Abstract

MovieMaker is a web server that allows short (∼10 s), downloadable movies of protein motions to be generated. It accepts PDB files or PDB accession numbers as input and automatically calculates, renders and merges the necessary image files to create colourful animations covering a wide range of protein motions and other dynamic processes. Users have the option of animating (i) simple rotation, (ii) morphing between two end-state conformers, (iii) short-scale, picosecond vibrations, (iv) ligand docking, (v) protein oligomerization, (vi) mid-scale nanosecond (ensemble) motions and (vii) protein folding/unfolding. MovieMaker does not perform molecular dynamics calculations. Instead it is an animation tool that uses a sophisticated superpositioning algorithm in conjunction with Cartesian coordinate interpolation to rapidly and automatically calculate the intermediate structures needed for many of its animations. Users have extensive control over the rendering style, structure colour, animation quality, background and other image features. MovieMaker is intended to be a general-purpose server that allows both experts and non-experts to easily generate useful, informative protein animations for educational and illustrative purposes. MovieMaker is accessible at http://wishart.biology.ualberta.ca/moviemaker.

INTRODUCTION

Protein structures are not static. Indeed, proteins vibrate, twist, bend, open, close, assemble and disassemble in a variety of ways over many different time scales. Protein motions and conformational accommodation actually lie at the heart of many important protein–ligand interactions, including protein–DNA binding (1), enzyme–substrate interactions (2), muscle contraction (3) and oligomerization (4). Owing largely to the continuing developments of X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy and computational molecular dynamics (MD), the temporal and spatial scales involved in protein motions are now becoming better understood (5). Small-scale (<1.0 Å) motions over short periods of time (picoseconds) can be modelled or measured using either X-ray thermal B factors (6), NMR order parameters (7) or shorter (<1 ns) MD simulations. Mid-scale motions (1.0–4.0 Å) tend to take place over longer periods of time (hundreds of picoseconds to nanoseconds) and can be discerned by comparing NMR structure ensembles, looking at the X-ray structures of different crystal isomorphs or running long (10–100 ns) MD simulations. Large-scale motions (5–30 Å), which may take microseconds to complete, are typically evident only by comparing two different states or experimentally determined structures of the same molecule (say, bound and unbound). These motions cannot normally be modelled via MD.

The fact that molecular motions play such an important role in protein function underlies the growing need to be able to illustrate or visualize these motions in an informative manner. Several commercial MD packages allow molecular ‘movies’ to be screen-captured and displayed via standard computer presentations. However, relatively few biologists are familiar with, nor do they have the expertise to use, these relatively sophisticated and expensive software tools. Likewise, not all motions (especially some of the more interesting or larger-scale ones) can be captured using off-the-shelf MD simulations.

More recently, Mark Gerstein at Yale University has developed an excellent and easy-to-use web server (the Morph server) which allows non-expert users to animate and visualize certain types of protein motions through the generation of short movies (8). This tool specifically models larger-scale motions or ‘morphs’ by interpolating the structural changes between two different protein conformers and generating a set of plausible intermediate structures. A hyperlink pointing to the morph results is then emailed to the user. The primary focus of the Morph server has been to facilitate research into, analysis and classification of different kinds of large-scale molecular motions of monomeric proteins. As such it is not intended to be a general molecular animation tool capable of simulating all aspects of macromolecular motion such as folding/unfolding, docking, oligomerization, multimeric protein motions, vibrational motions and structural ensemble motions. For instance, the Morph server offers only limited user control over rendering, animation parameters, colour and point of view. Likewise, the methods used to generate the movies are computationally intensive and can require up to 1 h of CPU time before completion. Furthermore, the Morph server does not allow the modelling of motions from a single input structure or from more than two input structures. This is somewhat limiting if one is interested in modelling motions from NMR structure ensembles or if one has only a single X-ray structure of a given protein. Additionally, the Morph server does not support the visualization of other kinds of protein motions, such as folding/unfolding, or of docking and self-assembly events involving two or more structures.

Here we wish to describe a general molecular animation server that allows a wide range of motions and dynamic events to be animated and offers a much greater range of user control over rendering and animation parameters. This server, called MovieMaker, allows small-, medium- and large-scale motions to be rendered using as few as 1 and as many as 50 input structures. It allows users full control over the rendering style, molecular colouring scheme, background, point of view, rotation rate and animation quality. It also employs a simplified Cartesian coordinate interpolation approach coupled with an intelligent superposition algorithm that allows most kinds of molecular movies to be rendered automatically in less than 1 min. Unlike any other animation tool that we are aware of, MovieMaker also allows users the option of creating movies of protein folding/unfolding as well as molecular docking or self-assembly (oligomerization) of two or more molecules. Rather than being a specialized analytical tool, the main purpose of MovieMaker is to quickly and conveniently generate realistic, downloadable animations of protein motions that can be used by non-specialists for a variety of educational or instructive purposes.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

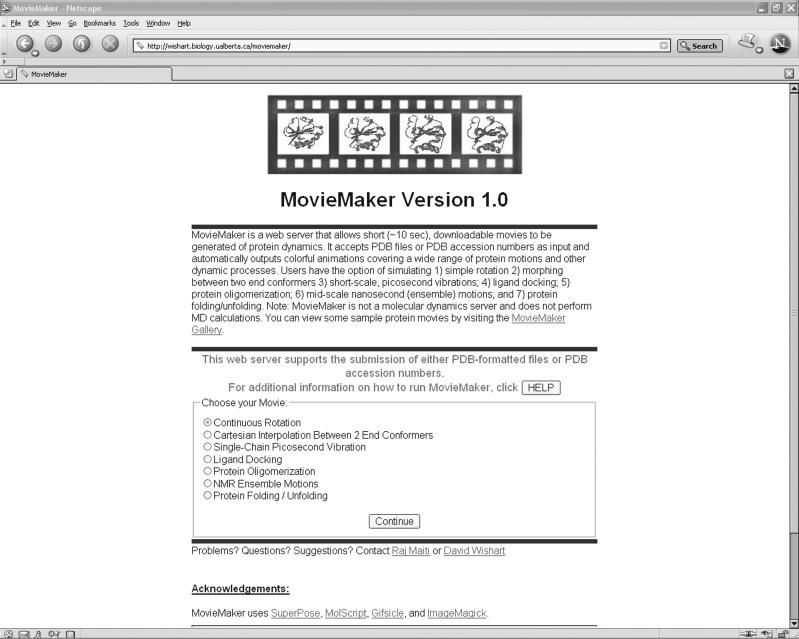

MovieMaker supports seven kinds of animations: (i) simple rotation, (ii) morphing between two end-state conformers, (iii) small-scale vibrations, (iv) small molecule docking, (v) self-assembly or oligomerization, (vi) mid-scale (structure ensemble) motions and (vii) protein folding/unfolding. The type of animation is dependent on both the input data and the type of animation selected by the user from a pull-down menu box. The MovieMaker home page presents the user with the type of movie choices that one can generate (Figure 1) along with an extensive gallery illustrating the types of motions that can be modelled. Upon selecting the appropriate movie type, the user is presented with input boxes for file uploads and various display options. The input for all MovieMaker animations is one or more PDB-formatted files containing one or more protein structures. These can be directly uploaded to MovieMaker using the file selector boxes or alternatively one or more PDB accession numbers can be provided and the program will automatically retrieve the appropriate PDB files from the RCSB website (9).

Figure 1.

A screenshot of the MovieMaker home page showing the different animation options.

The simplest motion to render in MovieMaker is a basic rotation. The rotation animation is intended to allow all sides of a given structure to be conveniently and continuously viewed. Once the rotation option is selected, only a single PDB file needs to be provided. If multiple structures are found in a single PDB file, the program either treats the ensemble as a single oligomeric structure or the user can select a single chain from that file. To generate the rotation animation, MovieMaker takes the input file and applies a series of standard x, y or z axis rotations to the structure(s). Users have the option of changing the speed and extent of the rotation by adjusting the number of frames in the animation (the default is a rotation of 360° in 10° increments). Additionally, through the viewing options section located below the data entry section, users may change the orientation of the molecule (by rotating along the x, y or z axes), the molecular rendering style (backbone, CPK, ball-and-stick, ribbon), molecular content (backbone only, all atoms, selected side-chains), image size and molecular colour (by secondary structure, rainbow, by chain, single uniform colour). All renderings are performed using the molecule visualization program MOLSCRIPT (10). Another freeware program called gifmerge (http://www.lcdf.org/gifsicle/) is then used to string the output images from MOLSCRIPT to create an animated GIF. This animated GIF is looped continuously to provide a smooth visualization of the rotation process. The animations are instantly viewable on the user's web browser and may be saved by right-clicking on the animation image and selecting ‘save file’ or ‘save image’. A typical movie file is ∼500 kB. MovieMaker also generates a downloadable set of PDB text files that users can use to generate specific images or regenerate animations using their own molecular rendering software.

Small molecule docking requires only a single PDB file containing two or more molecular entities that are already bound. Once the small molecule docking option is selected, the MovieMaker program automatically parses the input file and identifies all molecular entities (small molecules and protein chains). Users must then select one protein entity and one small molecule entity. To generate a pre-docking or two-component state, MovieMaker then calculates the centre of masses for the protein alone, the small molecule alone and the complex together. A vector is then drawn from the complex's centre of mass to the small molecule's centre of mass. This vector defines the direction that the small molecule entity must move in to create a pre-docking state. To generate a pre-docking state, the small molecule is translated 15 Å along this vector and randomly rotated (between 15° and 60°) about its individual x, y and z axes. MovieMaker then calculates a series of intermediate positions by incrementally rotating and translating the small molecule until it reaches its original bound position. The default increment is 1/20 of the original translation/rotation. As with the rotation option, users have full control over colouring, point of view and rendering styles. Note that the small molecule can be rendered (CPK, ball-and-stick) and coloured in a variety of ways.

Oligomerization and self-assembly are handled in a very similar manner to small molecule docking. As with docking, only a single PDB file containing two or more macromolecules is required. However, when the self-assembly option is selected all macromolecular entities within the PDB file will be separated and reassembled. Users do not have the option to select a subset of molecules that are to be assembled or docked. The same centre of mass calculations, direction vector calculations, rotations and translations are repeated for all subunits in the oligomer to create a preliminary disassembled state. The complex is reassembled using the reverse rotation and translation operations. Note that both the docking and oligomerization animations are inherently ‘rigid’ dockings. No internal motions are currently generated for the interacting proteins or ligands.

When MovieMaker's small-scale or vibrational motions option is selected only a single PDB file (containing a single chain) is needed. The key trick to most of MovieMaker's motion generation is to use Cartesian coordinate or torsion angle interpolation between a ‘perturbed’ state and a ‘ground’ state conformation. In Cartesian interpolation the intermediate positions between two states or positions are calculated in a linear fashion based on the coordinates between the two end-points and a chosen increment. The resulting images therefore depict a pathway that two conformers can take when morphing from one to the other. To create a perturbed state, MovieMaker generates random displacements of the x, y and z coordinates of between 0.0 and 1.0 Å for all heavy atoms in the original PDB file according to the magnitude of their corresponding B factors. Specifically, the ad hoc formula B = 100(|Δx| + |Δy| + |Δz|) is used to calculate the x, y and z atomic displacements. If no B factors are present in the file a default value of 60 is used. These perturbed structures are then rendered and infinitely looped to create the illusion of a long-term MD simulation.

When the structural ensemble motion option is selected, users must provide a PDB file containing two or more copies of the same protein molecule. This can include an NMR structure ensemble (typically 20–40 structures) or multiple copies (2–10) of the same protein in a single unit cell from a standard X-ray structure. If the molecules are not identical, MovieMaker will provide a warning and cancel the rendering operation. MovieMaker uses a recently developed superpositioning tool called SuperPose (11) to intelligently and automatically compare, rank and superimpose all structures in the ensemble or unit cell. Moving from the most similar pair to the least similar remaining pair of superimposed structures in the ensemble, Cartesian coordinate interpolation is performed to generate a series of intermediate structures. MovieMaker automatically takes into account the number of structures in the ensemble to select an optimal number of intermediate structures for a smooth, fluid transition between states. As with most other animations in MovieMaker, the ensemble motion option always morphs the structure from a starting state to a perturbed state and back so that the movie can be placed into a smoothly running infinite loop.

To depict large-scale motions MovieMaker requires two PDB files, each containing the same protein but in a different conformation. As with the ensemble motion option, MovieMaker employs the SuperPose program to intelligently superimpose the two structures and identify any large-scale hinge or domain motions. Displacements between the two states are categorized (<2 Å over >90% of the protein length or >2 Å over >10% of the protein length) by calculating a difference distance matrix between the two superimposed coordinates. After the displacement has been categorized, intermediate structures are created by interpolating between the two end conformers. Both small motions and larger hinge motions can be mapped using the Cartesian interpolation method. Minor distortions creep in for very-large-scale hinge motions, but these distortions can be almost removed by increasing the number of intermediate structures generated between the two conformations.

When the protein folding/unfolding option is selected only a single PDB file (containing a single, folded protein chain) is needed. For this kind of animation, coordinate interpolation must be done in torsion angle space as the intermediate structures simply get too distorted during the unfolding process. In torsion angle interpolation the native structure is regenerated using phi/psi/omega angles derived from the PDB file. This re-rendering in torsion space requires additional structural optimization and can take several minutes, depending on the size of the structure. Once rendered in torsion angle space, the backbone phi/psi angles are iteratively ‘relaxed’ to an unfolded or extended set of phi/psi torsion angles of −160° ± 10°. All intermediate structures are rendered using the same torsion angle structure generator (called PepMake). As always, MovieMaker morphs the structure from the starting state (folded) to the end state (unfolded) and back so that the movie can be placed into a smoothly running infinite loop.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To assess the performance of MovieMaker we chose 30 random protein structures from the PDB consisting of single monomers, complex heteromultimers, NMR ensembles and a variety of proteins with bound ligands. The proteins or protein complexes ranged in size from 56 residues to 1450 residues. We assessed the performance of the program using three criteria, (i) realism, (ii) accuracy and (iii) speed, on as many different types of motions as possible. Assessing realism is somewhat qualitative and highly visual. However, we wanted to make sure that the resulting animations were smooth and did not lead to any obvious ‘breaches’ of the laws of physics such as atoms or chains passing through one another or serious distortions in secondary structure. Of nearly 30 animations studied using the default parameters we found only 4 animations that exhibited a mildly unrealistic chain distortion or a physically unrealistic event. These were confined primarily to animations with very large hinge movements. Apart from these ‘breaches’, vibrational and ensemble motions, rotations, docking, folding and hinge motions all appeared to be performed very well with no obvious problems.

In terms of assessing the accuracy or realism of the small-scale vibrational and structural ensemble motions, we used myoglobin (153 residues, PDB 1MYF) and the pointed domain (110 residues, PDB 1BQV) to visually compare MovieMaker's movies with those generated via the MD simulation program GROMACS (www.gromacs.org). Comparing a short (10 ps) MD simulation for myoglobin calculated by GROMACS with the motion calculated by MovieMaker's small-scale vibrational motion generator, one can see very little difference (the two movies are available on MovieMaker's gallery page). Similarly, a long-term (2.5 ns) MD simulation from GROMACS for the pointed domain appears to be qualitatively similar to the ensemble animation generated by MovieMaker (see the gallery page). Finally hinge motion movements were tested with DNA polymerase beta, cyanovarin N, recoverin and calmodulin proteins. The morphs generated by MovieMaker and the Yale Molecular Motions server appear to be essentially identical for these hinge motion movements.

Table 1 lists the approximate CPU time (2.0 GHz processor with 512 MB RAM) taken for each of the seven types of motion supported by MovieMaker. Obviously these times will vary with the load on the server and the speed of the user's Internet connection. It is clear that the rotation animation is the fastest (10 s), and the motion for the ensemble of structures is the slowest (260 s). Most animations are generated in <30 s. This underlines one of the key strengths of MovieMaker—its speed. Using conventional MD or non-conventional MD simulations (such as adiabiatic dynamics, activated dynamics or Brownian dynamics) would typically take many hours or days of CPU time.

Table 1.

Summary of different simulation or animation scenarios and the CPU time taken to complete the calculation

| Simulation example | PDB IDs | Time taken (s)a |

|---|---|---|

| Simple rotation about Z axis | 4Q21 | 10 |

| Motion between two end-state conformers | 1A29 & 1CLL | 15 |

| Small-scale vibrational motions | 1MYF_A | 16 |

| Oligomerization (assembly/disassembly) | 1C48 | 25 |

| Ligand docking | 1A29 & TFP | 20 |

| NMR ensemble simulation | 1BQV | 260 |

| Protein folding/unfolding | 1A29 | 215 |

aTimes will vary according to server load and PDB file size.

CONCLUSION

It is important to emphasize that MovieMaker is a molecular animation server, not a modelling or MD server. In animation or simulation one attempts to mimic reality using a variety of ad hoc rules that adhere to the general rules of physics. In modelling or MD, one attempts precisely to regenerate reality by solving Newton's equations of motion using well-calibrated molecular force fields. Simulation or animation is frequently employed by video game developers, cartoonists and special effects artists to generate illusions of motion, speed or impact. Rather than attempting to solve Newton's equations for every motion or event, most simulation specialists employ rapidly calculable interpolations and ad hoc rules to generate the necessary visual effect. This allows them to quickly generate the images needed for interactive game play or tight movie release deadlines. By opting for animation over modelling (i.e. mimicry over reality) we have been able to create a very fast and flexible molecular animation tool. Although the images and files generated by MovieMaker should not be used to calculate or predict key molecular parameters, they certainly could be of considerable use for many educational, instructive or illustrative purposes by non-MD specialists. We believe the animations produced by MovieMaker will potentially allow the easy creation of dynamic web pages, informative on line course notes and compelling PowerPoint presentations.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the Protein Engineering Network of Centres of Excellence (PENCE), NSERC and Genome Prairie (a division of Genome Canada). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Genome Prairie.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gehring W.J., Affolter M., Burglin T. Homeodomain proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994;63:487–526. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Versées W., Decanniere K., Holsbeke V.E., Devroede N., Steyaert J. Enzyme–substrate interactions in the purine-specific nucleoside hydrolase from Trypanosoma vivax. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15938–15946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooke R. The mechanism of muscle contraction. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1986;21:53–118. doi: 10.3109/10409238609113609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong L.T., Snow C.D., Rhee Y.M., Pande V.S. Dimerization of the p53 oligomerization domain: identification of a folding nucleus by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:869–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berneche S., Roux B. Molecular dynamics of the KesA K(+) channel in a bilayer membrane. Biophys. J. 2000;78:2900–2917. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76831-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oka T., Yagi N., Fuhisawa T., Kamikubo H., Tokunaga F., Kataoka M. Time-resolved x-ray diffraction reveals multiple conformations in the M-N transition of the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:14278–14282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260504897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrache H.I., Tu K., Nagle J.F. Analysis of simulated NMR order parameters for lipid bilayer structure determination. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2479–2487. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77403-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krebs W.G., Gerstein M. The morph server: a standardized system for analyzing and visualizing macromolecular motions in a database framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1665–1675. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westbrook J.D., Feng Z., Chen L., Yang H., Berman H.M. The Protein Data Bank and structural genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:489–491. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraulis P.J. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiti R., Domselaar G.H.V., Zhang H., Wishart D.S. SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W590–W594. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]