Abstract

Purpose

In this systematic review and individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis, we analysed the diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/CT in detecting primary tumours in patients with CUP and evaluated whether the location of the predominant metastatic site influences the diagnostic performance.

Methods

A systematic literature search from January 2005 to February 2024 was performed to identify articles describing the diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/CT for primary tumour detection in CUP. Individual patient data retrieved from original articles or obtained from corresponding authors were grouped by the predominant metastatic site. The diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/CT in detecting the underlying primary tumour was compared between predominant metastatic sites.

Results

A total of 1865 patients from 32 studies were included. The largest subgroup included patients with predominant bone metastases (n = 622), followed by liver (n = 369), lymph node (n = 358), brain (n = 316), peritoneal (n = 70), lung (n = 67), and soft tissue (n = 23) metastases, leaving a small group of other/undefined metastases (n = 40). [18F]FDG PET/CT resulted in pooled detection rates to identify the primary tumour of 0.74 (for patients with predominant brain metastases), 0.54 (liver-predominant), 0.49 (bone-predominant), 0.46 (lung-predominant), 0.38 (peritoneal-predominant), 0.37 (lymph node-predominant), and 0.35 (soft-tissue-predominant).

Conclusion

This individual patient data meta-analysis suggests that the ability of [18F]FDG PET/CT to identify the primary tumour in CUP depends on the distribution of metastatic sites. This finding emphasises the need for more tailored diagnostic approaches in different patient populations. In addition, alternative diagnostic tools, such as new PET tracers or whole-body (PET/)MRI, should be investigated.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00259-024-06860-1.

Keywords: Cancer of unknown primary, [18F]FDG PET/CT, Oncology, Molecular imaging, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) can be defined as histologically confirmed metastatic cancer in which standard diagnostic methods do not identify a primary tumour [1]. Approximately 2–5% of cancer cases worldwide are estimated to be CUP [2]. Because patients with CUP have metastatic disease, survival rates are abysmal, with a median survival of 2–12 months [3]. Adenocarcinomas account for approximately 70–80% of CUP, whereas the rest are undifferentiated, squamous, and neuroendocrine carcinomas [4]. Autopsy studies conducted before 2010 have shown that CUP mainly originates from lung cancer (27%) and pancreatic or hepatobiliary cancer (24% and 8%, respectively) [5]. However, the available diagnostic armamentarium per time period will affect such data.

Identifying the primary tumour allows for standard-of-care treatment options, potential inclusion in trials for identified primary tumours, and possibly other targeted therapies with a consequent positive impact on survival [6, 7]. Establishing guidelines for the diagnostic work-up remains challenging given the heterogeneous nature of CUP patients. Guidelines from the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) state that the minimal mandatory clinical work-up should consist of a thorough history and physical examination, basic blood analyses, and either computed tomography (CT) with an intravenous contrast agent or MRI scans of the head & neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis. Additional mammography is advised in women. Tissue sampling is required to allow histological and immunohistochemical analyses to guide the search for the underlying primary tumour [8]. If the routine diagnostic work-up fails to detect a primary tumour, tailored diagnostic strategies can be used, depending on patient characteristics, location of the metastases, and genetic profiling.

Whole-body 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose Positron Emission Tomography/ Computed Tomography ( [18F]FDG PET/CT) is a frequently used second-line imaging technique after CT in CUP patients, as it can aid in identifying the primary tumour and depicting the true extent of the disease. The ESMO guidelines currently recommend the use of [18F]FDG PET/CT to rule out additional manifestations in patients with single-site/oligometastatic CUP or in patients with cervical metastases that are likely to originate from head and neck cancers, mostly squamous cell carcinomas, which are highly hypermetabolic [8]. In the latter group, a recent systematic review found that [18F]FDG PET/CT had a pooled detection rate of primary tumours of 40% [9].

Due to the heterogeneous nature of CUP, other studies investigating the potential additional role of [18F]FDG PET/CT have mainly included mixed patient cohorts with various metastatic locations, histopathological features, and primary tumours. Using aggregate data from heterogeneous study populations typically limits the applicability of conventional systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as these do not account for the large heterogeneity in included cohorts. At the same time, large numbers of heterogeneous study populations provide a unique opportunity to group individual patients from individual cohorts into larger subgroups. This allows for more specific analyses of the role of [18F]FDG PET/CT in different subgroups of CUP patients.

This study aimed to perform a retrospective individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis of CUP patients to analyse the diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/CT for primary tumour detection rate in relation to the most predominant metastatic site and to map the distribution of underlying primary tumours for each subgroup.

Methods

This IPD systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Individual Participant Data (PRISMA-IPD) [10] guidelines and was registered in the prospective systematic review database PROSPERO under registration number CRD42023401409.

Literature search and inclusion criteria

A comprehensive search was conducted across multiple electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS) from 1 January 2005 to 14 February 2024 to identify all randomised controlled trials and retrospective cohort studies describing the diagnostic value of [18F]FDG PET/CT in CUP. The search strategy included the terms [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose, cancer of unknown primary and relevant synonyms or abbreviations. The entire search strategy is shown in Online Resource 1.

The titles, abstracts, and complete text reports of the retrieved studies were screened for eligibility. We considered studies eligible for inclusion if CUP was defined as histologically or radiologically confirmed solid or mucinous metastatic cancer and standard diagnostic methods (including CT) did not identify a primary tumour. Studies focusing solely on cervical lymph node metastases to identify occult head and neck tumours were excluded as this subgroup has already been addressed in a recent meta-analysis by Huasong et al. [9]. The reference lists of all included papers were cross-checked for additional relevant studies. Authors of papers that did not report individual patient data and authors of conference proceedings were contacted with a data request. In the case of no response, a reminder was sent three weeks after the initial attempt. Studies were excluded if individual patient data could not be retrieved. If a study assessed both PET only and PET/CT, patients with PET only (without CT) were excluded.

Quality assessment

The quality of all included published papers was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool [11]. The signalling questions tailored to this review are shown in Online Resource 2A.

Individual patient data analysis

Metastatic locations, primary tumour sites suggested by [18F]FDG PET/CT, and available reference standards were collected at the patient level. Individual patients were excluded from further analyses based on the following exclusion criteria: (a) patients with primarily cervical metastases; (b) patients not conforming to the definition of CUP as described in the previous section; and (c) patients who underwent PET only (without CT). The primary tumour diagnosis (if any) as established by [18F]FDG PET/CT was matched with the reference standard (established as described in the final column of Table 1) and classified as true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN), or Confirmed CUP (no diagnosis), using the following definitions:

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Study characteristics | Number of patients | [18F]FDG PET/CT | Reference standard | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Original paper | Patients included in this reviewa |

Activity(MBq)b | Uptake time(min) | |||

| 1 | Ambrosini [14] | 2006 | Italy | NR | 38 | 32 | 370 | 60–90 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 2 | Bicakci [15] | 2022 | Turkey | Retrospective | 125 | 92 | 250–370 | NR | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 3 | Budak [16] | 2020 | Turkey | Retrospective | 100 | 98 | 259–407 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 4 | Cengiz [17] | 2018 | Turkey | Retrospective | 121 | 93 | 270–370 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 5 | Deonarine [18] | 2013 | Scotland | Retrospective | 51 | 36 | 350–400 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 6 | Fencl [19] | 2007 | Czech Republic | Retrospective | 190 | 62 | 350–450 | 60–90 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 7 | Gutzeit [20] | 2005 | Germany | Retrospective | 45 | 27 | 350 | 60 | Histopathology | |

| 8 | Jain [21] | 2015 | India | Prospective | 86 | 86 | 185–245 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 9 | Koc [22] | 2018 | Turkey | Retrospective | 31 | 26 | 370 | NR | Histopathology | |

| 10 | Lawrenz [23] | 2020 | U.S.A. | Retrospective | 35 | 13 | NR | NR | NR | |

| 11 | Lee [24] | 2012 | Hong Kong | Retrospective | 58 | 39 | 370 | 45–50 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 12 | Li [25] | 2020 | China | Retrospective | 124 | 122 | 259 | 45–60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 13 | Mohamed [26] | 2021 | Egypt | Prospective | 39 | 39 | 175 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 14 | Nanni [27] | 2005 | Italy | Prospective | 18 | 17 | 370 | 60–90 | Histopathology | |

| 15 | Nikolova [28] | 2021 | Bulgaria | Retrospective | 53 | 14 | 270–370 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 16 | Ora [29] | 2022 | India | Retrospective | 50 | 24 | 259 | 60–90 | Histopathology & PET/CT appearance | |

| 17 | Ozkan [30] | 2016 | Turkey | Retrospective | 37 | 25 | 555 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 18 | Park, J.S [31]. | 2011 | Korea | Retrospective | 20 | 10 | 555–740 | 60–90 | Histopathology | |

| 19 | Park, S.B [32]. | 2018 | Korea | Retrospective | 103 | 85 | 385 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 20 | Pelosi [33] | 2006 | Italy | Retrospective | 68 | 40 | 222–370 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 21 | Rimer [34] | 2023 | Denmark | Retrospective | 159 | 106 | 280 | 45–75 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 22 | Saidha [35] | 2013 | India | Prospective | 50 | 34 | 350–425 | 60 | Histopathology | |

| 23 | Sivakumaran [36] | - | Australia | Retrospective | 147 | 93 | 252 | 60–75 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 24 | Soni [37] | 2021 | U.S.A. | Retrospective | 83 | 63 | 260–600 | 60–90 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 25 | Tamam (2012) [12] | 2012 | Turkey | Retrospective | 316 | 143 | 296–555 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 26 | Tamam (2016) [13] | 2016 | Turkey | Retrospective | 87 | 87 | 296–555 | 50 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 27 | Wang [38] | 2013 | China | Retrospective | 142 | 78 | 270–370 | 60–75 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 28 | Wolpert [39] | 2018 | Switzerland | Retrospective | 64 | 64 | NR | NR | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 29 | Yapar [40] | 2010 | Turkey | NR | 94 | 49 | 222–370 | 60–90 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 30 | Yoo [41] | 2020 | Korea | Retrospective | 74 | 51 | 385 | 50 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 31 | Yu [42] | 2016 | China | Retrospective | 449 | 99 | 282–330 | 60 | Histopathology & clinical FU | |

| 32 | Zidan [43] | 2020 | Egypt | Retrospective | 30 | 18 | 259 | 45–90 | Clinical & radiological FU | |

a Individual patients from the original study cohorts may have been excluded according to our exclusion criteria. b In the case of reported administered doses per kilogram, an average body weight of 70 kg was assumed. NR not reported; MBq megabecquerel; FU follow-up; min minute

TP: [18F]FDG PET/CT diagnosis of the primary tumour matched the final reference standard.

FP: [18F]FDG PET/CT diagnosis of the primary tumour did not match the final reference standard.

FN: no primary tumour was found on [18F]FDG PET/CT, but a primary tumour diagnosis was established using another method (e.g. colonoscopy, genomic profiling, etc.).

Confirmed CUP: no primary tumour was found on [18F]FDG PET/CT nor using any other methods, or during further follow-up(no diagnosis).

We divided the patients into eight subgroups based on the predominant metastatic site: bone, brain, liver, lung, lymph nodes, peritoneal, soft tissue, and ‘other’ metastases. To measure the diagnostic accuracy of [18F]FDG PET/CT, we considered the primary tumour detection rates (DRs), defined as the number of TP out of the number of subjects included, per study. For each subgroup, pooled DRs, corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), and prediction intervals were calculated. The random effects model considering the inverse variance method and logit transformed proportions was applied. The I2-statistic and τ2 were used to assess heterogeneity. A Sankey diagram was used to visualise the relationship between metastatic sites and primary tumours. Data analysis was performed using R Studio (version 6.2) and meta-analyses were conducted using the meta package.

Results

Studies

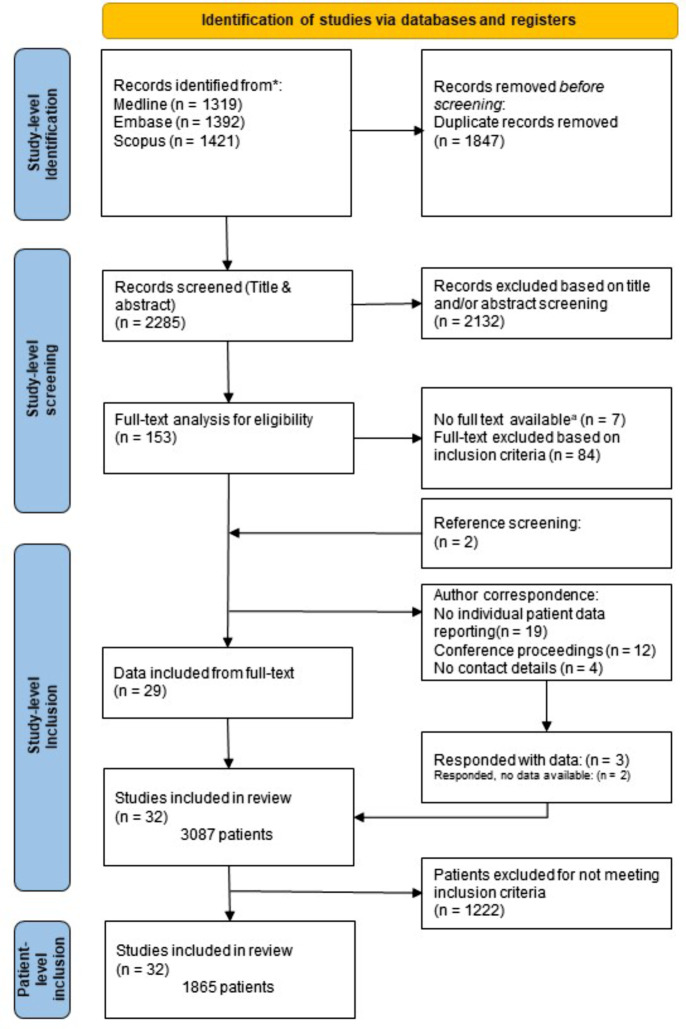

A total of 2285 unique studies were identified after searching Medline, Embase, and Scopus. Following title and abstract screening, 153 studies were assessed for full-text availability and eligibility for inclusion. Figure 1 shows the inclusion process, resulting in individual patient data of 1865 patients from 31 original studies and one conference proceeding. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Two studies had partially overlapping study populations, which were corrected by excluding overlapping patients from one study [12, 13].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart depicting the process of identifying relevant studies and inclusion of patients. aExcluding conference proceedings for which no full text is available by default

Quality assessment

Thirty-one of thirty-two studies had full-text availability. One conference proceeding was included and could not be assessed using the QUADAS-2 checklist [11]. The results are shown in Fig. 2. The full QUADAS-2 assessment on a per-study basis is shown in Online Resource 2B.

Fig. 2.

QUADAS-2 results: an overview of 31 studies with full-text availability

Patients

In total, 1865 patients from 32 studies were included in this analysis. The number of patients included in each study ranged from 10 to 143, with a median of 50 patients. In one study, only a part of the population underwent PET/CT, whereas the remaining participants were excluded because they underwent PET only [31]. The characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 2. The diagnostic workup that patients underwent prior to PET/CT was poorly documented in the majority of patients. In nine studies (460 patients), it was explicitly reported that patients had undergone an extensive diagnostic workup prior to [18F]FDG PET/CT, consisting of at least a CT scan, laboratory, and physical examinations. In the remaining studies, the extent of the pre-PET/CT diagnostic work-up was either not well defined or not reported (1405 patients).

Table 2.

Distribution of 1865 included patients according to predominant metastatic site and final primary tumour diagnosis

| Total | 1865 | |

|---|---|---|

| Predominant metastatic site | # | (%) |

| Bone | 622 | 33% |

| Liver | 369 | 20% |

| Lymph nodes | 358 | 19% |

| Thoracic | 164 | 9% |

| Abdominopelvic | 102 | 5% |

| Non-specified | 92 | 5% |

| Brain | 316 | 17% |

| Peritoneum | 70 | 4% |

| Lung | 67 | 4% |

| Soft tissue | 23 | 1% |

| Other | 40 | 2% |

| Final primary tumour diagnosis | # | (%) |

| Confirmed CUP | 607 | 33% |

| Lung/ bronchi | 546 | 29% |

| Colorectum | 101 | 5% |

| Esophagus/ stomach | 77 | 4% |

| Breast | 69 | 4% |

| Other/ non-specified | 59 | 3% |

| Prostate | 57 | 3% |

| Pancreas | 54 | 3% |

| Gynecological organs | 54 | 3% |

| Bile duct | 46 | 2% |

| kidney/ urothelial tract | 36 | 2% |

| Lymphoma | 37 | 2% |

| Bone/ sarcoma | 31 | 2% |

| Head & neck/ thyroid | 31 | 2% |

| Liver | 22 | 1% |

| Melanoma/ skin | 13 | 1% |

| Brain | 12 | 1% |

| Small bowel | 13 | 1% |

In most studies, the reference standard for determining the primary tumour was established by histopathology and/or clinical follow-up. In the case of positive findings, discovered lesions were typically biopsied to obtain histological confirmation, while in the case of negative findings, clinical follow-up was implemented as the main standard of reference to establish a definitive negative (CUP) diagnosis.

Detection rates of the primary tumour in relation to the predominant metastatic site

The pooled DRs of primary tumours varied between 0.74 (for patients with predominant brain metastases) and 0.35 (for patients with soft tissue metastases). Figure 3 shows a forest plot of the pooled DRs for each subgroup. Overall, a pooled detection rate of 0.54 (CI: [0.45; 0.64]) was found.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of pooled detection rates of [18F]FDG PET/CT across different patient subgroups according to the most predominant metastatic site. LN lymph nodes; TP true positives

Table 3 provides an overview of the [18F]FDG PET/CT results per predominant metastatic site group, including a specification of the types of primary tumour diagnoses. Overall (in 6/10 subgroups) lung cancer was the most frequently detected primary tumour, diagnosed in 29% of our total study population. The second and third most common primary tumour types were colorectal cancer (n = 101; 5%) and oesophageal and gastric cancers (n = 77; 4%). In the final columns, the heterogeneity of the results across the different studies is shown for each subgroup. A more detailed table of all primary tumours and corresponding classifications (TP/FP/FN/Confirmed CUP) is shown in in Online Resource 3.

Table 3.

Classification of [18F]FDG PET/CT findings (TP/FP/FN/CUP) and most common final diagnoses per subgroup. The final two columns show the measures of heterogeneity found in each subgroup

| Metastatic Site | Total | [18F]FDG PET/CT Classification | True primary tumours | Random effects model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | FN | CUP | Confirmed true primary | Confirmed CUP | τ 2 | I 2 | ||

| Brain | 316 | 246 (78%) | 11 (3%) | 6 (2%) | 53 (17%) | Lung: 193, brain: 13, esophagus/stomach: 7 | 61 (19%) | 1.1061 | 67% |

| Liver | 369 | 232 (63%) | 23 (6%) | 29 (8%) | 85 (23%) | Colorectum: 59, lung: 58, esophagus/stomach: 36 | 93 (25%) | 0.6425 | 71% |

| Lung | 67 | 32 (48%) | 6 (9%) | 10 (15%) | 19 (28%) | Lung: 21, CRC: 7 | 25 (37%) | 0.2713 | 27% |

| Bone | 622 | 348 (56%) | 37 (6%) | 77 (12%) | 160 (26%) | Lung: 216, prostate: 50, breast: 25 | 180 (29%) | 0.7319 | 76% |

| Soft tissue | 23 | 6 (26%) | 3 (13%) | 4 (17%) | 10 (43%) | Lung: 3, kidney/urology: 2. breast: 2 | 12 (52%) | 0 | 0% |

| Peritoneum | 70 | 23 (33%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (7%) | 41 (59%) | Colorectum: 9, gynecology: 7, esophagus/stomach : 6 | 42 (60%) | < 0.0001 | 4% |

| Other | 40 | 12 (30%) | 6 (15%) | 4 (10%) | 18 (45%) | Lung: 6, gynecology: 3 | 21 (53%) | 0.012 | 0% |

| Thoracic LN | 164 | 64 (39%) | 4 (2%) | 21 (13%) | 75 (46%) | Lung: 33, breast: 23, lymphoma: 7 | 78 (48%) | 0.4952 | 52% |

| Abdominopelvic LN | 102 | 34 (33%) | 6 (6%) | 10 (10%) | 52 (51%) | Lymphoma: 9, pancreas: 6, lung: 5 | 55 (54%) | 0.5317 | 35% |

| Not specified LN | 92 | 40 (43%) | 20 (22%) | 4 (4%) | 28 (30%) | Gynecology: 12, lung: 11, lymphoma: 4 | 40 (43%) | 1.6780 | 77% |

| Total | 1865 | 1037(56%) | 117(6%) | 170(9%) | 541(29%) | Lung: 546, colorectum: 101, esophagus/stomach: 77 | 607 (33%) | 1.0025 | 90% |

LN Lymph nodes; TP True positive; FP False positive; FN False negative; τ2 Variance of true effect sizes between studies ; I2 Percentage of total variability due to heterogeneity

Primary tumours

Overall, [18F]FDG PET/CT and follow-up revealed a primary tumour in 1258 out of 1865 patients (67%). In 1037 of these cases, the primary tumour was correctly identified by [18F]FDG PET/CT (pooled DR: 0.54), while in the remainder, follow-up revealed the primary tumour. Six hundred and seven (33%) patients were classified as having a confirmed CUP. Figure 4 presents a Sankey diagram visualising the corresponding primary tumours for each subgroup.

Fig. 4.

Sankey diagram: patients were grouped by metastatic sites on the left side. Flows and their relative sizes represent connections to the final diagnosis after [18F]FDG PET/CT and follow-up (true primary tumours or confirmed CUP). aThoracic lymph nodes; blymph nodes (not specified); cabdominopelvic lymph nodes. Figure created using https://sankeymatic.com/

Discussion

This review and meta-analysis of 1865 individual patient cases found an overall detection rate of 0.54 for [18F]FDG PET/CT in identifying primary tumours in patients with CUP. Interestingly detection rates varied considerably depending on the most predominant metastatic site, ranging from only 0.35–0.38 in patients with predominant soft tissue, lymph node and peritoneal metastases to as high as 0.74 in patients with predominant brain metastases. Detection rates for patients presenting primarily with bone, liver and lung metastases were in the intermediate range (0.46–0.54).

In 2017, a systematic review on the diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/CT in CUP by Burglin et al. [44] found a lower detection rate (0.41) than the pooled overall detection rate (0.54) we found in our current review. This discrepancy might be caused by the included studies: three out of four studies with the lowest detection rates in the previous review were not included in our current study, as these studies did not provide sufficient data for the per-metastasis analysis performed in our review [45–47].

Lung tumours constituted the largest subgroup of primary tumour diagnoses by far, comprising 29% of the cohort. It is known from literature that primary lung cancers are the leading cause of CUP, accounting for an estimated 27% of primary tumours [48].

Interestingly, our cohort had a significantly smaller number of primary pancreatic or hepatobiliary primary tumours than expected based on autopsy and genetic profiling studies [48]. Although it is difficult to draw firm conclusions, one hypothesis could be that [18F]FDG PET/CT has a relatively limited performance in detecting abdominal primary tumours. For instance, in peritoneal metastases, which are generally likely to originate from abdominal primary tumours, [18F]FDG PET/CT could be a suboptimal imaging modality given its relatively low detection rate of primary tumours in this subgroup [49]. The limited soft-tissue contrast of low-dose CT could limit its ability to distinguish peritoneal disease from the adjacent abdominal organs from which the cancer is disseminated. Similarly, abdominal (low-volume) primary cancers might be easily missed by [18F]FDG PET/CT because of low spatial resolution and partial volume effects or get lost in physiological FDG-uptake as observed in the colon or urological system. In addition, primary tumours with low FDG avidity, such as mucinous, signet ring cell, or low grade neuroendocrine cancers, can be missed more easily by [18F]FDG PET/CT, as these are not hypermetabolic [50–52]. In other patients with non-hypermetabolic metastases, identification of the primary tumour through [18F]FDG PET/CT may also pose a challenge, as this is an indication of primary tumours with slower metabolism. In addition, high glucose levels decrease the sensitivity of [18F]FDG PET/CT in general and should be taken into account when considering [18F]FDG PET/CT.

Current ESMO guidelines state the use of MRI as an alternative modality to CT in searching for a primary tumour, even though research on MRI in the setting of CUP is limited [8]. Therefore, in addition to identifying CUP patients that might benefit from [18F]FDG PET/CT, the potential role of MRI should also be investigated in future research. For instance, whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI (WB-DWI/MRI) has shown promising diagnostic accuracy in different types of gastrointestinal cancer and could be considered a diagnostic imaging modality for patients with metastases that are likely to originate from the abdomen or pelvis [53–56].

By categorising patients according to the predominant metastatic site, we aimed to provide insight into which patients with CUP might benefit the most from [18F]FDG PET/CT. The differences in detection rates observed across subgroups further highlight the heterogeneity of CUP patients and oppose the idea of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ diagnostic approach. As outlined above, our results suggest that [18F]FDG PET/CT might not be the most suitable imaging technique for each CUP patient, and that further tailoring of imaging according to the pattern of disease could be beneficial.

Novel imaging strategies should also be considered as potential diagnostic tools for CUP. As newer, whole-body PET/CT systems are now available, which will result in a better image quality and higher diagnostic accuracy (when not compensating for the better quality by decreasing the injected activity), while imaging the whole body including the legs, in only five minutes [57]. In addition, novel tracers, e.g. radiolabeled FAPI (Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor), might be superior to [18F]FDG in the detection of primary non-hypermetabolic tumours, like gastric, colorectal, biliary, hepatic and pancreatic cancer [58].

Apart from imaging, molecular(genetic) profiling techniques are emerging that could be of additional value in identifying the primary tumour in CUP patients. Over the past few years, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has gained popularity in clinical practice. Using an algorithm to generate profiles indicative of specific tumour types by genetic profiling of tissue samples taken from biopsies, WGS can point to a specific primary tumour [59]. The integration of different new diagnostic modalities, such as whole-body MRI and WGS algorithms, combined with a structural multidisciplinary approach, might further improve the diagnostic work-up of CUP patients.

This study has some limitations. First, as is common in CUP research, establishing consistent and valid reference standards is a major challenge, and it is difficult to evaluate the validity of the reference standards used in the individual studies included in this review. Likewise, it was difficult to determine the risk of bias in the included studies. Since CUP is not a clearly defined diagnosis but rather a diagnosis per exclusionem, patients who eventually enrol in studies such as those included in this review have experienced different diagnostic investigations and time paths during their disease course. Other variations between the included studies that limit the generalisability of our results include differences in the pre-[18F]FDG PET/CT diagnostic workup and therefore the availability of clinicopathological information at the time of PET/CT evaluation, as well as varying [18F]FDG PET/CT procedures (including patient preparation, blood glucose levels at the time of acquisition and field of view) and improvements in scanner systems, in terms of hardware and software throughout the years. Additionally, there was limited information available on the definition of predominant metastatic disease and the possible presence of metastatic sites in addition to the single site presented in the included articles, restricting this review to containing analyses of single site metastatic disease only. Finally, some subgroups in our study were relatively small, limiting the applicability of these results.

Conclusion

This individual patient data meta-analysis demonstrated that the detection rate of [18F]FDG PET/CT to identify the primary tumour in patients with CUP depends on the distribution of metastatic sites. Future studies should focus on exploring the potential of new diagnostic tools, including novel PET tracers, whole-body (PET/)MRI, and on further tailoring diagnostic strategies based on the predominant pattern of disease.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Conceptualization & Methodology: Jeroen Willemse, Max Lahaye, Doenja Lambregts; Literature search, Data Synthesis & Analysis: Jeroen Willemse, Sara Balduzzi, Winnie Schats, Max Lahaye; Writing - original draft preparation: Jeroen Willemse, Max Lahaye, Doenja Lambregts; Writing; Review, critical revision: Petur Snaebjornsson, Serena Marchetti, Marieke Vollebergh, Larissa van Golen, Zing Cheung, Wouter Vogel, Zuhir Bodalal, Sajjad Rostami, Oke Gerke, Tharani Sivakumaran, Regina Beets-Tan.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This is a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis, for which ethical approval is not required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Varadhachary GR, Raber MN. Cancer of unknown primary site. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:757–65. 10.1056/nejmra1303917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroten-Loef C, Verhoeven RHA, de Hingh I, van de Wouw AJ, van Laarhoven HWM, Lemmens V. Unknown primary carcinoma in the Netherlands: decrease in incidence and survival times remain poor between 2000 and 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:77–86. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemminki K, Bevier M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J. Survival in cancer of unknown primary site: population-based analysis by site and histology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1854–63. 10.1093/annonc/mdr536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379:1428–35. 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pentheroudakis G, Greco FA, Pavlidis N. Molecular assignment of tissue of origin in cancer of unknown primary may not predict response to therapy or outcome: a systematic literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:221–7. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raber MN, Faintuch J, Abbruzzese JL, Sumrall C, Frost P. Continuous infusion 5-fluorouracil, etoposide and cis-diamminedichloroplatinum in patients with metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Ann Oncol. 1991;2:519–20. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas I, Hoffmann TK, Engers R, Ganzer U. Diagnostic strategies in cervical carcinoma of an unknown primary (CUP). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:325–33. 10.1007/s00405-002-0470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer A, Bochtler T, Pauli C, Baciarello G, Delorme S, Hemminki K, et al. Cancer of unknown primary: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:228–46. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huasong H, Shurui S, Shi G, Bin J. Performance of 18F-FDG-PET/CT as a next step in the search of occult primary tumors for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Translational Imaging. 2021;9:361–71. 10.1007/s40336-021-00429-w. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and Meta-analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA. 2015;313:1657–65. 10.1001/jama.2015.3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamam MO, Mulazimoglu M, Guveli TK, Tamam C, Eker O, Ozpacaci T. Prediction of survival and evaluation of diagnostic accuracy whole body 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the detection carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:2120–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamam C, Tamam M, Mulazimoglu M. The Accuracy of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in the evaluation of bone lesions of undetermined origin. World J Nucl Med. 2016;15:124–9. 10.4103/1450-1147.176885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ambrosini V, Nanni C, Rubello D, Moretti A, Battista G, Castellucci P, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in the assessment of carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Radiologia Med. 2006;111:1146–55. 10.1007/s11547-006-0112-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Bicakci N. Diagnostic and prognostic value of F-18 FDG PET/CT in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. North Clin Istanbul. 2022;9:337–46. 10.14744/nci.2021.71598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budak E, Yanarates A. Role of < sup > 18 F-FDG PET/CT in the detection of primary malignancy in patients with bone metastasis of unknown origin. Revista Esp De Med Nuclear E Imagen Mol. 2020;39:14–9. 10.1016/j.remn.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cengiz A, Goksel S, Yurekli Y. Diagnostic value of < sup > 18 F-FDG PET/CT in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Mol Imaging Radionucl Therapy. 2018;27:126–32. 10.4274/mirt.64426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deonarine P, Han S, Poon FW, de Wet C. The role of 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the management of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Scot Med J. 2013;58:154–62. 10.1177/0036933013496958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fencl P, Belohlavek O, Skopalova M, Jaruskova M, Kantorova I, Simonova K. Prognostic and diagnostic accuracy of [18F]FDG-PET/CT in 190 patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Eur J Nuclear Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1783–92. 10.1007/s00259-007-0456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutzeit A, Antoch G, Kuhl H, Egelhof T, Fischer M, Hauth E, et al. Unknown primary tumors: detection with dual-modality PET/CT–initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234:227–34. 10.1148/radiol.2341031554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain A, Srivastava MK, Pawaskar AS, Shelley S, Elangovan I, Jain H, et al. Contrast-enhanced [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography as an initial imaging modality in patients presenting with metastatic malignancy of undefined primary origin. Indian J Nuclear Med. 2015;30:213–20. 10.4103/0972-3919.158529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koc ZP, Kara PO, Dagtekin A. Detection of unknown primary tumor in patients presented with brain metastasis by F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. CNS Oncol. 2018;7:CNS12. 10.2217/cns-2017-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrenz JM, Gordon J, George J, Haben C, Rubin BP, Ilaslan H, et al. Does PET/CT aid in detecting primary carcinoma in patients with skeletal metastases of unknown primary? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:2451–7. 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee RKL, Wang K, Ng AWH, Ip CB, Lam JSY, Yuen EHY, et al. Whole-body Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography-computed tomography for suspected or confirmed Brain Metastasis. Hong Kong J Radiol. 2012;15:80–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Li F, Li X, Qu L, Han J. Value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with hepatic metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary. Medicine. 2020;99:e23210. 10.1097/MD.0000000000023210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed DM, Kamel HA. Diagnostic efficiency of PET/CT in patients with cancer of unknown primary with brain metastasis as initial manifestation and its impact on overall survival. Egypt J Radiol Nuclear Med. 2021. 10.1186/s43055-021-00436-x. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nanni C, Rubello D, Castellucci P, Farsad M, Franchi R, Toso S, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET-CT imaging for the detection of an unknown primary tumour: preliminary results in 21 patients. Eur J Nuclear Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:589–92. 10.1007/s00259-004-1734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolova PN, Hadzhiyska VH, Mladenov KB, Ilcheva MG, Veneva S, Grudeva VV, et al. The impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the clinical management of patients with lymph node metastasis of unknown primary origin. Neoplasma. 2021;68:180–9. 10.4149/neo_2020_200315N263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ora M, Soni N, Nazar AH, Mehrotra A, Mishra P, Gambhir S. Effect of whole-body [18F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-2-d-glucose Positron Emission Tomography in patients with suspected brain metastasis. Indian J Neurosurg. 2022. 10.1055/s-0042-1743398. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozkan E, Soydal C, Araz M, Kucuk NO. Impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT for detecting primary Tumor Focus in patients with histopathologically proven metastasis. Int J Nuclear Med Res. 2016;3:56–62. 10.15379/2408-9788.2016.03.02.03. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park JS, Yim JJ, Kang WJ, Chung JK, Yoo CG, Kim YW, et al. Detection of primary sites in unknown primary tumors using FDG-PET or FDG-PET/CT. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:56. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SB, Park JM, Moon SH, Cho YS, Sun J-M, Kim B-T, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients without known primary malignancy with skeletal lesions suspicious for cancer metastasis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0196808. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelosi E, Pennone M, Deandreis D, Douroukas A, Mancini M, Bisi G. Role of whole body positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose in patients with biopsy proven tumor metastases from unknown primary site. Q J Nuclear Med Mol Imaging. 2006;50:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rimer H, Jensen MS, Dahlsgaard-Wallenius SE, Eckhoff L, Thye-Ronn P, Kristiansen C, et al. 2-[18F]FDG-PET/CT in Cancer of unknown primary Tumor-A Retrospective Register-based Cohort Study. J Imaging. 2023;9. 10.3390/jimaging9090178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Saidha NK, Ganguly M, Sidhu HS, Gupta S. The role of 18 FDG PET-CT in evaluation of unknown primary tumours. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4:236–41. 10.1007/s13193-013-0225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivakumaran T, Cardin A, Callahan J, Wong H-L, Tothill R, Hicks R, et al. Evaluating the utility of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/ computed tomography (CT) scan in cancer of unknown primary. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:3062–. 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.3062. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soni N, Ora M, Aher PY, Mishra P, Maheshwarappa RP, Priya S, et al. Role of FDG PET/CT for detection of primary tumor in patients with extracervical metastases from carcinoma of unknown primary. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:262–70. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, Wu Y, Zhang W, Li J, Wu P, Xie C. Clinical value of whole-body F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. J Med Imaging Radiation Oncol. 2013;57:65–71. 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolpert F, Weller M, Berghoff AS, Rushing E, Fureder LM, Petyt G, et al. Diagnostic value of < sup > 18 F-fluordesoxyglucose positron emission tomography for patients with brain metastasis from unknown primary site. Eur J Cancer. 2018;96:64–72. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yapar Z, Kibar M, Yapar AF, Paydas S, Reyhan M, Kara O, et al. The value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in carcinoma of an unknown primary: diagnosis and follow-up. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:59–66. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328332b340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo SW, Chowdhury MSA, Jeon S, Kang SR, Lee C, Jabin Z, et al. Clinical impact of F-18 FDG PET-CT on Biopsy Site Selection in patients with suspected bone metastasis of unknown primary site. Nuclear Med Mol Imaging. 2020;54:192–8. 10.1007/s13139-020-00649-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu X, Li X, Song X, Dai D, Zhu L, Zhu Y, et al. Advantages and disadvantages of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in carcinoma of unknown primary. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:3785–92. 10.3892/ol.2016.5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Zidan MA, Hassan RS, El-Noueam KI, Zakaria YM. Brain metastases assessment by FDG-PET/CT: can it eliminate the necessity for dedicated brain imaging? Egypt J Radiol Nuclear Med. 2020;51. 10.1186/s43055-020-00342-8.

- 44.Burglin SA, Hess S, Hoilund-Carlsen PF, Gerke O. 18F-FDG PET/CT for detection of the primary tumor in adults with extracervical metastases from cancer of unknown primary: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med (Baltim). 2017;96:e6713. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pak K, Kim SJ, Kim IJ, Nam HY, Kim BS, Kim K, et al. Clinical implication of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in carcinoma of unknown primary. Neoplasma. 2011;58:135–9. 10.4149/neo_2011_02_135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu M, Li MH, Kong L, Liu NB, Yang GR, Yu JM. [(18)F-FDG PET-CT in detecting the primary tumor in patients with metastatic cancers of unknown primary origin]. Chung-Hua Chung Liu Tsa Chih [Chinese J Oncology]. 2008;30:699–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Breuer N, Behrendt FF, Heinzel A, Mottaghy FM, Palmowski M, Verburg FA. Prognostic relevance of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in carcinoma of unknown primary. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:131–5. 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pentheroudakis G, Golfinopoulos V, Pavlidis N. Switching benchmarks in cancer of unknown primary: from autopsy to microarray. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2026–36. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coccolini F, Gheza F, Lotti M, Virzi S, Iusco D, Ghermandi C, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6979–94. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i41.6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berger KL, Nicholson SA, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA. FDG PET evaluation of mucinous neoplasms: correlation of FDG uptake with histopathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1005–8. 10.2214/ajr.174.4.1741005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dondi F, Albano D, Giubbini R, Bertagna F. 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT for the evaluation of gastric signet ring cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Nucl Med Commun. 2021;42:1293–300. 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Essen M, Sundin A, Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ. Neuroendocrine tumours: the role of imaging for diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:102 − 14. 10.1038/nrendo.2013.246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.De Vuysere S, Vandecaveye V, De Bruecker Y, Carton S, Vermeiren K, Tollens T, et al. Accuracy of whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI (WB-DWI/MRI) in diagnosis, staging and follow-up of gastric cancer, in comparison to CT: a pilot study. BMC Med Imaging. 2021;21:18. 10.1186/s12880-021-00550-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Lambregts DM, Maas M, Cappendijk VC, Prompers LM, Mottaghy FM, Beets GL, et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: current evidence in oncology and potential role in colorectal cancer staging. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2107-16. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Kim SJ, Lee JM, Kim H, Yoon JH, Han JK, Choi BI. Role of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of gallbladder cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;38:127 − 37. 10.1002/jmri.23956. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Gluskin JS, Chegai F, Monti S, Squillaci E, Mannelli L. Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Diffusion-Weighted MRI: Detection and Evaluation of Treatment Response. J Cancer. 2016;7:1565-70. 10.7150/jca.14582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Sun Y, Cheng Z, Qiu J, Lu W. Performance and application of the total-body PET/CT scanner: a literature review. EJNMMI Res. 2024;14:38. 10.1186/s13550-023-01059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Yang T, Ma L, Hou H, Gao F, Tao W. FAPI PET/CT in the Diagnosis of Abdominal and Pelvic Tumors. Front Oncol. 2021;11:797960. 10.3389/fonc.2021.797960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Schipper LJ, Samsom KG, Snaebjornsson P, Battaglia T, Bosch LJW, Lalezari F, et al. Complete genomic characterization in patients with cancer of unknown primary origin in routine diagnostics. ESMO Open. 2022;7:100611. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.