Abstract

The increasing global emphasis on sustainable energy alternatives, driven by concerns about climate change, has resulted in a deeper examination of hydrogen as a viable and ecologically safe energy carrier. The review paper analyzes the recent advancements achieved in materials used for storing hydrogen in solid-state, focusing particularly on the improvements made in both physical and chemical storage techniques. Metal–organic frameworks and covalent-organic frameworks are characterized by their porous structures and large surface areas, making them appropriate for physical adsorption. Additionally, the conversation centers on metal hydrides and complex hydrides because of their ability to form chemical bonds (absorption) with hydrogen, leading to substantial storage capacities. The combination of materials that adsorb and absorb hydrogen could enhance the overall efficiency. Moreover, the review discusses recent research, analyzes key factors that influence performance, and discusses the difficulties and strategies for enhancing material efficiency and cost-effectiveness. The provided observations emphasize the critical significance of improved materials in facilitating the transition towards a hydrogen-based economy. Furthermore, it is crucial to highlight the necessity for additional study and development in this vital field.

Keywords: Hydrogen storage, Solid-state materials, Physical adsorption, Chemical absorption

Introduction

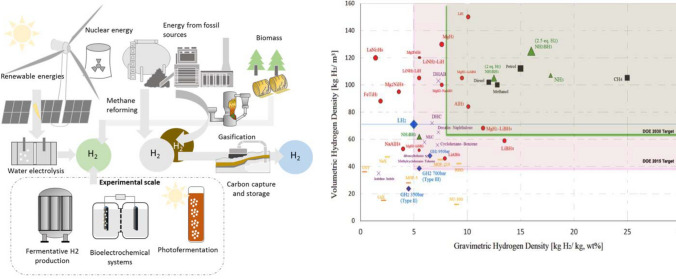

Currently, a green energy transition is more significant than ever in global energy forecasts, which is driven by concerns about climate change [1]. Hydrogen energy is known as a viable option due to its efficient energy exchange, zero-emission generation from water, abundance, versatile storage options, minimal loss during transportation, and environmental friendliness [2]. Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of technologies available for hydrogen production, including methane steam reforming, gasification, water electrolysis, biological processes, and others.

Fig. 1.

Schematization of technologies available for hydrogen production (left) (Data source: Ref. [3]), DOE target areas for hydrogen storage technologies: volumetric and gravimetric density specifications (Data source: Ref. [4])

It is significant to note that the increased focus on solid-state hydrogen storage, as opposed to conventional gaseous and liquid storage methods [5], is due to its superior volumetric capacity (100–130 g/L), good safety, a simple system (gas cylinder- and compressor-free solution), and good economy [6–8]. While the gravimetric capacity of solid-state hydrogen storage is low, limiting the amount of hydrogen that can be stored per unit weight of the storage material [6], solid-state hydrogen storage materials are more suitable for stationary applications (such as hydrogen refueling stations and backup power supplies), where weight is not a critical factor, rather than for on-board applications (such as vehicles) [8, 9]. In recent years, to tackle this problem, the leading vehicle manufacturers (Honda, Toyota, GM) have integrated hydrogen storage devices of cylindrical configuration (~ 10–100 L) to optimize the utilization of constrained vehicle volumes.

It is worth mentioning that the United States and China have been the leading countries in terms of the number of publications in the hydrogen storage field from 2000 to 2021 [10]. Additionally, China is known as one of the frontrunners in the sale of fuel cell vehicles between 2016 and 2023, accounting for half of the total worldwide sales [8]. However, the high cost of material preparation can hinder mass production and increase manufacturing expenses. Consequently, significant efforts are dedicated to enhancing the storage properties and economic production processes.

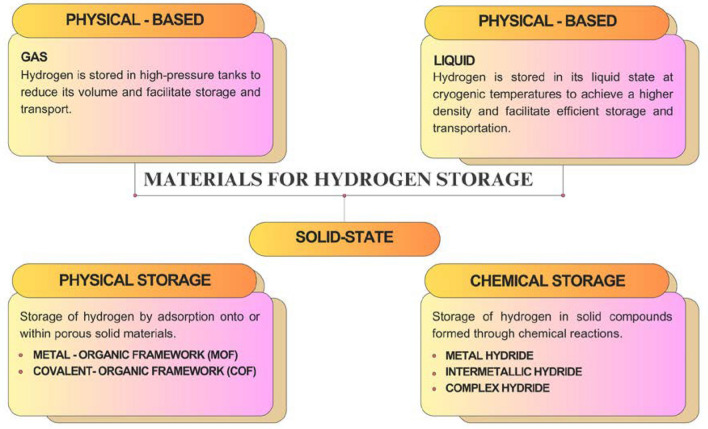

Nowadays under investigation are metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), metal-doped metal organic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks (COFs), clathrates, nanostructured carbon materials, metal-doped carbon nanotubes, and complex chemical hydrides as solid-state hydrogen storage materials [11]. As shown in Fig. 2, this review paper focuses on MOFs and COFs as materials with a physical hydrogen storage mechanism, as well as metal-, intermetallic-, and complex-hydrides as materials with chemical hydrogen storage.

Fig. 2.

Classification of materials for hydrogen storage presented in this review article

The novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive review and analysis of recent advancements in both physical and chemical solid-state hydrogen storage materials, highlighting key performance factors and strategies for improving efficiency and cost-effectiveness to support a hydrogen-based economy.

Solid-state physical storage materials

Regarding research on solid-state physical storage materials in the early 2020s, several examples are presented below. Yujue Wang revealed that zeolites, activated carbons, carbon nanotubes, and metal–organic frameworks are effective materials for hydrogen storage among other materials [13]. For example, MOFs are the most prevailed materials used for adsorption due to its hydrophobic properties, strong mechanical and thermal resistance, chemical inertness, and high physical adsorption capacity. According to Wang, while zeolites can adsorb gas molecules selectively based on their size, the performance of activated carbon and carbon nanotubes could be improved by doping with other elements to increase contact with gas molecules. Erdogan et al. studied zeolite/activated carbon (ZAC), zeolite/MWCNT, and zeolite/graphene composite (ZGC) and found that ZAC has higher hydrogen capacity at 1.3 wt% at 77 K and ambient pressure compared to pure activated carbon and zeolites [14]. The flexibility of metal–organic frameworks and porous organic cage compounds has also been reported by D. Broom et al. for enhanced hydrogen storage [15]. It was found that with an increase in BET specific surface area, hydrogen uptake increases linearly. Sébastien Rochat et al. developed polymer decorations allowing 6.7 wt% of hydrogen to be stored in microporous composites at a temperature of 77.4 K [16]. Within that same context, Xiaohong Chen et al. introduced a novel approach where carbon nanofibers are co-doped by fluorine co-deposition with lithium precursor to fabricate organized structures especially tailored for such purposes [17]. According to the results, Li–F–PCNFs demonstrated a hydrogen capacity of, up to 2.4 wt% at 0 °C and 10 MPa, which shows better performance—over 24 times more than that of pure porous carbon nanofibers. It was found that NPF-200, a highly porous material, holds promise for hydrogen adsorption at high volumes [18], while Arslan Munir et al. noted that copper-based metal–organic frameworks and carbon-based composites have improved crystallinity and a larger surface area along with a hydrogen uptake of 6.12 wt% at − 40 °C [19].

Mechanisms of hydrogen adsorption on solid-state physical storage materials

Physical adsorption occurs when gas molecules enrichment happens between solid and gas phases [20]. This phenomenon is also described as van der Waals interactions with short-range repulsive interactions between phases. According to Panella, the interaction starts from the long-range forces applied to molecules by making their charge distribution fluctuate and increasing induced dipoles. However, gas molecules located nearby tend to have more intense repulsion due to the overlapping of electron clouds [20].

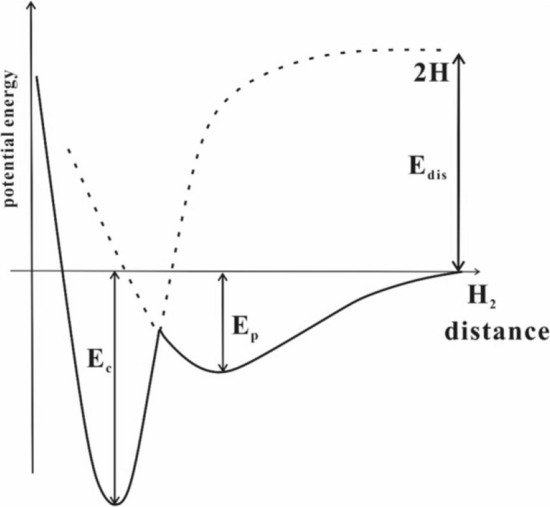

The interaction of adsorbent with gas molecules could be explained using the Lennard–Jones potential. Based on this concept, there is no interaction in the case of two contiguous particles in the limit of infinite distance. However, they tend to repel each other at shorter distances, and their attraction dominates at moderate distances. Figure 3 shows correlation between potential energy and the distance from the surface of the adsorbent for chemisorbed (Ec) and physisorbed (Ep) hydrogen. It is important to understand that there is no energy barrier in physical adsorption to stop gas molecules from reaching the surface. As a result, in the absence of diffusional obstacles, physical adsorption is characterized by quick kinetics and it does not require activation. It is known that the range of molecular hydrogen adsorption is 1–10 kJ/mol, which is around ten times smaller than that of chemisorption [21].

Fig. 3.

Relationship between potential energy and distance (Data source: Ref. [20])

To determine the intermolecular potential between hydrogen atoms and atoms on the surface, the following equation is used:

where ε is the calculated adsorption energy, r is the distance between the hydrogen atom (molecule) and surface atoms, and rm is the interaction between hydrogen atoms or molecules and surface atoms when the physical or chemical adsorption occurs. This equation quantifies interaction strength and provides insights into adsorption efficiency by modeling the relationship between distance and potential energy.

Thus, The Lennard–Jones potential is crucial for understanding the interactions between hydrogen molecules and the solid-state hydrogen storage materials, helping to determine sorption efficiency by capturing both attractive and repulsive forces.

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)

Metal–organic frameworks are made of polynuclear clusters namely secondary building units (SBUs) which contain the metal ions at the nodes and organic linkers as the binding groups [22]. The diversity in the MOF structures can be accounted for by adjusting their geometry and connectivity. In the early ‘90’s it was reported that long linkers create isostructural analogs of the same type of metal–organic frameworks that are interpenetrated to a varied extent by altering the pore sizes of the frameworks [23].

The charge on the linker facilitated the development of neutral frameworks and enhanced bond strength while chelation of metal ions supplied rigidity and directionality to create polynuclear clusters leading to many advantages for achieving stronger structures using SBUs [12].

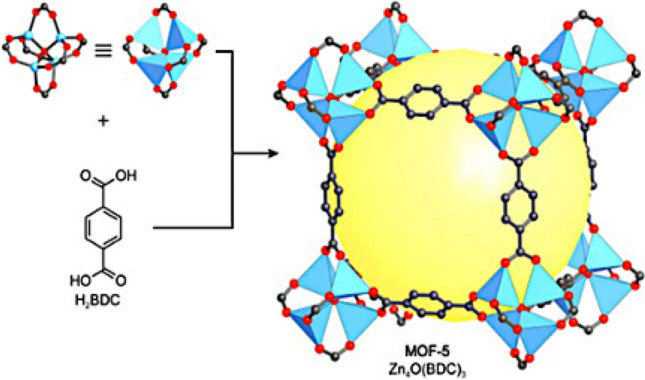

MOF-2 was synthesized using slow vapor diffusion method of the mixture of trimethylamine/toluene into a DMF/toluene solution of Zn(NO3)2⋅6H2O and benzenedicarboxylic acid (H2BDC) [24]. Rather than single metal nodes, the dimeric Zn2(–COO)4 paddle wheel SBUs build the layered structure of MOF-2, which is linked by BDC struts to form a square grid (sql). This kind of structure of SBUs increased their stability which made it possible to remove all solvents without destroying the main body of the compound. Later on, Li et al. introduced MOF-5 with the SBU node as [Zn4O(BDC)3](DMF)x [25]. The structure is given in Fig. 4, which is synthesized using terephtalic acid as organic linker and zinc based salt to buid the SBU units.

Fig. 4.

Structure of MOF-5 (Data source: Ref. [12])

Approximately 61% of the unit cell is represented by these substantial voids that have been filled with solvent (DMF) molecules from the synthesis material. As it is obvious from Fig. 4, one of the more striking features of the MOF-5 structure is the lack of walls surrounding the pores. This exceptionally empty build allows guest molecules to pass through without obstructing their path since there are no walls present in the pores. When diffusion occurs in these materials, there is always the possibility of having narrow or blocked spaces because zeolites have a framework made up of walls. According to Li et al., sorption isothems at 78 K and following the Dubinin-Raduskhvich equation showed metal–organic frameworks having higher pore volume (0.54–0.61 cm3 cm−3) than zeolites (up to 0.47 cm3 cm−3) [25]. Further studies showed that MOFs are sensible to humid air and moist solvents which affect their decomposition [26]. The reversibility of nitrogen adsorption at 77 K for MOF-2 was first introduced, and since then the gas adsorption in MOFs has been studied according to the above-mentioned example [12].

Covalent-organic frameworks (COFs)

Covalent-organic frameworks can be thought of as a type of crystalline porous polymer that integrates atomic-level organic components in a precise manner for gas storage, catalysis, and optoelectronic applications [27]. They are designed with specific geometrical shapes and sizes making it possible to provide well-defined structures which contain special molecular spaces leading to completely different characteristics and applications [28]. According to Jiang et al. carbon-based configurations are formed by using dynamic covalent bonds and create an architecture with well-defined pores and voids [29]. These are carbon-containing materials, which possess a network of sp2-hybridized atoms that are connected by covalent bonds into ordered skeletons in three dimensions. By using topology-guided polymer chain development, the building blocks predict the COFs structures to create polymers with both 2D and 3D proportions. Some applications thus are inclined towards gas storage or separation among other areas that demand for such materials [30].

Since the ultimate crystallinity and porosity of COFs are determined by their topological design, it is important to plan them before synthesis begins. COFs are adjustable polymers. Monomers construct their structural foundation. The most popular technique for creating 2D and 3D networks via chain propagation is step-growth polymerization. In the COFs, several interactions could take place. For instance, on a plane where layers have developed in 2D materials, there is a covalent link. Non-covalent interaction, aromatics, π-staking, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waal’s forces prohibit these layers from isolating, aggregating, and forming layered material.

Jiang et al. have reported several conceptual ideas for designing COFs [31]. It was found at the beginning one knot and one linker is employed to obtain hexagonal, tetragonal, and trigonal topology. However, COFs can be designed using one knot and two or three linkers. Multicomponent synthesis results in irregularly shaped but ordered pores. Moreover, the use of several components enables the formation of intricate frameworks where distinct electrical interactions are triggered by the existence of adjacent edges. Overall, there are four main topologies of COFs, namely hexagonal, rhombic, tetragonal, and trigonal.

In the last years MOFs and COFs have drawn much attention as hydrogen storage materials due to their porous structure, large free volume, and high available surface area [32–34]. Nonetheless, using MOFs and COFs is nearly impossible in the ambient conditions to store hydrogen. One of the main reasons is the van der Waals interaction between hydrogen and porous materials which have a binding energy range of 2.2–5.2 kJ/mol [35, 36].

Solid-state chemical storage materials

Metal hydride

Metal hydrides (MHx), known as hydrogen ‘sponges’, have garnered significant attention as potential candidates for hydrogen storage since the 1970s [37–51]. Most elemental metals will form metal hydrides in a simple and direct (exothermic) reaction when the pressure level is above the equilibrium pressure [40]:

| 1 |

where M is hydride forming metal; Q is heat released during the hydride formation or absorbed during its decomposition.

A reversible (endothermic) reaction can occur when the pressure is below the equilibrium pressure. Besides metals, alloys and intermetallic compounds can also react reversibly with hydrogen under moderate pressure and low temperatures to form hydrides [41, 47]. The application of low temperature is explained by Le Chatelier’s principle, which states that lowering the temperature favors the exothermic formation of metal hydrides, enhancing hydrogen storage.

Hydrogen can be stored in metal hydrides at high density and low pressure through absorption, making this method safer than other storage techniques [47, 52]. Apart from safety, metal hydrides are known as the most promising hydrogen storage materials due to their high hydrogen storage capacity, good cyclic stability, and fast reaction kinetics [8, 53, 54]. The utilization of metal hydrides for hydrogen storage can be categorized into on-board (vehicle, mobile) and stationary applications (hydrogen refueling stations and backup power supplies) [8, 9]. For on-board applications, both gravimetric and volumetric capacities are prioritized to minimize weight and space, whereas for stationary applications, volumetric capacity is prioritized to maximize storage within limited space.

Successful selection of metal hydrides for these and other applications requires knowledge of many engineering properties. This section will delve into the fundamental principles underlying hydrogen absorption and desorption by metal hydrides, their classification, key properties affecting storage performance, recent advancements in material development, and the persistent challenges alongside strategies aimed at enhancing storage capacity and kinetics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Properties of hydrogen storage alloys (Data source: Ref. [4]) (N/M = Not Mentioned)

| Formula | Gravimetric capacity (wt%) | Volumetric capacity(g/L) | Desorption temperature (℃) |

Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 7.7 | 150 | 910 | Laboratory |

| AlH3 | 10.1 | 84 | 99 (high pressure is required 2.5 GPa) | Laboratory |

| MgH2 | 7.69 | 84 | 400 | Stationary hydrogen storage, High temperature heat storage |

| FeTiH2 | 1.9 | 88 | 40 | On-board applications |

| LaNi5H6 | 1.4 | 120 | 106 | On-board applications |

| NaAlH4 | 3.99 | 53 | 150–200 | N/M |

| Mg2FeH6 | 5.5 | 120 | 350 | N/M |

| Mg2NiH4 | 3.6 | 95 | 290 | N/M |

Mechanisms of hydrogen absorption on solid-state chemical storage materials

Understanding the mechanisms of metal hydride formation and decomposition is crucial for optimization because it enables the design of more efficient, safe, and cost-effective hydrogen storage systems by tailoring conditions and materials to achieve the best performance. There are two mechanisms of formation and decomposition of the metal hydrides: gas phase (Eq. 1) and electrochemical (Eq. 2) [55]. Mykhaylo V Lototskyy et al. noted that the principal difference between the two mechanisms lies in the hydrogen source: in the first mechanism, atomic hydrogen is generated by splitting molecular H₂, whereas in the second mechanism, it is derived from water molecules. The distinction between these mechanisms is significant since it directly impacts the efficiency and practicality of metal hydrides for different applications. For instance, the gas phase mechanism is used for high-pressure systems, while the electrochemical approach is relevant for integrating hydrogen production with renewable energy sources.

| 2 |

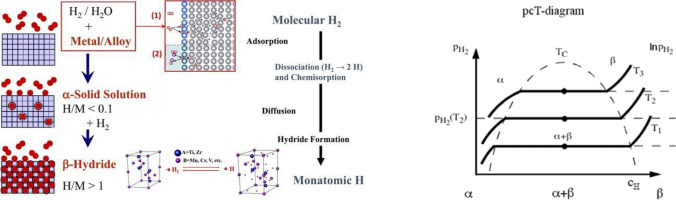

Figure 5 (left) shows the reaction of hydrogen penetration into a hydride-forming metal. Considering the gas phase mechanism, the reaction begins with the dissociative chemisorption of hydrogen molecules on the metal’s surface [55]. Vinod Kumar Sharma noted that as concentration along with pressure increases, dissociation of hydrogen molecules occurs due to the increase in vibrational gas energy [57]. This is followed by the diffusion of hydrogen atoms into the bulk through the interstitial sites in the metal matrix. The α-phase (H/M < 0.1), known as the interstitial solid solution, is the result of hydrogen in the host metal. Subsequently, the transition from α-phase to β-phase (H/M > 1; hydride formation), occurs due to the increase in hydrogen concentration. It is significant to note the accommodation of hydrogen atoms leads to the expansion of the metal sublattice without changing its original symmetry [55].

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of hydride formation process (left) (Data source: Ref. [55]) and pressure-composition-isotherms of a typical hydrogen absorption or desorption process and corresponding van’t Hoff plot (right) (Data source: Ref. [56])

The most important parameters for gas phase applications of metal hydrides are the operating temperature and hydrogen pressure, which are defined by the thermodynamic properties of the hydrides [55]. The thermodynamics of Eq. (1) are governed by the relationship among hydrogen equilibrium pressure (Peq), hydrogen concentration in the solid (CH = H/M), and temperature (T), as depicted by pressure-composition isotherms (PCIs) in Fig. 5. Having deeply considered the PCI isotherm, the plateau at each temperature (T1-T3) represents the amount of hydrogen that can be reversibly stored [56]. There is an indirect relationship between temperature and the length of the plateau, i.e., with an increase in temperature, the length of the plateau decreases.

As shown in Fig. 5 (right), the equilibrium plateau pressure is highly dependent on temperature and is connected to the absolute values of enthalpy and entropy changes, ΔH and ΔS, respectively. Plotting the logarithm of the plateau pressure as a function of 1000/T, the slope will give the enthalpy of the reaction, and the intercept will give the entropy of the reaction. The enthalpy reflects the bond stability between metal and hydrogen atoms; stronger bonds result in higher enthalpy changes. While entropy is related to change from hydrogen molecules to hydrogen atoms in the solid metal hydrides. For metal hydrides to be practical for hydrogen storage, they should operate within a pressure range of 1 to 10 bar and a temperature range of − 20 to 100 °C. These conditions correspond to an enthalpy change (energy change during hydrogen absorption/release) of 28 to 48 kJ/mole of hydrogen. Hence, the gravimetric hydrogen storage capacity of most metal hydrides is less than 2 wt% [57].

Classification of metal hydrides

Metal hydrides are formed from transition metals or alloys; hence, they exhibit metallic characteristic properties: high thermal and electrical conductivity, hardness, and luster [61]. Seven classes of metal alloys with different crystal structures have been studied for hydrogen storage over the past three decades, including AB5, AB2, AB3, A2B7, A6B23, AB, and A2B [57]. These alloys consist of transition metals A (such as Ti, Zr, Ca, Mg, and V) capable of creating hydrides, and non-hydride-forming metals B (such as Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, and Cu) [58–60]. Element A refers to rare earth elements with a high affinity for hydrogen, whereas element B is responsible for controlling the absorption and dehydrogenation cycle [59]; A usually forms stable hydrides, while B decreases stability [57].

Key properties influencing hydrogen storage performance

Ease of activation, heat transfer rate, kinetics of hydriding and dehydriding, resistance to gaseous impurities, safety, weight, and cost are the main properties of metal hydride storage [61].

Ease of Activation: Activation consists of two steps: changes in surface structure/barriers and internal particle cracking. The surface/barrier changes involve dissociation, catalytic species, and oxide layers. The second step involves the self-pulverization of large metal particles into powder due to a combination of changes in hydriding volume and the brittle characteristics of hydriding alloys, especially when they contain some hydrogen.

Kinetics of Hydriding and Dehydriding: To keep hydride weight and volume small, short hydrogen loading/unloading cycle times are crucial. The rate-limiting factor is poor heat transfer due to the low conductivity of the finely divided powder and poor heat transfer between the particles and the container wall. Improving both heat transfer and hydrogen flow is essential for efficient hydrogen hydriding and dehydriding processes. Kinetics are typically measured by hydrogen concentration over time. Several factors could influence these measurements: sample quantity, shape, porosity, thermal conductivity, particle size, hydrogen overpressure, and gas purity.

Resistance to Gaseous Impurities: Alloy-impurity concentrations can cause various types of damage and performance degradation: (1) poisoning, with rapid capacity loss but stable initial kinetics; (2) retardation, with quick kinetic loss but stable ultimate capacity; (3) reaction, involving slow corrosion of the alloy; and (4) innocuous effects, with no surface damage but potential pseudo-kinetic decreases due to inert gas blanketing. Poisoning and retardation damages are typically fixable, whereas reaction damages are generally permanent.

Challenges in metal hydride hydrogen storage

Absorption, on the other hand, involves storing hydrogen within the lattice structures of solid materials. Metal hydrides are a prominent example, where metals like magnesium or palladium absorb hydrogen, forming metal hydrides. This method of storage is highly efficient and can store hydrogen at much lower pressures compared to gaseous storage. Additionally, these materials can release hydrogen on demand, making them very convenient for various applications.

Storing hydrogen in materials is particularly important because it can potentially address some of the major challenges associated with hydrogen storage. By utilizing adsorption and absorption techniques, it is possible to achieve higher storage densities, improve safety by avoiding the high pressures and extreme temperatures required for gas and liquid storage, and facilitate easier transportation and handling.

Furthermore, these materials-based storage solutions open new possibilities for decentralized and portable hydrogen storage systems. They can be integrated into vehicles, portable power systems, and remote energy applications, significantly broadening the scope and utility of hydrogen as a clean energy carrier. These innovative storage techniques offer enhanced safety, efficiency, and practicality, paving the way for the broader adoption of hydrogen technologies in the quest for sustainable and clean energy solutions.

Hydrogen storage is a critical component of hydrogen-based energy systems. Metal hydrides are considered promising candidates for hydrogen storage due to their ability to reversibly absorb and release hydrogen. The key criteria for selecting suitable metal hydrides include high hydrogen storage capacity (weight fraction of H), low decomposition temperature, and favorable thermodynamic properties. Metal hydrides are evaluated based on the provided criteria: hydrogen content higher than 4.5 wt% and lower decomposition temperatures are preferred for practical hydrogen storage applications.

Complex hydrides

A metallic cation and an anionic group make up complex metal hydrides. These two parts work together to make compounds like alanates and borohydrides. These compounds can form chemical bonds with four hydrogen atoms via alkali metal [62]. Although complex hydrides need low dehydrogenation pressure and temperature, they have a large hydrogen storage capacity, which makes them ideal for hydrogen storage applications [63]. Nevertheless, most complex hydrides exhibit elevated thermodynamic stability and sluggish kinetics [64]. Furthermore, the performance and durability of these materials after repeated cycles, the challenges in handling them, and their very stable breakdown products are significant factors that restrict their use for recharging motor vehicles with hydrogen (Table 2). Therefore, thermodynamic destabilization, nanoconfinement, and catalysis could be employed to improve the properties of complex hydrides [47].

Table 2.

Properties of hydrogen storage complex hydrides (Data source: Ref. [65])

| Complex hydrides | Molar mass (g/mol) | Volumetric mass density (g/ml) | Gravimetric hydrogen density (wt% H2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanates | LiAlH4 | 37.95 | 0.92 | 10.6 |

| Li3AlH6 | 53.85 | 1.02 | 11.2 | |

| NaAlH4 | 54 | 1.28 | 7.3 | |

| Na3AlH6 | 102 | 1.45 | 5.9 | |

| Borohydrides | LiBH4 | 21.78 | 0.66 | 18.4 |

| NaBH4 | 37.83 | 1.07 | 10.8 | |

Alanates

Alanates are compounds with the chemical formula MAlH4, where M represents either alkali or alkaline earth metals. Researchers have extensively studied aluminum-based compounds for hydrogen storage due to their large storage capabilities [66, 67].

Sodium alanate (NaAlH4) is one type of cost-effective alanate with a theoretical hydrogen capacity of almost 7.4%. Additionally, it exhibits favorable operating pressures and temperatures [68]. Nevertheless, it exhibits sluggish reaction rates, has a limited ability to reverse the reaction, and requires harsh dehydrogenation conditions [69]. It is also subjected to a three-step breakdown process [62]:

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

The addition of a catalyst can significantly enhance thermodynamic characteristics. However, the robust covalent connection between aluminum and hydrogen makes it challenging to release and absorb hydrogen.

Synthesis of alanates. Metals or metallic hydrides commonly produce alanates by reacting with Al and H2 in the presence of a catalyst (usually titanium compounds) and organic solvents [70, 71]. The reactions involved in the formation and transformation of alanates can be described by the following equations:

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

This technique necessitates the application of hydrogen pressure ranging from moderate to high (100–150 bar) and moderate temperatures (120–150 °C). However, LiAlH4 needs a higher pressure (350 bar) [70]. This process is extremely hazardous because it involves an explosive combination of organic solvents, metal hydride, and Al with oxygen and humidity. The materials generated require subsequent filtration and dehydration processes. Researchers commonly store and sell the alanates in a solution of tetrahydrofuran (THF).

Borohydrides

Alkali-transition metal borohydrides, with the chemical formula MBH4, are hydrides that are stable and have a high capacity for storing hydrogen, up to 9.6 wt% [72]. They also have tunable properties [73, 74]. Nevertheless, these compounds have certain disadvantages, including their elevated thermodynamic stability, sluggish kinetics, and the generation of borane, an unwanted volatile by-product [75].

To enhance their properties, one can employ destabilization or doping procedures. Doping them with certain metals can lead to the formation of bimetallic borohydrides of the form MLi(BH4)m using metal/metalloid elements [76]. Additionally, this strategy seeks to produce MgH2-type hydrides and LiNH2-type amides, which can potentially improve the hydrogenation and dehydrogenation processes under milder conditions [77]. The use of catalysts such as FeCl2 and TiCl3, as well as metal oxides like TiO2 and SiO2, facilitate the re/de-hydrogenation reactions, making them more efficient and effective under less extreme conditions [78]. Another strategy to enhance the kinetics of the hydrogenation and dehydrogenation reactions involves reducing the particle size of LiBH4 to the nanoscale. This can be achieved by incorporating materials such as activated carbon and silica (SBA-15) [79, 80].

Sodium borohydride (NaBH4) possesses significant theoretical hydrogen storage capabilities of approximately 10.7 weight percent and 5.72 kg of H2 per 100 L [58]. Hydrogen is liberated through hydrolysis, a process that is irreversible and consists of two steps. The Eq. 9 demonstrates this two-step decomposition of NaBH₄, showing the different stages of hydrogen release and formation of intermediate form such as NaH. Furthermore, the thermal degradation process gives rise to the formation of poisonous and harmful chemicals, particularly for FCs [69].

| 9 |

Solid-state composite storage materials

Nanoconfinement is one of the key methods for designing hybrid materials, including nanoencapsulation and nanoscaffolding. These methods are significant for fabricating advanced composite materials due to optimized hydrogen storage capacity, enhanced kinetics, and improved the overall functionality of storage systems.

Nanoencapsulation

The process of integrating a substance at the nanoscale into a secondary material, commonly referred to as the matrix or shell, is known as nanoencapsulation. Materials that fall into this category include graphene [81, 82], reduced graphene oxide [83], and polymers [84, 85]. Encapsulation can occur in core–shell nanoparticles [86] as well as in multilayered thin films [87]. This procedure involves using a preconstructed nanostructure that acts as a barrier to inhibit particle or grain growth. Furthermore, it provides protection against disruptive situations that could lead to clumping or reduction to powder during the cycling process.

Hydride encapsulation refers to the process of enclosing hydride compounds, such as metal hydrides, within tiny particles or capsules at the nanoscale. This technology has a wide range of applications, particularly in hydrogen storage and related fields. The research in hydride encapsulation aims to develop effective and scalable techniques for producing nanoparticles or capsules that contain hydrides. It also entails studying the characteristics of these particles and evaluating their effectiveness in hydrogen storage and other related applications [88]. This region has a lot of potential for expanding hydrogen-based technology and addressing challenges related to renewable energy storage and delivery. When considering hydrogen storage, the process of enclosing metal hydrides [89] within nanoparticles or nanocapsules can provide various benefits:

Improved Stability: Metal hydrides are vulnerable to the effects of air, moisture, and temperature, which can lead to degradation and reduced efficiency. Encapsulation acts as a protective measure against external factors’ harmful impacts, thereby improving the stability and durability of the hydride material [90].

Enhanced Reactivity: Nanoencapsulation can increase the surface area of the hydride material, thereby promoting faster hydrogen absorption and release kinetics. This has the capacity to improve the overall effectiveness of hydrogen storage systems [91, 92].

Controlled Release: By encapsulating metal hydrides, scientists may restrict the release of hydrogen, enabling precise and targeted delivery in various applications, such as hydrogen fuel cells or hydrogen-powered cars.

Safety: Encapsulation can improve the safety of handling metal hydrides by reducing the chances of unexpected reactions or hydrogen release [93].

Several noteworthy studies which deserve attention. The study of Zhu et al. [94] introduces a new approach called microencapsulated nanoconfinement to achieve localized synthesis of nanoMHs. These nano-MHs exhibit exceptional structural stability and excellent desorption kinetics. A simple gas–solid interaction forms Mg2NiH4 single crystal nanoparticles (NPs) with uniform size on graphene sheets (GS). The approximately 3 nm thick MgO coating layer effectively separates the nanoparticles from each other, keeping them from sticking together during the cycles of hydrogen absorption and desorption. This results in exceptional thermal and mechanical stability. Furthermore, the MgO layer exhibits exceptional gas-selective permeability, effectively inhibiting further oxidation of Mg2NiH4 while remaining accessible for hydrogen absorption and desorption. Bogdanovic et al. began doping complex hydrides [95] in 1997 to enhance storage capacities. These days, it’s possible to modify not just the encapsulated element but also the host. For instance, Shin Young Kang et al. [96] used the well-known material graphene doped by heteroatoms as 2D encapsulation media for Mg-based hydrogen storage, suggesting that the use of heteroatom-doped graphene oxide derivatives as a nanoscale encapsulation medium can alter the rate of hydrogen storage in Mg-based systems. This suggests that the encapsulation interface of Mg-based hydrogen storage can be modified by introducing a nonmetal doping element, preventing the formation of Mg alloy phases. Sometimes elements such as boron and nitrogen are used to modify the host material, and sometimes entire inorganic clusters are used, as in the work of Muhammad Ramzan Saeed Ashraf Janjua [97]. Researchers are trying to synthesize materials for storing hydrogen by encasing B12N12 nanocages in alkaline earth metals like beryllium, magnesium, and calcium inside this study. Sadhasivam Thangarasu et al. [98] provided promising research on encapsulation by developing a compositing/encapsulating platform with polymers for intermetallic and complex hydrides. The researchers have created various concepts of polymer-hydride systems, including intermetallic and complex hydrides. These systems primarily involve composites and polymer encapsulation methods, which serve to prevent contamination from air, moisture, and gas contaminants. Additionally, these methods aim to enhance the hydrogen sorption capabilities in hydrides.

Encapsulated hydrogen storage has the potential to address key challenges in hydrogen storage, including safety, volumetric efficiency, and reversible storage/release. However, to enable their practical implementation in hydrogen-based energy systems, ongoing research focuses on improving the storage capacities, kinetics, and stability of encapsulation materials.

Nanoscaffolding

Nanoscaffolding is the process of enclosing a substance within a structure with permanent porosity. Nanoscale pores or recesses in the host material allow the confined material to insert, attach, and prevent it from moving or clustering with other particles. The pores, thus, dictate the form and dimensions of the nanoscale substance [100, 101]. Nanoscaffolding in hydrogen storage involves the design and engineering of nanostructured materials to enhance hydrogen storage capacity, improve kinetics, and increase stability. This approach leverages the unique properties of nanomaterials to overcome limitations associated with traditional hydrogen storage methods. Nanoscaffolding can be applied to hydrogen storage in the following ways:

Nanoscale scaffolds possess a high surface area-to-volume ratio, which results in an increased number of active sites for hydrogen adsorption. Frequently employing materials such as nanocarbon materials [102], metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) [99, 103], and nanoporous metals can be explained due to their extensive surface areas and porous architectures.

Enhanced Reaction Rates: Nanostructured materials can improve the rates at which hydrogen sorption reactions occur by lowering the distances over which diffusion occurs and by offering efficient routes for hydrogen transport. This results in accelerated absorption and release of hydrogen molecules [89], enhancing the overall efficiency of storage.

Confinement effects refer to the phenomenon of trapping hydrogen within small pores or holes. This confinement leads to an increase in the adsorption of hydrogen at lower pressures and temperatures [104]. The confinement of hydrogen storage materials also helps to stabilize reactive intermediates and prevent component aggregation.

Surface functionalization refers to the process of altering nanoscaffolds’ surfaces by introducing catalytic sites or functional groups [105]. This alteration improves the efficiency of hydrogen dissociation, diffusion, and interaction with storage materials. By manipulating the surface chemistry, it becomes feasible to exert meticulous control over the parameters of hydrogen sorption.

Combining nanostructures with hydrogen storage components like metal hydrides [106], chemical hydrides [107], or complex hydrides [108] creates hybrid nanocomposites. The synergistic interaction between the scaffold and storage phase improves these materials’ storage capacity and kinetics.

Nanoscaffolding allows for precise manipulation of the thermodynamics of hydrogen sorption reactions by altering nanomaterials’ size, shape, and chemical composition. This change improves the capacity to store hydrogen to its maximum capability and optimizes the operational parameters [107, 108].

Nanostructuring Bulk Materials: By altering their structure at the nanoscale and building nanoscale scaffolds, can enhance the performance of bulk hydrogen storage materials. This procedure involves decreasing the size of grains, introducing defects at the nanoscale, or applying nanostructured coatings to enhance the properties of hydrogen absorption and release [109].

Additional methods

Additional methods for producing composite materials include catalyst doping [91], nanosizing [114], mechanochemistry [115], physical vapor deposition (PVD) [116], and various other processes. To make composite materials that can store hydrogen, many factors must be carefully considered, including their hydrogen capacity, kinetics (how fast they take in and release hydrogen), thermodynamics (working temperatures and pressures), reversibility, and stability. Computational methods, such as density functional theory (DFT), are crucial for forecasting and improving the properties of these materials. They assist in directing experimental efforts towards the creation of efficient hydrogen storage devices.

Density functional theory for composite materials

The hydrogen storage area uses Density Functional Theory (DFT) to predict and understand many aspects of the materials used for this purpose. DFT is used in diverse methodologies.

It is possible to use density functional theory (DFT) simulations to determine the adsorption energies of hydrogen molecules on various surfaces or within porous materials. This facilitates the identification of substances with a significant capacity for hydrogen adsorption, which is critical for efficient storage [110, 111].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) provides useful insights into the electrical arrangement of materials before and after hydrogen adsorption. Understanding how hydrogen interacts with a substance and affects its properties is essential [112].

Furthermore, it is possible to compute and determine material optimization, diffusion and desorption kinetics, thermodynamics, material screening and mechanism comprehension [113].

Conclusion

Based on the comprehensive exploration of hydrogen storage materials presented in this review article, it is significant to highlight that solid-state physical and chemical storage are two ways of storing hydrogen with promising advancements. These developments hold promise for addressing key challenges in the transition towards sustainable energy systems, particularly concerning hydrogen as a clean energy carrier.

Solid-state physical storage materials, such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent-organic frameworks (COFs), possess exceptional porosity and surface area, rendering them exceptionally efficient for hydrogen adsorption. Although MOFs and COFs have difficulties related to humidity sensitivity and solvent exposure, they exhibit exceptional capacities in hydrogen storage under specified circumstances. Additionally, solid-state chemical storage materials, such as metal hydrides and complex hydrides, offer significant hydrogen storage capacities together with reliable cycle stability and rapid kinetics. These materials are crucial for both mobile and stationary applications, guaranteeing the secure and efficient application of hydrogen in different industries.

Developing practical methods for storing hydrogen entails addressing challenges such as the expense of materials, the ability to produce on a large scale, and enhancing storage efficiency under different conditions. Current research is dedicated to improving the characteristics of these materials by using advanced methods of synthesis, nanostructuring, and including catalytic functions to enhance the rate of reaction and durability.

To successfully incorporate complex hydrogen storage materials into practical applications, it is crucial for researchers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers to work collaboratively. This cooperation is necessary to ensure that the technology reaches a level of maturity and commercial feasibility. Hydrogen storage technologies have the potential to play a vital role in reaching global sustainability goals and promoting a cleaner energy future by tackling these problems and taking advantage of upcoming opportunities.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR21882439).

Abbreviations

- COF

Covalent-organic framework

- DFT

Density functional theory

- H/M

Hydrogen-to-metal atom ratio

- MOF

Metal-organic frameworks

- NPF

Nitrogen-rich porous framework

- PCI

Pressure-composition isotherms

- SBU

Secondary building unit

- THF

Tetrahydrofuran

- ZIF

Zeolitic Imidazolate framework

Author contributions

N.N. conceived, supervised the project, and approved the final version for publication. K.S.R supervised the project. MRK contributed to the conception and design of the work. M.R.K, A.D.O, B.S., R.S., TO, and A.M.M were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Funding

The Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR21882439).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: In the Acknowledgements and Funding sections of this article, the grant number relating to the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan was incorrectly given as “BR21882185” and should have been “BR21882439”.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/12/2025

The original version of this article was revised: In the Acknowledgements and Funding sections of this article, the grant number relating to the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan was incorrectly given as “BR21882185” and should have been “BR21882439”.

Change history

2/18/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s11671-025-04216-8

References

- 1.Kumar N, Singh H, Kumar A. Renewable Energy and Green Technology. 1st ed. CRC Press; 2021. 10.1201/9781003175926

- 2.Acar C, Dincer I. 1.13 Hydrogen energy. In: Dincer I, editor. Comprehensive Energy Systems. Oxford; 2018. pp. 568–605. 10.1016/b978-0-12-809597-3.00113-9

- 3.González R, Cabeza IO, Casallas-Ojeda M, Gómez X. Biological hydrogen methanation with carbon dioxide utilization: methanation acting as mediator in the hydrogen economy. Environments. 2023. 10.3390/environments10050082. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehr AS, Phillips AD, Brandon MP, Pryce MT, Carton JG. Recent challenges and development of technical and technoeconomic aspects for hydrogen storage, insights at different scales. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.05.182. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker G. Hydrogen storage technologies. In: Walker G, editor. Solid-state hydrogen storage. Woodhead Publishing series in electronic and optical materials; Woodhead Publishing; 2008. pp 3–17. 10.1533/9781845694944.1.3

- 6.Principi G, Agresti F, Maddalena A, Lo RS. The problem of solid state hydrogen storage. Energy. 2009. 10.1016/j.energy.2008.08.027. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlapbach L, Züttel A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature. 2001. 10.1038/35104634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Y, Zhou Y, Li Y, Ding Z. Research progress and application prospects of solid-state hydrogen storage technology. Molecules. 2024. 10.3390/molecules29081767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prachi RP, Mahesh MW, Aneesh CG. A review on solid state hydrogen storage material. Adv Energy Power. 2016. 10.13189/aep.2016.040202

- 10.Abdechafik EH, Ousaleh HA, Mehmood S, Baba YF, Bürger I, Linder M, Faik A. An analytical review of recent advancements on solid-state hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.10.218. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zacharia R, Rather SU. Review of solid state hydrogen storage methods adopting different kinds of novel materials. J Nanomater. 2015. 10.1155/2015/914845. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaghi OM, Kalmutzki MJ, Diercks CS. Introduction to reticular chemistry. Wiley. 2019. 10.1002/9783527821099. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y. Application of different porous materials for hydrogen storage. J Phys. 2022. 10.1088/1742-6596/2403/1/012012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erdogan FO, Celik C, Turkmen AC, Sadak AE, Cücü E. Hydrogen storage behavior of zeolite/graphene, zeolite/multiwalled carbon nanotube and zeolite/green plum stones-based activated carbon composites. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023. 10.1016/j.est.2023.108471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broom DP, Webb CJ, Hurst KE, Parilla PA, Gennett T, Brown CM, Zacharia R, Tylianakis E, Klontzas E, Froudakis GE, Steriotis TA, Trikalitis PN, Anton DL, Hardy B, Tamburello D, Corgnale C, Van Hassel BA, Cossement D, Chahine R, Hirscher M. Outlook and challenges for hydrogen storage in nanoporous materials. Appl Phys A. 2016. 10.1007/s00339-016-9651-4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochat S, Polak-Kraśna K, Tian M, Holyfield LT, Mays TJ, Bowen CR, Burrows AD. Hydrogen storage in polymer-based processable microporous composites. J Mater Chem. 2017. 10.1039/c7ta05232d. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Xue Z, Niu K, Liu X, Lv NW, Zhang B, Li Z, Zeng H, Ren Y, Wu Y, Zhang Y. Li–fluorine codoped electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced hydrogen storage. RSC Adv. 2021. 10.1039/d0ra06500e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoddart A. Predicting perfect pores. Nat Rev Mater. 2020. 10.1038/s41578-020-0200-6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munir A, Ahmad A, Sadiq MT, Sarosh A, Abbas G, Ali A. Synthesis and characterization of carbon-based composites for hydrogen storage application. Eng Proc. 2021. 10.3390/engproc2021012052. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Jin Z, Huang X, Liu R, Su Y, Zhang Q. Hydrogen adsorption in porous geological materials: a review. Sustainability. 2024. 10.3390/su16051958. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Züttel A. Hydrogen storage methods. The science of nature; 2004. pp. 157–172; 10.1007/s00114-004-0516-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Tranchemontagne DJ, Mendoza-Cortes JL, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Secondary building units, nets and bonding in the chemistry of metal-organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev. 2009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zaworotko MJ. Crystal engineering of diamondoid networks. Chem Soc Rev. 1994

- 24.Li H, Eddaoudi M, Groy TL, Yaghi OM. Establishing microporosity in open metal-organic frameworks: gas sorption isotherms for Zn(BDC) (BDC = 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylate). J Am Chem Soc. 1998

- 25.Li H, Eddaoudi M, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Design and Synthesis of an Exceptionally Stable and Highly Porous Metal-organic Framework. Nature. 1999

- 26.Kaye SS, Dailly A, Yaghi OM, Long JR. Impact of preparation and handling on the hydrogen storage properties of Zn4O(1,4-benzenedicarboxylate)3 (MOF-5). J Am Chem Soc. 2007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Feng X, Ding X, Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks. Chem Soc rev. 2012. 10.1039/c2cs35157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang N, Wang P, Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks: a materials platform for structural and functional designs. Nat Rev Mater. 2016. 10.1038/NATREVMATS.2016.68. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks: an amazing chemistry platform for designing polymers. Chem. 2020. 10.1016/J.CHEMPR.2020.08.024. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lohse MS, Bein T. Covalent organic frameworks: structures, synthesis, and applications. Adv Func Mat. 2018. 10.1002/adfm.201705553. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang D. Covalent organic frameworks: a molecular platform for designer polymeric architectures and functional materials. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2021. 10.1246/bcsj.20200389. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixit M, Maark TA, Pal S. Ab initio and periodic DFT investigation of hydrogen storage on light metal-decorated MOF-5. Intl J Hydrogen Energy. 2011. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.05.165. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler KT, Hendon CH, Walsh A. Electronic chemical potentials of porous metal–organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2011. 10.1021/ja4110073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodrenko IV, Avdeenkov AV, Bessarabov DG, Bibikov AV, Nikolaev AV, Taran MD, Tkalya EV. Hydrogen storage in aromatic carbon ring based molecular materials decorated with alkali or alkali-earth metals. J Phy Chem C. 2012. 10.1021/jp305324p. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bordiga S, Vitillo JG, Ricchiardi G, Regli L, Cocina D, Zecchina A, Arstad B, Bjørgen M, Hafizovic J, Lillerud KP. Interaction of hydrogen with MOF-5. J of Phy Chem B. 2005. 10.1021/jp052611p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowsell J, Yaghi O. Effects of functionalization, catenation, and variation of the metal oxide and organic linking units on the low-pressure hydrogen adsorption properties of metal−organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc. 2006. 10.1021/ja056639q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiswall RH, Reilily JJ. Hydrogen storage in metal hydrides. Science. 1974 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Cummings DL, Powers GJ. The storage of hydrogen as metal hydrides. Ind & Eng Chem Proc Design and Dev. 1974. 10.1021/i260050a015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman K, Reilly J, Salzano F, Waide C, Wiswall R, Winsche W. Metal hydride storage for mobile and stationary applications. Int J of Hydrogen Energy. 1976. 10.1016/0360-3199(76)90067-7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reilly JJ, Sandrock GD. Hydrogen storage in metal hydrides. Sci Am. 1980. 10.1038/scientificamerican0280-118. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huston E, Sandrock G. Engineering properties of metal hydrides. J Less Common Met. 1980. 10.1016/0022-5088(80)90182-4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suda S. Metal hydrides. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 1987. 10.1016/0360-3199(87)90057-7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Güther V, Otto A. Recent developments in hydrogen storage applications based on metal hydrides. J Alloy Compd. 1999. 10.1016/s0925-8388(99)00385-0. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowman RC, Fultz B. Metallic hydrides I: hydrogen storage and other gas-phase applications. MRS Bull. 2002. 10.1557/mrs2002.223. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakintuna B, Lamaridarkrim F, Hirscher M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2007. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2006.11.022. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dornheim M. Thermodynamics of metal hydrides: tailoring reaction enthalpies of hydrogen storage materials. IntechOpen; 2011

- 47.Rusman N, Dahari M. A review on the current progress of metal hydrides material for solid-state hydrogen storage applications. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2016. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.05.244. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox KE, Williamson KD. Hydrogen: Its Technology and Implication. 1st ed. CRC Press; 1979.

- 49.Tarasov BP, Fursikov PV, Volodin AA, Bocharnikov MS, Shimkus YY, Kashin AM, Yartys VA, Chidziva S, Pasupathi S, Lototskyy MV. Metal hydride hydrogen storage and compression systems for energy storage technologies. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2021. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.07.085. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drawer C, Lange J, Kaltschmitt M. Metal hydrides for hydrogen storage—identification and evaluation of stationary and transportation applications. J Energy Storage. 2024. 10.1016/j.est.2023.109988. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nivedhitha KS, Beena T, Banapurmath NR, Umarfarooq MA, Ramasamy V, Soudagar MEM, Ağbulut U. Advances in Hydrogen Storage with metal hydrides: mechanisms, materials, and challenges. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.02.335. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aceves S, Berry G, Martinezfrias J, Espinosaloza F. Vehicular storage of hydrogen in insulated pressure vessels. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2006. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2006.02.019. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davids M, Martin T, Lototskyy M, Denys R, Yartys V. Study of hydrogen storage properties of oxygen modified Ti- based AB2 type metal hydride alloy. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2021. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.05.215. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bishnoi A, Pati S, Sharma P. Architectural design of metal hydrides to improve the hydrogen storage characteristics. J Power Sources. 2024. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.234609. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lototskyy M, Tarasov B, Yartys V. Gas-phase applications of metal hydrides. J Energy Storage. 2023. 10.1016/j.est.2023.108165. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pistidda C. Solid-state hydrogen storage for a decarbonized society. Hydrogen. 2021. 10.3390/hydrogen2040024. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma VK, Kumar EA. Metal hydrides for energy applications—classification, PCI characterisation and simulation. Int J Energy Res. 2016. 10.1002/er.3668. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kojima Y. Hydrogen storage materials for hydrogen and energy carriers. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2019. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.05.119. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang L, Wang F, Rong M, Wang Z, Yang S, Wang J, Zhou H. Recent advances on preparation method of Ti-based hydrogen storage alloy. J Mater Sci Chem Eng. 2020. 10.4236/msce.2020.812003. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu Y, Chabane D, Elkedim O. Intermetallic compounds synthesized by mechanical alloying for solid-state hydrogen storage: a review. Energies. 2021. 10.3390/en14185758. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srinivasan SS, Demirocak DE. Metal hydrides used for hydrogen storage. Nanostruct Mater Next-Generat Energy Storage Convers. 2016. 10.1007/978-3-662-53514-1_8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Züttel A, Wenger P, Rentsch S, Sudan P, Mauron Ph, Emmenegger Ch. LiBH4 a new hydrogen storage material. J Power Sources. 2003. 10.1016/S0378-7753(03)00054-5. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Srinivasan S, Escobar D, Goswami Y, Stefanakos E. Effects of catalysts doping on the thermal decomposition behavior of Zn(BH4)2. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2008. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.02.062. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang ZG, Guo ZP, Calka A, Wexler D, Lukey C, Liu HK. Effects of iron oxide (Fe2O3, Fe3O4) on hydrogen storage properties of Mg-based composites. J Alloy Compd. 2006. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2005.11.074. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Møller K, Sheppard D, Ravnsbæk D, Buckley C, Akiba E, Li H-W, Jensen T. Complex metal hydrides for hydrogen, thermal and electrochemical energy storage. Energies. 2017;10(10):1645. 10.3390/en10101645. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iosub V, Matsunaga T, Tange K, Ishikiriyama M. Direct synthesis of Mg(AlH4)2 and CaAlH5 crystalline compounds by ball milling and their potential as hydrogen storage materials. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.11.013. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Srinivasan SS, Brinks HW, Hauback BC, Sun D, Jensen CM. Long term cycling behavior of titanium doped NaAlH4 prepared through solvent mediated milling of NaH and Al with titanium dopant precursors. J Alloys Compd. 2004. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2004.01.044. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tang X, Opalka SM, Laube BL, Wu FJ, Strickler JR, Anton DL. Hydrogen storage properties of Na–Li–Mg–Al–H complex hydrides. J Alloys Compd. 2007. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.12.089. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bogdanovic B, Felderhoff M, Streukens G. Hydrogen storage in complex metal hydrides. J Serb Chem Soc. 2009. 10.2298/JSC0902183B. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ashby EC, Brendel GJ, Redman HE. Direct synthesis of complex metal hydrides. Inorg Chem. 1963. 10.1021/ic50007a018. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suárez-Alcántara K, Tena-Garcia JR, Guerrero-Ortiz R. Alanates, a comprehensive review. Mater Technol Hydrogen Fuel Cells. 2019. 10.3390/ma12172724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.George L, Saxena SK. Structural stability of metal hydrides, alanates and borohydrides of alkali and alkali- earth elements: a review. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.03.078. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Srinivasa Murthy S, Anil KE. Advanced materials for solid state hydrogen storage: “Thermal engineering issues.” Appl Therm Eng. 2014. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.04.020. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choudhury P, Srinivasan SS, Bhethanabotla VR, Goswami Y, McGrath K, Stefanakos EK. Nano-Ni Doped Li–Mn–B–H system as a new hydrogen storage candidate. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.06.004. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barkhordarian G, Klassen T, Dornheim M, Bormann R. Unexpected kinetic effect of MgB2 in reactive hydride composites containing complex borohydrides. J Alloys Compd. 2007. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.09.048. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schneemann A, White JL, Kang S, Jeong S, Wan LF, Cho ES, Heo TW, Prendergast D, Urban JJ, Wood BC, Allendorf MD, Stavila V. Nanostructured metal hydrides for hydrogen storage. Chem Rev. 2018. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qiu S, Chu H, Zou Y, Xiang C, Xu F, Sun L. Light metal borohydrides/amides combined hydrogen storage systems: composition, structure and properties. J Mater Chem A Mater. 2017. 10.1039/C7TA09113C. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang BJ, Liu BH. Hydrogen desorption from LiBH4 destabilized by chlorides of transition Metal Fe Co, and Ni. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.04.165.20652089 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lambregts SFH, van Eck ERH, Suwarno, Ngene P, de Jongh PE, Kentgens APM. Phase behavior and ion dynamics of nanoconfined LiBH4 in Silica. J Phys Chem C. 2019. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b06477

- 80.Fang ZZ, Wang P, Rufford TE, Kang XD, Lu GQ, Cheng HM. Kinetic- and thermodynamic-based improvements of lithium borohydride incorporated into activated carbon. Acta Mater. 2008. 10.1016/j.actamat.2008.08.033. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chong L, Zeng X, Ding W, Liu D, Zou J. NaBH4 in “Graphene wrapper:″ significantly enhanced hydrogen storage capacity and regenerability through nanoencapsulation. Adv Mater. 2015. 10.1002/adma.201500831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia G, Tan Y, Wu F, Fang F, Sun D, Guo Z, Huang Z, Yu X. Graphene-wrapped reversible reaction for advanced hydrogen storage. Nano Energy. 2016. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.06.016. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cho ES, Ruminski AM, Liu YS, Shea PT, Kang S, Zaia EW, Park JY, Chuang YD, Yuk JM, Zhou X. Hierarchically controlled inside-out doping of Mg nanocomposites for moderate temperature hydrogen storage. Adv Funct Mater. 2017. 10.1002/adfm.201704316.28798658 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bardhan R, Ruminski AM, Brand A, Urban JJ. Magnesium nanocrystal-polymer composites: a new platform for designer hydrogen storage materials. Energy Environ Sci. 2011. 10.1039/c1ee02258j. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Plerdsranoy P, Wiset N, Milanese C, Laipple D, Marini A, Klassen T, Dornheim M, Gosalawit-Utke R. Improvement of thermal stability and reduction of LiBH4/polymer host interaction of nanoconfined LiBH4 for reversible hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2015. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.10.090. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu C, Zou JX, Shi XY, Zeng XQ, Ding WJ. Synthesis and hydrogen storage properties of core shell structured binary Mg@Ti and ternary Mg@Ti@Ni composites. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2017. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.10.088. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fry CMP, Grant DM, Walker GS. Improved hydrogen cycling kinetics of nano-structured magnesium/transition metal multilayer thin films. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2013. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.10.089. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klebanoff L. Hydrogen Storage Technology: Materials and Applications. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jeon K, Moon HR, Ruminski AM, Jiang B, Kisielowski C, Bardhan R, Urban JJ. Air-stable magnesium nanocomposites provide rapid and high-capacity hydrogen storage without using heavy-metal catalysts. Nat Mater. 2011. 10.1038/nmat2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.BerubeV, Chen G, Dresselhaus MS. Impact of nanostructuring on the enthalpy of formation of metal hydrides. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2008. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.05.083

- 91.Liang J. Theoretical insight on tailoring energetics of Mg hydrogen absorption/desorption through nano-engineering. Appl Phys A. 2005. 10.1007/s00339-003-2382-3. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paskevicius M, Sheppard DA, Buckley CE. Thermodynamic changes in mechanochemically synthesized magnesium hydride nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2010. 10.1021/ja908398u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nielsen TK, Besenbacher F, Jensen TR. Nanoconfined hydrides for energy storage. Nanoscale. 2011. 10.1039/c0nr00725k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang J, Zhu Y, Lin H, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Li S, Ma Z, Li L. Metal hydride nanoparticles with ultrahigh structural stability and hydrogen storage activity derived from microencapsulated nanoconfinement. Adv Mater. 2017. 10.1002/adma.201700760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Borislav B, Manfred S. Ti-doped alkali metal aluminium hydrides as potential novel reversible hydrogen storage materials. J Alloys Compd. 1997. 10.1016/S0925-8388(96)03049-6. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cho YJ, Kang SY, Wood BC, Cho ES. Heteroatom-doped graphenes as actively interacting 2D encapsulation media for Mg-based hydrogen storage. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2022. 10.1021/acsami.1c23837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Janjua MRSA. Theoretical framework for encapsulation of inorganic B12N12 nanoclusters with alkaline earth metals for efficient hydrogen adsorption: a step forward toward hydrogen storage materials. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thangarasu S, Palanisamy G, Im YM, Oh TH. An alternative platform of solid-state hydrides with polymers as composite/encapsulation for hydrogen storage applications: effects in intermetallic and complex hydrides. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.02.115. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zlotea C, Campesi R, Cuevas F, Leroy E, Dibandjo P, Volkringer C, Loiseau T, Férey G, Latroche M. Pd nanoparticles embedded into a metal-organic framework: synthesis, structural characteristics, and hydrogen sorption properties. J Am Chem Soc. 2010. 10.1021/ja9084995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang L, Rawal A, Aguey-Zinsou KF. Hydrogen storage properties of nanoconfined aluminium hydride (AlH3). Chem Eng Sci. 2018. 10.1016/j.ces.2018.02.014. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fichtner M, Zhao-Karger Z, Hu J, Roth A, Weidler P. The kinetic properties of Mg (BH4)2 infiltrated in activated carbon. Nanotechnology. 2009. 10.1088/0957-4484/20/20/204029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.de Jongh PE, Wagemans RWP, Eggenhuisen TM, Dauvillier BS, Radstake PB, Meeldijk JD, Geus JW, de Jong KP. The preparation of carbon-supported magnesium nanoparticles using melt infiltration. Chem Mater. 2007. 10.1021/cm702205v. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stavila V, Bhakta RK, Alam TM, Majzoub EH, Allendorf MD. Reversible hydrogen storage by NaAlH4 confined within a titanium-functionalized MOF-74(Mg) nanoreactor. ACS Nano. 2012. 10.1021/nn304514c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rossin A, Tuci G, Luconi L, Giambastiani G. Metal-organic frameworks as heterogeneous catalysts in hydrogen production from lightweight inorganic hydrides. ACS Catal. 2017. 10.1021/acscatal.7b01495. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sun C, Liu X, Bai X. Significantly improved dehydrogenation of dodecyl-N-ethylcarbazole over supported PdFe bimetallic nanocatalysts via polydopamine surface modification of Al2O3. Fuel. 2024. 10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131759. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang S, Gross AF, Van Atta SL, Lopez M, Liu P, Ahn CC, Vajo JJ, Jensen CM. The synthesis and hydrogen storage properties of a MgH2 incorporated carbon aerogel scaffold. Nanotechnology. 2009. 10.1088/0957-4484/20/20/204027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Miedema PS, Ngene P, van der Eerden AMJ, Sokaras D, Weng T, Nordlund D, Au YS, de Groot FMF. In situ X-ray Raman spectroscopy study of the hydrogen sorption properties of lithium borohydride nanocomposites. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014. 10.1039/C4CP02918F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nielsen TK, Javadian P, Polanski M, Besenbacher F, Bystrzycki J, Skibsted J, Jensen TR. Nanoconfined NaAlH4: prolific effects from increased surface area and pore volume. Nanoscale. 2014. 10.1039/C3NR03538G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stephens RD, Gross AF, Van Atta SL, Vajo JJ, Pinkerton FE. The kinetic enhancement of hydrogen cycling in NaAlH4 by melt infusion into nanoporous carbon aerogel. Nanotechnology. 2009. 10.1088/0957-4484/20/20/204018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Michel KJ, Ozoliņš V. Recent advances in the theory of hydrogen storage in complex metal hydrides. MRS Bull. 2013. 10.1557/mrs.2013.130. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bourgeois N, Crivello JC, Cenedese P, Joubert JM. Systematic first-principles study of binary metal hydrides. ACS Comb Sci. 2017. 10.1021/acscombsci.7b00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li XH, Ju XH. Density functional theory study on (Mg(BH4))(n) (n = 1–4) clusters as a material for hydrogen storage. Comput Theor Chem. 2013. 10.1016/j.comptc.2013.10.005.24443709 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Majzoub EH, Zhou F, Ozoliņš V. First-principles calculated phase diagram for nanoclusters in the Na–Al–H system: a single-step decomposition pathway for NaAlH4. J Phys Chem C. 2011. 10.1021/jp109420e. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jun S, Joo SH, Ryoo R, Kruk M, Jaroniec M, Liu Z, Ohsuna T, Terasaki O. Synthesis of new, nanoporous carbon with hexagonally ordered mesostructure. J Am Chem Soc. 2000. 10.1021/ja002261e. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Çakmak G, Károly Z, Mohai I, Öztürk T, Szépvölgyi J. The processing of Mg–Ti for hydrogen storage; mechanical milling and plasma synthesis. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.08.013. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pang Y, Liu Y, Gao M, Ouyang L, Liu J, Wang H, Zhu M, Pan H. A mechanical-force-driven physical vapour deposition approach to fabricating complex hydride nanostructures. Nat Commun. 2014. 10.1038/ncomms4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.