Abstract

Purpose

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) measurements at ultra‐high field (UHF) suffer from strong saturation inhomogeneity. Retrospective correction of this inhomogeneity is possible to some extent, but requires a time‐consuming repetition of the measurement. Here, we propose a calibration‐free parallel transmit (pTx)‐based saturation scheme that homogenizes the saturation over the imaging volume, which we call PUlse design for Saturation Homogeneity utilizing Universal Pulses (PUSHUP).

Theory

Magnetization transfer effects depend on the saturation . PUSHUP homogenizes the saturation by using multiple saturation pulses with alternating ‐shims. Using a database of maps, universal pulses are calculated that remove the necessity of time‐consuming, subject‐based pulse calculation during the measurement.

Methods

PUSHUP was combined with a whole‐brain three‐dimensional‐echo planar imaging (3D‐EPI) readout. Two PUSHUP saturation modules were calculated by either applying whole‐brain or cerebellum masks to the database maps. The saturation homogeneity and the group mean CEST amplitudes were calculated for different ‐correction methods and were compared to circular polarized (CP) saturation in five healthy volunteers using an eight‐channel transmit coil at 7 Tesla.

Results

In contrast to CP saturation, where accurate CEST maps were impossible to obtain in the cerebellum, even with extensive ‐correction, PUSHUP CEST maps were artifact‐free throughout the whole brain. A 1‐point retrospective ‐correction, that does not need repeated measurements, sufficiently removed the effect of residual saturation inhomogeneity.

Conclusion

The presented method allows for homogeneous whole‐brain CEST imaging at 7 Tesla without the need of a repetition‐based ‐correction or online pulse calculation. With the fast 3D‐EPI readout, whole‐brain CEST imaging with 45 saturation offsets is possible at 1.6 mm resolution in under 4 min.

Keywords: CEST, magnetization transfer, parallel transmit, ultra‐high field, universal pulses

1. INTRODUCTION

The MRI signal contains information not only about the different tissue components, but also about the local magnetic, chemical and physical interactions of the spin system. Hence, chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) 1 imaging gives closer insights into biochemistry with unprecedented resolution. By selectively irradiating exchangeable protons, the measured water proton signal becomes attenuated due to the magnetization transfer by the labeled protons. Multiple repetitions of the experiment at different saturation frequencies allow the acquisition of a full Z‐spectrum and, through its analysis, the extraction of different image contrasts dependent on functional groups, such as amide (‐NH), amine (‐NH2) or hydroxyl (‐OH).

CEST experiments especially benefit from the increased spectral dispersion at higher field strengths and, moreover, from higher sensitivity and prolonged water relaxation. 2 Concurrently, CEST experiments at ultra‐high field (UHF) are hampered by stronger and inhomogeneities and higher RF power deposition in the tissue. In particular, whole‐brain acquisitions are aggravated by the wide range of variations, as the magnitude of the CEST signal gets strongly affected. Previous whole‐brain approaches 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 show that a correction for inhomogeneities is obligatory once varies by more than 10‐20%, prolonging the measurement due to the necessity to repeat the measurement at each saturation frequency with varied amplitude. 8 It has been shown that a sufficiently high amplitude is required for successful correction, which remains difficult, especially in the cerebellum. 3 This hampers the feasibility of applying CEST in studies of diseases that also affect the cerebellum.

To overcome these difficulties, parallel transmission (pTx)‐based approaches have been proposed. Tse et al 9 proposed SPIN 10 ‐based saturation modules and Liebert et al. 11 introduced MIMOSA which uses two pre‐defined ‐shims in an alternating pattern. For homogenization of the MT contrast, pTx pulse design for saturation homogeneity (PUSH) 12 method was introduced, that uses multiple, optimized ‐shims. The calculation of optimal pTx‐pulses can be time‐consuming. Instead of calculating subject‐specific pulses during the imaging session, universal pulses 13 (UP) are calculated in advance, based on a database of in vivo and maps.

In this work, we propose an alternative saturation module, based on parallel transmit PUlse design for Saturation Homogeneity utilizing Universal Pulses (PUSHUP). The feasibility of CEST saturation using similar pulses has been recently demonstrated by Delebarre et al. 14 In this work, we investigate the whole‐brain applicability of PUSHUP saturation and the need of retrospective correction of residual saturation inhomogeneity.

2. METHODS

2.1. Pulse design

In a preceding database study, channel‐wise maps using AFI 15 and maps using 3D multiple gradient recalled echo 16 have been acquired in 10 young, healthy volunteers. Additionally, a high‐resolution MPRAGE 17 was measured as anatomical reference for each subject. All pulse calculations were performed based upon this database, utilizing an in‐house developed program written in MATLAB R2021b (The Mathworks) and the Optimization Toolbox (Version 9.2). Pulse shapes were optimized using sequential quadratic programming, 18 available in the MATLAB function fmincon.

SAR management is purely based on limiting single channel (1.5 W) and total mean power (8 W) without considering the spatial SAR distribution. Pulse optimization was implemented to abide by these limitations.

The CEST effect, as well as magnetization transfer does not directly depend on the flip angle of the saturation pulses, but predominantly on the root‐mean‐square of the local amplitude, , during saturation. Therefore, PUSH homogenizes the . PUSHUP saturation constitutes of several saturation pulses with identical envelop function, but multiple, alternating ‐shims. In this work, cosine‐filtered Gaussian pulses were used. The ‐shims can be obtained by solving the minimization problem

| (1) |

Here, is the complex amplitude of the th ‐shim and the th coil, is the complex profile of the th coil, a regularization parameter that allows to trade homogeneity for SAR efficiency and is the target amplitude.

The norm in formula (1) can be evaluated with respect to different masks. This allows to calculate different pulses for whole‐brain and region‐specific applications. Using antspynet/brain_extraction, 19 whole‐brain masks were calculated and utilizing suit, 20 cerebellum / brain stem masks were extracted from the MPRAGE acquisitions.

Using both masks, PUSHUP pulses were calculated using 2 and 3 ‐shims, and their homogeneity was estimated by the normalized root‐mean‐square error of the resulting distribution within the masks of each subject in the database. Additionally, the total power per saturation pulse was calculated. Pulse calculation was performed for various and pulses with similar pulse energy as MIMOSA were selected for in vivo measurements. In order to reduce the total measurement time, only saturation schemes with three ‐shims were tested.

2.2. Data acquisition

Five young, healthy volunteers participated (21–31 years, two male, three female) in this study which were not included in the database study. All measurements were conducted on a 7T+ scanner (Siemens Healthineers) using a 32‐channel receive, 8‐channel transmit coil (Nova Medical). All subjects were scanned in accordance with the local ethics committee, requiring written informed consent before each examination.

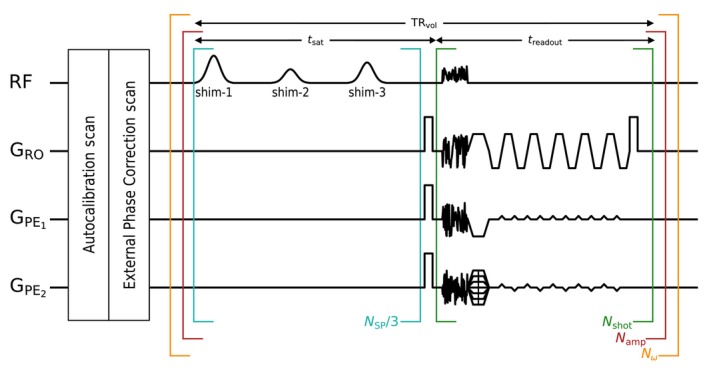

The sequence consists of two parts, depicted in Figure 1. The spectral selective CEST saturation period and the three‐dimensional‐echo planar imaging (3D‐EPI) imaging readout. The saturation module ( ms) contains saturation pulses of 15 ms duration, followed by a crusher gradient. Saturation pulses are repeated with alternating PUSHUP ‐shims with 15 ms interpulse delay. saturation offsets between and 45 ppm with denser sampling between 6 and 6 ppm were obtained for the Z‐spectrum.

FIGURE 1.

Pulse diagram of the PUlse design for Saturation Homogeneity utilizing Universal Pulses (PUSHUP) Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) sequence. The sequence is constituted of two modules. In the saturation modules, saturation pulses are applied, using three different, alternating ‐shims. After the last saturation pulse, a crusher gradient dephases transversal magnetization. Afterwards, a CAIPIRINHA accelerated multi‐shot three‐dimensional‐echo planar imaging (3D‐EPI) readout acquires a whole‐brain image. In each of the , universal binomial‐11 GRAPE is used for homogeneous water excitation. The brackets indicate the repetition order. For each of the off‐center frequencies, all saturation amplitudes are acquired in direct succession.

The saturation module is followed by a snapshot readout, using a whole‐brain 3D‐EPI sequence, as introduced in earlier publications. 3 , 7 However, the excitation pulse is changed to a universal binomial‐11 GRAPE 21 pulse for homogeneous water excitation and simultaneous fat suppression in the whole brain. This pulse was calculated on the same database as PUSHUP, but the flip angle was homogenized, instead of .

With identical settings, except for the saturation module ( ms, ms, ms, 1.61 mm isotropic nominal resolution, CAIPIRINHA 22 parallel imaging, 6/8 phase partial Fourier, EPI factor = 24, centric reordering), three CEST experiments have been performed:

PUSHUP‐WB: whole brain optimized

PUSHUP‐CE: cerebellum optimized

CP saturation

All experiments have been acquired with varied saturation amplitude to investigate different correction strategies. The PUSHUP saturations used 80%, 100%, and 120% of the target of 0.8 T. Due to the larger expected variation when CP saturation is used, the range was extended to 50%, 100%, and 150%. To avoid the immediate succession of high SAR saturation modules, each amplitude was used for one off‐center frequency before repeating this for subsequent frequencies.

In each subject, additional measurements have been performed. A high‐resolution (0.6 mm) whole‐brain MPRAGE 17 was acquired, utilizing the same excitation pulses as in the EPI readout. An individual‐channel map with 4 mm resolution was acquired, using 3DREAM. 23 Finally, two short 3D‐EPI reference scans without CEST saturation (1 with reversed ) were acquired for distortion correction.

For all CEST measurements, and the 3D‐EPI reference scans, shim currents were kept constant. However, the scanner frequency was updated before each new sequence to compensate for potential, EPI‐related frequency drifts.

2.3. Image processing

2.3.1. CEST quantification

A fully automated image processing pipeline has been applied individually to each CEST acquisition.

Preprocessing starts with applying ANTS denoising 24 to each of the 135 volumes of the CEST acquisition. Afterwards, each volume is corrected for geometric distortions by applying a voxel shift map, calculated from the EPI reference scans using TOPUP 25 . To correct for motion artifacts, each volume was registered to a reference volume using mcflirt. 26 In accordance to Zhang et al., 27 the volume measured with 100% target‐ and an off‐center frequency of 3.5 ppm was selected as reference volume. Finally, a brain mask was calculated based on the reference volume, utilizing antspynet/brain_extraction. 19

Voxel‐wise Z‐spectra are calculated from these processed volumes under consideration of the local shifts, estimated from the water peak. From the individual channel maps and the respective pulse files, a map (per subject) is calculated to correct the voxel‐wise Z‐Spectra for inhomogeneities 8 using linear interpolation, either based on the outer two amplitudes (2‐point) or on all three amplitudes (3‐point).

Afterwards, a five‐pool quantification of the ‐spectra, 28 including amides at +3.5 ppm, amines at +2.2 ppm, relayed nuclear Overhauser effect (rNOE) at 3.5 ppm, semisolid magnetization transfer (ssMT) at 1 ppm (according to Hua et al. 29 ) and direct saturation at 0 ppm, was performed to calculate peak selective CEST maps.

Additional to the Z‐spectrum‐based ‐corrections, a contrast‐based 1‐point ‐correction was explored, utilizing a method, recently introduced by Lipp et al. 30 for the ‐correction of MT saturation maps. In this method, the uncorrected MT saturation map is voxel‐wise multiplied by a factor

| (2) |

where is the local, normalized and a constant factor that needs calibration. In this work, we estimated for each CEST contrast individually. was chosen such that it minimizes the root‐mean‐square difference between the 3‐point ‐corrected and the 1‐point ‐corrected maps, evaluated with all voxels within the brain masks of all subjects. This was evaluated with PUSHUP‐WB whole‐brain maps, were the lowest inhomogeneities are to be expected. In summary, four different ‐corrections techniques were compared:

none

1‐point: contrast‐based

2‐point: Z‐spectrum‐based

3‐point: Z‐spectrum‐based

To investigate the validity of using the same for all subjects, a tailored calibration was performed for each subject in addition, where the data of the respective subject was excluded for calibration. The image analysis pipeline is summarized on the right side of Figure S1.

2.3.2. Segmentation

As a quality metric, we estimated the gray matter to white matter contrast in the CEST maps. This was done for the cerebellum and the cerebrum separately, as the accurate CEST quantification is difficult to establish in the cerebellum. A dedicated segmentation procedure was implemented. The left half of Figure S1 summarizes this process.

Based on the MPRAGE, two different brain segmentations have been performed. Using antspynet/deep_atropos, 19 a six tissue‐type segmentation was performed (cerebrospinal fluid, gray matter, white matter, deep gray matter, brain stem, and cerebellum). For each CEST acquisition, the MPRAGE was registered to the CEST reference image using ANTS/registrations. 31 Using the inverse transformation, the probability maps of the segmentation were transformed into the CEST image space. By using a threshold (0.5) a white matter (WM) mask, a combined gray matter/deep gray matter mask (GM), and a cerebellum (cereb) mask were calculated. Note, that the WM and GM masks only include the cerebrum.

After applying the same preprocessing to the MPRAGE that is used during deep_atropos (brain extraction, denoising, bias field correction, resampling), a three tissue type segmentation was performed using FSL fast 32 (cerebrospinal fluid, WM, GM). The probability maps were transformed to CEST image space. By intersecting the resulting white matter and gray matter segments with the cerebellum mask found using deep_atropos, cerebellar white matter (cWM) and cerebellar gray matter (cGM) segments were extracted.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Pulse design

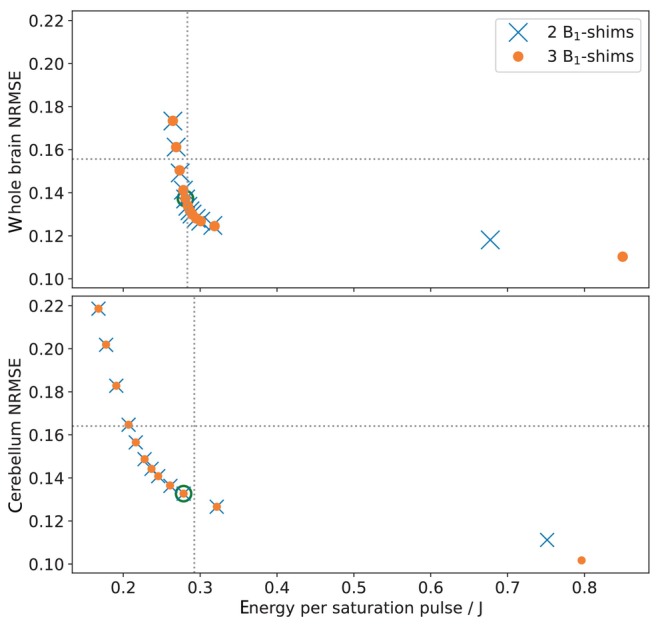

Figure 2 shows the normalized root‐mean‐square error of of PUSHUP saturation as a function of energy deposition per saturation pulse. The grid lines represent the performance of MIMOSA which has been used as a quality reference. In both brain regions, only for minimal regularization (highest homogeneity), the performance of 2 or 3 ‐shims differs. Only for very high regularization (lowest homogeneity), larger inhomogeneity than with MIMOSA is observed.

FIGURE 2.

PUlse design for Saturation Homogeneity utilizing Universal Pulses (PUSHUP) pulses have been calculated with a whole‐brain mask (top) and a cerebellum mask (bottom) with two ‐shims (blue) and three ‐shims (orange) using different . For each pulse, the normalized root‐mean‐square error (NRMSE) of and the pulse energy was calculated. decreases from left to right. The dotted lines represent the MIMOSA values when scaled to whole‐brain and cerebellum maps, respectively. The green circle mark the pulses which are used in this work. These are the pulses with the most homogeneous distribution, which are less SAR intense than MIMOSA.

The green circles mark the pulses that will be used in this study. These are the pulses with the most homogeneous distribution, which are less SAR intense than MIMOSA. In Table S1, the resulting ‐shims of the individual pulses are summarized.

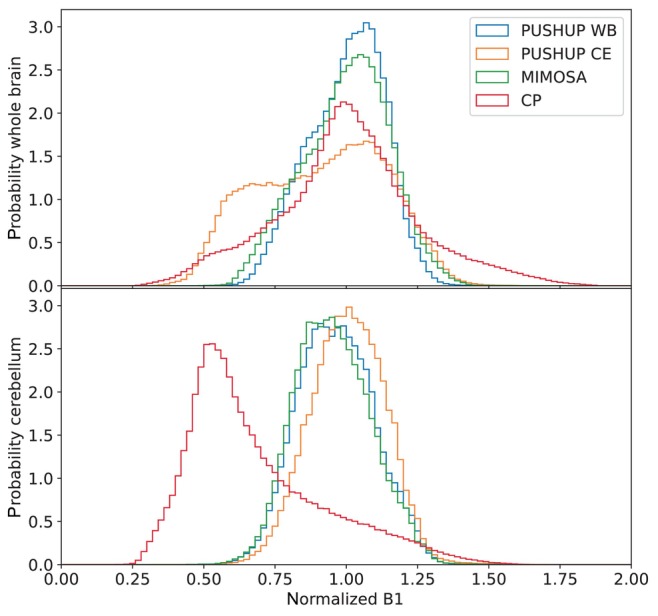

3.2. homogeneity

Figure 3 shows the normalized distributions (target = 1) for all measured saturation modules, and additionally MIMOSA for comparison. The top plot shows the distribution in the whole brain, including the cerebellum. The MIMOSA distribution is broader than the PUSHUP‐WB distribution. The of PUSHUP‐CE is much broader and appears almost bimodal. The CP distribution is also quite broad and has the highest values of all saturation modules.

FIGURE 3.

Histograms of the distributions, normalized to the target , of the different saturation modules and MIMOSA for comparison. Data from all subjects were merged. The top plot shows the distributions in the whole brain and the bottom plot shows the cerebellar distributions.

The bottom plot of Figure 3 shows the distribution in the cerebellum. The MIMOSA and PUSHUP‐WB distributions are very similar. The peaks of both histograms are slightly shifted toward smaller . The distribution of the PUSHUP‐CE saturation is slightly narrower and not shifted. The distribution of CP saturation is strongly shifted toward smaller and is by far the broadest.

Using PUSHUP‐WB, no voxel is close to the point of divergence (0.301) of the 1‐point ‐correction of the ssMT amplitude. In the whole brain, some voxels approach this value when PUSHUP‐CE and CP saturation is used. In the cerebellum, this value is only approached by CP saturation.

Table 1 shows the root‐mean‐square error of the normalized distribution of each saturation module, evaluated in the whole brain (left), and the cerebellum (right). In both regions, PUSHUP‐WB leads to a more homogeneous saturation than MIMOSA. PUSHUP‐CE is slightly less homogeneous than CP saturation in the whole brain and performs best in the cerebellum. As expected, CP saturation leads to by far the largest NRMSE in the cerebellum. Furthermore, PUSHUP saturation leads to a smaller variability of the individual subject homogeneity.

TABLE 1.

Root‐mean‐square error of the normalized evaluated in the whole‐brain (left) and in the cerebellum (right) each saturation, calculated over all voxels of all subjects (top row) and the group mean SD of the individual subjects (bottom row).

| Whole brain | Cerebellum | |

|---|---|---|

| PUSHUP‐WB | 12.9% | 14.3% |

| 13.3 1.2% | 13.6 1.4% | |

| PUSHUP‐CE | 24.3% | 13.4% |

| 23.9 1.2% | 13.0 1.0% | |

| MIMOSA | 15.3% | 14.6% |

| 15.3 1.3% | 13.8 2.0% | |

| CP | 22.3% | 39.7% |

| 25.0 2.3% | 39.2 4.6% |

3.3. 1‐point ‐correction

The weighting factors for each CEST contrast are summarized in Table 2. The optimal was found to be 1.44 for ssMT, 0.292 for rNOE, 0.108 for amide and 0.447 for amine. Note, that for the correction factor can diverge for low . For the ssMT maps, this will happen for .

TABLE 2.

Calibration results for the weighting in the 1‐point ‐correction for each CEST contrast.

| ssMT | rNOE | Amides | Amines | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1.437 | −0.292 | −0.108 | 0.447 |

| Sub‐1 | 1.475 | −0.317 | −0.108 | 0.428 |

| Sub‐2 | 1.416 | −0.293 | −0.019 | 0.563 |

| Sub‐3 | 1.409 | −0.284 | −0.123 | 0.424 |

| Sub‐4 | 1.441 | −0.252 | −0.138 | 0.439 |

| Sub‐5 | 1.451 | −0.308 | −0.139 | 0.399 |

| Mean | 1.438 0.027 | −0.291 0.025 | −0.105 0.050 | 0.451 0.065 |

Notes: In the upper row, the calibration is performed for all voxels in all subjects. In the following rows, the tailored calibration results are summarized. The last row shows the mean and SD of all tailored calibration results.

Abbreviations: rNOE, relayed nuclear Overhauser effect; ssMT, semisolid magnetization transfer.

The tailored calibration results, that exclude the particular subject's data, are also shown in Table 2 for each subject. Very similar values are obtained for each subject for ssMT and rNOE. Except for subject 2, where a lower value for the amides and a higher value for the amines is found, the tailored calibration yield highly similar results also for the other contrasts. On average, the tailored calibration results are in high agreement with the optimal determined on all subjects.

3.4. CEST quantification

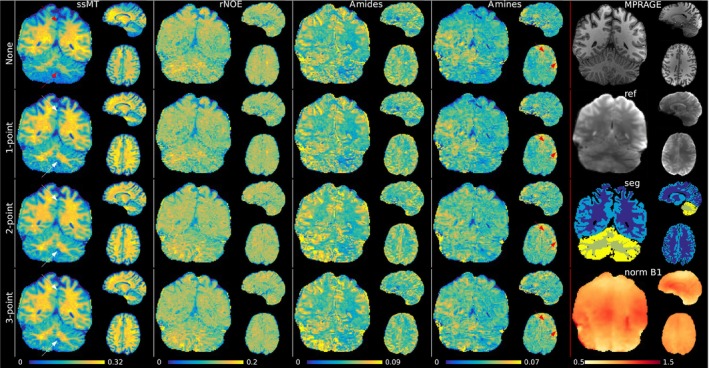

Figure 4 depicts the CEST maps of one subject obtained with PUSHUP‐WB with different ‐correction methods. In the top two rows of the right column, corresponding slices from the MPRAGE and the motion correction reference image are depicted. Homogeneous excitation is obvious in both. Below that, the segmentation results are depicted. In the bottom right corner, the nominal map is depicted. While, only small variations are visible in the axial slice, residual inhomogeneity can be seen in the longitudinal direction, visible best in the coronal slices. No major differences between the ‐correction methods are present in any map within the axial slice.

FIGURE 4.

PUSHUP‐WB CEST maps (semisolid magnetization transfer (ssMT), relayed nuclear Overhauser effect (rNOE), amide, amine from left to right) of one subject using the four ‐correction methods (no correction, 1‐point correction, 2‐point correction, 3‐point correction from top to bottom). In the right column, corresponding slices from the MPRAGE, the motion correction reference, the segmentation and the normalized map are shown. The red arrows point to quantification artifacts. Red arrows point to regions with quantification artifacts. White arrows point to successfully corrected artifacts.

The effects can be seen best in the ssMT images. Without ‐correction, the intensity profile matches quite well with the map. Increased measured signal can be found in the central parts of the brain, compared to the upper and lower parts, as indicated by the red arrows. These parts are the regions with the lowest . With the 1‐point ‐correction, this intensity profile can be compensated for, and the signal appears homogeneous through the whole brain, as indicated by the white arrows. No major differences are visible after 2‐point or 3‐point ‐correction.

In the amide signal, the inhomogeneity is less obvious without ‐correction and the signal already appears homogeneous. Due to the lower in the 1‐point ‐correction in the amide amplitude, the 1‐point corrected map looks almost identical. Using the 2‐point ‐correction, only small changes are visible. Again, no major difference between 2‐point and 3‐points ‐correction can be seen, which both lead to homogeneous signal in the whole brain.

The rNOE and amines maps are also depicted. Note that, due to the few relevant off‐center frequencies, image quality is poorer than for ssMT or amides. Very little contrast is visible in the rNOE map. In the amines map, some artifacts are visible that do not change strongly with the ‐correction method. Nevertheless, a GM/WM contrast is visible.

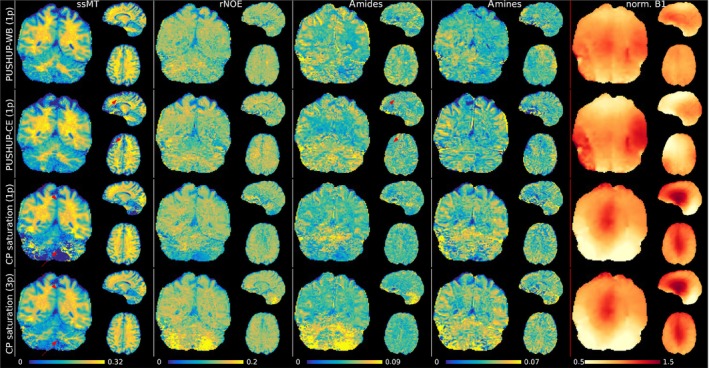

In Figure 5 whole‐brain CEST maps for each saturation module in the same subject are depicted. Both PUSHUP saturations use 1‐point ‐correction, while for CP saturation 1‐point and 3‐point ‐correction, which is the standard ‐correction approach in CP CEST. Additionally, the effective map is shown for each saturation module. For every saturation module, very clear GM/WM contrasts can be seen in the ssMT maps. Using 3‐point ‐correction, reduced contrast in cerebellum for CP saturation is visible, as indicated by the red arrows. In this region, the normalized drops to below 0.5. The image quality deteriorates using 1‐point ‐correction. In the same region, artificially high values (3‐point) or very low values (1‐point) are found in the amide map, completely overshadowing the contrast.

FIGURE 5.

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) maps (semisolid magnetization transfer (ssMT), relayed nuclear Overhauser effect (rNOE), amide and amine from left to right) measured with each saturation method (PUSHUP‐WB, PUSHUP‐CE and CP from top to bottom) after 1‐point ‐correction for PUSHUP saturation and 1‐point and 3‐point ‐correction for CP saturation, as 1‐point ‐correction could not sufficiently remove saturation strength related bias. In the right column, the relative is depicted. The red arrows point to quantification artifacts. These regions coincide with low regions. None of these artifacts are visible in the PUSHUP‐WB maps.

In the upper and frontal parts of the brain, the same artifacts can be seen with PUSHUP‐CE saturation in the ssMT maps, where again is small. In these regions, a lack of contrast is visible in the amides map. Outside these regions, a clear GM/WM contrast is visible in the amide maps. These artifacts do not occur in the PUSHUP‐WB maps and a homogeneous GM/WM contrast is visible in the amide maps throughout the whole brain.

3.5. GM/WM separation

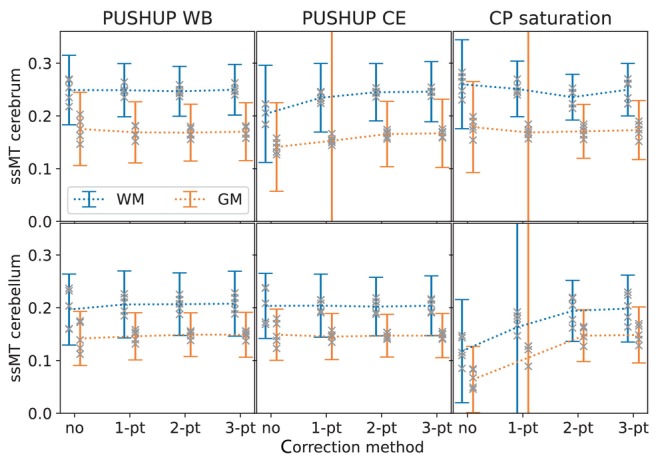

For each saturation module and ‐correction method, Figure 6 depicts the group means and standard deviations of the ssMT amplitudes within cerebral and cerebellar GM and WM masks. Additionally, the single subject mean values are depicted as gray crosses.

FIGURE 6.

Group mean and SD of the measured semisolid magnetization transfer (ssMT) amplitude within white matter (blue) and gray matter (orange) masks in the cerebrum (top) and the cerebellum (bottom) for the four ‐correction methods. This is shown for PUSHUP‐WB (left) PUSHUP‐CE (middle) and CP saturation (right). The gray crosses mark the single‐subject mean values.

In the case of PUSHUP‐WB, the mean ssMT amplitude is 0.249 0.066 in cerebral WM and 0.175 0.069 in cerebral GM without any ‐correction. While the mean amplitude is almost identical for all ‐correction methods, the SDs drop for 1‐point ‐correction (0.249 0.050, 0.169 0.058), drop further for 2‐point ‐correction (0.247 0.047, 0.168 0.054), and remain unchanged for 3‐point ‐correction (0.250 0.048, 0.170 0.055). Simultaneously, also the spread of single‐subject mean values decrease. When PUSHUP‐CE is applied, the group mean ssMT amplitude is 0.204 0.092 in cerebral white matter and 0.141 0.084 in cerebral gray matter with no ‐correction, which is clearly reduced, compared to PUSHUP‐WB. When 1‐point ‐correction is used the group mean ssMT amplitude is getting closer to the PUSHUP‐WB value (0.234 0.065, 0.153 0.230). Using 2‐point ‐correction, the group mean ssMT amplitude is almost identical to the PUSHUP‐WB case, but with increased SD (0.245 0.054, 0.166 0.063). Again, these values remain unchanged with 3‐point ‐correction (0.246 0.057, 0.167 0.065). With CP saturation the group mean ssMT values drop for 1‐point ‐correction, drop further for 2‐point ‐correction and increase back to the original value after 3‐point ‐correction (0.250 0.050, 0.173 0.056). This drop consistent across tissue but is more obvious in WM.

The bottom plot in Figure 6 shows the group mean ssMT amplitudes in the corresponding cerebellar masks. With PUSHUP‐WB, the group mean ssMT amplitude is 0.197 0.067 in cerebellar WM and 0.142 0.051 in cerebellar GM when no ‐correction is performed. Using 1‐point ‐correction, the mean amplitudes increase and the SDs decrease (0.206 0.064, 0.146 0.045). The drop in SD continues for 2‐point ‐correction (0.207 0.059, 0.149 0.041). These values remain relatively stable with 3‐point ‐correction (0.208 0.062, 0.149 0.043). Using PUSHUP‐CE the group mean ssMT amplitude is 0.203 0.062 in cerebellar WM and 0.149 0.048 in cerebellar gray white matter, if no ‐correction is performed. The SDs drop, while the group mean amplitude remain relatively stable after 1‐point ‐correction (0.204 0.060, 0.145 0.044), 2‐point ‐correction (0.204 0.056, 0.147 0.040), and 3‐point ‐correction (0.204 0.057, 0.147 0.042). Without ‐correction, CP saturation leads to much smaller ssMT values which increase with 1‐point ‐correction and increases further with a 2‐point ‐correction. The values do not change when a 3‐point ‐correction is used (0.198 0.063, 0.148 0.053).

CP saturation leads to the highest spread of single‐subject mean ssMT values in all four brain segments.

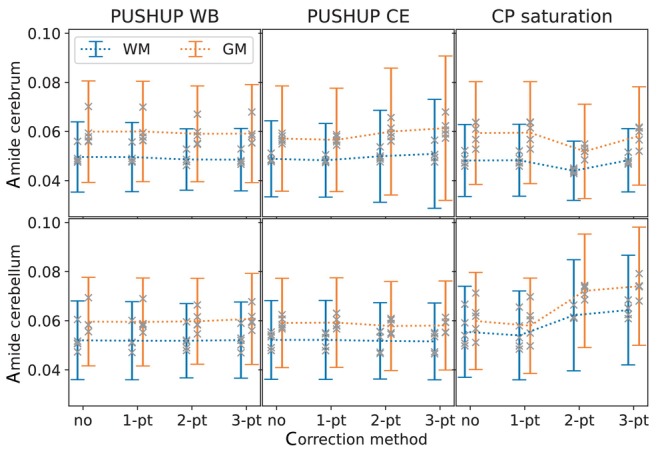

Figure 7 shows the group mean and the SDs of the amide amplitude in the four investigated brain segments for each saturation method and ‐correction method.

FIGURE 7.

Group mean and SD of the measured amides amplitude within white matter (blue) and gray matter (orange) masks in the cerebrum (top) and the cerebellum (bottom) for the four ‐correction methods. This is shown for PUSHUP‐WB (left) PUSHUP‐CE (middle) and CP saturation (right). The gray crosses mark the single‐subject mean values.

Using PUSHUP‐WB and without ‐correction, the group mean amide amplitude is 0.060 0.021 in cerebral GM and 0.050 0.014 in cerebral WM. When 1‐point ‐correction is used, the group mean value are almost identical (0.060 0.020, 0.050 0.014). Using 2‐point, the group mean values remain almost constant and standard variation slightly reduces in WM (0.059 0.020, 0.049 0.012). This remains almost constant for 3‐point ‐correction (0.059 0.020, 0.049 0.013). Using PUSHUP‐CE the group mean amide amplitudes are slightly reduced compared to the PUSHUP‐WB values (0.057 0.015, 0.049 0.015) without ‐correction. These values remain almost unchanged when 1‐point ‐correction is used. Using 2‐point ‐correction the group mean amide amplitudes and the SDs increase (0.60 0.026, 0.050 0.019). The SDs even increase for 3‐point ‐correction (0.061 0.029, 0.051 0.022). For CP saturation, the group mean amide amplitudes slightly increase for 1‐point ‐correction and drop for 2‐point ‐correction. With 3‐point ‐correction, CP saturation (0.058 0.020, 0.048 0.013) leads to similar values as PUSHUP‐WB.

The bottom plot of Figure 7 shows the group mean amide amplitudes in the cerebellar masks. The group mean amide signal is 0.060 0.018 in cerebellar GM and 0.052 0.015 without any ‐correction and remains almost unchanged for all other ‐correction methods. Very similar values can be found with PUSHUP‐CE (0.59 0.018, 0.52 0.016) without any ‐correction. Again, these values are almost constant across ‐correction methods. Using CP saturation, the group mean amide amplitudes are slightly increase, compared to the other methods (0.060 0.020, 0.056 0.019). While the mean and the SDs slightly decrease for 1‐point ‐correction (0.058 0.019, 0.054 0.018), they increase again with 2‐point (0.072 0.023, 0.062 0.023) and 3‐point ‐correction (0.074 0.024, 0.064 0.022).

4. DISCUSSION

Using an 8‐fold accelerated snapshot 3D‐EPI readout, a whole‐brain image with 1.61 mm isotropic nominal resolution can be acquired in 1.1 s. These images include the cerebellum, where previous, single‐channel experiments failed 3 to accurately quantify CEST effects, because of lacking amplitude. PUSHUP saturation was introduced here to overcome this challenge at UHF. The saturation module adds =3.6 s before the readout, resulting in only s per saturation off‐center frequency. With off‐center frequencies, optimized for amide imaging, whole‐brain CEST maps could be acquired in 3:40 min per amplitude.

Imaging of the cerebellum was aided by highly homogeneous water‐selective GRAPE excitation pulses. Homogeneous excitation can be observed in the MPRAGE. Fine structures can be clearly separated in the cerebellum. The motion correction reference image also shows high image quality in the cerebellum. Despite the high acceleration factor, no major parallel imaging artifacts or noise amplification are visible. The binomial GRAPE pulses suppress the fat signal effectively. No fat artifacts are visible in the CEST maps. Similar quantification artifacts as seen in previous, single channel experiments 3 can still be observed in this work in the cerebellum, when CP saturation is used together with homogeneous GRAPE excitation. This emphasizes the importance of homogenized saturation. When cerebellum optimized PUSHUP (PUSHUP‐CE) is used, similar artifacts can be seen in low regions that are far from the target region. For whole‐brain optimized PUSHUP (PUSHUP‐WB) on the other hand, no obvious quantification artifacts were found in the whole‐brain CEST maps.

PUSHUP saturation leads to artifact‐free, calibration‐free, whole‐brain CEST imaging, including the cerebellum. Compared to MIMOSA, the PUSHUP saturation module leads to a more homogeneous distribution, while being similarly SAR efficient. By reducing the regularization parameter during pulse calculation, the homogeneity can be further increased at the cost of increased SAR. Similarly, the SAR requirements can be decreased at the cost of less homogeneous saturation by increasing the regularization. This may be useful for applications beyond 7 Tesla where SAR restrictions are even harder to fulfill. PUSHUP saturation can be performed using a different number of ‐shims. In this work, PUSHUP saturation with two and three shims were calculated. If no regularization is performed (), three ‐shims lead to a more homogeneous in the whole brain and in the cerebellum mask. This comes at the cost of increased pulse energy. However, if regularization is introduced, the distribution, as well as the pulse energy, becomes almost identical.

The residual inhomogeneity of PUSHUP saturation is predominantly in head‐feet direction. This is because of the coil geometry, as all coil elements are placed in a ring around the head‐feet axis. Consequently, the signal drop‐off in this direction is identical and cannot be efficiently compensated for by superposition. 16‐channel transmit coils that use two rings 33 allow for an optimization in this direction and might be able to significantly improve the homogeneity. The PUSHUP patterns look very similar in all subjects. Despite the low variability of the individual subject homogeneity, the amplitude slightly varies within subjects. This could be minimized by using tailored pulses for every subject which is time‐consuming. A possible alternative approach would be to calculate universal pulses on multiple subsets of the database, based on head size or age and gender or a more sophisticated clustering algorithm. 34 However, this requires further research and a considerably larger database than the one used here.

While Delebarre et al. 14 showed excellent in‐plane homogeneity within different transversal slices, homogeneous whole‐brain CEST mapping is shown in this work using PUSHUP saturation in a group of five subjects. In the Delebarre paper, a VOP 35 ‐based SAR supervision is used and pulse calculation is implemented to maximize the homogeneity within the resulting limitations. In this paper, a power‐based SAR supervision is used and pulse power is reduced by introducing a regularization term in the cost function during pulse optimization. Regularization allows a more flexible use of the saturation module. The whole‐brain homogeneity of the saturation module, presented here, is similar to the whole‐brain optimized pulses in the work of Delebarre et al.

In contrast to MIMOSA, PUSHUP allows to easily select a target region, as shown with the cerebellum in this work, increasing the saturation homogeneity within the target region. However, saturation outside the target regions might be insufficient. Delebarre et al. 14 performed region‐specific optimization within one slab, centered around the imaging slice and increased the saturation homogeneity much more effectively than the cerebellum optimization in this work. This is not surprising, as the target region had a more limited extent in head‐feet direction. This might be valuable for region specific applications of CEST, for example, in brain cancer imaging.

Liebert et al. 11 showed that the CEST effect does depend on the relative contributions of the individual ‐shims. With sufficient ‐correction, PUSHUP‐WB and CP saturation lead to almost identical mean ssMT and amide amplitudes in the cerebrum. Similarly, almost identical mean values can be observed in the cerebellum with PUSHUP‐WB and PUSHUP‐CE. Furthermore, the SDs of the ssMT amplitude is lowest for the most homogeneous saturation method (PUSHUP‐WB in the cerebrum and PUSHUP‐CE in the cerebellum), while the SD of the amides amplitude is very similar. This indicates, that the benefit of a more homogeneous saturation overshadows a potential ‐shim‐specific bias in the CEST maps. Therefore, PUSHUP could also be interesting for other CEST contrasts, like glutamate CEST 36 and different saturation approaches, like steady‐state CEST. 37

Without any ‐correction, the mean ssMT amplitude for the different masks correlate with the pattern of the individual saturation module. In the cerebrum, the mean of PUSHUP‐WB and CP saturation is very close to the target , while PUSHUP‐CE leads to lower in the cerebrum. Consequently, the mean ssMT amplitudes of PUSHUP‐CE is reduced in the cerebrum for which PUSHUP‐CE was not optimized. The same effect can be seen in the cerebellum when CP saturation is used. Using a 1‐point ‐correction, this reduction in ssMT amplitude is less severe, but not fully compensated for. In these brain regions, the is outside the validity of the 1‐point ‐correction.

1‐point ‐correction reduces the SD of the ssMT amplitude measured with PUSHUP‐WB in all brain regions and also with PUSHUP‐CE in the cerebellum. Using 2‐point ‐correction, the SDs are further reduced, while the mean values remain constant. This indicates, that the bias due to the residual can substantially be reduced using 1‐point ‐correction. A 2‐point ‐correction slightly improves the ssMT precision at the cost of twice the acquisition time. However, no estimation bias is introduced by the 1‐point ‐correction. In contrast to the PUSHUP saturation, where no differences between 2‐point and 3‐point ‐correction were found, 3‐point ‐correction leads to higher ssMT values than 2‐point ‐correction for CP saturation, which is consistent with previous, single‐channel experiments. 3

The presented 1‐point ‐correction method was calibrated on the whole brain segments of all subjects. Nevertheless, it was possible to effectively reduce the saturation bias from all subjects and tissues. Tailored calibration only showed little differences to the global calibration. Thus, general ‐correction can be used for all tissues and subjects. This is in accordance to the original publication where it was applied to MT saturation mapping. 30 However, a recalibration may be needed for different saturation modules.

Hunger et al. 38 recently proposed a neural network‐based CEST quantification with implicit ‐correction, based on a single amplitude which is an alternative approach. In contrast, the method presented here, due to the linearity of the approach, requires less calibration and is potentially simpler to use. Furthermore, the neural network uses the tissue‐dependent signal evolution for each individual voxel, which might introduce a tissue bias. However, the neural network might be better in correcting for extreme values, where the assumption of linear dependence of the CEST contrasts to fails.

The influence of on the amide maps is much smaller, compared to ssMT. Therefore, the 1‐point ‐correction is subtle, and the amide maps are more similar to the uncorrected ones. Also, a 2‐point and 3‐point ‐correction does not change the maps significantly when PUSHUP‐WB is applied. Strong artifacts in low regions can be seen with CP saturation and with PUSHUP‐CE in regions that are far away from the cerebellum.

Consequently, a 1‐point ‐correction is sufficient for PUSHUP saturation, which eliminates the need of a repetition of the measurement. However, a subtle improvement of the ssMT maps can be inferred from the reduced SD in the ssMT amplitude when using a 2‐point ‐correction. This further emphasizes the importance of homogeneous saturation and presents an advantage over MIMOSA. A higher saturation homogeneity, in combination with highly homogeneous excitation pulses, not only reduces the necessary measurement time by a factor of 3, compared to single channel methods, but also enables imaging the cerebellum in a whole‐brain measurement where accurate CEST maps could not be obtained with CP saturation.

In neurodegenerative diseases, pathologies are usually spread across the whole brain. 39 Consequently, whole‐brain CEST mapping may become a helpful tool for the investigation of biochemical effects of neurodegeneration. This may in particular be of interest for the study of spinocerebellar ataxia, where metabolic changes in the brainstem and cerebellum have been detected via MR spectroscopy. 40

5. CONCLUSIONS

We present a SAR efficient, pTx‐based CEST saturation which leads to homogeneous saturation within the whole brain without subject‐specific pulse calculation. A 1‐point ‐correction is sufficient to compensate for residual inhomogeneities in the whole brain, including the cerebellum. The proposed saturation method was incorporated into a snapshot 3D‐EPI sequence with GRAPE excitation. This allows for high‐resolution whole‐brain CEST mapping in only 3:40 min.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work received financial support from the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme under grant agreement 885876 (AROMA) and through the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; funding code 01ED2109A) as part of the SCAIFIELD project under the aegis of the EU Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) (https://www.jpnd.eu).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Diagram of the image analysis pipelines. The left half shows the segmentation pipeline and the right half shows the CEST analysis. The CEST raw images get denoised and the distortion field is calculated from the EPI reference scans, using topup. The distortion field is applied to the denoised CEST data and a reference volume is defined. Motion correction is performed using FSL mcflirt. A B1rms map is calculated and registered to CEST image space using FSL flirt. After B0 and B1 correction of the CEST data, a voxel‐wise 5‐pool Lorentian fit is used to obtain water, ssMT, rNOE, amides, and amides peak amplitude maps. Tissue probability maps are obtained using deep_atropos segmentation of the MPRAGE. After some preprocessing of the MPRAGE additional probability maps are extracted using FSL fast. All probability maps are registered to CEST image space. By intersecting the gray matter and white matter mask from FSL fast with the cerebellum mask from deep_atropos, cerebellar gray matter and white matter are obtained.

Figure S2. B1rms maps of each individual B1 shim (rows 1–3) of PUSHUP‐WB 2‐shim, PUSHUP‐WB 3‐shim, MIMOSA, as well as unregularized (l = 0) PUSHUP‐WB 2‐shim and 3‐shim (from top to bottom). The fourth row shows the resulting B1rms of the respective saturation module. The fifth row shows the standard deviation of the contribution of the individual shims of the saturation module.

Figure S3. PUSHUP‐WB CEST maps of each of the five subjects using 1‐point B1‐correction.

Table S1. Individual channel phase and relative amplitudes of each B1‐shim during PUSHUP‐WB and PUSHUP‐CE saturation and MIMOSA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Völzke Y, Akbey S, Löwen D, et al. Calibration‐free whole‐brain CEST imaging at 7T with parallel transmit pulse design for saturation homogeneity utilizing universal pulses (PUSHUP). Magn Reson Med. 2025;93:630‐642. doi: 10.1002/mrm.30305

REFERENCES

- 1. Ward KMM, Aletras AHH, Balaban RSS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ladd ME, Bachert P, Meyerspeer M, et al. Pros and cons of ultra‐high‐field MRI/MRS for human application. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2018;109:1‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akbey S, Ehses P, Stirnberg R, Zaiss M, Stocker T. Whole‐brain snapshot CEST imaging at 7 T using 3D‐EPI. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82:1741‐1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones CK, Polders D, Hua J, et al. In vivo three‐dimensional whole‐brain pulsed steady‐state chemical exchange saturation transfer at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1579‐1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heo HY, Jones CK, Hua J, et al. Whole‐brain amide proton transfer (APT) and nuclear overhauser enhancement (NOE) imaging in glioma patients using low‐power steady‐state pulsed chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging at 7T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44:41‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liebert A, Tkotz K, Herrler J, et al. Whole‐brain quantitative CEST MRI at 7T using parallel transmission methods and B1+ correction. Magn Reson Med. 2021;86:346‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mueller S, Stirnberg R, Akbey S, Scheffler K, Stöcker T, Zaiss M. Whole brain snapshot CEST at 3T using 3D‐EPI: Aiming for speed, volume, and homogeneity. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84:2469‐2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Windschuh J, Zaiss M, Meissner J‐E, et al. Correction of B1‐inhomogeneities for relaxation‐compensated CEST imaging at 7T. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:529‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tse DHY, Andre da Silva N, Poser BA, Jon Shah N. B1+ inhomogeneity mitigation in CEST using parallel transmission. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:2216‐2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malik SJ, Keihaninejad S, Hammers A, Hajnal JV. Tailored excitation in 3D with spiral nonselective (SPINS) RF pulses. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1303‐1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liebert A, Zaiss M, Gumbrecht R, et al. Multiple interleaved mode saturation (MIMOSA) for B1+ inhomogeneity mitigation in chemical exchange saturation transfer. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82:693‐705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leitao D, Tomi‐Tricot R, Bridgen P, et al. Parallel transmit pulse design for saturation homogeneity (PUSH) for magnetization transfer imaging at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2022;88:180‐194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gras V, Vignaud A, Amadon A, Le Bihan D, Boulant N. Universal pulses: a new concept for calibration‐free parallel transmission. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:635‐643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Delebarre T, Gras V, Mauconduit F, Vignaud A, Boulant N, Ciobanu L. Efficient optimization of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI at 7 T using universal pulses and virtual observation points. Magn Reson Med. 2023;90(1):51‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yarnykh VL. Actual flip‐angle imaging in the pulsed steady state: a method for rapid three‐dimensional mapping of the transmitted radiofrequency field. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:192‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanayama S, Kuhara S, Satoh K. In vivo rapid magnetic field measurement and shimming using single scan differential phase mapping. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:637‐642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mugler JP, Brookeman JR. Three‐dimensional magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient‐echo imaging (3D MP RAGE). Magn Reson Med. 1990;15:152‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoyos‐Idrobo A, Weiss P, Massire A, Amadon A, Boulant N. On variant strategies to solve the magnitude least squares optimization problem in parallel transmission pulse design and under strict sar and power constraints. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2014;33:739‐748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tustison NJ, Cook PA, Holbrook AJ, et al. The ANTsX ecosystem for quantitative biological and medical imaging. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diedrichsen J. A spatially unbiased atlas template of the human cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2006;33:127‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Damme L, Mauconduit F, Chambrion T, Boulant N, Gras V. Universal nonselective excitation and refocusing pulses with improved robustness to off‐resonance for magnetic resonance imaging at 7 tesla with parallel transmission. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85:678‐693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Breuer FA, Martin B, Heidemann RM, Mueller MF, Griswold MA, Jakob PM. Controlled aliasing in parallel imaging results in higher acceleration (CAIPIRINHA) for multi‐slice imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:684‐691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ehses P, Brenner D, Stirnberg R, Pracht ED, Stöcker T. Whole‐brain B1‐mapping using three‐dimensional DREAM. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82:924‐934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manjón JV, Coupé P, Martí‐Bonmatí L, Collins DL, Robles M. Adaptive non‐local means denoising of MR images with spatially varying noise levels. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:192‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin‐echo echo‐planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2003;20:870‐888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825‐841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y, Heo H‐Y, Lee DH, et al. Selecting the reference image for registration of CEST series. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:756‐761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zaiss M, Windschuh J, Paech D, et al. Relaxation‐compensated CEST‐MRI of the human brain at 7T: unbiased insight into NOE and amide signal changes in human glioblastoma. Neuroimage. 2015;112:180‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, Smith SA, Van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:786‐793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lipp I, Kirilina E, Edwards LJ, et al. B1+‐correction of magnetization transfer saturation maps optimized for 7T postmortem MRI of the brain. Magn Reson Med. 2023;89:1385‐1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2033‐2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation‐maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:45‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. May MW, Hansen SLJD, Mahmutovic M, et al. A patient‐friendly 16‐channel transmit/64‐channel receive coil array for combined head–neck MRI at 7 tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2022;88:1419‐1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raphaël T‐T, Gras V, Thirion B, et al. SmartPulse, a machine learning approach for calibration‐free dynamic RF shimming: preliminary study in a clinical environment. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82:2016‐2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eichfelder G, Gebhardt M. Local specific absorption rate control for parallel transmission by virtual observation points. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:1468‐1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18:302‐306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomas Dixon W, Hancu I, James Ratnakar S, Dean Sherry A, Lenkinski RE, Alsop DC. A multislice gradient echo pulse sequence for CEST imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:253‐256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hunger L, Rajput JR, Klein K, et al. DeepCEST 7 T: fast and homogeneous mapping of 7 T CEST MRI parameters and their uncertainty quantification. Magn Reson Med. 2023;89:1543‐1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Spreading of pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: a focus on human studies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:109‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krahe J, Binkofski F, Schulz JB, Reetz K, Romanzetti S. Neurochemical profiles in hereditary ataxias: a meta‐analysis of magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;108:854‐865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Diagram of the image analysis pipelines. The left half shows the segmentation pipeline and the right half shows the CEST analysis. The CEST raw images get denoised and the distortion field is calculated from the EPI reference scans, using topup. The distortion field is applied to the denoised CEST data and a reference volume is defined. Motion correction is performed using FSL mcflirt. A B1rms map is calculated and registered to CEST image space using FSL flirt. After B0 and B1 correction of the CEST data, a voxel‐wise 5‐pool Lorentian fit is used to obtain water, ssMT, rNOE, amides, and amides peak amplitude maps. Tissue probability maps are obtained using deep_atropos segmentation of the MPRAGE. After some preprocessing of the MPRAGE additional probability maps are extracted using FSL fast. All probability maps are registered to CEST image space. By intersecting the gray matter and white matter mask from FSL fast with the cerebellum mask from deep_atropos, cerebellar gray matter and white matter are obtained.

Figure S2. B1rms maps of each individual B1 shim (rows 1–3) of PUSHUP‐WB 2‐shim, PUSHUP‐WB 3‐shim, MIMOSA, as well as unregularized (l = 0) PUSHUP‐WB 2‐shim and 3‐shim (from top to bottom). The fourth row shows the resulting B1rms of the respective saturation module. The fifth row shows the standard deviation of the contribution of the individual shims of the saturation module.

Figure S3. PUSHUP‐WB CEST maps of each of the five subjects using 1‐point B1‐correction.

Table S1. Individual channel phase and relative amplitudes of each B1‐shim during PUSHUP‐WB and PUSHUP‐CE saturation and MIMOSA.