Abstract

Population expansions and contractions out of and into Africa since the early Pleistocene have influenced the course of human evolution. While local- and regional-scale investigations have provided insights into the drivers of Eurasian hominin dispersals, a continental-scale and integrated study of hominin-environmental interactions across Palearctic Eurasia has been lacking. Here, we report high-resolution (up to ∼5-10 kyr sample interval) carbon isotope time series of loess deposits in Central Asia and northwest China, a region dominated by westerly winds, providing unique paleoecological and paleoclimatic records for over ~3.6 Ma. These data, combined with further syntheses of Pleistocene paleontological and archaeological records and spatio-temporal distributions of Eurasian eolian deposits and river terraces, demonstrate a pronounced transformation of landscapes around the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition. Increased climate amplitude and aridity fluctuations over this period led to the widespread formation of more open habitats, river terraces, and desert-loess landscapes, pushing hominins to range more widely and find solutions to increasingly challenging environments. Mid-Pleistocene climatic and ecological transitions, and the formation of modern desert and loess landscapes and river networks, emerge as critical events during the dispersal of early hominins in Palearctic Eurasia.

Subject terms: Palaeontology, Palaeoclimate

Mid-Pleistocene climatic and ecological transitions and the formation of modern desert and loess landscapes and river networks emerge as critical events during the dispersal of early hominins in Palearctic Eurasia.

Introduction

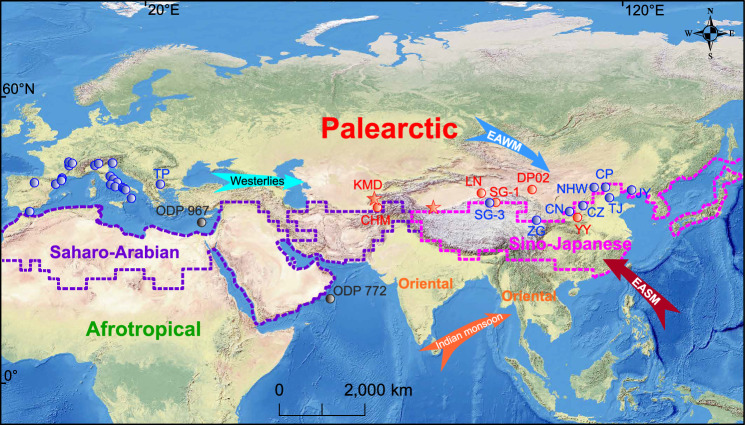

The Palearctic Realm of Eurasia extends from the Atlantic to the Pacific and includes Europe and Asia north of the Oriental and Sino-Japanese Realms1 (Fig. 1). Its weather system is dominated by westerly winds that bring rain from the Atlantic, and further east, the Mediterranean, Black and Caspian Seas. In China north of the Qinling Mountains, the weather is dominated by the East Asian monsoon. Hominins began to colonize Palearctic Asia before 2 Ma, with the earliest evidence of hominins outside Africa represented by 2.1 Ma-old artifacts from Shangchen in the Chinese Loess Plateau (CLP)2. Fossil evidence from Dmanisi, Georgia, dated at 1.8 Ma, and Gongwangling, China, dated at 1.63 Ma, indicates that the earliest colonizing populations were an early form of H. erectus3,4. Europe appears to have been colonized later: the earliest secure dates from Atapuerca and the Orce Basin (Spain) are ca. 1.4 – 1.2 Ma5,6; Pirro Nord from Italy may be of comparable age7. By the end of the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition (MPT, 1.25-0.7 Ma), hominins had established themselves across the whole of Palearctic Eurasia, up to 40 °N in Asia8,9 and 55 °N in northwest Europe10.

Fig. 1. Locations of eolian loess and fluvial-lacustrine sequences referenced in the text and the Palearctic Realm of Eurasia (after ref. 1).

EASM and EAWM represent the East Asian summer and winter monsoons, respectively. Red stars indicate the locations of late Pliocene loess sequences from the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan. KMD and CHM: Karamaidan (this study) and Chashmanigar loess sections from southern Tajikistan. Red solid circles represent the spatial distributions of carbon isotopic records referenced in the text. Blue solid circles represent the spatial distributions of pollen records in Eurasia. LN: Lop Nor Lake sediments in the Tarim Basin. SG-1 and SG-3: Lake sediment cores from the western Qaidam Basin. JY: Jinyuan Cave deposits from the Liaodong Peninsula. CP and NHW: Fluvio-lacustrine sediments from the Beijing Plain and the Nihewan Basin in North China. TJ: Tianjin-G3 core in the North China Plain. DP02: The Badain Jaran Desert drill core. CZ: Fluvio-lacustrine sediments from the Chinese Loess Plateau (CLP). YY and CN: Yanyu and Chaona loess sections in the CLP. ZG: Lacustrine sediments from the Zoige Basin in SE Tibet. TP: The Tenaghi Philippon, Greece. Information about the locations of pollen records from Europe is presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.

The climatic and environmental histories of Europe and Asia are usually discussed separately. However, they are parts of the same biological realm, meaning their vertebrate assemblages share a common phylogenetic composition1. As phylogenetic compositions are driven by regional climatic and ecologic factors11, the history of both regions needs to be considered together when examining the drivers of hominin dispersals out of Africa. By integrating new and existing data on the long-term history of the climate, vegetation, and fauna of Palearctic Eurasia, we show how the landscape was dramatically transformed by climatic factors around the MPT, with profound consequences on hominin behavior and evolution.

In Africa, stable carbon isotopic compositions of soil organic matter and paleosol carbonate have been widely used to reconstruct regional vegetation cover and paleoclimate as well as hominin-environmental interactions12,13. However, continuous and high-resolution carbon isotope records since the late Pliocene have rarely been reported from the Westerlies-influenced regions in Europe and Central Asia. To address this deficit, we report carbon isotope records of soil organic matter (δ13Corg) of loess deposits from the western margin of the Pamir and the southern Tarim Basin, northwest China, respectively (Fig. 1). Both areas are dominated by westerly winds (Supplementary Fig. 1). These records were derived from a 180-m-thick loess sequence in southern Tajikistan (Supplementary Fig. 2), and a 671 m-deep loess core obtained from the highest fan surface of the southern margin of the Tarim Basin and downwind of the Taklimakan Desert. Paleomagnetic dating combined with further analyses of astronomically tuned timescale suggests that loess succession at the southern margin of the Tarim Basin and southern Tajikistan accumulated from ∼ 3.6 Ma and 2.7 Ma to the present, respectively14,15. Central Asia and NW China are regarded as crucial migration gateways of hominins to disperse west to east (or vice versa) across Eurasia (Fig. 1) and represent the eastern-most boundary of the Westerlies-influenced areas (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, δ13Corg records of these loess deposits can provide critical information on precipitation and precipitation-controlled vegetation density as well as their impacts on early hominin dispersals in the Westerlies-influenced regions since the late Pliocence. Moreover, in providing these long paleoclimate records, we can highlight just how unique the changes centered around the MPT are for the Plio-Pleistocene. Our carbon isotope results, combined with syntheses of Pleistocene paleontological and carbon isotope records from SW China and Southeast Asia16,17, provide holistic insights into the regional vegetation cover and paleoclimatic conditions for the northern and southern migration routes of early hominins through Asia.

Results

Eolian dust deposition and pedogenesis in Central Asia and NW China are continuously competing processes, with dust accumulation rates usually showing much higher values in loess units than those in paleosol layers. In southern Tajikistan, paleosols are well developed due to their location on the windward slope of the Westerlies-influenced areas, and lithological characteristics of the loess deposits resemble those of contemporaneous loess-paleosol units in the CLP15. In contrast, paleosols in the Tarim Basin are very weakly developed due to low precipitation, and the carbonate nodular (Bk) horizons are difficult to define at most levels. A total of 286 and 244 loess samples, spanning 2.7 and 3.6 Ma to the present with a temporal resolution of ∼ 5–10 kyr and ∼ 10–20 kyr, respectively, were collected from Tajikistan and the Tarim Basins (Supplementary Fig. 2). Samples for the carbon isotope analysis of organic matter were collected from all loess and paleosol units.

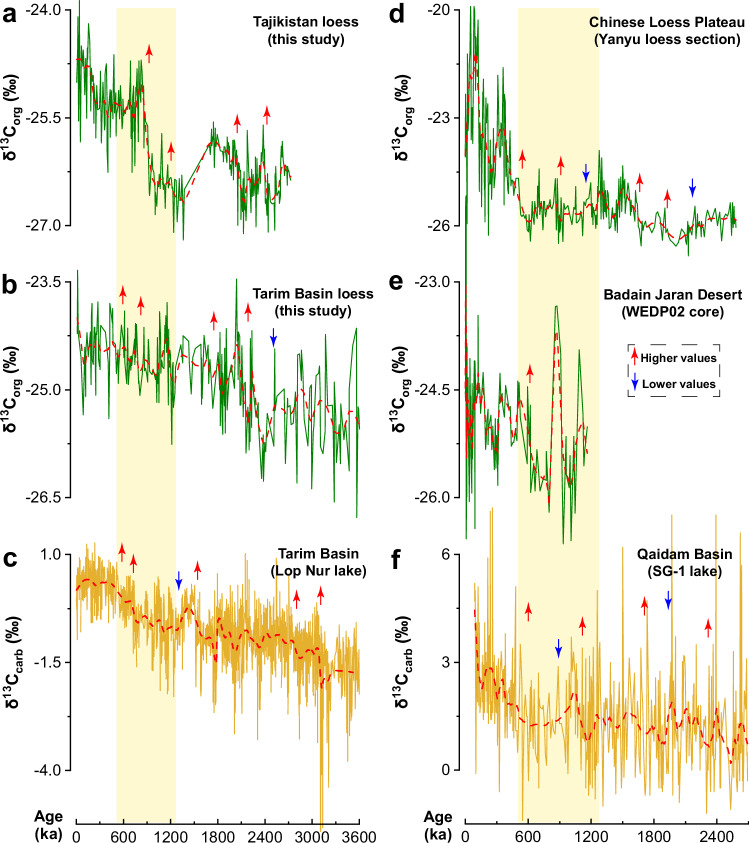

The δ13Corg values of the Tajikistan loess and the Tarim Basin loess range from − 27.2‰ to − 23.87‰ and from − 26.78‰ to − 23.34‰, respectively. Both records are characterized by long-term increases since the late Pliocene, punctuated by pronounced shifts toward more positive δ13Corg values at the end of the MPT, i.e., ~ 0.9-0.6 Ma (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Statistical change-point analyses of Mann–Whitney and Ansari–Bradley tests of δ13Corg records can provide crucial constraints on the rhythms, events and trends in paleoclimatic changes across Eurasia (see “Methods” for further discussion). Our results demonstrate that breakpoints in the slopes of both δ13Corg records are evident around the MPT (Supplementary Fig. 3), particularly between 0.9 and 0.6 Ma, indicating a remarkable increase in the carbon isotopic ratios with a larger fluctuation in amplitude corresponding to the shift in Earth’s climate from 41-kyr cyclicity to 100-kyr cyclicity. Specifically, the mean values of δ13Corg in Tajikistan increased from − 26.29‰ prior to 0.9 Ma to − 25.17‰ after 0.9 Ma, whereas in the Tarim Basin, they increased to − 24.42‰ after 0.9-0.6 Ma.

Fig. 2. Carbon isotope records of soil organic matter and total carbonate of eolian and fluvial-lacustrine sediments in Central Asia32 and East Asia38–40 (see Fig. 1 for site locations).

a–c Carbon isotope records from south Tajikistan and the Tarim Basin. d–f Carbon isotope records from the Chinese Loess Plateau and the adjacent regions. The dashed lines in each time series plot are locally weighted smoothing means (LOESS) using a 0.1 or 0.2 proportion window. The shaded areas indicate the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition (MPT). The red arrows show the breakpoints of increasing δ13C values determined by the Mann–Whitney test. Note that all sections show a prominent increase in δ13Corg and δ13Ccarb values since the MPT, particularly after 0.9-0.6 Ma when global glacial ice volume reached maximum value.

At present, vegetation in Central Asia and NW China is dominated by C3 plants18,19. The δ13Corg value range suggests that the soil organic matter of loess deposits from the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan was sourced mostly from C3 plants since the late Pliocene20. Recently, a series of studies on the relationship between the δ13C data of C3 plants and organic matter from surface soils and climate in NW China and Central Asia have shown that a strong negative correlation exists between δ13C values and local mean annual precipitation (MAP)21–23. The δ13Corg records of loess deposits in these areas thus inform paleoprecipitation reconstructions21,23. These observations are consistent with the relationship between climate and δ13Corg of surface soils under dominant C3 vegetation at a global scale that indicates the δ13Corg values are less sensitive to temperature variability, but instead closely related to changes in precipitation18. Planktic foraminiferal δ11B ratios demonstrate that while a significant decrease in atmospheric CO2 occurred mainly after 2.8 and 2 Ma24,25, pCO2 levels were relatively stable or increased slightly since the MPT26,27. Meanwhile, a colder climate is associated with the intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations since the MPT28 favors the growth of C3 over C4 plants, thereby leading to a significant reduction in δ13Corg. These observations suggest that changes in temperature and pCO2 levels cannot account for the Mid-Pleistocene increase of δ13Corg records in Central Asia and NW China. Thus, temporal variations in δ13Corg values of loess deposits from the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan mainly reflect the paleoprecipitation variability in the Westerlies-influenced regions (see “Methods” for further discussion).

Using previously established linear correlations between the MAP and the δ13Corg of surface soils in Central Asia and the NW China29,30, paleoprecipitation changes in south Tajikistan and the Tarim Basin can be estimated. These correlations suggest the precipitation in Tajikistan decreased by approximately 100–200 mm after the Mid-Pleistocene. In the Tarim Basin, precipitation decreased from ~ 200 mm during the late Pliocene to ~ 100 mm after the MPT. Generally, the absence of paleosols in Chinese eolian deposits indicates that the MAP is less than 200–300 mm31. These findings are consistent with lithological observations that paleosols in the Tarim Basin are very weakly developed since the late Pliocene (see “Methods” for further details).

The relationships between δ13Corg and precipitation vary geographically, and our inferred palaeoprecipitation values require validation from modern datasets from Tajikistan and Tarim Basin, which are currently lacking. Nevertheless, our results indicate that enhanced aridification would have led to a significant increase in δ13Corg values of loess sediments from Central Asia and NW China. The δ13Corg values of modern soil in southern Tajikistan, where MAP varies between 300 and 600 mm, are much lower than those in the Tarim Basin (20–100 mm), providing further evidence that the loess carbon isotope ratios in Central Asia and NW China are controlled mainly by local precipitation.

Discussion

Mid-Pleistocene aridity and landscape shifts

Both δ13Corg records in the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan show a long-term upward increasing trend punctuated by pronounced shifts toward more positive values at ~ 0.9-0.6 Ma (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3). These observations suggest a long-term climatic deterioration in Central Asia and NW China in response to global cooling since the late Pliocene. Moreover, prominent desiccation at ~ 0.9-0.6 Ma occurred in the Westerlies-influenced areas associated with the significant increase in global ice volume (Supplementary Fig. 2). Loess deposits in the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan both show a rapid increase in accumulation rate and median grain size since the MPT, with a pronounced shift of dominant periodicity from 41,000 yr to 100,000 yr after 0.9-0.6 Ma14,15, confirming the occurrences of increased aridity. Carbon isotope data of total carbonate (δ13Ccarb) of fluvial-lacustrine deposits from the Lop Nor Lake in the eastern Tarim Basin also show similar patterns of variation to the δ13Corg records in the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan32 (Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Fig. 3), providing further support for enhanced aridification in Central Asia and NW China since the MPT (see “Methods” for further discussion about the paleoclimatical interpretations of δ13Ccarb).

Global satellite observations suggest a positive linear correlation between MAP and vegetation cover under arid environments, spotlighting water as the primary limit to vegetation growth in the arid regions on Earth33. Recent studies further indicate that rising levels of precipitation could increase soil moisture and biomass in arid Central Asia and NW China32,34. As such, Mid-Pleistocene aridity would trigger marked ecological shifts toward more open habitats in these regions. This conclusion is further supported by the significantly increased percentage of shrub and herb pollen and concentration of microcharcoal in the Tarim Basin after ~ 0.6 Ma35.

Tajikistan sits on a crucial migration pathway of hominins dispersing through Eurasia9,36. The Palaeolithic sites in the loess-palaeosol sections of southern Tajikistan provide the most spectacular picture of the loessic Palaeolithic across Eurasia37. To date, little information is known about the regional vegetation cover and paleoclimatic changes prior to the Mid-Pleistocene in this area. Our results demonstrate that although vegetation oscillations existed during glacial-interglacial cycles in Tajikistan, the vegetation community was relatively stable during the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene. A prominent shift in vegetation cover and vegetation communities is recorded only around the MPT. Similar patterns of vegetation changes were also observed in the Tarim Basin (Fig. 2b, c). Collectively, these observations demonstrate that a marked ecological shift toward more open habitats is coeval with the MPT along the northern migration route of early hominins through Eurasia.

A significant increase in δ13Corg and δ13Ccarb records between 1.2 and 0.6 Ma was further observed in eolian and fluvial-lacustrine sediments from the monsoon-controlled areas in the CLP and the adjacent regions32,38–40 (Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Fig. 3), supporting enhanced aridification in most areas of East Asia since the MPT (see “Methods” for further discussion about the paleoclimatical interpretations of δ13Ccarb). In addition, δ13C of fossil tooth enamel suggests that the spread of grazers and extinction of browsers occurred synchronously in Southeast Asia since the Mid-Pleistocene due to the ecosystem conversion from forests to savannahs17, providing support for reduced precipitation in the Indian summer monsoon-controlled areas. This observation suggests that a marked ecological shift toward more open habitats due to decreasing precipitation also occurred along the southern migration route of early hominins in Asia since the Mid-Pleistocene.

Reduced precipitation would have impacted climatic desiccation and vegetation changes in Palearctic Eurasia, particularly in the arid and semi-arid regions of NW China and Central Asia owing to intensive evaporation41.

There were two main consequences of the desiccation in Palearctic Eurasia. The first was the replacement of woodland and closed forest by steppe and woodland-steppe environments across most of Palearctic Eurasia during the glacial periods of the Mid-Pleistocene. In northern China and southeast Tibet, the principal vegetation biomes during the early Pleistocene glacial periods were characterized by coniferous or broadleaf forests, and then showed a glacial change toward open forest steppe at the onset of the MPT (Supplementary Fig. 4). Pollen records from Spain, France, Greece, and Italy suggest that an ecological shift toward more open habitats, together with a serial extinction of moisture-requiring taxa (the so-called Tertiary relicts), is evident during glacial periods since ~ 0.9-0.6 Ma42,43 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Although the principal vegetation biomes in Europe during interglacial stages were still characterized by forests after the MPT, vegetation nevertheless became less diverse. These changes were accompanied by the emergence of a steppe-tundra fauna that originated in Central and Northeast Asia and expanded westwards across Eurasia44 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Overall, a drying climate since the Mid-Pleistocene led to the temporal extension of open habitats, thereby providing challenging but potentially favorable conditions for hominin dispersals in Palearctic Eurasia.

The second consequence was the formation and expansion of the modern desert-loess landscapes of Central Asia and northwest China14,15,45 (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1). This expansion was driven by climatic factors. As global ice volume increased during the MPT, significant decreases in the moisture supply of the westerly winds and the Asian summer monsoon due to a weakening of oceanic water evaporation, would enhance aridity in Eurasia. The reduced moisture supplies of the Westerlies, accompanied by intensive evaporation and sparse vegetation cover, likely explain the occurrence of strong dust storm events and the continuous accumulation of loess deposits in Central Asia and NW China.

A permanent presence of the second largest active dune field in the world, the Taklimakan Desert, has been identified since the MPT14,32. In NW China, the Mu Us Desert, which is located at the northern margin of the CLP, migrated southward dramatically between 1.2 and 0.7 Ma46. Desert landscapes in the Badain Jaran Desert and Tengger Desert, as well as the Horqin and Otindag sandy lands, were primarily formed since the Mid-Pleistocene, a crucial precondition for the establishment of modern desert landscape in North China45. As deserts expanded significantly since the MPT, the geographical distributions of eolian loess deposits in Eurasia extended westwards to Ukraine, Central Europe, and the Danube River drainage area in Europe, east to the Liaohe drainage area in northeastern China, and south to the Yangtze River drainage area in south China (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1). The occurrence of continental aridification and expansion of the Eurasian loess belt in the Northern Hemisphere further led to a pronounced increase of eolian sediment supply from the terrestrial dust sources to the downwind oceans, e.g., the Mediterranean Sea, the Arabian Sea, and the North Pacific Ocean (Supplementary Figs. 8a–e and 9).

Hominin dispersals and technological innovations in Palearctic Eurasia

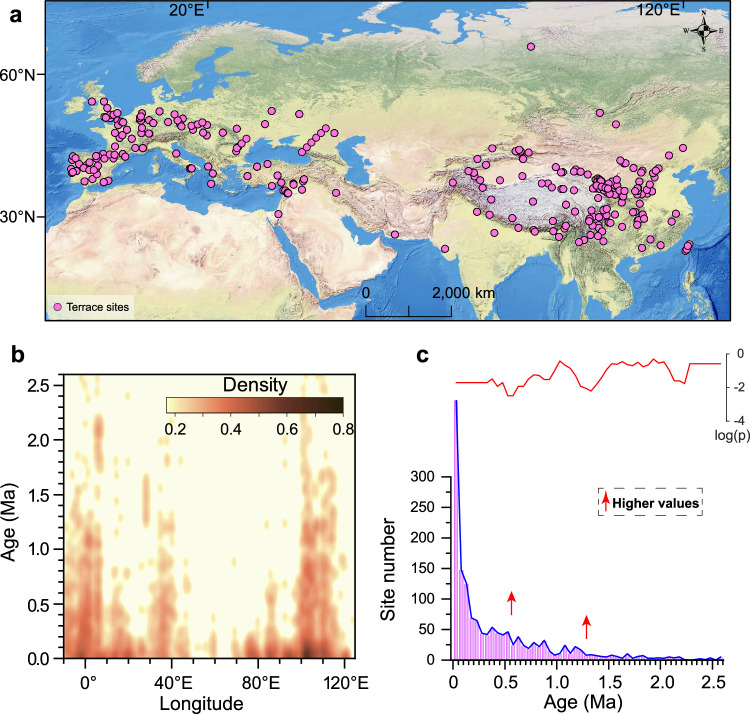

The desertification of much of Central Asia and NW China had severe consequences on the ability of hominins to disperse west to east (or vice versa) across Eurasia except in rare “windows of opportunity” such as humid stages during interglacials MIS 15-11 (621–374 ka), when hominins with a Large Cutting Tools (Acheulean) technology47 may have been able to enter China from the west. Archaeological sites in Central Asia reappear soon after the MPT, suggesting that aridity does not allow for continuous occupations in this climate-sensitive area9. Other environmental factors were needed to enable the widespread establishment of hominin populations in Eurasia during this time. Kernel density estimation and Mann–Whitney and Ansari–Bradley tests of river terraces and archaeological records can provide crucial constraints on the evolution of river networks and the events and trends in hominin distribution and dispersals across the region (see “Methods”). Coinciding with the developments of eolian landscapes and open environments, and as global ice volume and climatic instability increased during the MPT, intense river incision along the river margins in the upstream regions occurred in response to lowering base level (Supplementary Figs. 8g, h and 10). This led to the formation of a series of fluvial terraces in northwest Europe and northern China (Fig. 3). In northwest China, a series of fluvial terraces in the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River was formed between 1 Ma and 0.6 Ma48. In the Weihe drainage Basins of the CLP, where archaeological sites are widespread, river terraces also developed during the MPT49. Dating evidence indicates that several key Mid-Pleistocene archaeological and fossil hominin sites along the Qinling Mountain range were developed on river terrace systems50. In northwest Europe, fluvial terraces expanded significantly across the MPT and were widely distributed in the UK, Spain, and France (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 3. The spatio-temporal distributions and evolution of Pleistocene river terraces across Eurasia.

Two-dimensional kernel density estimation diagrams (a, b) and statistical analysis of Mann–Whitney test (red lines) (c) showing spatio-temporal distributions and evolution of river terraces across the Eurasian continent during the Pleistocene (For detailed information regarding the locations of the river terraces see references in Supplementary Table 2 and also in the Supplementary Information). The red arrows in sub-panels c show the breakpoints of the increased spatial distribution of river terraces determined by the Mann–Whitney test. The log(p) denotes the logarithm of p value of the Mann-Whitney test. When log(p) is less than − 1.3 (corresponding to the p-value < 0.05), the difference is clear, and the changes have statistical significance.

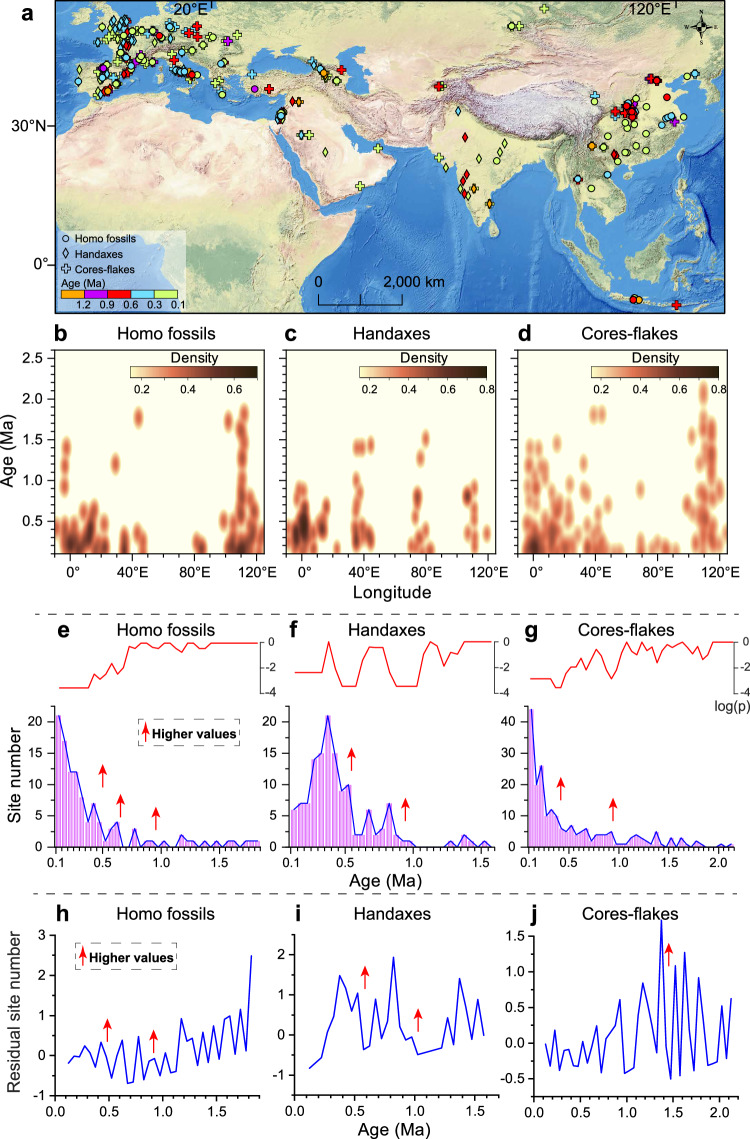

The environmental and geomorphic shifts recorded throughout Eurasia at the MPT are coincident with significant inflection points in the pattern of distribution of fossil hominins and archaeological sites (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 11). In western and southeastern Europe, the earliest human occupation in UK and Serbia has been traced back to 0.9-0.7 Ma and ~ 0.8 Ma, respectively10,51. In Western Europe, a widespread geographic distribution of hominins occurred at ~ 0.8 Ma (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3). Recent studies argued that the earliest stable occupation of hominins in Europe was possibly only since ~ 0.9 Ma51. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction and climate envelope model simulations demonstrate that an extensive glaciation during MIS 34 (~ 1.15 to ~ 1.12 Ma) may have resulted in the depopulation of early human populations in Europe and SW Asia due to the declines in temperature and net primary productivity, and that reoccupation of Europe may have been delayed until during MIS 21 (~ 0.81 to ~ 0.87 Ma)52. The repopulation of Europe after 0.9 Ma may have been made only by a more resilient species (e.g., H. antecessor) that was able to withstand the increased intensity of glacial conditions52. In eastern Asia, the number of archaeological sites changed significantly around the Mid-Pleistocene (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3) and coincident with hominin dispersal into southern China50. In Central Asia, early hominins appeared in Tajikistan at ~ 0.8–0.6 Ma37. In Southwestern Asia, hominins were first present in Syria, Turkey, and Jordan Valley during the time interval between 1 Ma and 0.8 Ma53.

Fig. 4. The spatio-temporal distributions and evolution of Pleistocene archaeological and fossil hominin sites across Eurasia.

Two-dimensional kernel density estimation diagrams (a–d) and statistical analysis of Mann–Whitney test (e–j) showing spatial and temporal distributions of Pleistocene archaeological and fossil hominin sites across Eurasia according to longitude (see references in Supplementary Table 3 for the archaeological site locations). The red arrows in sub-panels e-g show the breakpoints of the trend in the number of Homo fossils, handaxes, and core flakes determined by the Mann–Whitney test. The sub-panels (h–j) show the change point analysis on the residual value of the site number of fossil hominins and artefacts to avoid the influence of sampling bias/burial loss. The log(p) denotes the logarithm of the p-value of the Mann-Whitney test. When log(p) is less than − 1.3 (corresponding to the p-value < 0.05), the difference is clear, and the changes have statistical significance. Handaxes also referred to as bifaces or Large Cutting Tools, are widely regarded as the hallmark of the Acheulian technological systems. It is evident that technological advancements in Eurasia are roughly in parallel with the pronounced expansion of hominin populations. Considering the potential biases in the dating results and the focus of the Mid-Pleistocene time interval in our research, paleoanthropological records younger than 100 kyr were excluded and not discussed in the present study (see “Methods” for further discussion).

Not all fluvial terraces are likely to be preserved over geological time scales, but a widespread occurrence of fluvial terraces during the MPT could exert significant impacts on the availability of fresh water and lithic raw materials (fluvial gravels) for early hominins in Palearctic Eurasia. Well-developed river networks provide the convenience of fishing, access to water, and collecting gravel for tool-making. Growing evidence suggests that technological advancements and increasing toolmaking skills are evident in Eurasia at ~ 0.9-0.6 Ma, in parallel with the change in hominin distributions at this time (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 11). In Western Europe, Acheulean lithic tools from the Guadix-Baza Basin in southern Spain yielded an age of 0.9-0.75 Ma, providing the earliest evidence of handaxes in Europe54. In south and northwest Europe, Acheulean sites in France and Italy, which are characterized by bifaces, cleavers, and other Large Cutting Tools, first appeared at 0.7-0.6 Ma55,56. Hunting techniques also improved with the appearance of wooden spears by or after 450 kyr57.

The Mid-Pleistocene shifts in vegetation and climate overlap with a significant faunal turnover from large-bodied and highly hypsodont fauna toward smaller-bodied and arid-grassland taxa in Eurasia58. In northern China, more than half of early Pleistocene large mammals (> 10 kg) became extinct due to the degradation of forest vegetation at the end of the MPT59. In southwestern Asia, the most significant change in faunal assemblages occurred following the MPT, characterized by the replacement of arid-grassland adapted suids and alcelaphines58. Likewise, in Southeast Asia, the loss or reduction in C4-plant-eating mammals was observed after the MPT17. In southwestern Europe, drier conditions around 0.8 Ma resulted in a high abundance of megaherbivores and the scarcity of forest-adapted mammals44. Landscape and environmental changes had pronounced impacts on the composition of the fauna found in Palearctic Eurasia, reducing forest-adapted groups to extinction whilst providing conditions advantageous to more open-adapted species. These turnovers resulted in a fundamental restructuring of the phylogenetic composition of the assemblages, and thus the biological definition of the Paleartic Realm changed significantly following the MPT.

Landscape shifts and faunal turnover would result in significant changes in the distribution of food resources, which can necessitate modification in hominin diets or technology to cope60,61. Sharing information and raw materials may have facilitated the development and dissemination of Large Cutting Tools to enhance the foraging capacity under the conditions of resource unpredictability61. It is evident that increased ecological resource variability owing to aridity and landscape shifts stimulated technological innovations in Eastern Africa and northern China61–63. Moreover, changes to the availability and reliability of ecosystem services can drive migrations in modern64 and, almost certainly, past hominin populations65, encouraging past hominins to travel more widely and to interact increasingly with other populations.

Our results indicate that enhanced aridity and pronounced landscape shifts promoted Palearctic hominin dispersals during the Mid-Pleistocene, suggesting that the environmental drivers of early hominin dispersals in Eurasia were quite different from those in Africa13,61,66. In northern and eastern Africa, hominin dispersals since the early Pleistocene were likely facilitated by humid periods that created green corridors for out-of-Africa migration67,68. In contrast, our data indicate that in the Asian monsoon-controlled and Westerlies influenced areas, where humid environments and forested landscapes prevailed in the earlier Pleistocene, reduced precipitation and remarkable shifts in geomorphic context since the MPT resulted in widespread aridification and the expansion of more open habitats at the expense of heavily forested environments. As forests retreated and open environments became more prevalent since the MPT, high-intensity wildfires may have occurred more frequently69. By the late Pleistocene, hominin dispersals in Eurasia may have been better facilitated by humid periods when arid climate and steppe/grasslands prevailed70.

The Mid-Pleistocene ecological and landscape shifts would have significant impacts on the spatial and environmental distribution of food resources and the locations of well-watered habitats in Eurasia. These changes placed hominins under environmental and resource pressures, forcing them to range more widely or migrate to new regions while at the same time precipitating improvements in technology complexes. The ready availability of fresh water due to increasing drainage density and lithic raw materials in well-developed river networks in habitats otherwise rendered more arid could also have provided favorable conditions for the dispersals of early hominins and large-bodied grazers by reducing long-distance travel costs. Our analysis indicates that early hominins in southern Palearctic Eurasia were a key group defining the Eurasian Realm following the MPT, as they became more widely dispersed in association with changes in hydrological systems, vegetative habitats, and faunal resources brought about by the dramatic drying conditions of this transition.

Methods

Loess successions in the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan

Loess deposits are widely distributed on surfaces of mountain slopes and river terraces in the southern margin of the Tarim Basin and western margin of the Pamir, where the climate is strongly influenced by the Westerlies (Supplementary Fig. 1). These eolian deposits, which are directly located in downwind directions of the Taklimakan Desert and the Karakum Desert, contain critical information on paleoenvironmental and paleohydrological changes of the Westerlies-influenced regions, i.e., in most areas of Europe and Central Asia. On the western margin of the Pamir Plateau, detailed lithologic and magnetostratigraphic investigations suggest that loess deposits in southern Tajikistan began to accumulate since ~ 2.7 Ma, representing the most complete and oldest loess-paleosol sequence in western Central Asia15. Due to the poor exposure of natural outcrops, a 671 m-deep loess core was recently obtained from the highest fan surface of the southern margin of the Tarim Basin, with a recovery of 96.1%14. Paleomagnetic samples (2 × 2 × 2 cm cubes) were taken at 50 cm intervals in the upper 80 m of the Tarim Basin loess core and at 25 cm intervals in the lower 591 m. A total of 2331 samples gave reliable characteristic remanent magnetizations to determine the magnetostratigraphy. Paleomagnetic and optical stimulated luminescence dating analyses suggest that loess succession from the Tarim Basin was accumulated from ∼ 3.6 Ma to the present14.

Based on chronological constraints of the magnetostratigraphic and OSL analyses, an astronomically tuned age model was established for the 671 m-deep loess core in the Tarim Basin with a temporal resolution of ~ 0.5 kyr, which has been achieved by tuning the grain size record to theoretical variations in the Earth’s orbital parameters14. In addition, an astronomically tuned age model of the Tajikistan loess has been obtained previously by tuning the magnetic susceptibility record to theoretical variations in the Earth’s orbital parameters71. In our study, the timescale of the Tajikistan loess profile, with a temporal resolution of ~ 5–10 kyr, was established based on magnetostratigraphic constraints and the correlation of the magnetic susceptibility record with the marine oxygen isotope results (Supplementary Fig. 2). Previous studies confirmed that the grain size records (representing the intensity of westerlies) of the Tarim Basin loess and the magnetic susceptibility records (reflecting the precipitation variability) of the Tajikistan loess both show a dominant periodicity shift from 41- kyr cyclicity to 100-kyr cyclicity between 1.2 Ma and 0.6 Ma14,71. These features are consistent with global ice volume variability during the MPT (Supplementary Fig. 2), highlighting the reliability of the chronological framework.

Carbon isotope analyses

For the organic matter carbon isotope (δ13Corg) analysis, dried loess samples were first sieved through a mesh to remove modern rootlets and then treated with 4 mol/L HCl for 24 h to remove carbonates at room temperature. After washing with distilled water, the samples were dried for over 24 h at 60 °C. The dried samples were then weighed and sealed in Sn boats. Finally, the isotopic composition was measured using the Elementar IsoPrime 100 isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) instrument linked to a Vario EL cube instrument for elemental analysis, with a precision of ± 0.2‰. The carbon isotope ratios of organic matter are expressed as per mil deviation relative to the Vienna Peedee belemnite (V-PDB) standard.

The δ13Corg values of modern C3 plants and C4 plants respectively vary from − 20‰ to − 34‰ and from − 9‰ to − 19‰, with averages of about − 27‰ for C3 plants and − 13‰ for C4 plants, under modern atmospheric CO2 conditions20,72. The δ13Corg values of ≤ − 24‰ indicate pure C3 vegetation, and the values varying between − 24‰ and − 14‰ indicate C3/C4 mixed vegetation18,19. These observations suggest that the organic matter of loess from the Tarim Basin and Tajikistan was sourced mainly from C3 plants since the late Pliocene, which is consistent with the previous studies of the vegetation types in Central Asia and NW China18,19.

The δ13Corg values in sediments are controlled by complex interactions between several environmental factors, including temperature, precipitation, and pCO2 levels. Early studies demonstrated that a substantial decrease in atmospheric pCO2 accounted for the late Miocene increase in soil carbon isotope ratios73. Recent high-resolution reconstructions of pCO2 in South and East Asia indicate that pCO2 levels appear to be rather stable or increased slightly since the MPT26,27. Meanwhile, a colder climate associated with the intensification of the Northern Hemisphere glaciations since the MPT28 would favor the growth of C3 plants over C4 plants, thereby leading to a significant reduction in δ13Corg. This is not the case in our study, where an increasing trend was observed, suggesting that the temperature had a negligible impact on the changes in δ13Corg. Moreover, maximum δ13Corg values of the Tajikistan loess were observed in the last and penultimate glacial loess units (L1 and L2) under cold and dry climate conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2). Combined with further investigations of the close links between δ13C ratios of modern plants and surface soils and precipitation, these observations suggests that the δ13C values in Central Asia and NW China are less sensitive to temperature variability, but instead are closely related to changes in precipitation18,23. These results are consistent with global scale investigations that indicate a strong negative correlation between precipitation amount and the δ13C of modern C3 plants74.

Previous studies demonstrate that a linear correlation exists between the mean annual precipitation and the δ13Corg of surface soils in Central Asia (Precipitation = (δ13Corg + 22.84)/(-0.0079); n = 44, R2 = 0.44)29 and NW China/Mongolia (Precipitation = – 58 × δ13Corg–1266.5; n = 19, R2 = 0.9)30. Following these observations, a rough estimation of paleoprecipitation changes in south Tajikistan and the Tarim Basin was conducted based on the temporal variations in δ13Corg values. The results demonstrate that the precipitation in Tajikistan was > 500 mm during the early Pleistocene and decreased to ~ 400-300 mm after the Mid-Pleistocene. In the Tarim Basin, the precipitation decreased from ~ 200 mm during the late Pliocene to ~ 100 mm after the MPT.

The δ13C ratios of carbonate from paleosols and fluvial-lacustrine deposits can provide additional information about the paleoenvironmental changes. Different from the δ13C ratios of paleosol carbonate12, carbon isotope values of total carbonate of fluvial-lacustrine deposits in arid regions of Central Asia and NW China are mainly controlled by the carbon isotope compositions and the proportion of detrital and secondary carbonate added to the background signal32,38,75. Increasing evidence suggests that detritus carbonate of fluvial-lacustrine deposits in Central Asia and NW China is mainly sourced from paleo-marine sediments32,38,75. Since the detritus carbonate is highly mixed and well sorted during the sediment transportation, they usually show a constant δ13Ccarb value around 0‰19,32,34,40; whereas in the Qaidam Basin, the background δ13Ccarb signals in detrital carbonates from paleo-marine sediments can be up to 5‰38. As precipitation increases, the δ13Ccarb values of fluvial-lacustrine deposits in arid and semiarid regions of Central Asia and NW China would become progressively negative with increased input of soil organic carbon32,75.

In sum, δ13Corg and δ13Ccarb records of eolian and fluvial-lacustrine sediments in Central Asia and East Asia all show a significant increase since the MPT (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3) supporting the view that enhanced aridification, which can be attributed to the intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations, played a critical role in the Mid-Pleistocene vegetation degradation on the Eurasian continent.

Change-point analysis and the kernel density estimation diagrams

The change point analysis of Mann–Whitney and Ansari–Bradley tests can provide crucial constraints on the rhythms, events and trends in Plio-Pleistocene climate changes of Asia76,77. These statistical approaches, without requiring an assumption of population normality, are non-parametric hypothesis tests78. In this study, we use the ranksum function embedded in Matlab 2016b to perform the Mann-Whitney and Ansari-Bradley tests79.

The statistical measures of change points in the carbon isotope records and other representative dust and sea surface temperature records in Eurasia and the Pacific and Indian Oceans were performed using the 400-600 kyr window. Prior to the change-point analysis to define environmental episodes, the data were interpolated to an evenly spaced time axis. The plots of the Mann–Whitney and Ansari–Bradley test statistics clearly mark the primary transitions in the original data (Supplementary Figs. 3, 9, and 10).

To avoid the influence of sampling bias/burial loss of older archaeological and fossil hominin sites, we perform change point analysis on the residual value of the site number regressed against age by the SMATR package80. These residual values should be, in a sense, “free” of the tendency for an increase in the preservation and documentation of sites closer in time to the present81. In order to capture the non-linear relationship that exists between age and lithics/hominins sites (this most closely resembles an exponential curve), site number was transformed to non-zero values by adding 1, and a reduced major axis (RMA) regression analysis was performed between log (age) and log (site number + 1).

The kernel density estimation diagrams can be used to estimate the population density and spatial distributions of archaeological and fossil hominin sites in a given area based on observed data points. The kernel density estimation diagrams are powerful tools for the visualization of data distribution, providing insights into the structure and characteristics of datasets without imposing strict assumptions about the data distribution. In this study, the bandwidth method of Bivariate Kernel Density Estimator and the density method of Binned Approximate Estimation are employed to show the details in the peaks of the spatial distributions of archaeological and fossil hominin sites, which are performed by the Originpro 2021 software.

Synthesis of archaeological and fossil hominin sites

To examine the spatial and temporal distributions of early hominins in Europe and Asia, the fossil hominin and archaeological records (325 sites, 421 age values) since the Pleistocene were collected across a wider geographic range and shown according to longitude (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3). Considering the potential biases in the dating results and the focus of the Mid-Pleistocene time interval in our research, the paleoanthropological records younger than 100 kyr were excluded and not discussed in the present study. In all of these records, chronological constraints are a critical element in elucidating hominin occupation history in Eurasia. In this study, the early human occupation sites were examined and combined to provide a complete picture of the general patterns and trends in hominin occupation history (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3).

In recent years, the chronological framework of some key archaeological sites has been updated through detailed stratigraphic investigations and the application of new dating technologies. For example, at the ‘Peking Man’ Site in northern China, Zhoukoudian Homo erectus has attributed an age of ~ 0.78 Ma based on 26Al/10Be burial dating, which is corresponding to a relatively mild glacial period82. In the Lantian area of central China, the age of the Gongwangling cranium was updated from 1.15 Ma to ~ 1.63 Ma based on recent paleomagnetic dating3. In addition, the age of some key Acheulian sites in Europe, which are characterized by the emergence of bifaces, cleavers, and other Large Cutting Tools, was updated according to new archaeological discoveries55,83,84. New evidence resulting from the rediscovery and the dating of the Moulin Quignon site in France demonstrates that the first Acheulian occupation north of 50°N occurred around 670–650 ka83. At the Notarchirico site in southern Italy, 40Ar/39Ar and ESR dates place Acheulean culture (including bifaces) between 695 and 670 ka, penecontemporaneous with the Moulin-Quignon and la Noira sites in France85.

As paleoanthropological and fieldwork were continuously performed over the last two decades, new archaeological discoveries challenged the timing of the earliest occupation of the Eurasian continent. For example, the magnetostratigraphic results of the Shangchen archaeological site in the CLP have extended the upper age limit of the earliest human occupation in China to 2.1 Ma, which represents the oldest known evidence of hominins in Eurasia2. Developing a complete picture of the spatio-temporal distributions of hominin occupation history is inevitably influenced by dating uncertainties, sampling gaps, and preservational biases in the archaeological and fossil hominin records. It is important to note that taphonomic loss may contribute to the under-representation of older sites. Indeed, increased paleoanthropological records are evident since the last glacial and Holocene periods86,87, which can be attributed to intense investigations on the archaeological sites because of the availability of suitable dating methods, i.e., the radiocarbon (14C) and OSL dates. For the current dataset, the age of paleoanthropological records older than 100 kyr was primarily constrained by paleomagnetic, electron spin resonance (ESR), cosmogenic burial (26Al and 10Be), and U-series dating analyses.

In addition, it is important to note that dating errors may emerge in some fossil hominin and archaeological sites in Eurasia. To clarify the potential influences of dating uncertainties on the spatial and temporal distributions of archaeological records, the kernel density estimation diagrams of archaeological and fossil hominin sites with the maximum and minimum (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12 and Supplementary Table 3), and mean (Fig. 4) age estimations derived from the dating errors were investigated. There are no obvious differences in the patterns of the paleoanthropological records, and an expansion in the spatial distribution of fossil hominins and artefacts in Eurasia is evident at ~ 0.9–0.6 Ma. In contrast, the residual value of the site number of fossil hominins and artefacts in the current dataset does not show a significant increase through time during the Early and Middle Pleistocene. However, marked inflection points in these distributions are consistently observed around the MPT (Fig. 4h–j and Supplementary Fig. 11g–i and p–r). This commonality suggests they aren’t artefacts of any biases present in our dataset but rather represent genuine changes in the distribution of hominin, handaxe, and archaeological sites. However, these data also suggest that these changes may not have occurred synchronously. Determining the relative timings of increases in archaeological sites and/or handaxe occurrences versus records of hominin remains is a geological question that will require much finer-scale considerations of how taphonomic factors control preservation than we currently have available. As such, our results echo the cautionary note of researchers working on the African hominin records regarding the need for better confidence intervals on the stratigraphic ranges of hominins and their proxies, and stronger efforts to identify, discuss, and correct fossil sampling biases88. Nevertheless, the current dataset represents the largest compilation of archaeological records in Europe and Asia that suggests, despite taphonomic and sampling limitations, broadly increasing trends in the distribution of hominin dispersals in Eurasia since the MPT (see Discussion).

Synthesis of carbon isotope and paleontological records

Stable carbon isotopic ratios of sediments are generally regarded as sensitive indicators to unravel the changes in vegetation types (C3, C4, and Crassulacean acid metabolism plants; Crassulacean acid metabolism plants are a group of plants that have adapted to arid environments by opening their stomata at night to take in carbon dioxide) and vegetation cover12,13,73. In this study, carbon isotopic data of organic matter or total carbonate of fluvial-lacustrine and eolian sediments from the Asian monsoon-controlled and Westerlies-influenced areas are compiled for further analysis (Fig. 2). More specifically, lacustrine sediments from the Tarim Basin and Qaidam Basin provide critical stable carbon isotopic records of carbonate in the Westerlies-influenced region. In the Asian monsoon-controlled areas, carbon isotopic records of eolian sediments from the CLP and the adjacent regions are compiled for further synthesis. Paleomagnetic dating results, combined with further stratigraphic correlation of the magnetic susceptibility record and/or calibration of the astronomically tuned timescale, provide reliable age controls on these eolian and fluvial-lacustrine sediment sequences. It is evident that the δ13Corg and δ13Ccarb records all show a prominent increase since the MPT (Fig. 2).

Pollen records, which are distributed from northeastern China throughout southeastern Tibet, cover a wide geographic range in East Asia and Central Asia. Paleomagnetic dating analyses provide reliable age controls for these records. Vegetation types in most areas of East Asia show a remarkable shift from forest to open forest at 1.2-1 Ma and subsequently changed from open forest steppe to steppe at ~ 0.9-0.6 Ma (Supplementary Fig. 4), which are roughly consistent with the results of carbon isotopic analyses and the pollen records in Eurasia (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5)42,51,59,89–95. In SE Tibet, glacial periods were longer and dominated by steppe and meadows after the MPT16. These observations are also consistent with the results of vegetation change inferred from large mammal communities in Europe44 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Spatio-temporal distributions of eolian deposits and river terraces

In recent years, increasing fieldwork and detailed paleomagnetic studies have been carried out to investigate the spatial and temporal distributions of eolian loess deposits in sub-humid and humid regions of China and Europe. A synthesis of the initial timing and spatial distribution of late Cenozoic eolian deposits in Eurasia suggests that, during the pre-MPT, loess deposits are confined to arid and semi-arid regions in Central Asia and northwestern China (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1). Whereas during the MPT the Eurasian loess belt expanded significantly and has extended to northeastern and southern China and the Danube River drainage area in Europe. Hence, the Middle Pleistocene is a critical period for the establishment of modern-like loess landscapes in sub-humid and humid regions of China and Europe. Increasing dust fluxes of marine sediments from the Mediterranean Sea, the Arabian Sea, and the North Pacific Ocean provide further support for the occurrence of continental aridification and expansion of the Eurasian loess belt during the MPT, which led to a pronounced increase in eolian sediment supply from the terrestrial dust sources across Eurasia to the downwind oceans96–98 (Supplementary Figs. 8a–e and 9). The formation of continuous loess succession requires a sizeable source region to provide silt materials and a stable and open environment to hold dust particles. We argue that the increased ice volume and climate fluctuation amplitude, as well as lowering sea levels and base level since the MPT28,99, would lead to a dramatic intensification of the glacial erosion and river incision on the Northern Hemisphere100,101, thereby producing a vast amount of silt materials necessary to form desert-loess landscapes. Moreover, increased ice volume can reduce the sea surface temperatures (SSTs)102–105 (Supplementary Fig. 8g–l) and weaken oceanic water evaporation. Consequently, a substantial decrease in moisture supply would enhance the aridity in Eurasia14,46, which would provide stable and open environments for the accumulation of loess deposits.

A widespread occurrence of fluvial terraces could exert significant impacts on the availability of fresh water and lithic raw materials (fluvial gravels) for early hominins in Palearctic Eurasia. Exploring the spatiotemporal patterns of river terraces in Eurasia (277 sites, 1520 age values) is inevitably influenced by age uncertainties, preservational biases, and visibility of the river terrace systems. Generally speaking, the river terrace systems in the arid and semi-arid regions of Central Asia and NW China are usually well preserved and discernable due to the weak weathering and sparse vegetation. Meanwhile, OSL, cosmogenic burial, and paleomagnetic dating analyses provide useful methods to constrain the age of the fluvial terraces. Thus, the spatio-temporal patterns of river terraces in Central Asia and NW China are clearly discernable and believable. In contrast, river terrace data in tropical areas of South and Southeast Asia is relatively limited (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2), which can be attributed to poor preservation because of intensive chemical weathering or the problems of site visibility because of dense vegetation. Another prominent feature of the current dataset is the widespread occurrence of fluvial terraces since the last glacial and interglacial periods. The widespread occurrence of river terraces since the last glacial and interglacial periods can be attributed to intense investigations on the river terrace systems because of the availability of suitable dating methods, i.e., the OSL, organic matter 14C, and TL. In contrast, the age of river terrace systems older than 100 kyr in the current dataset was primarily constrained by paleomagnetic, electron spin resonance (ESR), cosmogenic burial (26Al and 10Be), and U-series dating analyses (Supplementary Table 2), which generally show a long-time span from hundreds of thousands of years to millions of years. Hence, potential biases in the dating results of these old river terraces do not disturb the general patterns, and an increasing trend of the number of fluvial terraces in northwestern Europe and northwestern China during the MPT should be discernable and believable.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Jian Kang, Shengli Yang, Weiming Liu, Zhigao Zhang, and Yudong Liu for their assistance in collecting samples. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFF0804500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China BSCTPES project (41988101-01), and the Second Scientific Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) (Grant No. 2019QZKK0602).

Author contributions

J.B.Z. designed the research. J.B.Z., J.L., R.D., M.P., and X.M.F. wrote the paper. J.B.Z., W.X.N., W.L.Z., and Z. H. collected the data and performed the analysis. W.X.N. compiled the archaeological records and produced the corresponding visual representations.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Polychronis Tzedakis, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data generated and used during this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Source data are provided in this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jinbo Zan, Email: zanjb@itpcas.ac.cn.

Julien Louys, Email: j.louys@griffith.edu.au.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54767-0.

References

- 1.Holt, B. G. et al. An update of Wallace’s Zoogeographic regions of the world. Science339, 74–78 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu, Z. Y. et al. Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago. Nature559, 608–612 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu, Z. Y. et al. New dating of the Homo erectus cranium from Lantian (Gongwangling), China. J. Hum. Evol.78, 144–157 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabunia, L. et al. Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science288, 1019–1025 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermúdez de Castro, J. M. et al. Early Pleistocene human mandible from Sima del Elefante (TE) cave site in Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain): a comparative morphological study. J. Hum. Evol.61, 12–25 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oms, O., Anadón, P., Agustì, J. & Julià, R. Geology and chronology of the continental Pleistocene archeological and paleontological sites of the Orce area (Baza basin, Spain). Quat. Int.243, 33–43 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arzarello, M., Peretto, C. & Moncel, M.-H. The Pirro Nord site (Apricena, Fg, Southern Italy) in the context of the first European peopling: Convergences and divergences. Quat. Int.389, 255–263 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennell, R. W. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Asia (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

- 9.Finestone, E. M. et al. Paleolithic occupation of arid Central Asia in the Middle Pleistocene. PLoS ONE17, e0273984 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parfitt, S. A. et al. Early Pleistocene human occupation at the edge of the boreal zone in northwest Europe. Nature466, 229–233 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamilar, J. M., Beaudrot, L. & Reed, K. E. Climate and species richness predict the phylogenetic structure of African mammal communities. PLoS ONE10, e0121808 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerling, T. E. et al. Woody cover and hominin environments in the past 6 million years. Nature476, 51–56 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin, N. E. Environment and climate of early human evolution. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci.43, 405–429 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang, X. M. et al. The 3.6-Ma aridity and westerlies history over midlatitude Asia linked with global climatic cooling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA117, 24729–24734 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zan, J. et al. Intensified Northern Hemisphere glaciation facilitates continuous accumulation of late Pliocene loess on the western margin of the Pamir. Geophys. Res. Lett.49, e2022GL099629 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao, Y. et al. Evolution of vegetation and climate variability on the Tibetan Plateau over the past 1.74 million years. Sci. Adv.6, eaay6193 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louys, J. & Roberts, P. Environmental drivers of megafauna and hominin extinction in Southeast Asia. Nature586, 402–406 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao, Z. et al. Relationship between the stable carbon isotopic composition of modern plants and surface soils and climate: A global review. Earth Sci. Rev.165, 110–119 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, W., Yang, H., Sun, Y. & Wang, X. δ13C values of loess total carbonate: A sensitive proxy for Asian monsoon rainfall gradient in arid northwestern margin of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Chem. Geol.284, 317–322 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farquhar, G. D., Ehleringer, J. R. & Hubick, K. T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol.40, 503–537 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, Q. et al. Holocene moisture variations in western arid Central Asia inferred from loess records from NE Iran. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.21, e2019GC008616 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, G. A., Han, J. M. & Liu, T. S. The carbon isotope composition of C3 herbaceous plants in loess area of northern China. Sci. China Earth Sci.46, 1069–1076 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao, Z. G., Xu, Y. B., Xia, D. S., Xie, L. H. & Chen, F. H. Variation and paleoclimatic significance of organic carbon isotopes of Ili loess in arid Central Asia. Org. Geochem.63, 56–63 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartoli, G., Hönisch, B. & Zeebe, R. E. Atmospheric CO2 decline during the Pliocene intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations. Paleoceanography26, PA4213 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Botí, M. et al. Plio-Pleistocene climate sensitivity evaluated using high-resolution CO2 records. Nature518, 49–54 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Da, J. W., Zhang, Y. G., Li, G., Meng, X. Q. & Ji, J. F. Low CO2 levels of the entire Pleistocene epoch. Nat. Commun.10, 4342 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto, M. et al. Increased interglacial atmospheric CO2 levels followed the mid-Pleistocene transition. Nat. Geosci.15, 307–313 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westerhold, T. et al. An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years. Science369, 1383–1387 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, Q. et al. Climatic significance of the stable carbon isotopic composition of surface soils in northern Iran and its application to an Early Pleistocene loess section. Org. Geochem.127, 104–114 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, X. Q. et al. Carbon isotope of bulk organic matter: a proxy for precipitation in the arid and semiarid central East Asia. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles19, 2833–2845 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balsam, W. L. et al. Magnetic susceptibility as a proxy for rainfall: Worldwide data from tropical and temperate climate. Quat. Sci. Rev.30, 2732–2744 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, W. G. et al. Onset of permanent Taklimakan Desert linked to the mid-Pleistocene transition. Geology48, 782–786 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donohue, R. J., Roderick, M. L., McVicar, T. R. & Farquhar, G. D. Impact of CO2 fertilization on maximum foliage cover across the globe’s warm, arid environments. Geophys. Res. Lett.40, 3031–3035 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun, Y. et al. Astronomical and glacial forcing of East Asian summer monsoon variability. Quat. Sci. Rev.115, 132–142 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, F. L., Fang, X. M. & Miao, Y. F. Aridification history of the West Kunlun Mountains since the mid-Pleistocene based on sporopollen and microcharcoal records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.547, 109680 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, F. et al. Heading north: Late Pleistocene environments and human dispersals in central and eastern Asia. PLoS ONE14, e0216433 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranov, V. The ‘Loessic Palaeolithic’ in South Tadjikistan, Central Asia: Its industries, chronology and correlation. Quat. Sci. Rev.14, 731–745 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han, W. X. et al. Climate transition in the Asia inland at 0.8-0.6 Ma related to astronomically forced ice sheet expansion. Quat. Sci. Rev.248, 106580 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, F. et al. A 1200 ka stable isotope record from the center of the Badain Jaran Desert, Northwestern China: Implications for the variation and interplay of the Westerlies and the Asian summer monsoon. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.22, e2020GC009575 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun, J., Lü, T., Zhang, Z., Xu, W. & Liu, W. Stepwise expansions of C4 biomass and enhanced seasonal precipitation and regional aridity during the Quaternary on the southern Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev.34, 57–65 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. Decoupling of soil nutrient cycles as a function of aridity in global drylands. Nature502, 672–676 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzedakis, P. C., Hooghiemstra, H. & Palike, H. The last 1.35 million years at Tenaghi Philippon: revised chronostratigraphy and long-term vegetation trends. Quat. Sci. Rev.25, 3416–3430 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magri, D., Di Rita, F., Aranbarri, J., Fletcher, W. & Gonzalez-Samperiz, P. Quaternary disappearance of tree taxa from Southern Europe: timing and trends. Quat. Sci. Rev.163, 23–55 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahlke, R. D. et al. Western Palaearctic palaeoenvironmental conditions during the Early and early Middle Pleistocene inferred from large mammal communities, and implications for hominin dispersal in Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev.30, 1368–1395 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao, H., Sun, Y. B. & Qiang, X. K. Mid-Pleistocene formation of modern-like desert landscape in North China. Catena216, 106399 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding, Z. L., Derbyshire, E., Yang, S. L., Sun, J. M. & Liu, T. S. Stepwise expansion of desert environment across northern China in the past 3.5 Ma and implications for monsoon evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.237, 45–55 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, H., Li, C. R. & Kuman, K. Rethinking the “Acheulean” in East Asia: evidence from recent investigations in the Danjiangkou Reservoir Region, central China. Quat. Int.347, 163–175 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu, Z. B. et al. The linking of the upper-middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River as a result of fluvial entrenchment. Quat. Sci. Rev.166, 324–338 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao, H. S., Li, Z. M., Ji, Y. P., Pan, B. T. & Liu, X. F. Climatic and tectonic controls on strath terraces along the upper Weihe River in central China. Quat. Res.86, 326–334 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang, S. X. et al. Hominin site distributions and behaviours across the Mid-Pleistocene climate transition in China. Quat. Sci. Rev.248, 106614 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muttoni, G., Scardia, G. & Kent, D. V. Early hominins in Europe: The Galerian migration hypothesis. Quat. Sci. Rev.180, 1–29 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Margari, V. et al. Extreme glacial cooling likely led to hominin depopulation of Europe in the Early Pleistocene. Science381, 693–699 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bar-Yosef, O. & Belmaker, M. Early and Middle Pleistocene Faunal and hominins dispersals through Southwestern Asia. Quat. Sci. Rev.30, 1318–1337 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott, G. R. & Gibert, L. The oldest hand-axes in Europe. Nature461, 82–85 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moncel, M. H., Despriée, J., Courcimaut, G., Voinchet, P. & Bahain, J. J. La Noira Site (Centre, France) and the technological behaviours and skills of the earliest Acheulean in western Europe between 700 and 600 ka. J. Paleolit. Archaeol.3, 255–301 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.García-Medrano, P., Moncel, M. H., Maldonado-Garrido, E., Ollé, A. & Ashton, N. The Western European Acheulean: Reading variability at a regional scale. J. Hum. Evol.179, 103357 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thieme, H. Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature385, 807–810 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stewart, M. et al. Middle and Late Pleistocene mammal fossils of Arabia and surrounding regions: Implications for biogeography and hominin dispersals. Quat. Int.515, 12–29 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou, X. Y. et al. Vegetation change and evolutionary response of large mammal fauna during the Mid-Pleistocene Transition in temperate northern East Asia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.505, 287–294 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 60.El Zaatari, S., Grine, F. E., Ungar, P. S. & Hublin, J. J. Neandertal versus modern human dietary responses to climatic fluctuations. PloS ONE11, e0153277 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Potts, R. et al. Increased ecological resource variability during a critical transition in hominin evolution. Sci. Adv.6, eabc8975 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, S. X. et al. Technological innovations at the onset of the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition in high-latitude East Asia. Natl. Sci. Rev.8, nwaa053 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang, S. X., Deng, C. L., Zhu, R. X. & Petraglia, M. D. The Paleolithic in the Nihewan Basin, China: Evolutionary history of an Early to Late Pleistocene record in Eastern Asia. Evol. Anthropol.29, 125–142 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Black, R. et al. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Chang.21, S3–S11 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou, B. et al. Hominin response to oscillations in climate and local environments during the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition in Northern China. Geophys. Res. Lett.50, e2023GL104931 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 66.deMenocal, P. B. Plio-Pleistocene African climate. Science270, 53–59 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Timmermann, A. & Friedrich, T. Late Pleistocene climate drivers of early human migration. Nature538, 92–95 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Castañeda, I. S. et al. Wet phases in the Sahara/Sahel region and human migration patterns in North Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA106, 20159–20163 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han, Y. et al. Asian inland wildfires driven by glacial–interglacial climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA117, 5184–5189 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ao, H. et al. Concurrent Asian monsoon strengthening and early modern human dispersal to East Asia during the last interglacial. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA121, e2308994121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ding, Z. L. et al. The loess record in southern Tajikistan and correlation with Chinese loess. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.200, 387–400 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deines, P. The Isotopic Composition of Reduced Organic Carbon. Vol. 1 309–406 (Elsevier, 1980).

- 73.Cerling, T. E. et al. Global vegetation change through the Miocene/Pliocene boundary. Nature389, 153–158 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diefendorf, A. F., Mueller, K. E., Wing, S. L., Koch, P. L. & Freeman, K. H. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 5738–5743 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caves, J. K. et al. The neogene de-greening of Central Asia. Geology44, 887–890 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trauth, M. H., Larrasoaña, J. C. & Mudelsee, M. Trends, rhythms and events in Plio–Pleistocene African climate. Quat. Sci. Rev.28, 399–411 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Foerster, V. et al. Pleistocene climate variability in eastern Africa influenced hominin evolution. Nat. Geosci.15, 805–811 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lepage, Y. A combination of Wilcoxon’s and Ansari-Bradley’s statistics. Biometrika58, 213–217 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trauth, M. H. MATLAB ® Recipes for Earth Sciences. Vol. 5th Edition (Springer Cham, 2020).

- 80.Falster, D. S., Warton, D. I. & Wright, I. J. User’s guide to SMATR: Standardised major axis tests and routines, ver 2.0 (2006).

- 81.Maxwell, S. J., Hopley, P. J., Upchurch, P. & Soligo, C. Sporadic sampling, not climatic forcing, drives early hominin diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA115, 4891–4896 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shen, G., Gao, X., Gao, B. & Granger, D. E. Age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus determined with 26Al/ 10Be burial dating. Nature458, 198–200 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Antoine, P. et al. The earliest evidence of Acheulian occupation in Northwest Europe and the rediscovery of the Moulin Quignon site, Somme valley, France. Sci. Rep.9, 13091 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moncel, M. H., Ashton, N., Lamotte, A., Tuffreau, A. & Despriée, J. The Early Acheulian of north-western Europe. J. Anth. Arch.40, 302–331 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moncel, M. H. et al. The origin of early Acheulean expansion in Europe 700 ka ago: new findings at Notarchirico (Italy). Sci. Rep.10, 13802 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crema, E. R., Bevan, A. & Shennan, S. Spatio-temporal approaches to archaeological radiocarbon dates. J. Archaeol. Sci.87, 1–9 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Surovell, T. A., Byrd Finley, J., Smith, G. M., Brantingham, P. J. & Kelly, R. Correcting temporal frequency distributions for taphonomic bias. J. Archaeol. Sci.36, 1715–1724 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hopley, P. J. & Maxwell, S. J. Environmental and Stratigraphic Bias in the Hominin Fossil Record. 15–23 (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

- 89.Magri, D. & Palombo, M. R. Early to Middle Pleistocene dynamics of plant and mammal communities in South West Europe. Quat. Int.288, 63–72 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuan, B. Y. et al. The age, subdivision and correlation of Nihewan Group. Sci. China Earth Sci.26, 67–73 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu, F. et al. Plio-Quaternary stepwise drying of Asia: Evidence from a 3-Ma pollen record from the Chinese Loess Plateau. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.257, 160–169 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cai, M. T., Fang, X. M., Wu, F. L., Miao, Y. F. & Appel, E. Pliocene–Pleistocene stepwise drying of Central Asia: Evidence from paleomagnetism and sporopollen record of the deep borehole SG-3 in the western Qaidam Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Planet. Chang.94–95, 72–81 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cai, M. T., Xu, D. N., Wei, M. J., Wang, J. P. & Pan, B. L. Vegetation and climate change in the Beijing plain during the last million years and implications for Homo erectus occupation in North China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.432, 29–35 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li, J. Q. et al. Characteristics of environmental changes during the Mid-Pleistocene transition period in the Changzhi Basin, Shanxi Province. Acta Geol. Sin.95, 3532–3543 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shen, H. et al. Early and Middle Pleistocene vegetation and its impact on faunal succession on the Liaodong Peninsula, Northeast China. Quat. Int.591, 15–23 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Larrasoaña, J. C., Roberts, A. P., Rohling, E. J., Winklhofer, M. & Wehausen, R. Three million years of monsoon variability over the northern Sahara. Clim. Dyn.21, 689–698 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Clemens, S. C., Murray, D. W. & Prell, W. L. Nonstationary phase of the Plio-Pleistocene Asian monsoon. Science274, 943–948 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rea, D. K., Snoeckx, H. & Joseph, L. H. Late Cenozoic eolian deposition in the North Pacific: Asian drying, Tibetan uplift, and cooling of the northern hemisphere. Paleoceanography13, 215–224 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Boer, B., Lourens, L. J. & van de Wal, R. S. Persistent 400,000-year variability of Antarctic ice volume and the carbon cycle is revealed throughout the Plio-Pleistocene. Nat. Commun.5, 2999 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Molnar, P. & England, P. Late Cenozoic uplift of mountain ranges and global climate change: chicken or egg? Nature346, 29–34 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bender, A. M. et al. Late Cenozoic climate change paces landscape adjustments to Yukon River capture. Nat. Geosci.13, 571–575 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 102.Emeis, K. C. et al. Eastern Mediterranean surface water temperatures and δ18O composition during deposition of sapropels in the late Quaternary. Paleoceanography18, 1005 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 103.Herbert, T. D., Peterson, L. C., Lawrence, K. T. & Liu, Z. Tropical ocean temperatures over the past 3.5 million years. Science328, 1530–1534 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Herbert, T. D. et al. Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems. Nat. Geosci.9, 843–847 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Snyder, C. W. Evolution of global temperature over the past two million years. Nature538, 226–228 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and used during this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Source data are provided in this paper.