Abstract

Chyloperitoneum (CP) is a rare complication after bariatric surgery. We present a 37-year-old female with CP caused by a bowel volvulus following a gastric clipping with proximal jejunal bypass for morbid obesity. An abdominal CT image of a mesenteric swirl sign and abnormal triglyceride level of ascites fluid can confirm the diagnosis. In this patient, laparoscopy demonstrated dilated lymphatic ducts caused by a bowel volvulus resulting in the exudation of chylous fluid into the peritoneal cavity. After the reduction of bowel volvulus, she made an uneventful recovery with complete resolution of the chylous ascites. The presence of CP could indicate a situation of small bowel obstruction in patients with a history of bariatric surgery.

Keywords: Bowel volvulus, chyloperitoneum, gastric clipping, proximal jejunal bypass

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary bariatric operations provide several advantages, including sustained weight loss, as well as the improvement of obesity-related comorbidities and better quality of life. However, all bariatric procedures are associated with some nutritional and procedural-related problems. Chyloperitoneum (CP) is an abnormal lymphatic effusion in the peritoneal cavity caused by a great number of aetiologies. In developed countries, abdominal malignancy and cirrhosis account for over two-thirds of all cases, whereas infectious diseases, including tuberculosis and filariasis, are responsible for the majority of cases in developing countries. Other causes of CP include congenital, inflammatory, post-operative, traumatic and miscellaneous disorders. CP is an uncommon complication after bariatric surgery and has not been described in patients after gastric clipping with proximal jejunal bypass (PJBGC).[1,2,3] We intend to report the diagnostic findings and the clinical course of such a case.

CASE REPORT

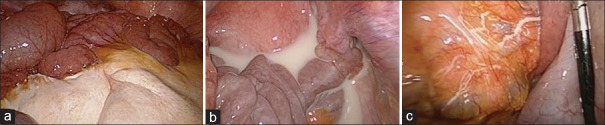

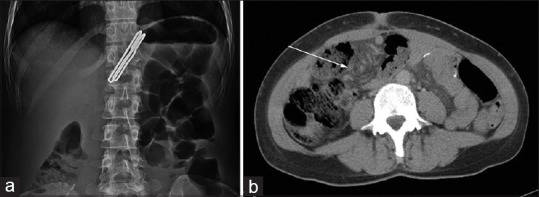

A 37-year-old female presented to our emergency department with severe right upper abdominal pain followed by nausea and vomiting for 1 day. She has undergone bariatric surgery of PJBGC at another hospital 7 years previously [Figure 1a]. Following the surgery, her body weight decreased from 123 kg to 71 kg with a final body mass index of 28. On arrival, she was vitally stable (pulse – 66 bpm, blood pressure – 135/70 mmHg and temperature – 36.7°C). Laboratory tests were unremarkable, with C-reactive protein of 0.02 mg/L, white count of 4780/μL and haemoglobin of 11.4 g/dl. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) reported a swirl sign of mesentery twisting and peritoneal effusion [Figure 1b]. She was sent to the operating room with high suspicion of bowel volvulus. On laparoscopy, a massive segment of white-stained mesentery and a large amount of milky ascites in the peritoneal cavity were found [Figure 2a and b], along with a mesenteric torsion around the jejunoileal anastomosis. Prominent dilatation of the subserosal lymphatic duct was also observed in the proximal mesentery [Figure 2c]. The mesenteric torsion was corrected. The entire segment of the intestine appeared to be viable after reduction and no bowel resection was required. Examination of the peritoneal fluid demonstrated high triglyceride content of 726 mg/dL, free from any microbes or inflammatory cells, supporting the diagnosis of chylous ascites. The patient made an uneventful recovery after surgery and was discharged with the absence of the milky ascites 5 days later. She has remained well without any episode of abdominal pain 1 year after hospital discharge.

Figure 1.

(a) Abdominal film showing a metallic gastric clip at the gastroesophageal region. (b) Abdominal CT showing the swirl sign of the mesentery (arrow). CT: Computed tomography

Figure 2.

(a) Laparoscopy showing a massive segment of the whitish mesentery. (b) Laparoscopy demonstrating milky fluid in the pelvic cavity. (c) Laparoscopy revealing dilated subserosal lymphatic ducts of the mesentery

DISCUSSION

CP is usually caused by internal hernia (IH) with small bowel obstruction following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and only 38 cases have been published in the literature.[3] However, the diagnosis of IH is challenging since it can cause an increase in cholestatic or pancreatic enzymes, mimicking choledocholithiasis/pancreatitis or other abdominal pathologies.[3] PJBGC, being a modified proximal jejunal bypass surgery, itself is a rarely performed bariatric procedure; hence, its complications would be even rare.[2] Unlike IH complicating Roux-en-Y gastric bypass,[3] or direct lymphatic disruption in sleeve gastrectomy,[3] bowel volvulus around the jejunoileostomy might have caused occlusion of the lymphatic channels, resulting in exudation of chylous fluid from the dilated subserosal lymphatic system into the peritoneal cavity in this patient. We believe that the laparoscopic demonstration of marked dilatation of the subserosal lymphatic duct without visualised leaking flow supports this hypothesis.

Surgical complications might arise from different bariatric techniques during early or late postoperative periods inpatient cases. CP is one of the postoperative complications and the investigation of its underlying causes is of great challenge. The investigation of its underlying causes is of great challenge. Abdominal CT is most essential and useful for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal pathology after surgery;[4] in addition, laparoscopy and laboratory examination of ascites fluid could help to confirm the diagnosis of CP. In the present patient, neither a Peterson nor a mesenteric defect causing an IH was identified.

In general, treatment modalities for CP are targeted to resolve the underlying causes, and surgical intervention is reserved for patients with mechanical bowel obstruction or conservative therapy failure.[1,3,5] It is postulated that in CP patients caused by IH after gastric bypass, the mesenteric arteries and veins of high flow remained patent, although the lymph vessels with the low-pressure flow were occulted by loose volvulus leading to lymph leakage.[1] None of them presented with any sign of bowel ischaemia, such as congestion, infarction, necrosis or perforation of the small intestine, warranting a bowel resection. Moreover, chylous ascites is reported to quickly resolve after correction of the obstruction, as shown in our patient.[1,3,5] Recent reports also demonstrate that the prognosis of CP in bariatric patients is favourable if the diagnosis is made promptly and treated promptly.[1,3,5] The presence of CP could reasonably serve as an indicator of chronic small bowel obstruction with possible viability in patients following bariatric surgery.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but please confirm.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harino Y, Kamo H, Yoshioka Y, Yamaguchi T, Sumise Y, Okitsu N, et al. Case report of chylous ascites with strangulated ileus and review of the literature. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:186–92. doi: 10.1007/s12328-015-0573-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen C, Tsai WT, Pan HM, Hsu KF. Revisional sleeve gastrectomy after failed gastric clipping for obesity: Report of two cases and review of literature. J Minim Access Surg. 2022;18:463–5. doi: 10.4103/jmas.jmas_229_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakran N, Parmar C, Ahmed S, Singhal R, Madhok B, Stier C, et al. Chyloperitoneum and chylothorax following bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Obes Surg. 2022;32:2764–71. doi: 10.1007/s11695-022-06136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacobellis F, Dell’Aversano Orabona G, Brillantino A, Di Serafino M, Rengo A, Crivelli P, et al. Common, less common, and unexpected complications after bariatric surgery: A pictorial essay. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12:2637. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12112637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weniger M, D’Haese JG, Angele MK, Kleespies A, Werner J, Hartwig W. Treatment options for chylous ascites after major abdominal surgery: A systematic review. Am J Surg. 2016;211:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]