Abstract

Objectives

Recent studies have confirmed the involvement of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in the pathogenesis of vascular complications in individuals with diabetes. Due to the discrepancy between the results of studies, a meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate MBL levels in patients with diabetes and its vascular complications.

Methods

We reviewed all observational studies published in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, EMBASE, and Web of Science Core Collection databases to identify relevant studies up to 1 April 2024. To account for describing heterogeneity among the studies, I2 and χ2 statistics were utilized. Also, a random-effects model was employed to combine the studies. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist was applied for quality assessment of each study.

Results

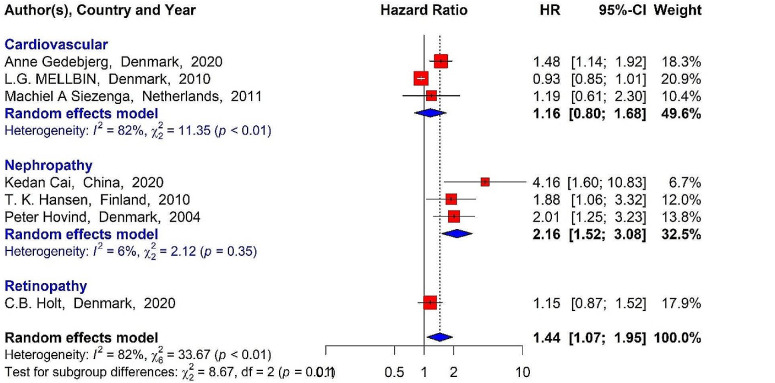

Twenty-eight papers were encompassed in this meta-analysis. The mean difference in MBL levels between patients with diabetic nephropathy and diabetic retinopathy differed significantly compared with the healthy control group and the diabetic group without vascular complications (P-value < 0.05). Moreover, the pooled results revealed a significant relationship between MBL levels and the incidence of vascular complications (pooled HR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.07–1.95, P-value < 0.05) and disease-related mortality (pooled HR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.07–2.16, P-value < 0.05) among diabetic patients. Also, there was a direct association between incidence of nephropathy in diabetics and higher levels of MBL (pooled HR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.52–3.08, P-value < 0.05).

Conclusion

Diabetic patients with elevated MBL levels are potentially at increased risk of vascular complications such as nephropathy and retinopathy. Therefore, by determining MBL status in diabetic patients, it is possible to predict the progress and possible consequences of the disease.

Keywords: Diabetes, Vascular complications, MBL, Inflammation, Complement system

Introduction

Diabetes is linked with higher morbidity and mortality rates among both developed and developing countries [1, 2]. The gradual progression of the vascular complications of diabetes such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and diabetic cardiomyopathy are considered the most important life-threatening risk factors in patients with the disease [3]. Despite the advancements in the treatment of diabetic patients, vascular complications are the most important and detrimental consequences and are associated with poor prognosis [4]. Cardiovascular diseases account for 80% of mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [5]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most common cause of new cases of vision loss among individuals aged 20 to 75. According to epidemiological studies, in the United States and China, about 29% and 14.8% of T2D patients had some degree of DR [6–8]. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is known as predominant cause of end-stage renal disease and the subsequent increased mortality rate in diabetic patients [9, 10].

According to reports by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), there are about 537 million individuals around the world living with diabetes, with more than 33% exhibiting symptoms of DR, and approximately one-third of these individuals experiencing vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) [8, 11–13]. In Iran, the prevalence of DR has been reported to be around 37.8% [11]. Furthermore, the prevalence of DN among individuals with diabetes has been reported to range from 30 to 40% [14], with the prevalence rate in Iran varying from 14.4% in Hamadan to 33.3% in Shahrekord [15].

Recent evidence has shown that the inflammation triggered by the innate immune system is a major factor in the pathogenic mechanism and occurrence of vascular complications in type 1 (T1D) and T2D patients [4, 16, 17]. Some studies have suggested that the components of the complement system such as C3, C4, and the expression and mannose-binding lectin (MBL) serum levels influence inflammatory and vascular components among patients with diabetes [18–22]. MBL, which is mainly synthesized by hepatocytes and belongs to the family of C-type lectins, is a components of the complement system and plays an essential role in the innate immune system [23]. Previous publications have reported the relationship between MBL levels and the prognosis of kidney transplantation, infectious diseases, pneumonia, and neonatal sepsis [24–26]. However, high levels of MBL may be associated with poor or worse prognosis in patients under certain conditions [27, 28]. Also, a strong link between the MBL genes expression and its serum levels with T1D and T2D has been confirmed by many research studies [29]. The evidence from epidemiological studies has shown that increased MBL levels in patients with microvascular and macrovascular complications led to poorer prognoses [4, 30, 31]. MBL may lead to an increased risk of vascular complications in diabetic patients through the activation of the complement system, the exacerbation of systemic and local inflammations, and the occurrence of endothelial disorders [32]. Some studies have shown that MBL levels are associated with the risk of vascular complications in diabetes [33–35], while findings from other studies show no such relationships [36, 37].

Although several studies have focused on examining the association between MBL levels and the prognosis of T1D and T2D and the associated vascular complications, the subject remains controversial. To address this controversy, we conducted a meta-analysis regarding the clinical importance of MBL levels for the prognosis of diabetic patients and the risk of vascular complications.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate MBL levels and the risk of diabetic complications according to the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) checklist [38] and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) standards [39], registered with PROSPERO under registration number CRD42023425069.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and EMBASE databases for all studies that investigated MBL levels in diabetic patients and the associated vascular complications published prior to 1 April 2024. The search was independently conducted by two researchers (KR & RSH) using the following keywords: “Mannose Binding Lectin”, “MBL”, “Diabetes”, “Diabetic Retinopathy”, “Diabetic Complication”, “Diabetic cardiomyopathy” and “Diabetic Nephropathy”. Any Inconsistencies were resolved by the other authors.

Eligibility criteria

We included all observational studies (i.e., prospective and retrospective cohort and case-control studies, as well as cross-sectional studies) published in English without time or location restrictions that investigated the role of MBL in patients with T1D and T2D and the associated vascular complications. Case reports, case series, letters, and correspondences were excluded from the review process (Fig. 1). Also, animal studies and studies on the genotypes and phenotypes of the MBL gene in affected individuals were excluded. Moreover, we excluded studies that lacked sufficient information on MBL levels in patients with diabetes.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the process of study selection

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two independent researchers (NAN & MF) extracted data from the included studies (Fig. 1). Any disagreements were resolved by the other reviewers. We extracted the following information: name of the first author, location of the study, study type, year of publication, type of vascular complication, median and interquartile range for MBL, and hazard ratio (HR). We calculated mean and standard deviation (SD) of MBL levels based on median, interquartile range, and sample size using scenario C3 of Wan et al. [40]. Quality assessment was independently performed by two researchers (MM & KR) using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) checklist [41] for observational studies. Studies with a total score of ≥ 7 were considered high-quality. Disagreements between the two reviewers regarding the quality of studies were resolved through group discussion and re-evaluation of the studies by other researchers.

Statistical analysis

R version 4.0.3 was used for all statistical analyses. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using I2 and χ2 statistics. I2 > 50% and P-value < 0.1 were used as the thresholds for heterogeneity among the studies. A random-effects approach was used to calculate pooled HR and pooled standard mean difference with 95% confidence interval (CI), and the inverse variance method was applied to weight the studies. A funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias. Also, we conducted sensitivity analysis to check the source of heterogeneity among studies. P-values < 0.5 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Based on our systematic search, 2281 records were identified in different databases. After removing duplicate and irrelevant results, 28 studies [1, 3, 18–20, 30, 31, 33–35, 37, 42–58] were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Among the included studies, 11 investigated T1D [3, 20, 34, 35, 42, 46, 47, 53–55, 58], 15 investigated T2D [1, 18, 19, 30, 31, 33, 37, 43, 45, 49–52, 56, 57], and 2 investigated both [44, 48]. All included studies were conducted on adults. Ten studies were conducted in China [1, 30, 43, 44, 49, 51, 52, 56–58], 9 were conducted in Denmark [19, 20, 33, 35, 37, 45–47, 53], and others were conducted in Finland [3, 34, 55], the Netherlands [31, 42], Brazil [48], Poland [54], Hungary [50], and Slovenia [43]. The studies included in this analysis were published from 2003 to 2022 (Table 1). All included studies had quality scores > 7, indicating high quality (Supplementary File 1 in Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis

| First author | Year | Country | Type of diabetes | Type of study | Complication | Diabetic | Diabetic with VC | Healthy control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kedan Cai [43] | 2020 | China | T2DM | Retrospective | Nephropathy | 44 | 33 | - |

| Tjaša Cerar [18] | 2014 | Slovenia | T2DM | Cross Sectional | Nephropathy | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| G. H. Dørflinger [19] | 2022 | Denmark | T2DM | Cross Sectional | - | 100 | - | 100 |

| Anne Gedebjerg [33] | 2020 | Denmark | T2DM | Prospective | Cardiovascular | 7305 | - | - |

| Peiliang Geng [44] | 2015 | China | T1D/T2DM | Case control | Retinopathy | 241 | 107 | 100 |

| Ling-Zhi Guan [1] | 2015 | China | T2DM | Case control | Nephropathy | 242 | 242 | 100 |

| T. K. Hansen [34] | 2010 | Finland | T1D | Prospective | Nephropathy | 1010 | 318 | - |

| Troels K. Hansen [45] | 2006 | Denmark | T2DM | Prospective | - | 326 | - | 80 |

| Troels K. Hansen [46] | 2004 | Denmark | T1D | Case control | Cardiovascular and Nephropathy | 192 | 199 | - |

| Troels K. Hansen [47] | 2003 | Denmark | T1D | Case control | - | 132 | - | 66 |

| Kenzo Hokazono [48] | 2018 | Brazil | T1D/T2DM | Cross Sectional | Retinopathy | 24 | 27 | 53 |

| C.B. Holt [20] | 2020 | Denmark | T1D | Prospective | Retinopathy | 270 | - | - |

| Peter Hovind [35] | 2005 | Denmark | T1D | Prospective | Nephropathy | 195 | 75 | - |

| Huiya Huang [49] | 2019 | China | T2DM | Retrospective | Nephropathy | 67 | 48 | - |

| Qian Huang [30] | 2015 | China | T2DM | Prospective | Retinopathy | 324 | 115 | - |

| Miklós Káplár [50] | 2016 | Hungary | T2DM | Cross Sectional | - | 103 | - | 98 |

| Mari A. Kaunisto [3] | 2009 | Finland | T1D | Cross Sectional | Nephropathy | 477 | 366 | - |

| X.-Q. Li [51] | 2019 | China | T2DM | Retrospective | Nephropathy | 68 | 30 | 30 |

| Xuejing Man [52] | 2015 | China | T2DM | Cross Sectional | Retinopathy | 189 | 184 | - |

| L.G. MELLBIN [37] | 2010 | Denmark | T2DM | Prospective | Cardiovascular | 387 | - | - |

| Jakob A. Østergaard [53] | 2015 | Denmark | T1D | Prospective | Nephropathy | 198 | - | - |

| Pertyńska − Marczewska [54] | 2009 | Poland | T1D | Cross Sectional | - | 14 | - | 15 |

| M. Saraheimo [55] | 2005 | Finland | T1D | Cross Sectional | Nephropathy | 67 | 62 | - |

| Machiel A Siezenga [31] | 2011 | Netherlands | T2DM | Prospective | Cardiovascular | 112 | 22 | - |

| Fang-Yu Song [56] | 2015 | China | T2DM | Prospective | Cardiovascular | 188 | 67 | 100 |

| Nana Zhang [57] | 2013 | China | T2DM | Case control | Nephropathy | 260 | 37 | - |

| Shi-qi Zhao [58] | 2016 | China | T1D | Cross Sectional | Nephropathy | 224 | 224 | - |

| Stefan P. Berger [42] | 2007 | Netherlands | T1D | Retrospective | - | 99 | - | - |

VC; Vascular Complication, NOS; Newcastle Ottawa Scale, T2D; Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, T1D; Type 1 Diabetes

Serum MBL levels in diabetic patients with vascular complications vs. healthy controls

Out of the 28 studies, six (493 diabetic patients with vascular complications and 403 healthy control subjects) investigated the mean difference in MBL levels. The findings indicated a significant difference in MBL levels between the two groups (SMD = 2.85, 95% CI: 0.38–5.33, P-value < 0.05). There was also significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 99%, P-value < 0.01). There was a significant difference in MBL levels between patients with DN (SMD = 2.24, 95% CI: -3.72-8.20, P-value < 0.05) and DR (SMD = 2.70, 95% CI: -26.35-31.74, P-value < 0.05) compared to the healthy control group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean MBL levels in diabetic patients with nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular complications compared to the healthy control group

Serum MBL levels in diabetic patients with vascular complications vs. diabetic control group

The meta-analysis included 18 studies (2355 diabetic patients with vascular complications and 4116 diabetic patients as a diabetic control group) investigated the difference in MBL levels in diabetics with and without vascular complications. The results revealed that there was a significant mean difference between the two groups (SMD = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.45–1.07). Also, there was significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 96%, P-value < 0.01). MBL levels in patients with DN was significantly different from those without DN (SMD = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.35–1.04, P-value < 0.05). In addition, a significant difference was found in the mean MBL level of patients with DR (SMD = 1.06, 95% CI: -0.39-2.50, P-value < 0.05) and those suffering from cardiovascular complications (SMD = 0.56, 95% CI: -1.03-2.16, P-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3). T2D patients had higher MBL levels than T1D patients (SMD = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.43–1.55, P-value < 0.05). Also, T1D patients with complications had significantly higher mean MBL levels compared to those without complications (SMD = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.15–0.99, P value < 0.05) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 3.

Mean MBL levels in diabetic patients with and without nephropathy, retinopathy and cardiovascular complications

Fig. 4.

Mean MBL levels in T1D and T2D patients with and without vascular complications

Fig. 5.

Mean MBL levels in T1D and T2D patients compared to the healthy control group

Incidence and mortality HR for diabetic patients associated with serum MBL levels

Seven studies examined the MBL levels in diabetic patients and the HR for the incidence of vascular complications and mortality. The pooled HRs for the MBL level and the incidence of vascular complications (HR pooled = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.07–1.95, P-value < 0.05) and mortality (HR pooled =1.52, 95% CI: 1.07–2.16, P-value < 0.05) were significant. Moreover, a significant direct association was identified between the patients’ MBL levels and the incidence of DN (HR pooled = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.52–3.08, P-value < 0.05), while this association was not significant for the incidence of cardiovascular complications (HR pooled= 1.16, 95% CI: 0.80–1.68, P-value > 0.05) or diabetes-related mortality (HR pooled= 1.28, 95% CI: -0.81 2.02, P-value > 0.05) (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6.

Incidence HR for diabetes-related vascular complications

Fig. 7.

Mortality HR for diabetes-related vascular complications

Meta-regression

Table 2 presents the results of meta-regression conducted to investigate heterogeneity among studies with respect to study type, year of publication, region, type of diabetes, and type of complications. The results clearly show that there was no statistically significant heterogeneity among the studies concerning the year of publication, region, type of diabetes (T1DM or T2DM), type of complications (including nephropathy and retinopathy), and study type (cross-sectional, prospective, and retrospective) (P-value > 0.05).

Table 2.

Results of meta-regression for region, type of diabetes, complications, and study type

| Groups | Coefficient(β) | SE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | -0.005 | 0.07 | 0.948 | |

| Region | Asia | 0.292 | 0.834 | 0.736 |

| Europe | -0.529 | 1.09 | 0.644 | |

| Type of Diabetes | DiabetesT1D/T2DM | -1.97 | 0.99 | 0.087 |

| Diabetes T2DM | -0.533 | 0.539 | 0.365 | |

| Type of Complications | Nephropathy | -0.394 | 0.399 | 0.351 |

| Retinopathy | 0.790 | 0.543 | 0.189 | |

| Type of Study | Cross sectional | -0.175 | 0.459 | 0.714 |

| Prospective | -0.594 | 0.412 | 0.192 | |

| Retrospective | 0.168 | 0.596 | 0.785 | |

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the impact of each included studies on the pooled results. We found that there was no significant difference among the included studies regarding the relationship between the incidence and mortality HR of MBL levels-related vascular complications in diabetic individuals. Also, no significant difference was detected among the studies included in the meta-analysis for the mean difference of MBL level in diabetic patients with vascular complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy and cardiovascular with healthy and diabetic control groups (Supplementary File 2 in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Publication bias

Publication bias was conducted with respect to mean difference in MBL in diabetic patients. Eggers’ test showed that there was no significant bias in the studies (P-value > 0.05). The funnel plot for the included studies was relatively symmetric. However, Egger’s test revealed significant bias with respect to the HR for incidence and mortality of diabetes-related vascular complications (P-value < 0.05) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits for standardized mean MBL differences in diabetics with vascular complications

Discussion

This meta-analysis investigated MBL and its role in the incidence of vascular complications (nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular complications) and mortality in diabetic patients. We found that diabetic patients with complications had significantly higher MBL levels compared to those without complications and healthy controls. Also, a significant relationship was identified between elevated MBL levels and the risk of developing vascular complications and mortality, which is in line with past studies on this subject [46, 55]. However, some studies report contrasting findings [31].

Although the results of the studies indicated the effect of increased MBL levels on the incidence of vascular complications in diabetic patients, the exact mechanisms driving this association remain unclear. One possible explanation is the potential activation of inflammatory pathways and disruption of endothelial functions. Animal studies have shown that the presence of severe endothelial disorders as a result of nitric oxide synthase deficiency is linked to progressive diabetic vascular complications [59]. Moreover, inhibition of MBL in animal models by reducing reperfusion injuries after strokes is accompanied by acute myocardial ischemia [60]. According to studies, the activation of the complement system is associated with the development of chronic inflammation and endothelial disorders [61, 62]. In this regard, Wang et al. [63] report that higher levels of MBL observed in patients with diabetes mellitus might play a role in the function and down-regulation of monocyte proliferation. Furthermore, there was an association between the incidence of vascular complications of diabetes and low-grade chronic inflammation [64]. Particularly, some low-grade inflammatory markers are associated with markers of endothelial dysfunction in diabetic patients without vascular complications, which strengthens the hypothesis of the existence of inflammatory pathogenesis in diabetic patients with vascular complications [65]. It should also be noted that the high expression of MBL2 gene is accompanied by the activation of other components of the complement system such as C5b-9 and the complement cascade. The activation of the complement system might be related to wider consequences in diabetic patients and potentially contribute to continuous inflammation and vascular complications [45].

Typically, between 30 and 40% of individuals with diabetes develop diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy, which can be influenced by various factors [66]. A portion of the observed difference in MBL levels between patients with diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy and those without complications could be attributed to the distribution of MBL genotypes in these individuals, which is recognized as a risk factor. On the other hand, the role of inflammation in the development of diabetic complications, such as nephropathy, has also been well demonstrated as a key pathogenic mechanism [67]. MBL may exacerbate inflammatory processes by activating the complement system and inducing the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines [68]. Another potential mechanism by which MBL could play a crucial role in the development of diabetic complications is through oxidative stress and its impact on endothelial function, as shown in humans and animal models [59, 69]. This meta-analysis demonstrated that serum MBL levels were significantly different in individuals with nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiomyopathy, and that elevated MBL levels could be considered a risk factor. Despite the presence of publication bias in the included studies, the analysis of the hazard ratio for the development of diabetic complications and the associated mortality showed a significant association between high MBL levels and the development of diabetic nephropathy. Additionally, the quality and setting of the studies are important factors that could contribute to considerable heterogeneity among the studies. However, there was no significant difference in the quality of the included studies.

Some studies report that approximately 70% of diabetic patients with high levels of MBL experience vascular complications during the progression of the disease [37, 45, 46, 57]. In addition, various factors influence an individual’s MBL level including the level of gene expression and endothelial dysfunction, but the evidence shows that MBL levels remain stable in the long term among healthy individuals [70]. In diabetic patients, increased MBL is associated with an increased risk of vascular complications and diabetes-related mortality, which was also shown in this study [34, 35, 43]. The results of pooled analysis also indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in MBL levels between diabetic patients with and without vascular complications and healthy controls. MBL can exacerbate local and systemic inflammation through the activation of the complement system and modulation of the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [68]. Also, MBL, through oxidative stress, potentially leads to vascular complications [69]. One study identified that MBL2 gene polymorphisms were associated with vascular complications in T2D [29], Hansen et al. also showed that serum MBL levels were significantly higher in diabetic subjects than the healthy control group [47], and Bouwman et al. reported an association between serum MBL levels and vascular complications in diabetic patients [71]. While increased MBL levels in T2D were associated with diabetes and its complications [72], Siezenga et al. found no association between log MBL levels and cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients [73]. Typically, the complement system is activated through either the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways. Evidence suggests an interplay between MBL and IgM, which leads to the activation of the lectin pathway. Furthermore, functional MBL deficiency has been associated with an increased risk of infections [45].

In this study, diabetics with vascular complications showed significantly higher MBL levels. Although there has been extensive research on the causes of vascular complications, their precise pathogenesis remains unclear, and it is uncertain whether elevated serum MBL levels are an independent marker or a causative factor in the development of these vascular complications. Evidence suggests that MBL functions as both a marker and an auxiliary factor, potentially driving several mechanisms. As an acute-phase reactant, MBL exhibits a slower and weaker response compared to CRP. Consequently, differences in serum MBL levels between diabetic patients with and without vascular complications may reflect the degree of their inflammatory activity [32]. However, the role of MBL in activating or modulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which exacerbate systemic or local inflammation, should not be ignored [68].

This meta-analysis has a number of limitations, including significant heterogeneity observed among the conducted studies, which was addressed through the utilization of random-effects model for analyzing serum MBL levels and the hazard ratios for the development of diabetic complications and the associated mortality. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies that have examined the hazard ratios for the development and mortality associated with diabetic complications. In addition to the significant publication bias, caution should be exercised in generalizing and interpreting the results to other patient populations. Moreover, serum MBL levels are dependent on the distribution of the MBL2 gene and its expression in different individuals, which is recognized as a risk factor. However, due to the heterogeneity in reporting among the studies, it was not possible to investigate this aspect in this meta-analysis. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness, ease of access, and applicability of MBL measurement were not evaluated, which is crucial for clinical applications.

Conclusion

Our findings revealed that diabetic patients with vascular complications exhibited significantly higher MBL levels compared to those without complications or healthy individuals. This difference was more pronounced in patients with T2D than in those with T1D. Furthermore, elevated MBL levels in diabetic patients were associated with an increased and significant risk of developing vascular complications and diabetes-related mortality. Therefore, monitoring and assessing MBL levels in diabetic patients could aid in predicting the occurrence of vascular complications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The original contributions listed in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Patient consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The all authors declared that they have no conflict of interest in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guan L-Z, Tong Q, Xu J. Elevated serum levels of mannose-binding lectin and diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1090–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaunisto MA, Sjölind L, Sallinen R, Pettersson-Fernholm K, Saraheimo M, Fröjdö S, et al. Elevated MBL concentrations are not an indication of association between the MBL2 gene and type 1 diabetes or diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1710–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Lin W, Li Z, Lin J, Wang S, Zeng C, et al. High expression of mannose-binding lectin and the risk of vascular complications of diabetes: evidence from a meta-analysis. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(7):490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flyvbjerg A. Diabetic Angiopathy, the complement system and the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2010;6(2):94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobrin Klein BE. Overview of epidemiologic studies of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14(4):179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Z, Fu C, Wang W, Xu B. Prevalence of chronic complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in outpatients-a cross-sectional hospital based survey in urban China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):137–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenoir O, Jasiek M, Hénique C, Guyonnet L, Hartleben B, Bork T, et al. Endothelial cell and podocyte autophagy synergistically protect from diabetes-induced glomerulosclerosis. Autophagy. 2015;11(7):1130–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heiran A, Azarchehry SP, Dehghankhalili S, Afarid M, Shaabani S, Mirahmadizadeh A. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2022;50(10):03000605221117134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodhini D, Mohan V. Diabetes burden in the IDF-MENA region. Medknow; 2022. pp. S1–2.

- 13.Teo ZL, Tham Y-C, Yu M, Chee ML, Rim TH, Cheung N, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1580–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang N, Zhu F, Chen L, Chen K. Proteomics, metabolomics and metagenomics for type 2 diabetes and its complications. Life Sci. 2018;212:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.OLFATIFAR M, KARAMI M, SHOKRI P, HOSSEINI SM. Prevalence of chronic complications and related risk factors of diabetes in patients referred to the diabetes center of Hamedan Province. 2017.

- 16.Girard D, Vandiedonck C. How dysregulation of the immune system promotes diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular risk complications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:991716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nedosugova LV, Markina YV, Bochkareva LA, Kuzina IA, Petunina NA, Yudina IY, et al. Inflammatory mechanisms of diabetes and its vascular complications. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerar T, Barlovič DP, Zorin A, Gregorič N, Kotnik V. Activation of complement system by mannan pathway and Mbl2 genotypes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Slovenian Med J. 2014;83(10).

- 19.Dørflinger G, Høyem P, Laugesen E, Østergaard J, Funck K, Steffensen R, et al. High MBL-expressing genotypes are associated with deterioration in renal function in type 2 diabetes. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1080388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt C, Hoffmann-Petersen I, Hansen T, Parving H, Thiel S, Hovind P, et al. Association between severe diabetic retinopathy and lectin pathway proteins–an 18-year follow-up study with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients. Immunobiology. 2020;225(3):151939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moin ASM, Nandakumar M, Diboun I, Al-Qaissi A, Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL, et al. Hypoglycemia-induced changes in complement pathways in type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis Plus. 2021;46:35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim K, Begum R, Yang C, Wang H. Complement activation in obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2020;11(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang W-C, White MR, Moyo P, McClear S, Thiel S, Hartshorn KL, et al. Lack of the pattern recognition molecule mannose-binding lectin increases susceptibility to influenza a virus infection. BMC Immunol. 2010;11(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bay JT, Sørensen SS, Hansen JM, Madsen HO, Garred P. Low mannose-binding lectin serum levels are associated with reduced kidney graft survival. Kidney Int. 2013;83(2):264–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisen DP, Minchinton RM. Impact of mannose-binding lectin on susceptibility to infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katakam L, Suresh GK. Identifying a quality improvement project. J Perinatol. 2017;37(10):1161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ezekowitz RAB. Genetic heterogeneity of mannose-binding proteins: the Jekyll and Hyde of innate immunity? Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(1):6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z-Y, Sun Z-R, Zhang L-M. The relationship between serum mannose-binding lectin levels and acute ischemic stroke risk. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang N-n, Ma A, Cheng P, Zhuang M, Cao F, Chen X, et al. Association between mannose-binding-lectin gene and type 2 diabetic patients in Chinese population living in the northern areas of China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua. Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2011;32(9):930–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Q, Shang G, Deng H, Liu J, Mei Y, Xu Y. High mannose-binding lectin serum levels are associated with diabetic retinopathy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0130665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siezenga MA, Chandie Shaw PK, Daha MR, Rabelink TJ, Berger SP. Low Mannose-Binding Lectin (MBL) genotype is associated with future cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetic South asians. A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen TK, Thiel S, Wouters PJ, Christiansen JS, Van den Berghe G. Intensive insulin therapy exerts antiinflammatory effects in critically ill patients and counteracts the adverse effect of low mannose-binding lectin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2003;88(3):1082–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gedebjerg A, Bjerre M, Kjaergaard AD, Steffensen R, Nielsen JS, Rungby J, et al. Mannose-binding lectin and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in type 2 diabetes: a Danish cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(9):2190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen T, Forsblom C, Saraheimo M, Thorn L, Wadén J, Høyem P, et al. Association between mannose-binding lectin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and the progression of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hovind P, Hansen TK, Tarnow L, Thiel S, Steffensen R, Flyvbjerg A, et al. Mannose-binding lectin as a predictor of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes: an inception cohort study. Diabetes. 2005;54(5):1523–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerl VB, Bohl S Jr, Stoffelns B, Pfeiffer N, Bhakdi S. Extensive deposits of complement C3d and C5b-9 in the choriocapillaris of eyes of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(4):1104–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mellbin L, Hamsten A, Malmberg K, Steffensen R, Ryden L, Öhrvik J, et al. Mannose-binding lectin genotype and phenotype in patients with type 2 diabetes and myocardial infarction: a report from the DIGAMI 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2451–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2011:1–12.

- 42.Berger SP, Roos A, Mallat MJ, Schaapherder AF, Doxiadis II, van Kooten C, et al. Low pretransplantation mannose-binding lectin levels predict superior patient and graft survival after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(8):2416–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai K, Ma Y, Wang J, Nie W, Guo J, Zhang M et al. Mannose-binding lectin activation is associated with the progression of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Annals Translational Med. 2020;8(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Geng P, Ding Y, Qiu L, Lu Y. Serum mannose-binding lectin is a strong biomarker of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):868–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen TK, Gall M-A, Tarnow L, Thiel S, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG, et al. Mannose-binding lectin and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(18):2007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen TK, Tarnow L, Thiel S, Steffensen R, Parving HH, Flyvbjerg A. Association between mannose-binding lectin and vascular complications in type 1 diabetes. Scand J Immunol. 2004;59(6):613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansen TK, Thiel S, Knudsen ST, Gravholt CH, Christiansen JS, Mogensen CE, et al. Elevated levels of mannan-binding lectin in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2003;88(10):4857–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hokazono K, Belizário FS, Portugal V, Messias-Reason I, Nisihara R. Mannose binding lectin and Pentraxin 3 in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Arch Med Res. 2018;49(2):123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang H, Li D, Huang X, Wang Y, Wang S, Wang X, et al. Association of complement and inflammatory biomarkers with diabetic nephropathy. Annals Clin Lab Sci. 2019;49(4):488–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Káplár M, Sweni S, Kulcsár J, Cogoi B, Esze R, Somodi S et al. Mannose-binding lectin levels and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients. Journal of diabetes research. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Li X-Q, Chang D-Y, Chen M, Zhao M-H. Complement activation in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45(3):248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Man X, Zhang H, Yu H, Ma L, Du J. Increased serum mannose binding lectin levels are associated with diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29(1):55–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Østergaard JA, Thiel S, Lajer M, Steffensen R, Parving H-H, Flyvbjerg A, et al. Increased all-cause mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes and high-expression mannan-binding lectin genotypes: a 12-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pertyńska– Marczewska M, Cedzyński M, Świerzko A, Szala A, Sobczak M, Cypryk K, et al. Evaluation of lectin pathway activity and mannan-binding lectin levels in the course of pregnancy complicated by diabetes type 1, based on the genetic background. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2009;57:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saraheimo M, Forsblom C, Hansen T, Teppo A-M, Fagerudd J, Pettersson-Fernholm K, et al. Increased levels of mannan-binding lectin in type 1 diabetic patients with incipient and overt nephropathy. Diabetologia. 2005;48:198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song F-Y, Wu M-H, Zhu L-h, Zhang Z-Q, Qi Q-D, Lou C-l. Elevated serum mannose-binding lectin levels are associated with poor outcome after acute ischemic stroke in patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:1330–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang N, Zhuang M, Ma A, Wang G, Cheng P, Yang Y, et al. Association of levels of mannose-binding lectin and the MBL2 gene with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sq Z. Mannose-binding lectin and Diabetic Nephropathy in Type 1 diabetes. J Clin Lab Anal. 2016;30(4):345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner MW. The role of mannose-binding lectin in health and disease. Mol Immunol. 2003;40(7):423–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jordan JE, Montalto MC, Stahl GL. Inhibition of mannose-binding lectin reduces postischemic myocardial reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2001;104(12):1413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Acosta J, Hettinga J, Flückiger R, Krumrei N, Goldfine A, Angarita L, et al. Molecular basis for a link between complement and the vascular complications of diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97(10):5450–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pavlov VI, La Bonte LR, Baldwin WM, Markiewski MM, Lambris JD, Stahl GL. Absence of mannose-binding lectin prevents hyperglycemic cardiovascular complications. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(1):104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Chen A-D, Lei Y-M, Shan G-Q, Zhang L-Y, Lu X, et al. Mannose-binding lectin inhibits monocyte proliferation through transforming growth factor-β1 and p38 signaling pathways. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e72505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen T. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and vascular complications in diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37(S 1):95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Østergaard J, Hansen TK, Thiel S, Flyvbjerg A. Complement activation and diabetic vascular complications. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;361(1–2):10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakagawa T, Tanabe K, Croker BP, Johnson RJ, Grant MB, Kosugi T, et al. Endothelial dysfunction as a potential contributor in diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(1):36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Navarro-González JF, Mora-Fernández C, De Fuentes MM, García-Pérez J. Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(6):327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collard CD, Väkevä A, Morrissey MA, Agah A, Rollins SA, Reenstra WR, et al. Complement activation after oxidative stress: role of the lectin complement pathway. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(5):1549–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pan H-z, Zhang L, Guo M-y, Sui H, Li H, Wu W-h, et al. The oxidative stress status in diabetes mellitus and diabetic nephropathy. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cedzynski M, Szemraj J, Świerzko A, Bak-Romaniszyn L, Banasik M, Zeman K, et al. Mannan-binding lectin insufficiency in children with recurrent infections of the respiratory system. Clin Experimental Immunol. 2004;136(2):304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bouwman LH, Eerligh P, Terpstra OT, Daha MR, de Knijff P, Ballieux BE, et al. Elevated levels of mannose-binding lectin at clinical manifestation of type 1 diabetes in juveniles. Diabetes. 2005;54(10):3002–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elawa G, AoudAllah AM, Hasaneen AE, El-Hammady AM. The predictive value of serum mannan-binding lectin levels for diabetic control and renal complications in type 2 diabetic patients. Saudi Med J. 2011;32(8):784–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siezenga MA, Chandie Shaw PK, Daha MR, Rabelink TJ, Berger SP. Low mannose-binding lectin (MBL) genotype is associated with future cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetic south asians. A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions listed in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.