Abstract

The soluble-to-toxic transformation of intrinsically disordered amyloidogenic proteins such as amyloid beta (Aβ), α-synuclein, mutant Huntingtin Protein (mHTT) and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) among others are associated with disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD) and Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), respectively. The dissolution of mature fibrils and toxic amyloidogenic intermediates, including oligomers, continues to be the pinnacle in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Yet, methods to effectively and quantitatively report on the interconversion between amyloid monomers, oligomers and mature fibrils fall short. Here we describe a simplified method that implements the use of gel electrophoresis to address the transformation between soluble monomeric amyloid proteins and mature amyloid fibrils. The technique implements an optimized but well-known, simple, inexpensive, and quantitative assessment previously used to assess the oligomerization of amyloid monomers and subsequent amyloid fibrils. This method facilitates the screening of small molecules that disintegrate oligomers and fibrils into monomers, dimers, and trimers and/or retain amyloid proteins in their monomeric forms. Most importantly, our optimized method diminishes existing barriers associated with existing (alternative) techniques to evaluate fibril formation and intervention.

Keywords: Amyloid proteins, Soluble-to-toxic conversion, Gel electrophoresis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

A hallmark feature of neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, PD, HD and T2D is the soluble-to-toxic conversion of disease-associated prion-like amyloidogenic proteins such as Aβ, α-synuclein, mHTT, and IAPP, respectively [1–7]. The formation of mature fibrils from their soluble, monomeric counterparts is often the “end-point” of the amyloid-forming (amyloidogenic) trajectory. Fibril formation is essentially deemed irreversible. Mature fibrils, which are rich in β-sheet content, are insoluble and not easily amenable to structural studies.

Amyloid monomers are converted to mature fibrils via a sequential process that first results in the formation of monomers, dimers and trimers to neurotoxic oligomers [7, 8]. Oligomers are generally converted into proto-fibrils prior to the formation of mature fibrils, which is a terminal process as aforementioned. A comparison of the kinetics of monomer consumption relative to the fibril formation is important. A difference in the rate of monomer consumption relative to fibril formation suggests the presence of intermediates, including kinetically-trapped aggregates [7]. Quantifying the loss of monomers is essential for a detailed biophysical understanding of the amyloidogenic trajectory. After all, it is the most experimentally tractable of all species along the amyloid-fibril-forming pathway. It informs us of whether the ambient conditions are biased towards retaining the monomeric conformation or towards fibril formation. It provides a mechanism by which to determine the rate at which monomers are consumed to form fibrils. Measurement of the rate can then be used to fine-tune ambient conditions either to intervene in the fibrillation or to promote it (say, for biophysical studies) [9].

Conversion of mature fibrils to their soluble monomeric counterparts is also indispensable for qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the efficacy by which small molecules may intervene (therapeutically or prophylactically) in amyloid-forming trajectories. Molecules such as tanshinone, brazilin and other aromatics, along with specific carbon nano materials known as carbon quantum dots and graphene quantum dots, have been instrumental in passivating amyloid monomers, remodeling oligomers, and dissolving mature fibrils [10–12]. With respect to small molecule intervention, the ability to revert all non-monomeric intermediates, including mature fibrils, to their soluble monomeric counterpart is key. The ability to localize where along the fibril-forming trajectory that a small molecule intervenes is important for further advancing the candidacy of the said molecule.

Existing techniques to identify the presence of fibrils include dynamic light-scattering (DLS), microscopy (SEM, TEM, etc), x-ray diffraction, solid-state NMR, and EPR among others [13, 14]. While each technique offers specific advantages to the detection of fibrils, they also require equipment that is not easily accessible, is expensive, and/or requires extensive sample preparation. Furthermore, although the use of SDS page has been used previously to assess the oligomerization of amyloid proteins, current methods rely on the use of crosslinking agents such as formaldehyde or glutaraldehyde to form covalent bonds between adjacent subunits. [8, 15–17] This practice is understandable when the aim is to analyze the structure of the protein, without the possibility of dissociation during electrophoresis. However, for the determination of efficacy of small molecule intervention, these additional steps are not necessary.

Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) have been shown to intervene in the soluble-to-toxic transformation of amyloidogenic trajectories [6]. In such studies the introduction of organic-acid CQDs resulted in the inhibition of fibrils of Hen-Egg White Lysozyme (HEWL) even 2 h post-initiation of fibril formation. The mechanistic details of inhibition of aggregation remain to be resolved. However, prior to examining the mode of intervention by CQDs and other small-molecules, it is necessary to develop a method to rapidly screen compounds that can prevent fibril formation in amyloidogenic proteins. Therefore, there is a motivation for the development of a rapid, cost-effective, easily accessible screen method that facilitates monitoring the conversion of a soluble protein into its fibrillar form and to screen molecules for interventional capabilities.

Here, we demonstrate a simplified method to use gel electrophoresis to determine the ability of small molecules to revert mature fibrils to their soluble monomeric counterparts [18]. The advantages of this method over existing techniques are discussed.

Method

Gel Electrophoresis

12% Gels were prepared as described in previous studies [18, 19]. For the running buffer, 1650 μL of water, 2000 μL of 30% acrylamide, 1250 μL of 1.5 M Tris (pH 8.8), 50 μL 10% ammonium persulfate and 2ul TEMED was combined in a 15 mL falcon tube and transferred to the slides. Later, the layering was performed using tertiary butanol. The gels were then left to polymerize for about 20 min. The stacking solution containing 1550 μL of water, 250 μL of 30% acrylamide, 190 μL of 1.5 M Tris (pH 6.8), 15 μL ammonium persulfate and 1.5 μl TEMED in a 15 mL falcon tube was introduced into the gel on top of the running gel. The stacking gel was left for polymerizing for 15 min and then stored at −4 °C until further use in wet Kim wipes covered with the Aluminum foil [20–31].

Preparation of Lysozyme solution

2 mg/mL of Lysozyme solution in freshly made potassium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH =6.3, 3 M Guanidinium Hydrochloride) was prepared in a 5 mL glass vial as previously described [6]. The glass vial containing lysozyme solution was then kept in an incubator-shaker at 550 rpm for 6 h at 58 °C. After 6 h, the contents of the glass vial were turbid which indicated the formation of lysozyme fibril (which was later confirmed using Transmission Electron Microscopy). Dialysis was performed to remove guanidinium hydrochloride (GdnHCl) salt as it compromises the quality of the stained protein bands (salt spread).

Loading of Amyloid Samples onto the Gel

The dialyzed solution was added to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes, which were then transferred to a tabletop ultracentrifuge. Centrifugation was carried out at 12,400 rpm for 15 min.

The supernatant was collected in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and DI water (1 ml) was added to the pellet and mixed well. 30 uL of the solution (including supernatant and pellet) was then transferred in separate 0.5 mL pre-labeled Eppendorf tubes. Later, 10 μL of 4X loading dye was added to 30 uL of supernatant and pellet solution. Monomeric solution of Lysozyme (2 mg/mL) was prepared as a control and 30 uL was mixed with 10 μL of 4X loading dye. The samples were then heated at 95 °C for 5 min and 20 uL of this solution was then loaded into the wells of the gel. The Gel was then run for 85 min at 120 V and 400 A. For the staining-destaining procedure, the gels were removed from the glass slides and rinsed with water. Later, the gels were submerged in Coomasie staining solution overnight. The next day, a destaining procedure was performed to destain the gels using 1:1:0.2 ratio of water: methanol: acetic acid. The destaining was performed three times for 20 min each. After the third destaining wash, the gel was submerged in water and an image was subsequently obtained using the Invitrogen iBright Imaging system.

Data Analysis

The obtained images of the gel using the iBright imaging system were analyzed using the Image J software. The data obtained from Image J were transferred to Origin Pro software and mean and standard deviation values were calculated for each band. The bar graph was plotted against Integrated Density vs Sample name.

This simplified method using gel electrophoresis without crosslinking agents provides advantages over existing techniques, offering a cost-effective and accessible approach for assessing small molecule interventions in amyloidogenic trajectories.

Results

Figure 1 is a TEM image of mature HEWL fibrils. The fibrils are needle-form and well-delineated in nature. The mature fibrils appear to be interspersed with smaller, potentially, proto-fibrillar aggregates. The data are in good agreement with previous literature.

Fig. 1.

TEM image of fibrils

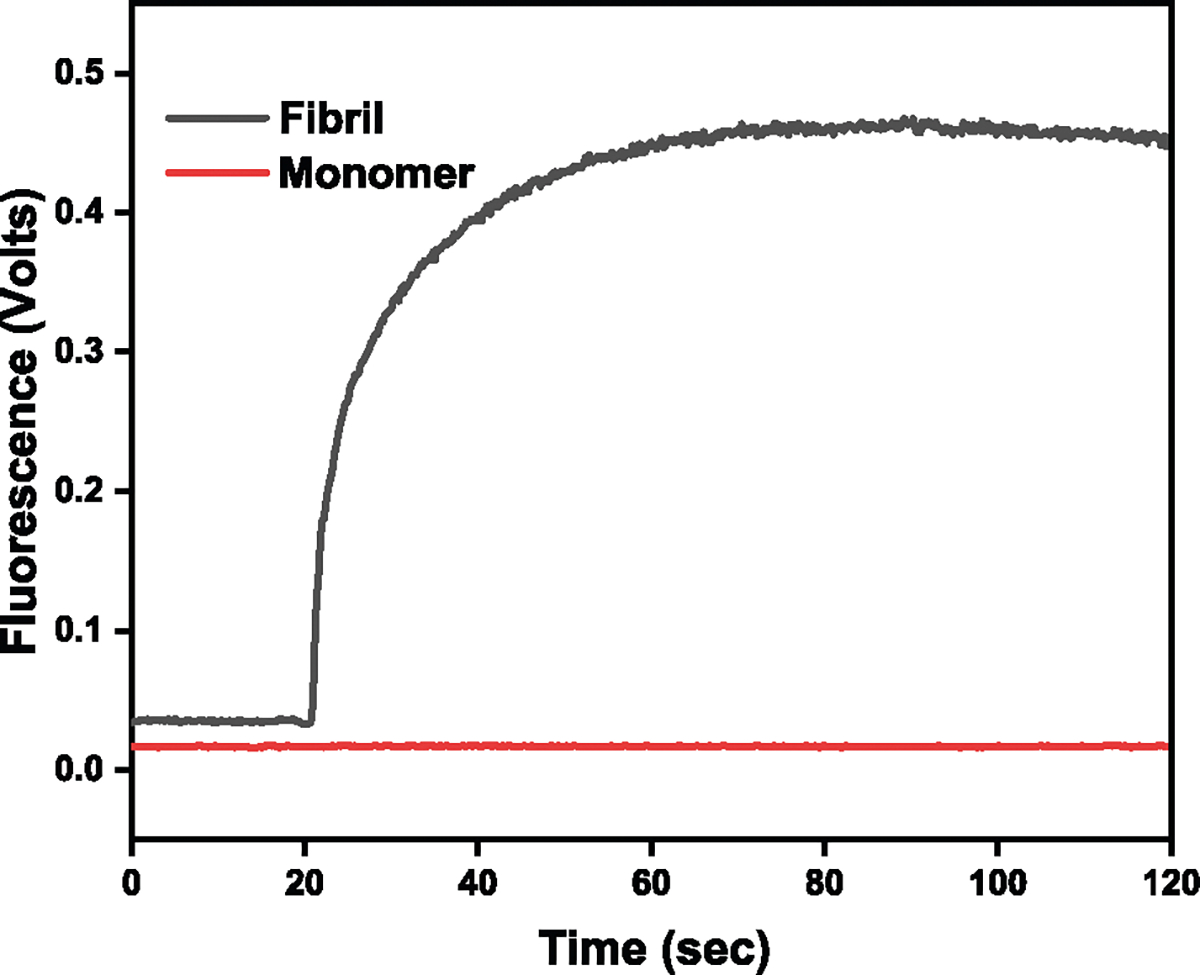

Figure 2 shows the results of the ThT assay in which ThT was added (@20 s) to a solution containing mature fibrils (black curve). There is a sharp and rapid increase in fluorescence upon introduction of the fluorophore, which is indicative of binding to the grooves in the cross-β structure of the fibrils. The plateauing of the curve suggests that all fibril is ThT bound or that there is no remaining free ThT. By contrast, the introduction of ThT to monomeric lysozyme (red curve) did not elicit any increase in fluorescence, as was anticipated.

Fig. 2.

ThT assay confirming the presence of fibrils and monomers. Red: ThT added to a solution of lysozyme monomers. Black: ThT added to a solution containing mature HEWL fibrils

Next, we determined whether gel electrophoresis could be used to qualitatively discriminate between HEWL mature amyloid fibrils and their monomeric counterparts. Figure 3A is an image of a PAGE experiment where HEWL monomers (3A: 1 a and b), the supernatant (3A: 2 a and b) from a centrifuged solution containing mature HEWL fibrils and a resuspended (3A: 3 a and b) HEWL fibril pellet were loaded onto the gel. The locations of the bands correspond to the molecular weight of monomeric HEWL. Inspection of the band intensities reveals that, compared to the sample exclusively containing HEWL monomers (3A: 1 a and b), there is a decrease in the intensity of HEWL monomers in sample (3A: 2 a and b) and a further attrition in its concentration when sampled from the fibril pellet (3A: 3 a and b). The quantitative data are shown in 3B where a diminution in fibril formation is observed compared to untreated control.

Fig. 3.

A PAGE showing protein bands where 1a and b are monomers (starting protein solution; 2mg/mL), 2a and b are supernatant (remaining monomers after fibrillation) and 3a and b are pellets (fibrils). The data is plotted for N = 2 where p < 0.05 was observed. B The bar graphs represent the quantified data from (A)

Figure 3B shows quantified results from the experiment. The diminution in the heights of the bars as a function of fibril-formation suggests that the intensity of the bands on the gel can be used to establish the presence of the presence of monomers and their consumption to form fibrils. Statistical significance was found across samples 1 (HEWL Monomers) and 3 (HEWL Fibrils) and samples 2 (supernatant) and 3 (HEWL Fibrils) indicating that PAGE can be used to quantify the soluble-to-fibril transformation of amyloid-fibril-forming proteins.

We tested whether small molecules and nanocarbon materials can revert HEWL fibrils to their soluble monomeric counterparts. Figure 4A shows the results from an experiment where HEWL fibrils were incubated with DMSO. There is an increase in the concentration of HEWL monomer when mature HEWL fibrils are exposed to DMSO, relative to untreated fibrils. Furthermore, the difference in monomeric HEWL concentrations between DMSO-treated fibrils and untreated fibrils is statistically significant. The data indicate that the DMSO-driven reconversion of mature fibrils to their monomeric counterpart can not only be easily visualized by our method but also quantified. The statistically significant difference in monomeric HEWL concentrations between the monomer control and the DMSO-treated fibrils is also notable. In this scenario, the fraction of monomer released from DMSO-treated mature fibrils reflects the small-molecule driven fibril-to-soluble reconversion efficiency at the concentration of small-molecule used. Here too, a dose-response curve (obtained by varying the v/v of DMSO or the concentration of other small-molecules) can be constructed using this method.

Fig. 4.

A Effect of DMSO on HEWL fibrils. The concentration of monomeric HEWL increases in the presence of DMSO (last bar) compared to the untreated control (middle bar). Monomeric HEWL (control) is also shown for reference (first bar). The data are plotted for N = 2 where p < 0.05 was observed. B Results as in (A) except that HEWL fibrils were exposed to CQDs (CQD1: citric; CQD2:gelatinized carbon)

Figure 4B shows results obtained after exposing HEWL fibrils to carbon quantum dots (CQD1: citric; CQD2:gelatinized carbon). Although there appears to be a CQD-dependent increase in soluble monomers relative to the untreated fibrils, the results were not found to be statistically significant at the CQD dose employed.

Discussion

The soluble-to-toxic conversion of amyloid proteins such as Aβ, α-synuclein, mHTT among others is a critical milestone in the onset and pathogenesis of amyloid-specific neurodegenerative disorders. Efforts to address an understanding of this biophysical transformation are driven by spectroscopic and immunohistochemical tools. Nevertheless, access to instruments such as solid-state NMR, microscopes (TEM, HR-TEM, SEM, AFM), ATR-IR, DLS instruments and biochemical kits precludes routine studies of the process for many laboratories and investigators.

Even if high-resolution microscopes are accessible, extensive sample preparation protocols, analyses times and availability of very specific technical/instrumentation expertise are some of the criteria that remain as hurdles for researchers. Finally, and critically, microscopic techniques are not amenable to quantification and kinetics analyses. As previosuly noted, quantification of the fibrils formed from soluble monomers, and perhaphs more importantly, the reverse process is important for advancing biomedical intervention. The screening of small-molecules that succesfully intervene in vitro in amyloid-forming trajectories are then translated into preclinical models.

Optical methods, such as DLS or fluorescence using ThT or Congo red fluorophores to identify the presence of fibrils, are often confounded by interference from small-molecule fluorescence. Other techniques, such as solid-state NMR, are not amenable to easy use, lack accessibility, and fail to satisfactorily quantify the interconversion between the monomeric amyloid and intermediates and the mature fibril along the trajectory. The experimental sample preparation conditions do not recapitulate solution conditions.

Through several inroads, the method described here reduces barriers toward the study of amyloidogenesis, which has traditionally involved elaborate sample preparation, mounting of “dried” samples, expensive instrumentation and protracted sample analyses times. Even though the technique is chemically and structurally “low-resolution” in nature, it provides a rapid, facile and inexpensive mechanism by which to quantify the loss of monomers (via their conversion to dimers, oligomers, proto-fibrils and fibrils). Importantly, by quantifying the intensity of the bands on the gel, it permits the user to build a kinetic profile of the consumption of monomers, formation of dimers, oligomers and the transformation of the amyloid protein into mature fibrils. From a biomedical perspective, the use of PAGE to establish a quantitative and dose-dependent profile of small-molecule efficiency in dissolving fibrils and oligomeric aggregates to their monomeric counterparts is highly desired.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrate that a readily existing method and easily accessible appartatus can be used to obtain rich biophysical (kinetic) data about amyloid forming trajectories and the interplay between intermediates therein, with increased simplicity and reduced steps than current existing methods. Equally importantly, it can be used to screen small-molecules and also determine, via size analysis, where along the trajectory that the small-molecule intervenes [32–36]. It increases accessibility to undergraduates, graduate students and advanced biomedical researchers in a variety of institutions with a powerful, affordable, and simplified method, to study an important neurodegeneration-associated process.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH/NIGMS) under Award Number 1R16GM145575-01 for supporting this work.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Adamcik J, & Mezzenga R (2012). Study of amyloid fibrils via atomic force microscopy. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 17(6), 369–376. 10.1016/j.cocis.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biancalana M, & Koide S (2010). Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, 1804(7), 1405–1412. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan S, Yau J, Ing C, Liu K, Farber P, Won A, Bhandari V, Kara-Yacoubian N, Seraphim T, Chakrabarti N, Kay L, Yip C, Pomès R, Sharpe S, & Houry W (2016). Mechanism of Amyloidogenesis of a Bacterial AAA+ Chaperone. Structure, 24(7), 1095–1109. 10.1016/j.str.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doig AJ, & Derreumaux P (2015). Inhibition of protein aggregation and amyloid formation by small molecules. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 30, 50–56. 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick AW, & Saibil HR (2019). Cryo-EM of amyloid fibrils and cellular aggregates. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 58, 34–42. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerrero ED, Lopez-Velazquez AM, Ahlawat J, & Narayan M (2021). Carbon Quantum Dots for Treatment of Amyloid Disorders. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 4(3), 2423–2433. 10.1021/acsanm.0c02792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ippel JH, Olofsson A, Schleucher J, Lundgren E, & Wijmenga SS (2002). Probing solvent accessibility of amyloid fibrils by solution NMR spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(13), 8648–8653. 10.1073/pnas.132098999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahamtullah, & Mishra R. (2021). Nicking and fragmentation are responsible for α-lactalbumin amyloid fibril formation at acidic PH and elevated temperature. Protein Science, 30(9 Jun), 1919–1934. 10.1002/pro.4144. Accessed 4 Feb. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jucker M, & Walker LC (2011). Pathogenic protein seeding in alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Annals of Neurology, 70(4), 532–540. 10.1002/ana.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim D, Yoo JM, Hwang H, Lee J, Lee SH, Yun SP, Park MJ, Lee M, Choi S, Kwon SH, Lee S, Kwon SH, Kim S, Park YJ, Kinoshita M, Lee YH, Shin S, Paik SR, Lee SJ, & Ko HS (2018). Graphene quantum dots prevent α-synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s disease. Nature Nanotechnology, 13(9), 812–818. 10.1038/s41565-018-0179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli UK (1970). Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227(5259), 680–685. 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane LC (1978). A simple method for stabilizing protein-sulfhydryl groups during SDS-gel electrophoresis. Analytical Biochemistry, 86(2), 655–664. 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loksztejn A, & Dzwolak W (2009). Noncooperative dimethyl sulfoxide-induced dissection of insulin fibrils: Toward soluble building blocks of amyloid. Biochemistry, 48(22), 4846–4851. 10.1021/bi900394b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoudi M, Akhavan O, Ghavami M, Rezaee F, & Ghiasi SMA (2012). Graphene oxide strongly inhibits amyloid beta fibrillation. Nanoscale, 4(23), 7322 10.1039/c2nr31657a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, & Teplow DB (2003). Amyloid beta -protein (Abeta) assembly: Abeta 40 and Abeta 42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(1), 330–335. 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bitan G, & Teplow DB (2004). Rapid photochemical cross-linkinga new tool for studies of metastable, amyloidogenic protein assemblies. Accounts of Chemical Research, 37(6), 357–364. 10.1021/ar000214l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pujol-Pina R, Vilaprinyó-Pascual S, Mazzucato R, Arcella A, Vilaseca M, Orozco M, & Carulla N (2015). SDS-PAGE analysis of Aβ oligomers is disserving research into Alzheimeŕs disease: appealing for ESI-IM-MS. Scientific Reports, 5(1). 10.1038/srep14809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markwell J (2009). Fundamental laboratory approaches for biochemistry and biotechnology, 2nd edition. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 37(5), 317–318. 10.1002/bmb.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris KL, & Serpell LC (2012). X-ray fibre diffraction studies of amyloid fibrils. Methods in Molecular Biology, 121–135. 10.1007/978-1-61779-551-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pujols J, Peña-Díaz S, Lázaro DF, Peccati F, Pinheiro F, González D, Carija A, Navarro S, Conde-Giménez M, García J, Guardiola S, Giralt E, Salvatella X, Sancho J, Sodupe M, Outeiro TF, Dalfó E, & Ventura S (2018). Small molecule inhibits α-synuclein aggregation, disrupts amyloid fibrils, and prevents degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(41), 10481–10486. 10.1073/pnas.1804198115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sengupta U, Nilson AN, & Kayed R (2016). The role of amyloid-β oligomers in toxicity, propagation, and immunotherapy. EBioMedicine, 6, 42–49. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh P, & Bhat R (2019). Binding of noradrenaline to native and intermediate states during the fibrillation of α-synuclein leads to the formation of stable and structured cytotoxic species. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 10(6), 2741–2755. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreenivasan S, & Narayan M (2019). Learnings from protein folding projected onto amyloid misfolding. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 10(9), 3911–3913. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sreeprasad S, & Narayan M (2019). Nanoscopic portrait of an amyloidogenic pathway visualized through tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 10(8), 3343–3345. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stetefeld J, McKenna SA, & Patel TR (2016). Dynamiclight scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences. Biophysical Reviews, 8(4), 409–427. 10.1007/s12551-016-0218-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streets AM, Sourigues Y, Kopito RR, Melki R, & Quake SR (2013). Simultaneous measurement of amyloid fibril formation by dynamic light scattering and fluorescence reveals complex aggregation kinetics. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e54541 10.1371/journal.pone.0054541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subedi L, & Gaire BP (2021). Tanshinone IIA: A phytochemical as a promising drug candidate for neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacological Research, 169, 105661 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tycko R (2011). Solid-state NMR studies of amyloid fibril structure. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 62(1), 279–299. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vernaglia BA, Huang J, & Clark ED (2004). Guanidine hydrochloride can induce amyloid fibril formation from Hen Egg-white lysozyme. Biomacromolecules, 5(4), 1362–1370. 10.1021/bm0498979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Sun Y, Cao X, Peng G, Javed I, Kakinen A, Davis TP, Lin S, Liu J, Ding F, & Ke PC (2018). Graphene quantum dots against human IAPP aggregation and toxicity in vivo. Nanoscale, 10(42), 19995–20006. 10.1039/c8nr07180b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe-Nakayama T, Sahoo BR, Ramamoorthy A, & Ono K. (2020). High-speed atomic force microscopy reveals the structural dynamics of the amyloid-β and amylin aggregation pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(12), 4287 10.3390/ijms21124287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar J, Varela-Ramirez A, & Narayan M (2024). Development of novel carbon-based biomedical platforms for intervention in xenotoxicant-induced Parkinson’s disease onset. BMEMat, e12072. 10.1002/bmm2.12072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar J, Delgado SA, Sarma H, & Narayan M (2023). Caffeic acid recarbonization: A green chemistry, sustainable carbon nano material platform to intervene in neurodegeneration induced by emerging contaminants. Environmental Research, 237, 116932. 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henriquez G, Ahlawat J, Fairman R, & Narayan M (2022). Citric acid-derived carbon quantum dots attenuate paraquatinduced neuronal compromise in vitro and in vivo. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 13(16), 2399–2409. 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahlawat J, Henriquez G, Varela-Ramirez A, Fairman R, & Narayan M. (2022). Gelatin-derived carbon quantum dots mitigate herbicide-induced neurotoxic effects in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials Advances, 137, 212837. 10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.212837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asil SM, & Narayan M (2024). Molecular interactions between gelatin-derived carbon quantum dots and Apomyoglobin: Implications for carbon nanomaterial frameworks. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 130416. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]