Abstract

Background

Motoric cognitive risk (MCR) syndrome as a pre-dementia syndrome often co-occurring with chronic health conditions. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of MCR and its association with cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity among older people living in rural China.

Methods

This population-based study included 1450 participants who were aged ≥ 60 years (66.2% women) and who undertook the second wave examination of the Confucius Hometown Aging Project in Shandong, China when information to define MCR was collected. Data were collected through in-person interviews, clinical examinations, and laboratory tests. Cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity were defined following the international criteria. MCR was defined as subjective cognitive complaints and slow gait speed in individuals free of dementia and functional disability. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the associations of MCR with multimorbidity.

Results

MCR was present in 6.3% of all participants, and the prevalence increased with advancing age. Cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and increased serum cystatin C were associated with increased likelihoods of MCR (multivariable-adjusted odds ratio range: 1.90–3.02, P < 0.05 for all). Furthermore, there was a dose-response relationship between the number of cardiometabolic diseases and panvascular diseases and the likelihood of MCR. The multivariable-adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of MCR associated with cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity were 2.47 (1.43–4.26) and 3.85 (2.29–6.47), respectively.

Conclusions

Older adults with cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity are at a higher likelihood of MCR. These findings may have implications for identifying older adults at pre-dementia state as targets for early preventive interventions to delay dementia onset.

Motoric cognitive risk (MCR) syndrome is defined as a pre-dementia syndrome characterized by the presence of cognitive complaints and slow gait in older individuals without dementia or mobility disability.[1] Previous studies have shown that MCR in old age is associated with dementia, frailty, falls, and mortality.[2] Notably, unlike other pre-dementia syndromes such as mild cognitive impairment, the diagnosis of MCR does not necessitate specific neuropsychological and physical functional tests or biomarkers, making it an easily applicable tool in clinical and primary care settings for early detection of individuals at risk for dementia. As effective treatments for dementia are limited, targeting pre-dementia syndromes and modifiable factors allows for early interventions to slow down the progression of cognitive impairment in older adults.

Cognitive impairment often co-exists with various chronic conditions in older adults, particularly vascular diseases that affect the brain, the heart, and blood vessels. One group of such disease is referred to as cardiometabolic diseases, which primarily impact the cardiovascular system and metabolic health. They may lead to cognitive decline, including dementia, through mechanisms such as cerebral perfusion damage, brain structural changes, inflammation, and β-amyloid deposition.[3,4] While there has been growing research on the impact of individual cardiometabolic diseases (e.g., hypertension and stroke) on cognitive function,[2,5] few studies have explored the association between cardiometabolic multimorbidity (the presence of multiple cardiometabolic diseases) and cognitive impairment.[6] Given the increasing prevalence of cardiometabolic multimorbidity among older adults, investigating its health impact on MCR, which may extend beyond those of single conditions, could provide valuable insights into disease clustering and inform clinical practice.[7] Furthermore, panvascular diseases, a constellation of systemic vascular diseases with atherosclerosis as the common pathological feature, affect vital organs like the heart, brain, kidney, and limb.[8] Atherosclerosis has been linked with the onset and accelerated progression of cognitive dysfunction.[9] Therefore, exploring the concept of panvascular diseases can offer a holistic perspective of the body’s structure and function to understand vascular changes and cognitive function, which merits further research.

Thus, in this population-based study, we aimed to explore the prevalence and demographic distribution of MCR and the associations of MCR with multimorbidity, especially with regard to cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity, among older people living in rural China.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This was a population-based cross-sectional study. The study participants were derived from the Confucius Hometown Aging Project (CHAP) who undertook the second wave (2014–2016) of data collection of the project when data on factors to define MCR were collected. The CHAP was aimed at investigating cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerotic mechanisms in aging and health, as previously reported.[10,11] Briefly, all registered residents who were aged 60 years and older living in the Xing Long Zhuang community near Qufu, Shandong, China in June 2014, were eligible for the second wave examination of CHAP. Data were collected by a physician at the local hospital that provides healthcare services to the community residents, through face-to-face interviews, clinical examinations, and laboratory tests. In total, 1521 persons were examined, of these, 21 persons with missing information on MCR and 50 persons with mobility disability or dementias were excluded, leaving 1450 subjects for the current analysis.

All waves of data collection in CHAP were approved by the Ethics Committee at Jining No.1 People’s Hospital of Jining Medical University, Shandong, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, or in the case of cognitively impaired persons, from informants. Research within CHAP had been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Collection

Data on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking and alcohol consumption), medical conditions, and use of medications were collected. Specifically, physical examinations were conducted to collect data on weight, height, and arterial blood pressure. Laboratory tests were performed to measure fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and serum cystatin C following standard methodology. Details of the data collection procedures have been reported previously.[10,12,13]

Measurements

Cardiometabolic multimorbidity

Cardiometabolic diseases included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure.[14] Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg (mean of two readings) or current use of antihypertensive drugs,[12,13] diabetes mellitus as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or current use of oral blood glucose-lowering medications or insulin,[15] and obesity as body mass index ≥ 28 kg/m2.[12] Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol > 6.22 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥ 2.26 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥ 4.14 mmol/L, or the use of hypolipidemic drugs.[16] Cerebrovascular disease (i.e., stroke and transient ischemic attacks), ischemic heart disease (i.e., angina and myocardial infarction), and heart failure were ascertained according to self-reported physician diagnosis. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more of the seven cardiometabolic diseases.

Panvascular multimorbidity

Panvascular diseases included ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, kidney dysfunction, and peripheral artery diseases (e.g., carotid and upper extremity artery diseases), with atherosclerosis being the common pathological feature.[8] Ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease were defined as described above. Renal dysfunction associated with atherosclerosis was defined as serum cystatin C concentration > 1 mg/L,[17,18] because previous studies suggest that serum cystatin C is a valid marker for renal function and a novel marker for coronary atherosclerosis as well.[19,20] In addition, carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) on the right and left internal carotid artery was assessed by clinical sonographer using color Doppler ultrasonography (Vivid 7 ultrasound system and a 7- to 10-MHz transducer) following a standardized protocol. Increased cIMT, an indicator of carotid artery disease, was defined as cIMT ≥ 1.81 mm on either side.[21] Another indicator of peripheral artery disease was subclavian stenosis, which was suggestive by an interarm systolic blood pressure difference ≥ 10 mmHg to reflect the influence of atherosclerosis in upper limb arteries.[22,23] Panvascular multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more of the five vascular diseases.

MCR

The MCR syndrome was defined following the criteria proposed by Verghese, et al.,[24] which include: (1) subjective memory complaints; (2) slow gait speed; (3) preserved activities of daily living (ADL) and without mobility disability; and (4) absence of dementia. The presence of subjective cognitive complaints was ascertained by the participant’s positive response to the question ‘Do you feel you have more problem with your memory than most?’ in the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale.[25,26] Gait speed was measured by the average time of two standard six-meter walking test. Slow gait speed was defined as walking speed one standard deviation or more below age- and sex-appropriate mean values established in the present cohort.[25] Preserved ADL, including bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding, were determined using the Katz Index of Independence in ADL.[27] Those with dependence on any of the aforementioned ADL were excluded. Participants were considered not to have dementia if they had a Mini-Mental State Examination score > 17 for individuals without formal education, > 20 for those with 1–6 years of education (primary school), and > 24 for those with ≥ 7 years of education (middle school or above).[28]

Covariates

Demographic factors were considered as covariate, including age (in years), sex, education (no formal schooling, primary school, and middle school or above), marital status (married and single/widowed/divorced), ethnicity, and occupation. Lifestyle factor, including smoking (never, former, and current), alcohol intake (never, former, and current), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and sleeping quality, were assessed and defined as previously reported.[12]

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of study participant by MCR status were described as counts (percentages) and mean ± SD and compared using Student’s t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution or Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables. Logistic regression models were performed to estimate odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI for MCR associated with chronic diseases while controlling for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Participants

Of the 1450 participants, the mean age was 73.5 ± 5.6 years, 66.2% were women, 22.8% attended middle school or above, 56.3% were farmers/self-employed, and 81.7% were married; 11% were current smokers, 12% had alcohol drinking habits, and 16.7% reported poor sleep quality (Table 1). Participants with MCR were older, more likely to be female, had lower education levels, and were less likely to engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants.

| Demographic or lifestyle factors | Total sample (n = 1450) |

Motoric cognitive risk syndrome | ||

| No (n = 1358) | Yes (n = 92) | P-valueb | ||

| Data are presented as means ± SD or n (%). aRefer to the number of subjects added was not equal to the total sample size due to missing data on smoking (n = 64), alcohol drinking (n = 33), and sleep quality (n = 15). bRefer to the test of differences between participants with and without motoric cognitive risk syndrome. | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, yrs | 73.51 ± 5.6 | 73.36 ± 5.6 | 75.89 ± 5.7 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.038 | |||

| Male | 490 (33.8%) | 468 (95.5%) | 22 (4.5%) | |

| Female | 960 (66.2%) | 890 (92.7%) | 70 (7.3%) | |

| Education | 0.012 | |||

| No formal school | 509 (35.1%) | 465 (91.4%) | 44 (8.6%) | |

| Primary school | 611 (42.1%) | 575 (94.1%) | 36 (5.9%) | |

| Middle school or above | 330 (22.8%) | 318 (96.4%) | 12 (3.6%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.807 | |||

| Han | 1437 (99.1%) | 1346 (93.7%) | 91 (6.3%) | |

| Others | 13 (0.9%) | 12 (92.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Occupation | 0.125 | |||

| Public sector | 206 (14.2%) | 197 (95.6%) | 9 (4.4%) | |

| Factory worker | 428 (29.5%) | 406 (94.9%) | 22 (5.1%) | |

| Farmer/Self-employed | 816 (56.3%) | 755 (92.5%) | 61 (7.5%) | |

| Marital status | 0.004 | |||

| Married | 1184 (81.7%) | 1119 (94.5%) | 65 (5.5%) | |

| Singe/Widowed/Divorced | 264 (17.7%) | 237 (89.8%) | 27 (10.2%) | |

| Lifestyle behaviors | ||||

| Smokinga | 0.138 | |||

| Never | 1076 (74.2%) | 1006 (93.5%) | 70 (6.5%) | |

| Former | 151 (10.4%) | 141 (93.4%) | 10 (6.6%) | |

| Current | 159 (11.0%) | 155 (97.5%) | 4 (2.5%) | |

| Alcohol drinkinga | 0.121 | |||

| Never | 1163 (80.2%) | 1082 (93.0%) | 81 (7.0%) | |

| Former | 80 (5.5%) | 75 (93.8%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| Current | 174 (12.0%) | 169 (97.1%) | 5 (2.9%) | |

| Moderate-to-rigorous physical activity | ||||

| No | 1202 (82.9%) | 1117 (92.9%) | 85 (7.1%) | 0.012 |

| Yes | 248 (17.1%) | 241 (97.2%) | 7 (2.8%) | |

| Sleeping qualitya | ||||

| Normal/Good/Very good | 1193 (82.3%) | 1123 (94.1%) | 70 (5.9%) | 0.062 |

| Bad/Very bad | 242 (16.7%) | 220 (90.9%) | 22 (9.1%) | |

Of all the study participants, 18.7%, 28.0%, and 48.2% had only one, two, and three or more of the 10 included cardiometabolic and panvascular diseases, respectively. Hypertension (72.4%) was the most prevalent chronic disease, followed by increased serum cystatin C (54.6%), dyslipidemia (37.8%), and diabetes mellitus (23.9%) (Table 2). The average number of cardiometabolic and panvascular diseases per participant was 2.0 ± 1.3 and 1.0 ± 0.8, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2. Associations of individual cardiometabolic and panvascular diseases with motoric cognitive risk syndrome.

| Individual chronic health conditions | Number of subjects (n = 1450) |

Motoric cognitive risk syndrome | ||

| Number of cases | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| OR (95% CI) was adjusted for age, sex, educational level, ethnicity, occupation, marital status, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity habits, and sleep quality. aRefer to the number of subjects added was not equal to the total sample size due to missing data on diabetes mellitus (n = 1), dyslipidemia (n = 3), obesity (n = 5), carotid artery disease (n = 140), and serum cystatin C (n = 15). | ||||

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 400 (27.6%) | 16 (4.0%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1050 (72.4%) | 76 (7.2%) | 1.39 (0.78–2.45) | 0.260 |

| Diabetes mellitusa | ||||

| No | 1102 (76.0%) | 69 (6.3%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 347 (23.9%) | 23 (6.6%) | 0.87 (0.51–1.49) | 0.610 |

| Dyslipidemiaa | ||||

| No | 899 (62.0%) | 53 (5.9%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 548 (37.8%) | 39 (7.1%) | 1.26 (0.79–2.01) | 0.340 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ||||

| No | 1277 (88.1%) | 69 (5.4%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 173 (11.9%) | 23 (13.3%) | 3.02 (1.75–5.22) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||

| No | 1123 (77.4%) | 58 (5.2%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 327 (22.6%) | 34 (10.4%) | 2.05 (1.27–3.30) | 0.003 |

| Heart failure | ||||

| No | 1359 (93.7%) | 78 (5.7%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 91 (6.3%) | 14 (15.4%) | 2.80 (1.42–5.50) | 0.003 |

| Obesitya | ||||

| No | 1104 (76.1%) | 66 (6.0%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 341 (23.5%) | 26 (7.6%) | 1.35 (0.81–2.26) | 0.249 |

| Carotid artery diseasea | ||||

| No | 1250 (86.2%) | 76 (6.1%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 60 (4.1%) | 4 (6.7%) | 1.15 (0.39–3.39) | 0.807 |

| Subclavian stenosis | ||||

| No | 1398 (96.4%) | 88 (6.3%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 52 (3.6%) | 4 (7.7%) | 1.41 (0.47–4.19) | 0.541 |

| Increased serum cystatin Ca | ||||

| No | 652 (45.0%) | 24 (3.7%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 783 (54.0%) | 64 (8.2%) | 1.90 (1.11–3.26) | 0.023 |

Table 3. Associations of multimorbidity and motoric cognitive risk syndrome.

| Multimorbidity | Number of subjects (n = 1450) |

Motoric cognitive risk syndrome | ||

| Number of cases | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Data are presented as means ± SD or n (%). OR (95% CI) was adjusted for age, sex, educational level, ethnicity, occupation, marital status, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity habits, and sleep quality. aRefer to cardiometabolic diseases included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure. bRefer to panvascular diseases included ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, carotid artery disease, subclavian stenosis, and increased serum cystatin C. cRefer to chronic diseases included the 10 chronic diseases above-mentioned, which are described in the methods section. | ||||

| Cardiometabolic multimorbiditya | ||||

| Number of cardiometabolic diseases | 1.99 ± 1.34 | – | 1.31 (1.12–1.54) | 0.001 |

| Cardiometabolic multimorbidity | ||||

| No | 595 (41.0%) | 21 (3.5%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 847 (58.4%) | 71 (8.4%) | 2.47 (1.43–4.26) | 0.001 |

| Cardiometabolic multimorbidity category | ||||

| 0–1 | 595 (41.0%) | 21 (3.5%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 2 | 402 (27.7%) | 27 (6.7%) | 2.06 (1.10–3.86) | 0.024 |

| 3 | 248 (17.1%) | 22 (8.9%) | 2.49 (1.26–4.91) | 0.009 |

| ≥ 4 | 197 (13.6%) | 22 (11.2%) | 3.34 (1.69–6.62) | 0.001 |

| Panvascular multimorbidityb | ||||

| Number of panvascular diseases | 0.97 ± 0.8 | – | 2.32 (1.72–3.15) | < 0.001 |

| Panvascular multimorbidity | ||||

| No | 1016 (70.1%) | 40 (3.9%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 280 (19.3%) | 36 (12.9%) | 3.85 (2.29–6.47) | < 0.001 |

| Panvascular multimorbidity category | ||||

| 0–1 | 1016 (70.1%) | 40 (3.9%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 2 | 224 (17.3%) | 23 (10.3%) | 2.72 (1.50–4.93) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 3 | 56 (4.3%) | 13 (23.2%) | 9.05 (4.21–19.42) | < 0.001 |

| Multimorbidityc | ||||

| Number of chronic diseases | 2.60 ± 1.48 | – | 1.47 (1.25–1.73) | < 0.001 |

| Multimorbidity | ||||

| No | 308 (21.2%) | 6 (1.9%) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 983 (67.8%) | 70 (7.1%) | 2.67 (1.12–6.34) | 0.026 |

| Multimorbidity category | ||||

| 0–1 | 308 (21.2%) | 6 (1.9%) | 1.00 (reference) | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 361 (24.9%) | 10 (2.8%) | 0.82 (0.27–2.50) | 0.724 |

| 3 | 305 (21.0%) | 23 (7.5%) | 3.00 (1.17–7.68) | 0.022 |

| 4 | 177 (12.2%) | 19 (10.7%) | 3.86 (1.44–10.35) | 0.007 |

| ≥ 5 | 140 (9.7%) | 18 (12.9%) | 5.62 (2.05–14.58) | 0.001 |

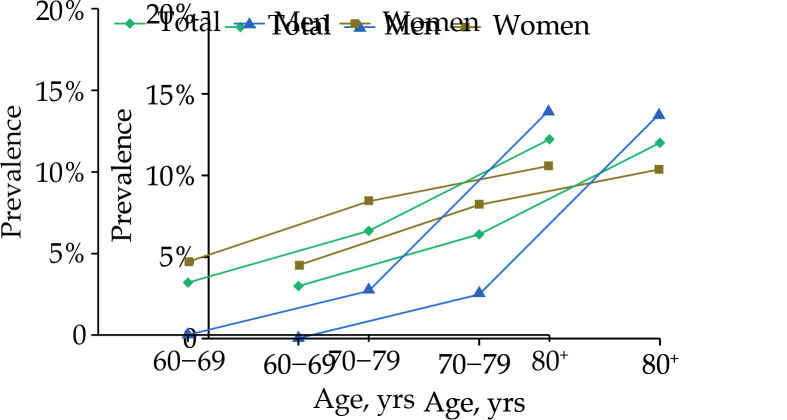

The overall prevalence of MCR was 6.3% (92/1450). Figure 1 presents the age- and sex-specific prevalences of MCR. The prevalence of MCR increased with advancing age, from 3.2% in people aged 60–69 years and 6.4% in those aged 70–79 years to 12.0% in those aged 80+ years (χ2 = 19.55, P < 0.001). The prevalence of MCR in women aged 60–69 years and 70–79 years was higher than that in men (χ2 = 5.59, P = 0.018 and χ2 = 8.92, P = 0.003), but there was no sex difference among participants aged 80 years and above.

Figure 1.

Age- and sex-specific prevalence of motoric cognitive risk syndrome among Chinese older adults.

Association of Cardiometabolic and Panvascular Diseases with MCR

The presence of cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or increased serum cystatin C was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of MCR (multivariable-adjusted OR range: 1.90–3.02, P < 0.05 for all) (Table 2). Other individual chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity showed non-significant associations with MCR.

With regard to multimorbidity measures, the increasing number of cardiometabolic diseases and panvascular diseases was consistently associated with increased likelihoods of MCR, with the multivariable-adjusted OR being 1.31 and 2.32, respectively (all P < 0.001). In addition, compared to participants who did not have multimorbidity, those with cardiometabolic multimorbidity (OR = 2.47, 95% CI: 1.43–4.26) or panvascular multimorbidity (OR = 3.85, 95% CI: 2.29–6.47) had a higher likelihood of MCR. Participants having two, three, and four or more cardiometabolic diseases were 2.06, 2.49, and 3.34 times more likely to have MCR, respectively, relative to those having no multimorbidity (< 2 chronic diseases). Similarly, having two and three or more panvascular diseases were associated with 2.72- and 9.05-fold increased likelihoods of MCR, respectively (Table 3).

Association of Overall Multimorbidity with MCR

The increasing number of examined chronic diseases was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of MCR (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.25–1.73). Participants who had multimorbidity were more likely to have MCR compared to those without multimorbidity (OR = 2.67, 95% CI: 1.12–6.32). Compared with having no multimorbidity (i.e., < 2 chronic diseases), concurrently having three, four, and five or more chronic diseases was associated with 3.00-, 3.86-, and 5.62-fold increased likelihoods of MCR, respectively (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population-based study among Chinese older adults that investigates the relationship of cardiometabolic multimorbidity and panvascular multimorbidity simultaneously with MCR. In this study, we found an overall prevalences of 6.3% of MCR among older Chinese adults living in a rural community, and the prevalence increased with advanced age. Cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and increased serum cystatin C were associated with a higher likelihood of MCR. Furthermore, the increasing number and the presence of multimorbidity of cardiometabolic diseases and panvascular diseases showed consistent associations with a 1.3- to 3.8-fold increased likelihood of MCR.

The prevalence of MCR in our sample is comparable to the pooled rate of 9.7% (ranging from 2% to 16%) reported in a meta-analysis of 22 studies among older adults aged ≥ 60 years and studies of Chinese older adults (prevalence range: 4%–12.7%).[28–30] Variation in the prevalence may be resulted from differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of the study populations, the study settings, and the methods used to define the slow gait. Higher prevalence of MCR was found in young-old females compared to males, but such sex difference was not observed in old-old adults. The previous meta-analysis found no sex difference in the prevalence of MCR,[30] while another study in Chinese older adults found that women had higher prevalence of MCR than men.[26] Our finding implies that women may experience earlier onset of cognitive decline, but this sex difference may diminish with advanced age. Using the age- and sex-appropriate value to define slow gait speed may also attenuate the sex difference in the prevalence of MCR. In addition, we found higher prevalence of MCR among individuals who were older, single/widowed/divorced, less educated, and physically inactive, consistent with the literature on cognitive function.[6,31] This reinforces the view that greater attention should be paid to disadvantaged older adults with lower socioeconomic status to prevent cognitive decline.

We found that cardiometabolic diseases were common among Chinese older adults. Cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure were associated with a higher likelihood of MCR, which is in line with the reports from previous studies.[25,26] Cerebrovascular damage and disruption of vascular function and cerebral small vessel disease have been well established to be associated with cognitive impairment. In addition, of the individual panvascular diseases, increased serum cystatin C was associated with an increased likelihood of MCR. Our study suggests that serum cystatin C may be a biomarker of the pre-dementia syndrome. High levels of serum cystatin C may directly affect the process of vascular wall remodeling by regulating the balance of proteolytic and antiproteolytic activities.[32] Impaired kidney function assessed with the creatinine- or cystatin C-based estimated glomerular filtration rate has been associated with cognitive impairments.[33,34] The non-significant associations of other panvascular components, such as carotid artery disease and subclavian stenosi, with MCR may be due partly to limited statistical power because of relatively low the prevalence of these condition (< 5%) and the MCR outcome (6.3%). The findings provide preliminary evidence that more severe panvascular diseases affecting the heart, brain, and kidney may have stronger association with the pre-dementia syndrome than peripheral artery diseases.

Furthermore, our findings highlight the potential adverse cognitive consequences of multimorbidity in older adults. Although some of the individual cardiometabolic and panvascular diseases were not independently associated with MCR, the aggregation of multiple cardiometabolic and panvascular diseases showed strong and consistent associations with MCR. Notably, the likelihood of having MCR was increased with a greater number of chronic diseases, suggesting a dose-response relationship. The strong associations of MCR with cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity in older adults highlight the potential involvement of cardiovascular and metabolic pathways in early prodromal stages of cognitive impairment and dementia. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to explore the temporal causal relationship between these vascular diseases and MCR as well as the potential pathological mechanisms involving inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular function.[3]

LIMITATIONS

In this population-based study, we defined a range of cardiometabolic and panvascular diseases by integrating information from face-to-face interviews, clinical examinations, and instrumental and laboratory test. However, our study also has limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the study design did not allow us to make any causal inferences on any of the observed associations between chronic health conditions and MCR, and the study findings of cross-sectional associations might be subject to survival bias. Future prospective cohort studies are warranted to further elucidate the determinants and critical prognostic outcomes (e.g., mortality and hospitalization) of MCR, which could provide insights for the development of targeted preventive intervention strategies. Secondly, some chronic diseases were ascertained only based on self-reported information, which might underestimate their prevalence. Thirdly, the duration and severity of the diseases were not taken into consideration when we analyzed the associations between chronic diseases and MCR. Fourthly, we did not have data to assess frailty, a clinical syndrome common in older people characterized by progressive multisystem decline, reduced physiological reserve, and heightened vulnerability to adverse health outcomes (e.g., cognitive impairments), which might have confounded the observed associations between MCR and multimorbidity. Last but not least, our study sample was derived from only one rural area, which should be kept in mind when generalizing the findings to other populations.

The findings from our study have potential implications for clinical practice in the detection and management of MCR as well as for preventive interventions. Given the increased likelihood of MCR among older adults with cardiometabolic or panvascular multimorbidity, healthcare providers may integrate the MCR screening procedure into routine care for older adult with multimorbidity to enhance early detection and preventive care. Furthermore, older adults with cardiometabolic or panvascular multimorbidity might be targeted for early preventive interventions (e.g., lifestyle modifications and regular cognitive and physical function monitoring) to delay the progression from MCR to dementia.

CONCLUSIONS

This population-based study provides important data on the prevalence of MCR and the relationships of cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity with MCR in community-dwelling Chinese older adults. Our findings demonstrated that both cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidities were strongly associated with MCR. These findings have implications for prevention of the prodromal dementia syndrome and screening of at-risk individuals with cardiometabolic and panvascular multimorbidity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Department of Science and Technology (No.2008GG30002058), the Department of Health (No.2009-067), the Department of Natural Science Foundation (ZR2010HL031) in Shandong, China, the Swedish Research Council (No.2017-00740 & No.2017-05819), and the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (CH2019-8320), Stockholm, Sweden. All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their contribution to the Confucius Hometown Aging Project as well as local medical staff at Xing Long Zhuang Hospital for their collaboration in data collection.

Contributor Information

Rui SHE, Email: sherry-rui.she@polyu.edu.hk.

Cheng-Xuan QIU, Email: chengxuan.qiu@ki.se.

References

- 1.George CJ, Verghese J Motoric cognitive risk syndrome in polypharmacy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1072–1077. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marquez I, Garcia-Cifuentes E, Velandia FR, et al Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: prevalence and cognitive performance. A cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;8:100162. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos CY, Snyder PJ, Wu WC, et al Pathophysiologic relationship between Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular risk: a review and synthesis. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017;7:69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Liu R, Tian N, et al Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, peripheral biomarkers, and dementia in rural older adults: the MIND-China study. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20(9):6133–6145. doi: 10.1002/alz.14091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iqbal K, Hasanain M, Ahmed J, et al Association of motoric cognitive risk syndrome with cardiovascular and noncardiovascular factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23:810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Y, Liang J, Hong C, et al Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, lifestyle behaviours, and cognitive function: a multicohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4:e265–e273. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Angelantonio E, Kaptoge S, Wormser D, et al Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality. JAMA. 2015;314:52–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou X, Yu L, Zhao Y, et al Panvascular medicine: an emerging discipline focusing on atherosclerotic diseases. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4528–4531. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Y, Fülöp T, Gwee X, et al Cardiometabolic and vascular disease factors and mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Gerontology. 2022;68:1061–1069. doi: 10.1159/000521547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang Y, Johnell K, Yan Z, et al Use of medications and functional dependence among Chinese older adults in a rural community: a population-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:1242–1248. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.She R, Yan Z, Jiang H, et al Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life in old age: role of functional dependence and depressive symptoms. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song A, Liang Y, Yan Z, et al Highly prevalent and poorly controlled cardiovascular risk factors among Chinese elderly people living in the rural community. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:1267–1274. doi: 10.1177/2047487313487621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang R, Yan Z, Liang Y, et al Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease pairs and multimorbidity among older Chinese adults living in a rural area. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakubowski KP, Cundiff JM, Matthews KA Cumulative childhood adversity and adult cardiometabolic disease: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37:701–715. doi: 10.1037/hea0000637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S81–S90. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calderón-Larrañaga A, Vetrano DL, Onder G, et al Assessing and measuring chronic multimorbidity in the older population: a proposal for its operationalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1417–1423. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villa P, Jiménez M, Soriano MC, et al Serum cystatin C concentration as a marker of acute renal dysfunction in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2005;9:R139–R143. doi: 10.1186/cc3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Yan Z, Jiang H, et al Serum cystatin C, impaired kidney function, and geriatric depressive symptoms among older people living in a rural area: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:265. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0957-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doganer YC, Aydogan U, Aydogdu A, et al Relationship of cystatin C with coronary artery disease and its severity. Coron Artery Dis. 2013;24:119–126. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32835b6761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arpegård J, Ostergren J, de Faire U, et al. Cystatin C--a marker of peripheral atherosclerotic disease? Atherosclerosis 2008; 199: 397–401.

- 21.Liang Y, Yan Z, Sun B, et al Cardiovascular risk factor profiles for peripheral artery disease and carotid atherosclerosis among Chinese older people: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, et al 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO), The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:763–816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, et al Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:905–914. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61710-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, et al Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and the risk of dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:412–418. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beauchet O, Sekhon H, Launay CP, et al Relationship between motoric cognitive risk syndrome, cardiovascular risk factors and diseases, and incident cognitive impairment: results from the ”NuAge” study. Maturitas. 2020;138:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan JL, Zhao RX, Ma YJ, et al Prevalence/potential risk factors for motoric cognitive risk and its relationship to falls in the elderly Chinese people: cross-sectional study. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:2680–2687. doi: 10.1111/ene.14884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Feng BL, Wang CY, et al Prevalence and factors associated with motoric cognitive risk syndrome in community-dwelling older Chinese: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1137–1145. doi: 10.1111/ene.14266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen S, Zeng X, Xu L, et al Association between motoric cognitive risk syndromes and frailty among older Chinese adults. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:110. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01511-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verghese J, Annweiler C, Ayers E, et al Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: multicountry prevalence and dementia risk. Neurology. 2014;83:718–726. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang H, Fang Y Association of polypharmacy and motoric cognitive risk syndrome in older adult: a 4-year longitudinal study in China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;106:104896. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2022.104896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni L, Lü J, Hou LB, et al Cystatin C, associated with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, is strong predictor of the risk of cardiovascular events and death in Chinese. Stroke. 2007;38:3287–3288. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurella Tamura M, Wadley V, Yaffe K, et al Kidney function and cognitive impairment in US adults: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:227–234. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Z, Yan Z, Liang Y, et al Interactive effects of diabetes and impaired kidney function on cognitive performance in old age: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0193-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]