Abstract

We analysed trends in new HIV diagnoses and factors contributing to late diagnosis among migrants in countries in the European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA) from 2014 to 2023. Of the total reported HIV diagnoses, 45.9% were in migrants, with 13.3% born in EU/EEA countries and 86.7% in non-EU/EEA countries. Late diagnosis was observed in 52.4% of migrants, particularly among non-EU/EEA migrants with heterosexual transmission, regardless of sex. Improved HIV prevention and testing strategies are essential for at-risk migrant populations.

Keywords: HIV infections, epidemiology, population surveillance, migrants, Healthcare, Delayed Diagnosis

Migrants, defined as people born outside of the country in which they reside, are a key population affected by HIV in European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA) countries. In 2023, migrants accounted for 47.9% (11,837/24,731) of all HIV diagnoses in the EU/EEA [1].

Migrants are a diverse group, with various drivers of migration and various HIV risk factors. As the HIV epidemic evolves, public health strategies must adapt to shifting epidemiological trends, refining approaches to prevention, testing, and treatment to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals set for 2030. To guide these programmes, we aimed to assess trends in new HIV diagnoses among migrants in EU/EEA countries from 2014 to 2023, focusing on sociodemographic factors associated with late diagnosis.

HIV diagnoses among migrants in EU/EEA countries

Between 2014 and 2023, a total of 247,733 HIV diagnoses were reported by 30 EU/EEA countries to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control through the European Surveillance System. For this analysis, we only included new HIV diagnoses, leading to the exclusion of 99,909 cases from 12 countries unable to classify diagnoses as either new or previously positive. Consequently, we also excluded all previously positive diagnoses (n = 24,498) reported by the remaining 19 countries, leaving a total of 123,326 new HIV diagnoses which could be analysed.

We established two categories related to region. The first, ‘region of origin’ defines migrants’ birth region. Region of origin was categorised based on UNAIDS designation and divided into non-EU/EEA and EU/EEA countries. The second category, ‘EU/EEA subregions’, defines sub-regions for the reporting countries within the EU/EEA. A list of countries by region is appended in the Supplement.

Among the diagnosed people with known region of origin (n = 103,416, or 83.9% of the study sample), 45.9% (n = 47,473) were migrants, i.e. born outside of the EU/EEA country where they were diagnosed. Characteristics of these cases are presented in Table 1 and, for purposes of comparison, cases among non-migrants are also presented. Among migrants in this study sample, 13.3% (n = 6,337) were born in another EU/EEA country and 86.7% (n = 41,136) in non-EU/EEA countries. By region, 44.7% (n = 21,232) were born in Sub-Saharan Africa, 13.9% (n = 6,601) in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 11.2% (n = 5,335) in eastern Europe, with smaller proportions in central Europe, western Europe, South/South-East Asia and other regions. The western EU/EEA subregion reported 81.0% (n = 5,133) of migrants originating from other EU/EEA countries and 72.9% (n = 29,995) of migrants originating from non-EU/EEA countries (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of migrant and non-migrant populations diagnosed with HIV, EU/EEA, 2014–2023 (n = 123,326) .

| Cases with known region of origin | Region of origin of migrant cases | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Non-migrants | Migrants born in the EU/EEA | Migrants born outside of the EU/EEA | Western Europe | Central Europe | Eastern Europe | Sub-Saharan Africa | Latin America and Caribbean | South and South-east Asia | Other | Unknown | |||||||||||||

| Number | 103,416 | 55,943 | 6,337 | 41,136 | 3,460 | 4,707 | 5,335 | 21,232 | 6,601 | 3,119 | 3,019 | 19,910 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Women | 25,751 | 24.9 | 7,751 | 13.9 | 1,026 | 16.2 | 16,974 | 41.3 | 391 | 11.3 | 812 | 17.3 | 2,176 | 40.8 | 12,230 | 57.6 | 1,095 | 16.6 | 833 | 26.7 | 463 | 15.3 | 6,838 | 34.3 |

| Men | 76,921 | 74.4 | 48,023 | 85.8 | 5,280 | 83.3 | 23,618 | 57.4 | 3,058 | 88.4 | 3,863 | 82.1 | 3,140 | 58.9 | 8,940 | 42.1 | 5,117 | 77.5 | 2,250 | 72.1 | 2,530 | 83.8 | 13,012 | 65.4 |

| Transgender | 713 | 0.7 | 164 | 0.3 | 31 | 0.5 | 518 | 1.3 | 11 | 0.3 | 32 | 0.7 | 14 | 0.3 | 50 | 0.2 | 383 | 5.8 | 34 | 1.1 | 25 | 0.8 | 25 | 0.1 |

| Unknown | 31 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.1 | 12 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 35 | 0.2 |

| Male:female ratioa | 3 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 1.9 | ||||||||||||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 37 (29–47) | 39 (30–50) | 35 (28–44) | 35 (28–43) | 39 (30–48) | 34 (28–42) | 38 (32–44) | 35 (28–43) | 32 (27–39) | 34 (28–42) | 35 (28–44) | 39 (30–49) | ||||||||||||

| Age group in years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤ 18 | 1,797 | 1.7 | 617 | 1.1 | 59 | 0.9 | 1,121 | 2.7 | 23 | 0.7 | 42 | 0.9 | 140 | 2.6 | 824 | 3.9 | 52 | 0.8 | 38 | 1.2 | 61 | 2 | 444 | 2.2 |

| 19–29 | 26,278 | 25.4 | 13,286 | 23.7 | 1,784 | 28.2 | 11,208 | 27.2 | 819 | 23.7 | 1,421 | 30.2 | 837 | 15.7 | 5,521 | 26 | 2,588 | 39.2 | 925 | 29.7 | 881 | 29.2 | 3,992 | 20.1 |

| 30–50 | 56,299 | 54.4 | 28,691 | 51.3 | 3,710 | 58.5 | 23,898 | 58.1 | 1,933 | 55.9 | 2,762 | 58.7 | 3,782 | 70.9 | 12,166 | 57.3 | 3,445 | 52.2 | 1,859 | 59.6 | 1,661 | 55 | 11,070 | 55.6 |

| > 50 | 18,929 | 18.3 | 13,286 | 23.7 | 774 | 12.2 | 4,869 | 11.8 | 679 | 19.6 | 473 | 10 | 567 | 0.6 | 2,709 | 12.8 | 512 | 7.8 | 290 | 9.3 | 413 | 13.7 | 4,324 | 21.7 |

| Unknown | 113 | 0.1 | 63 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.2 | 40 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.2 | 9 | 0.2 | 12 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.1 | 7 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.1 | 80 | 0.4 |

| Mode of transmission | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex between men | 45,739 | 44.2 | 31,867 | 57 | 3,348 | 52.8 | 10,524 | 25.6 | 2,168 | 62.7 | 2,234 | 47.5 | 844 | 15.8 | 1,727 | 8.1 | 4,042 | 61.2 | 1,456 | 46.7 | 1,401 | 46.4 | 1,777 | 8.9 |

| Heterosexual transmission (men) | 17,606 | 17 | 8,239 | 14.7 | 736 | 11.6 | 8,631 | 21 | 444 | 12.8 | 558 | 11.9 | 804 | 15.1 | 5,959 | 28.1 | 759 | 11.5 | 283 | 9.1 | 560 | 18.5 | 918 | 4.6 |

| Heterosexual transmission (women) | 21,483 | 20.8 | 5,974 | 10.7 | 745 | 11.8 | 14,764 | 35.9 | 288 | 8.3 | 591 | 12.6 | 1,631 | 30.6 | 10,951 | 51.6 | 987 | 15 | 713 | 22.9 | 348 | 11.5 | 1,145 | 5.8 |

| Injecting drug use | 4,588 | 4.4 | 2,776 | 5 | 509 | 8 | 1,303 | 3.2 | 134 | 3.9 | 356 | 7.6 | 985 | 18.5 | 67 | 0.3 | 38 | 0.6 | 131 | 4.2 | 101 | 3.3 | 460 | 2.3 |

| Mother to child transmission | 615 | 0.6 | 141 | 0.3 | 27 | 0.4 | 447 | 1.1 | 14 | 0.4 | 12 | 0.3 | 105 | 2 | 294 | 1.4 | 9 | 0.1 | 17 | 0.5 | 23 | 0.8 | 42 | 0.2 |

| Other routes | 217 | 0.2 | 34 | 0.1 | 15 | 0.2 | 168 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.2 | 13 | 0.3 | 29 | 0.5 | 106 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.1 | 13 | 0.4 | 10 | 0.3 | 5 | 0 |

| Unknown | 13,168 | 12.7 | 6,912 | 12.4 | 957 | 15.1 | 5,299 | 12.9 | 406 | 11.7 | 943 | 20 | 937 | 17.6 | 2,128 | 10 | 760 | 11.5 | 506 | 16.2 | 576 | 19.1 | 15,563 | 78.2 |

| Median CD4+ T-cell count/μL (IQR) | 350 (164–544) |

372 (176–564) |

378 (183–579) |

316 (150–507) |

386 (204–589) |

360 (147–558) |

355 (126–581) |

294 (143–473) |

363 (199–546) |

268 (93–454) |

357 (175–544) |

310 (118–530) |

||||||||||||

| CD4+ category at HIV diagnosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| < 200 CD4+ T-cell count/μL | 21,073 | 20.4 | 10,770 | 19.3 | 1,134 | 17.9 | 9,169 | 22.3 | 600 | 17.3 | 917 | 19.5 | 938 | 17.6 | 5,205 | 24.5 | 1,251 | 19 | 781 | 25 | 611 | 20.2 | 835 | 4.2 |

| 200 to < 350 CD4+ T-cell count/μL | 14,909 | 14.4 | 7,558 | 13.5 | 808 | 12.8 | 6,543 | 15.9 | 491 | 14.2 | 545 | 11.6 | 520 | 9.7 | 3,742 | 17.6 | 1,128 | 17.1 | 467 | 15 | 458 | 15.2 | 471 | 2.4 |

| 350 to < 500 CD4+ T-cell count/μL | 14,590 | 14.1 | 8,252 | 14.8 | 868 | 13.7 | 5,470 | 13.3 | 496 | 14.3 | 599 | 12.7 | 492 | 9.2 | 2,882 | 13.6 | 1,082 | 16.4 | 344 | 11 | 443 | 14.7 | 412 | 2.1 |

| ≥ 500 CD4+ T-cell count/μL | 21,639 | 20.9 | 12,792 | 22.9 | 1,430 | 22.6 | 7,417 | 18 | 883 | 25.5 | 957 | 20.3 | 990 | 18.6 | 3,444 | 16.2 | 1,510 | 22.9 | 398 | 12.8 | 665 | 22 | 672 | 3.4 |

| Unknown | 31,205 | 30.2 | 16,571 | 29.6 | 2,097 | 33.1 | 12,537 | 30.5 | 990 | 28.6 | 1,689 | 35.9 | 2,395 | 44.9 | 5,959 | 28.1 | 1,630 | 24.7 | 1,129 | 36.2 | 842 | 27.9 | 17,520 | 88 |

| AIDS at HIV diagnosis | 14,092 | 13.6 | 7,893 | 14.1 | 843 | 13.3 | 5,356 | 13 | 405 | 11.7 | 704 | 15 | 766 | 14.4 | 2,762 | 13 | 649 | 9.8 | 536 | 17.2 | 377 | 12.5 | 679 | 3.4 |

| Reporting EU/EEA subregion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern EU/EEA subregion | 5,930 | 5.7 | 4,951 | 8.9 | 240 | 3.8 | 739 | 1.8 | 35 | 1 | 198 | 4.2 | 618 | 11.6 | 20 | 0.1 | 37 | 0.6 | 50 | 1.6 | 21 | 0.7 | 1,926 | 9.7 |

| Southern EU/EEA subregion | 17,614 | 17 | 11,002 | 19.7 | 391 | 6.2 | 6,221 | 15.1 | 451 | 13 | 583 | 12.4 | 509 | 9.5 | 3,031 | 14.3 | 1,617 | 24.5 | 266 | 8.5 | 155 | 5.1 | 1,318 | 6.6 |

| Western EU/EEA suubregion | 72,220 | 69.8 | 37,092 | 66.3 | 5,133 | 81 | 29,995 | 72.9 | 2,621 | 75.8 | 3,547 | 75.4 | 3,746 | 70.2 | 16,223 | 76.4 | 4,319 | 65.4 | 2,114 | 67.8 | 2,558 | 84.7 | 15,739 | 79.1 |

| Northern EU/EEA subregion | 7,652 | 7.4 | 2,898 | 5.2 | 573 | 9 | 4,181 | 10.2 | 353 | 10.2 | 379 | 8.1 | 462 | 8.7 | 1,958 | 9.2 | 628 | 9.5 | 689 | 22.1 | 285 | 9.4 | 927 | 4.7 |

EEA: European Economic Area; EU: European Union; IQR: interquartile range.

a Male-to-female ratio indicates the proportion of male to female in the population, expressed as a ratio.

For this analysis, the primary exposure variable, geographical origin, was determined using information on country of birth, nationality and/or region of origin. When multiple variables were available, priority was given in the following order: country of birth, nationality and then region of origin. Geographical origin was classified as non-migrant if the reporting country matched the country of birth or nationality. The non-migrant population was defined as people whose reported place of birth was the reporting country. Two regional categories were established: ‘region of origin’, based on UNAIDS designation and divided into non-EU/EEA and EU/EEA countries to define migrants' birth regions, and ‘EU/EEA subregions' representing reporting countries within the EU/EEA as listed in the appended Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Countries excluded from the analysis were: Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Spain because they were unable to classify diagnoses as either new or previously positive.

For those where the respective information was known, migrants born in EU/EEA countries were predominantly men (83.3%; n = 5,280), aged 30–50 years (58.5%: n = 3,710) and with sex between men as the primary mode of transmission (52.8%; n = 3,338). Among migrants from non-EU/EEA countries there was a higher proportion of women (41.3%; n = 16,974), with most aged 30–50 years (58.1%; n = 23,898) and heterosexual sex was the most common mode of transmission (56.9%; n = 23,395) (Table 1). Overall, migrant women tended to be slightly younger than migrant men and were most likely to acquire HIV through heterosexual transmission (83.4%), while sex between men remains the leading mode of transmission for men (59.3%). We conducted a descriptive analysis by gender, which is appended in Supplementary Table S3.

HIV diagnosis trends among migrant populations in EU/EEA countries

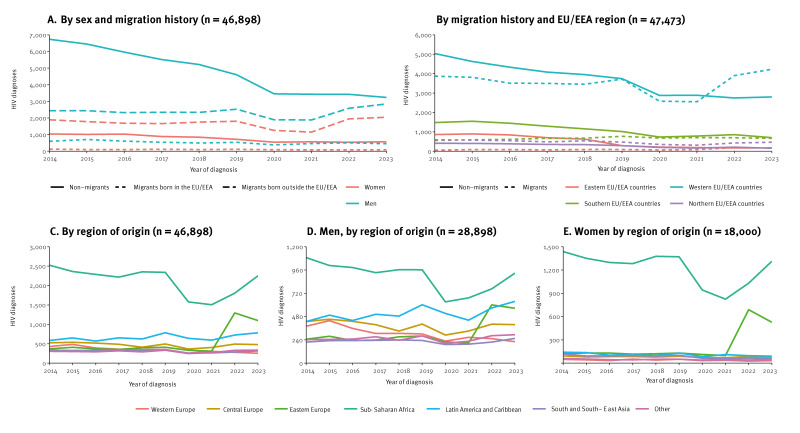

The HIV diagnosis trends among migrant populations are presented in the Figure. For purposes of comparison, we also present data for non-migrants. Between 2014 and 2023, HIV diagnoses reported by EU/EEA countries in migrants originating from non-EU/EEA countries increased by 14.4%, while diagnoses in people originating from another EU/EEA country decreased by 24.6%. The increase in new HIV diagnoses among migrants from non-EU/EEA countries was greater in men (16.7%) than in women (8.1%) (Figure, panel A). The largest rise in reporting of new HIV diagnoses among migrants was seen from 2021 to 2023 in the western EU/EEA subregion (32.1%; from 6,456 to 8,531 diagnoses) followed by the northern (29.0%, from 610 to 787) and eastern (7.5%, from 591 to 635 diagnoses) subregions (Figure, panel B). Since 2014, reported HIV diagnoses among migrants from different regions of origin have shown distinct trends (Figure, panel C). In men from Sub-Saharan Africa, there was a steady decline from 2014 to 2019, a sharp drop in 2020, probably due to the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by an increase in 2021 (Figure, panel D). The pattern in women was similar but with a sharper increase beginning in 2022, rising by 59.2% from 2021 to 2023 (Figure, panel E). For people from eastern Europe, diagnoses rose in 2022 for both men and women, probably due to the conflict in Ukraine [2]. Diagnoses in men from Latin America and the Caribbean increased from 2014 to 2019, declined until 2021, followed by an increase by 43.8% through 2023 (Figure, panel D).

Figure.

HIV diagnosis trends among migrant and non-migrant populations, EU/EEA, 2014–2023

EEA: European Economic Area; EU: European Union.

Geographical origin was classified as non-migrant if the reporting country matched the country of birth or nationality. The non-migrant population was defined as people whose reported place of birth was the reporting country. Two regional categories were established: ‘region of origin’, based on UNAIDS designation and divided into non-EU/EEA and EU/EEA countries to define migrants' birth regions, and ‘EU/EEA subregions' representing reporting countries within the EU/EEA as listed in the appended Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Countries excluded from the analysis were: Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Spain because they were unable to classify diagnoses as either new or previously positive.

Late diagnosis

Late diagnosis is defined as an HIV diagnosis with a CD4+ T-cell count below 350 cells/μL or an AIDS-defining event; cases diagnosed during the acute stage are not classified as late, even when the individual has a low CD4+ T-cell count [3]. The percentage of late HIV diagnoses was 52.4% among all migrants, 43.1% in EU/EEA-born migrants and 53.8% in non-EU/EEA migrants. In comparison, the percentage of late HIV diagnoses among non-migrants was 42.6%. The EU/EEA-born migrants diagnosed late were predominantly men (82.6%; n = 1,394). The main transmission mode in this group was sex between men (50.5%; n = 852). Late diagnoses in EU/EEA-born migrants were reported primarily by western EU/EEA countries (72.8%; n = 1,229). For non-EU/EEA-born migrants, late diagnoses were more balanced between men (56.2%; n = 7,944) and women (43.8%; n = 6,182), with a median age of 37 years (range: 30–45). Heterosexual transmission was the dominant mode of transmission, responsible for 54.4% (n = 10,355) of those diagnosed late. Late diagnoses among non-EU/EEA-born cases were also mostly reported by western EU/EEA countries (69.3%; n = 9,788) (Table 2).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of migrant and non-migrant populations with late and non-late HIV diagnoses and mode of transmission, EU/EEA, 2014–2023 (n = 67,677).

| Non-late diagnosis among non-migrants | Late diagnosis among non-migrants | Non-late diagnosis among migrants born in EU/EEA | Late diagnosis among migrants born in EU/EEA | Non-late diagnosis among migrants born outside the EU/EEA | Late diagnosis among migrants born outside the EU/EEA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 21,510 | 15,985 | 2,225 | 1,688 | 12,143 | 14,126 | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Women | 2,720 | 12.6 | 2,340 | 14.6 | 256 | 11.5 | 294 | 17.4 | 4,754 | 39.2 | 6,182 | 43.8 |

| Men | 18,790 | 87.4 | 13,645 | 85.4 | 1,969 | 88.5 | 1,394 | 82.6 | 7,389 | 60.8 | 7,944 | 56.2 |

| Male:female ratioa | 6.9 | 5.8 | 7.7 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | ||||||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 35 (27–46) | 44 (34–54) | 33 (27–41) | 38 (31–47) | 33 (27–41) | 37 (30–45) | ||||||

| Age group in years | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 18 | 281 | 1.3 | 50 | 0.3 | 22 | 1.0 | 5 | 0.3 | 237 | 2.0 | 188 | 1.3 |

| 19–29 | 6,908 | 32.1 | 2,321 | 14.5 | 768 | 34.5 | 346 | 20.5 | 4,074 | 33.6 | 3,085 | 21.8 |

| 30–50 | 10,862 | 50.5 | 8,414 | 52.6 | 1,235 | 55.5 | 1,055 | 62.5 | 6,679 | 55.0 | 8,742 | 61.9 |

| > 50 | 3,459 | 16.1 | 5,200 | 32.5 | 200 | 9.0 | 282 | 16.7 | 1,153 | 9.5 | 2,111 | 14.9 |

| Mode of transmission | ||||||||||||

| Sex between men | 15,299 | 71.1 | 8,770 | 54.9 | 1,615 | 72.6 | 852 | 50.5 | 4,718 | 38.9 | 3,177 | 22.5 |

| Heterosexual transmission (men) | 2,817 | 13.1 | 4,146 | 25.9 | 236 | 10.6 | 392 | 23.2 | 2,388 | 19.7 | 4,315 | 30.5 |

| Heterosexual transmission (women) | 2,467 | 11.5 | 2,165 | 13.5 | 228 | 10.2 | 274 | 16.2 | 4,641 | 38.2 | 6,040 | 42.8 |

| Injecting drug use | 911 | 4.2 | 883 | 5.5 | 142 | 6.4 | 157 | 9.3 | 306 | 2.5 | 454 | 3.2 |

| Mother to child transmission | 3 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 42 | 0.3 | 53 | 0.4 |

| Other routes | 13 | 0.1 | 16 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.6 | 48 | 0.4 | 87 | 0.6 |

| Median CD4+ T-cell count/μL (IQR) | 524 (414–687) | 160 (55–264) | 540 (423–703) | 175 (57–277) | 511 (409–659) | 171 (65–267) | ||||||

| CD4+ T-cell count category at HIV diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| < 200 CD4+ T-cell count/μLb | 556 | 2.6 | 8,727 | 54.6 | 54 | 2.4 | 889 | 52.7 | 320 | 2.6 | 7,678 | 54.4 |

| 200 to < 350 CD4+ T-cell count/μLb | 1,370 | 6.4 | 5,660 | 35.4 | 117 | 5.3 | 627 | 37.1 | 608 | 5.0 | 5,340 | 37.8 |

| 350 to < 500 CD4+ T-cell count/μL | 7,631 | 35.5 | 195 | 1.2 | 764 | 34.3 | 36 | 2.1 | 4,784 | 39.4 | 206 | 1.5 |

| ≥ 500 CD4+ T-cell count/μL | 11,927 | 55.4 | 283 | 1.8 | 1,282 | 57.6 | 46 | 2.7 | 6,423 | 52.9 | 195 | 1.4 |

| Unknown | 26 | 0.1 | 1,120 | 7.0 | 8 | 0.4 | 90 | 5.3 | 8 | 0.1 | 707 | 5.0 |

| AIDS at HIV diagnosis | 132 | 0.6 | 6,160 | 38.5 | 17 | 0.8 | 625 | 37.0 | 58 | 0.5 | 4,489 | 31.8 |

| Reporting EU/EEA region | ||||||||||||

| Eastern EU/EEA countries | 1,612 | 7.5 | 1,444 | 9.0 | 128 | 5.8 | 65 | 3.9 | 202 | 1.7 | 245 | 1.7 |

| Southern EU/EEA countries | 4,265 | 19.8 | 4,776 | 29.9 | 139 | 6.2 | 197 | 11.7 | 1,982 | 16.3 | 2,724 | 19.3 |

| Western EU/EEA countries | 14,602 | 67.9 | 8,829 | 55.2 | 1,749 | 78.6 | 1,229 | 72.8 | 8,941 | 73.6 | 9,788 | 69.3 |

| Northern EU/EEA countries | 1,031 | 4.8 | 936 | 5.9 | 209 | 9.4 | 197 | 11.7 | 1,018 | 8.4 | 1,369 | 9.7 |

EEA: European Economic Area; EU: European Union; IQR: interquartile range.

a Male-to-female ratio indicates the proportion of male to female in the population, expressed as a ratio.

b CD4+ T-cell cell count < 350 cells/μL among people with non-late diagnoses is likely to indicate diagnosis during the acute phase of HIV infection. Acute HIV infection was defined as a primary HIV infection in the initial stage following HIV acquisition, marked by high levels of HIV RNA or p24 antigen in the blood before detectable antibodies developed. This phase typically occurs 2–4 weeks after exposure and may present with low CD4+ T-cell cell count [3]. Geographical origin was classified as non-migrant if the reporting country matched the country of birth or nationality. The non-migrant population was defined as people whose reported place of birth was the reporting country. Two regional categories were established: ‘region of origin’, based on UNAIDS designation and divided into non-EU/EEA and EU/EEA countries to define migrants' birth regions, and ‘EU/EEA subregions' representing reporting countries within the EU/EEA as listed in the appended Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Countries excluded from the analyses were: Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Spain because they were unable to classify diagnoses as either new or previously positive.

Cases with gender marked as Transgender or Unknown, cases lacking age information, cases with age ≤ 15 years, cases with unknown migration status or mode of transmission and cases without AIDS diagnosis and unknown CD4+ T-cell count were excluded from this analysis.

Table 3 describes the results of a modified Poisson model [4] used to assess risk factors for late HIV diagnosis, stratified by migration from EU/EEA and non-EU/EEA countries and by sex. Predictors included age, transmission mode, reporting country and year of diagnosis (pre-COVID-19 (2014–2019) vs COVID-19/post-COVID-19 (2020–2023). Age analysis indicated that the ratio increased with age among migrant men from both EU/EEA and non-EU/EEA countries, and among women from non-EU/EEA countries. The prevalence ratio (PR) was highest among men older than 50 years born in EU/EEA countries (PR = 2.89; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.25–6.69) and non-EU/EEA countries (PR = 1.39; 95% CI: 1.18–1.64), as well as among women older 50 years born in non-EU/EEA countries (PR = 1.44; 95% CI: 1.22–1.69), compared with people aged 18 years or younger. Regionally, male migrants born in the EU/EEA diagnosed with HIV in the southern EU/EEA subregion had a significantly higher PR of late diagnosis than those in the northern subregion, while those in the western and eastern EU/EEA subregions had a significantly lower PR compared with the northern subregion (Table 3). Migrant men and women from the EU/EEA had a 6% (PR = 1.06; 95% CI: 1.02–1.10) and 25% (PR = 1.25; 95% CI: 1.15–1.36) higher PR, respectively, of late HIV diagnosis than non-migrants. This ratio was even higher for people born outside the EU/EEA, with a PR of 19% in men (PR = 1.19; 95% CI: 1.17–1.22) and 31% in women (PR = 1.31; 95% CI: 1.26–1.36) compared with non-migrants. We applied an extra-Poisson model stratified by sex to assess the PR of late diagnosis among migrants compared to the non-migrant population, as shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Table 3. Risk factors for late HIV diagnosis among EU/EEA and non-EU/EEA migrants: modified Poisson model, EU/EEA, 2014–2023 (n = 30,182).

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migrants born outside of the EU/EEA | Migrants born in the EU/EEA | Migrants born outside of the EU/EEA | Migrants born in the EU/EEA | |||||

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| Time period of diagnosisa | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID | Reference | |||||||

| Post-COVID | 1.00 | 0.97–1.03 | 1.03 | 0.95–1.11 | 0.98 | 0.94–1.01 | 0.88 | 0.75–1.05 |

| Age group in years | ||||||||

| ≤ 18 | Reference | |||||||

| 19–29 | 1.02 | 0.86–1.20 | 1.67 | 0.72–3.87 | 1.12 | 0.96–1.31 | 3.09 | 0.53–18.12 |

| 30–50 | 1.25 | 1.06–1.47 | 2.31 | 1.00–5.34 | 1.37 | 1.17–1.60 | 4.25 | 0.73–24.75 |

| > 50 | 1.39 | 1.18–1.64 | 2.89 | 1.25–6.69 | 1.44 | 1.22–1.69 | 4.54 | 0.78–26.56 |

| Reporting EU/EEA region | ||||||||

| Northern EU/EEA countries | Reference | |||||||

| Western EU/EEA countries | 0.89 | 0.85–0.94 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.97 | 0.88 | 0.83–1.92 | 0.84 | 0.67–1.06 |

| Eastern EU/EEA countries | 0.87 | 0.77–0.98 | 0.73 | 0.58–0.92 | 0.98 | 0.86–1.11 | 0.81 | 0.45–1.45 |

| Southern EU/EEA countries | 1.00 | 0.95–1.06 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.41 | 0.96 | 0.90–1.02 | 1.02 | 0.76–1.36 |

| Mode of transmission | ||||||||

| Heterosexual transmission | Reference | |||||||

| Injecting drug use | 0.93 | 0.87–0.99 | 0.91 | 0.80–1.04 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.14 | 0.78 | 0.56–1.09 |

| Sex between men | 0.66 | 0.64–0.69 | 0.61 | 0.56–0.67 | NA | |||

| Mother to child transmission | 1.29 | 1.02–1.62 | 2.74 | 2.01–3.74 | 1.02 | 0.74–1.40 | ND | |

| Other routes | 1.17 | 0.97–1.41 | 1.27 | 0.93–1.71 | 1.05 | 0.89–1.23 | ND | |

CI: confidence interval; EEA: European Economic Area; EU: European Union; NA: not applicable; ND: not determined due to low number of reported HIV diagnoses; PR: prevalence ratio.

a The years 2014–2019 are here defined as pre-COVID-19, the years 2020–2023 as post-COVID-19.

For each stratum, the model estimates report the PR, obtained by exponentiating the β coefficients from the robust Poisson model estimation, along with the corresponding 95% CIs. Countries excluded from the analyses were: Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Spain because were unable to classify diagnoses as either new or previously positive.

Discussion

Nearly half of all new HIV diagnoses reported by EU/EEA countries between 2014 and 2023 were among migrants, and this proportion increased over time. Migration flows within the EU/EEA have remained broadly stable at around 2 million per year during the past 10 years. Migration from non-EU countries has fluctuated but increased overall during the same time period [5]. Most migrants diagnosed with HIV in our study originated from non-EU/EEA countries, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and eastern Europe. Migrants from other EU/EEA countries were predominantly men, with HIV primarily transmitted through sex between men, whereas migrants from non-EU/EEA countries included a higher proportion of women, with heterosexual transmission as the most common mode of transmission.

While this study lacked data on whether migrants acquired HIV before or after migration, evidence suggests that many migrants, including those from high-prevalence regions, contract HIV after arriving to the EU/EEA [6,7]. An elevated risk of HIV acquisition among migrants, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM), has been described and is likely to reflect increased vulnerability after migration [8]. This highlights the need for comprehensive sexual health services, including condom distribution and access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for high-risk, HIV-negative MSM and migrant populations at high risk for HIV [9]. Enhancing surveillance to accurately classify migrants and record arrival dates is essential for determining whether HIV acquisition occurs before or after migration. Countries in the EU/EEA should adopt evidence-based, long-term prevention strategies that include structural, behavioural and biomedical interventions tailored to high-prevalence migrant groups and MSM.

Late HIV diagnosis is an important and escalating concern in the EU/EEA region which reached a peak of 52.7% in 2023 [1]. Our findings describe high rates of late HIV diagnosis in both migrant and non-migrant populations. Among migrants, the risk was higher in non-EU/EEA men and women older than 50 years, primarily infected through heterosexual transmission, and late diagnoses tended to be reported more frequently in the southern EU/EEA subregion. Late diagnosis leads to higher morbidity and mortality and increases the likelihood of onward HIV transmission [10]. Migrants from high-prevalence countries often arrive in host countries with advanced HIV infection and thus preventing advanced HIV infection by early diagnosis is challenging [11]. However, increased awareness among healthcare providers is vital, as late diagnosis occurs more commonly in heterosexual migrants, possibly related to misconceptions about HIV risk in heterosexuals [12].

Given the high and increasing proportion of HIV diagnoses and late diagnosis among migrants in the last year, it is essential to develop, implement and expand migrant-targeted strategies that enhance access to HIV testing and linkage to care in host countries. Barriers to HIV testing for this group include limited healthcare access, insufficient information on available services, low perceived HIV risk, unclear policies on HIV and sexual transmitted infections testing at sexual health centres and missed testing opportunities in general practice [12]. According to monitoring data on the HIV response, self-testing and community-based testing are still not universally provided to migrant populations across the EU/EEA [13] and need to be scaled up. To effectively reach this group, prevention programmes should prioritise regular, accessible HIV testing with immediate linkage to care. Scaling up testing for indicator conditions, testing in emergency department, community-based testing, reminders for clinicians, peer support to help migrants navigate the health system, and self-testing options may enhance testing uptake among migrants [14]. Several EU/EEA countries report implementation of migrant-sensitive approaches. Sharing these experiences may support countries facing similar issues.

Incorporating HIV prevention and treatment into a broader health delivery approach can reduce issues of stigma as well as financial barriers for migrants. Integrating links between HIV support and other services such as social services is often necessary to address patient needs and is particularly important for undocumented migrants where barriers to accessing services may be substantial in some EU/EEA countries [13]. To effectively reach migrant populations, inclusive research and service design of community-based, culture- and language-tailored efforts including peer-to-peer involvement are essential to increase uptake of services.

Our analysis has several limitations. Firstly, the absence of data on the time from migration to diagnosis restricts our understanding of missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in the EU/EEA. In addition, late diagnosis rates may be slightly overestimated if acute infections are misclassified as delayed diagnoses rather than recent infections. Also, relevant changes in HIV reporting systems during the study period have not been taken in consideration and might affect the results of this analysis, leading to possible biased trends in the number of HIV-positive migrants reported. It is important to note that the analysis excluded previous positive diagnoses, as this falls outside the scope of this analysis. The focus was specifically on new diagnoses to provide evidence for shaping targeted testing policies. Lastly, as 12 EU/EEA countries contributing to HIV surveillance were not included in the analysis, the presented results might not reflect the situation in the whole EU/EEA. Enhancing surveillance by incorporating the diagnosis status variable would improve characterisation of new diagnoses across countries.

Conclusion

Migrant populations in the EU/EEA are diverse and are disproportionately affected by HIV. Late diagnosis in migrant populations is high generally and particularly high in some migrant sub-groups. Enhanced efforts are required to effectively address HIV prevention and testing needs in the diverse population of migrants who are at risk for or living with HIV in EU/EEA countries.

Ethical statement

The data used in this manuscript come from surveillance systems in EU/EEA countries and can be utilised for public health purposes without requiring individual consent.

Funding statement

There was no funding source for this study.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

None declared.

Data availability

Study materials and raw data are available upon request.

Supplementary Data

Note

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily the views and decisions or policies of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contributions: Data reporting: EU/EEA HIV network; Study design: J.R.U., G.S., F.P., M.J.v.d.W., R.W.; Data analysis: J.R.U., G.S., F.P.; First draft of manuscript: J.R.U., G.S., F.P., C.D.; Critical revision of manuscript: J.R.U., G.S., F.P., M.J.v.d.W., C.D., V.B., V.C.V., H.C.M., J.D., A.D., V.H., E.M.K., J.M., K.O.D., E.O.d.C., C.T., D.V.B., L.v.L., M.W., R.W and each member of the HIV network. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2024 (2023 data). Stockholm: ECDC; 2024. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hiv-aids-surveillance-europe-2024-2023-data

- 2. Reyes-Urueña J, Marrone G, Noori T, Kuchukhidze G, Martsynovska V, Hetman L, et al. HIV diagnoses among people born in Ukraine reported by EU/EEA countries in 2022: impact on regional HIV trends and implications for healthcare planning. Euro Surveill. 2023;28(48):2300642. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.48.2300642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Croxford S, Stengaard AR, Brännström J, Combs L, Dedes N, Girardi E, et al. Late diagnosis of HIV: An updated consensus definition. HIV Med. 2022;23(11):1202-8. 10.1111/hiv.13425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-6. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eurostat. Available from: Migration and migrant population statistics. Luxembourg: Eurostat. [Accessed: 7 Nov 2024]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics#Migration_flows:_Immigration_to_the_EU_was_5.1_million_in_2022

- 6. Yin Z, Brown AE, Rice BD, Marrone G, Sönnerborg A, Suligoi B, et al. Post-migration acquisition of HIV: Estimates from four European countries, 2007 to 2016. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(33):2000161. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.33.2000161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fakoya I, Álvarez-del Arco D, Woode-Owusu M, Monge S, Rivero-Montesdeoca Y, Delpech V, et al. A systematic review of post-migration acquisition of HIV among migrants from countries with generalised HIV epidemics living in Europe: mplications for effectively managing HIV prevention programmes and policy. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):561. 10.1186/s12889-015-1852-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palich R, Arias-Rodríguez A, Duracinsky M, Le Talec J-Y, Rousset Torrente O, Lascoux-Combe C, et al. High proportion of post-migration HIV acquisition in migrant men who have sex with men receiving HIV care in the Paris region, and associations with social disadvantage and sexual behaviours: results of the ANRS-MIE GANYMEDE study, France, 2021 to 2022. Euro Surveill. 2024;29(11):2300445. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.11.2300445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nwokolo N, Whitlock G, McOwan A. Not just PrEP: other reasons for London’s HIV decline. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(4):e153. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, Monforte A, Brockmeyer N, Casabona J, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE). PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001510. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Public health guidance on screening and vaccination for infectious diseases in newly arrived migrants within the EU/EEA. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/public-health-guidance-screening-and-vaccination-infectious-diseases-newly

- 12. Martinez Martinez V, Ormel H, Op de Coul ELM. Barriers and enablers that influence the uptake of HIV testing among heterosexual migrants in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2024;19(10):e0311114. 10.1371/journal.pone.0311114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). HIV and migrants in EU/EEA - Monitoring the implementation of the Dublin Declaration on partnership to fight HIV/AIDS in Europe and Central Asia: 2024 progress report (2023 data). Stockholm: ECDC; 2024. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/evidence-brief-progress-towards-reaching-sustainable-development-goals-related-0

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO). Consolidated guidelines on HIV, viral hepatitis and STI prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva; WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052390 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.