SUMMARY

We describe an effort (“Codebook”) to determine the sequence specificity of 332 putative and largely uncharacterized human transcription factors (TFs), as well as 61 control TFs. Nearly 5,000 independent experiments across multiple in vitro and in vivo assays produced motifs for just over half of the putative TFs analyzed (177, or 53%), of which most are unique to a single TF. The data highlight the extensive contribution of transposable elements to TF evolution, both in cis and trans, and identify tens of thousands of conserved, base-level binding sites in the human genome. The use of multiple assays provides an unprecedented opportunity to benchmark and analyze TF sequence specificity, function, and evolution, as further explored in accompanying manuscripts. 1,421 human TFs are now associated with a DNA binding motif. Extrapolation from the Codebook benchmarking, however, suggests that many of the currently known binding motifs for well-studied TFs may inaccurately describe the TF’s true sequence preferences.

Keywords: Transcription factor, TF, ChIP-seq, HT-SELEX, GHT-SELEX, SELEX, SMiLE-seq, Motif, DNA-binding specificity, PWM, PBM, Codebook

Introduction and motivations

The human genome encodes >1,600 putative transcription factors (TFs), defined as proteins that bind specific DNA sequence motifs and regulate gene expression1. These DNA binding motifs are most commonly modelled as a Position Weight Matrix (PWM) that describes the relative preference of the TF for each nucleotide base pair in the binding site2,3, and can be visualized as a sequence logo4. Several hundred putative human TFs still lack DNA binding motifs1, and even for well-characterized TFs, it remains controversial whether the reported motif model is accurate5,6, and to what degree the TF’s sequence specificity contributes to binding site selection in living cells7,8. These uncertainties are due in part to the fact that different methods for measuring TF binding, and for deriving PWMs from these data, can have different inherent limitations and biases2. Such shortcomings represent fundamental hurdles for the analysis of gene regulation, as well as a myriad of related tasks in genome analysis, including the interpretation of conserved genomic elements and sequence variants, or genetic engineering such as synthetic enhancer design.

To address these issues, we analyzed a large majority of the as-yet uncharacterized human TFs1, as well as several dozen previously studied control TFs9,10, using a panel of assays that provide different perspectives on DNA sequence specificity. This unprecedented effort generated what we believe is the largest uniform data structure of its kind. We refer to this international collaborative project as the “Codebook/GRECO-BIT Collaboration”: the reagent set and laboratory experiments were initiated as the “Codebook Project”, alluding to the fact that TFs decode individual “words” in the genome, and the existing Gene REgulation COnsortium Benchmarking IniTiative, GRECO-BIT, was then engaged for much of the data analysis and benchmarking.

In this paper, we present an overview of the data collection and its analysis, the resulting data, several major outcomes and findings of the Codebook study, and examples of prevalent phenomena and applications. We also introduce web resources that can be used to access the primary and processed data, including the PWMs. Accompanying manuscripts provide greater depth regarding biological findings, new assays, and intriguing TF families, as well as methods for identifying binding patterns (i.e. PWM derivation) and PWM benchmarking (Table S1).

Codebook reagents, assays, and data structure

Figure 1 provides a schematic of the Codebook project. We chose 332 putative TFs (i.e., “Codebook TFs”) (Table S2) for study by starting with a previously described list of 427 hand-curated “likely” human TFs that lacked known motifs or any large-scale DNA binding data1. We removed 95 C2H2 zinc finger (C2H2-zf) proteins for which we were already aware of unpublished data (mainly from our prior collaboration with ENCODE11). As of June 2024, most of these putative TFs still lack motifs, outside of the Codebook study: of the 332, only 107 have PWMs on Factorbook12 and/or HOCOMOCO13. Many of these motifs appear to be simple repeats, or common cofactor motifs (such as CTCF, REST, and CRE sites) (examples in Figure S1), but among the 107, 59 have at least one PWM that appears plausible for representing specificity of the TF (see below).

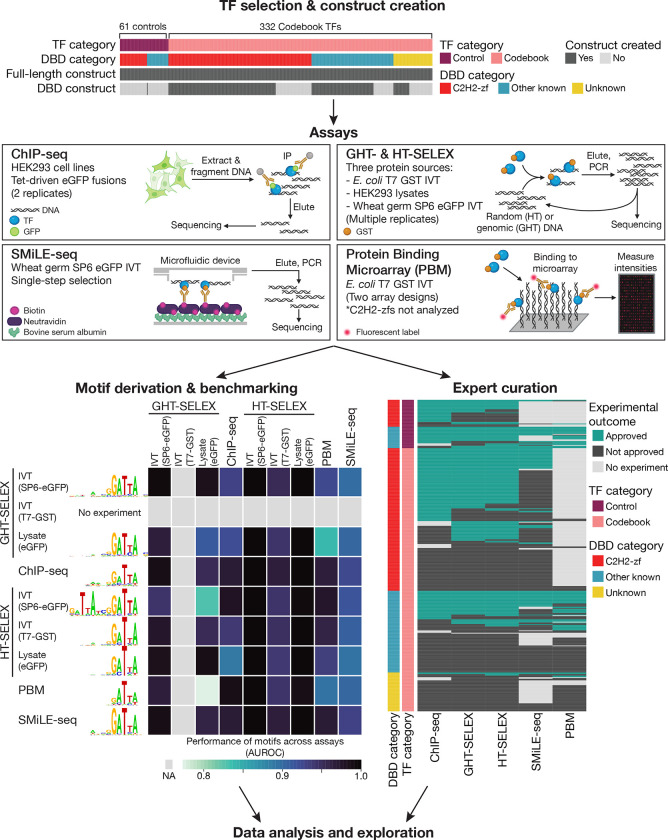

Figure 1. Codebook project overview.

Top, Categories of 393 TFs assayed and their associated constructs. Middle, Graphical summary of assays employed. Bottom left, Example of performance (as AUROC) of the best performing PWM for TPRX1, for each combination of experiment type – one for motif derivation (rows), and one for motif testing (columns). Bottom right, Depiction of the approval process for each individual experiment, including comparison of motifs and/or binding sites between replicates, evaluation of motifs across experiments, and motif similarity between related TFs (see Experiment evaluation by expert curation). Heatmap shows approved experiments for all 393 TFs across all experiment types.

Among the 332 Codebook TFs, 180 contain C2H2-zf domains, while another 103 contain another type of well-known DNA-binding domain (DBD). Forty-nine did not have an established DBD at the outset of the study; these were mainly identified as sequence-specific in studies of individual proteins or regulatory sites1. We simultaneously analyzed 61 control TFs, encompassing 29 well-characterized TFs representing diverse human DBD classes9, and an additional 32 C2H2-zf proteins for which published ChIP-seq data were available and had led to a binding motif10. For these controls, we incorporated the published SMiLE-seq and ChIP-seq data, rather than repeating the experiments.

To study the 332 Codebook proteins, we manually designed 716 protein-coding inserts, corresponding to full-length coding regions of the dominant isoform, and one or more DBDs (or subsets of C2H2-zf domain arrays), if there was a known DBD (Table S3). We employed up to three different expression vectors for each insert, as required for the different assays in Figure 1, resulting in a total of 1352 new distinct constructs (Table S4). One of the assays, GHT-SELEX (Genomic high-throughput SELEX), is a new variant of HT-SELEX which is performed with fragmented genomic DNA. As described in the accompanying manuscript14, GHT-SELEX yields peaks, analogous and often in agreement with ChIP-seq. GHT-SELEX thus provides a new perspective that bridges in vitro and in vivo DNA binding. HT-SELEX and GHT-SELEX were performed with multiple protein sources (mammalian cell extracts, and two different systems for in vitro transcription/translation) whereas SMiLE-seq and PBMs were performed with only one protein source. Multiple replicates were performed in many cases, for all assays.

The full Codebook data structure is composed of a total of 4,873 technically successful experiments (i.e. they produced data that could be analyzed by at least some subsequent processes) (Table S5), The Codebook data structure, experimental information, and PWMs (see below) are accessible at multiple sources (see Data Availability). Each experiment corresponds to one of the Codebook constructs (or one of the control constructs), analyzed using one of the assays, with one of the protein sources. Not every protein or every insert was analyzed in every assay, by design. For example, the ChIP-seq data only utilize full-length proteins, while Protein Binding Microarray data include only DBD constructs. Long human C2H2-zf domain arrays typically fail in PBMs, and such experiments were omitted. We note that, in general, experiments that are technically successful may not yield motifs that are specific to the TF assessed and supported by other data types (see below). For example, ChIP-seq can detect both indirect and non-sequence-specific DNA binding, as we explored separately15. We also emphasize that the in vitro assays described here were conducted with unmethylated DNA. We explored the sensitivity of a subset (79) of the Codebook TFs to DNA methylation in an accompanying study, however, which introduces the methylation-sensitive SMiLE-seq variant (meSMS)16. DNA binding interactions of 17 of the 79 were impacted by methylation, encompassing inhibition (10) and increased binding or alternative binding sites (7); these data were not incorporated in the analyses described herein.

Motifs are obtained from most C2H2-zf proteins, and half of those containing other DBD classes, but only a few proteins with previously unknown DNA binding domains

We next derived and examined motifs as PWMs for all the experiments in a semi-automated expert curation format, to identify “approved” experiments (i.e. experiments that contained clear enrichment of credible binding motifs (see Methods)). This effort is described in detail in a separate manuscript that describes motif benchmarking, data sets, and success measures17, and also introduces a web resource that makes all of the motifs available for browsing and download. Briefly, our primary approach was to ask whether similar motifs were obtained for the same protein from different assays and whether the PWMs scored highly by a panel of criteria, including predictive capacity in other data types (depicted schematically in Figure 1, bottom left), adapting a previously described motif benchmarking framework18. To increase our ability to derive motifs that would score highly across data sets, we employed ten motif discovery tools, ranging from the widely used MEME suite19 to approaches based on machine learning or biophysical modeling, such as ExplaiNN20 and ProBound21, thus producing hundreds of motifs per TF. In total, 177 Codebook TFs were associated with “approved” datasets (Figure 1, bottom right), and a total of 1,072 experiments associated with these 177 TFs were approved (Tables S2 and S5). 59/61 controls were also approved, suggesting a low per-TF false-negative rate.

The 177 Codebook TFs for which there are approved experiments are dominated by the C2H2-zf domain class, for which 67% (121/180) had approved experiments. These proteins typically contain an array of C2H2-zf domains that bind DNA in tandem22. Some C2H2-zf domains can bind RNA, protein, or other ligands23–25. The Codebook outcome indicates that most C2H2-zf proteins are indeed DNA-binding, although it does not rule out their other activities. Experiments for roughly half (50/103, or 49%) of Codebook TFs in other established DBD classes were also successful. Lack of approved experiments for a putative TF could represent false negatives, which could arise from lack of an obligate binding partner, a requirement for epigenetically modified DNA, lack of requisite post-translational modification in our experiments, or limitations of the methods. Alternatively, they could represent true negatives which are not unexpected; some bona fide DBD classes are known to have subtypes that lack sequence specificity (e.g. HMG26). Among the Codebook proteins lacking a well-established DBD, only 6/49 (12%) yielded approved experiments (and thus motifs) (discussed in more detail below), suggesting that many of them may indeed lack sequence specificity.

We emphasize that our approval process was intentionally conservative, and many experiments were not approved despite being informative in some way (e.g. ChIP-seq yielding reproducible peaks, but no motif, which could indicate indirect association through other TFs or chromatin binding; these are explored in an accompanying manuscript15). We also note that our success criteria assume that the sequence preferences of TFs can be represented by PWMs. It is conceivable that uncharacterized TFs could instead recognize interspersed sequence patterns or other features of the DNA sequence that are not readily captured by PWM models or short k-mers.

Diversity and complexity among Codebook TF motifs

To gain an overview of the Codebook TF motifs, and to generate a representative PWM set, we next used expert curation to select a single PWM that is (i) high-performing among all “approved” experiments17 (see Methods), (ii) representative of other high-performing PWMs for the same TF, (iii) consistent with expectation for the class of TF (e.g. the C2H2-zf “recognition code”27), and (iv) high information content (IC) (i.e. with a “tall” sequence logo), provided it does not compromise PWM performance. The PWM selected in this process is typically not the highest scoring by criterion (i) alone, as our extensive process typically generated dozens of high-performing PWMs from which to choose, for approved experiments17. Table S6 shows sequence logos for these curated PWMs and their properties; the PWM IDs are given in Table S2, and all PWMs can be downloaded (see Data Availability). Notably, no data type or motif derivation method stood out as highly preferred by the curators, who were blinded to the source (i.e. data type and derivation method for the PWMs).

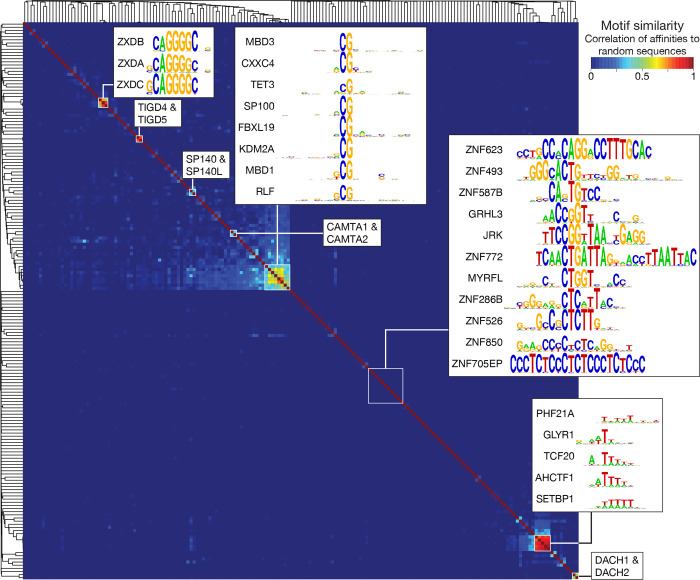

Figure 2 shows an overview of similarity28 among the curated PWMs. Small clusters along the diagonal mostly correspond to the handful of paralogs analyzed (e.g. TIGD4 and 5, SP140 and SP140L, DACH1 and 2, CAMTA1 and 2, and ZXDA, B, and C). In the middle of Figure 2 is a set of eight TFs that mainly bind CG dinucleotides, leading to similarity in DNA-binding, and in the lower right is a group of five AT-hook proteins that have similar preferences to A/T containing sequences. Most of the Codebook TF PWMs are unlike each other, however, and display a low similarity to any other known PWM17 (examples are shown in Figure 2). This result is partly explained by the large number of C2H2-zf proteins, which are known to differ in their DNA-contacting “specificity residues”29. Regardless, a large majority of the Codebook TF motifs are apparently new, and all previous analyses in human regulatory genomics would have been unaware of the ~150 visibly distinct, curated motifs described here.

Figure 2. Similarity of Codebook TF motifs.

Symmetric heatmap displaying the similarity between expert-curated PWMs for each pair of Codebook TFs, clustered by Pearson correlation with average linkage. The PWM similarity metric is the correlation between pairwise affinities to 200,000 random sequences of length 50, as calculated by MoSBAT28. Pullouts and labels illustrate specific points in the main text.

For dozens of TFs, the curated PWM had a degenerate appearance, i.e. there are few or no positions at which a specific base is absolutely required. Indeed, for fifty-two of them, no individual base at any position achieved a bit score of ≥1.4 in the curated PWM (equivalent to roughly >10% of aligned binding sites having a variant base at that position) (Figure S2A). Systematically increasing the information content (IC) (i.e., “unflattening” the sequence logo, and increasing the specificity) of the low-IC curated PWMs almost universally reduced performance (Figure S2B,C), indicating that the degeneracy is required for accuracy. We also found that, overall, IC is not predictive of motif performance in the benchmarking effort17. It is counterintuitive that degeneracy (i.e. lower inherent specificity) would lead to better predictive capacity, but we note that similar findings by others support the validity of the result30–32.

We propose several explanations for this observation. First, lower IC tends to make affinity distributions across all possible k-mers less digital (i.e. it removes all-or-nothing dependence on specific base positions), which could facilitate the gradual evolution of cis-regulatory sequences. Second, homomeric binding (possibly via “avidity”33), which a body of evidence suggests is a widespread mechanism14,34, should reduce reliance on optimal specificity to a single binding site, and strong binding sites may evolve more readily if weak binding sites tend to occur more frequently (and are selected). Third, motif degeneracy may be a consequence of forcing a single PWM to represent the specificity of TFs that, in reality, recognize multiple related motifs. For example, the dependency of binding energy on both enthalpy and entropy can lead to two distinct sequence optima35; in another example, different spacings of bZIP half-sites cannot be represented by a single PWM36. Consistent with this last possibility, the accompanying manuscript17 finds that combining multiple PWMs (by Random Forests) typically produces models that are more accurate across platforms, relative to any single PWM.

The C2H2-zf proteins present a special case in which a single TF might be anticipated to require multiple PWMs, because long C2H2-zf domain arrays could utilize different segments of the array to bind to either overlapping or distinct sites37. Until now, however, examples were sparse and anecdotal. In an accompanying manuscript14, we present evidence that C2H2-zf proteins often bind multiple sequence motifs that correspond to different subsets of the extended motif predicted by the recognition code (i.e. protein-sequence-based computational prediction of C2H2-zf-domain specificities), consistent with varying usage of the C2H2-zf domains at different genomic binding sites being commonplace.

Underappreciated DNA-binding domains

The six Codebook proteins that were lacking canonical DBDs, yet yielded “approved” experiments and thus motifs (CGGBP1, NACC2, TCF20, PURB, DACH1, and DACH2), appear to represent cases of DBDs that were poorly described at the outset of the study. We and others have recently described CGGBP1 as the founding member of an extensive family of eukaryotic TFs derived from the DBDs of transposons38,39. NACC2 contains a BEN domain, which over the last decade has been clearly established as a sequence-specific DBD40,41. TCF20 contains a potential AT-hook42 (below the conventional Pfam scoring threshold), and yielded an AT-hook-like motif. PURB is composed largely of three copies of the PUR (Purine-rich-element binding) domain; it yielded a motif on four different PBM assays (resembling ACCnAC/GTnGGT), which is unlike its previously established binding site (CTTCCCTGGAAG)43. The sequence specificity of this protein thus remains enigmatic.

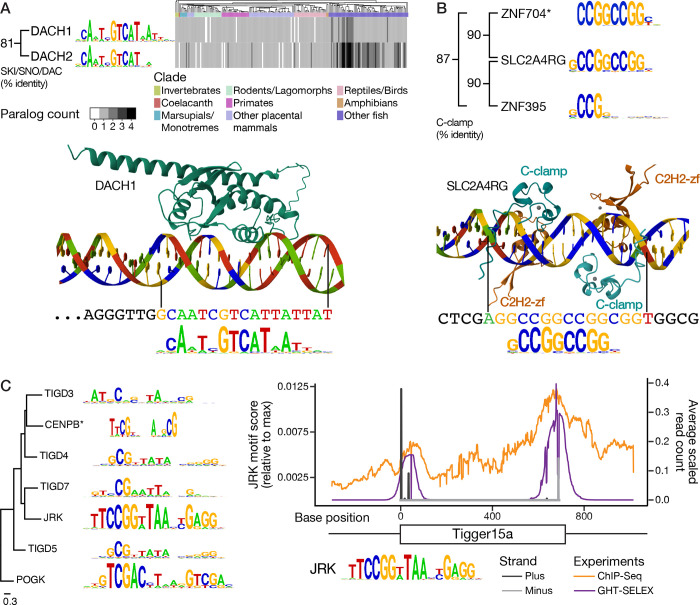

DACH1 and DACH2 are paralogs that yielded very similar motifs (Figure 3A). They contain a SKI/SNO/DAC domain, shared with their Drosophila counterpart Dachshund, from which their name is derived. A Forkhead-like motif (different from the one we obtained) was previously described for DACH144, but to our knowledge, no other homolog has been reported as being sequence-specific. The SKI/SNO/DAC domain includes a helix-turn-helix (HTH), a feature found in many DBDs. Alphafold345 predicts that the HTH inserts into the major groove precisely at the PWM-predicted binding site within an extended DNA sequence (Figure 3A). Interpro46 lists over 7,000 proteins containing SKI/SNO/DAC domains, entirely in metazoans, with specific expansions in several fish lineages, particularly barbels and salmonids47 (Figure 3A). SKI/SNO/DAC therefore may represent an expansive class of poorly-characterized DBDs.

Figure 3. Neglected DNA-binding domains.

Overview of new motifs for previously understudied TF families. A, Top, Number of DACH1 and DACH2 orthologs (union of one-to-one and one-to-many) across Ensembl v111 vertebrates and selected invertebrates. Species order reflects the Ensembl species tree. Bottom, AlphaFold3-predicted structure of the DACH1 SKI/SNO/DAC region (residues 130 – 390) bound to an HT-SELEX ligand sequence with a high-scoring PWM hit. B, Top, Sequence logos and sequence relationships of human C-Clamp domains (*ZNF704 motif from 50). Bottom, AlphaFold3-predicted structure of two full-length SLC2A4RG proteins bound to a CTOP sequence with flanking sequences (chr17:48,048,369–48,048,401), and four Zn2+ ions (grey). The remainder of the proteins (beyond the C-clamp and C2H2-zf domains) are hidden, for visual simplicity. C. Left, Sequence logos of human TFs that are derived from the domestication of Tigger and Pogo DNA transposon DBDs elements and have known DNA binding motifs. Tree is a maximum-likelihood phylogram from FastTree92, using DBD sequence alignment with MAFFT L-INS-I93, rooted on POGK, which is derived from an older family of Tigger-like elements94,95. Sequence logos are Codebook-derived, except for CENPB96. Right, average per-base read count over Tigger15a TOPs in the human genome, for JRK ChIP-seq (orange) and GHT-SELEX (purple), with sequences aligned to the Tigger15a consensus sequence. JRK PWM scores at each base of the Tigger15a consensus sequence are shown in black (plus strand) and grey (minus strand).

In addition to these six examples, the sequence specificity of SLC2A4RG and ZNF395 – both C2H2-zf proteins – appears to reside in their C-clamp. The domain is also present in TCF7L and LEF proteins, where it is known to bind DNA alongside their HMG domains48. Alphafold345 predicts that the single C2H2-zf domains in SLC2A4RG and ZNF395 are not the main determinants of DNA-binding (although they may contact the major groove), but instead that a region corresponding to the C-clamp model on the SMART database of protein domains49 binds the major groove precisely at the PWM-predicted binding site within an extended DNA sequence (Figure 3B). There is one additional human TF matching the C-clamp model, ZNF704, with a published PWM that is virtually identical to that of SLC2A4RG and ZNF395 (CCGGCCGG)50 (Figure 3B). Like the SKI/SNO/DAC domain, the C-clamp is found broadly across animals46, and may therefore also represent a large class of unexplored DBDs.

Widespread contribution of transposons to the human TF repertoire

Sixteen of the Codebook TFs (and two controls) that yielded approved experiments possess a DBD that has been co-opted from a DNA transposon: CGGBP139, five proteins containing BED-zf domains51, six with the related CENBP or Brinker domains52, two with transposon-derived Myb/SANT domains53, one with a MADF domain, and FLYWCH154. The PWMs obtained for CENPB/Brinker TFs are often long (Figure 3C). A striking example is JRK, a TF that is derived from an ancient domesticated Tigger element DBD55, and is found broadly in mammals47. All DNA transposons, including Tigger, have been extinct in the human lineage for over 40 million years56. Remarkably, genomic binding of JRK is enriched for binding to a subset of Tigger elements, and the consensus sequence for these same elements has a PWM-predicted binding site for JRK in the terminal repeats of these elements (Figure 3C), consistent with its presumed ancestral role in transposition. We speculate that JRK may represent a case of co-option in which the same DNA transposon simultaneously introduced both a multitude of cis-regulatory elements, and the TF that binds them.

The Codebook data also underscore that many TFs bind preferentially and intrinsically to specific repeat classes. These interactions are explored in greater detail in the accompanying manuscripts14,15. Binding to endogenous retroelements is known to be a common property of the KRAB-domain-containing C2H2-zf (KZNF) subfamily in vivo27, but until now it has not been clear that the recruitment is defined almost entirely by the sequence specificity of the KZNFs alone. The combination of assays run here, particularly GHT-SELEX, extends earlier observations by pinpointing the exact binding sites, and demonstrating that these proteins typically have high specificity for these elements, because they bind preferentially to precisely the same elements in vitro. Binding preferentially to retroelements is not limited to KZNFs, but includes other C2H2-zf proteins and other classes of TFs. For example, binding sites for TIGD3, a transposon-derived TF which is closely related to JRK, are enriched for binding to L1s, SINEs, and DNA transposons15.

Codebook PWMs predict TF binding in independent data and across cell types

The Codebook project was conducted over a period of nearly six years, and during this time, several large-scale studies aimed at systematic ChIP-seq analysis of human TFs (e.g. ENCODE) were published11,57,58. Combined, the ENCODE data portal59 and GTRD60, a compilation database, contain ChIP-seq and ChIP-exo peak data for 214 of the Codebook proteins, including 105 that were among the 166 with either “approved” Codebook ChIP-seq experiments (Table S7), or with ChIP-seq replicates that yielded reproducible peak sets15. We grouped both types of ChIP-seq data in our study and compared them to the external data. We first asked whether Codebook peak sets overlapped with these external peak sets for the same TF. Among the major ENCODE cell lines, the highest overlap values (Jaccard index) were found with experiments utilizing the same cell type (HEK293 cells) (Figure S3A,B). Slightly lower Jaccard values were obtained for experiments performed in HepG2 and other cell types, which would be expected given the altered chromatin profiles in different cell types, but over one-third were still clearly nonrandom (Jaccard > 0.1) (Figure S3C). Overlap scores with published K562 data, which dominate the external ChIP data due to a single large ChIP-exo study58, were much lower, overall (Figure S3D). We conclude from these analyses that the Codebook ChIP-seq data provide mainly new information.

We next asked how effectively the Codebook PWMs predict binding of TFs to peak sets in the published datasets. Consistent with the fact that the Codebook and external peaks often overlap, the Codebook PWMs had a median AUROC of 0.71 on the external HEK293 data, and were nearly as effective in predicting peak sets in other cell types (Figure S3E), illustrating that the Codebook PWMs are predictive across studies and cell types. We also asked how the predictive capacity of the Codebook PWMs compared to PWMs that appear in the latest versions of Factorbook12, JASPAR61, and HOCOMOCO13 (Table S8). We identified 19 TFs with at least one successful Codebook ChIP-seq experiment and Codebook PWM, at least one external ChIP-seq experiment, and at least one PWM from an external database. In most cases, both the Codebook and external PWMs scored well on both Codebook and external peak sets (Figure S3F,G), supporting the validity of both PWMs and both peak sets. For seven proteins, low scores were obtained in at least some tests, however. For four of them, the independent Codebook in vitro data support the Codebook PWM; for two of the others, the external PWM scores poorly on Codebook peaks, while the Codebook PWM scores well on Codebook and external peak sets (Figure S3H). We conclude that the Codebook PWMs are generally more reliable than those published previously, likely because they are aided by confirmation of PWM performance across multiple data types that were not available in previous studies

Codebook TF binding sites suggest functions for tens of thousands of conserved elements

Together, the Codebook assays and PWMs can be used to pinpoint genomic loci that are bound directly by each TF in vivo (i.e., in ChIP-seq), by identifying those that are also bound in vitro (i.e., GHT-SELEX), and that contain a PWM hit, thus allowing base-level resolution. We refer to these as “triple overlap” (TOP) sites, which are taken as the overlap of the three sets (ChIP-seq, GHT-SELEX, and PWM hits) after applying optimized score thresholds for each (see Methods for details). This process produced a median of 455 TOP sites for 101 Codebook proteins, and a median of 3,014 TOP sites for 36 control TFs.

To gauge functionality of the TOP sites, we examined whether the pattern of per-nucleotide conservation13 at each site is consistent with the TF’s sequence preference driving local sequence constraint (see Methods for details). Figure 4A shows several examples illustrating that this approach readily detects apparent conservation of PWM hits, for both control and Codebook TFs. In total, 85/101 Codebook TFs (as well as 33/36 controls) displayed conservation of at least one TOP site (FDR < 0.1), and in total we identified 121,785 such conserved TOP sites (“CTOP” sites) (83,621 for Codebook TFs and 38,164 for controls), encompassing 1,577,298 bases. These results, summarized in Figure S4 and in greater detail in an accompanying manuscript15, provide strong support for the functional importance of Codebook TF binding sites in the genome.

Figure 4. Conservation of Codebook TF binding sites and association with genomic features.

A, Heatmaps of phyloP scores over the PWM hit and 50 bp flanking for TOP sites for four TFs (two controls and two Codebook TFs). Statistical test results (see main text and Methods) are indicated at right. B, Left, Donut plot displays the proportion and number of clusters of conserved TOP (CTOP) sites that overlap the genomic features indicated. Middle, Bar plot displays the mean # of individual CTOPs contained within clusters that overlap the examined genomic regions. C. A 1,420-base, CpG-island-overlapping CTOP cluster (chr12:120368293–120369713). Zoonomia 241-mammal phyloP scores and Multiz 471 Mammal alignment PhastCons Conserved Elements are shown. D, Bar plot of the frequency of TFs with CTOPs that occur most frequently in CTOP clusters that overlap CpG and non-CpG protein coding promoters, respectively. E, CTOP cluster overlapping the non-CpG promoter at chr12:57,745,278–57,745,396. F, CTOP site for the KRAB-C2H2-zf protein ZNF689, overlapping an L1ME4a located at chr16:25,403,631–25,403,717.

Many of the CTOP sites were either overlapping or adjacent to CTOP sites for the same or other TFs. We grouped them into 50,375 clusters, based on proximity (allowing a maximum of 100 bases, to capture binding to different segments of what may be the same regulatory element). Codebook TFs with the largest number of CTOP sites were typically associated with CpG islands, which represented 37.5% of all the clusters (Figure 4B). The majority of protein-coding promoter CpG islands (58.7%, 7,892/13,427) contained CTOP sites, with an average of 4.3 CTOP sites per CpG island. Moreover, 59/101 (58%) of all Codebook TFs had at least one CTOP site within a CpG island. An example CTOP that overlaps a CpG island is shown in Figure 4C.

The extent of specific, conserved, and intrinsic occupancy of CpG islands by many TFs of diverse classes is, to our knowledge, unexpected. The abundance of CG dinucleotides in CpG islands has been attributed primarily to their lack of methylation in the germline, rather than primary sequence constraint62. There is one class of TFs (the CXXC proteins) that is known to specifically recognize unmethylated CG dinucleotides and to modulate chromatin at promoters62, and we do observe this property for the CXXC proteins KDM2A, CXXC4, FBXL19, and TET3. Intriguingly, however, many of the Codebook TFs with CTOP sites in CpG islands recognize elaborate C/G rich motifs, rather than CG dinucleotides (Figure 4C).

CTOP clusters were also found in non-CpG island protein-coding promoters (Figure 4B) (855/6,606 such promoters, defined as −1000 to +500 relative to TSS). These clusters are not dominated by any specific TFs, although some TFs are more prevalent than others (e.g. CTOPs for the controls ELF3 and CTCF, and Codebook TF ZBTB41, are each found in ~10% of all non-CpG promoters) (Figure 4D). Figure 4E shows an example of one such non-CpG promoter cluster, occurring early in the first intron of the TSPAN31 gene, which exhibits apparent conserved spacing and orientation of multiple Codebook TF binding sites. In contrast, CTOP clusters outside of promoters and CpG islands often contain just one or two CTOP sites (Figure 4B). One example is a very strongly conserved intergenic ZNF689 binding site found in an L1ME1 transposon; this site is just over 100 bp from a predicted enhancer containing a CTCF binding site (Figure 4F).

A total of 42,200 distinct CTOP clusters (out of 50,375) overlapped catalogued conserved elements (UCSC PhastCons track), thus indicating a likely biochemical function for these elements. For the remaining 8,175, detection of functional elements from base-level scores is now augmented by the TF binding information. Relatively few CTOP clusters overlapped with known enhancers, however: only 4,768 are found in the extensive GeneHancer annotation set63, and 2,819 overlap with HEK293 enhancers (defined by ChromHMM15). This low overlap could be attributed to the relatively rapid evolution of enhancers64, or to lack of complete knowledge of enhancer identities. We also note that, even for well-studied TFs, most TOP sites were classified by our methods as not conserved, and that roughly half of the Codebook TFs had few or no conserved TOP sites (particularly the aforementioned retroelement-binding KZNFs) (Figure S4). Lack of conservation does not demonstrate that a sequence is not a functional binding site, however, as turnover in functional genomic binding sites of TFs is common65. This result is nonetheless consistent with the notion that many TF binding sites are coincidental, redundant, or serve(d) a purpose other than host genome regulation. In the accompanying manuscript15, we explore potential functions for proteins that frequently bind non-conserved sites in genomic “dark matter”.

Relationships between Codebook TFs, SNVs and chromatin

Because the CTOP sites are evolutionarily constrained, we reasoned that they might also be less frequently associated with human sequence variation, and indeed, 92.6% of CTOPs lack SNPs and other common short variants, while only 82.1% of unconserved TOPs are variant-free. Both are depleted of common SNPs, however, when examined separately (Fisher’s exact test p ~ 2.4×10−307 and odds ratio = 0.657, p ~ 0 and ratio = 0.872, respectively). The CTOP SNPs also have a lower impact on PWM scores: on average, the relative PWM score for SNP-containing CTOP sequences declines by 0.027, while PWM scores for unconserved TOPs decline by 0.057 (median declines of 0.011 and 0.0285, respectively). CTOPs are furthermore depleted of common short indels (Fisher’s exact test, p ~ 1×10−150, ratio = 0.77), while unconserved TOPs (which often overlap with simple repeats) are enriched (p < 1×10−150, ratio = 3.318), relative to genomic background. The depletion of common SNPs is consistent with ongoing purifying selection of CTOPs within recent human populations, and the association of SNPs with specific TFs should provide a ready means for directed study of the functionality of the encompassed SNPs.

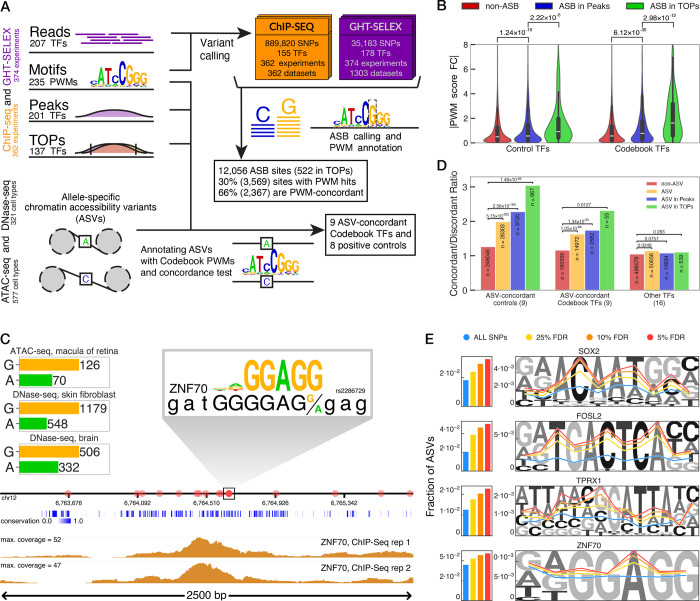

We reasoned that the GHT-SELEX and ChIP-seq experiments would also allow direct assessment of allele-specific binding (ASB) of TFs, by quantifying allelic imbalance of read counts at SNVs. We note that the data were not initially intended for this purpose, and caveats included relatively low read counts, linked SNVs, and the fact that HEK293 has an abnormal karyotype and was derived from a single individual. Nonetheless, there was sufficient coverage in the sequencing data to make 925,003 variant calls overlapping with dbSNP common SNPs (889,820 variant calls from 362 ChIP-seq experiments and 35,183 from 374 GHT-SELEX multi-cycle experiments), at 122,364 unique genomic locations (Figure 5A, Figure S5A, Table S9). 10,009 of these genomic locations were associated with 12,056 ASBs of 160 Codebook TFs and 46 positive controls in ChIP-seq (10,571 ASBs) or GHT-SELEX (1,485 ASBs) samples, i.e. there was a significant imbalance in the sequencing reads for the two alleles overlapping the respective SNPs. Among these ASBs, 3,569 also overlapped a PWM hit for the TF, and for 2,367 of them, the read count imbalance was concordant with the change in PWM scores, i.e. the allele with the higher read count also has a higher PWM score (Figure S5A,B, Table S9). (ASBs that do not overlap a PWM hit may be linked to a “causative” SNV, which may act indirectly). ASBs for control TFs were strongly enriched with previously-known ASBs of those TFs (ADASTRA database, odds ratio of 5.7, p < 10−15, Fisher’s exact test)66, and nearly three-quarters of ASBs coincided with eQTLs (GTEx database, odds ratio of 1.2, p < 10−15, Fisher’s exact test)67 (Figure S5C), supporting the reliability of the detected ASBs as well as the validity of detected PWM hits.

Figure 5. Allele-specific transcription factor binding and chromatin accessibility.

A, Scheme of the analysis: identification of allele-specific binding sites (ASBs) from Codebook ChIP-Seq and GHT-SELEX data and annotation of allele-specific chromatin accessibility variants (ASVs) with the Codebook motifs. B, Distribution of PWM score (log-odds) fold changes between alleles for non-ASB SNPs, ASBs in peaks, and ASBs in TOPs. Left, 32 positive control TFs, Right, 85 Codebook TFs. P-values: Mann-Whitney U test. C. An example ASV for ZNF70, in chr12:6,763,200–6,765,850, around 1kb upstream of the PTMS gene. Onset shows the exact location of the ASV (with A/G alleles) together with the corresponding PWM hit. Allelic read counts for three available ATAC- and DNase-seq samples are shown on the side. D. The ratio of concordant-to-discordant PWM hits for <SNP, TF> pairs for non-ASVs (red), all ASVs (yellow), ASVs overlapping with peaks (blue), and ASVs in TOPs (green). P-values: Fisher’s exact test. E. Left, Fraction of ASVs overlapping with PWM hits for four example TFs, using 4 different thresholds on ASV significance: all SNPs (blue), 25% FDR ASVs (yellow), 10% FDR ASVs (orange), and 5% FDR ASVs (red). Right, Fraction of ASVs at each location within the genome-wide PWM hits of the representative TFs using four thresholds (same colors as in bar plots).

Compared to whole-length peaks, TOP regions had an increased density of variant calls (~258 sufficiently covered variants per Mb in TOPs, versus 52 per Mb for peaks), and a larger fraction of ASB calls in SNVs (30%, compared to 9% for full peaks), presumably due to detection bias from higher ChIP-Seq or GHT-SELEX coverage at the TOPs. Nonetheless, variants in TOPs had a significantly higher predicted effect on protein binding (i.e. PWM score change) for both controls and Codebook TFs (p < 2.22×10−5 and p < 2.98×10−12, Mann-Whitney U test), relative to full peaks or non-ASB SNPs overlapping PWM hits (Figure 5B). Thus, the ASBs in TOPs are more likely to induce an effect than those elsewhere within peaks, presumably because they represent direct TF binding.

Among the mechanisms connecting TF binding to biological function are TF-mediated chromatin state changes. Hence, in heterozygotes, variant-dependent TF binding may co-occur with allele-specific chromatin accessibility variants (ASVs) (Figure 5A), which are SNVs with imbalanced read counts in ATAC-seq and/or DNase-seq experiments. To ask whether the Codebook TFs may be involved in control of ASVs, we utilized the UDACHA database, which contains ASVs from 577 ATAC-seq and 321 DNase-seq datasets from individual cell types68 (Table S9, Figure S5D). Using a multi-tiered procedure (see Methods), we identified cases in which (1) ASVs in a specific cell type overlap significantly with PWM hits for a TF in the Codebook motif collection, (2) the change in the PWM score is concordant with the read imbalance in the ASVs, (i.e. stronger predicted binding is associated with more accessible chromatin), and (3) the concordance is significant across cell types detected in step (1). This procedure identified 53 TFs whose PWM hits were found often at, and concordant with, ASVs (Figure S5E). Twenty of these TFs were positive controls including well-known pioneers or activators (such as SOX2, GABPA, or JUN/FOS-family TFs), while 33 were previously unexplored Codebook TFs, including ZNF70, GRHL3, MYPOP, SP140(L), and DMTF1. An example ASV for ZNF70, in a region upstream of the PTMS gene that is annotated with multiple ENCODE enhancer elements is shown in Figure 5C.

For 34 of these 53 TFs, there was at least one ASV-overlapping TOP site (the non-TOP sites may represent sites that are not bound in HEK293). To assess whether ASVs in PWM hits have a greater effect at TOP sites than in other regions, we first removed cases in which the TF does not appear to impact chromatin directly, by grouping the TFs into ASV-concordant (i.e. having overall concordance between ASVs and PWM hits in ChIP-seq or GHT-SELEX peaks; 18 TFs), and others (16 TFs). We separated the ASV-concordant group into Codebook and control TFs. For each of the groups, we then calculated the concordant-to-discordant ratio for loci that corresponded to PWM hits that are non-ASV for that TF, ASV, ASV in TF’s peaks, and ASV in TOPs, and observed an overall monotonic increase in concordance (Figure 5D). Thus, the highest-confidence Codebook TF binding sites for these TFs are those most likely to impact the chromatin state. Moreover, the fraction of ASVs within PWM hits also increased monotonously as the ASV confidence increased, and the ASVs preferably occur at binding site positions that are most important for the PWM score (Figure 5E, Figure S5F), further supporting relevance of the TF sequence preferences.

Overall, the Codebook motifs provide a valuable resource for SNV interpretation, including identification of mechanisms that underpin variation in chromatin and transcription.

Lessons from Codebook: prospects for a complete human TF motif collection

Codebook yielded several clear outcomes, and guidance for future efforts. The high success rate is particularly striking. We obtained motifs for 177 previously uncharacterized human TFs, a number larger than the entire TF repertoire for many eukaryotes69. The selected PWMs for most of these TFs are unique, and unlike any previous TF motif. Most are from C2H2-zf proteins, and most C2H2-zf proteins analyzed were successful. Thus, a majority of putative and uncharacterized human TFs are bona fide TFs, and not annotation errors. We envision that the data produced will be broadly and immediately useful for a variety of applications. Motifs (especially as PWMs) are a standard component of the computational genomics toolkit, due to their utility in a range of tasks ranging from identification of key regulatory factors to building and interpreting models of gene expression70–73. For example, differential binding of TFs to noncoding SNVs (Single Nucleotide Variants) is thought to be a major mechanism by which these variants contribute to phenotypic differences74, and the Codebook data therefore provide vital new information for the analysis of cis-regulatory variation.

A key technical demonstration of the Codebook project is that the simultaneous application of multiple experimental strategies and multiple motif-derivation and motif-scoring strategies was highly beneficial. No single experiment type or data analysis approach dominated all others, or was universally successful, although specific assays were more or less advantageous for different classes of proteins (as evident in Figure 1). For example, PBMs were uniquely successful with AT-hook proteins, while ChIP-seq and SELEX variants were most successful for C2H2-zf proteins. We caution that there are confounding variables limiting what conclusions can be drawn regarding the strengths and weaknesses of experimental platforms. The protein production and purification method can differentially impact success of specific DBD classes, even when the same assay is used, and the different assays we employed were tied to different affinity tags and expression systems. Data pre-processing (i.e. read filtering and background estimation) is an additional variable that we did not systematically explore, but is known to impact all of the assays used here.

As noted above, a subset of the Codebook TFs, as well as other poorly characterized TFs, have been analyzed by others since our study began. To evaluate the current scope of known human TF specificities, we surveyed JASPAR, HOCOMOCO, and Factorbook for PWMs for putative TFs that were not included in this study or not found among 177 Codebook successes. These databases reported PWMs for 107 proteins, 63 of which we had tested, and 44 were among the 95 putative TFs not included in our experiments. We manually curated these external PWMs, using procedures similar to those we applied to our own data, to assess whether they are likely to represent the bona fide specificity of the TF analyzed. Many of them were comprised of simple repeats (which are common artifacts in virtually all assays) or appeared to correspond to indirect binding and/or recruitment by other TFs in ChIP-seq (See Table S8 for annotations and classification, and Figure S1 for examples of nonspecific, concordant, and likely correct PWMs in the external datasets).

Based on this curation, 33 additional human TFs (i.e. beyond the 177 described here) have at least one plausible motif available in datasets that have been performed since our 2018 TF census1, leading to a total of 1,421 human TFs now with characterized sequence specificities (Figure 6 and Table S10). Altogether, only 175 proteins with conventional DBDs now lack known sequence specificity. Not all proteins with such domains are necessarily TFs; for example, one systematic trend we observed is that almost all 36 proteins we tested with only a single C2H2-zf domain failed in every assay (Figure 6). At the same time, however, new DBD classes continue to appear, such as the aforementioned BEN, CGGBP, Dachshund, and C-clamp. Some TFs may bind only to methylated DNA, and ongoing advances in the prediction of protein and protein-DNA structures45 have the potential to identify additional candidates for sequence-specific DNA binding. Thus, while completion of the objective to obtain a motif for every human TF now appears much closer, the list of likely human TFs continues to evolve.

Figure 6. Motif coverage of human TFs, by DBD family.

TFs are categorized into structural classes based on Lambert et al.1. See Table S10 for underlying information.

Many of the Codebook TFs are now among the best characterized human DNA-binding proteins in terms of their sequence specificity. As illustrated in the accompanying papers (Table S1), and consistent with previous benchmarking efforts18,32, validation across platforms can lead to very different conclusions regarding PWM reliability. Moreover, obtaining in vivo and in vitro binding to the genome facilitates disentanglement of direct and indirect binding, as well as the contribution of the cellular environment. Obtaining in vitro binding data to both genomic-sequence and random-sequence DNA can provide insight into the importance of local sequence context. Only a small handful of the 1,000+ previously characterized TFs have such a combination of data types. A much better perspective on human gene regulation and genome function and evolution could presumably be obtained from generation of such data for all human TFs.

METHODS

Plasmids and inserts.

Sequences and accompanying information are given in Table S3, and the relationships between constructs, samples, and experiments are compiled in the information provided online at codebook.ccbr.utoronto.ca. Briefly, we selected Codebook TFs (and their DNA-binding domains catalogued) from information accompanying Lambert 20181) and posted at https://humantfs.ccbr.utoronto.ca. Inserts named with an “-FL” suffix correspond to the full-length ORF of a representative isoform of the protein. Those with a “-DBD” suffix contain all of the predicted DBDs in the protein flanked by either 50 amino-acids, or up to the N or C-terminus of the protein. Those with a “-DBD1”, “-DBD2” or “-DBD3” suffix contain a subset of the DBDs present in the proteins; these were designed manually, mainly for large C2H2-zf arrays. Inserts were obtained as recoded synthetic ORFs (BioBasic, US) flanked by AscI and SbfI sites, and subcloned into up to three plasmids: (i) pTH13195, a tetracycline-inducible, N-terminal eGFP-tagged expression vector with FLiP-in recombinase sites10; (ii) pTH6838, a T7-promoter driven, N-terminal GST-tagged bacterial expression vector75, and (iii) pTH16500 (pF3A-ResEnz-egfp), an SP6-promoter driven, N-terminal eGFP-tagged bacterial expression vector, modified from pF3A–eGFP9 to contain the two restriction sites after the eGFP.

Protein production.

Each experiment used a protein expressed from one of the following systems: (a) FLiP-in HEK293 cells (catalog number: R78007), induced with Doxycycline for 24 hours, used for inserts in pTH13195; (b) PURExpress T7 recombinant IVT system (NEB Cat.#E6800L), for inserts in pTH6838; or (c) SP6-driven wheat germ extract-based IVT (Promega Cat#L3260), for inserts in pTH16500.

DNA binding assays.

We followed previously-described methods for ChIP-seq10, PBMs32, and SMiLE-seq9. Detailed descriptions of GHT-SELEX, HT-SELEX, ChIP-seq, and SMiLE-seq data collection and initial analysis are found in the accompanying papers (Table S1). For PBMs, we analyzed proteins on two different PBM arrays (HK and ME), with differing probe sequences76.

Data processing and motif derivation.

The accompanying paper17 describes motif derivation and evaluation in detail. Briefly, after initial data processing steps, we obtained a set of ‘true positive’ (likely bound) sequences for each individual experiment. (721 / 4,873) experiments were removed at this step, due to a low number of peaks, or other technical issues, as documented in Table S5). We then applied a suite of tools to a training subset of the data from each experiment, and tested the resulting motifs on a test subset of the data from the same experiment, and also on the independent data for the same TF (i.e. the test sets from all other experiments done for the same TF). We employed a binary classification regime for all experiments and all motifs, and scored the motifs by a variety of criteria such as the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) or the precision-recall curve (AUPRC).

Experiment evaluation by expert curation.

To gauge the success of individual experiments, we employed an “expert curation” workflow with an initial voting scheme in which a committee of annotators gauged whether individual experiments should be “approved”, i.e. included in subsequent analyses. All experiments were examined by at least three annotators. A subcommittee (AJ, IVK, and TRH) jointly resolved all cases of disagreement among initial annotators (~300 experiments), and then reviewed all approved experiments. Annotators had available an early version of the MEX portal (https://mex.autosome.org) containing results of all PWMs scored against all experiments, and were tasked with gauging whether the experiments yielded PWMs that were similar across experiments, or scored highly across experiments. Annotators also considered whether the motif was consistent with those for other members of their protein family (e.g. BHLHA9 yielded an E-box-like motif, CAnCTG), and/or similar between closely related paralogs (e.g. ZXDA, ZXDB, and ZXDC all yielded similar motifs). We also considered whether (and how many) “peaks” were obtained from ChIP-seq or GHT-SELEX, and whether these peaks were common to independent experiments (e.g. both ChIP-seq and GHT-SELEX). Annotators were further given a measure of similarity between Codebook PWMs and any PWMs in the public domain, as well as enrichment of known or suspected common contaminant motifs in any experiment.

Post-evaluation peak processing.

After identification of “approved” experiments, we re-derived peaks sets for ChIP-seq and GHT-SELEX experiments in order to obtain a single peak set for each TF, as described in the accompanying papers14,15. Briefly, for ChIP-seq we repeated the peak calling using MACS2 and experiment-specific background sets, using a procedure previously described10, then merged the peak sets for replicates of the same TF with BEDTools merge77 (see accompanying manuscript15: “ChIP peak replicate analysis and merging”). We derived GHT-SELEX peaks using a novel method that calculates enrichment of reads in each cycle, and treats different experiments as independent statistical samples in order to obtain a single enrichment coefficient per peak14.

Expert motif curation.

For this study, to identify a single representative PWM for each TF, we first compiled a set of highest-scoring candidate PWMs for each TF (as summarized above and elsewhere17, then ran additional tests with them, utilizing the reprocessed peak data, and manually evaluated the outputs. We first took the union of three sets of 20 PWMs for each TF: the 20 PWMs with the highest AUROC (as calculated elsewhere17) on (i) any approved ChIP-seq experiment for the given TF, (ii) any approved GHT-SELEX experiment for the given TF, and (iii) any approved HT-SELEX experiment for the given TF. These PWMs were selected regardless of the data set from which they were derived. We then reassessed these PWMs against ChIP-seq and GHT-SELEX data with two parallel methodologies. First, we recalculated AUROC for each of the candidate top PWMs on the merged, thresholded sets of ChIP-seq peaks (P < 10−10)15 using AffiMX28 to score each peak. We generated negative sets using BEDTools shuffle77 with the -noOverlapping option to create sets of random genomic regions with the same number of peaks, and the same peak width distribution as the corresponding ChIP peak sets. We used the same technique to calculate AUROC values for GHT-SELEX, with thresholded peak sets (using a “Kneedle”78 specificity value of 30 in the sorted enrichment values15). In parallel, we calculated the Jaccard index to measure the overlap between PWM hits (identified by MOODS79 with - p 0.001) vs. the ChIP-seq peaks, and GHT-SELEX peaks, as two separate measures. The overlap in each case was maximized by applying different thresholds on the peak sets and choosing the cutoff at which the Jaccard index was the highest14. We then applied expert curation (by a committee consisting of AJ, TRH, AF, KUL, RR, MA, and IY) to choose a single representative PWM with high performance on all compiled scores that, all else equal, also reflects reasonable expectation from the DBD class (including recognition-code predicted motifs, see accompanying manuscript14) and has high information content.

Motif degeneracy analysis.

We adjusted the information content (IC) of PWMs on a per-base-pair basis, with all locations boosted equally, by incrementally scaling weights (e.g. probabilities in the PWM) until the PWM reached an adjusted to an average IC of 1 bit per base pair. The script, “logo_rescale.pl”, is available at https://gitlab.sib.swiss/EPD/pwmscan.

Comparison to external peak sets and PWMs.

We downloaded comparison peak sets from GTRD60 and ENCODE (4.12.2023)59, for all Codebook TFs. We then divided this date into four categories corresponding to cell type: HEK293/HEK293T, HepG2, K562, and other cells. Then, for each combination of TF and cell type category, we selected a single peak set. We preferentially selected the peak sets from GTRD, because it contains systematically derived peak sets; we also note that GTRD contains the majority of ENCODE consortium experiments, together with many non-ENCODE experiments. When multiple experiments were available for a TF in a cell type category, we selected the experiment with higher counts. If multiple computational methods had been used to derive peak sets for the selected experiment, we chose the peak set using a preferential order MACS, GEM, SISSRS, PICS and PEAKZILLA. See Table S7 for identifiers and metadata of the reference datasets.

For PWM scoring, the external peak sets were used as downloaded, with the exception of peak sets that were generated with the GEM peak caller, which have a peak width of 1, and were therefore expanded 250 bases in both directions. For Codebook data, we used the merged and thresholded Codebook ChIP peak sets as in “Expert motif curation”. We generated negative peak sets for each ChIP-seq peak set using BEDTools shuffle77 with the -noOverlapping option to create sets of random genomic regions with the same number of peaks and the same peak width distribution as the corresponding ChIP peak sets. We downloaded PWMs for all Codebook TFs from JASPAR80 (2024 version), HOCOMOCO13 (Version 12) and Factorbook12 (downloaded 15.12.2023). We scanned Codebook and external peak sets (and corresponding negative sets) with the expert curated Codebook motifs as PWMs using AffiMX28, and calculated AUROC values. Additionally, for the 19 Codebook TFs with a successful Codebook ChIP-seq experiment, a Codebook PWM, an external ChIP-seq experiment, and an external PWM, we compared the performance of PWMs across the different peak sets as follows. We first selected a single external PWM for each of the 19 TFs by scanning each PWM for a given TF on each external peak set for the same TF and identifying the PWM that produced the highest AUROC. We then used these highest scoring PWMs to scan the corresponding Codebook data and calculate AUROC values.

TOP (Triple Overlap) and CTOP (Conserved Triple Overlap) peak set analyses.

To obtain TOP sites, we first identified thresholds for ChIP-seq peaks, GHT-SELEX peaks, and PWM score “peaks” that maximize the three-way Jaccard metric (overlap/union) of the three sets, with the thresholds calculated for each TF independently. We converted PWM hits (derived from MOODS79 using a p-value cut-off of 0.001) into peaks by merging neighboring matches with a distance less than 200bp and re-scoring them using the sum-of-affinities for clusters. We then identified TOPs were as peaks exceeding these thresholds in all three sets, and overlap in all three sets. To obtain CTOP sites, we then extracted PhyloP scores for each base at each TOP site (and 100 flanking bases) from the Zoonomia consortium81, removed sites overlapping the ENCODE Blacklist82 or protein coding sequences (due to the skew in phyloP scores caused by codons), and applied three different statistical tests for significance of phyloP scores over the PWM hit: two that test correlation between the IC and the phyloP value at each base position of the PWM (using either Pearson correlation or linear regression), and one that tests for higher phyloP scores over the PWM hit (Wilcoxon test). Greater detail on these specific operations is given in the accompanying manuscripts14,15.

Intersection of TOPs/CTOPs and genomic features.

We first clustered all CTOPs using BEDTools merge77, with a max distance of 100 bp, then intersected with the following genomic feature sets: basic canonical protein coding promoters from GENCODE version 4483, defined as 1000 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the canonical TSS; the “Unmasked CpG Island” track, PhastCons Conserved Elements from the Multiz 470 Mammalian alignment, and RepeatMasker track from UCSC84; ChromHMM HEK293 enhancers15. We classified promoters as CpG island or non-CpG island based on the GENCODE basic TSS being within +/− 50 bp of a CpG island from the unmasked track. We classified the CTOP clusters as associated with a single type of genomic feature in the following order of priority: CpG island associated with a protein coding promoter; other CpG islands; a non-CpG island-associated protein-coding promoter; an enhancer; containing a CTCF binding site but not overlapping a CpG island, promoter or enhancer; overlapping a transposable element and none of the previous categories; overlapping a non-TE repeat and none of the prior categories; and “Other” for CTOP clusters not intersecting any examined features.

SNV analyses.

TOPs and CTOPs. For analysis of common variants, we intersected TOPs with the common short variants from dbSNP version 53, defined as a minor allele frequency of >= 1% in the 1000 Genomes project85. We determined genomic overlap enrichment between CTOPs/unconserved TOPs and dbSNP variants using the Fisher’s Exact Test implemented in BEDTools77.

Variant calling for allele-specific binding analysis.

We performed variant calling on our GHT-SELEX and ChIP-seq datasets by mapping raw ChIP-Seq and pre-trimmed GHT-SELEX reads17 for 207 TFs to the hg38 human genome assembly using bwa-mem (v.0.7.1) with default settings (workflow is shown in Figure S5A). Next, we used filter_reads.py from stampipes (https://github.com/StamLab/stampipes/tree/encode-release/, accessed Sept 2022) to filter out reads with >2 mismatches and mapping quality <10. Then, we used a previously-described approach86 for SNV calling and read counting: (1) samtools reheader (v.1.16.1) was used to set the identical sample SM field in all alignment files; (2) SNP calling was performed using bcftools mpileup (v.1.10.2) with --redo-BAQ --adjust-MQ 50 --gap-frac 0.05 --max-depth 10000 and bcftools call with --keep-alts --multiallelic-caller; (3) the resulting SNPs were split into biallelic records using bcftools norm with --check-ref x -m - followed by filtering with bcftools filter -i “QUAL>=10 & FORMAT/GQ>=20 & FORMAT/DP>=10” --SnpGap 3 --IndelGap 10 and bcftools view -m2 -M2 -v snps leaving only biallelic SNPs covered by 10 or more reads; (4) SNPs were annotated using bcftools annotate with --columns ID,CAF,TOPMED and dbSNP (v.151)87 (5) heterozygous variants located on the reference chromosomes with GQ ≥20, depth ≥10, and allelic counts ≥5 on each allele were filtered with awk (v.5.0.1), (6) WASP (v.0.3.4)88 was used with bwa mem and filter_reads.py to account for reference mapping bias, (7) count_tags_pileup_new.py was used to obtain allelic read counts with pysam (v.0.20.0), (8) recode_vcf.py was used to convert the resulting BED files to VCF. In total, we made 925,003 candidate variant calls supported by five reads for both alleles and listed in the dbSNP common subset87.

ASB calling and analysis.

ASB calling was performed independently for GHT-SELEX and ChIP-seq data. To account for aneuploidy and copy-number variation, the profiles of relative background allelic dosage were reconstructed with BABACHI (v.2.0.26) using default settings (89, Abstract O3). The allelic imbalance was estimated with MIXALIME (v.2.14.7)68 starting with mixalime create. Next, we fitted a marginalized compound negative binomial model (MCNB) using mixalime fit specifying MCNB and setting -- window-size to 1000 and 10000 for GHT-SELEX and ChIP-Seq, respectively, taking into account lower coverage and SNP counts in GHT-SELEX. Finally, we used mixalime test followed by TF-wise mixalime combine to obtain the TF-specific ASB calls (Figure S5A).

We then identified ASBs that overlap a PWM hit (P-value < 0.001) for the associated TF. For those ASBs, we calculated the PWM score for both alleles and estimated the P-value of those scores against a uniform background distribution for each allele using PERFECTOS-APE90. The fold-change between allele P-values (P1/P2) was then calculated with the P-value of the more abundant allele as the numerator. ASBs with a log2(fold-change) >=1 were labelled “strongly concordant”, i.e., the allele we observed to be bound more often is consistent with the PWM score (Figure S5B).

To assess the enrichment of Codebook ASBs within GTEx eQTLs67 and ADASTRA ASBs66 we combined the ASB P-values from ChIP-Seq and GHT-SELEX data across all TFs and datasets (logitp method91) to generate a single P-value for each TF (Figure S5C).

Analysis of allele-specific chromatin accessibility.

In this analysis, we relied on 321 and 577 cell type-specific chromatin accessibility datasets derived from DNase- and ATAC-Seq experiments, respectively, and available in the UDACHA database (Release IceKing 1.0.3)68. We identified 4,048 instances in which ASVs in a specific cell type overlap significantly with PWM hits (P<0.0005) for a TF in the Codebook motif collection (236 PWMs) (Right-tailed Fisher’s exact test P < 0.05, and requiring 10 or more overlapping PWM hits) (Figure S5D). Then, for each ASV in each combination of TF and cell type passing the PWM enrichment filter, we asked whether the change in the PWM score is concordant with the read imbalance in the ASVs, e.g. whether a higher PWM score at a given locus corresponds to a higher read count, and we assigned a P-value for each combination of TF and cell type, using a right-tailed Fisher’s exact test, including only sites with at least two-fold change in PWM-predicted affinity. Finally, to obtain a single significance estimate per TF, we combined these P-values for each TF across the different cell types passing the first stage, i.e. for which the overlap between PWM hits and ASVs is significant (Fisher’s method, considering DNase-Seq and ATAC-Seq data separately and FDR-adjusted). TFs passing FDR < 0.05 in the final stage were considered ASV-concordant.

To further verify the concordance between ASVs and Codebook motifs, we selected 34 (out of 53 TFs) with at least one TOP region overlapping ASVs, and re-evaluated the concordant-to-discordant ratio for ASVs within peaks and TOP regions (see Results and Figure 5C). For this analysis, for each TF, we picked the most significant ASV at each unique genomic position (SNP) from all available cell types, and performed a right-tailed Fisher’s Exact Test (Table S9). At this stage, we considered SP140 and SP140L jointly they share short and highly similar DNA-binding motifs.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Accompanying manuscripts. Table lists the 5 studies performed by the Codebook Consortium, providing basic information for each of the manuscripts, including title and author list.

Table S2. TF list and assay success. Table lists the Codebook proteins and positive control TFs that were analyzed in the Codebook studies and provides metadata and information on whether they showed sequence-specific DNA binding activities in different types of experiments, together with the ID of the representative PWM selected in this study, if any.

Table S3. List of inserts used in this study. Table provides the amino acid sequence and type (full-length or DBD) for the 716 inserts used in the Codebook studies.

Table S4. List of plasmids used in this study. Table lists the plasmid backbone and insert for each of the 1,387 plasmids used in the Codebook studies.

Table S5. List of experiments performed in this study. Table lists the 4,873 experiments performed on Codebook and control TFs, along with 20 additional GFP control experiments. The experiment ID, experiment type, TF assayed, expert curation result, and plasmid ID are listed for each experiment. Each experiment is mapped to its ID in an accompanying manuscript17, and 9 additional experiments used only in an accompanying manuscript17 are listed.

Table S6. Representative PWMs. Table shows logo representations for the PWMs that were selected as the representative for each of the TFs (i.e. the expert-curated motifs) and provides metadata describing the role of the TF in the study, DBD that it belongs to, source of the experimental data and motif derivation approach.

Table S7. External peak datasets. Table lists external peak location datasets obtained from GTRD database and ENCODE consortium, that were used in the comparisons carried out in this study.

Table S8. External PWM datasets. Table lists PWM identifiers, manual curation and other metadata for external motifs available from the databases Jaspar, HOCOMOCO and Factorbook.

Table S9. ASE and ASV data. Allele-specific binding sites detected in Codebook data and motif annotation of allele-specific chromatin accessibility events.

Table S10. Updated census of human transcription factors and their motif coverage. Table is modified from Lambert et al. to display an updated motif coverage of human TFs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the IT Group of the Institute of Computer Science at Halle University for computational resources, Maximilian Biermann for valuable technical support, Gherman Novakovsky for providing feedback, Berat Dogan for testing earlier versions of RCADEEM, and Debashish Ray for assistance with database depositions.

This work was supported by the following:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grants FDN-148403, PJT-186136, PJT-191768, and PJT-191802, and NIH grant R21HG012258 to T.R.H

CIHR grant PJT-191802 to T.R.H. and H.S.N.

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant RGPIN-2018–05962 to H.S.N.

A Russian Science Foundation grant [20–74-10075] to I.V.K.

A Swiss National Science Foundation grant (no. 310030_197082) to B.D.

Marie Skłodowska-Curie (no. 895426) and EMBO long-term (1139–2019) fellowships to J.F.K.

NIH grants R01HG013328 and U24HG013078 to M.T.W., T.R.H., and Q.D.M.

NIH grants R01AR073228, P30AR070549, and R01AI173314 to M.T.W.

NIH grant P30CA008748 partially supported Q.M.

Canada Research Chairs funded by CIHR to T.R.H. and H.S.N.

Ontario Graduate Scholarships to K.U.L and I.Y.

A.J. was supported by Vetenskapsrådet (Swedish Research Council) Postdoctoral Fellowship (2016–00158)

The Billes Chair of Medical Research at the University of Toronto to T.R.H.

EPFL’s Center for Imaging

Resource allocations from Digital Research Alliance of Canada

The Codebook Consortium

Principal investigators (steering committee)

Philipp Bucher, Bart Deplancke, Oriol Fornes, Jan Grau, Ivo Grosse, Timothy R. Hughes, Arttu Jolma, Fedor A. Kolpakov, Ivan V. Kulakovskiy, Vsevolod J. Makeev

Analysis Centers:

University of Toronto (Data production and analysis): Mihai Albu, Marjan Barazandeh, Alexander Brechalov, Zhenfeng Deng, Ali Fathi, Arttu Jolma, Chun Hu, Timothy R. Hughes, Samuel A. Lambert, Kaitlin U. Laverty, Zain M. Patel, Sara E. Pour, Rozita Razavi, Mikhail Salnikov, Ally W.H. Yang, Isaac Yellan, Hong Zheng

Institute of Protein Research (Data analysis): Ivan V. Kulakovskiy, Georgy Meshcheryakov

EPFL, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (Data production and analysis): Giovanna Ambrosini, Bart Deplancke, Antoni J. Gralak, Sachi Inukai, Judith F. Kribelbauer-Swietek

Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (Data analysis): Jan Grau, Ivo Grosse, Marie-Luise Plescher

Sirius University of Science and Technology (Data analysis): Semyon Kolmykov, Fedor Kolpakov

Biosoft.Ru (Data analysis): Ivan Yevshin

Faculty of Bioengineering and Bioinformatics, Lomonosov Moscow State University (Data analysis): Nikita Gryzunov, Ivan Kozin, Mikhail Nikonov, Vladimir Nozdrin, Arsenii Zinkevich

Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry (Data analysis): Katerina Faltejskova

Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry (Data analysis): Pavel Kravchenko

Swiss Institute for Bioinformatics (Data analysis): Philipp Bucher

University of British Columbia (Data analysis): Oriol Fornes

Vavilov Institute of General Genetics (Data analysis): Sergey Abramov, Alexandr Boytsov, Vasilii Kamenets, Vsevolod J. Makeev, Dmitry Penzar, Anton Vlasov, Ilya E. Vorontsov

McGill University (Data analysis): Aldo Hernandez-Corchado, Hamed S. Najafabadi

Memorial Sloan Kettering (Data production and analysis): Kaitlin U. Laverty, Quaid Morris

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (Data analysis): Xiaoting Chen, Matthew T. Weirauch

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTERESTS

O.F. is employed by Roche.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The sequencing raw data for the HT-SELEX and GHT-SELEX experiments have been deposited into the SRA database under identifiers PRJEB78913 (ChIP-seq), PRJEB76622 (GHT-SELEX), and PRJEB61115 (HT-SELEX). Genomic interval information generated for the GHT-SELEX and ChIP-seq have been deposited into GEO under accessions GSE280248 (ChIP-seq) and GSE278858 (GHT-SELEX). PWMs can be browsed at https://mex.autosome.org and downloaded at https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8327372. An updated list of human TFs is available at https://humantfs.ccbr.utoronto.ca. Information on constructs, experiments, analyses, processed data, comparison tracks, and browsable pages with information and results for each TF is available at https://codebook.ccbr.utoronto.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambert S.A. et al. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 175, 598–599 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stormo G.D. & Zhao Y. Determining the specificity of protein-DNA interactions. Nat Rev Genet 11, 751–60 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stormo G.D. Consensus patterns in DNA. Methods Enzymol 183, 211–21 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider T.D. & Stephens R.M. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 18, 6097–100 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benos P.V., Bulyk M.L. & Stormo G.D. Additivity in protein-DNA interactions: how good an approximation is it? Nucleic Acids Res 30, 4442–51 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan J. et al. Systematic analysis of binding of transcription factors to noncoding variants. Nature 591, 147–151 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasserman W.W. & Sandelin A. Applied bioinformatics for the identification of regulatory elements. Nat Rev Genet 5, 276–87 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava D. & Mahony S. Sequence and chromatin determinants of transcription factor binding and the establishment of cell type-specific binding patterns. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1863, 194443 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isakova A. et al. SMiLE-seq identifies binding motifs of single and dimeric transcription factors. Nat Methods 14, 316–322 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitges F.W. et al. Multiparameter functional diversity of human C2H2 zinc finger proteins. Genome Res 26, 1742–1752 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consortium E.P. et al. Perspectives on ENCODE. Nature 583, 693–698 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratt H.E. et al. Factorbook: an updated catalog of transcription factor motifs and candidate regulatory motif sites. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D141–D149 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vorontsov I.E. et al. HOCOMOCO in 2024: a rebuild of the curated collection of binding models for human and mouse transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res 52, D154–D163 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolma A. et al. GHT-SELEX demonstrates unexpectedly high intrinsic sequence specificity and complex DNA binding of many human transcription factors. bioRxiv, 2024.11.11.618478 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razavi R. et al. Extensive binding of uncharacterized human transcription factors to genomic dark matter. bioRxiv, 2024.11.11.622123 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gralak A. et al. Identification of methylation-sensitive human transcription factors using meSMiLE-seq. bioRxiv, 2024.11.11.619598 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vorontsov I.E. et al. Cross-platform DNA motif discovery and benchmarking to explore binding specificities of poorly studied human transcription factors. bioRxiv, 2024.11.11.619379 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambrosini G. et al. Insights gained from a comprehensive all-against-all transcription factor binding motif benchmarking study. Genome Biol 21, 114 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey T.L., Johnson J., Grant C.E. & Noble W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res 43, W39–49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novakovsky G., Fornes O., Saraswat M., Mostafavi S. & Wasserman W.W. ExplaiNN: interpretable and transparent neural networks for genomics. Genome Biol 24, 154 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rube H.T. et al. Prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity from sequencing data with interpretable machine learning. Nat Biotechnol (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe S.A., Nekludova L. & Pabo C.O. DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 29, 183–212 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brayer K.J., Kulshreshtha S. & Segal D.J. The protein-binding potential of C2H2 zinc finger domains. Cell Biochem Biophys 51, 9–19 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bird A.J., Gordon M., Eide D.J. & Winge D.R. Repression of ADH1 and ADH3 during zinc deficiency by Zap1-induced intergenic RNA transcripts. EMBO J 25, 5726–34 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Font J. & Mackay J.P. Beyond DNA: zinc finger domains as RNA-binding modules. Methods Mol Biol 649, 479–91 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stros M., Launholt D. & Grasser K.D. The HMG-box: a versatile protein domain occurring in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci 64, 2590–606 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Najafabadi H.S. et al. C2H2 zinc finger proteins greatly expand the human regulatory lexicon. Nat Biotechnol (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert S.A., Albu M., Hughes T.R. & Najafabadi H.S. Motif comparison based on similarity of binding affinity profiles. Bioinformatics 32, 3504–3506 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emerson R.O. & Thomas J.H. Adaptive evolution in zinc finger transcription factors. PLoS Genet 5, e1000325 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y. & Stormo G.D. Quantitative analysis demonstrates most transcription factors require only simple models of specificity. Nat Biotechnol 29, 480–3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruan S., Swamidass S.J. & Stormo G.D. BEESEM: estimation of binding energy models using HT-SELEX data. Bioinformatics 33, 2288–2295 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weirauch M.T. et al. Evaluation of methods for modeling transcription factor sequence specificity. Nat Biotechnol 31, 126–34 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuznetsov V.A. Mathematical Modeling of Avidity Distribution and Estimating General Binding Properties of Transcription Factors from Genome-Wide Binding Profiles. Methods Mol Biol 1613, 193–276 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horton C.A. et al. Short tandem repeats bind transcription factors to tune eukaryotic gene expression. Science 381, eadd1250 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgunova E. et al. Two distinct DNA sequences recognized by transcription factors represent enthalpy and entropy optima. Elife 7(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siggers T. & Gordan R. Protein-DNA binding: complexities and multi-protein codes. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 2099–111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]