Abstract

The use of orthologous sequences and phylogenetic footprinting approaches have become popular for the recognition of conserved and potentially functional sequences. Several algorithms have been developed for the identification of conserved transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs), which are characterized by their relatively short and degenerative recognition sequences. The CONREAL (conserved regulatory elements anchored alignment) web server provides a versatile interface to CONREAL-, LAGAN-, BLASTZ- and AVID-based predictions of conserved TFBSs in orthologous promoters. Comparative analysis using different algorithms can be started by keyword without any prior sequence retrieval. The interface is available at http://conreal.niob.knaw.nl.

INTRODUCTION

Tight regulation of gene activity at the transcriptional level plays a crucial role in orchestrating developmental processes, but control of gene expression is also important for the maintenance of the homeostatic situation or for the induction of the adaptive processes that are needed to anticipate on environmental changes. Although changes in gene expression levels can now routinely be monitored on a genome-wide scale using microarray analysis, the molecular mechanisms and the specific transcription factors (TFs) that drive specific changes remain largely unknown. According to Gene Ontology annotations, the human genome contains more than 800 TFs, which have been characterized to varying degrees. For many of them, information on DNA-binding sites is available and although most of this information is obtained using in vitro assays and only verified in independent assays in a limited number of cases, the major bottleneck for the use of transcription factor binding site (TFBS) profiles is that they are very short, often between 6 and 10 nt, and allow relatively high degrees of degeneracy in the sequence. As a result, most TFBSs can be found in every randomly picked genomic segment of several thousands of bases, making predictions on the TFs, which can bind specific promoter regions and might regulate the expression of a gene, very difficult.

The use of orthologous sequences may help in the recognition of conserved and, therefore, potentially functional sequences. Although gene-coding sequences are readily identified by their overall high degree of conservation, the identification of short regulatory elements usually requires a special approach, especially at the level of the initial alignment of orthologous sequences. There is an important drawback to the use of the traditional local alignment programs, such as BLAST and FASTA, as these programs cannot deal very well with relatively long sequences with a high degree of divergence. To this end, several global alignment algorithms, such as LAGAN and AVID (1–3), and modified local aligners, such as BLASTZ (4), have been developed that aim for the best pairwise alignment of long sequences up to complete genomes. When applied to promoter regions, highly conserved elements can be revealed that can be queried for the presence of potential TFBSs. However, correct alignment of binding sites with degenerated sequence of only 6–10 nt is still challenging for global alignment algorithms and may be easily missed, especially when using orthologous sequences from more diverged species. We have developed an alternative algorithm, CONREAL (conserved regulatory elements anchored alignment) that does not depend on prior alignment of orthologous promoter sequences (5). First, all potential TFBSs are determined independently for each orthologous promoter using TFBS matrices (6). Next, binding sites for the same TFs are anchored between the orthologous promoters, starting with the binding sites with the highest score and assuming colinear conservation of binding sites. We show that this algorithm performs just as well as other approaches that depend on prior alignment, when applied to closely related species, such as human, mouse and rat, but is more useful for aligning promoter elements of more diverged species, such as human and Fugu, since it identifies conserved TFBSs that are not found by other methods (5).

Although we observed a major overlap in the predictions by different algorithms, the algorithm-specific sets of predicted sites are still significant. However, it is extremely difficult to conclude which approach performs best, owing to the lack of sufficient validated experimental data, and therefore we feel that it is important to include and compare different approaches for TFBS prediction. Although this may not be very practical when analysing genome-wide regulatory networks, the analysis of individual promoters of, for example, one's specific gene of interest may benefit from such an approach.

To this end, we have developed a user-friendly web-interface to our CONREAL algorithm, with the option to include the LAGAN-, BLASTZ- and AVID-based algorithms, to identify and visualize conserved TFBSs in orthologous promoters of interest.

IMPLEMENTATION

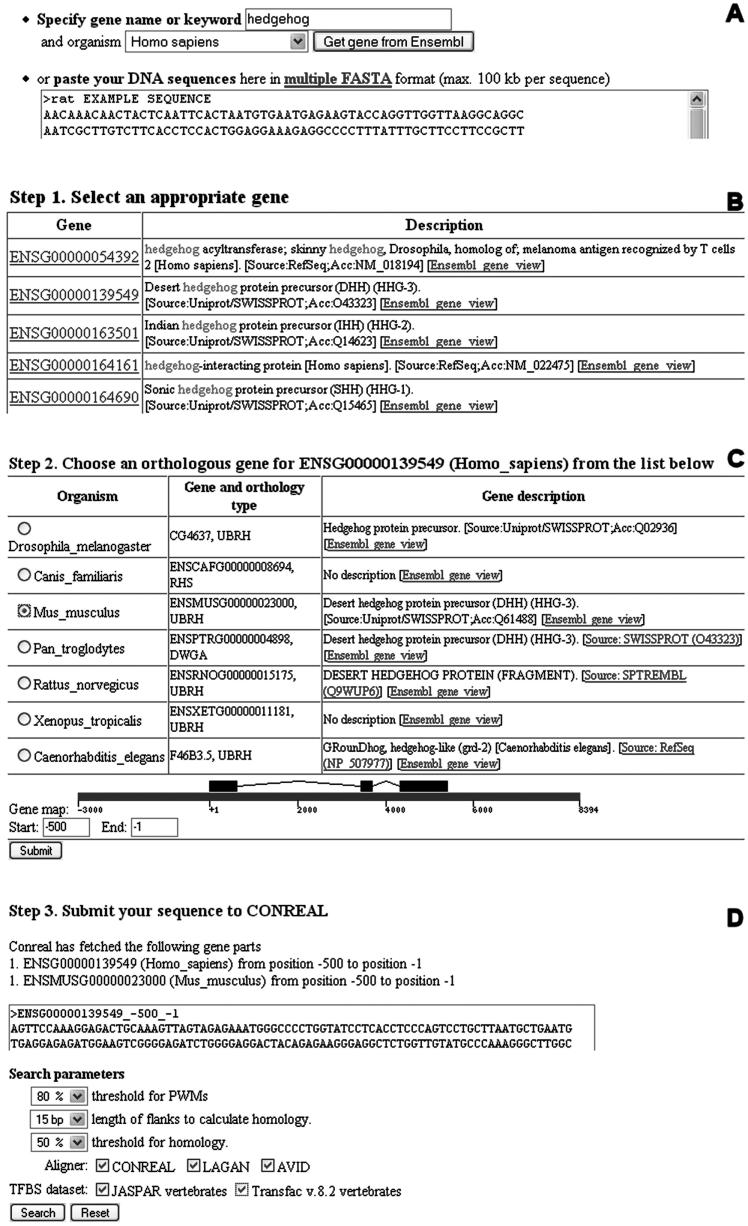

CONREAL web server requires as input a pair of orthologous sequences that can be either provided by a user or generated by the server through a three-step process. In the latter case, a user starts by providing a keyword or gene name (Figure 1A). A list of genes from the Ensembl genome database (7) matching the query for the selected species will be returned, including gene description annotation and links to the Ensembl database for additional information (Figure 1B). When a gene from the first species is selected, a list of orthologous Ensembl genes becomes available for selection of the sequence from the second species for pairwise analysis. At this point, graphical representation of a gene structure is provided in gene coordinates, and the region of interest can be selected by specifying the range of the coordinates (Figure 1C). After all the necessary information is gathered, sequences are retrieved from Ensembl database and forwarded to the CONREAL submission page, where parameters for the analysis can be specified (Figure 1D). There are three parameters that can be set: (i) threshold for position-weight matrices (PWMs) that reflects how similar a PWM and a site could be; (ii) length of sequences flanking TFBS to include for the calculation of identity between a pair of sites; and (iii) threshold for percentage of identity in a pair of sites to be included in a final report. In addition, it is possible to specify one or multiple alignment methods to be used (CONREAL, LAGAN, BLASTZ and MAVID) and a source of PWMs. CONREAL web server uses 81 ‘vertebrate’ matrices from JASPAR database of curated profiles (8) and 546 matrices from TRANSFAC database (6).

Figure 1.

Input: CONREAL orthologous sequence retrieval and submission page view. See text for details.

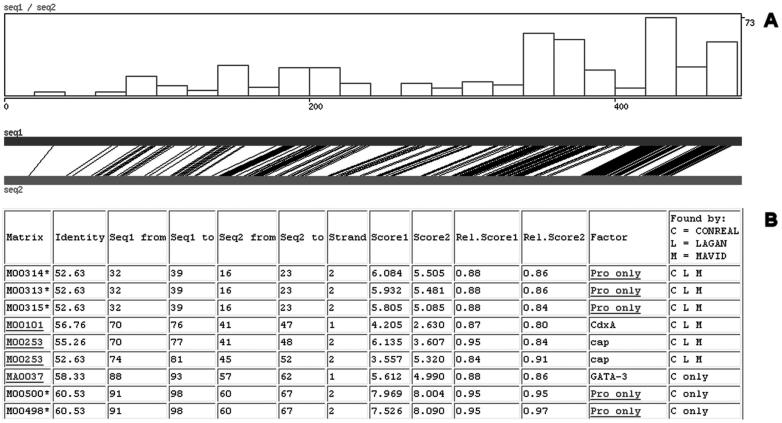

Computations are performed in parallel on a Linux cluster, allowing analysis of long sequences (up to 20 kb) within a relatively short period of time (1–2 min). Results are visualized graphically showing aligned positions in the orthologous sequences and the density of predicted TFBS (Figure 2A). In addition, a pairwise alignment of sequences provides single nucleotide resolution information (data not shown), and a table with predicted conserved TFBS, sorted by position in the alignment and linked to JASPAR and TRANSFAC databases, supplies more detailed information on the TFs (Figure 2B). Furthermore, when multiple algorithms were selected for analysis, the overlap between predictions by different algorithms is shown for every TFBS (Figure 2B, last column).

Figure 2.

Output: representation of predicted conserved TFBS. See text for details.

CONCLUSIONS

CONREAL web server allows prediction of conserved TFBSs in orthologous sequences. Although similar web services exist, e.g. ConSite (9) or rVista (10), the unique feature of CONREAL web server is that predictions can be performed by three different methods and compared with each other. This approach allows better interrogation of the region of interest, particularly when highly diverged sequences are analysed. Additionally, a convenient interface for the retrieval of orthologous sequences from Ensembl database is provided, improving accessibility for general usage without the need to go through laborious sequence retrieval processes that may need relatively advanced skills. The retrieval process is semiautomatic and relies on Ensembl annotations of gene boundaries. The graphical visualization of the resulting alignments facilitates recognition of incorrect gene annotations (e.g. first exon missing in one of the species) and may help in defining the correct regions for reanalysis. The current version allows analysis of sequences up to 10–20 kb in a single run. However, distant regulatory elements may be as far away as 1–10 Mb and will be missed using this approach, but there is currently no good alternative computational approach to reliably identify such sequences.

Taken together, the CONREAL web server is a versatile tool that assists in the analysis of transcriptional regulation on a gene-to-gene basis, which may be useful for many different applications and research areas.

Acknowledgments

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Hubrecht Laboratory.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brudno M., Do C.B., Cooper G.M., Kim M.F., Davydov E., Green E.D., Sidow A., Batzoglou S. LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: efficient tools for large-scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 2003;13:721–731. doi: 10.1101/gr.926603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray N., Dubchak I., Pachter L. AVID: a global alignment program. Genome Res. 2003;13:97–102. doi: 10.1101/gr.789803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray N., Pachter L. MAVID: constrained ancestral alignment of multiple sequences. Genome Res. 2004;14:693–699. doi: 10.1101/gr.1960404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz S., Kent W.J., Smit A., Zhang Z., Baertsch R., Hardison R.C., Haussler D., Miller W. Human–mouse alignments with BLASTZ. Genome Res. 2003;13:103–107. doi: 10.1101/gr.809403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berezikov E., Guryev V., Plasterk R.H., Cuppen E. CONREAL: conserved regulatory elements anchored alignment algorithm for identification of transcription factor binding sites by phylogenetic footprinting. Genome Res. 2004;14:170–178. doi: 10.1101/gr.1642804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matys V., Fricke E., Geffers R., Gossling E., Haubrock M., Hehl R., Hornischer K., Karas D., Kel A.E., Kel-Margoulis O.V., et al. TRANSFAC: transcriptional regulation, from patterns to profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:374–378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbard T., Andrews D., Caccamo M., Cameron G., Chen Y., Clamp M., Clarke L., Coates G., Cox T., Cunningham F., et al. Ensembl 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D447–D553. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandelin A., Alkema W., Engstrom P., Wasserman W.W., Lenhard B. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D91–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandelin A., Wasserman W.W., Lenhard B. ConSite: web-based prediction of regulatory elements using cross-species comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W249–W252. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loots G.G., Ovcharenko I. rVISTA 2.0: evolutionary analysis of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W217–W221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]