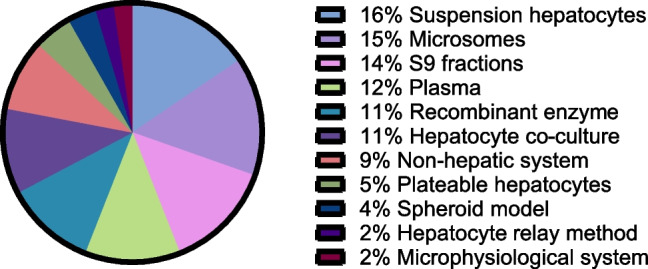

In vitro, the industry utilizes a wide variety of assay systems (Fig. 4). These assays vary significantly with respect to their technical complexity but can also vary in terms of their degree of physiological relevance and ability to recapitulate in vivo metabolism. The simplest case would be recombinant enzymes, which focus exclusively on the biochemical interaction between enzyme and substrate; the most complex case would be microphysiological systems (MPS), which seek to incorporate not only a heterogenous make-up of cell types attempting to reflect the normal tissue environment, but also may include fluid flow to recapitulate a dynamic physiological state. In addition to differences in the type of in vitro assay system employed, there is also significant variety in the experimental conditions used (Table I & Table II). Survey respondents cited a range of concentrations and incubation times per assay type, generally indicating a lack of consensus on optimal assay conditions. It was also revealed that not every company employs every type of in vitro assay. While suspension hepatocytes are unanimously utilized, only 3 out of 26 respondents (12%) utilize MPS models; the utilization rate for the rest of the assays are distributed between these two extremes. At face value, these results suggest that modern in vitro metID studies are based on individualized strategic deployment of various known tools and techniques. However, when viewed in the context of a typical modern drug candidate discovery and development process, additional dimensions emerge through which the survey data can be interpreted, revealing a more methodical, scientifically defensible process (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Type and prevalence of in vitro metID systems. Respondents were asked to select those in vitro metID systems they employ from those listed here. The data represent the relative number of respondents using each type of system.

Fig. 5.

The many in vitro metID assays in the context of discovery/development time-line and permeability/clearance. While there are many in vitro assays to choose from, when put into context of time-line and chemical properties of permeability and clearance, assay choice can be more prescriptive. CYP (cytochrome P450), UGT (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase), SULT (sulfotransferase), NAT (N-acetyltransferase).

The goal of conducting in vitro metID studies is to provide critical information regarding metabolite formation, with the level of intensity that tends to correspond to project phase, to enable impactful data-driven decisions. Most companies endeavor to strike a pragmatic balance between the complexity of the in vitro system used during a given project phase and assay throughput to optimize resources vs. need. For example, the use of liver microsomes for an early discovery program with high oxidative clearance may provide information regarding the structure-metabolism relationship and thereby influence design of more metabolically stable analogs. In a more mature program, or as other metabolic transformations are encountered, the project may require a more holistic evaluation of metabolism resulting in the use of hepatocytes. Another example would be a compound that shows little to no metabolic turnover in a microsomal incubation. In this case, plated hepatocytes co-cultured with stromal cells could be used for multi-day incubations, which have been demonstrated to increase metabolic turnover when compared to shorter duration/simpler systems [20, 21, 47]. Figure 5 depicts a decision tree for deciding which of the many in vitro metID assays can be employed with respect to project timeline and experimental situation, representing this working group’s synthesis of the survey results at large.

A key component of this survey was the assessment of metabolite IVIVC [48]. Survey questions evaluated the frequency of occurrence of six possible scenarios: (1) significant metabolite in vitro, major plasma metabolite in vivo; (2) significant metabolite in vitro, not observed or minor metabolite in vivo; (3) significant in vitro metabolite, secondary or downstream plasma metabolite in vivo; (4) significant in vitro metabolite, not observed in plasma, but major in excreta in vivo; (5) minor metabolite in vitro, major plasma metabolite in vivo; (6) minor metabolite in vitro, not observed or minor metabolite in vivo. These scenarios can be grouped according to degree of translatability (IVIVC) and potential negative impact on drug candidate program. Scenarios 1 and 6 reflect good translatability and no negative impact on a program; scenarios 3 and 4 reflect poor translatability, but little to no negative impact on a program; scenarios 2 and 5 reflect poor translatability, with scenario 5 potentially having significant negative impact on a program (Fig. 2A). The results indicate positive trends in responses and imply reasonably good predictivity in the scenarios that matter most in terms of regulatory concern (Fig. 2B-H). Most respondents experienced good predictivity for scenario 1, where major circulating metabolites in vivo were also significant metabolites in vitro (68% of respondents experienced this ≥ 50% of the time). Inversely, only a small minority of respondents cited experiencing scenario 5 most of the time, where a major circulating metabolite in vivo was a minor metabolite in vitro (13% of respondents experienced this ≥ 50% of the time). The spread in responses suggest each company’s experience may be unique and provokes speculation as to the cause. To that end, respondents were asked to select reasons for poorly predicting major human circulating metabolites in cases of poor prediction (Fig. 3). Three reasons were cited most often, and all relate to metabolite production within the in vitro system: either too little metabolism, too much metabolism, or extrahepatic metabolism not being taken into consideration. Notably, 35% of respondents stated, “this rarely happens,” which is consistent with the aforementioned results, but a similar number of respondents cited disposition-related issues for poor translatability. It would appear overall that in vitro models to support metabolism assessment perform well but have room for improvement. In some respects, our data are consistent with a recently published report, where, across 500 human ADME studies, disproportionate human metabolites exceeding the MIST threshold for further safety evaluation were rare; even rarer were unique human metabolites not observed preclinically in vitro or in vivo, representing less than 1% of total cases [49]. In other respects, our data probe additional in vitro-to-in vivo metabolite scenarios beyond what is present in the literature, providing important grounding for future work that may seek to improve translatability across the board (see scenarios 1 – 6, Fig. 2).

Ultimately, throughout the continuum of a small molecule development program, biotransformation scientists are responsible for elucidating the structural and quantitative aspects of metabolites formed in humans following administration of a drug candidate. Both mass spectrometry (MS/MS) and NMR are commonly employed to determine metabolite structures, and these approaches are relatively standardized. Quantifying metabolites, however, is not standardized, and a variety of analytical approaches are available that differ in frequency of use depending on project stage (Fig. 1). Up to and including Phase 1 clinical trials, MS response normalization, UV, DAD, or other spectroscopic techniques are used predominantly, with roughly equal frequency across the discovery stages which then drops off precipitously at Phase 2. Beyond Phase 1, it is most common to see quantification performed using either authentic standards or radiolabeling of drug. Despite the continued improvement of LC–MS-based quantification, including the radio-calibration technique [50] and MS response normalization software [51], there is a clear bias towards synthesizing authentic standards and using radiolabeled probes in clinical development. This implies that LC–MS alone is still not yet widely used as the definitive metID assay for regulatory filings. However, the frequency of use of MS response normalization in early discovery and development indicates a clear proclivity to apply this ubiquitous technology wherever possible within the metID purview. For a discussion on the role of metabolite bioanalysis in drug development, readers are directed to a recent publication from another IQ Working Group on this topic [52].

Conclusion & Future Perspective

The results of this survey reveal that a variety of approaches are currently being employed across the industry to address our common challenge of identifying major and minor metabolites prior to late-stage clinical development. Additionally, the data presented optimistically indicate that, although methods may differ from a strategic perspective between companies, the probability of discovering a major metabolite during advanced stages of clinical development is low. The potential opportunities for improving in vitro-to-in vivo metID translatability more broadly identified here provide an important starting point for future efforts in this area.

Acknowledgements

We thank the IQ Consortium and staff at Faegre Drinker for facilitating the conduct of this survey, with special thanks to Svetlana Lyapustina, Dede Godstrey, and Maja Leah Marshall. We also thank Mitchell Taub for constructive critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADME

Absorption/distribution/metabolism/excretion

- AMS

Accelerator mass spectrometry

- AO

Aldehyde oxidase

- CS

Candidate selection

- DAD

Diode array detector

- DDI

Drug-drug interaction

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- FIH

First in human

- FMO

Flavin-containing monooxygenase

- GMP

Good manufacturing practices

- HL

Hit-to-lead

- HRMS

High-resolution mass spectrometry

- LC–MS(/MS)

Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry

- LO

Lead optimization

- LSC

Liquid scintillation counting

- MAD

Multiple ascending dose

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- QSAR

Quantitative structure–activity relationship

- SAD

Single ascending dose

- UV

Ultraviolet

- XO

Xanthinoxidase

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the design, conduct, or analysis of this survey and its results.

Funding

There is no financial support to declare for this work. Administrative support was provided by the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (IQ).

Declarations

Conflict of Interests/Competing Interests

As this work is the result of an industry-wide consortium and the data are blinded with respect to participating companies’ survey responses, authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

John P. Savaryn, Email: john.savaryn@abbvie.com

Kevin Colizza, Email: kevin.x.colizza@gsk.com.

References

- 1.Trunzer M, Faller B, Zimmerlin A. Metabolic soft spot identification and compound optimization in early discovery phases using MetaSite and LC-MS/MS validation. J Med Chem. 2009;52(2):329–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kebamo S, Tesema S, Geleta B. The Role of Biotransformation in Drug Discovery and Development. J Drug Metabol Toxicol. 2015;6(196):2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanu-Wilson J, Evans L, Wrigley S, Steele J, Atherton J, Boer J. Biotransformation: Impact and Application of Metabolism in Drug Discovery. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11(11):2087–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weston DJ, Dave M, Colizza K, Thomas S, Tomlinson L, Gregory R, et al. A discovery biotransformation strategy: combining in silico tools with high-resolution mass spectrometry and software-assisted data analysis for high-throughput metabolism. Xenobiotica. 2022;52(8):928–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine R. Metabolic stability: main enzymes involved and best tools to assess it. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9(9):921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obach RS. Pharmacologically Active Drug Metabolites: Impact on Drug Discovery and Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65(2):578–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He C, Mao Y, Wan H. Preclinical evaluation of chemically reactive metabolites and mitigation of bioactivation in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2023;28(7):103621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Conference on Harmonisation. Non-Clinical Safety Studies for the Conduct of Human Clinical Trials for Pharmaceuticals, ICH Guidance M3(R2). 2009.

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: M3(R2) Nonclinical Safety Studies for the Conduct of Human Clinical Trials. 2010.

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Safety Testing of Drug Metabolites Guidance for Industry. 2020.

- 11.Ma S, Li Z, Lee KJ, Chowdhury SK. Determination of exposure multiples of human metabolites for MIST assessment in preclinical safety species without using reference standards or radiolabeled compounds. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(12):1871–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atrakchi AH. Interpretation and considerations on the safety evaluation of human drug metabolites. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22(7):1217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frederick CB, Obach RS. Metabolites in safety testing: “MIST” for the clinical pharmacologist. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(3):345–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schadt S, Bister B, Chowdhury SK, Funk C, Hop C, Humphreys WG, et al. A Decade in the MIST: Learnings from Investigations of Drug Metabolites in Drug Development under the “Metabolites in Safety Testing” Regulatory Guidance. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46(6):865–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia L, Liu X. The conduct of drug metabolism studies considered good practice (II): in vitro experiments. Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8(8):822–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalvie D, Obach RS, Kang P, Prakash C, Loi CM, Hurst S, et al. Assessment of three human in vitro systems in the generation of major human excretory and circulating metabolites. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22(2):357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson SJ, Bai A, Kulkarni AA, Moghaddam MF. Efficiency in Drug Discovery: Liver S9 Fraction Assay As a Screen for Metabolic Stability. Drug Metab Lett. 2016;10(2):83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hultman I, Vedin C, Abrahamsson A, Winiwarter S, Darnell M. Use of HmuREL Human Coculture System for Prediction of Intrinsic Clearance and Metabolite Formation for Slowly Metabolized Compounds. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(8):2796–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonn B, Svanberg P, Janefeldt A, Hultman I, Grime K. Determination of Human Hepatocyte Intrinsic Clearance for Slowly Metabolized Compounds: Comparison of a Primary Hepatocyte/Stromal Cell Co-culture with Plated Primary Hepatocytes and HepaRG. Drug Metab Dispos. 2016;44(4):527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang WW, Khetani SR, Krzyzewski S, Duignan DB, Obach RS. Assessment of a micropatterned hepatocyte coculture system to generate major human excretory and circulating drug metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(10):1900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan TS, Yu H, Moore A, Khetani SR, Tweedie D. Meeting the Challenge of Predicting Hepatic Clearance of Compounds Slowly Metabolized by Cytochrome P450 Using a Novel Hepatocyte Model. HepatoPac Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41(12):2024–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preiss LC, Lauschke VM, Georgi K, Petersson C. Multi-Well Array Culture of Primary Human Hepatocyte Spheroids for Clearance Extrapolation of Slowly Metabolized Compounds. AAPS J. 2022;24(2):41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riede J, Wollmann BM, Molden E, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Primary human hepatocyte spheroids as an in vitrotool for investigating drug compounds with low clearance. Drug Metab Dispos. 2021;49(7):501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Docci L, Milani N, Ramp T, Romeo AA, Godoy P, Franyuti DO, et al. Exploration and application of a liver-on-a-chip device in combination with modelling and simulation for quantitative drug metabolism studies. Lab Chip. 2022;22(6):1187–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulsharova G, Kurmangaliyeva A. Liver microphysiological platforms for drug metabolism applications. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(9):e13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanani T, Isherwood J, Issa E, Chung WY, Ravaioli M, Oggioni MR, et al. A Narrative Review of the Applications of Ex-vivo Human Liver Perfusion. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e34804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens LJ, Donkers JM, Dubbeld J, Vaes WHJ, Knibbe CAJ, Alwayn IPJ, et al. Towards human ex vivo organ perfusion models to elucidate drug pharmacokinetics in health and disease. Drug Metab Rev. 2020;52(3):438–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebner T, Wagner K, Wienen W. Dabigatran acylglucuronide, the major human metabolite of dabigatran: in vitro formation, stability, and pharmacological activity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(9):1567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Tang W. Drug metabolism in drug discovery and development. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8(5):721–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Timmerman P, Blech S, White S, Green M, Delatour C, McDougall S, et al. Best practices for metabolite quantification in drug development: updated recommendation from the European Bioanalysis Forum. Bioanalysis. 2016;8(12):1297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callegari E, Varma MVS, Obach RS. Prediction of Metabolite-to-Parent Drug Exposure: Derivation and Application of a Mechanistic Static Model. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(3):520–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav J, El Hassani M, Sodhi J, Lauschke VM, Hartman JH, Russell LE. Recent developments in in vitro and in vivo models for improved translation of preclinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics data. Drug Metab Rev. 2021;53(2):207–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson S, Luffer-Atlas D, Knadler MP. Predicting circulating human metabolites: how good are we? Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22(2):243–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loi CM, Smith DA, Dalvie D. Which metabolites circulate? Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41(5):933–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalgutkar AS, Gardner I, Obach RS, Shaffer CL, Callegari E, Henne KR, et al. A comprehensive listing of bioactivation pathways of organic functional groups. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6(3):161–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prakash C, Shaffer CL, Nedderman A. Analytical strategies for identifying drug metabolites. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26(3):340–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill KL, Houston JB, Galetin A. Characterization of in vitro glucuronidation clearance of a range of drugs in human kidney microsomes: comparison with liver and intestinal glucuronidation and impact of albumin. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(4):825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowland A, Elliot DJ, Knights KM, Mackenzie PI, Miners JO. The “albumin effect” and in vitro-in vivo extrapolation: sequestration of long-chain unsaturated fatty acids enhances phenytoin hydroxylation by human liver microsomal and recombinant cytochrome P450 2C9. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(5):870–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowland A, Knights KM, Mackenzie PI, Miners JO. The “albumin effect” and drug glucuronidation: bovine serum albumin and fatty acid-free human serum albumin enhance the glucuronidation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A9 substrates but not UGT1A1 and UGT1A6 activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(6):1056–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kameyama T, Sodhi JK, Benet LZ. Does Addition of Protein to Hepatocyte or Microsomal In Vitro Incubations Provide a Useful Improvement in In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation Predictability? Drug Metab Dispos. 2022;50(4):401–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulz JA, Stresser DM, Kalvass JC. Plasma protein-mediated uptake and contradictions to the free drug hypothesis: a critical review. Drug Metab Rev. 2023;55(3):205–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SJ, Lee KR, Miyauchi S, Sugiyama Y. Extrapolation of In Vivo Hepatic Clearance from In Vitro Uptake Clearance by Suspended Human Hepatocytes for Anionic Drugs with High Binding to Human Albumin: Improvement of In Vitro-to-In Vivo Extrapolation by Considering the “Albumin-Mediated” Hepatic Uptake Mechanism on the Basis of the “Facilitated-Dissociation Model.” Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47(2):94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li N, Badrinarayanan A, Ishida K, Li X, Roberts J, Wang S, et al. Albumin-Mediated Uptake Improves Human Clearance Prediction for Hepatic Uptake Transporter Substrates Aiding a Mechanistic In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) Strategy in Discovery Research. Aaps j. 2020;23(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin M, Ishida K, Liang X, Lai Y, Unadkat JD. Interpretation of Protein-Mediated Uptake of Statins by Hepatocytes Is Confounded by the Residual Statin-Protein Complex. Drug Metab Dispos. 2023;51(10):1381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mishra V, Heath RJ. Structural and Biochemical Features of Human Serum Albumin Essential for Eukaryotic Cell Culture. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ham SW, Park HJ, Lim DH. Studies on Menadione as an Inhibitor of the cdc25 Phosphatase. Bioorg Chem. 1997;25:33–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burton RD, Hieronymus T, Chamem T, Heim D, Anderson S, Zhu X, et al. Assessment of the Biotransformation of Low-Turnover Drugs in the HmicroREL Human Hepatocyte Coculture Model. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46(11):1617–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerny MA, Kalgutkar AS, Obach RS, Sharma R, Spracklin DK, Walker GS. Effective Application of Metabolite Profiling in Drug Design and Discovery. J Med Chem. 2020;63(12):6387–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kendrick JS, Oelke C, Laing C, Crossman L, Stow R, Webber C. The Changing Landscape for Human Absorption, Metabolism, and Excretion: Practical Experiences From a Data Analysis of 500 Studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;114(6):1196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yi P, Luffer-Atlas D. A radiocalibration method with pseudo internal standard to estimate circulating metabolite concentrations. Bioanalysis. 2010;2(7):1195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liigand J, Wang T, Kellogg J, Smedsgaard J, Cech N, Kruve A. Quantification for non-targeted LC/MS screening without standard substances. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li W, Vazvaei-Smith F, Dear G, Boer J, Cuyckens F, Fraier D, et al. Metabolite Bioanalysis in Drug Development: Recommendations from the IQ Consortium Metabolite Bioanalysis Working Group. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;115(5):939–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]