Abstract

Work-related musculoskeletal disorder (WRMD) complications are common in surgeons in general, but they are much higher in orthopedic surgeons. Numerous studies have explored the prevalence of WRMD among orthopedic surgeons internationally. However, little research has been carried out in Saudi Arabia on this matter. This review aimed to investigate it. A consistent and systematic search method was carried out to establish studies reporting the prevalence of WRMD among orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia. The search comprised published research from 2000 to June 2024. Nine eligible studies were incorporated for analysis, which involved 490 participants. The prevalence documented in these studies has exhibited an upward trend in recent years, with reported rates ranging from 36% to 90.3%. The most frequent anatomic site is found to be the lower back. There is a significant association between WRMD, smoking, and increasing age. The prevalence of WRMD is elevated among orthopedics based on existing information in the literature. Hospitals, along with orthopedic residency programs offering orthopedic-specialized ergonomics or occupational injury lectures as well as workshops, may help equip surgeons with the necessary knowledge and skills for addressing this issue.

Keywords: back pain, musculoskeletal disorders, review, saudi arabia, work-related

Introduction and background

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMDs) are challenging and are becoming a more common problem in workplaces in our society. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that 37% of back pain worldwide is caused by various occupational settings [1]. Physicians are liable to bowing, twisting, and maintaining an uncoordinated position for a long period, which are all known to be risk components for WRMD [2]. WRMD complications and incidence are common in surgeons in general, but they are much higher in orthopedic surgeons. It mostly affects the upper extremity, neck, and back regions [3]. Orthopedic surgery is a physically and mentally demanding specialty; thus, orthopedic surgeons are more prone to WRMD than their contemporaries. The pain and discomfort experienced are frequently caused by various contributory variables that all connect to either the lengthy and physically rigorous operations or likely the unconventional postures that orthopedics are put into throughout the surgeries [4,5]. The prevalence is the measure of current cases within a population at the time of a particular research period. Previous studies conducted in the United States on this topic reported an increased prevalence of WRMD among orthopedic surgeons, with some cases requiring surgical intervention [3,6]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia comparing the prevalence of WRMD between surgical and medical specialty residents found that being a surgeon and spending time doing interventional procedures are predisposing factors for musculoskeletal pain [2]. Multiple studies have attempted to study WRMDs' prevalence and anatomic sites in orthopedic surgeons [2,3,6]. However, research on this topic is very little in Saudi Arabia. This review aims to investigate WRMD prevalence among orthopedics and its associations in Saudi Arabia.

Review

Materials and methods

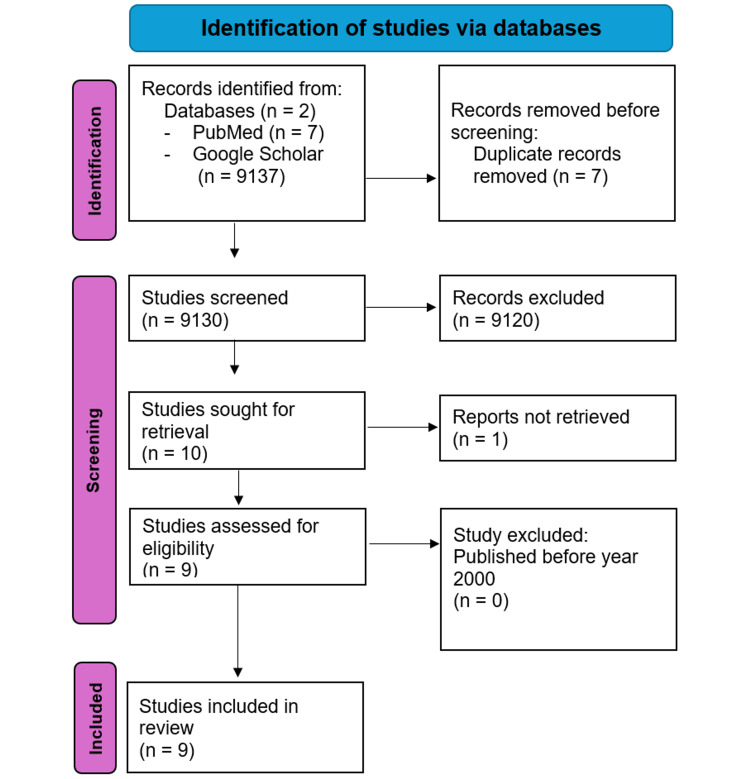

This review conformed to the criteria defined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The authors conducted electronic searches on PubMed and Google Scholar to systematically identify relevant published studies from 2000 to June 2024. The search terms included "Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Orthopedic Surgeons", "prevalence or incidence or epidemiology", and "Saudi Arabia". The search words were connected in varied ways to find applicable literature, and the search methods were modified for respective databases. In addition, relevant studies were sought in the reference lists of eligible articles.

The review included studies that focused specifically on orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia and reported statistics on the prevalence of WRMDs, categorized by age, sex, and anatomical site. Eligible studies employed either cluster sampling or random sampling methods and were published between the year 2000 and June 2024.

Studies conducted outside Saudi Arabia and studies published prior to the year 2000 were excluded. Additionally, studies where the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) is not functional or the article is otherwise inaccessible through available academic databases or direct contact with the journal, studies that did not explicitly identify orthopedic surgeons within their sample, those that focused on specialties other than orthopedics, and studies addressing work-related disorders other than musculoskeletal conditions were also excluded.

The reviewers individually appraised every article's title and abstract based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. To prevent doubt throughout all screening stages, we conducted further analysis and addressed issues through discussion to reach a consensus. Studies in the complete text were assessed for acceptability. The review comprised the remaining studies.

The reviewers extracted the data, which included the following: (1) first author, (2) study year, (3) study design, (4) average age, (5) sex, (6) rate of WRMD, (7) anatomic site of WRMD, (8) association with age, (9) association with sex, (10) association with smoking, and (11) association with residency year.

Results

The systematic database search provided articles; after discarding duplicates, 9130 articles were reviewed by titles/abstracts, and 9121 were discarded. Nine of these articles were then reviewed in complete text, yielding nine included publications (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Search and screening flowchart.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

*Only this anatomic site was investigated.

WRMD: work-related musculoskeletal disorder

| Author | Year | Type of study | City (region) | Total participants | Mean age | Rate of WRMD | Males N (%) | Females N (%) | Most common anatomic site of WRMD | Association with age | Association with gender | Association with smoking | Association with residency year |

| AlHussain et al. [7] | 2023 | Cross-sectional | Riyadh (Central) | 50 | - | Occasional occurrences (36%) | 44 (88%) | 6 (12%) | Shoulder* | 20-30: 0.037, 31-40: 0.087, 41-50: 0.029 | - | - | - |

| Alshareef et al. [8] | 2023 | Cross-sectional | All regions | 17 | - | 14 (82.3%) | - | - | Back and neck pain* | - | - | - | - |

| Al Mulhim et al. [9] | 2023 | Cross-sectional | Eastern region | 83 | 27.8 ± 2.2 | 63 (75.9%) | 52 (62.7%) | 31 (37.3%) | Lower back pain | 0.976 | 0.803 | 0.043 | 0.049 |

| Aseri et al.[10] | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Jeddah (Western) | 25 | - | 14 (56%) | - | - | Low back pain* | - | - | - | - |

| Al-Ruwaili and Khalil [11] | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Tabuk (Northern) | 15 | - | 9 (60%) | - | - | Low back pain* | - | - | - | - |

| Alzidani et al.[12] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Taif (Western) | 10 | - | 8 (90.3%) | - | - | Low back pain* | - | - | 0.033 | - |

| Aljohani et al.[13] | 2020 | Cross-Sectional | Almadinah Almunawwarah, Tabuk | 97 | - | 49.50% | 90 (93%) | 7 | Lower back pain | - | - | - | - |

| Alnefaie et al. [14] | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Jeddah (Western) | 14 | - | 8 (57.1%) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Al-Mohrej et al. [15] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Riyadh (Central) | 179 | 32.2 ± 7.7 | 67% | 173 (96.6%) | 6 (3.4%) | Lower back pain | 0.247 | 0.945 | 0.38 | - |

A total of nine studies were incorporated into this review (Table 1), all of which utilized a cross-sectional design. Of these, four studies focused specifically on orthopedic surgeons [7,9,13,15], while the remaining five included multiple surgical specialties, including orthopedics. The reported prevalence of WRMDs varied across studies, with the highest rates being 90.3% and 75.9%, as observed by Alzidani et al. and Al Mulhim et al., respectively [9,12]. Conversely, the lowest reported prevalence rates were 36% and 49.5%, as found by AlHussain et al. and Aljohani et al. [7,13]. In terms of the anatomical distribution of WRMD, three studies that examined multiple anatomical sites concluded that lower back pain was the most prevalent musculoskeletal complaint among participants [9,13,15]. Additionally, four studies limited their focus specifically to lower back pain [8,10-12]. And one only investigated shoulder pain [7]. Another study did not specify which anatomical site was most affected within the orthopedic surgeon population [14].

Al Mulhim et al. (P=0.043) and Alzidani et al. (P=0.033) reported significant findings from their studies that examined the relationship between smoking and WRMD [9,12]. Al-Mohrej et al. found no significant association [15]. Two studies looked into WRMD in terms of gender; however, neither discovered a statistically significant relationship [9,15]. Only one study examined WRMD in relation to residency year and found a significant association (P=0.049) [9]. Finally, three studies investigated age as a variable [7,9,15]; only one of them found a significant connection (P=0.029) [7].

Discussion

Studies included in the review showed that there is a high rate of WRMD among orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia [7-15], ranging from 36% up to 90.3%. These findings are consistent with a study conducted in 2022 by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) [6], with 86% of surgeons reporting a minimum of one musculoskeletal condition. Another study conducted by the Orthopedic Korean Society of Spine Surgery showed that 78.8% of the participants experienced WRMD in the past year [16]. A recent review done by Vasireddi et al. on the prevalence of WRMD in orthopedics and the ergonomics involved in surgery concluded that there is a high career prevalence of WRMD in orthopedics, as well as very minimal efforts to enhance surgical ergonomics [17]. According to Epstein et al., many surgical training residency programs do not give official (98%) or unofficial (75%) training for surgical ergonomics [18]. It suggests that physicians, even orthopedic surgeons, may not have the availability to training on evidence-based ergonomics of surgery, increasing their liability of developing WRMD later during their future careers. Institutions and orthopedic surgery residency training should provide orthopedic-specialized ergonomics or lectures on work injury to help educate surgeons on this specific issue.

The most common anatomic site for WRMD among the studies that investigated all sites in the review is lower back pain [9,13,15]. This is in accordance with a study published on orthopedic residents at the University of Iowa in 2014, which concluded a 55% lower back pain prevalence among the participants, the second highest in their sample [3]. Furthermore, another study conducted on orthopedic surgeons in New York concluded a 77% prevalence of back pain among respondents [19]. The rate of musculoskeletal pain, particularly back pain, is very high among orthopedic surgeons. This could be explained firstly by the prolonged durations of orthopedic surgeries which could reach to more than 10 hours depending on the case complexity and sub-specialty of the surgeon. Secondly, manipulating limb and application of force is an important part of the surgeries, and the lower back plays a crucial role in maintaining balance and supporting these movements.

Two studies included in the review found a significant association between smoking and WRMD [9,12]. It is well-documented that smoking is associated with regional pain [20]. Furthermore, previous studies investigating the effect of smoking on muscular and bone pain have collectively shown that it adversely affects bone mineral density and increases the number of fractures and bone and wound curing [21,22]. Thus, a significant association is logical. We recommend enhancing awareness among orthopedic surgeons, as their specialized surgical practices place them at heightened risk for developing musculoskeletal disorders. As previously noted, smoking exacerbates these risks, further compromising their health and professional performance.

Our review's limitations include a limited number of articles published regarding WRMD among orthopedic surgeons in the country and six studies only investigating one anatomic site. However, we demonstrated a pattern of possible elevated prevalence among orthopedic surgeons, which is crucial for the healthcare system.

Conclusions

Studies on WRMD among orthopedic surgeons are limited in Saudi Arabia. Despite this, an elevated prevalence of WRMD ranging from 36% to 90.3% was concluded. The lower back is the most frequent anatomic site among the studies, with variables such as smoking and increasing age having a significant association. We suggest that future studies explore the impact of patient and surgeon positions in the operating room and their association with musculoskeletal disorders to better understand their causes and increase awareness. Hospitals and orthopedic surgery residency programs should prioritize offering orthopedic-specialized ergonomics or work injury workshops to equip surgeons with the necessary knowledge and skills for addressing this critical issue.

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Omar A. Bokhary, Mohammad A. Alsolami, Anmar K. Alkindy, Mahmod S. Numan, Mohammed A. Jumah, Amro A. Mirza

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Omar A. Bokhary, Mohammad A. Alsolami, Anmar K. Alkindy, Mahmod S. Numan, Mohammed A. Jumah, Amro A. Mirza

Drafting of the manuscript: Omar A. Bokhary, Mohammad A. Alsolami, Anmar K. Alkindy, Mahmod S. Numan, Mohammed A. Jumah, Amro A. Mirza

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Omar A. Bokhary, Mohammad A. Alsolami, Anmar K. Alkindy, Mahmod S. Numan, Mohammed A. Jumah, Amro A. Mirza

References

- 1.The global burden of selected occupational diseases and injury risks: methodology and summary. Nelson DI, Concha-Barrientos M, Driscoll T, et al. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:400–418. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comparison of musculoskeletal pain prevalence between medical and surgical specialty residents in a major hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Alsultan A, Alahmed S, Alzahrani A, Alzahrani F, Masuadi E. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2018;2:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musculoskeletal pain in resident orthopaedic surgeons: results of a novel survey. Knudsen ML, Ludewig PM, Braman JP. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25328481/ Iowa Orthop J. 2014;34:190–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quality of life during orthopaedic training and academic practice: part 2: spouses and significant others. Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:0. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Occupational hazards facing orthopedic surgeons. Lester JD, Hsu S, Ahmad CS. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22530210/ Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012;41:132–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A survey of musculoskeletal disorders in the orthopaedic surgeon: identifying injuries, exacerbating workplace factors, and treatment patterns in the orthopaedic community. Swank KR, Furness JE, Baker E, Gehrke CK, Rohde R. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022;6:0. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Work-related shoulder pain among Saudi orthopedic surgeons: a cross-sectional study. AlHussain A, Almagushi NA, Almosa MS, et al. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevalence of back and neck pain among surgeons regardless of their specialties in Saudi Arabia. Alshareef L, Al Luhaybi F, Alsamli RS, Alsulami A, Alfahmi G, Mohamedelhussein WA, Almaghrabi A. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.49421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain (MSP) among orthopedic surgeons and residents in Saudi Arabia's eastern area. Al Mulhim FA, AlSaif HE, Alatiyah MH, Alrashed MH, Balghunaim AA, Almajed AS. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Characterizing occupational low back pain among surgeons working in Ministry of Health Hospitals in Jeddah City: prevalence, clinical features, risk, and protective factors. Aseri KS, Mulla AA, Alwaraq RM, Bahannan RJ. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Characterizing-Occupational-Low-Back-Pain-among-in-Aseri-Mulla/67bdda9bddc49be30bfee50160cb84da1806f3a0 J King Abdulaziz Univ Med Sci. 2019;26:19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevalence and associated factors of low back pain among physicians working at King Salman Armed Forces Hospital, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Al-Ruwaili B, Khalil T. https://oamjms.eu/index.php/mjms/article/view/oamjms.2019.787. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:2807–2813. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among Taif surgeons. Alzidani TH, Alturkistani AM, Alzahrani BS, Aljuhani AM, Alzahrani KM. Saudi J Health Sci. 2018;7:172. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among orthopedic surgeons in North West region of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Aljohani LZ, Batayyib SS, Ghabban KM, Koshok MY, Alshammari AN. Orthop Res Physiother. 2020;6:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musculoskeletal symptoms among surgeons at a tertiary care center: a survey based study. Alnefaie MN, Alamri AA, Hariri AF, et al. Med Arch. 2019;73:49–54. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2019.73.49-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Saudi orthopedic surgeons: a cross-sectional study. Al-Mohrej OA, Elshaer AK, Al-Dakhil SS, Sayed AI, Aljohar S, AlFattani AA, Alhussainan TS. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1:47–54. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.14.BJO-2020-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among spine surgeons. Choi SW, Lee JC, Jang HD, et al. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 2016;51:464–472. [Google Scholar]

- 17.High prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and limited evidence-based ergonomics in orthopaedic surgery: a systematic review. Vasireddi N, Vasireddi N, Shah AK, et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2024;482:659–671. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, Ruan QZ, Dennerlein JT, Singhal D, Lee BT. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:0. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prevalence of back and neck pain in orthopaedic surgeons in Western New York. Lucasti C, Maraschiello M, Slowinski J, Kowalski J. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022;6 doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smoking and musculoskeletal disorders: findings from a British national survey. Palmer KT, Syddall H, Cooper C, Coggon D. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:33–36. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The effect of tobacco smoking on musculoskeletal health: a systematic review. AL-Bashaireh AM, Haddad LG, Weaver M, Kelly DL, Chengguo X, Yoon S. J Environ Public Health. 2018;2018:4184190. doi: 10.1155/2018/4184190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The musculoskeletal effects of smoking. Porter SE, Hanley EN Jr. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:9–17. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]