Abstract

Purpose

As the importance of the patient’s perspective on treatment outcome is becoming increasingly clear, the availability of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) has grown accordingly. There remains insufficient information regarding the quality of PROMs in patients with soft-tissue sarcomas (STSs). The objectives of this systematic review were (1) to identify all PROMs used in STS patients and (2) to critically appraise the methodological quality of these PROMs.

Methods

Literature searches were performed in MEDLINE and Embase on April 22, 2024. PROMs were identified by including all studies that evaluate (an aspect of) health-related quality of life in STS patients by using a PROM. Second, studies that assessed measurement properties of the PROMs utilized in STS patients were included. Quality of PROMs was evaluated by performing a COSMIN analysis.

Results

In 59 studies, 39 PROMs were identified, with the Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) being the most frequently utilized. Three studies evaluated methodological quality of PROMs in the STS population. Measurement properties of the TESS, Quick Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH) and European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30) were reported. None of the PROMs utilized in the STS population can be recommended for use based on the current evidence and COSMIN analysis.

Conclusion

To ensure collection of reliable outcomes, PROMs require methodological evaluation prior to utilization in the STS population. Research should prioritize on determining relevant content and subsequently selecting the most suitable PROM for assessment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11136-024-03755-4.

Keywords: Soft-tissue sarcoma, Patient-reported outcome measure, Patient-reported outcome, Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments, COSMIN, Review

Introduction

Sarcomas are rare malignancies originating from mesenchymal tissues and can be divided in bone and soft-tissue sarcomas (STSs). The incidence of STSs is 4–5/100,000/year in Europe [1] and increasing in the ageing population [2]. Median age at presentation is 65 years [1, 3]. There is a range of clinical presentations for STSs, which challenges specialists to provide optimal patient care. Treatment therefore takes place in medical centers with a specialized multidisciplinary tumor board [4] and consists of a patient-tailored combination of surgical resection, radiotherapy (RT) and/or chemotherapy [1]. All of these treatments potentially cause treatment-related morbidity, for instance impaired wound healing, stiffness, pain and reduced mobility [5–8].

Research in the STS population has focused on multimodality treatments to achieve optimal oncological outcomes while striving to reduce treatment-related morbidity. Among other achievements, this has led to a shift in the timing of RT from postoperative to preferably preoperative, employing smaller radiation fields and lower total RT dosages [9]. In most studies, treatment-related morbidity is defined as functional outcome following surgery. Functional outcome can be determined from the doctors’ perspective, but increased awareness of the value of the patient’s perspective has resulted in the utilization of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in STS patients [8]. PROMs are questionnaires reported directly by the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else [10]. PROMs serve as tools for assessing patient-reported outcomes (PROs), which may pertain to different aspects of health-related quality of life, such as functional status or mental wellbeing, or offer a comprehensive evaluation of health-related quality of life.

One of the most widely used PROMs to measure outcome in patients with musculoskeletal tumors is the Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) [11], which was developed in 1996. In addition to functional status, STS diagnosis and subsequent interventions impact other aspects of the multidimensional concept health-related quality of life, as elucidated by Wilson and Cleary [12]. Various generic [13–15] and disease-specific [16–18] PROMs have been employed to evaluate (aspects of) health-related quality of life of STS patients. While selecting a reliable and valid PROM can be challenging due to the available options, it remains indispensable since understanding the diverse dimensions of health-related quality of life serves as the cornerstone of value-based healthcare [19].

The primary objective of this systematic review was to identify all PROMs utilized in the STS population. Secondarily, we aimed to methodologically evaluate the quality of these PROMs. By methodologically assessing PROMs, our goal was to determine their suitability in accurately capturing the experiences and outcomes of STS patients.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [20] and the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) guidelines [21, 22] The PRISMA checklist can be found in Supplementary Information 1.

Literature search

Two searches were conducted: one to identify all PROMs utilized in the STS population and another to find all studies reporting on measurement properties of these PROMs.

Eligibility criteria

For the identification of PROMs, all studies that involved (a) STS patients and evaluated (b) an aspect of health-related quality of life or health-related quality of life comprehensively by using a PROM were included for analysis. Studies were excluded when using a PROM as outcome measurement in a trial randomizing treatment and including patients younger than 18 years old. Studies utilizing PROMs in both STS and bone sarcoma patients were excluded if the results were not analyzed separately for each entity, along with studies not published in English.

According to the COSMIN guidelines, eligibility criteria for studies on the quality of PROMs include: (a) the target population, (b) the name(s) of the PROMs and (c) the evaluation of measurement properties. For finding studies that report on measurement properties, studies were considered eligible if they involved (a) STS patients, included (b) at least one of the PROMs used in the STS population and evaluated (c) at least one measurement property. Studies were excluded if they included both bone and STS patients for analysis due to significant clinical differences between these patient populations [1, 23], which would compromise the validity and reliability of measurement property assessments. Additionally, studies were excluded if full-text English was unavailable.

Search strategies

The search strategies were composed as follows:

The target population was defined as STS patients.

To identify all (names of the) PROMs used in the STS population, a separate search was conducted that consisted of (a) the target population and (b) the constructs of interest. This was defined as (a) STS patients and (b) (aspects of) health-related quality of life, with the same (c) exclusion filter as specified below (d).

Terwee et al. [24] developed a search filter capable of identifying all measurement properties.

The exclusion filter by Terwee et al. [24] was applied to eliminate irrelevant records from the searches, such as animal studies and conference abstracts.

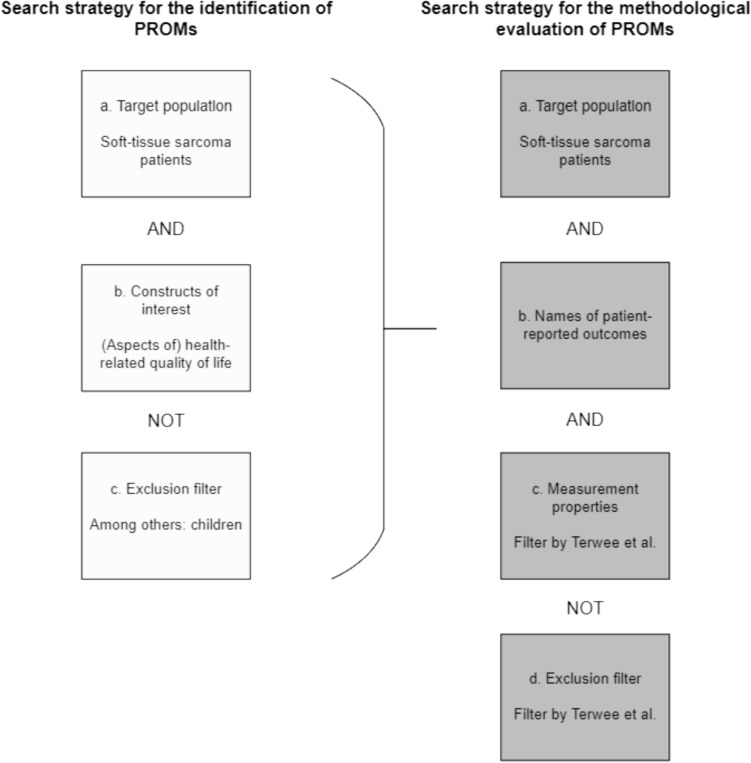

Refer to Fig. 1 for a schematic depiction outlining the composition of the searches. Supplementary Information 7 delineates the search strategy for the identification of PROMs (search 1) and the search strategy for the methodological evaluation of PROMs (search 2) employed in MEDLINE. Supplementary Information 2 provides the search strategies in Embase.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the composition of the search strategy for the identification of PROMs (search 1) and the search strategy for the methodological evaluation of PROMs (search 2)

Information sources

MEDLINE and Embase were searched on February 2nd 2023 and June 28th 2023. Search 1 took place on February 2nd 2023, whereas search 2 took place June 28th 2023. Both searches were updated on April 22nd 2024. Search strategies were composed by a senior librarian. After search 1, citation tracking was performed by reviewing reference lists of all reviews on PROs in the sarcoma population for eligible reports by hand. These reviews were identified using the elements (sarcoma) AND (patient-reported outcome), using the filters systematic review and review. Following search 2, the reference lists of all included studies were reviewed. No time limits or language restrictions were applied to the searches.

Selection process

For both searches, two reviewers (MRJ and JDG) independently assessed all records for eligibility. In cases of disagreement, consensus on which articles to screen full-text was achieved through discussion. If needed, a third reviewer (BvL) was consulted to make final decisions. The identical process was reiterated during the full-text review for inclusion. The searches were updated subsequent to the submission of this manuscript. A fourth reviewer, GvL, took over the role previously held by MRJ.

Data collection

All data were collected by one reviewer (JDG), with a second reviewer (MRJ) independently collecting data from 10% of randomly selected studies to check for discrepancies. Inter-rater reliability, assessed using Cohen’s kappa, was 0.88. Following the updated search, GvL assumed MRJ’s role, resulting in a Cohen’s kappa of 0.94. First, the data collection process took place for the studies included after search 1. By conducting data collection for these studies initially, all names of the PROMs utilized in the STS population were identified, facilitating search 2 aimed at finding studies on measurement properties of PROMs in the STS population. Relevant study and PROM characteristics were extracted using a data collection form.

Identification of patient-reported outcome measures

The author, title, year, and source of publication of the articles were recorded. Additionally, the study design, inclusion period, and specific characteristics of the patient population (such as stage of disease, age, and gender of patients) were extracted. The primary endpoint of the study, timing of evaluation using PROM(s), name and type of PROM used in the study, and corresponding construct were also reported.

Characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures

The first reference (development study) of each PROM used in the STS population was retrieved. The construct evaluated by the PROM was determined and it was reported whether the PROM was generic or disease-specific. Information such as the number of items, rating scale, item score, and total score were extracted from each PROM and recorded in the data collection form.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias of the studies included after search 1 was evaluated using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool of Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies [25, 26]. This involved answering 11 questions on methodology and rating the overall quality of each study. Question 10, 11 and 12 were deemed not applicable to the studies. Question 10 assesses repeated exposure measurement, which was not applicable since the exposure was either STS diagnosis or treatment, which would not change over time. Question 11 evaluates bias in outcome measures, which aligns with the objective of the systematic review. Question 12 pertains to blinding of outcome assessors, which was not applicable as outcome measures were patient-reported. Risk of bias assessment was conducted independently by two reviewers (MRJ and JDG). Any discrepancies in assessment were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer (BvL) making final decisions if necessary. Following the updated search, GvL assumed MRJ’s role.

Methodological assessment of patient-reported outcome measures

The COSMIN database for systematic reviews on outcome measurement instruments was searched; no previous systematic reviews on the measurement properties of PROMs in the STS population were found.

The COSMIN manual defines multiple measurement properties, divided in the domains reliability, validity and responsiveness [21]. For each included study identified through the second search, the evaluated measurement properties were determined. It is possible for multiple measurement properties of a single PROM to be evaluated within one study. These identified measurement properties were assessed individually.

Content validity, considered the most important measurement property of a PROM, is defined as the degree to which an instrument is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured [22]. Quality of evaluation of content validity was assessed by using a separate manual; the COSMIN manual for assessing content validity [22]. Content validity was assessed in the review by (a) appraising the development quality of PROMs which were developed involving STS patients and (b) evaluating the quality of content validity studies conducted in STS patients. For all included PROMs, the development study was retrieved. If these studies involved STS patients, the quality was evaluated using the standards for evaluating the quality of the PROM design (item generation) and standards for evaluating the quality of a cognitive interview study or other pilot test. For available content validity studies in the STS population, quality was assessed by rating five parts: asking patients about relevance of the PROM; asking patients about the comprehensiveness of the PROM; asking patients about the comprehensibility of the PROM; asking professionals about the relevance of the PROM and asking professionals about the comprehensiveness of the PROM.

For all measurement properties other than content validity, the methodological quality of each assessment was established using the COSMIN risk of bias checklist [21]. Methodological flaws were evaluated by assigning ratings to standards for each measurement property (very good, adequate, doubtful, or inadequate). The overall quality was determined by the lowest rating among all standards in the checklist. In addition, data concerning the study population, disease characteristics, instrument administration and interpretability were gathered from the included studies. Subsequently, the study results were compared with the criteria for good measurement properties as outlined in the COSMIN manual. These were rated as sufficient (+), insufficient (−) or indeterminate (?). See Table 1 for an overview of the criteria for good measurement properties.

Table 1.

Criteria for good measurement properties

| Measurement property | Ratinga | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Structural validity | + |

CTT CFA: CFI or TLI or comparable measure > 0.95 OR RMSEA < 0.06 OR SRMR < 0.08 IRT/Rasch No violation of unidimensionality: CFI or TLI or comparable measure > 0.95 OR RMSEA < 0.06 OR SRMR < 0.08 AND No violation of local independence: residual correlations among the items after controlling for the dominant factor < 0.20 OR Q3’s < 0.37 AND No violation of monotonicity: adequate looking graphs OR item scalability > 0.30 AND Adequate model fit: IRT: χ2 > 0.01 Rasch: infit and outfit mean squares ≥ 0.5 and ≤ 1.5 OR Z-standardized values > − 2 and < 2 |

| ? |

CTT: Not all information for ‘+’ reported IRT/Rasch: Model fit not reported |

|

| − | Criteria for ‘+’ not met | |

| Internal consistency | + | At least low evidence for sufficient structural validity AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) ≥ 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or subscale |

| ? | Criteria for “at least low evidence for sufficient structural validity not met” | |

| − | At least low evidence for sufficient structural validity AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) < 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or subscale | |

| Reliability | + | ICC or weighted Kappa ≥ 0.70 |

| ? | ICC or weighted Kappa not reported | |

| − | ICC or weighted Kappa < 0.70 | |

| Measurement error | + | SDC or LoA < MIC |

| ? | MIC not defined | |

| − | SDC or LoA > MIC | |

| Hypotheses testing for construct validity | + | The result is in accordance with the hypothesis |

| ? | No hypothesis defined | |

| − | The result is not in accordance with the hypothesis | |

| Cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance | + | No important differences found between group factors (such as age, gender, language) in multiple group factor analysis OR no important DIF for group factors (McFadden’s R2 < 0.02) |

| ? | No multiple group analysis OR DIF analysis performed | |

| − | Important differences between group factors OR DIF was found | |

| Criterion validity | + | Correlation with gold standard ≥ 0.70 OR AUC ≥ 0.70 |

| ? | Not all information for ‘+’ reported | |

| − | Correlation with gold standard < 0.70 OR AUC < 0.70 | |

| Responsiveness | + | The result is in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC ≥ 0.70 |

| ? | No hypothesis defined | |

| − | The result is not in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC < 0.70 |

a“+” = sufficient, “?” = indeterminate, “−” = insufficient

CTT classical test theory, CFA confirmatory factor analysis, CFI comparative fit index, TLI Trucker-Lewis Index, RMSEA root mean square error of approximation, SRMR standardized root mean residuals, IRT item response theory, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient, SDC smallest detectable change, LoA limits of agreement, MIC minimal important change, DIF differential item functioning, AUC area under the curve

Results

Study selection

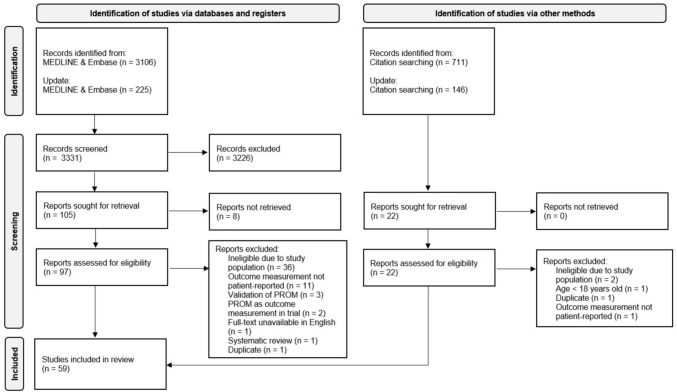

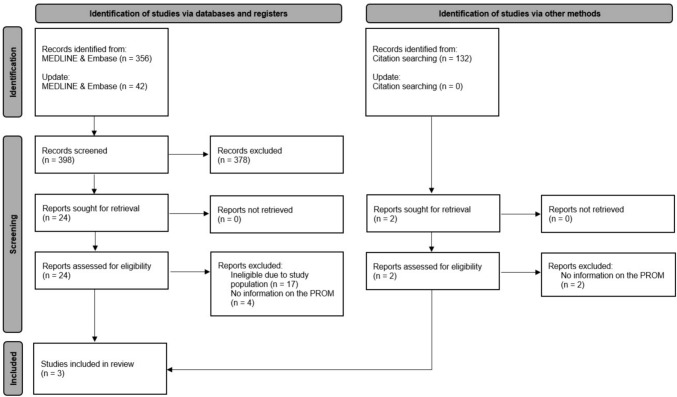

Search 1, which aimed to identify all PROMs used in the STS population, produced 4,188 records. Tracking citations from available reviews on PROs in the sarcoma population [6–8, 27–35] led to 856 records. After screening, 127 reports were identified for retrieval, resulting in 119 reports assessed for eligibility. Fifty-nine studies were included in the review (refer to Fig. 2 for the flow diagram) [13–16, 18, 36–89]. Search 2 generated 530 records. Retrieval and assessment of 26 reports for eligibility resulted in three studies being included in the review (see Fig. 3 for the flow diagram) [54, 90, 91]. Supplementary Information 3 provides a list of all articles that underwent full-text review but were subsequently excluded, along with the reasons for their exclusion.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of search 1

Fig. 3.

Flow diagram of search 2

Identification of patient-reported outcome measures

Following search 1, 59 studies were included in the review. Median year of publication 2018 [IQR 8]. Of these, 45 (76.3%) were cohort studies, 12 (20.3%) were cross-sectional studies, one (1.7%) was a (non-randomized) phase IV study and one (1.7%) was a cluster-randomized controlled trial (which presented longitudinal data without treatment randomization). Among cohort studies, 27 (45.8%) were prospective and 20 (33.9%) were retrospective. Monocenter studies accounted for 44 (74.6%) of the total, while multicenter studies compromised 14 (23.7%). The median sample size was 68 [IQR 105] patients, with a mean age of 57.0 (SD 7.0) years, and a median percentage of male patients at 52.4 [IQR 10.8] %. The overall quality varied across the studies: 12 (20.3%) were deemed poor, 39 (66.1%) were considered fair, and 8 (13.6%) were rated as good. Further details on study characteristics can be found in Supplementary Information 4 and Supplementary Information 5 provides information on risk of bias.

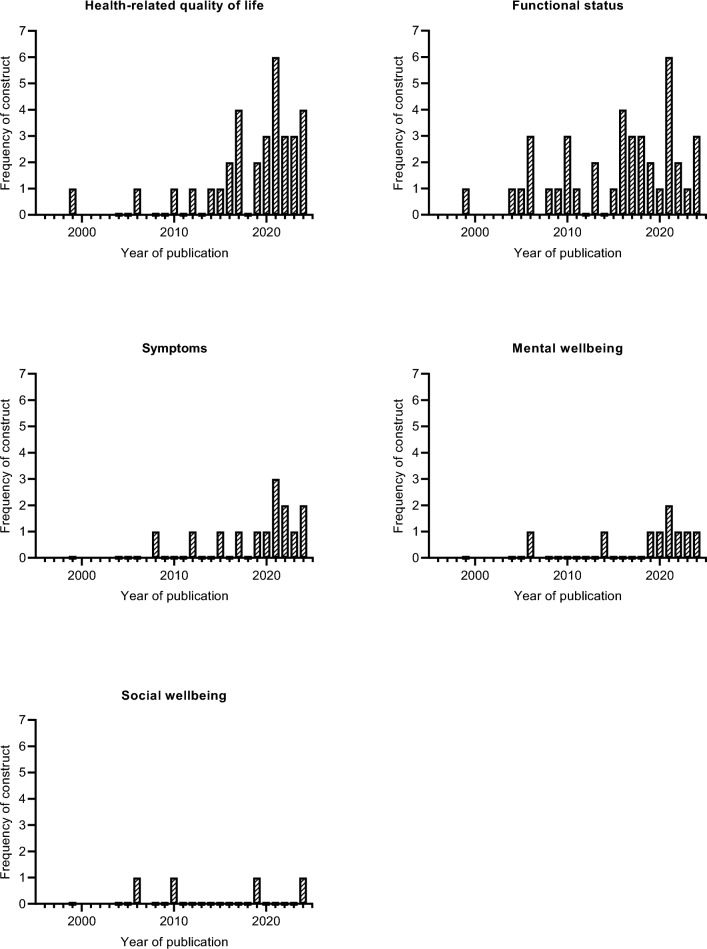

Health-related quality of life was evaluated in 33 (55.9%) studies. In 40 (67.8%) studies, functional status was evaluated. Symptoms were the focus of evaluation in 14 (23.7%) studies, mental wellbeing in 9 (15.3%), and social wellbeing in 4 (6.8%) studies. Figure 4 illustrates the frequency of constructs evaluated in the included studies per year of publication. A total of 39 PROMs were used to assess PROs within the STS population; an overview of all PROMs is available in Supplementary Information 6. Among these, the TESS was the most commonly employed, utilized in 28 (47.5%) of the studies.

Fig. 4.

The frequency of constructs evaluated in the included studies per year of publication

Characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures

Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of the PROMs employed in the STS population. Among these, 7 (17.9%) PROMs focused on assessing health-related quality of life, 7 (17.9%) on functional status, 14 (35.9%) on symptoms, 9 (23.1%) on mental wellbeing, and 2 (5.1%) on social wellbeing. Of the total, 22 (56.4%) were generic PROMs, while 17 (43.6%) were disease-specific. Cancer patients were the target population in 10 (25.6%) measures, while sarcoma patients were the focus in 2 (5.1%) measures. These were the TESS and the Three-Item Cancer-Related Symptoms Questionnaire. Likert scaling was predominantly utilized as rating scale, accounting for 37 (94.9%) of all PROMs.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures

| PROM (first reference) | Type | Construct(s) | Target population | Mode of administration | Items | Rating scale | Item score | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 [97] | Disease-specific | Health-related quality of life (functional status, symptoms, global health, quality of life, financial impact) | Patients with cancer | Self-report | 30 | Item 1–7: no/yes, item 8–28: Likert scale 4-point, item 29–30: Likert scale 7-point | 0–100 | Score per scale (0–100) |

| SF-36 [98] | Generic | Health-related quality of life (physical functioning, role limitations because of physical health problems, bodily pain, social functioning, general mental health, role limitations because of emotional problems, vitality, general health perceptions) | Persons 14 years of age and older | Self-report or interview | 36 | Item 4–5: no/yes, other items: scale with Likert scale ranging from 3-point to 7-point | 0–100 | Scores determined by algorithm (T-score based on norm: general US population) |

| SF-8 [99] | Generic | Health-related quality of life (physical functioning, role limitations because of physical health problems, bodily pain, social functioning, general mental health, role limitations because of emotional problems, vitality, general health perceptions) | Persons 14 years of age and older | Self-report | 8 | Likert scale 5-point or 6-point | 0–100 | Scores determined by algorithm (T-score based on norm: general US population) |

| EQ-5D-3L [100] | Generic | Health-related quality of life (mobility, self-care, main activity, social relationships, pain, mood) | Adults | Self-report | 5 | 3 levels and overall rating of health | Variable | Overall rate of health 0–100, score per level, summary index (based on a formula) |

| EQ-5D-5L [101] | Generic | Health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) | Adults | Self-report | 5 | 5 levels and overall rating of health | Variable | Overall rate of health 0–100, score per level, summary index (based on a formula) |

| FACT-G [102] | Disease-specific | Health-related quality of life (physical, social, emotional and functional well-being) | Patients with cancer | Self-report | 27 | Likert scale 5-point | 0–4 | Weighted score per subscale, transformed to overall score of 0–108 |

| PROMIS -Global Health [103] | Generic | Health (physical function, fatigue, pain, emotional distress, and social health) | Adults | Self-report | 10 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | One score for physical health and one score for mental health |

| Functional status | ||||||||

| TESS [11] | Disease-specific | Functional status | Adult musculoskeletal oncology | Self-report | 57 (28 UE and 29 LE) | Likert scale 5-point | Weighted | 0–100 |

| LEFS [104] | Disease-specific | Functional status | Patients with any LE musculoskeletal condition | Self-report | 20 | Likert scale 5-point | 0–4 | 0–80 |

| MHQ [105] | Disease-specific | Functional status | Patients with hand disorders | Self-report | 37 | Raw score per scale (in total 6 different scales), which is converted to a score 0–100 | Weighted | 0–100, the sum of each scale divided by 6 |

| FAOS [106] | Disease-specific | Functional status | Patients with foot and ankle problems | Self-report | 42 | Likert scale 5-point, 5 subscales | 0–4 | Raw scores of the 5 subscales transformed to 0–100 |

| SMFA [107] | Disease-specific | Functional status | Patients with musculoskeletal disease | Self-report | 46 | Two scales (34 and 12 items), Likert scale 5-point (1–5) | 1–5 | Sum of scales transformed by formula to 0–100 |

| QuickDASH [108] | Disease-specific | Functional status and symptoms | Patients with any or multiple disorders of the UE | Self-report | 11 | Likert scale 5-point | 1–5 | Sum of responses transformed by formula to 0–100 |

| PROMIS -Physical function [103] | Generic | Physical function | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 124; short form 10 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| BPI-SF [109] | Generic | Pain | Adults | Self-report | 9 | Item 1: no/yes, item 2: body diagram, item 3–6 and 8–9: Likert scale 0–10, item 7: open-ended question | 0–10 | Per subscale (pain severity and pain interference): mean of Likert scale (0–10) |

| LENT-SOMA [110] | Disease-specific | Late toxicity of radiation therapy | Patients with cancer | Self-report or interview | 37 | Likert scale 4-point | 1–4 | None, all criteria are described separately |

| ISI [111] | Generic | Insomnia | Adults with insomnia complaints | Self-report | 7 | Likert scale 5-point | 0–4 | Summary of scores per item |

| MFI-20 [112] | Generic | Fatigue (general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation, mental fatigue) | Adults | Self-report | 20 | Likert scale 5-point | 1–5 | Score per scale (4–20) |

| NRS [113] | Generic | Pain | Adults | Self-report | 1 | Likert scale 11-point | 0–10 | 0–10 |

| MIDOS [114] | Disease-specific | Symptoms (pain, drowsiness, nausea, constipation, dyspnea, lymphedema, weakness, anxiety, well-being) | Palliative patients | Self-report | 16 | Likert scale 4-point | 0–3 | Summary of scores per item (0–48) |

| MDASI [115] | Disease-specific | Symptoms (severity and interference) | Patients with cancer | Self-report or interview | 19 | Likert scale 11-point | 0–10 | Per subscale (mean or summary of scores) |

| MSAS-SF [116] | Disease-specific | Symptoms (global distress, physical symptom distress, psychological symptom distress) | Patients with cancer | Self-report | 32 | Likert scale 5-point | 0–4 | Per subscale (mean: 0–4) |

| Three-item Cancer-Related Symptoms Questionnaire [17] | Disease-specific | Pain, cough, shortness of breath | Metastatic sarcomas | Self-report | 3 | Mild-moderate-severe (%) | None (%) | None |

| PROMIS—Pain Interference [103] | Generic | Pain | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 41; short form 6 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

| PROMIS—Fatigue [103] | Generic | Fatigue | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 95; short form 7 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

| PROMIS—Sleep disturbance [103] | Generic | Sleep | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 27; short form 8 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

| FACIT-F [117] | Disease-specific | Fatigue | Patients with chronic (oncologic) illnesses | Self-report | 13 | Likert scale 5-point | 0–4 | Individual item score multiplied by 13, divided by number of items answered |

| PRO-CTCAE [118] | Disease-specific | Symptoms | Patients on cancer clinical trials | Self-report | 124 | Likert scale 5-point | 0–4 | None, score per attribute |

| Mental wellbeing | ||||||||

| HADS [119] | Generic | Anxiety, depression | Patients in a non-psychiatric hospital department | Self-report | 14 | Likert scale 4-point | 0–3 | Per subscale (anxiety/depression): summary of scores |

| CWS [120] | Disease-specific | Cancer worries | Patients with cancer | Self-report | 8 | Likert scale 4-point | 1–4 | 8–32 |

| IES [121] | Generic | Stress | Adults | Self-report | 15 (7 intrusion and 8 avoidance items) | 0 (not at all)—1 (rarely)—3 (sometimes)—5 (often) | 0–1-3–5 | Per subscale (intrusion: 0–35 and avoidance: 0–40), summary of scores (0–75) |

| NCCN Distress Thermometer [122] | Disease-specific | Distress | Patients with cancer | Self-report | 1 | Likert scale 11-point | 0–10 | 0–10 |

| WHO-5 [123] | Generic | Mental wellbeing | Children aged 9 and above | Self-report | 5 | Likert scale 6-point | 0–5 | 0–25 |

| PROMIS—Depression [103] | Generic | Depression | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 28; short form 8 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

| PROMIS—Anxiety [103] | Generic | Anxiety | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 29; short form 7 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

| WEMWBS [124] | Generic | Mental wellbeing | Adults | Self-report | 14; short form 7 | Likert scale 5-point | 1–5 | Summing the scores of each of the items |

| FoP-Q-SFa | Disease-specific | Fear of progression | Patients with cancer | Self-report | 12 | Likert scale 5-point | 1–5 | 12–60 |

| Social wellbeing | ||||||||

| RNL [125] | Generic | Participation (mobility, self-care, daily activity, recreational activity, family roles) | Adults after incapacitating illness or severe trauma | Self-report | 11 | Likert scale 10-point | 1–10 | Summary of scores (maximum 110), proportionally converted to a 100-point scale |

| PROMIS—Ability to participate [103] | Generic | Social function | Adults | Self-report | Item bank 14; short form 7 | Likert scale 5-point | Variable | T-score (score of 50 equals the mean of the US population) |

US United States of America, UE upper extremity, LE lower extremity, PROM patient-reported outcome measure

aFull-text of development study not available

Methodological assessment of patient-reported outcome measures

After search 2, three studies were found that report on measurement properties of three PROMs in the STS population; the TESS, Quick Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH) and European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30). Table 3 provides an overview of the characteristics of the included study populations. The sample sizes ranged from 14 to 136 patients, with ages spanning from 52 to 65 years old. Two of the studies included patients with localized STS disease, while one focused on advanced STS patients. All assessments were done in clinical settings. Language-wise, two studies were in Finnish and one in English. Response rates varied from 70 to 85%. In Table 4, we present the results of the measurement properties assessed against criteria for good measurement properties.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the included study populations

| PROM | References | Population | Disease | Instrument administration | Measurement properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Agea | Genderb | Stage | Treatment | Setting | Country (language) | Response rate (%) | |||

| TESS | Kask et al. [90] | 136 | 65.6 (14.4) | 66 (48.5) | Local STS (lower extremity) | Surgery | Clinical | Finland (Finnish) | 70 | Structural validity, internal consistency, measurement invariance, reliability and hypotheses testing for construct validity |

| Ketola et al. [91] | 55 | 62.8 (14.6) | 27 (49.1) | Local STS (upper extremity) | Limb-sparing surgery | Clinical | Finland (Finnish) | 85 | Internal consistency, measurement invariance and hypotheses testing for construct validity | |

| QuickDASH | Ketola et al. [91] | 55 | 62.8 (14.6) | 27 (49.1) | Local STS (upper extremity) | Limb-sparing surgery | Clinical | Finland (Finnish) | 85 | Internal consistency, measurement invariance and hypotheses testing for construct validity |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | Gough et al. [54] | 27; 14c | 52.2 (14) | 21 (32) | Locally advanced, inoperable or metastatic STS | Palliative chemotherapy or under surveillance after first-line palliative chemotherapy having responded favorably | Clinical | United Kingdom (English) | 84 | Content validity (the relevance of the PROM items) |

PROM patient-reported outcome measure, STS soft-tissue sarcoma

aMean (SD) or median [IQR]

bMale patients (%)

cTwenty-seven patients were included for quantitative analysis; 14 patients for qualitative analysis

Table 4.

Results of studies on measurement properties

| PROM | Structural validity | Internal consistency | Measurement invariance | Reliability | Hypotheses testing for construct validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | MQ | Result (rating) | MQ | Result (rating) | MQ | Result (rating) | MQ | Result (rating) | MQ | Result (rating) | |

| TESS [90] | 136 | Inadequate | EFA: factor 1 explaining 74.4% of the variance; factor 2 6.4%; factor 3 4.2% and factor 4 3.3% (?) | Very good | Cronbach’s alpha 0.97 (95% CI = 0.97–0.98) (?/+) | Inadequate | Significant correlation of TESS with age (rho = − 0.23 and p = 0.006) and BMI (rho = − 0.25 and p = 0.006). No difference in gender (t test, p = 0.143) (−) | Doubtful | ICC 0.95 (95% CI = 0.93–0.96 and p < 0.001) (+) | Inadequate |

Results in line with 8 hypotheses Results not in line with 2 hypotheses (+) |

| TESS [91] | 55 | Very good | Cronbach’s alpha 0.97 (?/+) | Inadequate | No difference in BMI and age, Spearman’s correlation − 0.17 for age and − 0.09 for BMI. Sex insignificant (t test, p = 0.53). (+) | Inadequate |

Results in line with 8 hypotheses Results not in line with 2 hypotheses (+) |

||||

| QuickDASH [91] | 55 | Inadequate | Cronbach’s alpha 0.930 (?/+) | Inadequate | No difference in BMI and age, Spearman’s correlation 0.03 for age and 0.01 for BMI. Gender insignificant (t test, p = 0.92). (+) | Inadequate |

Results in line with 8 hypotheses Results not in line with 2 hypotheses (+) |

||||

PROM patient-reported outcome measure, MQ methodological quality, EFA exploratory factor analysis, BMI body mass index, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient

Content validity

The TESS was the sole PROM in the review developed for STS patients, yet it was rated inadequate according to the COSMIN guidelines. The development study of the Three-item Cancer-Related Symptoms Questionnaire, which potentially involved STS patients, was unavailable. One study was performed to evaluate content validity of a PROM in the STS population. The relevance of the PROM items of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 were evaluated by asking patients what constitutes health-related quality of life. The overall rating of the quality of the content validity study was inadequate. From the qualitative interviews, eight factors were described as relevant for a good health-related quality of life in advanced STS patients. These factors were being free from pain/symptoms, time with family and friends, help with anxiety, loss of independence/control over life, enjoyment of job, outdoor activities, holidays and financial stability. Of these eight factors, three were not mentioned in the EORTC-QLQ-C30. These factors are loss of independence/control over life, enjoyment of job and holidays.

Internal structure

In evaluating the TESS, structural validity was examined in 136 patients, with internal consistency and measurement invariance studied in 191 patients. The analysis of structural validity revealed a high risk of bias. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted with one factor explaining 74.4% of the variance of all items. Internal consistency showed low risk of bias, with Cronbach’s alpha 0.97 (95% CI 0.97–0.98). Results for measurement invariance were inconsistent, possibly due to variations in study populations. Risk of bias for the assessment of measurement invariance was high and one study reports a significant correlation of TESS with age (rho = − 0.23, p = 0.006) and BMI (rho = − 0.25, p = 0.006). As for the QuickDASH, internal consistency and measurement invariance were assessed in 55 patients, with a high risk of bias. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.930 (no CI reported) and there were no significant correlations (with BMI, age, gender).

Other measurement properties

Reliability of the TESS was evaluated in 136 patients and construct validity in 191 patients. Risk of bias for reliability was moderate, with an ICC of 0.95 (95% CI 0.93–0.96, p < 0.001). Risk of bias for the assessment of construct validity was high and results were in accordance with hypotheses. For the QuickDASH construct validity was assessed in 55 patients, with high risk of bias. The results were in line with hypotheses.

Interpretability and feasibility

There was no floor effect for the TESS and QuickDASH. However, a ceiling effect was observed for both, with 27% of study participants achieving the maximum score on the TESS and 20% on the QuickDASH.

Recommendation

Due to the limited availability of evidence, a high risk of bias, and inconsistencies in findings, we were unable to pool or summarize the results. None of the PROMs utilized in the STS population can be recommended for use based on the current evidence and corresponding COSMIN analyses.

Discussion

This systematic review presents an overview of all PROMs utilized in the STS population and a methodological evaluation of these PROMs. Functional status continues to be the predominantly researched construct, highlighting gaps in knowledge related to mental and social wellbeing. Thirty-nine different PROMs were identified, with the TESS, EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EQ-5D-3L being the most frequently utilized in the STS population. Given the scarcity of evidence, high risk of bias, and inconsistencies in results, it is not feasible to recommend any of the PROMs for use in the STS population at this time. Notably, there persists an inadequacy of knowledge on content validity of PROMs utilized in the STS population, the most important measurement property. The development of only one PROM, the TESS, involved STS patients and one content validity study has been conducted. Both were of inadequate quality; the content validity study additionally revealed insufficient content validity of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in the STS population.

Research conducted with PROMs of questionable or undetermined quality is prevalent [92], which is consistent with the review’s findings. This could be attributed to the fact that more than half of the employed PROMs were generic. Generic PROMs, such as the EQ-5D, have proven to result in sufficient measurement properties in wide variations of populations [90, 93], so validation in specific populations is sometimes argued to be unnecessary. Measurement properties of generic PROMs can however vary, for instance the measurement properties of the EQ-5D in patients with mental health disorders were found to be doubtful [93, 94]. Hence, validation of generic PROMs in specific populations is recommended before use, which is in line with the COSMIN methodology [21].

Pressure on health care systems to improve quality and control costs has resulted in the development of value-based care [95]. In a value-based health care system, efficiency is analyzed by calculating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The QALY is a measure of survival weighted by a coefficient that expresses a state of health (utility value) in comparison with perfect health [91]. PROMs, such as the EQ-5D, are used in value-based care to determine the patients’ health state and corresponding utility value. The utility value is therefore directly related to the ability of the PROM to measure outcome of a health state in a specific patient population. Assessing PROM quality is ethically important, as patient invest time and effort in providing information about their health status. Also, the relevance of evaluating PROMs lies in producing credible and generalizable data to ensure evidence-based medicine, and promotes individualized and value-based healthcare.

Recent reviews have emphasized the importance of developing a specific instrument to capture the patient experience of STS diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [28, 30–32]. The rationale for developing a new instrument is to analyze the specific experience of diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of STSs, as its rarity is expected to result in a different experience than tumors of more frequent occurrence. The TESS, a sarcoma-specific PROM, has been the PROM used most frequently in the STS population [11]. Based on our analysis, there is limited supporting evidence for the TESS effectively assessing functional status. Since the development of the TESS, improved treatment options have resulted in decreased morbidity. The qualitative study of Martins et al. [96] including STS patients at various stages from diagnosis indicates that 68% of issues affecting STS patients were related to mental wellbeing, such as anxiety, depression and distress. In that study, it is stated that their top-rated items on functional status do not reflect those included in existing measures. The construct and items evaluated by the TESS may therefore not be that relevant in the current time. These findings, along with the prospective outlook on value-based health care, stress the importance of systematically analyzing measurement properties of existing PROMs, as well as performing qualitative research in specific patient populations to determine relevant content.

Considerable effort has been put into identifying all PROMs utilized in the STS population. This involved thorough searches of two large biomedical databases without time limits, as well as citation tracking. Some PROMs that could be applicable for use in STS patients may not have been included because they have not been utilized to measure outcomes in the STS population. Additionally, the search was limited to two biomedical databases and may have missed articles in other fields. No grey literature review was undertaken. The current review is the first to explore methodological quality of PROMs in the STS population using the COSMIN guidelines. Owing to the paucity of available evidence, we could not offer summarized or pooled results. Nevertheless, this review marks an initial move towards elevating the standard of research with PROMs in the STS population. Consolidating the findings of the searches pertaining to our two objectives within a unified review facilitates access to information on previous employed PROMs and our recommendations from existent evidence.

To identify PROMs, we opted to exclude trials that randomize treatment. While this may be viewed as a limitation of our review, it serves to mitigate bias in our findings. By focusing solely on PROMs which share a common intended purpose, we ensure greater consistency and reliability in our analysis. The review is limited by the absence of protocol registration prior to commencement, a step that was overlooked due to the lack of anticipation for duplication. However, our eligibility criteria, design, and objectives remained consistent throughout the process. The assessment of content validity was tailored to fit the target population of the current review and the limited available literature in the context. According to the COSMIN guidelines, it is recommended to assess all PROM development studies based on their target population. We focused solely on evaluating PROMs developed involving STS patients, as this aligns with the specific target population of our review. In addition, reviewers are recommended to rate the content validity of the PROMs, considering evidence from PROM development studies and content validity studies within the specific target population. The scarcity of knowledge on the content of (aspects of) health-related quality of life in STS patients and the absence of both PROM development and content validity studies posed limitations. These limitations prevented reviewers from carrying out the assessment, as it would lack an evidence-based foundation.

The utilization of PROMs has seen a rise in the last twenty-five years, leading to a substantial increase in the number of available PROMs. This review marks the first systematic exploration of evidence regarding the measurement properties of PROMs used in the STS population. Given the restricted available evidence on the quality of PROMs employed in the STS population and considering future perspectives, now is an opportune time to change the narrative. This involves exploring relevant content specific to the STS population and subsequently choosing the most appropriate PROM to measure it. While existing PROMs may have potential suitability for application in the STS population, it is imperative to investigate their methodological quality to ensure the validity and reliability of outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by Marnix R. Jansen, Goudje L. van Leeuwen and Jasmijn D. Generaal. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jasmijn D. Generaal and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Data availability

All data are publicly available and can be found either within the tables of the review or in the Supplementary Information.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no funds, grants or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gronchi, A., Miah, A. B., Dei Tos, A. P., Abecassis, N., Bajpai, J., Bauer, S., Biagini, R., Bielack, S., Blay, J. Y., Bolle, S., Bonvalot, S., Boukovinas, I., Bovee, J. V. M. G., Boye, K., Brennan, B., Brodowicz, T., Buonadonna, A., De Álava, E., Del Muro, X. G., … Stacchiotti, S. (2021). Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO–EURACAN–GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 32(11), 1348–1365. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dutch Cancer Registration. (2021). Incidence of sarcomas. https://iknl.nl/kankersoorten/bot-en-wekedelenkanker/registratie/incidentie

- 3.Casali, P. G., Abecassis, N., Bauer, S., Biagini, R., Bielack, S., Bonvalot, S., Boukovinas, I., Bovee, J. V. M. G., Brodowicz, T., Broto, J. M., Buonadonna, A., De Álava, E., Dei Tos, A. P., Del Muro, X. G., Dileo, P., Eriksson, M., Fedenko, A., Ferraresi, V., Ferrari, A., … Blay, J. Y. (2018). Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 29(October), iv68–iv78. 10.1093/annonc/mdy095 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hoekstra, H. J., Haas, R. L. M., Verhoef, C., Suurmeijer, A. J. H., van Rijswijk, C. S. P., Bongers, B. G. H., van der Graaf, W. T., & Ho, V. K. Y. (2017). Adherence to Guidelines for Adult (Non-GIST) soft tissue sarcoma in the Netherlands: A plea for dedicated sarcoma centers. Annals of Surgical Oncology,24(11), 3279–3288. 10.1245/s10434-017-6003-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson, M. G., Ubbels, J. F., Slump, J., Huijing, M. A., Bastiaannet, E., Pras, E., Hoekstra, H. J., & Been, L. B. (2018). Identification of predictors for wound complications following preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. European Journal of Surgical Oncology,44(6), 816–822. 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng Kee Kwong, T., Furtado, S., & Gerrand, C. (2014). What do we know about survivorship after treatment for extremity sarcoma? A systematic review. European Journal of Surgical Oncology,40(9), 1109–1124. 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonough, J., Eliott, J., Neuhaus, S., Reid, J., & Butow, P. (2019). Health-related quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and unmet health needs in patients with sarcoma: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology,28(4), 653–664. 10.1002/pon.5007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kask, G., Barner-Rasmussen, I., Repo, J. P., Kjäldman, M., Kilk, K., Blomqvist, C., & Tukiainen, E. J. (2019). Functional outcome measurement in patients with lower-extremity soft tissue sarcoma: A systematic literature review. Annals of Surgical Oncology,26(13), 4707–4722. 10.1245/s10434-019-07698-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Sullivan, B., Davis, A. M., Turcotte, R., Bell, R., Catton, C., Chabot, P., Wunder, J., Kandel, R., Goddard, K., Sadura, A., Pater, J., & Zee, B. (2002). Preoperative versus postoperative radiotherapy in soft-tissue sarcoma of the limbs: A randomised trial. The Lancet,359(9325), 2235–2241. 10.1007/978-1-4471-5451-8_126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (2006). Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims: Draft guidance. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 1–20. 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Davis, A. M., Wright, J. G., Williams, J. I., Bombardier, C., Griffin, A., & Bell, R. S. (1996). Development of a measure of physical function for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Quality of Life Research,5(5), 508–516. 10.1007/BF00540024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson, I. B., & Cleary, P. D. (1995). Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. JAMA,273(1), 59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer, S., Soimaru, S., Hirsch, T., Kueckelhaus, M., Seitz, C., Lehnhardt, M., Goertz, O., Steinau, H. U., & Daigeler, A. (2015). Local tendon transfer for knee extensor mechanism reconstruction after soft tissue sarcoma resection. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery,68(5), 729–735. 10.1016/j.bjps.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komatsu, S., Okamoto, M., Shiba, S., Kaminuma, T., Okazaki, S., Kiyohara, H., Yanagawa, T., Nakano, T., & Ohno, T. (2021). Prospective evaluation of quality of life and functional outcomes after carbon ion radiotherapy for inoperable bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Cancers. 10.3390/cancers13112591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber, D., Bell, R. S., Wunder, J. S., O’Sullivan, B., Turcotte, R., Masri, B. A., & Davis, A. M. (2006). Evaluating function and health related quality of life in patients treated for extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Quality of Life Research,15(9), 1439–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoven-Gondrie, M. L., Thijssens, K. M. J., Geertzen, J. H. B., Pras, E., Van Ginkel, R. J., & Hoekstra, H. J. (2008). Isolated limb perfusion and external beam radiotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity: Long-term effects on normal tissue according to the LENT-SOMA scoring system. Annals of Surgical Oncology,15(5), 1502–1510. 10.1245/s10434-008-9850-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chawla, S. P., Blay, J., Ray-Coquard, I. L., Le Cesne, A., Staddon, A. P., Milhem, M. M., Penel, N., Riedel, R. F., Nguyen, B. B., Cranmer, L. D., Reichardt, P., Bompas, E., Song, Y., Lee, R., Eid, J. E., Loewy, J., Haluska, F. G., & Dodion, G. D. (2011). Results of the phase III, placebo-controlled trial (SUCCEED) evaluating the mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus (R) as maintenance therapy in advanced sarcoma patients (pts) following clinical benefit from prior standard cytotoxic chemotherapy (CT). Journal of Clinical Oncology,29(15), 10005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaver, C., Isaacson, A., Gregory, J. J., Cribb, G., & Cool, P. (2016). Patient factors affecting the Toronto extremity salvage score following limb salvage surgery for bone and soft tissue tumors. Journal of Surgical Oncology,113(7), 804–810. 10.1002/jso.24247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teisberg, E., Wallace, S., & O’Hara, S. (2020). Defining and implementing value-based health care: A strategic framework. Academic Medicine,95(5), 682–685. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., Mcdonald, S., … Mckenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Mokkink, L. B., de Vet, H. C. W., Prinsen, C. A., & Terwee, C. B. (2023). COSMIN methodology for conducting systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 1–3). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_2972-2

- 22.Terwee, C. B., Prinsen, C. A. C., Chiarotto, A., De Vet, H. C. W., Westerman, M. J., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Prinsen, C. A. C., Chiarotto, A., De Vet, H. C. W., Westerman, M. J., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., … Mokkink, L. B. (2017). COSMIN standards and criteria for evaluating the content validity of health-related Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Delphi study. Quality of Life Research,27, 1159–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss, S. J., Frezza, A. M., Abecassis, N., Bajpai, J., Bauer, S., Biagini, R., Bielack, S., Blay, J. Y., Bolle, S., Bonvalot, S., Boukovinas, I., Bovee, J. V. M. G., Boye, K., Brennan, B., Brodowicz, T., Buonadonna, A., de Álava, E., Dei Tos, A. P., Garcia del Muro, X., … Stacchiotti, S. (2021). Bone sarcomas: ESMO–EURACAN–GENTURIS–ERN PaedCan Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 32(12), 1520–1536. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1995 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Terwee, C. B., Jansma, E. P., Riphagen, I. I., & De Vet, H. C. W. (2009). Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Quality of Life Research,18(8), 1115–1123. 10.1007/s11136-009-9528-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma, L.-L., Wang, Y.-Y., Yang, Z.-H., Huang, D., Weng, H., & Zeng, X.-T. (2002). Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary. Military Medical Research,7(7), 1–11. 10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institutes of Health. (2019). NIH quality assessment tool for observational Cohort and cross-sectional studies (pp. 1–4). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 27.Tang, M. H., Pan, D. J. W., Castle, D. J., & Choong, P. F. M. (2012). A systematic review of the recent quality of life studies in adult extremity sarcoma survivors. Sarcoma. 10.1155/2012/171342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winnette, R., Hess, L. M., Nicol, S. J., Tai, D. F., & Copley-Merriman, C. (2017). The patient experience with soft tissue sarcoma: A systematic review of the literature. Patient,10(2), 153–162. 10.1007/s40271-016-0200-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storey, L., Fern, L. A., Martins, A., Wells, M., Bennister, L., Gerrand, C., Onasanya, M., Whelan, J. S., Windsor, R., Woodford, J., & Taylor, R. M. (2019). A critical review of the impact of sarcoma on psychosocial wellbeing. Sarcoma. 10.1155/2019/9730867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.den Hollander D, van der Graaf WTA, F. M., Den Hollander, D., Van Der Graaf, W. T. A., Fiore, M., Kasper, B., Singer, S., Desar, I. M. E., & Husson, O. (2020). Unravelling the heterogeneity of soft tissue and bone sarcoma patients’ health-related quality of life: a systematic literature review with focus on tumor location. ESMO Open. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Almeida, A., Martins, T., & Lima, L. (2021). Patient-reported outcomes in sarcoma: A scoping review. European Journal of Oncology Nursing,50, 101897–98. 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blight, T. J., & Choong, P. F. M. (2021). The need for improved patient reported outcome measures in patients with extremity sarcoma: A narrative review. ANZ Journal of Surgery,91(10), 2021–2025. 10.1111/ans.17028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiffen, J., & Mah, E. (2023). Determining functional outcomes after resection and reconstruction of primary soft tissue sarcoma in the lower extremity: a review of current subjective and objective measurement systems. Journal of Surgical Oncology,127(5), 862–870. 10.1002/jso.27202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roets, E., van der Graaf, W., van Riet, B. H. G., Haas, R. L., Younger, E., Sparano, F., Wilson, R., van der Mierden, S., Steeghs, N., Efficace, F., & Husson, O. (2024). Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials of systemic therapy for advanced soft tissue sarcomas in adults: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology,197(January), 104345. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassani, M., Mate, K. K. V., Turcotte, R., Denis-Larocque, G., Ghodsi, E., Tsimicalis, A., & Goulding, K. (2023). Uncovering the gaps: A systematic mixed studies review of quality of life measures in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology,128(3), 430–437. 10.1002/jso.27390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed, S. K., Kaggal, S., Harmsen, W. S., Sawyer, J. W., Houdek, M. T., Rose, P. S., & Petersen, I. A. (2021). Patient-reported functional outcomes in a cohort of hand and foot sarcoma survivors treated with limb sparing surgery and radiation therapy. Journal of Surgical Oncology,123(1), 110–116. 10.1002/jso.26258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen, N. J., Mate, K. K. B., Bergeron, C., Turcotte, R., & Körner, A. (2024). Evaluating health perceptions of soft-tissue sarcoma patients using the Wilson-Cleary Model to identify key targets for improving outcomes and quality of care. Surgical Oncology,52, 1–7. 10.1016/j.suronc.2023.102028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baysal, Ö., Toprak, C. Ş, Günar, B., & Erol, B. (2021). Soft tissue sarcoma of the upper extremity: Oncological and functional results after surgery. Journal of Hand Surgery: European,46(6), 659–664. 10.1177/1753193421998252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandes, F., Striefler, J. K., Dörr, A., Schmiester, M., Märdian, S., Koulaxouzidis, G., Kaul, D., Behzadi, A., Thuss-Patience, P., Ahn, J., Pelzer, U., Bullinger, L., & Flörcken, A. (2021). Impact of a specialised palliative care intervention in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma—a single-centre retrospective analysis. BMC Palliative Care,20(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12904-020-00702-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Callegaro, D., Miceli, R., Brunelli, C., Colombo, C., Sanfilippo, R., Radaelli, S., Casali, P. G., Caraceni, A., Gronchi, A., & Fiore, M. (2015). Long-term morbidity after multivisceral resection for retroperitoneal sarcoma. British Journal of Surgery,102(9), 1079–1087. 10.1002/bjs.9829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cassidy, R. J., Indelicato, D. J., Gibbs, C. P., Scarborough, M. T., Morris, C. G., & Zlotecki, R. A. (2016). Function preservation after conservative resection and radiotherapy for soft-tissue sarcoma of the distal extremity: Utility and application of the Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS). American Journal of Clinical Oncology: Cancer Clinical Trials,39(6), 600–603. 10.1097/COC.0000000000000107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cribb, G. L., Loo, S. C. S., & Dickinson, I. (2010). Limb salvage for soft-tissue sarcomas of the foot and ankle. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series B,92(3), 424–429. 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.22331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalton, J. F., Furdock, R., Cluts, L., Jilakara, B., Mcdonald, D., Calfee, R., & Cipriano, C. (2022). Pre- and post-operative patient-reported outcome measurement information system scores in patients treated for benign versus malignant soft tissue tumors. Cureus. 10.7759/cureus.25534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidge, K. M., Wunder, J., Tomlinson, G., Wong, R., Lipa, J., & Davis, A. M. (2010). Function and health status outcomes following soft tissue reconstruction for limb preservation in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology,17(4), 1052–1062. 10.1245/s10434-010-0915-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davidson, D., Barr, R. D., Riad, S., Griffin, A. M., Chung, P. W., Catton, C. N., O’Sullivan, B., Ferguson, P. C., Davis, A. M., & Wunder, J. S. (2016). Health-related quality of life following treatment for extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology,114(7), 821–827. 10.1002/jso.24424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis, A. M., Sennik, S., Griffin, A. M., Wunder, J. S., O’Sullivan, B., Catton, C. N., & Bell, R. S. (2000). Predictors of functional outcomes following limb salvage surgery for lower-extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology,73(4), 206–211. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(200004)73:4%3c206::AID-JSO4%3e3.0.CO;2-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drabbe, C., Van der Graaf, W. T. A., De Rooij, B. H., Grünhagen, D. J., Soomers, V. L. M. N., Van de Sande, M. A. J., Been, L. B., Keymeulen, K. B. M. I., van der Geest, I. C. M., Van Houdt, W. J., & Husson, O. (2021). The age-related impact of surviving sarcoma on health-related quality of life: Data from the SURVSARC study. ESMO Open,6(1), 100047. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eichler, M., Hentschel, L., Richter, S., Hohenberger, P., Kasper, B., Andreou, D., Pink, D., Jakob, J., Singer, S., Grützmann, R., Fung, S., Wardelmann, E., Arndt, K., Heidt, V., Hofbauer, C., Fried, M., Gaidzik, V. I., Verpoort, K., Ahrens, M., … Schuler, M. K. (2020). The health-related quality of life of sarcoma patients and survivors in germany—cross-sectional results of a nationwide observational study (Prosa). Cancers, 12(12), 1–19. 10.3390/cancers12123590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Fiore, M., Brunelli, C., Miceli, R., Manara, M., Lenna, S., Rampello, N. N., Callegaro, D., Colombo, C., Radaelli, S., Pasquali, S., Caraceni, A. T., & Gronchi, A. (2020). A prospective observational study of multivisceral resection for retroperitoneal sarcoma: Clinical and patient-reported outcomes 1 year after surgery. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 10.1245/s10434-020-09307-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerrand, C. H., Wunder, J. S., Kandel, R. A., O’Sullivan, B., Catton, C. N., Bell, R. S., Griffin, A. M., & Davis, A. M. (2004). The influence of anatomic location on functional outcome in lower-extremity soft-tissue sarcoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology,11(5), 476–482. 10.1245/ASO.2004.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghert, M. A., Davis, A. M., Griffin, A. M., Alyami, A. H., White, L., Kandel, R. A., Ferguson, P., O’Sullivan, B., Catton, C. N., Lindsay, T., Rubin, B., Bell, R. S., & Wunder, J. S. (2005). The surgical and functional outcome of limb-salvage surgery with vascular reconstruction for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity. Annals of Surgical Oncology,12(12), 1102–1110. 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Götzl, R., Sterzinger, S., Semrau, S., Vassos, N., Hohenberger, W., Grützmann, R., Agaimy, A., Arkudas, A., Horch, R. E., & Beier, J. P. (2019). Patient’s quality of life after surgery and radiotherapy for extremity soft tissue sarcoma-a retrospective single-center study over ten years. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes,17(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12955-019-1236-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gough, N., Koffman, J., Ross, J. R., Riley, J., & Judson, I. (2017). Symptom burden in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management,53(3), 588–597. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gough, N., Koffman, J., Ross, J. R., Riley, J., & Judson, I. (2019). Does palliative chemotherapy really palliate and are we measuring it correctly? A mixed methods longitudinal study of health related quality of life in advanced soft tissue sarcoma. PLoS ONE,14(9), 1–24. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Homsy, P., Kantonen, I., Salo, J., Albäck, A., & Tukiainen, E. (2022). Reconstruction of the superficial femoral vessels with muscle flap coverage for soft tissue sarcomas of the proximal thigh. Microsurgery,42(6), 568–576. 10.1002/micr.30932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jakob, J., Hentschel, L., Richter, S., Kreisel, I., Hohenberger, P., Kasper, B., Andreou, D., Pink, D., Schmitt, J., Schuler, M. K., & Eichler, M. (2022). Transferability of health-related quality of life data of large observational studies to clinical practice: Comparing retroperitoneal sarcoma patients from the PROSa study to a TARPS-WG cohort. Oncology Research and Treatment,45(11), 660–669. 10.1159/000525288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones, K. B., Ferguson, P. C., Deheshi, B., Riad, S., Griffin, A., Bell, R. S., & Wunder, J. S. (2010). Complete femoral nerve resection with soft tissue sarcoma: Functional outcomes. Annals of Surgical Oncology,17, 401–406. 10.1245/s10434-009-0745-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kapoor, T., Banuelos, J., Adabi, K., Moran, S. L., & Manrique, O. J. (2018). Analysis of clinical outcomes of upper and lower extremity reconstructions in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology,118(4), 614–620. 10.1002/jso.25201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kasper, B., Pink, D., Rothermundt, C., Richter, S., Augustin, M., Kollar, A., Kunitz, A., Eisterer, W., Gaidzik, V., Brodowicz, T., Egerer, G., Reichardt, P., Hohenberger, P., & Schuler, M. K. (2024). Geriatric assessment of older patients receiving trabectedin in first-line treatment for advanced soft tissue sarcomas: The E-TRAB study from The German Interdisciplinary Sarcoma Group (GISG-13). Cancers. 10.3390/cancers16030558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kemp, M. A., Hinsley, D. E., Gwilym, S. E., Giele, H. P., Athanasou, N. A., & Gibbons, C. L. (2011). Functional and oncological outcome following marginal excision of well-differentiated forearm liposarcoma with nerve involvement. Journal of Hand Surgery,36(1), 94–100. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kokkali, S., Boukovinas, I., Samantas, E., Papakotoulas, P., Athanasiadis, I., Andreadis, C., Makrantonakis, P., Samelis, G., Timotheadou, E., Vassilopoulos, G., Papadimitriou, C., Tzanninis, D., Ardavanis, A., Kotsantis, I., Karvounis-Marolachakis, K., Theodoropoulou, T., & Psyrri, A. (2022). A multicenter, prospective, observational study to assess the clinical activity and impact on symptom burden and patients’ quality of life in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas treated with trabectedin in a real-world setting in Greece. Cancers.10.3390/cancers14081879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kruiswijk, A. A., van de Sande, M. A. J., Verhoef, C., Schrage, Y. M., Haas, R. L., Bemelmans, M. H. A., van Ginkel, R. J., Bonenkamp, J. J., Witkamp, A. J., van den Akker-van Marle, M. E., Marang-van de Mheen, P. J., & van Bodegom-Vos, L. (2024). Changes in health-related quality of life following surgery in patients with high-grade extremity soft-tissue sarcoma: A prospective longitudinal study. Cancers. 10.3390/cancers16030547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lim, H. J., Ong, C. A. J., Skanthakumar, T., Mak, L. Y. H., Wasudevan, S. D., Tan, J. W. S., Chia, C. S., Tan, G. H. C., & Teo, M. C. C. (2020). Retrospective quality of life study in patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma in an Asian population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes,18(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12955-020-01491-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Macarthur, I. R., McInnes, C. W., Dalke, K. R., Akra, M., Banerji, S., Buchel, E. W., & Hayakawa, T. J. (2019). Patient reported outcomes following lower extremity soft tissue sarcoma resection with microsurgical preservation of ambulation. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery,35(3), 168–175. 10.1055/s-0038-1668116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moon, T. M., Furdock, R., Rhea, L., Pergolotti, M., Cipriano, C., & Spraker, M. B. (2021). PROMIS scores of patients undergoing neoadjuvant and adjuvant radiation therapy for surgically excised soft tissue sarcoma. Clinical and Translational Radiation Oncology,31(August), 42–49. 10.1016/j.ctro.2021.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oh, E., Seo, S. W., & Han, K. J. (2018). A longitudinal study of functional outcomes in patients with limb salvage surgery for soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcoma. 10.1155/2018/6846275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ostacoli, L., Saini, A., Zuffranieri, M., Boglione, A., Carletto, S., De Marco, I., Lombardi, I., Picci, R. L., Berruti, A., & Comandone, A. (2014). Quality of Life, anxiety and depression in soft tissue sarcomas as compared to more common tumours: An observational study. Applied Research in Quality of Life,9(1), 123–131. 10.1007/s11482-013-9213-2 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Payne, C. E., Hofer, S. O. P., Zhong, T., Griffin, A. C., Ferguson, P. C., & Wunder, J. S. (2013). Functional outcome following upper limb soft tissue sarcoma resection with flap reconstruction. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery,66(5), 601–607. 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Podleska, L. E., Kaya, N., Farzaliyev, F., Pöttgen, C., Bauer, S., & Taeger, G. (2017). Lower limb function and quality of life after ILP for soft-tissue sarcoma. World Journal of Surgical Oncology,15(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12957-017-1150-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pradhan, A., Cheung, Y. C., Grimer, R. J., Abudu, A., Peake, D., Ferguson, P. C., Griffin, A. M., Wunder, J. S., O’Sullivan, B., Hugate, R., & Sim, F. H. (2006). Does the method of treatment affect the outcome in soft-tissue sarcomas of the adductor compartment? Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – Series B,88(11), 1480–1486. 10.1302/0301-620X.88B11.17424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reichardt, P., Leahy, M., Garcia Del Muro, X., Ferrari, S., Martin, J., Gelderblom, H., Wang, J., Krishna, A., Eriksson, J., Staddon, A., & Blay, J. Y. (2012). Quality of life and utility in patients with metastatic soft tissue and bone sarcoma: The sarcoma treatment and burden of illness in North America and Europe (SABINE) study. Sarcoma. 10.1155/2012/740279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reijers, S. J. M., Husson, O., Soomers, V. L. M. N., Been, L. B., Bonenkamp, J. J., van de Sande, M. A. J., Verhoef, C., van der Graaf, W. T. A., & van Houdt, W. J. (2022). Health-related quality of life after isolated limb perfusion compared to extended resection, or amputation for locally advanced extremity sarcoma: Is a limb salvage strategy worth the effort? European Journal of Surgical Oncology,48(3), 500–507. 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saebye, C., Amidi, A., Keller, J., Andersen, H., & Baad-Hansen, T. (2020). Changes in functional outcome and quality of life in soft tissue sarcoma patients within the first year after surgery: A prospective observational study. Cancers. 10.3390/cancers12020463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saebye, C., Fugloe, H. M., Nymark, T., Safwat, A., Petersen, M. M., Baad-Hansen, T., Krarup-Hansen, A., & Keller, J. (2017). Factors associated with reduced functional outcome and quality of life in patients having limb-sparing surgery for soft tissue sarcomas—a national multicenter study of 128 patients. Acta Oncologica,56(2), 239–244. 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1268267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singer, S., Semrau, S., Golcher, H., Fechner, K., Kallies, A., Zapata Bonilla, S., Grützmann, R., Fietkau, R., Kluba, T., Jentsch, C., Andreou, D., Bornhäuser, M., Schmitt, J., Schuler, M. K., & Eichler, M. (2023). The health-related quality of life of sarcoma patients treated with neoadjuvant versus adjuvant radiotherapy—Results of a multi-center observational study. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Slump, J., Hofer, S. O. P., Ferguson, P. C., Wunder, J. S., Griffin, A. M., Hoekstra, H. J., Bastiaannet, E., & O’Neill, A. C. (2018). Flap choice does not affect complication rates or functional outcomes following extremity soft tissue sarcoma reconstruction. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery,71(7), 989–996. 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tanaka, A., Yoshimura, Y., Aoki, K., Kito, M., Okamoto, M., Suzuki, S., Momose, T., & Kato, H. (2016). Knee extension strength and post-operative functional prediction in quadriceps resection for soft-tissue sarcoma of the thigh. Bone and Joint Research,5(6), 232–238. 10.1302/2046-3758.56.2000631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tanaka, A., Yoshimura, Y., Aoki, K., Okamoto, M., Kito, M., Suzuki, S., Takazawa, A., Ishida, T., & Kato, H. (2017). Prediction of muscle strength and postoperative function after knee flexor muscle resection for soft tissue sarcoma of the lower limbs. Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research,103(7), 1081–1085. 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tanaka, A., Okamoto, M., Kito, M., Yoshimura, Y., Aoki, K., Suzuki, S., Takazawa, A., Komatsu, Y., Ideta, H., Ishida, T., & Takahashi, J. (2023). Muscle strength and functional recovery for soft-tissue sarcoma of the thigh: A prospective study. International Journal of Clinical Oncology,28(7), 922–927. 10.1007/s10147-023-02348-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thijssens, K. M. J., Hoekstra-Weebers, J. E. H. M., Van Ginkel, R. J., & Hoekstra, H. J. (2006). Quality of life after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion for locally advanced extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology,13(6), 864–871. 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Townley, W. A., Mah, E., Neill, A. C. O., Wunder, J. S., Ferguson, P. C., Zhong, T., & Hofer, S. O. P. (2013). Reconstruction of sarcoma defects following pre-operative radiation : Free tissue transfer is safe and reliable. British Journal of Plastic Surgery,66(11), 1575–1579. 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Turcotte, R. E., Ferrone, M., Lsler, M. H., & Wong, C. (2009). Outcomes in patients with popliteal sarcomas. Canadian Journal of Surgery,52(1), 51–55. 10.1016/s0276-1092(09)79545-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Werenski, J. O., Gonzalez, M. R., Fourman, M. S., Hung, Y. P., & Lozano-Calderón, S. A. (2024). Does wound VAC temporization offer patient-reported outcomes similar to single-stage excision reconstruction after myxofibrosarcoma resection? Annals of Surgical Oncology,31(4), 2757–2765. 10.1245/s10434-023-14839-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wilke, B., Cooper, A., Scarborough, M., Gibbs, P., & Spiguel, A. (2019). A comparison of limb salvage versus amputation for nonmetastatic sarcomas using patient-reported outcomes measurement information system outcomes. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons,27(8), e381–e389. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Willis, F., Buck, L., Musa, J., Hinz, U., Mechtersheimer, G., Seidensaal, K., Fröhling, S., Büchler, M. W., & Schneider, M. (2023). Long-term quality of life after resection of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 10.1016/j.ejso.2023.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wong, P., Kassam, Z., Springer, A. N., Gladdy, R., Chung, P., Ringash, J., & Catton, C. (2017). Long-term quality of life of retroperitoneal sarcoma patients treated with pre-operative radiotherapy and surgery. Cureus. 10.7759/cureus.1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wright, E. H. C., Gwilym, S., Gibbons, C. L. M. H., Critchley, P., & Giele, H. P. (2008). Functional and oncological outcomes after limb-salvage surgery for primary sarcomas of the upper limb. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery,61(4), 382–387. 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.01.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Younger, E., Jones, R. L., den Hollander, D., Soomers, V. L. M. N., Desar, I. M. E., Benson, C., Young, R. J., Oosten, A. W., de Haan, J. J., Miah, A., Zaidi, S., Gelderblom, H., Steeghs, N., Husson, O., & van der Graaf, W. T. A. (2021). Priorities and preferences of advanced soft tissue sarcoma patients starting palliative chemotherapy: Baseline results from the HOLISTIC study. ESMO Open,6(5), 100258. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhuang, A., Fang, Y., Ma, L., Yang, H., Lu, W., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., & Tong, H. (2022). Does aggressive surgery mean worse quality of life and functional capacity in retroperitoneal sarcoma patients?—a retrospective study of 161 patients from China. Cancers,14(20), 1–13. 10.3390/cancers14205126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]