Abstract

The roles of host cell miRNAs have not been well studied in the context of BCoV replication and immune regulation. This study aimed to identify miRNA candidates that regulate essential host genes involved in BCoV replication, tissue tropism, and immune regulation. To achieve these goals, we used two isolates of BCoV (enteric and respiratory) to infect bovine endothelial cells (BECs) and Madine Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK) cells. We determined the miRNA expression profiles of these cells after BCoV infection. The expression of miRNA16a is differentially altered during BCoV infection. Our data show that miRNA16a is a significantly downregulated miRNA in both in vitro and ex vivo models. We confirmed the miRNA16aexpression profile by qRT–PCR. Overexpression of pre-miRNA16ain the BEC and the MDBK cell lines markedly inhibited BCoV infection, as determined by the viral genome copy numbers measured by qRT‒PCR, viral protein expression (S and N) measured by Western blot, and virus infectivity using a plaque assay. Our bioinformatic prediction showed that Furin is a potential target of miRNA16a. We compared the Furin protein expression level in pre-miRNA16a-transfected/BCoV-infected cells to that in pre-miRNA-scrambled-transfected cells. Our qRT-PCR and Western blot data revealed marked inhibition of Furin expression at the mRNA and protein levels, respectively. BCoV-S protein expression was markedly inhibited at both the mRNA and protein levels. To further confirm the impact of the downregulation of the Furin enzyme on the replication of BCoV, we transfected cells with specific Furin-siRNAs parallel to the scrambled siRNA. Marked inhibition of BCoV replication was observed in the Furin-siRNA-treated group. To further validate Furin as a novel target for miRNA16a, we cloned the 3’UTR of bovine Furin carrying the seed region of miRNA16a in the dual luciferase vector. Our data showed that luciferase activity in pre-miRNA16a-transfected cells decreased by more than 50% compared to cells transfected with the construct carrying the mutated Furin seed region. Our data confirmed that miRNA16ainhibits BCoV replication by targeting the host cell line Furin and the BCoV-S glycoprotein. It also enhances the host immune response, which contributes to the inhibition of viral replication. This is the first study to confirm that Furin is a valid target of miRNA16a. Our findings highlight the clinical applications of host miRNA16a as a potential miRNA-based vaccine/antiviral therapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-80708-4.

Keywords: BCoV, Enteric, Respiratory, Tropism, Spike, Nucleocapsid, Gene regulation, Furin, IL6, Cytokine expression

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) was recently classified under the order Nidovirales in the family Coronaviridae, subfamily Orthocoronavirinae, genus Betacoronavirus, and subgenus Embecovirus1. Both BCoV and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-1 and -2 belong to the genus Betacoronavirus. These viruses share some common characteristics at the phenotypic and genotypic levels. Although BCoV was reported several decades ago, many aspects of viral replication and virus/host interactions have not yet been explored. This contrasts with SARS-CoV-2, the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic; intensive studies have been carried out and revealed many novel aspects of the SARS-CoV-2/host interaction. Viral entry is a crucial step in the coronavirus replication cycle. Angiotensinogen converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) has been proven to be the functional receptor for SARS-CoV-22. Transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) plays essential roles in SARS-CoV-2 attachment and entry into host cells through cleavage of the viral spike glycoprotein at specific sites. S protein cleavage activates BCoV infection in host cells and contributes to virus entry into host cells3. The roles of neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) in SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells have recently been studied4. NRP-1 binds to the cleaved substrate of the host cell Furin, which enhances virus replication and plays an essential role in viral immune evasion4. However, the roles of Furin, ACE2, TMPRRS2, and NRP-1 in BCoV replication have not yet been studied. The BCoV genome is a single molecule of positive sense RNA (ssRNA, + Ve). The BCoV genome has the typical genome structure and organization of most coronaviruses. The genome is flanked by two untranslated regions at the 5’ and 3’ ends. The 5’ two-thirds of the genome consists of a large gene called gene-1, which is composed of two overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) with a ribosomal frameshift. Gene-1 of BCoV is further processed into 16 nonstructural proteins (NSP1-16). The 3’ one-third of the BCoV genome is occupied by five major structural proteins (hemagglutinin esterase (HE), spike glycoprotein (S), the envelope (E), and the nucleocapsid protein (N)) interspersed with other nonstructural proteins5. BCoV infection causes several clinical syndromes in affected cattle, including calf diarrhea and winter dysentery, and it also contributes to the development of the bovine respiratory disease complex, along with other bacterial pathogens6. Most coronaviruses require initial cleavage steps by some host cell proteases, particularly serine proteases, to initiate active infection in the target host. Furin cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is a prerequisite for viral infection in target hosts7. Viral tropism heavily depends on the availability of specific cellular receptors that help the virus enter host cells and hijack the cellular machinery to favor viral protein synthesis instead of cellular proteins8. Other factors may also contribute to this tissue tropism, such as some auxiliary receptors and some transcription and translation factors9. BCoV exhibits dual tissue tropism in affected cattle (enteric and respiratory)10. The mechanisms that fine-tune this dual tissue tropism have not been well studied. Host cell microRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNAs. molecules (21–25 nucleotides in length) that play important roles in gene regulation at the translation level. miRNA candidates usually bind to certain regions in the 3’UTR of target genes, leading to translation inhibition or repression11. There is an important region in the structure of each miRNA called the seed region, which is usually located at positions 2–8 nucleotides at the 5’ end of the miRNA12. The mechanism of action of each miRNA molecule is mainly governed by the degree of complementarity between the miRNA seed region and the complementary region in each mRNA13. Some DNA viruses, especially herpes viruses, encode viral miRNAs14. In contrast, RNA viruses do not usually encode their own miRNAs. However, host cell miRNAs play important roles in the replication of both DNA and RNA viruses, their tissue tropism, and their immune regulation/evasion8. Little is known about the role of host cell miRNAs in the molecular biology of BCoV. We recently identified some potential host cell miRNAs that may play essential roles in the molecular pathogenesis of BCoV and could partially explain this virus’s dual tropism phenomenon15. It has been shown that miRNA16a is involved in many processes, including the cell cycle and tumor formation. miRNA-16 also acts as a diagnostic marker, is involved in gene regulation, and acts as a potential therapeutic target for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in humans16,17. However, the roles of miRNA16ain BCoV replication immune regulation/evasion have not yet been studied. Our data confirms marked differential expression levels of the host miRNA16a in cells infected with the BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp isolates. This pattern of differential expression of miRNA16a may at least partially explains the dual tropism of BCoV. The main goals of the current study were to confirm the differential expression of miRNA16ain the context of BCoV infection, to study the impacts of miRNA16aoverexpression on BCoV replication and to study the mechanism of action of miRNA16ain the fine-tuning of BCoV replication and immune regulation.

Materials and methods

Viruses and cell lines

Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (BECs), ATCC® CRL1733™) were obtained from the ATCC. These cells were tested for the absence of BVDV. Cells were cultured in F12 media (ATCC, 30-2004) supplemented with 10% horse serum (HS) (Gibco; Ref. No. 26050-088), 1% 10,000 µg/mL streptomycin and 10,000 units/mL penicillin antibiotics (Gibco; Ref. No. 15140-122). Dr. Udeni B. R. Balasuriya, Louisiana State University, kindly provided Madine Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK) cells). The MDBK cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle media (Sigma‒Aldrich, Cat. No. M0200-500ML) supplemented with 10% horse serum and 1% streptomycin and penicillin antibiotics. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for subsequent culture. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK-293) cells were obtained from the ATCC (Catalog # CRL-3216™) and used in the dual luciferase assay as described below (“Cell viability assay” section). Two bovine coronaviruses (BCoV) isolates were used; the enteric isolate ‘Mebus’18 was obtained from BEI resources (BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Bovine Coronavirus (BCoV), Mebus, NR-445). The respiratory isolate of BCoV was kindly provided by Dr. Aspen Workman (Animal Health Genomics Research Unit, USDA, ARS., USA, Meat Animal Research)19.

The next-generation sequencing (NGS) and host cell miRNA expression profiles during BCoV replication

The BEC cells were infected independently with either BCoV enteric or BCoV respiratory isolates at a multiplicity of infection of 1 (MOI). The infected cells were observed under an inverted microscope daily for up to 4 days post-infection (dpi). We monitored the infected cells for the development of any cytopathic effects (CPE) for up to five days post-infection (5 dpi). We collected cell culture supernatants from all groups of infected cells, including the mock-infected group. Per the manufacturer’s instructions, we extracted the total miRNAs using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen: Cat. No. 217084). The total miRNAs were submitted to LC Sciences (LC Sciences, LLC, 2575 West Belfort Street, Houston, TX 77054, USA) for the reporting of the miRNA expression profiles in various treated groups of cells. All the extracted RNA was briefly used for library preparation following Illumina’s TruSeq small RNA sample preparation protocols (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Quality control analysis and quantification of the DNA library were performed using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity D.N.A. Chip. Following the manufacturer’s recommended protocols, single-end sequencing of 50 bp fragments was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing system. We used the Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) classification version 9.0 to describe the function and properties of host genes and their related pathways with differential expression. The heatmap used in this study was designed using an online data analysis and visualization platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en).

Determination of the miRNA expression profiles following BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Rep isolate infection

We tested the MDBK and the BEC cells to confirm the miRNA expression profiles obtained from the NGS data. We infected each group of cells with either the BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp isolates parallel to the mock-infected cells. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, total miRNAs were isolated using a Pure Link miRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen; REF: K157001). We used a Nanodrop OneC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to determine the quality and concentration of the extracted total RNA from all treated groups of cells. The complementary DNA (cDNA) and the quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT‒PCR) were performed using the All-in-One miRNA qRT-PCR Detection Kit 2.0 (GeneCopoeia, Cat. No. QP115) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All the primers for miRNAs were designed using sRNAPrimerDB (http://www.srnaprimerdb.com/)20. The relative host miRNA expression profiles were normalized using two endogenous reference controls (U6 and 5S), the 2ˆ(Delta-Delta CT) method (2−ΔΔCt) as previously described21. The list of all miRNA primers used in this study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of the oligonucleotides used for the amplification of miRNA expression profiles.

| Bovine miRNA | Sense Primers (5' to 3’) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| bta-miRNA16a-F | AACCGGTAGCAGCACGTAAATAT | This study |

| bta-miR-Uni Rev-R | CAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT | |

| bta-U6-F | GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT | This study |

| bta-U6-R | CGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT | |

| 5S rRNA-Bovine-F | CATACCACCCTGAACGCG | This study |

| 5S rRNA-Bovine-R | CTACAGCACCCGGTATTCC |

Host mRNA extraction, amplification, and quantification

The RNAs were isolated from the BCoV-infected (MDBK and BEC) control cells. We used TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen; REF: 10296010) to isolate total RNA from these groups of cells. The RNA concentrations were analyzed with a NanoDrop OneC (Thermo Fisher Scientific). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was transcribed into cDNA using a high-capacity reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems; Lot: 2902953). Real-time PCR was performed using Power-Up SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Lot: 2843446) in QuantStudio3 (Applied Biosystems). We used the online primer software Primer322 to design the oligonucleotides to amplify the host genes and other oligonucleotides to amplify the partial BCoV-S and N genes. The relative gene and BCoV/S and BCoV/N gene expression levels, were normalized to that of β-actin according to the 2−ΔΔCt protocol described earlier21. The viral and host gene oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of the oligonucleotides used for the host gene and cytokine expression profiling.

| Bovine miRNA | Sense primers (5' to 3’) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| IFN-α-F | AGGTTCACAGAGTCACCCAC | This study |

| IFN-α-R | AGACCCTTCTCAGTTGTTGC | |

| IFN-β-F | TGTTTCTCCACCACAGCTCT | This study |

| IFN-β-R | TTGCTTCATCTCCTCAGGCA | |

| IFN-γ-F | TCCGGCCTAACTCTCTCCTA | This study |

| IFN-γ-R | GCCCACCCTTAGCTACATCT | |

| β-actin-F | CAAGTACCCCATTGAGCACG | This study |

| β-actin-R | GTCATCTTCTCACGGTTGGC | |

| IL-10-F | TGCTGGATGACTTTAAGGG | This study |

| IL-10-R | AGGGCAGAAAGCGATGACA | |

| IL-6-F | TCTGGGTTCAATCAGGCGAT | This study |

| IL-6-R | GTCAGTGTTTGTGGCTGGAG | |

| ACE2-F | GCTGTCGGGGAAATCATGTC | This study |

| ACE2-R | TCTCTCGCTTCATCTCCCAC | |

| Furin-F | CGAGAAGAACCACCCAGACT | This study |

| Furin-R | CTACGCCACAGACACCATTG | |

| NRP1-F | CCAGAAGCCAGAGGAGTACG | This study |

| NRP1-R | GCCTTTTCCGATTTCACCCT | |

| TMPRSS2-F | CCTTCTTAGCAGCCCAGAGT | This study |

| TMPRSS2-R | CATCTTCAAGGGAGGCCAGA | |

| BCoV-F | CTGGAAGTTGGTGGAGTT | 23 |

| BCoV-R | ATTATCGGCCTAACATACATC |

In silico miRNA target gene prediction

We used an online miRNA prediction tool (TargetScan 8.0) (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/)24 to predict and identify the target genes of some candidate bovine miRNAs (bta-miRNAs). The selection criteria for the target genes included those genes showing a significant differential expression among cells infected with BCoV/Ent/BCoV/Rep or mock-treated cells, the fold changes in the expression of the target gene in the infected group of cells compared to that in the mock-infected group, and the roles of these DEGs in the molecular pathogenesis and replication of other coronaviruses. Multiple sequence comparisons of the miRNA16a target site were also reported using TargetScan prediction tools. The potential binding sites of miRNA16ain the BCoV genome were predicted using three online miRNA target prediction tools, namely, RNA22 V2 (https://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22/), Miranda (https://tools4mirs.org/software/target_prediction/miranda/)25, and psRNA (https://www.zhaolab.org/psRNATarget/)26. The targeted site selection was based on the minimum free energy and the complementarity between the miRNA seed region and the viral gene binding sites (nucleotides 2–8 on candidate miRNAs). The presence of at least six conserved complementary nucleotides between the candidate miRNA seed region and the target location in BCoV is a prerequisite for identifying potential target prediction sites.

Transfection of miRNA mimics (pri-miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

The miRNA16a mimic sequence “UAGCAGCACGUAAAUAUUGGUG” (Lot # ASO2MJDO), Antagomir-16a sequence (Inhibitor; Lot # ASO2NBKH), and the mirVana miRNA mimic negative control (scrambled miRNA) were purchased from Ambion, Inc. siRNA targeting the BCoV spike glycoprotein sense sequence “CUGCUAAGAUAUAUGGUAUUU”, siRNA targeting the bovine Furin sense sequence “GCACAGAGAACGACGUGGAUU”, and si-GENOME nontargeting siRNA (scrambled siRNA) were obtained from Dharmacon™. All miRNAs and siRNAs were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAi-MAX (Invitrogen; Ref. No. 13778-075) as described previously27. The target cells (50% confluence) were transfected for 24 h of subculturing with the corresponding miRNA/siRNA molecules and then infected with BCoV/Ent, BCoV/Rep, or a mock for 48 h after the initial transfection. As described earlier, transfected and infected cells were incubated 48–72 h post-infection (hpi). The cell culture supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for further processing, while the adherent cells were collected and processed for Western blot analysis as previously described8,28,29.

BCoV infection protocol and the viral plaque assay

The collected cell culture supernatants from different groups of treated cells were subjected to three freezing and thawing cycles and used to titrate BCoV infectivity by the plaque assay. The cell culture supernatants were incubated with TPCK Trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific; REF: 20233) as described elsewhere30,31. An equal volume of ten µg/ml TPCK trypsin was added to each cell culture supernatant collected from variously treated cells (miRNA or siRNA treated and infected with either BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp independently). The cell culture supernatants containing BCoV, or a mock-trypsin mixture were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The MDBK cells or human rectal tumor-18 (HRT-18) cells were grown in 6-well plates (1 × 106) and inoculated with tenfold serially diluted BCoV cell culture supernatants. After one hour of incubation, the supernatant was aspirated, and the cell monolayer was covered with 3 ml of 1.5% Sekam ME Agarose (Lonza; Cat. No. 50011), 2 × EMEM (quality Biological; Cat. No. 115-073-101) supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco; REF: 15140-122) and one µg/ml TPCK trypsin. The plate was incubated at 37 °C and supplied with 5% CO2 for 72 days. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight and stained with 1% crystal violet. The plaques were counted, and the BCoV infectivity titers per group of treated cells were calculated using the Reed and Muench method32.

Western blot analysis

The MDBK cells and BEC cells harvested from the various treatment groups were washed with cold PBS and then lysed with Pierce radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; REF: 89901), 1% 0.5 M EDTA solution, and 1% Halt Protease & Phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min on ice. The collected protein samples were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS‒polyacrylamide gel (SDS‒PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Cat. No. 1620177). After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), the PVDF membranes were incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies in blocking solution. After three washes with TBST, immunoreactive bands were detected by film exposure after adding an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Bio-Rad catalog #1705060). All western blot bands were visualized with the (Gel-Doc Go Imaging System, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and analyzed with ImageJ software (San Diego, US). Bovine β-actin was used to normalize the relative expression levels of proteins. The primary antibodies were used to detect the expression levels of the BCoV-nucleocapsid mouse anti-bovine monoclonal (clone: FIPV3-70; Cat. No. MA1-82,189), BCoV-spike rabbit anti-bovine polyclonal (cat. no. PA5-117562), and β-actin rabbit anti-bovine polyclonal (Catalogue number: PA1-46296) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. Furin rabbit anti-bovine polyclonal (Cat. No. ARP45328_P050), ACE2 rabbit anti-bovine polyclonal (Cat. No. ARP53751_P050), TMPRSS2 rabbit anti-bovine polyclonal (Cat. No. ARP46628_P050), and anti-NRP1 rabbit anti-bovine polyclonal (Cat. No. ARP59101_P050) were purchased from Aviva Systems Biology. The corresponding secondary antibodies for each protein used, including horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated IgG (H + L), goat anti-rabbit (REF: 31460), and goat anti-mouse (REF: 31430), were obtained from Invitrogen. The western blot band density was measured using ImageJ software33. The mean band density of each protein was normalized by dividing its value by the mean band density of the housekeeping gene (B-actin) for each sample separately33.

Cloning of the 3’UTR of bovine Furin and the mutated seed region of miRNA16a in the dual luciferase expression vector and dual luciferase assay

The wild-type (WT) and mutant (Mut) binding sites of miRNA16a within the 3’UTR of bovine Furin and with the BCoV-Spike gene were synthesized by a commercial provider (GenScript, USA Inc.). Briefly, the WT Furin-3'UTR and BCoV-Spike construct region spanning the binding region of miRNA-16a was annealed and inserted between the SacI and XhoI regions of the pmirGLO Dual-Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (Promega, Catalog number: E1330). Mutations within the miRNA-16a-WT construct were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. The binding region of Furin and BCoV-Spike with miRNA-16a was mutated from "5’-TGCTGCT-3'" to "5’-GATGATC-3'" according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The constructs were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing (Figs. S3, S4). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the dual luciferase assay was conducted using the Pierce Renilla-Firefly Luciferase Dual Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific; Ref. No. 16185). To determine the expression levels of Furin and BCoV-Spike in miRNA-16a-transfected MDBK cells and HEK 293 T cells, we plated the cells into 24-well plates and co-/transfected these cells with 100 ng of miRNA-16a mimic and 100 ng of either pmiR-GLO-Furin-WT or pmiR-GLO-Furin-Mut plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen; Catalog # L3000001) transfection reagent. An empty plasmid (pmiR-GLO) transfected with the miRNA-16a, and pmiR-GLO-Furin-WT transfected with scrambled miRNA were used as negative controls. All experiments were repeated three independent times.

Cell viability assay

We used the cell viability assay to test the cell conditions prior to viral infection or transfection with some oligonucleotides, including miRNA mimics, antagomirs, and siRNAs. In case of BCoV infection, the MDBK and the BEC cells were seeded in 96 well plates and incubated overnight. The next day, cells were infected with BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp isolate at an MOI of 1 and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After 1 h, cells were washed and cultured in a complete medium for 48 to 72 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. In the cases of transfection, the Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen™: Catalog Number: 13778075) was used, and cells were transfected with the respective miRNA/siRNA molecules for 24 h and then infected with BCoV/Ent, or BCoV/Rep as described earlier and incubated further for 48 to 72 h. The viability of these cells was assessed using the Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) (Sigma; Catalog Number: M5655) following manufacturer instructions. The optical densities of each group of cells were measured at 560 nm, with background subtraction at 670 nm. The data analysis was carried out as shown below in “Statistical analysis” section.

Statistical analysis

The differential expression of miRNAs based on normalized deep-sequencing counts was analyzed using various statistical tests, including Fisher’s exact test, the chi-squared 2X2 test, the chi-squared nXn test, Student’s t-test, or ANOVA, depending on the experimental design. All the reported results in this study are displayed as the means ± the standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed with GraphPad Prism v9. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s or Dunnett’s test was performed among multiple groups. The students’ t-test was used to compare the samples. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical significance in the figures is indicated as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001. The data were combined from at least three independent experiments unless otherwise stated.

Results

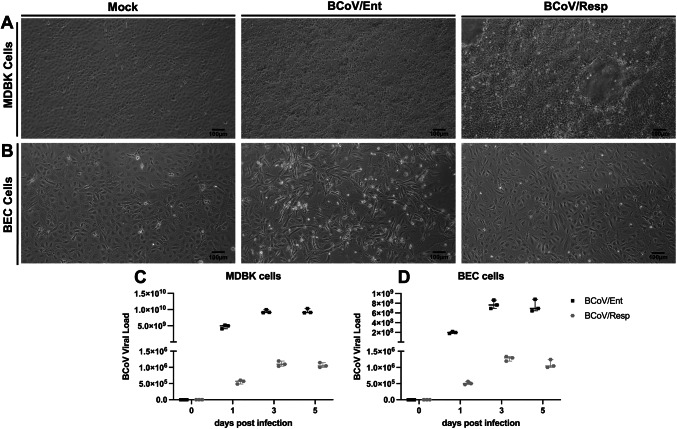

BCoV infection kinetics at various time points

The MDBK cells and the BEC cells were infected with either the BCoV/Ent or the BCoV/Resp isolates at (MOI = 1). The morphological changes and the Cytopathic Effects (CPE) in the BCoV-infected cells compared to the mock-infected cells were observed in the infected cells at 72 h post-infection (hpi) (Fig. 1A, B). The morphological observations of the BCoV-infected cells revealed more prominent CPE in the BCoV/Ent isolate-infected cells compared to the BCoV/Resp isolate-infected cells, especially in the MDBK cells (Fig. 1A). Results of cell viability before and after BCoV infection are shown in (Figs. S1A and S1B). We confirmed BCoV infection/replication at multiple time points in the MDBK, and the BEC cells infected with either the BCoV/Ent or the BCoV/Resp isolates at an MOI of 1. The BCoV genome copy numbers were reported at 0-, 1-, 3-, and 5 days post-infection (dpi). Results indicated a consistent increase in the BCoV genome load, peaking at three dpi and remaining steady through 5 dpi in both MDBK and BEC cells (Fig. 1C, D). The magnitude of the BCoV genomic viral load was more significant in the BCoV/Ent-infected cells compared to the BCoV/Resp-infected cells (Fig. 1C, D).

Fig. 1.

Replication kinetics of the Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) infection at various time points. (A) Morphological observation of control (mock) the MDBK cells showing cytopathic effects (CPE) at 72 h post-infection (hpi) with (MOI = 1) of BCoV enteric (BCoV/Ent) and respiratory (BCoV/Resp) isolates. (B) Morphological observation of BECs: Mock, CPE at 72 hpi with BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp isolates. All the images were captured at 10 × magnification. The scale represents 100µm. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of the BCoV genomic viral load in MDBK cells at different days post-infection (dpi). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of the BCoV genomic viral load in BECs at different dpi. The cells were infected with 1 MOI of virus, and samples were collected at 0, 1, 3, and 5 dpi for qRT-PCR analysis.

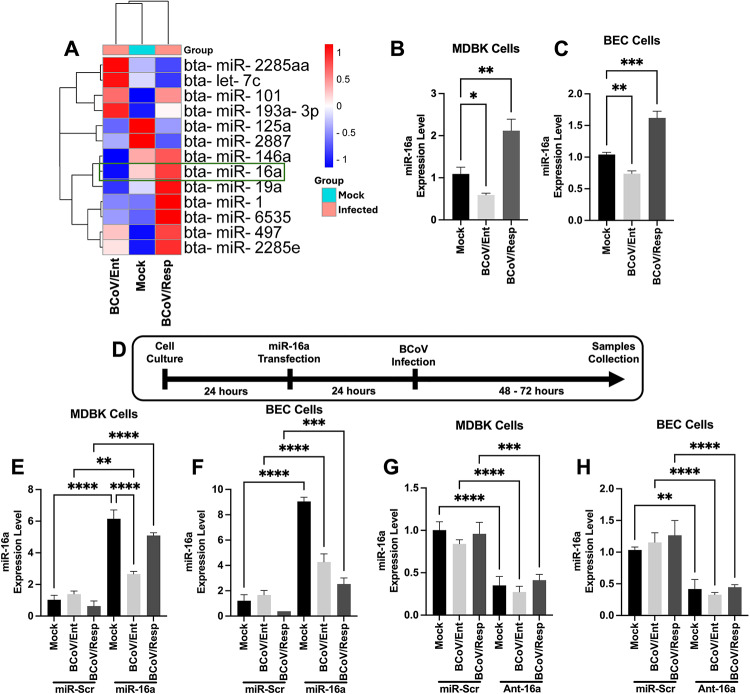

Differential expression of the host cell miRNA16a expression levels in the BCoV Ent/Resp infected cells

We analyzed the data obtained from the NGS experiments of the BCoV-infected cells to identify the potential miRNAs showing differential expression in the BCoV/Ent- and BCoV/Resp-infected groups (Fig. 2A). Our results showed that miRNA16a was downregulated in the BCoV/Ent infected cells and was upregulated in the BCoV/Resp infected cells compared to the mock-infected cells (Fig. 2A). In the case of the BCoV-infected MDBK cells, the miRNA16a was downregulated by (0.47-fold) in the BCoV/Ent group and upregulated by (1.62-fold) in the case of the BCoV/Resp infected cells (Fig. 2B). In BCoV-infected BEC cells, miRNA16awas downregulated by (1.3-fold) in the case of the BCoV/Ent-infected cells and upregulated by (1.74-fold) in the BCoV/Resp infected cells (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, miRNA16a and the antagomir-16a were independently transfected into MDBK cells and BEC cells, which were subsequently infected with BCoV/Ent/Resp in parallel with the scrambled miRNA control (miRNA-Scr) (Fig. 2D). The cells’ viability was assessed before and after the transfection of these molecules in MDBK and BEC cells (Fig. S1A, S1B, S2A–S2F). The qRT-PCR analysis revealed a significant upregulation of miRNA16a in the miRNA16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr group in both MDBK and BEC cells (Fig. 2E, F). The transfection of the antagomir-16a shows a significant downregulation of miRNA16a expression compared to the miRNA-Scr group in both the MDBK and BEC cells (Fig. 2G, H).

Fig. 2.

Bovine miRNA expression profile during BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp infection in bovine cell lines. (A) Heatmap showing the differentially expressed miRNAs in the Mock, BCoV/Ent-, and BCoV/Resp-infected groups of cells based on NGS data analysis. (B) The qRT-PCR data shows the expression levels of bovine miRNA16a in the MDBK cells. (C) and BEC cells. (D) Schematic representation of miRNA16a transfection and BCoV infection experiments. Transfection of miR-Scr and, miRNA16a, and antagomir-16a into the MDBK and the BEC cells, followed by infection with (MOI = 1) of BCoV enteric and respiratory isolates for 48 to 72 h and subsequent sample collection for further analysis. (E) qRT-PCR data showing the expression pattern of bovine miRNA16a in scrambled- and miRNA16a-transfected MDBK cells. (F) and BEC cells. (G) qRT-PCR data showing the expression pattern of bovine miRNA16a in scrambled- and Antagomir-16a-transfected MDBK cells. (F) and BEC cells. The heatmap was generated using https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en, a free online data analysis and visualization platform. All the qRT-PCR experiments were performed in triplicate. All the miRNA expression was normalized with two endogenous controls (U6 and 5S). The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

The bovine Furin gene is a novel target for the bovine miRNA16a

Bioinformatics search for the potential miRNA16a target genes and the impacts of the miRNA16a over expression on the host cell Furin on the mRNA and protein levels

We used several in silico prediction tools to identify some potential host gene targets for the bovine miRNA16a. Results from the “TargetScan” online bioinformatics tool revealed that miRNA16a could target the 3’UTR of the bovine host cell Furin (Fig. 3A). The miRNA16a target region within the 3’UTR of the bovine Furin is conserved across different mammalian species, including humans and mice (Fig. 3B). Our results show a marked inhibition of host cellular Furin gene and protein expression levels after the transfection with the miRNA-16 pri-miRNA. The expression level of the mRNA of host cellular Furin was downregulated by up to 70% in the miRNA16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr-transfected cells in the case of the MDBK cells (Fig. 3C). The Furin protein expression level was downregulated by approximately 30% in the case of the miRNA16a-transfected cells compared to the miR-Scr-transfected MDBK cells (Fig. 3D, E). In the case of the BECs, approximately 35% downregulation of the host Furin mRNA expression was observed in the miRNA16a-transfected cells (Fig. 3F). Meanwhile, the expression level of the Furin protein was downregulated by approximately 50% in the case of miRNA16a-transfected BEC cells (Fig. 3G, H).

Fig. 3.

The host Furin as a potential novel target for the bovine miRNA16a. (A) In silico prediction of miRNA16a targeting the 3’ UTR of the host cell Furin. The context + + score percentile represents the binding energy of the miRNA with the target gene. (B) Multiple sequence alignment shows that the miRNA16a/Furin binding region (indicated in the red color font boxes) is conserved among eight species, including humans, mice, and bovines. (C) The MDBK cells were transfected with either miR-Scr or miRNA16a, followed by BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp infection. After 72 h, the samples were subjected to qRT‒PCR. (D) Western blot analysis of host Furin protein expression in the MDBK cells in the miR-Scr- and miRNA16a-transfected groups. (E) Western blot band density of Furin protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (F) The BEC cells were transfected with scrambled and miRNA16a, followed by BCoV enteric and respiratory isolate infection. After 72 h, samples were collected for the qRT-PCR analysis to assess the mRNA expression level of the host Furin in both the scrambled- and miRNA16a-transfected groups. (G) Western blot analysis of host Furin protein expression in the scrambled- and miRNA16aa-transfected groups of BEC cells. (H) Western blot band density of Furin protein normalized to that of β-actin in BECs. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

Application of the miRNA16a antagomir restored the expression levels of the host cell bovine Furin in the MDBK and BEC cells

To confirm the target specificity of the miRNA16a binding to bovine Furin, the miRNA16a antagomir was transfected into the MDBK cells, and host cellular Furin expression was assessed. Cells transfected with miRNA16a antagomir have higher expression levels of Furin compared to the miRNA16a transfected cells. Meanwhile, there were no significant changes observed in the mRNA and protein levels of host Furin between the AntagomiR-16a-transfected and miRNA-Scr-transfected groups, suggesting that Antagomir-16a restored host Furin expression close to its normal cellular levels (Fig. 4A–C).

Fig. 4.

Validation of the host cell furin as a functional target for the host cell miRNA16a. (A) The MDBK cells were transfected independently with either miR-Scr or Antagomir-16a, followed by BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp infection. After 72 h of transfection, the collected samples were subjected to qRT-PCR to evaluate the host cell furin mRNA expression levels. (B) Western blot analysis of host Furin protein and β-actin expression in the MDBK cells in the miR-Scr- and Antagomir-16a-transfected groups. (C) Western blot band density of Furin protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (D) The results of the dual-luciferase reporter assay. HEK cells were transfected with different combinations of the Furin 3’UTR (WT) or mutant (Mut) plasmid or vector only (pmir-GLo) with miRNA16a, Antagomir-16a, and miR-Scr, as indicated. The dual luciferase assay was conducted, and the relative luciferase activity was calculated using red firefly luciferase signals as a normalization control for the green Renilla luciferase signals. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Validation of bovine Furin as a novel target for the miRNA16a

To further validate Furin as a potential novel target of the bta-miRNA16a, the dual-luciferase reporter plasmid carrying the 3’UTR of Furin containing the binding region of bta-miRNA16a was designed and synthesized (Fig. S3A). To further validate the mirRNA16a/Furin targeting, we generated some mutants to scramble the miRNA16a target region, particularly the miRNA16a seed region in the 3’UTR of the Furin, using site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. S3A). The successful insertion of the wild-type 3’UTR of Furin and the mutant constructs was validated by double digestion with the XhoI and SacI restriction enzymes, followed by gel-based PCR and sequencing of these constructs (Fig. S3B, S3C). The wild-type and mutant pmirGLO luciferase constructs were co-transfected with the miRNA16a and the Antagomir-16a and scrambled miRNA into the HEK293 cells. The dual-luciferase assay revealed that co-transfection of wild-type Furin with miRNA16a significantly reduced the relative luciferase activity by more than 60% compared to that in cells co-transfected with miRNA-Scr and wild-type Furin or miRNA16a co-transfected with mutated Furin construct (Fig. 4D). Wild-type Furin with miRNA16a showed more than a 50% reduction in luciferase activity compared to cells co-transfected with Antagomir-16a and wild-type Furin or with mutated Furin (Fig. 4D). These results confirmed that miRNA16a is a novel target for the host cellular Furin.

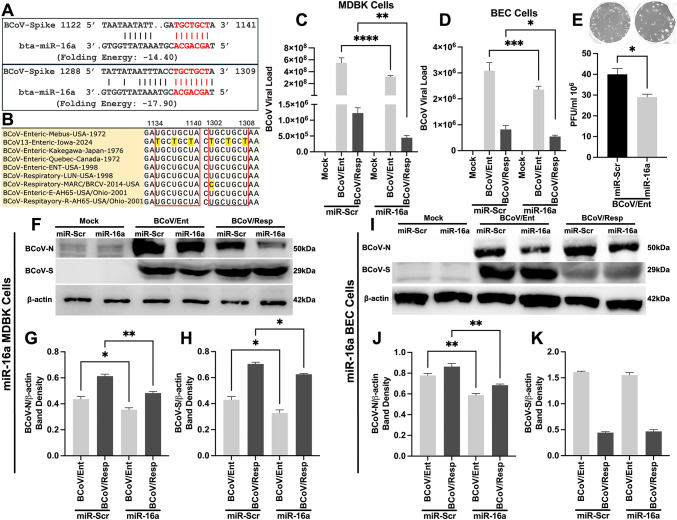

The bovine miRNA16a inhibits BCoV replication on viral genome copy numbers, proteins, and viral infectivity levels

In silico analysis showed that miRNA16a has multiple targeting sites across the BCoV genome, including two targets within the BCoV-spike glycoprotein (Fig. 5A). These miRNA16a binding sites are conserved among BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp isolates, which confirms the specificity of miRNA16a targeting the viral genome of either the enteric or respiratory isolates of BCoV (Fig. 5B). To further validate the miRNA16a/BCoV/S target prediction, the miRNA16a was independently transfected into the MDBK and the BEC cells, which were subsequently infected with either the BCoV/Ent or the BCoV/Resp in parallel with the miRNA-Scr. The qRT-PCR analysis revealed marked inhibition of BCoV genome expression in the miRNA16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr-transfected MDBK and BEC cells (Fig. 5C, D). The viral plaque assay results revealed a 1.24-fold reduction in the BCoV infectivity in the miRNA16a-transfected cells (Fig. 5E). The western blot analysis showed significant inhibition of the BCoV-Nucleocapsid (BCoV-N) and BCoV-Spike (BCoV-S) proteins after miRNA16atransfection and BCoV infection in the MDBK cells (Fig. 5F–H). The BEC cells showed a prominent inhibition of BCoV-N and BCoV-S protein expression levels (Fig. 5I–K). These findings suggest that miRNA16a targets the spike protein of BCoV and restricts BCoV replication.

Fig. 5.

The overexpression of the bovine miRNA16a inhibited BCoV replication on the viral genome copy numbers and the viral infectivity levels. (A) In silico prediction of miRNA16atargeting the BCoV spike gene at two different sites. The folding energy represents the binding energy of the miRNA with the target region. (B) Multiple sequence alignment shows that the miRNA16a/Spike binding region (indicated in red box) is conserved among nine different BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp isolates. (C) qRT-PCR analysis demonstrating the genome viral load of BCoV in scrambled- and miRNA16a-transfected MDBK cells. (D) qRT-PCR analysis illustrating the genome viral load of BCoV in scrambled- and miRNA16a-transfected BEC cells. (E) Viral plaque assay indicating the infectivity level of the BCoV enteric isolate in scrambled- and miRNA16a-transfected MDBK cells. (F) Western blot analysis of BCoV-nucleocapsid (BCoV-N) and BCoV-spike (BCoV-S) in the MDBK cells transfected with scrambled or miRNA16a. (G) Western blot band density of the BCoV-N protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (H) Western blot band density of the BCoV-S protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (I) BEC cells were transfected with miRNA-Scr and miRNA16a, and western blot analysis was used to assess the protein expression of BCoV-N and BCoV-S. (J) Western blot band density of BCoV-N protein normalized to that of β-actin in BEC cells. (K) Western blot band density of BCoV-S protein normalized to that of β-actin in BEC cells. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

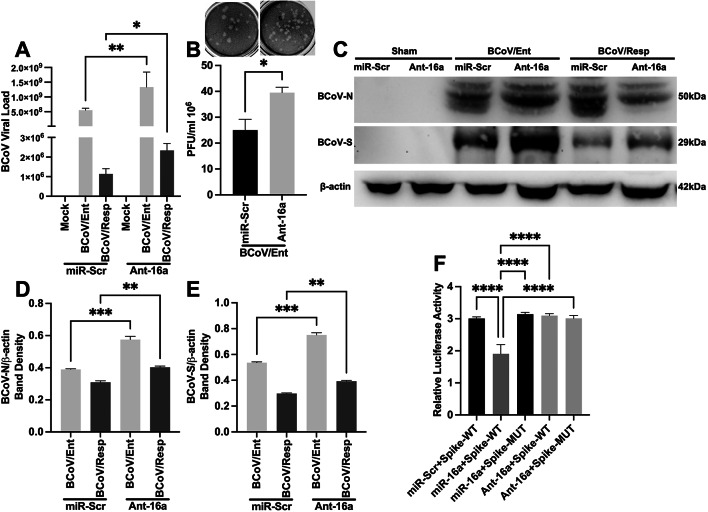

Downregulation of the host cell miRNA16a expression by the antagomir-16a enhanced BCoV replication

To further confirm the mechanism of actions of the host miRNA16a targeting the host cell Furin during the BCoV replication, we used the Antagomir-16a during BCoV infection. The qRT-PCR results showed significant enhancement of the BCoV genome copy numbers in the Antagomir-16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr-transfected cells (Fig. 6A). The viral plaque assay results revealed up to a 60% increase in the BCoV titers in the Antagomir-16a-transfected group of cells (Fig. 6B). The expression levels of both the BCoV-N and the BCoV-S proteins were significantly increased in the case of the antagomir-16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr-transfected cells (Fig. 6C–E). Furthermore, to validate the binding of bovine miRNA16a to the BCoV-Spike, a dual-luciferase reporter plasmid containing both miRNA16a target sites in the BCoV-Spike targeting miRNA16a was designed and synthesized (Fig. S4A). The construct containing the scrambled miRNA16a/BCoV/S target sites was designed and generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. S4A). The successful insertion of the BCoV-Spike wild-type and the mutant construct was validated by double digestion with the XhoI and SacI restriction enzymes, followed by gel-based PCR and nucleotide sequencing (Fig. S4B, S4C). The wild-type and mutant pmirGLO luciferase constructs with BCoV-Spike were co-transfected with miRNA16a and Antagomir-16a and scrambled miRNA into HEK293 cells. The dual-luciferase assay revealed that co-transfection of wild-type BCoV-Spike with miRNA16a reduced the relative luciferase activity by 40% compared to miRNA-Scr. In the case of the wild-type BCoV-Spike or miRNA16a co-transfected with mutated BCoV-Spike (Fig. 6F). Wild-type BCoV-Spike with miRNA16a showed a 40% reduction in luciferase activity compared to the antagomir-16a and wild-type or mutated BCoV-Spike (Fig. 6F). These results confirmed that miRNA16a effectively targets the BCoV-Spike glycoprotein.

Fig. 6.

Impact of Antagomir-16a on BCoV replication. (A) qRT-PCR analysis illustrating the genome viral load of BCoV in miR-Scr- and AntagomiR-16a-transfected MDBK cells. (B) Viral plaque assay indicating the infectivity level of the BCoV enteric isolate in miR-Scr- and Antagomir-16a-transfected MDBK cells. (C) Western blot analysis of BCoV-N and BCoV-S in the MDBK cells transfected with miR-Scr or Antagomir-16a. (D) Western blot band density of the BCoV-N protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (E) Western blot band density of the BCoV-S protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (F) The results of the dual-luciferase reporter assay. HEK cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant BCoV-Spike or empty vector (pmir-GLo) with miRNA16a, Antagomir-16a, and miR-Scr, as indicated. The dual luciferase assay was conducted, and the relative luciferase activity was calculated using red firefly luciferase signals as a normalization control for the green Renilla luciferase signals. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

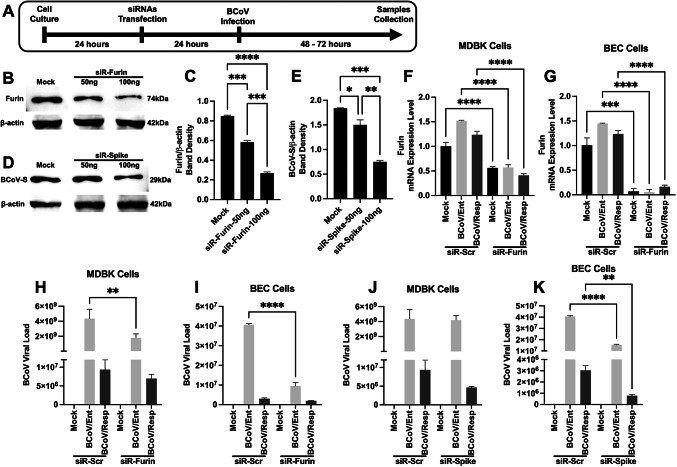

The siRNA targeting the miRNA16a binding sites in the BCoV-S glycoprotein and the host Furin inhibits BCoV replication at the viral genome copy numbers and the viral proteins expression levels

We designed two sets of siRNA molecules targeting the BCoV-S protein and the cellular host cell Furin to confirm the impacts of the bovine miRNA16a on the BCoV replication. The first siRNA molecule was designed to target the miRNA16a target site within the BCoV-Spike glycoprotein. The second siRNA molecule was designed to target the miRNA16a in the 3’UTR of the host cell Furin. The MDBK and BEC cells were transfected independently with these siRNA molecules, followed by independent infection with either the BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp isolates. Samples were collected after 72 hpi for subsequent analysis (Fig. 7A). The viability of the used cells in this experiment was assessed before and after transfection of both siRNA molecules in the MDBK and the BEC cells to confirm the cell integrity (Fig. S1A, S1B, S5A–S5F). The MDBK cells were transfected with different concentrations of siRNAs (50 ng or 100 ng). The results revealed a gradual reduction in the Host cell Furin protein expression levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B, C). Similarly, the BCoV-spike protein expression levels exhibited a similar decrease in their expression levels with the increase of the concentration of the designed BCoV/siRNA-spike molecules described above (Fig. 7D, E), confirming the specificity of the designed siRNA molecules in the inhibition of the protein expression levels of the BCoV-S and the host cell Furin. The mRNA expression level of the host cell Furin was also significantly lower in the Furin-siRNA-treated cells compared with the Sc-siRNA-treated MDBK cells and BEC cells. cells (Fig. 7F, G). Following the silencing of Furin and BCoV/S, we examined their impact on BCoV replication. The results revealed at least 58% (≈2.39-fold) inhibition in the BCoV at the genome copy numbers in the case of the siRNA-Furin-transfected MDBK cells (Fig. 7H). In the case of the BEC cells, the inhibitory effects of the designed siRNAs were even more pronounced, with approximately 75% (≈4.26-fold) inhibition at the BCoV genomic copy numbers (Fig. 7I). In the case of the MDBK, cells transfected with the siRNA/BCoV-S showed inhibition in the BCoV genome copy numbers in both the BCoV/Ent and the BCoV/Resp infected cells (Fig. 7J). In the case of the BEC cells, the siRNA/BCoV-S glycoprotein resulted in approximately 61% (≈2.61-fold) inhibition of BCoV/Ent and approximately 74% (≈3.85-fold) inhibition of BCoV/Resp in the BEC cells (Fig. 7K).

Fig. 7.

The impacts of silencing the host Furin and BCoV-S glycoproteins by specifically designed siRNA molecules on the BCoV replication. (A) Schematic representation of the siRNA transfection BCoV infection experiments: the transfection process of the scrambled-siRNA, siRNA-Furin, and the siRNA-BCoV-S glycoproteins into the MDBK the BEC cells was illustrated, followed by infection with independent BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp isolates infection in these cells for 72 h and subsequent sample collection for further analysis. (B) The MDBK cells were transfected with 50 ng or 100 ng of the siRNA-Furin, followed by western blot analysis of Furin protein expression levels. (C) Western blot band density of the Furin protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (D) The MDBK cells were transfected with 50 ng or 100 ng of siRNA BCoV/-S, followed by western blot analysis of BCoV/S protein expression. (E) Results of the western blot band density of the BCoV/S glycoprotein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (F) The qRT-PCR results show the Furin mRNA expression levels in the scrambled siRNA- and the siRNA-Furin-transfected MDBK cells (G) and BECs. (H) The qRT-PCR results analysis shows the genome copy numbers of the BCoV in the cases of the scrambled-siRNA and the siRNA-Furin-transfected MDBK cells (I) and BEC cells. (J) The qRT-PCR analysis results show the genome copy numbers of the BCoV in the case of the scrambled-siRNA and siRNA-BCoV/Spike-transfected MDBK cells (K) and the BEC cells. The data of all the experiments represent at least three biological repeats. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

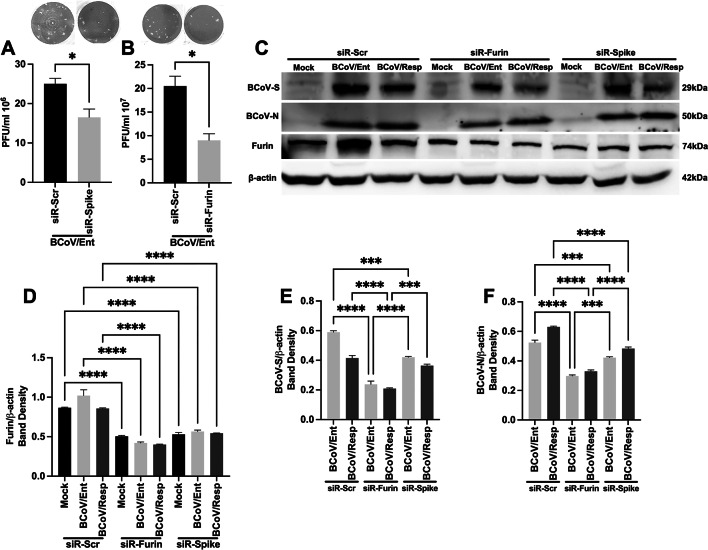

Applying siRNA/BCoV-S glycoprotein and the siRNA/host cell-Furin inhibited the expression of BCoV proteins and BCoV infectivity in bovine cells

The viral plaque assay and the western blot were conducted to evaluate the impacts of siRNA-Furin and siRNA/BCoV-spike glycoproteins on the protein expression and on the viral infectivity levels of the BCoV. Following transfection with siRNA-Furin and siRNA-BCoV-spike, the MDBK cells were infected with BCoV, and cell lysates were used to assess BCoV inhibition at the protein expression levels, particularly the BCoV/S and BCoV/N. The results showed a marked reduction of approximately 1.47-fold in the protein expression levels of the BCoV enteric isolate after silencing BCoV/S glycoproteins (Fig. 8A). Silencing of the host cellular Furin in MDBK cells resulted in an approximately 1.9-fold decrease in BCoV infectivity (Fig. 8B). In MDBK cells, Furin protein expression decreased by approximately 50% after silencing the host Furin and by approximately 42% after silencing the BCoV spike glycoprotein (Fig. 8C, D). There was approximately 2.5-fold inhibition of the BCoV-spike protein in the siRNA-Furin group and approximately 1.38-fold in the siRNA-spike-transfected group compared to the scrambled group (Fig. 8C, E). In the host Furin-silenced group, the BCoV nucleocapsid protein was inhibited approximately (1.79 and 1.97) folds in the BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp-infected cells, respectively (Fig. 8C, F). Silencing of the BCoV/S glycoprotein inhibited the BCoV nucleocapsid protein expression levels by approximately 1.24-fold and 1.31-fold in the BCoV/Ent- and BCoV/Resp-infected cells, respectively (Fig. 8C, F). Notably, the downregulation of BCoV/S, BCoV/N, and host cell Furin was consistent in the mock and BCoV-infected cells, indicating that siRNA-spike and siRNA-Furin inhibit protein production at the posttranscriptional level, independent of BCoV infection.

Fig. 8.

Silencing of the host cell Furin protein and the BCoV-S glycoprotein negatively impacted BCoV infectivity in bovine cells. (A) The viral infectivity of the BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp was markedly inhibited in cells transfected with siRNA-BCoV/S or (B) the siRNA-Furin, as measured by the viral plaque assay. The plaque-forming units (PFUs) were used to determine the viral titer in each virus-infected group. (C) The MDBK cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (Scr-siRNA), siRNA-Furin, or siRNA BCoV/-Spike, followed by infection with either the BCoV/Ent or the BCoV/Resp. Cells were lysed after 72 hpi, and western blot analysis was performed to observe the protein expression of the BCoV-S, the BCoV-N, and the host cell Furin proteins expression. (D) Western blot band density of the Furin protein, (E) BCoV spike protein, and (F) BCoV-N protein was normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. The data of all the experiments represent at least three biological repeats. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

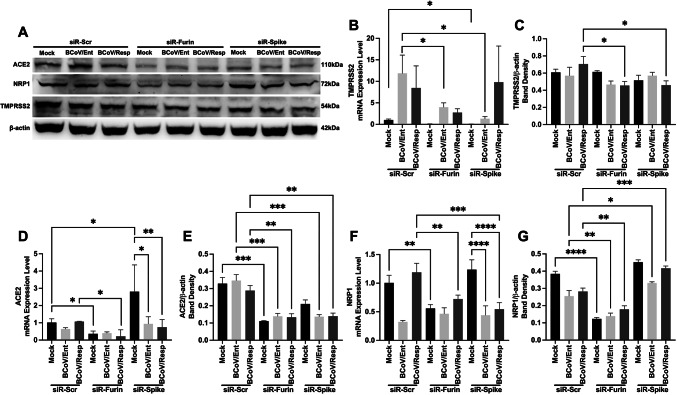

The bovine miRA-16a modulates the expression levels of several essential coronavirus replication-related proteins (ACE2, NPR1, TMPRSS2) during BCoV replication

Herein, we evaluated the potential effects of the host cell miRNA16a on other host cell surface receptors involved in infections caused by other coronaviruses, particularly severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The MDBK cells were transfected with miRNA-Scr and miRNA16a. The mRNA and protein expression levels of several selected host cell proteins were monitored (Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2), and neuropilin-1 (NRP1)) were measured. The results revealed that ACE2 protein expression was inhibited by approximately 22% in the miRNA16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr-transfected cells (Fig. 9A, C). In the case of the miRNA16a-transfected cells, the ACE2 mRNA was downregulated by 50% after BCoV infection (Fig. 9B). The host NRP1, mRNA, and protein expression levels were markedly upregulated after the BCoV infection in the case of the miRNA-Scr-transfected cells but decreased in the case of the miRNA16a-transfected cells, particularly after BCoV infection (Fig. 9A, D, E). The mRNA expression levels of the TMPRSS2 were also downregulated after BCoV infection in the case of the miRNA16a-transfected group of cells (Fig. 9F); however, there were no significant changes observed in protein expression levels between the miRNA-Scr- and miRNA16a-transfected cells (Fig. 9A, G).

Fig. 9.

The impacts of the overexpression of the host miRNA16a on the expression levels of some other coronavirus replication-related proteins (ACE2, NRP1, and TMPRSS2). (A) The MDBK cells were transfected with either Scr-miRNA or miRNA16a, followed by the infection with either the BCoV/Ent or the BCoV/Resp isolates. The cell culture supernatants and cell lysates from all treated group cells were collected at 72 hpi for qRT-PCR and western blot analysis of host ACE2, NRP1, TMPRSS2, and β-actin. (B) Results of the qRT-PCR analysis of host ACE2 mRNA expression in the Scr-miRNA- and miRNA16a-transfected cells. (C) Results of the Western blot band density of the ACE2 protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (D) Results of the qRT-PCR analysis of host NRP1 mRNA expression levels in various groups of cells. (E) Results of the Western blot band density of the NRP1 protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. (F) Results of the qRT-PCR analysis of host TMPRSS2 mRNA expression levels. (E) Results of the western blot band density of the TMPRSS2 protein normalized to that of β-actin in the MDBK cells. The data of all the experiments represent at least three biological repeats. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

The miRNA-16 targeting the host cell Furin could potentially contribute to the host/BCoV evasion strategies through the modulation of some important host cell proteins involved in the replication of some other related coronaviruses

To further explore the roles of the host cell Furin during BCoV replication, two siRNAs were designed to inhibit BCoV replication by targeting the BCoV/S glycoproteins and the miRNA-16 target sites within the 3’UTR of the host cell Furin. The siRNA-BCoV-S and the siRNA-Furin were transfected into MDBK cells, and the mRNA and protein expression levels of the host ACE2, TMPRSS2, and NRP1 were assessed using the qRT-PCR and Western blotting with the relevant primers and antibodies, respectively. Results of the mRNA expression levels of the TMPRSS2 were downregulated in the case of the BCoV/Ent cells initially transfected with the siRNA-Furin and the siRNA-BCoV-S (Fig. 10B). The TMPRSS2 protein expression levels were only downregulated in the case of the BCoV/Resp cells initially transfected with the siRNA-Furin and the siRNA-BCoV-S independently (Fig. 10A, C). The host ACE2 mRNA and protein expression levels were significantly downregulated after transfection with the siRNA-Furin (Fig. 10A, D, E). The ACE2 protein expression levels were downregulated in the siRNA-BCoV/S-transfected cells only after BCoV infection (Fig. 10A, D, E). The NRP1 mRNA and the protein expression levels were similarly downregulated in the case of the siRNA-Furin-transfected group. Still, they were downregulated only after BCoV infection in the siRNA-spike-transfected group (Fig. 10A, F, G). The mRNA expression levels of both ACE2 and NRP1 were decreased after BCoV infection in the siRNA-BCoV-S-transfected cells, suggesting their involvement in the process of BCoV replication. These findings mirror the outcomes of miRNA16a transfection in the same bovine cell lines, suggesting a direct correlation between ACE2 and NRP1 expression and host Furin expression. In contrast, TMPRSS2 appears to function independently of the host cell Furin during BCoV infection.

Fig. 10.

Silencing of the host cell Furin and BCoV-S glycoproteins impacted the expression levels of some other coronavirus replication-related proteins (ACE2, NRP1, and TMPRSS2) which further impacted BCoV/Ent/BCoV/Resp replication. (A) The MDBK cells were transfected with Scr-siRNA control, siRNA-Furin, or siRNA BCoV/Spike glycoprotein, followed by the infection with either BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp. Cell lysates were collected after 72 hpi and subjected to Western blot analysis to assess the protein expression levels of the bovine (ACE2, NRP1, TMPRSS2, and bovine β-actin) proteins. (B) Results of the qRT-PCR analysis of bovine TMPRSS2 mRNA expression levels in the case of the siRNA-Scrambled-, the siRNA-Furin-, or the siRNA-BCoV-S transfected MDBK cells. (C) Results of the analysis of the western blot band densities of the TMPRSS2 protein expression normalized to that of bovine β-actin protein. (D) Results of the qRT-PCR analysis of bovine ACE2 mRNA expression levels. (E) Results of the western blot band densities of the ACE2 protein normalized to that of β-actin. (F) Results of the qRT-PCR analysis of bovine NRP1 mRNA expression. (G) Results of the western blot band densities of the NRP1 protein expression levels normalized to that of β-actin. The data of all the experiments represent at least three biological repeats. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

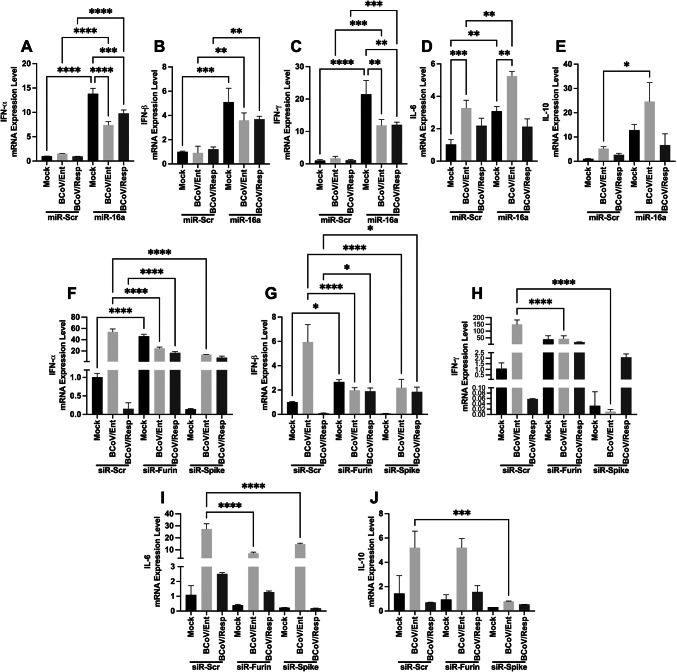

The miRNA-16 overexpression in some bovine cells enhances the host cell cytokine gene expression during BCoV infection

We studied the impact of miRNA16a on the expression levels of host cell cytokines during BCoV infection. The MDBK cells were transfected with the miRNA16a, the siRNA-Furin, and the siRNA of the BCoV-S. The mRNA expression levels of some common host cell cytokines (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-10) were measured by qRT-PCR using the designed primers listed in (Table 2). The results showed significant upregulation of the (IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ) expression levels in the miRNA16a-transfected cells compared to the miRNA-Scr-transfected cells (Fig. 11A–C). The mRNA expression levels of the host (IL-6 and IL-10) were upregulated in the case of the miRNA16a-transfected cells, particularly post-BCoV/Ent infection (Fig. 11D, E). Moreover, the (IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ) expression levels were downregulated in the siRNA-Furin- and siRNA-spike-transfected cells (Fig. 11F–H). Although the expression levels of IL-6 and IL-10 were upregulated in the siRNA-Furin and siRNA-BCoV-S transfected cells after the BCoV/Ent infection, the overall expression levels were lower than those in the siRNA-Scr-transfected cells (Fig. 11I, J).

Fig. 11.

Activation of the host cell cytokine-like Strome upon miRNA16a overexpression during BCoV infection in bovine cells. The MDBK cells were transfected with either Scr-miRNA or miRNA16a, followed by infection with BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp. The results. Results of the qRT-PCR analysis to quantify the mRNA expression of (A) IFN-α; (B) IFN-β; (C) IFN-γ; (D) IL-6; (E) and IL-10. (F) The MDBK cells were transfected with Scr-siRNA control, siRNA-Furin, or siRNA-BCoV-Spike, followed by BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp infection. The qRT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expression levels of IFN-α, (G) IFN-β, (H) IFN-γ, (I) IL-6, (J) and IL-10. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The significance of the data was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

Discussion

BCoV is an endemic viral pathogen in some cattle herds worldwide, including in the USA34. The virus has dual respiratory/enteric tissue tropism6. The mechanisms governing this dual tropism have not yet been well studied. Viral receptors and other host cell proteases may partially explain this dual tropism; however, many aspects of the BCoV/host interaction, including their tissue tropism, have not yet been studied. However, the availability of viral receptors and some other host enzymes are not the sole agents that govern the success of viral replication or fully explain viral tropism. MicroRNAs are small RNA molecules that regulate host genes at the posttranslational level. Previous studies have shown that host miRNAs regulate the gene expression of many host proteins during viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2. Several host cell miRNAs, including miRNA-(155, 221, and 146a), can act as biological markers for SARS-CoV-2 infection; they also play essential roles in regulating inflammatory responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans35,36. However, the role of host cell miRNAs has not been extensively studied in the context of BCoV infection. This study aimed to determine some host miRNAs’ roles in BCoV replication, tissue tropism, and immune regulation/evasion. Our recent in silico prediction and bioinformatics search studies revealed that several host miRNAs could play essential roles in BCoV replication and at least partly explain the dual tropism of BCoV infection37. In this study, we focused on the function of beta-miRNA16a, which shows some differential expression profiles during the replication of either enteric or respiratory isolates of BCoV. The miRNA16a was selected in this study based on several parameters. (1) The differential expression profiles of miRNA16a observed between the BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp isolates. Specifically, the miRNA16a expression level was downregulated in the BCoV/Ent infected hosts while upregulated in the BCoV/Resp infected hosts. This unique expression profile of miRNA16a makes it a suitable genetic marker for BCoV infection in cattle. (2) The miRNA16a expression profile data presented in Fig. 2A were initially reported using the NGS approach and subsequently confirmed by the qRT-PCR using specific primers in the MDBK and the BEC cells. The miRNA16a expression profiles were consistent among all tested cells and with the NGS data. (3) The higher replication and infectivity associated with BCoV/Ent infection in the tested models suggests that the downregulation of miRNA16a may be associated with the severity of BCoV/Ent infection. This contrasted with the upregulation of the miRNA16a expression observed in the case of the BCoV/Resp infected groups. (4) The miRNA differential expression levels reported among the Ent/Resp isolates of the BCoV imply a possible role of the miRNA16a in modulating the BCoV tissue tropism and pathogenesis. This study showed that the host cell miRNA16a targets the host cell Furin and inhibits BCoV replication. On the other hand, silencing these miRNA16atarget sites in the host cell Furin and the BCoV-S resulted in the marked inhibition of the BCoV replication. Therefore, the host miRNA16a could be a therapeutic target for BCoV infections in cattle by targeting the host Furin and/or the BCoV spike glycoprotein. The miRNA/coronavirus interaction revealed some insights into the roles of these small RNA molecules in fine-tuning virus replication and immune regulation. It was predicted that the ability of hsa-miRNA-miR-8066 to target the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein leads to the inhibition of viral replication38. Other studies have shown that at least seven host miRNAs hsa-miRNA-(15a, 298, 497, 508, 1909, and 3130) target the SARS-CoV-2-S glycoprotein at various locations, leading to substantial inhibition of virus replication39. The candidates of the host miRNA-16 family are involved in many cellular processes, including cell cycle arrest, tumor research, and immune regulation, particularly the TGFβ pathway, and they are also used as diagnostic and prognostic markers for cancer research40–45. Recent studies have shown that host miRNA-16-2-3p could be an excellent prognostic marker for SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans46. However, the roles of bta-miRNA16a in BCoV replication and immune regulation have not yet been studied.

Some coronaviruses, including Betacoronaviruses, use host cell serine protease-2 (Furin) to cleave the spike glycoprotein at the PRRAR motif47. Furin/CoV/S targeting plays an important role in CoV tissue tropism and molecular pathogenesis48. Cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein is an essential step in virus replication. Transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) cleaves SARS-CoV-2-S, and another enzyme called Furin (another serine protease-2) is responsible for the proteolysis of the spike glycoprotein into the S1 and S2 domains49. These two simultaneous cleavage events are essential for the replication of most coronaviruses, particularly during the entry of the virus into host cells. To further confirm and consolidate this phenomenon, other researchers have shown that deleting Furin cleavage sites from SARS-CoV-2-S substantially decreases virus replication and impacts downstream viral pathogenesis and tissue tropism50,51. Our data revealed differential expression of miRNA16ain BCoV/Ent- and BCoV/Resp-infected MDBK and the BEC cells (Fig. 2B, C). There was a marked downregulation of the miRNA16aexpression profile, especially in the case of BCoV/Ent-infected cells. Thus, we believe that the host responded to BCoV/Ent infection by downregulating bta-miRNA16a, which targets the 3’UTR of the host cell Furin. This miRNA16atargeting Furin inhibited BCoV replication at the genome copy number level, as measured by qRT‒PCR; at the viral protein level, including the BCoV/S and BCoV/N proteins; and at the virus infectivity level, as shown by plaque assays (Fig. 5C‒K). These data are consistent with SARS-CoV-2 loss of Furin cleavage sites, which led to marked inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication50.

Several approaches, including bioinformatics, western blot, and dual luciferase assays, have been used to validate several genes as targets for candidate miRNAs, including the use of a dual luciferase assay on a potential gene 3’UTR construct carrying the seed region of the target miRNA. The comparison between the luciferase activity of the mutated 3’UTR construct of the miRNA target gene and that of the wild-type construct carrying the seed region of the same miRNA candidate was used extensively as a benchmark for miRNA/gene target validation8,28,29. Our bioinformatic analysis of bta-miRNA16a revealed that the seed region of this miRNA is highly conserved among the Furin 3’UTRs of several species of animals, including humans and bovine species (Fig. 3B). Our results showed that Furin protein expression was lower in the MDBK and the BEC cells transfected with miRNA-16 than in those transfected with scrambled miRNA (Fig. 3C–G). The dual luciferase assay results showed marked inhibition of luciferase activity in cells transfected with the bta-miRNA-16a 3’UTR wild-type construct (Fig. 4D). Thus, Furin is considered a novel target of bta-miRNA-16a.

Our data clearly showed that infection with both BCoV/Ent and BCoV/Resp inhibited interferon (α, β, and λ) production (Fig. 11A–C). However, the overexpression of miRNA16a enhanced cytokine gene expression (Fig. 11A–C). It was previously shown that the BCoV-N protein inhibits IFN-β production via the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) pathway52. This confirms our findings about the dual actions of bta-miRNA16ain inhibiting BCoV infection and enhancing the host immune response to counteract viral infection. While miRNA16a does not directly interact with the host IFN pathways, its overexpression could influence the host’s innate immune response through an indirect mechanism. These effects may involve other pathways or other cellular host factors that modulate cytokine expression in response to BCoV infection. Further studies are needed to explore these potential indirect effects and their relevance to the miRNA16a roles in cattle’s immune regulation during BCoV infection. One of the approaches to confirm the action of certain miRNAs on their target genes is to use siRNAs to inhibit the same miRNA target region within these genes. To verify the ability of bta-miRNA16a to target the host cell Furin and the BCoV-S glycoprotein, we designed two independent siRNAs to target the indicated regions. Our plaque assay data showed that the application of siRNA-Furin and siRNA-S substantially inhibited BCoV replication in the MDBK and the BEC cells in terms of genome copy number, protein (S and N) expression, and virus infectivity (Figs. 7, 8). Our data are very much consistent with other research on other coronaviruses (CoVs), particularly SARS-CoV-2. Applying siRNAs targeting the SARS-CoV-2/S glycoprotein subsequently significantly inhibited the virus replication53. Similarly, Furin inhibitors led to marked inhibition of SARS-CoV-2, a promising antiviral therapy for SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans54,55.

In addition to host ACE2, several alternative host surface receptors have been suggested to promote coronavirus infection in host cells. The alternative receptors for ACE2 in coronavirus infection include neuropilin-1 (NRP1)4,56 and CD147, a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in epithelial and immune cells57,58. In most coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, the spike protein undergoes two proteolytic cleavage steps after binding to ACE2. The first cleavage occurred at the S1–S2 boundary and was cleaved by the host cell Furin. Virus entry still requires a second cleavage by host cell proteases at the S2 region, which is mostly performed by TMPRSS22. In case of SARS-COV-2 infection, when the host cells have a low-level TMPRSS2 expression level or if the SARS-CoV-2-ACE2 complex does not bind to the TMPRSS2, the complex is taken into the cell by clathrin-mediated endocytosis into the endo-lysosomes, where the SARS-CoV-S2 protein is cleaved by cathepsins enzyme59,60. The present study showed that the miRNA16a inhibits the host cell Furin expression. Similarly, the inhibition of the host cell Furin by specific siRNA-Furin resulted in a marked downregulation in the expression levels of both the ACE2 and the NRP1 on both the mRNA and protein expression levels (Fig. 10). However, there were no detectable impacts on the TMPRSS2 expression levels at the genomic or protein levels (Fig. 10A–C). These findings suggest that miRNA16a downregulates the expression levels of the bovine host Furin, potentially inhibiting the host ACE2 and NRP1 expression levels. Conversely, the TMPRSS2 may compensate for these inhibitory effects of bta-miRNA16a on Furin through an alternative regulatory mechanism to rescue BCoV infection in host cells following Furin and ACE2 inhibition. IL6 plays key roles in the regulation of the replication of some CoVs, particularly SARS-CoV-2, and in the modulation of the immune response61. SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers robust IL6 production, which induces a cytokine storm62. Similarly, BCoV infection, particularly infection with the BCoV/Ent isolate, upregulated the expression of IL6 (Fig. 11D). Furthermore, miRNA16atreatment increased IL6 expression in cells transfected with miRNA16aand infected with the BCoV-Ent isolate compared to that in the Scr-miRNA-transfected cells and infected with the BCoV/Ent isolate (Fig. 11D). These findings demonstrate that bta-miRNA16aoverexpression significantly activates the host cytokine response. Moreover, the prevalence of BCoV/Ent infection leads to elevated expression of host cytokines and interferons. Previous studies have shown that the miRNA-16 family is involved in cell cycle control, cell survival, and apoptosis pathways43. This miRNA also controls the balance between cell survival and apoptosis. Our data show that miRNA16a enhances cell survival in transfected cells infected with BCoV/Ent or BCoV/Resp compared to those infected with Scr-miRNA mimics (Fig. S1A–S1F). These data could also be supported by the marked activation of host cytokine gene expression, as shown in “The miRNA-16 overexpression in some bovine cells enhances the host cell cytokine gene expression during BCoV infection” section). Thus, the high stimulation of cytokines and the limitation of the CPE observed in the bta-miRNA16a-transfected group of cells infected with BCoV contributed to the marked inhibition of virus replication. Consistent with these findings, cells treated with siRNA-BCoV-S showed less CPE than did the same type of cells transfected with the miRNA-Scr mimics.

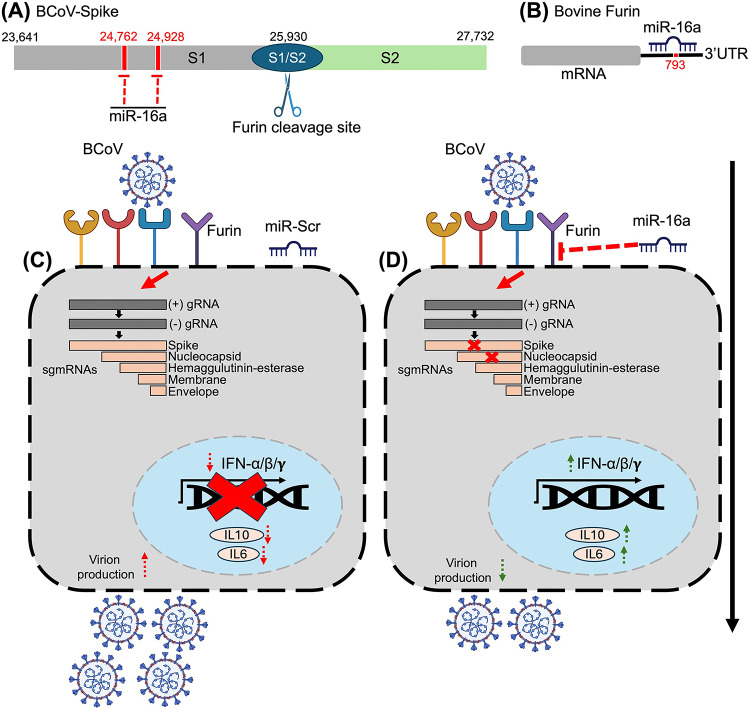

In summary, bta-miRNA16a plays dual roles in the restriction of BCoV replication by targeting the spike glycoprotein and the host cell Furin. This bta-miRNA16a/viral/host gene targeting inhibited BCoV replication. It also stimulated the production of some host cytokines, which contributed substantially to cell survival in the bta-miRNA-16-transfected cells compared to the Scr-miRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

The proposed model of the mechanism of the dual actions of the host cell miRNA16a in restricting BCoV replication through targeting the BCoV-S glycoprotein and the host cell Furin and enhancing cytokine expression. (A) Schematic representation of the BCoV-Spike protein, highlighting the S1 and S2 subunits and Furin cleavage site (S1/S2). The miRNA16a targets two regions within the S1 subunit, indicated in red (starting positions 24,762 and 24,928). (B) A schematic diagram of the bovine Furin shows the miRNA16a target sites in the 3’UTR of the bovine host cell furin; red fonts indicate the starting nucleotides of the seed region of miRNA16a (starting position 793). (C) Illustration of the bovine cells transfected with miRNA scrambled (miRNA-Scr) followed by BCoV infection. The BCoV viral genome is released into the cytoplasm of infected cells, after which viral replication and the production of nested sets of sg mRNAs are initiated. BCoV infection markedly inhibited the expression of some host cytokines (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-10) but enhanced BCoV production. (D) A schematic illustration of the bovine cells transfected with miRNA16a followed by infection with BCoV. The miRNA16a targets host Furin at the cell surface, reducing the BCoV replication by abolishing the BCoV/S glycoprotein cleavage. The overexpression of miRNA16a also showed marked inhibition of the BCoV-S glycoprotein expression levels, ultimately reducing the production of other viral proteins, particularly BCoV-N. The miRNA16a, which targets BCoV-S and the host Furin, substantially inhibited the production of new BCoV progeny. Moreover, this targeting markedly increased the expression of some host cell cytokines, especially the (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-10), which led to further inhibition of BCoV progeny release.

Based on our findings in this study, we concluded that miRNA16a could be a promising diagnostic marker for BCoV infection. This study also highlights the potential antiviral therapeutic potential of bta-miNRA-16a and its feasibility in designing future novel miRNA-based vaccines against BCoV. Previously, it was reported that miR-29a and miR-378b enhance the host DNA-sensing pathway in the presence of CpG motifs and can be used as adjuvants for vaccines63. Similarly, this study revealed that miRNA16a targets the host Furin and enhances interferon production. This highlights the importance of miRNA16a as a potential therapeutic avenue for BCoV infection in cattle.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Udeni B. R. Balasuriya and Mariano Carossino, Louisiana State University, for kindly providing the Madine Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK) and the human rectal tumor-18 (HRT-18) cells used in this study. We also thank Dr. Aspen Workman from the Animal Health Genomics Research Unit, USDA, ARS., US. Meat Animal Research, for kindly providing the bovine coronavirus respiratory isolate used in this study.

Author contributions

M.G.H. conceptualized and designed the whole study, carried out some laboratory experiments, oversaw the entire research data analysis, wrote the manuscript, and submitted the manuscript. A.U.S. carried out the experiments and bioinformatic prediction, analyzed the data, and participated in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a seed grant from Long Island University (Grant no: 36524).

Data availability

The sequences of the generated DNA constructs generated in this study were deposited in the GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore). The IDs of these submissions are (2860015 and 2860033).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.List IMS. https://talk.ictvonline.org/files/master-species-lists/m/msl/9601/download Accessed on 6 Apr 2020 (2019).

- 2.Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.23(1), 3–20 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuyama, S. et al. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.117(13), 7001–7003 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantuti-Castelvetri, L. et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science370(6518), 856–860 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki, T., Otake, Y., Uchimoto, S., Hasebe, A. & Goto, Y. Genomic characterization and phylogenetic classification of Bovine Coronaviruses through whole genome sequence analysis. Viruses12(2) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Vlasova, A. N. & Saif, L. J. Bovine Coronavirus and the associated diseases. Front. Vet. Sci.8, 643220 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peacock, T. P. et al. The Furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat. Microbiol.6(7), 899–909 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemida, M. G., Ye, X., Thair, S. & Yang, D. Exploiting the therapeutic potential of microRNAs in viral diseases: Expectations and limitations. Mol. Diagn. Ther.14(5), 271–282 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng, M. Cellular tropism of SARS-CoV-2 across human tissues and age-related expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in immune-inflammatory stromal cells. Aging Dis.12(3), 718–725 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodnik, J. J., Jezek, J. & Staric, J. Coronaviruses in cattle. Trop. Anim. Health Prod.52(6), 2809–2816 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shang, R., Lee, S., Senavirathne, G. & Lai, E. C. microRNAs in action: Biogenesis, function and regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet.24(12), 816–833 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker, J. S., Roe, S. M. & Barford, D. Molecular mechanism of target RNA transcript recognition by argonaute-guide complexes. Cold Spring. Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol.71, 45–50 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehl, T. et al. About miRNAs, miRNA seeds, target genes and target pathways. Oncotarget8(63), 107167–107175 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]