Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most common gynecological malignancies and poses a severe health risk to women. In recent years, ferroptosis therapy has been considered a promising therapeutic strategy for breast cancer by promoting intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and lipid peroxidation (LPO) accumulation. However, insufficient intracellular ROS levels and suboptimal drug accumulation within breast cancer lesions hinder the efficacy of ferroptosis as a single oncological treatment modality. In this study, we developed a self-targeting biomineralized apoferritin-based nanovector, encapsulating the ferroptosis inducer dihydroartemisinin (DHA), to create a synergistic antitumor nano-platform (Ca/DHA@AFn) capable of achieving dual-mode calcicoptosis and ferroptosis therapy. The Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles exhibited uniform distribution, with an average particle size of approximately 20 nm and a drug loading efficiency of 2.32%. MTT assay results demonstrated that Ca/DHA@AFn significantly decreased the viability of 4T1 cells compared to the controls (DHA, Ca@AFn, and DHA@AFn), indicating enhanced therapeutic efficacy. In vivo experiments in mice revealed that Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles, through combined calcicoptosis/ferroptosis induction, exhibited superior synergistic antitumor effects compared to single-modality treatments, significantly extending survival and demonstrating high biocompatibility. This study introduces a novel and safe biomineralized apoferritin-based nano-platform leveraging calcicoptosis/ferroptosis dual therapy, showing strong antitumor efficacy against breast cancer cells and presenting a promising strategy for breast cancer treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-80735-1.

Keywords: Nano delivery system, Apoferritin, Dihydroartemisinin, Calcicoptosis, Ferroptosis

Subject terms: Cancer, Oncology, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

Malignant tumors have emerged as a significant threat to human health. According to the World Health Organization’s Global Cancer Statistics Report (2020), there were 19.29 million new cancer cases and 9.96 million deaths worldwide. The report anticipates a substantial increase in cancer cases, projecting 28.4 million cases globally in 2040—an alarming surge of 47% from 2020. These statistics encompass 36 types of cancer across 185 countries1. Breast cancer is one of the most common gynecological malignancies and a severe threat to women’s health2. Breast Cancer treatment often involves a variety of therapeutic modalities, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, etc3. Early-stage cancer is usually treated by surgery, which mainly consists of the removal of the lesion and surrounding normal tissues and lymph nodes to achieve a cure4. However, the recurrence rate of surgical treatment is high because of the difficulty in detecting potentially diseased cells and the technical obstacles to removing them completely. In the intermediate and late stages of cancer, radiotherapy or chemotherapy is usually used in combination with surgery5. Therefore, efficient treatment of breast cancer remains an open clinical challenge.

Ferroptosis therapy (FT) is an iron-dependent programmed cell death driven by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation as well as lipid peroxide (LPO) accumulation on cancer cell membranes6. DHA can be used as an emerging tumor ferroptosis therapeutic agent, and its anticancer mechanism is that DHA molecules contain peroxo-bridged structures that generate reactive oxygen radicals through the Fenton reaction with transition metal ions (ions such as Fe2+, Mn2+, etc.) to kill cancer cells7. DHA has been shown to have significant cytotoxicity against a wide range of tumor cells, including breast cancer, with high efficacy and no significant side effects8. Due to its poor water solubility, DHA cannot be selectively distributed in the body after injection. Its short half-life and relatively low in vivo bioavailability limit its further clinical applications9. In addition, single modes of tumor iron-death therapy often suffer from the disadvantages of lower-than-expected therapeutic efficacy and susceptibility to tumor recurrence. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a synergistic antitumor nanoplatform to overcome these challenges.

Due to their widespread presence in the human body, ions have attracted the attention of scientists because of their involvement in various life processes10. Abnormal distribution or specific accumulation of some metal or non-metal ions in cells, causing irreversible damage to cells or activating cytotoxicity-related biochemical reactions to induce cell death, has provided a new therapeutic concept for tumor treatment, i.e., ionic interfering therapy11. Calcium ions, as second messengers in cell signaling, have many physiological functions, including muscle contraction, neuronal excitation, cell migration and growth, and cell death12. In recent years, research on calcium ions has developed rapidly in the fields of neurology, physiology, and cell biology, and the role of calcium ions in tumor therapy has gradually come to the attention of scientists. “Calcicoptosis is the regulation of the concentration of calcium ions in tumor cells to overload the concentration of calcium ions, thereby triggering various calcium-based signaling pathways in the cells and inducing the death of cancer cells13. Calcium ions have a broad research perspective in the field of tumor therapy.

Apoferritin (AFn), a natural bio-based nanomaterial, is widely found in various plant, animal, and microbial cells and has attracted the attention of many researchers14. AFn, an iron-free ferritin, is a hollow cage-like molecule consisting of 24 protein subunits with inner and outer diameters of approximately 8 and 12 nm, respectively14. AFn has a much smaller particle size, high penetration capacity, good biocompatibility, pH sensitivity, mineralisability, and TfR1 targeting, making it an excellent drug carrier15–18. In this study, we designed and constructed a calcium-mineralized protein cage particle (Ca/DHA@AFn, Fig. 1) by selecting TfR1 self-targeting AFn as a delivery vehicle and DHA as an iron death inducer and used Ca2+ as an intracellular “calcium bomb” to achieve “calcicoptosis” of cancer cells in response to an acidic microenvironment for the treatment of breast cancer. Using Ca2+ as an intracellular “calcium bomb”, the acidic microenvironment response induces cancer cell “calcicoptosis” to treat breast cancer. At the same time, AFn-loaded DHA can generate carbon-based free radicals or ROS and promote lipid peroxidation (LPO) to induce iron death in breast cancer, ultimately achieving the integrated breast cancer treatment of calcicoptosis/ferroptosis by “killing two birds with one stone”.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration for synthesizing Ca/DHA@AFn and the principle of ferroptosis and calcicoptosis for tumor therapy based on Ca/DHA@AFn.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), a derivative of artemisinin, is the most promising anticancer drug due to its specific antitumor properties and fewer side effects19. However, DHA suffers from inherent deficiencies such as poor water solubility, low stability, and short plasma half-life, which limit its efficacy and clinical application20. Therefore, there is an urgent need for rationally designed carriers to improve the ferroptosis anticancer effectiveness of DHA. Currently, some nanoscale drug carriers have been used to maximize the effectiveness of DHA. Yan Y et al. designed and synthesized a metal-organic framework (MOF) carrier based on zeolite imidazolium salt skeleton-8 and loaded DHA (ZIF-DHA) into the MOF core. The prepared ZIF-DHA nanoparticles (NPs) showed better antitumor therapeutic activity in various ovarian cancer cells than free DHA, inhibiting cellular ROS production and inducing apoptosis21. Huang et al. developed a DHA-loaded Fe3+-doped manganese dioxide nanosheets (Fe-MnO2/DHA), and the DHA-loaded nanoparticles induced multimodal programmed cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, which was significantly more effective in cancer therapy compared to free DHA22. Similarly, this study constructed Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles for calcicoptosis/ferroptosis based on AFn nanocarriers. The results of the UV scanning curve of DHA are shown in Fig. 2A, and the maximum absorption peak was found at 241 nm, so this wavelength was chosen for methodological analysis. The standard curve of DHA was plotted, and the results are shown in Fig. 2B. The linear regression equation was found to be y = 0.0258x-0.0021, R2 = 0.999, which can be seen from the figure that it showed linear correlation within the concentration range of 0 ~ 25 µg/mL and can be used to determine DHA. In this experiment, the ratio of DHA to Ca was screened, and the results (Table S1) showed that when the ratio of DHA to Ca was 4:1, the inhibition rate of Ca/DHA@AFn reached the maximum for both types of cancer cells, and therefore the Ca/DHA@AFn prepared at this ratio was selected for further research exploration. The encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity of DHA were 73.54% and 2.3%, respectively, while those of Ca were 61.4% and 1.7%, respectively. Since the particle size and potential distribution of the drug delivery system have a significant effect on the stability of the drug delivery system, the potential and particle size of AFn and Ca/DHA@AFn were determined in this study23. The results are shown in Fig. 2C and F. The AFn potential is -10.64 mV, and the Ca/DHA@AFn potential increases to -8.52 mV, indicating good stability. AFn and Ca/DHA@AFn have particle sizes of approximately 20 nm. After Ca2+ mineralization, Ca/DHA@AFn nanopreparations maintain small particle size, with the unique tumor high permeability and long retention effect of nanopreparations24. The morphology of AFn and the final preparation Ca/DHA@AFn was observed by transmission electron microscopy, and the results, as shown in Fig. 2G and H, showed that AFn had a distinct cage-like structure with uniform size and uniform dispersion, consistent with the description in the literature. Meanwhile, the Ca/DHA@AFn produced after mineralization had a spherical structure with apparent Ca cores and uniformly dispersed nanoparticles, indicating that the preparation was successfully constructed. The average drug loading of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles was 2.32%. To evaluate the acid-responsive smart controlled release behavior of Ca/DHA@AFn, the DHA and Ca2+ release from the formulations under acid-responsive conditions was separately investigated in this experiment, and the results are shown in Fig. 2I and J. As can be seen from the figure, the DHA release rate of Ca/DHA@AFn at pH 7.4 (normal physiological environmental pH) was less than 20% within 24 h. However, when this controlled release system was at pH 5.0 (tumor microenvironment pH), the unique acidic state of desferrin, which can be cleaved and reassembled, increased the channel aperture of the protein cage, promoting drug release and the drug release rate of DHA was as high as 70%. Similarly, the released Ca2+ was much higher under acidic conditions than under neutral pH conditions. Therefore, when the drug delivery system is injected intravenously into the body, the drug can be explicitly released in response to the micro-acidic environment of the tumor and play a therapeutic role in oncology. In conclusion, the nanoparticles exhibited uniform particle size distribution, moderate drug loading capacity, good stability, and acid-responsive release, providing a formulation basis for evaluating antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 2.

(A) In vitro UV scanning results of DHA, (B) UV standard curve of DHA in vitro, (C) Particle size diagram of AFn, (D) Potentiogram of AFn, (E) Particle size diagram of Ca/DHA@AFn, (F) Potentiogram of Ca/DHA@AFn, (G) Transmission electron micrographs image of AFn nanoparticles, (H) Transmission electron micrographs image of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles. (I) DHA release behavior of Ca/DHA@AFn in different pH. (J) Ca2+ release behavior of Ca/DHA@AFn in different pH. (K) Stability evaluation of DHA in DHA@AFn NPs within 10 days. (L) The stability of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles in 10% FBS at room temperature.

Stability study

This study initially assessed the stability of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles. As depicted in Fig. 2K, the results revealed no significant degradation of DHA in either the free DHA solution or Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles when stored at neutral pH for 10 days, with both exhibiting stability levels exceeding 90%. This suggests that DHA remains stable under storage conditions at neutral pH, and the presence of AFn does not compromise the molecular stability of DHA. In summary, Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles exhibit robust stability, enabling short-term storage in vitro and ensuring the drug’s stability during blood circulation. Also, the stability of Ca/DHA@AFn was evaluated by DLS under 10% FBS conditions for 10 days. No size or zeta potential variation was observed, indicating the excellent stability of Ca/DHA@AFn (Fig. 2L).

In vitro antitumor activity of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles

To investigate the cytotoxicity and in vitro antitumor effect of this drug delivery system, the cell viability of 4T1, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells after 48 h incubation with each formulation was determined in this experiment. The effects of AFn nanocarriers on the activity of 4T1 and MCF-7 cells are shown in Fig. 3A and Fig. S1A. None of the AFn nanoparticles had a significant inhibitory effect on the activity of 4T1 and MCF-7 cells in the concentration range of 0–1 mg/mL. The results indicated that both 4T1 and MCF-7 cells were compatible with AFn nanoparticles.

Fig. 3.

Cellular level antitumor test results. (A) Cytotoxicity evaluation of AFn NPs in 4T1 cells after 24 and 48 h incubation. (B) Cytotoxicity of DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@Afn, and Ca/DHA@AFn NPs at different concentrations in 4T1 cells after incubation for 48 h. (C) Synopsis of the corresponding half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of B. Statistical significance denoted as **p < 0.01. Error bars represent ± SD (n = 3).

To investigate the cytotoxicity and in vitro antitumor effect of the Ca/DHA@AFn delivery system, the cell viability of 4T1, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells was determined in this experiment after 48 h of incubation with each preparation. The results are shown in Fig. 3B, Fig. S1B, Fig. S2A. The results of the MTT assay showed that Ca@AFn was cytotoxic to three cells, suggesting that Ca mineralization induces calcicoptosis in breast cancer cells. DHA, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn concentrations exhibited concentration-dependent cytotoxicity at three breast cancer cell levels after 48 h incubation. DHA@AFn was more cytotoxic than the same DHA concentration, suggesting that DHA nano partitioning can significantly enhance ferroptosis activity. Among all treatment groups, Ca/DHA@AFn showed the most potent cytotoxicity with the lowest IC50 value (Fig. 3C, Fig. S1C, Fig. S2B) in three types of breast cancer cells at the same DHA concentration, significantly different from the other treatment groups. This suggests that Ca/DHA@AFn can be better treated by ferroptosis combined with calcicoptosis than by ferroptosis alone.

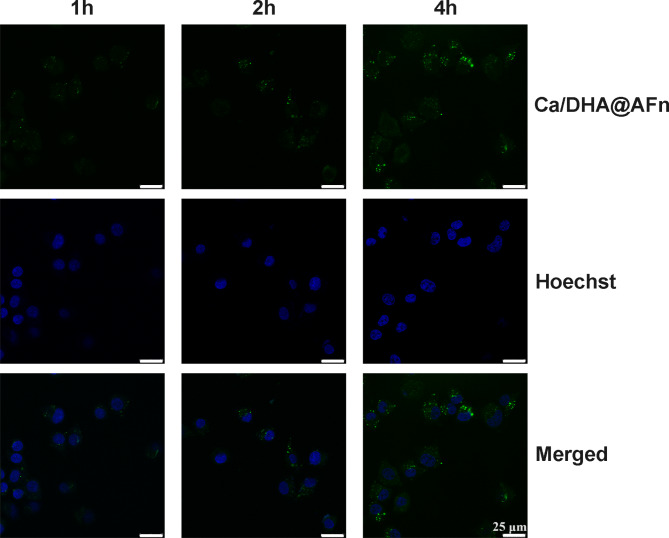

Cellular uptake

Cellular uptake significantly affects drug efficacy for nanoparticle drug delivery systems25. Therefore, our designed nanoparticles must have the ability to be efficiently taken up by cancer cells to exert sound anticancer effects. To verify this ability, we observed the uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn by 4T1 cells using fluorescence microscopy. The results are shown in Fig. 4: as the co-incubation time between Ca/DHA@AFn and 4T1 cells increased, the fluorescence intensity of FAM observed under the microscope gradually increased. At 4 h, the intracellular fluorescence intensity was most vigorous during the experiment, indicating that the cellular uptake behavior of Ca/DHA@AFn showed a time dependence. This suggests that if the in vivo circulation time of Ca/DHA@AFn is increased, the uptake of cancer cells will be improved, and the drug’s therapeutic effect will be enhanced.

Fig. 4.

Cellular level antitumor test results Confocal images of 4T1 cells treated with the FAM-Ca/DHA@AFn at 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h, respectively.

Examination of cellular uptake mechanisms

The investigations above underscored the robust uptake capability of Ca/DHA@AFn by 4T1 cells. However, delving into the uptake mechanism is paramount for enhancing drug delivery efficiency and facilitating the optimized design and dosing recommendations for subsequent applications. Thus, we delved into elucidating the endocytic mechanism of Ca/DHA@AFn by 4T1 cells utilizing inverted fluorescence microscopy. The ultimate uptake behavior was scrutinized by modulating various uptake pathways using specific inhibitors. Specifically, three inhibitors were employed: chlorpromazine targeting clathrin-mediated endocytosis, genistein flavonoid targeting the endosomal-lysosomal pathway, and amiloride, a Na+/K+ exchange inhibitor selectively impeding macropinocytosis26. The untreated cells served as the control group. Our findings, as depicted in Fig. 5A and B, revealed no notable reduction in the uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn in cells pre-treated with amiloride and genistein flavonoids compared to the untreated control, suggesting that inhibition of lysosomal and macropinocytic pathways did not hinder cellular uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn NPs. This indicates that these pathways are either minimally involved or not involved in the cellular uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn NPs. Conversely, fluorescence observations and quantitative analyses post chlorpromazine treatment exhibited a significant reduction in cellular uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn compared to the control group, indicative of prominent uptake inhibition effects. This preliminary evidence suggests that cellular phagocytosis may play a predominant role in the uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn NPs, emphasizing the involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis as the primary mechanism for Ca/DHA@AFn NPs internalization by cancer cells.

Fig. 5.

(A) Fluorescence imaging of 4T1cells treated with different inhibitors. (a) control, (b) genistein, (c) chlorpromazine, (d) amiloride. (B) Quantitative statistical analysis of (A) fluorescence using Image J, *** p < 0.001 vs. control. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Determination of intracellular ROS and LPO content

In vitro cell growth inhibition assays indicate that Ca/DHA@AFn has significant cytotoxicity and can effectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells. The mechanism may be related to the fact that DHA can increase ROS in cancer cells through a Fenton-like reaction, which induces ferroptosis in tumor cells27. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, the control group showed the lowest fluorescence intensity, i.e., the lowest ROS content, indicating that ROS are present in cancer cells under normal physiological conditions. Still, their content is low enough to damage cell structure or induce apoptosis. Compared with the control group, 4T1 cells treated in each treatment group showed higher ROS fluorescence intensity, suggesting that the mechanism of the anticancer effect of 4T1 is to mediate apoptosis in cancer cells by inducing the production of ROS7,28. In addition, all Ca/DHA@AFn-treated 4T1 cells showed significantly stronger green DCF fluorescence than those in the DHA and DHA@AFn groups, suggesting that Ca/DHA@AFn-mediated ferroptosis and calcicoptosis may combine to enhance the ability to induce ROS generation. The above results indicate that Ca/DHA@AFn can generate higher levels of ROS in cells and induce cell death, which is consistent with the MTT results above.

Fig. 6.

(A) Fluorescence images indicate the intracellular ROS assay of 4T1 cells after being treated with DHA, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn. Untreated cells were set as the control. (B) Quantitative statistical analysis of (A) fluorescence using Image J, *** p < 0.001 vs. control. (C) Fluorescence images showing the intracellular LPO assay of 4T1 cells after treatment with DHA, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn.

When ROS accumulate in large quantities in cells, they are partially converted to LPO, one of the critical indicators of ferroptosis [57]. Therefore, the fluorescent probe C11-BODIPY was used to detect the level of intracellular LPO. As shown in Fig. 6C, only weak fluorescence was observed in DHA, indicating that they produce little LPO. In contrast, a slight increase in green fluorescence was observed in the DHA@AFn group, indicating that a moderate amount of LPO was produced. More importantly, strong fluorescence appeared after incubating the cells with Ca/DHA@AFn. This suggests that the combined effect of Ca/DHA@AFn-mediated ferroptosis and calcicoptosis leads to large amounts of LPO, responsible for its more significant toxicity than free DHA and DHA@AFn. Thus, the nano platform could further induce ferroptosis by accumulating intracellular LPO.

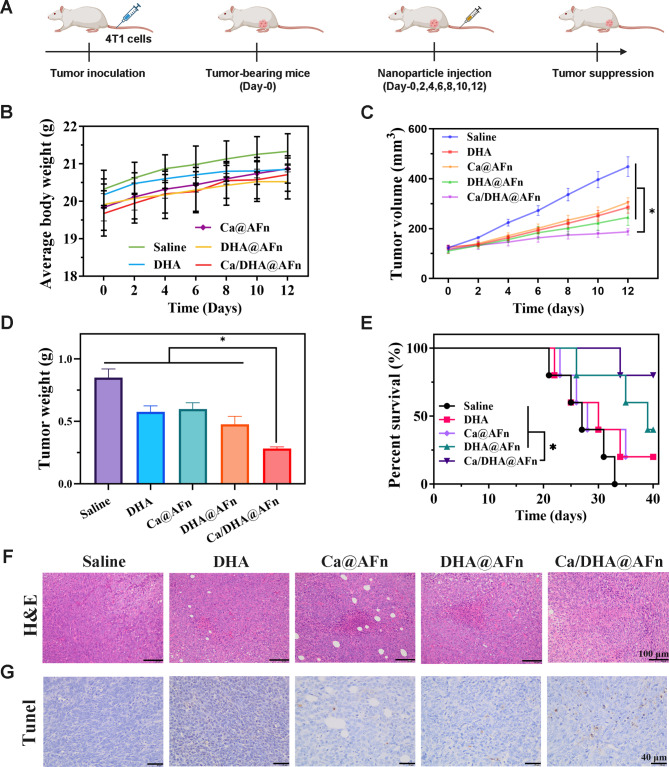

Antitumor effect in vivo

To assess the potential of the Ca/DHA@AFn delivery system in enhancing in vivo antitumor efficacy, 4T1 subcutaneous xenograft tumor models in mice (Fig. 7A) were treated and observed over a 12-day period, with tumor growth monitored closely in all groups. Body weights were recorded every two days throughout the treatment course (Fig. 7B). Results indicated that body weights in the treatment group were comparable to those of the control group, with a general upward trend observed over the 12-day period, suggesting favorable biosafety for the Ca/DHA@AFn delivery system. As illustrated in Fig. 7C, tumor volumes in the saline-treated group exhibited rapid growth, while groups treated with DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn displayed tumor-suppressive effects. Notably, the Ca/DHA@AFn group demonstrated the most pronounced antitumor efficacy. These findings indicate that the combination of calcicoptosis and ferroptosis in the Ca/DHA@AFn treatment enhances antitumor activity more effectively than either Ca@AFn or DHA@AFn alone. At the conclusion of treatment, all mice were euthanized, and tumors were excised for mass measurement. As shown in Fig. 7D, consistent with findings observed during the treatment period, the Ca/DHA@AFn group exhibited the lowest tumor mass among all groups. In a 40-day survival study using the same model and dosing regimen (Fig. 7E), the Ca/DHA@AFn-treated group demonstrated the highest overall survival rate, indicating minimized adverse effects and enhanced cancer-specific cytotoxicity in mice. Tumor necrosis analysis using H&E staining and apoptosis evaluation via TUNEL assay revealed that the Ca/DHA@AFn-treated group exhibited the highest levels of cell apoptosis and necrosis (Fig. 7F and G). In detail, H&E staining showed extensive necrotic regions with nuclear condensation, while TUNEL staining demonstrated a significant increase in fluorescein-labeled DNA in apoptotic cells, with markedly enhanced staining intensity and area in brown. Thus, findings from H&E and TUNEL analyses indicate that the co-delivery of Ca and DHA through Ca/DHA@AFn enables an effective calcicoptosis-ferroptosis combination therapy, significantly enhancing anticancer efficacy. To further evaluate the toxicity and application potential of Ca/DHA@AFn, H&E staining was performed on the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney obtained from anatomical isolation of homozygous mice at the end of treatment. The results (Fig. S3) showed that Ca/DHA@AFn did not induce pathological changes in these organs; all cells aligned well. AFn, as an endogenous protein, has excellent properties such as low immunogenicity, high biocompatibility, and easy degradation. This ensures the safety of AFn drug carriers during in vivo delivery and lays the foundation for their translational applications in biomedicine29.

Fig. 7.

Ca/DHA@AFn exhibited the strongest in vivo antitumor efficacy. (A) Treatment scheme of saline, DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn. (B) Mouse weight is recorded every 2 days. (C) Tumor growth curve with different treatments. (D) Tumor weights 12 days after the end of treatment. (F) H&E staining of tumors collected 12 days after the end of treatment. Excised tumors following treatment with saline, DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn. (E) A 40-day survival observation experiment in mice. (E) The HE staining images of tumor tissues from BALB/c mice after being treated with saline, DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn. (E) The Tunel images of tumor tissues after being treated with saline, DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn.

Hemolysis test and biochemical index determination

The relevant safety test results for Ca/DHA@AFn are shown in Fig. 8. The in vitro red blood cell hemolysis test assessed the hemolysis rates of the carrier materials AFn and Ca/DHA@AFn. Findings revealed a marginal increment in hemolysis rates with the rise in mass concentration within the experimental range. AFn and Ca/DHA@AFn exhibited hemolysis rates below 5%, affirming their commendable biosafety for intravenous administration30. The mice underwent injection with Ca/DHA@AFn, and subsequent blood collection enabled the assessment of in vivo biochemical indexes. No statistically significant variations were observed across all measured parameters compared to the negative control group. These findings suggest that Ca/DHA@AFn exhibits negligible hepatorenal toxicity in vivo.

Fig. 8.

The safety test results of Ca/DHA@AFn. (A) After being incubated with Ca/DHA@AFn of different concentrations, the hemolysis ratio of murine blood. (B–E) Blood biochemistry and routine blood analysis data.

Materials and methods

Materials

UV-1200 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Unocal (Shanghai) Instruments Co., Ltd.), FA2004 one million electronic balance (Mettler Toledo Instruments Co., Ltd.), pHS-3 C pH meter (Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd.), KQ-500DB CNC ultrasonic instrument (Kunshan City Ultrasonic Instrument Co., Ltd.), Model 1510–02820 C Enzyme Labeler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), Model JB-2 Constant Temperature Stirrer (Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.), Model JEM-F200 Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL, Japan).

DHA and sodium chloride were purchased from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd; potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH₂PO₄) was purchased from China National Pharmaceutical Group Co, Ltd; anhydrous disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na₂HPO₄) was purchased from Shanghai Hutiao Chemical Co., Ltd; anhydrous sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) was purchased from Wuxi Yasheng Chemical Co.

The participants in this investigation consisted of female Balb/c mice, aged between 4 and 6 weeks, with body weights falling within the range of 16 to 18 g. These mice were obtained from Hangzhou Ziyuan Experimental Animal Technology Co. and were housed in a regulated environment with a temperature set at 22–25 ℃ and a relative humidity of 50%. The mice were provided unrestricted access to food and water throughout the study. The Jinzhou Medical University Animal Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for the experimental procedures involving animals.

Preparation of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles

AFn nanoparticles dissociate completely at pH < 2.0 or pH > 12.0, often forming pores in AFn after reconstitution31. In this study, a pH-based substituent depolymerization/reorganization strategy was used to encapsulate DHA in the cavities of AFn32. Briefly, subunit dissociation of AFn was achieved by lowering the pH to 2.5 by adding 0.1 M HCl. A 20 mM CaCl2 solution was then added. At the same time, an appropriate amount of precisely measured DHA solution was added and incubated for 30 min at 60 ℃ with shaking. The pH of the mixture was then adjusted to 8.0 by dropwise addition of 0.1 M NaOH, and 10 mM Na2HPO4 was added. The mixture was shaken continuously at 0.1 g for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the solution was transferred to an ultrafiltration tube (MWCO = 100 kDa), and 700 µL phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 0.025 M) was added and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 s. The process was repeated 3–5 times to remove the unencapsulated drug to obtain Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles.

Characterization of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles

Accurately weigh 4 mg of DHA in a 50 mL volumetric flask, add 2% NaOH solution, ultrasonically (frequency 40 kHz, power 200 W) dissolved and diluted to the scale, and shake well as reservoir solution. Precisely measure 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3.0 mL of the reservoir solution into a 10 mL volumetric flask, add 2% NaOH dilution to the scale, and shake well to prepare a series of 6, 8, 12, 16, 24 µg/mL solution. The reaction was conducted at 60 ℃ in a constant temperature water bath for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 241 nm by UV-visible spectrophotometer and linear regression was performed with absorbance (y) as the vertical coordinate and DHA mass concentration (x, µg/mL) as the horizontal coordinate, and the regression equation was obtained as y = 0.0258x-0.0021 (R2 = 0.999), which indicated that the linearity of the assayed mass concentration of DHA was good in the range of 5 ~ 50 µg/mL.

Suitable quantities of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles were extracted and diluted with water. A droplet of this solution was carefully deposited onto a copper grid, followed by staining with a 1% phosphotungstic acid solution for 60 s. Any surplus staining solution was absorbed using filter paper, and the grid was left to air-dry naturally at room temperature. The prepared samples were then observed through transmission electron microscopy.

A suitable Ca/DHA@AFn solution concentration was added to a specific quartz cell vessel, and the sample’s size distribution and potential values were analyzed using a laser particle size analyzer.

0.5 mL of the Ca/DHA@AFn sample was accurately aspirated and dissolved with a pH 2.0 solution to release the encapsulated DHA from the AFn protein. Centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was collected for quantification, the absorbance value was measured, the DHA content was calculated using a standard curve, and the drug loading of Ca/DHA@AFn was calculated. The drug loading (%) = We/Wm×100%, Encapsulation efficiency = We/W1 × 100%, where We is the amount of drug encapsulated in the nanoparticle, Wm is the total mass of the nanoparticle, and W1 is the total mass of the DHA.

The DHA and Ca2+ release assay was performed by dialysis. Ca/DHA@AFn was prepared as an aqueous solution at a concentration of 50 µg/mL, 2 mL of this solution was placed in a dialysis bag (MWCO = 8000) and shaken, and 1 mL of dialysate was collected at predetermined time intervals (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 h). In contrast, an equal volume of new dialysate was provided. The dialysis experiment was conducted using 20 mL of PBS as the dialysate, with the release medium maintained at pH levels of 5.0 and 7.4. DHA concentrations in the collected samples were determined via UV spectroscopy, while Ca2+ levels were quantified using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). The cumulative release profile was subsequently calculated.

In vitro stability study

To assess the storage and in vivo stability of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles, both Ca/DHA@AFn and free DHA were dispersed in phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.2) to mimic various storage conditions in aqueous environments, maintaining samples at room temperature and 4 ℃, respectively. At predetermined intervals (1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 days), aliquots of each sample were withdrawn and transferred to test tubes. Subsequently, the absorbance of each sample was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, with three repetitions conducted for accuracy. The absorbance readings were then used to calculate the DHA content, which was repeated thrice. The average residual DHA content at each time point served as a metric for assessing the storage and short-term stability of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was employed to assess the particle size and surface charge (ζ potential) of Ca/DHA@AFn over 10 days. The suspension, prepared in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), was analyzed at room temperature with measurements conducted three times across 10 days.

Cell culture

To investigate the therapeutic effect of Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles, breast cancer 4T1, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells were selected as a cancer cell evaluation model in this study, and 4T1, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured according to the culture conditions recommended in the literature33. cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% neonatal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 5% CO2 incubation at 37 ℃ until the logarithmic growth period.

In vitro antitumor activity

The MTT assay evaluated the antitumor effects of DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn on cultured cells. First, a suspension of 4T1, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells in the exponential growth phase were inoculated at a 5 × 103 cells/mL density in a 96-well plate with 100 µL per well and incubated for 24 h34,35. The cells were then incubated with different concentrations of AFn, free DHA, and DHA@AFn for 24 h and 48 h consecutively, then 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well, and the incubation was continued for 4 h, after which the methyl filth formed in the cells was dissolved in DMSO. Finally, optical density (OD) values were measured at 570 nm using a multifunctional enzyme marker, and cell survival was calculated [cell survival (%) = OD treatment group/OD blank control group × 100%].

Cellular uptake experiments

The Ca/DHA@AFn surface underwent labeling with FAM dye, following the procedures outlined in our prior publications36. FAM was dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF), and an appropriate volume of the Ca/DHA@AFn solution was added. The reaction transpired at room temperature for 30 min, succeeded by stirring in darkness (100 rpm, 4 ℃, 12 h). Subsequently, the reaction mixture underwent purification using a polyacrylamide column (MWCO 100 kDa) to eliminate excess unreacted dye. The cellular uptake of Ca/DHA@AFn was evaluated and observed through fluorescence microscopy employing FAM as a fluorescent probe. 4T1 cells were cultured in 24-well plates (5 × 103 cells per well) and exposed to Ca/DHA@AFn (0.5 mg/mL) at 80–90% confluence for 1, 2, and 4 h. At predefined intervals, the cells underwent thrice washing with cold PBS and were documented using a fluorescence microscope.

Examination of cellular uptake mechanisms

Endocytosis inhibitors, namely chlorpromazine (8.5 µg/mL), genistein (56.75 µg/mL), and amiloride (133 µg/mL), were prepared to their respective concentrations using FBS-free medium37. 4T1 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until adherence was achieved. Subsequently, the culture medium was aspirated, and the various endocytosis inhibitors were added to the 6-well plates. Following a 30-minute incubation period at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2, the culture medium was removed, and FAM-CA/DHA@AFn (with a DHA concentration of 10 µg/mL) was introduced, followed by co-incubation for 2 h. The plates were then subjected to a 2-hour incubation with PBS stored at 37 ℃, after which the culture medium was aspirated, and FAM-CA/DHA@AFn was added. Subsequent washing steps were performed thrice using PBS buffer stored at 4 ℃. Qualitative analyses were conducted using an inverted fluorescence microscope, with the cell group pretreated with endocytosis inhibitors serving as the experimental group. In contrast, the group without pretreatment served as the control.

Determination of intracellular ROS and LPO

ROS are synergistically produced by Fe(II) and DHA and can activate anticancer activity. This experiment used the DCFH method to detect intracellular ROS levels. The steps were as follows30,36. Initially, 4T1 cells were seeded into six-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to DHA and Ca/DHA@AFn at an equivalent DHA concentration of 10 µg/mL for 12 h. Following the incubation, cells were subjected to two washes with PBS. Each well was treated with 1 mL of DCFH-DA (10 µg/mL in serum-free medium) for 30 min at 37 ℃. Subsequently, residual DCFH-DA was eliminated through PBS washing, and the intrinsic fluorescence within the cells was observed and documented using a fluorescence microscope.

The LPO levels induced by distinct nanoparticle formulations were assessed by fluorescence microscopy with the LPO-specific probe C11-BODIPY (excitation/emission wavelengths of 581/591 nm)27. Initially, 4T1 cells were seeded onto confocal dishes, followed by treatment with DHA, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn at a DHA concentration of 10 µg/mL. Untreated cells served as the experimental control. Following a 6-hour incubation period, cells underwent triple washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, each experimental group received C11-BODIPY probes at a concentration of 10 µM and was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequent fluorescence microscopy was employed to capture and analyze the obtained fluorescence images.

Antitumor effect in vivo

A subcutaneous tumor xenograft model was established in mice using 4T1 cells. Cells were prepared in a serum-free DMEM medium at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/100 µL. Using a 1 mL syringe with a 6-gauge needle, 100 µL of the cell suspension was subcutaneously injected into the flank of each mouse. On day 20 post-injection, all mice exhibited tumor volumes exceeding 100 mm3, and subsequent experimental treatments commenced. Mice assigned to treatment were randomly divided into three groups (n = 5). Treatments—saline, DHA, Ca@AFn, DHA@AFn, and Ca/DHA@AFn (at 10 mg/kg)—were administered via tail vein injection every 2 days for a total of six doses. The treatment start date was designated as day 0, with the study concluding on day 12. Tumor measurements, including longitudinal and transverse dimensions, were recorded prior to each administration to calculate tumor volume. Tumor growth curves were then generated post-study, using the formula V=(a×b2)/2, where a and b denote the longest and shortest tumor diameters, respectively.

To evaluate the chronic toxicity of Ca/DHA@AFn in treated mice, body weights of tumor-bearing mice were recorded prior to each treatment, and a weight change curve was generated at the study’s end. After 12 days of administration, major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys) and tumor tissues were excised and rinsed with cold PBS buffer. Excess moisture was removed using clean filter paper. The tissues were then preserved in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature. Following fixation, tissues were embedded in paraffin for sectioning and subsequent H&E staining. Pathological changes in the tumors and individual organs were examined using light microscopy.

Hemolysis test

An erythrocyte hemolysis test assessed the in vitro blood compatibility of the AFn vector and Ca/DHA@AFn for intravenous administration safety. Fresh mouse blood was obtained and treated with normal saline to create a 2% erythrocyte suspension. Various concentrations of AFn and Ca/DHA@AFn suspensions were mixed with equal amounts of red blood cell suspensions. The mixtures were cultured at 37 ℃ for 2 h, with distilled water as the positive control and normal saline as the negative control. After centrifugation of the supernatant at 2500 r/min for 10 min, the A value at 545 nm was measured. The hemolysis rate was calculated using the formula: hemolysis rate = (Asample -- Anc)/(Apc -- Anc), where Asample is the sample group A value, Anc is the negative control A value, and Apc is the positive control A value.

Biochemical index determination

To assess alterations in liver biochemical indices induced by the administration of Ca/DHA@AFn in mice, this study systematically examined specific liver parameters after Ca/DHA@AFn injection. The experimental design involved randomly assigning six mice into two distinct groups: the regular saline group and the Ca/DHA@AFn group. After a 48-hour post-injection period, 0.5 mL blood samples were retrieved from the retroorbital plexus of the mice. Subsequently, euthanasia was conducted via cervical dislocation, and the resulting serum was isolated for the analysis of relevant biochemical indices. The evaluation encompassed an in-depth assessment of both liver and kidney functions. The selected liver function indices comprised alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), albumin (ALB), and total protein (TP). Renal function indicators included creatinine (CREA), uric acid (UA), and urea (UREA).

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were determined using Microsoft Excel. SD analysis was conducted on triplicate samples—statistical analysis involved one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc comparison test. Significance was established at a confidence level of p < 0.05.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully developed Ca/DHA@AFn nanoparticles utilizing endogenous self-targeting apoferritin as a drug delivery vehicle. The nanoparticles were approximately 20 nm in size, exhibited a spherical morphology, and demonstrated uniform distribution. Cellular studies showed that Ca/DHA@AFn induced significantly greater cytotoxicity in 4T1 cells compared to DHA, Ca@AFn, and DHA@AFn alone, with efficient and time-dependent cellular uptake that promoted increased ROS production and subsequent cell death. In vivo antitumor evaluations in mice revealed that Ca/DHA@AFn achieved superior tumor inhibition with minimized systemic toxicity relative to single ferroptosis therapy. Collectively, this dual ferroptosis-calcicoptosis strategy presents a potent and promising therapeutic approach for breast cancer treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Correspondence Yan Li supported this work.

Author contributions

Shanshan Zhao, Peng Liu, and Yan Li conceived the experiments, discussed the results, and wrote the main manuscript text. Shanshan Zhao and Peng Liu conducted the experiments, and Shanshan Zhao analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All protocols and procedures related to animal sampling, care, and management were approved by the Jinzhou Medical University Animal Ethics Committee. All experiments and samplings were carried out using ethical and biosafety protocols approved by hospital guidelines. Besides, this study is reported by ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int. J. Cancer. 10.1002/ijc.33588 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi, Y., Lu, H. & Zhang, Y. Impact of HER2 status on clinicopathological characteristics and pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.206, 387–395. 10.1007/s10549-024-07317-7 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu, X. et al. Cancer nanomedicine in preoperative therapeutics: nanotechnology-enabled neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and phototherapy. Bioact Mater.24, 136–152. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.12.010 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gauci, M. L. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur. J. Cancer. 171, 203–231. 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.03.043 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su, M. H. et al. Comparing paclitaxel-platinum with ifosfamide-platinum as the front-line chemotherapy for patients with advanced-stage uterine carcinosarcoma. J. Chin. Med. Assoc.85, 204–211. 10.1097/jcma.0000000000000643 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo, S. et al. Cycloacceleration of ferroptosis and calcicoptosis for magnetic resonance imaging-guided colorectal cancer therapy. Nano Today. 47, 101663. 10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101663 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu, Y. et al. α-Fe(2)O(3) based nanotherapeutics for near-infrared/dihydroartemisinin dual-augmented chemodynamic antibacterial therapy. Acta Biomater.150, 367–379. 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.07.047 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, B. et al. Co-delivery of paclitaxel (PTX) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) by targeting lipid nanoemulsions for cancer therapy. Drug Deliv. 29, 75–88. 10.1080/10717544.2021.2018523 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren, G. et al. Construction of reduction-sensitive heterodimer prodrugs of doxorubicin and dihydroartemisinin self-assembled nanoparticles with antitumor activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 217, 112614. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112614 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro, L., Blázquez, M. L., González, F. G. & Ballester, A. Mechanism and applications of metal nanoparticles prepared by bio-mediated process. Reviews Adv. Sci. Eng.3, 199–216 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neri, D. & Supuran, C. T. Interfering with pH regulation in tumors as a therapeutic strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 10, 767–777 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patergnani, S. et al. Various aspects of calcium signaling in the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, cell proliferation, and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 8323 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu, H. et al. New anti-cancer explorations based on metal ions. J. Nanobiotechnol.20, 457 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, C., Liu, Q., Huang, X. & Zhuang, J. Ferritin nanocages: a versatile platform for nanozyme design. J. Mater. Chem. B. 11, 4153–4170. 10.1039/d3tb00192j (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang, B., Fang, L., Wu, K., Yan, X. & Fan, K. Ferritins as natural and artificial nanozymes for theranostics. Theranostics10, 687–706. 10.7150/thno.39827 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truffi, M. et al. Ferritin nanocages: a biological platform for drug delivery, imaging and theranostics in cancer. Pharmacol. Res.107, 57–65. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.03.002 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, N. K. et al. Ferritin nanocage with intrinsically disordered proteins and affibody: a platform for tumor targeting with extended pharmacokinetics. J. Control Release. 267, 172–180. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.014 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji, P. et al. Selective delivery of curcumin to breast cancer cells by self-targeting apoferritin nanocages with pH-responsive and low toxicity. Drug Deliv. 29, 986–996. 10.1080/10717544.2022.2056662 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai, X. et al. Dihydroartemisinin: a potential natural anticancer drug. Int. J. Biol. Sci.17, 603–622. 10.7150/ijbs.50364 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong, K. H., Yang, D., Chen, S., He, C. & Chen, M. Development of nanoscale drug delivery systems of dihydroartemisinin for cancer therapy: a review. Asian J. Pharm. Sci.17, 475–490. 10.1016/j.ajps.2022.04.005 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan, Y. et al. Metal-organic framework-encapsulated dihydroartemisinin nanoparticles induces apoptotic cell death in ovarian cancer by blocking ROMO1-mediated ROS production. J. Nanobiotechnol.21, 204. 10.1186/s12951-023-01959-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, D. et al. Fe-MnO(2) nanosheets loading dihydroartemisinin for ferroptosis and immunotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114431. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114431 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ning, C. et al. Co-encapsulation of hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs into human H chain ferritin Nanocarrier enhances Antitumor Efficacy. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.9, 2572–2583. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.3c00218 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, M. et al. Enhancing Tumor Immunotherapy by Multivalent Anti-PD-L1 Nanobody assembled via Ferritin Nanocage. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). e2308248 10.1002/advs.202308248 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Zhang, R., Qin, X., Kong, F., Chen, P. & Pan, G. Improving cellular uptake of therapeutic entities through interaction with components of cell membrane. Drug Deliv. 26, 328–342. 10.1080/10717544.2019.1582730 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, Y., Kohler, N. & Zhang, M. Surface modification of superparamagnetic magnetite nanoparticles and their intracellular uptake. Biomaterials23, 1553–1561. 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00267-8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, J. et al. Ferroptosis-enhanced chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer with magnetic composite nanoparticles. Biomaterials303, 122395. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122395 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Neill, P. M. et al. Synthesis, antimalarial activity, biomimetic iron(II) chemistry, and in vivo metabolism of novel, potent C-10-phenoxy derivatives of dihydroartemisinin. J. Med. Chem.44, 58–68. 10.1021/jm000987f (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, B., Tang, G., He, J., Yan, X. & Fan, K. Ferritin nanocage: a promising and designable multi-module platform for constructing dynamic nanoassembly-based drug nanocarrier. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev.176, 113892. 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113892 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji, P. et al. Hyaluronic acid-coated metal-organic frameworks benefit the ROS-mediated apoptosis and amplified anticancer activity of artesunate. J. Drug Target.28, 1096–1109. 10.1080/1061186x.2020.1781136 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia, X. et al. PM1-loaded recombinant human H-ferritin nanocages: a novel pH-responsive sensing platform for the identification of cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.199, 223–233. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.12.068 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang, H. et al. Ca(2+) participating self-assembly of an apoferritin nanostructure for nucleic acid drug delivery. Nanoscale12, 7347–7357. 10.1039/d0nr00547a (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao, X. et al. 5-Boronopicolinic acid-functionalized polymeric nanoparticles for targeting drug delivery and enhanced tumor therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl.119, 111553. 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111553 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao, Y., Hu, L., Liu, Y., Xu, X. & Wu, C. Targeted delivery of paclitaxel in liver cancer using hyaluronic acid functionalized mesoporous hollow alumina nanoparticles. Biomed. Res. Int.2019, 2928507 10.1155/2019/2928507 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Tong, X. et al. Targeting CSF1R in myeloid-derived suppressor cells: insights into its immunomodulatory functions in colorectal cancer and therapeutic implications. J. Nanobiotechnol.22, 409. 10.1186/s12951-024-02584-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji, P. et al. ROS-mediated apoptosis and anticancer effect achieved by artesunate and auxiliary Fe(II) released from ferriferous oxide-containing recombinant apoferritin. Adv. Healthc. Mater.8, e1900911. 10.1002/adhm.201900911 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui, P. F. et al. Dex-Aco coating simultaneously increase the biocompatibility and transfection efficiency of cationic polymeric gene vectors. J. Control Release. 303, 253–262. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.04.035 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.