Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to explore the feasibility and dosimetric advantage of using spot-scanning proton arc (SPArc) for lattice radiation therapy in comparison with volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) and intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) lattice techniques.

Methods

Lattice plans were retrospectively generated for 14 large tumors across the abdomen, pelvis, lung, and head-and-neck sites using VMAT, IMPT, and SPArc techniques. Lattice geometries comprised vertices 1.5 cm in diameter that were arrayed in a body-centered cubic lattice with a 6-cm lattice constant. The prescription dose was 20 Gy (relative biological effectiveness [RBE]) in 5 fractions to the periphery of the tumor, with a simultaneous integrated boost of 66.7 Gy (RBE) as a minimum dose to the vertices. Organ-at-risk constraints per American Association of Physicists in Medicine Task Group 101were prioritized. Dose-volume histograms were extracted and used to identify maximum, minimum, and mean doses; equivalent uniform dose; D95%, D50%, D10%, D5%; V19Gy; peak-to-valley dose ratio (PVDR); and gradient index (GI). The treatment delivery time of IMPT and SPArc were simulated based on the published proton delivery sequence model.

Results

Median tumor volume was 577 cc with a median of 4.5 high-dose vertices per plan. Low-dose coverage was maintained in all plans (median V19Gy: SPArc 96%, IMPT 96%, VMAT 92%). SPArc generated significantly greater dose gradients as measured by PVDR (SPArc 4.0, IMPT 3.6, VMAT 3.2; SPArc-IMPT P = .0001, SPArc-VMAT P < .001) and high-dose GI (SPArc 5.9, IMPT 11.7, VMAT 17.1; SPArc-IMPT P = .001, SPArc-VMAT P < .01). Organ-at-risk constraints were met in all plans. Simulated delivery time was significantly improved with SPArc compared with IMPT (510 seconds vs 637 seconds, P < .001).

Conclusions

SPArc therapy was able to achieve high-quality lattice plans for various sites with superior gradient metrics (PVDR and GI) when compared with VMAT and IMPT. Clinical implementation is warranted.

Introduction

Spatially fractionated radiation therapy (SFRT) is an increasingly adopted method of improving the therapeutic index for bulky or radioresistant tumors via intentional spatial dose modulation of high-dose heterogeneity throughout the target.1,2 Phase 1 and retrospective evidence indicate that SFRT can be safely delivered with high clinical tumor response rates.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In addition to ablative dose escalation in “peak” regions, further radiobiologic mechanisms are thought to potentiate tumoricidal effects in low-dose “valleys” including bystander, immunomodulatory, and microvascular effects.11, 12, 13 The addition of immunotherapy has been shown to enhance tumor response in early clinical reports using photon SFRT, possibly via unique augmentation of bystander and abscopal effects that are not optimally expressed with conventional radiation.8,14,15 Moreover, preclinical literature suggests higher linear energy transfer (LET), exhibited in carbon ion therapy and the Bragg peak of proton therapy, elicits a stronger immunogenic response compared with X-rays.16,17 As such, the combination of high LET radiation with SFRT may produce additive or even synergistic tumoricidal benefits via immune-related mechanisms.

Grid therapy is the earliest form of SFRT, involving 2-dimensional collimation of a photon beam into a grid-like distribution of high-dose regions. This arrangement is typically achieved using a block with a customized pattern of apertures or multileaf collimation. Recently, lattice radiation therapy was introduced as a 3-dimensional evolution of grid made possible with intensity modulated radiation therapy.12,18, 19, 20 Lattice treatment plans are characterized by high-dose spheres or “vertices” spaced throughout the tumor. Grams et al21 showed that volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) lattice plans delivered the highest maximum and equivalent uniform doses (EUDs) to tumor while achieving the lowest normal tissue doses (defined as the V30%, V50%, and max dose to the whole body volume minus gross tumor volume [GTV]) when compared with the brass grid and proton grid techniques, although the proton grid technique provided the lowest distal dose beyond the target. Limitations of the proton plans in that study included the single-field beam arrangement and usage of the older grid technique. However, attempts to generate lattice plans with multiple static-field intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) have failed to improve gradient dosimetry compared with photon VMAT.22,23 This has been attributed to the fewer number of fields used with IMPT compared with photon arc therapy.22

Recently, spot-scanning proton arc therapy (SPArc) has become an emerging treatment modality that exploits the inherent benefits of heavy particle therapy and the increased degrees of freedom offered by arc therapy to yield favorable dose distributions.24 Preliminary studies have reported the potential clinical benefits of using SPArc for various clinical indications.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 In 2019, a prototype DynamicARC system was developed in a clinical proton therapy system through a joint academic and industrial partnership, demonstrating its feasibility and efficiency.31, 32, 33 The superior plan quality and high-dose fall-off demonstrated by SPArc therapy may provide meaningful advantages when applied to lattice treatment. Thus, we retrospectively performed the first in silico investigation to explore the potential clinical and dosimetric benefits of SPArc lattice therapy when compared with 4-field IMPT and dual arc VMAT lattice techniques. We have termed our SPArc lattice technique rotationally intensified proton lattice (RIPL), referring to the rotational movement of the gantry and intensified dose escalation in the vertices. Additionally, we tested its feasibility for treatment delivery via simulation using the published DynamicARC model.31

Methods

This single-institution retrospective study is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant and approved by the institutional review board (2017-455) with informed consent waived.

Patients

A retrospective review of patients treated at our institution was performed to identify 14 large tumors, defined as having a maximum tumor diameter of greater than 6 cm. No primary site or histology was excluded. The electronic medical record was used to extract patient and tumor characteristics.

Volume generation

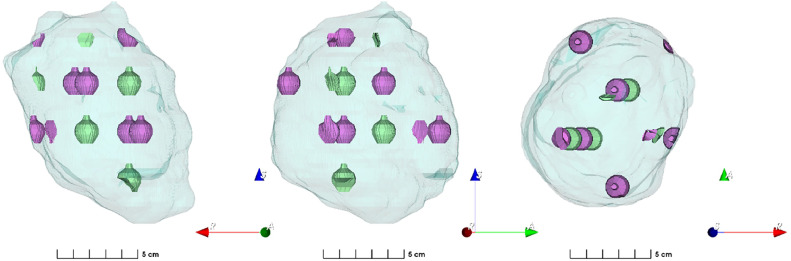

For all tumors, the low-dose target was generated by a 0.5-cm isotropic expansion of the physician-contoured GTV—if available, the internal gross target volume was used. The high-dose target consisted of a 3-dimensional array of spherical vertices algorithmically generated by an in-house script implemented in MIM 7.3.4 (MIM Software Inc). Vertices were 1.5 cm in diameter and placed every 6 cm in the axial plane with successive layers spaced 3 cm apart and offset by 3 cm, based on Kavanaugh et al,34 yielding a distance of 3√2 cm to the nearest neighboring vertex. This forms a body-centered cubic lattice structure with a lattice constant of 6 cm. Vertices were clipped if within 0.5 cm of the target border or 1.5 cm of a critical organs at risk (OARs), resulting in partial (nonspherical) vertices. Prior to clipping, the lattice structure was manually translated with the primary goal of maximizing the number of complete vertices and a secondary goal of maximizing the total high-dose volume. To facilitate plan optimization, avoidance vertices were generated in our low-dose regions, alternating with our high-dose vertices. A Dmax constraint of 34 Gy (relative biological effectivness [RBE]) was imposed on the avoidance vertices to minimize high-dose spill into these regions. Figure 1 depicts an example of the generated lattice (in green) and avoidance structure (in purple) geometries.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional projection of a representative volume from anterior, right lateral, and superior viewpoints. The teal background represents the low-dose volume, the green represents the high-dose volumes/vertices, and the purple represents the avoidance structure.

We calculated 2 metrics to characterize the dose heterogeneity pattern of our lattice geometries: the lattice composite,4 defined as the high-dose volume divided by the low-dose volume, and the high-dose core number density,35 defined as the number of vertices divided by the low-dose volume and multiplied by 100 cm3.

Treatment planning

The low-dose volume was planned to a minimum of 20 Gy (RBE) in 5 fractions, and the vertices were planned to a minimum of 66.7 Gy (RBE) via a simultaneous integrated boost for all cases. The planning goals for both low-dose and high-dose volumes were D95%> 95% of intent dose per Duriseti et al.3 OARs’ constraints were prioritized over target coverage per the guidelines of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine Task Group 101.36

Three planning techniques were employed: VMAT, IMPT, and SPArc/RIPL. All plans were created in Raystation version 6.0 (RaySearch Laboratory Stockholm). VMAT plans were generated with a clockwise and counter-clockwise arc for use on a VARIAN 2100C physics beam model at 6 MV. IMPT plans were generated using an IBA Proteus ONE physics beam model (spot size 3.5 mm 1-sigma at isocenter) with 4 fields. SPArc plans with a single arc (2.5-degree sampling frequency) were generated through in-house scripting.24,31,37 A Monte Carlo dose calculation algorithm with a 3 × 3 × 3 mm3 grid size was used for all plans. For IMPT and SPArc, worst-case robust optimization was employed with ±5 mm setup and ±3.5% range uncertainties applied to the low-dose target. Nonrobust optimization was applied for high-dose volumes across all treatment planning modalities. Plan evaluation for a representative case with and without robust optimization for the high-dose volumes is available in Fig. E1 and Table E1, showing similar trends with either method.

Plan quality evaluation

Dose-volume histograms (DVHs) were collected from Raystation version 6.0. Maximum, minimum, and mean doses; EUD; D95%, D50%, D10%, D5%, D1%, D0.1%, V19Gy, and V63.37Gy; gradient index (GI); and low-dose and high-dose conformity indices (CI) were extracted. GI was calculated as the ratio of the volume of half the prescription isodose to the volume of the prescription isodose. CI was calculated as the ratio of the prescription isodose volume to the tumor volume.

Integral dose was calculated according to previously described methods38 as the product of the total body mean dose (excluding the GTV) with the total body volume and is expressed in Joules (under the approximation that all voxel densities are 1 gm/cm3). Peak-to-valley dose ratios (PVDR) were calculated using 2 methods: (1) the ratio of the prescription dose Dp (ie, 66.7 Gy[RBE]) to the mean value of D95-100%, based on the valley-to-peak dose ratio by Wu et al19 and (2) the ratio of the mean dose of the lattice volume to that of the avoidance structure, as described by Dureseti et al.3

Proton treatment delivery time

Delivery times for IMPT and SPArc were simulated using the previously published delivery sequence model.39,40 In brief, static IMPT delivery time was based on our ProteusONE machine model, which includes burst switch time, spot switch time, spot spill time, and energy layer switch time.40,41 SPArc delivery time calculations involved 2 parts: (1) delivery of the irradiation sequence (similar to that of static delivery) within each control point and (2) mechanical gantry movement between adjacent control points.31,37,39 A 2.5-degree tolerance window was used.32 These calculations were performed using in-house scripts based on previous publications.

Statistical analysis

The dose gradients—as quantified by PVDR, GI, and low-dose and high-dose CI—achieved by each of the 3 techniques were compared via a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A mean DVH and 95% confidence interval were calculated for each technique.

For all statistical tests, α was set at 0.05. Analyses were performed using Python 3.9.7 via Anaconda 3 (Anaconda, Inc). A Python Jupyter notebook for all analyses is available on request.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

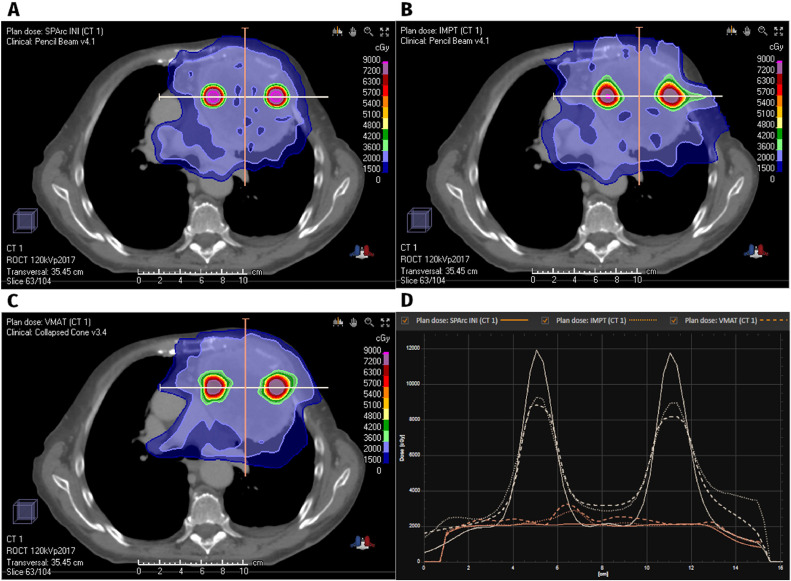

In total, 14 patients were identified with the following site breakdown (Table 1): 5 thoracic, 5 pelvic, 2 abdominal, 2 extremity, and 1 from the head and neck. Median age was 69 years old (range: 28-81), and sex was split evenly male-female. The median tumor GTV was 577 cc (range, 147-1920 cc). A median of 4.5 high-dose vertices (range, 2-15) were treated, of which 3 (range, 1-9) were complete vertices and 1 (range, 0-6) was partial. The median percentage of GTV occupied by lattice vertices was 1.2% (0.7-1.7%), and the median high-dose core number was 0.8. Figure 2 shows a representative tumor with plans from each technique as well as line-dose comparisons in the plane of the vertices (to illustrate peak magnitude) as well as out of plane (to illustrate homogeneity in the low-dose region).

Table 1.

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic | Median (range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 69 (28-81) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (50%) |

| Female | 7 (50%) |

| Primary site | |

| Thoracic | 5 (36%) |

| Pelvic | 5 (36%) |

| Abdominal | 2 (14%) |

| Extremity | 2 (14%) |

| Head and neck | 1 (7%) |

| Volumes | |

| GTV volume (cc) | 577 (147-1920) |

| Lattice composite | 1.2% (0.7-1.7) |

| HCND | 0.8 (0.6-1.4) |

| Number of vertices | |

| Total | 4.5 (2-15) |

| Complete | 3.0 (1-9) |

| Partial | 1.0 (0-6) |

Abbreviations: GTV = gross tumor volume; HCND = high dose core number density.

Figure 2.

Representative axial sections of SPArc (A), IMPT (B), and VMAT (C) plans and line-dose profiles through high-dose vertices (D).

Abbreviations: IMPT = intensity modulated proton therapy; SPArc = spot-scanning proton arc; VMAT = volumetric-modulated arc therapy.

Dosimetry and plan quality

Dosimetric characteristics are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dosimetric summary of SPArc, VMAT, and IMPT plans by maximum, minimum, and mean dose; EUD, D95%, D50%, D10%, D5%, D1%, D0.1%, V19Gy, and V63.37Gy; integral (non-target) dose; peak-valley dose ratio (PVDR), gradient index (GI), and low-dose and high-dose conformity indices (CI low, CI high)

| Characteristic | SPArc | IMPT | VMAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (Gy) | |||

| Minimum | 12 (6-19) | 11 (7-17) | 11 (7-17) |

| Mean | 46 (38-57) | 39 (37-41) | 40 (34-44) |

| Maximum | 110 (92-137) | 92 (88-99) | 93 (78-107) |

| EUD | 20 (14-21) | 20 (18-22) | 20 (15-24) |

| D95% | 19 (18-20) | 19 (19-20) | 19 (17-21) |

| D50% | 21 (20-21) | 22 (21-22) | 24 (21-27) |

| D10% | 28 (23-33) | 33 (29-38) | 37 (31-45) |

| D5% | 40 (34-46) | 44 (37-50) | 47 (38-54) |

| D1% | 71 (61-79) | 68 (61-73) | 69 (61-79) |

| D0.1% | 97 (84-111) | 85 (82-90) | 84 (77-99) |

| V19 Gy | 96 (93-100) | 96 (92-100) | 92 (79-100) |

| V63.37 Gy | 99 (97-100) | 98 (95-100) | 97 (90-100) |

| Integral dose | 57 (20-120) | 61 (25-126) | 116 (16-276) |

| Indices | |||

| PVDR* | 4.0 (3.7-4.6) | 3.6 (3.3-3.8) | 3.2 (2.7-4.1) |

| IndicesPVDR† | 4.2 (3.4-5.4) | 4.2 (3.5-4.8) | 4.4 (3.4-5.4) |

| IndicesGradient index | 5.9 (3.8-8.5) | 10.8 (6.4-19.5) | 16.2 (5-40) |

| IndicesCI low | 0.77 (0.33-0.98) | 0.66 (0.32-0.82) | 0.58 (0.31-0.8) |

| IndicesCI high | 0.57 (0.19-0.77) | 0.59 (0.24-0.8) | 0.57 (0.39-0.89) |

OAR constraints were met in all plans. Coverage of the low-dose target volume was maintained in all plans with a mean V19Gy (V95% of the low-dose prescription) of 96%, 96%, and 92% in the SPArc, IMPT, and VMAT plans, respectively. Mean integral doses for SPArc and IMPT were equivalent (57 J vs 61 J, P = 0.17), but both were superior to VMAT (116 J, SPArc-VMAT P < .001, IMPT-VMAT P < .001). Vertex coverage by V63.37Gy (V95% of the high-dose prescription) was excellent in all plans, but SPArc (99%) was higher than both IMPT (98%, P = .0001) and VMAT (97%, P < .01).

SPArc generated significantly greater dose gradients. For SPArc plans, mean PVDR as defined by Duriseti et al3 were 13% greater than those of IMPT (4.0 vs 3.6, P = .0001) and 26% greater than those of VMAT (4.0 vs 3.2, P < .001). When PVDR was calculated according to Wu et al19, SPArc was equivalent to IMPT (4.2 vs 4.2, P = .63) and VMAT (4.4, P = .06). SPArc had a lower high-dose GI: 45% lower than IMPT (5.9 vs 10.8, P = .0001) and 64% lower than VMAT (16.2, P < .001). SPArc generated greater low-dose CI compared with IMPT (0.77 vs 0.66, P = .013) and VMAT (0.58, P = .002). Conversely, for high-dose CI, SPArc was equivalent to VMAT (0.57 vs 0.57, P = 1), but lower than IMPT (0.59, P = .005).

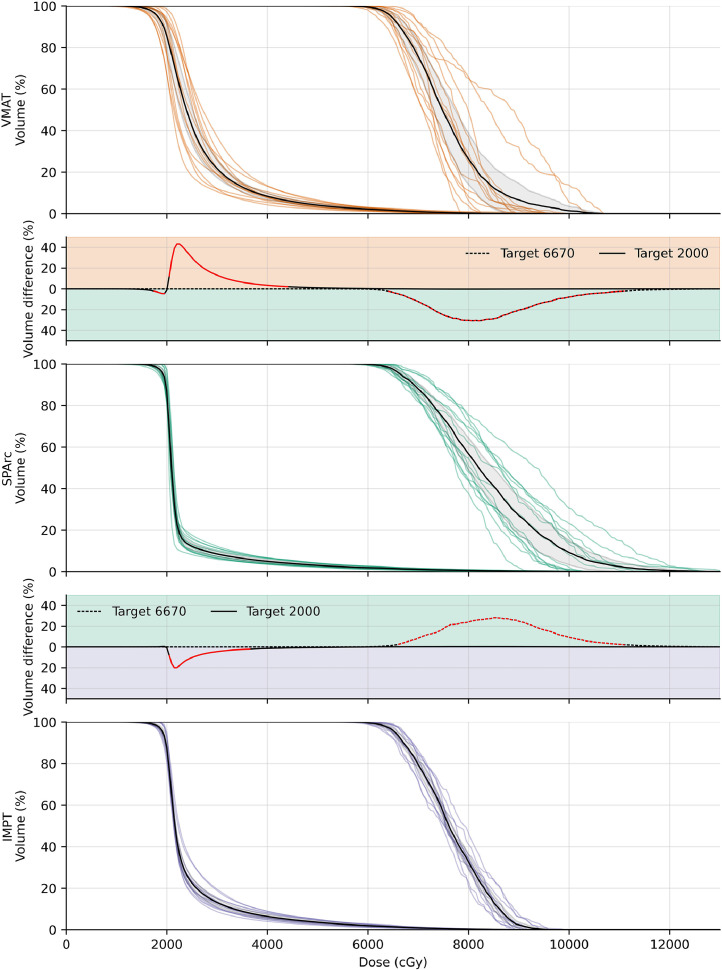

Figure 3 presents the individual DVH curves for each plan and the calculated mean DVH curves for each technique. Dosewise comparisons represented by the intervening difference plots demonstrate the relative advantage of SPArc at every dose level with significant differences indicated in red. Compared with IMPT, SPArc was able to achieve significantly greater volumes at high-dose levels, with a peak of 28% greater coverage over IMPT and 31% greater than VMAT. SPArc was also able to significantly increase homogeneity at low-dose levels, with volume reductions up to 20% for IMPT and 43% for VMAT.

Figure 3.

Individual DVHs for VMAT (orange), SPArc (green), and IMPT (purple) with the corresponding mean DVHs in black (95% confidence interval in gray color wash). The difference plots above and below the SPArc DVH represent the percentage volume difference at each dose level for VMAT-SPArc and SPArc-IMPT, respectively. Red segments indicate significant differences (P < .05).

Abbreviations: DVH = dose-volume histograms; IMPT = intensity modulated proton therapy; SPArc = spot-scanning proton arc; VMAT = volumetric-modulated arc therapy.

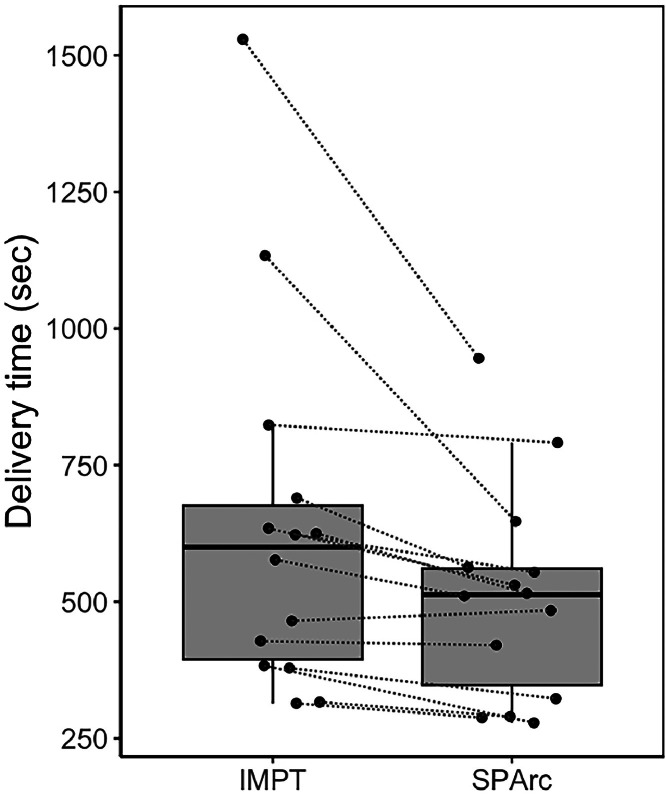

Proton delivery time

Simulated delivery time (Table 3) was significantly improved with SPArc compared with IMPT (510 seconds vs 637 seconds, P < .001). Figure 4 shows a boxplot of the paired delivery times for IMPT and SPArc plans.

Table 3.

Proton treatment delivery times

| Characteristic | Overall | IMPT | SPArc | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic delivery time (s) | 574 (279-1529) | 637 (314-1529) | 510 (279-945) | <.001 |

| Energy layer number | 125 (70-211) | 124 (70-198) | 126 (72-211) | .97 |

Data presented as mean (range). Groups compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test.Abbreviations: IMPT = intensity modulated proton therapy; SPArc = spot-scanning proton arc.

Figure 4.

Boxplot of the simulated treatment delivery times for IMPT and SPArc. Dotted lines indicate paired plans.

Abbreviations: IMPT = intensity modulated proton therapy; SPArc = spot-scanning proton arc.

Discussion

SPArc is a promising new technology that may offer significant dosimetric benefits over photon or conventional IMPT techniques. This is the first study to introduce a feasible SPArc approach to lattice radiation therapy. In our comparison against modern VMAT and static IMPT techniques for large tumors across various anatomic sites, SPArc achieved steeper dose gradients in the high-dose regions, as indicated by higher peak-valley dose ratios (26% higher than VMAT and 13% higher than IMPT) and lower gradient indices. In the low-dose regions, SPArc maintained a more uniform dose distribution. The integral dose of the proton techniques was similar and significantly lower than the photon VMAT plans. OAR constraints were adequately met, regardless of technique. Finally, delivery time was significantly improved with SPArc compared with IMPT.

A previous comparison between photon VMAT lattice, photon brass grid, and proton grid by Grams et al21 found that VMAT lattice delivered the highest maximum and EUDs while achieving the lowest OAR doses. The proton grid plan performed relatively poorly, as the single-field beam arrangement resulted in higher entrance and proximal OAR doses. Subsequent heavy particle lattice studies employed multiple static fields; however, the resulting gradient dosimetry remained similar to that of photon VMAT because of the limited beam angles.22,23 Our 4-field lattice IMPT plans also yielded comparable peak doses and PVDR with photon VMAT. However, the increased degrees of freedom with rotational SPArc produced significant incremental benefits to the maximum dose and gradient steepness.

The lattice geometry, prescription dosing, and photon VMAT treatment planning in this study are based on the method developed by Duriseti et al3,4 and used on LITE SABR M1.34 Briefly, the high-dose vertices are 1.5 cm in diameter and spaced 6 cm apart with successive layers offset by 3 cm, generating a body-centered cubic lattice geometry. We implemented this technique algorithmically, using an in-house workflow in MIM that automatically generated our vertex and avoidance structure arrays. This increased reproducibility and consistency while dramatically decreasing contouring time. Similar to the investigators of LITE SABR M1, we found that the SFRT-specific gradient metric Dp/Dmean(95%-100%) initially proposed by Wu et al19 did not accurately capture differences in dose distributions between our planning techniques. This definition penalized better low-dose performance and did not reward higher peak doses within the vertices. Duriseti et al3 used an alternate formula where PVDR is the ratio of the mean vertex dose to the mean avoidance structure dose. We found this method rewarded greater peak vertex doses and better represented homogeneity in the valley regions. Of note, the definitions and usage of SFRT dosimetric parameters are not standardized, and practices vary widely among physicians.42,43

As previously detailed, our lattice arrangement follows the systematic approach per Duriseti et al3 because of its ease of reproducibility. However, a variety of arbitrary lattice geometries are used in the literature,6,9,44 with no current consensus regarding the optimal positioning of vertices.43,45 Exploration of different lattice geometries may be constrained by institution-specific machine and treatment planning system capabilities. However, the dramatic dose gradients achieved by SPArc allow for more flexible vertex placement. For example, the body-centered cubic lattice in this study and Duriseti et al3 has a sphere packing factor of 0.68, whereas face-centered cubic/hexagonal close-packed arrangements can increase this to 0.74, maximizing high-dose volume. Conversely, a simple cubic packing arrangement, with a packing factor of 0.52, nearly balances peak and valley volumes.

Combination therapy with immunotherapy has been shown to enhance tumor response to photon SFRT,14,15,46 highlighting the contribution of immunomodulatory effects to traditional radiobiologic mechanisms of cell killing with heterogeneous dose distributions.47 Preclinical studies with heavy particle therapy have also demonstrated infiltration of antitumor immune cells within the irradiated tumor as well as abscopal tumors,17,48,49 suggesting potential synergism between SPArc and immune checkpoint inhibition. Moreover, high LET counters hypoxia by diminishing the oxygen enhancement ratio.50 Thus, protocols employing hypoxic-directed ablation8,9 may benefit from SPArc.

Limitations of our study include its retrospective and in silico nature. As yet, no institution has been able to implement proton arc therapy. Second, the low number of plans for each anatomic region limits our ability to offer site-specific recommendations, although the minimal OAR doses suggest that SPArc lattice can be safely delivered in the majority of cases. Finally, the restricted availability of proton centers, namely those equipped for proton arc therapy, limits the generalizability of this technique. However, we anticipate improved accessibility because of the rising number of proton facilities and patients undergoing proton therapy.51

Conclusions

A novel SPArc-based lattice technique, RIPL, was introduced for a variety of large tumors via an in silico study. RIPL produced high-quality treatment plans with superior gradient metrics compared with modern VMAT and conventional IMPT methods.

Disclosures

Xuanfeng Ding reports financial support was provided by IBA SA. Xuanfeng Ding reports a relationship with IBA SA that includes: speaking and lecture fees. Xuanfeng Ding and Xiaoqiang Li hold the patent on particle arc therapy and it has been licensed to IBA. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Sources of support: The study is, in part, supported by IBA research funding.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.adro.2024.101632.

Contributor Information

Xuanfeng Ding, Email: xuanfeng.ding@corewellhealth.org.

Thomas J. Quinn, Email: thomas.quinn@corewellhealth.org.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Griffin RJ, Ahmed MM, Amendola B, et al. Understanding high-dose, ultra-high dose rate, and spatially fractionated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:766–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayr NA, Snider JW, Regine WF, et al. An international consensus on the design of prospective clinical-translational trials in spatially fractionated radiation therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2021.100866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duriseti S, Kavanaugh JA, Szymanski J, et al. Lite sabr m1: A phase I trial of lattice stereotactic body radiotherapy for large tumors. Radiother Oncol. 2022;167:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2021.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duriseti S, Kavanaugh J, Goddu S, et al. Spatially fractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (lattice) for large tumors. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amendola BE, Perez NC, Wu X, Blanco Suarez JM, Lu JJ, Amendola M. Improved outcome of treating locally advanced lung cancer with the use of lattice radiotherapy (lrt): a case report. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2018;9:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amendola BE, Perez NC, Mayr NA, Wu X, Amendola M. Spatially fractionated radiation therapy using lattice radiation in far-advanced bulky cervical cancer: a clinical and molecular imaging and outcome study. Radiat Res. 2020;194:724–736. doi: 10.1667/RADE-20-00038.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amendola BE, Perez NC, Wu X, Amendola MA, Qureshi IZ. Safety and efficacy of lattice radiotherapy in voluminous non-small cell lung cancer. Cureus. 2019:11. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tubin S, Popper HH, Brcic L. Novel stereotactic body radiation therapy (sbrt)-based partial tumor irradiation targeting hypoxic segment of bulky tumors (sbrt-pathy): Improvement of the radiotherapy outcome by exploiting the bystander and abscopal effects. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferini G, Parisi S, Lillo S, et al. Impressive results after "Metabolism-guided" Lattice irradiation in patients submitted to palliative radiation therapy: preliminary results of lattice_01 multicenter study. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:3909. doi: 10.3390/cancers14163909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed SK, Petersen IA, Grams MP, Finley RR, Haddock MG, Owen D. Spatially fractionated radiation therapy in sarcomas: A large single-institution experience. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024;9 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2023.101401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanagavelu S, Gupta S, Wu X, et al. In vivo effects of lattice radiation therapy on local and distant lung cancer: potential role of immunomodulation. Radiat Res. 2014;182:149–162. doi: 10.1667/RR3819.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billena C, Khan AJ. A current review of spatial fractionation: Back to the future? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moghaddasi L, Reid P, Bezak E, Marcu LG. Radiobiological and treatment-related aspects of spatially fractionated radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3366. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang L, Li X, Zhang J, et al. Combined high-dose lattice radiation therapy and immune checkpoint blockade for advanced bulky tumors: the concept and a case report. Front Oncol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.548132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohiuddin M, Park H, Hallmeyer S, Richards J. High-dose radiation as a dramatic, immunological primer in locally advanced melanoma. Cureus. 2015;7:e417. doi: 10.7759/cureus.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamada T, Tsujii H, Blakely EA, et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy in japan: an assessment of 20 years of clinical experience. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e93–e100. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirjolet C, Nicol A, Limagne E, et al. Impact of proton therapy on antitumor immune response. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13444. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92942-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X, Ahmed MM, Wright J, Gupta S, Pollack A. On modern technical approaches of three-dimensional high-dose lattice radiotherapy (LRT) Cureus. 2010;2 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X, Perez NC, Zheng Y, et al. The technical and clinical implementation of lattice radiation therapy (lrt) Radiat Res. 2020;194:737–746. doi: 10.1667/RADE-20-00066.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iori F, Cappelli A, D'Angelo E, et al. Lattice radiation therapy in clinical practice: a systematic review. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2023;39 doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2022.100569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grams MP, Tseung HSWC, Ito S, et al. A dosimetric comparison of lattice, brass, and proton grid therapy treatment plans. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12:e442–e452. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang D, Wang W, Hu J, et al. Feasibility of lattice radiotherapy using proton and carbon-ion pencil beam for sinonasal malignancy. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:467. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Lin Y, Wang F, Badkul R, Chen RC, Gao H. Lattice position optimization for lattice therapy. Med Phys. 2023;50:7359–7367. doi: 10.1002/mp.16572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding X, Li X, Zhang JM, Kabolizadeh P, Stevens C, Yan D. Spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) therapy: The first robust and delivery-efficient spot-scanning proton arc therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Kabolizadeh P, Yan D, et al. Improve dosimetric outcome in stage iii non-small-cell lung cancer treatment using spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:35. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-0981-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang S, Liu G, Zhao L, et al. Feasibility study: spot-scanning proton arc therapy (sparc) for left-sided whole breast radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15:232. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding X, Zhou J, Li X, et al. Improving dosimetric outcome for hippocampus and cochlea sparing whole brain radiotherapy using spot-scanning proton arc therapy. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:483–490. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1555374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu G, Li X, Qin A, et al. Improve the dosimetric outcome in bilateral head and neck cancer (hnc) treatment using spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) therapy: a feasibility study. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-1476-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu G, Li X, Qin A, et al. Is proton beam therapy ready for single fraction spine sbrs?—a feasibility study to use spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) therapy to improve the robustness and dosimetric plan quality. Acta Oncol. 2021;60:653–657. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2021.1892183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu G, Zhao L, Qin A, et al. Lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (sbrt) using spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) therapy: a feasibility study. Front Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.664455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Liu G, Janssens G, et al. The first prototype of spot-scanning proton arc treatment delivery. Radiother Oncol. 2019;137:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu G, Zhao L, Liu P, et al. The first investigation of spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) delivery time and accuracy with different delivery tolerance window settings. Phys Med Biol. 2023:68. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/acfec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wuyckens S, Saint-Guillain M, Janssens G, et al. Treatment planning in arc proton therapy: Comparison of several optimization problem statements and their corresponding solvers. Comput Biol Med. 2022;148 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavanaugh JA, Spraker MB, Duriseti S, et al. Lite sabr m1: Planning design and dosimetric endpoints for a phase I trial of lattice sbrt. Radiother Oncol. 2022;167:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Ma L, Lim A, et al. Dosimetric validation for prospective clinical trial of grid collimator-based spatially fractionated radiation therapy: dose metrics consistency and heterogeneous pattern reproducibility. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2024;118:565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benedict S, Wang L, Kavanagh B. Tu-d-202-01: Overview of the aapm tg 101. Med Phys. 2010;37 3398-3398. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu G, Li X, Zhao L, et al. A novel energy sequence optimization algorithm for efficient spot-scanning proton arc (sparc) treatment delivery. Acta Oncol. 2020;59:1178–1185. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1765415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grzywacz VP, Arden JD, Mankuzhy NP, et al. Normal tissue integral dose as a result of prostate radiation therapy: A quantitative comparison between high-dose-rate brachytherapy and modern external beam radiation therapy techniques. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023;8 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2022.101160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu G, Zhao L, Liu P, et al. Development of a standalone delivery sequence model for proton arc therapy. Med Phys. 2024;51:3067–3075. doi: 10.1002/mp.16879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao L, Liu G, Zheng W, et al. Building a precise machine-specific time structure of the spot and energy delivery model for a cyclotron-based proton therapy system. Phys Med Biol. 2022:67. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ac431c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao L, Liu G, Chen S, et al. Developing an accurate model of spot-scanning treatment delivery time and sequence for a compact superconducting synchrocyclotron proton therapy system. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17:87. doi: 10.1186/s13014-022-02055-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayr NA, Mohiuddin M, Snider JW, et al. Practice patterns of spatially fractionated radiation therapy: A clinical practice survey. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2023.101308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Mayr NA, Griffin RJ, et al. Overview and recommendations for prospective multi-institutional spatially fractionated radiation therapy clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2024;119:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grams MP, Owen D, Park SS, et al. Vmat grid therapy: a widely applicable planning approach. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021;11:e339–e347. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amendola BE, Mahadevan A, Blanco Suarez JM, et al. An international consensus on the design of prospective clinical-translational trials in spatially fractionated radiation therapy for advanced gynecologic cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:4267. doi: 10.3390/cancers14174267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Q, Yan W, Zhu A, Tubin S, Mourad WF, Yang J. Combining spatially fractionated radiation therapy (sfrt) and immunotherapy opens new rays of hope for enhancing therapeutic ratio. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2024;44 doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2023.100691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demaria S, Guha C, Schoenfeld J, et al. Radiation dose and fraction in immunotherapy: one-size regimen does not fit all settings, so how does one choose? J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helm A, Tinganelli W, Simoniello P, et al. Reduction of lung metastases in a mouse osteosarcoma model treated with carbon ions and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee HJ, Zeng J, Rengan R. Proton beam therapy and immunotherapy: an emerging partnership for immune activation in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:180–188. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.03.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Helm A, Fournier C. High-let charged particles: Radiobiology and application for new approaches in radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2023;199:1225–1241. doi: 10.1007/s00066-023-02158-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartsell WF, Simone CB, II, Godes D, et al. Temporal evolution and diagnostic diversification of patients receiving proton therapy in the united states: A ten-year trend analysis (2012 to 2021) from the national association for proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;119:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.