Abstract

Purpose of Review

The objective of this narrative review is to summarize data from recently published prospective observational studies that analyze the association between circulating interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels and cardiovascular clinical or imaging endpoints.

Recent Findings

Higher levels of IL-6 are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular death, major adverse cardiovascular events, myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and heart failure. Imaging studies have also shown an association between IL-6 and carotid intima-media thickness progression, carotid plaque progression, severity, and vulnerability. These observations have been consistent across a wide range of study populations and after adjusting for traditional and emerging risk factors including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Summary

Robust epidemiologic evidence supports IL-6 as a central mediator of cardiovascular risk along with human genetic studies and mechanistic experiments. Ongoing clinical studies are testing the therapeutic hypothesis of IL-6 inhibition in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or heart failure.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11883-024-01259-7.

Keywords: Interleukin-6, Inflammation, Cardiovascular outcomes, Risk prediction, Hs-CRP, Atherosclerosis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the US [1] and globally [2], highlighting the need for additional therapeutic approaches to address residual risk. Event rates from clinical trials remain high despite optimal medical management, particularly in patients with recurrent events, polyvascular disease, or acute heart failure (HF) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular event rates in selected very high-risk patient populations

| Patient population | Outcome | Event rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent events | MACE-3 | 9%/year | Fonarow 2021[3] |

| MACE-3 + MALE | 9%/year | Colantonio 2019[4] | |

| Polyvascular disease | MACE-4 | 10%/year (alirocumab arm) | Jukema 2019[5] |

| MACE-3 + MALE | 10%/year (ticagrelor arm) | Behan 2022[6] | |

| Acute heart failure | Cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization or urgent visit |

51 events/100 patient-years 18.6% at 6 months (sotagliflozin arm) |

Bhatt 2021[7] |

| All-cause death or heart failure hospitalization | 15.2% at 180 days (highintensity care arm) | Mebazaa 2022[8] |

MACE-3 major adverse cardiovascular events, inclusive of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, MACE-4, MACE-3 + hospitalization for unstable angina, MALE major adverse limb events, inclusive of acute limb ischemia, amputation for vascular cause

Converging evidence from human genetic [9–13], epidemiological [14, 15], and mechanistic [16, 17], studies as well as results of canakinumab [18, 19] and colchicine [20, 21] trials support the therapeutic potential of IL-6 pathway inhibition to lower the risk of CVD independent of traditional risk factors.

A major cause of CVD is atherosclerosis, which may include acute coronary syndrome (ACS), myocardial infarction (MI), stable or unstable angina, coronary artery disease (CAD), coronary or other arterial revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), carotid disease, and peripheral artery disease (PAD) [22, 23]. Atherosclerosis is characterized by deposition of apolipoprotein (Apo) B-containing lipoproteins (e.g., the atherogenic lipoproteins principally, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) in the arterial wall [24]. Subsequent retention, oxidation, aggregation, and engulfment of Apo-B lipoproteins by macrophages within the arterial wall can lead to chronic low-grade inflammation [25]. These inflammatory responses may also be further exacerbated by other conditions and lifestyle factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and physical inactivity [25].

The inflammatory responses underlying CVD progression implicate many immune cell types including macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, which secrete pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [26]. Specifically, inflammatory responses involve a series of complex interactions between different cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), interferon-γ (IFN-γ ), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), as well as a variety of interleukins (IL) including IL-1, -2, -4, -6, -7, -10, -12, -13, -17, and − 21 [26].

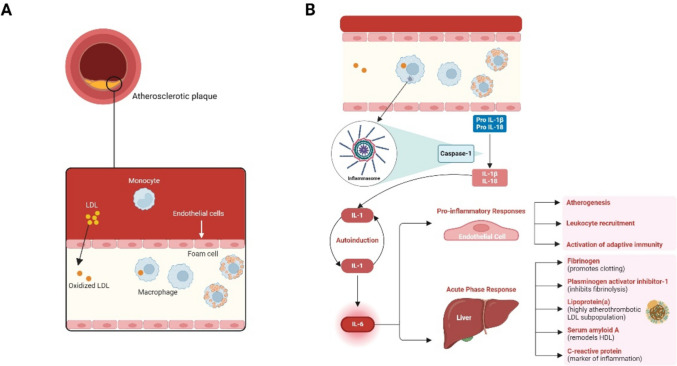

Among the inflammatory mediators, IL-6 is a key contributor to CVD pathophysiology. IL-6 is produced by macrophages, monocytes, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts [26–28], and plays a prominent role in promoting several aspects of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ASCVD mechanism of disease. Figure created with Biorender.com

In response to cholesterol and oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokines promote further recruitment of immune cells (e.g., macrophages, T-cells, B-cell) and subsequent secretion of additional proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, resulting in activation of endothelial cells and expression of cell adhesion molecules [29, 30]. IL-6 is also linked to increased uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages, contributing to foam cell formation [31].

Furthermore, IL-6 promotes the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells, as well as the secretion of extracellular matrix proteins, advancing plaque development [27]. It destabilizes plaques by inducing inflammation, thinning of the fibrous cap, and impairing collagen synthesis, thus making plaques more prone to rupture [31, 32]. This destabilization is further compounded by IL-6-induced expression of tissue factor, leading to a prothrombotic environment [32].

Given this, targeting IL-6 and its downstream pathways may represent a therapeutic strategy for preventing and treating atherosclerosis. To formally test the IL-6 hypothesis, well-powered cardiovascular outcome trials are currently ongoing and assessing anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in patients with ASCVD and chronic kidney disease (ZEUS [NCT05021835]), acute myocardial infarction (ARTEMIS [NCT06118281]), HF with preserved ejection fraction (HERMES [NCT05636176]), and end-stage kidney disease (POSIBIL6ESKD [NCT05485961]) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phase 2 and phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibodies for cardiovascular indications

| Phase | Anti-IL-6 mAb | Study | N | Study Population | Primary Endpoint(s) | Primary Completion (Est.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Pacibekitug (TOUR006) SC quarterly, SC monthly |

TRANQUILITY |

120 |

CKD and hs-CRP ≥ 2 mg/L |

Change from baseline in hsCRP at Day 90 | May 2025 |

| 3 | Ziltivekimab SC monthly |

ZEUS |

6,200 | ASCVD, CKD, and hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L | Time to first occurrence of 3-point MACE, a composite endpoint consisting of: CV death, non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke from randomization to end of study | September 2025 |

| 3 | Ziltivekimab SC monthly |

ATHENA |

680 | HFpEF and hs-CRP ≥ 2 mg/L | Change in KCCQ-CSS from randomization to Month 12 | June 2026 |

| 3 | Ziltivekimab SC monthly |

HERMES |

5,600 | HFpEF and hs-CRP ≥ 2 mg/L | Time to first occurrence of a composite heart failure endpoint consisting of: CV death, HF hospitalization or urgent HF visit from randomization to end of study | July 2027 |

| 3 | Ziltivekimab SC loading dose à SC monthly |

ARTEMIS |

10,000 | AMI | Time to first occurrence of 3-point MACE, a composite endpoint consisting of: CV death, non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke from randomization to end of study | September 2026 |

| 3 | Clazakizumab IV every 4 weeks |

POSIBIL6ESKD |

2,310 | ESKD, diabetes or ASCVD, and hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L | Time to first occurrence of CV death or MI | December 2028 |

AMI acute myocardial infarction, ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, CKD chronic kidney disease CV cardiovascular ESKD end-stage kidney disease HF heart failure HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein KCCQ-CSS Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score, mAb monoclonal antibody, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, RCT randomized controlled trial

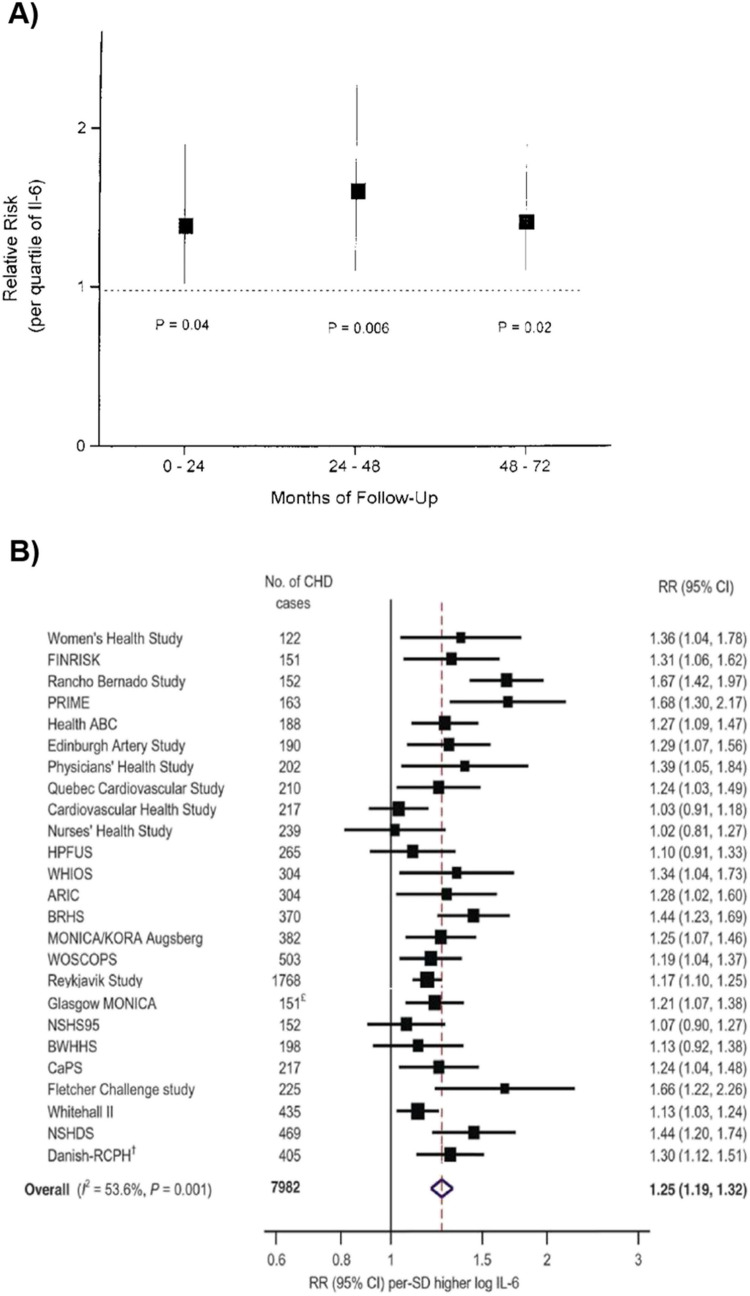

The objective of this narrative review is to summarize data from prospective observational studies published in the past decade that analyze the association between circulating IL-6 levels and cardiovascular clinical or imaging endpoints. A brief historical perspective highlighting earlier landmark studies is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Landmark epidemiological studies of IL-6 levels and cardiovascular outcomes. A The first report of an association between IL-6 and cardiovascular outcomes was published by Ridker at al. [29] in 2000 and showed a 38% increase in risk of myocardial infarction per quartile increase in IL-6. (B). A landmark meta-analysis of 29 prospective studies published by Kaptoge et al. [14] in 2014 showed a 25% increased risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction or coronary heart disease death per 1-SD higher level of IL-6

Methods

To identify relevant studies for inclusion in this narrative review, PubMed was searched for relevant articles from January 1, 2015, through August 15, 2024. Details on the search methodology are provided in the Supplement. Adjusted hazard, relative risk, and odds ratios are reported for each endpoint. Covariates for which analyses were adjusted are reported in the Supplement.

Association of IL-6 Levels with Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes

The associations between circulating IL-6 levels and cardiovascular death, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), MI and other coronary events, stroke, PAD, and HF are summarized in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, respectively.

Table 3.

Association of IL-6 with cardiovascular death

| Publication | Study Type | N | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patterson 2015[34] | Prospective cohort (CaPS) | 2,171 | 15.4b |

Alive: 1.86a CV death: 2.65a Non-CV death: 2.72a |

GP (men) | CV death HR per third of distribution: 1.24 (95% CI 1.08–1.43)c |

| Fanola 2016[35] |

RCT (SOLID-TIMI 52) |

4,939 | 2.5a | 2.02a | ACS | CV death HR Q4:Q4: 2.13 (95% CI 1.35–3.36)d |

| Held 2017[36] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a | 2.1a | Stable CHD | CV death Q4:Q1 HR: 2.15 (95% CI 1.53–3.04)e |

| Li 2017[37] | Meta-analysis | 9,087 | 3-15.3 | NA | GP | CV death RR highest vs. lowest quantile: 1.69 (95% CI 1.27–2.25) |

| Singh-Manoux 2017[38] | Prospective cohort (Whitehall II cohort) | 6,545 | 16.7b |

Alive: 1.38a Deceased: 1.84a |

GP | CV death HR per 1-SD increment: 1.19 (95% CI 1.02–1.39)f |

| Kalsch 2020[39] | Prospective cohort (LURIC) | 3,134 | 9.9a |

Without CAD: 2.5a With CAD: 3.5a |

Coronary angiography | CV death HR per 1-SD increment: 1.18 (95% CI 1.07–1.31)g |

| Gager 2020[40] | Prospective cohort | 322 | 6a |

Low: 1.8b High: 16.6b |

ACS | CV death HR ≥ vs. < 3.3 pg/mL: 8.60 (95% CI 1.07–69.32h |

| Li 2021[41] | Meta-analysis | 30,289 | 0.5–6.3 | NA | ACS | CV death RR: 1.55 (95% CI 1.06–2.28) |

| Perez 2021[42] |

RCT (ASCEND-HF) |

883 | 0.5 | 14.1a | Acute HF | CV death HR T3:T1: 3.23 (95% CI, 1.18–8.86)i |

| Chen 2023[43] | Meta-analysis | 8,370 | NA | NA | Hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis | CV death HR: 1.55 (95% CI 1.20–1.90) |

| Ferreira 2024[44] | Prospective cohort (MESA) | 6,614 | 14a | 1.21a | GP | CV death HR ≥ vs. < 1.2 pg/mL: 1.88 (95% CI 1.43–2.47)i |

| Khan 2024[45] |

Prospective cohort (MESA) |

6,622 | 14a | 1.21a | GP | CV death HR T3:T1: 1.55 (95% CI 1.05–2.30)k |

| Markousis-Mavrogenis 2019[46] | Prospective cohort (BIOSTAT-CHF) | 2,329 | 1.75a | 5.2a | HF | CV death HR per doubling: 1.16 (95% CI 1.09–1.24)l |

| Defilippi 2023[47] |

RCT (VICTORIA) |

4,652 | NA | 6.8a | HFrEF | CV death HR per 1-SD increment: 1.12 (95% CI 1.04–1.21)m |

| Mooney 2023[48] | Prospective cohort | 286 | 3.2b | 5.71a | Recent HFpEF hospitalization | CV death HR 1-log increment: 1.40 (95% CI 1.10–1.77)n |

| Batra 2021[49] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a |

Stage 1 CKD: 1.9a Stage 2 CKD: 2.0a Stage ≥ 3a CKD: 2.5a |

Chronic coronary syndrome and CKD |

CV death HR ≥ vs. < 2.0 pg/mL:o Stage 1 CKD 1.54 (95% CI 0.99–2.40); Stage 2 CKD 2.17 (95% CI 1.69–2.79); Stage ≥ 3a CKD 2.24 (95% CI 1.60–3.12) |

aMedian, bMean, c-oSee supplementary information

ACS acute coronary syndrome, ASCEND-HF Acute Study of Clinical Effectiveness of Nesiritide in Decompensated Heart Failure, BIOSTAT-CHF BIOlogy Study to TAilored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure, CAD coronary artery disease, CaPS Caerphilly Prospective Study, CHD coronary heart disease, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, GP general population, HF heart failure, HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFrEF heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HR hazard ratio, IL interleukin, LURIC Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health, MESA Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, NA not available, Q quartile, RCT randomized controlled trial, RR relative risk, SD standard deviation, SOLID-TIMI Stabilization of pLaques 14 usIng Darapladib-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, STABILITY Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy, T tertile, VICTORIA Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

Table 4.

Association of IL-6 with major adverse cardiovascular events

| Publication | Study Type | N | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spoto 2015[50] | Prospective cohort | 755 | 2.6b | 2.5a | CKD | MACE HR ≥ vs. < 2.5 pg/mL: 1.66 (95% CI 1.11–2.49)c |

| Fanola 2016[35] |

RCT (SOLID-TIMI 52) |

4,939 | 2.5a | 2.02a | ACS | MACE HR Q4:Q1: 1.57 (95% CI; 1.22–2.03)d |

| Held 2017[36] | RCT (STABILITY) | 14,611 | 3.7a | 2.1a | Stable CHD | MACE HR Q4:Q1: 1.59 (95% CI 1.29–1.97)e |

| Pareek 2017[51] | Prospective cohort (Malmo Preventive Project) | 1,324 | 8.6a | Without incident event: 3.30a With incident event: 4.04a | GP | MACE HR per 1-SD ln: 1.13 (95% CI 1.02–1.25)f |

| Kristono 2020[52] | Prospective cohort | 317 | 1 | 2.38a | Acute MI | MACE OR > vs. ≤ 3.11 pg/mL: 2.18 (95% CI 1.06–4.50)g |

| Ridker 2020[53] |

RCT (CIRT) |

4,168 | ≤ 5 | 2.5a | CAD or multivessel coronary disease, and T2D or MetS | MACE HR per quartile: 1.23 (95% CI 1.10–1.38)h |

| Batra 2021[49] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a |

Stage 1 CKD: 1.9a Stage 2 CKD: 2.0a Stage ≥ 3a CKD: 2.5a |

Chronic coronary syndrome and CKD |

MACE HR ≥ vs. < 2.0 pg/mL:i Stage 1 CKD 1.35 (95% CI 1.02–1.78); Stage 2 CKD 1.57 (95% CI 1.35–1.83); Stage ≥ 3a CKD 1.60 (95% CI 1.28–1.99) |

| Li 2021[41] | Meta-analysis | 30,289 | 0.3–6.3 | NA | ACS | MACE HR: RR 1.29 (95% CI 1.12–1.48) |

| Barrows 2022[54] | Prospective cohort (CRIC) | 3,031 | 10a | 1.9a | CKD | MACE HR per 1-quintile increase: 1.43 (95% CI 1.36–1.51)j |

| Ferencik 2022[55] |

RCT (PROMISE) |

1,796 | 2.1a | 1.8a | Suspected CAD by coronary CTA | MACE HR > vs. ≤ 1.8 pg/mL: 1.92 (95% CI 1.09–3.39)k |

| Koshino 2022[56] |

RCT (CANVAS) |

3,503 | 6.1a | 1.6a | T2D with CVD history or multiple CV risk markers | MACE HR per doubling of IL-6: 1.14 (95% CI 1.04–1.24)l |

| Jia 2023[57] | Prospective cohort (ARIC) | 5,672 | 7.2a | 3.0a | GP | MACE HR per 1-log increase: 1.57 (95% CI 1.44–1.72)m |

| McCabe 2023[58] | Meta-analysis | 8,420 | 0.25-10.8a | 2.0-25.2a | IS, TIA | MACE RR Q4:Q1: 1.35 (95% CI 1.09–1.67)n |

| Dirjayanto 2024[59] | Prospective cohort (ICON1) | 230 | 5 | 2.4a | Non-ST elevation ACS | MACE HR: 1.52 (95% CI 0.99–2.34)o |

| Ferreira 2024[44] | Prospective cohort (MESA) | 6,614 | 14a | 1.21a | GP | MACE HR ≥ vs. < 1.2 pg/mL: 1.44 (95% CI 1.25–1.64)p |

| Li 2024[60] | Prospective cohort | 290 | 2 |

No MACE: 3.36b MACE: 5.07b |

CAS | MACE HR: 1.27 (95% CI 1.12–1.64)q |

aMedian, bMean, c-qSee supplementary information

ACS acute coronary syndrome, ARIC Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, CAD coronary artery disease, CANVAS Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study, CAS carotid artery stenosis, CHD coronary heart disease, CI confidence interval, CIRT Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial, CKD chronic kidney disease, CRIC Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort, CTA computed tomography angiography, CV cardiovascular, CVD cardiovascular disease, GP general population, HR hazard ratio, ICON1 Improve Cardiovascular Outcomes in High Risk PatieNts with Acute Coronary Syndrome, IL interleukin, IS ischemic stroke, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, MESA Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, MetS metabolic syndrome, MI myocardial infarction, NA not available, OR odds ratio, PROMISE PROspective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of chest pain, Q quartile, RCT randomized controlled trial, RR relative risk, SD standard deviation, SOLID-TIMI Stabilization of pLaques usIng Darapladib-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, STABILITY Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy, T2D type 2 diabetes, TIA transient ischemic attack

Table 5.

Association of IL-6 with MI and other coronary events

| Publication | Study Type | N | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaptoge 2014[14] | Meta-analysis | 7,982 | 3.7-13.4a | NA | GP | Non-fatal MI or CHD death RR per 1-SD increment: 1.25 (95% CI 1.19–1.32) |

| Held 2017[36] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a | 2.1a | Stable CHD | MI HR Q4:Q1: 1.55 (95% CI 1.16–2.09)c |

| Ridker 2020[53] |

RCT (CIRT) |

4,168 | ≤ 5 | 2.5a | CAD or multivessel coronary disease, and T2D or MetS | MI HR per quartile: 1.20 (95% CI 1.04–1.38)d |

| Batra 2021[49] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a |

Stage 1 CKD: 1.9a Stage 2 CKD: 2.0a Stage ≥ 3a CKD: 2.5a |

Chronic coronary syndrome and CKD |

MI HR ≥ vs. < 2.0 pg/mL:e Stage 1 CKD 1.37 (95% CI 0.94–1.99); Stage 2 CKD 1.39 (95% CI 1.12–1.72); Stage ≥ 3a CKD 1.26 (95% CI 0.93–1.71) |

aMedian,bMean,c−eSee supplementary information

CAD coronary artery disease, CHD coronary heart disease, CI confidence interval, CIRT Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial, CKD chronic kidney disease, GP general population, HR hazard ratio, IL interleukin, MetS metabolic syndrome, MI myocardial infarction, NA not available, RCT randomized controlled trial, RR relative risk, SD standard deviation, STABILITY Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy, T2D type 2 diabetes

Table 6.

Association of IL-6 with stroke

| Publication | Study Type | N | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenny 2019[61] | Prospective cohort (REGARDS) | 30,237 | 5.4a |

No stroke: 3.7 Stroke: 4.5 |

GP | Stroke HR Q4:Q1: 2.0 (95% CI 1.2–3.1)c |

| Papadopoulos 2022[15] | Meta-analysis | 27,411 | 12.4a |

1.0-4.5a 1.2-16.9b |

GP (9 studies) ≥ 1 vascular risk factor (2 studies) |

Stroke RR per 1-SD log increase: 1.19 (95% CI 1.10–1.28) |

| McCabe 2023[58] | Meta-analysis | 8,420 | 0.25-10.8b | 2.0-25.2b | IS, TIA | Stroke RR Q4:Q1: 1.33 (95% CI 1.08–1.65)d |

| Li 2022[62] | Prospective cohort (CNSR-III) | 10,472 | 1 |

Male: 2.6 Female: 2.7 |

AIS, TIA | Stroke HR Q4:Q1: 1.36 (95% CI 1.13–1.64)e |

| Xu 2022[63] |

Prospective cohort (CNSR-III) |

2,537 | 1b | 3.2 | AIS, TIA | Stroke HR ≥ vs. < 5.44 pg/mL: 2.05 (95% CI 1.32–3.19)f |

| Held 2017[36] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7b | 2.1b | Stable CHD | Stroke HR Q4:Q1: 1.17 (95% CI 0.73–1.87)g |

| Ridker 2020[53] |

RCT (CIRT) |

4,168 | ≤ 5 | 2.5b | CAD or multivessel coronary disease, and T2D or MetS | Stroke HR per quartile: 1.17 (95% CI 0.90–1.53)h |

| Batra 2021[49] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7b |

Stage 1 CKD: 1.9b Stage 2 CKD: 2.0b Stage ≥ 3a CKD: 2.5b |

Chronic coronary syndrome and CKD |

Stroke HR ≥ vs. < 2.0 pg/mL:i Stage 1 CKD 0.96 (95% CI 0.47–1.95); Stage 2 CKD 1.39 (95% CI 1.00-1.92); Stage ≥ 3a CKD 1.49 (95% CI 0.90–2.47) |

| Jia 2023[57] | Prospective cohort (ARIC) | 5,672 | 7.2b | 3.0b | GP | Stroke HR per 1-log increase: 1.15 (95% CI 0.93–1.43)j |

| Dirjayanto 2024[59] | Prospective cohort (ICON1) | 230 | 5 | 2.4b | Non-ST elevation ACS | Stroke/TIA HR: 0.58 (95% CI 0.13–2.56)k |

aMean, bMedian, c-kSee supplementary information

ACS acute coronary syndrome, AIS acute ischemic stroke, ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, CAD coronary artery disease, CI confidence interval, CIRT Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial, CKD chronic kidney disease, CNSR-III Third China National Stroke Registry, GP general population, HR hazard ratio, IL interleukin, ICON1 Improve Cardiovascular Outcomes in High Risk PatieNts with Acute Coronary Syndrome, IS, ischemic stroke, MetS metabolic syndrome, Q quartile, RCT randomized controlled trial, REGARDS Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke, RR relative risk, SD standard deviation, STABILITY Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy, T2D type 2 diabetes, TIA transient ischemic attack

Table 7.

Association of IL-6 with peripheral artery disease

| Publication | Study Type | N | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDermott 2011[64] | Prospective cohort (WALCS II) | 368 | 3 | NA | PAD | Greater decline in walking performance (6MWT) with increasing IL-6 levels: lowest tertile for ≥ 75% of study visits − 21.4 ft; highest tertile for ≥ 75% of study visits − 76.8 ft (P = 0.013)c |

| Gremmels 2019[65] |

Prospective cohort (JUVENTAS) |

254 | 5.6 |

Event: 8.0b No event: 5.8b |

Severe limb ischemia | Amputation-free survival HR 1.35 (95% CI 1.06–1.71; p = 0.01)d |

| Marinho 2022[66] | Prospective cohort (CIRT) | 4,248 | ≤ 5 | 2.50a | CAD, and T2D or MetS | PAD HR Q4:Q1: 2.0e |

aMedian, bMean c−eSee supplementary information

6MWT 6-minute walk test, CAD coronary artery disease, CIRT Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial, HR hazard ratio, IL interleukin, MetS metabolic syndrome, NA not available, PAD peripheral artery disease, Q quartile, T2D type 2 diabetes, WALCS II Walking and Leg Circulation Study II

Table 8.

Association of IL-6 with heart failure

| Publication | Study Type | N | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fanola 2017[35] |

RCT (SOLID-TIMI 52) |

4,939 | 2.5a | 2.02a | ACS | HF hospitalization HR Q4:Q1: 3.1 (95% CI 1.81–5.33)c |

| Held 2017[36] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a | 2.1a | Stable CHD | HF hospitalization HR Q4:Q1: 2.37 (95% CI 1.34–4.18)d |

| He 2017[67] | Prospective cohort (CRIC) | 3,557 | 6.3b |

Stage 2 CKD: 1.09 Stage 3a CKD: 1.67 Stage 3b CKD: 2.08 Stage 4 CKD: 2.59 |

CKD | HF HR per 1-log increment: 1.15 (95% CI 1.05–1.25)e |

| de Boer 2018[68] | Prospective cohorts (CHS, FHS, MESA, PREVEND) | 22,756 | 12a.b |

MESA: 1.2a CHS: 1.66a |

GP | HF HR per 1-SD ln increment: 1.10 (95% CI 1.03–1.16)f |

| Markousis-Mavrogenis 2019[46] | Prospective cohort (BIOSTAT-CHF) | 2,329 | 1.75a | 5.2a | HF | HF hospitalization HR per doubling: 1.01 (95% CI 0.94–1.08)g |

| Albar 2022[69] | Prospective cohort (MESA) | 2,610 | 8.4a |

No HF: 1.54 HFpEF: 2.20 HFrEF: 1.98 |

GP |

HFpEF HR per doubling: 1.78 (95% CI 1.03–3.08)h HFrEF HR per doubling: 0.87 (95% CI 0.45–1.67)h |

| Vasques-Nóvoa 2022[70] | Prospective cohort (EDIFICA) | 164 | 0.5 | 17.4a | Acute HF | HF rehospitalization HR T3:T1: 3.69 (95% CI 1.26–10.8)i |

| Defilippi 2023[47] |

RCT (VICTORIA) |

4,652 | NA | 6.8a | HFrEF | HF hospitalization HR per 1-SD increment: 1.05 (95% CI 0.98–1.12)j |

| Michou 2023[71] | Prospective cohort (BASEL V) | 1,026 | 1 | 11.2a | Acute HF | HF hospitalization HR 75th vs. 25th percentile 1.00 (95% CI 0.998–1.002)k |

| Mooney 2023[48] | Prospective cohort | 286 | 3.2b | 5.71a | Recent HFpEF hospitalization | HF hospitalization HR 1-log increment: 1.24 (95% CI 1.01–1.51)l |

| Khan 2024[45] |

Prospective cohort (MESA) |

6,622 | 14a | 1.21a | GP | Incident HF HR T3:T1: 0.80 (95% CI 0.45–1.45)m |

| Batra 2021[49] |

RCT (STABILITY) |

14,611 | 3.7a |

Stage 1 CKD: 1.9a Stage 2 CKD: 2.0a Stage ≥ 3a CKD: 2.5a |

Chronic coronary syndrome and CKD |

HF hospitalization HR ≥ vs. < 2.0 pg/mL:n Stage 1 CKD 2.02 (95% CI 0.82–4.98); Stage 2 CKD 2.61 (95% CI 1.77–3.86); Stage ≥ 3a CKD 2.52 (95% CI 1.60–3.96) |

| Koshino 2022[56] |

RCT (CANVAS) |

3,503 | 6.1a | 1.6a | T2D with CVD history or multiple CV risk markers | HF hospitalization HR per doubling of IL-6: 1.35 (95% CI 1.16–1.57)o |

| Jia 2023[57] | Prospective cohort (ARIC) | 5,672 | 7.2a | 3.0a | GP | HF hospitalization HR per 1-log increase: 1.82 (95% CI 1.64–2.02)p |

aMedian,bMean,c−pSee supplementary information

ACS acute coronary syndrome, ARIC Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, BASEL Basics in Acute Shortness of Breath EvaLuation, BIOSTAT-CHF BIOlogy Study to TAilored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure, CHD coronary heart disease, CHS Cardiovascular Health Study, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, CRIC Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort, CV cardiovascular, CVD cardiovascular disease, EDIFICA Estratificação de Doentes com InsuFIciência Cardíaca Aguda, FHS Framingham Heart Study, GP general population, HF heart failure, HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, HFrEF heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, HR hazard ratio, IL interleukin, MESA Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, PREVEND Prevention of Renal and Vascular Endstage Disease, Q quartile, RCT randomized controlled trial, SD standard deviation, SOLID-TIMI Stabilization of pLaques usIng Darapladib-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, STABILITY Stabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Initiation of Darapladib Therapy, tertile, T2D type 2 diabetes, VICTORIA Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

Notably, Ferreira et al. analyzed the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and found IL-6 to be more strongly associated with atherosclerosis, HF, fatal outcomes, and aortic valve calcification compared to high-sensitivity (hs) C-reactive protein (CRP) [44]. IL-6 remained strongly associated with these outcomes independent of hs-CRP, whereas the inverse was not true. High IL-6 levels were associated with increased risk of 3P-MACE (a composite of cardiovascular death, stroke, or MI) regardless of hs-CRP levels, but high hs-CRP levels were associated with higher risk only in conjunction with high IL-6 levels [44].

Further, Ridker et al. reported similar findings based on data from the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT) [53]. For the endpoint of MACE (a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal MI), multivariable hazard ratios (95% CI; adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, body mass index, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and stratified on diabetes or metabolic syndrome) for IL-6 were 1.23 (1.10–1.38) and for hs-CRP were 1.12 (1.00-1.26) [53]. This difference was most pronounced with the risk of all-cause mortality: IL-6, 1.35 (1.15–1.59), and hs-CRP, 1.00 (0.85–1.17) [53].

Association of IL-6 Levels with Vascular Imaging Endpoints

Vascular imaging studies have also revealed significant relationships between IL-6 levels and atherosclerosis. The association between circulating IL-6 levels and progression of carotid artery plaque or intima-media thickness assessed by ultrasound are summarized in Table 9. No studies were identified to date that reported association of IL-6 levels and changes in coronary artery plaque burden assessed by coronary CT angiography.

Table 9.

Association of IL-6 levels with imaging endpoints

| Publication | Study Type | N | Baseline IL-6 (pg/mL) | Population | Duration (years) | Imaging method | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okazaki 2014[72] | Prospective cohort (OSACA2) | 210 | 1.36b | CVD or ≥ 1 risk factor: hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking | 9 | Carotid ultrasound | mmIMT progression β per 1SD increment: 0.17d |

| Eltoft 2018[73] | Case-control (Tromsø Study) | 703 |

No plaques: 2.66c Novel plaques: 2.84c Stable plaques: 2.80c Progression of plaques: 3.58c |

GP | 6 | Carotid ultrasound | Plaque progression OR per 1SD increase: 1.44 (95% CI 1.12–1.85)e |

| Kamtchum-Tatuene 2022[74] | Prospective cohort (CHS) | 4,334 |

No plaque progression at 5 years: 1.6b With plaque progression at 5 years: 1.6b |

GP ≥ 65 years | 5 | Carotid ultrasound | Plaque progression OR per log-IL-6 increment: 1.44 (95% CI 1.23–1.69)f |

aMean, bMedian, cGeometic mean, d−fSee supplementary information

CHS Cardiovascular Health Study, CI confidence interval, CVD cardiovascular disease, GP general population, IL interleukin, mmIMT mean-maximal intima-media thickness, OR odds ratio, OSACA2 Osaka Follow-up Study for Carotid Atherosclerosis part 2, SD standard deviation

Briefly, Okazaki et al. observed a significant association between average IL-6 levels and long-term progression (nine years) of carotid mean maximal intima-media thickness (mmIMT); this association was independent of baseline mmIMT, age, sex, and other traditional risk factors (e.g., body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, estimated glomerular filtration rate, LDL-C, glycoasylated hemoglobin, use of statins) (β = 0.17, P = 0.02) [72]. Additionally, in the population-based Tromsø Study, Eltoft et al. reported significant associations between IL-6 and plaque progression (defined as an increase in total plaque area [TPA] ≥ 7.8 mm2) following adjustment for traditional risk factors (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.12–1.85) [73].

Further, evidence from additional population-based imaging studies has supported IL-6 as a predictor of not only carotid plaque progression but also severity and vulnerability [73, 74]. Data from the Cardiovascular Health Study revealed significant associations between baseline log IL-6 and plaque severity (β = 0.09, P = 0.001), irrespective of other risk factors such as PAD, dyslipidemia, hypertension, history of stroke or TIA, and smoking [74]. Kamtchum-Tatuene et al. also reported a 12% increase in risk for plaque vulnerability per 1 standard deviation (SD) increase in log IL-6 [74]. After five years, each 1 SD increase in log IL-6 levels was also associated with a 24% increase in carotid plaque progression, thereby making IL-6 the topmost contributor to carotid plaque progression following dyslipidemia [74]. Collectively, these findings emphasize the potential importance and utility of IL-6 in predicting carotid plaque severity, vulnerability, and progression.

Comparing IL-6 and hs-CRP as a Biomarker for Cardiovascular risk

CRP has long been established as an informative inflammatory biomarker above and beyond traditional risk factors, largely due to the extensive body of epidemiological evidence demonstrating a significant association between CRP levels and a range of adverse cardiovascular events across diverse populations [75]. A recently published analysis of 27,939 initially healthy women followed for 30 years in the Women’s Health Study showed that hs-CRP was highly associated with incident MACE, with the highest quintile exhibiting a HR of 1.70 (95% CI 1.52–1.90), compared with HRs of 1.36 (95% CI 1.23–1.52) and 1.33 (95% CI 1.21–1.47) for LDL-C and Lp(a), respectively [76]. This widespread recognition has elevated CRP as an important biomarker in cardiovascular risk assessment, as evidenced by its incorporation into multiple prevention guidelines [77–79], most recently in the 2024 ESC Guidelines for Chronic Coronary Syndrome [80]. However, despite its clinical utility, CRP is not without its limitations. One of the most significant limitations is its role as a downstream marker in the inflammatory cascade, reflecting systemic inflammation rather than a proximal inflammatory mediator. This has been established by mechanistic experiments and human genetics studies which demonstrated no causal association between genetic variants of CRP and cardiovascular risk [81–83]. IL-6, on the other hand, occupies a more pivotal position in the inflammatory response. As a pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-6 is integral to the initiation and propagation of inflammatory processes. It not only acts at the early stages of inflammation but also stimulates the secretion of acute-phase proteins such as CRP. This upstream role of IL-6 in the inflammatory pathway suggests that it may provide a more direct and perhaps more clinically meaningful measure of inflammatory activity, particularly in the context of CVD. Importantly, human genetic studies have consistently demonstrated an association between IL-6 pathway inhibition and lower risk of ASCVD [10, 12, 13, 84].

Recent studies have reinforced the significance of IL-6 as a biomarker in cardiovascular risk assessment. Multiple associations have been documented between IL-6 levels and various indicators of atherosclerosis, such as coronary artery calcium (CAC), carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), and plaque burden [85, 86]. Investigations focusing on vascular imaging outcomes have also demonstrated more robust correlations between IL-6 levels and CIMT than those observed with hs-CRP [72]. CIMT is a well-established surrogate marker for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk, and the stronger relationship between IL-6 and CIMT further reinforces the idea that IL-6 may provide a more accurate reflection of underlying vascular inflammation and atherosclerotic burden.

As mentioned, unlike hs-CRP, IL-6 is directly involved in the inflammatory processes that contribute to CVD. Consistent with this framework, recent studies have demonstrated a stronger association of IL-6 compared with hs-CRP for cardiovascular risk, as evidenced by findings from CIRT [53], MESA [44] and CANTOS [19, 87]. In CIRT, the association between IL-6 and MACE was numerically greater than that between hs-CRP and MACE (HR per quartile 1.23 vs. 1.12) [53]. Moreover, high IL-6 levels contributed to risk prediction above and beyond high levels of hs-CRP. Similarly, in MESA, IL-6 was more strongly and consistently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, such as MACE, HF, and all-cause mortality, even when accounting for traditional risk factors and hs-CRP levels [44]. Adding IL-6 to traditional risk models like the Pooled Cohort Equations significantly improves risk reclassification [88], highlighting its potential to enhance cardiovascular risk prediction and help guide more targeted interventions. In joint analysis, when levels of IL-6 and hs-CRP were discordant (e.g., IL-6 ≥ median and hs-CRP < median), risk of MACE tracked with IL-6 (Fig. 3). Finally, on-treatment IL-6 levels were more closely related to cardiovascular event rates than on-treatment hs-CRP levels in the CANTOS trial of canakinumab [19, 87]. Compared to placebo, the MACE HR for lowest tertile IL-6 and the lowest tertile hs-CRP were 0.65 (95% CI 0.53–0.81) and 0.75 (0.66–0.85), respectively, in fully adjusted models [87].

Fig. 3.

Patients with high IL-6 experience higher risk of cardiovascular events, irrespective of hs-CRP levels

Moreover, McCabe et al. observed that IL-6 exhibited a stronger association with the risk of recurrent stroke compared to hs-CRP, underscoring the potential of IL-6 as a more sensitive biomarker for identifying patients at elevated risk for recurrent cerebrovascular events [58]. The closer ties of IL-6 to the inflammatory pathways directly involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, along with its stronger associations with clinical outcomes such as recurrent stroke and subclinical measures like CIMT, highlight its greater specificity and sensitivity as a predictor of cardiovascular events. This evidence positions IL-6 as a potentially more reliable and informative marker for guiding preventive strategies and therapeutic interventions in the management of CVD.

Despite the promising role of IL-6 in CVD risk prediction, the clinical application of IL-6 as a biomarker faces significant challenges due to the lack of validated assays beyond standard blood concentration measurements. This gap presents a critical opportunity for the development of targeted assays and standardized approaches to timing of sample collection that can more accurately and reliably assess IL-6 levels, potentially enhancing current methods of CVD risk stratification. However, several key obstacles must be addressed to fully harness the potential of IL-6 in clinical practice.

One of the primary challenges in assessing IL-6 is its inherently low and highly variable concentration in the bloodstream. In healthy individuals, IL-6 levels typically range from 4.6 to 5.7 pg/mL on average, with a notable increase observed with advancing age [89]. However, there is considerable variability, with levels ranging from as low as 0 pg/mL to as high as 43.5 pg/mL in some healthy subjects [89]. This contrasts with hs-CRP, where levels are generally stable and typically ≤ 10 mg/L [75]. The variability in IL-6 levels is further compounded by its sensitivity to postprandial, exercise, and diurnal fluctuations [90]. Unlike CRP, which remains relatively stable following food intake, IL-6 levels can significantly increase after meals, making fasting status an important consideration for accurate measurement [91–93]. Likewise, IL-6 may rise acutely in response to exercise, with a lower, but appreciable, secondary increase during the post-exercise recovery phase [94]. Additionally, IL-6 exhibits diurnal variation, with levels generally lowest in the morning and peaking later in the day [35]. These variations can complicate the interpretation of IL-6 levels and require careful consideration of the timing of sample collection. Moreover, the plasma half-life of IL-6 is relatively short, less than six hours, compared to other biomarkers such as hs-CRP, which has a half-life of 18 to 20 h [33, 75]. This short half-life means that IL-6 levels can change rapidly, adding another layer of complexity to its use as a biomarker for chronic conditions like CVD. Standardization of timing, such as obtaining early-morning fasting levels without recent strenuous exercise, may help improve IL-6 assessment for cardiovascular risk.

Despite these challenges, the central role of IL-6 in the inflammatory pathways that drive the initiation, progression, and destabilization of atherosclerotic disease positions it as not only a promising predictive biomarker but also as a potential therapeutic target. Advances in assay development that can overcome the current limitations of IL-6 measurement could lead to more precise and actionable insights into cardiovascular risk, potentially transforming the landscape of preventive cardiology.

Conclusions

Accumulating evidence highlights inflammation as a key driver of CVD. A recent analysis of > 445,000 patients with the 19 most common autoimmune disorders showed a higher risk of a broad spectrum of CVD, including ASCVD, HF, aortic aneurysm, and arrhythmia [95]. Among various inflammatory pathways, the targeting and inhibition of IL-6 is supported by triangulation from multiple sources of data, including the epidemiological studies summarized herein. Ongoing cardiovascular outcome trials will clarify the potential therapeutic benefit and benefit–risk profile of anti-IL-6 mAbs.

Further research is needed to clarify downstream mechanisms of IL-6 inhibition relevant to CVD and to identify predictive biomarkers that may enrich therapeutic options for patients with greater potential for cardiovascular benefit. Prapiadou et al. reported that CXCL10 (CXC motif chemokine ligand 10) may be a downstream causal mediator for IL-6 signaling on ASCVD [96]. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), the presence of clonally expanded acquired leukemogenic mutations detectable by sequencing peripheral leukocytes, has been associated with greater MACE reduction with genetically proxied IL-6 pathway inhibition [97] and pharmacological inhibition with the anti-IL-1β mAb canakinumab [98]. Pericoronary fat attenuation index (pFAI), a CT-based measure of coronary inflammation, has been significantly associated with MACE and cardiovascular mortality beyond clinical risk stratification and coronary plaque burden [99]. While ongoing cardiovascular outcome trials rely primarily on hs-CRP, future trials may incorporate IL-6, CHIP, or pFAI as additional or alternative predictive biomarkers to enrich for patients more likely to benefit from targeted anti-inflammatory therapies.

Key References

- Ferreira JP, Vasques-Novoa F, Neves JS, Zannad F, Leite-Moreira A: Comparison of interleukin-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein for cardiovascular risk assessment: Findings from the MESA study. Atherosclerosis 2024, 390:117461.

- Patients with atherosclerosis who have higher IL-6 levels are at greater risk for cardiovascular events irrespective of hs-CRP levels.

- Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Glynn RJ, Bradwin G, Hasan AA, Rifai N: Comparison of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as biomarkers of residual risk in contemporary practice: secondary analyses from the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial. Eur Heart J 2020, 41(31):2952–2961.

- Despite current prevention and treatment options, IL-6, hs-CRP, and LDL remain strong predictors of major recurrent cardiovascular events.

- Khan MS, Talha KM, Maqsood MH, et al.: Interleukin-6 and Cardiovascular Events in Healthy Adults: MESA. JACC Adv 2024, 3(8):101,063.

- Across different racial and ethnic groups, higher circulating IL-6 levels are associated with worse CV outcomes and increased all-cause mortality.

- Papadopoulos A, Palaiopanos K, Bjorkbacka H, et al.: Circulating Interleukin-6 Levels and Incident Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. Neurology 2022, 98(10):e1002-e1012.

- Based on available population-based studies, high circulating IL-6 levels are associated with higher long-term risk of incident ischemic stroke.

- Batra G, Ghukasyan Lakic T, Lindback J, et al.: Interleukin 6 and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Chronic Coronary Syndrome. JAMA Cardiol 2021, 6(12):1440–1445.

- Elevated IL-6 levels along with CKD staging may improve identification of patients with chronic coronary syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Writing support was provided by Talisa Silzer, PhD, of Sixsense Strategy Group and Raya Mahbuba, MSc, from Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the work and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the draft and critical revision of the work. All authors have read and approved this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding was received for this project.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

NNM has served as a consultant for receiving and received grants/other payments from AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, AMGEN, Astra Zeneca, Abcentra, Tourmaline, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Sun Pharmaceuticals and Celgene. EdG is an employee of Tourmaline Bio, Inc. MDS is supported by institutional grants from Amgen, Arrowhead, Boehringer Ingelheim, 89Bio, Esperion, Novartis, Ionis, Merck, New Amsterdam, and Cleerly. MDS has participated in Scientific Advisory Boards with Amgen, Agepha, Ionis, Novartis, New Amsterdam, and Merck. MDS has also served as a consultant for Ionis, Novartis, Regeneron, Aidoc, Shanghai Pharma Biotherapeutics, Kaneka, Novo Nordisk, Arrowhead, and Tourmaline.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

No human or animal subjects by the authors were used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/10/2025

The original version of this paper has been updated. In the Acknowledgements section of the article, the family name Mahbuba was mistakenly listed as Mahuba.

References

- 1.Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Anderson RN. Leading causes of death in the US, 2019–2023. JAMA. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Cesare M, Perel P, Taylor S, Kabudula C, Bixby H, Gaziano TA, et al. The heart of the World. Glob Heart. 2024;19(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonarow GC, Kosiborod MN, Rane PB, Nunna S, Villa G, Habib M, et al. Patient characteristics and acute cardiovascular event rates among patients with very high-risk and non-very high-risk atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2021;44(10):1457–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colantonio LD, Shannon ED, Orroth KK, Zaha R, Jackson EA, Rosenson RS, et al. Ischemic event rates in very-high-risk adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(20):2496–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jukema JW, Szarek M, Zijlstra LE, de Silva HA, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, et al. Alirocumab in patients with polyvascular disease and recent acute coronary syndrome: ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(9):1167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behan SA, Mulder H, Rockhold FW, Gutierrez JA, Baumgartner I, Katona BG, et al. Impact of polyvascular disease and diabetes on limb and cardiovascular risk in peripheral artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(17):1781–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mebazaa A, Davison B, Chioncel O, Cohen-Solal A, Diaz R, Filippatos G, et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10367):1938–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai T, Zhang Y, Ho YL, Link N, Sun J, Huang J, et al. Association of Interleukin 6 receptor variant with cardiovascular disease effects of Interleukin 6 receptor blocking therapy: a phenome-wide Association study. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(9):849–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgakis MK, Malik R, Gill D, Franceschini N, Sudlow CLM, Dichgans M. Interleukin-6 Signaling effects on ischemic stroke and other Cardiovascular outcomes: a mendelian randomization study. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13(3):e002872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgakis MK, Malik R, Li X, Gill D, Levin MG, Vy HMT, et al. Genetically downregulated interleukin-6 signaling is associated with a favorable cardiometabolic profile: a phenome-wide association study. Circulation. 2021;143(11):1177–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarwar N, Butterworth AS, Freitag DF, Gregson J, Willeit P, Gorman DN, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 82 studies. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swerdlow DI, Holmes MV, Kuchenbaecker KB, Engmann JE, Shah T, Sofat R, et al. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1214–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaptoge S, Seshasai SR, Gao P, Freitag DF, Butterworth AS, Borglykke A, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(9):578–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadopoulos A, Palaiopanos K, Bjorkbacka H, Peters A, de Lemos JA, Seshadri S, et al. Circulating Interleukin-6 levels and incident ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Neurology. 2022;98(10):e1002–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akita K, Isoda K, Sato-Okabayashi Y, Kadoguchi T, Kitamura K, Ohtomo F, et al. An Interleukin-6 receptor antibody suppresses atherosclerosis in Atherogenic Mice. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobara M, Noda K, Kitamura M, Okamoto A, Shiraishi T, Toba H, et al. Antibody against interleukin-6 receptor attenuates left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(3):424–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with Canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Everett BM, Libby P, Thuren T, Glynn RJ. Relationship of C-reactive protein reduction to cardiovascular event reduction following treatment with canakinumab: a secondary analysis from the CANTOS randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TSJ, et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1838–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, De Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;139(25):e1082–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, et al. 2021 Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of Dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(8):1129–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nayor M, Brown KJ, Vasan RS. The molecular basis of predicting Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. Circul Res. 2021;128(2):287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henein MY, Vancheri S, Longo G, Vancheri F. The role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(21):12906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Dhalla NS. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(2):1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villar-Fincheira P, Sanhueza-Olivares F, Norambuena-Soto I, Cancino-Arenas N, Hernandez-Vargas F, Troncoso R, et al. Role of Interleukin-6 in vascular health and disease. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:641734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su JH, Luo MY, Liang N, Gong SX, Chen W, Huang WQ, et al. Interleukin-6: a novel target for cardio-cerebrovascular diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:745061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfaddagh A, Martin SS, Leucker TM, Michos ED, Blaha MJ, Lowenstein CJ, et al. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020;4:100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Didion SP. Cellular and oxidative mechanisms associated with interleukin-6 signaling in the vasculature. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katkenov N, Mukhatayev Z, Kozhakhmetov S, Sailybayeva A, Bekbossynova M, Kushugulova A. Systematic review on the role of IL-6 and IL-1β in Cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Dev Disease. 2024;11(7):206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridker Paul M. Inhibiting Interleukin-6 to reduce cardiovascular event rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(15):1856–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of Interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101(15):1767–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson CC, Blankenberg S, Ben-Shlomo Y, Heslop L, Bayer A, Lowe G, et al. Which biomarkers are predictive specifically for cardiovascular or for non-cardiovascular mortality in men? evidence from the caerphilly prospective study (CaPS). Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:113–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fanola CL, Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jarolim P, Lukas MA, Bode C, et al. Interleukin-6 and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients after an acute coronary syndrome: observations from the SOLID-TIMI 52 (stabilization of plaque using darapladib-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 52) trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(10):e005637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Held C, White HD, Stewart RAH, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Hochman JS, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers Interleukin-6 and C-Reactive protein and outcomes in stable coronary heart disease: experiences from the STABILITY (stabilization of atherosclerotic plaque by initiation of darapladib therapy) trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(10):e005077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Liu W, Xie J. Circulating interleukin-6 levels and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the elderly population: a meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;73:257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Bell JA, Canonico M, Elbaz A, Kivimäki M. Association between inflammatory biomarkers and all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality. CMAJ. 2017;189(10):E384–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kälsch AI, Scharnagl H, Kleber ME, Windpassinger C, Sattler W, Leipe J, et al. Long- and short-term association of low-grade systemic inflammation with cardiovascular mortality in the LURIC study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(3):358–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gager GM, Biesinger B, Hofer F, Winter MP, Hengstenberg C, Jilma B, et al. Interleukin-6 level is a powerful predictor of long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Vascul Pharmacol. 2020;135:106806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Cen K, Sun W, Feng B. Predictive value of blood Interleukin-6 level in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Immunol Invest. 2021;50(8):964–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez AL, Grodin JL, Chaikijurajai T, Wu Y, Hernandez AF, Butler J, et al. Interleukin-6 and outcomes in acute heart failure: an ASCEND-HF substudy. J Card Fail. 2021;27(6):670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, Wang Y. Interleukin-6 levels can be used to estimate cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risk in dialysis patients: a meta-analysis and a systematic review. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11(4):e818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira JP, Vasques-Novoa F, Neves JS, Zannad F, Leite-Moreira A. Comparison of interleukin-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein for cardiovascular risk assessment: findings from the MESA study. Atherosclerosis. 2024;390:117461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan MS, Talha KM, Maqsood MH, Rymer JA, Borlaug BA, Docherty KF, et al. Interleukin-6 and Cardiovascular events in healthy adults: MESA. JACC Adv. 2024;3(8):101063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markousis-Mavrogenis G, Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Devalaraja M, Anker SD, Cleland JG, et al. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(8):965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Defilippi CR, Alemayehu WG, Voors AA, Kaye D, Blaustein RO, Butler J, et al. Assessment of biomarkers of myocardial injury, inflammation, and renal function in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the VICTORIA biomarker substudy. J Card Fail. 2023;29(4):448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mooney L, Jackson CE, Adamson C, McConnachie A, Welsh P, Myles RC, et al. Adverse outcomes associated with interleukin-6 in patients recently hospitalized for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2023;16(4):e010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batra G, Ghukasyan Lakic T, Lindback J, Held C, White HD, Stewart RAH, et al. Interleukin 6 and Cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and chronic coronary syndrome. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(12):1440–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spoto B, Mattace-Raso F, Sijbrands E, Leonardis D, Testa A, Pisano A, et al. Association of IL-6 and a functional polymorphism in the IL-6 gene with cardiovascular events in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pareek M, Bhatt DL, Vaduganathan M, Biering-Sørensen T, Qamar A, Diederichsen AC, et al. Single and multiple cardiovascular biomarkers in subjects without a previous cardiovascular event. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(15):1648–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kristono GA, Holley AS, Hally KE, Brunton-O’Sullivan MM, Shi B, Harding SA, et al. An IL-6-IL-8 score derived from principal component analysis is predictive of adverse outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Cytokine X. 2020;2(4):100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Glynn RJ, Bradwin G, Hasan AA, Rifai N. Comparison of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as biomarkers of residual risk in contemporary practice: secondary analyses from the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(31):2952–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barrows IR, Devalaraja M, Kakkar R, Chen J, Gupta J, Rosas SE, et al. Race, Interleukin-6, TMPRSS6 genotype, and cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(18):e025627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferencik M, Mayrhofer T, Lu MT, Bittner DO, Emami H, Puchner SB, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis, cardiac troponin, and interleukin-6 in patients with chest pain: the PROMISE trial results. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(8):1427–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koshino A, Schechter M, Sen T, Vart P, Neuen BL, Neal B, et al. Interleukin-6 and cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: New insights from CANVAS. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(11):2644–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia X, Buckley L, Sun C, Al Rifai M, Yu B, Nambi V, et al. Association of interleukin-6 and interleukin-18 with cardiovascular disease in older adults: atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30(16):1731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCabe JJ, Walsh C, Gorey S, Harris K, Hervella P, Iglesias-Rey R, et al. C-Reactive protein, interleukin-6, and vascular recurrence after stroke: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke. 2023;54(5):1289–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dirjayanto VJ, Martin-Ruiz C, Pompei G, Rubino F, Kunadian V. The association of inflammatory biomarkers and long-term clinical outcomes in older adults with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2024;409:132177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li B, Shaikh F, Zamzam A, Abdin R, Qadura M. Inflammatory biomarkers to predict major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with carotid artery stenosis. Med (Kaunas). 2024;60(6):997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jenny NS, Callas PW, Judd SE, McClure LA, Kissela B, Zakai NA, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and ischemic stroke risk: the REGARDS cohort. Neurology. 2019;92(20):e2375–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li J, Lin J, Pan Y, Wang M, Meng X, Li H, et al. Interleukin-6 and YKL-40 predicted recurrent stroke after ischemic stroke or TIA: analysis of 6 inflammation biomarkers in a prospective cohort study. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu J, Mo J, Zhang X, Chen Z, Pan Y, Yan H, et al. Nontraditional risk factors for residual recurrence risk in patients with ischemic stroke of different etiologies. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;51(5):630–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McDermott MM, Liu K, Ferrucci L, Tian L, Guralnik JM, Tao H, et al. Relation of interleukin-6 and vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 levels to functional decline in patients with lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(9):1392–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gremmels H, Teraa M, de Jager SCA, Pasterkamp G, de Borst GJ, Verhaar MC. A pro-inflammatory biomarker-profile predicts amputation-free survival in patients with severe limb ischemia. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marinho L, Aday AW, Cook NR, Morrison AR, Narula N, Narula J, et al. Interleukin-6 levels and cardiovascular events in the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial: consistent associations for incident coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral artery disease. JVS-Vascular Sci. 2022;3:419. [Google Scholar]

- 67.He J, Shlipak M, Anderson A, Roy JA, Feldman HI, Kallem RR, et al. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with chronic kidney disease: the CRIC (chronic renal insufficiency cohort) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5):e005336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Boer RA, Nayor M, deFilippi CR, Enserro D, Bhambhani V, Kizer JR, et al. Association of cardiovascular biomarkers with incident heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(3):215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Albar Z, Albakri M, Hajjari J, Karnib M, Janus SE, Al-Kindi SG. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure with reduced to preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2022;167:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vasques-Nóvoa F, Pedro Ferreira J, Marques P, Sergio Neves J, Vale C, Ribeirinho-Soares P, et al. Interleukin-6, infection and cardiovascular outcomes in acute heart failure: findings from the EDIFICA registry. Cytokine. 2022;160:156053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michou E, Wussler D, Belkin M, Simmen C, Strebel I, Nowak A, et al. Quantifying inflammation using interleukin-6 for improved phenotyping and risk stratification in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(2):174–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okazaki S, Sakaguchi M, Miwa K, Furukado S, Yamagami H, Yagita Y, et al. Association of interleukin-6 with the progression of carotid atherosclerosis: a 9-year follow-up study. Stroke. 2014;45(10):2924–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eltoft A, Arntzen KA, Wilsgaard T, Mathiesen EB, Johnsen SH. Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of progressive atherosclerosis in the carotid artery: the Tromsø Study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kamtchum-Tatuene J, Saba L, Heldner MR, Poorthuis MHF, de Borst GJ, Rundek T, et al. Interleukin-6 predicts carotid plaque severity, vulnerability, and progression. Circ Res. 2022;131(2):e22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ridker PM. Clinical application of C-Reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation. 2003;107(3):363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ridker PM, Moorthy MV, Cook NR, Rifai N, Lee IM, Buring JE, Inflammation, Cholesterol, Lipoprotein(a), and 30-Year cardiovascular outcomes in women. N Engl J Med. 2024. 10.1056/NEJMoa2405182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Myers GL, Rifai N, Tracy RP, Roberts WL, Alexander RW, Biasucci LM, et al. CDC/AHA workshop on markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: report from the laboratory science discussion group. Circulation. 2004;110(25):e545–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e563–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McPherson R, Frohlich J, Fodor G, Genest J. Canadian cardiovascular society position statement–recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(11):913–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, Rossello X, Adamo M, Ainslie J et al. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2024. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Zacho J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen JS, Grande P, Sillesen H, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated C-reactive protein and ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1897–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Noveck R, Stroes ES, Flaim JD, Baker BF, Hughes S, Graham MJ et al. Effects of an antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of C-reactive protein synthesis on the endotoxin challenge response in healthy human male volunteers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lane T, Wassef N, Poole S, Mistry Y, Lachmann HJ, Gillmore JD, et al. Infusion of pharmaceutical-grade natural human C-reactive protein is not proinflammatory in healthy adult human volunteers. Circ Res. 2014;114(4):672–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levin MG, Klarin D, Georgakis MK, Lynch J, Liao KP, Voight BF, et al. A missense variant in the IL-6 receptor and protection from peripheral artery disease. Circul Res. 2021;129(10):968–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jenny NS, Brown ER, Detrano R, Folsom AR, Saad MF, Shea S, et al. Associations of inflammatory markers with coronary artery calcification: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(1):226–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kablak-Ziembicka A, Przewlocki T, Sokołowski A, Tracz W, Podolec P. Carotid intima-media thickness, hs-CRP and TNF-α are independently associated with cardiovascular event risk in patients with atherosclerotic occlusive disease. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214(1):185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ridker PM, Libby P, MacFadyen JG, Thuren T, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, et al. Modulation of the interleukin-6 signalling pathway and incidence rates of atherosclerotic events and all-cause mortality: analyses from the Canakinumab anti-inflammatory thrombosis outcomes study (CANTOS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(38):3499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wainstein MV, Mossmann M, Araujo GN, Gonçalves SC, Gravina GL, Sangalli M, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-6 is predictive of coronary artery disease in intermediate risk overweight patients referred for coronary angiography. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Said EA, Al-Reesi I, Al-Shizawi N, Jaju S, Al-Balushi MS, Koh CY, et al. Defining IL-6 levels in healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(6):3915–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Docherty S, Harley R, McAuley JJ, Crowe LAN, Pedret C, Kirwan PD, et al. The effect of exercise on cytokines: implications for musculoskeletal health: a narrative review. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2022;14(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Blackburn P, Després JP, Lamarche B, Tremblay A, Bergeron J, Lemieux I, et al. Postprandial variations of plasma inflammatory markers in abdominally obese men. Obes (Silver Spring). 2006;14(10):1747–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nilsonne G, Lekander M, Akerstedt T, Axelsson J, Ingre M. Diurnal variation of circulating Interleukin-6 in humans: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0165799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schönknecht YB, Crommen S, Stoffel-Wagner B, Coenen M, Fimmers R, Stehle P, et al. Influence of a proinflammatory state on postprandial outcomes in elderly subjects with a risk phenotype for cardiometabolic diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(6):3077–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hennigar SR, McClung JP, Pasiakos SM. Nutritional interventions and the IL-6 response to exercise. Faseb j. 2017;31(9):3719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Conrad N, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, Goetschalckx L, Callender T, Cambridge G, et al. Autoimmune diseases and cardiovascular risk: a population-based study on 19 autoimmune diseases and 12 cardiovascular diseases in 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet. 2022;400(10354):733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prapiadou S, Živković L, Thorand B, George MJ, van der Laan SW, Malik R, et al. Proteogenomic data integration reveals CXCL10 as a potentially downstream causal mediator for IL-6 signaling on atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2024;149(9):669–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bick AG, Pirruccello JP, Griffin GK, Gupta N, Gabriel S, Saleheen D, et al. Genetic interleukin 6 signaling deficiency attenuates cardiovascular risk in clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation. 2020;141(2):124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Svensson EC, Madar A, Campbell CD, He Y, Sultan M, Healey ML, et al. TET2-Driven clonal hematopoiesis and response to Canakinumab: an exploratory analysis of the CANTOS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(5):521–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chan K, Wahome E, Tsiachristas A, Antonopoulos AS, Patel P, Lyasheva M, et al. Inflammatory risk and cardiovascular events in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: the ORFAN multicentre, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2024;403(10444):2606–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.