Abstract

Background

This study aims to develop habitat radiomic models to predict overall survival (OS) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), based on the characterization of the intratumoral heterogeneity reflected in 18F-FDG PET/CT images.

Methods

A total of 137 HCC patients from two institutions were retrospectively included. First, intratumoral habitats were achieved by a two-step unsupervised clustering process based on k-means clustering. Second, a total of 4032 radiomic features were extracted based on each habitat, including 2016 PET-based and 2016 CT-based radiomic features. Then, after feature selection, the stacking ensemble learning approach which combined six machine learning classifiers as the first-level learners with Cox proportional hazards regression as the second-level learner, was employed to build multiple radiomic models. Finally, the optimal model was selected based on the calculation of the C-index, and a combined model integrating with a clinical model was also constructed to identify the potentially complementary effect.

Results

Three spatially distinct habitats were identified in the two cohorts. Among a total of 30 stacking ensemble learning models established based on different combinations of 5 types of segmented volumes of interest (VOIs) with 6 types of classifiers, the MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model was selected as the optimal radiomic model with a C-index of 0.702 in the external validation cohort. Furthermore, the combined model integrating the optimal radiomic model with the clinical model achieved an improved C-index of 0.747. Consistently, the combined model outperformed the other models for OS prediction, with a time-dependent AUC of 0.835, 0.828, and 0.800 in the 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year OS, respectively.

Conclusion

18F-FDG PET/CT-based habitat radiomics outperformed traditional radiomics in OS prediction for HCC, with a further improved predictive power by integrating with the clinical model. The optimal combined habitat model was potentially promising in guiding individualized treatment for HCC.

Trial registration

This study was a retrospective study, so it was free from registration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13206-5.

Keywords: 18F-FDG PET/CT, Habitat radiomics, Stacking ensemble learning, HCC, Prognosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is known as the most frequent type of primary liver malignancy, ranging from 75 to 85% of liver cancer occurrences, with comparable incidence and mortality rates [1, 2]. The prognosis of HCC is disheartening primarily attributed to a lack of early diagnosis, and the definite diagnosis frequently occurs in the advanced stage rendering curative interventions unfeasible [3, 4]. To date, the prognosis evaluation for HCC depends heavily on pathological characteristics, such as the histological grade and microscopic vascular invasion (MVI) [3, 5, 6]. However, pathological characteristics can only be definitively diagnosed through histopathological analysis of surgically resected specimens or biopsy, which limits its wide application in clinical practice for HCC. Thus, identifying surrogate prognostic biomarkers for HCC is urgently needed. Currently, the 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT), as a hybrid imaging modality providing both functional and anatomical information, is widely accepted in clinical imaging of oncology, including diagnosis, staging, treatment strategy decision, and therapeutic effect evaluation [1, 7]. Previous reports indicated that some semi-quantitative metabolic parameters obtained from PET/CT imaging, such as maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax), metabolic tumor volume (MTV), and total lesion glycolysis (TLG), held potential as prognostic indicators [8, 9]. Nevertheless, the predictive accuracy of those existing imaging biomarkers for HCC prognosis remains considerably constrained.

Nowadays radiomics is emerging as a novel approach for quantitatively analyzing heterogeneity in medical images, involving the extraction, reduction, and selection of high-throughput and mineable radiomic features, which are subsequently used for classification and/or prognosis prediction [10, 11]. Moreover, previous investigations indicated that employing ensemble machine learning algorithms, which combined the results of one or more base learners to generate predictions into the meta learner, could further enhance the predictive performance of radiomics [12]. The utility of radiomics in aiding prognosis prediction for HCC was also highlighted in several studies. Zhao et al. explored the value of CT-based radiomic nomogram in predicting early recurrence of patients with HCC after liver transplantation, of which the prediction model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.917 in validation cohorts [13]. Kim et al. evaluated the value of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based peritumoral radiomic models in predicting early and late recurrence of HCC after curative resection, and the combined clinicopathologic-radiomic model with the 3-mm border extension exhibited an optimal predictive power with a highest concordance index (C-index) value of 0.716 [14]. Despite the aforementioned advantage of radiomics in quantification of the heterogeneity in medical images, an inherent limitation of traditional radiomics is its implicit assumption that the tumor is homogeneous or heterogeneous but well mixed across the whole tumor [15, 16]. In other words, traditional radiomics is lacking in quantitatively characterization of intratumoral regional variation in heterogeneity captured in medical images [8, 17].

Thus far, habitat radiomics which focuses on subregional radiomics based on intratumoral habitat segmentation across the whole tumor is increasingly conducted for prognosis prediction in various types of tumors, including breast cancer, lung cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [18–20]. Nevertheless, studies about prognostic habitat radiomics based on PET/CT images for HCC were few. Regarding habitat radiomics, utilizing clustering methods to group voxels with similar characteristics within a tumor habitat enables the assessment of intratumoral heterogeneity [21]. As reported, some specific segmented habitats across the whole tumor exhibited heightened aggressiveness, which is largely responsible for the predictive or prognostic performance of the radiomic models with improved accuracy compared to traditional radiomics [22, 23].

In this study, we aim to ascertain the superiority of habitat radiomics based on 18F-FDG PET/CT images over traditional radiomics in prognosis prediction for HCC. It is noteworthy that comprehensive habitat radiomics, involving prognostic radiomic features selected based on five types of volumes of interest (VOIs) and six categories of stacking ensemble machine learning methods, was conducted in the present investigation to select the optimal prognostic habitat model. Additionally, a combined habitat radiomic model integrating with the clinical model was further developed to determine the complementary effect on prognostic power for HCC.

Materials and methods

Study population

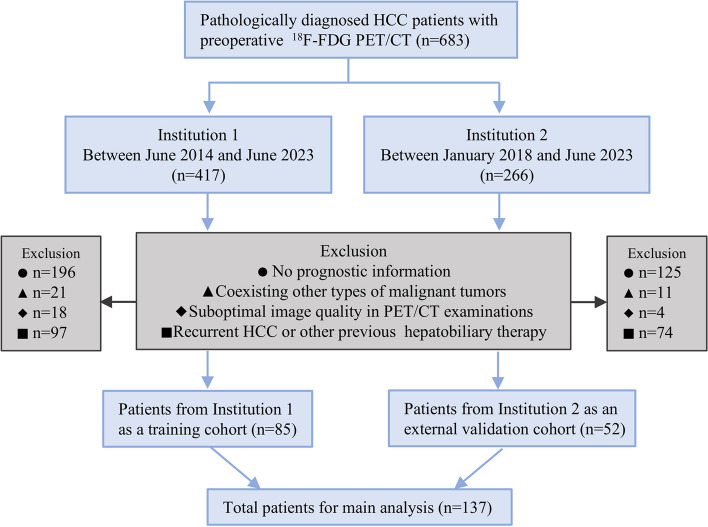

Pathologically diagnosed HCC patients (n = 683) with each one having one set of pre-treatment 18F-FDG PET/CT images within 2 weeks from two institutions, including Tianjin First Central Hospital (Institution 1, n = 417) and Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (Institution 2, n = 266), were retrospectively reviewed in this study. The flowchart of enrollment for eligible HCC patients in this study is depicted in Fig. 1. A total of 137 HCC patients were finally selected for the radiomic analysis, including 85 HCC cases from Institution 1 as a training cohort and 52 HCC cases from Institution 2 as an external validation cohort, respectively. Continuous follow-ups were performed every 3 to 6 months after treatment, and the overall survival (OS) was calculated from the initiation of treatment until death or the last follow-up. This study was approved by the institutional ethics review committee, and all procedures involving humans were implemented following the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart for enrollment of the eligible HCC patients from two institutions which were used as a training cohort and an external validation cohort in the study. Abbreviations: 18F-FDG PET/CT: 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma

18F-FDG PET/CT image acquisition and preprocessing

The detailed protocols for 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging are referred to in the Supplementary Material. For image preprocessing, the PET and CT images were first resampled at an isotropic spatial resolution of 1 × 1 × 1mm3 to ensure voxel spacing standardization. Then, the paired PET and CT images of each HCC patient were rigidly registered using the Elastix software of 3D Slicer (version: 5.2.2). The VOI was manually delineated slice-by-slice based on CT images by two nuclear medicine physicians with over 5 years of experience by using the 3D Slicer software. The mask of VOI was shared by the PET and CT images for further analysis. Then, the traditional metabolic and volumetric parameters (SUVmax, SUVmean, SUVpeak, SUV normalized to lean body mass (SUL), MTV, TLG, and tumor‑to‑mediastinum SUV ratio (TMR)) in PET images were calculated by using the commercial software (PET VCAR; GE Healthcare, USA) on the GE Advantage Workstation 4.6 (AW 4.6).

Intratumoral habitat segmentation

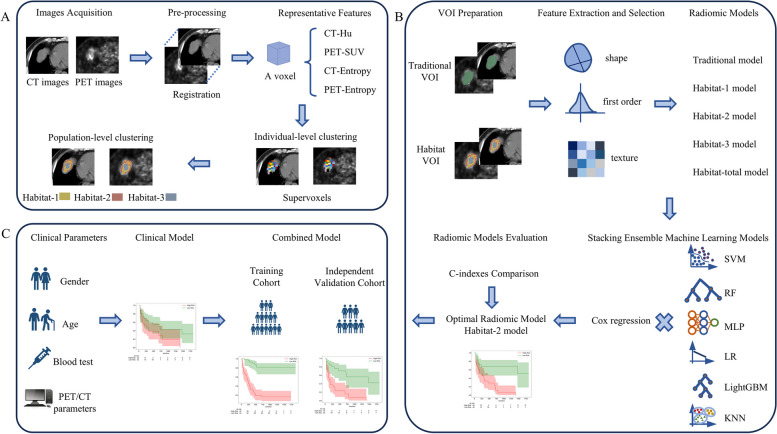

The overall workflow of this study is illustrated in Fig. 2, which consists of intratumoral habitat segmentation, radiomic feature extraction and selection, and multiple stacking ensemble machine learning model construction. A detailed description of these steps is listed below. For intratumoral habitat segmentation, a well-validated two-stage clustering process was employed to partition the whole tumor into distinct subregions (Fig. 2A). Before clustering, a four-dimensional (4D) feature vector for each voxel of every delineated VOI, which was composed of PET SUV, CT intensity value, PET local entropy, and CT local entropy, was first calculated. Specifically, the local entropy for PET and CT were computed within a small neighborhood of 9 × 9 × 9. For individual-level clustering, each VOI was over-segmented into numerous supervoxels with similarity metrics by the k-means clustering algorithm based on the calculation of squared Euclidean distances for the 4D feature vector. The intensity of a supervoxel was determined by the average intensity of all voxels within it. For population-level clustering, all supervoxels in the training cohort were aggregated utilizing the k-means algorithm again, which enabled the merging of similar supervoxels to create distinct habitats. The gap statistic was employed to determine the optimal number for habitat segmentation [15]. The respective centroid of each habitat identified in the training cohort was calculated and used to conduct clustering of the supervoxels in the external validation cohort employing the k-means algorithm, ensuring the generation of consistent habitats between the training cohort and the validation cohort. Finally, two sets of habitats were acquired based on the paired VOIs delineated by two physicians for feature extraction and selection.

Fig. 2.

The workflow of the whole study. A A two-stage clustering of voxels to achieve intratumoral subregion partitioning, including individual-level clustering based on CT value, SUV, and local entropy of CT and PET of each voxel, followed by population-level k-means clustering based on supervoxels. B Construction of a traditional radiomic model and multiple habitat radiomic models combining six types of stacking ensemble machine learning methods based on the whole VOI, each segmented habitat, and an integration of all the habitats, respectively. Among them, the optimal radiomic model was selected based on the calculation of C-index. C A combined model was developed by integrating the selected optimal habitat-2 radiomic model with the clinical model. Abbreviations: CT: computed tomography, PET: positron emission tomography, SUV: standard uptake value, VOI: volume of interest, SVM: support vector machine, RF: random forest, MLP: Multilayer Perceptron, LR: Logistic Regression, LightGBM: Light Gradient Boosting Machine, KNN: k-nearest neighbor, C-index: concordance index

Radiomic features extraction and selection

A total of 4032 radiomic features, including 2016 PET-derived and 2016 CT-derived radiomic features, were extracted based on each segmented habitat and the whole VOI using the Pyradiomics module in Python 3.7.0. For the habitat that was missing in some tumors, corresponding features were filled with zeros. The shape features of each habitat were discarded due to the meaningless of habitat spatiality. The extracted radiomic features are listed in Figure S1. Following feature normalization by using the Z-score to standardize the intensity range, radiomic feature selection was subsequently performed. First, the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was utilized to assess the interobserver repeatability of radiomic features, and features with an ICC value ≥ 0.75 were deemed robust and retained. Second, the features with Pearson’s correlation coefficients > 0.90 were considered potentially highly related, with one of the paired features being excluded. Then, features with p < 0.05 in univariate Cox regression were selected for least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)-Cox regression analysis. The most prognostic radiomic features were filtered based on the optimal lambda value selected through a 10-fold cross-validation.

Stacking ensemble machine learning models construction

Based on the finally selected prognostic radiomic features, various habitat radiomic models and the traditional radiomic model were established. Then, stacking ensemble machine learning models, which combined one of the six base learners, including support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), k-nearest neighbor (KNN), logistic regression (LR), light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), and multilayer perceptron (MLP) as first-level learners, with Cox proportional hazards regression serving as the meta learner at the second level, were developed in the training cohort and validated in the external validation cohort (Fig. 2B). The prognostic performances of these stacking ensemble learning models were assessed by calculation of the C-index. The model with the highest C-index in the external validation cohort was regarded as the optimal model for subsequent analysis. Additionally, by leveraging all clinical features from Table 1, which had been demonstrated in multiple studies to be significantly associated with OS in HCC patients, a clinical model for OS prediction in HCC was also developed by Cox proportional hazards regression. Ultimately, a combined model was constructed by integrating the optimal stacking ensemble model with the clinical model (Fig. 2C).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the training and external validation cohorts

| Characteristics | Training cohort (n = 85) | Validation cohort (n = 52) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.717 | ||

| Female | 13(15.29%) | 10(19.23%) | |

| Male | 72(84.71%) | 42(80.77%) | |

| Age | 54.67 ± 10.82 | 56.46 ± 9.55 | 0.328 |

| BMI | 23.60 (21.85–26.55) | 24.50 (21.73–27.23) | 0.593 |

| AFP | 0.554 | ||

| ≤ 200 ng/mL | 30(35.29%) | 15(28.85%) | |

| > 200 ng/mL | 55(64.71%) | 37(71.15%) | |

| ALT | 0.999 | ||

| ≤ 50 U/L | 59(69.41%) | 36(69.23%) | |

| > 50 U/L | 26(30.59%) | 16(30.77%) | |

| TB | 0.68 | ||

| ≤ 19 μmol/L | 43(50.59%) | 29(55.77%) | |

| > 19 μmol/L | 42(49.41%) | 23(44.23%) | |

| HBV infection | 0.890 | ||

| Never | 53(62.35%) | 31(59.62%) | |

| Current or former | 32(37.65%) | 21(40.38%) | |

| Diameter | 6.70 (3.85–10.55) | 6.90 (3.90–9.13) | 0.425 |

| Location | 0.783 | ||

| right lobe of liver | 44(51.76%) | 30(57.69%) | |

| left lobe of liver | 14(16.47%) | 7(13.46%) | |

| both lobes of liver | 27(31.76%) | 15(28.85%) | |

| TNM | 0.624 | ||

| I | 22(25.88%) | 19(36.54%) | |

| II | 14(16.47%) | 7(13.46%) | |

| III | 19(22.35%) | 10(19.23%) | |

| IV | 30(35.29%) | 16(30.77%) | |

| SUVmax | 8.00 (5.67–11.48) | 7.11 (5.42–9.43) | 0.270 |

| SUVpeak | 6.40 (4.43–8.94) | 5.47 (4.15–7.84) | 0.277 |

| SUVmean | 3.78 (3.12–4.90) | 3.61 (3.06–4.67) | 0.421 |

| MTV | 181.00 (37.14–420.29) | 172.02 (28.39–391.57) | 0.856 |

| TLG | 1401.27 (266.14–6112.07) | 1314.83 (383.54–8796.50) | 0.970 |

| SUL | 6.45 (4.44–8.45) | 5.69 (4.33–7.33) | 0.299 |

| TMR | 3.80 (2.65–5.49) | 3.68 (2.43–5.00) | 0.626 |

A t-test was used for age, a Mann–Whitney U test was used for BMI, diameter, SUVmax, SUVpeak, SUVmean, MTV, TLG, SUL and TMR. A χ2 test was used for the rest

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, AFP Alpha-FetoProtein, ALT alanine transaminase, TB total bilirubin, HBV hepatitis B virus, SUV standardized uptake value, MTV metabolic tumor volume, TLG total lesion glycolysis, SUL SUV normalized to lean body mass, TMR tumor‑to‑mediastinum SUV ratio

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Python 3.7.0 software. Categorical variables were represented as frequency (%) and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using the two independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were represented as median (interquartile range, IQR), and comparisons between two groups were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test. The C-index and the hazard ratio (HR) were used to evaluate the efficacy of the developed models in estimating the OS. Patients were stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk value derived from the predictive model. Kaplan–Meier survival curve analyses with the log-rank test were conducted to compare the survival distributions between groups in the training cohort and external validation cohort, respectively. Additionally, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and corresponding AUCs were employed to evaluate performance at 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS time points.

Results

The clinicopathological characteristics of the included HCC patients

As indicated in Table 1, a total of 137 eligible HCC patients were included in this study, with 85 cases in the training cohort and 52 cases in the external validation cohort, respectively. The median follow-up time was 15 months (interquartile range: 9–28). At the last follow-up, 76 of 137 HCC patients died. No significant difference (P > 0.05) was found in all the analyzed clinicopathological features and the seven PET metabolic parameters, including SUVmax, SUVpeak, SUVmean, MTV, TLG, SUL, and TMR.

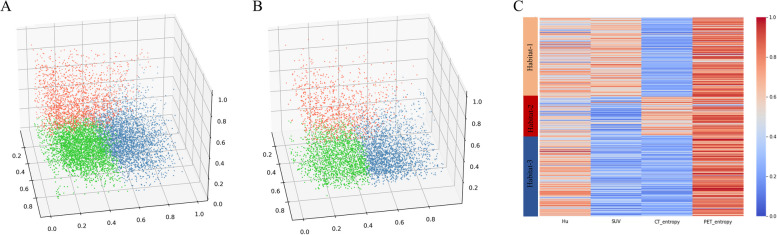

Characterization for the distinct intratumoral habitats

The gap statistic identified 3 as the optimal number for habitat segmentation in a range of 2 to 10 clusters. At population-level clustering, the aggregation of the three categories of supervoxels by k-means clustering was visualized for the training cohort (Fig. 3A). Based on the obtained three centroids of the three aggregations in the training cohort, consistent clustering of supervoxels was performed and visualized for the external validation cohort (Fig. 3B). The distinct imaging phenotypes of the supervoxels aggregated in each habitat were indicated in the form of a heatmap for the whole cohort (Fig. 3C). As shown, habitat-1 was characterized by high CT value, high SUV, and low CT local entropy, representing a metabolically active and homogeneous solid tumor component. Habitat-2 exhibited a relatively slightly lower CT value, low SUV, and high CT local entropy, indicative of a metabolically inactive and heterogeneous tumor component. Habitat-3 displayed a high CT value, low SUV, and low CT local entropy, representing a metabolically inactive and homogeneous solid component.

Fig. 3.

The characteristics of three distinct intratumoral habitats. The visualization for the population-level clustering of three categories of supervoxels in the training cohort (A) and the external validation cohort (B). C The heatmap exhibits distinct imaging phenotypes of all supervoxels in each habitat. As indicated, habitat-1 displayed a high CT value, high SUV, low CT local entropy, and high PET local entropy; Habitat-2 showed a relatively slightly lower CT value, low SUV, high CT local entropy, and high PET local entropy; Habitat-3 exhibited high CT value, low SUV, low CT local entropy, and high PET local entropy

Construction of habitat radiomic models combining stacking ensemble learning

Based on different sources for the extracted radiomic features, including the whole VOI, habitat-1, habitat-2, habitat-3, and an integration of all three habitats-derived radiomic features, five categories of radiomic models were established after feature screening and selection. Figure S2 illustrates the finally selected radiomic features significantly associated with OS for the 5 types of radiomic models. Subsequently, a total of 30 stacking ensemble machine learning models were developed by combining the aforementioned 5 types of radiomic models with 6 categories of stacking ensemble machine learning methods (SVM-Cox, RF-Cox, KNN-Cox, LR-Cox, LightGBM-Cox, MLP-Cox).

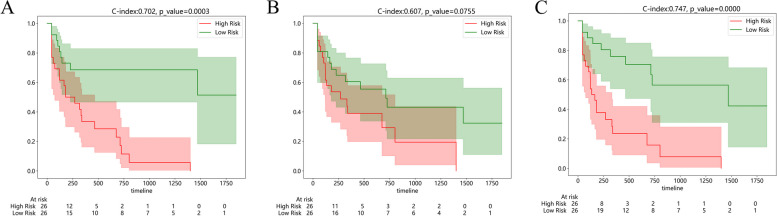

The prognostic performance of the established radiomic models

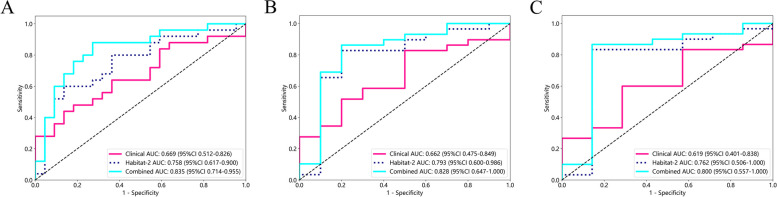

To evaluate the prognostic performance of the established radiomic models, the C-index for each established radiomic model combining various ensemble learning algorithms in the external validation cohort was first calculated (Table 2). Generally, the stacking ensemble machine learning models based on traditional radiomics and habitat-1 radiomics exhibited inferiority over other models in the prediction of prognosis. The MLP-Cox-habitat-2 stacking ensemble learning model, with a C-index of 0.702 in the external validation cohort, was identified as the optimal radiomic model. Additionally, the combined model integrating the optimal habitat radiomic model with the clinical model further promoted the C-index to 0.747. The HCC cases included in the external validation cohort were stratified into a model-predicted high-risk and low-risk group based on the median risk value obtained using the MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model, the clinical model, and the combined model, respectively. Corresponding Kaplan–Meier curves of OS are depicted in Fig. 4. As demonstrated, the P value of the log-rank test for the MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model (Fig. 4A), clinical model (Fig. 4B), and the combined model (Fig. 4C) were 0.0003, 0.0755, and < 0.0001, respectively. Consistently, the time-dependent ROC curves (Fig. 5) confirmed that the combined model outperformed the clinical model and the MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model in OS prediction, with the AUC of 0.835, 0.828, and 0.800 in the 1-year (Fig. 5A), 2-year (Fig. 5B), and 3-year OS (Fig. 5C), respectively.

Table 2.

C-index of radiomic models combining various ensemble learning algorithms in external validation cohort

| Model Name | SVM-Cox | RF-Cox | KNN-Cox | LR-Cox | LightGBM-Cox | MLP-Cox |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat-1 | 0.511 | 0.492 | 0.530 | 0.519 | 0.580 | 0.509 |

| Habitat-2 | 0.678 | 0.622 | 0.645 | 0.687 | 0.564 | 0.702 |

| Habitat-3 | 0.657 | 0.618 | 0.624 | 0.690 | 0.624 | 0.651 |

| Habitat-total | 0.646 | 0.649 | 0.641 | 0.665 | 0.613 | 0.627 |

| Traditional | 0.588 | 0.637 | 0.584 | 0.578 | 0.576 | 0.624 |

Abbreviations: SVM support vector machine, RF random forest, KNN k-nearest neighbor, LR logistic regression, LightGBM light gradient boosting machine, MLP multilayer perceptron

Fig. 4.

Comparison of Kaplan–Meier curves of OS between model-predicted high-risk and low-risk groups in the external validation cohort. HCC patients are stratified into a model-predicted high-risk and low-risk group based on the optimal MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model (A), clinical model (B), and the combined model (C). The value of the C-index and the p-value for the log-rank test were displayed at the top of the figure

Fig. 5.

The time-dependent ROC curves for OS prediction by developed models in the external validation cohort. Comparison of 1-year (A), 2-year (B), and 3-year (C) ROC curves between the habitat-2 model, clinical model, and the combined model. The corresponding AUCs and 95% CIs for each model were shown. Abbreviations: ROC: receiver operating characteristic, AUC: area under the curve, CI: confidence interval

Discussion

In this study, a two-step clustering procedure based on the k-means algorithm was employed to identify distinct habitats within HCC based on 18F-FDG PET/CT images, and multiple habitat radiomic models combining various stacking ensemble learning methods were established to select the optimal model for OS prediction in HCC. As revealed in the results, the MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model with a C-index of 0.702 in the external validation cohort, was accepted as the optimal model. Furthermore, the combined model incorporating the MLP-Cox-habitat-2 model with the clinical model further improved the prognostic performance with a C-index of 0.747, suggesting a complementary role of clinical information to the habitat radiomic model in prognosis prediction for HCC.

HCC is a well-known heterogeneous tumor, with obvious variations in intratumoral heterogeneity in clinical imaging, exhibiting diverse responses and outcomes to therapy [24, 25]. Currently, traditional radiomics primarily quantifies the heterogeneity captured in medical images by calculating a variety of radiomic features, such as histograms or texture features [26, 27]. However, these radiomic features were calculated based on an assumption of uniform heterogeneity throughout the whole tumor, which is not consistent with reality. By contrast, emerging habitat radiomics focuses on quantifying the various heterogeneity in intratumoral subregions. To conduct habitat radiomics, intratumoral habitat partitioning is the prerequisite.

Typically, there are two most commonly used approaches to achieve intratumoral habitat segmentation. One is the Otsu thresholding method, which simplifies the calculation to obtain the optimal threshold for binary image segmentation [28–30]. However, this study was limited by its implicit assumption that the number of segmented habitats is consistent across all tumors based on a fixed binary segmentation on each modal image [28]. The other method for intratumoral subregion partitioning is unsupervised clustering-based habitat generation, which divides all intratumoral voxels into several clusters according to predefined criteria, intending to obtain high intra-cluster similarity and low inter-cluster similarity [31]. Xia et al. built a two-dimensional feature vector based on the CT value and the CT local entropy [2]. Then k-means clustering method was applied to partition the entire tumor into spatially distinct habitats based on these features, offering a novel approach for performing habitat analysis using single-modality imaging. Wu et al. employed a two-step clustering process to perform habitat generation in oropharyngeal carcinoma based on PET/CT images [31]. Initially, each tumor was over-segmented into numerous superpixels at the individual level, based on the PET SUV, CT value, entropy of PET and CT. Next at the population level, consensus clustering was conducted to aggregate all patients’ superpixels, thus yielding habitats. This study proposed a two-step approach to classify tumor habitats, effectively addressing the technical challenges associated with clustering large tumor voxel datasets. Similarly, Fan et al. also explored the two-step clustering method to achieve intratumoral habitat segmentation [22]. Whereas, hierarchical clustering was applied in population-level clustering, distinguishing from Wu et al.’s method, which demonstrated the applicability of various clustering algorithms within the two-step methods. In the present investigation, a two-stage clustering process using a k-means algorithm was used to conduct intratumoral habitat segmentation based on PET/CT images in HCC.

As for population-level clustering, habitat partitioning in the independent external cohort is still a challenge because two independent clustering in the training cohort and the external cohort is not reasonable. Cho et al. initially applied the k-means clustering in the training cohort, and then the center for each cluster was propagated to the validation cohort to ensure consistent clustering across the whole dataset [32]. While, Xu et al. extended the labels of supervoxels in the training cohort to the validation cohort via linear discriminant analysis, ensuring no dissemination of prognostic information from the training cohort [8]. In our study, the clustering of the supervoxels in the external validation cohort was dependent on the centroids obtained from the identified clusters of supervoxels by using the k-means algorithm in the training cohort. Essentially, the clustering strategy based on centroids conforms to the basic principle of the k-means clustering algorithm, representing the benchmarks of the whole dataset. Thus, this clustering strategy based on centroids for an independent external cohort can be generalized in future studies.

Given some intratumoral habitat exhibits more aggressiveness compared to other habitats, specific radiomic features associated with a high-risk intratumoral habitat have the potential to serve as reliable biomarkers for clinical outcomes [33, 34]. As indicated in our study, segmented habitat-2 was characterized by high CT local entropy and high PET local entropy, representing high parenchymal and metabolic heterogeneity. Moreover, the stacking ensemble learning model based on radiomic features from habitat-2 was selected as the optimal model for the prediction of OS in HCC, which suggested that features derived from the habitat characterized by high parenchymal and metabolic heterogeneity could serve as reliable markers of clinical outcomes. Previous studies suggested that tumor heterogeneity may be biologically associated with cellular and genetic heterogeneity, and further investigations were warranted to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms [35, 36]. Habitat radiomics characterized by quantifying the intratumoral variation in heterogeneity across the whole tumor, is expected to further improve the prognostic performance of traditional radiomic models.

Apart from habitat radiomics, another noteworthy innovation in this study is habitat radiomics combining stacking ensemble learning. As a sophisticated algorithm that integrates the predictions of one or more base learners into a meta learner, stacking ensemble learning is capable of enhancing the predictive accuracy in radiomic studies [37, 38]. However, most previous studies primarily focused on evaluating a single machine learning approach. Liang et al. utilized and compared various stacking ensemble machine learning algorithms to analyze the OS outcome of HCC patients who underwent postoperative adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization [39]. The time-dependent ROC analysis showed the Boosting, Bagging, and Stacking model performed well in predicting OS, (AUC: 1-year: 0.878, 0.871, 0.907; 2-year: 0.910, 0.919, 0.941; 3-year: 0.946, 0.930, 0.953). In our current study, the combined model yielded time-dependent AUC of 0.835, 0.828, and 0.800 for the 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year OS predictions, respectively. As described above, the stacking ensemble algorithm exhibited excellent discriminative ability and achieved the optimal prediction performance for the clinical outcomes.

Additionally, the development and integration of clinical model also represented key innovations of this study. By integrating the selected optimal habitat radiomic model with the clinical model into a Cox regression model, the prognostic power of the combined model was further improved, suggesting a complementary effect from clinical information for prognosis prediction in HCC. Nevertheless, few studies investigating the prognosis of HCC has emphasized the additional value of clinical information. Chen et al. developed a combined radiomics-based clinical model for predicting immunoscore in HCC, demonstrating enhancement over the radiomics model (AUC: 0.926 vs. 0.904) [25]. Therefore, the clinical information may serve as a complementary tool to refine model structure and improve the predictive efficiency in HCC research.

This study also has several limitations. First, limited by the small sample size of the two institutions, the prognostic power of the established radiomic models should be interpreted with caution. It is necessary to validate our findings in further large-scale studies from multiple centers with a prospective design. Second, no subgroup radiomics was conducted based on stratification of HCC by clinicopathological characteristics. A comprehensive radiomics or deep learning study is expected to corroborate the conclusion. In the end, further research regarding the underlying molecular mechanism responsible for the prognostic radiomic model is warranted [40, 41].

Conclusion

In our work, three intratumoral habitats with distinct heterogeneity of HCC were identified based on 18F-FDG PET/CT images. The stacking ensemble machine learning model based on the MLP algorithm and radiomic features extracted from the habitat-2 which exhibited high parenchymal and metabolic heterogeneity outperformed those of other habitats or entire tumor. The combined model integrating the optimal stacking ensemble model with the clinical model acquired improved performance in predicting OS in HCC patients, which may hold great potential in guiding individualized treatment in clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the colleagues and staffs at the Department of Molecular Imaging and Nuclear Medicine, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital.

Abbreviations

- 18F-FDG PET/CT

18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- AUC

Area under the curve

- C-index

Concordance index

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICC

Interclass correlation coefficient

- IQR

Interquartile range

- KNN

K-nearest neighbor

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LightGBM

Light gradient boosting machine

- LR

Logistic regression

- MLP

Multilayer perceptron

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTV

Metabolic tumor volume

- MVI

Microscopic vascular invasion

- OS

Overall survival

- RF

Random forest

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD

Standard deviation

- SUVmax

Maximum standard uptake value

- SVM

Support vector machine

- TLG

Total lesion glycolysis

- VOI

Volume of interest

- WMA

World Medical Association

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by QS, RT, and ZL; data collection and analysis were performed by CS, KC and ZW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by CS, and the manuscript was reviewed and edited by XL and WX. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272074 and 82102133), Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-009A), and Construction Project of Cancer Precision Diagnosis and Drug Treatment Technology (ZLJZZDYYWZL11).

Data availability

The raw data is not publicly available due to the privacy protection for all the patients enrolled in the study, which is only available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Hospital (EK20240068), and was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and other relevant ethical guidelines. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Hospital because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chunxiao Sui, Qian Su and Kun Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Wengui Xu, Email: wenguixy@yeah.net.

Xiaofeng Li, Email: xli03@tmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lee SM, Kim HS, Lee S, Lee JW. Emerging role of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for guiding management of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1289–306. 10.3748/wjg.v25.i11.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia W, Chen Y, Zhang R, Yan Z, Zhou X, Zhang B, et al. Radiogenomics of hepatocellular carcinoma: multiregion analysis-based identification of prognostic imaging biomarkers by integrating gene data-a preliminary study. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:035044. 10.1088/1361-6560/aaa609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakabayashi T, Ouhmich F, Gonzalez-Cabrera C, Felli E, Saviano A, Agnus V, et al. Radiomics in hepatocellular carcinoma: a quantitative review. Hepatol Int. 2019;13:546–59. 10.1007/s12072-019-09973-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai Q, Spoletini G, Mennini G, Laureiro ZL, Tsilimigras DI, Pawlik TM, et al. Prognostic role of artificial intelligence among patients with hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6679–88. 10.3748/wjg.v26.i42.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi H, Duan Y, Shi J, Zhang W, Liu W, Shen B, et al. Role of preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma based on the texture of FDG PET image: a comparison of quantitative metabolic parameters and MRI. Front Physiol. 2022;13:928969. 10.3389/fphys.2022.928969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu X, Zhang HL, Liu QP, Sun SW, Zhang J, Zhu FP, et al. Radiomic analysis of contrast-enhanced CT predicts microvascular invasion and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2019;70:1133–44. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho KJ, Choi NK, Shin MH, Chong AR. Clinical usefulness of FDG-PET in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2017;21:194–8. 10.14701/ahbps.2017.21.4.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu H, Lv W, Feng H, Du D, Yuan Q, Wang Q, et al. Subregional radiomics analysis of PET/CT imaging with intratumor partitioning: application to prognosis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020;22:1414–26. 10.1007/s11307-019-01439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han JH, Kim DG, Na GH, Kim EY, Lee SH, Hong TH, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factors on recurrence after curative resections for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17132–40. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannella R, Santinha J, Beaufrere A, Ronot M, Sartoris R, Cauchy F, et al. Performances and variability of CT radiomics for the prediction of microvascular invasion and survival in patients with HCC: a matter of chance or standardisation? Eur Radiol. 2023;33:7618–28. 10.1007/s00330-023-09852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napel S, Mu W, Jardim-Perassi BV, Aerts H, Gillies RJ. Quantitative imaging of cancer in the postgenomic era: Radio(geno)mics, deep learning, and habitats. Cancer. 2018;124:4633–49. 10.1002/cncr.31630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao S, Wang J, Jin C, Zhang X, Xue C, Zhou R, et al. Stacking ensemble learning-based [(18)F]FDG PET radiomics for outcome prediction in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:1603–9. 10.2967/jnumed.122.265244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J-W, Shu X, Chen X-X, Liu J-X, Liu M-Q, Ye J, et al. Prediction of early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation based on computed tomography radiomics nomogram. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:543–50. 10.1016/j.hbpd.2022.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Shin J, Kim DY, Choi GH, Kim MJ, Choi JY. Radiomics on gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of postoperative early and late recurrence of single hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3847–55. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu J, Gensheimer MF, Dong X, Rubin DL, Napel S, Diehn M, et al. Robust intratumor partitioning to identify high-risk subregions in lung cancer: a pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95:1504–12. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen H, Chen L, Liu K, Zhao K, Li J, Yu L, et al. A subregion-based positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) radiomics model for the classification of non-small cell lung cancer histopathological subtypes. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021;11:2918–32. 10.21037/qims-20-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waqar M, Van Houdt PJ, Hessen E, Li KL, Zhu X, Jackson A, et al. Visualising spatial heterogeneity in glioblastoma using imaging habitats. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1037896. 10.3389/fonc.2022.1037896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J, Gensheimer MF, Zhang N, Guo M, Liang R, Zhang C, et al. Tumor subregion evolution-based imaging features to assess early response and predict prognosis in oropharyngeal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:327–36. 10.2967/jnumed.119.230037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beaumont J, Acosta O, Devillers A, Palard-Novello X, Chajon E, de Crevoisier R, et al. Voxel-based identification of local recurrence sub-regions from pre-treatment PET/CT for locally advanced head and neck cancers. EJNMMI Res. 2019;9:90. 10.1186/s13550-019-0556-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillies RJ, Balagurunathan Y. Perfusion MR imaging of breast cancer: insights using “Habitat Imaging.” Radiology. 2018;288:36–7. 10.1148/radiol.2018180271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DH, Park JE, Kim N, Park SY, Kim YH, Cho YH, et al. Tumor habitat analysis by magnetic resonance imaging distinguishes tumor progression from radiation necrosis in brain metastases after stereotactic radiosurgery. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:497–507. 10.1007/s00330-021-08204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan Y, Dong Y, Yang H, Chen H, Yu Y, Wang X, et al. Subregional radiomics analysis for the detection of the EGFR mutation on thoracic spinal metastases from lung cancer. Phys Med Biol. 2021;66. 10.1088/1361-6560/ac2ea7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wu J, Gong G, Cui Y, Li R. Intratumor partitioning and texture analysis of dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI identifies relevant tumor subregions to predict pathological response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44:1107–15. 10.1002/jmri.25279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei J, Jiang H, Gu D, Niu M, Fu F, Han Y, et al. Radiomics in liver diseases: current progress and future opportunities. Liver Int. 2020;40:2050–63. 10.1111/liv.14555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S, Feng S, Wei J, Liu F, Li B, Li X, et al. Pretreatment prediction of immunoscore in hepatocellular cancer: a radiomics-based clinical model based on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI imaging. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:4177–87. 10.1007/s00330-018-5986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Zhang Y, Fang Q, Zhang X, Hou P, Wu H, et al. Radiomics analysis of [(18)F]FDG PET/CT for microvascular invasion and prognosis prediction in very-early- and early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2599–614. 10.1007/s00259-020-05119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Luo S, Jin G, Fu R, Yu Z, Zhang J. Preoperative clinical-radiomics nomogram for microvascular invasion prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma using [Formula: see text]F-FDG PET/CT. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22:70. 10.1186/s12880-022-00796-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Liu K, Zhao X, Shen H, Zhao K, Zhu W. Habitat imaging-based (18)F-FDG PET/CT radiomics for the preoperative discrimination of non-small cell lung cancer and Benign inflammatory diseases. Front Oncol. 2021;11:759897. 10.3389/fonc.2021.759897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailo M, Pecco N, Callea M, Scifo P, Gagliardi F, Presotto L, et al. Decoding the heterogeneity of malignant gliomas by PET and MRI for spatial habitat analysis of hypoxia, perfusion, and diffusion imaging: a preliminary study. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:885291. 10.3389/fnins.2022.885291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Xu C, Grzegorzek M, Sun H. Habitat radiomics analysis of pet/ct imaging in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: Application to Ki-67 status and progression-free survival. Front Physiol. 2022;13:948767. 10.3389/fphys.2022.948767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J, Cao G, Sun X, Lee J, Rubin DL, Napel S, et al. Intratumoral spatial heterogeneity at perfusion MR imaging predicts recurrence-free survival in locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Radiology. 2018;288:26–35. 10.1148/radiol.2018172462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho HH, Kim H, Nam SY, Lee JE, Han BK, Ko EY, et al. Measurement of perfusion heterogeneity within tumor habitats on magnetic resonance imaging and its association with prognosis in breast cancer patients. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:1858. 10.3390/cancers14081858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang M, Kan Y, Dong D, Yu T, Zhao N, Jiang W, et al. Multi-habitat based radiomics for the prediction of treatment response to concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy in locally advanced cervical cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:563. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaheen A, Bukhari ST, Nadeem M, Burigat S, Bagci U, Mohy-Ud-Din H. Overall survival prediction of glioma patients with multiregional radiomics. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:911065. 10.3389/fnins.2022.911065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan J, Zhao Y, Chen Y, Wang W, Duan W, Wang L, et al. Deep learning features from diffusion tensor imaging improve glioma stratification and identify risk groups with distinct molecular pathway activities. EBioMedicine. 2021;72:103583. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Zhao Y, Duan J, Gu J, Liu Z, Zhang H, et al. MRI and RNA-seq fusion for prediction of pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Displays. 2024;83. 10.1016/j.displa.2024.102698.

- 37.Fu Y, Wang X, Yi X, Guan X, Chen C, Han Z, et al. Ensemble machine learning model incorporating radiomics and body composition for predicting intraoperative HDI in PPGL. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109:351–60. 10.1210/clinem/dgad543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong J, Wang T, Wang Z, Chu X, Hu T, Li M, et al. Enhancing brain metastasis prediction in non-small cell lung cancer: a deep learning-based segmentation and CT radiomics-based ensemble learning model. Cancer Imaging. 2024;24:1. 10.1186/s40644-023-00623-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang Y, Wang Z, Peng Y, Dai Z, Lai C, Qiu Y, et al. Development of ensemble learning models for prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients underwent postoperative adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1169102. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1169102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Q, Chen Y, Liang C, Zhao Y, Lv X, Zou Y, et al. Biologic pathways underlying prognostic radiomics phenotypes from paired MRI and RNA sequencing in glioblastoma. Radiology. 2021;301:654–63. 10.1148/radiol.2021203281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y, Liu G, Sun Q, Zhai G, Wu G, Li ZC. Validation of CT radiomics for prediction of distant metastasis after surgical resection in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: exploring the underlying signaling pathways. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:5032–40. 10.1007/s00330-020-07590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data is not publicly available due to the privacy protection for all the patients enrolled in the study, which is only available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests.