Abstract

MINER is web-based software for phylogenetic motif (PM) identification. PMs are sequence regions (fragments) that conserve the overall familial phylogeny. PMs have been shown to correspond to a wide variety of catalytic regions, substrate-binding sites and protein interfaces, making them ideal functional site predictions. The MINER output provides an intuitive interface for interactive PM sequence analysis and structural visualization. The web implementation of MINER is freely available at http://www.pmap.csupomona.edu/MINER/. Source code is available to the academic community on request.

INTRODUCTION

Because of the exponential growth of available sequence data, the development of accurate computational strategies for functional site identification has become one of the most important post-genomic challenges (1). Many methods attempt to predict functional sites from sequence alone. Highly conserved positions within sequence alignments are strong candidates for functional sites. Although attractive owing to their relative simplicity, conservation-based approaches frequently result in too many false positives to be satisfactory. In addition, sequence regions with significant variability can also be critical to function, especially when their composition may define subfamily specificity. Frequently, these regions correspond to residues that are critical in molecular recognition and binding specificity.

In this report, we present MINER, software for phylogenetic motif (PM) identification. PMs are sequence alignment regions that conserve the overall phylogeny of the complete family. Through comparison with structural and biochemical data, we have shown that PMs represent good functional site predictions in a wide variety of protein systems (2). Our results indicate that, despite little overall proximity in sequence, PMs are structurally clustered around key functionality across a wide variety of structural examples. PMs correspond to a variety of structural features, including solvent exposed loops, active site clefts and buried regions surrounding prosthetic groups (Figure 1). Our results also indicate that PMs are generally conserved in sequence, indicating that PMs tend to be motifs in the traditional sense. Consequently, PM results bridge evolutionary (3–5) and traditional motif (6,7) approaches. In spite of the small alignment window size, PM tree significance has been demonstrated using bootstrapping.

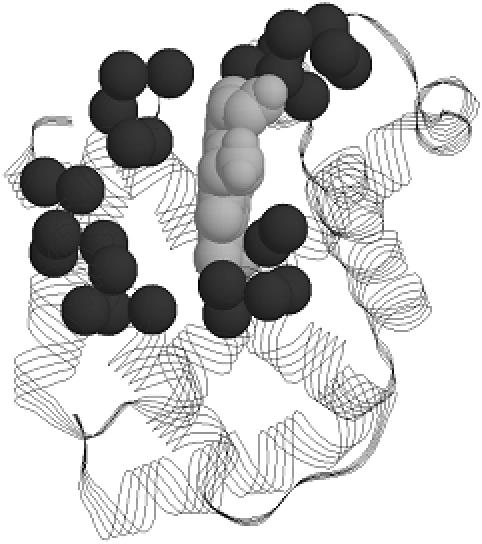

Figure 1.

The four best-scoring (PSZ threshold = −1.5) PMs identified from the myoglobin protein family are mapped onto structure (pdbid: 1MBA). The α-carbons of the PMs are shown as black spheres; the heme is shown in gray.

IMPLEMENTATION

MINER takes as an input any multiple sequence alignment (MSA). If sequences are unaligned, MINER will align them for the user by using ClustalW (8). A sliding sequence window algorithm is used to quantitatively evaluate the phylogenetic similarity between each sequence region and the whole sequence. Distance-based trees are calculated both for the whole alignment and each window. Phylogenetic similarity is based on tree topology, which is calculated using the partition metric algorithm (9). The partition metric counts the number of topological differences between the two trees. Partition metric values are recast as Z-scores. Overlapping sequence windows scoring past some preset phylogenetic similarity Z-score (PSZ) threshold are identified as PMs. Empirically, we have determined that a window width between 5 and 10, and a PSZ threshold between −1.5 and −2.2 (lower scores indicate greater similarity) represent ideal default parameters for functional site prediction. MINER allows the user to easily change these parameters as desired. By default, alignment positions with >50% gaps are eliminated (masked). However, the user retains the option to handle gaps as described previously (2).

MINER can now automatically determine the PSZ threshold without human subjectivity. The automated algorithm relies on significant raw data preprocessing to improve signal detection. Subsequently, Partition Around Medoids Clustering of the similarity scores assesses those sequence fragments whose annotation remains in doubt. The accuracy of the approach has been confirmed through comparisons with our manual results (2,10). A preprint more thoroughly describing the automated algorithm is available at the MINER website. With the automated algorithm in hand, we have precomputed all PMs for the most recent version of the COG database (11). These results are also available at the MINER website.

MINER is available as standalone (command-line based) software and through the Web via a user-friendly interface. The standalone version is written in PERL and can be easily modified. A CGI facade is implemented over the standalone version for ease of use. After the web-based calculation is complete, MINER sends an email with a hyperlink directing the user to their results. The user has 1 week to access and download their outputs. MINER is part of the larger Protein Motif Analysis Portal at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (12).

INPUT

MINER requires a minimum of five sequences in the FASTA format. However, we recommend using 25 or more sequences to ensure sufficient evolutionary diversity. With the exception of gaps, all non-alphabetic characters found in the input will be purged. Optionally, a Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure may be submitted to better highlight PM regions. MINER will automatically add the PDB sequence to a dataset of unaligned sequences if it does not exist. However, user-provided alignments must already include the PDB sequence as part of the alignment.

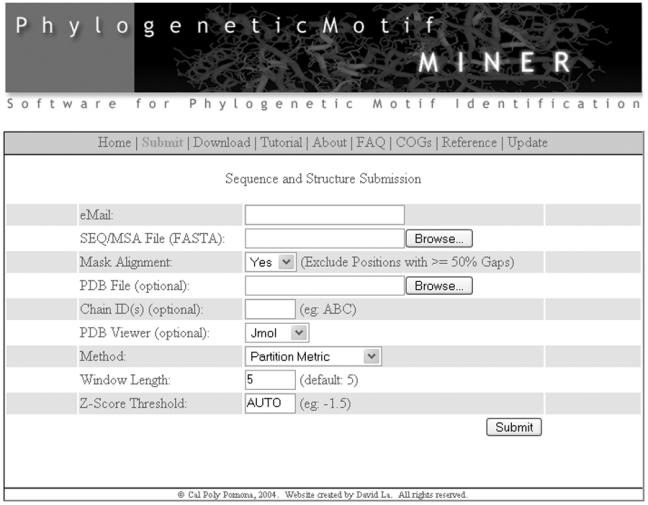

There are several default MINER options that can be customized before submission (Figure 2). Enabling the masking feature will purge alignment positions with >50% gaps. Although masking is optional, we find that eliminating these positions significantly increases the quality of functional site predictions, especially in more divergent families. MINER also provides three methods for identifying motifs. By default, MINER identifies functional sites as described above. Alternatively, MINER also provides the option to identify traditional motifs using the False Positive Expectation (FPE) of a regular expression or profile. Both approaches are described in detail within the tutorial at the MINER website. When used in conjunction with the PM results, these alternative approaches often provide synergistic information. In addition, the width of the sliding window can also be modified. By default, the width is set to five alignment positions, which we find it to be ideal for identifying functional sites (2). However, large windows are more appropriate when exploiting ‘motif-ness’ (e.g. using PMs to de-ORFan uncharacterized sequences). The Z-score threshold is automatically determined by default, but can be manually set any value ≤−1. Finally, either Jmol (default) or Chime viewers can be used for interactive structure visualization.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the MINER input page.

OUTPUT

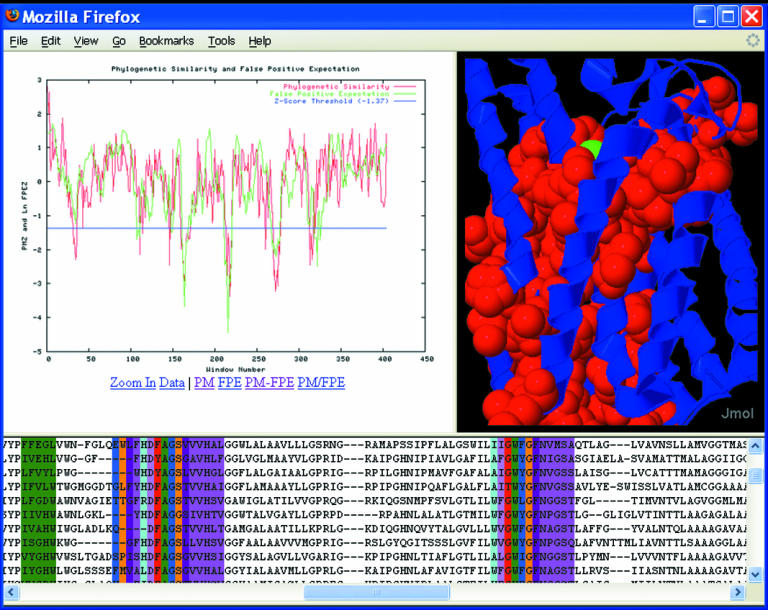

The MINER output is a framed HTML file (Figure 3) that provides (i) phylogenetic similarity versus window number plots, (ii) an annotated structure and (iii) an annotated MSA. PM regions in the PDB structure are annotated by writing the PSZ to the temperature factor column. Furthermore, interactive structural visualization of the identified PMs is achieved with the option of using either Jmol or Chime. Each PM within the alignment is hyperlinked such that clicking it will highlight the corresponding structural region. PM sequence logos, generated by WebLogo (13), are also hyperlinked from the MSA. In all cases, the raw data are available for easy export to auxiliary programs. With the masking feature enabled, regions of the MSA colored light gray represent alignment positions that have been purged before PM identification. At the MINER website, a full tutorial and frequently asked questions page is provided. The tutorial guides one through the output of triosephosphate isomerase results, which is the center of discussion in our previous reports (2,10).

Figure 3.

Screenshot of the MINER output applied to the ammonia channel. The sequence window (which can toggle between aligned and ungapped) is hyperlinked to the structure viewer and WebLogos. The upper-left window can toggle between both PM (red) and FPE (green) results. In all cases, the raw data are easily accessible for export.

CONCLUSIONS

MINER is a convenient web-based program for PM discovery. MINER utilizes a sliding sequence window algorithm to systematically evaluate all regions of an MSA input. Phylogenetic similarity is determined by comparing tree topology, which is calculated using the partition metric algorithm consequently resulting in a PSZ value. The sensitivity in the PM identification is constrained using a PSZ threshold, which is automatically determined by default. The resulting MINER output uses Jmol or Chime PDB viewers allowing protein structure and corresponding PM regions to be interactively visualized. The standalone version of MINER is freely available for academic download on request.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a grant from the American Chemical Society-Petroleum Research Fund (36848-GB4). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the College of Science at California State Polytechnic University.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones S., Thornton J.M. Searching for functional sites in protein structures. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La D., Sutch B., Livesay D.R. Predicting protein functional sites with phylogenetic motifs. Proteins. 2005;58:309–320. doi: 10.1002/prot.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armon A., Graur D., Ben Tal N. ConSurf: an algorithmic tool for the identification of functional regions in proteins by surface mapping of phylogenetic information. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:447–463. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.del Sol M.A., Pazos F., Valencia A. Automatic methods for predicting functionally important residues. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1289–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtarge O., Bourne H.R., Cohen F.E. An evolutionary trace method defines binding surfaces common to protein families. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;257:342–358. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu A.H., Zhang X., Stolovitzky G.A., Califano A., Firestein S.J. Motif-based construction of a functional map for mammalian olfactory receptors. Genomics. 2003;81:443–456. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puntervoll P., Linding R., Gemund C., Chabanis-Davidson S., Mattingsdal M., Cameron S., Martin D.M., Ausiello G., Brannetti B., Costantini A., et al. ELM server: a new resource for investigating short functional sites in modular eukaryotic proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3625–3630. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penny D., Hendy M. The use of tree comparison metrics. Syst. Zool. 1985;34:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livesay D.R., La D. The evolutionary origins and catalytic importance of conserved electrostatic networks within TIM-barrel proteins. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1158–1170. doi: 10.1110/ps.041221105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatusov R.L., Natale D.A., Garkavtsev I.V., Tatusova T.A., Shankavaram U.T., Rao B.S., Kiryutin B., Galperin M.Y., Fedorova N.D., Koonin E.V. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La D., Silver M., Edgar R.C., Livesay D.R. Using motif-based methods in multiple genome analyses: a case study comparing orthologous mesophilic and thermophilic proteins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8988–8998. doi: 10.1021/bi027435e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crooks G.E., Hon G., Chandonia J.M., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]