Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

Scant data are available on syphilis infection within migrant populations worldwide and in the population of the Middle East and North Africa region. This study investigated the prevalence of both lifetime and recent syphilis infections among migrant craft and manual workers (MCMWs) in Qatar, a diverse demographic representing 60% of the country’s population.

Methods

Sera specimens collected during a nationwide cross-sectional survey of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among the MCMW population, conducted between 26 July and 9 September 2020, were analysed. Treponema pallidum antibodies were detected using the Mindray CL-900i Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Analyzer. To differentiate recent infections, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing was performed, with an RPR titre of ≥1:8 considered indicative of recent infection. Logistic regression analyses were employed to identify factors associated with lifetime syphilis infection. Sampling weights were incorporated into all statistical analyses to obtain population-level estimates.

Results

T. pallidum antibodies were identified in 38 of the 2528 tested sera specimens. Prevalence of lifetime infection was estimated at 1.3% (95% CI 0.9% to 1.8%). Among the 38 treponemal-positive specimens, 15 were reactive by RPR, with three having titres ≥1:8, indicating recent infection. Prevalence of recent infection was estimated at 0.09% (95% CI 0.01 to 0.3%). Among treponemal-positive MCMWs, the estimated proportion with recent infection was 8.1% (95% CI: 1.7 to 21.4%). The adjusted OR for lifetime infection increased with age, reaching 8.68 (95% CI 2.58 to 29.23) among those aged ≥60 years compared with those ≤29 years of age. Differences in prevalence were observed by nationality and occupation, but no differences were found by educational attainment or geographic location.

Conclusions

Syphilis prevalence among MCMWs in Qatar is consistent with global levels, highlighting a disease burden with implications for health and social well-being. These findings underscore the need for programmes addressing both sexually transmitted infections and the broader sexual health needs of this population.

Keywords: Syphilis, Sexually Transmitted Disease, Epidemiology

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The study was conducted on a large, nationally representative sample and on a population representing 60% of Qatar’s total population.

The study assessed the prevalence of both lifetime and recent syphilis infections and investigated associations with lifetime infection.

Syphilis diagnosis is inherently complex due to the lack of precise and direct diagnostic tools for current infection, potentially leading to an underestimation of the prevalence of recent infection.

Although the study was designed to employ a probability-based sampling approach, logistical challenges necessitated the adoption of a systematic sampling method.

The study did not have access to participants‘ medical records and did not collect sexual behaviour data, limiting the ability to associate infection with clinical histories and sexual behaviour.

Introduction

Syphilis, a common sexually transmitted infection (STI), is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum.1 The initial stages of infection often present with mild and easily overlooked symptoms.2 Left untreated, syphilis can inflict damage on the nervous and reproductive health systems, potentially leading to serious or fatal outcomes.1 3 The primary mode of syphilis transmission is through sexual contact,1 3 but it can also be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth, resulting in congenital syphilis—a significant contributor to global foetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.4 5 The asymptomatic nature of the infection in a substantial proportion of cases complicates its control.1

The WHO estimated 6.3 million new cases in 2016, with the majority occurring in low- and middle-income countries.6 The WHO’s Global Health Sector Strategy on STIs for 2022–2030 aims to decrease the overall incidence of syphilis by 90% and the incidence of congenital syphilis to less than 50 cases per 100 000 live births by 2030.7 Monitoring progress towards these global targets necessitates a regular assessment of syphilis prevalence in the population.

Qatar, situated in the Arabian Peninsula, has a unique demographic profile. Only 9% of its residents are aged 50 or older, and a significant 89% are expatriates hailing from more than 150 countries.8 Among these residents, about 60% comprise migrant craft and manual workers (MCMWs), predominantly single men aged 20–49, working in large-scale development projects such as those associated with the World Cup 2022.9 10 Against a backdrop of poorly documented STI prevalence levels in migrant populations11 12 and in the Middle East and North Africa region,13 14 the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of both lifetime and recent syphilis infections among the expatriate MCMW population, a predominant segment of Qatar’s population, with the aim of providing insights for national health policy planning.

Methods

Study design and sampling

This study examined blood sera specimens collected from MCMWs during a nationwide serological survey conducted between 26 July 2020 and 9 September 2020.915,17 The survey aimed to determine the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among the MCMW population,9 which was identified as the population group most affected by the first SARS-CoV-2 infection wave in Qatar.8 18

A sampling strategy for the MCMW population was formulated through an analysis of the registered users’ database of the Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS), the primary healthcare provider for MCMWs in the country.9 QRCS oversees four strategically located centres, specifically designed to cater to the MCMW population across the country. These centres operate extended hours, are situated in areas where workers reside and provide services either free of charge or with substantial subsidies, ensuring accessibility and affordability. To ensure sample representativeness, the probability distribution of MCMWs by age and nationality from the QRCS database was compared with that of expatriate residents from the Ministry of Interior database.19

Given that men constitute the overwhelming majority of MCMWs (>99%),20 the sampling strategy did not explicitly account for sex. The recruitment of MCMWs was conducted at the QRCS centres using a systematic sampling approach, guided by the average daily attendance at each centre.9 The recruitment process at each centre involved inviting every fourth attendee to participate in the study until the required sample size was achieved across all age and nationality strata. To overcome challenges in recruiting participants in smaller age-nationality strata, especially among younger individuals of certain nationalities, the recruitment criteria were adjusted towards the end of the study. In these instances, all attendees in these strata were invited to participate, rather than every fourth attendee.

Sample collection and handling

Trained interviewers collected written informed consent and the study instrument from participants, using any of nine languages: Arabic, Bengali, English, Hindi, Nepali, Sinhala, Tagalog, Tamil and Urdu, depending on the participant’s language preference.9 The instrument, designed in accordance with WHO guidance for developing SARS-CoV-2 sero-epidemiological surveys,21 gathered essential sociodemographic information. Certified nurses drew a 10-mL blood sample for serological testing, which was then stored in an icebox before transportation to the Qatar Biobank for subsequent testing and long-term storage.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Laboratory methods

A 150 µL aliquot of serum was extracted from the stored serum specimens at the Qatar Biobank and then transferred to the virology laboratory at Qatar University for serological testing. The sera at both the Qatar Biobank and Qatar University were maintained at −80°C until used for serology testing. Lifetime syphilis infection (indicating ever having been infected with syphilis) was determined by testing sera for T. pallidum antibodies using the automated Mindray CL-900i Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Analyzer (Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics, Shenzhen, China).22 23

The testing results were interpreted in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Sera were categorised as negative if index values were <1.00 and positive if index values were ≥2.00. Intermediate values (1.00 ≤index values <2.00) were considered equivocal and underwent centrifugation, followed by duplicate retesting using the same kit. Specimens with values <1.00 in both retests were classified as negative, while those with values≥1.00 in either of the retests were considered positive.

Positive specimens were subsequently subjected to rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing at the Laboratory Section of the Medical Commission Department of the Ministry of Public Health. RPR testing was done using the RPR Carbon Antigen kit (Fortress Diagnostics Limited, UK)24 where titres ≥1:8 were deemed indicative of a recent (within a year) syphilis infection.25 26 Detailed methods for the RPR testing and the quality control/quality assurance procedures can be found in online supplemental section S1.24 27

In this study, the test results were interpreted to distinguish recent from lifetime infection, with no utilisation of terms such as active, latent or secondary syphilis. This approach was adopted due to the study’s emphasis on the epidemiology of the infection rather than clinical interpretation, taking into account that the assays employed assess seroreactivity against syphilis rather than the actual presence of the pathogen.

Oversight

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of Hamad Medical Corporation (MRC 05 133), Qatar University (QU-IRB 1558-EA/21) and Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar (21–00002). The reporting of the study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines, as detailed in online supplemental table S1.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of study participants were described through frequency distributions and measures of central tendency. To address the unequal selection of participants and ensure the sample’s representativeness of the broader MCMW population, probability weights were applied to all statistical analyses. These weights were calculated based on the population distribution of MCMWs by age, nationality and QRCS centre, as obtained from the QRCS registered-user database.9

The weighted prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection in the study population was estimated. The weighted prevalence of recent syphilis infection was also calculated, applying logistic regression-based multiple imputations with 1000 iterations. This imputation process addressed a single treponemal-positive specimen that had sufficient sera for T. pallidum antibody testing using the Mindray CL-900i Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Analyzer but lacked enough sera for RPR testing. This method predicted the missing value based on the characteristics of participants with treponemal-positive specimens and complete RPR test results. The imputed dataset was also used to calculate the proportion of recent infections among treponemal-positive MCMWs.

A histogram was employed to visually depict the distribution of index values assessing T. pallidum antibodies in sera among the treponemal-positive specimens. The association between the T. pallidum antibody index value and the RPR titres was examined using the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Associations with lifetime syphilis infection were explored through χ2 tests and bivariable logistic regression analyses. Variables with a p value ≤0.2 in the bivariable regression analysis were included in the multivariable model. A p value<0.05 in the multivariable analysis was considered indicative of a statistically significant association. The sampling probability weights were applied in the regression analyses. The study reported unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs and AORs, respectively), along with their respective 95% CIs and p values. Interactions were not considered in this analysis. Associations with recent syphilis infection could not be explored due to the limited number of cases. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE V.18.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study population

Table 1 describes the characteristics of study participants. Out of the 2641 blood specimens collected from MCMWs during the original SARS-CoV-2 survey,9 only 2528 (95.7%) retained sufficient sera for syphilis testing and were consequently included in the study.

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants and prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection among the craft and manual worker population in Qatar.

| Characteristics | Total tested | Lifetime syphilis infection | ||

| N (%*) | N | %† (95% CI†) | χ2 p value | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤29 | 719 (27.4) | 7 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.8) | 0.001 |

| 30–39 | 940 (41.9) | 8 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.8) | |

| 40–49 | 534 (21.6) | 14 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.9) | |

| 50–59 | 249 (7.4) | 4 | 1.4 (0.5 to 4.0) | |

| 60+ | 86 (1.7) | 5 | 6.6 (2.7 to 15.3) | |

| Nationality | ||||

| Bangladeshi | 603 (26.0) | 7 | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) | 0.047 |

| Egyptian | 86 (3.1) | 1 | 1.5 (0.2 to 9.6) | |

| Filipino | 99 (2.7) | 1 | 0.3 (0.05 to 2.4) | |

| Indian | 699 (29.4) | 7 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.3) | |

| Nepalese | 552 (21.8) | 7 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) | |

| Pakistani | 132 (4.9) | 4 | 2.2 (0.8 to 6.2) | |

| Sri Lankan | 138 (4.7) | 2 | 0.8 (0.2 to 4.0) | |

| All other nationalities‡ | 219 (7.4) | 9 | 4.0 (2.0 to 7.7) | |

| QRCS centre (catchment area within Qatar) | ||||

| Fereej Abdel Aziz (Doha-East) | 558 (22.1) | 9 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.7) | 0.525 |

| Zekreet (North-West) | 234 (2.3) | 6 | 2.5 (1.1 to 5.5) | |

| Hemaila (South-West; ‘Industrial Area’) | 942 (42.3) | 12 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) | |

| Mesaimeer (Doha-South) | 794 (33.3) | 11 | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Primary or lower | 611 (24.8) | 9 | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.8) | 0.187 |

| Intermediate | 416 (17.9) | 11 | 1.9 (1.0 to 3.6) | |

| Secondary/high school/vocational | 1058 (44.3) | 14 | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.3) | |

| University | 348 (12.9) | 3 | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.5) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Professional workers§ | 126 (4.6) | 1 | 0.7 (0.1 to 4.8) | 0.110 |

| Food and beverage workers | 85 (3.0) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | |

| Administration workers | 79 (3.0) | 1 | 1.6 (0.2 to 10.7) | |

| Retail workers | 162 (6.5) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | |

| Transport workers | 410 (16.1) | 11 | 2.3 (1.2 to 4.2) | |

| Security workers | 57 (2.3) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | |

| Cleaning workers | 102 (4.0) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | |

| Technical and construction workers¶ | 1290 (53.6) | 19 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) | |

| Other workers** | 168 (6.8) | 5 | 2.9 (1.2 to 6.8) | |

| Total (%, 95% CI) | 2528 (100.0) | 38 | 1.3 (0.9 to1.8) | -- |

Percentage of the sample weighted by age, nationality, and QRCS centercentre. Missing values for socio-demographic variables were excluded from the analysis.

Percentage of positive out of the sample weighted by age, nationality, and QRCS centercentre. 95% CIs estimated using binomial distribution.

Includes all other nationalities of craft and manual workers residing in Qatar.

Includes architects, designers, engineers, operation managers, and supervisors among other professions.

Includes carpenters, construction workers, crane operators, electricians, foremen, maintenance/air conditioning/cable technicians, masons, mechanics, painters, pipe-fitters, plumbers, and welders among other professions.

Includes barbers, firefighters, gardeners, farmers, fishermen, and physical fitness trainers among other professions

QRCS, Qatar Red Crescent Society

More than two-thirds of the study participants (69.3%) were below 40 years of age (table 1), with a median age of 35.0 years (IQR: 29.0–43.0 years). Educational attainment for 42.7% of participants was at intermediate or lower levels, and for 44.3%, it was at the high school or vocational training level. The most common nationality groups were Indians (29.4%), Bangladeshis (26.0%) and Nepalese (21.8%), aligning with the broader nationality distribution of the MCMW population in Qatar.19 Among study participants, 53.6% were engaged in technical and construction roles, encompassing occupations such as carpenters, crane operators, electricians, masons, mechanics, painters, plumbers and welders.

Lifetime syphilis infection

Out of the 2528 sera specimens tested, 38 were positive for T. pallidum antibodies (table 1). The estimated prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection among MCMWs was 1.3% (95% CI 0.9% to 1.8%). T. pallidum antibody index values in positive specimens ranged from 1.05 to 21.18 (online supplemental figure S1), with a median of 9.30 (IQR: 2.44–13.39).

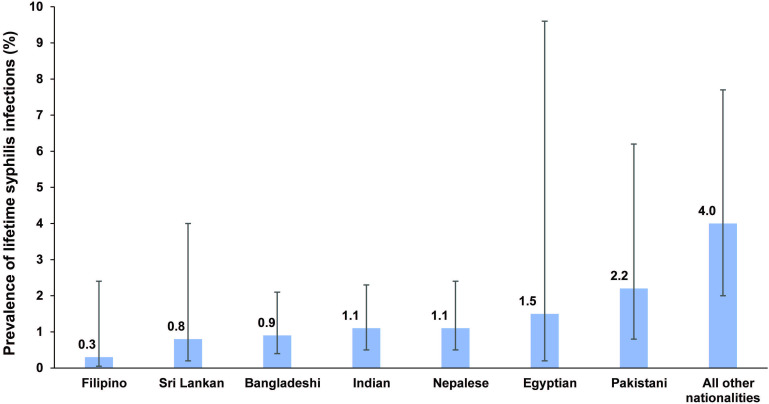

Table 1 outlines the prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection across various population characteristics. The prevalence increased with age, reaching its highest at 6.6% (95% CI 2.7 to 15.3%) for those aged ≥60 years. Variations in prevalence were observed by nationality, ranging from 0.3% (95% CI 0.05 to 2.4%) in Filipinos to 4.0% (95% CI 2.0 to 7.7%) in the group comprising all other nationalities (figure 1). Among different occupations, transport workers exhibited the highest prevalence at 2.3% (95% CI 1.2 to 4.2%).

Figure 1. Prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection by nationality group among the craft and manual worker population in Qatar.

Table 2 reports the associations with lifetime syphilis infection. The AOR exhibited an increase with age, reaching 3.28 (95% CI 1.21 to 8.86) among MCMWs aged 40–49 years and 8.68 (95% CI 2.58 to 29.23) among those aged ≥60 years, in comparison to those ≤29 years of age. The differences by nationality did not attain statistical significance, except for the group encompassing all other nationalities, where the AOR, compared with Filipinos, was 14.1 (95% CI 1.67 to 118.76). While the differences by occupation did not reach statistical significance, the AOR among transport workers, compared with professional, administration and retail workers, was 4.18 (95% CI 0.88 to 19.74), with the difference being of borderline statistical significance. No evidence for differences was found by educational attainment or by QRCS centre (proxy of catchment area/geographic location).

Table 2. Associations with lifetime syphilis infection.

| Characteristics | Bivariable regression analysis | Multivariable regression analysis | |||

| OR* (95% CI*) | P value | F test p value† | AOR* (95% CI*) | P value‡ | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤29 | 1.00 | 0.003 | 1.00 | ||

| 30–39 | 1.08 (0.38 to 3.08) | 0.887 | 1.27 (0.43 to 3.72) | 0.669 | |

| 40–49 | 2.67 (1.01 to 7.09) | 0.048 | 3.28 (1.21 to 8.86) | 0.019 | |

| 50–59 | 1.63 (0.42 to 6.29) | 0.475 | 2.04 (0.56 to 7.45) | 0.283 | |

| 60+ | 8.34 (2.46 to 28.31) | 0.001 | 8.68 (2.58 to 29.23) | <0.001 | |

| Nationality | |||||

| Filipino§ | 1.00 | 0.054 | 1.00 | ||

| Bangladeshi | 2.80 (0.33 to 23.60) | 0.006 | 3.04 (0.35 to 26.14) | 0.311 | |

| Egyptian | 4.41 (0.27 to 72.00) | 0.332 | 4.34 (0.27 to 68.58) | 0.297 | |

| Indian | 3.36 (0.41 to 27.72) | 0.018 | 3.26 (0.38 to 27.57) | 0.279 | |

| Nepalese | 3.30 (0.39 to 27.96) | 0.012 | 3.01 (0.34 to 26.79) | 0.323 | |

| Pakistani | 6.68 (0.70 to 63.24) | 0.016 | 5.01 (0.52 to 48.57) | 0.164 | |

| Sri Lankan | 2.38 (0.18 to 31.16) | 0.342 | 2.12 (0.16 to 28.44) | 0.570 | |

| All other nationalities¶ | 12.44 (1.53 to 100.99) | 0.070 | 14.1 (1.67 to 118.76) | 0.015 | |

| QRCS centre (catchment area within Qatar) | |||||

| Fereej Abdel Aziz (Doha-East) | 1.00 | 0.494 | - | -- | |

| Zekreet (North-West) | 1.88 (0.64 to 5.50) | 0.250 | - | -- | |

| Hemaila (South-West; ‘Industrial Area’) | 0.86 (0.35 to 2.13) | 0.747 | - | - | |

| Mesaimeer (Doha-South) | 1.02 (0.41 to 2.57) | 0.964 | - | - | |

| Educational attainment | - | - | |||

| Primary or lower | 1.00 | 0.227 | - | - | |

| Intermediate | 1.35 (0.51 to 3.54) | 0.541 | - | - | |

| Secondary/high school/vocational | 0.96 (0.39 to 2.34) | 0.921 | - | - | |

| University | 0.29 (0.07 to 1.27) | 0.099 | - | - | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Professional, administration and retail workers** | 1.00 | 0.180 | 1.00 | ||

| Transport workers | 4.84 (1.02 to 23.02) | 0.047 | 4.18 (0.88 to 19.74) | 0.071 | |

| Technical and construction workers†† | 2.53 (0.56 to 11.44) | 0.227 | 2.79 (0.61 to 12.75) | 0.186 | |

| Other workers‡‡ | 3.20 (0.60 to 17.14) | 0.175 | 2.56 (0.44 to 14.83) | 0.295 | |

Estimates weighted by age, nationality, and QRCS centercentre.

Covariates with p value ≤0.2 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis.

Covariates with p value <0.05 in the multivariable analysis were considered to provide statistically significant evidence for an association with antibody positivity.

Filipino was selected as the reference group due to Filipinos having the lowest prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection.

Includes all other nationalities of craft and manual workers residing in Qatar.

Includes architects, designers, engineers, operation managers, and supervisors among other professions.

Includes carpenters, construction workers, crane operators, electricians, foremen, maintenance/air conditioning/cable technicians, masons, mechanics, painters, pipe-fitters, plumbers, and welders among other professions.

Includes security workers, cleaning workers, barbers, firefighters, gardeners, farmers, fishermen, and physical fitness trainers among other professions.

AOR, adjusted OR; QRCS, Qatar Red Crescent Society

Recent syphilis infection

Out of the 38 treponemal-positive specimens, 15 were reactive by RPR, as detailed in table 3, but one specimen lacked sufficient sera for RPR testing. Among the 15 RPR-reactive specimens, only three had titres ≥1:8, indicating recent syphilis infection. The prevalence of recent syphilis infection among MCMWs was estimated, incorporating multiple imputations to adjust for the single treponemal-positive specimen with inadequate sera at 0.09% (95% CI 0.01 to 0.3%).

Table 3. Results of the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing among Treponema pallidum antibody-positive individuals.

| Specimen | T. pallidum antibody index value (treponemal test) | RPR test result (non-treponemal test) | RPR test titres | Interpretation of RPR test result |

| 1 | 1.05 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 2 | 1.12 | Reactive | 1:2 | Lifetime infection |

| 3 | 1.17 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 4 | 1.26 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 5 | 1.31 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 6 | 1.48 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 7 | 1.66 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 8 | 1.92 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 9 | 2.11 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 10 | 2.44 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 11 | 3.06 | Reactive | 1:2 | Lifetime infection |

| 12 | 3.08 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 13 | 3.25 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 14 | 3.9 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 15 | 5.55 | Reactive | 1:4 | Lifetime infection |

| 16 | 6.86 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 17 | 8.25 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 18 | 8.66 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 19 | 9.23 | Reactive | 1:4 | Lifetime infection |

| 20 | 9.36 | Reactive | 1:1 | Lifetime infection |

| 21 | 10.26 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 22 | 12.05 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 23 | 12.17 | Reactive | 1:1 | Lifetime infection |

| 24 | 12.21 | Reactive | 1:2 | Lifetime infection |

| 25 | 12.85 | Reactive | 1:4 | Lifetime infection |

| 26 | 12.91 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 27 | 12.98 | Reactive | 1:2 | Lifetime infection |

| 28 | 13.04 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 29 | 13.39 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 30 | 13.61 | Reactive | 1:4 | Lifetime infection |

| 31 | 13.73 | Reactive | 1:64 | Recent infection |

| 32 | 14.14 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 33 | 14.82 | Non-reactive | -- | Lifetime infection |

| 34 | 14.84 | Reactive | 1:4 | Lifetime infection |

| 35 | 14.94 | Reactive | 1:1 | Lifetime infection |

| 36 | 15.15 | Reactive | 1:8 | Recent infection |

| 37 | 15.63 | Reactive | 1:8 | Recent infection |

| 38 | 21.18 | Specimen did not have sufficient serum to conduct RPR testing | -- | -- |

Among treponemal-positive MCMWs, the estimated proportion with recent infection was 8.1% (95% CI 1.7 to 21.4%). The Spearman correlation coefficient between the T. pallidum antibody index value and the RPR titres was 0.48 (95% CI 0.21 to 0.75; p value: 0.003).

Discussion

The estimated prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection among the MCMW population was 1.3%, while that of recent syphilis infection was estimated at 0.1%. The prevalence of lifetime infection exhibited an increase with age, aligning with expectations for a measure of cumulative exposure. There was evidence of variability in prevalence among different nationality groups and occupations within this diverse MCMW population. Interestingly, there was compelling evidence of an association between the T. pallidum antibody index value and the RPR titres, supported by a Spearman correlation coefficient of approximately 0.5.

The observed prevalence levels are overall consistent, though lower, than the estimated global prevalence of 0.6% for recent syphilis infection,6 28 29 and a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that estimated the prevalence at 0.5% in the general population of the Middle East and North Africa.30 It is important to note methodological variations in defining current or recent syphilis infection across studies.2629,31 In our study, we applied a stringent definition for recent infection, requiring RPR titres ≥1:8.25 26 However, individuals with lower titres, or even non-reactive titres, may still have experienced a recent infection.25 31 Individuals with very recent infections may not test positive in both treponemal and non-treponemal tests,31 potentially leading to missing infections in individuals who have not yet developed antibodies. However, the latter is unlikely to appreciably impact the prevalence estimates. Of note, some individuals with titres ≥1:8 may have also had an earlier non-recent infection that was treated but remained serologically non-responsive, resulting in persistently high RPR titres (serofast state after treatment).31 32

The observed cases of recent syphilis infection indicate recent sexual activity among some members of the MCMW population. Since these migrants are typically single and if married, their wives are not residing with them in Qatar, this may suggest the presence of sexual risk behaviours leading to the acquisition of STIs. This inference may also be supported by the considerable seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 in the same population, as observed in our recent study,15 which is higher than that observed in other populations in Qatar and the Middle East and North Africa region.33,35 However, the specific nature of sexual behaviours and networking within this population remains unexplored. Despite the observed levels of infection, STIs among this population remain unaddressed and inadequately documented, reflecting the limited availability of sexual health and STI programmes.1113 36,38

Limited STI screening among this population could result in a large number of undetected cases, particularly because a large fraction of STI infections are asymptomatic, making infected individuals unlikely to seek testing and treatment in the absence of symptoms.29 30 38 Untreated, these infections may persist for extended periods, increasing the risk of health complications and transmission.29 30 38 The study findings thus emphasise the need to implement programmes addressing STIs in this population and to meet their broader sexual health needs. Furthermore, the results indicate that enhanced efforts are needed for Qatar to achieve the WHO’s target of a 90% reduction in syphilis incidence by 2030.7

This study has limitations. Due to limitations in the availability of sera specimens allocated for this study and other logistical challenges, the testing algorithm used a single treponemal test followed by a non-treponemal test for only treponemal-positive specimens. The study did not implement a reverse sequence syphilis screening algorithm,31 which would involve a second treponemal assay to test treponemal-positive specimens with a non-reactive RPR result or a reactive RPR result but with titres <1:8. Individuals with non-reactive RPR results and those with titres <1:8 may still have had a recent infection that could not be identified using the study’s diagnostic methods. Also, due to limitations in the availability of sera specimens and other logistical challenges, the prozone phenomenon39—which can result in false-negative RPR test results—was not ruled out for treponemal-positive RPR-negative specimens. Overall, the study might have underestimated the prevalence of recent infection.

However, an internal validation of assays at the Laboratory Section of the Medical Commission Department (not shown) indicated 100% agreement between the Mindray CL-900i Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Analyzer and the treponemal Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay test (Architect Syphilis TP; Abbott, Germany). This validation helps reduce the likelihood of false-positive or false-negative test results when using the Mindray CL-900i Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Analyzer.

Some of the migrants originated from countries where non-venereal treponematoses, such as yaws, bejel, and pinta, were endemic.40 Consequently, the prevalence of lifetime syphilis infection may have been overestimated due to the cross-reactivity of syphilis serological diagnostics with antibodies against these infections.40 41 It is also unclear whether SARS-CoV-2 antibody positivity could affect the outcome of RPR testing for the specific assay used in this study.42

Although the initial study design was intended to employ a probability-based sampling approach for the MCMW population, logistical challenges led to the adoption of a systematic sampling method targeting QRCS attendees. To address this shift, probability-based weights were incorporated in an effort to generate an estimate representative of the broader MCMW population. In order to ensure representation of smaller age-nationality strata, all individuals in these strata were approached to participate towards the conclusion of the study, deviating from the initial plan of selecting only every fourth attendee.

Operational challenges presented difficulties in tracking and maintaining consistent logs of the response rate by the nurses in the QRCS centres. Consequently, an exact estimate of the response rate could not be determined, although it was approximated based on the interviewers’ experience to exceed 90%. While there is a possibility that the recruitment scheme might have influenced the generalisability of the study findings, this is deemed less likely given that MCMWs frequent these centres at a high volume, surpassing 5000 patients per day, and these centres serve as the primary healthcare providers specifically for MCMWs in the country.9 MCMWs also use these centres for various services beyond illness, including periodic health certifications, vaccinations, and pretravel SARS-CoV-2 testing.

The study did not have access to the medical records of participants, limiting the ability to obtain information about their prior diagnosis and treatment of syphilis. Only basic sociodemographic variables were collected, excluding sexual behaviour data, in context of the challenging nature of collecting such information in this culturally conservative setting.14 43 44 However, this difficulty underscores the relevance of using STI prevalence as a proxy biomarker to assess population sexual risk behaviour, as suggested previously.4345,47 Information on the length of residency in Qatar was not collected, limiting our ability to determine where the lifetime infection was acquired. This may reduce the relevance of study findings for informing public health policy in Qatar.

In conclusion, the study indicated that over 1% of MCMWs in Qatar show evidence of lifetime syphilis infection, with a lower prevalence of recent infection at approximately 0.1%. These findings highlight an often overlooked disease burden with implications for health and social well-being. Furthermore, they underscore the necessity of implementing programmes to address STIs and meet the broader sexual health needs of this population. Persistent challenges in controlling syphilis persist, compounded by issues such as STI stigma and sociocultural sensitivities. It is critical to develop targeted and culturally sensitive programmes that expand prevention and treatment services. Moreover, STI surveillance and research efforts in this and other population groups in Qatar are essential for monitoring trends, informing public health responses and efficiently allocating resources.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Jeffrey Klausner of the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California for providing valuable insights on syphilis diagnostics and their interpretation. We thank all participants for their willingness to be part of this study. We thank all members of the Craft and Manual Workers Seroprevalence Study Group for their efforts in supporting the collection of the samples of this study. We also thank Dr. Nahla Afifi, Director of Qatar Biobank (QBB), Ms. Tasneem Al-Hamad, Ms. Eiman Al-Khayat and the rest of the QBB team for their unwavering support in retrieving and analysing samples. We also acknowledge Rekha Manoj from the Medical Commission Department for her help in data entry for laboratory results testing. We also acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the Surveillance Team at the Ministry of Public Health for their support in sample collection.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors are grateful for the support from the Biomedical Research Program and the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core, both at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, as well as for support provided by the Ministry of Public Health and Hamad Medical Corporation (Grant number: N/A). LJA, HC and HHA acknowledge the support of the grant ARG01-0522-230273 from the Qatar Research, Development and Innovation Council. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Qatar Research Development and Innovation Council. HHA acknowledges the support of Qatar University internal grant QUCG-CAS-23/24-114. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the article. Statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-083810).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by the Hamad Medical Corporation (MRC 05 133), Qatar University (QU-IRB 1558-EA/21) and Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar (21-00002). The Institutional Review Boards approved this study. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Gheyath K Nasrallah, Email: gheyath.nasrallah@qu.edu.qa.

Hiam Chemaitelly, Email: hsc2001@qatar-med.cornell.edu.

Ahmed Ismail Ahmed Ismail, Email: aismail@MOPH.GOV.QA.

Duaa W Al-Sadeq, Email: da1206066@student.qu.edu.qa.

Fathima H Amanullah, Email: fa1517855@student.qu.edu.qa.

Jawaher A Al-Emadi, Email: jawaher.alemadi@gmail.com.

Hadiya M Khalid, Email: Hk1805901@qu.edu.qa.

Parveen B Nizamuddin, Email: parveen.n@qu.edu.qa.

Ibrahim Al-Shaar, Email: ialshaar@moph.gov.qa.

Ibrahim W Karimeh, Email: ikarime@moph.gov.qa.

Mutaz M Ali, Email: mmohamoud@moph.gov.qa.

Houssein H Ayoub, Email: hayoub@qu.edu.qa.

Sami Abdeen, Email: SAbdeen@hamad.qa.

Ashraf Abdelkarim, Email: AAbdelkarim@hamad.qa.

Faisal Daraan, Email: Daraanfaisal77@gmail.com.

Ahmed Ibrahim Hashim Elhaj Ismail, Email: ahib.hashim@gmail.com.

Nahid Mostafa, Email: dr_nana4@hotmail.com.

Mohamed Sahl, Email: Msahl1@hamad.qa.

Jinan Suliman, Email: JSuliman@hamad.qa.

Elias Tayar, Email: ETayar@hamad.qa.

Hasan Ali Kasem, Email: h.kasem@qrcs.org.qa.

Meynard J A Agsalog, Email: Meynard.Agsalog@qrcs.org.qa.

Bassam K Akkarathodiyil, Email: bassam.ka@qrcs.org.qa.

Ayat A Alkhalaf, Email: ayat.alkhalaf@qrcs.org.qa.

Mohamed Morhaf M H Alakshar, Email: mohamed.alakshar@qrcs.org.qa.

Abdulsalam Ali A H Al-Qahtani, Email: aalqahtani@qrcs.org.qa.

Monther H A Al-Shedifat, Email: monther.hassan@qrcs.org.qa.

Anas Ansari, Email: anas.ansari@qrcs.org.qa.

Ahmad Ali Ataalla, Email: Ahmad.Atalla@qrcs.org.qa.

Sandeep Chougule, Email: sandeep.chougule@qrcs.org.qa.

Abhilash K K V Gopinathan, Email: abhilash.gopinathan@qrcs.org.qa.

Feroz J Poolakundan, Email: feroz.poolakundan@qrcs.org.qa.

Sanjay U Ranbhise, Email: sanjay.ranbhise@qrcs.org.qa.

Saed M A Saefan, Email: Saed.Saefan@qrcs.org.qa.

Mohamed M Thaivalappil, Email: m.thaivalappil@qrcs.org.qa.

Abubacker S Thoyalil, Email: abubacker.thoyalil@qrcs.org.qa.

Inayath M Umar, Email: INAYATH.UMAR@qrcs.org.qa.

Einas Al Kuwari, Email: ealkuwari@hamad.qa.

Peter Coyle, Email: pcoyle@hamad.qa.

Andrew Jeremijenko, Email: andrewjenko@hotmail.com.

Anvar Hassan Kaleeckal, Email: AKaleeckal@hamad.qa.

Hanan F Abdul Rahim, Email: hanan.arahim@qu.edu.qa.

Hadi M Yassine, Email: HYASSINE@QU.EDU.QA.

Asmaa A Al Thani, Email: aaja@qu.edu.qa.

Odette Chaghoury, Email: OChagoury@hamad.qa.

Mohamed Ghaith Al-Kuwari, Email: malkuwari@phcc.gov.qa.

Elmoubasher Farag, Email: eabdfarag@MOPH.GOV.QA.

Roberto Bertollini, Email: rbertollini@MOPH.GOV.QA.

Hamad Eid Al Romaihi, Email: halromaihi@moph.gov.qa.

Abdullatif Al Khal, Email: aalkhal@hamad.qa.

Mohammed H Al-Thani, Email: malthani@MOPH.GOV.QA.

Laith J Abu-Raddad, Email: lja2002@qatar-med.cornell.edu.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Hook EW. Syphilis. Lancet. 2017;389:1550–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Syphilis: Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/syphilis Available.

- 3.Ho EL, Lukehart SA. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4584–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI57173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korenromp EL, Rowley J, Alonso M, et al. Global burden of maternal and congenital syphilis and associated adverse birth outcomes-Estimates for 2016 and progress since 2012. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper JM, Sánchez PJ. Congenital syphilis. Semin Perinatol. 2018;42:176–84. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:548–562P. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022-2030. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053779 Available.

- 8.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Characterizing the Qatar advanced-phase SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6233. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85428-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Thani MH, Farag E, Bertollini R, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Is at Herd Immunity in the Majority Segment of the Population of Qatar. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab221. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AlNuaimi AA, Chemaitelly H, Semaan S, et al. All-cause and COVID-19 mortality in Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8:e012291. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egli-Gany D, Aftab W, Hawkes S, et al. The social and structural determinants of sexual and reproductive health and rights in migrants and refugees: a systematic review of reviews. East Mediterr Health J. 2021;27:1203–13. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahme SA, Fakih I, Ghassani A, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among pregnant Syrian refugee women seeking antenatal care in Lebanon. J Travel Med. 2024;31:taae058. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taae058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-Raddad LJ, Ghanem KG, Feizzadeh A, et al. HIV and other sexually transmitted infection research in the Middle East and North Africa: promising progress? Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89 Suppl 3:iii1–4. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for strategic action. Middle East and North Africa HIV/AIDS epidemiology synthesis project. Washington, DC: World Bank/UNAIDS/WHO Publication; 2010. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-0-8213-8137-3 Available. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasrallah GK, Dargham SR, Al-Sadeq DW, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 among the migrant workers in Qatar. Virol J. 2023;20:188. doi: 10.1186/s12985-023-02157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younes N, Yassine HM, Nizamuddin PB, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus (HEV) among male craft and manual workers in Qatar (2020-2021) Heliyon. 2023;9:e21404. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasrallah GK, Chemaitelly H, Ismail AIA, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses among migrant workers in Qatar. Sci Rep. 2024;14:11275. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-61725-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeremijenko A, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Herd Immunity against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in 10 Communities, Qatar. Emerg Infect Dis . 2021;27:1343–52. doi: 10.3201/eid2705.204365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Interior-State of Qatar Population distribution by sex, age, and nationality: results of Kashef database. 2020.

- 20.Planning and Statistics Authority-State of Qatar Labor force sample survey. https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/Social/LaborForce/2017/statistical_analysis_labor_force_2017_En.pdf Available.

- 21.World Health Organization Population-based age-stratified seroepidemiological investigation protocol for COVID-19 virus infection. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331656 Available.

- 22.Mindray Mindray CL-900i chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer. Cat No Anti-TP112, Shenzen, China. 2015.

- 23.Xia CS, Yue ZH, Wang H. Evaluation of three automated Treponema pallidum antibody assays for syphilis screening. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:887–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortress Diagnostics The Fortress Diagnostics Rapid Plasma Reagin. https://www.fortressdiagnostics.com/products/syphilis-tests/rpr Available.

- 25.Gottlieb SL, Pope V, Sternberg MR, et al. Prevalence of syphilis seroreactivity in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2001-2004. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:507–11. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klausner PJ. Syphilis diagnsotics and their interpretation Personal communication. 2023.

- 27.Nasrallah GK, Al-Buainain R, Younes N, et al. Screening and diagnostic testing protocols for HIV and Syphilis infections in health care setting in Qatar: Evaluation and recommendations. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0278079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization Global and regional STI estimates. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/global-and-regional-sti-estimates Available.

- 29.Smolak A, Rowley J, Nagelkerke N, et al. Trends and Predictors of Syphilis Prevalence in the General Population: Global Pooled Analyses of 1103 Prevalence Measures Including 136 Million Syphilis Tests. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1184–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Jamal M, Annan B, Al Tawil A, et al. Syphilis infection prevalence in the Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClin Med. 2024;75:102746. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soreng K, Levy R, Fakile Y. Serologic Testing for Syphilis: Benefits and Challenges of a Reverse Algorithm. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2014;36:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghanem KG, Hook EW. The Terms “Serofast” and “Serological Nonresponse” in the Modern Syphilis Era. Sexual Trans Dis. 2021;48:451–2. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harfouche M, Alareeki A, Osman AMM, et al. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 in the Middle East and North Africa: Systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e28603. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dargham SR, Nasrallah GK, Al-Absi ES, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Seroprevalence Among Different National Populations of Middle East and North African Men. Sexual Trans Dis. 2018;45:482–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasrallah G, Dargham S, Harfouche M, et al. Seroprevalence of Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Indian and Filipino migrant populations in Qatar: a cross-sectional survey. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:609–15. doi: 10.26719/2020.26.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolak A, Chemaitelly H, Hermez JG, et al. Epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis in the Middle East and north Africa: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1197–225. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNAIDS Laws and Policies Analytics. https://lawsandpolicies.unaids.org Available.

- 38.Harfouche M, Gherbi WS, Alareeki A, et al. Epidemiology of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. EBioMedicine. 2024;106:105250. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sidana R, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2011;32:47–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.81256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitjà O, Šmajs D, Bassat Q. Advances in the diagnosis of endemic treponematoses: yaws, bejel, and pinta. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smajs D, Norris SJ, Weinstock GM. Genetic diversity in Treponema pallidum: implications for pathogenesis, evolution and molecular diagnostics of syphilis and yaws. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong-Hang K, MacLennan A, Love S, et al. Evaluation of False Positive RPR Results and the Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in a Clinical Population with a High Rate of Syphilis Utilizing the Traditional Screening Algorithm. Am J Clin Pathol. 2022;158:S17–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqac126.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu-Raddad LJ, Schiffer JT, Ashley R, et al. HSV-2 serology can be predictive of HIV epidemic potential and hidden sexual risk behavior in the Middle East and North Africa. Epidemics. 2010;2:173–82. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abu-Raddad LJ, Hilmi N, Mumtaz G, et al. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Middle East and North Africa. AIDS. 2010;24 Suppl 2:S5–23. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386729.56683.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omori R, Abu-Raddad LJ. Sexual network drivers of HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2 transmission. AIDS. 2017;31:1721–32. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kouyoumjian SP, Heijnen M, Chaabna K, et al. Global population-level association between herpes simplex virus 2 prevalence and HIV prevalence. AIDS. 2018;32:1343–52. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chemaitelly H, Weiss HA, Abu-Raddad LJ. HSV-2 as a biomarker of HIV epidemic potential in female sex workers: meta-analysis, global epidemiology and implications. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19293. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]