Abstract

In adulthood, hen’s egg white allergy (EWA) is a rare condition and rising in prevalence. Typically, EWA begins in early childhood and resolves at school age. Persistence into adulthood or newly onset of the allergy has been reported, but scientific data is scarce. Symptoms reach from typical gastrointestinal problems to severe systemic reactions. EWA and the fear of allergic reactions lead to drastic restrictions in diet as in social life of the affected individuals. This study aims to assess health related quality of life (HRQoL) in adults with EWA using the validated questionnaire “Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire - adult form (FAQoLQ-AF)” and Food Allergy Independent Measure (FAIM). Between July 2023 and October 2023, 16 adults with hen’s egg white allergy were identified and questioned using the FAQoLQ-AF to evaluate HRQoL. Patients’ characteristics were obtained including age at allergy onset and the most severe allergic symptom. The results were summarized using descriptive statistical analysis. HRQoL was impaired in 16/16 allergic individuals with an overall mean score of 4.64/7 (SD 1.3). Self-assessed emotional impact of the EWA was more problematic than food allergy related health. Food Allergy Independence Measure (FAIM) mean score was 4.64 (SD 1.0) with highest result in product avoidance. The most frequent occurring symptoms were oral allergy syndrome and stomach pain in 7 (44%) patients each. This study shows impaired HRQoL in a small cohort of adults with hen’s egg white allergy using the FAQoLQ and FAIM questionnaire with special emphasis on emotional impact. We identified an urgent need for correct food labelling and research into safe treatment options to improve HRQoL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-80710-w.

Subject terms: Quality of life, Diseases

Introduction

While hen’s egg white allergy (EWA) is the second most common food allergy (FA) in children (prevalence 0.5–2.5%), it is rare in adults, with an estimated prevalence of 0.1%1–4. EWA in children mostly resolves by school age (up to 68% resolution until 16 years)2,5,6. Various epidemiologic studies have assessed the prevalence in adulthood, but the very rare adult-onset EWA alone has only been described in case reports and has been reported in association with atopic history1,6–8. Typical symptoms of EWA after allergen contact range from gastrointestinal symptoms, skin reactions and even to severe systemic reactions2.

Food allergies, including EWA, are on the rise worldwide1,9–12. FA are more prevalent at younger ages in the male population, but in adults, women are more frequently affected13. Through self-reported FA surveys and national surveys, it is suggested that the prevalence of food allergies in adults is higher than estimated12,14,15. Four major allergens have been identified in egg white (ovomucoid, ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, and lysozyme), and two main allergens in egg yolk (alpha-livetin and YGP42)10,11. In egg white, ovomucoid is considered the most clinically relevant component as it shows heat and gastric acid stability11. Studies about promising therapies such as oral immunotherapy or the use of biologics show promising but conflicting results16. Therefore, the total allergen elimination diet is the cornerstone of egg allergy management2,16. Still, constantly being alert about hidden allergens and fearing severe allergic reactions strongly interferes with social and emotional life17,18. Uncertainty and anxiety seem to have the most impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with food allergies19.

Data on cases with EWA in adults is rare, and so is assessment of HRQoL in those individuals. The aim of the study is to assess HRQoL explicitly in adults with hen’s egg white allergy with the validated Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire adult form (FAQoLQ -AF) and Food Allergy Independent Measures (FAIM), which is a widely used measurement tool for HRQoL in patients with food allergy and has been translated in different European languages19–22.

Distinguishing between hen’s egg white and egg yolk allergy is important for accurate diagnostics, targeted avoidance or therapy strategies and vaccine considerations. In this study, we refer to hen’s egg white allergy as EWA and strictly differ between egg white and egg yolk.

Methods

After ethical approval was obtained (BASEC Nr.: 2023 − 00391), we performed a retrospective cross-sectional cohort study. All research was performed in accordance with relevant regulations. Patients were included if general written consent and study-specific written consent were given. Only patients > 18 years at data collection were included in the study group, whereas age at contact could differ (be higher). The electronic laboratory record database at the Department of Allergology, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, was screened for patients with elevated specific IgE (sIgE) for egg white (f1), egg yolk (f75), ovalbumin (f232) or ovomucoid (f233) on ImmunoCAP OR sensitization on ISAC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) to the following allergens (nGal d1, nGal d2, nGal d3, nGal d5) between October 2015 and February 2022. sIgElevels of > 0.35 kUA/L were considered as positive on ImmunoCAP and values of 0.3 ISU were considered positive on ISAC. These patients were considered for further analysis. The electronic medical record database was screened for relevance of sensitization to egg proteins. The electronic medical record database was screened for relevance of sensitization to egg proteins.

The following clinical data were collected: gender, age, and clinically relevant sensitization, defined by any allergic or anaphylactic reaction following egg white consumption. The clinical symptoms were categorized based on Niggemann and Beyer’s grading system into seven grades: IA (oral allergy syndrome only), IB (oral allergy syndrome with rhinitis and/or conjunctivitis), IIA (isolated skin or gastrointestinal symptoms), IIB (both skin and gastrointestinal symptoms), IIIA (respiratory, cardiovascular, or neurological symptoms, or multiple organ involvement), IIIB (severe respiratory and/or cardiovascular symptoms, anaphylaxis without resuscitation), and IIIC (anaphylaxis with resuscitation)23.

The diagnosis of EWA was made by an allergologist at the department of allergology at the University Hospital of Zurich, Switzerland based on clinical history and test results (skin test and/or sIgE). All examinations were performed as part of the clinical routine without food challenge.

Three additional patients were identified through the routine clinical activities of the authors in the outpatient clinic and were invited to participate in the study. In these patients, the diagnosis of egg allergy was made based on a positive skin test and clinical history alone. In total, 18 participants received a questionnaire.

In a one-time validated questionnaire (FAQoLQ-AF and FAIM), the participants were questioned about their HRQoL considering the EWA. The questionnaire contains 29 items relating to four domains (Allergen Avoidance and Dietary Restrictions, Risk of Accidental Exposure, Food Allergy related Health and Emotional Impact)19. The Food Allergy Independent Measures (FAIM) consists of 6 items concerning perceived chance of accidental exposure (item a-d), product avoidance (item e) and impact on social life (item f). The questions are each scored on a 7-point scale, while higher scores indicate greater impairment in HRQoL (1 = no impairment, 7 = maximal impairment). 16/18 standard questionnaires were received back and completed between July 2023 and October 2023. 2/18 questionnaires were not received back due to address changes.

To supplement the data and further assess the EWA-related restrictions, the participants were asked to answer the following two questions:

At which age did the allergy manifest initially? (2) Which is the most severe symptom after contact with the hen’s egg allergen?

Statistical analysis

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics and frequency tabulation within Microsoft Excel Version 16.66.1. Data is expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD).

Results

13 female and three male participants were included in the study group. The median age of participants was 46 years (range, 19–71 years). Among the participants, 11 (69%) were diagnosed with adult-onset EWA, while 5 (31%) had the onset of EWA in childhood. The median age at allergy onset for the entire group was 27 years (range, 1–60), with participants experiencing adult-onset allergy presenting a median age of 37 years. Oral allergy syndrome (OAS, described as itchiness or swelling of the mouth, face, lip, tongue and throat) and stomach pain were both mentioned by 7 participants (44%) as the worst occurring symptom after egg white consumption. Furthermore, 6 participants (38%) described dyspnoea (grade IIIA based on Niggemann and Beyer). Furthermore, one person (6%) described a severe anaphylactic reaction with hypotension, respiratory and skin reaction with need of an emergency department visitation and management (grade IIIB based on Niggemann and Beyer). An overview over the patient’s characteristics, results of skin prick test, laboratory findings and score results of FAQoLQ and FAIM are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview for each patient’s most severe symptoms, sensitization to egg white and yolk allergen, laboratory findings and total score of FAQoLQ and FAIM sorted by grade*. *Based on Niggemann and Beyer’s grading system into seven grades: IA (oral allergy syndrome only), IB (oral allergy syndrome with rhinitis and/or conjunctivitis), IIA (isolated skin or gastrointestinal symptoms), IIB (both skin and gastrointestinal symptoms), IIIA (respiratory, cardiovascular, or neurological symptoms, or multiple organ involvement), IIIB (severe respiratory and/or cardiovascular symptoms, anaphylaxis without resuscitation), and IIIC (anaphylaxis with resuscitation) Key: ISU-E = ISAC standardised units, OAS = oral Allergy Syndrome, FAQoLQ = food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire FAIM = Food Allergy Independence measure.

| Grade* | Most severe Symptoms | Gender | Allergy onset | Skin Test | Total IgE [kU/l] | Egg white (f1)) [kU/l] | Ovomucoid (f233, nGAL d1) [kU/l] | Ovalbumin (f232, nGAL d2) [kU/l] | Ovotransferrin (nGAL d3) [kU/l] | Egg yolk (f75, nGAL d5) [kU/l] | Total FAQoLQ Score | Total FAIM score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IA | OAS | F | Adulthood | n.a. | 2842 | 0.35 | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | 1.9 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | 5.17 | 3.83 |

| 2 | IIA | OAS. angioedema | F | Childhood | n.a. | 897 | 1.62 | < 0.3 ISU-E | 0.8 ISU-E | 0.4 ISU-E | n.a. | 2.72 | 2.5 |

| 3 | IIA | Stomach pain | F | Adulthood | Positive | 367 | 1.5 | < 0.1 | 0.6 | n.a. | 4.4 | 3.6 | 4.3 |

| 4 | IIA | OAS, nausea | F | Adulthood | Positive | 31 | 0.6 | 2.5 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 4.2 |

| 5 | IIA | OAS, skin reaction | F | Adulthood | n.a. | 4247 | 13.9 | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | 0.4 ISU-E | n.a. | 4.1 | 3.83 |

| 6 | IIA | Stomach pain, nausea, vomiting | F | Adulthood | Positive | 157 | n.a. | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | 1.5 ISU-E | 4.41 | 2.5 |

| 7 | IIA | Stomach pain, nausea, vomiting | F | Childhood | Positive | n.a. | positive. | n.a. | n.a | n.a. | n.a. | 5.83 | 4.33 |

| 8 | IIA | Stomach pain, diarrhoea | F | Adulthood | Positive | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 6.03 | 4.83 |

| 9 | IIA | Stomach pain, nausea | F | Adulthood | Positive | n.a. | positive. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3.48 | 3.17 |

| 10 | IIA | Stomach pain, nausea | F | Childhood | Positive | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 4.17 | 3 |

| 11 | IIIA | Stomach pain, OAS, dyspnoea | F | Adulthood | Positive | 172 | 3.9 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | n.a. | 0.56 | 3.76 | 3.17 |

| 12 | IIIA | OAS, dyspnoea | M | Adulthood | n.a. | 1815 | 34.5 | 7.6 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | 2.38 | 2.67 |

| 13 | IIIA | Vomiting, dyspnoea | M | Adulthood | Positive | 4369 | 4.02 | 5.92 | 1.25 | n.a. | 0.5 | 4.9 | 3.83 |

| 14 | IIIA | OAS, angioedema, dyspnoea | M | Childhood | Positive | 427 | 73 | < 0.3 ISU_E | < 0.3 ISU-E | n.a. | 51.6 | 6.66 | 5.17 |

| 15 | IIIA | OAS, dyspnoea, skin reaction | F | Adulthood | Positive | 1145 | 0.96 | < 0.1 | 1.19 | < 0.3 ISU-E | < 0.3 ISU-E | 5.86 | 4.83 |

| 16 | IIIB | Anaphylactic shock, dyspnoea, OAS | F | Childhood | Positive | 111 | n.a. | 8.5 ISU-E | 1.6 ISU-E | 1.4 ISU-E | 0.5 ISU-E | 5.55 | 5.5 |

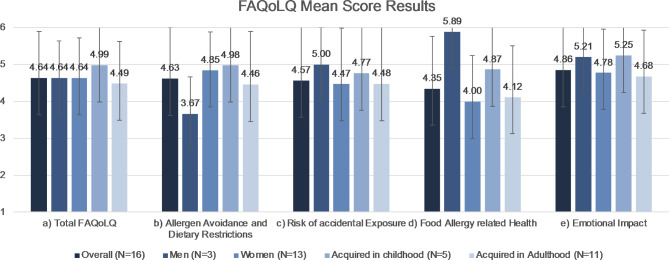

The study’s analysis of FAQoLQ results revealed an overall mean score (SD) of 4.64 (1.3), with no statistically significant gender-specific variations: both men and women averaging 4.64. Depending on age at allergy onset the mean score in participants with childhood onset lay at 4.99 (1.6) and in adulthood at 4.49 (1.1).

Examining the survey’s subsections, the mean scores (SD) were 4.63 (1.4) for Allergen Avoidance and Dietary Restriction, 4.57 (1.6) for Risk of Accidental Exposure, 4.35 (1.4) for Food Allergy related Health and 4.86 (1.4) for Emotional Impact. An overview and subsection analysis are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire (FAQoLQ) Mean Score Results. Error bars demonstrating SD. Further information is summarized in Table 2. Key: SD = standard deviation.

Items scoring at least 5/7 points on average (considered quite limiting) included limitations in product variety, loss of control while eating out, hesitancy to consume food if the participant has doubts about it containing egg white, and fear of displaying an allergic reaction while dining out. Experiencing allergic symptoms despite informing the host (chef and service staff) about the allergy, concern about incomplete labels when eating out and on products and feeling discouraged during an allergic reaction were rated at least as quite limiting (≥5/7 points in all patients).

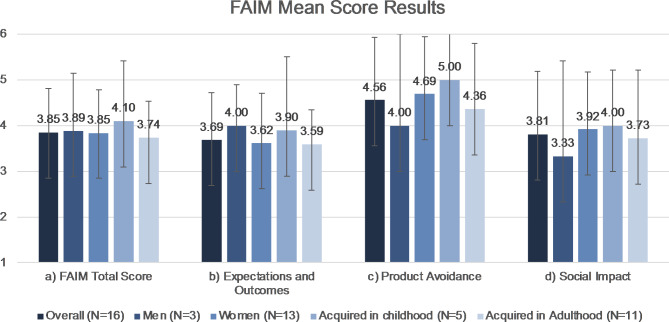

FAIM mean score was 4.64 (SD 1.0, Fig. 2). The chance of dying after hen’s egg white consumption as part of the FAIM Expectations and Outcomes was considered as low (mean 3, SD 1.6). Score results of product avoidance and impact on social life are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Fig. 2.

FAIM Mean Score Results. Error bars demonstrating SD. Further information is summarized in Table 2. Key: FAIM = Food Independent Measures, SD = standard deviation.

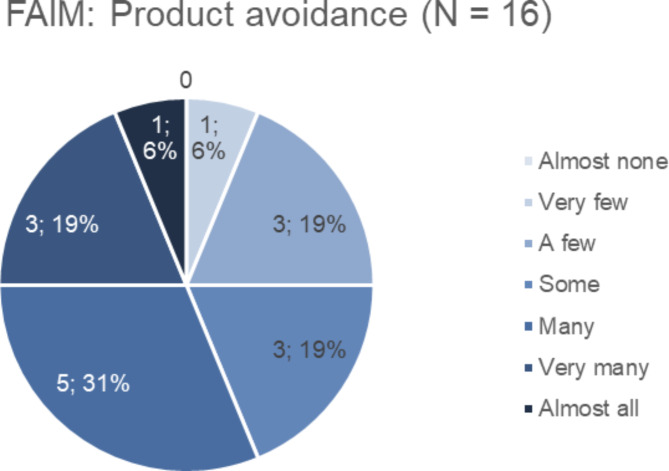

Fig. 3.

Product avoidance. Section results concerning product avoidance of the Food Allergy Independence Measure (FAIM) on a 7-scale score, 1 = almost none, 7 = almost all. Mean score 4.56 (SD 1.4). Key: FAIM = Food Allergy Independence Measure, SD = standard deviation.

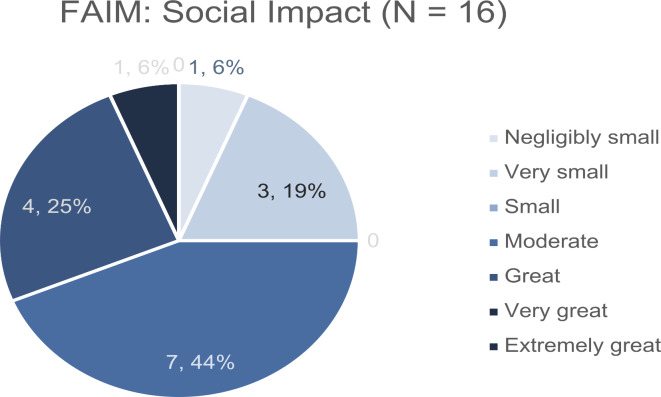

Fig. 4.

Social impact. Section results concerning social impact of the Food Allergy Independence Measure (FAIM) on a 7-scale score, 1 = almost none, 7 = almost all. Mean score 3.81 (SD 1.4). Key: FAIM = Food Allergy Independence Measure, SD = standard deviation.

In Table 2, all mean score results (SD) of the FAQoLQ and FAIM are shown for the overall study population, men and women, and childhood versus adulthood onset. The small group sizes did not allow a gender-specific statistical sub analysis. Additional information on score results of each patient for all subsections is found in Table S1 in the supplementary information.

Table 2.

Food allergy quality of life questionnaire mean score results. Mean score results of the FAQoLQ and FAIM on a 7-point scale with demonstration of subsections. Key: FAIM = food Allergy Independent measures; FAQoLQ = food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire, SD = standard deviation.

| Domain | Overall (N = 16) | Men (N = 3) | Women (N = 13) | Acquired in childhood (N = 5) | Acquired in adulthood (N = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAQoLQ | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Total | 4.64 (1.3) | 4.64 (2.2) | 4.64 (1.2) | 4.99 (1.6) | 4.49 (1.1) |

| Allergen Avoidance and Dietary Restriction | 4.63 (1.4) | 3.67 (2.4) | 4.85 (1.0) | 4.98 (1.3) | 4.46 (1.4) |

| Emotional Impact | 4.57 (1.6) | 5.0 (2.6) | 4.47 (1.5) | 4.77 (1.9) | 4.48 (1.5) |

| Risk of Accidental Exposure | 4.35 (1.4) | 5.89 (1.3) | 4.00 (1.3) | 4.87 (1.5) | 4.12 (1.4) |

| Food Allergy Related Health | 4.86 (1.4) | 5.21 (2.5) | 4.78 (1.2) | 5.25 (1.8) | 4.68 (1.2) |

| FAIM | |||||

| Total | 3.85 (1) | 3.89 (1.3) | 3.85 (0.9) | 4.10 (1.3) | 3.74 (0.8) |

| Expectation of Outcomes | 3.69 (1) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.62 (1.1) | 3.90 (1.6) | 3.60 (0.8) |

| Product Avoidance | 4.56 (1.4) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.69 (1.3) | 5.00 (1.2) | 4.36 (1.4) |

| Social Impact | 3.81 (1.4) | 3.33 (2.1) | 3.92 (1.3) | 4.00 (1.2) | 3.73 (1.5) |

Discussion

In this study, we showed impaired quality of life in adults with hen’s egg white allergy using the validated FAQoLQ-AF in a small cohort in Switzerland.

Patients’ characteristics

The difficulty in recruiting participants over 18 years of age with elevated sIgE against hen’s egg white proteins in combination with allergic reactions is consistent with the current estimated prevalence of less than 0.1% in different countries and cohorts worldwide2,24–26. More of our patients were female, although there is still no clear consensus on the gender-specific prevalence in the current literature concerning food allergies13,27,28. Considering the increased possibility of egg allergy in children, we could identify more participants with adult-onset allergy than those with onset in childhood5.

Measurement of specific IgE (sIgE) levels against egg proteins is a crucial diagnostic tool, alongside medical history and skin prick tests. A positive correlation has been observed between elevated sIgE values and the potential for clinical reactions; however, the absence of detectable sIgE does not rule out clinically relevant sensitization32. The allergenicity of egg white proteins has been associated with their heat stability and the presence of sequential or conformational epitopes32. In a small study, Järvinen et al. suggested that more conformational epitopes of sIgE antibodies against ovomucoid and ovalbumin could explain the persistence of egg allergy in children33. In our patients with allergy onset in childhood only one had significant high levels of sIgE against ovomucoid. In some patients with adult-onset allergy, higher sIgE levels to ovomucoid were linked to more severe symptoms and poorer questionnaire scores, although this was not consistent across all patients. This variability highlights the complex relationship between sIgE levels and clinical reactivity, especially in cases where sIgE is undetectable. It is also important to note that hen’s egg white allergy (EWA) may involve not only IgE-mediated responses but also cell-mediated mechanisms. To better understand the prevalence of severe allergic reactions to egg white in adults and their correlation with sIgE levels, larger epidemiological studies are needed.

Health-related quality of life

Using the FAQoLQ to assess impairments and limitations in personal and social life and health, all our participants were at least moderately restricted. HRQoL in food-allergic individuals has been evaluated in different studies18,29,30. Anna Nowak-Wegrzyn et al. examined the impact on peanut-allergic adults’ HRQoL using the FAQoLQ in 2021. Their adult population mean score results were similar to our study group with an overall mean score of 4.6 (SD 1.4), and the same applies to the subsections (Allergen Avoidance 4.69, Emotional Impact 4.78, Food Allergy Related Health 4.4 and Risk of Accidental Exposure 4.7)31.

OAS and stomach pain were the most reported disturbing symptoms by seven participants each, which matches the current understanding of EWA symptoms in the literature2. Those milder gastrointestinal allergic reactions, in our patients mostly Grade IIA based on Niggemann and Beyer, could be the reason for a not-as-pronounced score result in food allergy related health. Six patients did mention dyspnea after egg white contact, but only one of our participants described a systemic reaction with the need for hospitalization. It might be expected that more severe reactions would correlate with higher questionnaire scores; however, our results are not entirely conclusive. Instead, they suggest that EWA primarily causes limitations due to its everyday nature, a factor that applies to all of our patients.

Allergen avoidance as the most secure management option is strongly interfering with HRQoL of our patients. Several research groups have investigated oral immunotherapy (OIT) in food allergies3,16,34. This has been marked as a promising form of therapy16,35. A Cochrane systematic review in 2022 studied different studies comparing OIT with egg avoidance or placebo in children only, while in 2018 a study from Mäntylä et al. included four adults with egg allergy35,36. It has been shown that with OIT desensitization is achieved, but always bears a risk of adverse events including severe anaphylaxis36.

Our survey results indicate that emotional impact was more problematic than the other FAQoLQ subsections. Hidese et al. aimed to examine the association between food allergies and psychiatric distress and detected food allergy as a possible risk factor for depression or psychiatric distress37. Furthermore, a link has been made between food allergy and psychiatric diseases, and Coelho et al. have developed a measurement to assess the anxiety scale of people with food allergy37,38. In the FAQoLQ, psychiatric distress was not asked especially, so the anxiety scale of Coelho et al. could be applied to patients with EWA in the future for more information.

Labeling

Food labelling is crucial for patients with EWA. Still, as seen in the answers in the FAQoLQ, the risk of accidentally eating something wrong and the uncertainty due to incorrect or incomplete food labeling is interfering with HRQoL. This concerns explicitly sudden changes in the composition of ingredients of known products. Another difficulty is eating out, where components vary, and an allergen list is not always complete. Fear of food is not only present in food allergies but also in other diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, vomiting, and choking phobias, as shown by Zickgraf et al. using and validating a questionnaire39. Here, too, the significant restriction that exists in everyday life was emphasized, which exists with symptoms after accidental consumption of certain foods39. Precise training of service staff and chefs will be necessary in the future given the generally increasing prevalence of food allergies. Furthermore, internationally regulated allergen labeling could reduce the fear of food and create a most secure environment for adults with EWA40.

Differing hen’s egg yolk allergy and egg white allergy

In most papers reviewed for this study, EWA is only called “egg allergy.” The term must be more specified in the future regarding more accurate and diagnostical tools. The difference in allergen composition and major allergens in EWA and yolk allergy are essential. In the latest studies, alpha-livetin (Gal d 5), the major egg yolk allergen, was linked to the bird-egg syndrome10,11,41. The bird-egg syndrome describes a cross-reactivity with initial inhalative allergen exposure to bird dust and the development of a food allergy to hen’s egg yolk proteins, mainly induced by alpha-livetin41.

Furthermore, Uneoka et al. detected fewer respiratory allergic reactions in patients with egg yolk allergy than in those with egg white allergy42. On the other hand, patients with EWA showed significantly more gastrointestinal symptoms42. These findings may be of further importance when thinking of allergy management for example using immunotherapy safely in the future. We suggest differing strictly between hen’s egg white and yolk allergy, which was one goal of this study.

Limitation

This study is limited by the low number of participants, which can be explained by the rarity of EWA in adults. Another limitation was the lack of a control group, but we assumed a healthy individual is not limited in any of the asked questions in the FAQoLQ. Assessing HRQoL is strongly subjective, as is coping with a food allergy. Patients who were seen in the department of allergology in a university hospital were recruited based on positive sIgE against egg white proteins and through clinical routine. We hypothesize that patients needing allergy specialists may have a more severe or complicated history of allergies and do not represent the broader population. There is a need for more extensive survey and multi-centered studies including the general population with EWA in adults in the future.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into impaired HRQoL, specifically in adults with EWA. We identified an urgent need for correct food labeling in stores and restaurants to improve patients’ safety, lessen fear, and reduce the incidence of allergic symptoms.

Rarity and diagnostic challenges make it difficult to diagnose an EWA in adults. This also limits research into treatment options. However, due to the recently described increase in food allergies and the restrictions in everyday life that can also be observed in our patients, this should be an incentive for further research into a safe and effective treatment option such as OIT or even biologicals. Since our study group was very small, we recommend a validation in a bigger patient cohort in a multicentric setting, preferably. Furthermore, with the improvement in diagnostic tools and the newest knowledge of different allergens in hen’s egg, it should be strictly differed between egg white and egg yolk allergy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to this study conception and design. Andrea Nolting was responsible for the study design and idea, collected and analysed the data and was mainly involved in drafting the manuscript. Carole Guillet contributed to the design and was involved in drafting the manuscript. Elsbeth Probst-Mueller was involved in collecting patient’s data and proofreading. Susann Hasler and Joana Lanz supervised the study design and were involved in proofreading the manuscript. Peter Schmid-Grendelmeier was the overall study coordinator and was involved in proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cremonte, E. M., Galdi, E., Roncallo, C., Boni, E. & Cremonte, L. G. Adult onset egg allergy: A case report. Clin. Mol. Allergy Oct.04 (1), 17. 10.1186/s12948-021-00156-7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leech, S. C. et al. BSACI 2021 guideline for the management of egg allergy. Clin. Exp. Allergy Oct.51 (10), 1262–1278. 10.1111/cea.14009 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anagnostou, A. Optimizing patient care in Egg Allergy diagnosis and treatment. J. Asthma Allergy. 14, 621–628. 10.2147/JAA.S283307 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rona, R. J. et al. The prevalence of food allergy: A meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Sep.120 (3), 638–646. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.026 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savage, J., Sicherer, S. & Wood, R. The natural history of Food Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016 Mar-Apr. 4 (2), 196–203. 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.11.024 (2016). quiz 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, J. H. Clinical and Laboratory predictors of Egg Allergy Resolution in Children. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. Jul. 11 (4), 446–449. 10.4168/aair.2019.11.4.446 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unsel, M. et al. New onset egg allergy in an adult. J. Investig Allergol. Clin. Immunol.17 (1), 55–58 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nwaru, B. I. et al. Prevalence of common food allergies in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Aug. 69 (8), 992–1007. 10.1111/all.12423 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almodallal, Y., Weaver, A. L. & Joshi, A. Y. Population-based incidence of food allergies in Olmsted County over 17 years. Allergy Asthma Proc. Jan 01. ;43(1):44–49. doi: (2022). 10.2500/aap.2022.43.210088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Urisu, A., Kondo, Y. & Tsuge, I. Hen’s Egg Allergy. Chem. Immunol. Allergy. 101, 124–130. 10.1159/000375416 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhanapala, P., De Silva, C., Doran, T. & Suphioglu, C. Cracking the egg: An insight into egg hypersensitivity. Mol. Immunol. Aug. 66 (2), 375–383. 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.04.016 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verrill, L., Bruns, R. & Luccioli, S. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in U.S. adults: 2001, 2006, and 2010. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015 Nov-Dec. ;36(6):458 – 67. doi: (2015). 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Pali-Schöll, I. & Jensen-Jarolim, E. Gender aspects in food allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Jun. 19 (3), 249–255. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000529 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta, R. S. et al. Prevalence and severity of Food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 01 04. 2 (1), e185630. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5630 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sicherer, S. H. & Sampson, H. A. Food allergy: A review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.01 (1), 41–58. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.003 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Silva, D. et al. Rodríguez Del Río P, Allergen immunotherapy and/or biologicals for IgE-mediated food allergy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. Jan 09. ;doi: (2022). 10.1111/all.15211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.van der Velde, J. L., Dubois, A. E. & Flokstra-de Blok, B. M. Food allergy and quality of life: What have we learned? Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. Dec.13 (6), 651–661. 10.1007/s11882-013-0391-7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao, S. et al. Improvement in Health-Related Quality of Life in Food-allergic patients: A Meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract.10 (10), 3705–3714. 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.05.020 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flokstra-de Blok, B. M. et al. Development and validation of the Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire - Adult Form. Allergy Aug. 64 (8), 1209–1217. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01968.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren, C. M., Jiang, J. & Gupta, R. S. Epidemiology and Burden of Food Allergy. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. Feb. 14 (2), 6. 10.1007/s11882-020-0898-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Velde, J. L. et al. Test-retest reliability of the Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaires (FAQLQ) for children, adolescents and adults. Qual. Life Res. Mar.18 (2), 245–251. 10.1007/s11136-008-9434-2 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coelho, G. L. H., Lloyd, M., Tang, M. L. K. & DunnGalvin, A. The Short Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire (FAQLQ-12) for adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. May. 11 (5), 1522–1527e5. 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.02.018 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niggemann, B. & Beyer, K. Time for a new grading system for allergic reactions? Allergy Feb. 71 (2), 135–136. 10.1111/all.12765 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burney, P. G. et al. The prevalence and distribution of food sensitization in European adults. Allergy Mar.69 (3), 365–371. 10.1111/all.12341 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nachshon, L. et al. The prevalence of Food Allergy in Young Israeli adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019 Nov - Dec.7 (8), 2782–2789e4. 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.046 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz Segura, L. T., Figueroa Pérez, E., Nowak-Wegrzyn, A., Siepmann, T. & Larenas-Linnemann, D. Food allergen sensitization patterns in a large allergic population in Mexico. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2020 Nov - Dec.48 (6), 553–559. 10.1016/j.aller.2020.02.004 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loh, W. & Tang, M. L. K. The epidemiology of Food Allergy in the global context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health Sep.18 (9). 10.3390/ijerph15092043 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.De Martinis, M., Sirufo, M. M., Suppa, M., Di Silvestre, D. & Ginaldi, L. Sex and gender aspects for patient stratification in Allergy Prevention and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Feb. 24 (4). 10.3390/ijms21041535 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Protudjer, J. L. P. & Abrams, E. M. Enhancing Health-Related Quality of Life among those living with Food Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract.10 (10), 3715–3716. 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.003 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antolín-Amérigo, D. et al. Quality of life in patients with food allergy. Clin. Mol. Allergy. 14, 4. 10.1186/s12948-016-0041-4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. et al. The Peanut Allergy Burden Study: Impact on the quality of life of patients and caregivers. World Allergy Organ. J. Feb. 14 (2), 100512. 10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100512 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caubet, J. C. & Wang, J. Apr. Current understanding of egg allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am. ;58(2):427 – 43, xi. doi: (2011). 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Järvinen, K. M. et al. Specificity of IgE antibodies to sequential epitopes of hen’s egg ovomucoid as a marker for persistence of egg allergy. Allergy Jul. 62 (7), 758–765. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01332.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dona, D. W. & Suphioglu, C. Egg Allergy: Diagnosis and immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Jul. 16 (14). 10.3390/ijms21145010 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Romantsik, O., Tosca, M. A., Zappettini, S. & Calevo, M. G. Oral and sublingual immunotherapy for egg allergy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.04, 20. 10.1002/14651858.CD010638.pub3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mäntylä, J. et al. The effect of oral immunotherapy treatment in severe IgE mediated milk, peanut, and egg allergy in adults. Immun. Inflamm. Dis.06 (2), 307–311. 10.1002/iid3.218 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hidese, S., Nogawa, S., Saito, K. & Kunugi, H. Food allergy is associated with depression and psychological distress: A web-based study in 11,876 Japanese. J. Affect. Disord. 02 15, 245:213–218. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.119 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coelho, G. L. H., Byrne, A., Hourihane, J. & DunnGalvin, A. Development of the Food Allergy Anxiety Scale in an Adult Population: Psychometric parameters and convergent validity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract.09 (9), 3452–3458e1. 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.019 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zickgraf, H. F., Loftus, P., Gibbons, B., Cohen, L. C. & Hunt, M. G. If I could survive without eating, it would be a huge relief: Development and initial validation of the fear of Food Questionnaire. Appetite 02 01. 169, 105808. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105808 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiocchi, A. et al. Food labeling issues for severe food allergic patients. World Allergy Organ. J. Oct.14 (10), 100598. 10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100598 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hemmer, W., Klug, C. & Swoboda, I. Update on the bird-egg syndrome and genuine poultry meat allergy. Allergo J. Int. 2016. 25, 68–75. 10.1007/s40629-016-0108-2 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uneoka, K. et al. Differences in allergic symptoms after the consumption of egg yolk and egg white. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. Sep.25 (1), 97. 10.1186/s13223-021-00599-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.