Abstract

Somatic mutations of hematopoietic cells in the peripheral blood of normal individuals refer to clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), which is associated with a 0.5–1% risk of progression to hematological malignancies and cardiovascular diseases. CHIP has also been reported in Multiple Myeloma (MM) patients, but its biological relevance remains to be elucidated. In this study, high-depth targeted sequencing of peripheral blood from 76 NDMM patients revealed CHIP in 46% of them, with a variant allele frequency (VAF) ranging from ~ 1 to 34%. The most frequently mutated gene was DNMT3A, followed by TET2. More aggressive disease features were observed among CHIP carriers, who also exhibited higher proportion of high-risk stages (ISS and R-ISS 3) compared to controls. Longitudinal analyses at diagnosis and during follow-up showed a slight increase of VAFs (p = 0.058) for epigenetic (DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1) and DNA repair genes (TP53; p = 0.0123). A more stable frequency was observed among other genes, suggesting different temporal dynamics of CH clones. Adverse clinical outcomes, in term of overall and progression-free survivals, were observed in CHIP carriers. These patients also exhibited weakened immune T-cells and enhanced frailty, predicting greater toxicity and consequently shorter event-free survival. Finally, correlation analysis identified platelets count as biomarker for higher VAF among CHIP carriers, regardless of the specific variant. Overall, our study highlights specific biological and clinical features, paving the way for the development of tailored strategies for MM patients carrying CHIP.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Biomarkers, CHIP, Toxicity, Frailty

Subject terms: Cancer, Cancer genetics

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable malignancy of plasma cells that grow within a permissive bone marrow (BM) microenvironment, which supports tumor cells transformation, proliferation and the occurrence of drug resistance1. Over recent years, available therapeutic approaches have shown promising results in the clinical management of MM patients; however, the disease remains incurable due to frequent relapses2. In this context, identifying disease-specific biologic features represents a valuable strategy for improving MM clinical management. Genetic-molecular alterations, including deletion 17p, t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), amp/gain 1q, del 1p or TP53 mutations, as well as high-risk gene expression profiling signatures are, among the most robust predictors of outcomes in MM, with their combination conferring an even worse prognosis3. However, while identifying these features is crucial for prognosis and treatment selection, aging, characterized by impaired organ function and reduced physiological reserves, adds complexity, making patient stratification highly challenging4. In the recent years, several tools have been developed for a comprehensive assessment of MM patients’ frailty. However, none of the available biomarkers are currently able to effectively prevent relapse, reduce mortality, and ultimately cure this blood cancer.

More recent studies based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) have revealed the presence of recurrent somatic mutations in the blood of healthy adults, a condition referred to as clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP)5. Remarkably, somatic mosaicism is ubiquitous in tissues during aging, but when an acquired variant confers growth advantage, the mutant undergoes clonal expansion. Somatic variants that influence cell fitness may occur in every tissue, but the wide availability of blood for serial genomic studies, coupled with its circulation and interaction with all other tissues, makes CHIP particularly interesting due to its clinical consequences6. Mutations driving clonal expansion mostly involve leukemia-associated drivers, with DNMT3A, TET2 and ASXL1 being the most affected genes, followed by JAK2, TP53 and several other genes that are less frequently mutated but still significant for their contribution to fitness gain7. The current definition of CHIP requires the presence of a clone with a variant allele frequency (VAF) greater than 2%, as this is considered the threshold for clinical relevance, in a person without a hematologic malignancy5,8. Nevertheless, the significance of these clones remains to be determined through further and long termed studies9. It has been demonstrated that CHIP is associated with aging, smoking, and exposure to radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy10–12. In addition, CHIP is significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, independent of the development of myeloid malignancy, the incidence of which in the elderly is less than 0.1%7,13,14. Among the overall causes of death, an increased risk of cardiovascular disease has been linked to CHIP, with higher incidence of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in mutation carriers7,15. Similarly, CHIP patients are at greater risk for other inflammatory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease16 and gout17, both mediated by dysregulated inflammatory signaling from mutant macrophages18.

Remarkably, CHIP has also been detected in cancer patients, including those with hematologic malignancies19–22. Indeed, CHIP has been found also among MM patients with a prevalence of 21.6% at the time of ASCT (VAF of at least 1%)23–25. Importantly, its presence has been associated with shorter OS and PFS, particularly in those who did not receive maintenance therapy with IMiDs. Notably, the increased mortality in CHIP patients was not related to a higher risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (TMN), as observed in lymphomas patients following ASCT11, nor to an increase in cardiovascular events. Instead, it was primarily due to disease progression, possibly related to a greater risk of developing treatment toxicity or an inflammatory-prone bone marrow microenvironment that supports tumor growth25. Despite this evidence, there is still little knowledge regarding the clinical impact of CHIP in MM patients, particularly in those who are ineligible for high-dose therapies.

Here, through a retrospective and multicenter analysis, we show the prevalence of CHIP and its related mutations among NDMM patients, which is associated with aggressive disease and poorer clinical outcomes. Notably, CHIP patients are at greater risk of developing treatment-related toxicity, likely due to altered immune-cells distribution and increased frailty, which anticipates shorter event-free survival.

Patients and methods

Study design

A total of 76 patients diagnosed with MM, according to the revised International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria26, were included in this study. These patients were treated between January 2019 to September 2021, at three different hematologic centers in Italy (Genoa, Catania and Cagliari), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were available for sequencing analyses at both diagnosis and follow up. For twelve patients, we also analyzed CD138NEG fractions derived from bone marrow samples, and for only one patient, the CD138POS fraction was available at diagnosis. Longitudinal follow-up analyses have been also performed on samples from 27 patients at 13 ± 5 months after diagnosis (Fig. S1). Detailed patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. CD138POS and CD138NEG cells were isolated from Bone Marrow (BM) aspirates using an immune-magnetic bead-based strategy (MACS system, Mylteni biotech), as previously reported27. The study was conducted under all national and international ethical and legal recommendations, following approval by the local Ethics Review Committee, in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. (Comitato Etico Territoriale, CER- Liguria: 626/2022—DB id 12,752, approved at 3th July 2023). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| All cohort (n = 76) | CHIP (n = 35) | No CHIP (n = 41) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| Median (range) | 71 (40–90) | 72 (46–84) | 71 (40–90) | 0.52* |

| < 50 | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| 50—59 | 13 | 6 | 7 | |

| 60—69 | 17 | 7 | 10 | 0.9** |

| 70—79 | 29 | 15 | 14 | |

| > 80 | 13 | 6 | 7 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 41 | 19 | 22 | 1*** |

| Female | 35 | 16 | 19 | |

| Myeloma subtype | ||||

| IgA kappa | 9 | 4 | 5 | |

| IgA lambda | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| IgG kappa | 29 | 15 | 14 | 0.84** |

| IgG lambda | 19 | 7 | 12 | |

| Kappa-light chain | 9 | 4 | 5 | |

| Lambda-light chain | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Biochemical markers | ||||

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 35.9 | 35.69 | 36.09 | 0.461**** |

| β-2-microglobulin (mg/L) | 6.8 | 9.04 | 4.85 | 0.05**** |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.9 | 2.41 | 1.47 | 0.075**** |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 9.44 | 9.53 | 9.37 | 0.66**** |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.24 | 10.61 | 11.78 | 0.019**** |

| Platelet count (× 10^6) | 229.3 | 224.9 | 233 | 0.609**** |

| LDH (U/L) | 226.1 | 237.6 | 216.3 | 0.335**** |

| BM plasma cell | ||||

| ≥ 10%, median (1q;3q) | 50 (18, 70) | 55 (24, 80) | 50 (15, 66) | 0.2295**** |

| ≥ 60%, median (1q;3q) | 75 (70, 80) | 80 (70, 81) | 70 (65, 80) | 0.11**** |

| Disease stage | ||||

| ISS1 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 0.0051*** |

| ISS2 | 26 | 12 | 14 | |

| ISS3 | 29 | 20 | 9 | |

| R-ISS1 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0.0001*** |

| R-ISS2 | 29 | 9 | 20 | |

| R-ISS3 | 29 | 23 | 6 | |

| EMD (Y/N) | 48/27 | 24/11 | 24/16 | 0.48***** |

| Induction therapy | ||||

| Anti-CD38 cont. regimens | 33 | 15 | 18 | |

| PIs cont. regimens | 25 | 13 | 12 | |

| Lent cont. Regimens | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0.83** |

| Other | 9 | 9 | 6 | |

| LOT mean | 1.43 (0—5) | 1.53 (0—4) | 1.35 (1—5) | 0.1961**** |

*t-test.

**Fisher test.

***chi^2 test.

****Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

*****binom. test.

Sample preparation, sequencing and data analysis

DNA was isolated from whole peripheral blood and BM samples (using CD138POS and CD138NEG fractions, when available) using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Next Generation Sequencing of those samples was performed at both diagnosis and follow up, employing an Illumina Custom Enrichment panel targeting 36 recurrently mutated genes in myeloid cells (detailed in Table 2). Libraries preparation was carried out using the Illumina DNA Prep with Enrichment workflow, following the manufacturer’s instruction. The quality and size distribution of the libraries were assessed using a Qubit fluorimeter and Agilent TapeStation system. Sequencing was performed using the MiSeq platform (Illumina) with 2 × 150 cycles, paired-end sequencing, at a median coverage depth of 500x, at the Genomics Core of IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Data analysis was conducted using the BaseSpace Software (Illumina) and the Dragen Enrichment pipeline, with the “somatic” setting. Variants located in intronic or synonymous regions with no impact on splicing, as well as missense and short ins/dels reported variants classified as “benign” or “likely benign” in ClinVar, were excluded28. Variants not reported in COSMIC, and those with CADDphred score < 25, were also filtered out, as well as variants with a neutral or uncertain impact on protein function29. A Variant allele frequency (VAF) cut-off of > 1% was used to define CHIP30,31. Variants with a VAF > 40% or those with a population frequency greater than 1% were also excluded. The selected somatic mutations and their VAFs were correlated with demographic and clinical parameters, including age, sex, ISS, R-ISS stage, outcomes, and occurrence of adverse events. Additional analyses were conducted at 12–24 months post-therapy and for patients with available BM samples, both the tumoral (CD138POS) and non-tumoral (CD138NEG) fractions were analyzed in parallel. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI BioProject repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1173522).

Table 2.

Panel genes list used.

| Gene | Target region (exon) | Gene2 | Target region (exon)3 | Gene4 | Target region (exon)5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASXL1 | Full | GATA2 | Full | PPM1D | 5, 6 |

| BCOR | Full | GNAS | 8, 9 | PTEN | Full |

| BCORL1 | Full | GNB1 | 5–7 | PTPN11 | 2–4, 8, 13 |

| BRAF | 11, 15 | IDH1 | 4 | RAD21 | Full |

| BRCC3 | Full | IDH2 | 4 | RUNX1 | Full |

| CBL | 8, 9 | IKZF1 | Full | SF3B1 | 13–16 |

| CREBBP | Full | JAK2 | 12, 14 | SMC3 | Full |

| CUX1 | Full | KRAS | 2, 3 | SRSF2 | 1 |

| DNMT3A | Full | MPL | 10 | STAG1 | Full |

| EZH2 | Full | MYD88 | 3–5 | STAG2 | Full |

| FLT3 | 14, 15, 20 | NF1 | Full | TET2 | Full |

| GATA1 | Full | NOTCH1 | 26–28, 34 | TP53 | Full |

Multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) analysis

Multiparameter Flow Cytometry (MFC) analysis was performed at local laboratories on bone marrow (BM) samples collected at diagnosis or prior to the induction therapy. Whole blood (2 mL, EDTA-treated) was bulk lysed using 1 × BD Pharm Lyse™ Lysing Buffer (30 mL) for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 7 min. The cell pellet was washed once in Dulbecco’s PBS. Cells (50 µL at a concentration of 10–20 × 106/mL) were stained for cell surface markers using 20 µL antibody combinations for 15 min at room temperature. Intracellular nuclear (n) and cytoplasmic (cy) staining were conducted following fixation and permeabilization of the cells using the Intrastain kit (DAKO, Milan, Italy). The following monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) combinations were used for staining: (1) CD138FITC/CD56PE/CD20PerCp/CD117APC/ CD45APC-H7/CD38PE-Cy7- used to quantify plasma cells; (2) cyKappaFITC/cyLambdaPE/CD19PerCp/ CD56APC/CD45APC-H7/CD38PE-Cy7- used to evaluate plasma cell immunophenotype and clonality. Acquisition and analyses were performed using FACSCantoTM II (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA), and DiVa software. A minimum of 1–2 × 104 events for sample were acquired. As controls, anti-isotype mouse antibodies were used. The CD38bright/SSC low population was representative for plasmacell fraction and cytofluorimetric data were analyzed when an abnormal plasmacell population was detected. Based on the expression levels of the specific cluster of differentiation (CD), two categories were established: bright-expressors and low(non)-expressors, with dim levels classified as the latter. Samples were considered positive for a particular antigenic profile if at least 20% of multiple myeloma (MM) cells expressed the respective markers, as previously described27.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected in spreadsheets and analyzed using R statistical software (v. 4.0.5; RStudio) and SPSS (v. 25; IBM). For patients’ characteristics, continuous variables were expressed as mean or median and compared with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov or Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and compared using the Chi-square, binomial test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for survival analysis between groups. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation analysis between variables was performed using Pearson’s correlation method.

Results

Prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis among NDMM patients

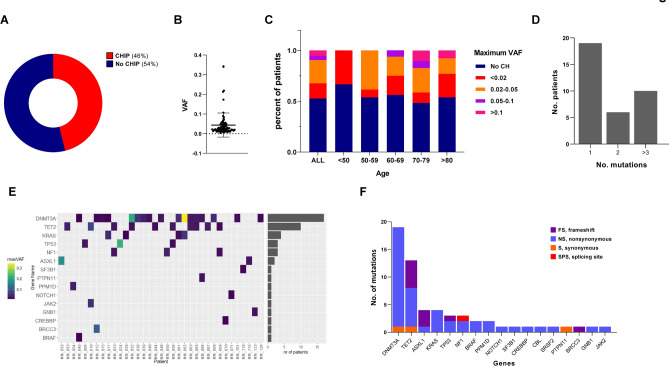

A total of 76 multiple myeloma (MM) patients, whose peripheral blood (PB) samples were available at our institutions in Genoa, Catania and Cagliari, were screened for clonal hematopoiesis-related mutations using deep sequencing approaches. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire cohort. The median age was 71 years (range, 40–90 years), with no gender (41 males vs. 35 females) or addictive behavior (smoking) prevalence as well; IgG was frequently observed as immunoglobulin isotype (48/76) with k and λ free light chains occurring in 29 and 19 of these patients, respectively. The most represented induction regimens included MoAbs and PIs-based strategies with lenalidomide-based treatment used in 9 cases. Overall, next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses revealed at least one CHIP variant in 46% of patients (35/76), with a median variant allele frequency (mVAF) of 0.022 (range 0.003–0.340) (Fig. 1A,B). No significant differences were observed between CHIP carriers and non-carriers in terms of gender (p = 1; chi-squared test), myeloma subtype (p = 0.84; Fisher’s exact test), induction regimens (p = 0.83; Fisher’s exact test) or lines of therapies (p = 0.1961; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Interestingly, contrary to previously reported data25, advanced age was not associated with higher CHIP prevalence, although a greater VAF (> 0.1) was observed in patients older than 70 years (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

CHIP is frequently observed among NDMM patients. (A) Pie chart showing the percentage of CHIP vs no-CHIP patients in our cohort; (B) variant allele frequency (VAF) among CHIP carriers; (C) percentage of MM patients stratified by clone size, as measured by VAF across the entire cohort (ALL) and within specific age groups. (D) The number of patients harboring mutations in 1, 2, and 3 different genes; (E) the number of mutations (y-axis) identified in each gene (x-axis) across the entire cohort, with mutation types color-coded according to the legend; (F) Oncoplot showing mutation across the CHIP-carrying cohort (N = 36). Each column represents an individual patient, while genes (listed by frequency) indicated on the left. The maximum mutation VAF for each mutation is colored according to the scale bar shown on the left; the VAF cutoff used to call mutations was 0.01. The right bar graph shows the number of patients carrying any mutants for indicated genes.

Nineteen patients (54.2%) had a single CHIP mutation, while six (17.1%) had two mutations, and ten (28.5%) had three or more mutations (Fig. 1D). Consistent with others reports32–34, the most commonly mutated gene was DNMT3A (54% of cases with mVAF of 9%), followed by TET2 (37% of cases with mVAF of 3.0%), ASXL1 and KRAS (both with mVAF of 11%). Mutations in splicing factors and JAK2 were rare (Fig. 1E and Table 3). Finally, CHIP-mutational spectrum analyses revealed a predominance of nonsynonymous mutations, followed by frameshift and synonymous mutations in affected genes. The gene-specific variant frequency across whole patients is summarized in Fig. 1F. Collectively, these data indicate that CHIP is a frequently observed event among MM patients at diagnosis, aligning with previously reported data25,32–34.

Table 3.

List of variants observed in PB of CHIP carriers at diagnosis.

| Pt | Gene 1 | Variant | VAF | Gene 2 | Variant | VAF | Gene 3 | Variant | VAF | Gene 4 | Variant | VAF | maxVAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM_061 | KRAS | c.34G > T (p.Gly12Cys) | 0.018 | DNMT3A | c.2711C > T; p.Pro904Leu | 0.053 | DNMT3A | c.2479-2A > G | 0.009 | 0.053 | |||

| MM_110 | SF3B1 | c.2440 T > C | 0.0126 | ||||||||||

| MM_006 | TP53 | c.97-1G > C | 0.025 | 0.025 | |||||||||

| MM_050 | NF1 | c.204 + 1G > A | 0.037 | 0.037 | |||||||||

| MM_070 | CREBBP |

c.5123A > G; p.Asn1708Ser |

0.009 | 0.009 | |||||||||

| MM_063 | DNMT3A | c.1784 T > C | 0.028 | TET2 | c.4748C > G; p.S1583 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| MM_032 | DNMT3A | c.2194_2196del; p.Phe640del; | 0.213 | TET2 | c.4581del; (p.Gln1527HisfsTer44) | 0.02 | 0.213 | ||||||

| MM_015 | DNMT3A |

c.1668G > T; p.Arg556Ser |

0.015 | ||||||||||

| MM_023 | NF1 |

c.1381C > T; p.Arg461Ter |

0.022 | TET2 | 4:c.1826del; Asn610Thrfs*28 | 0.024 | CBL | c.1259G > A | 0.014 | 0.024 | |||

| MM_033 | ASXL1 |

c.2058_2059del; p C687Yfs*28 |

0.021 | ASXL1 | c.1934dup;(p.Gly646TrpfsTer12) | 0.173 | 0.021 | ||||||

| MM_067 | TET2 | c.3876C > G; p.S1292R | 0.031 | 0.031 | |||||||||

| MM_062 | KRAS | c.35G > C; p.(Gly12Asp) | 0.056 | DNMT3A | c.2645G > A; p.(R882H) | 0.34 | SRSF2 | c.284C > T; p.P95L | 0.049 | 0.34 | |||

| MM_040 | DNMT3A | c.886G > A | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| MM_024 | TP53 | c.722C > A; p.S241Y | 0.219 | 0.219 | |||||||||

| MM_056 | TP53 | c.535C > G; p.H179D | 0.015 | TET2 | c.4100C > A; p.P1367Q | 0.026 | TET2 | c.3941del; (p.Asp1314ValfsTer49) | 0.013 | 0.26 | |||

| MM_044 | TET2 | c.5908_5909del; p.(L1971Cfs*42) | 0.017 | 0.017 | |||||||||

| MM_069 | NF1 | c.539 T > A; p.L180 | 0.018 | TET2 | c.4894C > T; p.Q1632 | 0.013 | 0.018 | ||||||

| MM_126 | DNMT3A | c.920C > G; p.Pro307Leu | 0.0122 | ||||||||||

| MM_054 | PPM1D | c.1405A > T; p.(K469*) | 0.011 | PPM1D | c.1414G > T; p.E472* | 0.032 | 0.032 | ||||||

| MM_017 | DNMT3A |

c.2254 T > A; F752I (p.Phe752Ile) |

0.011 | KRAS | c.34G > T (p.Gly12Cys) | 0.047 | 0.047 | ||||||

| MM_071 | NO TCH1 | c.5560C > T; p.(R1854C) | 0.011 | 0.011 | |||||||||

| MM_049 | DNMT3A | c.2401A > G; p.M801V | 0.01 | BRAF | c.1801A > G; p.K601E | 0.011 | BRAF | c.1781A > G; p.D594G | 0.011 | DNMT3A | .2711C > T; NP_072046.2:p.Pro904Le | 0,003 | 0.011 |

| MM_068 | DNMT3A | c.892G > C | 0.045 | 0.045 | |||||||||

| MM_028 | KRAS |

c.351A > T; (p.Lys117Asn) |

0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||||

| MM_123 | GNB1 | c.169A > G; p.Lys57Glu | 0.0205 | ||||||||||

| MM_053 | TET2 | c.3010A > T; p.(K1004*) | 0.033 | TET2 | c.3500G > T; p.R1167M | 0.015 | TET2 | c.4045-2A > G | 0.009 | 0.033 | |||

| MM_066 | DNMT3A | c.2602 T > C; p.F868V | 0.022 | PTPN11 | c.526-15 T > G | 0.02 | 0.022 | ||||||

| MM_039 | DNMT3A | c.1915C > T; p.L639F | 0.034 | 0.034 | |||||||||

| MM_048 | DNMT3A | c.2449G > T; p.(E817*) | 0.023 | 0.023 | |||||||||

| MM_101 | DNMT3A |

c.2711C > T; p.Pro904Leu |

0.0165 | ||||||||||

| MM_010 | JAK2 |

c.1849G > T (p.Val617Phe) |

0.049 | TET2 | c.2375C > G; p.S792* | 0.076 | ASXL1 | c.1934dup;(p.Gly646TrpfsTer12) | 0.09 | 0.076 | |||

| MM_115 | ASXL1 | c.3943C > T; p.Q1310* | 0.0239 | ||||||||||

| MM_012 | DNMT3A | c.2578 T > C; p.W860R | 0.013 | BRCC 3 | c.274del; p.I92Phefs*18 | 0.107 | TP53 | NA | 0.107 | ||||

| MM_065 | DNMT3A | c.2477A > G; p.K826R | 0.031 | TET2 | c.5435_5450del; p.(Val1812Alafs*3) | 0.023 | 0.031 | ||||||

| MM_038 | DNMT3A | c.1904G > A; p.R635Q | 0.055 | 0.055 |

CHIP is associated with greater aggressiveness and poorer clinical outcomes

CHIP negatively impacts MM patient’s clinical outcomes, resulting in shorter PFS and OS after ASCT. Importantly, these negative effects are mitigated by IMiDs maintenance therapy24,25,34. Consistent with these findings, we first aimed to assess the impact of CHIP on disease progression parameters in our cohort. Initially we investigated the cellular origins of these abnormalities. As shown in Fig. 2A, no significant differences were observed in the percentage of bone marrow plasma cells between CHIP-carriers and non-carriers, suggesting that the myeloid somatic mutations are unlikely to originate from the malignant tumor cells. Indeed, analysis of bone marrow CD138NEG cells (the fraction depleted of tumor plasma cells) revealed a correlation between BM and PB VAF values, confirming the non-tumor origin of the screened myeloid mutations. (Pearson R = 0.97, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

CHIP is associated with greater biological aggressiveness of the disease. (A) Histogram plot showing BMPCs ≥ 60% in CHIP (red) carriers compared with those without abnormalities (blue). Data are mean ± SD; ns = not significant (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). (B) Regression analysis correlating VAF in BMSCs (CD138NEG) and PBMCs across the entire cohort. R = 0.97; p < 0.0001(unpaired t-test). (C) Violin plot displaying β2-microglobulin, 24 h protein urine, creatinine, serum FLC k, eGFR and hemoglobin levels between samples with CHIP (red) and those without (blue). Statistically significant differences are marked by asterisk. Data are mean ± SD; *p = 0.05, **p = 0.03, ***p = 0.02 (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). (D) MOSAIC plot related to Person’s chi-squared test, showing the relationship between CHIP and ISS and R-ISS stages (I-III).

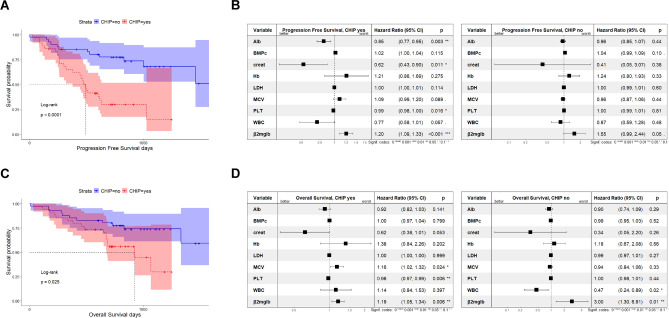

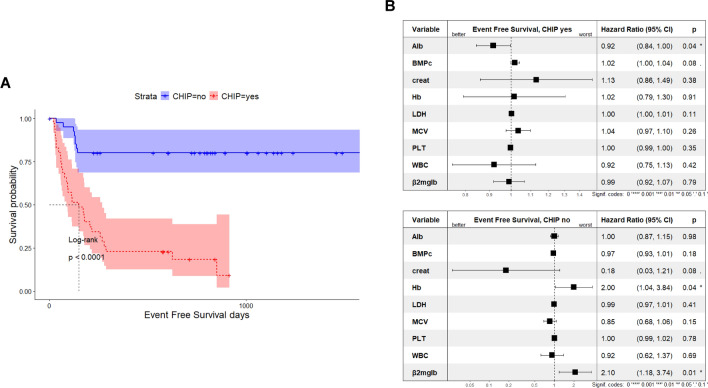

Next, we examined the impact of CHIP on disease aggressiveness markers. CHIP carriers had higher levels of β2-microglobulin (9.04 vs 4.15 mg/dl; p = 0.05), 24-h urine protein output (1.44 vs 1.10 g/24 h; p = 0.019), creatinine (2.41 vs 1.47 mg/dl; p = 0.075) and serum FLC k (557.2 vs 250 mg/dl; p = 0.031), alongside lower levels of eGFR (46.57 vs 64.38; p = 0.024) and hemoglobin (10.61 vs 11.78 g/dL; p = 0.019) compared with non-CHIP carriers (Fig. 2C). In line with these findings, mosaic plot analysis showed stages disease differences between the two groups, with a higher prevalence of CHIP carriers among high-risk patients, as defined by the International Staging System (ISS) and the Revised (R)-ISS staging systems (Fig. 2D). Together, these data confirm that CHIP serves as biomarker of disease-aggressiveness, and its evaluation could enhance risk stratification for MM patients. (Table 1) Considering these assumptions, we next examined clinical outcomes in our cohort. As shown in Fig. 3A–D, the presence of CHIP was associated with significantly shorter PFS (mPFS of 493 days in those with CH vs. not reached at 5000 days in control; p < 0.0001) and OS (mOS of 925 days in CH carriers vs. not reached at 5000 days in non-carriers; p = 0.025). A multivariate Cox-model analysis focused on CHIP identified high β-2 microglobulin levels as a predictor of poorer clinical outcomes for both PFS (HR, 1.20; 95% CI 1.09–1.33) and OS (HR, 1.19; 95% CI 1.05–1.34), and this parameter retained its negative impact also among patients without CHIP. Furthermore, while platelets count significantly predicted both PFS (HR, 0.99; 95% CI 0.98–1.00) and OS (HR, 0.98; 95% CI 0.97–0.99) in CHIP carriers, no significant effects were observed in patients without CHIP. Similarly, albumin (HR, 0.85; 95% CI 0.77–0.95) and creatinine levels (HR, 0.62; 95% CI 0.43–0.90) significantly influenced PFS of CHIP carriers.

Fig. 3.

CHIP presence affects clinical outcomes of MM patients. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) and PFS probability among MM patients with (blue line) and without (red line) CHIP. Log-rank test was used to compute the p-value. (B) Forest plot based on Cox proportional hazard analysis of the indicated variables (albumin, BMPCs, creatinine, Hb, LDH, MCV, platelet count, white blood cell count, and β2-microglobulin) for PFS. (C) Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS probability. (D) Forest plot for OS, showing hazard ratios (squares) and 95% confidence intervals (bars).

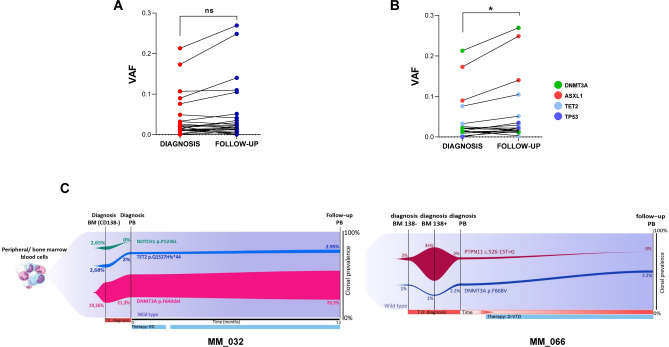

Dynamic changes in clonal hematopoiesis during MM progression

To investigate clonal performance over time, we used serial VAF measurements as a surrogate for clone size. Although we observed a slight increase in VAF values for all tested genes over time, this increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 4A). However, when focusing on genes reported to be crucial for myeloid fitness (DNMT3A, ASXL1, TET2 and TP53), we found a significant VAF increase during follow-up, suggesting the coexistence of different clones with distinct evolutionary trajectories, within single patient (Fig. 4B). To delineate the factors influencing each clone’s growth rate, we analyzed serial samples from 10 selected CHIP carriers, with a median time of 10 months (range: 3–12 months) between the first and second sample collection. While no significant overall increase in VAF was observed, clones carrying mutations in the fitness-related myeloid genes expanded more rapidly, showing a significant VAF increment over time. Moreover, backward tracking revealed that these variants pre-existed at diagnosis, typically at lower or similar VAF levels. Figure 4C presents exemplary fish-plots of two representative patients with available clinical information. The lenalidomide-refractory patient MM_032, harboring DNMT3A and TET2 mutant clones in the BM (CD138NEG cells) and PB at diagnosis, exhibited an increased size of both variants during treatment (from a PB-measured VAFs of 2 and 21.3, to 2.95 and 26.9, respectively). In contrast, a NOTCH1 variant was found only in the BM, likely representing a passenger mutation not driving clonal expansion. Similarly, patient MM_066, who received a daratumumab-based regimen, showed stability of the DNMT3A variant in PB, CD138NEG and CD138POS BM cells after 3 months of follow up. The PTPN11 mutant, driving a clone in the BM tumor fraction, become nearly undetectable after treatment, leading us to speculate that it was primarily a plasmacellular variant. Collectively, these data suggest that CHIP dynamics are not influenced by any specific event but rather by the type of mutation present. Indeed, MDS/AML-driving genes (DNMT3A, TET2, TP53, and KRAS) tend to increase in size, regardless of response or disease status.

Fig. 4.

Dynamic changes in CHIP over time. (A) Comparison of VAF between diagnosis and follow-up for all mutated genes. (B) Comparison of VAF for the most relevant mutated genes, as indicated in the legend. Data are mean ± SD; *p = 0.01, ns = not significant (paired t-test). (C) Fish plots showing clonal clusters of indicated CHIP genes in BM (tumor and non-tumor fractions) and PB samples from two representative MM patients (MM_032 and MM_066) at serial time points. MM_032 had DNMT3A and TET2 variants in BM and PB, which expanded after 12 months of follow-up, while a NOTCH1 variant was only found in BM, likely representing a passenger mutation not driving clonal expansion. In MM_066, the PPM1D clone was identified at diagnosis but decreased in allelic frequency at follow-up, whereas DNMT3A clones expanded from diagnosis to follow-up. CHIP = clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, BM = bone marrow, PB = peripheral blood.

CHIP presence enhances frailty in MM patients

To identify specific differences between two groups, we subsequently calculated the onset of pharmacological toxicity among CHIP and non-CHIP carriers. As shown in Table 4, the overall safety did not differ significantly, although the incidence of adverse events (AEs) of any grade was slightly higher in the CH group (97%) compared to no-CHIP patients (80%). Importantly, when focusing on grade ≥ 3 AEs, the rate was significantly lower in non-CHIP patients compared with CHIP carriers (36.5 vs 85.7%; p = 0.036). Neutropenia of any grade was the most common hematological event, occurring in 20 CHIP patients (57%) compared to 13 (31.7%) in those without CHIP, although this difference was not significant (p = 0.296). A similar trend was observed with other hematologic toxicities, with anemia occurring significantly more frequently among CHIP carriers than non-CHIP carriers at any grade (p = 0.021 and 0.016, respectively). For non-hematologic toxicities, peripheral neuropathy was more frequent in CHIP carriers than in non-CHIP patients, showing significant differences irrespective of its specific grade (p = 0.035 and 0.004 for any grade or higher toxicities, respectively). The most notable difference between the groups was in infections, with SARS-CoV-2 significantly affecting CHIP-carrying patients more than those in the control group (45.7% vs 9%; p = 0.012). Most serious (grade ≥ 3) infections, including pneumonia, occurred among CHIP carriers; however, the low number of censured cases prevented these differences from being significant (p = 0.36 and p = 0.37 for any grade or grade ≥ 3 toxicity, respectively). Clonal hematopoiesis has been reported to be associated with cardiovascular disease in MM patients32, so we analyzed cardiovascular events rates (CVEs) in our cohort. While the overall rates were comparable between groups, venous thromboembolism appeared more frequently in CHIP carriers (51.4 vs 17%; p = 0.043), although the limited number of cases prevented drawing significant conclusions.

Table 4.

Drug-associated toxicities in the entire cohort.

| Event | All cohort | Grade | CHIP | No CHIP | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event, n (%) | 60 (78.9) | Any grade | 34 (97) | 33 (80) | 1 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 30 (85.7) | 15 (36.5) | 0.036 | ||

| Hematologic adverse event | |||||

| Neutropenia | 33 (43.4) | Any grade | 20 (57) | 13 (31.7) | 0.296 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 15 (42.8) | 10 (24.3) | 0.424 | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 (15.7) | Any grade | 8 (22.8) | 4 (0.9) | 0.388 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 7 (20) | 0 | 0.016 | ||

| Anemia | 10 (13.1) | Any grade | 9 (25.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.021 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 7 (20) | 0 | 0.016 | ||

| Non-hematologic adverse event | |||||

| GI | 20 (26.3) | Any grade | 15 (42.8) | 5 (12) | 0.041 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 5 (14.2) | 2 (4.8) | 0.453 | ||

| PN | 15 (19.7) | Any grade | 12 (34.2) | 3 (0.7) | 0.035 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 9 (25.7) | 0 | 0.004 | ||

| Rash | 8 (10.5) | Any grade | 6 (17.1) | 2 (0.5) | 0.289 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 6 (17.1) | 1 (2.4) | 0.125 | ||

| Infections | |||||

| Coronavirus disease 2019 | 20 (26.3) | Any grade | 16 (45.7) | 4 (9) | 0.012 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 5 (14.2) | 0 | 0.063 | ||

| Pneumonia | 15 (19.7) | Any grade | 9 (25.7) | 6 (14) | 0.607 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 5 (14.2) | 3 (7.3) | 0.726 | ||

| Cardio-vascular events | |||||

| VTE | 25 (32.8) | Any grade | 18 (51.4) | 7 (17) | 0.043 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 10 (28.5) | 5 (12.1) | 0.302 | ||

| Ischemic events | 5 (6.5) | Any grade | 4 (11.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0.375 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 | ||

| Arrhythmias | 8 (10.5) | Any grade | 5 (14.2) | 3 (7.3) | 0.726 |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (4.8) | 1 | ||

PN: peripheral neuropathy.

VTE: venous thromboembolism.

GI: gastrointestinal toxicity.

*Binomial test without post hoc correction.

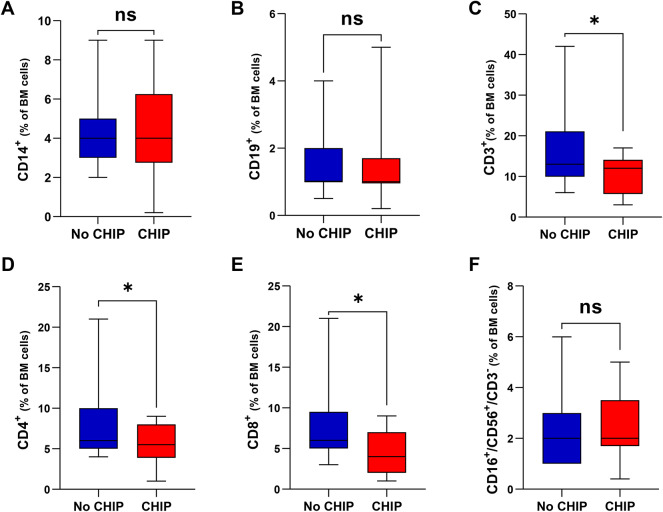

To support the observed fragility of CHIP patients in our cohort, we next screened their bone marrow immune phenotype, where available. As shown in Fig. 5, effector T-cells resulted significantly reduced in CHIP vs no-CHIP carriers with both CD4+ and CD8+ cells equally compromised, while B (CD19+), monocytes (CD14+) and NK (CD16 + /CD56 + /CD3-) cells were almost unaffected by CHIP presence. The impairment in T-cell fitness led us to calculate frailty scores of our patients by using age (0 if ≤ 75 years, 1 if 76–80 years, 2 if > 80 years), Charlson Comobidity Index (CCI) (0 if ≤ 1, 1 if > 1), and ECOG PS (0 if 0, 1 if 1, 2 if ≥ 2)35. Remarkably, this approach showed an enrichment of frail patients among CHIP carriers compared with no-CHIP patients (97.1% vs 56%; p < 0.0001), supporting the enhanced vulnerability to AEs observed in the former. (Table 5) It is suggested that AEs lead to treatment discontinuation, so we examined the impact of clonal hematopoiesis on event free survival (EFS) in our cohort. CHIP negatively impacted prognosis, with its presence associated with shorter EFS than its absence (Fig. 6A; p < 0.0001). A multivariate Cox model indicates that albumin level (HR, 0.92; 95% CI 0.84–1) was the only parameter able to improve EFS among CHIP carriers. By contrast, hemoglobin (HR, 2; 95% CI 1.04–3.84) and β2-microglobulin (HR, 2.10; 95% CI 1.18–3.74) values worsened outcome in patients without CHIP (Fig. 6B). Overall, our data suggest that CHIP impairs the fitness of MM patient, making them more prone to developing therapy-related toxicities, including infection. This, in turn, leads to a greater likelihood of treatment delays or dose reductions, limiting the patient’s ability to receive optimal therapies.

Fig. 5.

Bone Marrow immune cells distribution in CHIP and no-CHIP carriers. Histogram plots displaying the percentages of monocytes CD14 + (A), B-lymphocytes CD19 + (B), T-lymphocytes CD3 + (C), T-lymphocytes CD4 + (D), T-lymphocytes CD8 + (E) and NK CD16 + /CD56 + /CD3- cells (F) among BM mononuclear cells of samples with CHIP (red) and no-CHIP (blue). Statistically significant differences are marked by asterisk. Data are mean ± SD; *0.024 < p < 0.039, ns = not significant (unpaired t-test).

Table 5.

Frailty analysis of entire cohort according to Gordon Cook et al. Leukemia. 2020.

| All cohort | CHIP | No CHIP | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG PS, n (%) | 0.0005 | |||

| 0 | 8 (10.5) | 0 | 8 (19.5) | |

| 1 | 37 (48.6) | 14 (40) | 23 (56) | |

| ≥ 2 | 31 (40.7) | 21 (60) | 10 (24.3) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n | 0.22 | |||

| ≤ 1 | 6 (7.8) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (12.1) | |

| > 1 | 70 (92.1) | 34 (97.1) | 36 (87.8) | |

| Age at diagnosis, n | 1 | |||

| ≤ 75 | 54 (71) | 25 (71.4) | 29 (70.7) | |

| 76–80 | 9 (11.8) | 4 (11.4) | 5 (12.1) | |

| > 80 | 13 (17.1) | 6 (17.1) | 7 (17) | |

| Frailty definition | < 0.0001 | |||

| Nonfrail | 19 (25) | 1 (2.8) | 18 (44) | |

| Frail | 57 (75) | 34 (97.1) | 23 (56) |

Fig. 6.

CHIP impacts event free survival of MM patients. (A) Kaplan-Meyer curves for event free survival (EFS) in our cohort according to CHIP status. CHIP carriers are shown in blue and non-carriers in red. Log-rank test was used to compute the P-value (Log-Rank test). (B) Forest plot based on Cox proportional hazard analysis of the indicated variables (albumin, BMPCs, creatinine, Hb, LDH, MCV, platelets count, white blood cells count and β2-microglobulin) for CHIP carriers (top) and non-CHIP carriers (bottom). Squares represent hazard ratios, and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

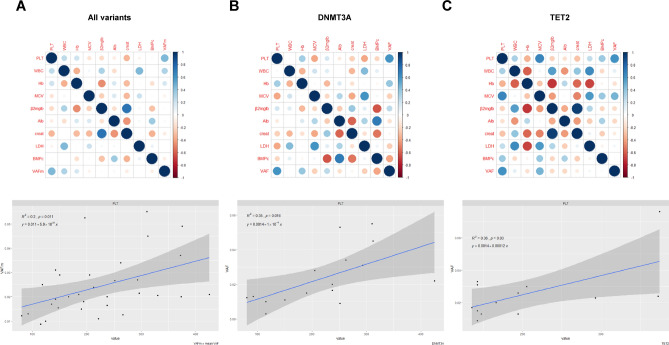

Next, to analyze the specific impact of clonal hematopoiesis in our cohort, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed based on the available data. As shown in Fig. S2, CHIP and no-CHIP samples were projected onto the principal component (PC) space, and two ellipses were calculated. Unfortunately, the first two components (PC1 and PC2) did not show a clear pattern, suggesting that a clinical-based approach fails to predict CHIP presence. CHIP refers to cancer-associated driver mutations present at a variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥ 2% in subjects without hematologic abnormalities. Based on this assumption, we next built a further model to screen VAF and clinical data in our cohort. This mathematical model proved more effective than previous approach, identifying platelet count as clinical indicator for greater VAF in MM patients, regardless of specific variants carried (Fig. 7A). Importantly, these results were also confirmed when focusing on the most frequent mutants, DNMT3A and TET2 (Fig. 7B,C and S3). Overall, these findings led us to speculate that platelet count may serve as a surrogate biomarker for higher VAF rate among CHIP carriers, even though its presence alone is not significantly different between CHIP-positive and CHIP-negative individuals.

Fig. 7.

Platelet count as a novel biomarker for high VAF rate among CHIP carriers. (A–C) Correlogram showing correlation between clinical parameters, including VAF or median VAF (mVAF) in CHIP carriers (A) or those carrying specific variants (B and C). Rows and columns indicate each feature with colors in the boxes representing correlation values: red indicates negative correlation, while blue indicates positive correlation. The area covered in each square corresponds to the absolute value of the correlation. In the lower panel, regression analysis with specific confidence intervals links VAF and platelet count across CHIP carriers with all or indicated variants (p-values are indicated).

Discussion

Recent studies have identified the presence of somatic mutations in hematopoietic cells in the blood of aging individuals, a condition referred as clonal hematopoiesis of unknown significance (CHIP)36. By providing a fitness advantage to HSCs, CHIP is associated with a 0.5–1% risk of progression to a non-plasma-cell hematologic neoplasm, such as MDS and AML5,7,14,37. Moreover, CHIP is also associated with aging-related conditions linked to aberrant inflammatory responses, such as atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases18. In cancers, the prevalence of CHIP is higher compared to healthy population, particularly in patients exposed to cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation10. Recent studies suggest the presence of these myeloid clones among MM patients, with an impact on clinical outcomes23–25,32,38,39; however, the biological relevance of this abnormality remains to be elucidated.

Here, we report the prevalence of CHIP in a multicenter cohort of NDMM patients at the time of diagnosis and after 12–24 months of treatment and describe the association of CHIP with the clinical characteristics and outcomes of these patients. Overall, we found somatic mutations in 46% of our population, which is much higher than expected and previously reported (21.6%)25. This finding could be related to the sequencing method used, which achieves greater reading depth and thus allows for detecting lower VAF (> 1%). Remarkably, consistent with prior studies, we found that CHIP status correlates with higher disease aggressiveness, though differences were observed in term of aging, as previous studies have demonstrated a CHIP prevalence increase with age24,25. Although these findings may appear contradictory, greater burden (VAF > 0.1) occurred among patients older than 70 years, which is consistent with other studies40 as well as for the most frequently mutated genes (DNMT3A followed by TET2). Moreover, we confirmed the association between CHIP and poorer clinical outcomes, including progression-free and overall survivals, which in turn reflects the biologic status of the disease, as partially reported35,41,42.

In recent years, novel drugs have significantly improved the prognosis of MM patients. However, continuous treatments often face limitations due to the development of serious and unexpected toxicities leading to their discontinuation. Consistent with this observation, we analyzed patients, among CHIP carriers who experienced AEs during treatment. Event-free survival is greatly impaired by the presence of CHIP, with AEs of any grades, including infections, occurring more frequently in this group. Similarly, recurrent infections were more common among CHIP carriers. Although the small sample size prevents any firm conclusion, we might speculate that a pro-inflammatory microenvironment may have impaired patient’s fitness, leading to increased susceptibility to therapeutic toxicity. Indeed, a detailed analysis of bone marrow environment revealed a consistent impairment in T cells among CHIP carriers, which, together with their higher frailty scores, explains the greater vulnerability to infections in this group. Moreover, while our data support CHIP screening at disease onset to better profile patient fitness, they also suggest that its presence may influence T-cells based therapies. This makes CHIP evaluation a mandatory strategy to select the most appropriate therapeutic approach for each MM patient19,43.

Interestingly, our study includes also longitudinal data for a subset of patients. A slight increase in VAF was recorded for MDS/AML drivers (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1 and TP53) without the appearance of additional mutations in other genes. These data demonstrate that micro-clones in the hematopoietic compartments of MM patients slightly increase in size but remain quite stable in terms of mutated gene types during disease evolution. This suggests that the mutational profile of myeloid cells may be largely unaffected by anti-MM therapies, including daratumumab-based regimens. On the other hand, the presence of theses clones, as indicated by our data, correlates with more aggressive disease and worse outcomes. As a result, we speculate that the pro-inflammatory status supported by these clones facilitates tumor growth within BM microenvironment.

Recent studies suggest an impaired regenerative potential of hematopoietic stem cell grafts in autologous stem cell transplant recipients harboring CHIP. Specifically, reduced stem cell yields and delayed platelet count recovery following ASCT are observed in the presence of DNMT3A and PPM1D variants38. Consistent with these data, although platelet count did not differ significantly between CHIP and non-CHIP carriers, a striking association was found between platelets count and CHIP burden among the former: high platelet levels indicate greater VAF in CHIP carriers, regardless of specific mutants. As reported, CHIP is associated with a pro-inflammatory status, which leads to a fourfold increase of cardiovascular illness incidence44. The biologic mechanisms of these dependencies are complex, but increased level of several cytokines (i.e. IL-6, IL-1 beta, IL-8 and NLRP3) are shared features. As a result, inflammasome-targeting agents (i.e. vitamin C and aspirin) are currently being tested in ongoing clinical trials as preventive strategies to block CHIP-inflammation cascade and improve outcomes of individuals with CHIP. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06097663, NCT03682029) Although our cohort has a limited samples size, we pinpoint the relevance of platelets count, a well-known inflammatory indicator, as a promising biomarker of VAF among CHIP carriers. Importantly, by linking an inflammatory-prone status with a higher VAF rate, our study suggests the predictive role of platelet count in identifying the greater tumor aggressiveness observed among CHIP carriers compared to other MM patients. However, the impaired fitness status observed in these patients, leads us to speculate that less intensive therapies should be preferred in cases of high platelet counts to reduce the occurrence of severe adverse events, especially after high-dose regimens. Larger prospective studies are needed to clarify the impact of platelet counts on MM patients carrying CHIP and to support a cause-effect relationship with this association.

In conclusion, our study confirms that CHIP is frequently observed among MM patients, where it correlates with a more aggressive disease and poorer clinical outcomes. Interestingly, the presence of CHIP is associated with the early development of toxic events, while its burden appears to be related to platelets count. Consistent with our results, we propose specific management strategies for CHIP-carrying MM patients, particularly regarding therapy-related toxicity.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, IG #23,438, to M.C.), International Myeloma Society (IMS) and Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation Translational Research Award 2023.

Author contributions

E.G. and M.C. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; C.M., D.S., G.G., and I.T. performed samples and libraries preparation and collaborated to sequencing analyses; D.T. and F.L. performed the statistical and bioinformatics analyses; C.C., F.G., M.M., A.L, S.A., A.C and D.D. provided patient samples. F.DR., D.C., and R.M.L. revised the final version of manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the NCBI BioProject repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1,173,522), otherwise are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Elisa Gelli, Claudia Martinuzzi and Debora Soncini.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-79748-7.

References

- 1.Kumar, S. K. et al. Multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers3, 17046 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar, S. V. Multiple myeloma: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am. J. Hematol.95, 548–567 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcon, C. et al. Experts’ consensus on the definition and management of high risk multiple myeloma. Front. Oncol.12, 1096852 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larocca, A. et al. Patient-centered practice in elderly myeloma patients: an overview and consensus from the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Leukemia32, 1697–1712 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steensma, D. P. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood126, 9–16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solís-Moruno, M., Batlle-Masó, L., Bonet, N., Aróstegui, J. I. & Casals, F. Somatic genetic variation in healthy tissue and non-cancer diseases. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.31, 48–54 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaiswal, S. et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med.371, 2488–2498 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bejar, R. CHIP, ICUS, CCUS and other four-letter words. Leukemia31, 1869–1871 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young, A. L., Challen, G. A., Birmann, B. M. & Druley, T. E. Clonal haematopoiesis harbouring AML-associated mutations is ubiquitous in healthy adults. Nat. Commun.7, 12484 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombs, C. C. et al. Therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non-hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Cell Stem Cell21, 374-382.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson, C. J. et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes after autologous stem-cell transplantation for lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol.35, 1598–1605 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillis, N. K. et al. Clonal haemopoiesis and therapy-related myeloid malignancies in elderly patients: a proof-of-concept, case-control study. Lancet Oncol.18, 112–121 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel, R., Naishadham, D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin.63, 11–30 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie, M. et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat. Med.20, 1472–1478 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorsheimer, L. et al. Association of mutations contributing to clonal Hematopoiesis with prognosis in chronic ischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol.4, 25–33 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, P. G. et al. Association of clonal hematopoiesis with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Blood139, 357–368 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal, M. et al. TET2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis and risk of gout. Blood140, 1094–1103 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaiswal, S. et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med.377, 111–121 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, P. G. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood Adv.5, 2982–2986 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bejar, R. et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med.364, 2496–2506 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Ley, T. J., Miller, C., Ding, L., Raphael, B. J., Mungall, A. J. et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.368: 2059–74 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Papaemmanuil, E. et al. Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood122, 3616–27 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borsi, E. et al. Single-cell DNA sequencing reveals an evolutionary pattern of chip in transplant eligible multiple myeloma patients. Cells10.3390/cells13080657 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mouhieddine, T. H. et al. Clinical outcomes and evolution of clonal Hematopoiesis in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. Commun.3, 2560–2571 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mouhieddine, T. H. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis is associated with adverse outcomes in multiple myeloma patients undergoing transplant. Nat. Commun.11, 2996 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norris, J. R. et al. Correlation of paramagnetic states and molecular structure in bacterial photosynthetic reaction centers: the symmetry of the primary electron donor in Rhodopseudomonas viridis and Rhodobacter sphaeroides R-26. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA86, 4335–9 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becherini, P. et al. CD38-induced metabolic dysfunction primes multiple myeloma cells for NAD+-lowering agents. Antioxidants (Basel)10.3390/antiox12020494 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landrum, M. J. et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res.46, D1062–D1067 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rentzsch, P., Schubach, M., Shendure, J. & Kircher, M. CADD-Splice-improving genome-wide variant effect prediction using deep learning-derived splice scores. Genome Med.13, 31 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaiswal, S., Natarajan, P. & Ebert, B. L. Clonal Hematopoiesis and atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med.377, 1401–1402 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeZern, A. E., Malcovati, L. & Ebert, B. L. CHIP, CCUS, and other acronyms: definition, implications, and impact on practice. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book39, 400–410 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhee, J.-W. et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing hematopoietic cell transplant. JAMA Cardiol.9, 16–24 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Testa, S. et al. Prevalence, mutational spectrum and clinical implications of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential in plasma cell dyscrasias. Semin. Oncol.49, 465–475 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meier, J., Jensen, J. L., Dittus, C., Coombs, C. C. & Rubinstein, S. Game of clones: diverse implications for clonal Hematopoiesis in lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Blood Rev.56, 100986 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cook, G., Larocca, A., Facon, T., Zweegman, S. & Engelhardt, M. Defining the vulnerable patient with myeloma-a frailty position paper of the European Myeloma Network. Leukemia34, 2285–2294 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaiswal, S. & Ebert, B. L. Clonal Hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science10.1126/science.aan4673 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genovese, G. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl. J. Med.371, 2477–2487 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stelmach, P. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis with DNMT3A and PPM1D mutations impairs regeneration in autologous stem cell transplant recipients. Haematologica108, 3308–3320 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, N. et al. Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential predicts delayed platelet engraftment after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol.201, 577–580 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez, J. E., Micol, J. B. & Baldini, C. Exploring clonal hematopoiesis and its impact on aging, cancer, and patient care. Aging15, 14507–14508 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zweegman, S. & Larocca, A. Frailty in multiple myeloma: the need for harmony to prevent doing harm. Lancet Haematol.6, e117–e118 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mian, H. et al. The prevalence and outcomes of frail older adults in clinical trials in multiple myeloma: A systematic review. Blood Cancer J.13, 6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larocca, A., Cani, L., Bertuglia, G., Bruno, B. & Bringhen, S. New strategies for the treatment of older myeloma patients. Cancers (Basel)10.3390/cancers15102693 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Libby, P. & Ebert, B. L. CHIP (Clonal Hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential): Potent and newly recognized contributor to cardiovascular risk. Circulation138, 666–668 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the NCBI BioProject repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1,173,522), otherwise are available from the authors upon reasonable request.