Summary

The disproportionate expansion of telencephalic structures during human evolution involved tradeoffs that imposed greater connectivity and metabolic demands on midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Despite the central role of dopaminergic neurons in human-enriched disorders, molecular specializations associated with human-specific features and vulnerabilities of the dopaminergic system remain unexplored. Here, we establish a phylogeny-in-a-dish approach to examine gene regulatory evolution by differentiating pools of human, chimpanzee, orangutan, and macaque pluripotent stem cells into ventral midbrain organoids capable of forming long-range projections, spontaneous activity, and dopamine release. We identify human-specific gene expression changes related to axonal transport of mitochondria and reactive oxygen species buffering and candidate cis- and trans-regulatory mechanisms underlying gene expression divergence. Our findings are consistent with a model of evolved neuroprotection in response to tradeoffs related to brain expansion and could contribute to the discovery of therapeutic targets and strategies for treating disorders involving the dopaminergic system.

Keywords: Brain evolution, dopaminergic, midbrain, organoids, Parkinson’s disease, iPSCs, oxidative stress, single cell genomics

Introduction

Midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neurons coordinate multiple aspects of cortical- and subcortical functions and regulate motor control, as well as recently evolved human cognitive and social behaviors1. Dysregulation and degeneration of these neurons are major drivers in various disorders that are unique or enriched in humans, including schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease (PD)2,3, but the origins of human-specific developmental trajectories and vulnerabilities remain poorly understood.

Evolutionary tradeoffs may contribute to the increased connectivity requirements and vulnerabilities of human DA neurons4,5. The evolutionary expansion of the human brain disproportionately increased the size of DA target regions in cortex and striatum compared to source regions in the ventral midbrain1,4,6–9. In total, 400,000 DA neurons in substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area must supply dopamine to expanded human forebrain structures, with each human midbrain DA neuron predicted to form over 2 million synapses1,10,11. In addition, the density of DA afferents in basal ganglia has also increased in humans compared to chimpanzees12,13, and great ape axons show more complex morphology and altered cortical target distribution14. One recent model suggests that the evolution of cooperative behaviors in humans required increased DA innervation in the medial caudate and nucleus accumbens12,15. Thus, the human DA system may be under pressure both to adapt to innervating a large forebrain and to regulating evolutionarily novel behaviors.

DA neurons are under intense mitochondrial and bioenergetic demands, which are thought to contribute to their selective vulnerability to degeneration in PD16,17. Midbrain DA neurons are unmyelinated, long-projecting, highly arborized cells that release dopamine, the production of which generates toxic reactive oxygen species byproducts18,19. Pacemaker activity through L-type calcium channels further increases the energetic demands on DA neurons as a high cytosolic concentration of calcium requires additional ATP for extrusion and can lead to mitochondrial damage20–22. Several pathways have been proposed as protective in DA neurons, including cell-intrinsic buffering of free radicals and calcium23,24. We hypothesize that the utilization of these or other protective mechanisms could have increased in human neurons compared to other primates, as compensatory adaptations in response to increased DA connectivity requirements.

In this study, we established a phylogeny-in-a-dish approach, generating interspecies ventral midbrain cultures of human, chimpanzee, orangutan and macaque cell lines, and performed combined single nucleus (sn)RNA sequencing and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC) sequencing during midbrain progenitor specification in 2D cultures (day 16) and maturation in organoids (day 40–100). Although developing tissue from apes is inaccessible for ethical reasons, these pluripotent stem cell (PSC)-based approaches enable comparative developmental studies and isolation of cell-intrinsic species differences25,26. By comparing homologous cell types across primate species, we discover increased expression in the human lineage of genes related to axonal transport of mitochondria and reactive oxygen species buffering, candidate cis-regulatory mechanisms enriched in noncoding structural variants, and trans-regulatory mechanisms involving gene networks driven by DA lineage-enriched transcription factors (TFs) OTX2, PBX1, and ZFHX3. Subjecting interspecies organoids to rotenone-induced oxidative stress27,28 unmasked human-specific responses, consistent with a model of increased neuroprotective mechanisms in human DA neurons. Together, these findings provide a comparative multiomic atlas of primate ventral midbrain differentiation and implicate candidate molecular pathways supporting DA neuron specializations in the enlarged human brain.

Results

PSC-derived interspecies cultures model primate ventral midbrain specification and development

We first considered species differences in neuroanatomical scaling influencing the cellular environment of DA neurons. While stereological surveys provide an account of species difference in DA neuron number8,9, we further applied a standardized approach to quantify differences in target region volume and axon tract length across multiple adult human and macaque individuals. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an 18-fold expansion of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and a 6.8-fold expansion of striatum target region volumes in humans (Figures 1A, 1B and Table S1). Similarly, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), indicated a 2.5 fold increase in fiber tract length from DA nucleus substantia nigra to the caudate (Figures S1A and S1B). Although DTI cannot quantify differences in axonal arborization that represents the majority of axon length, these results further support the increased connectivity requirements of midbrain DA neurons throughout the extended human lifespan (Figure 1C) in the expanded human brain. The DA innervation densities in these target structures have been carefully investigated in previous studies12,13, that have shown a human-specific increase in DA innervation density in parts of the basal ganglia which should further exacerbate the burden on human DA neurons.

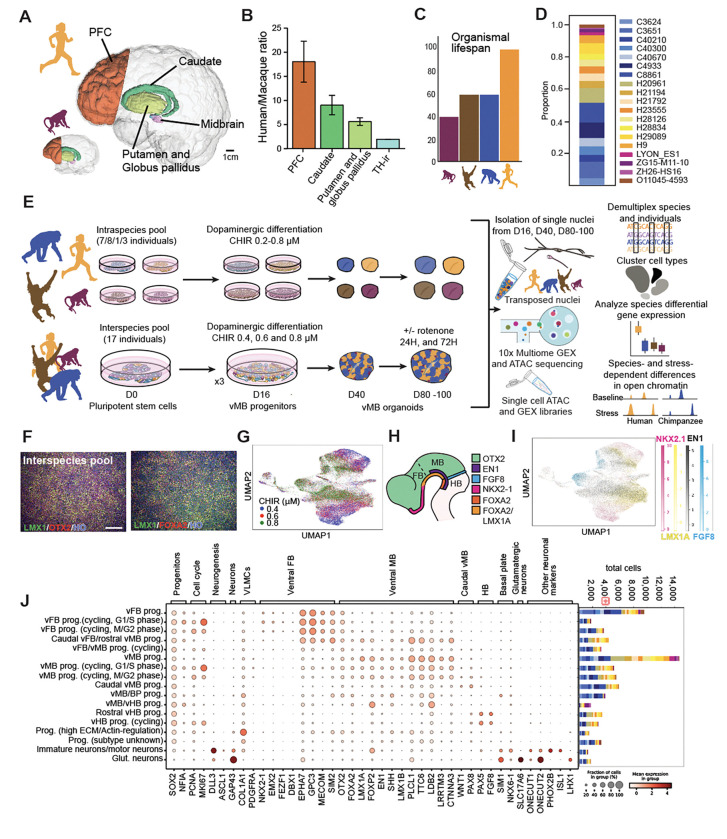

Figure 1:

Pluripotent stem cell-derived interspecies cultures model primate ventral midbrain specification and development A. Unequal scaling of dopamine target regions in human compared to macaque with regions quantified by MRI highlighted.

B. Human/macaque volume ratios from MRI quantification of dopamine target regions PFC (19.52 ± 4.24, p=3.33E-08), caudate (9.17 ± 2.01, p=5.56E-11), and putamen/globus pallidus (5.68 ± 0.78, p=3.54E-09, n=10 human individuals, n=3 macaque individuals). The ratio of DA neuron numbers was calculated through comparison of TH-ir cells stereotactically quantified by8,9 (1.93 ± 0.024, p=4.95E-07, n=6 human individuals, n=7 macaque individuals).

C. An increased organismal lifespan101,102,103 is an additional factor that contributes to the enhanced stress human DA neurons face.

D. Proportions of all individuals at D16, post quality control and doublet removal. Human lines: H9, H20961, H21194, H21792, H23555, H28126, H28334, H29089; Chimpanzee lines: C3624, C3651, C4933, C8861, C40210, C40300, C40670; Orangutan line: O11045–4593; Macaque lines: LYON-ES1, ZG15-M11–10, ZH26-HS16.

E. Experimental design for generating inter- and intraspecies midbrain organoids for paired snRNA- and ATAC-sequencing.

F. Interspecies ventral midbrain culture at D14, with immunocytochemical labeling of FOXA2, OTX2 and LMX1A/B.

s.

G. UMAP of cells collected at D16, colored by MULTI-seq barcode identity which corresponds to the applied CHIR99021 concentration.

H. Rostral-caudal expression domains of key genes to determine cell identity within ventral diencephalon, midbrain and hindbrain.

I. UMAP of cells collected at D16, colored by key genes to determine rostral-caudal identity.

J. Dotplot of the expression of cell type markers for the assigned cluster identities at D16 (left), with a bar chart of the contribution of individuals to the different cell types (right), with colors as labeled in D.

Scale bars: 200 μm. For the bar chart in Figure 1A, data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. See also Figure S1 and S2.

PFC, prefrontal cortex; TH, Tyrosine hydroxylase; prog, progenitors; vMB, ventral midbrain; vFB, ventral forebrain, vHB, ventral hindbrain; BP, basal plate; ECM, extracellular matrix; glut, glutamatergic; DA, dopaminergic; VLMCs, vascular leptomeningeal cells.

We next established cellular models to explore developmental gene regulatory programs that may contribute to species differences in connectivity and cellular vulnerability. To study divergence in gene expression and chromatin accessibility during primate midbrain specification and differentiation, we developed a phylogeny-in-a dish approach where multiple PSC-lines (human=8, chimpanzee=7, orangutan=1, and macaque=3, Figure 1D, see Table S2 for experimental details) were differentiated together into ventral midbrain progenitors as either intra- or interspecies pools27,29,30, using an established protocol31 that produces functional DA neurons, validated in preclinical models of PD32–34, adapted to 3D maturation conditions (Figures 1E and S1C). Pooling many PSC-lines for differentiation provides an efficient strategy to isolate cell-intrinsic differences that can be attributed to species, rather than cell lines, batch effects, or culture conditions.

In vitro specification to ventral midbrain identities recapitulates the developmental morphogen environment and relies on Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling for ventralization to a floor plate identity and activation of WNT signaling, by the addition of the GSK3 inhibitor CHIR99021 (CHIR), to obtain midbrain fates. To generate cell type identities corresponding to the rostro-caudal extent of the developing midbrain, including the caudal diencephalon and rostral hindbrain35, we employed three different concentrations of CHIR in parallel pools and used immunocytochemistry to confirm patterning to ventral midbrain identities (Figures 1F and S1D–S1F, and S1G–J for additional outgroup individuals).

After verifying overall patterning, we proceeded to measure gene expression and chromatin accessibility in single cells via snRNA-and snATAC-sequencing (10x Genomics Multiome kit) from the different pools (Figure S2A and Table S2). Following the removal of doublets and low quality cells, 73,077 nuclei were retained for downstream analysis across three experiments, 38,066 from interspecies pools and 35,011 from intraspecies pools (Figure S2B and Table S2). Demultiplexing species and individual identity revealed comparable numbers of human (30,543) and chimpanzee (37,523) cells, and preservation of all individuals in intra- and interspecies pools (Figures 1D and S2E–S2G).

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the gene expression data at day 16 (D16) revealed species and maturation/cell cycle stage as the main drivers of separation along PC1 and PC2, respectively (Figures S2H and S2I). To identify homologous cell types between species, batch integration of batch-balanced k-nearest neighbors (BBKNN) was applied, resulting in Leiden clusters with mixed species contributions (Figures S2C, S2D and S2J). Labeling cells based on pool-of-origin CHIR concentration using MULTI-seq barcodes36 revealed a gradient of CHIR concentrations across the UMAP (Figures 1G), which corresponded to a gradient of genes with defined rostral to caudal expression patterns (Figures 1H and 1I). Consensus non-negative matrix factorization (cNMF)37 indicated that increasing CHIR concentration shifted cells from rostral to caudal ventral midbrain progenitor identities across species (Figures S2O–S2Q).

Using cluster-enriched genes and known markers from the literature, we assigned cell type identities to each cluster and confirmed the presence of progenitor cell types ranging from diencephalon to hindbrain, with ventral midbrain progenitors being the most abundant (Figures 1J and S2K). At this stage of differentiation, the majority of cells were still proliferative progenitors, with a smaller subset of postmitotic neurons (Figure S2L). The expression of regional marker genes supported the equivalent response of human and chimpanzee lines to the patterning protocol (Figures S2M and S2N). Additionally, all individuals from all four species (with the exception of one macaque line) were represented in each cell type cluster (Figure 1J and Table S2).

In summary, phylogeny-in-a-dish culture enables equivalent patterning of human and chimpanzee PSCs to homologous progenitor subtypes, including ventral midbrain progenitors, and allows for comparative analysis of molecular programs underlying early stages of specification.

Transcriptional landscape, reproducibility, and fidelity of interspecies organoids

To study the development and maturation of DA neurons and related neuronal subtypes, D16 progenitors were aggregated into neurospheres for continued culture in a 3D environment (Figures S1K, S1L, S1N and S1O). Immunohistochemistry revealed abundant DA neurons in all four species (Figures 2A, S1N, S1P, S1Q and S1S) and in interspecies pools (Figures 2B, S1M, S1O and S1R), with a predominance of TH+ axons at the periphery. DA neurons in D40 organoids formed TH+ projections that innervated fused cortical organoids in mesocortical assembloids (Figure S1T). High-density multi-electrode array (HD-MEA) recordings initially showed mainly uncoordinated, tonic spiking at D60, with some coordinated burst activity emerging in both human and chimpanzee organoids cultured on the HD-MEA around D70 (Figures S3A and S3C). By D90, bursts (clear groupings separated by less active periods, characterized by bimodal inter-burst intervals) emerged in human and chimpanzee organoids (Figures S3B and S3D). At this point, bursts recruited most detected neural units, and tended to last 0.5–1.5 seconds (Figures S3B, S3D and S3E–F). Spontaneous dopamine release could be detected by D30, increased over the next few weeks, and then remained stable (Figures S3G–I). These analyses suggest that ventral midbrain organoids recapitulate important structural and functional aspects of normal DA neuron development.

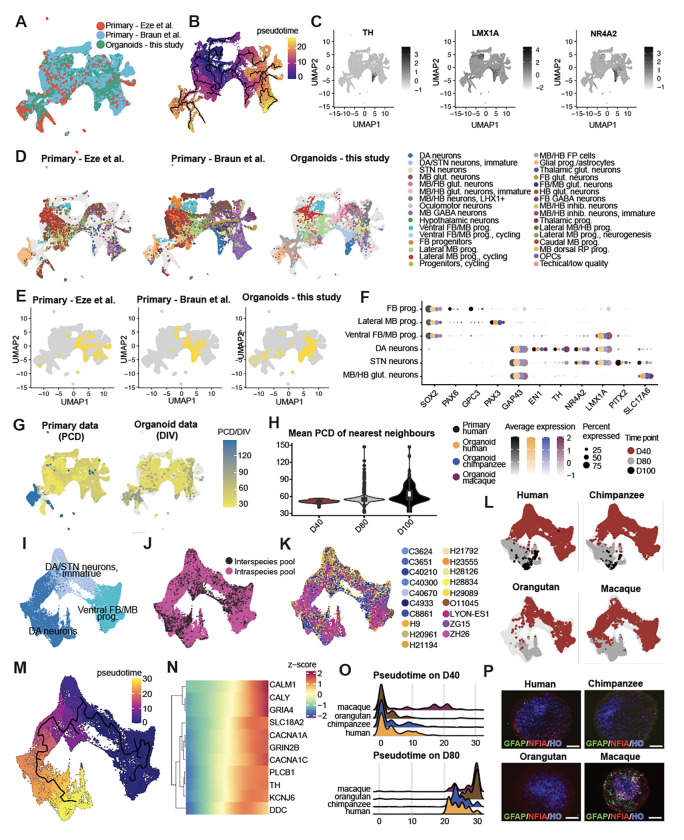

Figure 2:

Transcriptional landscape, cell type diversity and reproducibility of developing primate ventral midbrain organoids A. Ventral midbrain organoids from the human pool (n=8 individuals), chimpanzee pool (n=7 individuals), orangutan (O11045–4593), and macaque (LYON-ES1), labeled for TH, FOXA2 and Hoechst at D40 and D80.

B. Interspecies ventral midbrain organoids, labeled for TH/FOXA2 or TH/MAP2 and Hoechst at D40, 80 and 100.

C. Proportions of all individuals at D40, 80 and 100, post quality control and doublet removal.

D-F. UMAPs of cells collected at D40–100, colored by species (D), timepoint (E) and assigned cell type identity (F).

G. Dotplot of the expression of cell type markers for the assigned cluster identities at D40–100 (left), with a bar chart of the contribution of individuals to the different cell types (right), with colors as labeled in C.

H. UMAPs for each individual, colored by cell type identity.

I. Cell type proportions at D40, for each individual where data from both interspecies and intraspecies pools were collected.

J. Histograms summarize distribution of cell type correlations across marker genes between conditions for each level of experimental design and replication for D40–100 cell types. Cell type transcriptomes are highly correlated for interindividual comparisons within species, comparisons across CHIR conditions, and comparisons across pool types. Note that the increased divergence across species likely represents real biological variation (as observed in vivo41) and is greater than that from all other levels of experimental design, consistent with the overall reproducibility of our study and our power to discover species differences in gene regulation.

Scale bars: 200 μm. See also Figure S1, S2 and S3.

prog, progenitors; vMB, ventral midbrain; vFB, ventral forebrain, vHB, ventral hindbrain; BP, basal plate; ECM, extracellular matrix; glut, glutamatergic; GABA, GABAergic; DA, dopaminergic; STN, subthalamic nucleus; FP, floor plate.

While the multiome data from D16 progenitors captured early stages of cell type specification and commitment, measuring gene expression and chromatin accessibility from organoid stages (D40–100) enables comparative studies of the molecular basis of later developmental events including axonogenesis, neurotransmitter synthesis, and the onset of neuronal activity. To increase the temporal resolution of the maturation process, data was collected from D40, 80 and 100 (Figure 2E). After removing low quality cells, doublets, and clusters defined by high endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress38,39, 105,777 cells remained for clustering and downstream analysis. Even after extended organoid culture, all human and chimpanzee individuals were recovered from both intra- and interspecies pools (Figures 2C, 2D and S2E–G; total number of cells: chimpanzee=39,300, human=27,293). Due to loss of cells from outgroup species in the interspecies pool, additional samples of macaque and orangutan (contributing to a total of macaque=27,969 and orangutan=11,215 cells), maintained and matured in parallel with thawed replicate samples of human and chimpanzee intraspecies pools were added from subsequent differentiations (Table S2).

BBKNN integration and Leiden clustering resulted in 30 mixed species clusters (Figures S2R and S2S). Cell type identities were manually assigned using cluster-enriched genes and known markers (Figures 2F, 2G and S2T–X), and constituted a mix of both species and individual identities (Figure 2G). While human and chimpanzee progenitors gave rise to a range of neuronal subtypes including DA, glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons (Figures S2U and S2V), the macaque lines predominantly yielded cells of the DA lineage, and contributed less to the other cell type clusters (Figures 2G and S2X). Interestingly, there was a cluster of immature neurons with mixed DA/STN marker expression which split into separate DA and STN neuron clusters with maturation, consistent with previously described transcriptional similarity of these two lineages during development40.

We next investigated the reproducibility in cell type compositions across species, individual and pool type. At both D16 (Figure S4A) and D40–100 (Figure 2H), comparable representation of cell types across individuals was observed, highlighting the robustness of the patterning protocol. This reproducibility also extended to pool type, where similar representations of cell type identities between human and chimpanzee individuals were seen at D16 and D40 regardless if the individual was part of an intra- or interspecies pool (Figure 2I, Figure S4B), further supporting the use of our novel interspecies culture system. To quantify reproducibility, we calculated Pearson correlations for cell type marker genes between conditions at each level of experimental design and replication for D40–100 cell types (Figure 2J). Cell type transcriptomes were highly correlated for interindividual comparisons within species (human: r=0.964; chimpanzee: r=0.976; macaque: r=0.961), across CHIR conditions (r=0.880), experiment (r=0.884) and pool types (r=0.917). Importantly, transcriptional divergence across species (r=0.760) was greater than that from all other levels of experimental design, consistent with cross-species biological variation observed in vivo41 and supporting the power of our study to discover species differences in gene regulation. Finally, we observed conserved expression of canonical marker genes within the DA lineage at both D16 and D40–100, between species, individuals and pool types, further emphasizing the reproducibility of DA neuron specification across experimental conditions (Figure S4C).

Having established the robustness and reproducibility of our experimental model system, we sought to evaluate the fidelity and maturation of organoid-derived DA neurons. Co-embedding with ventral midbrain data from two primary human datasets42,43 revealed co-clustering of homologous cell types (Figures 3A–E, S5A) and shared marker gene expression between primary cells and organoid cells across species (Figure 3F). We next compared the differentiation stage of organoid cells with the absolute age of available primary DA neurons (Figures 3G and 3H). Analysis of shared nearest neighbors among co-embedded cells revealed that maturation in organoids correlates with the age of primary neurons (D40 mean = PCD 51.32, D80 mean = 56.43, D100 mean = 62.72). We further performed pseudotime analysis to compare DA lineage differentiation trajectories between species (Figures 3I–O). These trajectories were similar across pool types and individuals (Figures 3J–L) and reflected the gradient of differentiation stages of captured cells (Figures 3M–O). We observed induction of genes associated with DA neuron maturation, including KCNJ6 (GIRK2), TH, and SLC8A2. Interestingly, pseudotime analysis revealed delayed maturation in apes compared with rhesus macaque (Figure 3O), consistent with known differences in gestation time, and a trend for a subtle delay in maturation at D80 in human compared with chimpanzee, consistent with differences observed among cortical neurons44. Glial competence, an orthogonal measurement of organoid development, further supported the accelerated differentiation rate in macaque midbrain compared to apes (Figure 3P).

Figure 3:

Midbrain organoid fidelity to primary midbrain data and DA neuron maturation timing in human and non-human primates A. Combined UMAP including two published developing human midbrain datasets from Eze et al (including unpublished data from one additional human individual that we collected) and Braun et al and human midbrain organoids from this study, colored by data source.

B. UMAP colored by pseudo time.

C. UMAPs colored by gene expression of TH, LMX1A and NR4A2.

D. UMAPs colored by supervised cell types, split by data source.

E. UMAPs with DA neurons highlighted, split by data source.

F. Dotplot for marker gene expression in 6 cell types shared in in vivo primary and in vitro organoid datasets.

G. UMAPs colored by timepoint (PCD for primary and DIV for organoids), split by data type

H. Violin plot for distribution of mean PCD of nearest primary neighbors of DA neurons in organoids, grouped by timepoint.

I-K. UMAP for integrated in vitro organoid DA lineage from 4 species, colored by assigned cell types (I), pool type (J) and individual (K).

L. UMAPs of DA lineage cells colored by timepoint and split by species.

M. UMAP colored by pseudotime defined within the DA lineage.

N. Heatmap for expression of neuronal genes along the DA lineage pseudotime.

O. Ridgeplot for pseudotime distribution in DA neurons in 4 species on D40 (top) and D80 (bottom).

P. Immunohistochemistry of human pool, chimpanzee pool, macaque (ZH26), and orangutan (O11045) D80 organoids, to visualize GFAP+ and NFIA+ glial progenitors/astrocytes, counterstained with hoechst (HO). Scale bars: 200 μm.

PCD, post conception day; DIV, day in vitro; prog, progenitors; vMB, ventral midbrain; vFB, ventral forebrain, vHB, ventral hindbrain; BP, basal plate; ECM, extracellular matrix; glut, glutamatergic; GABA, GABAergic; DA, dopaminergic; STN, subthalamic nucleus; inhib, inhibitory; FP, floor plate.

In summary, ventral midbrain organoids display reproducible composition and high marker gene conservation across experiments, pool types, individuals, and species. DA neurons show high fidelity to human fetal development, corresponding to midgestation DA neurons, with maturation increasing over time and D100 DA neurons matching the oldest primary human DA neurons collected. Cross-species comparisons highlight comparable cell type diversities and maturation dynamics between human and chimpanzee, enabling the study of species-specific transcriptional differences during the development and maturation of DA neurons and other midbrain cell types.

Cell type specificity and evolutionary divergence of gene expression across ventral midbrain development

To compare gene expression across species while minimizing the impact of differences in annotation quality, we mapped the snRNA-seq data from all species to an inferred Homo/Pan common ancestor genome45, with annotations further optimized for single cell transcriptomics analyses46. To explore the major sources of gene expression variation in our datasets, we first performed variance partition analysis47 on pseudobulk samples for each cell type and gene. Species of origin explained the highest percent of gene expression variance (mean across cell types and genes that met filtering criteria, D16: 19.9%, D40–100: 17.5%), with smaller contributions from individual (cell line) (D16: 7.6%, D40–100: 5.5%), experiment (D16: 4.5%, D40–100: 5.3%), differentiation day (D40–100: 4.9%), pool type (inter- vs intra-species)(D16: 6.4%, D40–100: 1.3%), sequencing lane (D16:1.9%, D40–100: 1.6%) and biological sex (D16: 0.47%, D40–100: 0.36%)(Figure S6A–D).

To compare human and chimpanzee ventral midbrain cell types, we analyzed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using linear mixed models based on pseudobulk samples across cell types, implemented with the dreamlet package48,49 (Figure S6A and S6E–G). We modeled the D16 and D40–100 datasets separately and included the top terms from our variance partition model. As expected, more human-chimpanzee DEGs were detected among more abundant cell types (Figure 4A, dotplot). After filtering for cell types that had at least 200 human and 200 chimpanzee cells, we plotted the correlation of differential expression scores (Methods) for all differentially expressed genes across all cell types (Figure 4A, heatmap). D16 cell types clustered together as did D40–100 cell types, with higher correlations indicating more similar magnitude and direction of differential expression between more closely related cell types.

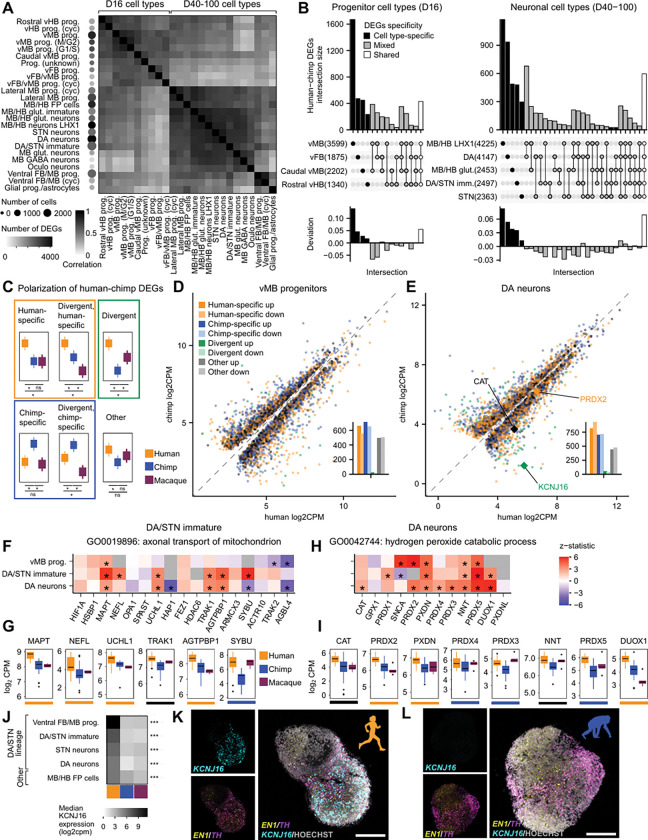

Figure 4:

Cell type specificity and evolutionary divergence of gene expression across ventral midbrain development A. Clustered heatmap showing Pearson correlation between human-chimpanzee DEG scores (logFC * −log10pval) for all genes that were DE in at least one cell type across all D16 and D40–100 cell types with at least 200 cells for both human and chimpanzee. Dotplot on the left shows the number of human and chimpanzee cells (least common denominator) for that cell type, shaded by the number of human-chimpanzee DEGs with FDR < 0.05.

B. UpSet plots showing the intersection of human-chimpanzee DEG lists for selected D16 (left) and D40–100 (right) cell types, ordered from cell type specific to shared intersections. Numbers in parentheses represent the total number of human-chimpanzee DEGs for that cell type.

C. Scheme for classifying human-chimpanzee DEGs showing which comparisons are significant for each category (*, FDR < 0.05).

D. Scatterplot showing average normalized expression across pseudobulk samples for each human-chimpanzee DEG in human versus chimpanzee D16 vMB progenitors, with points colored by categories from C and dotted y = x line. Barplots (insets) show the number of up- and down-regulated genes in each category.

E. Same as D for D40–100 DA neurons.

F. Heatmap showing z statistics for expressed genes in the top human-upregulated GO term in immature DA/STN neurons.

G. Boxplots for human-chimpanzee DEGs belonging to the top human-upregulated GO term in immature DA/STN neurons showing normalized median gene expression values across pseudobulk samples (combination of species, experiment, individual) across species with colored lines below indicating polarization category.

H-I. Same as F-G for the top human-upregulated GO term in DA neurons.

J. Heatmap showing normalized median expression of KCNJ16 across human, chimpanzee, and macaque pseudobulk samples. KCNJ16 expression did not meet the expression threshold in the remaining D40–100 cell types.

K-L. RNAscope of TH, EN1 and KCNJ16 in D40 intraspecies pooled organoids from human (K) and chimpanzee (L).

Scale bars: 200 μm

DEGs, differentially expressed genes; prog, progenitors; vMB, ventral midbrain; vFB, ventral forebrain, vHB, ventral hindbrain; glut, glutamatergic; GABA, GABAergic; DA, dopaminergic; STN, subthalamic nucleus; Oculo, oculomotor

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

To examine the cell type specificity of differential gene expression, we constructed UpSet plots showing the intersection of human-chimpanzee DEGs sets for a subset of progenitor cell types from D16 and neuronal cell types from D40–100. Plotting the deviation for each set intersection showed that there were more cell type-specific and shared human-chimpanzee DEGs than expected based on the number of significant DEGs for each cell type, while DEGs with mixed specificity (shared between some but not all of the plotted cell types) were relatively depleted (Figure 4B).

Next, we focused on the DA lineage (including ventral midbrain (vMB) progenitors (D16), immature DA/STN neurons (D40–100), and DA neurons (D40–100). We examined the evolutionary history of human-chimpanzee DEGs and classified them into four categories based on the significance of gene expression differences in two-way comparisons between human, chimpanzee, and macaque: human-specific (likely derived in the human lineage - human significantly different than chimpanzee and macaque), chimpanzee-specific (chimpanzee significantly different than human and macaque), divergent (all three comparisons significant with macaque gene expression in between human and chimpanzee), and other (human versus chimpanzee is significant but neither species is significantly different from macaque) (Figure 4C, Table S4).These polarization categories could be superimposed on scatterplots showing the average expression of each human-chimpanzee DEG across human versus chimpanzee (Figures 4D, 4E, and S6L) or macaque (Figures S6J, S6K, and S6M) pseudobulk samples in each cell type. In both vMB progenitors and DA neurons, there were similar numbers of human-specific up, human-specific down, chimpanzee-specific up, and chimpanzee-specific down genes (Figures 4D and 4E, insets), supporting our analysis strategy as unbiased. To examine the extent to which organoid models recapitulate species differences, we combined publicly available human and rhesus datasets with newly generated data from 7 individuals (Figures S5A–S5E). The magnitude and direction of differential gene expression in the DA lineage was significantly correlated between human and macaque in vitro models and primary cells across differentiation (Figure S5F) and across species (Figure S5G).

To identify the types of genes that were differentially expressed, we performed competitive gene set analysis on linear mixed model results for human versus chimpanzee in DA lineage cell types. None of the gene sets were significantly enriched at the study-wide FDR (Table S4), reflecting the overall similarity of gene expression in human versus chimpanzee cell types and the low-magnitude, predominantly quantitative expression differences between closely related species. However, several of the top-ranked, nominally significant terms were related to our initial hypotheses about increased connectivity and metabolic demands on human DA neurons. The top two human-upregulated terms in immature DA/STN neurons (but not vMB progenitors or DA neurons) were related to mitochondrion transport: “axonal transport of mitochondrion” (p = 0.003, FDR n.s.) and “mitochondrion transport along microtubule” (p = 0.003, FDR n.s.)(Figure 4F). Moreover, two thirds of the significant human-upregulated genes in this category were classified as human-specific (Figures 4G, S6H, and S6N). In DA neurons, the top human up-regulated term was related to antioxidant activity (“hydrogen peroxide catabolic process”, p = 0.002, FDR = n.s.)(Figure 4H) and several of the significantly human-upregulated genes were human-specific (Figures 4I, S6I, and S6O). Four members of the Peroxiredoxin gene family were expressed at higher levels in human than chimpanzee DA neurons, including human-specific upregulation of PRDX2. Interestingly, one of the human-upregulated genes in this set was CAT (human vs chimpanzee adj.p.val = 0.039), which encodes the enzyme catalase that degrades hydrogen peroxide and was previously reported to be significantly upregulated in human versus chimpanzee and macaque primary cortical neurons50.

Next, we focused on DEGs with high cell type specificity within DA/STN lineage cell types, reasoning that they may have functions specific to the DA system. We calculated the cell type specificity of gene expression across all D40–100 cell types and ranked human-specific and divergent DEGs by their DA lineage specificity scores (Table S4). The top-ranked gene (for both immature DA/STN neurons and DA neurons) was KCNJ16, which encodes a pH-sensitive inward-rectifying potassium channel subunit. This gene had highest expression in progenitors but maintained significant expression levels throughout neuronal differentiation, with human expression levels significantly higher than chimpanzee and macaque (Immature DA/STN neurons: human-specific, human vs chimpanzee: logFC = 5.49, p = 6.12e-16, human vs macaque: logFC = 6.92, p = 3.07e-08; DA neurons: divergent, human vs chimpanzee: logFC = 5.06, p = 2.10e-12, human vs macaque: logFC: 3.42, p = 1.64e-06)(Figure 4J). Using RNAscope, we validated human-upregulated KCNJ16 expression colocalizing with DA markers EN1 and TH (Figures 4K, 4L and S6P–S6R), highlighting a molecular change that could contribute to evolved physiological differences in the DA lineage.

Together, these results represent a resource of human-specific DEGs in ventral midbrain cell types and suggest molecular pathways that may be involved in evolutionary adaptations of the human DA system.

Evolution of the cis-regulatory landscape in ventral midbrain neurons

To explore cis-regulatory evolution underlying gene expression differences in ventral midbrain cell types, we turned to the paired snATAC-seq data. To compare open chromatin regions across species, we developed a cross-species consensus peak pipeline, CrossPeak, that focuses on precisely localizing orthologous peak summits across species without introducing species bias. CrossPeak takes as input a set of fixed width, summit-centered peaks for each species and produces a consensus set of peaks across species in the coordinates of each species’ genome as well as retaining species-specific peaks that failed to lift over (Figure 5A, Methods).

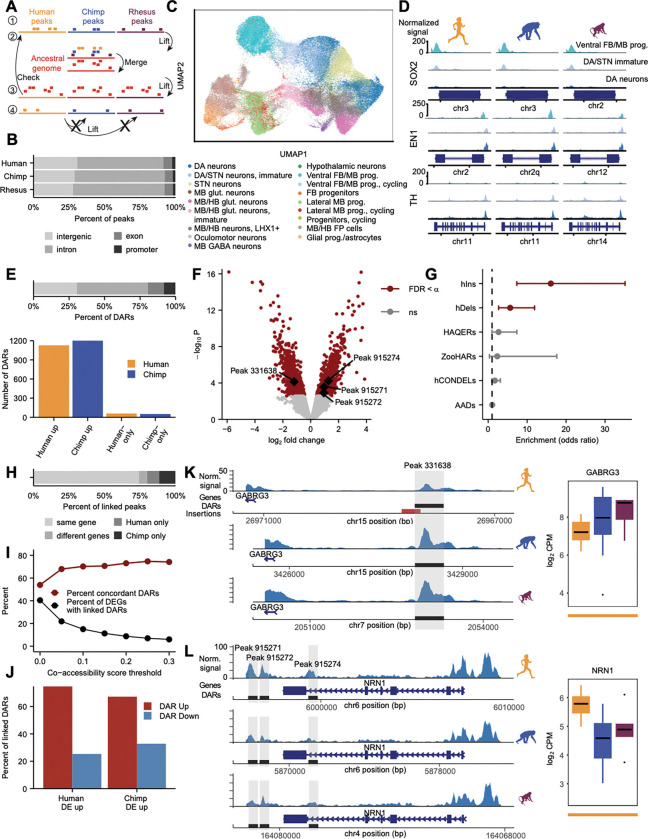

Figure 5:

Evolution of the cis-regulatory landscape in ventral midbrain neurons A. Schematic of computational pipeline for identifying consensus and species-specific ATAC-seq peaks across species. Step 1: Use iterative overlap merging to obtain a peak set for each species across all cell types. Step 2: Lift each species peak set to an ancestral genome and merge overlapping peaks according to user-defined rules. Step 3: Lift the consensus peak set back to individual species genomes and check the new position against the original location. Step 4: For any peaks that failed to lift over in steps 2 or 3, attempt to lift them over directly to the other species’ genomes and classify them as species-specific peaks if direct liftover fails.

B. Stacked barplot showing the percent of step 1 peaks called within each species located in each genomic category.

C. The consensus peak set (step 3 peaks) allows integration of human, chimpanzee, and macaque multiome snATAC-seq data. Cells are colored based on their snRNA-seq cell type annotation.

D. Accessibility at marker genes within DA lineage cell types across species.

E. Top, stacked barplot showing the percent of human-chimpanzee DARs and species-only peaks in DA neurons located in each genomic category. Bottom, barplot showing the numbers of human-up and chimpanzee-up consensus DARs and the numbers of human-only and chimpanzee-only peaks.

F. Volcano plot for human-chimpanzee consensus DARs in DA neurons with alpha = 0.1.

G. Forest plot showing odds ratios and confidence intervals for the enrichment of evolutionary signatures within human-chimpanzee DA neuron DARs and species-only peaks with alpha = 0.05.

H. Stacked barplot showing the percent of peaks that were linked via Cicero (within DA lineage cell types ventral FB/MB progenitors, DA/STN immature neurons, and DA neurons) to the same gene or different genes within human and chimpanzee data, or were linked only in human or only in chimpanzee.

I. Plot showing the relationship between co-accessibility score threshold applied to Cicero links and the percent of DA neuron DEGs with linked DA neuron DARs as well as the percent concordant DARs (defined as the percent of DARs with increased accessibility linked to upregulated DEGs, considering links found in the species where the gene was upregulated).

J. Barplot plot showing concordance as the percent of DA neuron DARs linked to upregulated DA neuron DEGs in each species at co-accessibility threshold 0.15. (n = 181 human-up DEGs with 229 linked DARs, 173 of chimpanzee-up DEGs with 231 linked DARs).

K. Example of human-downregulated DA neuron DAR linked to human-specific downregulated DA neuron DEG GABRG3. Left, pseudobulk DA neuron snATAC-seq signal across human, chimpanzee, and macaque. The DAR overlaps a human-specific insertion from51. Right, boxplot showing normalized GABRG3 gene expression values for pseudobulk samples across species. Line at bottom indicates polarization as in Fig. 4.

L. Example of four human-upregulated DA neuron DARs linked to human-specific upregulated DA neuron DEG NRN1.

DARs, differentially accessible regions; FDR, false discovery rate; ns, not significant; hIns, human-specific insertions; hDels, human-specific deletions; HAQERs, human ancestor quickly evolved regions; ZooHARs, Zoonomia-defined human accelerated regions; hCONDELs, human-specific deletions in conserved regions; AADs, archaic ancestry deserts; DEGs, differential expressed genes

The majority of peaks called in human, chimpanzee, and macaque D40–100 cell types were located distal to gene promoters, in introns, and intergenic regions with a smaller proportion of peaks falling in exons and promoter regions (Figure 5B). After cross-species peak merging, we quantified read counts in each species and performed quality control (Figure S7A), which yielded 80,123 cells with high-quality paired snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq data (human = 23,962, chimpanzee = 33,016, macaque = 23,145). Integrating across species and performing dimensionality reduction on the snATAC-seq dataset while annotating cells with their snRNA-seq-defined cell type revealed similar structure in the snATAC-seq dataset as described above for snRNA-seq, with progenitors clustering separately from neuronal cell types and neurons separating by neurotransmitter and regional identity (Figures 5C, S7B, and S7C). Canonical marker genes for DA lineage cell types showed conserved promoter accessibility across species (Figure 5D), supporting the quality of the snATAC-seq dataset and cell type annotations.

To identify candidate cis-regulatory differences across species, we utilized the dreamlet package to perform differential accessibility testing of cross-species consensus peaks (species-only peaks meeting the same accessibility threshold were included separately in later analyses, Methods) across pseudobulk ATAC-seq samples within DA lineage cell types, adjusting our approach slightly compared to the RNA-seq model described above to improve modeling of inherently sparse ATAC-seq data (Methods). Most human-chimpanzee DARs that we identified were specific to progenitor, immature, or mature neuronal stages, with a smaller percentage shared across the DA lineage (Figure S7D). Focusing on DA neurons, human-chimpanzee differentially accessible regions (DARs) were predominantly located in noncoding regions of the genome and similar numbers of DARs had higher accessibility in each species (Figures 5E and 5F).

To study human-specific regulation in DA neurons, we intersected DARs and species-only peaks with human-specific evolutionary variants, including human-specific insertions (hIns)51, human-specific deletions (hDels)51, human ancestor quickly evolved regions (HAQERs)52, Zoonomia-defined human accelerated regions (zooHARs)53, indel-sized human-specific deletions in conserved regions (hCONDELs)54, and archaic hominin ancestry (admixture and incomplete lineage sorting) deserts (AADs)55, and found that hDels and hIns were significantly enriched in human-chimpanzee DARs (compared to a background set of all accessible peaks included in the analysis) (Figure 5G and Table S5), emphasizing the contribution of structural variants to cis-regulatory evolution.

To understand categories of genes that could be regulated by DARs, we annotated DARs using GREAT56,57. A majority of the top gene ontology (GO) terms were related to cyclic nucleotide biosynthesis and metabolism, including cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling (Figures S7J and S7L). DARs within the regulatory domains of related genes were split between those with higher chromatin accessibility in human versus chimpanzee (42% and 58% of 50 DARs, respectively). Only 18% of these genes were differentially expressed between human and chimpanzee (46% of genes with above-threshold expression). Since cyclic nucleotide signaling is context-dependent, changes in gene regulation may only become apparent at the gene expression level in response to specific environmental or cellular stimuli. Interestingly, increased cGMP levels promote DA neuron mitochondrial function and may be neuroprotective in mouse models of PD58.

To further explore the concordance between differential accessibility and gene expression, we linked accessible chromatin regions to genes in both human and chimpanzee using Cicero, which utilizes a regularized correlation metric to predict co-accessibility in snATAC-seq data59. Most peaks were linked to the same gene in both species, with a smaller percentage linked to different genes or linked only in one species (Figure 5H). Each gene had a median of 6 linked peaks, and the majority of peaks were linked to a single gene in both species (Figures S7E and S7F). Since the total number of peak-gene links depended on the threshold applied to co-accessibility scores between accessible regions (with higher thresholds retaining only links with the strongest correlations), we plotted results across thresholds (Figure 5I). The percent of DE genes with linked DARs (regardless of direction) ranged from 6% at the most stringent threshold to 40% at a threshold of 0 (retains all links between regions within 500 kb), within the range of previous reports50. Reasoning that higher signal-to-noise would allow more reliable identification of correlations between regions with higher accessibility, we defined percent concordance as the percent of DARs with increased accessibility linked to upregulated DEGs, considering links defined in the species where the gene was upregulated. The percent concordance ranged from near-chance level (54%) at a threshold of 0 to 74% at the most stringent threshold (Figure 5I). At an intermediate threshold, approximately two thirds of DARs linked to upregulated DEGs in each species had increased accessibility in that species (Figure 5J, S7G, and S7H).

Although the majority of DARs were located distally with respect to gene promoters, DARs that overlapped promoters of DEGs had a high level of concordance with gene expression (80% of DAR-DEG promoter pairs representing 72 peaks and 61 genes). A representative example is RNAscope-validated human-upregulated gene KCNJ16, whose promoter overlaps two DARs with higher accessibility in human compared to chimpanzee and macaque (Figure S7K).

We next investigated DARs that overlapped enriched categories of human-specific sequence variation (Figure 5G). One prominent example is a DAR located about 2.5 kb upstream of the GABRG3 promoter which partially overlaps a 326-bp human-specific insertion. This DAR had reduced accessibility in human compared to chimpanzee (p = 0.009) and GABRG3, which encodes an isoform of the gamma subunit of the GABAA receptor, displayed human-specific downregulation (p = 1.39e-06) (Figure 5K).

We also ranked genes by the number of concordant linked DARs. Interestingly, several of the top genes are known or predicted to be directly involved in neurite projection organization, including EPHA10, NRN1, and NTNG2 (minimum ranks 2, 7, and 7, respectively), and all of these genes were upregulated in human compared to chimpanzee (EPHA10: p = 1.14e-19, NRN1: p = 5.24e-06, NTNG2: p = 4.72e-10). NRN1, for example, was classified as a human-specific upregulated gene and had three linked DARs (one intronic, p = 0.008 and two intergenic with p = 0.023 and p = 0.062) with increased accessibility in human, as well as slightly but not significantly increased promoter accessibility (Figure 5L). The NRN1 gene encodes a small, extracellular cell surface protein which has increased expression in response to neuronal activity60, promotes axon outgrowth in retinal ganglion cells61 and has been shown to be neuroprotective in neurodegenerative disease62,63.

In summary, we present a resource of regions with differential chromatin accessibility between human and chimpanzee across the DA lineage, identify structural variations that may underlie species differences, and link DARs to candidate genes whose expression they may regulate.

Conserved and divergent gene regulatory networks in ventral midbrain specification and maturation

We next examined the regulatory network context for species differences in gene expression and accessibility. Using SCENIC+64, we identified enhancer-driven gene regulatory networks (eGRNs) throughout the specification and maturation of midbrain cell types (Figures 6A–6C, S7P and S7Q, Methods). At D16, the analysis recovered 113 TF-driven eGRNs in human and 91 in chimpanzee, with a median size of 82 regions and 49.5 genes (Table S6). These eGRNs include many conserved master regulators with established roles in conferring or maintaining regional identity. These hub TFs were enriched in the expected progenitor subtypes, including LMX1A, EN1 and FOXA1 in midbrain progenitors (Figures S7P and S7Q). In addition, TFs with important roles for progenitor to neuron specification, such as SOX2, HES1, POU3F2, were active at different stages of maturation (Figures S7P and S7Q).

Figure 6:

Conserved and divergent gene regulatory networks in ventral midbrain specification and maturation A. Activator eGRNs in the developing human midbrain organoids (D40–100) projected in a weighted UMAP based on co-expression and co-regulatory patterns. Nodes label hub TFs of eGRNs with number of target genes (color) and target regions (size) plotted, and edges label co-regulatory networks between eGRNs.

B. Scatterplots of number of genes (right) and number of regions (left) in activator eGRNs identified in humans versus chimpanzees.

C. Scatterplots of eGRN specificity score in D16 vMB progenitors and D40–100 DA neurons in human versus chimpanzee, calculated based on target gene expression (left) and target region accessibility (right).

D. eGRNs that have targets enriched for species-specific upregulated DEGs against other DEGs in DA lineage in humans or chimpanzees identified by Fisher’s exact test (p< 0.05, where other DEGs are defined as DEGs that are either not human/chimpanzee specific, or human/chimpanzee specific but down regulated in human/chimpanzee). Unions of DEGs from 3 D40–100 cell types (ventral FB/MB progenitors, immature DA/STN neurons, and DA neurons) in the DA lineage were used for testing. TFs are colored if corresponding eGRN targets are significantly enriched for human (yellow), chimpanzee (blue) or both (red) species-specific up-regulated DEGs.

E. Heatmaps for differential expression of hub TFs showing log2FC in human versus chimpanzee (left), and for percentage overlap of species-specific upregulated DEGs in eGRNs in human (middle) and chimpanzee (right) DA lineage cell types. P values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test against overlap with other DEGs.

F. Boxplot of ZFHX3 expression across species in immature DA/STN neurons (line at the bottom represents human-specific polarization category) and human ZFHX3 eGRNs (formulated as TF-peaks-genes) intersecting with upregulated DEGs or DARs in human immature DA/STN neurons.

G. Human eGRNs enriched for upregulated DEGs or DARs in human DA neurons from Fig 6E. Nodes were pruned to include only the top 1500 highly variable genes and peaks and nodes connected to DEGs and/or DARs are shown. Genes or peaks that are human-specific upregulated in DA neurons are highlighted with a black border and genes that are connected with the most edges are labeled.

eGRN, enhancer-driven gene regulatory network; TF, transcription factor; CPM, counts per million; DEGs, differential expressed genes; DARs, differentially accessible regions.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

In D40–100 organoids, 84 human and 114 chimpanzee eGRNs were recovered with a median size of 115 regions and 75.5 genes (Table S6). Since repressive interactions are more challenging to predict64, we chose to focus only on activator networks for downstream analyses. Visualizing human eGRNs based on TF coexpression and co-regulatory patterns highlighted modules that are enriched in midbrain progenitors, neurons, and the DA lineage (Figure 6A). These included eGRNs driven by PBX1 and NR4A2 (Figures 6A and 6C), genes with known functions for the development and survival of DA neurons and with disrupted functions in PD65,66. The numbers of regions and target genes per eGRN were correlated between species (Figure 6B). Similarly, focusing on the DA lineage, the specificity scores of networks were also correlated between species both when calculated based on target region accessibility or gene expression (Figure 6C), supporting broad conservation of trans-regulatory network membership and specificity.

We next asked whether individual eGRNs were enriched in species-specific upregulated genes in the DA lineage in human and chimpanzee, focusing on transcriptional activators identified in both species. Overall, we found a correlation in the fraction of species-specific upregulated DEGs within human and chimpanzee eGRNs (Figure 6D). Considering individual cell types, OTX2- and PBX1-driven networks were enriched for containing upregulated genes in both species, consistent with these eGRNs representing a substrate for regulatory alteration in each lineage. In contrast, some eGRNs, such as those driven by PRRX1, POU2F2, UNCX and ZFHX3 were enriched for upregulated genes in only one species (Figure 6E), with POU2F2 also enriched for upregulated DARs in humans (Figure S7M). Although the UNCX-driven eGRN was enriched for upregulated DEGs in human DA neurons, UNCX itself was chimpanzee-specifically downregulated, suggesting a derived change in the chimpanzee lineage (Figure S7N). However, ZFHX3 showed a derived upregulation in human immature DA neurons and its eGRN was enriched for upregulated target genes in human, including microtubule genes MAPT and TUBB3, representing a candidate human-specific trans-regulatory alteration (Figure 6F). Consistent with trans-regulatory changes downstream of ZFHX3, comparative studies of human and chimpanzee PSCs revealed an excess of species-specific binding sites67. Meanwhile, several genes upregulated in humans that are related to antioxidant activity, including PRDX2, PRDX3, PRDX4, and PRDX5 (Figures 4H and 4I), were predicted to be downstream of NFE2L1 (NRF1), a TF depleted in DA neurons from individuals with PD with an established role in mediating protective oxidative stress responses66,68 (Figure S7O). Together, these analyses indicate a mainly conserved trans-regulatory landscape during ape ventral midbrain development, while highlighting several DA lineage-specific eGRNs enriched in human-specific gene regulatory changes that overlap with DEGs and DARs (Figure 6G).

Oxidative stress induces conserved and species-specific responses in DA neurons

Given the observation of human-specific differences in antioxidant-related gene expression during DA neuron development, we next investigated if induced oxidative stress27,28 could unmask further functionally relevant species differences. We used rotenone, a toxic pesticide associated with PD risk that interferes with the mitochondrial electron transport chain, creating reactive oxygen species69. We optimized the rotenone concentration using single-species human and chimpanzee organoids to obtain a robust transcriptional response in both species without complete loss of DA neurons (Figures S8A–S8D). We applied the optimal concentration to interspecies organoids (Figure 7A), and used immunohistochemistry to visualize the progressive loss of TH+ neurons and fibers (Figures 7B and 7C, S8E–S8J). We collected multiomic data after 24 and 72 hours and after quality and doublet filtering, 28,552 nuclei were retained (Figures S9A–S9D), of which 3,087 were classified as DA neurons (human=1,442, chimpanzee=1,645 cells) based on known marker gene expression (Figures S9E–S9G). An important caveat is that some degenerating DA neurons may not have been identified due to loss of subtype-specific marker expression during the stress response (Figure S9F).

Figure 7:

Oxidative stress induces conserved and species-specific responses in DA neurons in interspecies organoids A. Experimental design for rotenone induced oxidative stress in interspecies organoids. D80 interspecies organoids were treated with 500 nM rotenone for 24- and 72 hours and were then immediately collected for multiomic snRNA- and ATAC-sequencing.

B-C. Representative images of TH/FOXA2 and MAP2/FOXA2 immunohistochemistry in control organoids (B) and in organoids treated with rotenone for 72 hours (C), showing stress induced loss of TH+ cells and fibers.

D. PCA plot after subsetting DA neurons, colored by condition with the bottom trajectory corresponding to human cells and the top trajectory corresponding to chimpanzee cells.

E. Volcano plot of condition DEGs (average response in human and chimpanzee, FDR < 0.05) between control and 24 hours of rotenone treatment.

F. Top GO terms for 24 hours of rotenone treatment versus control ranked by the proportion of genes with FDR < 0.05.

G. Bar plots showing log2(fold change) for selected genes in each individual (dots) across the timecourse of rotenone treatment (normalized to control median expression across individuals within each species).

H. Heatmap showing log2(fold change) for 24 hours and 72 hours of rotenone treatment (average response in human and chimpanzee) versus control.

I. Heatmap for percentage overlap of eGRNs targets and upregulated or downregulated DEGs in human (top) and chimpanzee (bottom) under rotenone treatment in 24 and 72 hours in comparison to control. P values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test against overlap with other DEGs.

J. Violin plots summarize the distribution of Euclidean distances in PCA space (PC1–3) from control to rotenone timepoint centroids across individuals.

K. Scatterplot showing log2(fold change) between 24 hours of rotenone treatment and control in human versus chimpanzee for genes that were significant for the interaction of species and condition (FDR < 0.1) at 24 hours of rotenone treatment.

L-M. Bar plots showing log2(fold change) across the timecourse of rotenone treatment (normalized to control within each species) for examples of genes that were significant for the interaction of species and condition at 24 hours of rotenone treatment: MCU (L) and BDNF (M).

Scale bars: 200 μm.

GEX, gene expression; ATAC, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin; FDR, false discovery rate; CNTRL, no rotenone; 24H, 24 hours of rotenone treatment; 72H, 72 hours of rotenone treatment, Rot., rotenone

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

PCA of DA neuron transcriptomes revealed that responses to rotenone represented the major source of transcriptional variation along PC1 in both human and chimpanzee (Figure 7D), with early response genes, heatshock proteins, and cellular respiration genes marking increased rotenone responses (Figure S9H). Analysis of differential expression across the rotenone time course in both species using dreamlet revealed correlated (r = 0.87) responses at 24 and 72 hours (Figures 7E and S7I), enriched for GO terms associated with downregulation of neuronal functions such as axon guidance, neurotransmitter receptor activity, and synapses, consistent with previous studies28, and upregulated terms related to cellular respiration and ATP synthesis, possibly representing a compensatory response to electron transport chain inhibition70 (Figure 7F). Representative genes from the top categories showed generally conserved responses in human and chimpanzee (Figure 7G).

Next, we investigated candidate TFs driving gene expression shifts in response to oxidative stress in human and chimpanzee DA neurons. Using SCENIC+, we recovered 23 human and 13 chimpanzee eGRNs, with a median size of 51 regions and 47 genes (Table S6). Intersecting shared activator eGRNs between species with condition DEGs revealed a conserved trans-regulatory response upon rotenone treatment. Developmental TFs PBX1 and POU3F2 displayed reduced expression upon rotenone exposure at both time points and drove eGRNs enriched for downregulated genes in both species (Figures 7H and 7I). In addition, TFs BACH2 and CREB5, both upregulated under oxidative stress, also served a conserved role in driving eGRNs that were enriched for upregulated genes following rotenone exposure (Figures 7H and 7I). These results suggest that eGRN analysis can provide insight into upstream regulators of condition-dependent transcriptional responses and highlight a conserved stress-induced gene regulatory landscape.

We further examined species-specific responses to rotenone using the species-condition interaction term in our model. Overall, there was broad conservation in oxidative stress response genes and regulatory networks, but human DA neurons had slightly blunted responses compared to chimpanzee neurons, in terms of both up- and down-regulated gene sets (Figures S9J and S9K). To further investigate the differences in the magnitude of rotenone induced transcriptional responses, we calculated the Euclidean distance in PC space and measured the impact of the stress response across individuals30(Figures 7J and S9L). Remarkably, all 7 chimpanzee individuals showed stronger responses across a similar trajectory than all 8 human individuals at both the 24 hour and 72 hour timepoints, when cultured together in the same interspecies organoid environment.

In addition, we identified dozens of genes with species-specific responses (Figure 7K, Table S7). Two examples of qualitative species differences include human-specific reduction of Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter (MCU) (Figures 7L, S9M and S9N) and human induction of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) (Figures 7M, S9O and S9P), both of which are consistent with increased neuroprotective mechanisms in human DA neurons. Notably, eGRN analysis suggested a possible species difference in trans-regulation of BDNF that could underlie divergent responses. While developmental TFs PBX1, BACH1, and POU3F2 are the most highly ranked BDNF regulators in chimpanzee DA neurons, these TFs are ranked lower in human and instead NR4A2 and early response TFs JUNB and JUND play more prominent roles (Figure S9Q).

Together, these findings reveal a conserved trajectory of oxidative stress response governed by shared eGRNs, while highlighting candidate genes with human-specific divergence that may have therapeutic implications.

Discussion

The human DA system, even compared to that of our closest living ape relatives, more densely innervates larger target regions in the expanded human brain71. The molecular underpinnings driving these evolutionary changes and the consequences of the associated increase in bioenergetic demands remain unexplored. We hypothesized that the increased pressure on the human DA system may have necessitated adaptations in human DA neurons that could make them more resilient to cellular stress than the neurons of nonhuman primates in equivalent conditions. While these adaptations may be incomplete as suggested by increased human susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease over our longer lifespans, understanding potential protective mechanisms in human neurons could lay the foundation for future efforts to enhance or expand them with implications for disease treatment. Here, we established a phylogeny-in-a-dish approach, extending the concept of pooled iPSC culture systems27,30,72 by differentiating pooled midbrain cultures from 19 individuals across four primate species, facilitating the modeling of inter- versus intraspecies differences at baseline and in response to an oxidative stress challenge.

The gene expression landscape is highly dynamic during brain development, and the origin of connectivity differences between closely related primate species is unclear. To explore the extent and timing of human-specific gene expression patterns in DA neuron development, we sequenced progenitors and neurons from multiple timepoints, representing early stages of progenitor specification, neurogenesis and neuronal maturation. In immature DA neurons, the top categories of human-upregulated genes relate to the transport of mitochondria along axons/microtubules. This could reflect a strategy to meet the increased bioenergetic demands associated with the expanded axonal arborization of human DA neurons. Interestingly, ZFHX3 also shows a quantitative human-specific upregulation during this transient window and acts as a hub TF for an eGRN enriched for genes quantitatively upregulated in human DA neurons including MAPT, TUBB3, and NTM. ZFHX3 is expressed throughout the early developing brain and ZFHX3 haploinsufficiency is associated with intellectual disability73. Although its function is not yet established in DA neurons, ZFHX3 expression has previously been identified in a subset of high TH/SLC6A3-expressing DA neurons74. ZFHX3 is involved in differentiation75, cytoskeletal organization73, survival, and protection against oxidative stress in other neuronal subtypes75,76, suggesting that increased ZFHX3 expression may represent a consequential trans-regulatory change in developing human DA neurons. Additionally, several of the DEGs with the highest numbers of concordant linked DARs in DA neurons, including NRN1, are involved in neuron projection development. Together, these results reveal intriguing candidate genes that may be involved in promoting expanded DA neuron arborization and/or compensating for scaling-related consequences in the human brain.

The expanded innervation of human DA neurons likely increases metabolic demands related to the long-distance propagation of action potentials and the production of dopamine to supply the increased number of release sites4,17. Supporting the hypothesis that increased baseline oxidative stress is an important driver of gene expression divergence in humans, the top human-upregulated gene set in the most mature DA neurons in our dataset was related to antioxidant activity. This gene set included CAT, which encodes the hydrogen peroxide-degrading enzyme catalase. CAT was also found to be upregulated in human primary cortical tissue relative to chimpanzee and macaque50, supporting the relevance of our stem cell model to human evolution. In addition to catalase, genes encoding several members of the peroxiredoxin family of antioxidant enzymes, including PRDX2, PRDX3, PRDX4, and PRDX5, were also upregulated in human DA neurons. Interestingly, this gene family is markedly expanded and under positive selection in cetaceans, which has been suggested to protect against reactive oxygen species generated during diving-related hypoxia77. Both catalase and peroxidase activity have been found to be reduced in the brains of PD patients78. Overexpression of PRDX2 and PRDX5 decreases the toxicity of PD-inducing chemicals79,80, while silencing of PRDX5 results in increased sensitivity to rotenone-induced death81. While further studies are required to examine the functional consequences of the increased expression of these genes, our results build on theoretical proposals4,10 by demonstrating human-specific mechanisms that could protect DA neurons from increased oxidative stress.

The finding that protective mechanisms against oxidative stress display human-specific quantitative increases at time points corresponding to fetal stages motivated us to investigate whether induced oxidative stress could unmask additional species differences. While the response to rotenone was mediated by conserved eGRNs, there were also several notable differences. We observed a significantly blunted transcriptional response to rotenone in humans in every individual in our panel. At the level of individual genes, the expression of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter gene MCU was already lower in human at baseline, with expression further reduced upon rotenone exposure, while in chimpanzee the expression was increased. BDNF expression showed the opposite trend, with rotenone exposure resulting in reduced expression in chimpanzee but increased expression in human DA neurons. Both of these examples suggest an increase in neuroprotective mechanisms in human neurons. The deletion of MCU has been shown to be neuroprotective in both genetic and toxin-induced models of PD82,83, and MCU blockers prevent iron-induced mitochondrial dysfunction84. Neurotrophic BDNF is essential for the development of DA neurons, promotes DA neuron survival in animal models of PD and is reduced in the substantia nigra of patients with PD85–87. Indeed, delivery of neurotrophins, including GDNF and BDNF, is under study as a therapeutic option in PD87. However, it is still unclear whether rotenone-induced BDNF expression is truly human-specific since at least one study also found increased BDNF transcription but not protein levels in mouse DA neurons with chronic in vivo rotenone exposure88. Future studies will be needed to determine whether the altered transcriptional response to rotenone provides a functional neuroprotective effect in human DA neurons. Taken together, these observations provide additional support for the hypothesis that human DA neurons have mechanisms for enhanced buffering of oxidative stress, both at baseline and following perturbation

This study opens questions related to the functional implications of the molecular changes that we identify. How does the genetic manipulation of candidate genes or regulatory elements with human-specific expression or accessibility affect intrinsic features of DA neurons such as axonogenesis, firing rate, dopamine release, and response to oxidative stress? While the diversity of our iPSC-derived midbrain cultures allowed us to study cell type-specific patterns of gene expression and regulation, this heterogeneity poses challenges for functional interrogation. Future experiments with CRISPR-mediated knockdown or inactivation in isogenic lines will be needed to dissect the contributions of individual genes and regulatory elements, and multimodal readouts will be essential. Transplantation of DA neurons into rodent models, where endogenous innervation patterns and connectivity can be recapitulated33,89 could allow studies of cell-intrinsic species differences in arborization and candidate gene function in more mature DA neurons.

Since the divergence of human and chimpanzee from a common ancestor, the human brain has evolved in both size and function, and in the susceptibility to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases90. Many of these disorders involve the DA system, either directly through a progressive degeneration of DA neurons (PD), or as part of DA signaling dysregulation (e.g. autism spectrum disorder91, schizophrenia92, bipolar disorder93). By gaining molecular knowledge of what sets the human DA system apart from that of our closest extant relatives, we can advance our understanding of the origins of human-enriched disorders, and identify new therapeutic targets and strategies for drug development. In addition, while stem cell based cell replacement therapy for PD is currently in clinical trials as a potential restorative treatment strategy, there are still open questions related to the long-term viability of the transplanted neurons94. Our dataset represents a resource of tolerated interspecies variation that could be mined for candidate genes whose manipulation could improve the innervation, function, and/or survival of DA neurons in cell replacement paradigms.

Limitations of the study

While we used state-of-the-art protocols to pattern and mature midbrain neurons31, the cell types studied here are still relatively immature (corresponding to mid to late fetal stages). The DA neuron subtype identity is not yet fully refined at fetal timepoints74,95, and we do not yet see separation of subtype-specific markers between different single cell clusters96, preventing conclusions about subtype-specific differences. Furthermore, while rotenone exposure allows us to simulate conditions of oxidative stress that might occur in the aging brain, it is unclear how context-dependent responses to oxidative stress might differ in fetal versus aged neurons. Future studies could integrate strategies to accelerate neuronal maturation44 or simulate aging97 to improve the maturity and relevance of these cell populations to human neurodegenerative disease. While we established a clear correlation between species differences in RNAseq data from primary tissue and in our organoid model, the limited availability and quality of primary tissue samples made it difficult to validate these results with orthogonal methods.

We chose to maximize statistical power by combining cells from inter- and intraspecies pools in our analysis. While the majority of human and chimpanzee DA neurons (human: 64.0%, chimpanzee: 75.1%) were derived from interspecies pools and gene expression was highly consistent across pool types (Figure 2J, S5C–D), pointing to the contribution of cell-intrinsic factors, future work will be needed to clarify the relative contributions of cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic influences to the human-specific patterns of gene expression and regulation we have identified. In addition, glia were mostly lacking in our organoid models, and they may be an important source of cell-extrinsic species differences98,99 and influence disease susceptibility100. Finally, locally supplied dopamine in DA target structures could represent an additional compensatory mechanism beyond those discussed here that could offset the increased demand for dopamine secretion in the human brain71.

Resources

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Alex A. Pollen (Alex.Pollen@ucsf.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Sequencing data are deposited on GEO accession number GSE292438

Processed data available in browsable format: https://cells.ucsc.edu/?ds=xsp-dopa-organoids

-

Original code is publicly available and can be found here:

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

STAR Methods

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Pluripotent stem cell lines

Human, chimpanzee, orangutan, and macaque pluripotent stem cell lines104–109 were maintained on recombinant human laminin-521 (0.6–1.2 μg/cm2, BioLamina) in StemMACS™ iPS-Brew XF medium (Miltenyi Biotec). The cells were passaged with EDTA (0.5 mM) every 3–4 days at a ratio of 1:6–1:12 for human, chimpanzee and orangutan lines and 1:15–1:30 for the macaque lines. When passaged, the pluripotent cells were seeded into StemMACS™ iPS-Brew XF medium supplemented with 3 μM Thiazovivin for 2–5 hours to improve the recovery. The cells were tested and confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma.

Primary midbrain samples

Macaque midbrain tissue was obtained for the developmental time points PCD40, PCD65 (n=2), PCD80 (n=2) and PCD90 from the Primate Center at the University of California, Davis. Cortical samples from the same fetal brains have previously been analyzed in Schmitz et al.110. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Davis and all procedures were performed in accordance with the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act. Additional macaque data from PCD110 (n = 2) were taken from Zhu et al.111. One sample of de-identified human tissue was collected at GW23 with previous patient consent in strict observance of legal and institutional ethical regulations in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocols were approved by the Human Gamete, Embryo, and Stem Cell Research Committee and the Committee on Human Research (institutional review board) at the University of California, San Francisco. Additional first trimester human first midbrain data were taken from Eze et al.43 and Braun et al.42

METHOD DETAILS

Nutlin-3a sensitivity assay to determine p53 status

To exclude any cell lines with aberrant p53 expression, most of the lines included (with the exception of H21194, O11045–4593 and LYON-ES1) were screened in a Nutlin-3a sensitivity assay, as described previously112–114. In brief, pluripotent cells were passaged with EDTA (0.5 mM) at 1:3 and plated without rock inhibition in stem cell medium containing 10 μM Nutlin-3a (Selleck Chemicals). In pluripotent lines with a normal p53 status, this resulted in cells undergoing apoptosis within 24 hours.

Generation of pooled cultures of ventral midbrain progenitors

Prior to starting the differentiation, all pluripotent stem cell lines were cultured separately. To initiate the differentiation, the cells were dissociated with EDTA and counted in order to add an equal number of cells from each line to the pooled cultures. For ventral midbrain induction and cryopreservation of the ventral midbrain progenitors, the protocol described in Nolbrant el al., 201731 was used. In brief, pooled pluripotent stem cells were seeded at 12,500 cells/cm2 (312,500 cells/T25 flask) onto recombinant human laminin-111 in N2 medium with dual SMAD inhibition (10 μM SB431542 + 100 ng/ml Noggin) from day 0–9. To obtain the correct ventral and rostro-caudal identity, 300 ng/ml SHH-C24II and 0.4–0.8 μM CHIR009921 were added between day 0–9 (when culturing the macaque lines individually a CHIR009921 concentration of 0.2–0.4 μM was used). To finetune the patterning of the ventral midbrain progenitors, 100 ng/ml FGF8b was added to the medium from day 9. On day 11, the early midbrain progenitors were passaged and replated at high density (800,000 cells/cm2). Between day 11–16, the cells were maintained in B27 medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml BDNF, 200 μM Ascorbic acid (AA) and 100 ng/ml FGF8b. The identity of the progenitors was determined by immunocytochemistry on day 14, before the cells were cryopreserved on day 16, or directly assembled into ventral midbrain organoids. For a complete list of differentiation experiments in this study, refer to Table S2.

Generation of ventral midbrain organoids

To generate ventral midbrain organoids, 10,000 day 16 progenitors were seeded into each well of a U-bottom ultra-low attachment 96-well plate. The organoids were cultured in organoid maturation media containing Neurobasal supplemented with 1x B27, 1x GlutaMAX, 1x MEM NEAA, 20 U/mL Pen-Strep, 55 μM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 20 ng/ml BDNF, 200 μM AA, 10 ng/ml GDNF and 500 μM db-cAMP115. For the initial seeding, 10 μM Y-27632 was also added. Two-thirds of the media was changed every 2–3 days and the organoids were moved to ultra-low attachment 6-well plates on day 40, with 10 organoids per well. During the first round of long term maturation it became apparent that one human line (H28834) kept proliferating over an extended time and that it at day 100 predominantly gave rise to a dorsal midbrain-hindbrain progenitor cell that was characterized by the expression of PAX3/7 and ZIC1. To optimize the maturation and limit the expansion of these dorsal progenitors, we used organoid maturation media supplemented with 10 μM DAPT from day 40 in subsequent maturation experiments (Rotenone challenge experiment, Outgroup experiment, see Table S2).

There are several keys to our success of making multi-individual interspecies organoids. First, we screened the cells for p53 function to remove lines that would have an obvious growth and survival advantage and that might bias the results from the rotenone vulnerability assay and lead to false conclusions. Second, by using a highly efficient protocol for neuronal induction in 2D we push the cells to differentiate into midbrain progenitors. This allows us to mix up to 17 individuals at the pluripotency stage and generate pools of neuronal progenitors that can be assembled into 3D spheres for neuronal maturation. Third, at day 40, we introduce a new method to overcome imbalances, optimizing the media composition by testing different combinations of small molecules to promote cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation.

Immunochemistry