Abstract

We present a new marker that confers both resistance to pyrimethamine and green fluorescent protein-based fluorescence on the malarial parasite Plasmodium berghei. A single copy of the cassette integrated into the genome is sufficient to direct fluorescence in parasites throughout the life cycle, in both its mosquito and vertebrate hosts. Erythrocyte stages of the parasite that express the marker can be sorted from control parasites by flow cytometry. Pyrimethamine pressure is not necessary for maintaining the cassette in transformed parasites during their sporogonic cycle in mosquitoes, including when it is borne by a plasmid. This tool should thus prove useful in molecular studies of P. berghei, both for generating parasite variants and monitoring their behavior.

Stable genetic transformation has been achieved in three species of Plasmodium, the agent of malaria: Plasmodium falciparum, a human pathogen (16); Plasmodium berghei, which infects rodents (12); and Plasmodium knowlesi, which infects primates (11). One of the main applications of this new technology is the analysis of protein function via gene targeting. In Plasmodium, targeting constructs integrate exclusively into the haploid genome by homologous recombination, which greatly facilitates gene targeting procedures (6). The P. berghei rodent system offers the advantage that targeted clones (erythrocytic stages of the parasite) can be efficiently selected in a limited period of time, generating clones that retain the ability to undergo gametocytogenesis and the complete cycle in mosquitoes. It also permits in vivo analysis of liver infection by the sporozoite stage of the parasite. The model is, however, still limited by the paucity of genetic tools. So far, only one activity, resistance to pyrimethamine, can be used to select transformants.

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria has become a marker of choice for studies on gene expression and protein localization in living cells (see reference 7 for a review). Among the GFP variants that have spectral characteristics suited to conventional fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter sets (i.e., with a shift in excitation maximal from 395 nm to 480 to 500 nm) (2, 3, 5), GFPmut2 displays an ∼20-fold more intense fluorescence than that of wild-type (WT) GFP when excited at 488 nm and is more soluble (2). This variant has recently been used as a reporter in P. falciparum transformation, by expressing it from the untranslated regions (UTR) of the P. falciparum hrp3 and hrp2 genes (14). Erythrocyte (RBC) stages of the parasite transiently transformed with the construct were readily detectable by standard FITC microscopy.

Construction of the PyrFlu selectable marker and of PyrFlu-expressing P. berghei lines.

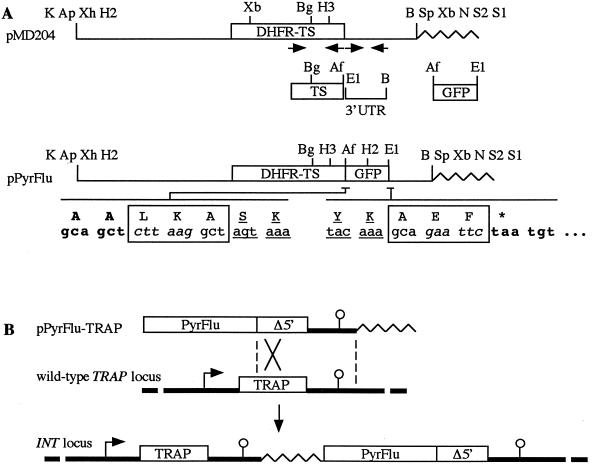

We adapted GFPmut2 to the stable transformation of P. berghei. We constructed a cassette, named PyrFlu, which confers pyrimethamine resistance and directs a fluorescence signal via a single protein fusion. The pyrimethamine resistance cassette originally used for transforming RBC stages of P. berghei (12) consisted of a P. berghei mutant DHFR-TS gene expressed by 2.5 and 1 kb of its own 5′ and 3′ UTR, respectively. Here, we constructed by amplification cloning a derivative of the original cassette that contains a DHFR-TS–GFPmut2 fusion gene under the control of 2.5 kb of 5′- and 0.5 kb of 3′-UTR of P. berghei DHFR-TS (Fig. 1A). The encoded fusion protein consists of all residues of each partner except the starting Met of GFPmut2, contains a Leu-Lys-Ala tripeptide linking TS and GFPmut2, and ends with an Ala-Glu-Phe tripeptide.

FIG. 1.

(A) Construction of the PyrFlu marker. The marker was constructed by amplification and cloning of three DNA fragments. The proximal fragment corresponding to the 3′ end of the P. berghei pyrimethamine resistance DHFR-TS gene was amplified from plasmid pMD204 (12) with primers Oneca1ter (sense; 5′-GGTGCTGAATATACAGATATGCATGAT-3′) and Ohar1 (antisense; 5′-CGCTTAAGAGCTGCCATATCCATATTTATTTTATCGT-3′ [with the AflII site underlined]). The distal fragment corresponding to ∼0.5 kb of the 3′ UTR of DHFR-TS was amplified from the same plasmid with primers Ohar4 (sense; 5′-GCGGAATTCTAATGTTCGTTTTTCTTATTTATATAT-3′ [with the EcoRI site underlined]) and ONeca4 (antisense; 5′-GCGGGTACCGGATCCATCGAAATTGAAGGAAAAAACATCA-3′ [with the BamHI site underlined]). The central fragment corresponding to the GFPmut2 coding sequence was amplified from plasmid pHRPGFPM2 (14) with primers Ohar2 (sense; 5′-GCGCTTAAGGCTAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTCACT-3′ [with the AflII site underlined]) and Ohar3 (antisense; 5′-GCGGAATTCTGCTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGT-3′ [with the EcoRI site underlined]). The three fragments were then fused via the AflII and EcoRI sites, and the internal BglII-BamHI fragment of the reassembled locus was used to replace its counterpart in plasmid pMD204, yielding plasmid pPyrFlu. The nucleotide and amino acid (single letter code) sequences immediately flanking the GFPmut2 sequence are shown. Sequences in bold originate from DHFR-TS; boxed sequences constitute linker sequences, each containing a restriction site (italicized); and underlined sequences originate from GFPmut2. Wavy lines indicate the multicopy plasmid pBSKS (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Ap, ApaI; Af, AflII; B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; E1, EcoRI; H2, HincII; H3, HindIII; K, KpnI; N, NotI; S1, SacI; S2, SacII; Sp, SpeI; Xb, XbaI; Xh, XhoI. (B) Targeting the PyrFlu marker at the TRAP locus in P. berghei. Plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP was obtained by cloning ∼3 kb of TRAP targeting sequence as a BamHI-NotI fragment into plasmid pPyrFlu. The TRAP targeting sequence consists of the 3′ part of TRAP (Δ5′) and ∼1.5 kb of its 3′ UTR (thick line). Prior to transformation into WT P. berghei, plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP was linearized at the unique SpeI site located in the targeting sequence 250 bp from its 5′ end. Homologous integration of plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP at the TRAP locus creates the INT locus, in which the first TRAP copy is full-length and expressed. Also shown are plasmid pBSKS (wavy lines), TRAP promoter (arrows), and 3′ sequences necessary for the normal expression of TRAP (circles).

To test the functionality of the PyrFlu cassette integrated into the P. berghei genome, we constructed insertion plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP, which contains the cassette followed by ∼3 kb of TRAP targeting sequence (Fig. 1B). The TRAP gene encodes a protein that is targeted to the sporozoite surface and essential for sporozoite infectivity (9). Since the TRAP targeting sequence starts downstream from the start codon of the gene and ends ∼1.5 kb downstream from the stop codon (8), homologous integration of the plasmid at the TRAP locus should create a recombinant locus that contains a full-length and expressed copy of TRAP. Thus, recombinant parasites should have a normal life cycle.

In P. berghei, transformation with a targeting plasmid in an uncut form leads to the autonomous replication of the plasmid as an episome, whereas transformation with an insertion plasmid cut in the region of homology leads to its integration at the cognate locus (6, 9, 12). We transformed WT P. berghei merozoites independently with uncut plasmid pPyrFlu and with plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP linearized in the TRAP targeting sequence. Transformed parasites were then selected in rats by using pyrimethamine, as previously described (6, 15). Southern blot hybridization of genomic DNA of resistant parasites confirmed the presence of plasmid pPyrFlu as a nonintegrated element in parasites transformed with the corresponding circular DNA and of plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP integrated into TRAP in parasites transformed with the corresponding linear DNA (see below). This indicated that the pyrimethamine resistance conferred by the mutant DHFR-TS gene was not affected by fused GFPmut2. Parasite clones bearing episomal pPyrFlu or integrated pPyrFlu-TRAP were then obtained from initial populations by limiting dilution, and one representative of each, called EPI and INT, respectively, was selected for further analysis. After selection, RBC stages of the EPI clone were allowed to replicate in the presence of drug pressure (i.e., 20 mg of pyrimethamine per kg), whereas RBC stages of the INT clone were left untreated. Both types of parasites were found to replicate at similar rates in rat RBC (i.e., with a 5- to 10-fold increase in parasitemia per day).

Fluorescence of RBC stages of recombinant parasites.

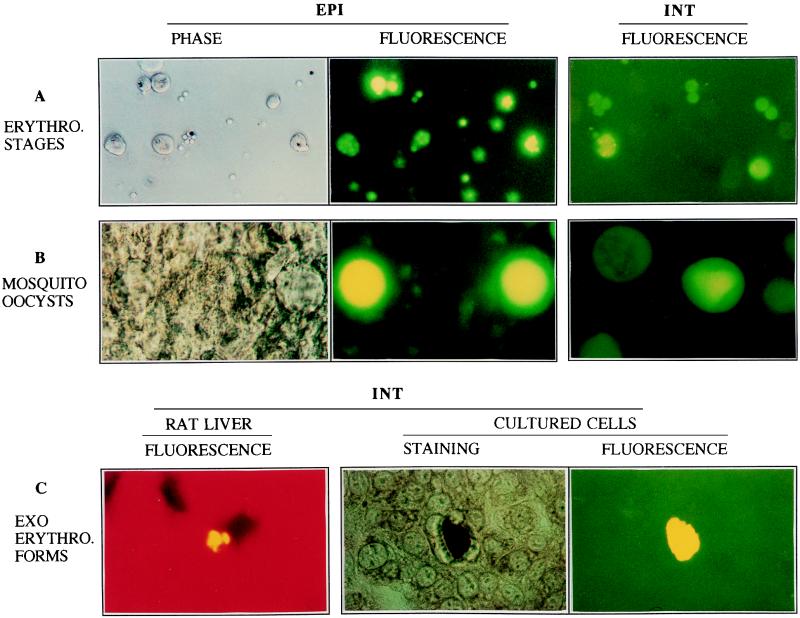

Clear signals were detected by fluorescence microscopy with a standard FITC filter setting in RBC infected with either EPI or INT parasites (Fig. 2A). Fluorescence displayed by EPI parasites was stronger than that displayed by INT parasites, which probably reflects a gene dosage effect due to the high number of copies of DHFR-TS-based episomes per P. berghei parasite (up to 20 per nucleus [13]) versus the single copy of the cassette integrated in INT parasites. With both populations, however, the proportion of fluorescent RBC was always found to match the parasitemia determined by Giemsa staining of blood smears. This indicated that all RBC stages of the parasites expressed a functional fusion protein. This confirms earlier reports of constitutive transcription of the P. berghei DHFR-TS gene during the asexual development of the parasite in RBC (13).

FIG. 2.

Fluorescence of INT and EPI parasites at different stages of the life cycle. (A) RBC stages of the parasites. Blood was collected from the tails of infected rats, and cells were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline and examined by phase microscopy (left panel) or fluorescence microscopy with FITC filter settings. Note the multinucleated intracellular forms of the parasite and extracellular merozoites. Magnification, ×32. (B) Oocysts present in mosquito midguts at day 7 p.f. Midguts were dissected out from infected mosquitoes in RPMI medium and examined by phase or fluorescence microscopy. Magnification, ×32. (C) EEF of the parasites developing in vivo in the rat liver or in vitro in HepG2 cultured cells. For in vivo studies, young Sprague-Dawley rats (∼60 g) were injected with 25,000 salivary gland sporozoites collected at day 18 p.f. Rats were then sacrificed 42 h later, their livers were removed, and frozen sections were prepared as described previously (1). For in vitro studies, HepG2 cells were incubated with 25,000 salivary gland sporozoites collected at day 18 p.f. for 2 h, extracellular sporozoites were washed, and cells were incubated at 37°C for ∼42 h (4). Cells were then fixed with methanol, stained with monoclonal antibody 2E6 directed against parasite heat shock protein 70 (10), and treated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, or they were examined by FITC fluorescence. Magnification, ×32.

The blood of rats infected with various parasite clones was then analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 3A, RBC infected with INT parasites (bearing a single copy of the cassette [Fig. 1B]) were easily detectable and were measured on average as being at least 10-fold more fluorescent than RBC infected with WT parasites (similar levels of fluorescence were produced by four independent INT clones). As a control, RBC infected with insertion control (INCO) parasites were analyzed. INCO parasites were obtained after homologous integration of an insertion plasmid, which differs from pPyrFlu-TRAP only by the absence of GFPmut2 in the resistance cassette, into the TRAP gene. These parasites did not display any fluorescence above the background level (Fig. 3A). Brighter fluorescence was detected when INT parasite-infected blood was examined shortly after tail bleeding of the rat (Fig. 3A; compare the fourth and second panels, i.e., INT parasites examined 30 min and 2 h after tail bleeding, respectively). Larger and more-fluorescent cells, i.e., schizonts, tended to disappear with time, reflecting the rupture of infected RBC and the release of individual merozoites (shown as extracellular fluorescent dots in Fig. 2A). Therefore, a single integrated copy of the PyrFlu cassette is sufficient for easy detection of tagged RBC stages of the parasite by fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

FIG. 3.

(A) FACS analysis of blood infected with various parasite clones. Infected blood was collected by tail bleeding, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline to the concentration of 106 cells/ml, and analyzed 2 h (WT, INT, and INCO) or 30 min (INT-30 min) after bleeding with a Becton Dickinson FACScan machine equipped with an Argon laser tuned at 488 nm. The log fluorescence intensity of 10,000 cells (sorting events) was plotted against the forward scatter. (B) Schematic representation of the WT and INT recombinant loci. The predicted sizes of the fragments liberated upon genomic digestion with the restriction enzyme BamHI are indicated (in kilobases). Also shown are the TRAP 5′ and 3′ UTR (thick lines) and plasmid pBSKS (thin lines). (C) Sorting of PyrFlu-expressing RBC stages of the parasite. The blood of a rat (parasitemia of 1%) infected with a 1:1 ratio of WT and INT parasites (MIX) was sorted with a Coulter Epics Elite sorter (Coulter, Miami, Fla.). Gates on fluorescent (F) and nonfluorescent (NF) cells were set in a plot of fluorescence versus the forward scatter. Fluorescent and nonfluorescent cells were collected separately from the sample until the sort count of fluorescent cells was ∼3,000 (and ∼650,000 nonfluorescent cells had been sorted). Cells were injected into two rats, and the parasite DNA was collected from each rat (at 1% parasitemia) and analyzed by Southern hybridization with a probe corresponding to the entire coding sequence of TRAP. The BamHI digestion differentiates WT from INT parasites that appear as one band of 9 kb or two bands of 16 and 4 kb, respectively.

We next determined whether INT parasites could be selected by FACS based on their fluorescent signal. For this, fluorescent and nonfluorescent RBC were sorted from the blood of rats infected with both WT and INT parasites, and sorted cells were injected intravenously into rats. Sorted parasites had replication rates similar to those of nonsorted WT parasites. After parasite expansion in rats, their genomic DNA was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with a TRAP probe (Fig. 3B) to differentiate WT parasites from INT parasites. One example of selection is presented in the results shown in Fig. 3C, for which cells were sorted from the blood of a rat infected with a 1:1 ratio of WT and INT parasites. By Southern hybridization, INT parasites appear as two bands of 4 and 16 kb, indicating the presence of a single copy of plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP at the TRAP locus, while the WT appears as a single band of 9 kb. As shown, WT parasites were not detected in the fluorescent population and INT parasites were not detected in the nonfluorescent population. We also sorted fluorescent INT parasites to apparent homogeneity (by Southern hybridization) from a 100-fold excess of nonfluorescent INCO parasites (data not shown). We conclude that the presence of a single copy of the PyrFlu cassette is sufficient for efficient parasite selection based on fluorescence.

Fluorescence of sporogonic stages of recombinant parasites.

We then examined the sporogonic cycle of PyrFlu-expressing parasites in Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes fed on infected hamsters (which induce higher infection rates in mosquitoes than rats). Oocysts from INT or EPI clones examined at day 7 postfeeding (p.f.) were brightly fluorescent (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the level of fluorescence emitted by individual EPI or INT sporozoites was low, and isolated sporozoites released in mosquito tissues could not be detected based on fluorescence. This may reflect a decrease in the level of expression of the DHFR-TS gene at this stage of the parasite, since merozoites that also contain a single copy of the genome are nonetheless brightly fluorescent.

As shown in Table 1, the percentage of infected mosquitoes at day 7 p.f. and the number of sporozoites in the midgut and salivary glands per infected mosquito at day 18 p.f. were similar in mosquitoes infected with the WT, INT, or EPI parasite. Sporozoites from each clone displayed similar infectivity to rats, as indicated by the similar prepatent periods of infection. Also, salivary gland sporozoites from each parasite clone invaded cultured HepG2 cells with similar efficiency. Therefore, the expression of the PyrFlu cassette does not significantly alter parasite infectivity.

TABLE 1.

Life cycles of WT P. berghei and clones

| Para-site | % of infected mosqui-toesa | Mean no. of sporozoites per infected mosquitob in:

|

No. of days to infection in rat liverc | HepG2 cell invasiond | % of fluo-rescent and infected RBCe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG | SG | |||||

| WT | 80 | 24,000 | 20,000 | 3.1 | + | |

| EPI | 75 | 22,500 | 18,000 | 3.4 | + | 78 |

| INT | 90 | 25,500 | 17,000 | 3.2 | + | 100 |

Percentage of mosquitoes with oocysts present at day 7 p.f., after ∼100 mosquitoes fed on an infected hamster for two consecutive days.

Day 18 p.f. MG, midgut; SG, salivary glands.

Number of days between injection of 15,000 salivary gland sporozoites in rats and detection of RBC stages of the parasite. Data are means from four experiments.

EEF present 48 h after infection with 25,000 salivary gland sporozoites.

Percentage of infected RBC fluorescent after one life cycle (mean of four experiments).

Although the fluorescence displayed by both EPI and INT sporozoites was too weak to allow parasite detection in mosquito tissues or during the initial 2 h of contact with cultured cells, the exoerythrocytic forms (EEF) of INT parasites that developed normally in ∼40 h in the cytoplasm of cultured cells were brightly fluorescent (Fig. 2C). To test whether EEF could also be detected in vivo, rats were injected with 25,000 salivary gland INT sporozoites and sacrificed 40 h later, and thin frozen sections of their livers were prepared. Analysis of the sections showed brightly fluorescent EEF (Fig. 2C).

We next determined the proportion of RBC stages of the parasites that still fluoresced after one passage through mosquitoes, which took place in the absence of pyrimethamine selection. For this experiment, 15,000 salivary gland sporozoites of the EPI or INT clones collected at day 18 p.f. were injected into rats. The blood of infected rats (at 1 to 2% parasitemia) was analyzed by FACS to determine the proportion of fluorescent RBC and stained with Giemsa to determine the proportion of infected RBC. As expected, all INT RBC stages were fluorescent. Southern blot analysis of the total parasite genomic DNA revealed a pattern identical to that of the INT parasites of the previous cycle, confirming the stability of the genomic structure generated by plasmid integration. Surprisingly, however, an average of 78% of the RBC stages of EPI parasites (bearing plasmid pPyrFlu as an episome) were found to fluoresce (Table 1). Analysis of the sporogonic cycle of parasites bearing plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP in an episomal form led to similar findings, i.e., an average of 55% of the RBC stages of the parasite brightly fluoresced after one life cycle. In both cases, Southern blot hybridization confirmed the presence of the plasmid in an extrachromosomal form in RBC stages and failed to detect any trace of plasmid integration into the parasite genome (data not shown). Therefore, despite the numerous nuclear divisions that had occurred during parasite sporogony in mosquitoes (one zygote yielding ∼10,000 sporozoites), schizogony in EEF in the vertebrate liver (one sporozoite yielding ∼10,000 merozoites), and schizogony in RBC (one merozoite yielding 8 to 12 merozoites at each cycle), both pPyrFlu and pPyrFlu-TRAP plasmids were maintained in the absence of pyrimethamine selection. The stable maintenance of plasmids in mosquito stages of P. berghei in the absence of adverse effects on parasite infectivity should be of great help in the molecular analysis of the malarial sporogonic cycle. For example, it should be possible to conduct protein structure-function analyses via complementation of knockout lines with plasmids that express altered versions of the target protein.

Concluding remarks.

The PyrFlu cassette appears to be a useful addition to the P. berghei transformation system. The relatively small size of the bifunctional cassette (5 kb) is compatible with the generation of more complex targeting plasmids, exemplified by plasmid pPyrFlu-TRAP. One copy of the PyrFlu cassette is sufficient to allow the selection of RBC stages of P. berghei via resistance to pyrimethamine or by flow cytometry. Pyrimethamine selection alone frequently yields a proportion of spontaneous pyrimethamine-resistant mutants that appear like the WT by Southern hybridization. The concomitant fluorescent signal should then allow the further selection of targeted clones by flow cytometry. A particularly appealing feature of a GFP-based marker is its potential use in negative-selection procedures. It should be possible by FACS to select spontaneous intrachromosomal recombination events that occur in a clonal population of parasite integrants containing the PyrFlu cassette, which revert to a WT structure and a nonfluorescent phenotype. Such a two-step approach with PyrFlu plasmids could then be used to introduce subtle gene mutations in a final locus devoid of the exogenous sequence.

The fluorescence emitted by PyrFlu-expressing parasites should also facilitate the characterization of their phenotypes, particularly in vivo. In posterythrocytic stages, mosquito oocysts and liver EEF are readily detectable due to the high number of nuclei they contain. Future work will aim at achieving higher levels of fluorescence in sporozoites, such as by fusing GFPmut2 to proteins highly produced at this stage of the parasite. This would facilitate the analysis of sporozoite-host interactions and possibly allow FACS selection of infected hepatocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. vanWye and K. Haldar for kindly providing GFPmut2, John Hirst for technical assistance in flow cytometry, and Maria Cecilia Marcondes for technical assistance in immunocytochemistry.

This work was supported by grants from Burroughs Wellcome Fund (New Initiative in Malaria Research), UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme, the Karl-Enigk Foundation, and the NIH (AI-43052). A.A.S. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Physician Postdoctoral Fellow. R.M. is a recipient of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cerami C, Frevert U, Sinnis P, Takacs B, Clavijo P, Santos M J, Nussenzweig V. The basolateral domain of the hepatocyte plasma membrane bears receptors for the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. Cell. 1992;70:1021–1033. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cormack B P, Valdivia R H, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delagrave S, Hawtin R E, Silva C M, Yang M M, Youvan D C. Red-shifted excitation mutants of the green fluorescent protein. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:151–154. doi: 10.1038/nbt0295-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gantt S M, Myung J M, Briones M R S, Li W D, Corey E J, Omura S, Nussenzweig V, Sinnis P. Proteasome inhibitors block development of Plasmodium spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2731–2738. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heim R, Cubitt A B, Tsien R Y. Improved green fluorescence. Nature. 1995;373:663–664. doi: 10.1038/373663b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ménard R, Janse C. Methods: a companion to methods in enzymology—analysis of apicomplexan parasites. Vol. 13. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1997. Gene targeting in malaria parasites; pp. 148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misteli T, Spector D L. Applications of the green fluorescent protein in cell biology and biotechnology. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;15:961–964. doi: 10.1038/nbt1097-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunes A, Thathy V, Bruderer T, Sultan A A, Nussenzweig R S, Ménard R. Subtle mutagenesis by ends-in recombination in malaria parasites. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2895–2902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sultan A A, Thathy V, Frevert U, Robson K J, Crisanti A, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig R S, Ménard R. TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of Plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. 1997;90:511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuji M, Mattei D, Nussenzweig R S, Eichinger D, Zavala F. Demonstration of heat-shock protein 70 in the sporozoite stage of malaria parasites. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:16–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00932618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Wel A M, Tomas A M, Cocken C, Janse C J, Waters A P, Thomas A W. Transfection of the primate malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi using entirely heterologous constructs. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1499–1503. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dijk M R, Janse C J, Waters A P. Expression of a Plasmodium gene introduced into subtelomeric regions of Plasmodium berghei chromosomes. Science. 1996;271:662–665. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dijk M R, Vinkenoog R, Ramesar J, Vervenne R A W, Waters A P, Janse C J. Replication, expression and segregation of plasmid-borne DNA in genetically transformed malaria parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;86:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)02843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.vanWye J D, Haldar K. Expression of the green fluorescent protein in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;87:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waters A P, Thomas A W, van Dijk M R, Janse C J. Methods: a companion to methods in enzymology—analysis of apicomplexan parasites. Vol. 13. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1997. Transfection of malaria parasites; pp. 134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Y, Kirkman L A, Wellems T E. Transformation of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites by homologous integration of plasmids that confer resistance to pyrimethamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1130–1134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]