Abstract

Background

Numerous studies have found that depression is prevalent among correctional officers (COs), which may be related to the work-family conflict (WFC) faced by this cohort. Role conflict theory posits that WFC emerges from the incompatibility between the demands of work and family roles, which induces stress and, in turn, results in emotional problems. Thus, this study seeks to investigate the association between WFC and depression, along with examining the mediating role of stress. Further network analysis is applied to identify the core and bridge symptoms within the network of WFC, stress, and depression, providing a basis for targeted interventions.

Objective

This study aims to investigate the relationship between work-family conflict (WFC) and depressive symptoms among a larger sample of Chinese correctional officers (COs), exploring the potential mechanisms of stress in this population through network analysis.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 472 Chinese COs was conducted from October 2021 to January 2022. WFC, stress, and depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Work-Family Conflict Scale (WFCS) and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). Subsequently, correlation and regression analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0, while mediation analysis was performed using Model 4 in PROCESS. By using the EBICglasso model, network analyses were utilized to estimate the network structure of WFC, stress and depression. Visualization and centrality measures were performed using the R package.

Results

The results showed that (1) there was a significant positive correlation between WFC and stress and depression, as well as between stress and depression, (2) WFC and stress had a significant positive predictive effect on depression, (3) stress mediated the relationship between WFC and depression, with a total mediating effect of 0.262 (BootSE = 0.031, BCI 95% = 0.278, 0.325), which accounted for 81.62% of the total effect, and (4) in the WFC, stress, and depression network model, strain-based work interference with family (SWF, (betweenness = 2.24, closeness = -0.19, strength = 1.40), difficult to relax (DR, betweenness = 1.20, closeness = 1.85, strength = 1.06), and had nothing (HN, betweenness = -0.43, closeness = 0.62, strength = 0.73) were the core symptoms, and SWF, IT, and DH were the bridge symptoms, and (5) first-line COs had significantly higher levels of WFC, stress, and depression than non-first-line correctional officers.

Conclusion

Our findings elucidate the interrelationships between WFC, stress, and depression among COs. The study also enhances the understanding of the factors influencing WFC in this population and provides valuable guidance for the development of future interventions, offering practical clinical significance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20815-z.

Keywords: Correctional officers, Work-family conflict, Stress, Depression, Mediation analysis, Network analysis

Introduction

Correctional officers (COs) experience more work-family conflict (WFC) and elevated rates of mental and physical ill-health as compared with other general industry and public safety occupations [1]. According to role conflict theory, WFC arises when the demands from the work and family domains are incompatible, leading individuals to experience stress and emotional strain due to the difficulty in fulfilling both roles simultaneously [2]. It is defined as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are incompatible with each other in some ways” [3]. The heavy workload and insufficient vacation or rest time make it difficult for COs to balance work and family life, leading to severe WFC [4].

COs report a high incidence of depression, which not only affects their professional development and well-being but also impacts the correctional and rehabilitative functions of the incarcerated individuals. A study of male COs in Chinese prisons revealed that approximately 61.4% of Chinese male COs exhibited depressive symptoms, with a prevalence of 63.5% among frontline COs and 57.3% among non-frontline COs [5]. Results from a national online survey of public safety personnel in Canada showed that as many as one-third of public safety personnel suffer from one or more psychiatric disorders. Among COs, the self-reported prevalence of mental illness symptoms was notably higher, encompassing post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder, and depression [6].

The Conservation of Resources (COR) model provides another important framework for understanding WFC and its link to mental health. According to the COR model, individuals strive to acquire, protect, and maintain resources (such as time, energy, and emotional capacity), and stress arises when these resources are threatened or depleted [7]. For COs, WFC can be viewed as a process in which the demands from the work domain deplete the resources available for the family domain, leading to heightened stress and emotional exhaustion. This depletion of resources not only contributes but may also exacerbate depressive symptoms [8].

Research has shown that chronic stressors can lead to prolonged activation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, exerting negative effects on the body [9]. Prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids, particularly cortisol, can result in structural and functional alterations in the specific regions of the brain. For instance, the hippocampus is sensitive to elevated cortisol levels, which can lead to atrophy, reduced volume, and neuronal death, all of which are associated with depression [10–12]. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), involved in decision-making and impulse control, is functionally linked to the ANS, and its heightened reactivity to stressors is a significant risk factor for depression [13, 14].

Meanwhile, research has shown that WFC and depressive symptoms are significantly correlated [15, 16]. Research on Chinese healthcare workers have shown that both WFC and family work conflict (FWC) are positively associated with depressive symptoms [17]. WFC is often recognized as a chronic stressor, and chronic stress is a critical factor in the development of psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression [18]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the occurrence of WFC or FWC is significantly and positively correlated with psychosocial work stress [19]. Therefore, the mediating role of stress between WFC and depression is constant with the role conflict theory and the COR model, as both frameworks emphasize the stress arising from competing demands and the depletion of personal resources.

In summary, there appears to be an association between WFC and the higher prevalence of emotional symptoms among COs, and stress may play a crucial role. However, previous studies often have small sample sizes, and research on the underlying mechanisms between WFC and depressive symptoms remains limited.

Over the past decade, the new approach of network analysis to understanding the nature of psychopathology and treatment has received significant attention and has been frequently applied [20]. Network analysis has provided new insights into the functional role and importance of specific symptoms in maintaining illness [21, 22]. Network analysis, an advanced statistical method, reveals complex relationships among psychiatric symptoms and visualizes their interactions [23]. It helps identify core and bridging symptoms, with bridging symptoms connecting different symptom clusters and aiding in understanding information transmission pathways. Targeting these bridging symptoms in interventions can be beneficial for managing multiple psychiatric disorders simultaneously [24].

Thus, the focus of this study is on a larger sample of Chinese COs to investigate the relationship between WFC and depressive symptoms and the potential mechanisms of stress in this population by using network analysis. By thoroughly examining the impact of various forms of work-family conflict (WFC) on different dimensions of depression among COs, more targeted interventions can be identified to prevent further deterioration of mental health issues within this group. Additionally, the heterogeneity of WFC and its effects may result in significant variability in the prevalence of depression among individuals. Therefore, network analysis was employed to investigate the network structure between WFC and depression and to identify connections between symptoms, with the aim of developing effective treatments and interventions.

Based on this, we proposed the following hypotheses: (1) WFC is positively correlated with stress and depression; (2) stress plays a mediating role between WFC and depression, i.e., increased WFC may be associated with higher levels of stress, which leads to a further increase in depression. We hypothesize the presence of an interactive network of symptoms related to CO’s stress, depression, and work-family conflict (WFC). The network-based approach will help identify central nodes within the symptom network and will provide a foundation for developing interventions that could support COs.

Methods

Subjects

Between October 2021 and January 2022, we carried out a cross-sectional study focusing on correctional officers from various provinces in China. An anonymous online questionnaire was created using Questionnaire Star (https://www.wjx.cn), a popular platform for online surveys in China. To initiate participant recruitment, we selected 10 correctional officers who had attended an annual training program organized by the prison administration department for professional development and knowledge sharing. These initial participants were chosen based on two criteria: (1) their willingness to participate in the survey and recommend it to others, and (2) their representation from different provinces to ensure diverse geographical coverage. The link to the questionnaire was then disseminated through widely used social media platforms, particularly WeChat, where the original participants shared it with their friends and members of WeChat groups. The questionnaire’s introductory section provided a brief overview of the study, ensuring participants understood the measures taken to maintain anonymity and confidentiality. Before starting the survey, participants had to indicate their informed consent by selecting “Agree” and were informed they could withdraw at any time by selecting “Disagree.” This research received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

Sociodemographic data

The sociodemographic data were collected using a self-designed questionnaire, which included age, gender, education, years worked as a correctional officer, marital status and location of practice.

Clinical data

Work-Family Conflict Scale (WFCS)

The Chinese version of Work-Family Conflict Scale (WFCS) was used to assess the WFC experienced by the participants [25]. The WFCS comprises 18 items, categorized into two subscales: work interference with family and family interference with work. Each subscale includes three forms of work-family conflict: (a) time-based conflict, (b) stress-based conflict, and (c) behavior-based conflict. Therefore, the work-family conflict results encompass six dimensions, with three items for each dimension. All items are assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always), resulting in a total score between 18 and 90, with scores for each dimension ranging from 3 to 15. A higher cumulative score on this scale reflects increased WFC. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.917.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)

We assessed symptoms of stress and depression using the Chinese version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) [26]. The DASS is a self-report questionnaire comprising 21 items and three subscales (depression, anxiety, and stress), with seven items in each subscale. The scale evaluates symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress experienced over the past week. Participants rated each item using a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = very much so). The subscale score is calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items, ranging from 0 to 21. The summary score is also computed by summing all the item scores, ranging from 0 to 63, with higher scores reflecting more severe symptoms. As the DASS-21 is a short form version of the DASS(42 items), the final score of each scale were multiplied by two, so that they can be compared with the normal DASS scores [27]. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the DASS was 0.952.

Statistical analyses

To ensure the quality of our surveys, all completed questionnaires were screened for inappropriate responses and lack of variation in responses to open-ended questions. Those responses that did not correctly answer validity entries, had a scale completion time of < 1 min, or had too much option homogeneity, were excluded. Descriptive analysis of demographic information and statistical analysis of scale scores were performed using SPSS 26.0. Pearson correlation analysis was used to determine the relationship between WFC, stress and depression. Stratified regression was used to determine the impact of controlling variables, WFC, and stress on the risk of depression. Mediated effects were analyzed using Model 4 from Hayes’s PROCESS plug-in [28], with significance tested through the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method. Statistical significance was considered if the 95% confidence interval did not contain a value of 0.

Network analysis

We utilized the EBICglasso model to estimate the network of Work-Family Conflict (WFC), stress, and depression symptoms, a method commonly applied in psychological networks [29]. The estimation and visualization of the network were conducted using the R packages “bootnet” and “qgraph.” Within the network, each symptom was depicted as a “node,” and the distinct association between symptoms, while accounting for other nodes in the network, was represented as an “edge.” Stronger associations were indicated by thicker edges, with red edges indicating positive associations and blue edges denoting negative associations. We used the “goldbricker” function of R packages “networktools” to reduce topological overlap. We employed three commonly used centrality measures, i.e., strength, closeness, betweenness, and bridge strength to quantify the central and bridge symptoms within the WFC-stress-depression network [30]. We used the case-dropping procedure to estimate the accuracy of central and bridge symptoms in the network, by using the bootnet R package (version 1.5) with 1000 iterations [29]. The centrality stability coefficient (CS-coefficient) indicated the stability of the network. A CS-coefficient lower than 0.25 signified high instability, while a value equal to or exceeding 0.5 is considered optimal.

Results

The demographic characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants is 37.65 years with a standard deviation of 8.15. The gender distribution is 31.9% female (n = 150) and 68.1% male (n = 322). Regarding education levels, 13.6% (n = 64) have junior college education or below, 80.5% (n = 380) are undergraduates, and 5.9% (n = 28) have postgraduate education or above. For job roles, 68.6% (n = 324) are frontline staff, while 31.4% (n = 148) are office clerks.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (n = 472)

| Variable | M (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.65 (8.15) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 150 (31.9%) |

| Male | 322 (68.1%) |

| Level of education | |

| Junior college and below | 64(13.6%) |

| Undergraduate | 380(80.5%) |

| Postgraduate and above | 28(5.9%) |

| Work experience(years) | 13.58 (9.58) |

| Marriage | |

| Married | 379 (80.3%) |

| Unmarried | 71 (15.0%) |

| Divorced | 22 (4.7%) |

| Location of practice | |

| Platoon and the front line | 324 (68.6%) |

| Department and secretary staff | 148 (31.4%) |

The mean score of each dimension in the WFCS and each item of stress and depression are shown in Table S1.

Correlation analysis

In order to explore the relationship between factors related to depression, we conducted a correlation analysis (Table 2). The results indicate that there is a significant positive correlation between work-family conflict (WFC) and both stress (r = 0.47, p < 0.001) and depression (r = 0.44, p < 0.001). Additionally, stress is significantly and positively correlated with depression (r = 0.78, p < 0.001). These correlations satisfy the criteria for conducting subsequent regression analyses.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

| M ± SD | WFC | Stress | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFC | 60.45 ± 12.90 | 1 | ||

| Stress | 14.99 ± 9.30 | 0.47*** | 1 | |

| Depression | 13.69 ± 9.60 | 0.44*** | 0.78*** | 1 |

Results in bold are statistically significant. ***P < 0.001

WFC work-family conflict, M mean, SD standard deviation

Regression analysis

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis further demonstrated the impact of control variables, WFC, and stress on the risk of depression in the participants (Table S2). In Model 1, being divorced (β = 9.831, p < 0.001) and location of practice (β = −3.662, p < 0.001) are significant predictors of depression, while being married (β = 2.775, p < 0.05) also has a statistically significant impact. However, as additional independent variables (WFC and stress) are included in Model 2, the effects of occupation and divorce on the risk of depression no longer hold statistical significance. In contrast, both WFC (β = 0.054, p < 0.05) and stress (β = 0.804, p < 0.001) continue to exhibit significant effects on the risk of depression.

The R² value increases from 0.069 in Model 1 to 0.687 in Model 2, indicating a substantial improvement in the explanatory power of the model as stress and WFC are added. The ΔR² represents the adjusted R², reflecting the additional variance explained after accounting for WFC and stress. Specifically, the ΔR² shows a significant increase of 0.682, suggesting that the inclusion of these variables considerably enhances the model’s ability to explain the variation in depression risk.

Given that gender was found not to be a significant factor in the initial analysis, subsequent analyses were performed without controlling for gender.

The results of the multiple linear regression showed that both WFC and stress can significantly and positively predict depression (β = 0.059, t = 2.715, p < 0.01; β = 0.813, t = 26.982, p < 0.001). Additionally, WFC can significantly and positively predict stress (β = 0.323, t = 10.862, p < 0.001) (Table S3). These results support the possibility of conducting a mediated effects analysis, suggesting that stress may play a mediating role between work-family conflict and depression.

Mediated analysis

The results of the mediation analysis (Table 3, Figure S1) show that stress partially mediates the relationship between work-family conflict (WFC) and depression. The total effect of WFC on depression is 0.321 (BootSE = 0.031, BCI 95% = 0.260, 0.382). The direct effect of WFC on depression is 0.059 (BootSE = 0.022, BCI 95% = 0.007, 0.163), accounting for 18.38% of the total effect. The total indirect effect, with stress as the mediator, is 0.262 (BootSE = 0.031, BCI 95% = 0.278, 0.325), accounting for 81.62% of the total effect.

Table 3.

Mediating effect analysis of the mediating model

| Path models | β | BootSE | BCI 95% | Mediated, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect: WFC-Depression | 0.321 | 0.031 | 0.260,0.382 | |

| Direct effect: WFC-Depression | 0.059 | 0.022 | 0.007,0.163 | 18.38 |

| Total indirect effect: WFC-Stress-Depression | 0.262 | 0.031 | 0.278,0.325 | 81.62 |

In addition to this, we compared WFC, stress, and depression levels between first-line and non-first-line COs and found that first-line COs had significantly higher levels of WFC, stress, and depression than non-first-line Cos (Table S4).

Network analysis

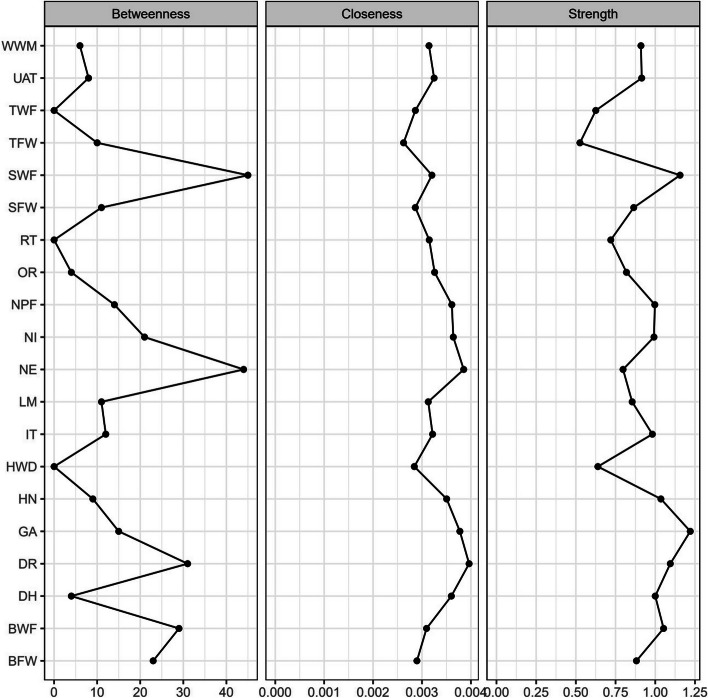

Key connections between variables

Three clusters of symptoms WFC, stress and depression symptoms were found to be bridged by several symptoms (Fig. 1). The stress symptoms that are closest to WFC symptoms and depression symptoms are as follows: intolerant behavior is related to strain-based family interference with work (partial correlation coefficient: 0.07) and is also linked to feelings of downheartedness (partial correlation coefficient: 0.15)(Table S5).

Fig. 1.

The WFC- stress-depression network. Note: Labels for work-family conflict: TWF = Time based work interference with family; SWF = Strain based work interference with family; BWF = Behavior based work interference with family; TFW = Time based family interference with work; SFW = Strain based family interference with work; BFW = Behavior based family interference with work. Labels for stress: HWD = Hard to wind down; OR = Over-react; NE = Nervous energy; GA = Getting agitated; DR = Difficult to relax; IT = Intolerant; RT = Rather touchy. Labels for depression: NPF = No positive feeling; NI = No initiatives; HN = Had nothing; DH = Down-hearted; UAT = Unable about things; WWM = Wasn’t worth much; LM = Life is meaningless

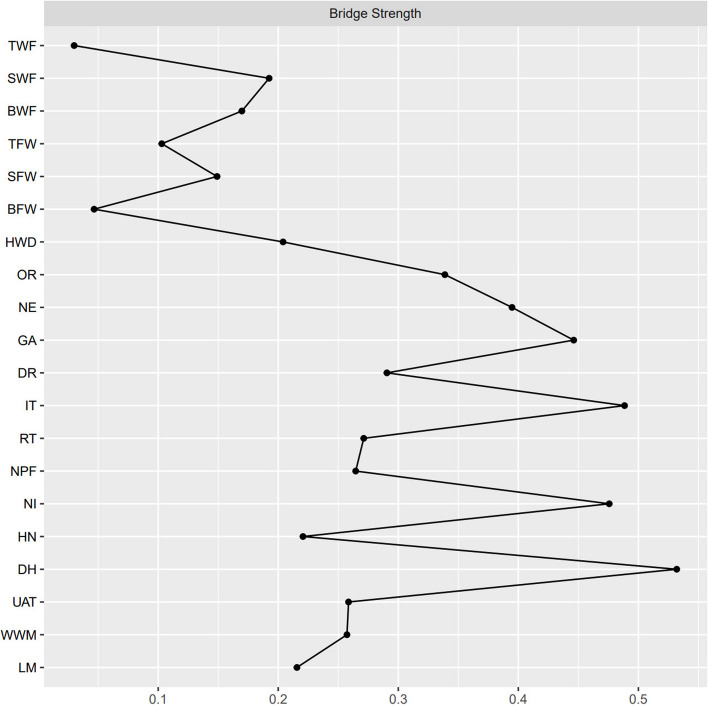

Centrality measures

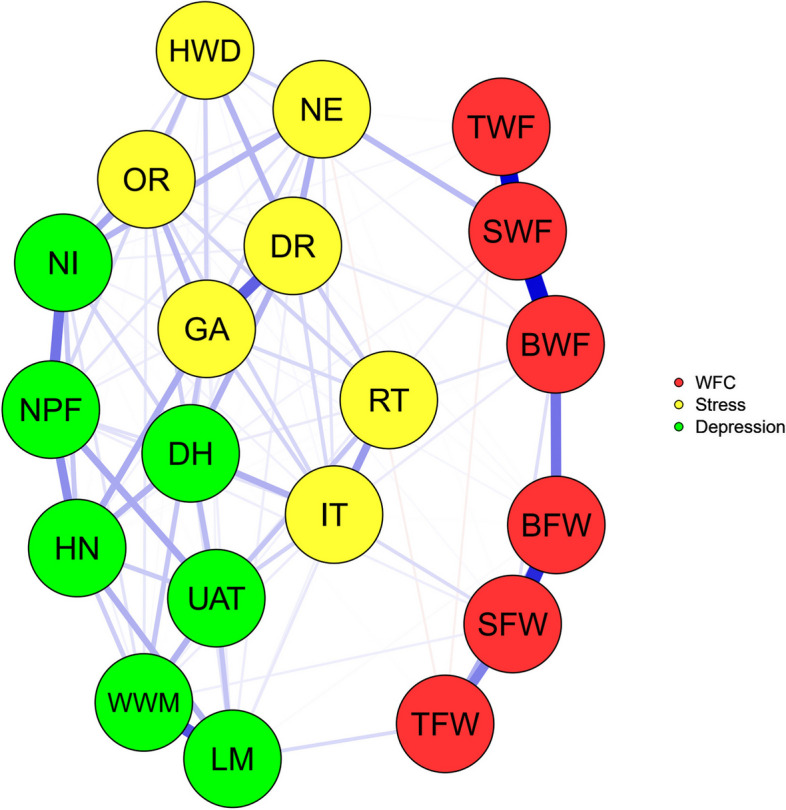

According to the Fig. 2, the WFC symptoms with the highest centrality were strain-based work interference with family (betweenness = 2.24, closeness=−0.19, and strength = 1.40) and behavior-based work interference with family (betweenness = 1.05, closeness=−0.48, and strength = 0.82), the stress symptoms with the highest centrality were difficult to relax (betweenness = 1.20, closeness = 1.85, and strength = 1.06) and getting agitated (betweenness = 0.01, closeness = 1.34, and strength = 1.75), whereas the depression symptoms with the highest centrality were had nothing (betweenness=−0.43, closeness = 0.62, and strength = 0.73) and down-hearted (betweenness=−0.81, closeness = 0.87, and strength = 0.53). According to the bridge strength, strain-based work interference with family, intolerant and down-hearted were the three most prominent bridge symptoms in this model (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Centrality indices of the WFC- stress-depression network. Note: Values shown on the x-axis are standardized z-scores

Fig. 3.

Bridge centrality indices of the WFC- stress-depression network. Note: Labels for work-family conflict: TWF = Time based work interference with family; SWF = Strain based work interference with family; BWF = Behavior based work interference with family; TFW = Time based family interference with work; SFW = Strain based family interference with work; BFW = Behavior based family interference with work. Labels for stress: HWD = Hard to wind down; OR = Over-react; NE = Nervous energy; GA = Getting agitated; DR = Difficult to relax; IT = Intolerant; RT = Rather touchy. Labels for depression: NPF = No positive feeling; NI = No initiatives; HN = Had nothing; DH = Down-hearted; UAT = Unable about things; WWM = Wasn’t worth much; LM = Life is meaningless

Stability analyses

The stability analyses showed that the network models were stable (Figure S2 and Figure S3). Specifically, the edge weight stability analyses suggested that the tie strengths were reliably estimated. The node-dropping stability analyses showed that node centrality rankings remained consistent even after removing up to 50% of the nodes. Among the centrality measures, strength centrality was the most stable.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to discuss in depth how WFC contributes to depressive symptoms among Chinese COs. The findings showed that WFC had a significant positive correlation with stress and depression, and stress was significantly positively correlated with depression. The results of hierarchical regression indicated that WFC and depression played a significant role in predicting depression levels, and frontline COs experienced a higher risk of depression compared to non-frontline COs. Moreover, mediation analysis indicated that stress mediated the relationship between WFC and depression. Further network analysis identified strain- based work interference with family (SWF), difficult to relax (DR) and had nothing (HN) as core symptoms and SWF, Intolerant (IT) and Down-hearted (DH) as bridge symptoms.

WFC, stress, and depression correlations

The findings suggested that WFC, stress, and depression were positively correlated and stress played an indirect mediating effect in WFC leading to depression, i.e., WFC indirectly led to depression by increasing stress. Studies of 441 COs in a southern continent of the United States [31], 322 COs in Guangzhou, China [32], 897 Australian workers working at home [33], and 1010 Filipino nurses [34] have all reported significant correlations between WFC and job stress. Prospective cohort study of 3,121 U.S. internists found that WFC was associated with increased levels of depression among internists [35]. According to Role Conflict Theory, COs face irreconcilable conflicts between work and family roles, leading to high levels of stress. Work demands often force them to dedicate more time and energy to their jobs, which results in reduced involvement and emotional engagement in their family roles. This inter-role conflict is a significant source of increased stress. Such inter-role stress can result in negative outcomes, including dissatisfaction with work and life, depression, and anxiety [36]. According to the COR model, the work and family domains are viewed as repositories of resources, with potential or actual threats, losses, or gains in one domain affecting the underlying state of the other [37]. Together, they suggest that WFC is not only a problem of role conflict but also an issue of resource management and allocation. Effective resource conservation strategies and stress management measures can alleviate the role conflict faced by COs, thereby reducing the negative impact of WFC on mental health. Therefore, effective management of stress among COS may help mitigate the impact of WFC, thereby reducing the incidence of depression.

Network analysis findings

To further explore the relationships among WFC, stress, and depression, and to identify potential intervention targets, network analysis was applied in this study. The network analysis revealed that SWF, DR, and HN are the core symptoms, while SWF, IT, and DH are the potential bridge symptoms connecting the three components of WFC, stress, and depression.

Core symptoms

SWF, as a core symptom and bridge symptom of the WFC, stress, and depression psychopathological network model, has been defined as the stress experienced in the work role interfering with family role participation. Specifically, SWF can manifest as being too exhausted after work to engage in family activities or fulfill family responsibilities, or as the inability to enjoy preferred activities upon returning home [3, 25]. According to Role Conflict Theory, the incompatibility between work and family roles is the fundamental cause of work-family conflict (WFC). For correctional officers (COs), the high demands of their work make it difficult to balance family responsibilities, which is reflected in SWF, or work interference with family life. SWF, as a core symptom, captures this role conflict. In our study, SWF emerged as the most prominent symptom. Based on the Conservation of Resources (COR) model, COs’ resources (such as time, energy, and emotional capacity) are depleted in the work domain, leaving little for their family role. This depletion leads to increased stress, as work encroaches on family life and essential resources are drained. A study of 441 COs also found that SWF was significantly associated with job stress and job satisfaction, and that COs who experienced greater SWF were more stressed at work and significantly less satisfied with their jobs [31], which may be more likely to cause depression. A study of 577 Chinese immigrants in New Zealand found that SWF had a greater impact on their well-being than TWF [38]. Taken together, this suggests that it is essential to intervene specifically for SWF among COs.

In our study, DR (difficult to relax) and HN (had nothing or feelings of emptiness) emerged as two additional core symptoms, representing the concentrated expressions of stress and depression. DR reflects the inability of correctional officers to break free from work pressure while being in a state of tension and exhaustion. HN represents the complete loss of interest and motivation in life for correctional officers. According to the Conservation of Resources (COR) model, when correctional officers’ resources are depleted in the work domain and cannot be effectively replenished in the family domain, their emotional resources become exhausted, leading to difficulty relaxing (DR). As stress intensifies and emotional resources are fully depleted, feelings of emptiness and meaninglessness (HN) arise, making it difficult for individuals to restore their emotional well-being.

Bridge symptoms

Another interesting observation is that SWF, IT, and DH serve as potential bridge symptoms connecting the three components of WFC, stress, and depression. SWF (strain-based work interference with family), as both a core and bridge symptom, directly reflects WFC while also serving as a key node in the transition from stress to depression. IT (intolerant) reflects the reduced tolerance to stress after work resources are depleted. IT bridges SWF and DR, indicating that as work-family conflict intensifies and becomes intolerable, correctional officers are unable to relax even when away from work, leading to the core symptom DR. DH (down-hearted) reflects how prolonged stress can evolve into more severe depressive symptoms. DH bridges DR and HN, indicating that under the influence of stress, correctional officers experience persistent low mood, which ultimately leads to the core symptom of HN (had nothing).

Frontline vs. Non-frontline COs

It is worth noting that the results of the stratified regression analyses found a significant effect of job content on depression, with frontline COs significantly more likely to be depressed compared to non-frontline COs. Participants working in brigade and frontline jobs had significantly higher levels of WFC, stress, and depression than those working in section and clerical jobs. Further mediation analysis suggests that stress acts as a stronger mediator among frontline workers, with frontline correctional officers experiencing greater impacts from WFC. Frontline COs are required to maintain security, order and safety in any custodial institution or prison, work night shifts and have direct contact with offenders for almost all of their working hours, whereas non-frontline COs have less direct contact with offenders, work fewer night shifts and are more flexible in the performance of their duties. Frontline COs often face more stress in the workplace than non-frontline COs [39, 40]. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to stress management and WFC among frontline COs when conducting psychological interventions. These findings can provide an important basis for developing psychological intervention strategies for different positions.

Limitations and future research

The results of this study should be considered within the following limitations. First, the study was cross-sectional and could not establish causality. We made certain assumptions about the temporal order of variables in the conceptual model. Despite what the data suggest, a longitudinal design is needed to establish the temporal order of mediating effects. Second, the study utilized a “snowball” sampling method, which, while helpful in reaching a specific population, may have introduced a self-selection bias because participants volunteered. Third, the study may have had a healthy worker effect [41], meaning that healthy people were more likely to continue working in orthodontics, and we may have missed people who were unable to work due to their medical conditions, which may have had an impact on the results. Fourth, work-family conflict, stress, and anxiety were measured by self-reported questionnaires, which lack objective indicators and may lead to biased information. Finally, we conducted network analyses in frontline and non-frontline COs, but due to the small sample sizes of these two groups, the results were less stable. Given these limitations, future research should conduct a multicenter cohort study with a random sample of all COs and should develop an intervention based on the bridge symptoms identified in this article and observe the levels of work-family conflict, stress, and depression in COs after the intervention.

Conclusion

This study showed that WFC was significantly and positively associated with stress and depression, while stress played a mediating role between WFC and depression. The study also found that SWF, DR, and HN were the core symptoms of the WFC, stress, and depression network model, and SWF, IT, and DH were the bridge symptoms. Our findings clarify the interrelationships between WFC, stress, and depression among COs. The study also enhances the understanding of the factors influencing WFC in this population and provides valuable guidance for the development of future interventions, offering practical clinical significance.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to all participants involved in this study.

Authors’ contributions

JS and SC conceptualized and designed this study, JS conducted the data analyses, while both JS and SC were responsible for drafting the initial manuscript. SW oversaw the investigation, data curation, and formal analysis. SC and SW contributed to the methodology, investigation, and resources. XW and HG were responsible for data interpretation and manuscript revision. All authors participated in data collection and have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the 2030 Plan Technology and Innovation of China (2021ZD0200700). The funder had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, result interpretation, or manuscript drafting.

Data availability

The data supporting this research are available and can be requested from the corresponding author at any time.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. All procedures adhered to the study protocol and ethical guidelines. Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jingyan Sun and Shurui Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Huijuan Guo, Email: guohuijuan2023@csu.edu.cn.

Xiaoping Wang, Email: xiaop6@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Carleton RN, et al. Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(1):54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenhaus J, Allen T, Spector P. Health consequences of work–family conflict: The dark side of the work–family interface. In: Perrewé PL, Ganster DC, editors. Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being, vol. 5. Employee Health, Coping and Methodologies, Elsevier Science/JAI Press; 2006. p. 61–98.

- 3.Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10(1):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Wang L. Administrative governance and frontline officers in the Chinese prison system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Criminol. 2021;16(1):91–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sui GY, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among Chinese male correctional officers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2014;87(4):387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fusco N, et al. When our work hits home: trauma and mental disorders in correctional officers and other correctional workers. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:493391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobfoll SE, et al. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organi Behav. 2018;5:103–28. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267(9):1244–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinkelmann K, et al. Cognitive impairment in major depression: association with salivary cortisol. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown ES, et al. Hippocampal volume, spectroscopy, cognition, and mood in patients receiving corticosteroid therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(5):538–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell S, Macqueen G. The role of the hippocampus in the pathophysiology of major depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29(6):417–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gianaros PJ, et al. Anterior cingulate activity correlates with blood pressure during stress. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(6):627–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muscatell KA, et al. The stressed brain: neural underpinnings of social stress processing in humans. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2022;54:373–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.du Prel J-B, Peter R. Work-family conflict as a mediator in the association between work stress and depressive symptoms: cross-sectional evidence from the German lida-cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(3):359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao J, et al. Perceived organizational support impacts on the associations of work-family conflict or family-work conflict with depressive symptoms among Chinese doctors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(3):326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao J, et al. Association between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms among Chinese female nurses: the mediating and moderating role of psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(6):6682–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo JS, et al. Cellular and molecular basis for stress-induced depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(10):1440–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jerg-Bretzke L, et al. Correlations of the work-family conflict with occupational stress-a cross-sectional study among university employees. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers ML, Hom MA, Joiner TE. Differentiating acute suicidal affective disturbance (ASAD) from anxiety and depression symptoms: a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boschloo L, et al. A prospective study on how symptoms in a network predict the onset of depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(3):183–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried EI, et al. What are ‘good’ depression symptoms? Comparing the centrality of DSM and non-DSM symptoms of depression in a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren L, et al. Network structure of depression and anxiety symptoms in Chinese female nursing students. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Williams LJ. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work–family conflict. J Vocat Behav. 2000;56(2):249–76. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osman A, et al. The depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21): further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(12):1322–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antony MM, et al. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess. 1998;10(2):176–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. p. xvii, 507– xvii, 507. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50(1):195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opsahl T, Agneessens F, Skvoretz J. Node centrality in weighted networks: generalizing degree and shortest paths. Soc Networks. 2010;32(3):245–51. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong GS, Atkin-Plunk CA, Wells J. The relationship between work–family conflict, correctional officer job stress, and job satisfaction. Criminal Justice Behav. 2015;42(10):1066–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, et al. A research note on the association between work–family conflict and job stress among Chinese prison staff. Psychol Crime Law. 2017;23(7):633–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weale V, et al. Do work-family conflict or family-work conflict mediate relationships between work-related hazards and stress and pain? Am J Ind Med. 2023;66(9):780–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labrague LJ, Ballad CA, Fronda DC. Predictors and outcomes of work-family conflict among nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2021;68(3):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guille C, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1766–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grandey AA, Cropanzano R. The conservation of resources model applied to work–family conflict and strain. J Vocat Behav. 1999;54(2):350–70. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002;6(4):307–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shang S, O’Driscoll MP, Roche M. Moderating role of acculturation in a mediation model of work-family conflict among Chinese immigrants in New Zealand. Stress Health. 2017;33(1):55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin ZG, Zong LD, Wang Y, Huang XG, Zhang TY. Study on the psychological health status of the western provinces under the age of 40 prison police using symptom checklist 90. Chin J Social Med. 2008;25:345–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellison JM, Caudill JW. Working on local time: testing the job-demand-control-support model of stress with jail officers. J Crim Justice. 2020;70:101717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcosky T, Wing S. The healthy worker effect. Selection of workers and work forces. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1987;13(1):70–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are available and can be requested from the corresponding author at any time.