Abstract

Background

HLA-G is associated with cancer cell escape. The 3′UTR polymorphism is involved in the regulation of membrane-bound HLA-G and soluble HLA-G proteins. The aim of our study was to assess the association of the HLA-G 14-bp insertion (I)/deletion (D) polymorphism with cancer susceptibility and its interaction with clinicopathological features and environmental factors.

Methods

A meta-analysis was performed to investigate the association between the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and different types of cancers according to the Prisma guidelines.

Results

Thirty-nine publications that studied the 14-bp I/D polymorphism in cancers met our inclusion criteria. The findings of the meta-analysis showed a significant association between the 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk under the allelic contrast model D vs. I (OR = 1,112, 95 % CI = 1,009–1,227; P = 0,033) suggesting that the D allele was a risk factor for cancer susceptibility. Stratification by cancer type demonstrated a significant association of the 14-bp I/D polymorphism with breast cancer under the D vs. I contrast allele model (OR = 1,267, 95 % CI = 1,028–1,563; P = 0,027). No significant association was found for digestive, cervical, haematological and thyroid cancers. A comparison of groups stratified by ethnicity showed a significant association for Caucasians under the D vs. I model (OR = 1,147, 95 % CI = 1,002–1,313; P = 0,047); and for mixed ethnicities under the DD + DI vs. II (OR = 1,388, 95 % CI = 1,083–1,780; P = 0,010) and DI vs. II (OR = 1,402, 95 % CI = 1,077–1,824; P = 0,012) models. A comparison of cancer risks associated with the 14-bp I/D polymorphism according to geographic location revealed significant risks for the D allele and DD genotype in North Africa, the Middle East and South America. However, no significant susceptibility to cancer associated with the 14-bp I/D polymorphism was shown for Europe and North Asia. The findings of a meta-analysis of subgroups by disease stage showed a significant association in both early and advanced stages, with the 14-bp deletion variant being a risk factor. Similarly, a significant cancer risk was shown for the 14-bp deletion variant in both low- and high-grade cancers. Finally, the risk associated with the 14-bp I/D polymorphism was higher in cancers with concomitant viral infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Conclusion

The findings of the overall meta-analysis showed a significant association between the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer susceptibility. The findings stratified analysis and subgroup comparisons showed that the 14-bp I/D deletion variant was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. The HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism may interact with individual and clinicopathological factors to alter cancer risk. These promising findings for cancer risk provide the basis for further studies that explore 14bp I/D polymorphism in cancer screening and immunotherapeutic approach.

Keywords: HLA-G gene, 14-bp I/D polymorphism, Cancer, Meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G), is a non-classical major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) antigen [1] encoded by a gene located in region 6p21.3 of chromosome 6 [2]. HLA-G is predominantly expressed at the maternal–fetal interface [3], and has primarily been associated with maternal-fetal tolerance [1]. HLA-G protects the fetus from trophoblast damage caused by maternal natural killer (NK) cells [4] and cytotoxic-T cells (CTLs) [5]. HLA-G is secreted under restrictive physiological conditions in fetal tissues, adult immune-privileged organs and cells of the hematopoietic lineage [1]. HLA-G is also found in pathological conditions such as cancer, viral infections, inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases, and transplantation [6]. In cancer, HLA-G expression is heterogeneous and strongly associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment, advanced tumor stage, poor therapeutic response, and poor prognosis [7,8].

The first identified and most studied polymorphism of the HLA-G gene is the 14-base-pair insertion/deletion (14-bp I/D) located in the 3′UTR (rs66554220/rs371194629) [9]. The 14-bp presence or absence (insertion or deletion, respectively) polymorphism was found to be associated with HLA-G transcript levels and mRNA stability. The presence of a 14-base segment has been shown to be associated with decreased mRNA production, and the absence of this segment (deletion) appears to stabilize mRNA enhancing HLA-G expression [10,11]. HLA-G transcripts presenting the 14-base segment can be further processed by removing 92 bases from the primary mRNA transcript [10], giving rise to a shorter HLA-G transcript reported to be more stable than the full-length isoform [12]. Taken together, the published results provide evidence for a direct relationship between the 14-bp I/D polymorphism and HLA-G protein expression.

Evidence is accumulating for an important role of the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism in various cancers, but the results of some studies are contradictory or inconclusive. In the current meta-analysis, data from published individual studies were pooled to further explore the association between the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer and shed light on the most significant modulating factors investigated in the primary studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Identification of eligible studies and data extraction

We searched for published studies investigating the association between the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases (up to October 2024) using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and keyword combinations, such as “HLA-G, “14-bp I/D polymorphism” and “cancer”. Furthermore, additional studies not indexed by the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases were included, and the references cited in the collected papers were reviewed. Studies were considered eligible based on the following inclusion criteria: testing for the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism in cancers and in healthy controls. Studies were excluded if they: (1) included redundant or incomplete data or (2) were reviews, meta-analyses or case reports. From each study, the following information was extracted: primary author, publication year, country of the study, ethnicity, allele and genotype frequencies of the HLA-G 14-bp polymorphism, type of cancer, stage/grade of cancer, and viral infection status. Two independent reviewers KT and IZI extracted the data on the methods and results from the original studies and analyzed them. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus among the reviewers. The meta-analysis was conducted according to the recommendations in the PRISMA guidelines [13].

2.2. Statistical analyses

We performed a meta-analysis to test the allelic, recessive, homozygous, dominant and codominant models of the HLA-G 14-bp polymorphism. For dichotomous data, odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Heterogeneity was quantified using I2, varying from 0 to 100 % and reflecting the proportion of variation between the studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance [13]. I2 values of 25, 50, and 75 % were considered to indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. The random-effects model assumes that there is significant variation in different studies and, therefore, tests both sampling errors within the study and variances between studies [14]. The tau squared (τ2) test reflects the variance of the true effect sizes, and is used to test the variance of the effect size parameters across the study population while tau (τ) is the estimated standard deviation of underlying true effects across studies [15]. Publication bias was assessed by using Egger's test [16]. A comprehensive meta-analysis program (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) was used to perform statistical manipulations.

3. Results

3.1. Studies included in the meta-analysis

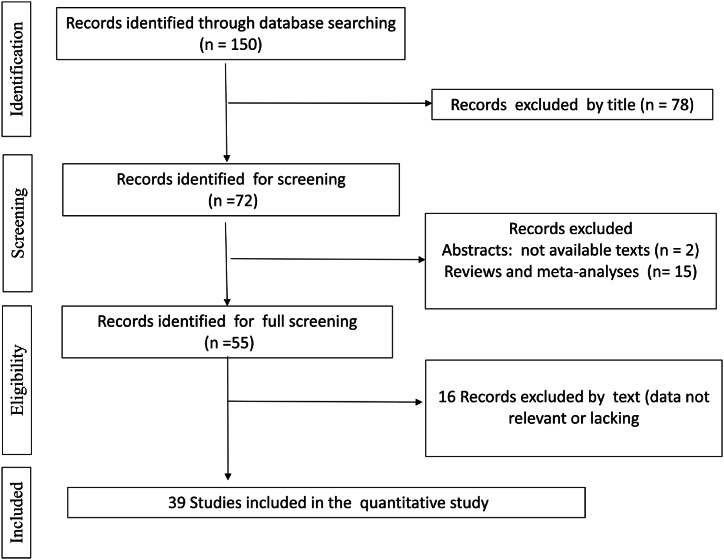

We identified 150 studies using electronic and manual search methods; of these, 72 were selected for full-text screening based on the title and abstract. Reviews or meta-analyses (15) studies for which the full texts were not available (2), and studies with missing or irrelevant data (16) were excluded. Therefore, in total, 39 articles met our inclusion criteria [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55]]: (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author | Cancer Type | Country | Geographic location | Ethnicity | Chi2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durmanova 2024 | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Slovakia | Europe | Caucasian | 0,680 |

| Okumura 2024 | Hepatocellular Cancer | Japan | North Asia | Asian | 0,955 |

| Becerra-Loaiza 2023 | Breast Cancer | Mexico | South America | Mixed | 0,803 |

| Garrach2023 | Colorectal Cancer | Tunisia | North Africa | Caucasian | 0,265 |

| Al-Tamimi 2022 | Leukemia | Saudi Arabia | Middle East | Caucasian | 3,022 |

| Bucova 2022 | Glioma | Slovakia | Europe | Caucasian | 0,609 |

| Dhouioui 2022 | Colorectal Cancer | Tunisia | North Africa | Caucasian | 0,951 |

| Gan 2022 | Cervical Cancer | China | North Asia | Asian | 0,863 |

| Haghi 2021 | Breast cancer | Iran | Middle East | Caucasian | 0,846 |

| de Magalhaes 2021 | Glioma | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 6,397 |

| Vaquero-Yuste 2021 | Gastric Cancer | Spain | Europe | Caucasian | 0,279 |

| Kadiam 2020 | Breast Cancer | India | South Asia | Caucasian | 0,043 |

| Abu hassan 2019 | Colorectal Cancer | Saudi Arabia | Middle East | Caucasian | 0,416 |

| El Bassiouny 2019 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Egypt | Middle East | Caucasian | 0,800 |

| Al Omar 2019 | Breast Cancer | Saudi Arabia | Middle East | Caucasian | 1,037 |

| Ouni 2019 | Breast Cancer | Tunisia | North Africa | Caucasian | 1183 |

| Tawfeek 2018 | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | Egypt | Middle East | Caucasian | 0,694 |

| Agnihotri 2017 | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | India | South Asia | Caucasian | 2,331 |

| de Figueiredo-Feitosa 2017 | Thyroid carcinoma | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 2,735 |

| Marques 2017 | Colorectal cancer | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 0,425 |

| Garziera 2016 | Colorectal Cancer | Italy | Europe | Caucasian | 5,666 |

| Zambra 2016 | Prostate Cancer | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 0,843 |

| Zidi 2016 | Breast Cancer | Tunisia | North Africa | Caucasian | 0,049 |

| Bielska 2015 | Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma | Poland | Europe | Caucasian | 5,301 |

| Haghi 2015 | Breast Cancer | Iran | Middle East | Caucasian | 11,033 |

| Wisniewski 2015 | Lung cancer | Poland | Europe | Caucasian | 0,265 |

| Bortolotti 2014 | Cervical cancer | Italy | Europe | Caucasian | 3,204 |

| Jeong 2014 | Breast Cancer | South Korea | North Asia | Asian | 0,356 |

| Ramos 2014 | Breast Cancer | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 0,106 |

| Yang 2014 | Cervical cancer | Taiwan | North Asia | Asian | 0,325 |

| Eskandarani-Nasab 2013 | Breast Cancer | Iran | Middle East | Caucasian | 1,996 |

| Kim 2013 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | South Korea | North Asia | Asian | 0,346 |

| Silva 2013 | Cervical Cancer | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 2,527 |

| Teixeira 2013 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Brazil | South America | Mixed | 3,167 |

| Chen 2012 | Esophageal cancer | China | North Asia | Asian | 0,320 |

| Dardano 2012 | Thyroid Carcinoma | Italy | Europe | Caucasian | 1,789 |

| Ferguson 2012 | Cervical cancer | Canada | North America | Caucasian | 0,521 |

| Jiang 2011 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | China | North Asia | Asian | 0,392 |

| Lau 2011 | Neuroblastoma | Newzeland | Australia | Caucasian | 0,001 |

Bold: Control population not in Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (at ddl = 1, α = 5 %, Chi2 = 3,83).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic review and meta-analysis literature search results (HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer).

Meta-analysis of the association between the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer susceptibility: Overall analysis.

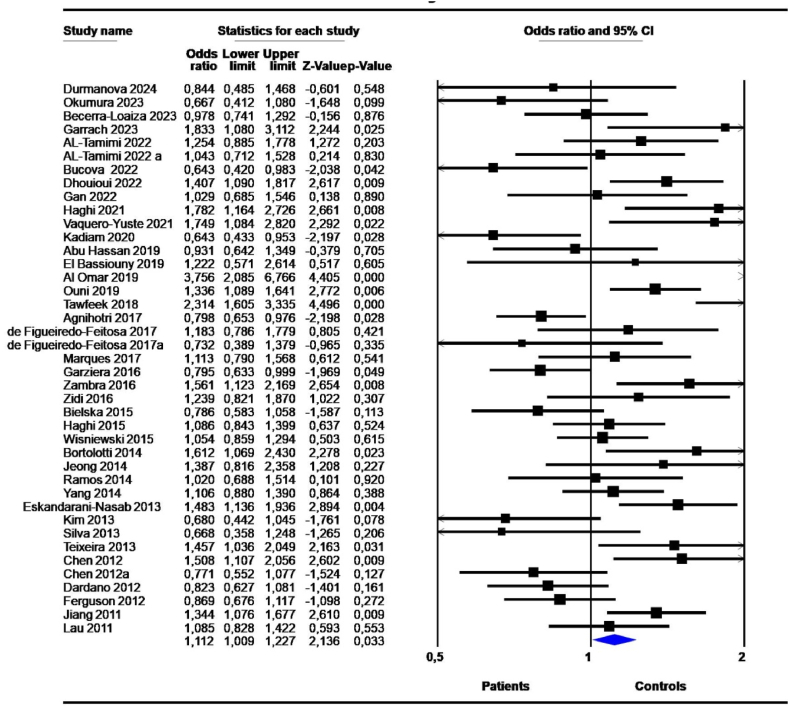

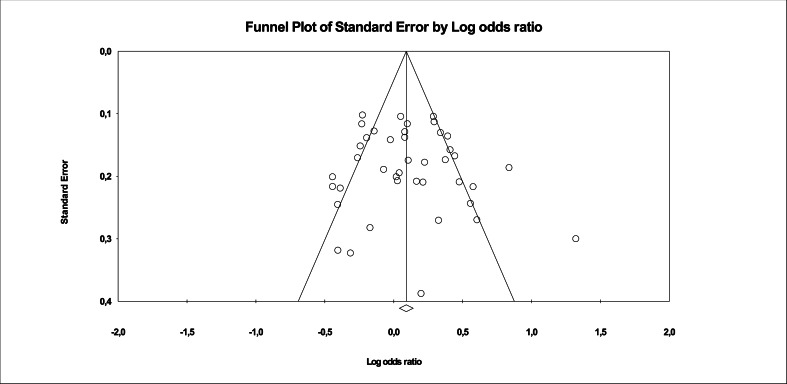

The results of the meta-analysis showed a significant association between the 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk under the D vs. I contrast allele model (OR = 1,112, 95 % CI = 1,009–1,227; P = 0,033) (Table 2, Fig. 2). High heterogeneity (I2 >50 %) and Tau squared varying between 0.067 and 0,240 were observed. The P-value for heterogeneity was significant (P-het<0,05). The observed heterogeneity and interstudy variance were not surprising given the clinicopathological features and population differences among studies. Publication bias was not significant in any model (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Association between HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers under the random effects model: Overall analysis.

| Genetic models | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P- het | τ2 | P-Begg (2-tailed) | P-Egger (2-tailed) | |

| D vs. I | 41 | 1,112 | 1,009 | 1,227 | 0,033 | 71,301 | 0,000 | 0,067 | NS | NS |

| DD vs. DI + II | 41 | 1,125 | 0,988 | 1,279 | 0,075 | 63,601 | 0,000 | 0,102 | NS | NS |

| DD + DI vs. II | 41 | 1,169 | 0,986 | 1,386 | 0,072 | 67,020 | 0,000 | 0,182 | NS | NS |

| DD + II vs. DI | 41 | 1,015 | 0,905 | 1,139 | 0,799 | 59,400 | 0,000 | 0,076 | NS | NS |

| DI vs. II | 41 | 1,124 | 0,944 | 1,338 | 0,190 | 64,314 | 0,000 | 0,184 | NS | NS |

| DD vs. II | 41 | 1,210 | 0,996 | 1,469 | 0,055 | 67,116 | 0,000 | 0,238 | NS | NS |

| DD vs. DI | 41 | 1,093 | 0,961 | 1,243 | 0,175 | 58,435 | 0,000 | 0,093 | NS | NS |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers risk with the random effects model under the allele contrast model D vs. I. Forest plot shows the odds ratio and respective 95 % confidence intervals for the different studies included in the meta-analysis. For each study in the forest plot, the area of the black square is proportional to study weight and the horizontal bar represents the 95 % confidence interval. Z-score: the standardized expression of a value in terms of its relative position in the full distribution of values. CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of the association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers risk with the random effects model under the allele contrast model D vs. I.

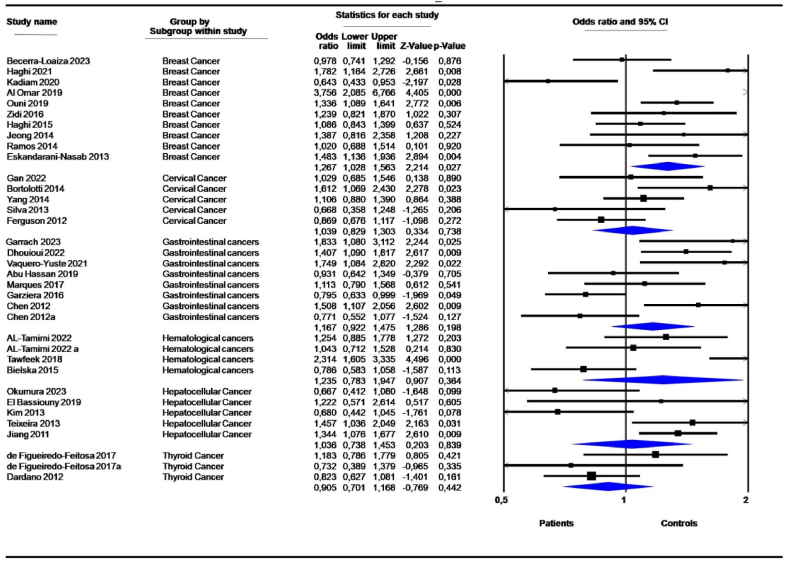

3.2. Subgroup analysis according to different types of cancer

Stratification by cancer type demonstrated a significant association of the 14-bp I/D polymorphism with breast cancer (10 studies) under the D vs. I contrast allele model (OR = 1,267, 95 % CI = 1,028–1,563; P = 0,027) (Table 3, Fig. 4). No significant association was shown for digestive, cervical, hematological and thyroid cancers (Table 3). Neuroblastoma (1 study), glioma (2 studies), lung cancer (1 study), and head and neck cancer (2 studies) were underrepresented to be analyzed as subgroups. Heterogeneity and variance among studies were significantly reduced compared to the overall analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers: Subgroup analysis according to cancer type.

| Genetic models | Subgroups | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P-het | τ2 | P-Begg | P-Egger | ||

| D vs. I | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,267 | 1,028 | 1,563 | 0,027 | 73,711 | 0,000 | 0,079 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 1,039 | 0,829 | 1,303 | 0,738 | 53,186 | 0,074 | 0,033 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,167 | 0,922 | 1,475 | 0,198 | 74,651 | 0,000 | 0,082 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 1,235 | 0,783 | 1,947 | 0,364 | 85,510 | 0,000 | 0,184 | NS | NS | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,036 | 0,738 | 1,453 | 0,839 | 72,277 | 0,006 | 0,100 | NS | NS | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 0,905 | 0,701 | 1,168 | 0,442 | 21,142 | 0,281 | 0,012 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI + II | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,327 | 0,998 | 1,764 | 0,052 | 66,171 | 0,002 | 0,133 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 1,167 | 0,880 | 1,547 | 0,284 | 42,385 | 0,139 | 0,041 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,268 | 0,934 | 1,722 | 0,129 | 67,068 | 0,003 | 0,125 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 1,193 | 0,907 | 1,570 | 0,207 | 0,000 | 0,696 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,049 | 0,693 | 1,588 | 0,821 | 67,398 | 0,015 | 0,136 | NS | NS | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 0,725 | 0,433 | 1,213 | 0,221 | 49,692 | 0,137 | 0,101 | NS | NS | |

| DD + DI vs. II | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,292 | 0,961 | 1,738 | 0,090 | 54,626 | 0,019 | 0,107 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 0,953 | 0,564 | 1,608 | 0,856 | 69,446 | 0,011 | 0,231 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,126 | 0,796 | 1,593 | 0,503 | 62,146 | 0,010 | 0,147 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 1,666 | 0,529 | 5,248 | 0,384 | 92,751 | 0,000 | 1,265 | NS | NS | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,207 | 0,745 | 1,957 | 0,444 | 31,853 | 0,209 | 0,094 | NS | 0,027 | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 1,093 | 0,746 | 1,602 | 0,648 | 0,000 | 0,544 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD + II vs. DI | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,045 | 0,870 | 1,256 | 0,635 | 33,768 | 0,138 | 0,028 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 1,155 | 0,752 | 1,774 | 0,510 | 74,296 | 0,004 | 0,167 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,131 | 0,944 | 1,355 | 0,181 | 18,635 | 0,282 | 0,013 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 0,875 | 0,446 | 1,714 | 0,696 | 86,496 | 0,000 | 0,407 | NS | NS | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,025 | 0,793 | 1,325 | 0,850 | 24,524 | 0,258 | 0,021 | NS | NS | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 0,696 | 0,461 | 1,050 | 0,084 | 35,298 | 0,213 | 0,048 | NS | NS | |

| DI vs. II | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,215 | 0,929 | 1,589 | 0,155 | 39,910 | 0,092 | 0,066 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 0,907 | 0,475 | 1,734 | 0,769 | 76,439 | 0,002 | 0,395 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,001 | 0,740 | 1,355 | 0,993 | 43,154 | 0,091 | 0,078 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 1,627 | 0,475 | 5,569 | 0,439 | 92,852 | 0,000 | 1,458 | NS | 0,033 | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,206 | 0,823 | 1,769 | 0,336 | 0,000 | 0,529 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 1,276 | 0,851 | 1,914 | 0,239 | 0,000 | 0,551 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. II | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,415 | 0,969 | 2,066 | 0,073 | 61,711 | 0,005 | 0,201 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 0,993 | 0,626 | 1,573 | 0,975 | 53,162 | 0,074 | 0,136 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,313 | 0,834 | 2,068 | 0,239 | 71,795 | 0,001 | 0,293 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 1,744 | 0,617 | 4,932 | 0,294 | 87,871 | 0,000 | 0,982 | NS | NS | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,191 | 0,632 | 2,245 | 0,589 | 52,374 | 0,078 | 0,250 | NS | NS | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 0,875 | 0,546 | 1,402 | 0,579 | 7,236 | 0,340 | 0,016 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI | Breast Cancer | 10 | 1,239 | 0,960 | 1,599 | 0,099 | 52,710 | 0,025 | 0,085 | NS | NS |

| Cervical Cancer | 5 | 1,190 | 0,802 | 1,765 | 0,387 | 63,618 | 0,027 | 0,119 | NS | NS | |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 8 | 1,247 | 0,947 | 1,643 | 0,116 | 53,477 | 0,035 | 0,081 | NS | NS | |

| Hematological cancers | 4 | 1,116 | 0,832 | 1,498 | 0,463 | 0,000 | 0,707 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| Hepatocellular Cancer | 5 | 1,042 | 0,728 | 1,492 | 0,823 | 52,922 | 0,075 | 0,082 | NS | NS | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 3 | 0,661 | 0,390 | 1,123 | 0,126 | 47,118 | 0,151 | 0,102 | NS | NS | |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk: Subgroup analysis according to cancer type under the allele contrast model D vs. I.

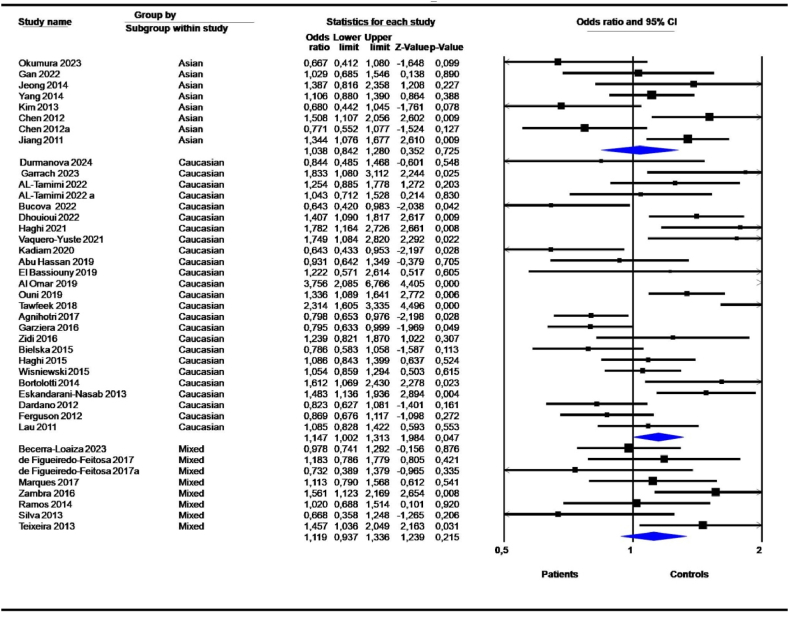

3.3. Subgroup analysis according to ethnicity

Stratification by ethnicity showed significant association for Caucasians under the D vs. I model (OR = 1,147, 95 % CI = 1,002–1,313; P = 0,047) (Table 4). Mixed ethnicities showed significant associations (DD + DI vs. II; OR = 1,388, 95 % CI = 1,083–1,780; P = 0,010, and DI vs. II; OR = 1,402, 95 % CI = 1,077–1,824; P = 0,012) (Table 4). The allelic contrast model showed no significant association (Fig. 5). After stratification by ethnicity, Caucasian and mixed ethnic heterogeneity remained significant, while Asian heterogeneity was low to moderate (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers: Subgroup analysis according to ethnicity.

| Genetic Model | Subgroups | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P- het | τ2 | P-Begg | P-Egger | ||

| D vs. I | Asian | 8 | 1,038 | 0,842 | 1,280 | 0,725 | 67,069 | 0,003 | 0,057 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,147 | 1,002 | 1,313 | 0,047 | 77,366 | 0,000 | 0,085 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 1,119 | 0,937 | 1,336 | 0,215 | 40,153 | 0,111 | 0,025 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI + II | Asian | 8 | 1,072 | 0,832 | 1,382 | 0,589 | 61,501 | 0,011 | 0,077 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,190 | 0,997 | 1,421 | 0,054 | 68,172 | 0,000 | 0,127 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 0,995 | 0,727 | 1,361 | 0,975 | 56,372 | 0,025 | 0,108 | 0,035 | 0,016 | |

| DD + DI vs. II | Asian | 8 | 1,014 | 0,679 | 1,516 | 0,945 | 51,926 | 0,042 | 0,159 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,160 | 0,925 | 1,455 | 0,199 | 75,085 | 0,000 | 0,223 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 1,388 | 1,083 | 1,780 | 0,010 | 0,000 | 0,494 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD + II vs. DI | Asian | 8 | 1,084 | 0,881 | 1,333 | 0,447 | 42,273 | 0,096 | 0,036 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,056 | 0,905 | 1,232 | 0,492 | 64,727 | 0,000 | 0,092 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 0,831 | 0,630 | 1,095 | 0,188 | 50,701 | 0,048 | 0,077 | NS | 0,029 | |

| DI vs. II | Asian | 8 | 0,965 | 0,660 | 1,411 | 0,856 | 41,664 | 0,101 | 0,116 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,096 | 0,868 | 1,384 | 0,441 | 72,929 | 0,000 | 0,230 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 1,402 | 1,077 | 1,824 | 0,012 | 0,000 | 0,507 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. II | Asian | 8 | 1,030 | 0,648 | 1,637 | 0,901 | 60,023 | 0,014 | 0,244 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,253 | 0,967 | 1,624 | 0,089 | 74,234 | 0,000 | 0,290 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 1,332 | 0,949 | 1,868 | 0,097 | 27,200 | 0,211 | 0,063 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI | Asian | 8 | 1,091 | 0,858 | 1,389 | 0,477 | 52,875 | 0,038 | 0,060 | NS | NS |

| Caucasian | 25 | 1,159 | 0,973 | 1,380 | 0,098 | 62,321 | 0,000 | 0,113 | NS | NS | |

| Mixed | 8 | 0,898 | 0,644 | 1,252 | 0,526 | 56,542 | 0,024 | 0,122 | NS | 0,010 | |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk with the random effects model: Subgroup analysis according to ethnicity under the allele contrast model D vs. I.

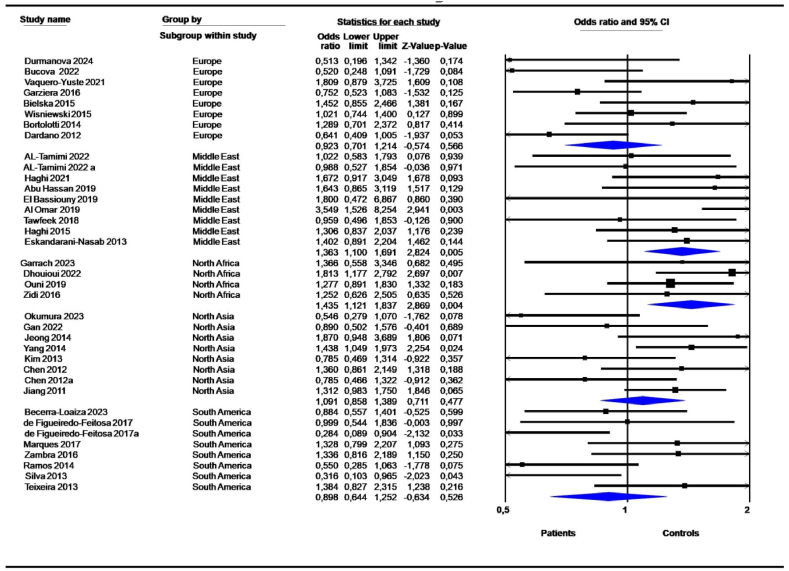

3.4. Subgroup analysis according to geographic locations

The 14-bp I/D polymorphism was linked to cancers in all geographic locations; however the most significant associations were detected in North Africa (D vs. I, OR = 1,377, 95 % CI = 1,193–1,590; P = 0,000; DD vs. DI + II, OR = 1,561, 95 % CI = 1,241–1,964; P = 0,000; DD + DI vs. II, OR = 1,442, 95 % CI = 1,145–1,816; P = 0,002; DD vs. II, OR = 1,800, 95 % CI = 1,362–2,378; P = 0,000; DD vs. DI, OR = 1,435, 95 % CI = 1,121–1,837; P = 0,004) (Table 5, Fig. 6). Similarly, the 14-bp I/D polymorphism was highly associated with cancers in the Middle East (D vs. I, OR = 1,453, 95 % CI = 1,135–1,860; P = 0,003; DD vs. DI + II, OR = 1,529, 95 % CI = 1,201–1,945; P = 0,001; DD + DI vs. II, OR = 1,718, 95 % CI = 1,015–2,908; P = 0,044; DD vs. II, OR = 2,024, 95 % CI = 1,205–3,398; P = 0,008); DD vs. DI, OR = 1,363, 95 % CI = 1,100–1,691; P = 0,005) (Table 5, Fig. 6). Eight studies from South America showed a high risk of 14-bp deletion variants under the DD + DI vs. II (OR = 1,388, 95 % CI = 1,083–1,780; P = 0,010) and DI vs. II (OR = 1,402, 95 % CI = 1,077–1,824; P = 0,012) models (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers: Subgroup analysis according to geographic locations.

| Genetic models | Subgroup | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P-het | τ2 | P-Begg | P-Egger | ||

| D vs. I | Europe | 8 | 0,956 | 0,780 | 1,171 | 0,663 | 67,979 | 0,003 | 0,054 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 1,453 | 1,135 | 1,860 | 0,003 | 73,911 | 0,000 | 0,099 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,377 | 1,193 | 1,590 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,686 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 1,038 | 0,842 | 1,280 | 0,725 | 67,069 | 0,003 | 0,057 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 1,119 | 0,937 | 1,336 | 0,215 | 40,153 | 0,111 | 0,025 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI + II | Europe | 8 | 0,925 | 0,697 | 1,229 | 0,591 | 61,591 | 0,011 | 0,095 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 1,529 | 1,201 | 1,945 | 0,001 | 35,193 | 0,136 | 0,046 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,561 | 1,241 | 1,964 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,772 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 1,072 | 0,832 | 1,382 | 0,589 | 61,501 | 0,011 | 0,077 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 0,995 | 0,727 | 1,361 | 0,975 | 56,372 | 0,025 | 0,108 | 0,035 | 0,016 | |

| DD + DI vs. II | Europe | 8 | 0,961 | 0,692 | 1,332 | 0,809 | 59,872 | 0,015 | 0,122 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 1,718 | 1,015 | 2,908 | 0,044 | 80,203 | 0,000 | 0,460 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,442 | 1,145 | 1,816 | 0,002 | 0,000 | 0,552 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 1,014 | 0,679 | 1,516 | 0,945 | 51,926 | 0,042 | 0,159 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 1,388 | 1,083 | 1,780 | 0,010 | 0,000 | 0,494 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD + II vs. DI | Europe | 8 | 0,980 | 0,774 | 1,240 | 0,867 | 52,634 | 0,039 | 0,056 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 1,051 | 0,779 | 1,420 | 0,743 | 65,155 | 0,003 | 0,130 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,066 | 0,863 | 1,316 | 0,555 | 4,432 | 0,371 | 0,002 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 1,084 | 0,881 | 1,333 | 0,447 | 42,273 | 0,096 | 0,036 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 0,831 | 0,630 | 1,095 | 0,188 | 50,701 | 0,048 | 0,077 | NS | 0,029 | |

| DI vs. II | Europe | 8 | 0,976 | 0,712 | 1,340 | 0,883 | 51,854 | 0,042 | 0,099 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 1,550 | 0,893 | 2,689 | 0,119 | 79,568 | 0,000 | 0,502 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,259 | 0,982 | 1,614 | 0,069 | 0,000 | 0,407 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 0,965 | 0,660 | 1,411 | 0,856 | 41,664 | 0,101 | 0,116 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 1,402 | 1,077 | 1,824 | 0,012 | 0,000 | 0,507 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. II | Europe | 8 | 0,923 | 0,624 | 1,364 | 0,686 | 62,879 | 0,009 | 0,183 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 2,024 | 1,205 | 3,398 | 0,008 | 72,140 | 0,000 | 0,403 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,800 | 1,362 | 2,378 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,753 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 1,030 | 0,648 | 1,637 | 0,901 | 60,023 | 0,014 | 0,244 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 1,332 | 0,949 | 1,868 | 0,097 | 27,200 | 0,211 | 0,063 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI | Europe | 8 | 0,923 | 0,701 | 1,214 | 0,566 | 53,823 | 0,034 | 0,078 | NS | NS |

| Middle East | 9 | 1,363 | 1,100 | 1,691 | 0,005 | 11,404 | 0,340 | 0,012 | NS | NS | |

| North Africa | 4 | 1,435 | 1,121 | 1,837 | 0,004 | 0,000 | 0,640 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| North Asia | 8 | 1,091 | 0,858 | 1,389 | 0,477 | 52,875 | 0,038 | 0,060 | NS | NS | |

| South America | 8 | 0,898 | 0,644 | 1,252 | 0,526 | 56,542 | 0,024 | 0,122 | NS | 0,011 | |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk with the random effects model: Sub-group analysis according to geographic location under the codominant model DD vs. DI.

3.5. Subgroup analysis according to cancer stages, grades and concomitant viral infections

Subgroup analysis by disease stage (early stages (I + II) vs. advanced stages (III + IV)) showed a significant association under the allele contrast D vs. I model for both early (OR = 1,393, 95 % CI = 1,074–1,808; P = 0,013) and advanced (OR = 1,641, 95 % CI = 1,124–2,395; P = 0,010) stages (Table 6). We also found similar significant effect risks of the 14-bp deletion variant under the DD vs. DI + II and DD vs. II models for both early and advanced cancer stages (Table 6). However, the DD + DI vs. II model showed a significant association only in advanced stages (OR = 2,126, 95 % CI = 1,066–4,241; P = 0,032) (Table 6). We should note that caution should be taken when interpreting these results since only five studies were included for early stages, and only 4 studies were included in advanced stages.

Table 6.

Association between the 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers: Subgroup analysis according to cancer stages.

| Genetic models | Stages | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P-het | τ2 | P-Begg | P-Egger | ||

| D vs. I | Advanced stage | 4 | 1,641 | 1,124 | 2,395 | 0,010 | 70,69 | 0,017 | 0,103 | NS | NS |

| Early stage | 5 | 1,393 | 1,074 | 1,808 | 0,013 | 58,82 | 0,046 | 0,051 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI + II | Advanced stage | 4 | 1,501 | 1,064 | 2,118 | 0,021 | 16,90 | 0,307 | 0,021 | NS | NS |

| Early stage | 5 | 1,482 | 1,139 | 1,929 | 0,003 | 0,00 | 0,555 | 0,000 | 0,027 | NS | |

| DD + DI vs. II | Advanced stage | 4 | 2,126 | 1,066 | 4,241 | 0,032 | 65,79 | 0,033 | 0,294 | NS | NS |

| Early stage | 5 | 1,762 | 0,914 | 3,398 | 0,091 | 80,51 | 0,000 | 0,442 | NS | NS | |

| DD + II vs. DI | Advanced stage | 4 | 0,764 | 0.,572 | 1,020 | 0,068 | 8,49 | 0,351 | 0,008 | NS | NS |

| Early stage | 5 | 0,865 | 0,536 | 1,396 | 0,552 | 75,11 | 0,003 | 0,222 | NS | NS | |

| DI vs II | Advanced stage | 4 | 2,009 | 0,982 | 4,111 | 0,056 | 64,07 | 0,039 | 0,310 | NS | NS |

| Early stage | 5 | 1,642 | 0,801 | 3,366 | 0,176 | 81,60 | 0,000 | 0,537 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs II | Advanced stage | 4 | 2,558 | 1,120 | 5,845 | 0,026 | 67,60 | 0,026 | 0,441 | NS | NS |

| Early stage | 5 | 1,957 | 1,103 | 3,471 | 0,022 | 63,06 | 0,029 | 0,262 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs DI | Advanced stage | 4 | 1,168 | 0,842 | 1,619 | 0,352 | 0,00 | 0,714 | 0,000 | NS | 0,006 |

| Early stage | 5 | 1,282 | 0,950 | 1,729 | 0,104 | 9,46 | 0,352 | 0,011 | NS | 0,041 | |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs. Early stage includes stages I + II. Advanced stage includes stages III + IV.

For stratification by cancer grade, the association was more significant in low grades than in high grades under the D vs. I, DD vs. DI + II, DD + DI vs. II, DI vs. II and DD vs. II genetic models (Table 7). However, caution should be taken when interpreting these results due to the limited number of included studies. Notably, after stratification by cancer grade, the heterogeneity was not significant for any genetic model (P-het >0,05).

Table 7.

Association between the14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers: Subgroup analysis according to cancer grades.

| Genetic models | Grades | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P-het | τ2 | P-Begg | P-Egger | ||

| D vs. I | High grade | 4 | 1,288 | 0,992 | 1,672 | 0,057 | 19,13 | 0,295 | 0,014 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 1,354 | 1,148 | 1,597 | 0,000 | 0,00 | 0,604 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI + II | High grade | 4 | 1,529 | 1,079 | 2,166 | 0,017 | 0,00 | 0,484 | 0,000 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 1,451 | 1,111 | 1,896 | 0,006 | 3,52 | 0,387 | 0,004 | NS | NS | |

| DD + DI vs. II | High grade | 4 | 1,246 | 0,724 | 2,144 | 0,428 | 38,02 | 0,184 | 0,117 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 1,496 | 1,142 | 1,960 | 0,003 | 0,00 | 0,992 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD + II vs. DI | High grade | 4 | 1,121 | 0,746 | 1,685 | 0,581 | 31,65 | 0,222 | 0,055 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 0,978 | 0,774 | 1,235 | 0,850 | 0,00 | 0,623 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DI vs. II | High grade | 4 | 1,121 | 0,624 | 2,012 | 0,702 | 39,75 | 0,173 | 0,141 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 1,350 | 1,009 | 1,804 | 0,043 | 0,00 | 0,984 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. II | High grade | 4 | 1,573 | 0,908 | 2,724 | 0,106 | 22,46 | 0,276 | 0,074 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 1,768 | 1,281 | 2,440 | 0,001 | 0,00 | 0,781 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD vs. DI | High grade | 4 | 1,449 | 0,999 | 2,102 | 0,051 | 0,00 | 0,440 | 0,000 | NS | NS |

| Low grade | 5 | 1,296 | 0,973 | 1,726 | 0,076 | 3,14 | 0,389 | 0,004 | NS | NS | |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs. Low grade includes Grades I + II. Low grade includes Grades III + IV.

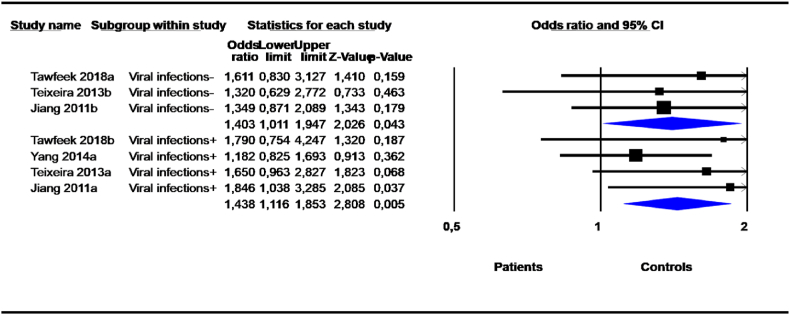

Stratification by viral infection status (viral infection vs. not) revealed highly significant risks of the 14-bp deletion variant in cancer patients with concomitant viral infection with either human papillomavirus (HPV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) under the D vs. I (OR = 1,555, 95 % CI = 1,031–2,346; P = 0,035), DD vs. DI + II (OR = 1,438, 95 % CI = 1,116–1,853; P = 0.005) and DD vs. DI (OR = 1,399, 95 % CI = 1,065–1,839; P = 0.016) models (Table 8, Fig. 7). No heterogeneity was revealed in the DD vs. DI + II and DD vs. DI genetic models.

Table 8.

Association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancers: Subgroup analysis according to viral infection.

| Genetic models | Viral infection | Effect size and 95 % interval |

Heterogeneity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | P-value | I2 | P-het | τ2 | P-Begg | P-Egger | ||

| D vs. I | Viral infections- | 3 | 1,523 | 1,002 | 2,316 | 0,049 | 67,63 | 0,046 | 0,092 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 1,555 | 1,031 | 2,346 | 0,035 | 76,35 | 0,005 | 0,132 | NS | 0,006 | |

| DD vs. DI + II | Viral infections- | 3 | 1,403 | 1,011 | 1,947 | 0,043 | 0,00 | 0,894 | 0,000 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 1,438 | 1,116 | 1,853 | 0,005 | 0,00 | 0,500 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

| DD + DI vs. II | Viral infections- | 3 | 2,412 | 0,610 | 9,536 | 0,209 | 87,72 | 0,000 | 1,291 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 2,163 | 0,704 | 6,646 | 0,178 | 85,47 | 0,000 | 1.077 | NS | 0,035 | |

| DD + II vs. DI | Viral infections- | 3 | 0,817 | 0,354 | 1,887 | 0,636 | 84,07 | 0,002 | 0,456 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 1,040 | 0,632 | 1,711 | 0,878 | 69,54 | 0,020 | 0,175 | NS | NS | |

| DI vs II | Viral infections- | 3 | 2,207 | 0,481 | 10,125 | 0,308 | 88,58 | 0,000 | 1,602 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 1,830 | 0,571 | 5,866 | 0,309 | 84,70 | 0,000 | 1,155 | NS | 0,029 | |

| DD vs II | Viral infections- | 3 | 2,551 | 0,745 | 8,742 | 0,136 | 81,78 | 0,004 | 0,964 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 2,421 | 0,804 | 7,288 | 0,116 | 83,13 | 0,000 | 1,003 | NS | 0,046 | |

| DD vs DI | Viral infections- | 3 | 1,218 | 0,855 | 1,733 | 0,275 | 0,00 | 0,684 | 0,000 | NS | NS |

| Viral infections+ | 4 | 1,399 | 1,065 | 1,839 | 0,016 | 0,00 | 0,892 | 0,000 | NS | NS | |

Bold: significant P-value (<0,05); N: number of studies; NS: Not Significant; OR: odds ratio; I2 : heterogeneity test; τ2 , tau-squared; I/D : insertion/deletion; P- het, p-heterogeneity ; bp: base pairs. The overall analysis gives estimations among subgroups; Viral infection+: presence infection; Viral infection-: absence infection.

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of the association between 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk with the random effects model: Subgroup analysis according to viral infection under DD vs. DI + II genetic model.

4. Discussion

In the current meta-analysis, independent results from studies related to the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism in various types of cancer (breast cancer, cervical cancer, gastrointestinal cancers, hepatocellular cancer, hematological cancers, and thyroid cancer) were pooled. With the meta-analysis, more accurate data were provided than with individual studies as the statistical power and analytical resolution were increased. We identified an association between the 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer. Our results are consistent with the results of the meta-analysis of Jiang et al., conducted in 2019, demonstrating that the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism may play an important role in reducing cancer susceptibility [56]. Interestingly, the results of a recent comprehensive meta-analysis by de Almeida et al., conducted in 2018, were inconclusive but suggested that other variation sites observed in the HLA-G 3′UTR have well-established roles in the posttranscriptional regulation of HLA-G expression, and the complete 3′UTR segment should be analyzed in terms of disease susceptibility rather than a single polymorphism [57].

In this meta-analysis, we showed that the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism may contribute to breast cancer susceptibility as found by Li et al. 2015 and Ge et al. (only for Asians) [58,59]. Elsewhere, the results of the meta-analysis of Zhang et al. suggested that the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism was not associated with total cancer risk but was associated with hepatocellular carcinoma risk [60]. In this meta-analysis, we did not find the same result. The discrepancies between study findings may be due to the differences in the number of included studies and the analytical methods used.

Interestingly, the results of our subgroup analysis showed that the 14-bp I/D polymorphism was associated with cancer in Caucasians, Asians, and mixed-race individuals. Moreover, the 14-bp polymorphism was associated with cancer in all geographic locations except Europe and North Asia. Particularly, in North Africa and in the Middle East, the DD genotype and D allele were significant risk factors for cancer.

The 14-bp deletion and insertion alleles have been extensively studied in relation to HLA-G molecule stability and expression. The presence of the 14 bases is associated with decreased mRNA production of most membrane-bound and soluble isoforms, and absence of this segment (deletion) results in mRNA stabilization and higher HLA-G expression [61,62]. The HLA-G transcript, which includes a 14-base segment, can be further processed by removing 92 bases from the complete mRNA [10], giving rise to a short HLA-G transcript reported to be more stable [12]. The results of published studies showed that the deletion variant increases HLA-G expression [7,63,64]. The deletion allele is usually associated with high levels of HLA-G allowing tumor progression. Furthermore, HLA-G expression was found to correlate with adverse clinicopathological parameters such as clinical stage, lymph node status, metastasis, and histologic grade, but not with tumor status [65].

The HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism affects the levels of surface and soluble HLA-G expression, and the overexpression of HLA-G molecules contributes to creating tolerogenic conditions [66]. HLA-G protein expression can be driven by genetic variations in the 3′UTR and in the promoter region. Svendsen et al. showed that 14-bp insertion at the HLA-G 3′UTR significantly increased the inhibition of natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity in the K562 cell line compared to the deleted form, while the ratio of the soluble to the membrane form of HLA-G1 was higher in those with the deletion [11]. Several data indicate that the 14-bp I/D polymorphism is in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with other HLA-G polymorphisms in the 5′ upstream regulatory region (5′URR) and 3′UTR, suggesting that in a higher or lower HLA-G expression, and some HLA haplotypes are in LD in some populations [67]. These observations show the importance of investigating LD in polymorphic studies in different populations [67].

Interestingly, five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the 3′UTR of the HLA-G gene are predicted to affect the miRNA target sites, and HLA-G deregulation serves as a prognostic marker in some cancers [68]. Furthermore, cancer-associated microenvironmental variability can affect HLA-G protein expression. Genetic variation in the 3′ UTR, which involves multiple target sites of microRNAs (miRNAs), regulates HLA-G expression at the posttranscriptional level [69]. Indeed, six miRNAs (miR-148a, miR-148b, miR-152, miR-133a, miR628-5p, and miR-548q) have been reported to regulate HLAG expression [69].

Importantly, HLA-G expression has been linked to high viral infection [70,71]. Indeed, several viruses, including HBV and HCV have been shown to induce the expression of HLA-G [72,73]. A progressive increase in HLA-G protein expression in HPV-infected cervix and cervical cancer has been reported [74]. Indeed, gradual upregulation of HLA-G expression favors HPV persistence in the submissive host response microenvironment, further leading to cervical cancer [74]. Both tumor cells and viruses employ a major common strategy to evade the host's immune response particularly the expression of HLA-G molecules that can modulate immune responses [[75], [76], [77], [78]]. In line with this hypothesis, we demonstrated that viral concomitant infection could enhance susceptibility to cancer. However, the limited number of primary studies leads us to take these results with caution.

It has become increasingly evident that the HLA-G molecule is involved in modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses and in promoting immune escape in various types of cancers [[10], [11], [12], [13]] and infectious diseases [[14], [15], [16]].

Finally, the findings of our meta-analysis showed an overall significant association between the HLA-G 14-bp I/D polymorphism and cancer risk. A major limitation of this meta-analysis was related to the limitation of primary studies that lacked information on gene-gene interactions, family history, tobacco smoking, treatment, and other regulating factors. Additionally, heterogeneity was found between individual studies and subgroups. This could be due to the etiological and physiopathological differences in the studied cancers, and to ethnicity differences.

5. Conclusion

The current meta-analysis is the most comprehensive and extensive study into how the HLA-G 14 bp I/D polymorphism is involved in cancer susceptibility. The 14 bp deletion was found to be a significant risk factor for susceptibility to cancer. The clinicopathological and environmental factors investigated here altered the risk of cancer, but their mechanisms of action need further investigation. Based on our results and previous functional studies, the 14 bp I/D polymorphism seems to be a good target for both cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kalthoum Tizaoui: Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis. Mohamed Ali Ayadi: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Ines Zemni: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. Abdel Halim Harrath: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. Roberta Rizzo: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. Nadia Boujelbene: Writing – original draft, Validation, Data curation. Inès Zidi: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Data availability

Data included in article material is referenced in the article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Ines Zidi is currently serving as an Associate Editor for Heliyon Immunology. Although she was not involved in the review of this specific manuscript, she is disclosing this position to ensure transparency and uphold the integrity of the review process for this submission. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Tunisia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R17) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Contributor Information

Kalthoum Tizaoui, Email: kalttizaoui@gmail.com.

Inès Zidi, Email: ines.zidi@istmt.utm.tn.

References

- 1.Carosella E.D., Favier B., Rouas-Freiss N., Moreau P., Lemaoult J. Beyond the increasing complexity of the immunomodulatory HLA-G molecule. Blood. 2008;111(10):4862–4870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koller B.H., Geraghty D.E., DeMars R., Duvick L., Rich S.S., Orr H.T. Chromosomal organization of the human major histocompatibility complex class I gene family. J. Exp. Med. 1989;169(2):469–480. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger D.S., Hogge W.A., Barmada M.M., Ferrell R.E. Comprehensive analysis of HLA-G: implications for recurrent spontaneous abortion. Reprod. Sci. 2010;17(4):331–338. doi: 10.1177/1933719109356802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouas-Freiss N., Goncalves R.M., Menier C., Dausset J., Carosella E.D. Direct evidence to support the role of HLA-G in protecting the fetus from maternal uterine natural killer cytolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94(21):11520–11525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Gal F.A., Riteau B., Sedlik C., Khalil-Daher I., Menier C., Dausset J., Guillet J.G., Carosella E.D., Rouas-Freiss N. HLA-G-mediated inhibition of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 1999;11(8):1351–1356. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.8.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amiot L., Ferrone S., Grosse-Wilde H., Seliger B. Biology of HLA-G in cancer: a candidate molecule for therapeutic intervention? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68(3):417–431. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0583-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alegre E., Rizzo R., Bortolotti D., Fernandez-Landazuri S., Fainardi E., Gonzalez A. Some basic aspects of HLA-G biology. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/657625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin A., Yan W.H. Human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G) expression in cancers: roles in immune evasion, metastasis and target for therapy. Mol. Med. 2015;21(1):782–791. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison G.A., Humphrey K.E., Jakobsen I.B., Cooper D.W. A 14 bp deletion polymorphism in the HLA-G gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993;2(12):2200. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2200-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hviid T.V., Hylenius S., Rorbye C., Nielsen L.G. HLA-G allelic variants are associated with differences in the HLA-G mRNA isoform profile and HLA-G mRNA levels. Immunogenetics. 2003;55(2):63–79. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svendsen S.G., Hantash B.M., Zhao L., Faber C., Bzorek M., Nissen M.H., Hviid T.V. The expression and functional activity of membrane-bound human leukocyte antigen-G1 are influenced by the 3'-untranslated region. Hum. Immunol. 2013;74(7):818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rousseau P., Le Discorde M., Mouillot G., Marcou C., Carosella E.D., Moreau P. The 14 bp deletion-insertion polymorphism in the 3' UT region of the HLA-G gene influences HLA-G mRNA stability. Hum. Immunol. 2003;64(11):1005–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.08.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Contr. Clin. Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borenstein M., Higgins J.P., Hedges L.V., Rothstein H.R. Basics of meta-analysis: I(2) is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods. 2017;8(1):5–18. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M., Smith G.D., Phillips A.N. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ. 1997;315(7121):1533–1537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu Hassan M., Al Omar S., Halawani H., Arafah M., Alqadheeb S., Al-Tamimi J., Mansour L. Relationship of HLA-G expression and its 14-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism with susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Genet. Mol. Res. 2019;18(2) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agnihotri V., Gupta A., Kumar R., Upadhyay A.D., Dwivedi S., Kumar L., Dey S. Promising link of HLA-G polymorphism, tobacco consumption and risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) in NorthNorth Indian population. Hum. Immunol. 2017;78(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Omar S.Y., Mansour L. Association of HLA-G 14-base pair insertion/deletion polymorphism with breast cancer in Saudi Arabia. Genet. Mol. Res. 2019;18(2) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Tamimi J., Al Omar S.Y., Al-Khulaifi F., Aljuaimlani A., Alharbi S.A., Al-jurayyan A., Mansour L. Evaluation of the relationships between HLA-G 14 bp polymorphism and two acute leukemia in a Saudi population. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022;34(6) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bielska M., Bojo M., Klimkiewicz-Wojciechowska G., Jesionek-Kupnicka D., Borowiec M., Kalinka-Warzocha E., Prochorec-Sobieszek M., Robak T., Warzocha K., Mlynarski W., Lech-Maranda E. Human leukocyte antigen-G polymorphisms influence the clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2015;54(3):185–193. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bortolotti D., Gentili V., Rotola A., Di Luca D., Rizzo R. Implication of HLA-G 3' untranslated region polymorphisms in human papillomavirus infection. Tissue Antigens. 2014;83(2):113–118. doi: 10.1111/tan.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucova M., Kluckova K., Kozak J., Rychly B., Suchankova M., Svajdler M., Matejcik V., Steno J., Zsemlye E., Durmanova V. HLA-G 14bp ins/del polymorphism, plasma level of soluble HLA-G, and association with IL-6/IL-10 ratio and survival of glioma patients. Diagnostics. 2022;12(5):1099. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12051099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y., Gao X.J., Deng Y.C., Zhang H.X. Relationship between HLA-G gene polymorphism and the susceptibility of esophageal cancer in Kazakh and Han nationality in Xinjiang. Biomarkers. 2012;17(1):9–15. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.633242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dardano A., Rizzo R., Polini A., Stignani M., Tognini S., Pasqualetti G., Ursino S., Colato C., Ferdeghini M., Baricordi O.R., Monzani F. Soluble human leukocyte antigen-g and its insertion/deletion polymorphism in papillary thyroid carcinoma: novel potential biomarkers of disease? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97(11):4080–4086. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Figueiredo-Feitosa N.L., Martelli Palomino G., Ciliao Alves D.C., Mendes Junior C.T., Donadi E.A., Maciel L.M. HLA-G 3' untranslated region polymorphic sites associated with increased HLA-G production are more frequent in patients exhibiting differentiated thyroid tumours. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017;86(4):597–605. doi: 10.1111/cen.13289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Magalhaes K., Silva K.R., Gomes N.A., Sadissou I., Carvalho G.T., Buzellin M.A., Tafuri L.S., Nunes C.B., Nunes M.B., Donadi E.A., da Silva I.L., Simoes R.T. HLA-G 14 bp In/Del and +3142 C/G genotypes are differentially expressed between patients with grade IV gliomas and controls. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021;131(4):327–335. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1744593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhouioui S., Laaribi A.-B., Boujelbene N., Jelassi R., Ben Salah H., Bellali H., Ouzari H.-I., Mezlini A., Zemni I., Chelbi H., Zidi I. Association of HLA-G 3′UTR polymorphisms and haplotypes with colorectal cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Hum. Immunol. 2022;83(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Bassiouny M.A., Elshaarawy A.A., Tawfeek G.A., Elashmawy M.I. Association of HLA-G gene polymorphism with hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptian population. Menoufia Medical Journal. 2019;32(1):255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskandari-Nasab E., Hashemi M., Hasani S.S., Omrani M., Taheri M., Mashhadi M.A. Association between HLA-G 3'UTR 14-bp ins/del polymorphism and susceptibility to breast cancer. Cancer Biomarkers. 2013;13(4):253–259. doi: 10.3233/CBM-130364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson R., Ramanakumar A.V., Koushik A., Coutlée F., Franco E., Roger M., the T. Biomarkers of Cervical Cancer Risk Study, Human leukocyte antigen G polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of invasive cancer of the uterine cervix. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131(3):E312–E319. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gan J., Di X.-H., Yan Z.-Y., Gao Y.-F., Xu H.-H. HLA-G 3’UTR polymorphism diplotypes and soluble HLA-G plasma levels impact cervical cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1076040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garziera M., Catamo E., Crovella S., Montico M., Cecchin E., Lonardi S., Mini E., Nobili S., Romanato L., Toffoli G. Association of the HLA-G 3'UTR polymorphisms with colorectal cancer in Italy: a first insight. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2016;43(1):32–39. doi: 10.1111/iji.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haghi M., Hosseinpour Feizi M.A., Sadeghizadeh M., Lotfi A.S. 14-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism of the HLA-G gene in breast cancer among women from North western Iran. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP. 2015;16(14):6155–6158. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.14.6155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haghi M., Ranjbar M., Karari K., Samadi-Miandoab S., Eftekhari A., Hosseinpour-Feizi M.A. Certain haplotypes of the 3'-UTR region of the HLA-G gene are linked to breast cancer. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021;78(2):87–91. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2020.1856495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong S., Park S., Park B.W., Park Y., Kwon O.J., Kim H.S. Human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G) polymorphism and expression in breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Y., Chen S., Jia S., Zhu Z., Gao X., Dong D., Gao Y. Association of HLA-G 3' UTR 14-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism with hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility in a Chinese population. DNA Cell Biol. 2011;30(12):1027–1032. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kadiam S., Ramasamy T., Ramakrishnan R., Mariakuttikan J. Association of HLA-G 3'UTR 14-bp Ins/Del polymorphism with breast cancer among South Indian women. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020;73(8):456–462. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2019-205772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S.K., Chung J.H., Jeon J.W., Park J.J., Cha J.M., Joo K.R., Lee J.I., Shin H.P. Association between HLA-G 14-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism and hepatocellular carcinoma in Korean patients with chronic hepatitis B viral infection. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2013;60(124):796–798. doi: 10.5754/hge11180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau D.T., Norris M.D., Marshall G.M., Haber M., Ashton L.J. HLA-G polymorphisms, genetic susceptibility, and clinical outcome in childhood neuroblastoma. Tissue Antigens. 2011;78(6):421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2011.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marques D., Ferreira-Costa L.R., Ferreira-Costa L.L., Correa R.D.S., Borges A.M.P., Ito F.R., Ramos C.C.O., Bortolin R.H., Luchessi A.D., Ribeiro-Dos-Santos A., Santos S., Silbiger V.N. Association of insertion-deletions polymorphisms with colorectal cancer risk and clinical features. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23(37):6854–6867. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ouni N., Chaaben A.B., Kablouti G., Ayari F., Douik H., Abaza H., Gara S., Elgaaied-Benammar A., Guemira F., Tamouza R. The impact of HLA-G 3'UTR polymorphisms in breast cancer in a Tunisian population. Immunol. Invest. 2019;48(5):521–532. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2019.1569043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramos C.S., Goncalves A.S., Marinho L.C., Gomes Avelino M.A., Saddi V.A., Lopes A.C., Simoes R.T., Wastowski I.J. Analysis of HLA-G gene polymorphism and protein expression in invasive breast ductal carcinoma. Hum. Immunol. 2014;75(7):667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silva I.D., Muniz Y.C., Sousa M.C., Silva K.R., Castelli E.C., Filho J.C., Osta A.P., Lima M.I., Simoes R.T. HLA-G 3'UTR polymorphisms in high grade and invasive cervico-vaginal cancer. Hum. Immunol. 2013;74(4):452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tawfeek G.A., Alhassanin S. HLA-G gene polymorphism in Egyptian patients with non-hodgkin lymphoma and its clinical outcome. Immunol. Invest. 2018;47(3):315–325. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2018.1430826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teixeira A.C., Mendes-Junior C.T., Souza F.F., Marano L.A., Deghaide N.H., Ferreira S.C., Mente E.D., Sankarankutty A.K., Elias-Junior J., Castro-e-Silva O., Donadi E.A., Martinelli A.L. The 14bp-deletion allele in the HLA-G gene confers susceptibility to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Brazilian population. Tissue Antigens. 2013;81(6):408–413. doi: 10.1111/tan.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaquero-Yuste C., Juarez I., Molina-Alejandre M., Molanes-Lopez E.M., Lopez-Nares A., Suarez-Trujillo F., Gutierrez-Calvo A., Lopez-Garcia A., Lasa I., Gomez R., Fernandez-Cruz E., Rodrigez-Sainz C., Arnaiz-Villena A., Martin-Villa J.M. HLA-G 3'UTR polymorphisms are linked to susceptibility and survival in Spanish gastric adenocarcinoma patients. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.698438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wisniewski A., Kowal A., Wyrodek E., Nowak I., Majorczyk E., Wagner M., Pawlak-Adamska E., Jankowska R., Slesak B., Frydecka I., Kusnierczyk P. Genetic polymorphisms and expression of HLA-G and its receptors, KIR2DL4 and LILRB1, in non-small cell lung cancer. Tissue Antigens. 2015;85(6):466–475. doi: 10.1111/tan.12561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Y.C., Chang T.Y., Chen T.C., Lin W.S., Chang S.C., Lee Y.J. Human leucocyte antigen-G polymorphisms are associated with cervical squamous cell carcinoma risk in Taiwanese women. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50(2):469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zambra F.M., Biolchi V., de Cerqueira C.C., Brum I.S., Castelli E.C., Chies J.A. Immunogenetics of prostate cancer and benign hyperplasia--the potential use of an HLA-G variant as a tag SNP for prostate cancer risk. HLA. 2016;87(2):79–88. doi: 10.1111/tan.12741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zidi I., Dziri O., Zidi N., Sebai R., Boujelebene N., Ben Hassine A., Ben Yahia H., Laaribi A.B., Babay W., Rifi H., Mezlini A., Chelbi H. Association of HLA-G +3142 C>G polymorphism and breast cancer in Tunisian population. Immunol. Res. 2016;64(4):961–968. doi: 10.1007/s12026-015-8782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Durmanova V., Tedla M., Rada D., Bandzuchova H., Kuba D., Suchankova M., Ocenasova A., Bucova M. Analysis of HLA-G 14 bp insertion/deletion polymorphism and HLA-G, ILT2 and ILT4 expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Diseases. 2024;12(2):34. doi: 10.3390/diseases12020034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okumura T., Joshita S., Yamazaki T., Iwadare T., Wakabayashi S.-i., Kobayashi H., Yamashita Y., Sugiura A., Kimura T., Ota M., Umemura T. HLA-G susceptibility to hepatitis B infection and related hepatocellular carcinoma in the Japanese population. Hum. Immunol. 2023;84(8):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2023.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becerra-Loaiza D.S., Roldan Flores L.F., Ochoa-Ramírez L.A., Gutiérrez-Zepeda B.M., Del Toro-Arreola A., Franco-Topete R.A., Morán-Mendoza A., Oceguera-Villanueva A., Topete A., Javalera D., Quintero-Ramos A., Daneri-Navarro A. HLA-G 14 bp ins/del (rs66554220) variant is not associated with breast cancer in women from western Mexico. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023:6842–6850. doi: 10.3390/cimb45080432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garrach B., Ben Othmen A., Khamlaoui W., Yatouji S., Toumi I., Zaied S., Zouari K., Hammami M., Hammami S. Association of HLA-G 3' untranslated region indel polymorphism and its serum expression with susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Biomarkers Med. 2023;17(12):541–552. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2023-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang Y., Lu J., Wu Y.E., Zhao X., Li L. Genetic variation in the HLA-G 3'UTR 14-bp insertion/deletion and the associated cancer risk: evidence from 25 case-control studies. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39(5) doi: 10.1042/BSR20181991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Almeida B.S., Muniz Y.C.N., Prompt A.H., Castelli E.C., Mendes-Junior C.T., Donadi E.A. Genetic association between HLA-G 14-bp polymorphism and diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Immunol. 2018;79(10):724–735. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ge Y.Z., Ge Q., Li M.H., Shi G.M., Xu X., Xu L.W., Xu Z., Lu T.Z., Wu R., Zhou L.H., Wu J.P., Liang K., Dou Q.L., Zhu J.G., Li W.C., Jia R.P. Association between human leukocyte antigen-G 14-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Hum. Immunol. 2014;75(8):827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li T., Huang H., Liao D., Ling H., Su B., Cai M. Genetic polymorphism in HLA-G 3'UTR 14-bp ins/del and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis of case-control study. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015;290(4):1235–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0985-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang S., Tao Wang H. Association between HLA-G 14-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J BUON. 2014;19(2):567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hviid T.V., Rizzo R., Christiansen O.B., Melchiorri L., Lindhard A., Baricordi O.R. HLA-G and IL-10 in serum in relation to HLA-G genotype and polymorphisms. Immunogenetics. 2004;56(3):135–141. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0673-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Svendsen S.G., Udsen M.S., Daouya M., Funck T., Wu C.L., Carosella E.D., LeMaoult J., Hviid T.V.F., Faber C., Nissen M.H. Expression and differential regulation of HLA-G isoforms in the retinal pigment epithelial cell line, ARPE-19. Hum. Immunol. 2017;78(5–6):414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnaiz-Villena A., Juarez I., Suarez-Trujillo F., Lopez-Nares A., Vaquero C., Palacio-Gruber J., Martin-Villa J.M. HLA-G: function, polymorphisms and pathology. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2021;48(2):172–192. doi: 10.1111/iji.12513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donadi E.A., Castelli E.C., Arnaiz-Villena A., Roger M., Rey D., Moreau P. Implications of the polymorphism of HLA-G on its function, regulation, evolution and disease association. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68(3):369–395. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0580-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peng Y., Xiao J., Li W., Li S., Xie B., He J., Liu C. Prognostic and clinicopathological value of human leukocyte antigen G in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.642902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rizzo R., Audrito V., Vacca P., Rossi D., Brusa D., Stignani M., Bortolotti D., D'Arena G., Coscia M., Laurenti L., Forconi F., Gaidano G., Mingari M.C., Moretta L., Malavasi F., Deaglio S. HLA-G is a component of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia escape repertoire to generate immune suppression: impact of the HLA-G 14 base pair (rs66554220) polymorphism. Haematologica. 2014;99(5):888–896. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.095281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rebmann V., da Silva Nardi F., Wagner B., Horn P.A. HLA-G as a tolerogenic molecule in transplantation and pregnancy. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/297073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Emadi E., Akhoundi F., Kalantar S.M., Emadi-Baygi M. Predicting the most deleterious missense nsSNPs of the protein isoforms of the human HLA-G gene and in silico evaluation of their structural and functional consequences. BMC Genet. 2020;21(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12863-020-00890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Poras I., Yaghi L., Martelli-Palomino G., Mendes-Junior C.T., Muniz Y.C., Cagnin N.F., Sgorla de Almeida B., Castelli E.C., Carosella E.D., Donadi E.A., Moreau P. Haplotypes of the HLA-G 3' untranslated region respond to endogenous factors of HLA-G+ and HLA-G- cell lines differentially. PLoS One. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zidi I. Puzzling out the COVID-19: therapy targeting HLA-G and HLA-E. Hum. Immunol. 2020;81(12):697–701. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jasinski-Bergner S., Schmiedel D., Mandelboim O., Seliger B. Role of HLA-G in viral infections. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.826074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laaribi A.B., Bortolotti D., Hannachi N., Mehri A., Hazgui O., Ben Yahia H., Babay W., Belhadj M., Chaouech H., Yacoub S., Letaief A., Ouzari H.I., Boudabous A., Di Luca D., Boukadida J., Rizzo R., Zidi I. Increased levels of soluble HLA-G molecules in Tunisian patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J. Viral Hepat. 2017;24(11):1016–1022. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rehermann B. Pathogenesis of chronic viral hepatitis: differential roles of T cells and NK cells. Nat. Med. 2013;19(7):859–868. doi: 10.1038/nm.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aggarwal R., Sharma M., Mangat N., Suri V., Bhatia T., Kumar P., Minz R. Understanding HLA-G driven journey from HPV infection to cancer cervix: adding missing pieces to the jigsaw puzzle. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020;142 doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2020.103205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amiot L., Vu N., Samson M. Immunomodulatory properties of HLA-G in infectious diseases. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014(1) doi: 10.1155/2014/298569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.E.D. Carosella, N. Rouas-Freiss, D.T.-L. Roux, P. Moreau, J. LeMaoult, Chapter two - hla-g: an immune checkpoint molecule, in: F.W. Alt (Ed.), Advances in Immunology, Academic Press2015, pp. 33-144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Catamo E., Zupin L., Crovella S., Celsi F., Segat L. Non-classical MHC-I human leukocyte antigen (HLA-G) in hepatotropic viral infections and in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum. Immunol. 2014;75(12):1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Własiuk P., Putowski M., Giannopoulos K. PD1/PD1L pathway, HLA-G and T regulatory cells as new markers of immunosuppression in cancers. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2016;70(0):1044–1058. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1220994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article material is referenced in the article.